Abstract

It is no longer debatable that China has become Africa’s most significant trading partner having surpassed the United States and its allies back in 2009 as Africa’s main trade partner in the world. During this period, South Africa has emerged as one of China’s imperative allies in the world and its most important partner in Africa. This article draws on historical secondary data sources and relies on constructivism theory to delineate the evolution of South Africa-China relations. This analysis reveals the range of historical, social, economic and political interests that contributed to the evolution of South Africa-China relations in the manner that it did for the past few decades. This analysis also shows how the relations between South Africa and China have been shaped and influenced by a range of interests and identities in line with constructivism theory postulations. This article discusses the contested phenomenon of whether the relationship between South Africa and China represents symmetrical or asymmetrical cooperation. The article concludes that asymmetry exists in the relations between the two countries in the economic sphere, however, this could not be argued to the same extent in other areas of their engagements. Therefore, it is expected that the two countries will continue to advance their relations despite the criticism against their collaboration, as both remain committed to this relationship anchored on long-shared historical interests and identities.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

It is no longer debatable that China is a significant rising global superpower (Zhang, Citation2022) and has an imperative role to play in global politics and the world economy as a representative of developing countries (Le Pere & Shelton, Citation2007). China remains the only developing nation to hold veto power in the United Nations (UN) as a permanent member of the Security Council (Feltman, Citation2020). Within the UN system, China has formed the Beijing-Moscow tactical partnership with Russia which has further heightened both countries’ importance in world politics (Maizland, Citation2022). The alignment between China and Russia within the UN is not surprising as the two countries are involved in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) (Shoba, Citation2018). Feltman (Citation2020, p. 1) opines that the Beijing-Moscow alliance within the UN was “demonstrated in July 2020 when China and Russia vetoed two resolutions regarding Syria, and both blocked the appointment of a French national as special envoy for Sudan.” Apart from its power within the UN, China holds a sizeable voting share of 6.09% in the International Monetary Fund (IMF), making it the third largest member of the IMF, after the United States (US) and Japan. Also, China is a significant member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and various other important international organisations.

The foregoing backdrop shows that China’s substantial power rests in its economic strength, and to some extent, its geopolitical power and influence in multilateralism (Zhang, Citation2022). China also seems to derive some of its power from the economic opportunities the country creates for its allies in the areas of trade and developmental support through aid, grants and state-funded loans and investments (Sun, Citation2020; Zhang, Citation2022). Over the past decade, the major beneficiaries of Chinese developmental support, grants and state-funded loans and investments have been African countries (Sun, Citation2020). Currently, China is the main trading partner to Africa, having overtaken the US in the year 2009 (Subban, Citation2022). Similarly, Africa is an important and strategic partner of China (Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). History shows that Africa and China have supported each other in different endeavours—Africa supported China to unseat Taiwan from the UN in 1971 (MacLeod, Citation2022) and China supported African countries, such as South Africa, in their fight against Apartheid (Jiang, Citation2021). Currently, China has diplomatic relations with fifty-two of the fifty-four African states. Eswatini and the Republic of Somaliland remained the only two states in Africa to have official relations with Taiwan (Deych, Citation2018). South Africa is China’s largest trade partner in Africa (Shoba, Citation2022) and the two countries share important historical links dating back to the 1950s (Lin, Citation2007).

China’s presence in Africa and its engagements with some African countries, such as South Africa, have been a subject of scholarly and public discourse (Shoba, Citation2023). In the main, research undertaken on China-Africa relations has focused primarily on the economic and political aspects of the relationship (Bodomo, Citation2009; Bond, Citation2013; Moyo, Citation2016; Shivambu, Citation2014; Xiong, Citation2012). The studies have also focused on what China gains from these relations, thus depicting African states as passive participants, whereas African countries like Ethiopia and South Africa have been actively engaging with China in different initiatives (Chiyemura, Citation2019). As a result of the concentration on the economic and political aspects of the relations between China and Africa, a limited number of studies have focused primarily on the evolution of China-Africa relations. Accordingly, this article aims to offer a qualitative historical account of the evolution of South Africa-China relations. To achieve this, this article adopted a qualitative historical design to delineate the evolution of South African-China relations. The qualitative historical research approach involves integrating and synthesising data from many different sources to elaborate on a phenomenon under study (Thies, Citation2002). This could be undertaken by studying and employing primary and secondary historical data sources. This article relied on secondary data sources drawn from previous studies/extant literature on South Africa-China relations. This implies that no original historical data was gathered to compile this review. The review of the relations between South Africa and China was limited to the years between 1949 and 2018.

Theoretical considerations on South Africa-China relations

China-Africa relations have ignited a polarising debate on the conceptualisation of the implications of this relationship between China and African countries such as South Africa (Bodomo, Citation2009; Bond, Citation2013; Moyo, Citation2016). This phenomenon has been examined from different theoretical perspectives in the international relations literature (Kansaye, Citation2021). However, the most common theoretical lenses employed in several studies include realism and liberalism (Matambo, Citation2020). Those from the realism school of thought perceive China’s engagements with African countries as propelled by its national interest centred on economic and geo-strategic interests (Bond, Citation2013; Kansaye, Citation2021). Scholars from this cohort have likened the growing presence of China in Africa to neo-colonialism/neo-imperialism (Zhang, Citation2022). Among these scholars, there is a growing consensus that China, in its engagements with African states, shows significant neo-colonialist/neo-imperialistic features that may undermine the sovereignty of African states (Bond, Citation2013; Edel & Chan, Citation2018). The premise of realism is that anarchy characterises world politics and proposes that states are self-interested actors in international relations (Chiyemura, Citation2019).

