Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine and understand the impact of green packaging on consumer legitimacy through green perceived value. Data were collected from 331 customers of cosmetic products in Tanzania. The study used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships between the variables. The proposed research model was largely supported, and the mediating role of green perceived value in this model was confirmed. Green packaging was found to be more determinative of consumer legitimacy. Additionally, novelty-perceived green value was found to mediate the association between green packaging and consumer legitimacy. Based on the study’s findings, this study provides specific theoretical and practical implications.

Introduction

A roadmap towards the UN SDGs 2030 agenda promotes the participation of various stakeholders, including marketers, in achieving ethical production and consumption as part of the SDGs (Gomez-trujillo et al., Citation2021; Shukla et al., Citation2022). Hence, producers are pressured to become environmentally friendly in their operations (Zsigmond et al., Citation2021). Customers expect producers to produce product brands that not only consider emotional and functional values but also societal value. While the notion that brands should offer functional and emotional values is well-established in consumer research (Amani, Citation2022; Amani & Ismail, Citation2022), research on how societal value can be used to build a competitive edge for business firms is scarce. Recent academic literature indicates that consumers have increasingly turned their attention to societal value or social acceptance as important criteria for choosing brands (Miotto & Youn, Citation2020). The term “societal value” consists of specified standards that a given society or social group uses to define acceptable behaviors, shaping the nature and form of social order in a collective i.e., what is acceptable and not acceptable, what ought or not to be, and what is desirable or undesirable (Ismail et al., Citation2023). Given the growing importance of societal value or social acceptance in determining consumer brand choice, marketing scholars have recently focused on aligning and streamlining marketing practices with United Nations SDGs on ethical production and consumption (Deloitte, Citation2018; Gomez-trujillo et al., Citation2021). Chen and Lee (Citation2022) argue that the consumer’s choice is based not only on the functional and emotional benefits of the product brand but also on the ethical practices associated with the product brand. Despite the increasing importance of societal value in choosing brands, no agreement has yet been reached on what drivers can enhance consumer influence and encourage them to assign societal value to brands (Amani, Citation2022; Ismail et al., Citation2023; Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020).

Research in the stream of eco-friendly packaging indicates that in a mature marketplace, ethical brands adapt to and fulfill societal needs in socially and environmentally demanding settings (Machová et al., Citation2022; Miotto & Youn, Citation2020; Zsigmond et al., Citation2021). Ethical brands promote and encourage production and consumption systems that respect societal needs, social justice, and environmental sustainability (Jaini et al., Citation2020a; Machová et al., Citation2022). On top of that, a relationship between a consumer and a brand that is based on the ethical values of the brand can increase the consumer’s intent to buy (Chen & Lee, Citation2022). The global Buying Green Report indicates that 67% of consumers find the recyclability of packaging important (Buying green report, Citation2021). Furthermore, 73% of consumers are willing to pay more for eco-friendly packaging (Buying green report, Citation2021). The study by Gekonge et al. (Citation2021) in the East African region indicates that 56% of consumers agree that consumption activities, including the purchase and use of various fast-moving consumer goods, have an impact on the environment. Furthermore, Sambu (Citation2016) claims that businesses that invest in green packaging have a 56.6% chance of improving their performance. Chao and Uhagile (Citation2022) investigate the impact of consumer perceptions of green food products on purchasing behavior in a Tanzanian context and discover that consumer perceptions of green food products influence actual purchasing behavior. In addition, the study by Machová et al. (Citation2022) unveils that 15% of consumers perceive eco-friendly packaging as very important. 25.8% find it important, 31.7% feel eco-friendly packaging is moderately important, 19.7% are rather less interested, while 7.8% do not find it important at all. Overall, these findings suggest that, on average, 72.5% of consumers consider eco-friendly packaging as relevant in their purchase decision-making.

The seminal works in ethical branding suggest that consumer-brand relationships grow due to consumer identification with a product brand’s ethical position and practices. Miotto and Youn (Citation2020) argue that this isomorphism between product brands and consumers’ social norms or values leads to consumer legitimacy. It is widely accepted that consumer legitimacy contributes to building a competitive advantage in all industries (Amani, Citation2022). Branding products in a way that is good for the environment is very important in the cosmetics industry (Jaini et al., Citation2020a; Suphasomboon & Vassanadumrongdee, Citation2022). This is because the cosmetics industry has been criticized by society for having an effect on environmental problems, especially packaging pollution (Chun, Citation2016; Jaini et al., Citation2020a). To address this significant environmental issue, practitioners in the cosmetics industry have recently adopted and executed novel solutions to minimize the negative social and environmental impact of their business model and enhance their legitimacy (Chen & Lee, Citation2022; Miotto & Youn, Citation2020). Borah et al. (Citation2021) argue that businesses should act in a way that is socially and environmentally responsible to keep the support of stakeholders and meet the ever-growing expectations of consumers. This implies that business firms should adopt business models that are guided by business ethics rules and principles (Juliana et al., Citation2020). Business ethics rules and principles should ensure business firms respect stakeholder interests and societal needs while achieving a global long-term vision (Suphasomboon & Vassanadumrongdee, Citation2022). Ethical branding practices, including green packaging, involve demonstrating integrity, accountability, responsibility, and respect for potential stakeholders (Wandosell et al., Citation2021; Zsigmond et al., Citation2021).

Empirical evidence in ethical brand practices suggests that an ethical brand makes decisions that intend to present itself as good for the public, which can enhance its competitive advantage (Lialiuk et al., Citation2019). Thus, to achieve success, an ethical brand should strike a balance between the accomplishment of functional and representational issues that can enhance the ethical meaning and purpose that connect the brand and consumers (Papaluca et al., Citation2020). Although the number of consumers who are environmentally conscious is increasing, determinative factors of consumers’ ethical consumption are low (Miotto & Youn, Citation2020). Furthermore, the antecedents and consequences of various consumers’ attitudes towards ethical practices are still new in the field of study (Jaini et al., Citation2020a; Suphasomboon & Vassanadumrongdee, Citation2022). Evidence indicates that there are few empirical studies that examine ethical practices such as green packaging and their consequences mainly in building the competitive edge of business firms (Wandosell et al., Citation2021). Some of those few studies include the study by Miotto and Youn (Citation2020), who suggest that fast fashion retailers’ sustainable collections have a direct impact on corporate legitimacy. In addition, Alwi et al. (Citation2017) discovered that ethical branding mediates the relationship between product quality, service quality, perceived price, company reputation, and brand loyalty. Payne et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate that ethical behaviors are vital for gaining corporate legitimacy and, therefore, for improving business performances. Chen and Lee (Citation2022) discovered that green brand legitimacy has a positive impact on trust in green brands. Although in the ethical branding domain, corporate legitimacy has been considered an important strategic resource to enhance competitiveness (Payne et al., Citation2021), little is known about customers as legitimacy-granting constituents (Amani, Citation2022).

