?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study examines perceived tenure security in Burkina Faso, focusing on socio-cultural factors, authority relations, state politics, and gender dynamics. It identifies challenges in tenure security despite legal reforms, emphasising the subjective nature of tenure security and its dependence on individual perceptions. The findings highlight significant disparities in perceived tenure security based on socio-cultural and gender factors, emphasising the need for policies that address these specific challenges and promote equitable access to land and property rights. This study contributes to understanding the complexities of tenure security in Burkina Faso and offers insights for policy formulation and implementation across similar geographical settings.

1. Introduction

Security of Tenure is the assurance that an individual’s land ownership will be acknowledged by others and safeguarded in cases of specific challenges (Palmer et al., Citation2009; Swallow, Citation2021). This certainty is subjective, as tenure security concerns people’s perceptions (Payne & Durand-Lasserve, Citation2012; Van Gelder, Citation2009; Citation2010). Rights of Tenure may include rights to make permanent improvements, transact, give, mortgage, lease, rent, and bequeath areas of exclusive use (Adams et al., Citation2003; Adams & Adams, Citation2001). In the development literature and interventions, the security of land tenure rights is consistently portrayed as critical for economic growth, poverty reduction, social cohesion, governance, and environmental management (Maxwell & Wiebe, Citation1998; Payne, Citation2001; Valkonen, Citation2021). When achieved through clear and enforced rights, tenure security creates incentives for investment, provides access to credit, facilitates land transfers, and revives informal assets, thus raising people out of poverty (Durand-Lasserve, Citation2006). However, the significance of long-term security has led many to contend that maximum security can exist exclusively when there is complete private ownership, as the duration for which rights can be maintained under such Tenure is not confined to a fixed period (Van Gelder, Citation2010).

People with insecure tenures are confronted with the possibility that competing claims will jeopardise their land rights and even result in eviction (Reale & Handmer, Citation2011). According to Maxwell and Wiebe (Citation1998), the lack of security of Tenure places a significant burden on households’ ability to obtain sufficient food and enjoy sustainable rural livelihoods. It has been claimed that only owners have secure rights (Toulmin, Citation2009). Tenants, for example, have an insecure tenure because they rely on their owner’s will (Feder & Feeny, Citation1991). The implication is that tenure security can only be achieved by reserving transfer rights, such as the right to sell and mortgage (Adams & Adams, Citation2001). While in some regions, the concept of security is synonymous with the right to sell or mortgage, this is not the case in others (Deininger & Jin, Citation2006; Feder & Noronha, Citation1987). People in parts of the world with community-based solid tenure regimes are thought to have tenure security, even if they do not want to sell their land or do not have the right to do so (Barnes, Citation2009; Katz, Citation2000). As a result, they may only be able to pass their land on to their heirs or only be able to sell it to other members of the community (Teklemariam & Cochrane, Citation2021; Ubink, Citation2009).

Burkina Faso has a long history of land interventions to achieve Tenure, but without challenges (De Zeeuw, Citation1997; Deinlnger & Binswanger, Citation1999). In 2009, the Government of Burkina Faso (GoBF) adopted Law 034-2009 along with related decrees and codes to provide a mechanism to secure customary land rights in rural and peri-urban areas and deliver land certificates (APFR) (USAID, Citation2016). However, after fifteen years of adopting the national rural land tenure security policy, ten years of implementing Law 034-2009 and two evaluations in 2014 and 2020, the main challenges remain (Observatoire National du Foncier au Burkina Faso, Citation2022). Regarding the generalisation of the land tenure security process in all communes of Burkina Faso, only around sixty (60) communes that benefited from the technical and financial support of externally funded projects have the ability to secure their land out of a total of 351 communes. Another challenge is the equitable access to rural land for all rural stakeholders, individuals, and legal entities under public and private law (women, youth, and internally displaced persons) (Observatoire National du Foncier au Burkina Faso, Citation2022).

Enemark et al. (Citation2014) argued that practices for securing Tenure have predominantly focused on the registration of rights and operations of land administration. However, these dominant practices do not address the factors affecting tenure security or people’s perceptions of it (Enemark, Citation2009; Valkonen, Citation2021). These determinants are authority relations, state politics, social dynamics, and belonging. Tenure is a matter of everyday politics that brings together a range of actors with their interests, perceptions, and abilities to use power (Valkonen, Citation2021). This demonstrates that while existing literature acknowledges the challenges of land tenure security in Burkina Faso, there is a notable gap in understanding the factors influencing citizens’ perceptions of tenure security and property rights protection. Previous studies, including Linkow (Citation2016), Bambio & Agha (Citation2018), and Coulibaly (Citation2022), have primarily focused on legal frameworks and broad indicators, leaving a need for a comprehensive investigation into the specific socio-cultural, historical, and institutional factors that shape individuals’ perceptions of land tenure security.

To bridge this gap, the study poses three key objectives. Firstly, it sought to explore the impact of socio-cultural elements, particularly family inheritance and community norms, on individuals’ perceived security of land tenure and property rights. Secondly, the study aimed to ascertain the extent to which issues with local and customary authorities contribute to variations in these perceptions. Lastly, it delved into the role of gender within the socio-cultural context of Burkina Faso, examining its influence on the perceived security of land tenure. To test these inquiries, the study formulates corresponding hypotheses. The first hypothesis posits that family inheritance significantly influences citizens’ perceived security of land tenure and property rights. The second hypothesis suggests that issues with local and customary authorities play a substantial role in shaping variations in perceptions of land tenure security. Lastly, the third hypothesis explores gender-based differences, proposing that gender plays a significant role in shaping Tenure’s perceived security. These research objectives and hypotheses collectively contribute to the study’s objective of understanding tenure security in Burkina Faso, thereby addressing critical gaps in the existing body of knowledge.

2. Review of literature

The concept of tenure security in Burkina Faso has been a subject of extensive theoretical and empirical debate. The relationship between tenure security and economic development hinges on the premise that secure property rights are fundamental for economic growth, investment, and poverty reduction.

2.1. Determinants of tenure security and property rights protection

The starting point for considering the determinants of tenure security is to recognise their institutional connections in institutional pluralism (Chigbu et al., Citation2019). The nexus to institutions first entails that to be secure, tenure rights must be recognised and enforced by social actors or institutions (Valkonen, Citation2021). Leach et al. (Citation1997) noted that what makes tenure rights different is their recognition by other social actors. These can be political, legal, and social institutions such as communities and state structures (Ho, Citation2014). These institutions can enforce rights based on custom, convention, law, economic or political influence, or even threats of force and violence (Monterroso et al., Citation2017; Stacey, Citation2018). According to UN-Habitat (Citation2003), ‘security of tenure’ illustrates a commitment between a person or group and land or residential property managed and controlled by a legal and administrative framework. The administrative state may provide general security through formal legal systems by affirming people’s rights and through specific measures such as protecting trespass. The security of Tenure often comes from protections provided through land registration and cadastral systems with the adjudication of disputes in the formal court system (Augustinus & Tempra, Citation2021; Hanstad, Citation1997). While such simplifications can be beneficial, it should be noted that the precise way land rights are allocated and enjoyed can be highly complex, as they are profoundly embedded in people’s perceptions.

