Abstract

Perpetual peacebuilding needs inclusive, participatory, and transformative approaches. The practice of conflict approach determines the resolution and relapse of conflicts. This study focuses on the nature and experiences of conflict interventions in the Guji-Burji protracted inter-ethnic conflict. The study uses a qualitative research approach. The data were collected from primary and secondary sources through interviews, FGDs, and document analysis. As per the findings, the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict is cyclical and has caused devastating human security impacts. The structural cause of the conflict lies in the failure of ethnic federalism over boundary conflict and ethnic politicization in post-1991. It is also fueled by the proliferation and illegal use of small arms, dacoity and rhetorical honor, diversion and the ethnicization of micro disputes, and an untransformative approach to conflict interventions. The conflict approaches have failed to address the parties’ positions, interests, and needs to achieve perpetual peace, which is most crucial. Besides, the intervention approaches are not inclusive, participatory, integrated, and transformative but rather partial, politicized, and ethnocentric. Therefore, it requires a transformative approach to intervention that addresses the genesis of the conflict through boundary resettlement, profound community dialogue, and unconditional forgiveness to build trust and realize sustainable peace.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

In the field of conflict and peace studies, the term peacebuilding has become an increasingly evolving concept. The feasibility of peacebuilding was limited to intervention in post-conflict countries for a long time. However, the end of the Cold War and particularly the 1990’s brought new outlooks of comprehensive, broad, and expansive understanding of the concept and practice of peacebuilding. Moreover, following UN Secretary General Boutros-Boutros Ghali’s argument in ‘Agenda for Peace’ in 1992, peacebuilding understood as a range of activities and community practices anticipated to identify and support structures that strengthen and consolidate peace by addressing and transforming the root causes of the conflict (Ghali, Citation1992). From then onwards, peacebuilding activities involve the development of local social institutions through which societies can manage their own concerns (DeConing & DeCarvalho, Citation2013). Peacebuilding as a community practice aims to promote long-term social solidarity and social justice through rehabilitation and reintegration practices (Evans et al., Citation2013). Thus, peacebuilding is a continuous practice in the constructive transformation of conflicts for cooperative social and personal relationships through justice and reconciliation (Hizkias, Citation1993).

Indeed, successful peacebuilding becomes challenging in the absence of comprehensively integrated and participatory trends among various actors and stakeholders. For instance, on the one hand, the predominantly top-down and modern approach to conflict management neglects the needs and interests of the local conflict situation and the future relations of parties in general (Dezeuw, Citation2001). On the other hand, the bottom-up approach used by customary conflict resolution mechanisms, guided by restorative justice principles, and inclined toward the whole community, focuses on more reconciliation than a fair trial (Buhari, Citation2013; Daniel, Citationn.d.; Murithi, Citation2006). Accordingly, the critical challenge that has faced human beings in peacebuilding is the use of inappropriate and unintegrated mechanisms without considering and balancing all levels of stakeholders (Buhari, Citation2013).

In Africa, many conflicts have been attempted to normalize and resolve with a wide range of modern conflict resolution approaches and mechanisms but failed to control their reoccurrences and persistence. Because the top-down and modern approaches lack understanding of the context and undermine the wisdom of African indigenous conflict approaches, which originated from the cultural setting of the conflict (Mafro, Citation2014; Murithi, Citation2006; Zartman, Citation2000). However, in the post-colonial period, many African states attempted to try to value and recognize indigenous mechanisms in conflict resolution with the African customary court system (Murithi, Citation2006). Hence, among the indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms that have provided lessons in reconciliation of ethnic-based conflicts and peacebuilding in Africa are Maot-oput in Uganda and Gurritt in Somaliland (Murithi, Citation2006), and the Gada system in Oromo, Ethiopia (Abbink, Citation2011; Asebe, Citation2007; Bantayehu, Citation2016; Gololcha, Citation2015; Taddesse, Citation2009). In addition, Gacaca, as a customary court, played a significant reconciliation role in Rwanda (Mutisi, Citation2012).

As a multi-ethnic country with ethnic based federal administrative structure, ethnic conflict is hardly new in Ethiopia, particularly in post-1991 (Bassi & Tache, Citation2011). Mostly, inter-ethnic conflicts have prevailed among pastoralists and agro-pastoralists in southern Ethiopia. Among others, the protracted inter-ethnic conflicts of Oromo within Oromo (Guji, Borana, and Gabra); Oromo with Somali pastoral ethnic groups (Marihan, Dogodi); and Garri of the southern and eastern parts of Ethiopia are common over resources like pastureland and water (Taddesse, Citation2009). Guji Oromo has recorded violent conflicts and a history of confrontation with its adjacent ethnic groups like Burji, Borana, Konso, Garre, and Koyra (Adane & Engida, Citation2022). The Guji Oromo also have a chronically destructive conflictual relationship with Gedeo (Asebe, Citation2012). More specifically, the on-and-off natures of the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict are the most protracted, with devastating human security impacts (Borenton and Yilma, in Ruth, Citation2017). The conflictual relations between Guji and Burji started at the end of the imperial regime and continued in successive political regimes. However, it has worsened and become more protracted since the introduction of ethnic federalism in 1991. Thus, the persistent nature of the conflict forces the ethnic groups to consider each other as enemies (Asebe, Citation2012; Gololcha, Citation2015; Ruth, Citation2017; Taddesse, Citation2009).

The rationale of the quest for conflict transformation as a base for sustainable peacebuilding is its unique approach to changing the intertwined aspects of attitude, context, and behavior in the conflict (Dijk, Citation2009; Lederach, Citation1997). In the Guji-Burji ethnic conflict, the nature of conflict interventions in the quest for sustainable peacebuilding has hardly been dealt. Therefore, this study focuses on examining the nature and experience of conflict interventions in the quest for sustainable peacebuilding.

Conceptualizing conflict approaches in peace building

Peace building is an evolving concept which becomes widespread in the post-Cold War period. In 1992 the UN Security General Boutros Ghali in his ‘Agenda for Peace’ stated it as an action to identify and support structures to institutionalize peace (Ghali, Citation1992). Peace building is a process and continuous co-operative communities’ effort to enhance mutual understanding and open dialogue through dissipating the prevailing distrust, fear, and hate (Last, Citation1999). It needs a transformative conflict approach that allows a multidimensional changes and multiple actor engagement. Peace building is an effort to create a structure of peace that is based on justice and cooperation thereby addressing the underlying causes of violent conflict and the grievances of the past (Gawerc, Citation2006). Thus, as an umbrella concept peace building encompasses more inclusive and transformative efforts of interventions (Aliff, Citation2014).