Hence, it is widely accepted that the link between ethical practices and brand performance in the milieu of ethical branding is an under-researched area (Alwi et al., Citation2017; Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). In addition, the role of customers as legitimacy-granting constituents has not been well examined in the ethical branding domain (Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). The role of customers as legitimacy-granting constituents is due to the idea that ethical brand identity is constructed in a situation where an organization is considered a citizen of a society with rights and responsibilities (Amani & Ismail, Citation2022). The current global agenda on ethical product production and consumption emphasizes the need to establish consumer attitudes towards business models that promote ethical practices, such as green packaging. As noted by Amani and Ismail (Citation2022), the consequences and antecedents of ethical branding practices are still in their infancy in the marketing domain. In particular, previous studies lack empirical guidance regarding ethical branding practices and their influence at the corporate level, including consumer legitimacy (Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). This study intends to investigate ethical branding and corporate legitimacy in the cosmetics industry as a very emblematic and potential example of an industry that faces criticism on environmental issues. The study aims to examine whether ethical branding practices in the cosmetics industry, i.e., green packaging, have a positive impact on consumer legitimacy. It is expected that the study can contribute to the research agenda on ethical brand practices and their influence on consumer legitimacy in social and environmental contexts. The study used the cognitive-affective-conative model by Hilgard (Citation1980) to explain the interplay between green packaging, green perceived value, and consumer legitimacy. According to this model, green packaging is in the cognitive domain, which includes knowledge and understanding; perceived green value is in the affective domain, which includes consumers’ preferences for green packaging; and consumer legitimacy is in the conative domain, which includes goal-directed action related to the effect of green packaging and perceived green value. Thus, this study aims to address the following objectives:

RO1: To examine the impact of green packaging on consumer legitimacy.

RO2: To examine the impact of green packaging on perceived green value.

RO3: To examine the impact of perceived green value on consumer legitimacy.

RO4: To examine the mediating role of perceived green value in the relationship between green packaging and consumer legitimacy.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Cognitive-affective-conative model

This study adopted the Cognitive-Affective-Conative model to explain the interplay between green packaging, green perceived value, and consumer legitimacy. The Cognitive-Affective-Conative Model suggests that people have three important states of mind, which are cognitive, affective, and conative (Hilgard, Citation1980). Based on this model, various studies incorporated a taxonomy with multiple mental states, which are cognitive, affective, and conative, in explaining sustainable consumption (Quoquab & Mohammad, Citation2020). Magnier and Schoormans (Citation2015) describes these mental states in terms of sustainable consumption in three domains: the cognitive domain represents a person’s knowledge and awareness associated with a particular object. In the context of sustainable consumption, the cognitive domain represents the person’s understanding of the attributes of green products (Quoquab & Mohammad, Citation2020). Overall, it is likely that knowledge about sustainability and environmental features can develop consumers’ sustainable consumption. The affective domain signifies a person’s liking, disliking, and preference (Magnier & Schoormans, Citation2015). This study investigates the possibility that a person’s preference and liking for sustainable consumption can increase sustainable consumption. The conative domain is a psychological domain of behavior or mental processes associated with goal-directed action (Hilgard, Citation1980). It is anticipated that the more a person has the desire to behave sustainably and to care for the environment, the more he or she will consume sustainably.

Consumer legitimacy

Scholars and practitioners are more focused on promoting brands that consider social values, justice, and environmental sustainability. It is argued by Chen and Lee (Citation2021) that brand legitimacy is an intangible asset that business firms could strive to acquire in today’s competitive business settings. Payne et al. (Citation2021) and Yang et al. (Citation2021) agree that brand legitimacy is an intangible asset that allows businesses to gain a competitive advantage over competitors. Brand legitimacy is an outcome of the ethical practices of business firms, which involve practices during an encounter between staff and other stakeholders, particularly customers. Chen and Lee (Citation2021) insisted that brand legitimacy is developed when a business firm responds to various stakeholders’ needs and expectations and demonstrates socially responsible behaviors. In this line of argument, Hu et al. (Citation2018) and Miotto and Youn (Citation2020) cemented that brand legitimacy represents practices guided by specific business ethical rules and principles. Overall, the isomorphism between brand ethical practices and customers’ social values and justice gives birth to consumer legitimacy It is argued by Yang et al. (Citation2021) that consumer legitimacy is general customers’ or the public’s assumption or perception that certain business firms and their brands demonstrate actions or practices that are appropriate and right within socially constructive systems of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions. consumer legitimacy is granted if specific business firms and their brands demonstrate behaviors, values, and beliefs shared with different stakeholders, including customers and the general public (Martín-de Castro, Citation2021). Consumer legitimacy consists of ethical dimensions such as respect for stakeholders’ interests, written and unwritten human rights, environmental issues, etc. (Chen & Lee, Citation2021; Ikram et al., Citation2021). It indicates an ethical brand that engages in practices with respect, integrity, responsibility, and accountability to its stakeholders, notably its customers and the public (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Miotto and Youn (Citation2020) and Yang et al. (Citation2021) pointed out that corporate legitimacy affects the entire business firm’s ethical practices and actions, not specific products or services offered by the business firm. Furthermore, consumer legitimacy embodies a brand whose practices and actions do not harm society; rather, it engages in efforts to promote social welfare and wellbeing. Thus, the ethical practices of a brand that has been granted legitimacy focus on integrity and morality to fulfill the ethical expectations of its stakeholders (Chen & Lee, Citation2021; Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). Consumer legitimacy gives a particular business firm and its brand a sense of legitimacy to exist in a particular industry and market (Hu et al., Citation2018). In modern business, where business firms and their brands should behave morally, a lack of legitimacy implies the firm has no right to exist in the industry or market. This argument is supported by Hakala et al. (Citation2017) that ethical brands demonstrate roles that affect how business firms are socially perceived by the public with whom they interact, either directly or indirectly. Consumer legitimacy indicates business firms’ decision to strike a balance between its functional dimensions and the ethical meaning and purpose they might represent (Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). By striking a balance, business firms may create strong bonds with the community to enhance their competitive edge. Consumer legitimacy influences various forms of behavior, including the intention to participate in ethical purchasing, creating a sense of communal relationship between the brand and customers, society, etc. (Payne et al., Citation2021; Randrianasolo & Arnold, Citation2020). Thus, customers who participate in ethical purchasing often incorporate the ideas of ethics, social values and beliefs, and social justice into every purchase decision. Ethical purchasing means that customers use their moral judgment when making purchases, which is influenced by their own moral beliefs and values (Amani & Ismail, Citation2022).

