Abstract

Evidence from literature shows that wellbeing has been considerably picking the drift for a decade as a path to find oneself in a chaotic world. Complimentary to this, the tourism industry is invested in tailoring its services and paying attention to tourist wellbeing. Therefore, this study pioneers in reviewing the plethora of research that amplifies tourist wellbeing and attempts to redefine its conceptualization in addition to underscoring the need for its practical application. We strengthened the methodology by using the SMART approach to define the literature’s parameters, PRISMA for the purpose of data transparency and R bibliometric tools for a comprehensive analysis of data. The inclusion of records at every stage was presented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, 2020. N = 279 papers were extracted from Scopus for the final synthesis using Bibliometric tools to map the prospects of the domain. Findings highlight the need to broaden the horizons of tourist wellbeing in concept and practice to make the industry more sustainable and resilient. The responsibility to rebuild tourist-wellbeing vests on stakeholders and scholars by underscoring the potential of the contemporary tourism industry. This study lays out a foundational dimension for future research in the area of tourist wellbeing.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Wellbeing, happiness, health, and sustainability are a few of the concepts that have had to and are still undergoing intense scrutiny from various stakeholders ranging from policy makers to service providers. The increase of infectious diseases and pandemics, loss of natural resources and ecosystems, and the slow decay of healthy social relationships is causing serious doubts on whether we will ever achieve a true sense of wellbeing in and around us, be it today, tomorrow, or anytime in the future. As scepticism paves the way for this looming fear, academicians and researchers have been investing time and energy to amplify the need for wellbeing and introducing the concept in varying domains across the world for the purpose of sustainable development. In the tourism context, promotion of wellbeing has extensively grown as an interest area among service providers and policy makers for a variety of causes as there seems to be a visible worry about the physical, psychological, and societal health of tourists. Destinations are offering intriguing avenues like digital-free destinations for tourists to enjoy their vacations by disconnecting from the world and experience tourism that leads to enhancing their wellbeing (Hassan et al., Citation2022; Pyke et al., Citation2016).

Filep (Citation2016) underscores traveling as the explanation of a person’s needs to link with pleasure and enjoyable things, while at the same time being out of touch with saturated stress from the outside world. To cater to this demand, the tourism industry has successfully introduced wellbeing as an advanced perspective to the speedily growing segment of today’s booming travel industry to improve the overall strength and well-being through mindful pleasure that restores a tourist’s physical and mental balance (Farkić et al., Citation2020; Farkić & Taylor, Citation2019) while contributing greatly in improving people’s quality of life. Tourism also plays a significant role in enhancing social and economic benefits, promoting economic growth and development, reducing poverty, providing livelihoods, and gaining peace (Kim et al., Citation2015; Sofronov, Citation2018) and all of this leads to wellbeing – directly or indirectly. Areas related to ecotourism, adventure tourism, and cruise tourism are becoming increasingly popular among tourists who seek to find solace in the arms of relaxing tour practices. It has been observed that tourists who regularly visit natural tourist spots have experienced higher levels of rejuvenating wellbeing compared to those who did not (Garcês et al., Citation2018).

The significance of wellbeing has been strengthening drastically as individuals are consciously making choices from the diversely innovative dimensions in the marketplace among which tourism is one. As a consumer in the tourism industry, one is driven to choose wellbeing as traveling is viewed as an important force that positively affects physical and mental wellbeing. The evidential resilience and growth of wellbeing through tourism encouraged us to shed light on how the tourism industry can tap its vast potential to create a sustainable footprint. The concept of wellbeing is widely practiced in the wellness sector of the tourism industry i.e. wellness resorts and spa enterprises. This concentration, although well accepted, carries the potential to make a remarkable impact on all other facets of the travel and tourism industry. Engaging and interacting with the local community, connecting with the place through its art, culture, and cuisine, mindfully spending time in nature, appreciating the beauty of a place, going the extra mile to experience thrill and adrenaline through adventure challenges (Dsouza et al., Citation2022) are a tiny of spec of activities through which tourists can experience wellbeing.

Considering the scope for growth and plethora of research in the area, our study offers a comprehensive background of the tourism industry and its linkages to wellbeing through a bibliometric analysis using SMART approach. We aim to provide a brief review of the existing research on tourist wellbeing while also examining the effectiveness of the tourism sector in enhancing economic and social wellbeing. With these aspects in mind, we developed two structural research questions (RQ) to map the direction of future research under the umbrella of wellbeing through tourism.

RQ1: What is the trajectory of research that has studied the relevance of wellbeing in the tourism industry?

RQ2: What are the future directions for research that will help policy makers and service providers to offer improved tourism experiences to promote tourist wellbeing?

2. Literature review

2.1. Tourism – a nexus to improve tourist wellbeing

Albeit the fact that tourism research is overwhelmingly substantial, terms like mindfulness, wellbeing and wellness are gaining rapid impetus in the realm of tourism since individuals have become more demanding to experience wellbeing and escapism through tourism (Aydin & Ömüriş, Citation2020; Dwyer, Citation2023; Pope, 2018). Directly or indirectly, tourism activities have an impact on the metak health of tourists (Buckley, Citation2022). This builds a sturdy bridge between individual’s wellbeing and transformative travel which further links it to the heightened topic of sustainable tourism. Sustainability is not limited to ‘environment’ alone but is also linked to other world resources like people’s health and prosperity. With the growth of the commercial aspects in the tourism industry, stakeholders are paying significant attention to make it sustainable for the world and all the stakeholders involved especially tourists. Tourism is slowly shifting focus on matters associated to health and wellbeing and this speaks volumes about the changing approach of various stakeholders towards promoting tourism. Many studies have shown that tourism rejuvenates the mind-body and empowers us to relink with our past in exceptionally coordinated ways. In addition to being eluded from upsetting or ordinary schedules, tourism has proved to push individuals to recall and engage in their memories and take a step forward to improve social connections (Hanna et al., Citation2019).

