Abstract

This study investigates the intricate relationship between marketing capabilities, resource orchestration capacity, and firm performance within the context of contemporary business environments. A quantitative research approach was employed in this study. Drawing on a sample of 379 firms, the study employed PLS-SEM to assess the impact of marketing capability on a firm’s performance and explore the mediating role played by resource orchestration capability in this dynamic. A structured questionnaire was developed and administered among autonomous business-to-consumer (B2C) firms operating in the service and manufacturing industries. A convenience sampling technique was deployed in this study. This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on marketing strategy by shedding light on the underlying mechanisms through which marketing capability influences firm performance. Practically, the study provides strategic insights for firms aiming to enhance their marketing effectiveness and overall performance by optimizing their resource orchestration capabilities. The implications of this research extend to marketing professionals, strategists, and scholars seeking a deeper understanding of the nuanced interplay between marketing capabilities, resource orchestration, and firm performance in the contemporary business landscape.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Marketing capability is the set of skills, behaviors, tools, procedures, and knowledge that marketing professionals must have to deliver business strategy. The embracement by top management to use resource orchestration capability to establish the nexus between marketing capabilities and firm performance has become nascent. Given this, the rising concern of Business-to-Consumer (B2C) firms to achieve superior performance in a complex and competitive environment has necessitated the role of marketing capabilities.

1. Introduction

The rising concern of Business-to-Consumer (B2C) firms to achieve superior performance in a complex and competitive environment has necessitated the role of marketing capabilities. Marketing Capabilities as a driver of superior firm performance, is becoming a significant interest area for marketing scholars (Cataltepe et al., Citation2022). Several authors consider marketing capabilities as a determining factor of competitive advantage (Susanto et al., Citation2023; Tan & Sousa, Citation2015) and superior performance (Fatonah & Haryanto, Citation2022). When compared with other capabilities, marketing capabilities strongly affect the firm performance (Donnellan & Rutledge, Citation2019). It is important to stress that, marketing capability (e.g., product development capability, pricing capability, channel management capability, marketing communication capability, selling capability) plays a critical role in the formation and delivery of customer value (Son et al., Citation2017) and ultimately firm performance. Capabilities are a vital aspect in this standpoint because they represent a specific non-transferable resource whose purpose is to improve the productivity of other resources that firms possess, have a better overall performance, and create a sustained competitive advantage (Cheruon et al., Citation2023). When an organization integrates its marketing capability as a core value, it can expand competencies, reduce deficiencies, and generate new applications and external opportunities, thus resulting in better overall performance (Songkajorn et al., Citation2022). Meanwhile, firms possess different types of resources and capabilities, among them, several will be strongly associated with better performance (Homburg & Wielgos, Citation2022). These resources when reconfigured to achieve the needed results become the firm’s capabilities.

Meanwhile, for the relationship between marketing capabilities and firm performance especially in Business-to-Customer (B2C), literature has suggested that overall marketing capabilities are positively related to firm performance because they enable firms to acquire and use market knowledge to deliver superior customer value (Mostafiz et al., Citation2022). Other recent studies have also drawn a significant association between marketing capability and a firm’s financial performance (Guo et al., Citation2018; Mu, Citation2015; Wilden & Gudergan, Citation2015). Again, Morgan et al. (Citation2018) draws a positive link between marketing capabilities and firm performance by stressing that, it enhances the level and sustainability of realized positional advantages in the area of the international market. Even though a significant number of marketing capability measures were identified, the results show that the relationship between most of these measures is positive and significant. Yet other studies have shown the relationship to be partially significant and insignificant with negative impact (Kamboj et al., Citation2015). Again, studies have also shown that modifying marketing capabilities frequently as a result of frequent market sensing can have negative effects on performance in stable markets (Wilden & Gudergan, Citation2015).

However, it is important to note that, capabilities are more important than just possession of them (Aljanabi, Citation2022), at least in the sense that simply possessing resources does not lead to achieving specific marketplace objectives in competitive markets without aligned capabilities. According to Iyer et al. (Citation2023), capabilities affect firm performance only after possession. As such, resource possession and resource deployment cannot be isolated (e.g. dealt with independently) in rent-creation processes. While resource picking and deployment are seen as being substitutable in most cases (Iyer et al., Citation2023), it is argued that marketing resource possession and the capability to deploy marketing resources complement each other in creating superior performance outcomes. Given that, marketing capabilities are an important source of competitive advantage, they enable a business to evaluate the marketing strategies of rivals and pertinent market concerns that might guide its strategy. Thus, firms within the manufacturing and service sectors are recognized for their contribution towards the development of the economy especially within the developing economies. However, the ability of top management to fully utilize organization resources to achieve its marketing capabilities reflected in firm performance has received less attention (Khan et al., Citation2021; Ta’Amnha et al., Citation2023). Previous research has mostly used the resource-based view (RBV) to explain the mechanisms underlying the marketing capabilities and firms’ performance (Chen & Lien, Citation2013) without effective intersection with the dynamisms in firms’ operations. While there is substantial research on the relationship between marketing capability and firm performance, limited attention has been given to the mediating role of resource orchestration capability within the context of a developing country particularly, Ghana. Many studies primarily focus on the direct link between marketing capability and firm performance without thoroughly examining how resource orchestration influences this relationship. Also, existing literature has not adequately addressed industry-specific nuances in the relationship between marketing capability, resource orchestration capability, and firm performance. Extant studies acknowledge that leveraging resource orchestration capability through structuring, bundling, and leveraging to assess the nexus between marketing capabilities and firm performance is crucial, yet limited studies have investigated this trajectory. Thus, this paper addresses the gaps by exploring the relationship between marketing capabilities and firm performance mediated by resource orchestration using firms within the manufacturing and service sectors. The Resource Orchestration Theory (ROC) theory gives status to the managerial role in efficiently using a firm’s resources to get an edge over competitors (Rehman et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2023). The ROC postulated the role of managers to effectively structure, bundle, and leverage organizational resources in attaining sustainable firm performance (Asiaei et al., Citation2020). However, an evaluation of the available literature found that no research in the field of marketing capability and firm performance mediated by resource orchestration capability within the manufacturing and service firms in the Ghanaian environment had been conducted (Acquaah & Agyapong, Citation2015; YuSheng & Ibrahim, Citation2020). Practically, the study provides strategic insights for firms aiming to enhance their marketing effectiveness and overall performance by optimizing their resource orchestration capabilities. The implications of this research extend to marketing professionals, strategists, and scholars seeking a deeper understanding of the nuanced interplay between marketing capabilities, resource orchestration, and firm performance in the contemporary business landscape.

