?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Nigeria has one of the largest out-of-school populations in the world and the largest in Africa. This study analyses the determinants of socioeconomic issue of out-of-school children. This issue is a key component of the UNSDG4. Multinomial logistic regression was used to analyse child schooling enrolment. 1120 questionnaires were administered to household heads across Kwara State, Nigeria. This study highlights the importance of access and cost in improving child schooling and how parents with low educational attainment tend to pay less attention to their child’s schooling. The study recommends the increased provision of schools within or near rural communities, tuition-free education, and sensitizing parents with low levels of education on the importance of education in their child’s development.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Children’s Education Fund (UNICEF), one in every five out-of-school children is a Nigerian. 10.5 million Children aged 5–14 years are not in school. Only 61% of children of 6–11 years old attend schools; only 35.6% of children aged 35–59 months are privileged with early childhood education (Naciones Unidas, Citation2015; UNESCO, Citation2022; UNESCO & UIS, 2014; UNICEF, Citation2018a). In the North-East and North-West regions of Nigeria, 29 and 35% of Muslim children receive only Quranic education, which does not involve necessary skills like numeracy and literacy. This situation is worse with the girl child, which even makes the situation more alarming (The United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2022; UNICEF, Citation2018b). The percentage of child schooling in Nigeria has not been impressive as Nigeria tops the list of countries with the highest number of out-of-school children in the world (UNESCO, 2018). It is however paramount to determine the factors that influence child schooling/out of school. This is a major socio-economic issue which does not only falls under the United Nations Development Goal 4 (UNSDG4), but it is also a foundation for human capital development. The term Out-Of-School Children can be defined as the number of children between the ages of 3–17 years who do not access education or who drop out along the way without finishing their primary or secondary education (Care & Ecce, Citation2007; UNESCO, Citation2008, Citation2022; UNESCO and UIS, Citation2014; Vayachuta et al., Citation2016). Child schooling is therefore the enrolment of children between the ages of 3 and 17 years.

There is consensus in the international community that Universal Primary Schooling is essential to human development (Lloyd et al., Citation2016). The benefits of child schooling are limitless, including the enhancement of individual capability to be healthy, earn a living, control fertility, have a voice, and, most importantly, have economic, geographic, and social mobility. Child schooling benefits parents through higher income for the family, welfare, economic support to parents in old age, improved social status and higher quality of life. While attaining this goal is more significant in Sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria further witnessed a reversal in enrolment (Lloyd et al., Citation2016). There are so many out-of-school children, as Kwara State has the second-highest rate of out-of-school children in the North Central region, and many can be seen hawking during school hours.

About 250 million children are not getting basic numeracy and literacy worldwide (UNICEF, Citation2017). There is a need for vast improvement, without which around 1.5 billion adults would still be with only primary school education by 2030 globally. Most are bound to be from parents with little education, and their children will consequently be highly at risk of propagating the cycle. It is paramount to raise not only the quality of schools but also improve access to formal secondary education, most notably in rural areas. This will ensure that graduates have the requirement to succeed (UNICEF, Citation2017).

Children from deprived backgrounds receive an inferior education; they get inadequate public financing for education and end up with the lowest level of achievement as youths in the long run (UNICEF, Citation2017). The main challenge is the expanding size and population in Africa and Asia. According to the United Nations, only one in three girl children is in a secondary school in Africa (UNESCO, 2015). Close to half of the regional population is under 18 years of age. Out of the 63 million children out of primary school, more than 50% are in Sub-Saharan Africa (Scott et al., Citation2014). This implies that, in Sub-Saharan Africa, over 30 million children do not attend school, of which 54% are girls (Scott et al., Citation2014).

It is key to note that one major cause of the high rate of out-of-school children is unemployment and poverty (Rueckert, Citation2019). This is a major concern of the United Nations, and it has been listed under the sustainable development goals to ensure that all the children in any nation can access quality early childhood development, care, and pre-primary education in readiness for primary education. By 2030, the United Nations wants to ensure that children complete equitable primary and secondary education freely with high quality. The budgetary spending on education in Nigeria is not reflective of the situation on the ground as only 7% of the budget of 2018 was dedicated to education with no new policy in place to salvage the situation (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2018; UN/UNICEF, 2018). The budgetary allocation has, however, continued to fall, as only 6% was allocated for 2020.

With the acknowledgement that education is a viable tool for developing human capital, Nigeria’s level of child schooling has remained low. Nigeria’s educational sector is known for its poor infrastructure (Babatunde et al., Citation2019). Additionally, Nigeria ranked 118th in educational attainment with a female-to-male ratio of 0.85 for enrolment into primary school, secondary school enrolment at 0.86, and 0.55 for post-secondary school. With the commitment of the Nigerian government to Universal Basic Education, especially at the primary level and the effort to expand access to schooling, many school-age children remain out of school (Babatunde et al., Citation2019). A significant challenge is that the majority are female. Education is paramount for the human capital and economic development of any state (Babatunde et al., Citation2019).

Nigeria is one of the countries with the most severe case of crises in terms of education that UNICEF prioritised in terms of education emergencies (Scott et al., Citation2014). Nigeria has, however, not shown a positive attitude toward education, going by the budgetary allocation for education over the years (World Bank Group, Citation2015).

Free primary education, as widely claimed, is not real in Nigeria, even with national policies on fees and tuition. Nigeria needs serious research at the micro-level, especially when school costs come to play. According to Lincove (Citation2009), only 15% of children benefit from free primary education, and 33% are out-of-school. The children from wealthy homes represent a large portion of those benefiting as against the poor households. Schooling cost and enrolment have been continuously influenced by family characteristics, which include religion and wealth (Lincove, Citation2009).

In Kwara State, past Government administrations did not meet the required conditions to access funding/grants from the Universal Basic Education Board to develop the schools even with the dilapidated state of schools. The more worrisome part is that the government mismanaged and could not account for the previous funds they accessed (Bobboyi, Citation2019).

2. Setting

2.1. Geographic and demographic information on Nigeria and Kwara State

Nigeria is a West African country. It is the largest and most populous in Africa, with more than 193 million people (National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Citation2010; National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018; Verma, Citation2015). There are 36 states in Nigeria asides from the federal capital territory. The country is divided into six geo-political zones and Nigeria’s age distribution comprises about 80.9 million children (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018).

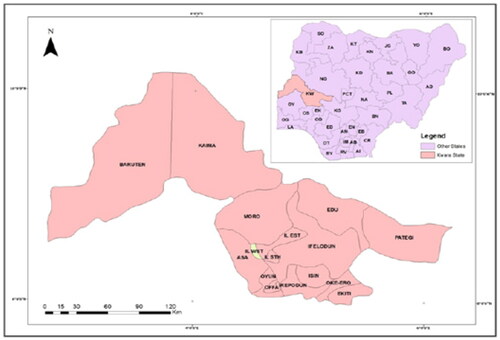

Kwara State has a landmass of 35,705 km2 with a population of about 3.1 million people (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018; Verma, Citation2015). Kwara State is in the North-central geo-political zone, commonly referred to as Middle-belt.

Kwara State is blessed with many ethnic groups. The Yorubas are the majority, mainly found in parts of Kwara central and Kwara south. In the Northern part of the state, they have the Nupes and the Barutens as the majority. The Ibolos represent a major ethnic group in the Southern part, and the Fulanis also have a strong base in Kwara central, particularly in the capital city of Ilorin. There are other minority groups aside from these major ones numbering more than 50 ().