Lederach (Citation1997) developed a framework to properly comprehend the purpose and objectives of conflict approaches in the field. These are: first, viewing the conflict from two variables: balance of power and awareness of the conflicting interests and needs, thereby the process of conflict resolution and peacebuilding occurring in correspondence between the matrixes of these variables. Second, focus on using adequate descriptive language to describe interventions and their mutual interactions. Arguably, while dealing with conflicts, we must note that the key goal of conflict intervention should not be to foster one particular outcome but to alter the overall patterns of interaction of the parties (Coleman, Citation2006). Lederach argued that persistent and protracted conflicts have not been observed merely by their nature but also by the defect of interventions in the conflict approaches (Lederach, Citation1997).

Conflict management is the strategy of intervention to achieve political settlements, particularly by those powerful actors who have the power and resources to put pressure on the conflicting parties (Osagahe, Citation1997). Conflict management theorists perceive violent conflict as an ineradicable consequence of differences over values and interests between communities, particularly narrowing and discerning the dynamics of ethnic conflict (Lederach, Citation1997; Osagahe, Citation1997). Resolving such conflicts is viewed as unrealistic, and the best that can be done is to manage and contain them (Miall, Citation2004).

Unlike conflict management, the notion of conflict resolution implies a once-and-for-all treatment of conflicts. This has been done through addressing the underlying causes of a conflict to attain common interests and overarching goals (Hilal, Citation2011). Proponents of conflict resolution reject the powerful political view of conflict, and they argue that it is possible to transcend conflicts if parties can be helped to explore, analyze, and reframe their positions and interests. Therefore, conflict resolution is a way to move from zero-sum game, destructive patterns of conflict to positive-sum constructive outcomes with new thinking (Amare, Citation2012; Lederach, Citation1997).

Most importantly, unlike others, the language of conflict transformation is favored in peace-building scenarios, particularly for protracted nature conflicts. Lederach stated two points in this regard (Lederach, Citation1997). At first glance, conflict transformation captures the dialectical nature of conflict and a holistic approach to understanding the conflict process. Second, conflict transformation as a concept is both descriptive of the conflict dynamics and prescriptive of the overall and deepest levels of cultural and structural peacebuilding. Beyond conflict resolution, tasks of conflict transformation significantly ensure that behavior is no longer violent, attitudes are no longer hostile, and the structure of the conflict is transformative (Amare, Citation2012). Contemporary conflicts require not only the reframing of positions and the identification of win-win outcomes but also the transformation of relationships, attitudes, context, and discourses simultaneously and, if necessary, the very constitution of society, which supports and purports the continuation of violent conflict (Dijk, Citation2009; Lederach, Citation1997). Finally, as Galtung stated in his transcend approach, conflict intervention approaches and sustainable peace-building tasks should be capable of transforming conflicts through multidimensional, consolidative, integrated, and long-run-driven measures (Galtung, Citation2007).

Conventionally, actors and stakeholders in conflict intervention practice have not been differentiating the language and usages among the different conflict approaches and their intended unique purpose. They have not been recognizing the context of conflicts and the principles of sustainable peace-building practices. The inappropriate use of the conflict approach led to the relapse of conflicts and the failure to ensure sustainable peace. Depending on the nature and context of the conflict, actors in conflict intervention should considerably prefer and use the best-fit mechanisms among the existing approaches, i.e. conflict management, conflict resolution, and conflict transformation. Therefore, to target sustainable peacebuilding, the practice of conflict intervention approaches needs to be rehearsed and reconsidered in favor of a more transformative approach.

Materials and methods

This study employed a qualitative research approach. A qualitative approach is pertinent for social science research to explore, investigate, and understand events, theories, and human behaviors in depth (Creswell, Citation2007; Kothari, Citation2003). The qualitative approach allows for answering what, how, and why questions in research (Paton & Cochran, Citation2002). Accordingly, the researcher used a qualitative approach to develop a comprehensive understanding of the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict and the nature and experiences of its interventions. This has been done through exploring and investigating the attitudes, insights, views, understandings, and actual experiences of participants in a natural setting. Considering the research objectives, which need deep exploration and investigation, the study used exploratory qualitative research design. To this end, subjective and interpretive types of qualitative data were collected from both primary and secondary sources through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), and document analysis. These different tools of data collection are used to assure data validation. It also used a semi-structured interview to collect the required data. The data analyzed through the procedures of data translation, transcription, clustering, interpretation, and discussion. For this study, 42 participants (of whom 18 from Burji and 24 from Guji) were interviewed. In addition, 28 participants in four FGDs (of which two groups were from Burji and two from Guji) were organized. The research participants were elders, Abba Gadaa, religious leaders, youths, officials, and security personnel. The participants were selected through a non-probability type of purposive sampling technique. The interview continued until the data saturation level was reached. Finally, as per their interests and research ethics, the names of the interviewees preferred to be anonymous, and they used their status.

Background overview of Guji and Burji ethnic groups

Oromo is one of the largest nations in Ethiopia, and the Guji are Oromo who have been living in southwest Ethiopia. Until 2016, the Guji were under Borena zone administration. Since then, Guji has been under a newly established zone called the West Guji Zone. The center of this zone is Bule Hora. Like other Oromo branches, the Guji have a long-lived social, political, and cultural system of governance called the Gadaa system. The Gadaa system is an indigenous institution in Oromo communities that is widely practiced and governs their interactions. The Guji Oromo are well known for the practice of the Gadaa system in the justice administration and conflict resolution. Abba Gadaa are wise men who play a leadership role in the Gadaa system. They are respected leaders and conciliators in the Oromo communities. From a cultural perspective, the Guji Oromo have rich cultural values, norms, and ritual practices that guide the communality of the group. From an economic viewpoint, they are merchants (a few who have been living in the town), pastoralists, and agro-pastoralists. The Guji Oromo share adjacent boundaries with other Oromo branches and other ethnic groups. Hence, the Guji adjacents are Burji, Konso, Kore, Sidaama, and Gedeo from the previous south nation nationalities and peoples regional state; and Borena and Arsi from the Oromo branches (Ruth, Citation2017). More specifically, the Guji pastoralists have shared a border with the Burji district (Asebe, Citation2012).

