Abstract

This study aims to contribute to the policy discourse on the Bangsamoro peace process by examining the affect, behavior, cognition and attitude of stakeholders towards the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (OLBARMM) using the Tripartite Theory of Attitude. The study used a mixed methods research design, and conducted both survey and personal interviews. PLS-SEM and PLS-MGA determined the significant factors that affect the attitude towards OLBARMM and the significant differences by age and province. Quantitative findings of the study reveal that, in the overall model, both affect and behavior significantly and positively influence the attitude of respondents towards OLBARMM while cognition does not. This implies that feelings and actions are stronger determinants of attitude than actual knowledge of the law. Age did not emerge as a significant moderating variable, meaning that both younger and older respondents appear to follow a similar pattern with respect to attitude formation. Province however emerged as a significant moderating variable in terms of cognition, revealing that respondents from Maguindanao tend to rely on their knowledge of OLBARMM more than respondents from Lanao del Sur in deciding their overall attitude towards the law. Moreover, qualitative findings have further revealed that there is a general positive feeling towards OLBARMM however there are also critical challenges that must be addressed. The stakeholders have voted for OLBARMM but continue to harbor some apprehension and doubt as to its effectiveness. They are hopeful that it will be a tool to develop and stabilize the region.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Understanding the attitudes, perceptions and knowledge of the stakeholders on the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (OLBARMM) is important for two reasons. Primarily, it is a landmark legislation in as far as addressing one of the longest armed conflicts in the contemporary times. Secondly, and more importantly, the OLBARMM is hailed for having entrenched provisions that when effectively and efficiently implemented will lead to socially-inclusive, thus strengthening democratic governance in fragile context like the Southern Philippines. It also introduced the concept of a hybrid structure whereby a parliamentary form of government is adopted at the regional level, as an autonomous unit allowing greater fiscal and political powers yet supervised still by the national government through the office of the President. This kind of institutional design has been challenged by certain political actors within the Philippine state raises the question of constitutionality of the OLBARMM, thus makes the case of this study an interesting source of inquiry for students of social sciences, public policy, and peacebuilding experts and scholars. Noteworthy, the passage of the OLBARMM is identified as a necessary structural reform to address the persistent threat of violent extremism and terrorism in the country, and the larger Southeast Asian region.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

The RA 11054 or the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (OLBARMM) is part of the mandate in the Philippine Constitution. Foremost, it seeks to provide meaningful autonomy to the Bangsamoro people, acknowledging their distinct cultures and traditions in a manner that will not be prejudicial to the human rights of all citizens in the Philippines. Significantly, the organic law was ratified by the majority of votes casted in a plebiscite on January 21, 2019, including the current provinces of Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), Cotabato City, Isabela City in Basilan, 6 municipalities in Lanao del Norte, 63 barangays in the municipalities of Cabacan, Aleosan, Pigkawayan in the Province of North Cotabato and all other contiguous territory of which there is a petition of at least 10% of the registered voters of the inclusion of their areas to the proposed Bangsamoro core territory. Mother units, meaning provinces and cities where these barangay and municipalities belong should be garnered a majority of votes favoring their inclusion, and the municipality votes in favor of their inclusion. As stipulated, the Bangsamoro government shall have a parliamentary form of government; The form of government in the OLBARMM is Ministerial/parliamentary form of government which means that registered voters elect representatives in the Bangsamoro Parliament (BP). Then, the BP elects the Chief Minister, which appoints 2 Deputy Ministers and other Ministers to form the cabinet. The BP is composed of 80 members which comprise; 50% elected through party-based representatives, 40% from single member district representations and 10% sectoral/reserved seats for women, youth, IPs, settler and Christian communities. The Wali is appointed based on a resolution made by the Parliament where the selection is to be made from a list submitted by the Council of Leaders. He serves as the ceremonial head of the Bangsamoro Government. Noteworthy, what is not devolved to the Bangsamoro under the OLBARMM is the power of policing.

In terms of form of government, ARMM had separate executive and legislative powers while the BARMM, being a parliamentary form, has a fusion of the executive and legislative powers, wherein the Chief Minister is responsible for the legislative branch, the Bangsamoro Parliament. In OLBARMM, there is a ceremonial head of the regional government known as the Wali. In terms of the inclusivity provisions, OLBARMM reserves 10% of the seats in the Bangsamoro Parliament for non-Moro indigenous peoples and settler communities, women, youth, traditional leaders, and the ulama. Other novel inclusions in OLBARMM are: 1) promotion of rights of non-Moro IPs in the Bangsamoro region through the creation of a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (MIPA) to formulate and implement policies, plans, and programs for all IPs in the region, 2) representation of traditional leaders, non-Moro indigenous communities, women, settler communities, the Ulama, youth, and Bangsamoro communities outside of BARMM in the Council of Leaders that shall advice the Chief Minister, 3) respect for existing customary justice system of the Bangsamoro people and permission of its practice in harmony with the Constitution (ie. the Shari’ah, traditional or tribal laws, and other relevant laws), and 4) participation of women in the Bangsamoro Cabinet. Mechanisms for consultations for women and marginalized sectors.

The ratification of OLBARMM culminated the seventeen years of painstaking negotiations between the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the country’s largest Muslim separatist group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The OLBARMM provides the legal track in the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) which replaces the defunct ARMM and grants greater political autonomy to the region’s Muslim population. The OLBARMM has been the subject of much debate and controversy since its inception, with varying perspectives on its potential impact on the region’s economy, politics, and society. While the implementation of the OLBARMM is conceived to be a necessary requisite to addressing the political struggle of the Bangsamoro people to their Right to Self-Determination (RSD), yet critical questions remain prompting many observers, and the general public to have skeptical view regarding the politically negotiated peace process (Fincher, Citation2019). Among these questions include: how will the OLBARMM be implemented in practice? How do different stakeholders, including government officials, community leaders, and civil society organizations, perceive the OLBARMM and its potential impact on the region? What are the attitudes of various stakeholders towards the implementation of the OLBARMM, and what factors influence their views?