Tourism is an ideal medium for promoting wellbeing since tourists participate in recreational activities while on vacation. Wellbeing is studied extensively in the fields of Health, Wellness, Eco, Nature, Adventure, and Medical tourism (Mertika et al., Citation2020). The goal of Health tourism – a hybrid type of tourism that combines medicinal and recreational elements (Dunets et al., Citation2020) – is to attract visitors by providing healthcare services and facilities in addition to other attractions. These health care services may include medical examinations by competent doctors as well as acupuncture and specialized medical treatments for a variety of diseases. On a slightly lower tone of medical application, wellness tourism helps tourists to improve their physical and psychological well-being through activities that reduce stress through relaxation and healing that further assists in physical recovery (Dutt & Selstad, Citation2021).

Furthermore, ecotourism is one such dimension that uses animals and natural resources in a non-consumptive manner and contributes to the visited region through work or financial means, intending to directly benefit the site’s conservation and the economic well-being of residents. From the tourists’ point of view, it has been posited that outdoor activities have a good influence on the physical, intellectual, social, and, spiritual health of tourists that further strengthens the link between traveling in nature and wellbeing. Additionally, adventure trips like scuba diving and snorkeling, whitewater rafting and kayaking, skiing and snowboarding, hiking and biking, climbing and mountaineering, sailing, and sea kayaking has proved to help people to sleep better at night, feel better about themselves, improve their bone and joint strength and also improve their immune system (physical dimension of wellbeing) (Buckley, Citation2021; Lötter & Welthagen, Citation2019). Tourism is so impactful in ensuring tourists’ wellbeing in these areas that it shows how much potential tourism has, to encourage healthy lives and well-being in both local communities and in the context of our study – tourists.

2.2. Wellbeing and tourism – a typology

As we strive to strengthen the relationship between wellbeing and tourism, we first look at both the concepts separately and then work to bring them together. Psychology, economics, medicine, and interdisciplinary research has made attempts to keep ‘wellbeing’ as the center of talks, but little consensus is available on its definition. Vada et al. (Citation2019) defines wellbeing with the help of two concepts. The first is hedonic well-being, that is defined in terms of short-term intense delight and pleasure, and the second is eudaimonic well-being, that is defined in terms of personal growth and development. Bringing the concept of wellbeing into the foray of tourism, researchers have advocated that vacationing provides visitors with unforgettable experiences, profound levels of enjoyment, and overall contentment with their lives. Consequentially, tourists’ experiences have a beneficial impact on their wellbeing and a variety of their life’s elements such as family, social relationships, leisure, culture, and much more. As a result, tourism may be viewed as having a long-term positive impact on one’s wellbeing (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013).

The hedonic view is based on the propagation of 4th-century Greek philosopher Aristippus who regarded that the purpose of life is to experience as much pleasure as possible and the avoidance of pain for happiness is the totality of one’s hedonic moments. For example, Voigt et al. (Citation2011) suggest that in the context of wellness tourism, more hedonic wellbeing experiences might take place in a beauty spa whereas more wellbeing experiences can be gained from spiritual retreats. There have been correlations between spending time outside and people’s subjective wellbeing, which is directly linked to people’s regular happiness and anxiety reduction (Pomfret, Citation2021). In particular, brief nature-breaks have the power to ‘fix’ the body, spirit, and mind, and offer compensation for people’s alienated, fast-paced lives (Brymer et al., Citation2010, Buckley, Citation2022).

Eudaimonic wellbeing, on the other, is related to personal growth, self-fulfilment, self-development, full engagement, and ultimate overall performance of meaningful actions (Pomfret, Citation2021, Filep et al., Citation2022). Travel has the potential to offer spiritual, cognitive, physical, and psychological experiences that can bring small or big changes in an individual’s perception of different aspects in and around a person. New and authentic tourism experiences can make life altering changes in one’s life that offers a journey to growth, development, and novel awareness (Bryce et al., Citation2015). These services can be curated through tourist participation models where the skills and knowledge of tourists can help in strategic designing of tourism services by taking their opinions, suggestions, feedback, and ideas through active interaction (Gupta & Priyanka, Citation2023). Moreover, these experiences can be that of learning, for instance, ecotourism in its most organic form can teach the tourist to be a ‘responsible tourist’, even so, ‘responsible individual’ and can divulge in acts of conserving the environment and improve self-wellbeing and that of the society (Bryce et al., Citation2015).

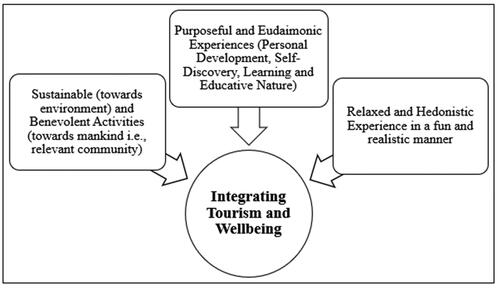

The Tourist Wellbeing Framework displayed in is developed by assimilating existing definitions, themes, and frameworks retrieved from current literature focused on wellbeing in various dimensions. These aspects are mapped to the literature focused on tourism, thus underscoring the potential of tourism to contribute and create more than just an experience. Before dwelling into the practical application of ‘wellbeing’ in the tourism context, it is fundamental to define tourist wellbeing. Considering this, an assimilation of existing literature led us to develop a comprehensive definition of tourist wellbeing as, ‘Immersing in purposeful, educational, and relaxed experiences that benefits the mind, body, community, and the environment. These experiences are provided through a strategic integration of tourism services that revolve around realistic, fun, benevolent, and pleasant activities’.