Burji had been administered as a special district in the previous southern nation, nationalities, and peoples regional state since the advent of ethnic federalism. However, since 2023, following the disintegration of the southern nation, nationalities, and peoples regional state, Burji has been belonging to and administering to the newly born region called central Ethiopian peoples. Burji and Guji were under a single political administration before the introduction of ethnic federalism in Ethiopia in 1991. Following this, the Burji have their own socio-political self-administrative system. The center of Burji’s special district is called Soyama. So far, the Burji shares a boundary with Guji in the northeast, Amaro in the north, Konso in the west, and Borena in the southwest. Economically, the Burji are highly dependent on agricultural livelihoods. Due to the historical proximity and co-existence of Burji and Guji, many Burjis have lived in Bule Hora, the town of west Guji zone. They have shared common cultural values and social capital. Thus, they are interconnected through marriage and other human-life interactions.Footnote1

Historical relationships and conflict profiles of the Guji-Burji ethnic groups

Historically, the interactions of Guji and Burji ethnic groups have reflected positively on shared ways of life. This has been conveyed in economic, political, social, and cultural interdependence. However, the complexity of socio-economic life and competition over resources have interrupted their smooth interactions. At the end of the 1960s, there were tensions between Guji and Burji, and their historic positive relations began to be fragile. Following that, the fragile interactions between Guji and Burji have been examined in terms of historical, cultural, political, social, and economic situations.Footnote2

The different consecutive political regimes in Ethiopia have imposed tensions on the interaction between the Guji and Burji ethnic groups. In the year 1976, there was an incident of massacre against 377 Guji in Surro (a place in Guji) by the military regime. Here, the Guji strongly believed and blamed the way that the Burji organized the massacre by allying with the regime. This was one of the unforgettable millstones that blurred Guji-Burji relations. Undeniably, the accident has left historical discrepancies and traumas that remain untransformed. Thus, such historical discrepancies feed for hostility and vengeance between Guji and Burji.Footnote3

Consequently, in the late 1970s and early 1990s, Guji and Burji engaged in conflict with revenge and counter-revenge, which further protracted their sense of enmity (Asebe, Citation2012). Afterward, they have had a record of cyclical conflictual relations. Along with the coming of ethnic federalism, there have been periodic killings that manifest in on-off situations. Many violent conflict incidents between Guji and Burji have been recorded under the regime of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) with massive human security implications, particularly in the years 2008, 2010, and 2017.Footnote4 Asebe further contended that since 2008, Guji and Burji have been in off and on conflict situations with complex security threats including social despair, instability, killings, and political tension (Asebe, Citation2012). Thus, the threats, suspicion, disillusionment, and periodic violence have been making the area a zone of insecurity with enormous human security complications.

Causes of the Guji-Burji ethnic conflict

Root causes

Ethnic federalism and its failure over boundary with ethnic polarization

In 1991, succeeding the revolution and collapse of the military regime, Ethiopia established the ethnic based federalism and reconfigured the state administration along ethnic line. Following this, the new constitution established the nine regional states and two self-administration cities (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) (FDRE, 1995). Indeed, the Ethiopian ethnic federal system gives recognition of ethnocultural diversity, self-governance, and unconditional right to self-determination up to secession. However, looking to the practice, it oversimplified and undermine the long-lived coexistence, shared values, beliefs systems, and future aspirations of the people (Takele, Citation2021). The Ethiopian ethnic federalism proved non-viable in practice and the federal constitution verified antagonistic to the inherited politico-cultural orientations that posited the nation-state as the principal supranational identity (Ogbazghi, Citation2022). The current constitution of Ethiopian institutionalize ethnic groups as fundamental constitutes of the state (Alem, Citation2003). Under this ethnic based state political administration, the institutionalization of ethnic groups as fundamental constituents along with unconditional rights of self-determination up to secession highly threatens the state disintegration. Evidently, now a day, from the nine established regional states in 1991; the southern nation, nationalities, and peoples regional state disintegrated into different new regions namely Sidama, southwest Ethiopia, central Ethiopia peoples. Thus, the deconstruction of the shared national identity and an emerging ethnic identity have been continued as the challenge and threat to national consensus and unity in Ethiopia.

Wherever the national policy of state administrative structure of land bases an ethnic line, it creates ethnic tension and would put inter-ethnic interactions into trouble over unclear and contested boundaries (Barth, Citation1969). In Ethiopia, theoretically, ethnic-based federalism was introduced with aimed at promoting equality and accommodating ethnic and cultural differences between nations, nationalities, and peoples. There are different competing political discourses and views on the deliberation of Ethiopian ethnic federalism. On the one hand, the proponents have strongly argued that ethnic federalism is the only possible solution to redress the past discrimination and injustices in Ethiopia (Mengisteab, in Asebe, Citation2012). Federalism offers an excellent opportunity for the accommodation of intra-regional ethnic diversity like the southern nation, nationalities, and peoples region in Ethiopia (Van der Beken, Citation2013). On the other hand, others strongly opposed the advent of ethnic federalism by pointing out that many inter-ethnic conflicts in post-1991 Ethiopia have occurred due to ethnic-based administration (Dereje, Citation2009; Luba, Citation2012). Ethnic federalism has left contested issues, including an unclear administration boundary, overlooked cross-cutting variables, titular vs. settler problems, politicized ethnicity, and mega-ethnic syndrome (Takele, Citation2021). He concluded that it has created new troubles in terms of ethnic tensions and conflicts across Ethiopia. Under ethnic federalism, the Ethiopian experiment shows an increase in ethnically inflicted hostility. Thus, some of those inter-ethnic conflicts include between Dirashe and Gauwwada, Borana and Somali, Konso and Borana, Gumuz and Oromo, Silte-Gurage, Sheko-Megengir, Anuak-Nuer, Berta-Gumuz, Gedeo-Guji, Oromo-Amhara, Borana-Gerri, Afar-Issa, Oromo-Somali, and Guji-Burji conflicts. Hence, this newly redrawn ethnic based political administrative structure polarizes group distinctions and politicizes ethnic identities.

In Africa, ethnic tensions pestilence not due to differences in cultures and ethnicities but to the character and determination of state builders (CGAR, Citation2009). In a state, the nature, interest, and commitment of political elites and leaders matter the inter-ethnic relations and the nation building process. The redrawing of administrative boundaries with less emphasis on historical relationships is awful for groups to develop new identities. It is also difficult to come up with agreements for resource sharing with the newly separated groups over contested areas. In post-1991 Ethiopia, the newly redrawn ethnic-based administrative structure has caused the outbreak of several ethnic-based violent conflicts. The Guji-Burji protracted inter-ethnic conflict has emerged following the redrawn of Burji under the southern nation, nationalities, and people’s regional state, and Guji to the Oromia regional state. This has left a continual territorial claim and continued as the center of instigation of violence in the complex identity politics.Footnote5

In Ethiopia, ethnic federalism has created unclear administrative boundaries along the shared borders with claims and counter claims over the same land which made the demarcation process protracted, including between Oromo and Somali (Takele, Citation2022). The boundary and resource-based conflict between the Guji and Burji is in the area called Dollcha Valley. The Guji pastoralists who are living around the border have a seasonal mobile livelihood in search of grazing land. The Guji have claimed Dollcha Valley as their own land exclusively by ascribing and referring to a man’s name, Dollcha, as Guji. On contrary, the Burji have an agricultural livelihood through plowing farmland and the cultivation of crops. The agriculturalist Burji attempted to seize and use this contested area. Debatably, both have competing interests and claims over the area. The Guji believed that the Burji used all their respective lands around the border of Dollcha Valley.Footnote6 On the contrary, the Burji have a continual claim over their previous lands, which were demarcated into Guji and Borena zones under the new ethnic based federalism.Footnote7 Concerning this, Asebe disclosed that the Burji are still claiming those territories that were previously under their jurisdiction (Asebe, Citation2012). Therefore, the divergent and competing interest in the area and its resources makes the conflict more protracted and reinforce the groups feeling like enemies.