Bangsamoro is defined based on the salient features of the OLBARMM as follows: (1) as a shared socio-cultural identity, (2) expanded territorial autonomous region and, (3) as a form of government. Firstly, as defined in the OLBARMM, the Bangsamoro refers to ‘those who, at the advent of the Spanish colonization, were considered natives or original inhabitants of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago and its adjacent islands, whether of mixed or of full blood, shall have the right to identify themselves, their spouses and descendants, as Bangsamoro’ (Article 2, Section 1, RA 11054).

Historically, Bangsamoro is comprised of the thirteen ethnolinguistic groups namely: Iranun, Jama Mapun, Palawani, Molbog, Kalagan, Kalibugan, Maguindanao, Maranao, Sama, Sangil, Tausug, Badjao, and Yakan. These diverse ethnolinguistic groups spoke different languages and practice different cultures and traditions, however unified by their common adherence to the Islamic faith, thus, their collective aspiration to defend their hula (territory), agama (religion) and freedom as a Bangsa (nation). In retrospect, the initial armed resistance movement of the Islamized indigenous people in Mindanao has turned into a full scale ethnopolitical liberationist movement in the 1970s when the Bangsamoro movement gained support from the members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) against the systematic marginalization, and state-sponsored violence committed against the Bangsamoro people at the height of the Marcos dictatorship (Abinales, Citation2000). In his book, ‘Bangsamoro, A Nation under Endless Tyranny’, Salah Jubair wrote that the Bangsamoro RSD is fueled by their desire for genuine political autonomy through peace with justice resolve against the historical injustices of oppression and systemic exploitation committed by the western colonizers and continued by the neocolonial elite of the Philippine state (Jubair, Citation1999). In a nutshell, the Bangsamoro RSD is about fighting their right to territorial autonomy that will resolve one of the longest armed conflicts in the world - the Bangsamoro secessionist agenda in the Philippine South.

The second important thing in the implementation of the OLBARMM is the granting of expanded territorial autonomy to the 5-member core provinces of the BARMM: Lanao del Sur (including Marawi City) Maguindanao, Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi which now included Cotabato City and the 63 barangays of North Cotabato, the latter known as the Special Geographic Areas (SGA). While fostering inclusive governance should not be delimited to the territorial jurisdiction of a post conflict setting like the BARMM, yet inclusion of these communities allows for increased coordination between the regional government and the local government units amidst the challenges of transitioning into a new political structure of governance in the region.

Significantly, this paper also tackles the knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of the stakeholders relevant to the institution building in the Bangsamoro particularly on the political provisions (parliamentary form of government), economic provisions (fiscal autonomy), normalization (transitioning from rebel groups to parliamentarians) and policing and security. However, this article does not cover the substantial provisions and ‘thick description’ of each of these components since the main aim of the study is to examine the factors leading to these views and how they will potentially impact the policy implementation of the law. At the time of the data gathering, the OLBARMM has not yet been ratified. Ultimately, this research aims to contribute to a critical yet better understanding of the OLBARMM and its implications towards building sustainable peace and development in a fragile context. It is also important to note that there is scarce literature in terms of how actors’ attitude impacts post conflict peacebuilding practices, particularly with regard to politically negotiated laws that involve the national government and a minority group such as the OLBARMM.

Understanding the attitudes of stakeholders towards OLBARMM is important for two reasons. Primarily, it is a landmark legislation in as far as addressing one of the longest armed conflicts in contemporary times. Secondly, and more importantly, the OLBARMM is hailed for having entrenched gender-responsive provisions that when effectively and efficiently implemented will lead to socially inclusive, thus strengthening democratic governance in fragile contexts like the Southern Philippines. It also introduced the concept of a hybrid structure whereby a parliamentary form of government is adopted at the subnational level, as an autonomous unit allowing greater fiscal and political powers yet supervised by the national government through the office of the President. This kind of institutional design has been challenged by certain political actors within the Philippine state who raised the question of constitutionality of the OLBARMM, thus making the case of this study an interesting source of inquiry for students of social sciences, public policy, and peacebuilding experts and scholars. Noteworthy, the passage of the OLBRAMM is identified as a necessary structural reform to address the persistent threat of violent extremism and terrorism in the country, and the larger Southeast Asian region.

Theoretical framework

Attitude is described as the individual’s total approach to a particular object including positive and negative emotions, thoughts and actions toward the target (Fazio, Citation2007). They are deeply held beliefs about social and nonsocial objects that direct people’s actions (Mathews, Citation2009). Attitudes are products of stored knowledge or judgments and can either be singular or multiple. Intra-attitudinal structure for instance implies that one attitude towards the target is adopted while inter-attitudinal refers to attitude and or belief systems. A multidimensional view of attitude is deemed more reasonable because the entirety of attitude is often based on various judgment points.

This study is anchored on the Tripartite Theory of Attitude which posits that attitude is based on affect, behavior and cognition (Fabrigar & Wegener, Citation2005). This theory is one of the most preferred and widely accepted theories in attitude studies (Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993; Edwards, Citation1992). As suggested by the theory, the three constructs of affect, behavior and cognition represent the main factors affecting the formation of attitude. Other relevant constructs pertain to the particular objects or individuals being studied such as their demographic profiles that are equally essential in shaping attitude (Rinaca, Citation2006). One of the issues that arose with use of this theory is the high degree of similarity that exists among the main factors, leading researchers to argue that they may be one and the same (Breckler, Citation1983; Edwards, Citation1992; Kothandapani, Citation1971; Ostrom, Citation1969). But several studies have also counter-claimed that there is sufficient independence among affect, behavior and cognition to conclude that they are separate constructs supporting attitude (Rinaca, Citation2006). Affect, behavior and cognition are distinguished by their own antecedents. Feelings are developed through classical conditioning, beliefs through education and actions through exposure to previous reinforcement (Breckler, Citation1984). While these components are distinct from each other, it is implied that consistency across them must exist. This however presents a dilemma when an individual feels one way but acts another. In this case, it has been suggested that these components do not contribute equally but rather that one component may dominate in its influence on attitude (Mathews, Citation2009). Furthermore, recent scholars suggest that attitude is separate from affect, behavior and cognition and is thus a ‘general evaluative summary of the information derived from these bases’ as opposed to being composed of them (Fabrigar & Wegener, Citation2005).

