?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper aimed to examine the empirical analysis of currency devaluation, external debt to GDP growth rate and output growth dynamics in Ethiopia. To achieve this objective, time series data covering from 1991 to 2022 was used and it was examined using an Auto Regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model. The estimation results show that devaluation, the external debt-to-GDP growth rate, and economic growth are all significantly correlated and are co-integrated in the long run. This study found that devaluation has positive long-run effect on output growth, while the external debt-to-GDP growth rate has negative long-run effects on output growth. In addition, the results revealed that inflation had positive effects on economic growth both in the short and long run, while, private investment had negative effects on economic growth both in the short and long run respectively. In general, the study found that there is no short-run connection between devaluation, the external debt-to-GDP growth rate, and economic growth; nevertheless, in the long run, devaluation lowers external debt by boosting exports and promoting economic growth. Additionally, long-run economic growth in the country is positively impacted by spending on education and the availability of real money supply. This study suggests that the government should improve economic growth by enhancing allocation for education to improve its quality, control inflation and money supply, and promoting devaluation to check their effects on the economy.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Our country, Ethiopia, is one of the top debtors in Africa and has devalued its currency repeatedly in different regime in different time to boost exports, reduce the debt burden, shrink trade deficits, increase investment, and spur economic growth. However, the country still faces a shortage of foreign currency, external debt vulnerabilities, and low economic growth. To this end, macroeconomic imbalances are a critical problem in the country. Thus, it is critical to examine the dynamic effects of devaluation, external debt to GDP ratio and output growth in the country. Thus, the researcher tried to do so.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

In developing countries, external debt and exchange rates are major macroeconomic policy issues. Recently, Ethiopia has been one of the top debtors in Africa and has devalued its currency; however, the country continues to have a foreign exchange shortage, which has an impact on the economy (International Monetary Fund (IMF), Citation2019; IMF, Citation2020 report). According to (Taye, Citation1999; Imimole & Enoma, Citation2011; International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2014; Medina, Citation2015; Fassil, Citation2017; Momodu & Akani Citation2016; Taye, Citation1999) devaluation is a key strategy for solving economic issues by enhancing the trade balance, which lowers external debt and increases foreign exchange reserves. However, various studies show that developing nations are ineffective in meeting the goals of the IMF, which promotes economic growth through devaluation and external debt (IMF, Citation2019).

In Ethiopia, there has been a sharp decrease in the export of coffee, oil seed, and other exported commodities during the last five years owing to the highly fluctuating commodity price in the international market due to the improved strength of US dollar over Ethiopian currency. Thus, cognizant of this fact, the National Bank of Ethiopia devalued its currency by 15% in 2017. During this period, devaluation accelerated inflation (CSA, Citation2018). In parallel, starting from the transition government up to the present time, the Ethiopian government devalues its currency and increases its debt from foreigners to tackle the problem of external shock, boost exports, reduce the debt burden, shrink trade deficits, increase investment, and spur economic growth. However, the country still faces a shortage of foreign currency, external debt vulnerabilities, and low economic growth (Elias et al., Citation2023; IMF, Citation2020 report). However, economic theory suggests that devaluation is likely to boost economic growth by expanding exports in the long run (Marshall, Citation1923; Lerner, Citation1944; Fleming, Citation1962; Mundell, Citation1963; Musila & Newark, Citation2003; Ogundipe et al., Citation2013; and IMF, Citation2014; Fassil, Citation2017; and Kyophilavong et al., Citation2019; Elias et al., Citation2023).

In developing countries in general, and in Ethiopia in particular, the persistent and wider spread of foreign exchange shortages and external debt vulnerabilities challenge macroeconomic policymakers. Hence, currency devaluation and external debt have a controversial impact on the economic growth of third world nations, and policymakers face a dilemma in promoting economic growth with the policy instruments of devaluation and foreign debt. However, policy framework is ineffective in many developing countries. In addition, previous findings in low-income countries revealed that devaluation and external debt individually would have a positive impact on economic growth (e.g. Elias et al., Citation2023; Fassil, Citation2017; Hanna, Citation2013; Kouladoum, Citation2018; Kyophilavong et al., Citation2019; Okaro, Citation2017; Palić et al, Citation2018; Taye, Citation1999), while others found a negative impact on economic growth (e.g. Mironov, Citation2015; Ramakrishna, Citation2003; Teklu et al., Citation2014; Tirsit, Citation2011; Yigermal, Citation2018) and while others found an insignificant effect on economic growth (e.g. Yilkal, Citation2014). This indicates that the issue is still debatable, a hot issue, and practically does not address the problem of such individual effects.