Trigger and proximate causes

The proliferation of illegal small arms

The proliferation and misuse of small arms have continued to fuel conflict-ridden society in the Horn of Africa. Concerning this, the Nairobi Declaration was signed in 2005 by states to control the proliferation of illicit small arms and light weapons in the region (Griffiths-Fulton, Citation2002). As part of the Horn of Africa region, in southern Ethiopia, the accessibility of small arms has immensely contributed to fueling and aggravating the existing discontent and historical discrepancies of the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic groups. The area is highly vulnerable to illegal trading and the contraband of small arms. Many individuals in the community have small arms. The presence of small arms in the hands of individuals lets them shout for every dispute and disagreement between the groups, which exacerbates the existing discrepancies and hostility.Footnote8

Dacoity, cattle rustling, and rhetoric honor

Cattle rustling in pastoral communities has been involved in two outbreaks (Mkutu, Citation2000). One, seek grazing lands and livestock in the very scarce resources. Two, it is considered a culture of warriors who raided weaker communities and took away their animals. In the Horn of Africa, cattle rustling is the most prevalent source of conflict in pastoral societies within and across the state. This is also common in pastoralist communities in Ethiopia. Cattle rustling between the pastoralist Guji and agriculturalist Burji prevails around their borderline. It is activated by outlaws and knaves who want to destabilize the area for their hidden political agenda and economic benefits.Footnote9 This has been done through killing and stealing cattle and camels from Guji pastoralists in the name of Burji; damaging Burji’s crops by burning and exposing for livestock; and killing Guji’s man by pretending as it happens by Burji. Whenever this happened at the border, the conflict immediately extended even into the towns with ethnic-based violence, specifically at Bule Hora (where both ethnic groups are living). Dacoity has served their business and personal interests, inter alia, small arms circulation and stealing camels, cereal, warehouses, and shops. In addition, government officials from both ethnic groups implicitly support and finance the dacoity groups to secure and extend their political goals by manipulating the issues.Footnote10

In Guji Oromo, it was historically accepted and honored to be a brave man in the community by killing and castrating another man. The Guji-Oromo are viewed as warriors because they are often in conflict with neighboring ethnic groups like Gedeo, Burji, Borana, and Sidama. The Guji-Oromo are often engaged in war with their neighbors mainly due to the prestige attached to killings (Asebe & Tadesse, Citation2018). Though modernity and religion have diminished the acceptability of honor killing in the population, it is not eliminated or obliterated. Therefore, such traditional honor of the bravest also inflicted the protracted Guji-Burji ethnic conflicts.Footnote11

Diversion and ethnicization of conflicts

The politicization of ethnicity by ethnic entrepreneurs and self-seeking political elites inflicted ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia. They exploit the political-economic grievances for their personal interests by mobilizing their affiliated ethnic group which troubles the peaceful coexistence of the groups (Takele, Citation2021). The diversion of micro interpersonal discontents and conflicts to ethnic-based conflicts led to visible differences and masked the existing shared values. In Bule Hora town (Guji zone), the Burji are the largest dwellers next to the Guji who own the administration. Due to their long togetherness, they are interconnected through intermarriage and shared socio-cultural values and practices. Nevertheless, whenever trivial and coincidental interpersonal disputes arise between individuals of the two ethnic groups over their immediate personal interests, the conflict diverts to ethnic-based. It has routinely happened that identity becomes a precondition to seize the side of the group instead of judging the case based on humanity and impartiality. In Ethiopia, under ethnic federalism, most political elites have been playing a negative role in manipulating and instigating conflict by mobilizing their respective ethnic group against each other to secure their political and economic interests (Takele, Citation2021). In the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict, youths, as victims of unemployment, are highly manipulated by ethnic entrepreneurs to be sensitive towards their ethnic group and shift the focus of every conflict to ethnic-based.Footnote12

Indigenous knowledge of conflict resolution mechanisms in the Guji-Burji conflict: transformative or not?

The term ‘indigenous’ refers to the view of inherent and place-based human ethnic culture and practices (Stewart, Citation2018). As a mechanism, it is a locally agitated set of activities, practices, usages, and norms that are capable of social adaptation and reform (Stewart, Citation2018). In conflict resolution, it is familiar or interchangeable with terms like traditional, customary, alternative, informal, or non-state dispute resolutions. Anthropologists understand indigenous knowledge as a set of traditional institutions and practices derived from the past and even operating in modern society (Ekeh, 1983; Weber, 1977 cited in Zartman, Citation2000). Zartman also stated that indigenous knowledge of conflict resolution mechanisms is a traditional medicine for modern conflicts. Indigenous knowledge of conflict resolution mechanisms is derived from the social, cultural, and spiritual worldviews and experiences of the community (Zartman, Citation2000). They are community-based and context-specific in their approach to reconciliation, which aims to resolve the root causes of the conflict, transform the context, and restore relationships (Bozeman, Citation1976).

Sustainable peacebuilding could be effective if we transcend the conflict by reframing and addressing parties’ positions, interests, and needs. Indeed, transformative theorists argued that conflict intervention should emphasize reframing position and interest and need to penetrate in-depth into the very nature of parties’ relationships, discourse, structures, and contexts that embedded the conflictual relations (Lederach, Citation1997). There needs to be more work on conflict approaches and interventions targeting sustainable peacebuilding.

