Abstract

Unsheltered homelessness is associated with a myriad of barriers including unmet medical, mental health, physical, and social needs. This study evaluated a Street Medicine approach to examine and reduce the complex barriers to care by providing coordinated mobile services. Participants were urban adults with mental health, substance use, or co-occurring issues who were experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Services provided were integrated, person-centered, and trauma-informed based on participants’ needs. The range of offered services included psychiatric and medical care, case management, housing support, mental health, and substance abuse treatment, as well as a variety of supportive services. Structured baseline interviews (N = 295) and 6-month follow-ups (N = 118) were conducted, and a range of outcomes were examined including quality of life, behavioral and physical health indicators, substance use, and recovery domains. Using a bivariate analysis approach, promising results were seen at follow-up including improved quality of life, reduced PTSD symptom severity, reduced substance use, and reduced risk behavior. Several significant interactions were also discovered including the impact of housing status on quality of life and recovery. Race and gender differences were examined and improvement across outcomes differed by race/ethnicity. The results suggest that mobile services targeting unsheltered persons are viable options towards improved health, health equity, and quality of life. Further research should continue to evaluate interventions and ways to reduce stigma, discrimination, and barriers to treatment for unsheltered persons experiencing homelessness.

Introduction

Persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) represent one of the most disadvantaged and underserved populations across all social categories. It is well-documented that PEH is affected by disproportionately high rates of mental health issues, substance use disorders, co-occurring disorders, comorbidities, and chronic health conditions compared to the general population, all of which are associated with poor health outcomes and substantial risk of premature mortality (Gilmer & Buccieri, Citation2020; Lebrun-Harris et al., Citation2012; Somers et al., Citation2015).

The nature of homelessness itself also poses significant health challenges. Multiple contextual risk factors (i.e. unstable living conditions, disease exposure, poor hygiene and self-care, inadequate nutrition, increased risk of violence, and severe accidental injury) combined with common vulnerabilities, such as trauma history, adverse childhood experiences, and cognitive impairment common in PEH are associated with poor health outcomes (Fazel et al., Citation2014; Paudyal et al., Citation2019). All of these factors have multiplicative effects that further compromise the overall health, quality of life, and well-being of PEH.

Among the most vulnerable subpopulations of PEH are those experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Unsheltered homelessness is defined as living outdoors in any public or private place (e.g. on the streets, under bridges, homeless encampments, in vehicles, abandoned buildings) not intended for human habitation (Unsheltered Homelessness and Homeless Encampments in 2019, Citation2021). Unsheltered PEH, also referred to as ‘street homeless’ or ‘rough sleepers’ are among the hardest to identify and engage in services yet have the most critical needs compared to other PEH subgroups (Llerena et al., Citation2018; Stergiopoulos et al., Citation2010). Unsheltered PEH has more global functioning limitations and social impairments (Christensen, Citation2009), is nearly twice as likely to suffer from mental illness and substance use disorders (Lo et al., Citation2021), and has greater unmet healthcare needs compared to sheltered PEH (Petrovich & Cronley, Citation2015).

Barriers to care, particularly for unsheltered PEH, are complex in this population for a myriad of reasons. Unmet healthcare needs are as much as 10 times higher in the homeless population compared to the general population (Baggett et al., Citation2010) which is in part due to low health literacy, insufficient service availability, perceived apathy, and services offered in modalities incompatible with the needs of PEH (Duhoux et al., Citation2017). Unfulfilled healthcare needs of unsheltered PEH have also been associated with discrimination based on social status, perceived negative attitudes, stereotyping, and adverse judgment by healthcare providers, which inhibit positive life changes (Alexander et al., Citation2021; Kryda & Compton, Citation2009). Moreover, practical issues associated with the transient nature of homelessness and competing priorities of living in survival mode interfere with continuity of care, exacerbating the likelihood of poor health outcomes (Frankish et al., Citation2005; Ungpakorn & Rae, Citation2019).

Street Medicine (SM) is an approach to care that works to remove barriers to healthcare for unsheltered PEH. SM is a reality-based approach to healthcare delivery that is designed to provide coordinated medical, mental health, and social services directly on the streets, under bridges, alleyways, and within the urban encampments where PEH live, with the overarching goal of delivering comprehensive, relationship-centered care (What is Street Medicine?, Citation2022; Withers, Citation2011). A previous SM program showed success in improving follow-up care and addressing social needs by bringing care to patients in their own environment (Feldman et al., Citation2021). By bringing services to meet people where they are, the SM approach offers the opportunity to build greater trust and engagement among PEH than traditional models (Feldman et al., Citation2021; Lynch et al., Citation2022). Qualitative interviews with SM providers suggest trust and relationships built with patients are central to their approach to care (Frankeberger et al., Citation2022).