2. Literature review

2.1. Marketing capability

Capabilities refer to the knowledge and skills that a company accumulates, which, in turn, allow it to increase the value of its use of resources (Leemann & Kanbach, Citation2022). According to Wu et al. (Citation2023), capabilities are primary to the success of the firm, and as an organization processes resources are converted into values, which contribute to the competitive advantage. Marketing capability, therefore, refers to a package of interrelated routines that facilitate the capacity to engage in specific marketing activities and respond to market knowledge (Hoque et al., Citation2022). Meanwhile, Apasrawirote et al. (Citation2022) define marketing capability, as the integrative process of utilizing firm resources (tangible and intangible) to recognize the specific needs of consumers, attain competitive product differentiation, and realize superior brand equity. He contends that, once these capabilities are developed, it becomes complex for competitors to copy (Day, Citation1994; Mainardes et al., Citation2022). In sum, Apasrawirote et al. (Citation2022) conclude that marketing capability is one of the main capabilities, which facilitate competitive advantage. This is consistent with the literature in the area of marketing which reveals that the capabilities utilized by firms to convert resources into productivity are related to the performance of their firm (Mainardes et al., Citation2022). It is important to note that the execution of marketing capability relies on substantial market knowledge and insights, which are essential to understanding market conditions and consumer needs (Day, Citation2011).

In another development, scholars (e.g., Ali et al., Citation2023; Day, Citation1994) proposed that marketing capabilities can be grouped into two types of capabilities at least. One is related to outside-in capabilities that accurately predict diverse changes in external markets, such as market sensing and technology monitoring as well as changes in customers’ needs while the other is related to inside-out capabilities that focus on managing in-house company resources such as technological and financial resources, costs, and human resources. Based on the above proposition on the types of marketing capabilities therefore, dynamic marketing capabilities can be subdivided into two components i.e., the ability to respond to market changes, namely, market responding capabilities, and the ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure marketing resources, namely, marketing resource rebuilding capabilities. In this sense, the market responding capabilities correspond to outside-in marketing capabilities, while the marketing resource rebuilding capabilities correspond to inside-out marketing capabilities (Ali et al., Citation2023; Khan et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Resource orchestration capability

The Resource Orchestration Capability (ROC) theory emphasizes the ability of firms to integrate and coordinate various resources effectively. The theory provides a holistic perspective on resource management. It recognizes that firm performance is not solely dependent on individual capabilities but on how these capabilities are orchestrated in alignment with the overall resource base of the firm. Emanating from the RBV theory, the ROC was proposed to remedy the dynamic nature of the business environment. Albeit, firms with strong resource orchestration capabilities are better positioned to adapt to changing market conditions. In the realm of marketing, this implies the ability to adjust marketing strategies and tactics in response to evolving customer preferences and competitive landscapes. In the context of this research, this theory helps explain how marketing capabilities are not standalone factors but need to be integrated and orchestrated with other organizational resources to impact firm performance positively. Specific to marketing capabilities, the ROC theory highlights the importance of aligning marketing efforts with other organizational resources. It addresses questions like how marketing capabilities can be integrated with other functions, such as operations or human resources, to achieve optimal firm performance and the dynamics at play. Resource orchestration, as explained by the theory, contributes to enhanced competitiveness. For marketing capabilities to truly impact firm performance, they need to be strategically aligned with other capabilities, ensuring that the organization’s resources are utilized efficiently to gain a competitive edge in the market.

In addition to the direct impacts of marketing capability on resource orchestration capability and of resource orchestration capability on firm performance, resource orchestration capability can mediate the impact of absorptive capacity on firm performance. Meanwhile, some researchers (e.g., Dai, Citation2022; Idrees et al., Citation2023) argued that resource orchestration theory relies on the "process-based" view of resource usage by the firm. Specifically, it states that because the firm must have resources to bundle into capabilities and because capabilities must exist for leveraging to happen, the resource orchestration process is consecutive to a large extent. According to resource orchestration theory, a firm’s ability to effectively manage its resources is more critical than the possession of those resources itself if it seeks to achieve proportional benefit (Idrees et al., Citation2023). Several studies pay attention to the resource orchestration process to disclose how a crucial firm can orchestrate resources at its disposal as part of its strategy to achieve competitive advantage. For example, Cui et al. (Citation2017) utilize the concept of resource orchestration as a theoretical lens to develop a framework of how resources are orchestrated to achieve e-commerce-enabled social innovation. This implies that additional theory development is required to add richness to our understanding of how managers orchestrate resources in dynamic environments such as those associated with marketing capabilities, to improve firm performance (Idrees et al., Citation2023), as the combination of resources and managerial acumen to realize superior firm performance is through Resource orchestration (Chadwick et al., Citation2015). Therefore, further investigation is needed into how a marketing capability improves firm performance through the mediating role of resource orchestration capability. The understanding of this will have considerable implications for research, policy, and practice alike by highlighting the importance of taking a more holistic view of marketing capabilities development, allowing firms to generate higher returns.

2.3. Marketing capability and firm performance

Several authors consider marketing capabilities as a determining factor of competitive advantage (Apasrawirote et al. Citation2022; Tan & Sousa, Citation2015) and superior performance. Empirical studies have also confirmed a link between marketing capabilities and firm performance (Krush et al., Citation2015; Mu, 2015; Wilden & Gudergan, Citation2015). Meanwhile, Day (Citation2011) and (Guo et al., Citation2018), identified three types of marketing capabilities: (1) static marketing capabilities, or the capabilities of using internal resources to satisfy market demand, (2) dynamic marketing, or the capabilities of adjusting own marketing capabilities to the changing market environment; and (3) adaptive marketing capabilities or the capabilities of engaging in vigilant market learning, adaptive market experimentation, and open marketing through relationships forged with partners (Rehman et al., Citation2022). Firms with static marketing capability use their internal resources and capabilities to satisfy current customers, exploit existing products and distribution channels, and advertise existing brands (Hunt & Madhavaram, Citation2020). Note that the basic marketing-mix elements are considered static marketing capabilities because they either "[offer] an implicitly static portrayal of organizational capabilities as well-honed and difficult-to-copy routines for carrying out established processes" (Day, Citation2011) or focus solely on the ability to exploit and use existing internal resources.

