Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to explore the social and cultural challenges and coping strategies of women experiencing infertility in Bichena Town, Ethiopia. This study followed a qualitative research approach and a descriptive phenomenological design. This study applied a purposive sampling technique and selected 30 samples. Through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and key informant interviews were used. Thematic analysis was employed for data analysis. The findings revealed that women experiencing infertility were challenged by social challenges; the major social components were isolation, stigma, family and social pressure, marital instability, and low social status. Women experiencing infertility were also challenged by cultural factors. Missing cultural rituals, trouble in asking newborn mothers, not considering full women or motherhood, and missing the value of children were the major cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility. Women experiencing infertility also used a variety of coping strategies, such as religious, traditional, medical, and informal fosterage. The study concluded that women experiencing infertility in the study area were challenged by social and cultural factors that made their lives bitter and used different coping strategies to manage their ongoing problems. This study has theoretical implications for current literature knowledge and practical implications.

Introduction

Having children is often considered part of the normal course of life (Halkola et al., Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2020; Vo et al., Citation2019). Infertility is defined as the inability to become pregnant or maintain a pregnancy despite having intercourse three to four times per week for at least a year, or the inability of a sexually active, non-contraceptive couple to achieve pregnancy in one year (Akalewold et al., Citation2022; Desalegn et al., Citation2020; Halkola et al., Citation2022; Karaca & Unsal, Citation2015; WHO, Citation2020). Demographically, infertility can be defined as an inability to become pregnant within five years of exposure based on a consistent union status, lack of contraceptive use, non-lactation, and maintaining a desire for a child (Akalewold et al., Citation2022; Lawali, Citation2015).

Infertility is a major clinical and social problem, affecting approximately one in every ten couples worldwide (Ergin et al., Citation2018). Infertility is normally identified at first as a physical problem and commonly linked with psychological, sociocultural distress (Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari et al., Citation2015). The terms ‘social challenges’ and ‘cultural challenge’ were often used interchangeably, but they have different meanings (Mangone, Citation2018). Social challenges refer to problems that arise from the interactions between individuals and society, while cultural challenges refer to problems that arise from differences in culture between individuals or groups. Operationally, in the present study, social challenges are factors leading to the experience of women experiencing inferetility in a certain social environment, such as ineffective social interaction, and social stigma, while cultural challenges are the factors of women experiencing infertility concerning the community’s traditional norms, values, and standards. Studies have indicated that even if women experiencing infertility in developed countries might not have social pressure as high as in traditional societies, in almost all societies, women experiencing infertility experience a certain level of stigmatisation depending on the varied social structures (Arjan et al., Citation2013; Öztürk et al., Citation2021). The cultural norms and ideals surrounding infertility are one reason why women experience infertility in developed nations may not face the same level of societal pressure as those in traditional communities. In some traditional societies, having children is seen as a social prestige, and couples are excessively pressured to get pregnant to maintain their family descent. Second, there are still differences in the availability of health care and infertility treatments between low- and high-income groups due to the high cost and restricted geographic reach of diagnostic services and assisted reproductive technologies, which creates huge gaps in certain traditional societies (Rouchou, Citation2013; Kuug et al., Citation2023). In Turkey, infertile individuals are inclined to hide their status of infertility from commity with the fear of social stigma. Higher rates of fear for social exclusion in women experiencing infertility are resulting from infertility (Ergin et al., Citation2018). In traditional collectivistic cultures across globe, women’s gender roles are defined in terms of marriage and motherhood. Therefore, when women are unable to meet the social and traditional expectations of being a mother, they are subjected to criticism, societal pressures, and stigmatization with the constant fear of getting a divorce or a threat of a second husband’s marriage (Saleem et al., Citation2021). In certain traditional Chinese and Indian cultures, women are only accepted as part of the family when they have children (Lawali, Citation2015).

A systematic review by Salie et al. (Citation2021) showed that infertility has impacts on marital and sexual relationships, quality of life and psychosocial well-being of couples, mental health and marital function among couples undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVR). For example, marriage without children is considered incomplete and insecure. Sexual problems in infertile people have been largely investigated (Santona et al., Citation2023). Couples describe infertility as the most difficult experience in their lives because infertility can affect marital relationships, family ties, sexuality, social and work life, family economics, future, friendships, and quality of life (Zeren et al., Citation2019). Women experiencing infertility use different coping strategies to solve their infertility problems. They apply religious coping strategies and gain faith-based strength to adapt to infertility. Women with infertility use a variety of strategies to cope with their infertility stressors, which in turn influence wellbeing (Lawali, Citation2015; Karaca & Unsal, Citation2015; Akalewold, Citation2017; Jemberu & Yemane, Citation2018; Jaradat & Zaid, Citation2019; Taebi et al., Citation2018). Women experiencing infertility have exercised traditional (cultural) treatment mechanisms, modern (medical) treatment mechanisms, or both, based on their preferences and exposures (Taebi et al., Citation2018). Women experiencing infertility also use herbal remedies to treat their infertility problems. For example, Jaradat and Zaid (Citation2019) indicated that Palestinian healers in the rural areas of the West Bank used different plants to treat women experiencing infertility and men.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical background of this study was framed on two main theories which could explore the sociocultural challenges of women experiencing infertility and their means of coping strategies. These theories are; theory of social stigma, and coping theory. Social stigma theory states that discrimination against an individual or group due to perceived characteristics that differentiate them from other members of a community is known as social stigma (Goffman, Citation1963). According to Assefa (Citation2011), stigma can be defined as a combination of elements, such as labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in different situations. There is a huge difference between individuals who are ‘fertile’ and those who are not when infertility is viewed through the lens of social stigma theory. According to Goffman’s theory of stigma, stigma can be divided into three categories: physical differences; perceived character deficiencies; and tribal stigma of race, nation, religion, or ideology (Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2020). First, physical difference or deformation stigma is an unfavorable opinion or attitude toward a characteristic of an individual or group of individuals connected to a perceived physical deficiency or infertility. It has to do with how a person or group is seen negatively by society because of a perceived physical trait or attribute. There might be detrimental consequences from this. Second, stigma due to perceived character deficiencies refers to unfavorable views or opinions about other people based on distinguishing factors like personality traits or actions that are seen to be undesirable. Stigma and the stigmatization process involve defining and labeling a ‘difference’, associating a labeled individual with negative characteristics, and dividing ‘them’ from ‘us’. As a result, the stigmatized group faces prejudice and a decline in status within the framework of social power. Negative outcomes like social isolation and discrimination can result from stigma. Third, the stigma associated with ideology is a negative attitude or idea about the features of a person or group of people. When society or the general public share negative ideas, thoughts or beliefs about women experiencing infertility, it affects stigmatized women negatively in terms of social and cultural aspects.