My Health My Resources (MHMR) of Tarrant County is the second-largest community center in Texas and the local mental health authority in Tarrant County that works to provide services to individuals of all ages with mental health and integrated healthcare needs. MHMR was awarded grant funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to implement an SM program within our Integrated Outreach Services (IOS) division to better serve and enhance the quality of services provided to unsheltered PEH. The program was established in May 2020 in Tarrant County, Texas, a large urban area (2,110,640 total population) (Quickfacts Tarrant County, Texas, Citation2023), and ∼2% (3489) were identified as PEH (2018 State of The Homeless Report, Citation2018). Before receiving this grant funding, the only SM services available in Tarrant County were provided by the local county hospital’s medical SM program addressing primary healthcare.

The IOS SM program is a mobile unit that provides individualized, integrated, trauma-informed services to unsheltered PEH. Services are delivered in homeless encampments, riverbanks, and under bridges throughout Tarrant County utilizing a Housing First and person-centered framework that facilitates patient-provider trust and self-efficacy. Every position on the Street Medicine team is integral in meeting the individual, significant, and diverse needs of the clients’ served. The behavioral health outreach and treatment services are provided by the 14-member SM team, which includes a Program Manager, Physician Assistant (PA), Registered Nurse, Medical Assistant, Licensed Therapist, Substance Use Counselor, Wellness Navigators/Case Managers, Recovery Support Peer Specialists, and Outreach Specialists. Each member of the Street Medicine team spends ∼80–90% of each day in the field, with the goal of providing bi-monthly face-to-face visits at a minimum with each client enrolled in the program.

The team offers a robust service array including screening/assessment services, crisis intervention, medication education and management, mental health counseling, substance use counseling, peer support, transportation, as well as linkage to clothing, dental, critical documents, food stamps, housing, medical/primary health, supported employment, veteran, and vision services. The MHMR SM program developed multiple community partnerships to accommodate patients’ needs, as well as partnered with the local county hospital’s SM program to provide medical care.

The purpose of this program evaluation was to examine outcomes for MHMR’s inaugural SM program. In a 2-year longitudinal study, a one-group pretest-posttest design was used to measure changes across various healthcare outcomes for SM program participants. There were three aims for this evaluation: (1) examine changes over time in the quality of life, mental and physical health, posttraumatic stress, substance use, risk behavior, recovery domains, and housing status outcomes from the baseline evaluation conducted at program enrollment to follow-up evaluation after six-months of program intervention; (2) determine if housing status (receiving housing placement vs. remaining unsheltered) influenced outcomes; and (3) examine any differences in outcomes based on race and gender groups.

Methods

Recruitment and procedures

Individuals eligible for participation in the SM program were unsheltered PEH aged 16 years and older residing in Tarrant County, Texas. Individuals could be referred to the program through two pathways. First, SM staff outreached individuals directly within homeless encampments and on the streets. Program referrals were also made via internal agency and community partners, at which time SM staff attempted to locate referred individuals in the community. When potential participants were identified, SM staff explained the program and assessed individuals for eligibility, as determined by current unsheltered homelessness status, had mental health, substance use, or co-occurring (i.e. dually diagnosed) mental health and substance use issues, and not currently enrolled with the MHMR Tarrant County integrated homeless clinic to avoid duplication of any behavioral health or medical services provided by MHMR Tarrant. Individuals could be unsheltered for any length of time to be eligible for SM services. Those who met eligibility criteria and who consented to services were enrolled in the program after two outreach encounters with program staff. Families and couples were enrolled as individual program participants.

After enrollment, participants received a housing assessment and additional services for a minimum of six months. All service provision occurred within the homeless encampments or on the streets, with the goal of minimizing structural barriers by taking services directly to participants in their own environment. Services provided were person-centered and based on participants’ needs, such as outreach services, addressing basic needs (i.e. food, blankets) housing assistance, obtaining vital records, psychiatric/behavioral healthcare, case management/care coordination, benefits and employment assistance, substance use interventions, harm reduction supplies, transportation to and from appointments, and various support services. However, individuals could be concurrently receiving services from community homeless service providers if a needed service was not offered by the SM program.