Figure 1. Map of Kwara State indicating its location in pink colour on the map of Nigeria.

Source: Adapted from Kwara State Government Portal https://kwarastate.gov.ng/#.

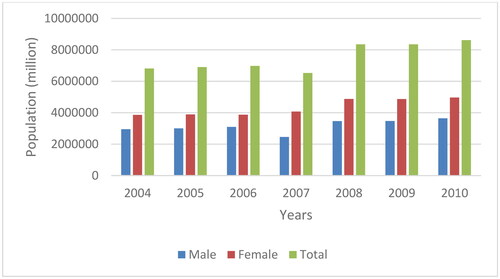

There is an increasing rate of out-of-school children in Nigeria. According to World Bank Development Index, the population of out-of-school children in Nigeria was 8,615,770 as of 2010. The 2014 UNESCO Education Report shows that 30% of children were out-of-school as of 2011, and the figure increased to 31% in 2013. As shown in , the total number of out-of-school children in Nigeria was 6,816,675 million as of 2004, and this figure gradually rose to 8,615,770 by 2010. The percentage of children that never attended school rose from 21% in 2011 to 28% in 2013, as shown in . The percentage of over-age children in primary school rose marginally from 18 to 19% between 2011 and 2013. The percentage of out-of-school children rose from 30% of the total population to 31% from 2011 to 2013, respectively, while the primary school completion rate reduced to 69% from 78%. Out-of-school adolescents increased from 22 to 28%, and higher education attendance reduced from 12 to 8%.

Table 1. Out-of-school children in Nigeria (primary).

Table 2. Enrolment Statistics in percentage for Nigeria and Kwara State.

shows that the percentage of children out of school was 32.08% back in 2004, and this increased to 34.02% in 2010. Gender-wise, female out-of-school children rose from 37.01 to 41.76% in 2008, while the percentage of males rose from 27.31 to 28.26%. The graphical representation is clearly shown in .

The Population of out-of-school children is not only high in Kwara State, but the state has the second highest percentage of out-of-school children in the North central region of Nigeria, with 23.1% as at 2008 (see ).

Table 3. Out of school children in North Central Geopolitical Region of Nigeria.

3. Literature review

The theories applicable to child schooling which underpins the study will be concisely reviewed. Furthermore, the section reviews the empirical works of literature on child schooling.

3.1. Concept of child schooling

Access to universal basic education has been one of the primary goals of the international education community. The international community believes the accessibility of education through removing hindrances like school fees and the proclaiming of free schooling and other related policies would result in children gaining access to school (UNICEF, Citation2018b).

The UNSDG have dedicated many resources to ensure that there is an improvement in the education of children, and there have been significant improvements in the school enrolment level in all regions of the third world nations in the past few decades. Most children do not only complete primary education, but the majority further to some level of secondary school in these regions (Glewwe & Muralidharan, Citation2016). Nevertheless, despite all these improvements, Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) is still not doing well against other regions. Most out-of-school children live in SSA (Vinet & Zhedanov, Citation2011). Although several countries now have access to free education at the primary level, several expenses go beyond equally obligatory fees, such as uniforms. Such additional expenses make it unaffordable for some families. Whereas, in cases where primary school is completed, furthering to the secondary level tends to be unaffordable for some households that can be classified as poor (Baird et al., Citation2014).

The school fees abolition Initiative (SFAI), which was conceived with the assumption that the removal of fees would benefit every child, led to the grouping of children into different categories. These categories are poor households, orphans, ethnic minorities, conflict communities, wars, and natural disasters—such measures as removing fees are insufficient for such groups. Many children that fall into such groups gain and can gain access to education, but it is a more complex task to ensure they attend schools (UNICEF, Citation2018b).

A substantial level of investment is needed to fulfil the dream of achieving Universal Basic Education for the next generation of disadvantaged and poor children up to secondary level and to ensure that more have access to higher education. Hence, this puts them on a new promising path that will lead them to break the existing vicious cycle of poverty in which they live (UNICEF, 2018).

The introduction of the 2015 SDGs has made the goal of completing primary and secondary education for all stronger. Though schooling for all may be achieved with high investments in interventions, the goal cannot be accomplished unless household demand for education is ensured (Bruns et al., Citation2015). This demand by the household will be challenging to achieve in SSA if the difficulties faced by parents in educating their children in the form of direct and indirect cost is not reduced (Glewwe & Kassouf, Citation2010).

The number of out-of-school children globally fell by about half in the last decade. The figure was 102 million in 2000 and fell to 57 million in 2011 (UNICEF, Citation2013). Nevertheless, the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of attaining Universal Primary Education (UPE) by 2015, which transformed into SDG with 2030 as target, has been facing setbacks over the years as primary school enrolment has plateaued.

There are several types of intervention that exist. Such intervention includes the removal of school fees, the introduction of funding/scholarships, programmes organised to improve maternal literacy, and transport subsidy to schools, even though supply-side interventions are more common than demand-side (Glewwe & Muralidharan, Citation2016). These interventions that lower the cost incurred by a household on schooling or boost the expected returns have contributed to increased enrolments. The cash transfer initiative aimed at reducing poverty for low-income families has also served as a form of demand-side intervention as they contribute to the rate of child schooling and boosts human capital (Glewwe & Muralidharan, Citation2016).

3.2. Theories of child schooling

Many theories explain why children are out of school, the determinants of school enrolment, and education attainment. The theories surveyed are the theories relevant to the study.

3.2.1. Rational action theory

The rational action theory suggests that families make rational decisions when choosing their child’s education. They carefully weigh the benefits and costs associated with each option and assess the likelihood of achieving a successful outcome. Factors such as class and gender disparities in educational patterns are influenced by the resources and constraints faced by the family. Breen and Goldthorpe (Citation1997) and Goldthorpe (Citation1996) indicate that gender differences in educational attainment have been gradually eliminated, with female children catching up to male children more rapidly across different social classes. The theory also explains class disparities in educational achievements through the primary and secondary effects described by Smith and Boudon (Citation1974).

This theory assumes that parents and their children engage in a rational educational decision-making process. They consider the potential benefits and drawbacks of various alternatives, such as staying in school and pursuing academic or vocational courses or dropping out altogether. This decision-making process reflects a cost-benefit analysis and the evaluation of different outcomes, including success or failure in education. The four major components of the rational action theory are further explained.

3.2.1.1. Model of educational decisions

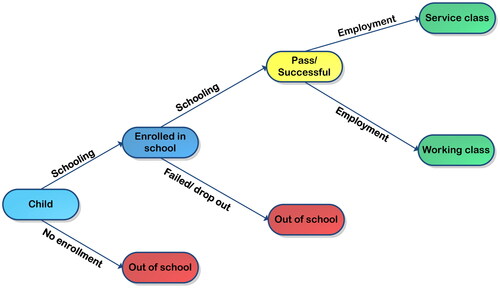

The rational action theory can be applied to the decision-making process of parents and children regarding their schooling choices. It assumes that children have to decide whether to continue their education, with two potential outcomes of continuing to pass or fail the examination and leaving school being the third outcome. When making this decision, parents and children consider factors such as the cost of schooling, the likelihood of success with further education, and the importance they place on schooling outcomes. These factors play a role in rationalising the potential benefits and costs associated with staying in or leaving school (Breen & Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Goldthorpe, Citation1996). is an illustration of the theory.