In relation to infertility, the victims belong to two categories; thus, they are physically different and have perceived character deficiencies because of the causes and meanings attributed to infertility by society. For instance, in most pronatalist societies, infertility is perceived to be the result of promiscuity and abortion; hence, characters of the victims are questionable. Furthermore, since some women experiencing infertility report irregular menstrual cycles, hormonal imbalance, unexplained causes, and problems in their womb, they are perceived as incomplete or deformed or perceived character deficiencies as per Goffman’s (Citation1963) theory of stigma. Although women may not necessarily be physically deformed, they are still considered deformed. This is because, with others, a complete woman should bear children (Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2020). Any deviations from these norms are frowned upon by members of that society. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, society expects girls of a certain age to marry and have children. Therefore, childlessness in marriage is a challenging situation associating women experiencing infertility as per social stigma theory (Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2020). Additionally, the theory helps to explore women experiencing infertility that deviate from the social expectation of parenthood in general and motherhood in particular. Therefore, the theory of social stigma is useful for understanding the challenges faced by women experiencing infertility living in fertile communities.

In addition, this study was supported by coping theory. The theory was mainly used to examine the distress level of people who experienced different social and health problems or those who faced stressful encounters, such as mental health problems, breast cancer, infertility, and divorce. As Lazarus (Citation1981) defined an imbalance between demands and resources is known as stress. Continual behavioral and cognitive attempts to handle certain external and/or internal pressures that are judged to be greater than the person’s resources are referred to as coping. People use their coping mechanisms as a resource to deal with life’s responsibilities. All of life’s demands are what lead to stress. The coping focuses on how our abilities interact with the challenges we encounter, from grieving the loss of a loved one to managing infertility. Coping mechanisms are developed by people in both their early and adult lives. According to Folkman et al. (Citation1986), coping serves two main purposes: first, it regulates unpleasant feelings (emotion-focused coping) and second, it modifies the problematic person-environment connection that is causing discomfort (problem-focused coping) (Folkman et al., Citation1986). According to Lazarus (Citation1981), the process of coping is a gradual one, therefore a person may choose a certain coping strategy—such as medical—in some situations and an other one—such as religious or traditional coping strategies—in other situations. Such a strategy decision occurs as circumstances change. The study has used coping theory to recognize and distinguish the coping strategies used by informants to solve external problems of stigma and discrimination and internal emotional problems of their infertile women.

To sum up, social stigma and coping theories are used to describe the social and cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility as those who are stereotyped often start to act in the ways that their stigmatizers expect of them. Moreover, these theories are also helpful for analyzing the cultural elements or practices of being infertile, how the cultural and social practices of the community look like to perceive and treat or support women experiencing infertility (Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2020).

Infertility in African and the Ethiopian context

African women experience social stigma as a result of infertility. For example, in Ghana, women are reported to have social stigma, marital strain, instability, and social isolation (Lawali, Citation2015); in Zambia by Howe et al. (Citation2020), women experiencing infertility are more socially neglected and prevented from activities that need social involvement than men. When people face the problem of infertility in most parts of Africa, they try traditional spiritual practices rather than medical treatment. For instance, in Nigeria, Yoruba showed that many infertile couples use a variety of traditional and religious treatments, whereas medical treatments are less often used (Lawali, Citation2015). A qualitative study conducted in Ghana by Lawali and Abbas (Citation2019) clearly stated that women with infertility problems in Zamfara used coping strategies related to religion, social support, child adoption, and distraction activities.

In Ethiopia, it is challenging to obtain well-documented data and recent studies on the social and cultural challenges faced by women experiencing infertility since there are scarity of researches about socio-cultural challenges of women experiencing inferity as most previous scholars examine the magnitude, prevalence of infertility, and determinants of infertility (Akalewold, Citation2017; Jemberu & Yemane, Citation2018; Desalegn et al., Citation2020). According to Akalewold et al. (Citation2022) in Ethiopia, due to lifestyle changes and the presence of various environmental pressures, the prevalence of infertility has increased significantly and has become the third most serious disease after cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Women experienced infertility in Ethiopia are also faced various challenges. For instance, a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia by Akalewold (Citation2017) confirmed that women experienced inferility are exposed for different psychosocial problems such as stigmatized and avoided from social occasions. Other study in Ethiopia by Assefa (Citation2011) also confirmed that childlessness totally unacceptable and thus women experiencing infertility were not considered as women at all. Desalegn et al. (Citation2020) in Ethiopia have found age at the first pregnancy, age at menarche, multiple sexual partners, and number of days of menstruation flow were determinants of women’s infertility. A study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, by Akalewold (Citation2017) confirmed that women experiencing infertility are exposed to different social problems. Infertile females are stigmatized and avoided on social occasions. Societal awareness and culture put great pressure on women. A study conducted in Ethiopia by Jemberu and Yemane (Citation2018) revealed that women experiencing infertility have used religious strategies to manage their infertility problems. In Ethiopia, social support is an effective strategy in the stress management process in which an individual accepts help from others (Taebi et al., Citation2018).

Thus, the first gap identified in these studies is the content scope, which means that the issue of the problem intended to be studied. The above studies have paid little attention to the social and cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility in Ethiopia, and they have failed to explore the social and cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility as separate and cross-cutting issues. Second, in terms of its significance, this study would intend to explore the social and cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility and forward possible recommendations that help those women experiencing infertility to manage their challenges. It also helps those people nearest to women experiencing infertility including their families and relatives, to have a better understanding about infertility and its challenges. Then, they can adjust themselves to support women experiencing infertility in maintaining their good social status, and help to avoid harmful coping strategies. Empirically, findings of the study were hoped to fill the gap addressing the social and cultural challenges of infertility among women and thereby add value to current knowledge and experience. The study also would help anyone who intends to take part in awareness creation and related developmental psychology areas; to understand how the problem of childlessness is deep rooted in the community and the roles of the different groups in the community (childless individuals, religious leaders, community members, and health workers) in the prevention problem. The third gap identified in the above-mentioned studies is the geographic scope, which means that almost all studies are limited to the study areas. Although numerous studies about infertility have been carried out in Addis Abba city administration of Ethiopia, it is crucial to note that every region or district has subcultures, which makes the experiences of infertility differ significantly in different communities and settings (Kuug et al., Citation2023; Osei, Citation2014). However, our study bases the participants on those who dwell in the Bichena town and may practice different treatment or coping strategies, which means that they are not institutionalized. Therefore, to fill the gaps identified above and address the challenges mentioned above, the following research questions were raised:

What are the social challenges of women experiencing infertility in Bichena town?

What are the cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility in Bichena town?

How do women with infertility use and adopt coping strategies to manage their infertility challenges?

Materials and method

Research design

The research used a descriptive phenomenology research design based on the purpose of the study. This is because, according to Mayoh and Onwuegbuzie, (Citation2015), descriptive phenomenology describes the common themes that experience the identity of the phenomenon and transcends the experience of different individuals. The researchers chose a descriptive phenomenology because the study focused on descriptions of participants’ individual experiences. Qualitative research designs like descriptive phenomenology can assist researchers to better understand the cultural nuances and the subjective impact of stigmatization (Arjan et al., Citation2013).