Data collection and participants

Within seven days of enrollment, participants met with a research associate who obtained written informed consent and conducted a baseline evaluation. A hygiene kit was given to participants as a thank you after completing the baseline interview. Participants were located again after participating in the program for six months to complete a follow-up evaluation and received a $30 gift card after completing the follow-up. The evaluations consisted of structured interviews 45–90 min in length. Evaluations were conducted on-site within the encampments or other locations desired by participants. The study was approved by the MHMR Tarrant County Institutional Review Board (Approval # FWA00006352, IRB registration # 00003977).

Data collection occurred from 1 August 2020 to 31 July 2022. During this timeframe, 295 baseline evaluations and 118 six-month follow-up evaluations were conducted. Of the 295 baseline evaluations conducted, only 231 were eligible for follow-ups. Due to funding timeline restrictions, 30 participants with baselines had not participated in the SM program for six months by the end of the grant period, 14 were incarcerated and were inaccessible at follow-up, 16 moved out of the service area, and four had passed away before follow-up (n = 64). Of the 231 eligible for follow-ups, 113 could not be located at the time of follow-up and thus were lost to evaluation, resulting in a 51% follow-up rate.

Although research staff accompanied SM treatment staff in the field daily in making multiple attempts to relocate participants for follow-ups, several barriers impacted successful relocation, including COVID-19 quarantine protocols, frequent mandated encampment relocation due to public camping restrictions, and the inability to locate clients within the follow-up timeline due to communication barriers (i.e. no phone, permanent address). As one of the primary research goals was to examine changes in outcomes from baseline to six-month follow-up, only 118 participants with both baseline and follow-up data were included in the analysis.

Measures

The structured interview was comprised of multiple instruments used to assess a range of life domains and health indicators, including sociodemographics, experiences living as homeless, quality of life, mental and physical health, substance use, risk behavior, posttraumatic stress, and aspects of recovery. All interview questions were quantitatively coded for analysis. Internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha for all scaled outcome variables.

The sociodemographic variables assessed included gender, race, age group, education, length of time spent homeless, income, criminal history, chronic health conditions, violence/trauma experienced, personal safety, circumstances attributing to homelessness, and food security. Violence/trauma experienced was a dichotomous variable (yes/no) in which participants were asked to report if they had ever experienced violence or trauma in any setting, including community/school violence, physical, psychological, or sexual maltreatment/assault, natural disaster, terrorism, neglect, or traumatic grief. Personal safety, defined as how participants felt about their personal safety during the daytime, was rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 = terrible to 7 = delighted. Circumstances attributing to homelessness was a multi-select variable in which participants reported the circumstances or events that led to their experiencing homelessness from a list of seven options. As an indicator of food security, participants rated on a four-point scale, ranging from 1 = never to 4 = usually, how often they were able to get enough food to eat.

Of note, preliminary examinations of the first 10 baseline interviews revealed participants had difficulty responding to questions regarding criminal history. As originally designed in the structured interview, participants were asked to report how many times they had been arrested in the past six months and within the past 30 days. Due to the nature of unsheltered homelessness and frequent encounters with law enforcement for criminal trespass or public camping, participants were unable to accurately report the number of times they had been arrested within the past six months. For this reason, the interview questions regarding criminal history were modified to ask participants if they had ever been arrested (yes/no). Data was examined again after this modification, and it was determined this change was sufficient to capture more accurate responses regarding criminal history.

Quality of life

The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) instrument was used to collect data on quality of life. Participants were asked to rate their overall quality of life on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = very poor to 5 = very good, and rate their satisfaction on four life domains (performing daily living activities, health, self-satisfaction, and personal relationships) on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied. All items were summed to create an overall quality of life score ranging from 5 to 20, with higher scores indicating higher quality of life. Cronbach’s α for this subscale was .77.

Mental and physical health

Daily functioning was assessed as a measure of mental health and collected using the GPRA. This subscale is comprised of six items that measure how well participants were able to deal with their everyday lives in the past 30 days. Items were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Example items include ‘I deal effectively with my daily problems’ and ‘I am able to control my life’. Items were averaged to compute an overall daily functioning score, with higher scores indicating higher functioning. Cronbach’s α for this subscale was .72.