Green packaging

Product packaging plays a role in communicating the most influential information about a product (Ismail et al., Citation2023; Shukla et al., Citation2022). Product packaging is described as the container for a product, encompassing the physical appearance of the container and including the design, color, shape, labeling, and material used (Lialiuk et al., Citation2019; Lydekaityte & Tambo, Citation2020; Prakash & Pathak, Citation2017). It is the science, art, and technology of enclosing or protecting products for distribution, storage, sale, and use. Packaging is the wrapping of a product that should contain prominent and persuasive information concerning the product and the manufacturer of the product (Magnier & Schoormans, Citation2015; Zsigmond et al., Citation2021). Product packaging is an integral part of a brand and performs key roles in communicating the identity and image of the brand (Mueller & Szolnoki, Citation2010). It is a vital tool in attracting the attention of consumers through the delivery of proper messages that appeal to both emotional and rational aspects (Lydekaityte & Tambo, Citation2020). Product packaging is part of an integrated communication campaign that focuses on branding and positioning the products in the eyes of consumers (Abidin et al., Citation2014; Orquin et al., Citation2020). Product packaging does not only play a conventional role as a protective tool; it is also a useful tool in building an organization’s reputation, providing a first impression regarding a product, and defining the quality of a product (Ketelsen et al., Citation2020; Orquin et al., Citation2020; Underwood & Klein, Citation2002). In order to play this role, product packaging has to contain attractive visual imagery, recognizable characters, color, and design that ensure the products stand out to target consumers. Thus, product packaging is a silent salesman who systematically influences a buyer to develop interest in a given product (Ketelsen et al., Citation2020; Shukla et al., Citation2022).

The term ”green packaging” refers to the science and art of enclosing or protecting goods with the goal of having the least negative impact on the environment (Amoako et al., Citation2022; Orzan et al., Citation2018; Wandosell et al., Citation2021). Due to its use of environmentally friendly production techniques and materials, packaging is also referred to as sustainable or eco-friendly (Maziriri, Citation2020; Molina‐Besch & Pålsson, Citation2016). Green packaging is acknowledged as a sustainable method of wrapping products with very little negative impact on the environment or energy use (Amoako et al., Citation2022; Orzan et al., Citation2018). It is essential for reducing environmental pollution and can lessen the strain on the ecological system. Green packaging is currently the most significant factor in consumer product choice, indicating how much importance customers place on environmental preservation (Herbes et al., Citation2020; Maziriri, Citation2020; Shabbir et al., Citation2020). Given that consumers are becoming more concerned with environmental issues when making purchases, green packaging continues to gain attention among scholars and practitioners in the marketing domain (Borah et al., Citation2021; Boz et al., Citation2020; Han et al., Citation2018). When consumers interact with green packaging, they may determine its value and learn about its advantages for the environment, which raises the perceived value of the brand (Herbes et al., Citation2020; Maziriri, Citation2020). It can be used to show how committed business firms are to environmental sustainability which boost brand recognition (Lialiuk et al., Citation2019). Magnier and Schoormans (Citation2015) argue that adding value to a product through green packaging shapes and reshapes consumer purchase intentions. An innovative green package design is viewed as an inventive strategy to boost the brand’s perceived value, which raises brand loyalty and increases consumers’ attention towards the brands.

H1: Green packaging is positively associated with consumer legitimacy

Mediation role of green perceived value

Green perceived value is a consumer’s overall assessment of the benefits of a product between what is received and what is given based on the consumer’s environmental desires, sustainable expectations, and green needs (Chen, Citation2013; Danish et al., Citation2019). It is a judgment that is influenced by the needs, expectations, and aspirations of consumers with regard to sustainability (Chen & Chang, Citation2012). Green perceived value has been demonstrated to positively influence consumers’ intentions to make green purchases and to contribute to the growth of their relationships with brands by raising their levels of green trust and satisfaction (Putri & Rahmiati, Citation2022; Riva et al., Citation2022; Woo & Kim, Citation2019). Green perceived value can be explained using four dimensions: emotional, social, financial, and quality (Danish et al., Citation2019; Marques & Dewi, Citation2022). Consumers gain emotional value from a brand, where utility is generated from feelings toward the brand. Financial value and quality value are more functional and connected to value for money and perceptions of a brand’s excellence. However, social value is related to the value generated by the brand’s social credibility in enhancing social self. In the context of the green packaging domain, all four dimensions enhance the consumer’s ability to describe a green brand or a brand that is socially and environmentally responsible (Charviandi, Citation2023; Danish et al., Citation2019). Lin et al. (Citation2017) pointed out that green perceived value does not only enhance the social value of the brand but also has effects on the overall corporate reputation of business firms. Growing demand for ethical practices in the marketing domain necessitates the importance of extending the research framework to investigate the influential factors of green perceived value (Danish et al., Citation2019; Lin et al., Citation2017; Putri & Rahmiati, Citation2022). This suggestion is based on the current, increasing pressure from consumers who have high expectations for business firms’ ethical commitment to society. Roh et al. (Citation2022) argue that consumers evaluate the corporate initiatives of business firms through ethical practices and detailed information related to ethical issues. Ethical commitment to society can increase green perceived value and enhance consumers’ understanding and evaluation of socially and environmentally responsible business firms (Jabeen et al., Citation2021). This study proposes that green packaging is a key driver of green perceived value.