Participants and sampling methods

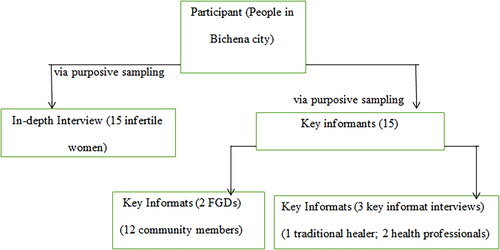

All women experiencing infertility who dwell in the Bichena city administration, Ethiopia, were included in the study. The Bichena city administration has five kebeles (01-05). Kebele is a local administrative entity within district. It has some similarity to a village, which is often made up of many neighborhoods.From these kebeles, researchers selected kebeles 02 and 04 by employing a purposive sampling technique. The rationale behind selecting these two kebeles is that they are densely populated in terms of people who have marital status when compared to the other three kebeles (01, 03, and 05 kebeles). By employing a purposive technique, about 15 women experiencing infertility and 15 key informants, a total of 30 samples were collected as presented in .

The Participants (selected discusscants from different parts of the community, and key informants from traditional healers and health professionals) were familiar with the surrounding people, culture, norms and attitudes. The goal of qualitative research is to examine the richness and diversity of human experiences in particular circumstances rather than to provide conclusions that can be generalized to broader population. Therefore, participants have various characteristics that can be help to get rich information, but not to generalize to the broader population. The inclusion criteria to choose 15 women experiencing infertility were: age: the age of women experiencing infertility ranges from 18-49; who married for at least the past 12 months; who did not use contraceptives in the time one year before the date of the interview; Who had not conceived in the past up to the date of our interview; and live in Bichena city administration. Of the 15 women experiencing infertility .Most of them were literate (two of them were degrees, five were diplomas, six were under grade eight, and two were illiterate). Except for two women, all were married. All had siblings, and their siblings were born to at least one child. Regarding occupational status, eight were civil servants, four women experiencing infertility were merchnats and three were housewives. Nine of the women experiencing infertility’s husbands had children from either a previous wife or a hidden woman. Fifteen key informants were selected from different departments based on their professional or job status. The general criteria were as follows: living in the town, working for three years or more in their assigned position, expected to have better information about infertility, and voluntary participation in the study. It was essential for the study to include women experincng inferility as well as important community informants, healthcare professionals, and traditional healers to obtain different and relatively comparable perspectives from each group. According to Staley et al. (Citation2021), research that involves a variety of groups is valuable because it can increase the research’s applicability and relevance for end users and expand the range of viewpoints and areas of knowledge that may be applied to the research question. Therefore, gathering data from different range of the participants depending on the role they play in their community could offer a relatively balanced set of viewpoints and a variety of perceptions to analyses about sociocultural challenges and coping strategies of women experiencing infertility

Data collection

In-depth interview

In-depth interviews were used for data gathering for qualitative studies because they enable researchers to obtain in-depth information about the experience of the participants. Questions were prepared from the literature reviews in line with the objectives and basic questions of the study. For this purpose, major leading questions were prepared and given to women experiencing infertility. Semi-structured interview questions allowed participants to discuss their views, experiences, and challenges in a detailed manner. It also helps researchers probe more about the issue under study. The questions were validated based on the comments of subject matter experts. In addition, the interviews were tape-recorded with the consent of the participants. However, the participants could stop the interview at any time they wanted to stop and continue whenever they could.

Focus group discussion

In this study, the incorporation of a focus group was used as an intervention to explore social and cultural challenges and coping mechanisms among women experiencing infertility in Bichena town by selecting usually 6-12 participants purposively from the target population, gaining unique insight into existing values, beliefs, behaviors, attitudes, and generation of a group interaction data, as well as using the group as a unit of analysis (Tesfaye, Citation2019). Two focus group discussions (six members in each group) were held among 12 key informants from different parts of the community. They were asked to explore in detail the social and cultural challenges faced by women experiencing infertility when they lived together. They were also asked to explore the coping strategies that women experiencing infertility around them have used and what they recommend. Therefore, three major questions (social challenges, cultural challenges, and coping strategies) are presented. During the FGD session, a tape recorder was used, and the researchers played a moderating role to facilitate the discussion. As a moderator, the researcher tried to involve all participants in the discussion and to keep the discussion point on track. As a result, FGD would enrich the data collection, in order to triangulate the data acquired from key informant interviews and in-depth interviews.

Key informants’ interviews

The researchers interviewed three key informants regarding the social and cultural challenges and coping strategies of women experiencing infertility. As the researchers have made informal discussions with both infertile and fertile women in the town, people who are not few in number are going to traditional healers to alleviate the different problems that they encounter. Therefore, this study selected one well-known traditional herbal healer who dwells in the town as a sample. The major focus of this interview was on traditional coping strategies and their effect on women’s infertility. In the Bichena city administration, there is one first-level hospital to which women go to check their infertility-related issues. The study selected two samples from this hospital with a better experience and understanding of infertility. Three leading questions (medical causes, challenges, and medical treatment as coping strategies) were presented. In addition, the interviews were tape-recorded with the consent of the participants. The purpose of choosing key informants’ interviews is to collect information from professionals; this particular knowledge and understanding helps the researchers provide insight on the nature of the problem and provide recommendations.

Data collection procedures

After obtaining ethical approval, the researchers used semistructured data collection guidelines; the researchers visited the village of each infertile woman and key informants who participated in the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations Debre Markos University. Participants were informed that their names and institution names would be kept confidential and their privacy rights were protected. Participants were included in the process on a voluntary basis and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Data were gathered through in-depth interviews with women experiencing infertility assigned for this study. Next, data were gathered using focus group discussions with community members with different statuses. Twelve members of the FGD participants were assigned to the discussion, and two FGD discussions were held in each group with six members. Subsequently, interviews were conducted with three key informants, one traditional healer, and two health practitioners. Raw data were then collected through analysis.

Data analysis

The data collected through the three instruments (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews) were coded or broken down into manageable words, and texts pertaining to the codes were translated into English. As a result, preliminary codes followed by final codes were developed. To conduct thematic analysis, the coded data were examined using thematic coding (Creswell, Citation2007). Interviews were held in Amharic language and then the data were translated and transcribed by the researcher and the researcher’s assistant, since the researcher also understands Amharic, the researcher checked those audio records again to ensure the correctness of translation and transcription. Cohen et al. (Citation2007) procedures of analysis qualtitive data with the help of the software of NVIVO version 12 were used. The procedures are; first, the researchers conducted the data cleaning by using paragraph style. This was used for grouping data according to the research questions. Second, the researchers uploaded the data into NVivo. Third, the researchers reorganized the data by grouping data based on the research questions. Fourth, the researchers conducted data exploration (using ‘Query command’) to find the words or phrases that respond to the research questions. Then, the researchers began coding relevant information. Fifth, the researchers generated themes. Finally, the researchers have made an export of the nodes and computed the frequency using excel. Lastly, the researchers explained themes based on their frequency by adding direct quotes from the participants.

Trustworthiness

To ensure trustworthiness of the study, first, the selection of participants was not comprehensive, but was conducted by setting inclusion and exclusion criteria before data were collected to avoid bias and subjectivity. Second, audio recordings from participants were performed based on their full volunteerism, and after full agreements were obtained. Third, for the clarity of the language used for the data collection instruments, the English version of the translation was repeatedly checked by experts in the subject area and the English department who worked at higher learning institutions. Obtaining feedback from peer review is another procedure employed to enhance the credibility of the study. Fourth, the researchers cross-checked the data offered from different methods of data collection tools and the time of the data collection session; the researchers never misled the participants by any means or gave wrong personal impressions regarding the issue. Moreover, as ethical considerations, after obtaining approval, personal identifying information on participants, such as names, addresses, date of birth, and other personal critical or privacy issues, are not reported and revealed in all articles stated in the study to protect their privacy.