Also, Varadarajan (Citation2020) has found that dynamic marketing capability helps firms create and deliver superior customer value through responsive and efficient marketing processes as well as establish and maintain competitive advantage and superior performance. Compared with static marketing capability, which focuses on exploiting and using existing resources or processes to satisfy current market demand or deal with market competition, dynamic marketing capability emphasizes firms’ cross-functional process-changing capability to respond to market changes by exploring and reactively integrating resources. In other words, dynamic marketing capability can help firms respond to environmental changes by adjusting their cross-functional processes, such as product development management, supply chain management, and customer management (Xu et al., Citation2018). In addition, dynamic marketing capability can help firms maintain a sustainable advantage over their competitors and thus achieve superior performance. With adaptive marketing capability, Day (Citation2011) posits that all three components of adaptive marketing capability, vigilant market learning, market experimentation, and open marketing play a significant role in affecting firm performance. A recent study conducted by Guo et al. (Citation2018), has established that adaptive marketing capabilities have a greater impact on firms’ business performance than static and dynamic marketing capabilities. In sum, static, dynamic, and adaptive marketing capabilities are essential marketing capabilities that differ in terms of their theoretical foundation, market understanding, strategic priorities, and inner components and therefore have a differential effect on firm performance (Guo et al., 2018). Against this background, the below hypothesis is formulated;

H1: There is a significant relationship between marketing capability and firm performance

2.4. Marketing capability and resource orchestration capability

According to Day (Citation1994), marketing capability is the integrative process of utilizing firm resources (tangible and intangible) to recognize the specific needs of consumers. Meanwhile, the execution of marketing capability relies on substantial market knowledge and insights, which are essential to understanding market conditions and consumer needs (Day, Citation2011). Precisely, Morgan et al. (Citation2012) argued that marketing capabilities are responsible for transforming a company’s marketing resources into valuable results. This is therefore, in agreement with resource orchestration theory that has been advanced to address the previous neglect of the processes by which managers accumulate, combine, and exploit resources to support current opportunities while developing future opportunities to achieve a competitive advantage (Rehman et al., Citation2022). Resource orchestration theory suggests that it is the combination of resources, capabilities, and managerial action that ultimately results in superior firm performance (Chadwick et al., Citation2015; Iyer et al., Citation2023). Scholars have suggested that possessing resources alone does not guarantee the development of competitive advantage (Lahiri et al., Citation2022) and that holding valuable and rare resources is necessary but not enough, and sufficient conditions for achieving a competitive advantage. Resources should also be managed effectively to generate synergistic effects. Thus, the study proposes this hypothesis:

H2: There is a positive relationship between marketing capability and resource orchestration capability

2.5. Resource orchestration capability and firm performance

Resource orchestration capability is the ability of a firm to effectively structure, bundle, and leverage the resource portfolio toward firm performance (Choi et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). It is important to stress that, resource orchestration theory suggests that it is the combination of resources, capabilities, and managerial action that ultimately results in superior firm performance (e.g., Chadwick et al., Citation2015; Yu et al., Citation2021). Simply considering the resources a firm possesses provides an incomplete understanding of company performance. Resource orchestration theory emphasizes the role of managerial action in mobilizing and leveraging firm resources to achieve strategic objectives (Idrees et al., Citation2023). The orchestration of resources is critical to support processes to aid in developing and leveraging capabilities (Rehman et al., Citation2022). The Theory assumes that managers can structure a firm’s resource portfolio, bundle the resources to build relevant capabilities, and leverage these capabilities to eventually realize a competitive advantage (Idrees et al., Citation2023). Moreover, Kristoffersen et al. (Citation2021) added three key elements: breadth (scope of the firm), depth (levels within the firm), and life cycle affect the three above-mentioned assumptions. Even though these three elements improve our understanding of the Resource Orchestration Theory, they are addressed rather abstractly in current literature (). Thus, the study proposes this hypothesis:

H3: There is a positive relationship between resource orchestration capability and firm performance.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sampling and data collection

Although scholars have highlighted the essence of marketing capabilities and firms’ performance, however, there are no empirical studies between marketing capabilities and firm performance from the Ghanaian perspective (Pundziene et al., Citation2022; Rehman et al., Citation2019). With this in mind, we sought to investigate the link between marketing capabilities and firms’ performance being mediated by resource orchestration capability. To achieve the main objective of this study, the authors adopted a non-randomized sampling technique, specifically, convenience sampling to choose the study respondents/participants who are ready to volunteer the needed information for the data processing/analysis. Specifically, the researchers developed a structured questionnaire and distributed it among autonomous business-to-consumer (B2C) firms operating in the service and manufacturing industries in Ghana. The study adopted convenience sampling due to its recent usage in articles within the service and manufacturing domain and grounded on the participants’ availability, quick data collection, low cost, and keenness to produce the required information needed to accomplish this study objective (Amoah et al., Citation2023; Bruce et al., Citation2023). Both face validity and content validity were done. Face validity was done to ensure clarity, comprehensibility, and appropriateness for the target groups, while content validity was also done to determine the appropriateness of the content and identify any misunderstandings or omissions. The study focused on firms that have operated for at least three years and above (De Clercq & Zhou, Citation2014). Before embarking on the data collection, the researcher formally sought the approval of the respondent’s consent. Accordingly, this study used a structured questionnaire as the data collection instrument. To accomplish the desired objective of the present study, a structured questionnaire was framed in English with the help of Google Forms. Both online and offline means were used to administer the questionnaires to the Senior Managers, Chief Executive Officers, Operation managers, Marketing managers, and General managers of the selected companies. Out of the 379 valid responses used in this study, the online means of data collection generated 215 valid responses representing 56.73 percent while the offline produced 164 valid responses 43.27 percent. The study relied on these participants to answer the questionnaire based on the substantial knowledge in their possession, to gather some level of tangible data that would be useful to both theory and practice.