Thus, tenure security is subjective and cannot be gauged directly because it relies on people’s perceptions. This recognition is based on assessing how socio-economic factors combine to influence perceived tenure security, such as awareness of rights or other individual, household, or property characteristics, level of education, marital status, and possession of formal documentation that can be viewed in court as evidence of Tenure and gender-differentiated effects on perceived tenure security (Alban & Willem, Citation2020; Ayamga et al., Citation2015; Valkonen, Citation2021). Other context-relevant factors that may contribute to perceived tenure security include individual-level characteristics (such as age or marital status), household-level factors (household size, number of children, low income), property characteristics (e.g. whether land or property is used productively), and respondents’ knowledge of how to protect land or property rights (Chris et al., Citation2011; Masuda et al., Citation2022).

Sources of perceived tenure security may vary from context to context (Valkonen, Citation2021). The security of a person increases when neighbours recognise and enforce the person’s rights (Sjaastad & Bromley, Citation2000). People gain property rights in many customary tenure arrangements through membership in social communities (Akaateba, Citation2019; Asaaga & Hirons, Citation2019). Holding property rights authenticates membership in the group in the same way that membership facilitates the acquisition and protection of property rights (Djurfeldt, Citation2020). It is commonly believed that the poor in a community have only used rights (FAO, Citation2002a). Tenure insecurity is particularly gendered during disputes that divide family land during spousal death or divorce scenarios (Feyertag, Citation2022; Feyertag et al., Citation2021; Fletschner et al., Citation2022). The authors also observed that widows and divorcees are highly vulnerable to tenure insecurity (Holden, Citation2021; Nara et al., Citation2021). Governments symbolise another source of tenure security as they may grant political recognition of certain rights (Emmanuel, Citation2017). For instance, the government may favour a community’s unlawful encroachment by allowing settlement on state lands. However, in doing so, the government typically acknowledges the community’s right to occupy property. However, it does not go so far as to recognise the rights of individuals within the community (FAO, Citation2002b).

In addition to being an institutional matter, tenure security sources are connected to social and power dynamics, which entail interactions between people, households, and communities (Han et al., Citation2019). Tenure security can be sought through interpersonal links and is connected to broader social entities (Bambio & Agha, Citation2018). Observing tenure relations in Ghana, Berry (Citation1997) found that tenure security is related to negotiation processes. She argued that the position of individuals in families, communities, and society at large defines the security of rights. Fortmann (Citation1995) maintains that property rights are constantly renegotiated in the dynamic process of telling stories and building discursive strategies to defend one’s position in Zimbabwe. For both Berry (Citation1997) and Fortmann (Citation1995), the audience and witnesses of narratives are essential in legitimising and protecting tenure rights. These concepts join Rose’s (Citation1994) definition of property as shared by common beliefs, understanding, and culture. For her, narratives were ways to persuade people of the common good of property regimes, ensuring that they were adhered to. Dynamic negotiation processes construct a sense of security within and between communities (Rose, Citation1994).

2.2. Review of empirical studies

The empirical literature on perceived tenure security and property rights offers a multifaceted view by integrating various socio-demographic variables. This section synthesises the findings from various studies that examine the interrelationships between location, gender, education, document classification, marital status, inheritance, local authority issues, conflict, and institutional trust in the judiciary.

Urban and rural differences in tenure perception have been extensively studied, with Dodman et al. (Citation2017) revealing that urban dwellers with formal property documentation exhibit markedly higher perceived security than their rural counterparts. This urban advantage is attributed to better access to formal registration systems and legal recourse. Similarly, Nara et al. (Citation2020) indicate that rural residents’ reliance on customary land rights often results in lower perceived security, compounded by prevalent local conflicts and terrorist activities.

The gendered aspect of property rights emerges as a critical area of inquiry. Giovarelli et al. (Citation2013) report that women, particularly in less urbanised areas, are disproportionately affected by a lack of access to formal property documentation, leading to diminished tenure security. This disparity is further explained by marital status, as expounded by Fayertag (2021), who observes that while married individuals generally enjoy heightened perceived security, the experiences of single, separated, divorced, or widowed individuals vary greatly, often disadvantaging women.

Educational attainment appears to correlate with perceived tenure security. Ghebru and Lambrecht (Citation2017) posit that individuals with higher educational levels are more likely to possess formal property documentation, thereby enhancing perceived security. However, USAID (Citation2013) offers a counter perspective, suggesting that educational attainment does not uniformly enhance understanding or utilisation of formal property rights mechanisms, particularly in conflict-prone regions.

The classification of property documentation significantly impacts perceived tenure security. Dachaga and de Vries’s (Citation2021) study delineates that formal documents confer a stronger sense of security than informal ones, consistent across various educational and gender demographics (Giovarelli et al., Citation2013).

The role of inheritance in tenure security is complex. A policy note by DFID (Citation2011) demonstrates that inheritance, whether from family or through marriage, often entails contested security, especially in the absence of formal documentation. This finding points to the intricate nature of traditional inheritance practices and their intersection with formal legal systems.

Interactions with local or customary authorities significantly sway perceptions of tenure security. Payne and Durand-Lasserve (Citation2012) elucidate that conflicts with local authorities are closely associated with reduced perceived tenure security, a phenomenon observed across gender and education spectrums.

Lastly, trust in judicial institutions emerges as a fundamental factor influencing perceived tenure security. Robinson et al. (Citation2018) analysis suggests that confidence in legal institutions is essential for the enforcement of property rights and the resultant perception of security among property holders.

The review of empirical literature suggests that perceived tenure security and property rights protection are contingent upon a constellation of factors, including but not limited to location, gender, education, legal documentation, and institutional trust. Drawing on the empirical studies regarding tenure security and property rights, our research delves into the details of property rights perceptions within Burkina Faso. We examine various factors, including socio-demographic influences, legal documentation, gender dynamics, educational backgrounds, inheritance customs, civic engagement, and confidence in judicial systems. The study aimed to extract profound insights from empirical data that can inform policy recommendations and interventions.

2.3. Theoretical review and conceptual framework

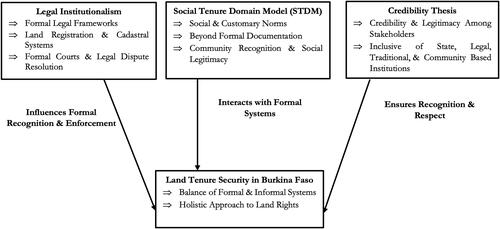

2.3.1. Legal Institutionalism

Legal Institutionalism is a theory within the field of legal studies that emphasises institutions’ role in shaping the law and legal outcomes (Deakin et al., Citation2017). It differs from legal formalism, which focuses on logical and systematic interpretations of the law, and legal realism, which emphasises the influence of external factors like social, economic, and psychological pressures on legal decisions (Cox, Citation2003). Applicable insights from this theory suggest that formal legal systems provide tenure security by affirming rights and protection against trespass. The presence of land registration and cadastral systems and the ability to adjudicate disputes in formal courts are central to this approach. It emphasises the importance of formal recognition and enforcement of property rights as the basis for tenure security (Hanstad, Citation1997; Van Gelder, Citation2009).

In Burkina Faso, a country with a strong presence of customary land tenure systems (Sawadogo & Stamm, Citation2000), Legal Institutionalism focuses on the role of formal institutions in shaping the laws and outcomes related to tenure security. While customary systems are predominant, legal Institutionalism would argue for the strengthening and clarifying formal legal frameworks to provide clear affirmation of rights and protection against trespassing. Developing land registration and establishing judicial mechanisms to adjudicate disputes would be emphasised as a means to reinforce tenure security. This approach recognises the importance of formal recognition and enforcement of property rights, suggesting that alongside traditional practices, there should also be a formalised system that can provide a universal standard of tenure security in Burkina Faso, bridging the gap between customary and statutory law.