3.2.1.2. Relative risk aversion

The relative risk aversion assumes that the parents in different classes seek to ensure that their child goes to school and acquire education to a level that will ensure that he or she can attain a class position that is at least higher or the same as the one they come from. Every household seeks to guide against downward social mobility, assuming that we have two classes: the service class and the working class. The strategy that the parents will adopt is to ensure that their child acquires education that will ensure that he or she can get to such class with the qualification (Breen & Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Goldthorpe, Citation1996).

3.2.1.3. Differences in ability and expectations of success

While it is often assumed that the choice of schooling is open to all children, this is usually not applicable as they move to higher levels of education, as the progression to a higher level usually depends on a certain criterion the candidate must meet. Using a typical example, a child can only proceed to secondary school in Nigeria after passing the mandatory common entrance examination to secondary school. From previous assumptions, the expectation is that children from parents in the service class meet this condition more than the proportions of those in the working class (Breen & Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Goldthorpe, Citation1996).

3.2.1.4. Differences in resources

With this assumption, there is a need to look at the class differences in the resources that different households in different levels of class structure can spend on their child’s schooling. Assuming children can continue to a higher level of education only when Ri > C, where Ri is the resources disposable for a child’s schooling in the family i. assuming that the service class household has more resources than that of the working class, Rs > Rw where s is service class, and w is working class, and the resources are dispersed similarly within each class. Therefore, more service-class children will have the minimum resources required than children from working-class households (Breen & Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Goldthorpe, Citation1996).

3.2.2. Human capital investment theory

Becker (Citation1964) and Becker and Tomes (Citation1986) developed a theoretical framework that can be used to predict the impact of income shocks on human capital investment. The households can separate investment decisions and study consumption, and the choice and decision to invest will be determined by the expected rate of return (Dhanaraj, Citation2016; Jacoby & Skoufias, Citation1997). In such cases, the investment in human capital in a child is not dependent on the parents’ assets, consumption of parents or incomes, as parents can decide to borrow by calculating a child’s future earnings as a means to pay back, thereby investing optimally. On the other hand, when there are no perfect financial markets, the assumption of separability of the decision to invest and consume does not stand, and the family resources will determine the level of expenditure on the education of a child or children. Usually, the consumption smoothing mechanism at any time has limitations for households in countries with low-income and middle-income nations due to the absence of advanced insurance and credit markets (Dhanaraj, Citation2016; Jensen, Citation2000).

3.3. Review of the empirical studies

Child schooling can be influenced by parents’ perception regarding the quality of the closest school, especially at the primary level (Ainsworth et al., Citation2005; Dhanaraj, Citation2016). At the secondary level, the progression of a child in grades majorly rests on the ability of the child to learn (Dhanaraj, Citation2016; Evans & Miguel, Citation2007, Citation2018). According to Dhanaraj (Citation2016), a female child has more probability of being enrolled early enough. However, the same does not apply to a first child. The availability of standard primary schools in the environment plays a significant role and negatively affects enrolment into primary school.

There is a higher record of dropout of female and older children. The more the number of children, the higher the rate of dropouts and the lower the level of grade advancement. Parent’s level and years of education significantly positively affect a child’s ability to continue schooling at the secondary level. Also, children from wealthy families have a higher chance of proceeding to secondary school. The study found the dropout rate to be higher in Muslim households and lower in households with social disadvantages. Household migration to a new location also influences a child’s schooling for some period (Dhanaraj, Citation2016).

Approximately 80% of the children in the world are in developing nations. Their economic status as adults lies on the level of education they can acquire (Glewwe & Kremer, Citation2006). The level of enrolment in school has been increasing in developing nations since 1960, which coincidentally is when Nigeria gained independence. However, several children still drop out of school while still very young, without learning much while in school. In several developing nations, there are private costs incurred by parents on education for tuition and other things like school uniforms. One way of improving the number of enrolments is to reduce or remove the financial constraints by lowering the cost of school or providing an incentive for student attendance (Glewwe & Kremer, Citation2006).

The development of education is a major determinant of a society’s development. The belief in Nigeria is that a higher level of schooling attracts better living conditions and citizen development. Education is seen as the key to developing the nation. However, the major socio-economic problems like the poor performance of the agricultural sector, political instability, poor transport and, above all, poverty are often linked to poor education, which ideally is needed to drive the nation (Adenike & Oyesoji, Citation2010).

According to Chudgar et al. (Citation2019), where Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda were examined, Nigeria showed the highest attainment in secondary education, with 21% of youths completing secondary education and 33% currently in secondary school. Despite those mentioned above, the country has the greatest disparity in attainment when compared to the other three countries.

As a global right of all humans, Universal Basic Education (UBE) should be for all in the 21st century, following the Universal declaration of human rights of 1948. It is, however, sad that as of 2013, of all the developing regions globally, according to the United Nations, only two of nine are on track (Smith & Joshi, Citation2016).

In the study of Mehrotra (Citation1998) where ten developing nations with a record of success in the expansion of UBE were evaluated, five main factors were identified as key to enrolment:

The government of the successful nations had essential social services in operation, which included the intervention of the health sector. It was the government’s duty to provide primary school education. Only one of the ten countries had up to 10% enrolment in a private primary school in 1975, with Cuba having 0% and South Korea with 1%. More expenditure goes to education, which was targeted at primary schooling. A study also deduced that Uganda and Malawi’s governments assumed responsibility for primary schooling and spent more of their budget on education, and the enrolment rate skyrocketed (Lincove, Citation2007, Citation2009). Many successful countries spent more on teaching materials and less on repetition and salaries compared to those that achieved less. Only one of the ten countries had direct costs in terms of tuition for primary school (Smith & Joshi, Citation2016). Mehrotra (Citation1998) concludes that the cushioning of the effects of children schooling on parents through reduced cost must have been responsible for the expansion in the rate of primary school enrolment in the countries studied.

According to Işcan et al. (Citation2015), school fees introduction in sub-Saharan Africa have led to a fall in enrolment in primary school, which has not translated to a rise in the quality of education. While UBE has been the focus of many governments and experts in policy development, more focus has been on policies improving access to primary education. Recently, efforts have been made to improve teaching quality. The returns on schooling are, however, a major factor in deciding whether a household will enrol a child or not (Mukhopadhyay & Sahoo, Citation2016).

It is not adequate to judge or use enrolment figures to indicate access to education. Being in school may not mean enrolment in school, and engagement in productive learning may differ from being in school (Filmer et al., Citation2006; Humphreys et al., Citation2015; Lewin, Citation2009). Hence, the identification of four different stages, which are: access in the form of enrolment, sustained access in terms of attendance, classroom access when in school, and lastly, engagement in meaningful education activity, learning and curriculum. These four collective stages make up quality and good educational access (Humphreys et al., Citation2015).

According to the Global Monitoring Report of 2004, education is a form of outcomes and processes that must be qualitatively defined. Quantity in respect of participation is secondary as that is just filling up the available spaces. Hence, years spent in education is practically essential, but when it comes to the real concept, it is a manipulative proxy regarding the processes and resulting outcomes (Benavot & Amadio, Citation2005; Humphreys et al., Citation2015).