Thus, this study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, most previous studies have focused on examining the individual effects of devaluation and external debt on economic growth (e.g. Elias et al., Citation2023; Fassil, Citation2017; Hanna, Citation2013; Taye, Citation1999). However, evidence shows that there are dynamics in currency devaluation, external debt, and output growth. Thus, this study attempted to provide empirical evidence of devaluation, external debt-to-GDP ratio, and economic growth dynamics. Second, previous studies, such as (Hanna, Citation2013; Kharusi & Ada, Citation2018; Ramakrishna, Citation2003) used nominal figures of external debt to examine its effect on nominal economic growth. However, it is advisable to use the external debt-to-GDP ratio with real output growth (Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP) rather than external debt with GDP because nominal external debt and nominal economic growth (GDP) are less sound in measuring output growth relative to the external debt-to-GDP ratio and real output growth. Thus, we use the relative term (external debt to GDP ratio and real output growth) in order to clearly understand its real effect, and the relation with real economic growth linkage is preferable to make it sounder. Third, most previous studies have shown inconclusive results on devaluation, external debt, and economic growth linkages. Fourth, besides the exchange rate and debt-to-GDP ratio, our study includes the most important determinants of output growth, such as (real money supply, private investment (foreign and domestic investment), and expenditure on education) which other studies do not consider them (e.g. Medina, Citation2015; Palić et al, Citation2018). Finally, this paper’s findings can be the guidelines for countries devalued their currency but with no significant improvement were noted in exports and other macroeconomic variables. Instead, inflation increased and country faced shortage of foreign currency, external debt vulnerabilities, and stagnant economic growth due to wrong policies of the country’s economy. This issue mimics the situation in Ethiopia, and the problem is still rampant. So, by providing Ethiopia with a case study of how currency devaluation affects the external debt-to-GDP ratio and economic growth dynamics in Ethiopia, our results provide a powerful understanding of what is happening in other parts of the world, particularly in many African countries. The results of this study can be used for future decision-making purposes for the poor countries of these regions and can greatly benefit scholars and professionals in these countries. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to empirically analyze how currency devaluation affects the external debt-to-GDP ratio and economic growth dynamics in Ethiopia covering from the period between 1991–2022.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides data description and research methodology, Section 3 reports the results and discussion of the results, and Section 4 provides the conclusions and recommendations of the study.

2. Data and methodology

The study is based on macroeconomic data ranging from 1991 to 2022 to objectively examine the short- and long-run connections between currency devaluation, the external debt-to-GDP ratio, and economic growth in Ethiopia. The relevant data were collected from the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MOEFD), the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC), and the Ethiopian Economic Association (EEA). To maintain consistency, data were collected from internal sources. provides variable description and hypothesis of the study. Our model is built based on the theoretical and empirical literatures and we have selected our variables according to the economic theories which are developed by (Marshall, Citation1923; Lerner, Citation1944; Fleming, Citation1962; Mundell, Citation1963; Taye, Citation1999; Imimole & Enoma, Citation2011; Musila & Newark, Citation2003; Ogundipe et al., Citation2013; IMF, Citation2014; Medina, Citation2015; Fassil, Citation2017; Momudu & Akani Citation2016; and IMF, Citation2020; Elias et al., Citation2023) as currency devaluation is a key strategy for solving economic issues by enhancing the trade balance, which lowers external debt and increases foreign exchange reserves, implying devaluation boost exports, reduce the debt burden, shrink trade deficits, increase investment, and spur economic growth. Accordingly, for the above mentioned reason and data availability, we have selected variables of Real GDP, Exchange rate as a proxy for devaluation, external debt to GDP ratio, Real money supply, Government expenditure on education, inflation and private investment as these variables are interrelated.

Table 1. Variable description and hypothesis of the study.