2.3. Identifying research gaps

Research around the productive of tourism on health, wellness, adventure is available in abundance as interest in these areas have been piqued since over a decade. On the other hand, research that studies the role of wellbeing in the tourism industry has seen a significant increase in the recent years. Complimentary to this, trends in the tourism industry shows that tourists look for experiential tourism in destinations that offer more than just the tourism product (Breiby et al., Citation2020; He et al., Citation2023; Pyke et al., Citation2016). They seek destinations that will help them deviate their minds from their otherwise chaotic life. Thus, strengthening the link between wellbeing and tourism is called for by authors by reckoning extensive research that proves the link between the sustainability aspects of tourism and wellbeing. Through this, it can be observed that tourists experience not just momentary, but long-lasting impacts on their daily wellbeing at the most optimum level (Smith & Diekmann, Citation2017) that benefits the community, ecosystem, and tourists.

The review, analysis and results contribute towards understanding and developing a wide range of perception around the concept of wellbeing through tourism. The current stream of literature offers an individualistic view of these concepts from different verticals of the tourism industry. Therefore, the holistic assessment of current literature acts as a guide for future researchers to conduct in-depth research in the suggested areas and help policy makers curate strategic policies to promote wellbeing through tourism services. The capabilities of the tourism sector to promote community, destination, and tourist wellbeing is delved into in detail. Bibliometric studies conducted till date are ambiguous in nature. Therefore, this study offers a clear and recent overview of the studies conducted on tourist wellbeing while also providing a detailed future research agenda in this context.

3. Materials and methods

The SMART approach is used to explore the structures and components of ‘wellbeing through tourism’ through a comprehensive review. The goal is to establish a thorough foundation for future research by looking at current literature in the same area. Several authors have embraced this approach for conducting reviews and analysing trends. For instance, authors Angelstam et al. (Citation2013) applied the SMART approach to ‘analyse the direct and indirect indicators related to ecological sustainability in the Swedish FSC standards’. Tantri & Shetty (Citation2023) investigate the ‘research landscape of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in the workplace as a breakthrough in occupational stress’ through the SMART approach.

A brief overview on SMART is provided in a comprehensive manner. SMART stands for Specific (‘What exactly are we going to do for whom?’), Measurable (‘Is it quantifiable and can WE measure it?’), Attainable/Achievable (‘Can we get it done in the proposed time frame with the resources and support we have available?’), Relevant (‘Will this objective have an effect on the desired goal or strategy?’) and Time bound (‘When will this objective be accomplished?’). We begin with answering each question definitively. First, it needs to be stated that this study is a scientific review of existing literature in the area of ‘tourist wellbeing’ using Bibliometric tools. Therefore, the questions arising through SMART will be answered keeping this fact in mind.

‘What exactly are we going to do for whom?’. First, the primary goal of this paper is to underscore the trajectory of academic research that has strived to understand the concept, practice, and implication of various kinds of wellbeing through tourism practices. We specifically aim to understand this from the point of view of tourists who seek to experience wellbeing through tourism. Therefore, this paper keeps tourists in its nexus and works towards the various spokes of wellbeing while encouraging service providers and policy makers to promote the practice of wellbeing in various tourism services. Second, as the study is conducted through bibliometric analysis, the data is scientifically measurable by using R Studio – a software that is extensively used for bibliometric analysis. Third, the study specifies the time frame within which the literature is considered for robust, recent, and relevant research studies. Subsequently, we also mention the timeline during which the study was conducted using valid resources. Fourth, we conduct the study to not only provide a holistic review or revitalize the definition of tourist wellbeing, but also to offer a range of implications to further the direction of research in this area. And finally, we aim to achieve the objective within the specific time frame to ensure that the results reflect relevance and robustness for future research.

‘Is it quantifiable and can WE measure it?’; ‘Can we get it done in the proposed time frame with the resources and support we have available?’; ‘Will this objective have an effect on the desired goal or strategy?’; ‘When will this objective be accomplished?’. The answer to these questions is provided in detail through an elaboration on the methodology of our review.

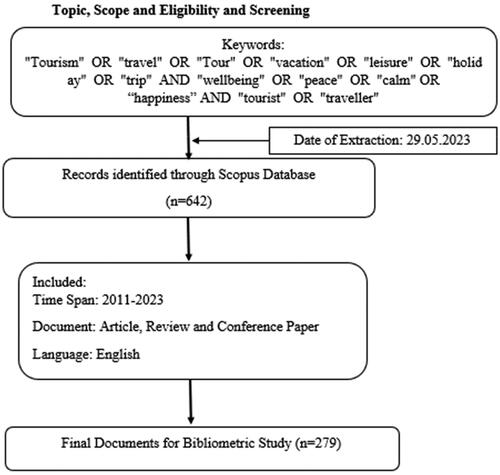

It has been comprehended that Bibliometric analysis is becoming increasingly relevant in various disciplines of social science. This study commenced with a search on ‘Scopus’ using a string of keywords relevant to our potential study. SCOPUS is a freely accessible database available online, consisting of publications in various scientific domains encouraging global distribution of knowledge, information, and data. As we looked for data only from Scopus, that makes it a limitation. Nevertheless, we found that this database encompasses a larger number of data compared to other databases in terms of articles as well as citations for our area of study. Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used wherever required between the keywords in the search box of the database. Concerning the technique of visualization, distance-based, graph-based, or time-based tools (Rodrigues et al., Citation2014) are used for interpreting the bibliometric networks through the Biblioshiny software. For the purpose loading and exporting data in an efficient manner, Biblioshiny – an extensive and extravagant set of techniques – was applied for further data synthesis (Moral-Muñoz et al., Citation2020). In the current study, the graphic add-on ‘biblioshiny’ for the package ‘bibliometrix’ in R. Studio, developed by Italian scholar Massimo Aria, was run for a bibliometric analysis to segment the body of knowledge (Burda et al., Citation2020). Bibliometrix and Biblioshiny, a free and open-source package, can fulfil the whole literature analysis and data flow process that helps the researcher in avoiding tedious and unnecessary operations (Xie et al., Citation2020). This enhances work efficiency and reduces the intensity and chances of errors.