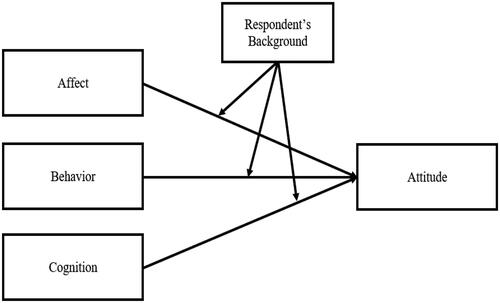

To define each construct, attitude refers to the psychological inclination to like or dislike a specific object (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). Affect refers to the positive and negative emotions felt about the target, sometimes without a logical basis. It can be driven by both the beliefs held about and prior experiences or lack thereof with the object (Rinaca, Citation2006). Feelings can be difficult to determine, even internally within the individual hence they are often evaluated based on certain actions. Actions are more easily measured and determined than affect or cognition but can be extremely challenging to change particularly if they stem from social norms or culture. Behavior is the response to the target or tendency to react in a certain way when facing an object or specific circumstance (Edwards, Citation1992; Garimella, Citation1999). Finally, cognition is interchangeably used with beliefs and this refers to the stored knowledge about a target (Berger, Citation2002; Oltedal et al., Citation2004). It refers to the thoughts or knowledge about an object as gained through exposure or learning ().

Building on the Tripartite Theory of Attitude, the following conceptual framework is presented:

This study evaluated the attitude of select BARMM citizens towards the OLBARMM vis-a-vis an assessment of their feelings towards the law, whether they have voted in its favor and their knowledge of the law. Affect, behavior and cognition are presumed to hold linear relationships to attitude. Respondents’ background, which included age and province, were included as moderating variables. These variables are necessary, as suggested by the Tripartite Theory of Attitude, to check for a relationship between respondent’s background and their attitude, and if such exists, to determine the demographic variables that hold significant influence on attitude. Furthermore, the inclusion of various demographic variables (ie. gender, age, income, location) have been explored by other attitude studies and wherein these variables have been found to be significant.

Hence, the aim of this study is to determine the factors affecting the stakeholders’ attitude towards OLBARMM and examine the effect of the stakeholders’ background in terms of age and province. The study also sought to provide additional qualitative insights to better contextualize and understand the factors that shape the stakeholders’ attitude.

Methodology

This is a sequential explanatory mixed methods study that was conducted using survey and personal interviews. Due to the logistical difficulty in securing respondents from the island provinces of Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi, the research team decided to limit the data gathering to the mainland provinces of Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur. Data was gathered through survey interviews that took place from September to October 2019. Following the correct study protocol, free prior informed consent forms were given to key informants and chosen respondents before interviews were held to collect data. The literature that is currently available was compiled for references and validation reasons.

The research locales were selected based on their inclusion in the voting population for the approval of OLBARMM. Respondents were identified and selected using convenience and snowball sampling. Researchers deemed these sampling techniques as suitable given the lack of database that can be used for this study.

The survey instrument contained 35 questions: 3 on background, 14 on affect, 1 on behavior, 15 on cognition and 2 on attitude. Questions on affect, behavior and attitude were phrased as statements or questions to which respondents had to agree or disagree. Meanwhile, cognition was assessed through multiple choice questions that gauged how much respondents knew and understood about OLBARMM. A breakdown of the questions can be seen below:

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to treat the data. Descriptive statistics include minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation. Inferential statistics include Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Henseler’s Partial Least Squares Multi Group Analysis (PLS-MGA). To ascertain the effects of affect, behavior and cognition on the overall attitude of the respondents towards the OLBARMM, PLS-SEM was used. This is a statistical method for examining the connections between variables in a dataset and the intricate interactions between them to determine which factors have the most influence on a specific dependent variable. PLS-SEM is particularly useful when there are complex relationships mapped out in a model, there are many constructs or indicators, sample size is small or data distribution is not normal (Hair et al., Citation2011). Additionally, PLS-SEM is helpful in assessing a theory’s accuracy and identifying areas where it might need to be improved by contrasting the analysis’ findings with the predictions made by the theory (Hair et al., Citation2017). In this study, PLS-SEM is deemed suitable to conveniently test the relationships between the independent and dependent variables, while also testing for the significance of the moderating variables to further build the theory.

On the other hand, the comparison of various groups or subgroups within a dataset is possible with PLS-MGA, an extension of PLS-SEM. PLS-MGA divides that data into two or more groups to test for the associations between the variables within each group independently. This enables researchers to determine differences or similarities between the groups, as well as to pinpoint the factors by which each group’s outcome variable is affected (Ringle et al., Citation2022).

Ultimately, the intention of using PLS-SEM and the Tripartite Theory of Attitude is to ascertain if affect, behavior, and cognition are significant predictors of voters’ attitude. Furthermore, the inclusion of the moderating variables age and province allows us to explore whether the theory can be extended to account for the effect of respondent’s background in the context of attitude towards OLBARMM.

Finally, to better contextualize the results of the quantitative phase, this paper utilized qualitative analysis with descriptive research methods. There were a total of 12 key informant interviews (KII) from the provinces of Lanao del Sur and Maguindanao, including Marawi City and Cotabato City respectively. Interviews were done in private settings where respondents felt comfortable openly conversing with the researchers as they recorded. In both phases, respondents were explained the research purpose and their written consent was secured. Transcribed interviews were then coded, and thematic analysis conducted to identify common themes related to the affect, behavior, cognition and attitude of the respondents. In addition, secondary data analysis through desk research was also conducted to triangulate the results from the interviews.