2.3.2. Social Tenure Domain Model

The Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) is a concept from the land administration field, specifically within the domain of land rights management (Bartholomew et al., Citation2017). It is a framework that bridges the gap between formal and informal land rights and tenure arrangements. This model looks beyond the legal documentation and formal systems to include a range of tenure systems recognised through social or customary norms (Babalola & Hulla, Citation2022). It acknowledges that tenure security can also be derived from social legitimacy and the recognition of property rights by the community and other social actors (FAO, Citation2002a).

This model is important for understanding tenure security in contexts where customary land tenure systems are predominant (Griffith-Charles, Citation2011). In this regard, the model is pertinent within the context of Burkina Faso, where customary land tenure systems predominate, and the formal legal documentation of land rights is not widespread (Séogo & Zahonogo, Citation2023). This model acknowledges and documents a variety of tenure systems recognised through social and customary norms rather than solely formal legal titles (Berry, Citation1997). In a country where social legitimacy and community recognition are essential for tenure security, the STDM offers a flexible and inclusive framework that respects local customs and practices. It thus plays a key role in recognising diverse land rights, aiding in conflict resolution, and empowering communities by capturing the complex social relationships that underpin land tenure in Burkina Faso.

2.3.3. Credibility Thesis

The Credibility Thesis is a concept from institutional economics, particularly associated with the work of economist Elinor Ostrom (Forsyth & Johnson, Citation2014). It suggests that for an institution to be effective, it must be deemed credible by its participants. This scenario suggests that for tenure security to be effective, it must be credible to all actors involved. This involves recognition and enforcement by various institutions, including state and legal frameworks and traditional and community-based institutions. Tenure security arises from the interplay of politico-legal-social institutions capable of enforcing rights based on custom, convention, law, or economic and political influence (Monterroso et al., Citation2017; Valkonen, Citation2021).

In Burkina Faso, where customary land tenure systems are deeply entrenched, the Credibility Thesis implies that for tenure security to be effective, it must be recognised as credible by all local actors, including formal state and legal institutions and traditional and community-based entities. The effectiveness of tenure security hinges on the interplay of various politico-legal-social institutions that can enforce rights based on an involved mix of custom, convention, law, and socio-economic factors. This interweaving of formal and informal systems ensures that land tenure security in Burkina Faso is not solely reliant on formal documentation but is also grounded in the social legitimacy conferred by communal practices and traditional governance, reflecting a shared understanding and respect for local customs that govern land rights ().

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

Source: Musah et al., Citation2024.

The conceptual framework integrates the Legal Institutionalism, the STDM, and the Credibility Thesis to offer a comprehensive lens to understand the nature of tenure security in Burkina Faso, particularly in light of the empirical findings from various studies. Legal Institutionalism’s focus on formal legal systems and land registration is particularly relevant in urban areas, as evidenced by the higher perceived tenure security among urban dwellers with formal property documentation (Dodman et al., Citation2017). This contrasts with the rural context, where reliance on customary land rights, especially among women, leads to lower perceived security due to limited access to formal documentation (Nara et al., Citation2020). The importance of formal documentation in enhancing perceived security across various demographics is a key insight from this theoretical perspective.

The STDM’s emphasis on social and customary norms aligns with the complex nature of traditional inheritance practices and their impact on tenure security, highlighting the need for a framework that respects and integrates these practices. The Credibility Thesis underscores the significance of trust in judicial institutions and the impact of local authority conflicts on perceived tenure security, emphasising the role of credibility among all stakeholders, including legal, traditional, and community-based institutions. The framework underscores the multifaceted nature of land tenure security in Burkina Faso, influenced by several factors, including socio-demographic influences, legal documentation, gender dynamics, and institutional trust.

3. Property Rights Index (prindex) initiative

Prindex, the Global Property Rights Index, is an initiative designed to measure citizens’ perceptions of the security of their property rights. It provides a global perspective on how secure people feel about their land and property rights, assessing factors such as the likelihood of losing these rights, confidence in legal systems protecting these rights, and the prevalence of land and property documentation.

The Prindex encompasses key components to assess property rights security globally. It includes the Perception of Tenure Security, evaluating individuals’ confidence in their land and property rights and their likelihood of losing these rights. The Legal Framework and Enforcement component examines the effectiveness of legal systems in protecting these rights and the efficiency of law enforcement. The Land and Property Documentation aspect focuses on the prevalence and reliability of crucial documents like titles and deeds. Prindex also addresses Gender and Property Rights, highlighting gender disparities in the perception and reality of property rights security. Additionally, it explores the Impact of Property Rights on Economic and Social Outcomes, analysing how secure property rights influence broader developmental goals. Lastly, Comparative Analysis offers a global perspective by comparing property rights security across countries and regions.

A unique aspect of the Prindex data is its focus on individual rather than household-level perceptions. This approach is significant as it addresses a gap in many studies that only consider property rights at the household level, often represented by the household head. Such traditional methods may overlook the rights held by other household members, leading to a skewed understanding of tenure security (Feyertag, Citation2022). Prindex data, however, are collected from a country-representative sample of individuals aged 18 years or over. This method randomly selects adult household members, providing a more nuanced view of tenure security across different household groups.

4. Data and methodology

4.1. Data

Publicly available cross-sectional datasets from the Prindex comprising 575 men and 686 women were accessed and analysed to investigate the perceived tenure security and property rights among individuals in Burkina Faso. Prindex employs random and stratified sampling techniques in its surveys, ensuring a representative and comprehensive data collection on property rights perceptions. The numbers of men and women in the sample reflect diverse demographic perspectives, particularly ensuring a balanced gender representation. This stratified sampling approach is essential for understanding the differences in property rights perceptions across genders.

The age criterion for Prindex’s surveys typically targets adults, meaning the individuals in the dataset were aged 18 years or over. This criterion ensures that the data reflects the perceptions of legally recognised adults likely to have direct experience or knowledge regarding property rights issues.

Furthermore, Prindex’s methodology ensures geographical diversity in its sampling. Therefore, the data used in our study included responses from individuals across various regions of Burkina Faso. This geographical spread is essential for capturing the diverse experiences and views between urban and rural populations or among different ethnic and cultural groups within the country.

4.2. Measure

The response variable for this study was the perceived property rights protection. The analysis provides information regarding perceived property rights protection using the following predictors: location, gender, age, marital status, educational background, employment status, formal documentation, inheritance, institutional trust, customary issues, conflict, and terrorism. The outcome variable was the respondents’ rating of their perceived property protection in Burkina Faso. The principal question used to measure perceived tenure security and property rights protection aligns with the global efforts to track SDG 1.4.Footnote1 and are phrased as follows:

In general, how well do you think people in this country are protected regarding their property rights?

The explanatory variables examined in the study were selected based on previous studies adjusted to Prindex’s data. In this study, the variables of location, gender, age, educational background, document classification for all properties, marital status, inheritance from family, inheritance through marriage, issues with local/customary authorities, institutional trust, conflict, and terrorism were considered.

