Abstract

Farming communities confronted with climate change adopt formal and informal adaptation strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change. While the environmental and social effects of climate change are well documented, there is still a dearth of literature on girl-child marriage (formal marriage or informal union between a child under the age of 18 and an adult or another child) as a response to the effects of climate change. In this research, we ask if girl-child marriage is promoted as a social protection mechanism first, rather than as simply a response to climate-induced poverty. We use qualitative semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions to explore this question in a rural farming community in Northern Ghana. Our findings reveal that climate change shocks result in poverty and compel farmers to marry off their young daughters. The unmarried girl-child is perceived as an ‘extra mouth to feed’, a liability whose marriage becomes a strategy for protecting the family, the family’s reputation, and the girl child. The emphasis in girl-child marriage is not on the girl-child as an individual but on the family as a group. Hence, what is good for the family is assumed to be in the best interest of the girl-child. We place our analysis at the intersection of climate change, social protection, and the incidence of girl-child marriages. We argue that understanding this link is crucial and can contribute significantly to our knowledge of girl-child marriage as well as our ability to address this in Sub-Saharan Africa.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Africa is exposed to various climate stresses and is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Most African countries have climates that are among the most variable in the world on seasonal and decadal time scales. Several climatic impacts occur leading to famine and widespread disruption of socio-economic well-being (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2013). Few et al. (Citation2004) predict that the African continent is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events leading to flooding, drought, and a rise in sea levels. These pose a risk to human health and human life. Again, extreme climate events in Africa are likely to lead to a scarcity of potable water and subsequently increase water conflicts along almost all the 50 river basins in Africa (Ashton, Citation2002, De Wit & Jacek, Citation2006). In addition to conflict and the loss of human life, another impact of climate change is its effect on agriculture. Antwi-Agyei et al. (Citation2013) emphasises agriculture as the most climate-dependent area of human life. In sub-Saharan Africa, since a significant percentage of farmers are subsistence farmers, they rely heavily on rainfall for irrigation. The implication is that climate change is likely to cause a decrease in most of the subsistence crops across Africa, e.g. sorghum in Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Zambia; maize in Ghana; Millet in Sudan; and groundnuts in the Gambia. Owing to an upsurge in severe weather conditions and variability of weather patterns, climate change is predicted to negatively affect agricultural production (Kotir, Citation2011). There is also the probability that the number of people at risk of hunger will increase by 2080, for which Africa may well account for the majority (Fischer et al., Citation2002). The realization that climate change-associated risks to agricultural production also serve as threats to the quality of life on a universal scale has led to a growing consideration for adaptation and mitigation strategies for agriculture (Howden et al., Citation2007 as cited in McCarl, Citation2010).

Agriculture continues to play a pivotal role in the Ghanaian economy. Approximately 70% of the Ghanaian population derives their livelihood from agricultural activities. The implication is that climate change and its effect on rainfall patterns is of great concern to Ghanaian farmers (Assan et al., Citation2018). For instance, in the northern regions of Ghana, temperatures recorded yearly usually exceed previous years, leading to a decline in agricultural production since there is little or no access to irrigation facilities. Fluctuation in rainfall patterns and the temperature has also led to an ecological imbalance, causing an influx of pests and diseases (Ndamani & Watanabe, Citation2015). Farming communities confronted with climate change effects adopt strategies to mitigate the risks associated with climate change (Ndamani & Watanabe, Citation2015). Formal (state-proposed) and informal (individual/family-led) adaptation strategies have been used to mitigate the effects of climate change in rural communities in Ghana (Abass et al., Citation2018). Government agencies in Ghana such as the Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation (MESTI), the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Savannah Agricultural Research Institute (SARI) play vital roles in the implementation of formal climate change adaptation strategies (Abass et al., Citation2018). As mentioned by Assan et al., (Citation2018) some of the formal adaptation strategies in Ghana include the provision of storage facilities for farmers, training programs on composting for farmers, and training of farmers on alternative sources of livelihood including soap making and shea processing. Extension workers from government departments also provide weather information to local farmers in-person and through electronic media (Abass et al., Citation2018).

While state-led adaptation strategies are important and contribute to the wellbeing of vulnerable farming communities, informal adaptation strategies are equally relevant. Informal adaptation strategies are important because they emerge from the lived realities, resilience and innovation of local populations (Belay et al., Citation2017; Cobbinah & Anane, Citation2016; Mugambiwa, Citation2018). Consequently, they give formal policy makers ideas about new formal adaptation strategies that may work for specific people within specific communities. On the other hand, informal adaptation strategies may pose significant danger or risk to the wellbeing of people within societies. For instance, there is some research evidence linking the increase in girl-child marriage (defined by UNICEF, Citation2023, p. 1 to include all marriages and unions, either formal or informal, between a child under the age of 18 and an adult or another child) in certain parts of Africa to the informal adaptation mechanisms of families to the effects of climate change (McLeod et al., Citation2019). The existing literature focuses mostly on the effects of climate change on the physical and social environment (Belloumi, Citation2014; Mashizha et al., Citation2017). Other authors have documented the effects of poverty on girl-child marriage (Bartels, Michael, Roupetz et al., Citation2018; Ijeoma et al., Citation2013). Ghosh (Citation2011) has also documented the impact of gender bias on girl-child marriages. These notwithstanding, there is still a dearth of literature on girl-child marriage as a social protection/informal adaptation strategy of vulnerable farming families to the effects (e.g poverty) of climate change. This is where we situate our study.

We use qualitative semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions to examine whether girl-child marriage is promoted as a social protection mechanism first, rather than as simply a response to climate induced poverty. We place our analysis at the intersection of climate change, social protection and the incidence of girl-child marriages (Asare & Forkuor, Citation2023). We believe that our study contributes to the literature by linking climate change, and ineffective and non-existing formal social protection mechanisms to girl-child marriage. We argue that understanding this link is crucial and can contribute significantly to our knowledge of girl-child marriage as well as our ability to develop context relevant social protection mechanisms that reduce the incidence of girl-child marriages. The rest of the paper is structured in the following way. We present a brief overview of the state of knowledge about climate change and girl-child marriage. Through this, we raise questions that inform our study. Subsequently we present an overview of the context of study and explain the methods we used to collect data for this study. In the next section we present the results interpretively, discuss it in relation to the literature on social protection and conclude our arguments.