Results and discussion

Quantitative phase

Descriptive statistics

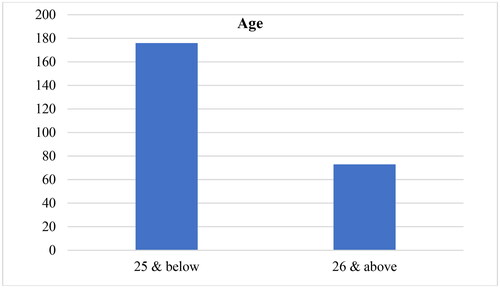

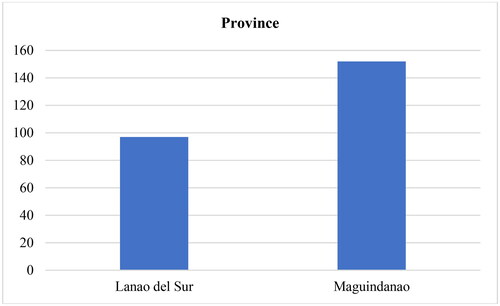

A total of 249 respondents were surveyed for the purpose of this study. Breakdown of their background profile can be seen in the figures below.

Of the 249 respondents, 176 were 25 years old and below while 73 were 26 years old and above. Age was classified into these two age brackets to distinguish between the students/new graduates and working adults. Moreover, there were 97 respondents from Lanao del Sur and 152 from Maguindanao ( and ).

Inferential statistics

Below are the results of the statistical analysis. The table displays path estimates and p-values for each of the relationships among constructs. lists the questions corresponding to affect, behavior, cognition and attitude as based on the provisions of the OLBARMM. The breakdown of questions is further supplemented by secondary data analysis which is discussed in the succeeding section.

reveals that both affect, and behavior significantly and positively influence the attitude of respondents towards OLBARMM (p<.05). This means that the higher respondents score on affect and behavior, the more likely they are to hold a favorable view of the law. It can be recalled that affect measures the respondents’ perceptions and feelings, behavior determines whether they have campaigned and or voted in favor of the law, and attitude evaluates their overall approval of it. Cognition, on the other hand, does not appear to have a significant influence on attitude, suggesting that the respondents’ knowledge of OLBARMM does not hold a relationship with their overall approval, or lack thereof, of the law.

Table 2. Path estimates.

Table 3. f square values.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics by respondents 25 years old and below.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics by respondents 26 years old and above.

In the context of the study, the Moro people fought for their dream of a Bangsa (moro nation) that is truly peaceful and developed for years. Their protracted struggle for the right to self-determination is thought to have reached a resolution with the implementation of the OLBARMM. This elucidates why they support the law since it is thought to be a new political entity that will solve the undesirable status quo in the Bangsamoro region, which is what everyone is aiming for. The OLBARMM is seen positively by research interviewees because it benefits the Bangsamoro. Respondents believe that OLBARMM is the result of a peace settlement with dignity and offers genuine self-governance based on their own cultural and traditional practices.

Subsequently, in one of our key interviews, one of the respondents has reiterated that the passage of the OLBARMM would mean the ‘recognition of the distinct identity of the Moro people with their aspiration to be governed by their own kind of leaders, against the Christianized majority of Filipinos, whom they perceived have been treating them as ‘others’ in the Philippine society (KII, Cotabato City, 02 October 2019). This means that their positive feeling towards the law is influenced by their positive behaviors towards it, regardless of if they have understood the law in its entirety or not.

There are scholars who argue that ethnonationalist movements are more of a product of the socio- political structures, particularly during the colonial state formation. Using a combination of political ethnography and historical interpretation of identity-based struggle of the Muslims in the Philippines, McKenna in his anthropological analyses of the Bangsamoro rebellion argued that Muslim nationalist identity is a colonial legacy particularly of the American colonial authorities that work to their advantage. Hence, it could be deduced that the politics that divide the different Moro fronts are a mere product of external manipulation which succeeded by the local leaders’ collaborationist attitude towards the colonial powers (McKenna, Citation1998).

On the other hand, Julkipli Wadi, Professor of Islamic Studies at University of the Philippines, contends that there is a clash of frames in the formation of Bangsamoro state-building and the Philippine government’s nation-building. He characterized it as a form of ‘tier-making’ and ‘tier-changing’, wherein the government is continuously engaged in the US colonial method of pacification and integration in Mindanao and Sulu Archipelago, on the contrary. Thus, for Wadi, the Moro struggle is based on the premise that the Bangsamoro has an inalienable right to self-determination on the basis of their political claim for sovereignty. Wadi has also reiterated that the fundamentally antithetical assumptions of the Philippine government and the Moro struggle, at least on nation-building and self-determination, continues to be constructed and reconstructed until today (Wadi, Citation2000). Hence, the instrumentalization of ‘Moro identity’ towards political accommodation in Philippine national polity. In the context of this study, affect and behavior of the respondents are shaped by this discourse of politically-negotiated identity called Bangsamoro.

From the adjusted R-squared value of 63.5%, we can conclude that affect, behavior and cognition are able to substantially explain the respondents’ attitude (Hair et al., Citation2011). Moreover, presents the f-square values which determine the effect size of the predictors on attitude. It can be seen that affect and behavior exceed the minimum required criteria of 0.10 (Lowry & Gaskin, Citation2014), with affect having the largest effect size of 1.293. This means that, in comparison to the other predictors, affect has the strongest influence on attitude.