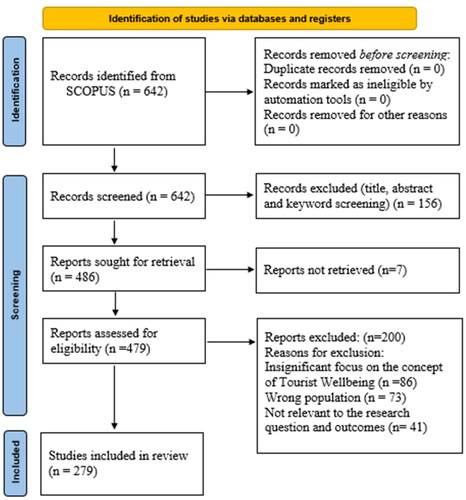

To make sure that the review process was transparent, inclusion of records at every stage was presented using a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 (BMJ 2021;372:n71) chart along with clear reasons for inclusion and exclusion of the reports as shown in and . Further on, these results were filtered based on inclusion-exclusion criteria whereby documents that did not meet the criteria i.e. not under the purview of ‘tourist wellbeing through tourism’ were excluded while documents available in ‘English’ and those that were ‘articles’, ‘reviews’ and ‘conference papers’ were included. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in and .

Scopus allows the export of up to 2000 data at a time, whereas Web of Science (WoS), allows a maximum of 500 data that can be exported at a time. The Scopus database offers more social science research coverage than Web of Science. When we looked for literature evidence in the area of ‘tourism’ AND ‘wellbeing’, the search generated limited documents as compared to Scopus search for the same keywords. Thus, the results of our search, relevance of the document and the broad range of research metrics are the reasons for opting to analyse literature from the Scopus database. Apart from this, Scopus also makes way for scholars to export data in different file formats such as CSV, RIS, BibTeX, Plain Text formats, etc. In this study, data was exported in the format of BibTex as it is the only format allowed for importing data from Scopus to biblioshiny to run a bibliometrix analysis (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017).

3.1. Data synthesis

A total of n = 642 articles reflected in the database after applying the search string of the aforementioned keywords. Further on, while 156 documents were removed during title, abstract and keyword screening, 7 could not be retrieved thus bringing the documents to 479. During the full text screening, 86 documents were excluded that there was negligible focus on the concept of tourist wellbeing, 73 documents were excluded as the population differed from that of our study context and 41 papers were excluded as they were relevant to our research question and/or outcomes. For the final review, we included 279 papers that comprised of articles in English that included articles, review papers, and conference papers. The final data was exported to Biblioshiny for further analysis.

3.2. Bibliometric analysis

3.2.1. Word cloud

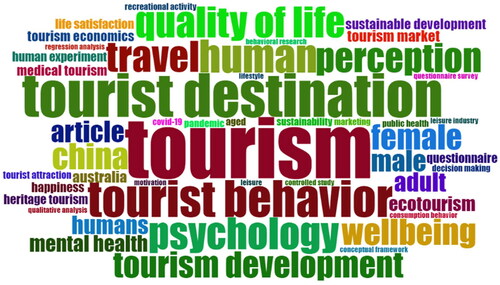

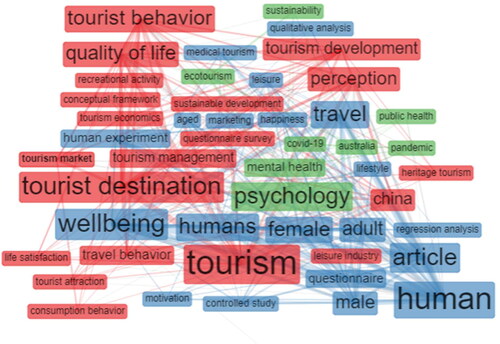

represents the frequency of keywords that appear in studies that fall under the context of Tourist Wellbeing. The Word Cloud in is a description of the words that often appear in papers researched on the theme of assessing tourist wellbeing through tourism. The figure cloud displays words that differ in size and reflects the frequency in which the keywords appear in various papers. In terms of placement, the word cloud tends to be random, but the dominating words are placed in the middle so that they are more visible with their large size. represents the frequency of words and is aligned with . It can be interpreted that most studies conducted in the area of tourism has paid limited attention to wellbeing while more focus is paid to tourism development, tourist destination and perception. Geographically, China is visible in the horizon as more studies in this context is concentrated in this country while United Kingdom and United Arab Emirates are visible but negligible. This calls for more in-depth research in more countries across the world especially those that offer tourism products and services extensively.

Table 1. Thematic map.

Table 2. Word cloud.

3.2.2. Co-occurrence network

Subsequently, we looked at the keyword co-occurrence network to acquire a better understanding of tourism trends. It shows how keywords in literature are linked. As a result, our findings show that in addition to recognizing common terms, it also shows the relationship between them, as revealed in a word cloud. Some keywords, appear to have a bigger impact on a network. A cluster is represented by a colour, and in this figure, there are six clusters. In this figure red cluster, the words ‘wellbeing’, ‘tourist destination’, ‘tourism’, ‘tourism management’ and ‘tourism development’ are prominent areas of study.