The Registrar Generals Department was visited to solicit information on the registered service and manufacturing firms. After receiving the details, formal permission was sought by the researchers through their emails, WhatsApp messages, letters, and other means. After permission was granted to the researchers, the data collection process began. The questionnaires were designed through Google Forms and distributed via participants’ emails and other social media networking sites (i.e., WhatsApp, Twitter, Telegram) to facilitate response. It is important to highlight that the offline copies of the questionnaire administered were later picked after some weeks. This is as a result of the busy schedule of the respondents. Most of the respondents were visited during their launch time. The current study used the cross-sectional approach. In addition, informed consent was sought and was deemed necessary for ethical consideration. The essence of using service and manufacturing firms for data collection was a result of their relevant contributions to the socio-economic development of the country. The present study adopted the Likert scale measurement as used in existing studies and has been applied frequently. The duration data collection process took was researchers four months from September to December 2022. Before the entire research commenced, a pilot study was conducted to ascertain the reliability and validity of the research constructs with 50 questionnaires. To emphasis more on the data output, 400 questionnaires were administered. Given this, 379 were received of which twenty-one (21) of the received questionnaires were eliminated since they contained anomalies that made them unfit for the data processing and analysis, giving a 94.75 percent response rate. It is extremely significant to reveal that more of the responses were received through online means. To get rid of duplication of responses, respondents were restricted to one response both the offline and the online Google forms. Hair et al. (Citation2012) established that a study of a quantitative study should have more than 300 valid responses for its data analysis and processing (Amoah, Citation2010). Given this, the present study meets this criterion with the usage of 379 for its data processing and analysis. The survey participants were advised to not indicate their affiliations on the questionnaire instrument to avoid unethical standards. The Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) version 3.3 (Hammami et al., Citation2021) was used to analyze the data with participants’ profile results reported in .

Table 1. Background information of respondents.

3.2. Measurement of study constructs

The researcher drew ideas from earlier research to determine the construct’s validity. The study’s constructs were taken directly from earlier literary works. Therefore, the study’s constructs for Marketing Capabilities (Theoharakis & Hooley, Citation2003; Santos-Vijande et al., Citation2012; Dibrell et al., Citation2014), Firm Performance (Matsuno et al., Citation2002; O’Cass & Ngo, Citation2012), and resource orchestration capability (Sirmon et al., Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2020). Additionally, using a five-point Likert scale, the respondent’s level of agreement or disagreement was used to quantify the components, mostly to facilitate responding (Theoharakis & Hooley, Citation2003; Santos-Vijande et al., Citation2012; Dibrell et al., Citation2014; Fang & Zou, Citation2009).

3.3. Test of common method variance (CMV)

The current study’s independent data collection increases the chance of shared method variance. To maintain research ethics, respondents were assured of data privacy and protection during the questionnaire administration. According to Bagozzi and Pieters (Citation1998), the researchers devised the questionnaire with the title page description and the respondents’ highest confidence in mind. The questionnaire was designed in such a way that individuals might opt out at any time. To validate the existence of common method bias (CMV), the authors used a multicollinearity test with the VIF (variance inflation factor). According to VIFs, the post-hoc evaluation results show that CMV has a low presence (see table).

4. Empirical results

4.1. Model measurement

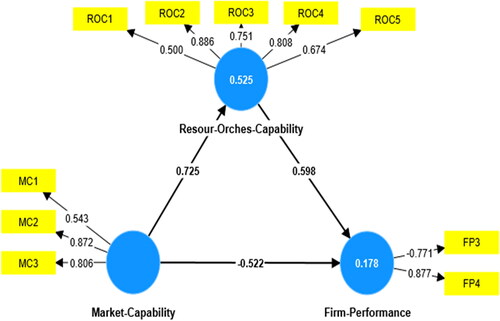

As the researcher was encouraged by the PLS-SEM application literature of scholarly works (Hair et al., Citation2017; Citation2019), the constructs’ reliability and validity were aggressively tested using Dijkstra-Henseler’s with Cronbach alpha coefficients. Because the coefficient values are all greater than 0.5 (see below), it indicates the strongest of the constructs’ coefficients as determined by Bagozzi and Pieters (Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2019). The PLS-SEM version 3.3 was used to assess the psychometric qualities of the underlying items of the research constructs. Again, the composite reliability of constructs, as shown in (), recorded 0.7 and 0.9 minimum and maximum thresholds for Jöreskog’s rho (pc) and Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (pA), indicating that the essential conditions were met. Finally, a minimum threshold of 0.5 was noted for the average variance extracted (AVE), which stands for convergent validity, as shown in . For Dijkstra-Henseler rho (pA), 0.777 and 0.922 were recorded as coefficients of construct reliability, respectively. Bagozzi and Pieters (Citation1998) literature reveals that all of the factor loadings of the constructs were carefully evaluated, loaded to their appropriate places, and also meant the requirement of 0.6, which demonstrates how effective the indicator is. Again, it is important to make it known that the first (FP1) and second (FPM2) items of firm performance were dropped because they fell short of the threshold value of 0.5) (). According to the table below, all of the constructs’ coefficients were over 0.5, with the minimum and maximum loadings being 0.500 and 0.877, respectively. above displays all of the information regarding the research constructs and their respective loadings. Also, the researcher was quite concerned about the problem of multicollinearity, and they used the common method variance (CMV) to find it using scale measurements of the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF is less than five as opposed to a maximum threshold of ten, according to the works of Attor et al. (2022; Amoah et al., 2021), hence CMV is not a problem. above displays the factor loadings for the research constructs.

Table 2. Construct reliability, validity, and factor loadings.

A circumstance when we observe that two indications are statistically different is referred to as discriminant validity. Additionally, discriminant validity illustrates how different from another variable a variable is in the real world based on empirical measures (Hair et al. Citation2014). However, Henseler et al. (Citation2015) advised the researcher to evaluate the possibility of the discriminant validity of the latent variables using Fornell-Larcker (Citation1981). According to experts like Hair et al. (Citation2019) and Henseler et al. (Citation2015), all values in the diagonal form (bold) are greater than the minimum requirement of more than 0.5, demonstrating the average variance extracted (AVE) of the assessed constructs (see below). Once each average was required to have greater coefficients (both column and row position) than the other constructs, according to Fornell-Larcker’s criterion of discriminant validity, the fundamental and rigorous assumptions of the study constructs were determined.