To examine the moderating effect of respondent’s background, Partial Least Squares Multi Group Analysis (PLS-MGA) was then conducted to check for significant differences among groups of respondents according to their age and province. PLS-MGA is ‘a type of moderator analysis where the moderator variable is categorical (usually with two categories) and is assumed to potentially affect all relationships in the inner model’ (Hair et al., Citation2014). In this study, Henseler’s PLS-MGA approach was utilized. This method of MGA compares each centered bootstrap of the second group of data to each centered bootstrap of the first group in all bootstrap samples (Sarstedt et al., Citation2011).

Before proceeding to the PLS-MGA results, we first present the descriptive (–) and inferential statistics which aim to summarize the dataset and statistically analyze the resulting model respectively.

The PLS algorithm () shows that affect and behavior significantly and positively influences the attitude of respondents who are 25 years old and below (p-value < .05). Cognition does not seem to hold equal importance. For respondents 26 years old and above (), only affect was found to significantly and positively influence their attitude (p-value < .05). The results further imply that the attitude of younger respondents is primarily driven by their feelings, perceptions and actions they have taken to promote OLBARMM, whereas the attitude of older respondents is driven by their feelings and perceptions of the law.

Furthermore, it can be inferred that the stronger the positive feelings that younger respondents have towards OLBARMM and the more they translate these feelings into concrete actions that promote the law, the more favorable is their view of the law. Their knowledge of OLBARMM does not necessarily make a difference in the formation of their attitude, or, in other words, whether they know much or little of it, it does not appear to affect how they view it. Their attitude forms regardless of their knowledge. In addition to this, the results indicate that younger respondents are more likely to have a favorable attitude towards OLBARMM if they campaign and or vote in favor of it. This is not the case with older respondents, where behavior does not affect attitude. It appears that older respondents can possibly hold favorable feelings and attitudes towards the law despite not campaigning or voting in its favor. Older respondents’ attitude is mostly just shaped by their feelings towards the law. Like younger respondents, older respondents’ attitude also forms independently of their knowledge on OLBARMM.

For respondents from Lanao del Sur (), only affect and behavior significantly and positively influence their attitude. On the other hand, affect, behavior and cognition significantly and positively influence the attitude of respondents from Maguindanao (). The results indicate that the effect of knowledge on OLBARMM is different between the two groups, where the attitude of Lanao del Sur respondents does not seem to be influenced by how much or little they know about the law. However, Maguindanao respondents, on average, scored one point higher than respondents from Lanao del Sur, and the effect of their knowledge on OLBARMM is clear in determining their overall approval of the law. Nevertheless, the common ground between the two groups is that they both rely on their positive feelings about OLBARMM and actions in deciding their attitude towards it.

Norwegian anthropologist, Frederik Barth argues that the significance of self-identity within a delimited set of borders, not culture, was what constituted the ethnic group. This instrumental view of ethnic struggle, as in this case, the Bangsamoro struggle, claimed that ethnicity is a manipulation to maximize political and material gain (Davidson, Citation2008).

Interestingly, there has been no sultanate which was traditionally the seat of power of the Bangsamoro communities, past or present, with overall control of the various Muslim groups though each group has a similar political system. A Muslim group may be broken up into one or more sultanates or Datuships (Majul, Citation1985). Moreover, the Moro sultanates were also characterized by a kinship system which polarized loyalties and interest along blood lines. It caused rivalries and dissension. These loosely knit sultanates were not always united during their struggle against colonial powers (Man (W.), 1990). Hence, the primordial ties of the Moro society to their ethnicity, tribalism and Datuship system is considered as one of the internal factors which caused primordial disunity among them (Gowing, Citation1979). Their identity as Moros and sense of oneness is only tied up by Islam as a religion and a mobilizing ideology (Tanggol, Citation1993).

Furthermore, although the relationship did not prove to be significant, knowledge on OLBARMM appears to have a negative effect on the attitude of Lanao del Sur respondents. This implies that the more they know about the law, the less likely they are to form a positive attitude towards it.

Patronage politics is reinforced by the colonial state formation of elite accommodation under U.S. and Philippine regimes. Such is the view of Patricio Abinales, who pointed out that the centralizing and authoritarian Marcos regime exposed the communal identity’s fragility of ethno-nationalist movements as both a primordial and a mobilizing symbol; manifested by the case of the once united front of the Bangsamoro movement, the MNLF, before the split of the Maguindanaon-led MILF and the short-lived Meranao-led MNLF reformist group (Abinales, Citation2000). In post-colonial societies, the culturally-homogenizing, socially fragmenting, and atomizing processes of modernization, induced largely through state intervention, thus creates conditions of social and economic vulnerability and insecurity. As such, ethnic groupings have to organize and compete for resources through bargaining with the state. When a certain community or ethnic grouping interprets insecurity as the result of the competing group, wherein the latter have gained through favors and patronage from the state, structural inequality subsumes (Abinales, Citation2000). In the case of the Bangsamoro peace process, the increased awareness to the law, meant also the unequal socio-economic and political representations of the Moro people against the dominant majority who happened to legislate the kind of autonomy which is perceived to be still at the disadvantaged of the Moro communities, as shown in the failure of then ARMM to eliminate economic insecurities and social unrest in Southern Philippines.

and present the results of Henseler’s PLS-MGA. Developers of the PLS-SEM software suggest that p-value is significant at values lower than 0.05 or higher than 0.95. In , no significant differences exist between younger and older respondents in terms of influence of affect, behavior and cognition on attitude. Although the two groups tested differently with respect to the influence of behavior, the PLS-MGA result reveals that this difference fell short of becoming significant (p=.090). Thus, age is not a significant moderating variable.

Table 13. Henseler’s PLS-MGA results by province.

Alternatively, a significant difference between respondents from Lanao del Sur and Maguindanao was noted with respect to the influence of cognition on attitude (p = 0.01) (). This suggests that respondents from Maguindanao tend to rely on their knowledge of OLBARMM more than respondents from Lanao del Sur in deciding their overall attitude towards the law. Hence, it can be inferred that province is a significant moderating variable, albeit in the overall model, cognition did not test as a significant determinant of attitude. This inference holds true only for respondents from Maguindanao and not other groups.