Climate change and girl-child marriages: a brief overview of the literature

The scholarly work of Naveed and Butt (Citation2020) indicates poverty, illiteracy, backwardness, and religious fundamentalism as the main causes of girl-child marriage in Asia. The study again highlights that some other drivers of child marriage include the notion of honor, preserving traditions, maintaining power control, male domination over females, and gender discrimination. In relation to girl-child marriage, Ghosh (Citation2011, pp. 16–17) writes: ‘modern factors like poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, lack of awareness and development deficit are equally responsible for this’. We provide a brief review of some of these arguments around the phenomenon of girl-child marriage in this section. We divide the review into 4 sub-sections focusing on (1) the relationship between poverty and girl-child marriage; (2) Norms and customs as causes of girl-child marriage; (3) climate change and girl-child marriage; and (4) consequences of girl-child marriage.

Poverty and Girl-Child Marriage. Generally, the literature on girl-child marriage in different contexts suggest that poor families perceive girl-child marriage as a way to protect their daughters from unwanted pregnancy and at the same time provide some security for the future of their daughters (Mcleod et al., Citation2019). According to UNICEF (2001), some poor families and communities argue that girl-child marriage serves as an avenue to protect the girl child from giving birth outside of wedlock and hence indirectly secures her future. Bartels et al. (Citation2018) in their research indicate that poor families in Lebanon for instance, tend to perceive girl-child marriage as a way of securing the future of their daughters. Similarly, Singh (Citation2016) reveal that in India, girls from poor households are more likely to be married compared to girls from affluent households. Ferdousi (Citation2014) reveal that some parents in Bangladesh believe that their daughters will be better off and have a secured future if they are married off at an early age. While the preceding literature relates girl-child marriage to poverty, it also indicates an underlying perception of poor families; that girl-child marriage will protect the girl and her family from future suffering and stigma. Other literature suggest that some families and communities have reasons that are much more mundane: the girl child is an extra mouth to feed and a liability to household expenditure. Hence, marrying the girl child off means reducing the burden of care of the household (Karim et al., Citation2016). This is often the reason cited by families in contexts where early marriage is professed as the ideal course of action for young girls (Bajracharya & Amin, Citation2012). In parts of Ethiopia for instance, having more females in a household is thought to increase the likelihood of poverty (Ezra, Citation2001). Here, the perception of females as a liability is latent but apparent. Parsons et al. (Citation2015) found that poorer families frequently consider the early marriage of their daughters as a way to lessen the financial burden of dowry payments because the sum is lower for young girls than for older ones. The implication is that well to do families are able to marry daughters from other households for their sons compared to poorer families. Unarguably, the status of a family plays a role according to the United Nations Population Fund (‘UNFPA’), with families having income below the lower quintile more than likely to marry off their daughters than families with an income within the higher quintile. The young brides are sent to stay with their husbands’ families. This can be an incentive for poorer families not to invest in their daughters’ education, preferring to marry them off early to reduce their financial responsibility (Loaiza & Wong, Citation2012). This practice has future repercussions for the lives of young girls and women (McLeod et al., Citation2019). It promotes and perpetuates gender inequality since girls are viewed as a burden on their families (Alston et al., Citation2014).

Norms and Customs as Causes of Girl-Marriages. Some research points to local norms and customs that promote gender inequality as a cause of girl-child marriage (Ghosh, Citation2011). Ghosh (Citation2011, pp. 16–17) in a research on child marriage in India argues that ‘child marriage, being a part of our social tradition, continues to prevail due to a combination of traditional and modern factors. Our findings put the blame particularly on prevailing authoritarian and patriarchal social structure’. The literature that relates local norms and customs to the incidence of girl-child marriage also highlights the continuing struggle between local norms and constitutional or legal requirements about girl-child marriages (Arnett, Citation2017; Arokiasamy, Citation2017; Asomah, Citation2015; Ayton-Shenker, Citation1995). Sarfo et al. (Citation2022) in a review of the literature on girl-child marriage in Ghana explain that local Ghanaian constructions of gender, sexuality, and adolescence contribute to the persistence of girl-child marriages in Ghana. Boateng and Sottie (Citation2021) explain how the contention between local/community culture and the law plays out in the context of girl-child marriage in Ghana. They explain for instance, that the age of sexual consent in Ghana, 16, raises questions among local community leaders and family heads about whether a girl of 16 is better protected having sex in a marital relationship or outside. The authors explain how some indigenes and cultural custodians use this formal age of sexual consent to justify the safety of marriage for a sexually active girl. Again, the authors explain how the legal punishment for defilement (7 years of prison) compared to the legal punishment of marrying a child bride (1 year of prison) seems to diminish girl-child marriage as a lesser crime and indirectly emboldens some people to continue this practice. The argument is, though poverty is an important driver of the practice of child marriage, local customs, and norms are equally important and must be considered in any attempt to reduce and eliminate the incidence of child marriage (Sarfo et al., Citation2022).

Climate Change, Farming and Girl-Child Marriage. Farmers have a variety of adaptation strategies for mitigating climate change crises. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the severity of climate events, coupled with ignorance, make families resort to some life-threatening and risky informal adaptation or coping strategies, like girl-child marriage (McLeod et al., Citation2019). Households in disaster prone areas are impoverished and hence they often resort to marrying off their daughters early as a coping strategy in the event of food shortages and poverty (Ferdousi, Citation2014; Urama et al., Citation2019). Recent research like McLeod et al. (Citation2019) affirms that poor farming households who have been devastated by cyclones, flooding, and river erosion are increasingly likely to marry off their daughters at an early age as a way of adjusting to the challenges. Alston et al. (Citation2014) reports that girls in Bangladesh are forced into marriages because of climate events and poverty. McCarthy (Citation2020) projects that Malawi could have 1.5 million additional child brides as climate disruptions are increasing in the coming years. McCarthy (Citation2020) further argues that as natural disasters become more severe as a result of climate change, there may be an increased risk of child marriage in Bangladesh and areas affected by natural disasters. Research also proves that along with natural disaster, vulnerabilities like COVID-19 and child trafficking have also increased instances of child marriages in India (Ghosh, Citation2023). Irrespective of the reason, the implication of girl-child marriage goes beyond the girl and her family, to the society as a whole.