Many out-of-school children in Northern Nigeria are enrolled in Quran Schools, which is not part of school attendance or enrolment figures (Humphreys et al., Citation2015). Though the rate of female schooling has been rising recently, illiteracy on the part of mothers in many developing nations remains high, and very few can train and teach their children (Francavilla et al., Citation2013; Motiram & Osberg, Citation2010).

Some studies show that for some children, the order of birth, gender bias and many siblings contributed to school (Abuya et al., Citation2012; Yi et al., Citation2012). In a situation where the first child has an advantage over others, having many siblings will lead to inequalities in schooling opportunities. It was further argued that birth order has a more significant effect than the number of siblings in a household (Mughal et al., Citation2019). On the contrary, Sawada and Loksbin (Citation2001) show that having many other female siblings can enhance their younger siblings’ completion of primary school education. This is because female relatives assist more with household labour. They further assert that the financial support of older male siblings also enhances the possibility of schooling for the younger siblings at the secondary school level.

Existing literature also reports how the inability to afford travel to schools that are not close to home was responsible for children dropping out of school, especially female children (Ali et al., Citation2012; Khan et al., Citation2011). According to Mughal et al. (Citation2019), the policy of automatic or progression without condition, irrespective of the children’s performance in examinations, is a trade-off between a poor schooling outcome in a later year or more retention in early classes. At the primary school level, failing or repeating classes may increase the chances of dropping out, but promoting a child to the next level without achieving the required grade-level outcome without condition results in poorer schooling outcomes in later years.

Three key determinants of schooling achievements have been suggested by Mingat (Citation2007): educational infrastructure, socio-economic status and culture; these three affect primary education. In Nigeria, most literature dwell on the intergenerational inequality between the North and South, which has been persistent. This is believed to be associated with the parental educational level and, above all, the socio-economic background (Agupusi, Citation2019; Dev et al., Citation2016; Kainuwa et al., Citation2013; Onwuameze, Citation2013).

The inequality in education in Nigeria has been associated majorly with ethnic politics (Ukiwo, Citation2007) and religious and cultural differences (Aluede, Citation2006; Antoninis, Citation2014). According to Dev et al. (Citation2016), the interest in group inequality is paramount since regional inequality and ethnoreligious inequality is a major issue in Nigeria. A good example is the literacy rate, an average of 23% in the northern region, whereas the southern region has a literacy rate of 87%. The irony is that the expenditure data on education for the country shows that the federal government spends more on Northern states. Nonetheless, they still record a high level of illiteracy rate when compared to the south (Aluede, Citation2006; Amzat, Citation2017). In 2012, the federal government of Nigeria succeeded in commissioning the construction of more than 160 free AlmajiriFootnote1 integrated model schools in the Northern part to fight the high rate of illiteracy in the region. According to Salau (Citation2020), a 2017 report showed that the primarily targeted groups, the Almajiris, had returned to the street, whereas schools are being converted for other purposes or depleting. The lack of success of the policy can be linked to a wrong idea of the existing problem; hence, the wrong approach in solving it, therefore, inappropriate policy prescription. The issue of persistent inequality in education in the nation is not accessibility to schools since primary education is universal and free. Instead, policymakers and scholars should pay more attention to parents’ attitudes to education (Agupusi, Citation2019; Isiaka, Citation2015; Nnadozie & Samuel, Citation2017; Olaniran, Citation2018). Studies on the challenges of the Almajiri’s education ignored the parent’s role in determining their children’s schooling. Generally, literature on parents’ roles emphasises the involvement of parents, socio-economic background, and the effect on the attainment of children’s schooling. Findings show that a parent can only be involved if they value education. When a parent’s level of educational application is low, there are some exceptional cases where the children still succeed. A child that has his/her high educational attainment to be dependent on his/her parent’s financial support could, however, be affected (Agupusi, Citation2019). According to Agupusi (Citation2019), there can be inequality in education, even when there is access to education and the needed finances. Therefore, expansion or reform of the educational sector or system may not be sufficient as a public policy instrument to lower persistent low school attainment and intergenerational inequality. Wilson-Strydom and Okkolin (Citation2016) suggested that a more complex policy strategy will be required to achieve the desired targets of SDG 4 by 2030.

Due to the progress recorded in the enrolment in primary schools, there is a rise in discussing secondary education in policy dialogues. SDG 4 requires all youth to finish quality primary and secondary education freely. This puts the completion of secondary education as a goal now at almost the same level as primary education attainment, which has initially been the focus of the government and donor efforts. Many nations have started to emphasise secondary school education completion with the aid of policies that will promote universal secondary education (Attanasio & Kaufmann, Citation2014; Kapinga, Citation2017), and all the efforts of government in this respect are followed by organised donor initiatives with a focus on secondary schooling (Chudgar et al., Citation2019; Null et al., Citation2017).

Recent attention to secondary education may be seen as more than an extension of the customary emphasis on primary education. It is debatable that this recent effort has an elevated status due to the effect of secondary education on several aspects of life outcomes for the youth and their community. Giving attention to this level of education can be justified based on equity, growth, reduction in poverty, and social cohesion (Chudgar et al., Citation2019).

According to Lim (Citation2019), female child records about 2.5 months lower education levels than their contemporaries’ averse level of education as their father suffers from an additional year of chronic illness. Several studies have examined peer effects on schooling but focused mostly on developed nations. The importance of social interactions on education with a focus on attendance and performance has been demonstrated (Ammermueller & Pischke, Citation2009; Bobonis & Finan, Citation2009; Gueye et al., Citation2018; Lalive & Cattaneo, Citation2009). How social interactions affect education was further explained by Akerlof and Kranton (Citation2002). The study developed a model depicting that social norms are linked to schooling. The study shows that social utility can be referred to as a cost to be beard by an individual if he/she does not align with the social norm. Hence, if a child is in an environment where education is not given high priority, this will reduce the chances of enrolment vis-à-vis (Gueye et al., Citation2018).

According to Nikolova and Nikolaev (Citation2018), the adverse effects of unemployment of a parent is not limited to the inability of a family to invest in essential resources like education, housing, and healthcare that will give room for a safe and quality learning environment (Nathan & Scobell, Citation2012). Households with lower Socio-Economic standard tends to be more vulnerable, and efforts to balance consumption tends to reduce the investment in child schooling (Dhanaraj, Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2016). Additional years of schooling due to compulsory schooling laws do not just impact on earnings and employment in the future. However, it also affects several factors like crime, sense of citizenship, fertility, and most importantly, health (Black et al., Citation2008).

The primary assumption is that children are affected by income through an increase in household consumption, which then improves the household’s living standard. However, households can decide to reallocate their resources to increase their child (Macours et al., Citation2012). Many studies on developing nations have identified nationwide economic crises as a factor that can reduce a family’s budget for children’s education, thereby leading to an increase in dropout and infant mortality (Abuya et al., Citation2012). Contrary to economic crises that are often not expected and mostly lead to recessions that reduce the welfare of the entire society.

In developing regions, the existing evidence in respect of schooling is centred on supply-side interventions. Very little information is available on demand-side interventions that directly influence the investment of human capital in children by reducing financial constraints. The decision of a household to invest in a child or children to obtain an additional year of schooling usually occurs when the costs of the current value are less than the projected benefits when using the traditional model of parental investment in human capital for children (Becker, Citation1962; Mincer, Citation1997).

The shock of unemployment leads to a significant rise in the probability of a child entering the labour force, dropping out of school and failing to continue schooling (Duryea et al., Citation2007). The adverse effects of poor schooling on society are a high unemployment rate, poor health, violence, crime, drug abuse, civil conflicts, and loss of income, among others (Belfield & Levin, Citation2007; Smith & Joshi, Citation2016).