H2: Green packaging is positively associated with green perceived value

H3: Green perceived value is positively associated with consumer legitimacy

H4: Green perceived value mediates the effect of green perceived value on consumer legitimacy

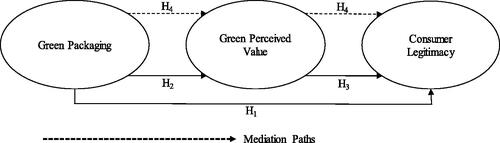

Conceptual model

The conceptual model of this study was developed with the help of the cognitive-affective-conative model. The study hypothesized a three-factor model consisting of green packaging representing the cognitive domain, green perceived value as the affective domain, and consumer legitimacy as conative domain. In addition, as presented in , the study proposed a causal-effect model while examining the interplay of the variables.

Methodology

Study setting

This study is a quantitative cross-sectional survey that involves collecting data at a specific time and place using a survey approach. Hair et al. (Citation2020) argue that quantitative-based cross-sectional design uses data to make statistical inferences about the population of interest. This approach was sought to be relevant because: 1) the aim of the study was not to trace changes that could happen after intervention or to monitor changes that could happen over time due to changes in consumers’ attitudes toward green packaging and consumer legitimacy. 2) The study collects data from a dispersed population. This study was conducted in the Dodoma region, the capital city of Tanzania. The city is among the fastest-growing cities in Tanzania in terms of population and economic activities (Gibore et al., Citation2019). Evidence indicates that the growth of the population is among the main determinative factors in increasing consumption of various fast-moving consumer goods, including cosmetics products.

Sample size and data collection

The study adopted a non-probability convenience sampling approach to select 331 customers of cosmetic products in Tanzania. This sampling technique is appropriate when respondents can be effectively accessed at specific points or business centers that deal with the sale of cosmetic products. The targeted population was customers of cosmetic products located in the Dodoma region. The determination of the sample size was based on previous studies in the cosmetic industry, which had sample sizes ranging from 300 to 400 (Jaini et al., Citation2020b; Khan et al., Citation2021; Shahid et al., Citation2023; Suparno, Citation2020; Widyanto & Sitohang, Citation2022). Additionally, the determination of the sample size is based on the conditions for using multivariate data analysis techniques such as partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), which recommends that a sample size above 250 is sufficient for achieving the robustness of findings (Hair et al., Citation2021). Thus, the sample size of 331 falls within the range used by the majority of studies in the cosmetic industry, and it is adequate for achieving the robustness of findings as recommended when using multivariate data analysis. During the data collection exercise, all important ethical issues in the research were considered to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. Data collection was done after asking respondents for their consent to participate in the study. The survey instrument contained screening question which asked respondents to indicate or mention cosmetic products which they prefer most. The screening question intend to ensure that the survey involved relevant respondents. Furthermore, the researcher assured respondents anonymity and confidentiality in all data collection, analysis, and reporting stages. In social science research, these ethical considerations are crucial to managing the problem of common method bias that often occurs in the methodological approach that collects data from respondents for exogenous and endogenous variables. Data were gathered from November 2021 to December 2021.

Measures and questionnaire development

The study used measurement scales from previous studies. The questionnaire was developed by including measurement items that captured green packaging, perceived green value, and consumer legitimacy. Measurement Items were evaluated for the closest match and suitability for the objectives of the study with the least amount of adjustment to fit the study context based on opinions and recommendations from experts in business management. Overall, in total, 15 measurement items were developed, as presented in . The first construct, green packaging, measured through 5 items, was adapted from (Maziriri, Citation2020). This construct captured the overall appearance of packaging in the context of environmental concern. For green perceived value, 5 items were adapted from (Chen, Citation2013; Roh et al., Citation2022). This construct captured the value that consumers assign to green packaging practices. For consumer legitimacy, this study utilized 5-item scales from Amani and Ismail (Citation2022) and Miotto and Youn (Citation2020) to capture ethical brand outcomes, i.e., cognitive, normative, and regulative legitimacy. The measurement items under all the constructs were responded to on a five-point Likert scale of 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree (Likert et al., Citation1934, Citation1993).

Table 1. Measurement model estimates.

Data analysis and results

Analysis of common method bias

The common method bias occurs in the situation where, to a great extent, the variance of the responses is attributable to the data collection instrument rather than to the individual position of the respondent about each question. Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) insisted that this bias often arises if the variance of the answers is methodically attributable to a single measurement method. Thus, Podasakoff et al. (2003) proposed that this bias could be dealt with through the use of ex-ante and ex-post procedures. This study used control measures or procedures to deal with bias, including pretesting the data collection instruments and informing the respondents at the beginning of the survey that the answers were anonymous and there were no right or wrong answers to each question. Furthermore, the study performs statistical procedures or controls, such as Harman’s single factor test, to test for bias. In this view, exploratory factor analysis was performed without rotation, and the results indicate that no variable accounted for more than 50% of the variance. Thus, these findings suggest that common method bias was not a significant problem in this study.

Evaluation of the measurement model

The reliability and internal consistency of the instruments used in the study were assessed using composite reliability and the Cronbach alpha coefficient. A reliability test is vital for determining the consistency and stability of instruments with respect to the concepts to be measured (Valentini et al., Citation2016). Composite reliability takes into consideration the different outer loadings of the items in the construct. The composite reliability is calculated by taking the variance due to the factor and dividing it by the total variance of the composite. Additionally, the Cronbach alpha coefficient is calculated by taking the average covariance and dividing it by the average total variance. Composite reliability and the Cronbach alpha coefficient are deemed acceptable if values are higher than 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2017). The results in indicate that the values of composite reliability for the constructs are 0.912 (green packaging), 0.950 (green perceived value), and 0.912 (consumer legitimacy), and the values of the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the constructs are 0.879 (green packaging), 0.934 (green perceived value), and 0.913 (consumer legitimacy); hence, reliability and internal consistency are good. To test convergent validity, the study conducted an examination of the average variance extracted (AVE) from the measurement items. The recommended cutoff for average variance extracted is 0.5 (Afthanorhan, Citation2013). The results in indicate that the value of average variance extracted for each variable is 0.675 (for green packaging), 0.790 (for green perceived value), and 0.678 (for consumer legitimacy). Discriminant validity was tested to establish if the measures that should not be related across latent constructs are, in fact, not. Using heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT), the cutoff point for the results is 0.85 (Ab Hamid et al., Citation2017). shows that none of the values are higher than 0.85. This means that the criteria for discriminant validity were met.