Findings

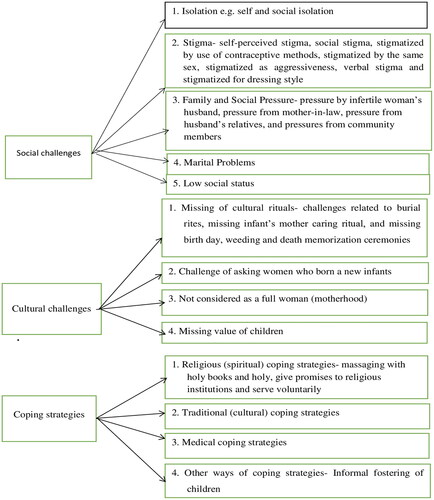

According to the results of the thematic analysis, three categories were determined in line with the three research questions. In , the details of the themes were given.

In , five subthemes were determined related to the ‘social challenges of women experiencing infertility’ theme. In the second main theme, four subthemes were emerged related to the cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility. Finally, in the last main theme called coping strategies; four subthemes such as religious, traditional, medical, and other coping mechanisms were presented. The details of main themes and subthemes were presented as follows:

Social challenges of women experiencing infertility

The women were exposed to different social challenges. Based on the data collected from the respondents, the common social challenges experienced were self-and social isolation, social stigma, social pressure, marital problems, and lack of social support.

Isolation

According to the respondents, women experiencing infertility in the study area were challenged by two forms of isolation. They are isolated consciously or forced from society by society. Therefore, women experiencing infertility described isolation as self-isolation and social isolation.

Self-Isolation- Social isolation is a way of separating or distancing oneself from other people for various reasons. Women experiencing infertility purposely distance themselves from gathering other people. In particular, in different societal activities, women experiencing infertility control themselves through involvement and are kept in their homes. IDP 2 isolated herself from her colleagues in the school due to the fear of sharing negative words about her infertility problem.

In the school, during our free time, both men and women have spent their time in the school’s cafe. They talk everything which creates fun and enjoy that. Most of the time I separate myself from that café and stay in my department room. This is because I fear that they may talk about my infertility and may send negative words to me. That may hurt me psychologically. So, to avoid such things, being alone is better for me. (IDP2).

Another infertile woman isolates herself to get enough time and enable her to think about her current situation (her infertility).

Social isolation- Women experiencing infertility experience social isolation as a result of society isolating them from different forms of social activities, interactions, and decision-making processes. According to the respondents, women experiencing infertility need to be involved in social interactions and activities. However, they perceived that community members isolated them for different reasons. Respondents confirmed that this social isolation came from the husband’s family members, their own family members, neighbors, colleagues in the workplace, and other community members.

According to IDP6, people have isolated her when discussing children in whatever issues.

Another infertile woman also said that her mother-in-law had isolated her during discussions about the birth-day celebration of other daughter-in-law’s children. She reported to the researcher that her mother-in-law, daughter-in-law, husband, and other family members who have children were called to home and discussed the birth-day celebration. They planned activities to be conducted before and during the celebration.

Another infertile woman described that she was challenged by social isolation when trying to correct and manage her younger sister’s children. She said to the researchers that her sister’s children have certain misbehaviors, like not respecting parents and refuse to go to school. At that time, she wanted to advise, correct, and manage the children. However, she said that her sister opposed and reacted negatively to her. She shared her feelings below:

My sister is nine years behind me. Before she became a mother, she respected me. I have married before her but she may bear children before me. This is my fortune. Even if I have enough experience in caring for children, my sister didn’t allow me to do so. She reacted to me as ‘don’t touch my children. Get off your hand from my children. You don’t have the right to control them’. She also added a negative saying ‘Born and punish’. So, even my sister told to me that I have not the knowledge to care, correct, advice or manage children and isolate me. (IDP14)

Stigma

According to the respondents, women experiencing infertility in the study area are highly challenged by stigma, which leads them to experience unacceptable phenomena. Based on the data collected from women experiencing infertility and key informants through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, women experiencing infertility experience stigma in various forms:

Self-perceived stigma- Some women experiencing infertility in the study area internalize what other people around them are talking, doing, and behaving in their minds. They feel that all people they see may say something about their problems and personalities. On every occasion, women experiencing infertility say that when people talk, for instance, about children, marriage, and treatment, they assume that the issue is directly about them (women experiencing infertility), even if their guess is quite wrong. The following respondents shared their perceived stigma:

I have sometimes heard some discussions of my husband with his parents in my home that were not related to me, I will feel as if they were really talking about me and stop to work and send my ear towards them to identify clearly. Although sometime I used to realize that they were not referring to me, in most cases I feel as if they were referring to me (IDP15)

Social stigma- It is the community’s perception of wrong and prejudiced attitudes towards women experiencing infertility. Community members stigmatized women experiencing infertility in different ways. The following findings indicated different ways of stigmatizing women experiencing infertility in Bichena town according to the respondents’ responses.

Stigmatized by the use of contraceptive methods- Some women experiencing infertility are stigmatized by community members because they have used different family planning methods for a longer time to avoid pregnancy. The women experiencing infertility described their stories below.

My neighbors were telling me to stop using of contraceptive methods to become pregnant. Although I tried to tell the fact, they didn’t believe me and said ‘we advise you to benefit you. It is you to accept our advice’. (IDP6)

Stigmatized by the same sex - Most participants complained about being labeled by other fertile women. Women experiencing infertility believe that other fertile women should understand their problems better than men and are expected to provide support. However, some fertile women failed to do so, and sarcasm, humiliation, and throw very negative and harsh words and phrases at them. For instance, the following infertile woman validated the idea of same-sex stigma.

When my mother-in-low introduces me to others (when we are going to somewhere or if other people are coming to home), she says; ‘she is my daughter-in-low, she is in our family for more than ten years but still has no children. Please pray for her. She was not blessed and thrown way by God. At the moment, I and my son have carried her on our back without any benefit. Especially, my son is very patient who still lives with her. May be one day I do not know what will happen’. You know, the mother-in-law tried to simulate she worried about my case (her infertility) and found out solutions for other people. But, I know the truth, she wants to hurt me. She wants to say that the entire problem is from my side. (IDP2)

Supporting the above infertile woman’s view, another infertile woman also confirmed that when she analyzed and compared both men and women in the family member, men were somehow better at stigmatizing her than women. She said that the women were cruelers.

Stigmatized as aggressiveness- Some women experiencing infertility have described how people are stigmatized because of their changes in behavior. They said that others frequently commented on their aggressiveness on every occasion. They also reported that their neighbors were getting in trouble communicating with them easily due to their aggressive behavior after the problem of infertility (IDP9). Related to the change in behavior of women experiencing infertility, the researchers asked focus group discussion participants and replied that women experiencing infertility lack tolerance, have no good mood, tend to behave aggressively, and are nearer to conflict (FGDP12, 3, 8).