2.1. Method of analysis

2.1.1. ADF unit root test

Prior to the empirical estimation, a unit root test (stationarity) is essential. It is useful to understand how a variable behaves through the order of integration when setting up an econometric model and drawing conclusions. Before building an econometric model and drawing conclusions, it is also helpful to examine the characteristics of the variables in the model (Sjö, Citation2008). To prevent erroneous conclusions or false regressions, it is critical in time-series econometrics to determine the variables’ stationarity or non-stationarity status (Libanio, Citation2005). John et al. used a unit root test to verify that the sequence of integration is critical for ensuring the presence of co-integration linkages. When the mean, variance, and covariance remain constant, the data are said to be stationarity in time-series econometrics.

2.1.2. Econometrics model specification

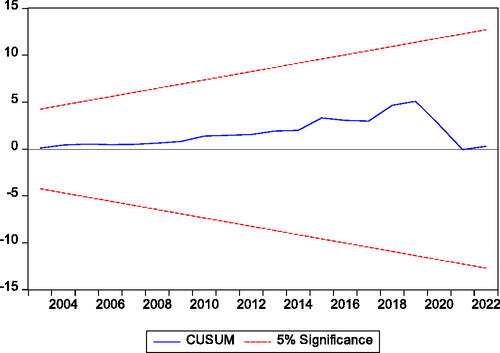

The autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) technique was used in this study to show both the short- and long-term trends among the chosen variables. The model was created by (Pesaran et al., Citation2001; Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998) created the model to examine how variables co-integrate. The ARDL model, which is one of the most frequently used models in macroeconomics, was used in this study. Compared with other methods, the proposed model offers numerous benefits. First, the model with relation to VAR is flexible regarding stationarity on both I(0) and I(1). Second, compared with the Johanson cointegration approach, it is more effective when dealing with small and finite data sample sizes (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). Third, using the ARDL model, unbiased long-term estimates are achieved when some independent variables are endogenous (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998). Fourth, compared with other models, the ARDL model estimates only one equation using the OLS method (Srinivasana & Kalaivani, Citation2013). This study used the ARDL model, which is typically used in empirical work, based on these benefits. The study aimed to examine a few diagnostic tests in this study before determining the ARDL model. The following tests were used to ensure the reliability and stability of the ARDL model: stationarity test (Dickey & Fuller, Citation1979; Perron, Citation1990), evaluation of maximum lag length, testing co-integration, Wald test, Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test, Heteroscedasticity test, and Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) test.

Van and Bao (Citation2019) cited Pesaran and Shin (Citation1998) who proposed the general form of the equation of ARDL model, which is given below:

(1)

(1)

where

is the dependent variable, X’s are independent variables, p is the lag order of the dependent variable of Y, q’s are the lag order of the explanatory variable of X’s,

are coefficients of the variables in the model. In addition, because all long-run relationship variables are specified and not restricted, the unrestricted error correction model can be given as:

(2)

(2)

In the model, the estimated coefficients attached to the first-differenced variables indicate short-run effects, whereas the long-run effects are shown by the estimates of parameter . Based on the work of (Pesaran et al., Citation2001; Bahmani-Oskooee & Fariditavana, Citation2016; Bao & Van, Citation2018; Van & Bao, Citation2019) from the above model, the hypothesis for testing co-integration can be developed as follows:

:

=

=

=

=

=0 (no co-integration)

:

≠

≠

≠

≠

≠0 (co-integration)

If the F-statistic value is greater than the upper bound critical value at a significant level H1 accepted and Ho is rejected, whereas if the F-statistic value is less than the lower bound critical value, H1 is rejected and Ho is accepted; if the F-statistic value lies between neither of the two, it is inconclusive.

The current paper provided an effort to look at both short run and long run relationships between currency devaluation, external debt, and economic growth. The model was defined in accordance with theoretical and empirical support. In this study, real money supply and inflation are included as policy factors for economic growth in addition to the interest variable (exchange rate and external debt). Debt burden, physical capital, human capital, and other macroeconomic determinants influence economic growth (Calderón & Fuentes, Citation2013).