It can be deduced that as an ethno-nationalist struggle with multiethnic character, the Bangsamoro liberation movement is confronted with not only vertical dimension of the conflict, that is people-to-government conflict, but more so with horizontal dimension of the people-to-people conflict that leaves the question of how different ethnic identities influencing the political direction of the liberation movement in their struggle for socioeconomic and political development. Thus, the role of ethnification in the Bangsamoro movement may be seen as instrumental towards mobilization in the short term, ensuing ethnic cleavages in the long term as political entrepreneurs among the ethnic leaders create ‘differentiated population’ to gain socio-political ends (Kothari, Citation1989). Ethnic conflict reflects competition between elites for ‘political power, economic benefits and social status. In modernizing societies such as the Philippines, the development of ethnic consciousness is heavily dependent upon industrialization, the spread of literacy, urbanization, growth of government employment opportunities, and the new social classes produced by such developments (Zartmann, Citation1995). According to Brass, the potential for nationalism is not realized until some members from one ethnic group attempt to move into the economic niches occupied by the rival ethnic (Smith, Citation2003). In the current BARMM set-up, the need to actualize an inclusive and moral governance remained to be seen.

As shown in the findings of this phase, knowledge of the OLBARMM does not significantly affect the attitude and behavior of the respondents, such that primordial ties with ethnicities and the ethnonationalist subjectivities of the Bangsamoro struggle shaped the perceptions, and consequently the behavior and attitudes of the people in the region.

Qualitative phase

Affect

Based on the articulations of the KIIs, the general feeling toward OLBARMM is one of hope but also worry. Respondents are hopeful that the law will be successful in establishing one policy and legal framework to unite the Moro region. Nevertheless, there are clear apprehensions as to its efficacy, especially within the given period of time. Perceived challenges include the insufficiency of the 3-year transition period to establish credible and strong institutions, and frailty of the democratization process in the region. The goal of the Bangsamoro government is to win over both the national government and its own citizens. Bangsamoro cannot progress as an autonomous region unless the national government learns to truly trust and grants it full autonomy. Another major challenge is the persistent threat of violent extremism in the region, as manifested by the Marawi siege, and family feuds, or locally known as ‘Rido’, that perpetuate further disenfranchisement and a fragile peace condition.

The establishment of the OLBARMM started a three-year transition period (2019-2022) for an interim Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)-led government, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) until elections for the first Bangsamoro Parliament are called for in 2022. The transition to a new form of government and a new degree of autonomy under the OLBARMM presents an opportunity for political change – and potentially, for wider and more inclusive governance. The 80-member BTA, composed of diverse members - MILF, representatives of other former rebel groups, and multi-sectoral representatives, is mandated to establish a parliamentary democracy, including specifically by putting in place the necessary legal framework for the elections and other key democratic processes and principles. There are sixteen women members appointed to the BTA, some of whom holding key portfolios. However, formal institutions of power do not guarantee inclusion of diverse views and interests, nor are they assumed to take up marginal concerns such as those of the minority groups or marginalized sectors. Representatives need backing and support from civil society organizations and interest groups to properly understand and propose pro-people agendas towards sustainable peace and development.

Inclusive participation, meaning the ability of different political and interest groups to participate in political decision-making and governance through formal or informal means, is a requisite to genuine participatory democracy. Inclusivity in post-conflict democratic transition is particularly critical where exclusion, injustices and marginalization have been at the heart of conflict. This has been the case in Muslim Mindanao where conflict is rooted in historical injustices through successive colonization and post-colonial state building by the Philippine central government. Exclusion is further amplified by hierarchical traditional societies, dominance of powerful clan dynasties, lack of economic development and persistence of land conflicts (Francisco, 2014).

These issues have particular impacts for Indigenous Peoples (IPs) living in the BARMM. Minority-within-minority communities, as the IPs of BARMM, rely even more heavily on their civil society and political representatives to stand up for the rights and interests of their communities. Within the Bangsamoro, IPs are one of the most marginalized groups. Many IPs, such as the Teduray Lambiangan, have high hopes in the BARMM transformation and the group’s own participation and support of policy development will be critical to making this a reality. The OLBARMM reserves two seats for IPs in the BTA, and also establishes a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples Affairs. Establishing how these institutions and representatives will consult, stay informed on, and represent indigenous issues is critical in the transition period, and their relationships with IP organizations and other civil society actors will be essential to fulfilling these functions. IPs will also require support in understanding and exercising their rights under the new governance system established by the OLBARMM, which leaves them vulnerable to lack of coverage from the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples Affairs. After all, the ultimate goal of the expanded autonomous region is to ensure that ‘no one is left behind’ in development.

Beyond the challenges of participation noted above, the OLBARMM calls for a shift to the Parliamentary system of government where BARMM is expected to adopt a new electoral system. It envisions the formation and registration of genuinely principled political parties, an entirely new system different from the national level. As such, CSOs in BARMM must understand how these institutions and processes function and complement each other. For CSOs and other stakeholders to have a meaningful and constructive role in BARMM’s transition and beyond, they must understand the role of political parties and why it is important to consider forming themselves into political parties that are institutionalized and more representative of their respective advocacies. Information on how to form parties in terms of ideological platforms and registration processes is also critical as reiterated by one of the CSO leaders during the interview (KII, October 20, 2019).

Behavior

The respondents supported and voted for OLBARMM because they believed it to be the fulfillment of the Bangsamoro people’s aspirations. Aiming for a Bangsa that is genuinely peaceful and productive, where the Bangsamoro co-create growth, is a step. According to one respondent, progress and peace must always go hand in hand and cannot ever be divorced from one another. Peace is defined as a state in which people feel safe and secure. For them, the Bangsamoro will be at peace when it is as affluent as it should be; otherwise, the Bangsamoro’s principles will be shaky and ambiguous.