Consequences and Interventions for Girl-Child Marriage. Girl-child marriages have consequences for both the girls and the society at large (Efevbera et al., Citation2017). They result in the birth of unhealthy infants, baby and mother health problems, and high chances of maternal mortality among girl-brides (Efevbera et al., Citation2017; Raj, Citation2010). Girl-Child marriage denies the young brides their childhood, leisure, and freedom of playing with their friends and siblings (Naveed & Butt, Citation2020). Since childhood play and leisure have positive implications on socio-emotional development, girl-child marriage indirectly affects the emotional and mental health of the girls (Efevbera et al., Citation2017; Naveed & Butt, Citation2020). According to Rini Savitridina, Citation1997 girl-child marriage has underlying consequences that often manifest later in the life of girls, preventing girl brides from having a good future or family life. A study done by Lal (Citation2015) reveals pregnancy related health complications, STI infections and abuse as some of the consequences of girl-child marriage on the girls involved. Children born to girl-brides are more likely to suffer developmental challenges, including stunting (Efevbera et al., Citation2017). Fall et al. (Citation2015) also reveal that children boen to girl-brides are likely to perform poorly in school. Fall et al. (Citation2015, p. 366) argues that ‘children of young mothers in LMICs are disadvantaged at birth and in childhood nutrition and schooling. Efforts to prevent early childbearing should be strengthened’. The argument is, even though girl-marriages have negative implications for the girls involved, the effect goes beyond the girls to include the wellbeing of the children that will be born into such marriages. These consequences (for the girl bride and her children) make it important to put measures in place to reduce the incidence and potentially eliminate the incidence of girl-child marriages. According to Malhotra and Elnakib (Citation2021), cash or in-kind transfer to poorer families has proven to be an effective strategy for delaying child marriages. Cash transfer programs supports poor families to economically provide for their wards or motivate them to stay in school. Plesons et al. (Citation2021) also emphasizes the need for state investment in interventions that focuses directly on child marriage. Education, awareness creation and engagement with custodians of culture are all strategies that have been recommended as relevant for ending girl-child marriages (Plesons et al., Citation2021).

The above literature clearly demonstrates a link between climate change, poverty and girl-child marriages. In this research we ask if girl-child marriage is promoted as a social protection mechanism first, rather than as simply a response to climate induced poverty within the context of our study. We examine the complexities involved in the phenomenon of girl-child marriages through a social protection lens and wonder if the responses can offer any insight for the implementation of formal social protection strategies and for social work practice with vulnerable communities in general.

Methods

In this section, we present an overview of the approaches that we used in accessing information for this research. We begin by discussing the considerations that informed our choice of the area of study and continue to describe specific characteristics of this area. We proceed to discuss the design we used and the various decision making processes that led us to our sample, to the choice of data collection method and instrument and to our analytical procedure.

Area of study

Geographic and demographic Character

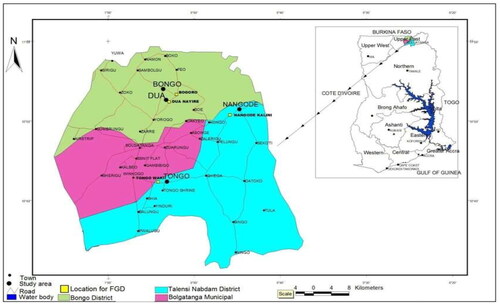

Geographically, the research was limited to Bongo District of the Upper East Region, Ghana (see ). The district is near the town of Bolgatanga, the Upper East Regional capital. It shares borders with Kassena-Nankana District in the west and south with Bolgatanga Municipal District. The district is multi-ethnic but has two major ethnic groups, Bossis and Gurunsis. There are two major languages spoken in the district: Bonni by the Bossis and Guruni spoken by the Gurunsis. The other ethnic groups are Kusasi, Nankani, Builsa, Kassena and Dargaba. There are three major religious groups in the district: the traditionalists, Muslims, and Christians, representing 44.0%, 7.2%, and 45.1%, respectively (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). The district has an age and sex ratio consisting of more young people between 15 and 64 years than 65 and above years. Notably, the age structure is narrower for the older age group while declining steadily in the following age groups. More males fall within the age group 0–14 years than their female counterparts, while females exceed their male counterparts in the economically productive age bracket of 15–65 years (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). 46% of the population between 12 years and above are married, with 1% either divorced or separated, and 11.6 are widowed. (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Overview of the Study area.

Source (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

Economic character

The local economy is made up of the agriculture, service, and industry sectors. Agriculture is the most dominant sector with 72.2%, consisting of crop farming, animal rearing and fishing. The industrial sector consists of 15.5%, while the service sector consists of 12.3% of the population. Some women are into shea butter making, dawadawa (Parkia biglobosa) processing, selling provisions and other handicraft production (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

On climate change and child-marriage

The Upper East region (where Bongo is located) has the highest child marriage rate in the country with 39.2 per cent of women aged 20–49 married before age 18. According to the World Food Program (WFP), (2012b), Bongo District is the most food insecure district in the Upper East region hence 20% of the households are food insecure. The area has one rainy season from May/June to September/October an average of 70 rain days a year. The annual rainfall is normally between 60 mm and 1,400mm. The rainfall is unpredictable and followed by extreme dry season from November to May with cold dry and dusty harmattan winds (Atitsogbey et al., Citation2018).

Ethnographers’ impression of Bongo

We spent the duration of data collection in Bongo. This was our first visit to the community. We experienced the physical environment as one of dry lands and dry winds. For the authors, the relative lack of vegetation and undergrowth was immediately obvious when we arrived in the community. Socially, we observed the community as a cohesive and socially integrative one, where people are not only aware of each other but also know each other. As such, we experienced our own otherness throughout the duration of data collection, with our presence and origin passed on by word of mouth from one community member to the other. While the households we visited were happy, they were equally lacking in basic amenities. Again, the farms lacked vegetation and adequate access to irrigation. We also observed the relative lack of presence of the state in the community; it felt as if the community members lived apart from the rest of the country and the restrictions and laws of the country. This may have implications on the extent to which state laws (on child marriage for instance), and state interventions (on climate change for instance) are enforced and applied within the study context. Some community members recounted to us how they watched from afar while the rest of the country went into lockdown during covid 19 and had to put on nose masks. They did not have to observe any of that and there was no one to enforce it. Within this context of climate change, poverty and early child marriage, this lack of presence of the state is important.