A detailed analysis of these keywords based on their colour codes, as shown in , reveals that a larger keyword indicated by their width is cohesively linked to other smaller keywords and a broader line denotes a strong relationship between those terms; the thinner line denotes a weak relationship and there is no association between keywords if there are no connecting lines. ‘Wellbeing’, for example, is linked to ‘health’, ‘happiness’, ‘physical activity’, and ‘public health’. The keyword ‘Tourism’, on the other hand, is intimately linked to ‘quality of life’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘wellness’, and ‘tourism’. Although the links exist, they are visibly weak and need for consideration from authors.

3.2.3. Three field plot

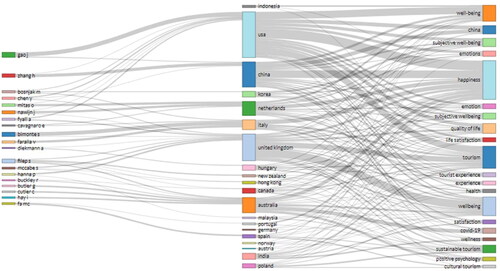

reflects 3 fields with authors in the left field, countries in the middle and keywords in the right field. These 3 elements are connected with gray plot lines based on their relation to one another. China, USA, UK, and Australia are the largest producers of scientific papers that majorly talk about tourist wellbeing through various forms of tourism. It is evident that Gao J is the leading author in this area and has considerable articles that focus on tourist wellbeing in the geographical underpinning of China. Through a manual search, we also found that Ralf Buckley has been contributing evidential research to the area of tourism wellbeing in recent times. Multiple authors have contributed to the growth of academic papers that revolve around tourist wellbeing with more focus on countries like USA, UK, and Australia. It can be posited that these countries among others are, a. paying more attention to tourist wellbeing, b. experiencing growth and development in terms of tourism and c. focusing on improving the destination image as well as quality of life of the tourists.

3.2.4. Thematic map

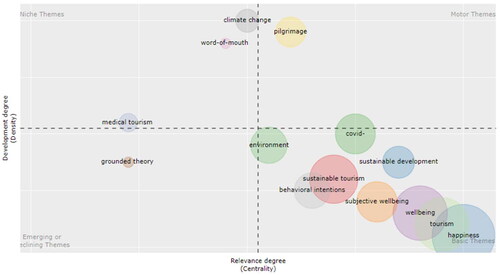

Thematic map is an intuitive plot through which we can analyze themes according to the quadrant in which they are placed while the upper-right quadrant reflects motor-themes, the lower-right quadrant reflects basic themes. Subsequently, the lower-left quadrant displays the emerging or disappearing themes and the upper-left quadrant shows niche themes. The map brings out the keywords to underscore the most discussed topics during the period of the study. The relevant words used in the collection of papers that were the subject of the study were also counted, with numerous words having occurrences ranging from 0 to more than 30 times. In , the top five terms with the most occurrences represent a comparison of the number of times each word has been used and its relation to the topic of Tourists’ Well-being through different forms of Tourism. The same is reflected in a descriptive way in . The lower right quadrant shows the basic themes, and it is evident that ‘sustainable tourism’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘happiness’, ‘subjective wellbeing’, and ‘tourism’ are common themes that are touch based upon and worked on by researchers across the world. These findings were attained using a semi-automated approach that looked at the titles of all references to the study item and added relevant keywords that weren’t the author’s keywords. This was done so that the findings can capture more subtle differences.

3.2.5. Annual scientific production

Countries across the world focus on tourism to improve the economic and infrastructural conditions as tourism products and services cater for holistic growth for individuals, communities, organizations, and governments. With this, academicians have been working on strengthening research in tourism with increased importance given to the concept of wellbeing. The same is reflected in . Tourism contributes to the socio-economic development of urban and rural areas and boosts the revenue of the economy that will moreover increase the country’s GDP. Related to this is the creation of millions of jobs while it provides an ocean of opportunity for cultural exchange between foreigners and citizens.

Table 3. Annual scientific production.

3.2.6. World collaboration map

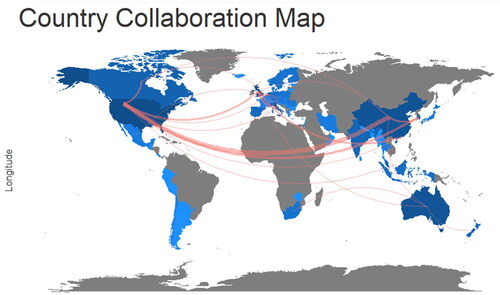

Country Collaboration Map sheds light on the collaborations among authors from different countries who have come together to publish papers in this area. The thick line between the countries indicates that more research papers have been published by authors based in these countries. Australia and New Zealand collaborated to publish 6 research papers on ‘Tourism’ which is the highest publication in the collaboration network, and both the countries are neighbouring countries. Although collaborations have occurred, also shows how few of the collaborations are from third-world countries and developing nations. Despite growing interest among policy makers to improve tourism in the aforementioned countries, the amount of research is negligible, and this is requests for a herculean call for academicians to collaborate and research and publish more relevant papers in the area of tourist wellbeing (Dsouza et al., Citation2023).

3.2.7. Most cited authors

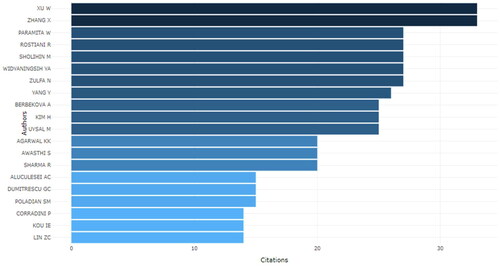

Consequently, this study categorizes several studies based on the authors who are frequently cited as well as the average number of times the work is cited each year. According to , Xu’s and Zhang’s research paper relating to Tourism and Tourist Wellbeing is the most cited author, with 33 citations respectively. There’s also Paramita, who has 27 citations and is the second most referenced author alongside Rostiani and Sholihin. Undoubtedly, the quantity of citations is a highly relative measure of the worth, recognition, and significance of the published results.