4.3. Method of statistical data analysis

In this study, 1260 respondents were included in the analysis. The chi-square test examined the relationship between qualitative independent and response variables. In addition, descriptive statistics and ordinal logistic regression analysis were used to overview the sample’s characteristics and identify the factors associated with perceived property rights protection. Logistic regression can determine the relationship between one response variable in categorical data (nominal or ordinal) and two or more explanatory variables. For example, suppose that the response variable is ordinal data of three or more categories. In this case, an ordinal logistic regression model is useful for this relationship.

4.4. Proportional odds model

This study used an ordinal logistic regression approach with cumulative logit and proportional odds models. The logistic regression model was chosen for our study due to its suitability for categorical outcome variables, ability to handle non-linear relationships, and usefulness in predicting probabilities and estimating odds ratios. These features made it an ideal choice for analysing the complex relationships inherent in data on perceptions of property rights and tenure security.

The proportional odds model is a generalised linear model used to model the dependence of an ordinal response (Ordered Categorical Data) on discrete or continuous covariates. The proportional odds model studies the effects of factors and covariates on an ordinal response variable (McCullagh, Citation2005). In estimating the model, it is important to distinguish clearly between response variables, on the one hand, and explanatory factors or covariates, on the other. Suppose the k-ordered response categories have probabilities when covariates have a value

. In the case of two groups,

is an indicator variable or a two-level factor that indicates the appropriate group. Let Y be the response that takes values in the range of 1,…, k with the probabilities given above, and let

be the odds that

given the covariate values

. Then, the proportional odds model specifies that

…………………………………………1.1

…………………………………………1.1

where

is a vector of unknown parameters. The ratio of corresponding odds

……………………………………….1.2

……………………………………….1.2

is independent of

and depends only on the difference between the covariate values,

. Because the odds for the event

is the ratio

where

=

the proportional odds model is identical to the linear logistic model.

……………………………………….1.3

……………………………………….1.3

When The, the difference between the corresponding cumulative logits is independent of the category involved. In particular, when only two response categories exist, equation (1.3) is equivalent to the usual linear logistic model for binary data (McCullagh, Citation1980). In this case, it is equivalent to a log-linear model. However, when the number of categories exceeded two, the linear logistic model (1.3) did not correspond to a log-linear structure.

The parameters in the ordinal logistic regression model can be estimated using a Maximum Likelihood Estimation method by maximising the likelihood function (Greene, Citation2004). A proportional odds assumption of the ordinal regression model was then applied. The proportional odds assumption states that the ‘slope’ estimate between each pair of outcomes across two response levels is assumed to be the same for each term included in the model, regardless of which partition is considered (Kim, Citation2003). The proportional odds assumption was tested using a Likelihood Ratio Test (i.e. Test of Parallel Lines), which compared the fitted location model to a model with varying location parameters. The likelihood of the model is evaluated to determine whether all the estimated regression coefficients contained in the model are zero at the same time. The Wald test determines whether a single explanatory variable affects a response variable. For example, gender is the explanatory variable, and perceived property rights protection is the response variable. The hypotheses are as follows: (i) : Perceived property rights and gender are independent or unrelated (

:

= 0); and (ii)

Perceived property rights and gender are related or dependent on each other (

:

≠ 0);). All data analyses were performed using SPSS software (v26).

5. Results and discussions

5.1. Cronbach’s Alpha test for scale reliability

Determining Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was necessary to ensure the reliability and internal consistency of the scale used in our study. It provided a foundation of confidence in the data, which was essential before moving forward with more complex analyses and concluding the study findings.

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient for the four-category ordinal scale (refer to ) used in the study is 0.82. This value is considered to be an indicator of high reliability. Cronbach’s Alpha values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater internal consistency and reliability of the scale. A value above 0.7 is generally accepted as demonstrating good reliability, and a value above 0.8 is considered excellent (Gliem & Gliem, Citation2003).

Table 1. Cronbach’s Alpha Test for scale reliability.

Reliability Statistics

The high Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.82 in this study suggests that the four-category ordinal scale used to measure perceptions of property rights and tenure security is highly reliable. This indicates that the scale items are consistent in their measurement and that the responses across these items are coherent and stable. Therefore, the findings based on this scale are robust and reliable, providing confidence in the conclusions drawn from the analysis of the Prindex survey data.

5.2. Descriptive statistics

provides summary statistics for the variables used in the analysis. A total of 1,260 respondents from rural and urban populations were surveyed to measure their perceptions of tenure security and property rights in Burkina Faso. Of the 1,260 respondents in this study, 283 (22.5%) were surveyed in urbanised areas, while 977 (77.5%) were rural dwellers. About 574 (46.0%) were men and 666 (54.0%) were women. Concerning the age of participants, a large proportion, about 61% (769) of study subjects were in the age group between 18 and 35 years, followed by 315 (25%) of participants who were between the ages of 36 and 55 and 176 (14%) over 56 years. Out of the total, 1,134 (90%) respondents had completed elementary education or less of up to eight years of basic education, of which 294 (86%) perceived tenure security and property rights as not being well protected. However, secondary (3-year Tertiary/Secondary education) and higher education (four years of education beyond high school and/or received a 4-year college degree) were 110 (8.9%) and 15 (1.2%) of which 42 (12.3%) and 6 (1.8%), respectively, perceived their security tenure and property rights not well protected. Regarding the documentation of properties, 675 (54%) did not have existing documents on property claims, 448 (36.3%) possessed formal documents existing for at least one property, and 40 (3.2%) had informal documents that only existed for at least one property. Regarding the marital status of the respondents, 836 (66.3%) were married, of which 495 (69.8%) asserted that their tenure security and property rights were somewhat well-protected. Among those who were single, 305 (24.2%), separated, 30 (2.4%), divorced, 8 (0.6%), and widowed, 81 (6.4%) categorised their perceived tenure security and property rights as 21.7%, 1.8%, 0.6%, and 6.1% somewhat well-protected, respectively. The majority, 1,166 (92.5%), were employed, while 94 (7.5%) were unemployed. About 453 (88.1%) felt their tenure security and property rights were very well-protected amid conflict or terrorism, whereas 61 (11.9%) feared otherwise due to conflict or terrorism. In addition, about 53 (35.8%) perceived their tenure security and property rights as not well protected due to issues with local and customary authorities, as opposed to 95 (64.2%) who claimed otherwise. A nearly equal proportion of respondents in both categories, 476 (47.7%), did not trust the judiciary to adjudicate justice in periods of disagreement about tenure security and property rights, and 521(52.3%) trusted the judiciary. Regarding the source of property rights, 320 (47.5%) were inherited from their families, whereas 354 (52.5%) acquired property from other sources.

5.3. Inferential statistics

Perceived tenure security and property rights protection was the response variable. This is broken into four levels of ratings (not protected at all, not well-protected, somewhat well-protected, and very well-protected) to describe the four places that respondents perceive their security of tenure and rights protection. Accordingly, 79 (6.4%), 343 (27.8%), 709 (57.5%), and 103 (8.3%) participants rated their level of perceived tenure security and property rights as not protected at all, not well-protected, somewhat well-protected, and very well-protected, respectively. From the chi-square analysis (), the age and employment status covariates did not significantly correlate with perceived tenure security and property rights protection. Therefore, they were excluded from ordinal regression model estimations. However, it was observed that the covariates of location, gender, education, marital status, family inheritance, inheritance through marriage, issues with local/customary authorities, conflict or terrorism, institutional trust, and document classification showed a significant association with perceived tenure security and property rights protection.

Table 2. Summary statistics of the respondents’ profile.