There is a connection between parents’ employment and children’s schooling, as also household income and children’s activity (Francavilla et al., Citation2013). These relationships, therefore, need further clarification, and the need to differentiate between a mother’s and father’s employment status may be more helpful.

Concerns are being raised in respect of women’s employment status and schooling of their offspring, among which is the fact that teaching a child at home by the mother rather than going out for paid job may result in higher returns socially in respect to human capital growth (Behrman et al., Citation1999; Behrman & Rosenzweig, Citation2002; Francavilla et al., Citation2013). However, it is difficult to dispute that empowering a woman through employment will boost her ability to take vital decisions in the household. Though the rate of female schooling has been rising recently, illiteracy on the part of mothers in many developing nations remains high, and very few can train and teach their children (Francavilla et al., Citation2013; Motiram & Osberg, Citation2010).

However, it is essential to understand that the uncertainty in income due to employment stability influences the schooling decision in low-income nations (Kazianga, Citation2012). A parent’s employment status, which is directly related to income, influences education outcomes such as enrolment, year of education completed, and expenditure on child schooling. The uncertainty in income resulting from unemployment can lead to a high number of the population not enrolling in school (Kazianga, Citation2012).

Parent unemployment has a negative impact on the enrolment and education performance of adolescent children, but it has little or no effect on early childhood. The effect of unemployment can be seen in the poor performance at the secondary level of education. Where parents are highly educated, the enrolment and performance at the secondary level are not affected by parents’ unemployment. Nevertheless, a child of a parent that is highly educated is highly likely not to proceed to tertiary education if the parents are exposed to unemployment, hence, due to low economic resources at the disposal of the parent when unemployed, there tends to be a need to seek for support while taking decisions on child’s education (Lehti et al., Citation2019). This study noted that the age at which the parent is exposed to unemployment and the educational level attainment of the parent are things that should be considered, among other factors, while checking for the effect of parental unemployment on children’s education (Lehti et al., Citation2019).

The unemployment status of a parent in later youth has an effect on the educational choices and prospects of the children because choices on education are usually concluded during adolescence (Erikson & Jonsson, Citation1996; Lehti et al., Citation2019). Socio-psychological factors tend to have more effects on older children as they are quick to see the continuation of higher education as a risk when their parents become unemployed as they are fully aware of the decline in their family status (Andersen, Citation2013; Brand & Thomas, Citation2014; Lehti et al., Citation2019).

The study of Andersen (Citation2013) shows that when the parent’s unemployment leads to relative status deprivation, it tends to affect a child’s educational prospects and ambition negatively. Due to parental unemployment, the expectation of a child may fall, and this can make such a child drop out (Brand, Citation2015; Lehti et al., Citation2019). When the level of risk aversion is high, the probability of a child leaving secondary school education for vocational is high (Breen et al., Citation2014 Lehti et al., Citation2019).

According to Di Maio and Nisticò (Citation2019), the fall in household earnings due to job loss may be a key reason for a child’s withdrawal from school. The loss of employment by the head of household immediately affects child schooling negatively as it leads to a rise in the probability of dropping out. Existing literature identifies poverty resulting from unemployment as the leading factor for dropping out (Abuya et al., Citation2012; Al-Hroub, Citation2014; Dakwa et al., Citation2014; Mughal et al., Citation2019).

It is clear that there are several studies on child schooling/out-of-school children, but there is a deficiency in studies that focus on underdeveloped countries. Furthermore, there is an absence of micro research on child schooling at the state/Local government level with a special focus on communities with schools for all levels of education from basic/primary level to tertiary level. Above all, very few studies have been conducted on child schooling in Nigeria.

4. Methodology

The methodology and the techniques are explicitly described by starting with the research design, and then the description of the study area, explanation of sample techniques and procedures, questionnaire design, and mode of administration, specifically the model and techniques used in estimation.

4.1. Research design

This study adopts the quantitative research design (cross-sectional analysis of Households). This study applied a survey method for the research, using a structured questionnaire, and these questionnaires were distributed/administered to the head of households.

4.2. Technique of data collection

This section shows the procedures used in collecting data. It explains the approach and method of this study. This study employed a quantitative method of research.

4.3. Survey method

The method of data collection in this study is the survey method. This was done by collecting data from some part of the population which can be referred to as a sample since it will be time-consuming, tedious, and expensive to focus on the entire population.

4.4. Area and population of the study

The study was carried out in five local governments spread across the three senatorial districts in Kwara State, Nigeria. The respondents are randomly selected households in Ilorin, Lafiagi, and Offa. These three locations satisfy the condition described in the introduction, that is, the availability of institutions of learning to provide education and the availability of government offices to provide employment. These three locations are spread across the three senatorial districts: Kwara Central, Kwara North, and Kwara South.

4.5. Sampling plan/procedure

A sample size of 30 is appropriate and often advised as the minimum sample size to cater for all required characteristics and adjustments (Melody, Citation2008; Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). This study however piloted a total of 45 questionnaires.

All the explanatory variables for the models specified were examined for inclusion in this study.

The sample size is calculated with the formula below.

where n is the sample size, N is the population size, and e is the level of precision. This is a simplified formula of Yamane (Citation1967) with the assumption that p, which is the proportion of variability, is (0.5), a confidence interval of 95%, and the margin of error is (0.05).

This study used the 2006 national population census, which is the most recent. shows the summary of the population of the selected study area. The table further shows the proposed sample size based on the calculation from the formula above. This calculation is also closely in line with Glenn (Citation1992).

Table 4. Population and household sample size (Kwara State).

From , a total of 1189 questionnaires are sufficient for this study. This is a sufficient sample size for this study as the sufficient requirement for the analysis of probability models which are non-linear, is 500 sample size (Studenmund, Citation2014; Ye & Lord, Citation2014).

This study adopts a random and systematic probability sampling technique. For the questionnaire, the households were randomly selected with the aim of giving equal opportunity to all households, as proposed by Agresti and Finlay (Citation2009). However, the communities were divided into areas for enumeration. This is to ensure that there is no spatial dependence to ensure adequate representation (see Cheng & Masser, Citation2003). At the end of the survey, 1120 questionnaires were returned and used for the study. This represents the number of households surveyed but this generally have about 1972 children in total.

4.6. Questionnaire design

The objective of this study and theory serves as a guide for designing the research questionnaire and model specification. This aims to ensure that there is no omission of relevant information while analysing data. The questions cover the head of households, individuals in the households, household demographic characteristics, community characteristics, education, and employment status of the household head. The questionnaire includes both open-ended and close-ended questions.

4.6.1. Conceptual framework for child schooling/out-of-school children

This framework is inspired by Becker (Citation1964) emphasising the importance of the child’s individual characteristics, such as age, gender, household income, family structure, birth order, and parental employment. Also, the availability of schools and environmental factors have been identified. Other studies also stress the importance of age, the number of children, parental education attainment, and income (see Glick & Sahn, Citation2006; Handa et al., Citation2004; Tansel, Citation1997, Citation2002). Furthermore, Kabubo-Mariara and Mwabu (Citation2007) and Olaniyan (Citation2011) further shows the importance of child characteristics, parental education, household characteristics, quality and cost of education, and gender in determining child schooling. Abafita and Kim (Citation2015) shows that individual, household and community characteristics like education of household head, age, birth order, and family size affect schooling, just like the study of Haile and Haile (Citation2012). Earlier study like Connelly and Zheng (Citation2003) shows that location, sex, parental education, family structure, having a sibling or siblings, household income, and government education policy will determine child schooling. The study of Iram et al. (Citation2008) also aligns with these studies.