Verbal stigma- Most women experiencing infertility have described how the people around them are stigmatized through different negative words that create stigma. According to the respondents, physical harm was better than verbal harm. This is because, as they stated, negative words could not easily forget, you could not avoid from your mind that is painful. In what state they stigmatize us; it damages our personalities, hurts our lives, and disrupts social interaction. The following respondents confirmed the exposure of women experiencing infertility to verbal stigma:

When one woman could not bear children, the societies call her ‘Mule’. The name is obvious. This is because the ‘Mule’ cannot bear until death even if she has mated. That is naturally given by God. So, when a woman cannot bear, we give the character of that animal (mule) for that woman.(FGDP5)

Two other women experiencing infertility also described their mother-in-law and husband stigmatized verbally. She responded that she was the third wife. Her current husband married two wives before her, and both of his former wives had born children. After she married the current husband, she could not give children to her husband. She also said that one of his (her husband’s) daughters was exposed to chronic disease. Consequently, her husband and family members were verbally stigmatized.

Stigmatized for dressing style - Some women experiencing infertility in the study area have clearly stated that people around them are given bad names after looking at their dressing style. According to the respondents, people have two contradictory views on the dressing style of women experiencing infertility. One thing that can surprise women experiencing infertility is the bad comment about dressing, which is highly given to women experiencing infertility than others. The following respondents reflected on their views:

Some people, especially women, said to me that ‘instead of dressing different fashioned clothes everyday, worry for your problems and give children to your husband. Changing different new clothes don’t become a child and could not enable a full woman’. So, they stigmatized me when I wear new clothes and I am worried for that. (IDP5)

On the contrary, some women experiencing infertility reply that when they wear old clothes and cannot change it because they become hopeless and careless and worry much about their problems, people are not stopping giving bad comments and stigmatizing them (IDP4).

Family and social pressure

According to respondents, the pressure of being infertile started at the family level and spread to neighbor and community levels. Respondents also added that when your family understood your problems and stood with you, the pressure from the outside community did not match the challenge. However, society also pressured women experiencing infertility’s families. In our culture, having children is highly valued as a source of respect and pride for the family. Therefore, the family needs to have children from their daughters-in-law. This condition creates pressure from family and society. The collected data indicated that common pressure has increased from women experiencing infertility’s husbands, mothers-in-law, husbands’ relatives, and society. The following analysis indicates this issue in detail:

Pressure by infertile woman’s husband- Some women experiencing infertility have described that they experience different forms of pressure from their husbands in everyday activities. The following infertile woman experiences pressure because her husband gives two undesirable alternatives to continue with her as a wife. She stated her views as follows:

My husband sometimes threatens me by presenting two alternatives which are undesirable. He said that ‘I don’t continue without having children. So, I have two options for you; one, can I bring a child from the other fertile single women to this house and could you care? Two can I divorce you and marry another fertile and beautiful woman? Which one is comfortable with you? Please think and prefer’. Both options are not preferable. I have preferred to stay in my marriage and believe God’s surprise. However, my husband asks my answer which pressured me a lot (IDP15)

Another infertile woman said that she was pressured by her husband because she usually thinks about marrying another wife.

Pressure from mother-in-law- According to respondents, the mother-in-law’s pressure is mostly higher than that of the father-n-law. Sometimes, fathers-in-law also pressure women experiencing infertility. Mother-in-law pressured her son’s infertile wife by stigmatizing her, pushing her son to divorce, isolating her (daughter-in-law), and threatening. An infertile woman said that her mother-in-law had forced her son to divorce. She also added that her mother-in-law was going to be older, and she needed to see her son’s children.

After my husband and his mother have discussed about having children, he (her husband) came to me and said that ‘my mother wants to see my son and to become grandmother. So, what shall do better? I didn’t come up to my mother’s pressure’. So, my husband starts to think about divorce because of his mother pressure and one day he may divorced me. Such conditions create higher pressure on me (IDP15)

Pressure from husband’s relatives- Women experiencing infertility in the study area are not only pressured by their husbands and mothers-in-law. They described that their husbands’ relatives also exerted high pressure on them because of their infertility problems. Five of the women experiencing infertility shared their stories regarding committing pressure from their husbands’ relatives. IDP 8 disclosed that her mother-in-law’s sister provoked her husband to change his behavior and abused her. Another infertile woman said that her husband’s relatives were talking and deciding about her future life without consulting her, and in every meeting, they discussed her divorce.

Pressures from community members- According to respondents, community members have pressured women experiencing infertility who live with their husbands and who are divorced.

……. Oh! It is very hard for women experiencing infertility. The people put a high amount of pressure on them. For instance, if women cannot become pregnant and bear children, they are not considered as full women. The family and the community members could not give proper attention. Those women experiencing infertility also become under the mockery of the people. (FGDP7)

When their husbands have abused them physically, no one has said something to mediate them when the cause is infertility and people also think that the reason will be that. When the issue of divorce is also raised, the society doesn’t stop it, rather facilitate and support it. This is because children have great value in marriage and life of people. So, such issues pressure women experiencing infertility. (FGDP9)

Marital problems

According to the collected data, marital problems are another social challenge for women experiencing infertility because of their infertility. Three major aspects were identified as common marital problems among the women experiencing infertility in the study area. They are the conflict, divorce, and marriage of another wife. Women experiencing infertility described marital problems as experiencing conflict with their husbands.

Because of my infertility, my husband insults me and I become aggressive and replied to him angrily. So, sometimes we have experience conflict in home during night time. Sometimes, our neighbors come to us and mediate us (IDP3).

The FGD participant mentioned that it is difficult to marry women who are known to be infertile unless the man does not need to have children. They mentioned their ideas with an example that they knew practically.

You know ‘ato Sileshi’ (the older man saw other participants of the study and continued his explanation). His current wife is infertile. He married her purposely not to have born children because he has, I think……eight children from his former wife who was died. He loves money a lot and when he has born other children, he thinks that they share his property. So, he decided to marry an women experiencing infertility. Otherwise, women experiencing infertility have very low chances of remarry. (FGDP6)

Low social status

According to the respondents, many women experiencing infertility have a low social status in the community. Respondents said that there are different criteria by which the community provides high value and status for people. The most important thing that the community takes into account when giving high social status is having an active marital status with many children. Respondents also said that, even if people have divorced, they get respect from society when they have many children. Family members also respect and give better attention to women who have children than to childless women. The infertile woman described that she experienced a low social status as she lacked respect from other people.

…Even my younger siblings do have children so they are being much more respected than I am. Sometimes, when there is a conference for women in the kebele, my neighbors don’t call me. Instead, they said that the call ‘Abushaw’s mother’ and when I say wait me; they replied that ‘It’s a meeting for parents. You are not a parent, so you are not eligible to be in that meeting’. So, they give low status for me. (IDP8)

Generally, women experiencing infertility in this study experienced various social challenges or social stigma through mocking. This study also revealed that women experiencing infertility in Bichena town are isloated, stigmatized by husband’s relatives, community members in the form of dressing style, verbally change in behavior, use of contraceptive methods, and by the same sex.

Cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility

Missing of cultural rituals

Cultural challenges related to cultural rituals include the following.

Challenges related to burial rites - According to the respondents, the status of burial rites is an indicator of a very respected and successful person. The number of people who participated in the burial time and at the place of tombs has given great value to society. They said that our culture emphasized this phenomenon. Families that lost one of their members have become satisfied and proud when accompanied by an infinite number of burial participants. On the contrary, if a small numbers of people are involved in burial rites and have few relatives or children, the pavilion that is prepared for grief becomes empty. This situation creates feelings of inferiority in the family, who have lost their members in death. Societies also give them a lower social status.

The FGD participants described that having many children is important in the case of burial rites for different reasons. On the one hand, parents have built relationships through marriage with different people and have created a big family dynasty. The parent becomes a grandparent and considerable grandparent. On the other hand, all children of the parent will have their own different groups, which can minimize and share the grief of the losing parent. Thus, in sum, having children makes the burial rite hugely bright.

If you don’t have children, a very small number people may be participating in funereal and the pavilion becomes vacuum. That is painful. That is, the second death for the passed away person. (FGDP4)

Missing Infant’s mother caring ritual - According to respondents, in the culture of the community, when women are born, they go to their mother (first time of birth) or stay in their own home (starting from the second birth) and sleep in the prepared bed for about 40 and 80 days. Currently, family members are given high levels of care and affection. Women experiencing infertility have stated that they cannot create children and experience such rituals. Instead, women experiencing infertility are expected to care for their sisters, brothers’ wives, mothers-in-law, or other fertile women when they are born.

When a woman becomes pregnant, she begins to prepare porridge powder from different crops. Such factors also create mental satisfaction in pregnant women. Women experiencing infertility did not obtain such satisfaction. However, they participated in preparing the porridge powder, and they thought and prayed to God when their turn could reach. The following respondent stated her views:.

I have prepared porridge powder several times for my siblings and relatives. I have also cared of siblings who have born children. People around me said that ‘when do you prepare for yourself? Why God do not count your pray and fatigue and give children to share such ritual?’ One of my younger sisters has very good looking to me and support what she can. She said to me that ‘you cared me a lot when I had born those three children. I have your favor. When do I return it back?’ I give up at the moment that I never prepare it and I feel that I missed the porridge ritual (IDP10).

Missing Birth day, weeding and death memorization ceremonies - According to the respondents, weeding, birth day, and yearly death memorization have great cultural value. Society has judged and admitted those people who have large gatherings and active engagement or blame and mock for those who do not below the society’s standards. One of the women experiencing infertility said that when she attended birthday ceremonies, she experienced mixed emotions. She was challenged by two opposing feelings.

My staff members and neighbors have invited me to their children’s birth day at different times. I have experienced mixed emotions. For one thing, those children are also my children and their happiness is also to me. When they have played and call their mother in their birth day time, when my friend’s children come to share their birth day, I become happy. On the other side, I feel jealousy and disappointed. I ask my lord that why he disallowed to me to have children and celebrate my child’s birth day and sometimes I want to stop going anywhere to celebrate such things but I cannot. (IDP3)

Some women experiencing infertility worried about their death and cultural practices. Whatever they have helped other people and participated in other people’s happiness and sorrow events, when they die; all of their efforts have no value or place. They also added that when they have many children, they do not die in spirit, although they do die physically. They described that their names were above the ground, and their children remembered them.

Challenge of asking women who born a new infants

According to respondents in the study area, when women have born, asking them to grasp something that can be food or drink is culturally expected. The people who go to ask may see the new infant and kiss their hand. However, it is not easy to do so for some women experiencing infertility. Some women experiencing infertility have said that society and the mother who has born did not allow them to ask for cultural reasons.

When I go to ask women who have born, they cover their infants and sometimes themselves. This is because they see me as a unique and unfortunate woman. They and other people think that a bad spirits may enter with me to their house. So, their new infant and the mother may be hurt. Consequently, I am not allowed to enter in the house and back door. (IDP7)

Additionally, one infertile woman pointed out that one of the challenges in asking a newborn infant’s mother is the emotional disturbance and insult of you by other people (IDP9). Supporting this infertile woman’s view, one FGD participant added her feeling: ‘In our culture, when childless women have cried in a new infant’s home, bad things may occur. So, if we identify someone’s behavior, we put outside the infant’s home’. (FGDP5)

Not considered as a full woman (motherhood)

According to the respondents, in the study area, when a woman marries, what society expects is the rearing of children. Therefore, one and the prior cultural criteria to become a full woman and considered as a mother is bearing children. One FGD participant discussed the following: ‘…there is no best criterion to check a woman as a full woman except the bearing of children. All women are not equally considered as full women and all women cannot become mothers unless they bear children’. (FGDP8). One infertile woman also believed that without children, she cannot see herself as a mother or full woman. This is because she believes that she has lost a major issue (bearing children). She remembered her past story when health extension workers registered the number of mothers and fathers in each home (FGDP1 and 2).

Missing value of of children

According to the respondents, and as clearly stated in a review of related literature, in Ethiopia, society has given higher value to children. The children are all with their parents. Children can positively change the lives of couples and make their parents happy. Respondents saw children as the main source of income. People in the study area perceive that children will bring something special and good to their parents. They also added that initially parents are playing with them and finally parents get a guarantee on their last edge of life. Most of the women experiencing infertility responded that they love their children, and when they have seen them react in warm and different emotional states. One of the participants validated her feeling of love for children when she saw the following:

I have no words to express my state of loving children, I like them very much and I feel happier when the children of my neighbors come and play in my house. Sometimes, I call to my home when I have seen near my home’s fence. I usually give them whatever I have in my home. I have also played with them and given playing material for them. I need them to make dirty of my house. (IDP6)

In short, women experiencing infertility were also challenged by cultural factors. Missing cultural rituals, trouble in asking newborn mothers, not considering full women or motherhood, and missing the value of children were the major cultural challenges of women experiencing infertility. This finding also revealed that women experiencing infertility feared that they missed mother-care rituals and values of having children. The newborn mother has had plenty of cultural caring rituals. Newborn mothers eat hot porridge and other types of food that can repair their damaged and fatigued bodies. The relatives of newborn mothers cared for them. Women experiencing infertility have thought that they have missed such rituals.Therefore; infertility needs to be seen as a public health and sociocultural issue rather than a pure medical condition.

Coping strategies of women experiencing infertility

Women experiencing infertility in the study area have attempted different coping strategies to address their infertility challenges. They used religious (spiritual) coping strategies, traditional (cultural) coping strategies, marital separation, acceptance, and medical coping strategies. The most widely used coping strategies are religious and traditional. Some women experiencing infertility have tried to use medical coping strategies, but they have again gone to religious and traditional ways.

Religious (spiritual) coping strategies

According to the respondents, a religious coping strategy is preferable to solve infertility challenges. This is because all options, including medical treatment, can become effective when God is allowed to happen. Therefore, they prioritized this strategy.