Analysis of the ‘Summary statistics of the respondents’ profile’ () involved interpreting the distribution of respondents across various categories and their corresponding levels of perceived tenure security and property rights protection. The table also presents p-values to indicate the statistical significance of the differences observed across categories for each variable.

The analysis of tenure security perceptions among participants revealed stark differences based on location. Urban respondents (22.5%) reported feeling unprotected regarding their property rights, likely due to the volatile nature of urban real estate and development pressures. This sentiment of insecurity is statistically significant, with a p-value of less than .0001, highlighting a pronounced disparity compared to rural respondents. About 77.5% of rural inhabitants, generally felt their tenure security was either somewhat or very well-protected. This sense of security could be connected to the more stable, traditional land ownership patterns in rural settings, where land transactions are infrequent and transparent (Coulibaly, Citation2022). These findings resonate with the perspective of legal Institutionalism, suggesting that the efficacy of legal systems in safeguarding tenure security varies by setting, with urban areas lagging behind in adapting to rapid changes. In contrast, the STDM might better represent the rural context, where a variety of tenure systems, including those based on social legitimacy, are recognised and contribute to a higher sense of security (Sawadogo & Stamm, Citation2000). The outcomes align with existing research that notes the erosion of tenure security among urban dwellers due to urbanisation and gentrification (Porio & Crisol, Citation2004), yet stand in contrast to some studies that have found rural areas to exhibit lower tenure security (Brasselle et al., Citation2002), potentially reflecting local variations in land tenure management and the strength of governance structures.

The examination of the impact of gender on perceptions of tenure security presents findings that challenge some conventional narratives in property rights literature. The results demonstrate that males (46%) were more likely to feel less protected in terms of their property rights, either categorising their situation as ‘not protected at all’ or ‘not well-protected’. In contrast, females (54%) exhibited a higher sense of security regarding their property rights. The statistical analysis, yielding a p-value of .030, confirms the significance of this gender difference in perceptions of tenure security. The interpretation of these results suggests that females feel more secure in their property rights than males. This could reflect recent policy efforts and legal reforms to enhance women’s property rights and address historical gender imbalances in property ownership and control (Observatoire et al. au Burkina Faso, 2022). Such policy initiatives might have contributed to an increased sense of security among women regarding their tenure rights. When comparing these findings with existing studies, we observe a notable alignment with research like Han et al. (Citation2019), which reported a similar trend of higher perceived security among women. This could be attributed to targeted gender policies and societal shifts that increasingly recognise and support women’s property rights. However, our findings diverge from the broader trend observed in other literature, such as Owoo and Boakye-Yiadom (Citation2015), where women typically feel less secure in their property rights. This discrepancy might be due to regional or cultural differences or indicate a shift in trends owing to evolving legal frameworks and societal attitudes towards gender equality in property rights.

The study delineates the role of formal documentation in the perception of tenure security. The analysis reveals a striking contrast in the perceptions of tenure security between respondents with and without formal documentation. A significant portion, 54.7%, who lacked formal documents reported diminished security regarding their property rights. Conversely, those possessing formal documents, such as land titles or property deeds, exhibited a markedly higher sense of security. This divergence in perceived security, underscored by a p-value of less than .0001, highlights the profound impact of formal documentation on individuals’ confidence in their property rights. The interpretation of these findings aligns with the theoretical underpinnings of Legal Institutionalism, which emphasises the role of formal legal systems, including documentation and registration processes, in providing tenure security. This theory underscores the importance of legal frameworks in affirming property rights and the critical role of formal recognition in enhancing individuals’ confidence in these rights. The results also resonate with the STDM, which, while acknowledging a broader range of tenure systems, recognises the significance of formal documentation in certain contexts. This alignment with STDM suggests that while formal documentation is imperative, it should be considered within the broader context of varying tenure systems. These findings align with global trends, such as those reported in studies like Ghebru and Lambrecht (Citation2017), where formal land titles or property documents are strongly correlated with perceived tenure security. This pattern reflects the universal importance of legal documentation in establishing and reinforcing property rights. However, the emphasis on formal documentation may contrast with findings from regions where customary or informal tenure systems are predominant, and formal documentation is not the primary source of tenure security (Ababa, 2004).

In exploring the impact of marital status on perceptions of property rights and tenure security, our study reveals a significant correlation between marital status and the sense of security in property rights. Married individuals tend to feel more secure in their property rights than single or separated individuals. This finding, substantiated by a p-value of .007, underscores the influence of marital status on perceptions of tenure security. The interpretation of these results suggests that marriage’s legal and social stability contributes to a heightened sense of security in property rights (Nakanwagi, Citation2022). Marriage often involves a legal framework governing property ownership and inheritance, providing a sense of certainty and security. This legal aspect, combined with the social support structures typically associated with marriage, appears to bolster the confidence of married individuals in the security of their property rights. These findings resonate with the concepts of Legal Institutionalism and the STDM. Legal Institutionalism emphasises the role of formal legal structures in property rights, which can be particularly relevant in marriage and its legal implications on property ownership.

Meanwhile, STDM, which recognises the importance of social and customary norms in land tenure, aligns with the observation that social aspects of marriage can influence perceptions of property rights security. Furthermore, the trend observed in our study aligns with findings from other research, such as Doss and Meinzen-Dick (Citation2020), which also noted an enhanced sense of perceived tenure security among married individuals, particularly in cultures where property rights are intertwined with family structures. This consistency highlights the broader applicability of our findings, though it is important to acknowledge that cultural and legal variations might influence the extent of this correlation (Owoo & Boakye-Yiadom, Citation2015).

The results further show that inheritance, whether from family or through marriage, significantly impacts individuals’ sense of security in property rights. The result shows varied perceptions of security among those who have inherited property, with significant p-values of .006 and .037, respectively, for inheritance from family and through marriage. This variation underscores inheritance’s role in shaping perceptions of property rights security. The interpretation of these findings suggests that inheritance is more than just a property transfer; it is a central factor in perceived tenure security. The importance of familial ties in property rights is highlighted, indicating that how property is acquired, especially through familial channels, can significantly influence an individual’s sense of security over their property. This observation is particularly relevant in cultures where property rights and family lineage are closely intertwined. The results align with studies (Takane, Citation2008), which emphasise the role of family lineage in property security. This alignment suggests a traditional view where inheritance is a key factor in ensuring tenure security, resonating with the STDM that recognises the importance of social and customary norms in land tenure systems. However, our findings contrast with studies like Payne and Durand-Lasserve (Citation2012), where the influence of modernisation has seemingly diminished the role of inheritance in tenure security. This contrast could indicate a shift in property rights perceptions in more modernised societies, where legal frameworks and individual rights may take precedence over familial and traditional modes of property transfer. Such a shift could align with the principles of Legal Institutionalism, which emphasises the role of formal legal structures in property rights.

The study reveals a significant impact of local or customary authorities and experiences of conflict or terrorism as contributory factors influencing perceptions of tenure security. Issues with local authorities and experiences related to conflict or terrorism profoundly affect individuals’ perceptions of security, as evidenced by the p-values of less than .0001 and .002, respectively. This finding highlights the role of governance, stability, and local power dynamics in shaping perceptions of property rights security. This suggests that the quality and nature of governance, as well as the presence of conflict or terrorism, are pivotal in determining how secure individuals feel about their property rights. Issues with local authorities might reflect broader concerns about governance quality, legal enforcement, and the protection of property rights.