The theoretical framework is based on the works of (Akpan & Atan, Citation2011; Tirsit, Citation2011; Calderón & Fuentes, Citation2013; Sanya, Citation2013; Fassil, Citation2017) as cited by the scholars, and the model should be employed to follow a plain formulation in the work of various methodological literature. Therefore, utilizing both theoretical and empirical explanations, all significant variables are included in the model, and the model specification is as follows:

(3)

(3)

All the variables are expressed in terms of natural logarithms, except inflation, which is expressed naturally in log form. Where RGDP refers to the real gross domestic product that measures output growth in log form and e refers to the official exchange rate, which is a nominal exchange rate and proxy for devaluation. Additionally, PI refers to private investment and Eexp refers to government expenditure on education. Moreover, RMs refers to real money supply in log form. Finally, refers to external debt to gross domestic, and

is the error term. Thus, the specification of the model is based on the prescription of (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998; Pesaran et al., Citation2001; Van & Bao, Citation2019; Udemba, Citation2020) who pointed out that the ARDL model is suitable for capturing short-run adjustment process of economic growth. Therefore, the model can be expressed as follows:

(4)

(4)

The above equation shows the specifications of the ARDL model. EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) is a long-run model, and EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) indicates the expansion of the ARDL model derived from EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) , ARDL model is used to explain long run and Error Correction Model is used to illustrate short run association between dependent and independent variables.

All the variables are in log form. ,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

are parameters to be estimated. Additionally, the operator

refers to the first difference of variables in the model,

shows the speed of convergence over a long period of time, and the error term is

. Moreover, p and q represent the maximum lag of the variables in the model.

Under this hypothesis, two set of critical values can be developed by (Pesaran et al.,Citation2001). The hypothesis is articulated as follows: = 0 against the alternative,

:

0. The variables in EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) are assumed to be integrated of order zero, I(0),while the other is I(1). If the calculated F-statistics are greater than critical values, we reject the null meaning and conclude that there is co-integration among the variables. On the other hand, If F < critical values, we accept the null meaning and conclude that there is no co-integration relation among the variables. If its value lies between these values, the decision will be inconclusive. Finally, the specification can be formulated as valid in EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) .

3. Discussion

3.1. Unit root test, lag length, and BOUND test

provides reports of the unit root test, which was tested using the ADF and PP tests. The test results show that the variables government expenditure on education (EEXP) and inflation (INF) are stationarity at level, that is, integrated order 0 I(0). The remaining variables are non-stationarity at this level. However, all the variables are stationarity at their first difference, which integrates order 1 I(1). In addition, the test result confirmed that the ARDL model can be used if variables are stationers at I(0) and I(1), or a combination of I(0) and I(1). Thus, the test confirms the use of the ARDL model.

Table 2. Unit root test at level and first difference.

provides the lag length determination, and the test result indicates the determination of lag length. Akaki Information Criteria is chosen for the study because the minimum figure indicates that the model is better and it is more common below 60 observations from the empirical suggestion. The result provides one optimal lag length at the 10% significance level.

Table 3. Determination of lag length.

Bound test shows that computed F-statistics result provides stable co-integration test and the test result indicates that the computed F-statistics value (15.56) is higher than the upper bound critical values at 1% level of significance. Hence, the null hypothesis of co-integration is rejected that is a stable long run co-integration among the variables. It shows that the series cannot move independent of each other.

Table 4. Bound test.

Generally, the results in confirm that currency devaluation and external debt jointly cause RGDP because the F-statistics are higher than the upper bound value, and the P value is significant; hence, there is a stable long-run relationship between the variables. This indicates that currency devaluation and external debt coexist in the long run. This shows that currency devaluation reduces external debt by exporting more, and promotes economic growth in the long run.

3.2. Empirical short run and long run result

presents the estimated coefficients of the short-run dynamics of the error correction model. The results showed that private investment has a significant and negative impact on real GDP, and real money supply adversely affects economic growth in the short run. Whereas, the result indicates that inflation has a significant and positive impact on real GDP in the short run. In detail, if one unit increases in volume of private investment the quantity of real money supply will decrease by 6% and output growth by 3.6% respectively. While, if one unit increases in inflation rate the output growth will likely to be decreased by 4%. Moreover, in the short run, the currency devaluation, government expenditures on education, and external debt-have statistically insignificant relationship with GDP growth rate as there is no significant relationship between these variables in the short run. Besides, the result shows that the error-correction term (ECt-1) has a negative sign and is statistically significant. This confirms there is a long run relationship between variables or have co-integration among the variables. The estimated value of ECMt-1 was 0.722749. The value indicates that the whole system is adjusted at a speed of 72.3% towards the long-run equilibrium. That is, the speed of adjustment can return to long-run equilibrium at 72.3% following short-run shocks.