In southern Ethiopia, the Guji Oromo conceived ‘peace as not a free gift’ but rather a need for unreserved community efforts, social actions, and the commitment to continuous negotiation, open dialogue, and cooperation that promote sustainable peaceful coexistence (Asebe & Tadesse, Citation2018). In the Guji-Buri inter-ethnic conflict, the intervention approaches need to be examined from transformative and sustainable peace building perspectives. Under the Gadaa system, Abba Gadaa has attempted to reconcile the Guji-Burji conflict through Gondoro indigenous reconciliation mechanisms and ritual ceremonies.Footnote13 To this end, Abba Gadaa formulates rules and regulations that administer and oversee the interaction in the Guji Oromo. In Guji Oromo, Gondoro is a psycho-social truth-telling and truth finding method of indigenous conflict resolution and justice administration. The Guji use Gondoro for blood purification in the case of homicide. Indeed, Gondoro is more effective in reconciling interpersonal types of serious conflicts and homicides. For instance, elders revealed that homicide happened in the community, causing displacement of families and disruption of students’ education. In this case, Abba Gada intervened and addressed the issue through the Gondoro reconciliation mechanism. Here, Gumi (Citation2016) also argued that Gondoro in Guji Oromo represents a unique model of reconciliation and restorative justice through psycho-social trauma healing. Cultural practices and ritual ceremonies take place in the Gondoro reconciliation process. During the reconciliation, the conflict parties, Abba Gadaa, religious leaders, and security personnel assembled at the preferred area. After discussion and dialogue, there is a slaughtering goat to let the parties eat together. Finally, the conflicting parties swear to heal, forgive, and finally, Abba Gada gives a blessing as a concluding remark.Footnote14

Nevertheless, in post-reconciliation, the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflicts have relapsed. Several factors have contributed to the relapse of the conflict. One is the limited role and ineffectiveness of the indigenous approach to interventions in inter-ethnic conflict. Gondoro is effective in reconciling interpersonal homicide. It has limited capacity to scale up its effectiveness for conflicts across ethnic groups including in the Guji-Burji ethnic conflict. In its nature, Gondoro is confined to ritualistic activities in the reconciliation process which makes it difficult to transform politicized and protracted types of inter-ethnic conflicts (Desalegn et al., Citation2005). Two, the influence and interest of political elites make the indigenous approaches to conflict interventions imperceptible. Indeed, when community-based conflict resolution mechanisms and institutions are no longer perceived as legitimate, the conflicts cannot be transformed. In the Guji-Burji conflicts, the interests of political elites override the local realities of the conflict and disregard indigenous mechanisms and practices. Three, the advent of modernization and the proliferation of religions disregard and undermine the culture-based rituals and ceremonies of the indigenous mechanisms. Hence, the Gondoro reconciliation practice has faced challenges from a lack of acceptance of Gadaa’s rules, disrespecting Abba Gadaa’s decisions, and the absence of conflicting parties’ consensus.Footnote15 To conclude, the reconciliation approach of the Gondoro indigenous mechanism in the Gada system is unable to transform the context, behavior, attitude, and relationships in the Guji-Burji conflict.

Government interventions: violence management not last remedies

In a democratic society, the government is responsible for promoting and safeguarding the peace and security of its people. It could be through conflict prevention, management, peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peacebuilding, particularly in conflict-affected societies. A range of activities, from military intervention to institutional reform and structural changes need to be undertaken in the peacebuilding process. The contexts of the conflict need to be transformed to restore the distorted relations and build trust in the future. Conversely, government-driven interventions are conflict management in their very nature by neglecting the dynamic nature of the conflict and its transformation (Osagahe, Citation1997).

In Ethiopia, there are established institutions and constitutional mechanisms in charge of conflict prevention and resolution whenever inter-ethnic tensions and conflicts prevail. In doing so, the House of Federation bears the responsibility to identify and mitigate ethnic conflicts over boundary and resource competition (FDRE, 1995). In Africa, the constitutional mechanisms of conflict management are reluctant to address different competing ethnic tensions (CGAR, Citation2009). Likewise, the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict has been prolonged due to unenthusiastic government actions and its concerned institutional failure. The federal and regional governments are reluctant to promote the rule of law and control conflict entrepreneurs. In a nutshell, the government neither attempted to address the root causes nor tightly cooperate and integrate with indigenous institutions and other concerned stakeholders to transform the conflict beyond management.Footnote16

The Guji-Burji conflict in onion model analysis

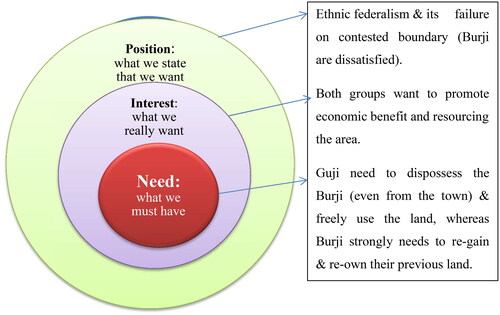

The invisible and inconsistent demands of parties in conflict are one of the critical challenges in transforming conflicts across ethnic groups. This is because of the conflict parties’ deep-rooted and dynamic claims which range from the visible to most hidden desires. In this case, an onion model of conflict analysis is imperative to address the parties’ positions, interests, and needs. Ranies (Citation2013) understood these dynamics as first, position, which is the more visible and outer layers of the conflict, implies what the parties state that we want. The second is interest, which signifies what the parties really want to achieve and what motivates them to do that. The last is need, which dictates what the parties must have. This is the most hidden and crucial element of a group’s desire in the dialogue unless they can get out of the conflict. Therefore, to transform conflicts sustainably, the dynamics and layers from the more visible to the hidden at the heart of the conflict need to be profoundly addressed.

In the Guji-Burji conflict, the conflict parties from both sides have reframed their own positions, interests, and needs that they want to secure. From the side of Burji, the structural cause of the conflict, which relies on ethnic federalism and boundaries, has been taken as the parties’ position in that they are dissatisfied with it. Whereas the Guji are praising the system in which they are benefited.Footnote17 Because of this, the interest which motivates the parties is the economic and resource advantages in the area. At its core, need, the deepest and hidden desire that parties invisibly claim and want to secure in the Guji-Burji conflict is feared to talk during the reconciliations. The Guji have developed a potential fear of administration and self-determination claims by the Burji in Bule Hora, Guji zone, so that they want to dispossess them (Ruth, Citation2017). In doing so, whenever disputes arise even between individuals of these groups at the border or in a town, the Guji activates the conflict to displace the Burji.Footnote18 On the contrary, the Burji have a strong demand to re-own their previous land which was demarcated to Guji in 1991.Footnote19 Thus, to build sustainable peace between Guji and Burji, conflict intervention approaches need to be framed in terms of addressing the conflicting parties’ positions, interests, and needs ().

Figure 1. Guji-Burji conflict in onion model conflict analysis.

Source: Adopted from Ranies (Citation2013).

Potentials of transforming Guji-Burji conflict

Boundary resettlement: cooperatively, not competitively!