Table 3. Test of discriminant validity – Fornell-Larcker criterion.

4.2. Structural modeling analysis

In this present investigation on model fit, the researcher saw the essence of route analysis, also known as structural modeling. The purpose of this analysis is to determine the causal influence of the research constructs. The regression coefficients of Beta (β), significant values; T-values >1.96 (or P-values 0.05) concerning the study model are thus shown in below. Additionally, the predictive power related to the regression model’s research model for determining values was assessed. As can be seen in the table and figure below, the predictive variable (Resource Orchestration Capability) has an established (). The study recorded 17% and 52% for firm performance and Resource Orchestration Capability respectively.

Table 4. Hypothetical path coefficient sources.

5. Discussion

This paper investigates the nexus between Marketing Capabilities and Firm Performance mediated by Resource Orchestration Capability. The investigation was quantitative. It is extremely important to highlight that three hypotheses were formulated and tested in this study. The outcomes of this study are discussed, and in particular, the significance to service and manufacturing firms. The first hypothesis, H1: marketing capability has a positive relationship with firm performance is accepted according to the results (p-value 0.018). Hence, this study reveals that marketing capabilities directly influence firm performance. This hypothesis is strongly affirming the previous works of Mu et al. (Citation2018; Mu, Citation2017). This is because of the variety and regularity of market shifts, and quick adaptation to their resource allocation to the ever-changing landscape. To add more, the ability to use and orchestrate resources with greater flexibility explains why some organizations are more successful than others. Through responsive and effective marketing processes, marketing capability enables businesses to achieve and retain a competitive edge and exceptional firm performance. Given the apparent impact of marketing capabilities on a firm’s performance, firms with unchanging marketing capabilities use their resources and skills to please present customers, capitalize on existing products and distribution networks, and promote existing brands. Indeed, it implies that enterprises within an industry vary in terms of their talents and resources and that this variation is the basis of the competitive edge that firms achieve in their market (Sok et al., Citation2017). It is hence established that marketing capabilities have a stronger impact on the company’s performance (Guo et al., Citation2018). Note that, Marketing Capabilities are of three types, particularly, static, dynamic, and adaptive. These marketing capabilities differ in terms of their theoretical underpinnings, market comprehension, strategic priorities, and internal workings, and as a result, they have a distinct impact on the performance of the organization.

The study set out to investigate the relationship between marketing capabilities and Resource Orchestration Capability. Also, with this hypothesis, a positive relationship was obtained as per the results. This is because the p-value (0.000) which is used as a basement for the relationship assessment was met. This assertion affirms previous studies (Badrinarayanan et al., Citation2019; Choi et al., Citation2020; Cui & Pan, Citation2015). It is therefore opined that marketing capabilities form an integrated process of using a company’s resources (tangible and intangible) to identify the unique needs of customers. This helps in the transformation of marketing resources into valuable results. While this is going on, marketing capability effectiveness depends on comprehensive market analysis and expertise, which are crucial for comprehending market dynamics and consumer wants. The resource orchestration paradigm has been used to comprehend resource management across a firm’s life cycle (which varies stages of a firm’s evolution), spectrum (the firm’s scope), and depth (at various hierarchical levels. Sirmon et al. (Citation2011) investigated the influence of resource orchestration on corporate-level strategies, business-level strategies, and the life cycle of an organization, and several of their recommendations have major implications for how businesses might improve and sustain their performance.

Finally, hypothesis three which states that: resource orchestration capability has a positive effect on firm performance was tested. The findings of this hypothesis were not supported. This hypothesis was not supported due to certain factors like frequent changes in management positions and roles among other factors. This hypothesis is contrary to the previous studies of (Choi et al., Citation2020; Kristoffersen et al., Citation2021) where it was evident that there is a positive relationship between resource orchestration capability and firm performance. It is therefore established that resource orchestration capability adequately contributes to firm performance. It is critical to emphasize that, according to resource orchestration theory, it is the amalgamation of assets, capabilities, and leadership behavior that ends up resulting in greater business performance (Chadwick et al., Citation2015). The management’s role in mobilizing and exploiting corporate resources to meet strategic goals is emphasized by resource orchestration theory. As a result, businesses that apply resource orchestration capabilities can allocate and use resources more effectively as they work to increase firm performance (Chadwick et al., Citation2015). It is specifically assumed that effective resource orchestration would foster a new capability of allocating and bundling the limited resources as efficiently as possible to produce value-oriented and productive outcomes, further strengthening the relationship between firm performances (Choi et al., Citation2020).

6. Practical and theoretical implications

This study makes a valuable contribution to both theoretical and practical domains by enhancing comprehension of the nexus between marketing capabilities and firm performance within the manufacturing and services sectors in an emerging economy. The results of this study have the potential to provide valuable insights for policymakers, managers, and stakeholders, facilitating informed decision-making and promoting effective collaboration. Ultimately, these outcomes can contribute to the successful implementation and integration of marketing capabilities elements such as creativity, strategy, and collaboration.

We deduced the following theoretical and practical conclusions from the results of our empirical investigation. Theoretically, the study contributes to theoretical advancements in the field of marketing capabilities and firm performance by adopting the Resource-orchestration theory. The resource orchestration theory perspective provides a framework that integrates mobilized resources into an efficient framework to allow improved alignment, synchronization, and direction for a given utilization based on the fundamental tenet of resource mobilization. The study expands the application of the Resource orchestration theory within the specific context of manufacturing and service firms. The results of this study have the potential to enhance the existing Resource orchestration theory literature by emphasizing the significance of marketing capabilities on firm performance in attaining a competitive advantage through the process of digital transformation. Although few studies have been conducted on marketing capabilities and firm performance, this study brings on board combining the two variables mediated by resource orchestration capability from the perspective of a developing economy, particularly manufacturing and service sectors (Cataltepe et al., Citation2022; Mu et al., Citation2018). The results of this study’s investigation into the mediating role of resource orchestration theory on the impact of marketing capability on company firm performance help us comprehend the implications of utilizing skills, talents, resources (tangible and intangible), and updated knowledge swiftly and strategically. Considering that studies of resource orchestration capability are limited within manufacturing and service; the findings of this study may contribute to the literature and provide a basis for future studies from an emerging economy.