Table 5. Estimated coefficients of short run dynamics error correction model.

presents the estimated long run results of this study. The result indicates that the nominal exchange rate is significant and positively affects real gross domestic product at five percent level of significance. This indicates that devaluation tends to increase economic growth in the long term. Devaluation encourages exports and citizens to turn to domestic products and produce more outputs in the long run. This is supported by the Marshall (Citation1923) and Lerner (Citation1944) and the IMF strategy (Citation2014). This finding is consistent with Okaro (Citation2017) in Nigeria, Fassil (Citation2017) in Ethiopia, and Kyophilavong et al. (Citation2019) in Laos; Elias et al. (Citation2023) in Ethiopia. In the long run, a one percent increase in exchange rate (proxy for Devaluation), expenditure on education, real money supply and inflation will leads to about 37.6%, 16.7%, 54%, and 1.3% on output growth while, a one unit increase in external debt to GDP ratio and private investment will have a negative impact on output growth by 31.4% and 30% respectively.

Table 6. Estimated long run results1.

In addition, in the long run, government expenditure on education (EEXP) has a positive and significant impact on real gross domestic product. This is consistent with (Chu et al., Citation2019; Hussin et al., Citation2012 in Malaysia; Keller, Citation2006 in Kenya; Mallick et al., Citation2016 in Asian countries; Tamang, Citation2011 in India). Moreover, inflation has a statistically significant and positive impact on real GDP in the long-run. This is because high inflation is positively affected economic growth by contributing creation of a low unemployment rate. Moreover, inflation causes individuals to substitute out of money into interest earning assets, which leads to greater capital increasing and promotes economic growth. Therefore, inflation exhibits a positive relationship to economic growth.

This is consistent with (Hussain & Malik, Citation2011 in Pakistan; Sattarov, Citation2011 in Finland; Xiao, Citation2009 in China) and the real money supply has also positively affected economic growth. The external debt-to-GDP ratio and private investment have a negative impact on Ethiopia’s real GDP in the long run. That is, private investment negatively affects economic growth, either in terms of foreign or domestic investment. The possible reasons for this negative effect is that the foreign private investment adversely affects economic growth because of the lack of freedom from business regulation by the host country, lack of freedom from government intervention, resource dependence of developing countries, internal structural weakness; and domestic private investment, which affect economic growth negatively through investment using backward technology and lack of skilled manpower (Herzer, Citation2012). In addition, (Schoors & van der Tol, Citation2001; Lensink & Morrissey, Citation2006) obtained similar findings. Moreover, the external debt to gross domestic product ratio negatively affects economic growth. That is, a higher level of indebtedness and an increase in the proportion of external debt to the gross domestic product ratio decreases economic growth. This may arise from a bad debt management policy and excessive borrowing. This is similar to (Asteriou et al., Citation2021; De Vita et al.,Citation2018; Makun, Citation2021 in pacific island countries; Sharaf, Citation2022 in Egypt; Shkolnyk & Koilo, Citation2018 in Ukrain; Toktaş et al., Citation2019 in Turkey; Were, Citation2001 in Kenya, Teklu et al., Citation2014 in Ethiopia, Kharusi & Ada, Citation2018 in Oman’s economy).

Finally, analyzing the stability of short- and long-run series using the Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) is vital in the ARDL model. shows the results of CUSUM. The CUSUM figure shows that the blue line is between the two red lines, so that the model is stable at the 5% level of significance.