Emotional distress as measured on the GPRA is comprised of six items assessing how often participants experienced six feelings/emotions (i.e. nervous, hopeless, depressed, restless, worthless, everything being an effort) in the past 30 days, on a five-point scale ranging from 0 = none of the time to 4 = all of the time. Changes in scores for each emotion were examined. Items were also summed to compute an overall emotional distress score ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater emotional distress. Cronbach’s α for this subscale was .85.

The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a 36-item instrument designed to measure perceived health status across eight domains: (1) physical activity limitations due to health problems (2) social activity limitations due to physical or emotional problems, (3) daily role activity limitations due to physical health, (4) bodily pain, (5) general mental health, including well-being and psychological distress, (6) daily role activity limitations due to emotional problems, (7) vitality, including fatigue and energy levels, and (8) general health perceptions, along with two summary measures for overall physical health and mental health (Ware & Sherbourne, Citation1992). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status. Cronbach’s α was computed for all scales, four of which had alpha levels below the acceptable range (i.e. general mental health, vitality, social functioning, general health perceptions) and thus were dropped from the analysis. Cronbach’s α for the remaining scales ranged from .65 to .98.

Posttraumatic stress

Posttraumatic stress was assessed using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Weathers et al., Citation2014). The PCL-5 is a 20-item instrument that measures 20 DSM-5 symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Participants were asked to report how frequently they were bothered by each symptom within the past month. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely. Example items include: ‘feeling jumpy or easily startled’ and ‘having difficulty concentrating’ Items were summed to compute a total score ranging from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater PTSD symptom severity. A cut-off score of 33 was also established, consistent with previous research (Weathers et al., Citation2014), to indicate scores above this point may warrant clinical attention. Cronbach’s α was .98.

Substance use

Substance use data derived from the GPRA. Participants were asked to report how often they used various substances within the past 30 days. Substances assessed included: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, and street opioids. Possible response options for each category were: never = 1, once or twice = 2, weekly = 3, and daily/almost daily = 4. The total number of substances used was included as an indicator of polysubstance use.

Risk behavior

Risk behavior was measured using a modified version of the TCU Comprehensive Intake for Community Settings tool (TCU Institute of Behavioral Research, Citation2022). Risk behavior was operationally defined as intravenous (IV) substance use, using unsterilized syringes, and sharing injection materials. Participants were asked if they engaged in these activities within the past six months. Responses were coded into dichotomous variables (yes/no).

Recovery domains

The Recovery Assessment Scale–Domains and Stages, Version 3 (RAS-DS) is a 38-item instrument that accesses four domains of recovery in people living with mental illness: doing things I value, looking forward, mastering my illness, and connecting and belonging (Hancock et al., Citation2015). Participants were asked to report on how they felt about themselves on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = untrue to 4 = completely true. Example items include: ‘I have goals in life that I want to reach’, and ‘I know when to ask for help’. A total recovery score was computed by summing all items, ranging from 38 to 152. The four domain scores were also computed. Higher scores indicate higher stages of recovery. Cronbach’s α ranged from .82 to .95.

Housing status

A dichotomous variable was created to identify participants who did and did not receive housing placement during their program participation. Participants who received placement were coded as 1 = housed, and 0 = unsheltered for those who had not exited out of unsheltered homelessness during their program participation.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for all sociodemographic variables. McNemar’s Tests were used to assess differences over time for dichotomous variables. Initially, ordinal variables were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and paired-samples t-tests, and there were no differences in outcomes between the tests run. Therefore, to concisely display findings ordinal data were treated as continuous, and paired-samples t-tests were used to analyze the data for mean changes in outcomes over time. To address elements of race, gender, and housing status, a series of repeated measures mixed Analysis of Variances (ANOVAs) were used to examine changes in outcome variables among these groups. Statistical significance was set to p ≤ .05. All data were analyzed using SPSS, version 25.

Results

Process evaluation

The process evaluation describes the frequency of face-to-face service encounters program participants had with SM staff, as well as what types of services participants received between baseline and the six-month follow-up. As process data was collected and summarized for each participant during the follow-up period, process data for participants who did not complete the six-month follow-up is unavailable.