Conversely, those from the liberalism school of thought view China’s engagement in Africa as “a consequence of globalisation rooted in China’s domestic modernisation program that began in the late 1970s” (Kansaye, Citation2021, p. 26). In this regard, scholars posit that China’s interest in Africa is a result of the Chinese Going Global strategy, initiated in 1999 (China Policy, Citation2017). Some of the arguments presented under this school of thought tend to agree with the realist view that China’s engagements with African countries are mainly self-interested in furthering China’s ambitions in international relations. Therefore, most studies conducted on this relationship have significantly focused on what China gets out of these engagements and depict African countries as passive actors (Chiyemura, Citation2019; Moyo, Citation2016; Shoba, Citation2022). The focus on the accumulation of African natural resources by China, arguably to sustain its economic development to satisfy its bourgeoning population and other strategic needs, is cited in the literature to support the notion of China being self-interested (Otele, Citation2020).

However, limited studies have approached these relations from the constructivist ideological perspectives (Chiyemura, Citation2019; Otele, Citation2020; Kansaye, Citation2021; Matambo, Citation2020). Constructivism has evolved gradually as one of the key theoretical tools of dialectic analysis in international relations when studying state engagements in world politics. The primacy of constructivism on social relations and ideational values are key factors in world politics. Chiyemura (Citation2019) argued that material forces are not the only driving factors in state engagements, which contrasts with realist tenets of egoism and anarchy. Matambo’s (Citation2020) constructivist analysis of South Africa-China relations draws from the historical relations between the two countries. Matambo (Citation2020) cogently elaborates that South Africa’s, and in general Africa’s,) interest in China, and vice versa, are shaped by their historical engagements, identities and long-shared social interest in world politics. This is in contrast to realism and liberalism, as constructivism emphasises that state engagements are propelled by “the social structure in which actors are embedded” (Matambo, Citation2020, p. 65). In this regard, constructivism, as delineated by Alexander Wendt quoted in Mengshu (Citation2020, p. 4), highlights that “the structures of human association are determined primarily by shared ideas rather than material forces.” This theory does not dismiss the notion of material forces in international relations; however, it emphasises that “the development of identities and interests is endogenous to social relations among actors” (Checkel, Citation1998, p. 324). Accordingly, this review article adopts the constructivism theory to study the historical evolution of the South Africa-China relationship in world politics.

Evolution of historical interests and identities in South Africa-China relations

In the twentieth century, the prospect of official diplomatic bilateral engagements between South Africa and China, and other developing countries, seemed dim. The fact that South Africa was under the oppressive rule of the Apartheid government presented a barrier to establishing bilateral cooperation with China and several other countries (Chiyemura, Citation2014). The relations between South Africa and China were initially formed in 1949 between the National Party of South Africa and the Nationalists of China (Alden & Park, Citation2013). This was in the aftermath of the National Party’s ascendence to power in South Africa in 1948 (Hamill, Citation2018), wherein the National Party decided to maintain political ties with the Republic of China/Taiwan (ROC) instead of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) (Alden & Park, Citation2013). For almost three decades, there were minimal bilateral interactions between South Africa and China as the relations between the two countries were kept to an insignificant consular level of interaction (Lin, Citation2007). This was even though the relations between the two sides were informed and driven by common interests in “anti-communism and a desire for both countries to counter their respective international pariah status” (Alden & Park, Citation2013, p. 644).

However, the political situation changed on October 25, 1971, when the United Nations (UN) passed a historic resolution that recognised the PRC as “the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations” and expelled the ROC, led by Chiang Kai-shek, from the UN (United Nations [UN], Citation1979, p. 2758). This change prompted the National Party to upgrade its bilateral engagements with the ROC as the consular-level interactions were elevated to the ambassadorial level in 1976 (Alden & Park, Citation2013). This resulted in robust political and economic relations based on shared anti-communist, nationalist ideologies and a pariah status within the international community being cemented between the two countries (Anthony et al., Citation2013). Moreover, there was a major increase in the migration of the Chinese population to South Africa, with most of them investing in different businesses in the country. Taiwan Today (Citation1980) reported that the two-way trade between the two countries had reached an astounding US$200 million in 1979, demonstrating the importance of engagement between the two countries. A study by Anthony et al. (Citation2013) estimates that the ROC’s business investors had ploughed more than US$100 million into South Africa by 1987. This demonstrates that South Africa had become an imperative economic partner to Taiwan (ROC) and a massive investment destination for both the ROC’s public and private businesses.

The relations between the two countries were further solidified with an official visit by the Head of State, P.W. Botha, to Taiwan in 1980 (Taiwan Today, Citation1980) and 1986, and once again by F.W de Klerk in 1991 (Dullar, Citation1994). The ROC’s delegation had arrived in South Africa earlier which led to the upgrading of the relationship between the two countries. Moreover, there were academic exchange programs and a series of cultural exchange initiatives that saw the Cape Town Symphony Orchestra visit Taiwan to play at the Taipei Arts Festival (Dullar, Citation1994). Markedly, in the late 1980s, the National Party of South Africa sought to form relations with the PRC despite its official ties with the ROC (Alden & Park, Citation2013). According to Le Pere and Shelton (Citation2007), the PRC responded that South Africa must end Apartheid and derecognise Taiwan (ROC) in favour of the One China doctrine. The National Party’s conduct in trying to forge relations with the PRC concretises the long-standing international relations notion that countries engaged in diplomacy have no permanent allies but only permanent interests.

Nonetheless, the National Party of South Africa and the Nationalist Party of China were determined to continue solidifying their relationship despite the pressure from the international community. Conversely, the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the African National Congress (ANC), and other South African political formations had established relations. The South African Communist Party (SAPC) was particularly important as official party-to-party relations were codified between the CPC and the SAPC (Jiang, Citation2021). The CPC would ultimately establish formal relations with all of the political formations in South Africa. Jiang (Citation2021) claims that the CPC provided sustained mutual support to the black peoples’ liberation movements (SAPC& ANC) in terms of political endorsement, financial and material assistance or cadre training throughout the 1950s and 1980s in their struggle against Apartheid. However, Matambo (Citation2020) argues that there was an epoch when the PRC and the ANC-SAPC alliance collapsed because of the perception that the PRC continued to have secretive trade with Apartheid South Africa. Matambo (Citation2020) claims that this perception dented China’s propagated commitment to supporting the struggle against the Apartheid regime.