3.2.8. Bradford’s law and most relevant sources

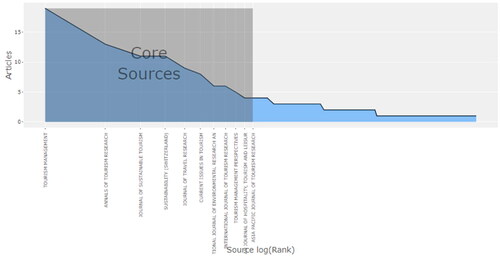

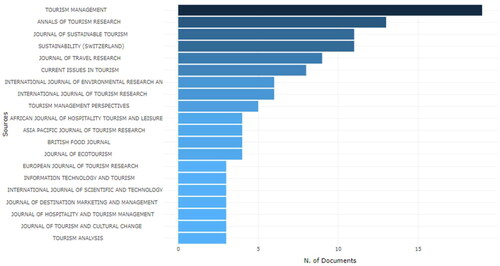

As a researcher, finding the right article from the right source plays a crucial role in enhancing the body of knowledge in the domain of interest. and represents core sources and most relevant respectively. While shows the function of Bradford’s law in reflecting the core sources in the domain, shows the number of publications in each relevant journal in the graphical format. Bradford’s law estimates the exponentially diminishing returns of searching for references in journals. As the researcher keeps looking for valid sources (most valid in this area being ‘Tourism Management’ followed by ‘Annals of Tourism’), the results that yield from this become more and more scanty and the relevance of those sources diminish. Eventually, the researcher comes to a point where the journals that reflect certain articles seem to be negligible and beyond consideration. Bradford’s law is also known as Bradford’s law of scattering or the Bradford distribution as it describes how the articles on a particular subject are scattered throughout the mass of periodicals. Another more general term that has come into use since 2006 is information scattering, an often-observed phenomenon related to information collections where there are a few sources that have many items of relevant information about a topic, while most sources have only a few. With this information, future researchers can get a better hold of relevant papers by finding papers in these journals.

4. Results and discussion

The results and analysis of the data show that research on Tourist Wellbeing has been fairly published by various journals and numerous authors but is not entirely robust. Sufficient limelight was shed upon drawing themes, interpreting them, and highlighting the sources that have published a great number of papers in the area of tourist wellbeing through tourism. The detailed analysis answers both research questions comprehensively. The data collected provides a crisp and clear understanding of the status of the study area with brief interpretations of relevant keywords, keyword co-occurrences, author contributions, and author collaborations. Thereafter, the analysis outlines how studies on tourist wellbeing have evolved over time and how the topics have emerged through generation of themes and clusters. The annual scientific production, thematic map, and Bradford’s law along with relevant sources shows how authors have developed interest to study this area while providing good number of suggestions and implications to various stakeholders in the tourism industry (RQ1). And finally, in the following section, we attempt to discuss robust suggestions through policy and practical implications that will aid the tourism industry to promote the concept of social and economic wellbeing across various platforms (RQ2).

4.1. Future research Agenda and implications

4.1.1. Future research Agenda

A detailed and more comprehensive examination of wellbeing and its link to sustainability within the tourism sector can bring a wave of change in the tourism literature. Additionally, concrete measures and interventions are needed to guarantee the promotion of wellbeing among tourists, communities, and service providers – the three main enablers of tourism success. Researchers can explore the depth of knowledge and information among these stakeholders around wellbeing that either encourage or discourage them to venture into promoting the concept. A detailed mapping of synergy between these stakeholders can also be looked at in terms of inter-dependency and inter-connectivity to introduce or advance wellbeing into the foray of core tourism services. Tourism experiences have the potential to enhance the wellbeing of both residents and tourists, presenting an opportunity for innovative developments in destinations (Dwyer, Citation2023; Godovykh et al., Citation2023). However, existing research in this area has predominantly focused on tourists, leaving an evidential gap in studies examining positive psychology variables specifically pertaining to local communities and service providers. This void can be filled by attempting to study the role of various elements on promoting wellbeing in tourism.

In addition, the long-term thriving of tourism is possible through the introduction of sustainable indicators. So far, research has shown the impact and significance of environmental, financial and resource sustainability on tourism. Future research can focus on how initiatives that involve tourists in community-based activities, such as volunteer programs, not only promote the wellbeing of tourists but also benefit the local community and contribute to the sustainability of the destination itself. Therefore, wellbeing can be strategically fused with organic sustainability that can produce plans to strengthen the overall competence of the tourism industry.

4.1.2. Policy implications

Every tourist perceives different forms of tourism activities in a different way. The level of excitement, enjoyment, satisfaction, tranquillity, adrenaline, meaningfulness, etc. is varies from one tourist to another (Ooi, Citation2005). While past research has predominantly concentrated on promoting tourism as a farm of hedonism, our study underscores the need to offer more than just memorable experiences to the tourists. Tourists seek more than the products and services offered to them during their vacation – they look for experiences. When the tourism industry caters to this, the community and economy as a whole are more likely to benefit from this as tourists tend to develop a sense of loyalty and belongingness towards the destination. Policy makers must formulate tourism policies in a way that it will educate service providers about the importance of tourist wellbeing, the need to develop tourism products and services to cater to the psychological needs of the tourists and provide a platform for holistic development of the tourism sector (Chand, Citation2013).