In post-1991 Ethiopia, ethnic-based federalism and its boundary demarcation have caused the outbreak of several ethnic-based conflicts. Following this, resources and boundaries become the pressing issues of inter-ethnic conflicts with the ethnicization and the polarization of identities. Conflicts, particularly in pastoral and agro-pastoral areas, became more evident with the territorial reconfiguration of the country on an ethnic basis (Asebe, Citation2007). The current state administrative structure is organized along with ethnic lines which ignores cross-cutting variables and historical interactions. Since the problem is structural, there need to reorganize the administrative territory considering the mutual development potential and future peaceful coexistence (Takele, Citation2021). The Guji-Burji conflict relies on claims and counter claims of the land on the border. The government has attempted to re-demarcate this contested area, but the conflict relapsed in the aftermath. This is because of the interest of the Burji to regain and exclusively control the claimed area as it was their previous land. Looking to indigenous conflict interventions, Abba Gadaas has played a role in making reconciliation between Guji and Burji though it could not be transformative and ensure perpetual peace. Abba Gadaas are not effective in reconciling such kinds of ethinicized and politicized nature of inter-ethnic conflicts. Evidently, they have not resolved cross ethnic conflicts which occur with natural resource claims (Desalegn et al., Citation2005). Thus, the Guji-Burji conflict remains persistent, and it decisively requires a political measure. As Takele argued creating an inclusive governance for development opportunities on the shared and contested border provides immerse contribution to promoting mutual benefits and togetherness (Takele, Citation2021). Elders and officials from both sides strongly disclosed the reconciling view that making and resourcing the contested area as a joint development zone, cooperatively not competitively, can be a window of opportunity to settle the prolonged overlapping interests over the boundary.Footnote20

Profound community dialogue and unconditional forgiveness: talking not fighting

The pattern of conflict reactions and their dealings determine the life cycle of conflict. These patterns of reactions are fighting, flighting, and talking or openness. The flight strategy of conflict reaction dictates that the parties run away physically and emotionally by ignoring the issue, denying the problem, and undermining the relationship. Again, the fighting mode of reacting to conflicts also commands the parties to show aggressive behavior and take the issues as their own via vengeance, irony, physical or psychological violence, and patronizing behavior. In these modes of conflict reaction, there is no room for communication. Whereas openness acknowledges that conflict is natural, and that we are part of it as long as we have been interacting (Vestergaard et al., Citation2011). Therefore, the nature of conflict interventions in the Guji-Burji protracted conflict needs to be viewed in line with the very nature of the conflict reactions.

As a restorative justice model, participatory and community dialogue-based reconciliation assures trust-building between the conflict parties, particularly in ethnic conflicts (Notter, Citation1995). To build mutual understanding and trust, people to people initiatives and dialogue become crucial in the conflict affected communities (Gawerc, Citation2006). In the Guji-Burji conflict, there is a need for all-inclusive community dialogue and unconditional forgiveness of the historical discrepancies. Profound community dialogue helps to find the shared truth. This elegant idea of dialogue dictates the notion that there is no one truth; rather, each of us carries our own distinctive memories, which may contradict each other (Souto, Citation2009). The truth of contending and contradicting historical discrepancies and shared memories needs to be reconciled through community dialogue. Nevertheless, the conflict interventions and reconciliations are not inclusive and participatory. Evidently, youths are considered as prominent actors in violence rather than being part of the reconciliation process.Footnote21 Therefore, profound community dialogue as a restorative justice model must involve all actors and concerned stakeholders.

Moreover, unconditional forgiveness is a key part of community dialogue to heal wounds and discard retaliation. Reconciliation and forgiveness are an important social process and personal prerogative (Souto, Citation2009). The Guji-Burji prolonged inter-ethnic conflict demands context transformation and attitudinal changes at the individual and societal levels. Community dialogue, reconciliation, and forgiveness are orientations of the African philosophy of humanhood, Ubuntu. Ubuntu, an African indigenous philosophy, represents the attitude of togetherness (Tutu, Citation2009). It is also the practice of restorative justice with healing, forgiveness, and reconciliation at the center of humanity and brotherhood. Considering this, the socially mandated and honored Gadaa system needs to be capacitated and scale up its indigenous conflict resolution roles along with the philosophy of Ubuntu.

Contextualizing conflict interventions along with the conflict genesis of what Galtung said, ‘ABC’ (attitude, behavior, contradiction), becomes critical in the peacebuilding process (Galtung, Citation1969). Social thinking of the conflict in its very nature is significant to recognize the norms, values, and beliefs of the conflict-affected community (Malan, Citation1997). Likewise, the context, memories, and relations in the very nature of the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict need to be contextualized with the genesis of the conflict. Because these are highly penetrated and manifested both at a personal level and in the local governance system, they shape the overall profile of the conflict. Regarding this, Murithi strongly argued that the prominent problem in Africa is the lack of acknowledgment to contextualize conflict intervention approaches along with the very nature and context of the conflicts (Murithi, Citation2008). Certainly, along with context transformation, rigorous efforts are needed to address the relational aspects of the overall profile of interactions within society. Then, memories of past discrepancies and hostile attitudes toward parties need to be transformed.

Lastly, an inclusive, integrated, and complementary approach under the legal pluralism framework becomes an indispensable effort in the process of transformative and sustainable peacebuilding. The theory of legal pluralism acknowledges the existence of more than one system or mechanism in the administration of the justice system and reconciliation in conflict-affected societies (Griffiths, Citation1986). It is incredible that sustainable peacebuilding needs both top-down and bottom-up approaches to balance the intertwined and indispensable issues of peace and justice. The protracted, and politicized Guji-Burji conflict needs the more integrated involvement of stakeholders to complement their dark sides with each other. As officials disclosed, there must be a strong and consistent institutional linkage between the existing stakeholders for the effective maneuver of justice, reconciliation, and peace institutionalization. Indeed, institutional linkages and integration frameworks provide possibilities to exercise their jurisdiction, fill capacity gaps for effective prosecution of criminals, and fight against impunity (Ladan, Citation2013; Zehr, Citation2008). To sum up, the conflict reactions and intervention approaches should be envisaged with an open community dialogue, considering the context and the very nature of the conflict.

Conclusions

Conflict is natural and inevitable in human interaction and relations. After the end of the Cold War, the nature of conflicts shifted from inter-state to intra-state based on ethnicity, religion, class, and nationalism between and among different groups. The world has experienced a lot of ethnic conflicts with massive deaths of civilians and huge devastating human security impacts. Among others, the most unforgettable violence in the history of mankind was the Rwanda genocide between Hutu and Tutsi and the crisis in Kosovo after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, which had reluctant UN intervention.