Similarly, experiences of conflict or terrorism can exacerbate feelings of insecurity, as they often disrupt social and economic structures, leading to uncertainty over property rights and tenure security. The significant impact of local authorities and conflict on perceived security echoes the findings of studies such as Payne and Durand-Lasserve (Citation2012), which emphasised the direct influence of governance quality on property rights perceptions. This alignment is consistent with the principles of Legal Institutionalism, which underscores the importance of effective legal and governance structures in ensuring property rights security. However, our findings diverge from studies like Locke et al. (Citation2021), where the impact of local authorities on tenure security was found to be less pronounced. This contrast might be attributed to regional differences in the role and effectiveness of local authorities, or it could reflect varying degrees of institutional trust and governance quality across different contexts.

Our study delves into institutional trust, particularly focusing on the judiciary and its influence on perceptions of tenure security. The findings reveal that trust in the judiciary significantly impacts how individuals perceive the security of their property rights, as indicated by a p-value of less than .0001. This underscores the role of judicial systems in shaping individuals’ confidence in protecting their property rights. The results highlight the importance of the judiciary in ensuring property rights. Trust in judicial systems is not merely about the effectiveness of legal proceedings but also about the broader perception of fairness, impartiality, and the ability of these systems to uphold and protect property rights. In societies where the judiciary is trusted, individuals are likely to feel more secure about their property rights, as they believe in the system’s capacity to enforce laws and resolve disputes effectively. When we compare these findings with existing literature, we see a clear alignment with global trends. Studies like Odeny (Citation2013) have emphasised the importance of legal systems, particularly the judiciary, in shaping perceptions of property rights. This global pattern reflects the universal importance of trust in legal institutions in establishing and reinforcing property rights. However, it is important to note that the level of trust in the judiciary can vary significantly across different contexts, influenced by factors such as historical experiences, cultural norms, and the overall quality of governance (Nunn, Citation2012). In regions where the judiciary is perceived as corrupt or ineffective, the impact on property rights perceptions can be markedly negative.

5.4. Proportional odds model estimates

shows the results of the Wald chi-squared test for each explanatory variable. Wald is a parametric statistical measure used to confirm whether a set of independent variables is collectively ‘significant’ for a model. We also confirmed whether each independent variable in the model was significant. The Wald Chi-Square test is used to test verses

; if the null hypothesis is rejected, the log odds for each cumulative probability is larger or smaller with xr depended on the sign of

. The results of the Wald test on each explanatory variable yielded 6 significant variables of the 10 explanatory variables. The results indicated that the covariates of gender, marital status, inheritance from family, issues with local/customary authourities, conflict or terrorism, and institutional trust were significant at a 0.05 level of significance using the multivariable POM, indicating that these were the critical deterministic factors for perceived tenure security and property rights in Burkina Faso. Based on , the p-value values of location, education, and document classification for all properties and inheritance from marriage were significant at 0.05, indicating these variables were insignificant in affecting the perceived tenure security and property rights. The probability score test for the proportional odds assumption is insignificant at 0.05, indicating that the data meets the assumption.

Table 3. Parameter estimates of POM using perceived tenure security property rights protection as response with four-ordered categories.

Table 4. Collinearity statistics.

This study used an ordinal logistic regression model to identify the factors associated with perceived tenure security and property rights under the ordered categories in Burkina Faso. The findings revealed that of the 1,260 respondents, 79 (6.4%), 343 (27.8%), 709 (57.5%), and 103 (8.3%) rated their level of perceived tenure security and property rights as not protected at all, not well-protected, somewhat well-protected, and very well-protected, respectively. This suggests that over one-third of the participants felt their tenure rights were not safeguarded. Furthermore, the study also revealed that based on the final POM, gender, marital status, inheritance from family, issues with local/customary authorities, conflict or terrorism, and institutional trust were statistically significant factors of the perceived tenure security and property rights.

Achieving gender equality implies, among other things, giving women access to and control over resources to enable them to benefit equally from sustainable development. The results of the ordinal logistic regression () showed that the gender of a household member was a statistically significant factor in the perceived security of tenure and property rights protection. A prior study that assessed how gender affects the perception of land and property rights security in 33 countries (Feyertag et al., Citation2021) found that men’s and women’s perceived tenure security did not differ significantly. However, significant in-country differences exist, which can partly be explained by gender-differentiated sources of insecurity. In affirmation of their findings, this study found that women were less likely to be insecure than men in Burkina Faso. The estimated odds ratio (OR = 0.56, 95% CI, –1.049 to –0.127) indicated that male household members were 0.56 times less likely to have a higher sense of perceived tenure security and property rights than female household members, holding all other variables constant.

This can be attributed to recent efforts to improve women’s access to resources through locally led and culturally sensitive processes, particularly in rural Burkina Faso. A previous study reported that access to land and property is essential for food production (Pehou et al., Citation2020). Insecure access to land, therefore, enforces a gender gap in agriculture. Gender-based inequality can severely affect rural communities in agriculture-dependent countries, such as Burkina Faso, where women play a critical role in agricultural production. A growing body of evidence has demonstrated a strong relationship between land tenure and food insecurity. As such, enabling women to acquire land security could play a central role in rural development activities (Séogo & Zahonogo, Citation2023). This will achieve positive changes in several related areas, such as economic empowerment, combating infant and child malnutrition, and reducing vulnerability to domestic violence (Allendorf, Citation2007). Nonetheless, men control land management in rural areas where traditional practices dominate. As a result, women are served last, and there are no guarantees that they can farm a plot of land over the long term (Emmaüs International, Citation2021).

Moreover, marital status was also reported as a key factor determining household members’ security of tenure and property rights, especially for those who were separated. Nara et al. (Citation2021) observed that widows and divorcees were highly vulnerable to tenure insecurity. The estimated odds ratio (OR = 0.18, 95% CI, -3.354 to -0.067) indicated that those separated had a 0.18 times cumulatively lower perceived security of tenure and property rights protection than those who were widowed. Likewise, those who were single (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: –0.908 to 0.968) and divorced (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: –1.724 to 2.067). Marital status tends to safeguard both men’s and women’s rights to tenure security and property rights. However, in many scenarios, women are most affected when there is separation, divorce, or death of their husbands. A prior study found that millions of women worldwide lost their rights to property following their husbands’ deaths (Korang-Okrah et al., Citation2019).

Similarly, access to land and property is essential for most women’s sustainable livelihoods, which depend on their natal and marital affiliations (Giovarelli et al., Citation2013). In Burkina Faso, the land is family-owned and distributed to individuals by male family members, who often see the allocation of land to women as a financial loss (Communication Initiative Network, Citation2015). However, women continue to gain access to land through their husbands, who, by custom, are required to make a portion of their agricultural plots available to their wives (Kevane & Gray, Citation1999; Africa.com, Citation2015). Thus, women can lose their right to land when there is a change in marital status due to marriage, divorce, or the death of a spouse. These implications imply that women are presumably at risk of internal sources of insecurity from within the family or community, especially when confronted with divorce or spousal death scenarios over the anticipated duration of their Tenure.