Table 2. Heterotrait-Monotrait test for discriminant validity.

Evaluation of structural model and hypotheses testing

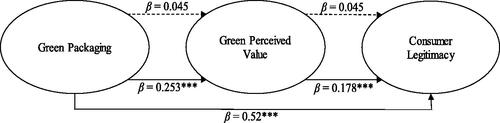

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was adopted to test the proposed model. PLS-SEM estimates a variance-based structural equation model (Hair et al., Citation2020). As a causal predictive method to SEM, PLS-SEM allows estimation of complex models with several components, indicators, and hypothesized paths without imposing distributional assumptions on the data. The coefficient of determination, R2, indicates that two exogenous constructs (green packaging and green perceived value) explain 34.9% of the variance in consumer legitimacy. In addition, model fits for PLS-SEM are Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.054 below the threshold of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), Squared Euclidean Distance (d_ULS) = 0.352 below the threshold of 0.95 (Hair et al., Citation2020), Geodesic Distance (d_G) = 0.208 below the threshold of 0.95 (Hair et al., Citation2020), Chi-square = 425.091, and Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.9 within the range of ≥ 0.9 (Bollen, Citation1989). The study computes significance path coefficients for all proposed hypotheses using t-statistic values and bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals from 5,000 subsamples. H1 of this study proposed that green packaging could boost consumer legitimacy. The findings in and support this hypothesis with (β = 0.520; t = 11.530; p < 0.001). The results as shown in and supported H2 which predicted that green packaging can enhance green perceived value (β = 0.253; t = 4.939; p < .001). In H3, the study hypothesized that, green perceived value can boost consumer legitimacy. This hypothesis was supported with (β = 0.178; t = 3.766; p < .001) as presented in and .

Table 3. Structural model results and summary of hypothesis testing.

Mediating relationship

The study tested H4 using bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals from 5,000 subsamples. H4 predicts that green perceived value mediates the effect of green perceived value on consumer legitimacy. The results in indicate that the relationship between green packaging and green perceived value is positive and significant (β = 0.342; LLCI = 1.155 and ULLCI = 2.325). The relationship between green packaging and consumer legitimacy is positive and significant (β = 0.530; LLCI = 0.435 and ULLCI = 0.625). The relationship between green perceived value and consumer legitimacy is positive and significant (β = 0.138; LLCI = 0.068 and ULLCI = 0.207). The relationship between green packaging, green perceived value, and consumer legitimacy is significant (β = 0.045; LLCI = 0.019 and ULLCI = 0.075). Based on the results, zero was not included in the bootstrap interval, hence green perceived value mediates the relationship between green packaging and consumer legitimacy.

Discussion of findings

The findings of the study contribute to the current agenda, aiming to connect various business practices, including green packaging, to the realization of sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly in the context of sustainable production and consumption patterns. The study suggests that green packaging is positively associated with consumer legitimacy when mediated by green perceived value. These findings illuminate the significance of green packaging in safeguarding products and reducing waste within competitive business environments (Ismail, Citation2022; Prakash & Pathak, Citation2017; Shukla et al., Citation2022). In alignment with and support of SDG number 12, which centers on sustainable consumption and production patterns, the findings emphasize the need for industries, businesses, and consumers to embrace green packaging (Amoako et al., Citation2022; Prakash & Pathak, Citation2017). The study implies that business firms in the cosmetics industry should adapt their business models and adopt sustainable packaging solutions to align with the SDGs, thereby contributing to a circular economy and a cleaner planet (Ismail et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, the findings suggest that this study stands as one of the few endeavors that underscore the importance of brand ethical behavior in building consumer legitimacy. It also implies the importance of developing and adopting a business model that enables the cosmetics industry, as well as fast-moving consumer goods, to implement business or manufacturing processes that protect public goods (Ismail, 2023; Miotto & Youn, Citation2020).

The findings specifically indicate that green packaging, defined by environmentally friendly packaging appearance, recyclable packaging material, and labeling that includes environmentally friendly information, is crucial in determining green perceived value. In this study, “green perceived value” is defined as customers’ expectations that the packaging materials communicate environmental benefits, encompassing both emotional and functional aspects (Danish et al., Citation2019; Juliana et al., Citation2020; Woo & Kim, Citation2019). The findings suggest that green packaging influences green perceived value, reflecting customers’ sentiments that the product packaging is socially acceptable and accountable. Evidence suggests that the cosmetics industry extensively employs packaging materials with numerous negative effects (Ismail et al., Citation2023). The study findings indicate that addressing this environmental concern is possible through the adoption of novel packaging solutions to minimize negative social and environmental impacts (Maziriri, Citation2020). Additionally, the study findings propose a mediating role for green perceived value in the association between green packaging and consumer legitimacy. Consumer legitimacy is portrayed as the outcome of brand ethical behavior, representing brands that adhere to regulatory, normative, and cognitive institutions (Chen & Lee, Citation2022). Therefore, in relation to these findings, green packaging becomes an integral part of sustainable production and consumption patterns, aiming to minimize unnecessary packaging and design for sustainable end-of-life disposal options (Juliana et al., Citation2020). It should entail packaging designs that enhance green perceived value through the use of broadly recyclable materials, including higher recycled content, and by promoting packaging reuse or repurposing.

Theoretical contribution

This study makes a significant theoretical contribution to the literature on green packaging by pioneering the conceptualization of antecedents to consumer legitimacy within the realm of green marketing practices, specifically focusing on green packaging. The research enhances theoretical understanding of the interplay between green packaging and consumer legitimacy through the mediation of green perceived value. Utilizing the cognitive-affective-conative model, the study extends existing knowledge regarding the role of green packaging in shaping consumer legitimacy. Consequently, this research not only contributes to the refinement of the cognitive-affective-conative model but also enriches the literature on green marketing practices. Furthermore, the study progresses the conceptual definitions of key terms, namely “green packaging,” “perceived green value,” and “consumer legitimacy,” by emphasizing these as integral components of the cognitive, affective, and conative states of mind. The findings endorse a taxonomy that advocates considering cognitive, affective, and conative aspects of the human mind when elucidating the concept of green marketing practices, encompassing green consumption. In the context of this model, the research advances our understanding of the idea that individuals undergo distinct stages of attitudinal and cognitive states before engaging in various actions related to green marketing practices.