In this study, child schooling enrolment is the focus. This is to cater for the possibility of dropping out after initial enrolment. Three major characteristics determine child schooling: individual characteristics of the child, household characteristics, and environmental characteristics. Theories like the rational action theory explain how gender, education decisions, and performance, among others, determine child schooling (see Breen & Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Goldthorpe, Citation1996).

Theories also explain household characteristics which can be further divided into three. Human capital characteristics are explained by human capital investment theory and the relative risk aversion under the rational action theory (Becker & Tomes, Citation1986; Goldthorpe, Citation1996). Furthermore, economic characteristics are explained by human capital investment theory and differences in resources under the rational action theory.

4.7. Specification of models for estimation

This section discusses the specified estimation models and procedures. This study used multinomial logistic regression for child schooling enrolment.

4.8. Multinomial logistic model

This is generally employed when there is a need to analyse categorical placement. This categorical placement can either be in or the probability of category membership on a dependent variable which is usually based on multiple independent variables (Starkweather & Moske, Citation2011). The assumptions of multinomial logistic regression include the independence of the dependent variables. Furthermore, there is the assumption of non-perfect separation.

4.9. Model specification

The objective of this study is to ascertain the determinants of child schooling in households in Kwara State, Nigeria. To achieve this objective, the child schooling category is divided into three possible outcomes; never enrolled, enrolled before and enrolled. The model for child schooling enrolment is as follows:

(1)

(1)

where

is the intercept,

–

are coefficients of the predictor variables, and

is the stochastic term which represents the other predictors that are not included in the model. All the variables in the model are explicitly described in .

Table 5. Description of variables for child schooling enrolment and child schooling attainment.

4.10. Sources of data

To investigate the research objectives of this study, the researcher conducted a Kwara State Household child schooling survey in 2022 and published in Ojuolape and Mohd (Citation2022a) and Ojuolape and Mohd (Citation2022b).

5. Empirical results and discussion

The first part of this section presents the household characteristics statistics and the presentation and interpretation of results on household child schooling/out-of-school household children in Kwara State, Nigeria.

5.1. Descriptive statistics of personal and household characteristics

This section shows the descriptive statistics on socioeconomics as regards personal and household characteristics. This includes statistics on location and other variables.

presents the descriptive statistics of the study using mean, minimum and maximum. The descriptive statistics show that for school-aged children, the mean age is 11.9 years and falls within the bracket of 3–17 years. Seventeen is the highest age in the sub-sample, and three is the lowest age amongst the children. The average household income of the sample is N120,704.7, and this is higher than the average annual cost of education per child, which is N53,912.64.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of the relevant variables.

Interestingly, the average distance from school is higher than from economic activities. The average distance from school is 4.97 km/h, while the average distance from economic activities is 1.47 km/h. Although the distance from both places has the same minimum, the highest distance from the school is 120 km/h. The largest size of the sampled household is 9, while the smallest is 2. The average size of the household is 5.22, and the average number of dependants is 0.47.

The second part of the table gives further characteristics of the respondents. It shows that children consist of more males, which constitutes 72.85%. All the respondents have been in a marital relationship at one point or the other. Although a larger percentage of the respondents are still married (74.81%), and some are married to more than one wife (18.7%). A small fraction of about 3.42% is divorced, with 8.11% separated, and widow/widower is 13.59%. In investigating the educational status of the children, 42.6% are enrolled in school, a larger percentage of 46.15% of the children are dropped out, and a small fraction of 11.26% have never been to school. In comparison, over (70%) of the children have access to secondary education. Most of the children (69.32%) are from rural areas.

5.2. Determinants of child schooling/out-of-school children in Kwara State, North central Nigeria

The dependent variable is Child schooling enrolment, which has three different categories: Children without education, Children that dropped out of school, and Children in school. These three groups are also referred to as never enrolled, was enrolled, and enrolled, respectively. The frequency and percentage distribution of the three groups of child schooling enrolment is presented in . Table reveals that 11.26% of the children in Kwara State are not enrolled in school, while 46.15% are out-of-school. 42.60% of Kwara State children are enrolled in school. This is less than half of the children between the ages of 3 and 17 years in Kwara State, and the implication is that more than 50% of the children in Kwara State are either out-of-school or never enrolled in school. This is also indicated by the cumulative 57.40% of never enrolled and out-of-school categories.

Table 7. Child schooling enrolment distribution.

5.3. Interpretation of coefficient

presents the multinomial logit regression results to examine the determinants of child schooling and out-of-school children in Kwara State, Nigeria, which are divided into two categories: was enrolled (representing the out-of-school children) and enrolled (representing the children in school). First, the study examined the first category, out-of-school children. The regression coefficient shows that two out of the six independent variables in the model are statistically significant at 1 and 5% levels. The constant term is positive and significant. It indicates that there are other positive determinants of out-of-school children aside from the variables considered in the model. The results show that age is a positive and significant determinant of out-of-school children in Kwara State. Thus, a year added to the age of children increases the log odds of out-of-school children by 0.04 unit, holding other variables constant. Also, the educational cost is a negative and significant determinant of out-of-school children. This indicates that a 1% increase in the cost of education reduces the log odds of out-of-school children by 0.13 units, provided that other variables are fixed.

Table 8. Multinomial logistic regression coefficient, relative risk ratio, marginal effect and robust results of the determinants of child schooling/out-of-school children in Kwara State, Nigeria (Reference Category: Never Enrolled).

The robust result is suitable when there is a possible outlier problem and violation of the distribution assumptions. The robustness result gave similar findings in terms of sign and significance except for the parental employment status variable. Unlike the coefficient of the regression estimate, which shows a negative and insignificant value, the robust result shows that the variable is negative but significant at a 10% significance level. Thus, the parental employment status is also observed to decrease the log odds of out-of-school children by 0.10 units on average, given that other variables are constant. The robust result, in this case, implies that the regression coefficient may not be free from the problem of heteroscedasticity. Thus, more emphasis is placed on the robust result.

The second category shows that all the variables except parental educational attainment are significant determinants of children in school. Moreover, the positive and significant coefficient of the constant term shows that other variables not included in the model positively and significantly determine the children’s schooling. Specifically, the significant determinants are age, parental employment status, access to secondary school, and rural and educational costs. Age shows a positive determinant at the 1% level, holding all other predictor variables constant. This means that as a one-year is added to the age, the log odds of children in school increase by 0.13 units, given that all other independent variables in the model are held constant. Also, parental employment status is a negative but significant determinant of children in school. This implies that holding other variables constant, the parents’ employment status decreases the log odds of children in school by 0.16 units, holding other variables constant.

Moreover, access to secondary school is a positive determinant of children in school. An increase in access to secondary school increases the log odds of children in school by 0.39unit, ceteris paribus. Rural and educational costs are both negative and significant determinants of children in school. Implying that an increase in these variables decreases the log odds of children in school by 0.62 units and 0.14 units, provided all other predictor variables in the model are fixed. The robust results validate these results. The robust results presented almost similar results, with only the parental educational status as the insignificant variable. This means that the result of the logit regression, in this case, is free from the problem of heteroscedasticity.