Research design

A qualitative case study design was used in this study. We considered a case study appropriate for this study because we believe that experiences and perceptions of climate change, farming practices and child marriage are better explored within specific contextual ethnic and traditional beliefs. Thus, the local farming community and their experiences and perceptions of child marriage is treated here as a unique case. Again, since Bongo is one of the districts with high rates of child marriages, we treated Bongo as a typical case. This design was appropriate since it allowed us to explore in-depth, the stories and attitudes of the context in relation to climate change, farming practices and early child marriage.

Selection of participants

The study employed a purposive sampling method. In this case, we targeted individuals or groups with knowledge or experience about child marriage in the area of study. Since the study uses Bongo Municipal District as a case study, the study selected male farmers, midwives, teachers, mothers, girls, and heads of government institutions in the district. We selected male farmers because they are heads of families and primarily part of the decision making process that decides when and how girls may be married. They also provided information on climate change risks over the past years and their influence on the household (especially in relation to the girl child). We considered midwives as important because they are the first point of contact in case of pre-natal care and any complication before and after birth. Teachers were selected because they had daily interaction with the young girls and could give reasons concerning attendance or drop out. Mothers were also chosen for the research because most of them would have experiential knowledge about this topic of discussion. Also, heads of government institutions like the social welfare director were selected because such institutions oversee the inhabitants’ wellbeing; hence all grievances about the welfare of all citizens, including the girl child, comes to his notice. The district director of agriculture was also selected because he oversees climate change-related issues, especially its growing effects on agriculture. Finally, the female respondents were included in the survey because they are the main target of the research and have lived through their experiences.

Data collection

Data collection took place in January 2021 at Bongo Municipal District, Upper East Region, Ghana. This study collected data using in-depth interviews and focus group discussions.

In-depth interviews

A semi-structured interview guide was used for the interview, with the interview proceeding recorded with the participants’ permission. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with specific professionals (teachers, midwives, government workers) who were deemed knowledgeable about the phenomenon under study. The semi-structured interview stimulated the conversation with the participants. This gave participants more choice and space to elaborate on their thoughts and viewpoints about the subject matter. More so, it ensures that key concepts are well understood. The in-depth interview lasted between 30 and 40 minutes in designated venues such as school compounds, district offices and the hospital settings. Participants were interviewed in both English and Twi languages, depending on which language they were comfortable with. Interviews with the social welfare director, queen mother and the agricultural director were conducted in English. In contrast, the other sessions with the teachers and the midwives were undertaken in the local Ghanaian language (Twi) since they were comfortable speaking in this dialect. provides an overview of the participants interviewed as part of this research.

Table 1. Interview participants.

Focus group discussion (FGD)

Focus group discussions were conducted with community members. Male farmers who were heads of households (and were also fathers in some cases) formed part of one discussion, mothers formed part of another discussion and mothers and young girls were part of another discussion. FGDs were used because we felt that group dynamics will allow us to get diverse but interesting experiences and perspectives about child marriage. This also enabled participants who could not freely express themselves during one-on-one interviews to do so. This instrument allowed us to acquire varied perceptions and further clarify issues, especially diverging responses. The various sessions were recorded with the participants’ permission. Each focus group discussion lasted for approximately 60 minutes, and the number of participants for each meeting ranged from 5 to 10 people. provides an overview of all participants who formed part of the various focus group discussions.

Table 2. Participants of FGD.

Ethical considerations

This research received ethical approval from the Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences.

All participants were given prior notice about the nature of the interview. The researcher thoroughly explained the key concepts, reasons for the interview, the type of information required and what it would be used for. The participants were informed about the duration of the interview and the FGD. All participants provided verbal consent to the interview before they participated. The researcher assured them of the anonymity of their responses and promised to send them copies of the transcript if requested.

Data analysis

Data collected from the interview, including notes taken from the FGD, were transcribed, manually coded, analysed, and verified. This was done by repeatedly listening to the recorded responses and often conferring with participants to ensure validity. Coding the data was done to ensure the systematic arrangement of emerging findings. Thematic analysis was adopted, allowing researchers to look across the transcripts, read thoroughly, and pinpoint and extract keywords that kept recurring throughout the transcript. The emerging keywords were then categorized under a theme for proper organization. The data were further analysed using an integrated approach, a mixture of the inductive and grounded theory methods.

The study infused a preliminary organizing framework from existing literature to increase precision while allowing participant experiences to drive analysis with frequent comparisons from earlier studies. Interpretations were ascribed to the identified themes while highlighting any similarities and differences in the data. Member-checking was used to clarify from participants if what was coded from the transcript was what they intended or said during the data collection exercise. This was used to lessen response bias and ambiguity and enhance the validity of the data available.

Results

Why do local farmers marry off their daughters at an early? We use responses from mainly focus groups and interviews to answer this question. Two main themes emerge and are explored in answering this question: that in the context of climate induced poverty, the girl child is liability until they are married; and that marriage serves as a form of social protection for the girl child and for their families.

The girl child is a liability before marriage but a resource after marriage

In the context of climate change and the challenges it presents to families, the girl child is considered as a liability to the family. Participants emphasize clearly that in the context of poverty, the girl-child is a ‘burden’ rather than a resource, unless or until she is married. In the explanation provided by the following participants, we realize that though they appreciate that marrying their daughters off early is not the best, they seem to agree that giving off the girl child is a better option:

Now they understand at least most of them understand that early marriage is not good, but the thing is that poverty is here I mean the harsh climate activities forces them to make such decisions. So, most families are happy to off-load you the girl, so they don’t have any option but to marry you off (Interview Participant 9).

For me as a farmer, I think it is difficult to take care of a girl child considering the climate change effects on our livelihood. The girl child has extra needed and responsibilities to be taken care of hence if per what is happening, I cannot do so, am speaking for myself here, I don’t mind releasing this responsibility to a man who is more capable of providing for her than I am (FGD Participant 16).

In this dry season we are all struggling to make a living now so if you have more mouths to feed that will be a big problem for you as a family head then you would have to sit down and try to come with a solution. Normally since there is no money and there are more mouths to feed the only solution would be to give one of your daughters for marriage to help reduce the burden on you as the breadwinner. I will not say we are happy to do this but sometimes the situation is unbearable (FGD Participant 16).

Of late the weather is not favorable we are not able to plant in time due to bad or less rain hence we are not able to fully provide for our families. So, I will say the situation compels us to marry off our daughters, I will not say we are happy to do so but if we can’t take care of her as a family and another family has the means to cater for her then marrying her off becomes a good option (FGD Participant 4).