Massaging with holy books and Holy cross- Some women experiencing infertility also tried to solve their infertility problem by massaging their bodies with holy books and crosses. According to their responses, they had a certain mental rest from their infertility-related stress. They said that on every Sunday and on a saint’s day, they are going to the nearby church and massaging their bodies with different holy books and crosses after the process of the Mass system. Some women experiencing infertility visit other historical and blessed churches for similar purposes. The following women experiencing infertility share their stories:

I went to ‘Gishen Mariam’ in every year for a longer time and I have massaged my stomach with ‘the miracle of Saint Mary’s book’ and smear ‘the Mary’s creed’. Still, I have no change in my life but one day Virgin Saint Mary will give a child to me. (IDP6)

Give promises to religious institutions and serve voluntarily-Some women experiencing infertility have described that she promises to God in the name of Saint Angel, Saint Martyr. They also stated that they entered into different promises to obtain children. They also voluntarily participate in different church activities when work is needed. For example, they fetched water and carried stones or cement when the churches were rebuilt.

I have promised golden umbrella cloth for priests, money, and other things in different years for different churches. However, I have not received children. (IDP1)

I have promised to God that if I get children, I will give to God to serve him by learning religious education (IDP2).

Traditional (cultural) coping strategies

Women experiencing infertility also reported that they used different traditional or cultural strategies to alleviate their infertility problems. Commonly tested traditional methods are visiting traditional doctors (herbal healers) and going to wizards. One infertile woman went to a wizard found in south Wollo, Dessie town, and stayed with him for three months until her problem was cured. She described that after two weeks of treatment, her stomach became wider and the wizard told her that she was pregnant, and after nine months born a child. However, she could not be born to a child in addition to being exposed to other stomach pains. Related to traditional healers, health practitioners have said that traditional doctors cure different diseases throughout Ethiopia, know how effective it is, and have the ability to treat some diseases that cannot be treated in hospitals. One of the key informants, who are a doctor in a Bichena first-level hospital, said the following:

A lot of these plants and drugs may be good and can treat the problem, but what we are not sure of are the side effects. This is because traditional healers have no absolute measurement and cannot test before usage. From my own view, if these herbs affect the chromosomes or genes, then it is a big problem. Therefore, it is important that traditional healers should do their work in collaboration with modern science doctors and use modern technologies to prepare those medicines (KII3)

Medical coping strategies

Some women experiencing infertility have described how they tied medical treatments in different places to solve their infertility problems. However, some of them stopped the treatment process, as they could not find new and other leave due to financial deficits. Key informants, who are health professionals, said that infertility is a global problem for both men and women and can be treatable. They described that some women have to go to their hospital, consult about their problems, and try to help them based on their problems. One health practitioner said,

As the causes of women infertility are different, the treatment strategy is also different. Some treatments can be given in this hospital and other complicated infertility problems are not treated here and we let them to go to other referral and specialized hospitals. Some treatments are costly and may not be found in every country including Ethiopia. So, they may be the wealthiest people (IDP1 and 2).

Moreover, one of the key informants mentioned that in addition to the expensiveness of some modern infertility treatment strategies, they are time consuming and cause fatigue and psychological distress. Thus, clients may stop the process.

Other ways of coping strategies

In addition to religious, traditional, and medical coping strategies, women experiencing infertility also use other coping methods to solve their problems. However, these methods cannot solve their problems directly and enable them to have children. However, some strategies reduce the pressure, stress, and stigma from other people.

Informal fostering of children- According to the respondents, other people’s children are not yours, whatever you do for them. They mentioned that the legal adoption of children is not the culture of the community and that no one gives children voluntarily, and there is frustration that one day the biological parent will take their children. However, some women experiencing infertility said that their relatives gave some of their children to foster and were seen as biological children.

My aunt has born nine children in row. She never used any contraceptive method and God blessed her a lot. She has given one of her last daughters to me at the age of four and I have cared and fostered properly. I and my husband love her and seen as our biological child. However, sometimes, she said I have two parents. Consequently, I feel sad in some degree. But, she makes my life good and I am better than childless women.(IDP4)

Another infertile woman said that there are three children (one son and two daughters). She loved and fostered them. She is happy at that moment. However, she is considered infertile by other people because these children are not her. Even though she relieved her need for these children, one day, they may go to their biological parents when their mother comes back from abroad (their mother lives in Beirut for work) (IDP5). Regarding the fosterage and adoption of children, the people in the study area did not have good experience and acceptance. FGD participants and most women experiencing infertility have assured that other people’s children are not their own and may eventually go out. It is not practiced by the community and is not supported by culture.

Furthermore, women experiencing infertility raised the problem of fostering children who are not their own is that one day they go out of their home and never come back even for greetings. One of the women experiencing infertility said that she had one infertile woman neighbor in her previous town (Merto Lemariam town) that fostered orphans until they became young adults. However, until now, they have never seen back their fostering mother, even if they are in a good position.

Generally, there is no consensus regarding which coping strategies women experiencing infertility use the most and in priority. This is because they have attempted different strategies such as religious, traditional, medical, and informal fosterage. Women experiencing infertility in Bichena town used combinations of strategies.

Discussion

This study adhered to the social stigma theory, which defines social stigma as prejudice or condemnation directed against a person or group based on perceived traits that set them apart from other members of the community (Goffman, Citation1963). Thus, in the present study, by taking social stigma theory and coping theory as theoretical lens, being infertile is perceived as the characteristics that make women experiencing infertility excluded from society in various forms. According to these findings, the major social challenges faced by women experiencing infertility in Bichena include isolation (self-isolation and social isolation), stigma (self-perceived stigma and social stigma), family and social pressure, and marital problems. This finding is compatible with those of previous studies by Akalewold (Citation2017), Bakhtiyar et al. (Citation2019), Howe et al. (Citation2020), Lawali (Citation2015), and Zhang et al. (Citation2021). For example, Akalewold (Citation2017) found that most women experiencing infertility asserted that they did not like to participate in social activities and preferred also ne. Similarly, the findings of the new study indicate that women experiencing infertility have experienced self-isolation due to fear of criticism and want to stay at home or alone.

Women experiencing infertility in the study area also experience stigma in two forms: self-stigma and social stigma. They were stigmatized by the society around them and perceived stigmatizations. Most of the women experiencing infertility in the study area experienced social stigma, and some experienced perceived stigma. Such findings have been reported in previous studies (Howe et al., Citation2020; Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021). For instance, Howe et al. (Citation2020) found that women experiencing infertility in Zambia suffered from social stigma. The findings confirmed that fertile women and mothers-in-law highly stigmatized women experiencing infertility. Women experiencing infertility are mocked and insulted by society. Supporting these new research findings, Ofosu-Budu and Hanninen, (Citation2021) found that women with infertility were stigmatized by society members around them in various ways. The study mentioned that other people were stigmatized using family planning for a longer period of time by refusing pregnancy.

Women experiencing infertility in Bichena town are also challenged by family and social pressures due to infertility problems. Previous studies validated these findings (Akalewold, Citation2017; Howe et al., Citation2020; Jemberu & Yemane, Citation2018; Saleem et al., Citation2021). For instance, Jemberu and Yemane (Citation2018) found that family pressure is more frequent and severe, hurting women experiencing infertility. Howe et al. (Citation2020) also found that the relationship between women experiencing infertility and their mothers-in-law is harsh and inconsistent because of the children’s need for their son.