5.4. Interpretation of relative risk ratio

column III presents the relative risk coefficient of the independent variables. The table shows that against the referenced category of never enrolled, three of the six independent variables have a relative risk coefficient greater than 1, while the others are less than 1. More specifically, age, parental educational attainment, and access to school have a relative risk ratio coefficient greater than 1. Rural, parental employment status and education cost have relative risk ratio coefficients of less than 1. This indicates that for the out-of-school children category, an increase in the age of children increases the relative risk of being out-of-school children by a factor of 1.05, holding other variables constant. This is significant at a 1% significance level. The relative risk ratio of educational cost is less than 1 and significant at 5%. This implies that an increase in education cost reduces the relative risk of being out-of-school children by a factor of 0.87, provided all other independent variables in the model are constant.

For the second category, changes in all the variables significantly affect the relative risk of being enrolled in school to out-of-school. The relative risk ratio coefficient of age and access to secondary school is greater than 1, while rural, parental employment status and education cost are less than 1. Specifically, an increase in the age of children increases the relative risk of being enrolled in school to being out of school by a factor of 1.14, holding other variables constant. This variable is significant at 1%. Also, access to secondary school is significant at 5%, and it suggests that the relative risk of being enrolled in school to being unenrolled in school increases by a factor of 1.48 for every change in access to secondary school, holding other variables constant.

Moreover, changes in parental employment status and educational cost are significant at a 5% level while rural is significant at a 1% level. This finding implies that for every change in parental employment status, the relative risk of being enrolled in school to being unenrolled in school decreases by a factor of 0.84, provided other variables are fixed. Similarly, the relative risk of being enrolled in school to being unenrolled in school declines by a factor of 0.53 for every change in rural. Finally, an increase in educational cost reduces the relative risk of being enrolled in school to being unenrolled by a factor of 86.

5.5. Discussion of results

The results of the determinants of child schooling and out-of-school children reveal that there are three major drivers of out-of-school children in Kwara State, Nigeria. These drivers are age, parental employment status and educational cost. Additional year to the age of children increases the out-of-school children. This aligns with previous studies such as Dhanaraj (Citation2016), who asserted that there is a high level of school dropout and fall in grade advancement as the children grow to a stage where they are to proceed to a secondary level of education.

Meanwhile, the education cost has a negative effect on out-of-school children. This finding contrast the a priori expectation because the higher the educational cost, the more likely children would experience dropout because of the inability of their parents to pay tuition fees and other study fees like uniform cost, etc., as observed in previous studies such as Işcan et al. (Citation2015). This also aligns with studies such as Glewwe and Kremer (Citation2006), who suggested in their study that one way of improving the number of enrolments is to reduce or remove the financial constraints by lowering the cost of school or providing an incentive for students’ attendance. As a result, in the case of this study, primary education demand in Kwara State follows the normal demand. This implies that the parent would not enrol their children at all with a higher educational cost, thus increasing the out-of-school children.

Moreover, the parent’s employment status follows a priori expectations. One would expect that as the employment status of the parent changes, the out-of-school children reduce. In other words, the number of out-of-school children decreases as more parents are gainfully employed or get better jobs. This is because the parents will earn more income, making it possible for them to pay their children’s school fees and other charges.

Meanwhile, in the second category, the study also identifies age, parents’ employment status, educational cost, rural and access to secondary school as major drivers of a child’s schooling. Age and access to schools are positive drivers, while parents’ employment status, educational cost and rural are negative drivers of a child’s schooling. By implication, every addition to the age of the children and the presence of secondary schools increases the child’s schooling. In contrast, the higher the employment status of parents, the higher the educational cost, and the rurality of the children reduce the chances of enrolling in primary education. From these findings, one could deduce that education demand follows the law of demand. The higher the cost of education, the lower the probability of a child’s schooling.

According to Agupusi (Citation2019), parents’ socio-economic status and education level are important determinants of a child’s school. If a parent values education, the tendency for child schooling would increase and vice versa. Interestingly, this study found that parents seem to be more concerned about other things than the children’s education in Kwara State. With employment status reducing the chances of a child’s schooling, there are other competing needs to which parents in the observed region give more financial attention. This is contrary to the findings of Mingat (Citation2007). Moreover, society’s development also plays a significant role in influencing child schooling. Lower community development reduces child’s schooling, while higher community development (movement from the rural state) increases child’s schooling. This is plausible because of the level of societal change, availability of social amenities and enlightenment that comes with such structural transformation.

5.6. Postestimation tests

The study performed post-estimation tests to check if the results met the estimation assumptions. This is vital to validate the findings of the study. The study employed the Chi-Square joint test, Chi-Square test for combining categories, independence of irrelevant alternative test, multicollinearity test and measures of fit test. All the results however satisfy the assumptions.

6. Conclusion

The study reveals that the long distance to schools is a deterrent to enrolment, resulting in a high dropout rate. 11.26% of school-aged children have never been enrolled, with many residing in rural areas. These areas’ lack of family planning contributes to a higher birth rate, exacerbating enrolment challenges.

In terms of determinants, the study identifies age and educational costs as significant factors at the initial stage. However, during further analysis, parental employment status becomes a significant factor, reducing the likelihood of children being out of school. In the second category, access to school increases the chances of enrolment, while living in rural areas and higher education costs have a negative impact, as expected. The study also finds that as the age of the household increases, the likelihood of children being out of school also rises, aligning with previous research by Dhanaraj (Citation2016), that highlighted increased dropout rates and a decrease in grade level advancement as children grow older.

Furthermore, the study indicates that higher education costs increase the likelihood of children being out of school, consistent with the findings of Glewwe and Kremer (Citation2006) and Işcan et al. (Citation2015). Surprisingly, parental employment status negatively affects child schooling in Kwara State, suggesting that parents prioritize other matters over their children’s education, contrary to the findings of Agupusi (Citation2019; Mingat, Citation2007).

6.1. Policy implication and recommendation

This study highlights the importance of formulating effective policies to improve child schooling. Providing schools alone does not guarantee attendance, and obtaining a certificate does not guarantee employment. Based on the study’s findings, several policy implications can be derived.

Firstly, the study reveals that the average distance from schools and access to schools significantly affect school enrolment, leading to a high rate of out-of-school children. To address this issue, it is crucial to construct schools in rural areas, considering that many out-of-school children reside there. Providing easy transportation options for children can also serve as a temporary solution. Additionally, raising awareness about family planning can help ensure that families only have children they can afford to educate.

Secondly, the study indicates that higher education costs correlate with a higher rate of out-of-school children. To combat this, the government should enhance its universal basic education scheme by constructing schools and offering tuition-free education without hidden costs. The current practice of publicizing tuition-free education while still imposing charges such as parent-teacher association dues discourage enrolment.

Lastly, the study highlights the positive influence of parental educational attainment on child schooling. To promote education, parents with lower educational attainment should be sensitized and encouraged to recognize the importance of educating their children.

In summary, the study underscores the need for policies that address factors such as distance to schools, access, education costs, and parental educational attainment to improve child schooling outcomes.