By far, this study comes with some overarching implications for practice. It is imperative that, in recent times, the tourism sector has become one of the most competitive economic sectors globally (Auliya et al., Citation2020). Ghana, as a key in the manufacturing and service sector, has observed some rising development in the sector. This impressive development has occasioned stern competition among manufacturing and service providers, who are racing against each other. The study’s conclusions could serve as a useful manual for manufacturing and service managers. Studies on marketing capabilities and resource orchestration capability can help managers improve their performance in management, particularly in nations with strong environmental changes because the industrial and service sectors respond quickly to these changes. Companies need to be aware that creatively bundling and orchestrating their current resources along with the newly introduced resources and capabilities is as vital as obtaining new resources when pursuing a new business opportunity or groundbreaking a market if they want to effectively implement their strategies. This is because the firm resource orchestration capability is essential to optimizing the nexus between marketing capability and firm performance. Lastly, organizations should take particular steps to improve marketing capabilities and resource orchestration capabilities because they both improve a company’s performance. This research will enable organizations to leverage partner capabilities and resources for value creation, help firms sense and respond to market changes such as competitors’ moves and technological revolutions, and help firms predict and anticipate both explicit and latent customer needs. Enhanced sense-making ability also broadens the possible scope of strategic reactions and, ultimately, improves performance depending on the needs of the client. In turn, these can assist companies in creating innovative new products or repurposing old ones with fresh features and qualities to meet the demands of both present and potential clients. This can help firms maintain stability, withstand changes in the market, and prevent shocks from emerging competitive waves that capitalize on novel technologies and fresh value statements. Marketing capabilities strongly influence and further strengthen the influence of firms’ performance (Majali et al., Citation2022).

6.1. Conclusion

This study investigated marketing capabilities and firm performance mediated by resource orchestration capabilities from the perspective of manufacturing and service sectors. Based on the empirical data collected from 379 manufacturing and service firms in Ghana. It was revealed that resource orchestration capability has a positive relationship with marketing capabilities and an adverse relationship was obtained between firm performance and resource orchestration capabilities. In addition, this study also highlighted the relationship between marketing capability and firm performance. The study used Partial Least Square and Structural Equation Modeling version 3.3 to process and analyze the data collected. As a result, this study has helped to identify the variables that can optimize the impact of resource orchestration capabilities on business performance. Despite its limits, our research on substantial mediating offers practical insights for businesses looking to improve the effectiveness of marketing capabilities and firm performance and the essential elements that fuel long-term firm growth.

6.2. Limitations of the study

Similar to other studies, the current one has some limitations that should be taken into account in future research on these variables. First and foremost, the current study was carried out in Ghana, a developing country in the service and manufacturing sector. As a result, in the future, there will be a need to research similar variables in other nations that are involved in both manufacturing and service industries. Second, this study has a small sample size, which should be increased in future investigations. Thirdly, the study made use of cross-sectional data of which future research may require a longitudinal method.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Frank Agyemang Duah

Frank Agyemang Duah is a senior lecturer at the Darprtment of Marketing and Strategy, Takoradi Technical University, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Marketing from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He has published in some respected and high ranked journals. His research areas are Digital marketing, E-commerce, among others.

Bylon Abeeku Bamfo

Rev. (Prof.) Bylon Abeeku Bamfo. Associate Professor. Dept: Marketing and Corporate Strategy. Areas of research include: Consumer Behavior, Small Business Management, Marketing communication and Entrepreneurship marketing.

John Serbe Marfo

Dr. John Serbe Marfo is a Lecturer at the Department of Supply Chain and Information Systems at the KNUST School of Business. He has a PhD in Information Systems. He is a researcher and a consultant in supply chain digitalization, information systems, health informatics, big data analytics and eLearning. His recent research work in supply chain digitalization focuses on the use of drone technology as a logistics tool to improve health care delivery and supply chains.

References

- Acquaah, M., & Agyapong, A. (2015). The relationship between competitive strategy and firm performance in micro and small businesses in Ghana: The moderating role of managerial and marketing capabilities. Africa Journal of Management, 1(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2015.1025684

- Ali, S., Wu, W., & Ali, S. (2023). Managing the product innovations paradox: the individual and synergistic role of the firm inside-out and outside-in marketing capability. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(2), 504–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-05-2021-0234

- Aljanabi, A. R. A. (2022). The role of innovation capability in the relationship between marketing capability and new product development: evidence from the telecommunication sector. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(1), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2020-0146

- Amoah, J. (2010). Aktivátory a inhibitory sociálních médii ve vztahu k rozvoji MSP na příkladu MSP působících v sektoru služeb v Ghaně.

- Amoah, J., Jibril, A. B., Odei, M. A., Bankuoru Egala, S., Dziwornu, R., & Kwarteng, K. (2023). Deficit of digital orientation among service-based firms in an emerging economy: a resource-based view. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2152891. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2152891

- Apasrawirote, D., Yawised, K., & Muneesawang, P. (2022). Digital marketing capability: the mystery of business capabilities. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 40(4), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-11-2021-0399

- Asiaei, K., Bontis, N., & Zakaria, Z. (2020). The confluence of knowledge management and management control systems: A conceptual framework. Knowledge and Process Management, 27(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1628

- Auliya, Z. F., Auliya, Z. F., & Pertiwi, I. F. P. (2020). The influence of electronic word of mouth (E-WOM) and travel motivation toward the interest in visiting Lombok, gender as a mediator. INFERENSI: Jurnal Penelitian Sosial Keagamaan, 13(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.18326/infsl3.v13i2.201-218

- Badrinarayanan, V., Ramachandran, I., & Madhavaram, S. (2019). Resource orchestration and dynamic managerial capabilities: focusing on sales managers as effective resource orchestrators. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 39(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2018.1466308

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Pieters, R. (1998). Goal-directed emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 12(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379754

- Bruce, E., Shurong, Z., Ying, D., Yaqi, M., Amoah, J., & Egala, S. B. (2023). The effect of digital marketing adoption on SMEs sustainable growth: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Sustainability, 15(6), 4760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064760

- Cataltepe, V., Kamasak, R., Bulutlar, F., & Alkan, D. P. (2022). Dynamic and marketing capabilities as determinants of firm performance: evidence from the automotive industry. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 17(3), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-11-2021-0475