Another epoch was when the ANC-SAPC alliance sharply criticised the PRC over the Sino–Vietnam conflict (Jiang, Citation2021). The relations between the PRC and the ANC-SAPC alliance were later restored when Oliver Tambo (1983) and Joe Solvo (1986) visited China and interacted with CPC officials. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the relations between the ROC and the National Party of South Africa remained intact in the early 1990s and continued even after the political changes that occurred in South Africa in 1994. Historical documents show that the ROC made a substantial donation of an estimated US$25 million to the ANC’s election campaign in 1994 (Le Pere & Shelton, Citation2007). The acceptance of donations by the ANC gave hope to the ROC that relations between the two countries would be maintained post the 1994 change in government. Some scholars suggested that the ROC’s donations assisted the ANC in winning the general elections in 1994 (Le Pere & Shelton, Citation2007). In context, Alden and Park (Citation2013) contend that the ROC was confident that its relations with South Africa would continue under the new ANC government of South Africa.

Contemporary South Africa-China relations: different opportunities and challenges

When the ANC, under the leadership of Nelson Mandela, ascended to power in 1994 after a victory in the general elections (South Africa History Online [SAHO], 2015), it faced a twofold conundrum regarding China. The ANC had to decide whether to (1) embrace relations with the ROC (a legacy inherited from Apartheid) and form new ties with the PRC, and thus embrace a dual China (Williams & Hurst, Citation2018), or (2) completely cut ties with the ROC and recognise the One China policy that the PRC had been pushing for (Dullar, Citation1994). This presented a serious challenge to the ANC because of its historical ties with China. Also, this presented an enormous challenge to the new government, especially because Nelson Mandela was the president of the new administration. President Mandela was a well-respected leader in world politics, and the international community was observing how his government was going to navigate the ROC-PRC issue. The international community that supported South Africa in its struggle against Apartheid embraced the new South Africa, however, the ROC was under pressure, as Williams and Hurst (Citation2018, p. 650) write “in 1994, only 29 states formally recognised the Republic of China, whereas 155 countries recognised the PRC.”

Despite the difficulties in the relations between the ANC and the PRC over the years since the 1950s (Jiang & Shu, Citation2019), the PRC did not anticipate delays in the formalisation of relations with South Africa after 1994 (Jiang, Citation2021). This anticipation was based on the understanding that the ANC and the PRC had enjoyed decades of engagement during the struggle against Apartheid. However, things did not transpire in the manner that the PRC had anticipated, as President Mandela began speaking of “dual recognition” suggesting that his government intended to retain the relations with Taiwan/ROC, which were formed under Apartheid and establish official ties with the PRC as well. What impelled President Mandela and the ANC to start proclaiming a two-China policy as opposed to a one-China policy? Jiang (Citation2021, p. 69) postulates that “the economic performance of Taiwan as well as the largesse donated by Taipei, among others—may help explain the shifts of Mandela’s attitude.” This shows that President Mandela wanted to prioritise the national interest in this situation. However, the PRC would not accede to President Mandela’s insistence on dual recognition and continued to diplomatically engage the ANC and government on the matter.

Indeed, the ROC/Taiwan was increasingly isolated by the international community as more countries continued to instead recognise the PRC (Williams & Hurst, Citation2018). Therefore, it was only a matter of time before President Mandela made his inaugural visit to China in April 1998, which officially marked the beginning of South Africa-China relations (Songtian, Citation2018; Uzodike, Citation2016; Wenjun, Citation2018). Ever since then, the relationship between South Africa and China has deepened over the past two decades (Grobler, Citation2021; Mpungose, Citation2018; Shoba, Citation2018; Songtian, Citation2018; Wenjun, Citation2018). The past two decades of diplomatic ties witnessed a rapid intensification of bilateral trade, investments, and engagements between the two nations, expanding beyond the usual state bilateral engagements to form a strategic partnership and eventually a comprehensive strategic partnership (Alden & Wu, Citation2014; Grobler, Citation2021). Scholars have argued that South Africa is viewed as a gateway to Africa that provides China with an export destination and source of raw materials (Uzodike, Citation2016). Moreover, Chiyemura (Citation2014) posited that this comprehensive strategic partnership provides China with an opportunity to expand its political and economic outreach throughout the African continent. Similarly, China has been described as an opportunity for South Africa to diversify its economic relations and draw investment from alternative sources (Xiong, Citation2012).

Furthermore, South Africa perceives China as an important partner in world politics, especially regarding the shift towards global multi-polarity in favour of developing countries (Shoba, Citation2017). The momentum in the relations between South Africa and China was elevated by the election of Jacob Zuma as the President of South Africa (Jiang, Citation2021). As Shoba (2017, p. 178) posits that “the advent of Jacob Zuma came with a heightened level of engagements between South Africa and China.” These relations have been reinforced by frequent high-level visits to the head of states from both countries as well as business, trade delegations, bi-national commissions, military drills and party-to-party engagements (Anthony et al.,Citation2013; Fabricius, Citation2019). Shoba and Mtapuri (Citation2022) opined that the establishment of bi-national commissions in the 2000s ensured that there are regular government-to-government interactions between the two countries (Department of International Relations & Cooperation [DIRCO], 2014). In keeping with the growth of the relations between the two countries, the Inter-Ministerial Joint Working Group on Cooperation was formed in 2010 and ratified in 2013 during President Xi Jinping’s visit to South Africa (DIRCO, Citation2014). Shoba and Mtapuri (Citation2022, p. 5) argued that the “formation of bi-national commissions and working groups have fostered and guided the relations between the two countries”. below shows the number of state visits by President Xi Jinping to Africa since he became the (seventh) president of China.

Table 1. Top five African countries visited by Xi Jinping (2013–2018).