Ethics statements

Ethical clearance was approved for Household child schooling/Out-of-school children by Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) Research Ethics Committee (Human) (USM/JEPeM/21020151).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. This research received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Data availability

Dataset for Child schooling/Out of school children in Kwara State, Nigeria. (Original Coded Data) (Mendeley Data) https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/82zygyrsk3/4.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adebayo Mohammed Ojuolape

Adebayo Mohammed Ojuolape is a Lecturer in University of Ilorin, Nigeria, he holds a PhD in Economic Development, from School of social sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, M.Sc. International Economics, Finance, and Development, from University of Surrey, United Kingdom, B.Sc. Economics from University of Ilorin, Nigeria. His area of research is on multi-dimensional deprivations. He has published many articles with many in progress.

Saidatulakmal Mohd

Saidatulakmal Mohd is currently a Professor and Director at the Centre for Research on Women and Gender (KANITA), Universiti Sains Malaysia. She joined the university in 2005 upon completion of her Ph.D. from the University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. Her main area of research is welfare economics, concentrating more on the wellbeing of vulnerable groups and social protection.

Notes

1 Almajiris can be described as adult street beggars or children that have been sent to a traditional Arabic or Quranic school from the tender age of around three years old. According to UNICEF, this group of people accounts for about 80% of out-of-school children in northern Nigeria. Close to 10 million boys of about 4 to 17 years of age are roaming the streets in the North, and many can be found in Kaduna state, Kano state and Sokoto state. See Bala Muhammad report: https://www.dailytrust.com.ng/news/columns/revisiting-the-almajiri-issue/190684.html.

References

- Adenike, A. O., & Oyesoji, A. A. (2010). The relationship among predictors of child, family, school, society and the government and academic achievement of senior secondary school students in Ibadan, Nigeria. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.196

- Abafita, J., & Kim, C. (2015). Determinants of childrens schooling: The case of Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(8), 1130–1146. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2095

- Abuya, B. A., Onsomu, E. O., & Moore, D. (2012). Educational challenges and diminishing family safety net faced by high-school girls in a slum residence, Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.02.012

- Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2009). Logistic regression: Modeling categorical responses. In Statistical methods for the social sciences (4th ed., pp. 483–512). Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776407081165

- Agupusi, P. (2019). The effect of parents’ education appreciation on intergenerational inequality. International Journal of Educational Development, 66, 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.09.003

- Ainsworth, M., Beegle, K., & Koda, G. (2005). The impact of adult mortality and parental deaths on primary schooling in north-western Tanzania. Journal of Development Studies, 41(3), 412–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022038042000313318

- Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2002). Identity and schooling: Some lessons for the economics of education. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(4), 1167–1201. https://doi.org/10.1257/.40.4.1167

- Al-Hroub, A. (2014). Perspectives of school dropouts’ dilemma in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Educational Development, 35, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.04.004

- Ali, U., Hussain, L., & Khan, M. A. (2012). Determinants of drop out in primary schools of Khyber Pakhtun KHWA as perceived by the teachers. Gomal University Journal of Research, 28(1).

- Aluede, R. O. A. (2006). Regional demands and contemporary educational disparities in Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences, 13(3), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2006.11892548

- Ammermueller, A., & Pischke, J. (2009). Peer effects in European Primary Schools: Evidence from the progress in International Reading Literacy Study. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(3), 315–348. https://doi.org/10.1086/603650

- Amzat, A. (2017, July 24). Despite decades of funding, literacy level in the northern states remains low. The Guardian. https://guardian.ng/news/despite-decades-of-funding-literacy-level-in-the-northern-states-remains-low/

- Andersen, S. H. (2013). Common genes or exogenous shock? Disentangling the causal effect of paternal unemployment on children’s schooling efforts. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr088

- Antoninis, M. (2014). Tackling the largest global education challenge? Secular and religious education in northern Nigeria. World Development, 59, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.017

- Attanasio, O. P., & Kaufmann, K. M. (2014). Education choices and returns to schooling: Mothers’ and youths’ subjective expectations and their role by gender. Journal of Development Economics, 109, 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.04.003

- Babatunde, R. O., Omoniwa, A. E., & Ukemenam, M. N. (2019). Gender analysis of educational inequality among rural children of school-age in Kwara State, Nigeria. Agricultural Science and Technology, 11(3), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.15547/ast.2019.03.046

- Baird, S., Ferreira, F. H. G., Özler, B., & Woolcock, M. (2014). Conditional, unconditional and everything in between: A systematic review of the effects of cash transfer programmes on schooling outcomes. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 6(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2014.890362

- Becker, G. (1964). Human Capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship

- Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49. http://www.jstor. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

- Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human capital and the rise and fall of families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3 Pt. 2), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/298118

- Behrman, J. R., Foster, A. D., Rosenzweig, M. R., Vashishtha, P., Journal, T., & Aug, N. (1999). Women’s schooling, home teaching, and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 107(4), 682–714.

- Behrman, J. R., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2002). Does increasing women ‘ s schooling raise the schooling of the next generation ? Reply. American Economic Review, 95(5), 1745–1751.

- Belfield, C. R., & Levin, H. M. (2007). The price we pay: Economic and social consequences of inadequate education. Brookings Institution Press.

- Benavot, A., & Amadio, M. (2005). A global study of intended instructional time and official school curricula, 1980-2000. 1–46.

- Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2008). Staying in the classroom and out of the maternity ward? The effect of compulsory schooling laws on teenage births. The Economic Journal, 118(530), 1025–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02159.x

- Bobboyi, H. (2019, June 9). States owe counterpart funds, can’t access N84bn from UBEC. Punch. https://punchng.com/states-owe-counterpart-funds-cant-access-n84bn-from-ubec/

- Bobonis, G. J., & Finan, F. (2009). Neighborhood peer effects in secondary school enrollment decisions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 695–716. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.4.695

- Brand, J. E. (2015). The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237

- Brand, J. E., & Thomas, J. S. (2014). Job displacement among single mothers: Effects on children’s outcomes in young adulthood. AJS; American Journal of Sociology, 119(4), 955–1001. https://doi.org/10.1086/675409

- Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. In Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346397009003002

- Breen, R., van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Jaeger, M. M. (2014). Deciding under doubt: A theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu039

- Bruns, B., Mingat, A., & Rakotomalala, R. (2015). Education by 2015: A chance for every child. The World Bank.

- Care, E. C., & Ecce, E. (2007). Nigeria

- Cheng, J., & Masser, I. (2003). Modelling urban growth patterns: A multiscale perspective. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 35(4), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1068/a35118

- Chudgar, A., Kim, Y., Morley, A., & Sakamoto, J. (2019). Association between completing secondary education and adulthood outcomes in Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda. International Journal of Educational Development, 68(May), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.04.008

- Connelly, R., & Zheng, Z. (2003). Determinants of school enrollment and completion of 10 to 18 year olds in China. Economics of Education Review, 22(4), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(02)00058-4

- Dakwa, F. E., Chiome, C., & Chabaya, R. A. (2014). Poverty-related causes of school dropout- dilemma of the girl child in Rural Zimbabwe. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 3(1), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v3-i1/792

- Dev, P., Mberu, B. U., & Pongou, R. (2016). Ethnic inequality: Theory and evidence from formal education in Nigeria. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 64(4), 603–660. https://doi.org/10.1086/686739

- Dhanaraj, S. (2015). Health shocks and the intergenerational transmission of inequality: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India. WIDER Working Paper, 04(January).

- Dhanaraj, S. (2016). Effects of parental health shocks on children’s schooling: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India. International Journal of Educational Development, 49, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.03.003