Managerial recommendations

The study’s findings underscore practical recommendations for managers and practitioners, highlighting the pivotal role of green packaging in enhancing brand legitimacy. In light of the pervasive environmental challenges within the cosmetic industry, it is imperative for various stakeholders, especially marketers, to address these concerns. This study introduces a unique perspective on the significance of green packaging, examining it from both consumers’ and producers’ viewpoints. For marketers, integrating brand ethical behaviors, specifically incorporating green packaging into the brand-building process, is essential. Managers, particularly in marketing roles, should consider investing in packaging materials that feature recycled content and promote packaging reuse or repurposing. The study reveals a growing societal and consumer-driven pressure for marketers and managers to adapt to green packaging initiatives. In the fiercely competitive global market, cosmetic industry marketers must adopt innovative strategies to gain a competitive edge. Green packaging practices emerge as a novel and effective tool to not only secure a competitive advantage but also to foster a business’s environmental responsibility and overall performance. Importantly, companies strategically allocating resources to green packaging can achieve cost savings in delivery, materials, and waste reduction, ultimately translating into enhanced profitability. In essence, embracing green packaging offers a pathway to not only environmental responsibility but also financial success, providing a winning formula for businesses in the cosmetics industry.

The study highlights crucial managerial implications, stressing the imperative for managers to invest in empowerment and training initiatives for both consumers and employees. Drawing on the insights from the 2022 Global Buying Green Report, which reveals that 67% of consumers consider themselves environmentally aware, the study underscores the need for managers to prioritize training, enhancing their capacity for making environmentally friendly purchasing decisions (Buying Green Report, Citation2021). In the cosmetics and fast-moving consumer goods industries, managers are urged to allocate resources towards training and empowerment initiatives for their supply chain members. These initiatives should strategically focus on key areas, including the importance of green packaging and the marketing of eco-friendly products. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the significance of managerial investment in strategic marketing communication programs, particularly green advertising, to effectively convey the environmental responsibility and accountability of their products. This is essential for managers, as the Buying Green Report (Citation2021) indicates that over 83% of customers are prepared to pay a premium for sustainable or green packaging. This emphasis provides an opportunity for producers in the cosmetics industry to gain a competitive edge among a substantial consumer base that prioritizes environmental concerns. Additionally, considering the recyclable nature of the majority of green packaging materials, managers in the cosmetics industry should leverage green advertising to educate customers on proper recycling, reuse, and disposal practices. This not only aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but also ensures active participation from the cosmetics industry in fostering sustainable production and consumption patterns.

Limitations and areas for further studies

The current study has a few limitations that offer avenues for further studies. This study was conducted in the cosmetics industry in Tanzania. To ensure the robustness of the findings regarding the subject matter, a new avenue exists for further studies to be conducted in other countries to obtain cross-cutting findings. Also, the study has been conducted in a single industry context, focusing on the cosmetics industry. It is suggested that the proposed theoretical model can be tested in other industries, particularly those that offer fast-moving consumer goods and across mid-scale and up-scale producers. It is revealed by the global buying green report of 2022 that there are differences between age groups in their willingness to pay more for environmentally friendly products (Buying Green Report, Citation2021). This may be important for undertaking comparative studies that compare various age groups regarding their responses to green packaging in relation to consumer legitimacy or other brand ethical behavior. It is also important to have comparative studies in terms of gender differences, which can offer more insights on how to manage green packaging across female and male consumers. Moreover, it is important for further studies to modify the model by introducing other mediators such as perceived brand ethicality and consumerism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Amani

David Amani (PhD) is a research scholar in marketing who earned his PhD in Business Administration from Mzumbe University in Tanzania. Currently, he works as a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Business Administration and Management at the University of Dodoma in Tanzania. His research interests include brand management, sports marketing, corporate social responsibility, and entrepreneurial marketing. He has published several papers in various reputable journals such as Service Marketing Quarterly, Social Responsibility Journal, International Hospitality Review, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, and Future Business Journal.

References

- Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Mohmad Sidek, M. H. (2017). Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890, 1. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/890/1/012163

- Abidin, S. Z., Effendi, R. A. A. R. A., Ibrahim, R., & Idris, M. Z. (2014). A semantic approach in perception for packaging in the SME’s food industries in malaysia: A case study of malaysia food product branding in United Kingdom. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 115, 115–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.420

- Afthanorhan, W. (2013). A comparison of partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and covariance based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) for confirmatory factor analysis. International Journal of Engineering Science and Innovative Technology, 2(5), 198–205.

- Alwi, S. F. S., Ali, S. M., & Nguyen, B. (2017). The importance of ethics in branding: Mediating effects of ethical branding on company reputation and brand loyalty. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(3), 393–422. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.20

- Amani, D. (2022). Internal corporate social responsibility and university brand legitimacy: an employee perspective in the higher education sector in Tanzania. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(4), 611–625.

- Amani, D., & Ismail, I. J. (2022). Investigating the predicting role of COVID-19 preventive measures on building brand legitimacy in the hospitality industry in Tanzania: mediation effect of perceived brand ethicality. Future Business Journal, 8, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-022-00128-6

- Amoako, G. K., Dzogbenuku, R. K., Doe, J., & Adjaison, G. K. (2022). Green marketing and the SDGs: Emerging market perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 40(3), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-11-2018-0543

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). A New Incremental Fit Index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

- Borah, P. S., Dogbe, C. S. K., Pomegbe, W. W. K., Bamfo, B. A., & Hornuvo, L. K. (2021). Green market orientation, green innovation capability, green knowledge acquisition and green brand positioning as determinants of new product success. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(2), 364–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2020-0345

- Boz, Z., Korhonen, V., & Koelsch Sand, C. (2020). Consumer considerations for the implementation of sustainable packaging: A review. Sustainability, 12(6), 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062192

- BUYING GREEN REPORT. (2021). Sustainable packaging in a year of unparalleled disruption.