Also, if you are a girl, you do not have money, food and you go to school starving. A man will meet and deceive you with one cedi. If he gives you the one cedi, he will have sex with you, and you might get pregnant. Your parents do not have money to take care of you or abort the pregnancy. Therefore, your parent will take you to the man to marry you. That is why we marry them early (FGD Participant 2).

The perception of risk of pregnancy to the girl-child seems to be a motivation for the families. Once again, though not explicitly indicated, the girl-child seems to be perceived only in terms of risk, burden or liability, risk/liability that is only eliminated through marriage. Another participant explains the girl-child in the context of climate-induced poverty as ‘an extra mouth to feed’. He explains:

During the lean season where we have sold or consumed all our farm produce and do not have any food to feed on, I will say this is a difficult period for most families here in our community. This season is where there is no rain for over four months, and this prevents us from farming hence we do not have money or any farm produce to support our families so if a man comes to ask for your daughters’ hand in marriage at this point you will be forced to accept the proposal so that you will have less mouths to feed in the family. (FGD Participant 5)

Early marriage as social protection for the girl-child and the family

In our discussion with community members, girl-child marriage is framed as a family protection mechanism rather than as a negative phenomenon for the girl-child. Through their narratives, participants reveal how girl-child marriage is used to (1) protect both the girl-child’s family of orientation from starvation and the embarrassment of unwanted pregnancy, while protecting the girl-child herself from risk; (2) Provide financial support for the education of the boy child; (3) Provide Capital for Family Businesses

Protecting the girl child and the family through early marriage

Participants discuss how the effects of climate change and the absence of a functioning formal adaptation program exposes the family to extreme poverty. In the context of this poverty, participants reveal that the family as a unit struggles to perform its basic function, including providing for the basic needs of the most vulnerable members of the family. There is an underlying assumption that while girls are particularly vulnerable to this lack of family support, they also offer an opportunity to protect the family from extreme poverty through marriage.

At first, when the climate used to be normal, we could sell our farm produce and cater for our girl child, but now that the weather has changed, if my girl child gets a boyfriend who is well to do, we will definitely give our girl child to him to marry so that through my girl child he can be providing a little basic thing in cash or kind for the survival of the family (FGD Participant 6).

This participant sees marriage of the girl-child clearly as a way of protecting the family from the negative consequences of climate change, an opportunity to help the girl’s family to fulfill its basic function of providing for the needs of its members. When the participant states: ‘…so that through my girl child he can be providing a little basic thing…for the survival of the family’, he is also re-emphasizing prevailing cultural and gendered assumptions of the man and husband (of the girl child) as the provider. Thus, through marriage, the girl child brings an extra provider to support the family’s resources in their bid for ‘survival’. Other participants shared similar sentiments

The reason for girl child marriage is that if there is no food in the house, you will find someone who has money and give your daughter. The man provides you with food, and you bring the food to the home and eat. On the days you do not have food to eat, you can go to the man’s house, and he will offer you food to eat (FGD Participant 2).

Young girls should be protected by their parents, but climate change does not make it possible. Families are unable to provide for their daughters. The truth of the matter is that we do not have the needed money to give the girl child the comfort and provisions she needs. At this point, we are sure of the fact that early marriage can help her and secure her future. Sometimes, the husbands even promise to educate them, so we believe this is a safe avenue for her. (FGD Participant 8).

Since this is a farming community, and we mostly rely on our farm produce to be able to cater for our children. We are greatly affected by the bad climate effects and hence believe that marrying our daughters off will help them since their husbands will now take full responsibility and help them through school even after childbirth (FGD Participant 10).

Two participants who had married early try to put this across forcefully and suggests that the girl child must see this as an obligation:

As a young girl sometimes, you can watch your parents when we are struck with any climate disaster so if you can help to reduce the burden by getting married so that your parents and siblings can live off your dowry then I will do it because I cannot watch my parents die in hunger when, I can be of help to them, because they provided for me when things were ok for them (FGD Participant 7).

Once you are a girl you can be made use to help the family, you know we are more, girls are vulnerable but useful, so they think that the girl is source of income so if they use you, they are not selling you out but by custom they can get something to feed others (Interview Participant 5).

As a father, I want to see my children give me grandchildren legitimately but with the issue of climate change affecting our farm produce and planting periods it becomes very important to secure the girl child’s life in this menace. This unfortunate consequence compels us to marry off our daughters and hope that they give birth to our grandchildren peacefully amidst all that is happening around us (FGD Participant 15).

Girl-child marriage as an educational policy for the boys

One thing that stood out in this conversation around social protection is how one participant framed girl child marriage as a strategy to secure the education and future of the boy-child. This particular participant, highlights the importance placed on the boy child and how the future wellbeing of the girl-child can be compromised for the advancement of their male siblings.:

…And again, if you have boys and girls who have completed JSS and there is no money to continue, you can give the girl to marry and take the cows and the things and sell them and use the money to take care of the boys in school (FGD Participant 20).

My family is a poor family and since our dowry system is in the form of cows and money. Since my sons are getting older and don’t have the means to fully sponsor their marriages, their younger sister will be given out for marriage and her dowry will be received and passed on to her brother to carry out his marriage process. (FGD Participant 25)

Girl child marriage provides Capital for business

Other respondents affirmed that girl-child marriage has financial gain or stability for the family. In any climate change disaster, most farmers are frustrated and do not know how they will feed their families. This compels most farmers to marry off their daughters and later use the proceeds to establish a business that can support or serve as a form of livelihood for the family. All participants acknowledged that proceeds from girl-child marriage could help support the family and start up a business. In one of the focus group discussions, one of the participants shared a personal example:

The recent pandemic coupled with the harsh climate effects on our livelihood, I must confess that the dowry from early marriage becomes very efficient capital which enables a family to venture into a small new business to help sustain the family and escape poverty… I personally used the dowry of my second daughter to start smock weaving business with my wife and this helps us to be able to survive when there is no rain. We are able to either farm or concentrate on the smock business when we enter the dry season, and this helps our family a lot (FGD Participant 23).