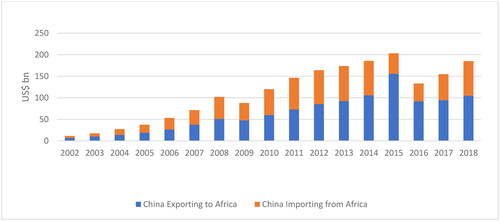

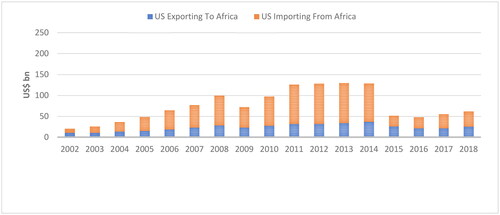

The frequent number of official state visits by President Xi to South Africa are indicative of the importance of South Africa to China in the context of its relations with the African continent (Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). High-profile officials from South Africa have also paid several reciprocal visits to China. Former President, Jacob Zuma, paid several official state visits to China during his tenure as the country’s head of state. It was not surprising then when President Cyril Ramaphosa debuted his travel as the head of state to China (The Presidency, Citation2018). Wenjun (Citation2018) emphasised that such close engagements symbolise the high level of political, bilateral and strong strategic mutual trust between the two nations. It is no surprise that such a prominent level of engagement at the political level between the two countries also translates to increased economic cooperation between them. In the context of economic cooperation between the two countries, it is important to review their relations from the perspective of the broader facets of China-Africa trade. below shows the composition of China-Africa trade from the year 2002 to 2018. While shows the composition of the US-Africa trade for the same period.

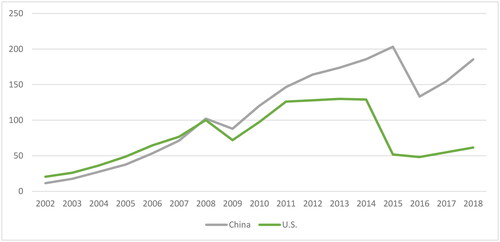

Looking at both and above, it is clear that the structure of China-Africa trade composition and US-Africa trade composition has dramatically changed, with China becoming the largest exporter to Africa, whereas the data on the US-Africa trade denotes a relative balance in terms of export and import from both sides, although, the US seems to have imported more from African countries. According to the research conducted by the China-Africa Research Initiative (Citation2020), the value of China-Africa trade in 2018 reached US$185 billion, which was an increase from US$155 billion in 2017. Within this China-Africa trade composite, South Africa remained China’s largest trading partner in Africa and accounted for a quarter to a third of China-Africa overall trade (Songtian, Citation2018, p. 19). However, research conducted by the China-Africa Research Initiative (Citation2020) revealed that Angola is the largest exporter to China from Africa, followed by South Africa and the Republic of Congo. Scholars have attributed this situation to the fact that South Africa’s exports to China are mainly concentrated on natural resources and other related raw materials. It is not surprising that South African exports to China are less than that of Angola, even though South Africa is the largest trading partner to China, as South Africa’s exports to China are mainly concentrated in raw materials (Shivambu, Citation2014; Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). below shows the US-Africa trade compared with China-Africa trade.

Figure 3. US-Africa trade vs China-Africa trade (US billion). Source: China Africa Research Initiative.

As shown in above, China’s bilateral trade engagements with African countries have bolstered continually despite the 2008 global financial crisis and the relative decline in commodity prices in the year 2014. This was accompanied by a major decrease in US bilateral trade engagements with African nations. It appears, from above, that the US-Africa trade has struggled to maintain its momentum since the financial global crisis occurred in 2008 and further suffered during the weak commodity prices recorded in 2014.

Looking at both above and below, in the last decade, the structure of South Africa-China bilateral engagements has undergone an important transformation, characterised by a sustained increase in the volume of South Africa’s exports to and imports from China and, to a limited extent, vice versa. According to Wenjun (Citation2018), the bilateral trade between South Africa and China totalled US$39.17 billion in 2017, a figure more than twenty times the figure recorded at the start of the country’s diplomatic engagement. However, it is also important to note that, despite the increased volume of South Africa’s exports to China, its main composition is still mainly concentrated in minerals and natural resources (Shivambu, Citation2014). below shows South Africa’s top exports and imports global destinations as of 2018.

Table 2. South Africa’s top five export and import markets as of 2011.

Table 3. South Africa’s top exports and imports global destinations as of 2018.

Consequently, some views characterise this relationship as highly asymmetrical. From this view, South Africa is heavily dependent on China, and while, Beijing has clear goals and ambitions within this relationship, Pretoria on the other hand, lacks a strategy in this regard. Hence, the growing perception is that South Africa is necessarily subordinated to China’s will and control, being unable to direct and affect the outcomes of this bilateral relationship. For instance, during a Finance Committee meeting in parliament, the former Minister of Finance was quoted as saying “I understand the concerns that the committee has regarding the loan … However, China are our friends. It is very difficult to set rules when it comes to friends and money” (quoted in the press by Magubane, Citation2018). This demonstrates that South Africa is not in a position to define the terms of engagement with China. South Africa and China stand in different positions when it comes to their economic, military and political capabilities, which are the most important factors used to measure a country’s capabilities. For instance, China’s population is currently estimated at over 1.4 billion (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022), whereas South Africa’s population is estimated to be 60,6 million as of the end of June 2022 (Statistics of South Africa [StatsSA], 2022). Likewise, in the military expenditure realm, South Africa’s defence budget was estimated at around US$3270.00 million in 2022 (Trading Economics, Citation2022), while China’s defence budget was US$229.5 billion, which is one of the largest in the world and second only to the US military budget (Grevatt & MacDonald, Citation2022). Such differences in key factors such as population and military are indicative of the asymmetry that exists in the relationship between the two countries.

Discussion: towards a symmetrical or asymmetrical relationship?