- Chao, E., & Uhagile, G. T. (2022). Consumer perceptions and intentions toward Buying Green Food products: A case of Tanzania. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 34(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2020.1845904

- Charviandi, A. (2023). Application of shopping bag to consumer green purchase behavior through green trust, and green perceived value. RIGGS: Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Business, 1(2), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.31004/riggs.v1i2.22

- Chen, S., Wright, M. J., Gao, H., Liu, H., & Mather, D. (2021). The effects of brand origin and country-of-manufacture on consumers’ institutional perceptions and purchase decision-making. International Marketing Review, 38(2), 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-08-2019-0205

- Chen, X., & Lee, G. (2021). How does brand legitimacy shapes brand authenticity and tourism destination loyalty: Focus on cultural heritage tourism. Global Business Finance Review, 26(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.17549/gbfr.2021.26.1.53

- Chen, X., & Lee, T. J. (2022). Potential effects of green brand legitimacy and the biospheric value of eco-friendly behavior on online food delivery: A mediation approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11), 4080–4102. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2021-0892

- Chen, Y. (2013). Towards green loyalty: driving from green perceived value, green satisfaction, and green trust. Sustainable Development, 21(5), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.500

- Chen, Y., & Chang, C. (2012). Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Management Decision, 50(3), 502–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211216250

- Chun, R. (2016). What holds ethical consumers to a cosmetics brand: The Body Shop case. Business & Society, 55(4), 528–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650313520201

- Danish, M., Ali, S., Ahmad, M. A., & Zahid, H. (2019). The influencing factors on choice behavior regarding green electronic products: Based on the green perceived value model. Economies, 7(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7040099

- Deloitte. (2018). Sustainable development goals: A business perspective. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/nl/Documents/risk/deloitte-nl-risk-sdgs-from-a-business-perspective.pdf

- Gekonge, D. O., George, A., Geoffrey, E. O., & Villacampa, M. (2021). Consumer awareness, practices and purchasing behavior towards green consumerism in Kenya. East African Journal of Science, Technology and Innovation, 2. https://doi.org/10.37425/eajsti.v2i.334

- Gibore, N. S., Ezekiel, M. J., Meremo, A., Munyogwa, M. J., & Kibusi, S. M. (2019). Determinants of men’s involvement in maternity care in Dodoma Region, Central Tanzania. Journal of Pregnancy, 2019, 7637124. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7637124

- Gomez-Trujillo, A. M., Velez-Ocampo, J., Castrillon-Orrego, S. A., Alvarez-Vanegas, A., & Manotas, E. C, CEIPA Business Center. (2021). Responsible patterns of production and consumption: The race for the achievement of SDGs in emerging markets. AD-Minister, 38(38), 93–120. https://doi.org/10.17230/Ad-minister.38.4

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S., Jr. (2021). An introduction to structural equation modeling. In J. F. Hair G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, N. P. Danks, & S. Ray (Eds.), Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (pp. 1–29). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1

- Hair, J. F., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2020). Essentials of business research methods (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(2020), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hakala, H., Niemi, L., & Kohtamäki, M. (2017). Online brand community practices and the construction of brand legitimacy. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117705695

- Han, J., Ruiz‐Garcia, L., Qian, J., & Yang, X. (2018). Food packaging: A comprehensive review and future trends. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17(4), 860–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12343

- Herbes, C., Beuthner, C., & Ramme, I. (2020). How green is your packaging—A comparative international study of cues consumers use to recognize environmentally friendly packaging. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(3), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12560

- Hilgard, E. R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696(198004)16:2<107::AID-JHBS2300160202>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hu, M., Qiu, P., Wan, F., & Stillman, T. (2018). Love or hate, depends on who’s saying it: How legitimacy of brand rejection alters brand preferences. Journal of Business Research, 90(2018), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.006

- Ikram, A., Fiaz, M., Mahmood, A., Ahmad, A., & Ashfaq, R. (2021). Internal corporate responsibility as a legitimacy strategy for branding and employee retention: A perspective of higher education institutions. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010052

- Ismail, I. J. (2022). The role of technological absorption capacity, enviropreneurial orientation, and green marketing in enhancing business’ sustainability: evidence from fast-moving consumer goods in Tanzania. Technological Sustainability, 2(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/TECHS-04-2022-0018

- Ismail, I. J., Amani, D., & Changalima, I. A. (2023). Strategic green marketing orientation and environmental sustainability in sub-Saharan Africa: Does green absorptive capacity moderate? Evidence from Tanzania. Heliyon, 9(7), e18373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18373

- Jabeen, G., Ahmad, M., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Factors influencing consumers’ willingness to buy green energy technologies in a green perceived value framework. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy, 16(7), 669–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567249.2021.1952494

- Jaini, A., Quoquab, F., Mohammad, J., & Hussin, N. (2020a). Antecedents of green purchase behavior of cosmetics products: An empirical investigation among Malaysian consumers. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 36(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-11-2018-0170

- Jaini, A., Quoquab, F., Mohammad, J., & Hussin, N. (2020b). “I buy green products, do you…?” The moderating effect of eWOM on green purchase behavior in Malaysian cosmetics industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 14(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPHM-02-2019-0017

- Juliana, J., Djakasaputra, A., & Pramono, R. (2020). Green perceived risk, green viral communication, green perceived value against green purchase intention through green satisfaction. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research, 1(2), 124–139.

- Ketelsen, M., Janssen, M., & Hamm, U. (2020). Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging-A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 254, 120123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120123

- Khan, N., Sarwar, A., & Tan, B. C. (2021). Determinants of purchase intention of halal cosmetic products among Generation Y consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(8), 1461–1476. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-11-2019-0248

- Lialiuk, A., Kolosok, A., Skoruk, O., Hromko, L., & Hrytsiuk, N. (2019). Consumer packaging as a tool for social and ethical marketing. Innovative Marketing, 15(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.15(1).2019.07

- Likert, R., Roslow, S., & Murphy, G. (1934). A simple and reliable method of scoring the Thurstone Attitude Scales. The Journal of Social Psychology, 5(2), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1934.9919450

- Likert, R., Roslow, S., & Murphy, G. (1993). A simple and reliable method of scoring the Thurstone Attitude Scales. Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 689–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00893.x

- Lin, J., Lobo, A., & Leckie, C. (2017). The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.12.011

- Lydekaityte, J., & Tambo, T. (2020). Smart packaging: Definitions, models and packaging as an intermediator between digital and physical product management. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 30(4), 377–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2020.1724555

- Machová, R., Ambrus, R., Zsigmond, T., & Bakó, F. (2022). The impact of green marketing on consumer behavior in the market of palm oil products. Sustainability, 14(3), 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031364

- Magnier, L., & Schoormans, J. (2015). Consumer reactions to sustainable packaging: The interplay of visual appearance, verbal claim and environmental concern. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.09.005

- Marques, E. A. D., & Dewi, N. M. W. K. (2022). Peran Green Trust Memediasi Green perceived value Dan Kepuasan Konsumen Terhadap Green repurchase intention. Jurnal Sosial Dan Teknologi, 2(11), 1019–1036.