4.1.3. Practical implications

Subsequently, it needs to be noted that although eudemonic experiences offer a sense of wellbeing to tourists, it needs to be extended to the rest of the stakeholders involved in the process of providing these related services. Tourist will most certainly be enthralled with the momentary experience of wellbeing, but will, at one point of time, crave for a long-lasting transformation in lifestyle through these very experiences. This can materialize when tourism planners develop strategies and policies that support the holistic development of the area through a wisely adopted utilitarian approach. Only this can ensure the wellbeing of tourists, place, and community. Research around promoting tourism products and resources that provide a sense of wellbeing for tourists and other stakeholders is sparse and confusing. Parallel to this, Vada et al. (Citation2020) in their systematic review on tourist wellbeing posit that only a handful of studies attempt to examine the role of wellbeing as a marketing tool to increase tourism business. We suggest that the application of wellbeing as a tourism product must be practiced where it can also be linked to the concept of destination image where tourists’ revisit intentions can be gauged based on their experiences. Today, the millennials are hopping on to the trend of taking spontaneous vacations to break-free from stress but end up spending more time digitally documenting their tour than soaking in the glory of the surroundings. The very involvement of technology and digital gadgets snatches the purity of the vacation and directly hinders the wellbeing aspect – the initial purpose of taking the vacation. Future studies can empirically analyse the growth in this trend and offer strategic solutions to stakeholders to minimize or eliminate digital use and maximize the concept of experiential tourism that further enhances tourist wellbeing.

4.2. Limitations and future methodological scope

A major limitation in our study encompasses the fact that we have used only the Scopus database and not included ProQuest, Web of Science, and Taylor and Francis. Obtaining sample data from many different databases would significantly improve the learning. Second, we have used only the Biblioshiny tool in our research paper while there are several other tools for bibliometric analysis like Bibexcel, CiteSpace, Histcite, and VOS viewer, which are currently outdated but quite dynamic. Biblioshiny is more relevant in today’s academic culture, and it has offered a crisper understanding of the literature in the area of tourism wellbeing. Another downside to our study is that we have taken tourism in the global context and not focused on any specific country or specific geographical area. In addition, even though there are many publications from various timeframes we have limited the period frame from 2010 – 2020 due to the exponential increase in scholarly work in the tourism context during this time frame. The keywords used in the search strategy could include more relevant keywords and this limitation should motivate researchers to explore ways of collecting data from various databases with improved keywords for an in-depth analysis for future work in this area. In terms of methodology, SMARTER – a novel approach – and an extension of SMART is being applied by scholars to a limited extent. Future research can be conducted by using SMARTER given the availability of data.

5. Conclusion

The image of individual destinations contributes to the holistic image of the tourism industry. With the ascent of wellbeing in the realm of tourism, authorities at the grassroots of a destination must understand the dynamics of how communities and tourists can experience wellbeing through citizen-engagement and tourist involvement in the process. Tourism makes a prominent impact on economic as well as non-economic aspects of local communities through focus on economic indicators and job creation for the former and quality of life and sense of belonging for the latter. Additionally, authorities carry the onus of curating billboards, participatory kiosks and shows through which travellers can be educated about being responsible tourists. Destination marketing organizations (DMOs) can make sure that the potential competitiveness, performance, and success of a tourism destination is enhanced in the most organic and sustainable manner. This further builds a bridge between the local community and tourists thus ensuring destination wellbeing from the point of view of the community and destination protection. A sense of belongingness and responsibility among the tourists ensures that tourist feels safe at the destination. The same attributes lead to the tourists enjoying the place, its beauty, and everything that the destination offers, thus contributing towards the holistic wellbeing of the tourists, community, and destination.

This review aimed to investigate the significance of using wellbeing as a tourist product resource and to highlight the implications of promoting tourist wellbeing as a traverse that encourages holistic wellbeing. The findings shed light on the potential of a strategic synergy between tourism and tourists’ well-being. In terms of tourism development, it may be claimed that destination planners can use a productive approach to ensure the welfare of the area and its inhabitants, as well as provide visitors with experiences that enhance their wellbeing through the incorporation of a sustainable approach. Therefore, research on this topic must be regularly updated considering the ongoing expansion of the tourism sector.

Authors’ contributions

Komal Jenifer Dsouza (1st Author): Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the paper. Ankitha Shetty (Corresponding Author): Revising it critically for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

All data is furnished in the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Komal Jenifer DSouza

Komal Jenifer DSouza Dsouza is currently a research scholar at the Department of Commerce, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. She is in her final year of her Doctoral studies working in the area of Sustainable Agritourism. Email: [email protected] [email protected].

Ankitha Shetty

Ankitha Shetty is currently working as an Assistant Professor (Senior Scale) and is the Research Co-ordinator at the Department of Commerce, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. She serves as a PhD Research Guide in the area of Marketing, Insurance, Tourism, Rural Education, Psychology and Lo-Fi Music. She is an Editorial Review Board Member of Asia Pacific Journal of Business Administration, Emerald Publishers. Email: [email protected], [email protected].

Reference

- Angelstam P., Roberge, J.-M., Axelsson, R., Elbakidze, M., Bergman, K.-O., Dahlberg, A., Degerman, E., Eggers, S., Per, A., Esseen, J., Hjältén, Johansson, T., J., Müller, Paltto, H., T., Snäll, I., Soloviy., & J., Törnblom. (2013). Evidence-based knowledge versus negotiated indicators for assessment of ecological sustainability: The Swedish forest stewardship council standard as a case study. Ambio, 42(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-012-0377-z

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Aydin, D., & Ömüriş, E. (2020). The mediating role of meaning in life in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and subjective well-being. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), 8(2), 314–337. https://doi.org/10.30519/ahtr.656469

- Breiby, M. A., Duedahl, E., Øian, H., & Ericsson, B. (2020). Exploring sustainable experiences in tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1748706

- Bryce, D., Curran, R., O’Gorman, K., & Taheri, B. (2015). Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tourism Management, 46, 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.012