China is a big investor in Africa, as the value of China-Africa trade in 2018 reached US$185 billion, which was an increase from US$155 billion in 2017 (China-Africa Research Initiative, Citation2020). South Africa, as the largest African trading partner to China, accounts for a quarter to a third of China-Africa’s overall trade (Songtian, Citation2018). Torrens (Citation2018) opined that Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) to South Africa reached USD$15.2 billion, which made China a key investor in South Africa. As of 2020, China’s cumulative investment in South Africa exceeded US$25 billion, creating more than 400,000 direct and indirect jobs in the country (Grobler, Citation2021). Strengthening economic collaboration with South Africa remained a critical aspect of the broader China-Africa relations (Anikola & Tella, Citation2022). Within the broader facets of China-Africa engagements, South Africa has been one of the major beneficiaries of China’s state-funded loans (Shoba, Citation2022). Although South Africa is one of the major beneficiaries of Chinese FDI and state-backed loans, the country is still not a high-rate borrower from China compared to other African countries, however, this does not mean that China has not assisted South Africa in times of need. For example, in 2018, China granted a massive R33.4 billion state-funded loan to South Africa’s energy supplier, Eskom (Khumalo, Citation2018).

Beyond state-funded loans and grants accorded to South Africa by China (Anikola & Tella, Citation2022), there is also a substantial number of Chinese private companies that exist in South Africa. In 2014, former President, Jacob Zuma, oversaw the opening of a Fortune 500 First Automobile Works (FAW) China Group Corporation footprint in South Africa. Former President Zuma remarked,

“Following our BRICS trade agreements, this massive investment by a Chinese corporation augers well for the future of this partnership between our countries. Today’s FAW Coega plant opening has the added advantage that South Africa remains seen as an investment destination of choice. This is an example to other global companies, which can rest assured that the South African government is doing everything possible to maintain its world-class offering as a springboard into unlocking the potential of the African continent.” (quoted in a communique by First Automobile Works [FAW], 2014).

Corresponding with the foregoing comments, Mr Qin Huanming, the Vice President of the China FAW Group Corporation was quoted, “As a shining pearl on the African continent, South Africa enjoys sound political, economic, and legal systems, as well as excellent infrastructure and abundant labour resources. These favourable conditions have strengthened FAW’s confidence to invest in South Africa” (FAW, Citation2014, p. 3). The establishment of the FAW’s South African plant was a US$60 million investment by the Chinese consortium, including China FAW Group Corporation, and the China-Africa Development Fund (CAD-Fund) together with FAW Africa Investment Company LTD. The plant celebrated its 7000th assembled unit millstone in 2021 which coincided with the seventh year since the plant’s inception (Coega Development Corporation [CDC], Citation2021). Commenting on this milestone, a CDC official, stated that, “nothing gives us greater joy than seeing our investors doing well on the back of a depressed economic environment. It is also worth mentioning that FAW SA was also named as the Global Distributor of the Year 2017 and South Africàs second biggest truck exporter” (CDC, Citation2021: 1). Arguably, the story of FAW could be one of the major results of the comprehensive bilateral relations between South Africa and China. According to Gouvea et al. (Citation2020), there are more than 180 Chinese conglomerates and thousands of small-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that have their footprint in South Africa. The Chinese conglomerates in South Africa include China Longyuan Power and United Power, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, HiSense, Jinchuan Group, the China–Africa Development Fund, Beijing Automobile International Corporation, Hebei Iron and Steel Group, Construction Bank of China, Bank of China, and China Development Bank (Gouvea et al., Citation2020).

Likewise, South Africa is also a major African investor in China (Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022) with its companies, such as Naspers and South African Brewers Miller (SAB Miller), playing a leading role in the Chinese market (Bodomo, Citation2009; Songtian, Citation2018). Currently, Discovery, Exxaro, Standard Bank, Sasol, AngloCoal, Spur, Standard Bank, and Old Mutual are among the South African companies actively participating in Chinese domestic markets (Shoba, Citation2017; Akinola & Tella, Citation2022). South Africa’s FDI in China exceeded US$700 million in 2016, making the country the largest African investor in terms of both quantity and quality (Wenjun, Citation2018). While South Africa is a major African partner to China, other African countries, such as Angola, Egypt and Nigeria, are playing a major role in China-Africa relations. For instance, Nigeria remains the largest recipient of Chinese overall FDIs in Africa, despite the fact South Africa is Africa’s largest trade partner with China and that Southern Africa remains the top Chinese export and import market destination (Mureithi, Citation2022; Sow, Citation2018; Torrens, Citation2018), while Angola is the largest African exporter to China from Africa, followed by South Africa and the Republic of Congo (China-Africa Research Initiative, Citation2020).

However, it is not surprising that South Africa’s exports to China are less than that of Angola, even though South Africa is Africa’s largest trading partner to China. This has been attributed to the fact that South Africa’s main exports to China consist of iron, steel, copper, platinum, diamonds, scrap and waste, and chromium ores (Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). While the composition of South Africa’s exports to China includes mainly raw materials and unfinished goods (Shivambu, Citation2014; Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022), China’s exports to South Africa include electronic equipment, plastics, footwear, gaiters and the like, machinery, nuclear reactors, boilers, organic chemicals, and vehicles as well as trains and trams (Trading Economics, 2018), which are all finished goods and products. Some scholars have described the foregoing stated asymmetry in trade relations between South Africa and China as one of the contradictions associated with their relationship (Alden & Park, Citation2013; Moyo, Citation2016; Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). Akinola and Tella (Citation2022) postulate that South Africa has a trade deficit with China because the country continues to export unfinished goods to China. Similarly, Shivambu (Citation2014) posited that the composition of South Africa-China imports and exports demonstrates that South Africa remains a traditional economy and that this has resulted in the trade deficit that South Africa has with China. In the same vein, Alden and Wu (Citation2014, p. 15) attributed this situation to South Africa’s “high imports of value-added goods and China’s increasing demand for mineral products” which Anikola and Tella (Citation2022, p. 597) argue “may hamper South Africa’s industrial growth.”