4. Conclusion and policy implications

The main purpose of this study was to empirically investigate the short- and long-term trends in Ethiopia’s currency devaluation, external debt-to-GDP ratio, and economic growth. Using yearly time-series data for 1991 to 2022, the empirical study was estimated using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model. The results of the study revealed that the devaluation is negatively and insignificantly related to the RGDP in the short run, while a positive and significant relationship exists in the long run. It implies that devaluation initially causes deterioration; however, short-run currency devaluation has no effect on Ethiopia’s RGDP and leads to an expansionary effect on RGDP in the long run. This implies that long-run economic growth is more effectively stimulated by devaluation than short-term growth. This is in line with the theoretical logic supported by the Marshal Lerner Condition, which states that currency devaluation increases exports and decreases imports, leading to a decrease in external debt through an increase in export revenue, and again is consistent with the IMF strategy. In developing countries, currency devaluation and external debt are important options to promote economic growth as prescribed by International Monetary Fund. This result is against the situation in Ethiopia, where she devalued its currency by 15% in 2017 but no significant improvement was noted in exports and other macroeconomic variables. This is because of the sum of the demand elasticities of import and export is less than unity in Ethiopia, which does not satisfy the condition in the short run. Additionally, devaluation is likely to increases domestic inflation because imported materials will be more expensive, expands aggregate demand, and firms can depend on the devaluation to increase their competitiveness, so they have less incentive to reduce expenses. This is may be due to the wrong policies of the country’s economy and policy intervention in the form of devaluing the domestic currency could be effective in improving export performance, economic growth, and lowers external debt given that the effect of inflation and other macroeconomic variables on output is controlled. Again, due to the time required to produce the commodities and the insufficient capacity of Ethiopia’s export industry to promptly satisfy foreign demand, the production and supply of the agriculture sector is inelastic to changes in exchange rates (Elias et al., Citation2023).

Consequently, this study suggests that devaluation is a key strategy for boosting Ethiopia’s economy in the long run. In order to achieve its intended purpose through devaluation policy (i.e. expansion of exports and import substitution to a large extent), the Ethiopian government must control the rising movement of domestic prices, demand management measures, policies that convert an initial increase in supply into an increase in actual exports, thereby further depreciating the currency in the long term, encouraging more exports, and thus promoting economic growth. This finding is consistent with the empirical evidences supported by Medina (Citation2015), Fassil (Citation2017), Kyophilavong et al. (Citation2019), and Elias et al. (Citation2023) as devaluation enhances the trade balance, which lowers external debt and increases foreign exchange reserves overtime. Moreover, the results showed that the ratio of external debt to GDP had a negative effect on economic growth; thus it should be the concern for the government of the country. Policies that address only one aspect of macroeconomic instability, however, might not be sufficient to stimulate economic growth. Furthermore, long-term economic growth has been positively impacted by government expenditure on education, inflation, and the real money supply. Therefore, in addition to devaluation, the government should concentrate on addressing the issues of educational spending and human development. Both the long- and short-run economic growth are positively influenced by inflation. This runs counter to the principles of monetary economics and earlier findings in Ethiopia. Thus, further investigation is required. Finally, improving the real money supply, controlling inflation and promoting devaluation will helps to spur economic growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tesfahun Ayanaw

Tesfahun Ayanaw the author of this article, is MSc in Development Economics holder from Bahir Dar University. Currently, I am working for Woldia University as a lecturer. I am interested in conducting a study on economic growth, development and macroeconomic issues.

Samuel Godadaw

Samuel Godadaw has MBA in Management from Bahir Dar University and currently he is working for Woldia University as a lecturer.

Yigermal Maru

Yigermal Maru has MSc in International Economics from Addis Ababa University and he is serving Woldia University as a lecturer.

Mesele Belay

Mesele Belay has MSc in Development Economics from Debre Berhan University and he is serving Woldia University as an assistant professor.

Tilahun Getnet

Tilahun Getnet has MBA in management from Bahir Dar University and currently he is working for Woldia University as a lecturer.

References

- Akpan, E. O., & Atan, J. A. (2011). Effects of exchange rate movements on economic growth in Nigeria. CBN Journal of Applied Statistics, 2(2), 1–11.

- Asteriou, D., Pilbeam, K., & Pratiwi, C. E. (2021). Public debt and economic growth: Panel data evidence for Asian countries. Journal of Economics and Finance, 45(2), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-020-09515-7

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Fariditavana, H. (2016). Nonlinear ARDL approach and the J-curve phenomenon. Open Economies Review, 27(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-015-9369-5

- Bao, H. H. G., & Van, D. T. B. (2018). Testing J-curve phenomenon in Vietnam: An autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach. In International Econometric Conference of Vietnam (pp. 491–503). Springer.