Key interviewees subsequently hold the view that OLBARMM is a tool for regional development and is seen as a new political entity that aims to address the unfavorable status quo in the Bangsamoro region. They see OLBARMM to be an expression of their right to self-determination as a subnational unit of governance. One of the main respondents, the grand Mufti of BARMM, asserts that OLBARMM is the outcome of their struggle. It is a government based on moral governance and the injunction of the Qur’an and sunnah of Prophet Muhammad. One of the characteristics of moral governance is the pursuit of knowledge through reading the Qur’an as a manual for leadership.

Attitude

The challenge in the implementation of the OLBARMM revolves around the absorptive capacity of the BARMM bureaucracy. Key interviewees assert that adopting the new institutional design as a parliamentary system is challenging because those in charge lack technical expertise, especially the MILF, which is still undergoing its transformation from rebel to ruler/parliamentarian. As a result, it is necessary to train them so they can be effective administrators. Contrarily, even while most of the interviewees advocate for the creation of a merit-based bureaucracy in the Bangsamoro, some continue to support the efficacy of laws derived from the glorious Qur’an. Islamic principles should not conflict with traditions.

Further, the dominating groups (Meranaws, Maguindanaons, and Tausugs) in the Bangsamoro region continue to be viewed as being divided. According to one respondent, these groups are now breeding enmity because of these ethnic dynamics. In addition to the division, there is still a problem with corruption in the BARMM region that needs to be resolved.

Conclusion

In summary, the study uncovered some crucial findings about people’s attitude towards OLBARMM. From the overall model, it was found that affect and behavior significantly influence attitude. This finding was reiterated in the results of younger respondents and respondents from Lanao del Sur, where affect and behavior were also revealed to be the only significant determinants of attitude. On the contrary, the attitude of older respondents is solely driven by their affect while the attitude of respondents from Maguindanao is shaped by affect, behavior and cognition. Lastly, province tested as a significant moderating variable, however only with respect to the cognition-attitude relationship.

This study pointed out the irrelevance of cognition in shaping attitude, excluding the case of respondents from Maguindanao. To review, cognition in this study was measured through 15 items that aimed to establish how much respondents knew about OLBARMM. The items asked questions on general and basic information about the law. The irrelevance of cognition suggested by the results is worrying. This implies that the respondents’ attitude is largely driven by their feelings and decision to vote in favor of the law, not necessarily their knowledge of it. This further suggests the strong influence of culture and social norms as contributors to the shaping of attitude in the sense that many respondents reported feeling optimistic about OLBARMM or confirming that they voted in its favor primarily because of most of their family and friends. Hence, the favorable attitude exhibited by respondents towards OLBARMM now may not necessarily always be the case because it is not mainly driven by accurate information but rather feelings and norms. This of course can be an alarming state for a young community that is only beginning to establish its political identity within the larger Filipino identity.

The respondents are optimistic that OLBARMM would succeed in creating a unified legal and policy framework for the Bangsamoro region. However, there are obvious doubts about its effectiveness, particularly given the time frame. The perceived difficulties include the region’s fragile democratic process and the 3-year transition period’s inadequacy for establishing reliable and robust institutions. Further, key interviewees claim that the MILF, which is still in the process of transitioning from rebel to ruler/parliamentarian, lacks technical expertise, making it difficult to adopt the new institutional design as a parliamentary system. As a result, it is essential to send them on administrative training so they can perform their duties better. On the other hand, even though most of the interviewees support the establishment of a merit-based bureaucracy in the Bangsamoro region, others still believe that regulations originating from the Qur’an are effective. Traditions and Islamic beliefs should not be at odds.

Key interviewees consequently believe that BARMM is a tool for regional development and that it is viewed as a new political entity that seeks to change the unfavorable status quo in the Bangsamoro region. As a subnational level of government, it is regarded as an expression of self-determination. The respondents voted for OLBARMM because they think it represents the aspirations of the Bangsamoro people, that is to create a prosperous and peaceful society.

Recommendations

The findings of this study must be considered vis-a-vis its limitations. First, the study limited the grouping of respondents according to their age and province as these variables were thought to have the ability to impact all relationships. Knowing the acceptance of the law by province is essential, given the divide of dominating groups (Meranaws, Maguindanaons, and Tausugs) in the Bangsamoro region. These groups greatly influence the shape of the socio-political order in the BARMM’s provinces. Similarly, age was a significant moderating variable in this study since it indicates how the next generation views and accepts the law. In order to ratify the law as needed in the future, the opinions of the younger generation are crucial. In addition, while limited to populations within the BARMM region, the findings have implications on advancing inclusive governance mechanisms and policies that can benefit similarly situated contexts in a post-conflict environment.

The OLBARMM is certainly an important piece of legislation that spells inclusive, peaceful and democratic governance in the Southern Philippines. However, given the limited scope and locale of the study, it is imperative to come up with a cross-sectional analysis of the knowledge, attitude and perceptions of multi stakeholders given the emerging context where the Bangsamoro autonomous region has now been established, with expanded territorial jurisdiction to include the Regional center of Cotabato City, Maguindanao del Norte and the Special Geographic Area located in North Cotabato. As mentioned, it would also be interesting to look into the perception of the Bangsamoro respondents outside the geographical scope of the BARMM and how it affects the implementation of the provisions in the expanded fiscal and political power of the new autonomous government.

For this reason, it is recommended that future researchers investigate other moderating variables such as gender, educational attainment and ethnicity to better understand how personal characteristics influence the attitude of individuals towards policy making and implementation in BARMM. Respondents also shall not be limited to Muslim respondents as it is indicated in the RA 11054 that Bangsamoro is more than Muslim Mindanao because it includes the non-Moro migrants and their descendants and the non-Muslim indigenous people residing in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. This allows for a more granular look at the differences within the Moro population and how different backgrounds perceive OLBARMM. This is also in keeping with the theoretical framework which previously suggested that demographic details are also essential in determining individual attitude towards an object.