The Guji-Burji conflict is among the many prolonged and protracted ethnic-based conflicts and violence in Ethiopia. The historical profiles and interactions of the Guji and Burji have been explained on and off track, particularly with the introduction of ethnic federalism in 1991. The disagreements between Guji and Burji started during the imperial and military regimes. Overall, in different political regimes, they have experienced violent conflicts with destructive human security impacts. The Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict relies on root causes and trigger factors. The major structural cause of the conflict is the failure of ethnic-based federalism to address the overlapping and competing interests over boundaries and its politicization. Theoretically, in Ethiopia, ethnic-based federalism was introduced to accommodate diversity and promote unity. Nevertheless, the findings revealed that it has continued to be the root cause of ethnic-based conflicts in Ethiopia and the Guji-Burji conflict. Furthermore, the conflict has been activated and aggravated by several proximate factors, which arise from different sources and bodies. Some of these include the proliferation and illegal use of small arms; the rhetorical honor of killing; cattle rustling; the politicization and ethnicization of disputes; the partiality of conciliators; and the nature and experiences of conflict intervention approaches.

Nevertheless, interventions have been attempted in the Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict, it has remained on/off, and sustainable peace has become a challenging project so far. The findings of the research disclosed that the nature and experiences of the conflict intervention approaches in the Guji-Burji conflict are not transformative. The approaches are not inclusive, integrated, and complementary. In addition, the impartiality of conciliators and their political stances become the challenge in the reconciliation process and to induce the peace agreement. The Guji-Burji inter-ethnic conflict requires transformative conflict interventions that emphasis on the nature of the conflict and its genesis (the context of contradiction, attitude, and behavior). Therefore, conflict intervention approaches need to be more integrated and participatory, along with profound community dialogue and unconditional forgiveness, to build trust and future relationships.

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to thank the research participants for their consent and commitment to give me reliable data. Next, I am grateful for my friends who gave me constructive academic comments by reviewing and editing my paper. Finally, I am indebted to the editor and reviewers for their constructive academic comments and feedback to help me develop my paper, which is ready for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kefelegn Tesfaye Abate

Kefelegn Tesfaye Abate is a Lecture of Peace and Security Studies in the Department of Political Science and International Relations, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Woldia University, Woldia, Ethiopia.

Notes

1 FGD with Abba Gadaa and Guji Elders, August 2018.

2 Interview with Officials from Guji, July 2018.

3 Interview with Police officer, July 2018.

4 Interview with police officer, July 2018.

5 Interview with Burji Elders and officials, July 2018.

6 FGD with Guji Elders, July 2018.

7 FGD with Burji Elders, July 2018.

8 Interview with Police Officer, West Guji zone, July 2018.

9 Interview with Police Officer, July 2018.

10 FGD with Abba Gada and Burji Elders, Interview with religious leaders, August 2018.

11 Interview with Burji Elders, July 2018.

12 FGD with Abba Gadaa and Elders, August 2018.

13 FGD with Abba Gada, August 2018.

14 FGD with Abba Gadaa, August 2018.

15 FGD with Guji & Burji Elders; Interview with religious leaders, August 2018.

16 Interview with Elders and religious leaders, August 2018.

17 Interview with Police Officer and official from Burji, July 2018.

18 Interview with Elders, August 2018.

19 Interview with officials from both sides; FGDs with Burji Elders, July 2018.

20 Interview with Officials; FGDs with Elders, July 2018.

21 Interview with security personnel; FGDs with youths, July 2018.

References

- Abbink, J. (2011). Ethnic-based federalism and ethnicity in Ethiopia: Reassessing the experiment of after 20 years. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2011.642516

- Adane, H., & Engida, E. D. (2022). Post-conflict recovery and reconstruction of education in the Gedeo-West Guji zones of southern Ethiopia. International Review of Education, 68(3), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-022-09963-9

- Alem, H. (2003). Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia: Background, present conditions and future prospects. In International Conference on African Development Archives (Vol. 57). https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/57

- Aliff, S. M. (2014). Peace building in post–war societies. Journal of Social Review, 2(1), 31–44.

- Amare, K. (2012). Inter-ethnic conflict transformation in the post-1991 ethnic federalism: Experiences from Asossa Woreda in Benishangul Gumuz Regional state of Ethiopia.

- Asebe, R. (2007). Ethnicity and inter-ethnic relations: The Ethiopian experiment and the case of the Guji and Gedeo [Thesis]. University of Tromso.

- Asebe, R. (2012). Emerging ethnic identities and inter-ethnic conflict: The Guji-Burji conflict in southern Ethiopia. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 3(12), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12007

- Asebe, R., & Tadesse, J. J. (2018). “Peace is not a free gift”: Indigenous conceptions of peace among the Guji-Oromo in Southern Ethiopia. Northeast African Studies, 18(1–2), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.14321/nortafristud.18.1-2.0201

- Bantayehu, D. (2016). Inter-ethnic conflict in the southwestern Ethiopia: The case of Alle and Konso. https://www.bing.com/search?q=url%3D%7Bhttps%3A//api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID%3A1

- Barth, F. (1969). Introduction. In F. Barth (Ed.), Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture difference. Universitetsforlaget.

- Bassi, M., & Tache, B. (2011). The community conserved land scope of the Borana Oromo, Ethiopia opportunities and problems. Management of Environment Quality: An International Journal, 22(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777831111113365

- Bozeman, R. (1976). Conflict in Africa: Conan and realities. Princeton University Press.

- Buhari, K. N. (2013). Exploring indigenous approaches to conflict resolution: The case of Bawku conflict in Ghana. Journal of Sociological Research, 4, 86–104. https://doi.org/10.5296/jsr.v4i2.3707

- Coleman, T. P. (2006). Power and conflict. In M. Deutsch, E. C. Marcus, & P. T. Coleman (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution theory and practice (2nd ed.). Jossey Bass. https://inclassreadings.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/handbook-of-conflict-resolution.pdf

- Constitution of Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1995). Negarit Gazeta. Berhanina Selam Printing Press. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b5a84.html

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE publication, Inc.

- Crisis Group African Report (2009). Ethiopia: Ethnic federalism and its discontents. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/ethiopia-ethnic-federalism-and-its-discontents

- Daniel, M. (n.d.). Indigenous legal tradition as a supplement to African transitional justice initiatives.