Summary of key findings

It appears from the foregoing discussion that within the context of our study and in the context of climate change, the girl-child is perceived more as a liability and an extra mouth to feed for poor farming families. There is a strong gender preference, with participants arguing that daughters are liabilities while sons are assets. Girl marriages are therefore constructed as a form of protection for the girl child and for the family of the girl child. For the girl child, marriage is seen as protecting her from hunger and from the stigma that comes with teenage pregnancy. For her family, the marriage provides extra source of food to feed the family, money to educate the boy-child, and money to begin an alternative source of business for the family’s continuous survival. Within the context of climate induced poverty then, girl marriages are seen as a form of informal adaptation strategy with the emphasis placed on the wellbeing of the girl’s family of orientation.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we set out to explore how climate change effects are linked to girl-child marriage and local perceptions of social protection. Our results reveal that local perceptions of the girl-child have implications on the continuing incidence of girl-child marriages. The findings of the interviews, and FGDs confirm that families see girl-child marriage as a protection mechanism, protecting the girl’s family from climate induced economic related challenges and the girl from similar as well as from the risk of pregnancy. Our findings reveal that the emphasis is not on the girl-child as an individual but on the family as a group. Hence, what is good for the family is assumed to be in the best interest of the girl-child. The individual needs of the girl child, the opinion of the girl child and the concerns of the girl child seem to be given very little emphasis in this process. Analysed within the context of study, marriage is considered as a joining together of two families; at the very least it signifies the pulling together of human and physical resources of two families for the wellbeing of all family members (Forkuor et al., Citation2019). As such marriage is perceived not as an individual affair with individual consequences (for the girl child), it is a family affair with group consequences (Nukunya, Citation2003). It is these group or family consequences that is emphasized rather than the consequences on the individual (in this case the girl child). Although this community norm stands in contradiction to the constitutional law in Ghana, it continues to be practiced within a context where state authority is less visible.

In a way, this reflects the continuing struggle between cultural norms and constitutional or legal requirements (Arnett, Citation2017; Arokiasamy, Citation2017; Asomah, Citation2015; Ayton-Shenker, Citation1995). Our findings demonstrate how the needs of specific customs (marry the girl child to protect the family and the girl from unwanted pregnancy) exist in contrast with the law (girl marriages are illegal in Ghana). Boateng and Sottie’s (Citation2021) explanation of this contention and how families and communities rationalize girl-child marriage is relevant in further analysing this continuing incidence of girl-child marriages. The authors explain how some indigenes and cultural custodians use the formal age of sexual consent in Ghana to justify the safety of marriage for a sexually active girl. Within a context of climate induced poverty, it is these cultural and communal customs and perceptions together with the seeming lack of enforcement/lack of presence of state authority that seem to perpetuate the incidence of child marriage. The relative lack of presence of state institutions and officials, as highlighted in the description of the study area, also contributes to the perpetuation of this customary norm over the constitutional law. One important contribution we emphasise from this study is the evidence we provide on the link between natal household poverty and girl-child marriage. Poverty is a key factor driving girl-child marriage, but data is lacking as most studies measure household wealth after girls have married, in their marital household, and then use it as a proxy for the natal household wealth. Our study provide insights on what ‘poverty’ or lack of resources actually means in practice and its implications for decision making about the wellbeing of the girl-child.

Another observation from the preceding is the fact that farming (the main form of economic activity and income) in this community is physical in nature, requiring the exertion of physical energy (Kansanga et al., Citation2019). Consequently, boys are often seen as a resource and girls perceived as a liability in relation to these physical intensive agricultural practices. Studies conducted in India also reveal that families seem to place different values on the girl child compared to the boy child and these different values often lead to preferential treatment for the boys and discriminatory practices towards girls (Singh, Citation2016). This presents significant challenges for the wellbeing of the girl-child. Nonetheless, this also points to potential agric-based solutions that could be explored to address the incidence of girl child marriages. Our contention is that if the girl-child can continue to be a productive member of the family through smart agriculture (Knickel, Ashkenazy, Chebach, & Parrot, Citation2017; Zakaria et al., Citation2020), families will be less likely to marry off their daughters (citing extra mouth to feed as a reason). Several authors (Hurst et al., Citation2021; Navarro et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2018) describe innovative, smart and less physically demanding agricultural techniques that could be adapted for use within the context of climate change. These agricultural practices that does not require the exertion of physical energy, will make girls more productive and reduce the perception of liability that families have of their girl-child. This will make the girl child a contributing member of the family and not be seen as only relevant through marriage.

The Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection are key actors in this regard. Girl child marriages are a social problem that falls within the scope of the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection and its numerous social workers in Ghana. While Ghanaian social work focuses largely on micro level practice and the implementation of cash based social welfare policies (Chitereka, Citation2009; Forkuor et al., 2018), we argue that the continuing practice of girl marriages create a need for social workers in Ghana to implement developmental approaches to practice (Chitereka, Citation2009), approaches that are preventive, rather than reactive. Several examples (Matthew et al., Citation2019; Tadesse, Citation2018; Tirivayi et al., Citation2016) exist of how agricultural innovations have been used to promote social protection and social welfare for vulnerable groups. In this study, we believe that adapting innovative and smart agricultural practices within our study context will contribute to reducing the incidence of girl marriages, especially for those families for whom the incidence is mainly for economic reasons rather than for cultural reasons. For this particular study, we recommend that social workers must actively work with professionals in Agric to come up with innovative and sustainable practices that maximizes the potential of the girl-child. In other words, one key role that social workers can play in the conversation on climate change and girl-marriages will be to become advocates of preventive approaches; the development of alternative forms of productive employment and sources of income that promotes the independence of the girl child and through that reduces the need for families to marry off their daughters. Ghanaian social workers must be active and preventive advocates in this regard.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge the assistance of the members of the community as well as the social welfare officers who dedicated their time and effort in providing relevant responses for this research.

Disclosure statement

The manuscript was presented orally (Power Point format) at the Development Studies Association Conference (DSA) at the university of Reading in June 2023. What appears on the website of the conference is the title and abstract of the paper. I confirm that this manuscript has not been published by the Conference or any other organization.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that some of the data that support the findings of this study are available within the article. The rest of the data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author, [L.A.A].

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Loretta Adowaa Asare

Loretta Adowaa Asare Loretta Adowaa Asare conceived of the research idea as part of her postgraduate thesis. In addition, she was primarily in charge of data collection and data analysis. She was the person who collected data by conducting interviews and organizing focus group discussions and was primarily responsible for analyzing the data that emerged from the field. She developed the first draft of the manuscript and has worked with John Boulard Forkuor to refine, review, and modify the manuscript to its present format. She approved the final version of the manuscript for submission and is capable and willing to clarify all issues and questions that may arise out of this publication.