- Martín-de Castro, G. (2021). Exploring the market side of corporate environmentalism: Reputation, legitimacy and stakeholders’ engagement. In Industrial Marketing Management, 92, 289–294. (Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.010

- Maziriri, E. T. (2020). Green packaging and green advertising as precursors of competitive advantage and business performance among manufacturing small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1719586. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1719586

- Miotto, G., & Youn, S. (2020). The impact of fast fashion retailers’ sustainable collections on corporate legitimacy: Examining the mediating role of altruistic attributions. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(6), 618–631. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1852

- Molina‐Besch, K., & Pålsson, H. (2016). A supply chain perspective on green packaging development‐theory versus practice. Packaging Technology and Science, 29(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/pts.2186

- Mueller, S., & Szolnoki, G. (2010). The relative influence of packaging, labelling, branding and sensory attributes on liking and purchase intent: Consumers differ in their responsiveness. Food Quality and Preference, 21(7), 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.07.011

- Orquin, J. L., Bagger, M. P., Lahm, E. S., Grunert, K. G., & Scholderer, J. (2020). The visual ecology of product packaging and its effects on consumer attention. Journal of Business Research, 111, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.043

- Orzan, G., Cruceru, A. F., Bălăceanu, C. T., & Chivu, R.-G. (2018). Consumers’ behavior concerning sustainable packaging: An exploratory study on Romanian consumers. Sustainability, 10(6), 1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061787

- Papaluca, O., Sciarelli, M., & Tani, M. (2020). Ethical branding in the modern retail: A comparison of Italy and UK Ethical coffee branding strategies. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v12n1p1

- Payne, G., Blanco-González, A., Miotto, G., & Del-Castillo, C. (2021). Consumer ethicality perception and legitimacy: Competitive advantages in COVID-19 crisis. American Behavioral Scientist, 000276422110165. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211016515

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prakash, G., & Pathak, P. (2017). Intention to buy eco-friendly packaged products among young consumers of India: A study on developing nation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 141, 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.116

- Putri, P. H., & Rahmiati, R. (2022). The influence of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust on green repurchase intention on clodi (clothing diapers) Ningrat. Marketing Management Studies, 2(1), 85–95.

- Quoquab, F., & Mohammad, J. (2020). Cognitive, affective and conative domains of sustainable consumption: Scale development and validation using confirmatory composite analysis. Sustainability, 12(18), 7784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187784

- Randrianasolo, A. A., & Arnold, M. J. (2020). Consumer legitimacy: conceptualization and measurement scales. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37/(4)2020), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-03-2019-3124

- Riva, F., Magrizos, S., Rubel, M. R. B., & Rizomyliotis, I. (2022). Green consumerism, green perceived value, and restaurant revisit intention: Millennials’ sustainable consumption with moderating effect of green perceived quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 2807–2819. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3048

- Roh, T., Seok, J., & Kim, Y. (2022). Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 67, 102988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102988

- Sambu, F. K. (2016). Effect of green packaging on business performance in the manufacturing in Nairobi County, Kenya. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 4(2), 741–753.

- Shabbir, M. S., Bait Ali Sulaiman, M. A., Hasan Al-Kumaim, N., Mahmood, A., & Abbas, M. (2020). Green marketing approaches and their impact on consumer behavior towards the environment—A study from the UAE. Sustainability, 12(21), 8977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218977

- Shahid, S., Parray, M. A., Thomas, G., Farooqi, R., & Islam, J. U. (2023). Determinants of Muslim consumers’ halal cosmetics repurchase intention: an emerging market’s perspective. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14(3), 826–850. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-08-2021-0265

- Shukla, M., Misra, R., & Singh, D. (2022). Exploring relationship among semiotic product packaging, brand experience dimensions, brand trust and purchase intentions in an Asian emerging market. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-10-2021-0718

- Suparno, C. (2020). Online purchase intention of halal cosmetics: SOR framework application. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(9), 1665–1681. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-09-2019-0192

- Suphasomboon, T., & Vassanadumrongdee, S. (2022). Toward sustainable consumption of green cosmetics and personal care products: The role of perceived value and ethical concern. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 33, 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.07.004

- Underwood, R. L., & Klein, N. M. (2002). Packaging as brand communication: effects of product pictures on consumer responses to the package and brand. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 10(4), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2002.11501926

- Valentini, F., Damásio, B. F., Valentini, F., & Damásio, B. F. (2016). Average variance extracted and composite reliability: Reliability coefficients. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(2), 53. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-3772e322225

- Wandosell, G., Parra-Meroño, M. C., Alcayde, A., & Baños, R. (2021). Green packaging from consumer and business perspectives. Sustainability, 13(3), 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031356

- Widyanto, H. A., & Sitohang, I. A. T. (2022). Muslim millennial’s purchase intention of halal-certified cosmetics and pharmaceutical products: the mediating effect of attitude. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 13(6), 1373–1394.

- Woo, E., & Kim, Y. G. (2019). Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: From the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). British Food Journal, 121(2), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2018-0027

- Yang, K., Kim, J., Min, J., & Hernandez-Calderon, A. (2021). Effects of retailers’ service quality and legitimacy on behavioral intention: The role of emotions during COVID-19. The Service Industries Journal, 41(1-2), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1863373

- Zsigmond, T., Machová, R., & Korcsmáros, E. (2021). The ethics and factors influencing employees working in the Slovak SME sector. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 18(11), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.12700/APH.18.11.2021.11.10