Conflict and/or terrorism appeared to be an important indicator of citizens’ perceptions of safeguarding their tenure and property rights security. The estimated odds ratio (OR = 0.47, 95% CI, -1.437 to -0.080) suggested that the ordered odds of subjects who were not worried about losing their rights of Tenure and property had 0.47 times less of perception regarding their security of tenure and property rights protection as compared to those who feared the security of their tenure and property rights due to conflict or terrorism, keeping all other covariates fixed. In other words, those who were more concerned that their right to Tenure and property was threatened due to conflict or terrorism had higher levels of perception about losing their security of tenure and property rights compared to their counterparts who exhibited less concern. Violent extremism and conflict remain among Burkina Faso’s most pressing security threats. The country has been increasingly exposed to threats and attacks from violent armed groups. Over a million Burkinabese have lost their tenure or property rights security because of indiscriminate attacks against civilians (Okafor et al., Citation2023). Conflicts between farmers and herders over water availability and grazing have persisted for decades (Garner, Citation2022). The State of Emergency was renewed twice, in January 2020 and June 2021, due to escalated tensions of insecurity. The violent extremist threat in northern Burkina Faso exploits the underlying societal vulnerabilities of inequity, insecure land rights, and distrust of the authorities. Sub-Saharan Africa faces several complex threats to its peace and security, stemming from the interplay between various factors. For instance, resource competition, Islamist terrorism, ethnic tensions, crime, violence (cross-border), and conflicts have weakened Burkina Faso’s peace and security (Gaye, Citation2018).

As Augustinus and Tempra (Citation2021) noted, the formal legal system may provide general security by affirming people’s rights. However, people with insecure tenure risk competing claims threatening their land rights and may even be lost due to unfair or illegal eviction (Reale & Handmer, Citation2011). During these periods, the country’s legal land administration regime should be able to adjudicate disputes freely and fairly, of which both parties are fully convinced. Given this scenario, trust in the judicial system was identified as a critical factor in determining household members’ security of tenure and property rights protection. The estimated odds ratio (OR = 0.53, 95% CI, -1.054 to -0.202) indicated that those who were not worried about losing their rights of tenure security and property because of a lack of equity in the adjudicatory processes had 0.53, cumulatively lower perceived security of tenure and property rights protection than those who revealed their worry about losing their rights of Tenure and property because of the lack of trust in the judiciary to adjudicate fairly in cases of disputes. Burkina Faso has created a legal framework to regulate the procedures for registering and securing land, providing certificates of rural land ownership, rights of use, land charters, and local bodies to settle conflicts. This is essential considering the rising land demand resulting from population growth and the emergence of new players. The BTI 2022 Country Report for Burkina Faso maintains that although property rights and rules regarding the acquisition of property are adequately defined under law, weaknesses exist in the judicial system, which complicate or prevent their protection or implementation even though the state itself does not interfere with property rights. For example, suppose trust in the judicial system is contested; parties to a conflict cannot charge the legal system to adjudicate disputes predictably, encouraging extrajudicial vigilante measures (Eck, Citation2014).

Studies have found that properties inherited from one’s family are more secure than those acquired outside the family (Farmer, Citation2021; Kutsoati & Morck, Citation2014). This was consistent with the study findings, which showed that family inheritance was a significant factor in determining the perceived security of tenure and property rights protection. Household members who did not inherit property from their family lineage tended to have cumulatively lower perceived security of tenure and property rights protection (OR = 0.51, 95% CI: –1.314 to –0.013) compared to those who had inherited their property from their family lineage. In other words, household members who did not inherit property from their family had a 0.51 times lower perception of tenure security and property rights protection. Berry (Citation1997) finds that the position of individuals in families, communities, and society at large defines the security of rights. In 2009, the Government of Burkina Faso adopted the Rural Land Tenure Law, which legally recognises individual possession, collective land rights, and land transfers through inheritance (International Land and Forest Tenure Facility, 2022).

Customary laws and practices have long governed the rural land in Burkina Faso. Hence, the perceived security of tenure and property rights, to an extent, is determined by issues faced by local and customary authorities. The study found that household members who were not worried about losing their property rights due to issues with local and/or customary authorities had a higher perception of their security of tenure and property rights protection (OR = 3.56, 95% CI, 0.798–1.741) as compared to those who were worried about their security of tenure and property rights protection as a result of issues with local and/or customary authorities, holding other effects of other covariates constant. Although Burkina Faso’s laws allow for private property ownership, traditional systems and institutions are essential for distributing and securing land rights. Moreover, customary tenure systems primarily regulate agricultural lands. This could explain the respondents’ increased perceptions of their tenure security and property protection rights.

Nevertheless, despite these findings, land tenure insecurity remains challenging because of structural flaws in enforcing property rights, such as the wilful destruction of land titles. Additionally, the traditional land tenure system has disadvantages, such as women, migrants, and young people restricting their long-term access to land. For these groups, becoming self-sufficient and encouraging investment are frequently challenging because of situational uncertainty and the resulting lack of prospects (Sidibé-Reikat, Citation2021).

6. Multicollinearity test

The multicollinearity test results indicate that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in our Proportional Odds Model. All variables’ tolerance and VIF values, including gender, marital status, inheritance factors, issues with local authorities, conflict or terrorism, and institutional trust, are within acceptable ranges. This suggests that the statistically insignificant results for some variables are not likely due to multicollinearity but may be attributed to other factors, such as the nature of the data, the specific context of the study, or the inherent variability in the studied variables.

7. Conclusion and policy implications

This study’s exploration into the dynamics of perceived tenure security in Burkina Faso has provided critical insights into the interplay between legal, social, and individual determinants. By leveraging the analytical strength of Legal Institutionalism, the Social Tenure Domain Model, and the Credibility Thesis, we have identified how factors such as legal documentation, social legitimacy, gender, marital status, and trust in judiciary systems contribute to the sense of tenure security among the Burkinabé populace.

The empirical results suggest a clear need for policy interventions that not only streamline the process of obtaining formal legal documentation but also reinforce the social legitimacy of such documentation within local communities. Thus, a policy framework synergising statutory and customary tenure systems could enhance the overall sense of security. For example, incorporating community-based evidence as a complementary form of documentation in the formal land registration process could bridge the gap between statutory law and customary norms.

Gender-specific findings point towards the necessity of enacting and enforcing laws that specifically protect and promote women’s property rights. Such policies should ensure that women’s tenure security is not dependent on marital status and that they have equal standing in property rights irrespective of their marital circumstances.

The study also revealed that trust in judiciary systems is a cornerstone of tenure security. Therefore, policies aimed at bolstering the capacity, transparency, and accountability of legal institutions could significantly enhance the credibility of the judiciary system. This could involve establishing community courts with the power to adjudicate land disputes, which would be more accessible and potentially more trusted by local populations.

Despite the robust analysis, this research is not without limitations. While comprehensive, reliance on the Prindex data set may not capture the full complexity of local tenure systems and individual experiences. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to draw causal inferences.

Further research should focus on longitudinal studies to track changes in tenure security perceptions over time, especially in response to policy changes. Qualitative research could also provide deeper insights into how individuals navigate the intersection of statutory and customary land rights systems. Such future studies would offer a more dynamic and granular understanding of tenure security, ultimately contributing to more effective and responsive land governance policies.

Acknowledgement

The author sincerely thanks the editorial board and anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The online repository listed below provides access to the data for the analysis:

Prindex (https://www.prindex.net/data/): Prindex, short for Property Rights Index, is an initiative that focuses on people’s perceptions and experiences of property rights. Their website typically offers data and insights on land and property rights across various countries. This data is often used for research, policy-making, and understanding global trends in property rights.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ibrahim Musah

Ibrahim Musah, a Development Planner at Ghana’s National Development Planning Commission, holds a bachelor’s in Development Management and a master’s in Development Policy and Planning, focusing on Economic Development Policy. Currently a PhD candidate, he excels in social science and econometric research, data analytics, and policy analysis, with a keen interest in development economics.