John Boulard Forkuor

John Boulard Forkuor John Boulard Forkuor worked as the fieldwork supervisor for Loretta Adowaa Asare. He contributed by helping Loretta Adowaa Asare to refine the research idea and negotiate access to the field for Loretta Adowaa Asare. He has also provided a critical review of the initial manuscript drafted by Loretta and has worked with her to correct and refine the manuscript. He approves of the final version and is capable and willing to clarify all issues and questions that may arise out of this publication.

References

- Abass, R., Mensah, A., & Fosu-Mensah, B. (2018). The role of formal and informal institutions in smallholder agricultural adaptation: The case of Lawra and Nandom Districts, Ghana. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 26, 1–17.

- Alston, M., Whittenbury, K., Haynes, A., & Godden, N. (2014). Are climate challenges reinforcing child and forced marriage and dowry as adaptation strategies in the context of Bangladesh? Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.08.005

- Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., Fraser, E. D., & Stringer, L. C. (2013). Characterizing the nature of household vulnerability to climate variability: Empirical evidence from two regions of Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 15(4), 903–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-012-9418-9

- Arnett, R. C. (2017). Cultural relativism and cultural universalism. in the international encyclopedia of intercultural communication. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Arokiasamy, P. M. (2017). Cultural rights versus human rights: A critical survey of Trokosi tradition in wife of the gods. Research Journal of English Language and Literature, 5(1), 565–570. http://www.rjelal.com/5.1.17a/565-570%20P.MICHAEL%20AROKIASAMY.pdf

- Ashton, P. J. (2002). Avoiding conflicts over Africa’s water resources. Ambio, 31(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-31.3.236

- Asomah, J. Y. (2015). Cultural rights versus human rights: A critical analysis of the trokosi practice in Ghana and the role of civil society. African Human Rights Law Journal, 15(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2015/v15n1a6

- Asare, L. A., & Forkuor, J. B. (2023, June 28–30). The social consequences of climate change: A qualitative analysis of early girl child marriage as an informal adaptation strategy among rural communities in Northern Ghana. Crisis in the Anthropocene: Rethinking connection and agency for development (p. Paper 73202 of P32). University of Reading: Development Studies Association.

- Assan, E., Suvedi, M., Schmitt Olabisi, L., & Allen, A. (2018). Coping with and adapting to climate change: A gender perspective from smallholder farming in Ghana. Environments, 5(8), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5080086

- Atitsogbey, P., Steiner-Asiedu, M., Nti, C., & Ansong, R. (2018). The impact of climate change on household food security in the Bongo District of the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science, 52, 145–153.

- Ayton-Shenker, D. (1995). The challenge of human rights and cultural diversity: United Nations background note. United Nations Department of Public Information DPI/1627/HR.-1995.-March.

- Bajracharya, A., & Amin, S. (2012). Poverty, marriage timing, and transitions to adulthood in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning, 43(2), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00307.x

- Bartels, S. A., Michael, S., Roupetz, S., Garbern, S., Kilzar, L., Bergquist, H., Bakhache, N., Davison, C., & Bunting, A. (2018). Making sense of child, early and forced marriage among Syrian refugee girls: A mixed methods study in Lebanon. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000509. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000509

- Belay, A., Recha, J. W., Woldeamanuel, T., & Morton, J. F. (2017). Smallholder farmers’ adaptation to climate change and determinants of their adaptation decisions in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0100-1

- Belloumi, M. (2014). Investigating the impact of climate change on agricultural production in Eastern and Southern African Countries. AGRODEP Working Paper 0003. International Food Policy Research Institute. http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/128227

- Boateng, A., & Sottie, C. A. (2021). Harmful cultural practices against women and girls in Ghana: Implications for human rights and social work. In V. Sewpaul, L. Kreitzer, & T. Raniga (Eds), The tensions between culture and human rights: Emancipatory social work and afrocentricity in a global world (vol. 5, pp. 105–124). University of Calgary Press.

- Chitereka, C. (2009). Social work in a developing continent: The case of Africa. Advances in Social Work, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.18060/223

- Cobbinah, P. B., & Anane, G. K. (2016). Climate change adaptation in rural Ghana: Indigenous perceptions and strategies. Climate and Development, 8(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1034228

- De Wit, M., & Jacek, S. (2006). Changes in surface water supply across Africa with predicted climate change. Science, 311(5769), 1917–1921. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1119929

- Ezra, M. (2001). Demographic responses to environmental stress in the drought‐and famine‐prone areas of northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(4), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.226

- Efevbera, Y., Bhabha, J., Farmer, P. E., & Fink, G. (2017). Girl child marriage as a risk factor for early childhood development and stunting. Social Science & Medicine, 185, 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.027

- Fall, C. H. D., Sachdev, H. S., Osmond, C., Restrepo-Mendez, M. C., Victora, C., Martorell, R., Stein, A. D., Sinha, S., Tandon, N., Adair, L., Bas, I., Norris, S., & Richter, L. M. (2015). Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: A prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS collaboration). The Lancet. Global Health, 3(7), e366–e377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8

- Ferdousi, N. (2014). Child marriage in Bangladesh: Socio-legal analysis. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 6(1), 1–7.

- Few, R., Ahern, M., Matthies, F., & Kovats, S. (2004). Floods, health and climate change: A strategic review. Tyndall Centre Working Paper, 63 http://tyndall.ac.uk/sites/default/files/wp63.pdf.

- Fischer, R., Santiveri, F., & Vidal, I. (2002). Crop rotation, tillage and crop residue management for wheat and maize in the sub-humid tropical highlands: Wheat and legume performance. Field Crops Research, 79(2-3), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00157-0

- Forkuor, J. B., Ofori-Dua, K., Forkuor, D., & Obeng, B. (2019). Culturally sensitive social work practice: Lessons from social work practitioners and educators in Ghana. Qualitative Social Work, 18(5), 852–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325018766712

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2012). Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey with an enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker 2011. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR262/FR262.pdf.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 Population and Housing Census: Bongo District. https://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010_District_Report/Upper%20East/Bongo.pdf.

- Ghosh, B. (2011). Child marriage, community, and adolescent girls: The salience of tradition and modernity in the Malda District of West Bengal. Sociological Bulletin, 60(2), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022920110206

- Ghosh, B. (2023). Vulnerability and Trafficking of Children amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. In S. Reddy & J. Rashid (Eds), Child protection and rights in India (pp. 318–339). Anthropos Books.