The foregoing theses demonstrate that asymmetry exists in the relations between South Africa and China, especially in economic terms. In this context, Shoba and Mtapuri (Citation2022) argue that the notion of asymmetry has merit when considering that China’s economy is approximately twenty-nine times the size of the South African economy, and as such, the impression that China is the dominant partner in this relationship finds bearing. Accordingly, scholars and some media houses have criticised China’s engagements with African countries. China’s lending in Africa has become one of the issues that have stirred controversy. In this regard, Bond (Citation2013) likened China’s engagements with African countries to colonialism and imperialism. This is a general view from those who approached these relations from a liberal ideological point of view. The fact that China invests more in African countries, such as South Africa and Nigeria, than they invest in China, has been put forth to support the recolonisation/neo-colonisation claim (Winning, Citation2018). Others argue that Chinese loans and aid to African countries would eventually facilitate a takeover of the African countries’ key institutions (Bond, Citation2018). There have also been reports that China’s import has collapsed South Africa’s clothing and textile industry as well as the country’s manufacturing capacity (Booysen, Citation2015).

However, the foregoing theses have been downplayed by officials from both China and African nations. For instance, President Cyril Ramaphosa was quoted as stating, “we export to China what we extract from the earth and China import to us what they make from factories” (Stone, Citation2018, p. 7). Effectively, President Ramaphosa dismissed the notion of China’s colonialism in Africa and classified the engagements between South Africa and China as a win-win situation. Official structures from both sides often posit South Africa and China as equal and mutual partners whose relations are necessarily harmonious owing to the complementarity of their national economies and the shared interests in international relations. The foreign policy elites and officials from China, including President Xi himself, often described China’s engagements with South Africa, and the developing countries in general, as some form of a win-win situation based on mutual understanding and respect for one another’s sovereign affairs. The Chinese diplomat Tian Xuejun described Africa as a good friend and partner to China (Xuejun, Citation2012).

Similarly, the former Ambassador of China to South Africa, Lin Songtian, posited that China is a reliable, productive and beneficial partner to South Africa. Further, Songtian emphasised that, over the years, a multi-layered, wide-ranging and all-dimensional cooperation framework between China and South Africa has taken shape (2018, p. 7). There are also African decolonial scholars, such as Schoeman (Citation2011), Chiyemura (Citation2019), Moyo (Citation2016) and Ado and Su (Citation2016), who have sought to downplay the notion of neo-colonialism/neo-imperialism about China-Africa engagements. These scholars have posited that most of the postulations on China-Africa relations lack substance and are often generalised and based on media reportage. Specifically, Moyo (Citation2016, p. 59) postulates that “The recolonisation thesis is mainly posited by various liberal Western scholars and is widely floated in the mainstream media, as well as by some African scholars, using the epitaph of the destructive dragon”. In this context, Shoba and Mtapuri (Citation2022) implied that the notion of asymmetry in the relations between South Africa and China has been highly exaggerated in the media. However, Shoba and Mtapuri (Citation2022) did not dismiss the notion of asymmetry in these relations as they argued that despite this exaggerated notion, South Africa must place itself in a position to define the terms of engagement with China and put in place measures to demarcate such perceived asymmetry. The foregoing assertions demonstrate that the notion of asymmetry in the relationship between South Africa and China does exist regardless of whether it is perceived or exaggerated. However, it is evident that the relationship between the two countries will continue to evolve as the two remain committed to their engagements (Shoba & Mtapuri, Citation2022). However, it remains unclear to what extent such asymmetry relations between the two countries can be sustained, particularly in changing world politics.

Conclusion

This article presented an overview of how the relations between South Africa and China have evolved over the past decades, from the era of the National Party of South Africa and the Nationalist Party of China to the current dispensation of the Republic of South Africa and the Peoples Republic of China. In line with constructivism theory, both epochs of the relationship have been greatly shaped and influenced by the identities and interests of the prevailing era. Both countries have significantly changed individually, and that change has been followed by changes in their national interests, which aligns with the constructivism theory underpinning this review.

Throughout the different eras of the relationship between the two countries, there have been periods of perceived ‘distance’ between them, which was shaped by their different interests that existed at the time. For instance, this article has shown that, despite the rapid development of the relations between the two countries from normal state bilateral relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership, it was only in the wake of the election of Jacob Zuma as president of South Africa, that the level of engagements between the two countries was increased. The political interests of President Zuma converged with President Xi, which created an enabling environment for heightened cooperation between the two countries. This article has demonstrated that the increased cooperation between South Africa and China during President Zuma’s tenure resulted in China becoming South Africa’s main export market destination. As of 2011, China was last on the list of top five export market destinations for South Africa, with the US being top of the list, and in 2018 China moved to the top to become South Africa’s number one export and import market destination, as was shown in and . While this is something to celebrate for both countries, it is, however, concerning that the composition of South Africa’s exports to China is comprised mainly of natural resources and raw materials, which is a clear sign of a traditional economy.

This article has shown that China exports finished goods and products, to South Africa’s exports which are concentrated on raw materials. This has led to many criticisms being levelled against the relationship between the two countries as their relations have been characterised as asymmetrical in favour of China. However, there has been a growing school of thought from African decolonial scholars that seems to downplay the notion of asymmetry between the two countries. This has been in accordance with leaders from both South Africa and China who have incessantly lauded the relations between the two sides as mutually beneficial and win-win relations anchored on shared historical identities and interests. The overall observations based on the developments between South Africa and China suggest that the two sides will continue to advance their relations. This will be driven by an array of reasons, such as the need for South Africa to ensure an increase in the inflow of investments in the country and China’s continued requirements for natural resources from South Africa and the broader African continent for its developmental needs.

Acknowledgement

A major limitation of this study includes its conceptual nature. None of the conclusions made in this paper have been supported by quantitative or statistical analysis. So, most of the views are those of the authors. Also, this article did not necessarily cover other important aspects such as the participation of South Africa in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) even though South Africa was the first African country to sign a BRI memorandum of understanding with China in 2015. Finally, the authors wish to acknowledge that a substantial part of this article was developed from the first author’s doctoral thesis titled “Interrogating South Africa-China Relations in the Context of BRICS.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muzi Shoba

Muzi Shoba is a Lecturer at Nelson Mandela University. He holds a Ph.D. in Development Studies from the University of KwaZulu Natal.