- DeConing, C., & DeCarvalho, G. (2013). Peacebuilding handbook. The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, Umhlanga Rocks. https://www.accord.org.za/publication/accord-peacebuilding-handbook/

- Dereje, F. (2009). A national perspective on the conflict in Gambella. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, International Household Survey Network. http://portal.svt.ntnu.no/sites/ices16/Proceedings/Volume%202/Dereje%20Feyissa%20-%20A%20National%20Perspective%20on%20the%20Conflict%20in%20Gambella.pdf

- Desalegn, C. E., Seleshi, B. A., Regassa, E. N., Babel, M. S., & Gupta, A. (2005). Indigenous systems of conflict resolution in Oromia, Ethiopia. International workshop on ‘African Water Laws: Plural Legislative Frameworks for Rural’. https://publications.iwmi.org/pdf/H038765

- Dezeuw, J. (2001). Building peace in war-torne societies: From concept to strategy, research project on rehabilitation, sustainable peace, and development. Clingendael Institute. http://www.clingendael.nl/cru

- Dijk, P. (2009). Together in conflict transformation: Development cooperation, mission and diacony. In L. Kristina (Ed.). Conflict transformation: Three lenses in one frame. The Life & Peace Institute. Journal of Peace Research and Action, 14, 11–15. www.life-peace.org

- Evans, I., Lane, J., Pealer, J., & Tulner, M. (2013). A conceptual model of peace building and democracy building: Integrating the field. The Conflict Resolution and Change Management in Transitioning Democracy Practicum Group, School of International Service American University.

- Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600

- Galtung, J. (2007). Introduction: Peace by peaceful conflict transformation: The transcend approach. In J. Galtung & C. Weble (Eds.), Handbook of peace and conflict studies. Routledge.

- Gawerc, M. I. (2006). Peacebuilding: Theoretical and concrete perspectives. Peace & Change, 31(4), 435–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2006.00387.x

- Ghali, B.-B. (1992). An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, and peacekeeping. Report of the secretary general to the statement adopted by the summit meeting of the Security Council on 31 January 1992. UN Department of Public Information. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/145749

- Gololcha, B. (2015). Ethnic conflict and its management in pastoralist communities: The case of Guji and Borana zones of Oromia national regional state, 1970–2014 [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Addis Ababa University, Graduate School of Psychology.

- Griffiths-Fulton, L. (2002). Small arms and light weapons in the horn of Africa. The Ploughshares Monitor, 23(2).

- Griffiths, J. (1986). What is legal pluralism? The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 18(24), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.1986.10756387

- Gumi, B. (2016). Gondoro as an indigenous method of conflict resolution and justice administration. Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion, 23, 2422–8443. www.iiste.org

- Hilal, A. W. (2011). Understanding conflict resolution. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(2), 105–111.

- Hizkias, A. (1993). Peace and reconciliation as a paradigm: A philosophy of peace and its implication on conflict, governance and economic growth in Africa. Nairobi Peace Institute. worldcat.org

- Kothari, C. R. (2003). Research methodology, methods, and techniques. New Age International Publisher.

- Ladan, M. T. (2013). Towards complimentary in Africa conflict management mechanism.

- Last, D. M. (1999). From peacekeeping to peacebuilding: Theory, cases, experiments and solutions. Royal Military College Working Paper. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262423503

- Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Luba, T. (2012). The post 1991 inter-ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia: An investigation. Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution, 4(4), 62–69. http://www.academicjournals.org/JLCR

- Mafro, S. (2014). Indigenous Ghanaian conflict resolution and peace building mechanism, reality or illusion: A reflection on funeral among the people of Apaah and Yonso in the Ashanti Region. Journal of African Affairs, 3(8), 2346–7479.

- Malan, J. (1997). Conflict resolution wisdom from Africa. ACCORD.

- Miall, H. (2004). Conflict transformation: A multi-dimensional task. In Transforming ethnopolitical conflict: The Berghof handbook (pp. 67–89). Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Mkutu, K. (2000). Banditry, cattle rustling and the proliferation of small arms: The case of Baragoi Division of Samburu District, Arusha report. African Peace Forum.

- Murithi, T. (2006). African approach to building peace and social solidarity. African Journal of Conflict Resolution, 6(2), 9–33. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC16301

- Murithi, T. (2008). African indigenous and exogenous approaches to peace and conflict resolution. In D. J. Francis (Ed.), Peace and conflict in Africa. Zed Book.

- Mutisi, M. (2012). Introduction. In M. Mutisi & S. K. Greenidge (Eds.), Integration and modern conflict resolution: Experience from selected cases in Eastern and Horn of Africa, ACCORD. African Dialogue Monograph Series No. 2. Umhlanga Rocks. https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:00189531

- Notter, J. (1995). Trust and conflict transformation, occasional paper. Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy.

- Ogbazghi, P. B. (2022). Ethiopia and the running sores of ethnic federalism: The antithetical forces of statehood and nationhood. African Studies Quarterly, 21(2), 2152–2448. https://asq.africa.ufl.edu/files/V21i2a3.pdf

- Osagahe, E. E. (1997). The federal solution in comparative perspective. Politeia, 16(1), 4–19.

- Paton, Q. M., & Cochran, K. (2002). A guide to using qualitative research methodology. Médecins Sans Frontières. https://evaluation.msf.org/sites/evaluation/files/a_guideto_using_qualitative-research_methodology.pdf

- Ranies, S. S. (2013). Conflict management for managers; resolving workplace, client, and policy disputes. Jossy Bass Imprint. https://www.amazon.com/Conflict-Management-Managers-Resolving-Jossey-bass/dp/0470931116

- Ruth, S. (2017). Emerging conflicts and quest for sustainable peace building in West Guji Zone of Southern Ethiopia [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Souto, V. S. (2009). Reconciliation and transformational justice: How to deal with the past and build the future [Master thesis]. Peace Operations Training Institute. https://cdn.peaceopstraining.org/theses/souto.pdf

- Stewart, G. (2018). What does ‘indigenous’ mean, for me. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(8), 740–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1302050

- Taddesse, B. (2009). Changing alliances of the Guji-Oromo and their neighbors: State policies and local factors. Berghaham Books, 1, 191–199.

- Takele, B. B. (2021). Ethnic conflict in Ethiopia: Federalism as a cause and solution. Quito, 6(30), 2477–9083.

- Takele, B. B. (2022). Is federalism the source of ethnic identity-based conflict in Ethiopia? Insight on Africa, 14(1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878211057125

- Tutu, D. (2009). No future without forgiveness. Easton Press.

- Van der Beken, C. (2013). Federalism in a context of extreme ethnic pluralism: The case of Ethiopia’s southern nations, nationalities and peoples region. Verfassung in Recht und Übersee, 46(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.5771/0506-7286-2013-1-3

- Vestergaard, B., Helvard, E., & Sørensen, A. R. (2011). Conflict resolution – Working with conflicts. The Danish Center for Conflict Resolution, 4(9), 978–987.

- Zartman, I. W. (Ed.). (2000). Traditional curse for modern conflicts: African conflict medicine. Lynne Rinner Publisher.

- Zehr, H. (2008). Doing justice, healing trauma; The role of restorative justice in peace building. South Africa Journal of Peace Building, 1(1), 1–16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238798684