Another major finding of this study was the cultural challenges faced by women experiencing infertility. The major findings indicated that women experiencing infertility in the study area were suffering from missing cultural rituals (burial rites, birth day and weeding ceremonies, death memorizations), missing mother care rituals, the challenge of asking newborn mothers, missing full motherhood, and missing value of children. Similar findings were observed in the present study (Howe et al. Citation2020; Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2020; Turner, Citation2020). For instance, Howe et al. (Citation2020) assured the same finding as this study that in Zambia culture, childless women and women who have children do not have the same bury ritual. They (women experiencing infertility) will maybe get an old cob of maize and then put on the butt, and for those who have children; they will just bury them normally. A similar finding was reported by Howe et al. (Citation2020), who explained that women in the Upper Zambezi childless women in Lusaka demonstrate fear of being forgotten by the community after death, and women experiencing infertility reported that when people bury women experiencing infertility, there will be no history. Turner (Citation2020) also stated that, in most African countries, women are considered real women when they bear children. Turner (Citation2020) also found that children are meant to secure care and financial support for their parents in old age.

The coping strategies reported by women experiencing infertility in Bichena town include religious, traditional, medical, and other strategies (informal fosterage). However, there is no agreement regarding which coping strategies women experiencing infertility use the most and in priority. This is because they have attempted different strategies. Similarly, Akalewold (Citation2017) stated, a finding congruent with this study, that there was a strong sense that people often use the three treatment methods (spiritual, traditional healers, and hospital) in combination and in sequence, rather than preferring one method as the most important one. Globally, women experiencing infertility have used different religious activities to cope with infertility challenges (Akalewold, Citation2017; Halkola et al., Citation2022; Karaca & Unsal, Citation2015; Lawali & Abbas, Citation2019; Odek et al., Citation2021). To highlight some previous studies which are correlated with this study, Akalewold (Citation2017) reported that women experiencing infertility used religious activities to solve their problems, such as washing female genitals with holy water and anointing oil prepared and blessed by faith healers. Karaca and Unsal (Citation2015) also mentioned that women experiencing infertility have read the holy Quran, carry on their hands, and massage their stomachs with it. Similar to these findings, women experiencing infertility in Bichena town have prayed and read holy books (such as Holy Bible, miracle of Virgin Saint Mary, books of Kiristos Semra, book of martyr Saint Lalibela), and massaged their stomach and whole body parts with these holy books.

Hiadzi et al. (Citation2021) also stated that infertile urban Ghanaian women who need to test medical coping strategies, such as assisted reproductive technology, call their religious fathers and pray together and receive blessings and good wishes. The same finding was obtained in Bichena town’s women experiencing infertility respondents that they went to their confession father to discuss and pray about their infertility problems. Another finding of this study was that women experiencing infertility in the study area used traditional coping strategies to solve their infertility problems. Women experiencing infertility in the study area visited different wizards and traditional healers to solve their infertility problems. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies (Akalewold, Citation2017; Jaradat & Zaid, Citation2019; Odek et al., Citation2021; Ofosu-Budu & Hanninen, Citation2021). Informal fosterage of relatives’ children is used as a coping strategy by women experiencing infertility in Bichena. However, the study also pointed out that they are not satisfied with such coping strategies as they are not supported by society, and they also feel unsafe that one-day children may go to their real parents. For Nigerian women experiencing infertility, informal and formal fosterage is practiced, but they are also dissatisfied, as reported by Lawali and Abbas (Citation2019).

Conclusion

Women experiencing infertility in Bichena face several major challenges. First, they have suffered from social challenges with isolation (social and perceived isolation), stigma (self-perceived and social stigmas), family and social pressures, marital problems, and low social status. Second, they are also challenged by cultural variables such as missing cultural rituals (burial rites, mother care rituals (40 days care)), death memorization, missing full motherhood, asking new born mothers, and missing the value of having children. Society is not seen to understand and support women experiencing infertility in finding solutions but has stayed in exerting pressure, isolating, and stigmatizing women experiencing infertility. Society also does not treat infertile men and women equally. More burdens are placed on women experiencing infertility. Finally, to overcome those challenges, women experiencing infertility also reported using different coping strategies to solve their problems. Spiritual (religious) strategies, traditional strategies, medical strategies, and informal fosterage were identified in this study.

Implications and future directions

As a theoretical implication, the findings of the study hoped to fill the gap by addressing the social and cultural challenges of infertility among women and thereby add value to the current literature. Women experiencing infertility use different coping strategies in combination. However, the researchers would recommend to them that they should not go to wizards who need to have unwanted sexual intercourse with them for the born baby. Society’s traditional organizations such as idir, mahiber, iqub, and similar organizations shall provide positive support for women experiencing infertility. Bichena health office management body and Bichena first-level hospital management body shall work together in collaboration and plan to assess women experiencing infertility in the town and provide possible medical and psychological treatment services to solve their infertility-related challenges. The hospital sends psychiatrists to study and support women experiencing infertility’s stress, anxiety, and depression. NGOs help women experiencing infertility financially or by other means cope with their problems. Bichena town has a world vision. Therefore, this organization should initiate support for women experiencing infertility. The Ministry of Health and Education shall recruit trained community counselors and psychiatrists for the town by considering infertility as a public issue and reducing challenges. Any interested investigators, such as developmental psychologists, counselors, nurses, psychiatrists, and others, shall study this new and global challenge based on their own perspective, either qualitatively or quantitatively to add further understanding about infertility and to pave the way for modern treatment strategies so that women experiencing infertility become empowered and resist better in their lives.

This study was also limited to one town, Bichena town; thus, the study can be expanded by including various towns and districts where cultural influences on social and cultural challenges and coping strategies of women experiencing infertility may or may not differ. However, this study serves as a basis for other scholars to study the current issue. Some respondents may have biased views owing to their cultural background or personal views, which affect the findings of the study (Zhang et al., Citation2021). Using several participants through a questionnaire is crucial to attain a more objective conclusion. Moreover, with a descriptive phenomenological design, by collecting data at one time, it is less likely to infer the general social and cultural challenges and coping mechanisms of women experiencing infertility. Therefore, future scholars should use longitudinal study designs to provide more conclusive and substantiate information, and this study was not cover the views of infertile men. The study was conducted through the utilization of various data collection sources for men as a survey and reference.

Author contributions

All TBA, KZB and AAS were involved in the conception, analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be available by requesting the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tinisaie Biadigie Adane

Tinisaie Biadigie Adane is Developmental Psychologist and lecturer at Mekedela Amba University.

Kelemu Zelalem Berhanu

Kelemu Zelalem Berhanu is a senior postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Abatihun Alehegn Sewagegn

Abatihun Alehegn Sewagegn is an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at Debre Markos University, Ethiopia and a research associate at the Department of Educational Psychology, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

References

- Akalewold, M. (2017). Psychosocial problems of infertility among married men and women in Addis Ababa. Implications for Marriage and Family Counseling, 60,1–70.