Victor H. Mlambo

Victor H. Mlambo is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy at the University of Johannesburg. Victor holds a Ph.D. in Public Administration from the University of Zululand.

References

- Ado, A., & Su, Z. (2016). China in Africa: A critical literature review. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-05-2013-0014

- Akinola, A. O., & Tella, O. (2022). COVID-19 and South Africa-China asymmetric relations. World Affairs, 185(3), 587–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/00438200221102405

- Alden, C., & Park, Y. (2013). ‘Upstairs’ and ‘downstairs’ dimensions of China and the Chinese in South Africa. In U. Pillay, J. P. Jansen, F. Nyamnjoh, & G. Hagg (Eds.), State of the nation: South Africa 2012–2013 (pp. 643–662). Human Research Council.

- Alden, C., & Wu, Y. S. (2014). South Africa and China: The making of a partnership. South African Institute of International Affairs. Occasional Paper 199. South African Institute of International Affairs. https://saiia.org.za/research/south-africa-and-china-the-making-of-a-partnership/

- Anthony, R., Grimm, S., & Kim, Y. (2013). South Africa’s relations with China and Taiwan: economic realism and the ‘One China’doctrine. Centre for Chinese Studies, University of Stellenbosch.

- Bodomo, A. (2009). Africa-China relations: Symmetry, soft power and South Africa. China Review, 9(2), 169–178.

- Bond, P. (2013). Sub-Imperialism as a lubricant of neoliberalism: South African ‘deputy sheriff’ duty within BRICS. Third World Quarterly, 34(2), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.775783

- Bond, P. (2018). East-West/North-South–or imperial-sub-imperial? The BRICS, global governance and capital accumulation. Human Geography, 11(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861801100201

- Booysen, J. (2015, July 3). Imports killing SA’s textile industry. Independent Media. https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/economy/imports-killing-sas-textile-industry-1879877

- Checkel, J. (1998). The constructivist turn in international relations theory. World Politics, 50(2), 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100008133

- China Policy. (2017). China Going Global between ambition and capacity. https://policycn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-Chinas-going-global-strategy.pdf

- China-Africa Research Initiative. (2020). China-Africa Trade: China-Africa Bilateral Trade Data Overview. Johns Hopkins University. http://www.sais-cari.org/data-china-africa-trade

- Chiyemura, F. (2014). South Africa in BRICS: Prospects and constraints [Masters dissertation]. University of Witwatersrand.

- Chiyemura, F. (2019). The Winds of change in Africa-China relations? Contextualising African agency in 600 Ethiopia-China Engagement in Wind energy Infrastructure Financing and Development [Doctoral thesis]. The Open University.

- Coega Development Corporation (CDC). (2021). Coega congratulates FAW SA on achieving a significant milestone. https://www.coega.com/NewsArticle.aspx?objID=121&id=16780

- Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). (2014). Minister Nkoana-Mashabane in China to co-chair the first meeting of the South Africa-China inter-ministerial joint working group on cooperation. http://www.dirco.gov.za/docs/2014/chin0903.html

- Deych, T. L. (2018). China in Africa: A case of neo-colonialism or a win-win strategy? Outlines of Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, Law, 11(5), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.23932/2542-0240-2018-11-5-119-141

- Dullar, N. (1994). South Africa and Taiwan: A diplomatic dilemma worth noting. Africaportal. https://www.africaportal.org/documents/2466/South_Africa_and_Taiwan.pdf

- Edel, M. M., & Chan, W. Y. (2018). China in Africa: A form of neo-colonialism. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2018/12/02/china-in-africa-a-form-of-neo-colonialism/

- Fabricius, P. (2019). South Africa’s military drills with Russia and China raise eyebrows. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/south-africas-military-drills-with-russia-and-china-raise-eyebrows

- Feltman, J. (2020). China’s expanding influence at the United Nations—and how the United States should react. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FP_20200914_china_united_nations_feltman.pdf

- First Automobile Works [FAW]. (2014). FAW makes History in South Africa: Commercial vehicles. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC158470

- Grevatt, J., & MacDonald, A. (2022). China increases 2022 defense budget by 7.1%. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/china-increases-2022-defence-budget-by-71

- Gouvea, R., Kapelianis, D., & Li, S. (2020). Fostering intra-BRICS trade and investment: The increasing role of China in the Brazilian and South African economies. Thunderbird International Business Review, 62(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22098

- Grobler, G. (2021). Strengthening economic co-operation between South Africa and China. Retrieved May 11, from 2022, https://www.iol.co.za/news/opinion/strengthening-economic-co-operation-between-south-africa-and-china-1a74106f-e4e6-453d-9f6b-fd1258e4babf

- Hamill, J. (2018). Remembering South Africa’s catastrophe: the 1948 poll that heralded apartheid. https://theconversation.com/remembering-south-africas-catastrophe-the-1948-poll-that-heralded-apartheid-96928

- Jiang, L. (2021). South Africa–China relations of seven decades (1949–2019): Review and reflection. South Africa–China relations. Springer Nature.

- Jiang, L., & Shu, Z. (2019). ‘There was no real information about China in South Africa’: Revisiting the history of the establishment of diplomatic relations between South Africa and China (1950s–1990s). South African Journal of International Affairs, 26(3), 455–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2019.1663257

- Kansaye, I. (2021). Analysis of China-Africa relations: Historical development and current perspectives. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(2), 26–29.

- Khumalo, S. (2018). Eskom’s R33.4bn loan deal with China Development Bank. https://mg.co.za/article/2018-07-24-eskom-inks-r334bn-loan-deal-with-china-development-bank/

- Le Pere, G., & Shelton, G. (2007). China, Africa and South Africa: South-South co-operation in a global era. Institute for Global Dialogue.

- Lin, S. H. (2007). The relations between the Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa, 1948–1998 [Doctoral thesis]. University of Pretoria.