- Howden, S. M., Soussana, J.-F., Tubiello, F. N., Chhetri, N., Dunlop, M., & Meinke, H. (2007). Adapting agriculture to climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(50), 19691–19696. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701890104

- Hurst, W., Mendoza, F. R., & Tekinerdogan, B. (2021). Augmented reality in precision farming: Concepts and applications. Smart Cities, 4(4), 1454–1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4040077

- Ijeoma, O. C., Uwakwe, J. O., & Paul, N. (2013). Education an antidote against early marriage for the girl-child. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3(5), 73–78. https://www.mcser.org/journal/index.php/jesr/article/view/641 https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n5p73

- Karim, N., Greene, M., & Picard, M. (2016). The cultural context of child marriage in Nepal and Bangladesh: Findings from CARE’s tipping point project community participatory analysis: Research report. CARE.

- Knickel, K., Ashkenazy, A., Chebach, T. C., & Parrot, N. (2017). Agricultural modernization and sustainable agriculture: Contradictions and complementarities. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 15(5), 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1373464

- Kansanga, M., Andersen, P., Kpienbaareh, D., Mason-Renton, S., Atuoye, K., Sano, Y., Antabe, R., & Luginaah, I. (2019). Traditional agriculture in transition: Examining the impacts of agricultural modernization on smallholder farming in Ghana under the new Green Revolution. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2018.1491429

- Kotir, J. H. (2011). Climate change and variability in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of current and future trends and impacts on agriculture and food security. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 13(3), 587–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-010-9278-0

- Kumasi, T. C., Antwi-Agyei, P., & Obiri-Danso, K. (2019). Small-holder farmers’ climate change adaptation practices in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 21(2), 745–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-0062-2

- Lal, B. S. (2015). Child marriage in India: Factors and problems. International Journal of Science and Research, 4(4), 2993–2998.

- Loaiza, E., & Wong, S. (2012). Marrying too young. End child marriage. New York: United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf.

- Malhotra, A., & Elnakib, S. (2021). 20 years of the evidence base on what works to prevent child marriage: A systematic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 847–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.017

- Mashizha, T. M., Ncube, C., Dzvimbo, M. A., & Monga, M. (2017). Examining the impact of climate change on rural livelihoods and food security: Evidence from Sanyati District in Mashonaland West. Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 3(2), 56–68.

- Matthew, O. A., Osabohien, R., Ogunlusi, T. O., & Edafe, O. (2019). Agriculture and social protection for poverty reduction in ECOWAS. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 6(1), 1682107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1682107

- McLeod, C., Barr, H., & Rall, K. (2019). Does climate change increase the risk of child marriage: A look at what we know-and what we don’t-with lessons from Bangladesh and Mozambique. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 38(1), 96–145. https://doi.org/10.7916/cjgl.v38i1.4604

- Mugambiwa, S. S. (2018). Adaptation measures to sustain indigenous practices and the use of indigenous knowledge systems to adapt to climate change in Mutoko rural district of Zimbabwe. Jamba, 10(1), 388. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v10i1.388

- McCarthy, J. (2020, March 5). Why climate change disproportionately affects women. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/how-climate-change-affects-women/.

- McCarl, B. A. (2010). Analysis of climate change implications for agriculture and forestry: An interdisciplinary effort. Climatic Change, 100(1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9833-6

- Ndamani, F., & Watanabe, T. (2015). Farmers’ perceptions about adaptation practices to climate change and barriers to adaptation: A micro-level study in Ghana. Water, 7(12), 4593–4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094593

- Nukunya, G. K. (2003). Tradition and change in Ghana: An introduction to sociology. Ghana Universities Press.

- Navarro, E., Costa, N., & Pereira, A. (2020). A systematic review of IoT solutions for smart farming. Sensors, 20(15), 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20154231

- Naveed, S., & Butt, D. K. M. (2020). Causes and consequences of child marriages in South Asia: Pakistan’s perspective. South Asian Studies, 30(2), 161–175.

- Parsons, J., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., Petroni, S., Sexton, M., & Wodon, Q. (2015). Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2015.1075757

- Plesons, M., Travers, E., Malhotra, A., Finnie, A., Maksud, N., Chalasani, S., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2021). Updated research gaps on ending child marriage and supporting married girls for 2020–2030. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01176-x

- Raj, A. (2010). When the mother is a child: The impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95(11), 931–935. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.178707

- Sarfo, E. A., Yendork, J. S., & Naidoo, A. V. (2022). Understanding child marriage in Ghana: The constructions of gender and sexuality and implications for married girls. Child Care in Practice, 28(2), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2019.1701411

- Savitridina, R. (1997). Determinants and consequences of early marriage in Java, Indonesia. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 12(2), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.18356/734662b8-en

- Singh, V. (2016). ‘Factors shaping trajectories to child and early marriage: Evidence from Young Lives in India’. Young Lives working paper 149. Retrieved 22nd January 2024. https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrated/YL-WP149-Trajectories%20to%20early%20Marriage.pdf.

- Tadesse, G. (2018). Agriculture and social protection: The experience of Ethiopia’s productive safety net program. Boosting growth to end hunger by, 2025, 2017–2018. In ReSAKSS Annual Trends and Outlook Report, chapter 3, pages 16–33, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). http://cdm15738.contentdm.oclc.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/132852/filename/133073.pd.

- Tirivayi, N., Knowles, M., & Davis, B. (2016). The interaction between social protection and agriculture: A review of evidence. Global Food Security, 10, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2016.08.004

- Taylor, M. (2018). Climate-smart agriculture: What is it good for? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(1), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1312355

- UNICEF. (2023). Child Marriage. Retrieved 26 January 2024 from https://www.unicef.org/protection/child-marriage#:∼:text=Child%20marriage%20refers%20to%20any,in%20childhood%20across%20the%20globe.

- Urama, N. E., Eboh, E. C., & Onyekuru, A. (2019). Impact of extreme climate events on poverty in Nigeria: A case of the 2012 flood. Climate and Development, 11(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1372267

- Zakaria, A., Azumah, S. B., Appiah-Twumasi, M., & Dagunga, G. (2020). Adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices among farm households in Ghana: The role of farmer participation in training programmes. Technology in Society, 63, 101338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101338