- Chadwick, C., Super, J. F., & Kwon, K. (2015). Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment‐based HR systems, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 36(3), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2217

- Chen, C. W., & Lien, N. H. (2013). Technological opportunism and firm performance: Moderating contexts. Journal of Business Research, 66(11), 2218–2225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.001

- Cheruon, R. C., Korir, J., & Burugu, R. (2023). Networking capability and competitive advantage of event management ventures in Kenya. Research Journal of Business and Finance, 2(2), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.58721/rjbf.v2i2.328

- Choi, S. B., Lee, W. R., & Kang, S. W. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation, resource orchestration capability, environmental dynamics, and firm performance: A test of three-way interaction. Sustainability, 12(13), 5415. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135415

- Cui, M., & Pan, S. L. (2015). Developing focal capabilities for e-commerce adoption: A resource orchestration perspective. Information & Management, 52(2), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.08.006

- Cui, M., Pan, S. L., Newell, S., & Cui, L. (2017). Strategy, resource orchestration, and e-commerce enabled social innovation in Rural China. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 26(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2016.10.001

- Dai, X. (2022). Supply chain relationship quality and corporate technological innovations: A multimethod study. Sustainability, 14(15), 9203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159203

- Day, G. S. (1994). The capabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251915

- Day, G. S. (2011). Closing the marketing capabilities gap. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.4.183

- De Clercq, D., & Zhou, L. (2014). Entrepreneurial strategic posture and performance in foreign markets: the critical role of international learning effort. Journal of International Marketing, 22(2), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.13.0131

- Dibrell, C., Craig, J. B., & Neubaum, D. O. (2014). Linking the formal strategic planning process, planning flexibility, and innovativeness to firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 2000–2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.011

- Donnellan, J., & Rutledge, W. L. (2019). A case for resource‐based view and competitive advantage in banking. Managerial and Decision Economics, 40(6), 728–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3041

- Fang, E., & Zou, S. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of marketing dynamic capabilities in international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(5), 742–761. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.96

- Fatonah, S., & Haryanto, A. J. (2022). Exploring market orientation, product innovation, and competitive advantage to enhance the performance of SMEs under uncertain events. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10(1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2021.9.011

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Guo, H., Xu, H., Tang, C., Liu-Thompkins, Y., Guo, Z., & Dong, B. (2018). Comparing the impact of different marketing capabilities: Empirical evidence from B2B firms in China. Journal of Business Research, 93, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.010

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2).

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130

- Hammami, S. M., Ahmed, F., Johny, J., & Sulaiman, M. A. (2021). Impact of knowledge capabilities on organizational performance in the private sector in Oman: an SEM approach using path analysis. International Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJKM.2021010102

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Homburg, C., & Wielgos, D. M. (2022). The value relevance of digital marketing capabilities to firm performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(4), 666–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-022-00858-7

- Hoque, M. T., Ahammad, M. F., Tzokas, N., Tarba, S., & Nath, P. (2022). Eyes open and hands-on: market knowledge and marketing capabilities in export markets. International Marketing Review, 39(3), 431–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-01-2021-0003

- Hunt, S. D., & Madhavaram, S. (2020). Adaptive marketing capabilities, dynamic capabilities, and renewal competencies: The “outside vs. inside” and “static vs. dynamic” controversies in strategy. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.07.004

- Idrees, H., Xu, J., & Andrianarivo Andriandafiarisoa Ralison, N. A. (2023). Green entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process as enablers of green innovation performance: the moderating role of resource orchestration capability. European Journal of Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-02-2023-0143

- Iyer, K. N., Srivastava, P., & Srinivasan, M. (2023). Symbiotic association of resources and market-facing capabilities in supply chains as determinants of performance: a resource orchestration perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 57(11), 2893–2917. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2021-0290

- Kamboj, S., Goyal, P., & Rahman, Z. (2015). A resource-based view on marketing capability, operations capability, and financial performance: An empirical examination of mediating role. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 189, 406–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.201

- Khan, A. A., Asad, M., Khan, G. u., Asif, M. U., & Aftab, U. (2021 Sequential mediation of innovativeness and competitive advantage between resources for business model innovation and SME performance [Paper presentation]. 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA), (pp. 724–728). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DASA53625.2021.9682269

- Khan, H., Freeman, S., & Lee, R. (2020). New product performance implications of ambidexterity in strategic marketing foci: a case of emerging market firms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 36(3), 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2020-0003

- Kristoffersen, E., Mikalef, P., Blomsma, F., & Li, J. (2021). The effects of business analytics capability on circular economy implementation, resource orchestration capability, and firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 239, 108205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108205

- Krush, M. T., Sohi, R. S., & Saini, A. (2015). Dispersion of marketing capabilities: impact on marketing’s influence and business unit outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0420-7

- Lahiri, S., Karna, A., Kalubandi, S. C., & Edacherian, S. (2022). Performance implications of outsourcing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1303–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.061

- Leemann, N., & Kanbach, D. K. (2022). Toward a taxonomy of dynamic capabilities–a systematic literature review. Management Research Review, 45(4), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2021-0066

- Li, L., Chen, L., Yan, J., Xu, C., & Jiang, N. (2023). How does technological opportunism affect firm performance? The mediating role of resource orchestration. Journal of Business Research, 166, 114093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114093

- Mainardes, E. W., Cisneiros, G. P. D. O., Macedo, C. J. T., & Durans, A. D. A. (2022). Marketing capabilities for small and medium enterprises that supply large companies. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 37(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-07-2020-0360

- Majali, T., Alkaraki, M., Asad, M., Aladwan, N., & Aledeinat, M. (2022). Green transformational leadership, green entrepreneurial orientation and performance of SMEs: The mediating role of green product innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(4), 191–114. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8040191

- Morgan, N. A., Feng, H., & Whitler, K. A. (2018). Marketing capabilities in international marketing. Journal of International Marketing, 26(1), 61–95. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.17.0056

- Morgan, N. A., Katsikeas, C. S., & Vorhies, D. W. (2012). Export marketing strategy implementation, export marketing capabilities, and export venture performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0275-0

- Mostafiz, M. I., Ahmed, F. U., & Hughes, P. (2022). Open innovation pathway to firm performance: the role of dynamic marketing capability in Malaysian entrepreneurial firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2022-0206

- Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J. T., & Özsomer, A. (2002). The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.3.18.18507

- Mu, J. (2015). Marketing capability, organizational adaptation, and new product development performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 49, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.003

- Mu, J. (2017). Dynamic capability and firm performance: The role of marketing capability and operations capability. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 64(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2017.2712099

- Mu, J., Bao, Y., Sekhon, T., Qi, J., & Love, E. (2018). Outside-in marketing capability and firm performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 75, 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.03.010

- O’cass, A., & Ngo, L. V. (2012). Creating superior customer value for B2B firms through supplier firm capabilities. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(1), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.11.018

- Pundziene, A., Nikou, S., & Bouwman, H. (2022). The nexus between dynamic capabilities and competitive firm performance: the mediating role of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 152–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2020-0356

- Rehman, S.-u., Mohamed, R., & Ayoup, H. (2019). The mediating role of organizational capabilities between organizational performance and its determinants. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0155-5

- Rehman, S. U., Bresciani, S., Ashfaq, K., & Alam, G. M. (2022). Intellectual capital, knowledge management, and competitive advantage: a resource orchestration perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(7), 1705-1731.

- Santos-Vijande, L., Sanzo-Pérez, M., Trespalacios Gutiérrez, J., & Rodríguez, N. (2012). Marketing capabilities development in small and medium enterprises: implications for performance. Journal of CENTRUM Cathedra: The Business and Economics Research Journal, 5(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.7835/jcc-berj-2012-0065

- Sirmon, D. G., Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Gilbert, B. A. (2011). Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage: Breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1390–1412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385695

- Sok, P., Snell, L., Lee, W. J., & Sok, K. M. (2017). Linking entrepreneurial orientation and small service firm performance through marketing resources and marketing capability: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(1), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-01-2016-0001

- Son, H., Lee, J., & Chung, Y. (2017). Value creation mechanism of social enterprises in manufacturing industry: Empirical evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 10(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010046

- Songkajorn, Y., Aujirapongpan, S., Jiraphanumes, K., & Pattanasing, K. (2022). Organizational strategic intuition for high performance: The role of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and digital transformation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030117

- Susanto, P., Hoque, M. E., Shah, N. U., Candra, A. H., Hashim, N. M. H. N., & Abdullah, N. L. (2023). Entrepreneurial orientation and performance of SMEs: the roles of marketing capabilities and social media usage. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(2), 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-03-2021-0090

- Ta’Amnha, M. A., Magableh, I. K., Asad, M., & Al-Qudah, S. (2023). Open innovation: The missing link between the synergetic effect of entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge management over product innovation performance. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(4), 100147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100147

- Theoharakis, V., & Hooley, G. (2003). Organizational resources enabling service responsiveness: Evidence from Greece. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(2), 695–702.

- Tan, Q., & Sousa, C. M. (2015). Leveraging marketing capabilities into a competitive advantage and export performance. International Marketing Review, 32(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-12-2013-0279

- Varadarajan, R. (2020). Customer information resources advantage, marketing strategy, and business performance: A market resources-based view. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.03.003

- Wang, J., Xue, Y., & Yang, J. (2020). Boundary‐spanning search and firms’ green innovation: The moderating role of resource orchestration capability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2369

- Wilden, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2015). The impact of dynamic capabilities on operational marketing and technological capabilities: investigating the role of environmental turbulence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0380-y

- Wu, Q., Yan, D., & Umair, M. (2023). Assessing the role of competitive intelligence and practices of dynamic capabilities in business accommodation of SMEs. Economic Analysis and Policy, 77, 1103–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.11.024

- Xu, J., Yu, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, J. Z., Liu, Y., Cao, Y., & Eachempati, P. (2018). Green supply chain management for operational performance: anteceding impact of corporate social responsibility and moderating effects of relational capital. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 35(6), 1613–1638. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-06-2021-0260

- Yu, W., Liu, Q., Zhao, G., & Song, Y. (2021). Exploring the effects of data-driven hospital operations on operational performance from the resource orchestration theory perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management.

- YuSheng, K., & Ibrahim, M. (2020). Innovation capabilities, innovation types, and firm performance: evidence from the banking sector of Ghana. SAGE Open, 10(2), 215824402092089. 2158244020920892. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020920892

Appendix A

The effect of marketing capabilities on firm performance: the role of resource orchestration capability.

Section one

Background Characteristics of Respondents

Please tick in the boxes provided.

Gender of respondent: (a) Male [] (b) Female []

Age of respondent: (a) Less than 24 years [] (b) 24 – 30 years [] (c) 31 – 37 years [] (d) 38 – 44 years [] (e) 45 years and above []

Highest educational level of respondent: (a) No formal education [] (b) Basic [] (c) Secondary [] (d) Tertiary []

Number of years in business/operation: (a) Less than 6 years [] (b) 6 – 10 years [] (c) 11 – 15 years [] (d) Over 15 years []

What is the current number of employees in your company? …………………

Industry Manufacturing [] Service provider [] Consultancy [] Retailing [] Information technology [] Financial [] others []

Section two: marketing capabilities

Please indicate your response using the Likert scale given: 1-strongly disagree, 2-disagree, 3-neutral, 4-Agree, and 5-strongly Agree

MARKETING CAPABILITIES

To what extent do you believe our organization possesses the necessary skills and expertise to develop and execute effective marketing strategies?

Our company is highly sensitive to the market environment and can detect market signals timely and accurately

Through resource integration with our partners, our company gains the capabilities for continuous product and technology innovation.

Our firm actively learns from a wider range of peer companies, market leaders, and channel partners.

Our company is willing to actively conduct market experiments or tests based on our market forecast.

FIRM PERFORMANCE

Our company has achieved a high level of return on sales.

Our company has achieved a higher level of customer loyalty.

Our company has achieved a high level of return on investment.

Our company has achieved a high level of profitability.

Our company has achieved high customer acquisition

RESOURCE ORCHESTRATION CAPABILITIES

We can combine capabilities to create value for our customers

We can modify existing or internal capabilities for our marketing capabilities

We are proactive in obtaining current marketing information

We are effective in divesting accumulated marketing information to achieve our goal

We can combine the right set of capabilities for marketing functions