- MacLeod, A. (2022). When people say the West should support Taiwan, what exactly do they mean? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/when-people-say-the-west-should-support-taiwan-what-exactly-do-they-mean-186744

- Magubane, K. (2018). MPs grill Treasury over Eskom China loan ‘secrets’. The News24. https://www.news24.com/Fin24/mps-grill-treasury-over-eskom-china-loan-secrets-20181016

- Maizland, L. (2022). China and Russia: Exploring ties between two authoritarian powers. The Council on Foreign Affairs. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-russia-relationship-xi-putin-taiwan-ukraine

- Matambo, E. (2020). South Africa-China relations: A constructivist perspective. The Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 42(2), 63–86.

- Mengshu, Z. (2020). A brief overview of Alexander Wendt’s constructivism. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/05/19/a-brief-overview-of-alexander-wendts-constructivism/

- Moyo, S. (2016). Perspectives on South-South relations: China’s presence in Africa. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 17(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2016.1138615

- Mpungose, L. (2018). SA’s foreign policy: Towards greater strategic partnerships in a post-Zuma era. The Africa portal. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://www.africaportal.org/features/sas-foreign-policy-towards-greater-strategic-partnerships-post-zuma-era/

- Mureithi, C. (2022). Trade between Africa and China reached an all-time high in 2021. https://qz.com/africa/2123474/china-africa-trade-reached-an-all-time-high-in-2021/

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2022). NSDP/SDDS for the People’s Republic of China. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/nsdp/201508/t20150819_1232260.html

- Otele, O. M. (2020). Introduction. China-Africa relations: Interdisciplinary question and theoretical perspectives. The African Review, 47(2), 267–284.

- Schoeman, M. (2011). Of BRICs and mortar: The growing relations between Africa and the global south. The International Spectator, 46(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2011.549753

- Shivambu, F. (2014). South Africa’s negotiated transition from apartheid to an inclusive political system: What capitalist interests reigned supreme? [Masters dissertation]. University of Witwatersrand.

- Shoba, M. (2017). An assessment of South Africa’s membership in the BRICS formation in relation to IBSA and SADC [Masters dissertation]. University of Zululand.

- Shoba, M. (2022). The phenomenon of China Shops in South Africa: Development, entrepreneurship and social cohesion. African Renaissance, 19(1), 245–270.

- Shoba, M. (2023). Interrogating South Africa-China relations in the Context of BRICS [Doctoral dissertation]. University of KwaZulu Natal.

- Shoba, M. S. (2018). South Africa’s foreign policy position in BRICS. Journal of African Union Studies, 7(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.31920/2050-4306/2018/v7n1a9

- Shoba, M., & Mtapuri, O. (2022). An appraisal of the drivers behind South Africa and China relations. African Identities, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2022.2125364

- Songtian, L. (2018). China-South Africa relations serve the fundamental interests of our two countries and two peoples. Embassy of China in South Africa. http://za.china-embassy.org/eng/sgxw/t1611802.htm

- South African History Online (SAHO). (2015). The Nelson Mandela Presidency - 1994 to 1999. https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/nelson-mandela-presidency-1994-1999

- Sow, M. (2018). Figures of the week: Chinese investment in Africa. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2018/09/06/figures-of-the-week-chinese-investment-in-africa/

- Statistics of South Africa (StatsSA). (2022). Mid-year population estimates. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022021.pdf

- Stone, S. (2018). It’s not a new colonialism, it’s a win-win: Ramaphosa on China’s billions. City Press. https://www.news24.com/citypress/news/its-not-a-new-colonialism-its-a-win-win ramaphosa-on-chinas-billions-20180903

- Subban, V. (2022). Africa: China’s trade ties with the continent continue to strengthen. https://www.globalcompliancenews.com/2022/06/14/africa-chinas-trade-ties-with-the-continent-continue-to-strengthen

- Sun, Y. (2020). China and Africa’s debt: Yes to relief, no to blanket forgiveness. The Brookings Press.

- Taiwan Today. (1980). Taipei newspapers—Visitors from afar. Taiwan Today. https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=4&post=5278

- The Presidency. (2018). President Cyril Ramaphosa concludes State Visit to China. https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-concludes-state-visit-china-3-sept-2018-0000

- Thies, C. G. (2002). A pragmatic guide to qualitative historical analysis in the study of international relations. International Studies Perspectives, 3(4), 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1528-3577.t01-1-00099

- Torrens, C. (2018). Chinese investment in South Africa: Set for success, if common mistakes are avoided. https://www.controlrisks.com/our-thinking/insights/chinese-investment-in-south-africa#

- Trading Economics. (2018). South Africa imports from China. Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/imports/china

- Trading Economics. (2022). South Africa military expenditure. Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/military-expenditure#

- United Nations (UN). (1979). 2758 (XXVI). Restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations. Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/192054?ln=en.

- Uzodike, N. (2016). South Africa and BRICS: Path to a new African hegemony. In D. Plaatjies, C. Hongoro, M. Chitiga-Mabugu, T. Meyiwa, M. Nkondo, & F. B. Myamnjoh (Eds.), State of the nation 2016: Who is in charge? Mandates, accountability and contestations in South Africa (pp. 437–456). Human Research Council.

- Wenjun, C. (2018). Twenty years on, China-SA relations embrace a new chapter. The Business live, August 25. Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/world/asia/2018-09- 25-twenty-years-on-china-sa-relations-embrace-a-new-chapter/

- Williams, C., & Hurst, C. (2018). Caught between two Chinas: Assessing South Africa’s switch from Taipei to Beijing. South African Historical Journal, 70(3), 559–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/02582473.2018.1447986

- Winning, A. (2018, July 24). China’s Xi pledges $14.7 billion investment on South Africa visit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-china-idUSKBN1KE2A3

- Xiong, H. F. (2012). China-South Africa relations in the context of BRICS [Masters dissertation]. University of the Witwatersrand.

- Xuejun, T. (2012). Remarks by H.E. Ambassador Tian Xuejun at the South African Institute of International Affairs. http://za.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/sgxw/Achive/201207/t20120705_7689849.htm

- Zhang, D. (2022). China’s influence and local perceptions: The case of Pacific Island countries. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 76(5), 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2022.2112145