- Calderón, C., & Fuentes, J. R. (2013). Government debt and economic growth (No. IDB-WP-424). IDB Working Paper Series.

- Central Statistical Agency. (2018). Government of Ethiopia, General year-on-year inflation increases, http://www.ena.gov.et/en/index.php/economy/item/4263.

- Chu, A. C., Ning, L., & Zhu, D. (2019). Human capital and innovation in a monetary Schumpeterian growth model. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 23(5), 1875–1894. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1365100517000487

- De Vita, G., Trachanas, E., & Luo, Y. (2018). Revisiting the bi-directional causality between debt and growth: Evidence from linear and nonlinear tests. Journal of International Money and Finance, 83, 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2018.02.004

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/2286348

- Elias, A., Dachito, A., & Abdulbari, S. (2023). The effects of currency devaluation on Ethiopia’s major export commodities: The case of coffee and khat: Evidence from the vector error correction model and the Johansen co-integration test. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2184447. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2184447

- Fassil, E. (2017). Birr devaluation and its effect on trade balance of Ethiopia: An empirical analysis. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 9(11), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF2017.0864

- Fleming, J. M. (1962). Domestic financial policies under fixed and under floating exchange rates. Staff Papers – International Monetary Fund, 9(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.2307/3866091

- Hanna, A. (2013). The impact of external debt on economic growth of Ethiopia. [Doctoral dissertation]. St. Mary’s University.

- Herzer, D. (2012). How does foreign direct investment really affect developing countries’ growth? Review of International Economics, 20(2), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2012.01029.x

- Hussain, S., & Malik, S. (2011). Inflation and economic growth: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(5), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v3n5p262

- Hussin, M. Y. M., Muhammad, F., Hussin, M. F. A., & Razak, A. A. (2012). Education expenditure and economic growth: a causal analysis for Malaysia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(7), 71–81.

- IMF. (2014). ‘Ethiopia: 2014 Article IV Consultation’, Washington D.C.

- IMF. (2019). ‘Ethiopia: 2019 Article IV Consultation’, Washington D.C.

- IMF. (2020). ‘World economic outlook update, June, 2020.

- Imimole, B., & Enoma, A. (2011). Exchange rate depreciation and inflation in Nigeria (1986-2008). Business and Economics Journal, 28(1), 1–11.

- Keller, K. R. (2006). Investment in primary, secondary, and higher education and the effects on economic growth. Contemporary Economic Policy, 24(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/cep/byj012

- Kharusi, S. A., & Ada, M. S. (2018). External debt and economic growth: the case of emerging economy. Journal of Economic Integration, 33(1), 1141–1157. https://doi.org/10.11130/jei.2018.33.1.1141

- Kouladoum, J. C. (2018). External debts and real exchange rates in developing countries: evidence from Chad.

- Kyophilavong, P., Shahbaz, M., Lamphayphan, T., Kim, B., & Wong, M. C. (2019). Are devaluations expansionary in Laos? Global Business Review, 20(1), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918803996

- Lensink, R., & Morrissey, O. (2006). Foreign direct investment: Flows, volatility, and the impact on growth. Review of International Economics, 14(3), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2006.00632.x

- Lerner, A. P. (1944). Economics of control: Principles of welfare economics. Macmillan and Company Limited.

- Libanio, G. A. (2005). Unit roots in macroeconomic time series: Theory, implications, and evidence. Nova Economia, 15(3), 145–176. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512005000300006

- Makun, K. (2021). External debt and economic growth in Pacific Island countries: A linear and nonlinear analysis of Fiji Islands. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 23, e00197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2021.e00197

- Mallick, L., Das, P. K., & Pradhan, K. C. (2016). Impact of educational expenditure on economic growth in major Asian countries: Evidence from econometric analysis. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 2(607), 173–186.

- Marshall, A. (1923). Money, Credit and Commerce. Macmil lan.

- Medina, M. (2015). Devaluation and its Impact on Ethiopian Economy. Hacettepe University.