- Brymer, E., Cuddihy, T. F., & Sharma-Brymer, V. (2010). The role of nature-based experiences in the development and maintenance of wellness. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 1(2), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2010.9730328

- Buckley, R. (2021). Is adventure tourism therapeutic? Tourism Recreation Research, 46(4), 553–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1931775

- Buckley, R. (2022). Tourism and mental health: Foundations, frameworks, and futures. Journal of Travel Research, 62 (1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221087669

- Burda, Y. D., Volkova, I. O., & Gavrikova, E. V, National Research University Higher School of Economics. (2020). Meaningful analysis of innovation, business and entrepreneurial ecosystem concepts. Russian Management Journal, 18(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu18.2020.104

- Chand, M. (2013). Residents’ perceived benefits of heritage and support for tourism development in Pragpur, India. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 61(4), 379–394.

- Dsouza, K. J., Shetty, A., Damodar, P., Dogra, J., & Gudi, N. (2023). Policy and regulatory frameworks for agritourism development in India: A scoping review. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2283922. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2283922

- Dsouza, K. J., Shetty, A., Damodar, P., Shetty, A. D., & Dinesh, T. K. (2022). The assessment of locavorism through the lens of agritourism: The pursuit of tourist’s ethereal experience. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2147566

- Dunets, A. N., Yankovskaya, V., Plisova, A. B., Mikhailova, M. V., Vakhrushev, I. B., & Aleshko, R. A. (2020). Health tourism in low mountains: a case study. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(3), 2213–2227. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.3(50)

- Dutt, B., & Selstad, L. (2021). The wellness modification of yoga in Norway. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 5(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1948274

- Dwyer, L. (2023). Tourism development and sustainable well-being: A beyond gdp perspective. Open publications of UTS scholars (University of Technology Sydney), 31(10). https://doi.org/10.15308/sitcon-2020-3-7

- Farkić, J., & Taylor, S. (2019). Rethinking tourist wellbeing through the concept of slow adventure. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(8), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7080190

- Farkić, J., Filep, S., & Taylor, S. (2020). Shaping tourists’ wellbeing through guided slow adventures. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2064–2080. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1789156

- Filep, S. (2016). Tourism and positive psychology critique: Too emotional? Annals of Tourism Research, 59, 113–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.004

- Filep, S., Moyle, B. D., & Skavronskaya, L. (2022). Tourist wellbeing: Re-thinking hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 48(1), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480221087964

- Garcês, S., Pocinho, M., Jesus, S. N., & Rieber, M. S, University of Madeira. (2018). Positive psychology and tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(3), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14304

- Godovykh, M., Ridderstaat, J., & Fyall, A. (2023). The well-being impacts of tourism: Long-term and short-term effects of tourism development on residents’ happiness. Tourism Economics, 29(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166211041227

- Gupta, S., & Priyanka. (2023). Does participation in the service process affect tourists’ well-being? The mediating role of service experience. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2022.2162655

- Hanna, P., Wijesinghe, S., Paliatsos, I., Walker, C., Adams, M., & Kimbu, A. (2019). Active engagement with nature: Outdoor adventure tourism, sustainability and wellbeing. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(9), 1355–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1621883

- Hassan, T. H., Salem, A. E., & Saleh, M. I. (2022). Digital-free tourism holiday as a new approach for tourism well-being: Tourists’ attributional approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105974

- He, M., Liu, B., & Li, Y. (2023). Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(7), 1115–1135. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480211026376

- Kim, H., Lee, S., Uysal, M., Kim, J., & Ahn, K. (2015). Nature-based tourism: Motivation and subjective well-being. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(sup1), S76–S96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.997958

- Lötter, M. J., & Welthagen, L. (2019). Adventure tourism activities as a tool for improving adventure tourists’ wellness. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(1), 1–10.

- McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001

- Mertika, A., Mitskidou, P., & Stalikas, A. (2020). ‘Positive relationships’ and their impact on wellbeing: A review of current literature. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 25(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.12681/psy_hps.25340

- Moral-Muñoz, A., Moral, C. M., Pacheco, A. I., Manuel, D., & Espejo, A. S. (2020). Health economics: Identifying leading producers, countries relative specialization and themes. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.17561/ree.v2020n1.2

- Ooi, C.-S. (2005). The orient responds: Tourism, orientalism and the national museums of Singapore. Review, 53(4), 285–299.

- Pomfret, G. (2021). Family adventure tourism: Towards hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100852

- Pyke, S., Hartwell, H., Blake, A., & Hemingway, A. (2016). Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tourism Management, 55, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.004

- Rodrigues, S. P., Eck, N. J., Van Waltman, L., & Jansen, F. W. (2014). Mapping patient safety: A large-scale literature review using bibliometric visualisation techniques. BMJ Open, [online] 4(3), e004468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004468

- Smith, M. K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

- Sofronov, B. (2018). The development of the travel and tourism industry in the world. Annals of Spiru Haret University. Economic Series, 18(4), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.26458/1848

- Tantri, K. D., & Shetty, A. (2023). Mindfulness-based interventions as a breakthrough on occupational stress of working professionals: A trilogical approach, Vision. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629231191312

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., & Hsiao, A. (2019). The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.007

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., Scott, N., & Hsiao, A. (2020). Positive psychology and tourist well-being: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100631

- Voigt, C., Brown, G., & Howat, G. (2011). Wellness tourists: In search of transformation. Tourism Review, 66(1/2), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371111127206

- Xie, L., Chen, Z., Wang, H., Zheng, C., & Jiang, J. (2020). Bibliometric and visualized analysis of scientific publications on atlantoaxial spine surgery based on web of science and VOSviewer. World Neurosurgery, 137, 435–442.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.171