The OLBARMM must establish and adopt laws and regulations that are based on moral governance and are based on the injunction of the Qur’an and the sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) so that they will be appreciated and adhered to by its citizens. Islam is seen as a religion of peace, and religion is thought to be the unifying denominator across the three major ethnic groups (Meranaws, Maguindanaons, and Tausugs). This can end the animosity brought on by these ethnic dynamics and the corruption issue in the BARMM region.

Moreover, it is also recommended that campaigns to raise awareness and disseminate information about OLBARMM’s progressive and policy accomplishments continue, not just in schools but also in communities, particularly among the grassroots, in the barangays where the majority of impoverished families reside. Universities and colleges located in the province of Bangsamoro should partner with local governments to improve outcomes by institutionalizing Republic Act 11054 awareness programs as extension work. Consequently, academic institutions should continue collaborating with the BARMM administration to carry out initiatives that go beyond simply educating the public about the law to include initiatives for governance, policy reforms, and peacebuilding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Table 1. Breakdown of questions.

Table 8. Path estimates for 25 years old and below model.

Table 9. Path estimates for 26 years old and above model.

Table 6. Descriptive Statistics by Respondents from Lanao del Sur.

Table 7. Descriptive Statistics by Respondents from Maguindanao.

Table 10. Path estimates for Lanao del Sur model.

Table 11. Path estimates for maguindanao model.

Table 12. Henseler’s PLS-MGA results by age.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yasmira P. Moner

Asst Prof Yasmira P. Moner, MGS is a faculty of the Department of Political Science, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology. Her research interests include post-conflict governance, peace processes, social movements and political dynamics in the Bangsamoro.

Sittie Akima A. Ali

Ms. Sittie Akima A. Ali, DPA is an Administrative Officer V of the Human Resource Management Division, and also an Associate Lecturer of the Department of Political Science, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology. Her research interests include violent extremism, peace education, public policy, and public administration.

Safa D. Manala-O

Asso Prof Safa D. Manala-O, PhD is a faculty of the Department of Business and Innovation, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology. Her research interests include conflict and post-conflict entrepreneurship, and consumer behavior.

References

- Abinales, P. N. (2000). Making Mindanao: Cotabato and Davao in the formation of nation-state. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Berger, P. (2002). The cultural dynamics of globalization. In Many Globalizations: Cultural Diversity in the Contemporary World. Oxford University Press.

- Breckler, S. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.47.6.1191

- Breckler, S. J. (1983). Validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude [Doctoral dissertation]. The Ohio State University.

- Davidson, J. S., et.al. (2008). The study of political ethnicity in Southeast Asia. In E. M. Kuhonta (Eds.), Southeast Asia in Political Science: Theory, Region, and Qualitative Analysis (pp. 205–211). Stanford University Press.

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Edwards, K. (1992). The primacy of affect in attitude formation and change: Restoring the integrity of affect in the Tripartite model [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Michigan.

- Fabrigar, L., & Wegener, D. (2005). The structure of attitudes. In The Handbook of Attitudes (pp. 79–124). Routledge.

- Fazio, R. (2007). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations of varying strength. Social Cognition, 25(5), 603–637. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.603

- Fincher, M. (2019, January 18). Defining momen for the future of Mindanao [We log post]. https://www.iri.org/news/the-bol-plebiscite-a-defining-moment-for-the-future-of-mindanao/

- Garimella, R. (1999). A study of the knowledge and attitudes of physicians toward victims of spouse abuse [Doctoral dissertation].

- Gowing, P. G. (1979). Muslim Filipinos: Heritage and horizon. New Day Publishers.

- Hair, F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Hair, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Jubair, S. (1999). Bangsamoro, a nation under endless tyranny. IQ Marin. 364p.

- Kothandapani, V. (1971). Validation of feeling, belief, and intention to act as three components of attitude and their contribution to prediction of contraceptive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031448

- Kothari, R. (1989). Ethnicity. In D. Kumar & S. Kadirgamar (Eds.), Ethnicity: Identity, Conflict and Crisis (pp. 20–24). Arena Press.

- Lowry, P., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2014.2312452

- Majul, C. A. (1985). The contemporary Muslim movement in the Philippines. Berkeley Mizan Press.

- Man (W.), C. K. (1990). Muslim Separatism: The Moros of Southern Philippines and the Malays of Southern Thailand. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Mathews, M. (2009). Thankful feelings, thoughts & behavior: A tripartite model of evaluating benefactors and benefits.

- McKenna, T. M. (1998). Muslim rulers and rebels: Everyday politics and armed separatism in the Southern Philippines. University of California Press.

- Oltedal, S., Moen, B., Klempe, H., & Rundmo, T. (2004). Explaining risk perceptions. An evaluation of cultural theory.

- Ostrom, T. (1969). The relationship between the affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of attitude. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(69)90003-1

- Rinaca, C. (2006). The use of the Tripartite Model of Attitudes to explain EMS providers’ attitudes about the EMS agenda for the future [Doctoral Dissertation]. Old Dominion University.

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2022). SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS. https://www.smartpls.com

- Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J., & Ringle, C. (2011). Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. Measurement and Research Methods in International Marketing, 22, 195–218.

- Smith, B. C. (2003). Understanding third world politics: Theories of political change and development (2nd ed). PalGrave McMillan.

- Tanggol, S. D. (1993). Muslim autonomy in the Philippines: Rhetoric and reality. Mindanao State University Press and Information Office.

- Wadi, J. (2000). Strategic Intelligence Analysis of Philippine National Security: Muslim Secessionism and Fundamentalism. Strategy and Conflict Studies of the Command and General Staff College Training and Doctrine Command, Philippine Army, Makati City, 14.

- Zartmann, W. I. (1995). Collapsed states: The disintegration and restoration of legitimate authority. Lynne Reinner Publishers.