Michael Ayerter Nanor

Michael Ayerter Nanor (PhD) is a lecturer at the Department of Planning at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He has a background in Economics, Mathematics and Development Studies. His research areas are data science, development economics, quality of life, urban and spatial economics, and machine learning in Social Sciences.

Kwasi Kwafo Adarkwa

Kwasi Kwafo Adarkwa (PhD) is an Emeritus Professor of Planning at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), where he served as Vice Chancellor from 2006 to 2010. He is a Fellow of the Ghana Institute of Planners (FGIP), the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences (FGA), and the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport. He is the editor of the Book “Future of the tree: Towards growth and development of Kumasi”.

Notes

1 1.4 by 2030, ensure that all men and women, particularly the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership, and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology, and financial services including microfinance.

Reference

- Adams, M., & Adams, M. (2001). Tenure security, livelihoods, and sustainable land use in Southern Africa. Sarpn.

- Adams, M., Kalabamu, F., & White, R. (2003). Land tenure policy and practice in Botswana- Governance lessons for southern Africa. Journal für Entwicklungspolitik, 19(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.20446/JEP-2414-3197-19-1-55

- AFRICA.COM. (2015). Burkina Faso: Land and property rights. February 15, 2021. Retrieved on April 12, 2023 from https://www.africa.com/burkina-faso-land-and-property-rights/#:∼:text=Most%20rural%20land%20is%20governed,to%20land%20through%20their%20husbands.

- Akaateba, M. A. (2019). The politics of customary land rights transformation in peri-urban Ghana: Powers of exclusion in the era of land commodification. Land Use Policy, 88, 104197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104197

- Alban, S. U., & Willem, E. M. (2020). Relations between land tenure security and agricultural productivity: Exploring the effect of land registration. Land, 9(5), 138.

- Allendorf, K. (2007). Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Development, 35(11), 1975–1988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.12.005

- Asaaga, F. A., & Hirons, M. A. (2019). Windows of opportunity or windows of exclusion? Changing dynamics of tenurial relations in rural Ghana. Land Use Policy, 87, 104042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104042

- Augustinus, C., & Tempra, O. (2021). Fit-for-purpose land administration in violent conflict settings. Land, 10(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020139

- Ayamga, M., Yeboah, R. W., & Dzanku, F. M. (2015). Determinants of farmland tenure security in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Science. Technology and Development, 2(1), 1–21.

- Babalola, K. H., & Hulla, S. A. (2022). Using a domain model of social Tenure to record land rights: A Case Study of Itaji-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. South African Journal of Geomatics, 8(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajg.v8i2.8

- Bambio, Y., & Agha, S. B. (2018). Land tenure security and investment: Does strength of land right really matter in rural Burkina Faso? World Development, 111, 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.026

- Barnes, G. (2009). The evolution and resilience of community-based land tenure in rural Mexico. Land Use Policy, 26(2), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.05.007

- Bartholomew, C. M., David, N., Moses, K. G., Godfrey, O. M., & Odongo, M. (2017). Development of an informal Cadastre using social tenure domain model (STDM): A case study in Kwarasi informal settlement scheme Mombasa. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 10(10), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP2017.0629

- Brasselle, A. S., Gaspart, F., & Platteau, J. P. (2002). Land tenure security and investment incentives: puzzling evidence from Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics, 67(2), 373–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00190-0

- Berry, S. (1997). Tomatoes, land, and hearsay: property and history in Asante in the time of structural adjustment. World Development, 25(8), 1225–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00039-9

- Chigbu, U. E., Paradza, G., & Dachaga, W. (2019). Differentiations in women’s land tenure experiences: Implications for women’s land access and tenure security in sub-Saharan Africa. Land, 8(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020022

- Chris, D. A., Martin, K. L., & Peter, C. B. (2011). What Is Tenure Security? Conceptual Implications for Empirical Analysis. Land Economics, 87(2), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.87.2.297

- Communication Initiative Network. (2015). Women and Land Rights in Burkina Faso. October 2, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2023 from https://www.comminit.com/la/content/women- and-land-rights-burkina-faso.

- Coulibaly, D. A. (2022). Analysis of the impact of land tenure security on agricultural productivity in Burkina Faso. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 18(4), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2022.128251

- Cox, P. N. (2003). An Interpretation and (Partial) Defense of Legal Formalism. Indiana Law Review, 36, 57.

- Dachaga, W., & de Vries, W. T. (2021). Land tenure security and health nexus: a conceptual framework for navigating the connections between land tenure security and health. Land, 10(3), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030257

- Deakin, S., Gindis, D., Hodgson, G. M., Huang, K., & Pistor, K. (2017). Legal Institutionalism: Capitalism and the constitutive role of law. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(1), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2016.04.005

- Deinlnger, K., & Binswanger, H. (1999). The evolution of the World Bank’s land policy: Principles, experience, and future challenges. The World Bank Research Observer, 14(2), 247–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/14.2.247

- Deininger, K., & Jin, S. (2006). Tenure security and land-related investment: Evidence from Ethiopia. European Economic Review, 50(5), 1245–1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2005.02.001

- De Zeeuw, F. (1997). Borrowing of land, security of Tenure and sustainable land use in Burkina Faso. Development and Change, 28(3), 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00055

- DFID. (2011). Inheritance in Ghana. UK Department for International Development. Retrieved on December 9, 2023 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08added915d622c000955/PN- Inheritance-Ghana.pdf.

- Dodman, D., Leck, H., Rusca, M., & Colenbrander, S. (2017). African urbanisation and urbanism: Implications for risk accumulation and reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.06.029

- Djurfeldt, A. A. (2020). Gendered land rights, legal reform and social norms in the context of land fragmentation-A review of the literature for Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Land Use Policy, 90(104305), 1–22.

- Doss, C., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2020). Land tenure security for women: A conceptual framework. Land Use Policy, 99, 105080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105080

- Durand-Lasserve, A. (2006). Informal settlements and the Millennium Development Goals: Global policy debates on property ownership and security of Tenure. Global Urban Development, 2(1), 1–15.

- Eck, K. (2014). The law of the land: Communal conflict and legal authority. Journal of Peace Research, 51(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314522257

- Emmaüs International. (2021). Putting A Stop To Gender Inequalities In Land Ownership In Burkina Faso. Retrieved on April 12, 2023 from https://www.ourvoicesmatter.international/en/alternative/putting-a-stop-to-gender-inequalities-in-land-ownership-in-burkina-faso/.

- Emmanuel, K. (2017). Land tenure and rights for improved land management and sustainable development. Land outlook working paper.

- Enemark, S. (2009). Land administration systems (pp. 10–13). Map World Forum, Hyderabad, India.

- Enemark, S., Bell, K. C., Lemmen, C., & McLaren, R. (2014). Fit-for-purpose land administration. International Federation of Surveyors.

- FAO. (2002a). Gender and access to land. ISBN 92-5-104847-9.

- FAO. (2002b). Land tenure and rural development. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations Land Tenure Studies 3. ISBN 92-5-104846-0

- Farmer, S. (2021). Knowledge of ‘heirs properties’ issues helps families keep and sustain land. Forest Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Southern Research Station.