- Mironov, V. (2015). Russian devaluation in 2014–2015: Falling into the abyss or a window of opportunity? Russian Journal of Economics, 1(3), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruje.2015.12.005

- Momodu, A., A, &., & Akani, F. N. (2016). Impact of currency devaluation on economic growth of Nigeria. AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 5(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v5i1.12

- Mundell, R. A. (1963). Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 29(4), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/139336

- Musila, J. W., & Newark, J. (2003). Does currency devaluation improve the trade balance in the long run? Evidence from Malawi. African Development Review, 15(2–3), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2003.00076.x

- National Bank of Ethiopia. (2017). Impacts of the Birr devaluation on inflation. https://0x9.me/N85BR.

- Ogundipe, A., Ojeaga, P., & Ogundipe, O. (2013). Estimating the long run effects of exchange rate devaluation on the trade balance of Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 9(25), 233–249.

- Okaro, C. (2017). Currency devaluation and Nigerian economic growth (2000–2015). NG-Journal of Social Development, 6(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.12816/0040235

- Palić, I., Banić, F., & Matić, L. (2018). The analysis of the impact of depreciation on external debt in long run: Evidence from Croatia. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 16(1), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.16.1.15

- Perron, P. (1990). Testing for a unit root in a time series with a changing mean. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 8(2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.2307/1391977

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econometric Society Monographs, 31, 371–413.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Ramakrishna, G. (2003). External debt of Ethiopia: an empirical analysis of debt and growth. Journal of Business & Public Affairs, 30, 29–35.

- Sanya, O. (2013). The causative factors in exchange rate behaviour and its impact on growth of Nigerian economy. European Scientific Journal, 9(7), 288–299.

- Sattarov, K. (2011). Inflation and Economic Growth. Analyzing the Threshold Level of Inflation.: Case Study of Finland, 1980–2010.

- Schoors, K., & van der Tol, B. (2001 The productivity effect of foreign ownership on domestic firms in Hungary [Paper presentation]. EAE Conference in Philadelphia, PA.

- Sharaf, M. F. (2022). The asymmetric and threshold impact of external debt on economic growth: new evidence from Egypt. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 2(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-06-2021-0084

- Shkolnyk, I., & Koilo, V. (2018). The relationship between external debt and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Ukraine and other emerging economies. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 15(1), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.15(1).2018.32

- Sjö, B. (2008). Testing for unit roots and cointegration. Lectures in Modern Econometric Time series Analysis, memo.

- Srinivasan, P., & Kalaivani, M. (2013). Determinants of Foreign Institutional Investment in India: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Academic Research in Economics, 5(3).

- Tamang, P. (2011). The impact of education expenditure on India’s economic growth. Journal of International Academic Research, 11(3), 14–20.

- Taye, H. (1999). The impact of devaluation on macroeconomic performance: The case of Ethiopia. Journal of Policy Modeling, 21(4), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-8938(97)00110-5

- Teklu, K., Mishra, D. K., & Melesse, A. (2014). Public external debt, capital formation and economic growth in Ethiopia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5, 58–70.

- Tirsit, G. (2011). Currency Devaluation and Economic Growth: The case of Ethiopia, Departments of Economics, Stockholm University. Dostupno na. http://www.ne.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.25800, 1318417049.

- Toktaş, Y., Altiner, A., & Bozkurt, E. (2019). The relationship between Turkey’s foreign debt and economic growth: an asymmetric causality analysis. Applied Economics, 51(26), 2807–2817. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1558360

- Udemba, E. N. (2020). Ecological implication of offshored economic activities in Turkey: foreign direct investment perspective. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 27(30), 38015–38028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09629-9

- Van, D. T. B., & Bao, H. H. G. (2019). A nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) analysis on the determinants of Vietnam’s stock market. In International Econometric Conference of Vietnam (pp. 363–376). Springer.

- Were, M. (2001). The impact of external debt on economic growth in Kenya: An empirical assessment. (No. 2001/116). WIDER Discussion Papers. World Institute for Development Economics (UNU-WIDER).

- Xiao, J. (2009). The relationship between inflation and economic growth of China: empirical study from 1978 to 2007.

- Yigermal, M. (2018). Devaluation, Balance of payment and Output Dynamics in developing countries (The case of Ethiopia). Addis Ababa University.

- Yilkal, W. (2014). The effect of currency devaluation on output: The case of Ethiopian economy. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 6(5), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF2013.0548