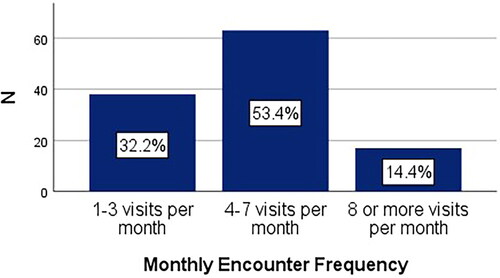

Participants had approximately five face-to-face visits with SM staff on average per month (M = 4.88, SD = 2.71), and the number of visits ranged from 1 to 20 per month. As shown in , ∼32% of participants had <4 visits per month with SM staff, whereas about 68% had more than 4 visits per month.

Participants received a wide service array that was individualized, person-centered, and based on participants’ stated needs. The types of services program participants received are provided in . All participants received screening and assessments, and the majority received primary services including treatment planning (96.6%), case management (95.8%), mental health services (94.1%), medical care (77.1%), and psychiatric care (51.7%). A large majority of clients also received supportive services, which included clothing and other basic essentials, such as jackets, blankets, gloves, socks, and hygiene products (90.7%), transportation to and from appointments (87.3%), and assistance with obtaining food stamps (52.5%). Additionally, nearly 70% received a housing match (i.e. when an individual is matched with an available housing opportunity), and about 45% moved from unsheltered homelessness to permanent supportive housing.

Table 1. Services provided to SM program participants.

The essential primary behavioral health and supportive services were provided by the 14-member SM team, which included a Provider, Registered Nurse, Medical Assistant, Licensed Therapist, Substance Use Counselor, Wellness Navigators/Case Managers, Recovery Support Peer Specialists, and Outreach Specialists. Medical services were provided by our community partner, the local county hospital’s SM program.

Research evaluation

Sociodemographics and sample characteristics

The demographics for participants are presented in . Participants were predominantly male (69%) and between 45 and 54 years of age (39%). The sample majority identified as White (54%), whereas 46% identified as a Person of Color. Most participants (93%) identified as heterosexual. More than half (61%) had reported completing at least a high school education or equivalent. Approximately 70% indicated they had at least one chronic health condition, with 16% reporting two conditions and 23% reporting three or more conditions. Most participants also reported prior involvement with the criminal justice system (91%) at some point during adulthood and experiencing violence or trauma during their lifetime (78%).

Table 2. Baseline sociodemographics (N = 118).

To capture characteristics related to homelessness, participants were asked to report on the total length of time spent living homeless, circumstances leading to homelessness, income sources, food security, and feelings of personal safety. Total time spent living as homeless ranged from <1 to 30 years, with half of the sample (51%) reporting at least two years of homelessness (M = 4.89, SD = 5.01). The most frequently reported circumstance leading to homelessness was getting separated or divorced, (38%), followed by frequent substance intoxication (29%), a drop in income (28%), increased expenses, and losing financial/living support (25%), having serious physical or mental health problems (24%), being institutionalized (13%), and other (3%). Nearly half of the sample (47%) reported only one circumstance leading to homelessness, whereas 31% and 14% reported two and three circumstances, respectively. Since becoming homeless, 62% reported concerns about or was fearful for their personal safety, and 37% reported rarely or never getting enough food to eat.

For income sources, panhandling was reported most frequently (30%), followed by public assistance (e.g. food stamps, disability) (29%), receiving money from relatives/friends (17%), and having a job or working odd jobs (14%). Approximately 28% reported income by other means, such as recycling, selling plasma, and selling items found on the streets. Two or more income sources were reported by 36% of the sample. A small number of participants (11%) reported having no income.

Changes in outcomes over time

Research aim one was to examine changes in outcome variables over time from baseline to six-month follow-up to evaluate the impact of the SM program intervention on program participants. Descriptive statistics and t-test results for continuous variables and percentages for dichotomous variables for this section are displayed in .

Table 3. Baseline to follow-up descriptive statistics and t-test results for outcome variables.

Quality of life

Significant improvements were found over time for overall quality of life. Average quality of life scores were higher at follow-up, with a mean 1.17-point increase compared to baseline scores (p = .013). Within this domain, 42% reported greater health satisfaction (p = .032) and 45% reported greater self-satisfaction (p = .001) at follow-up.

Mental and physical health indicators

Daily functioning remained relatively unchanged from baseline to follow-up. Slight declines at follow-up in overall emotional distress were found, although declines were nonsignificant. In examining changes for each emotion within the emotional distress domain, 40% reported significant declines over time in feelings of hopelessness (p = .018), and 45% reported declines in feelings of restlessness (p = .028). For the SF-36 health domain scores, perceived overall mental health significantly improved from baseline to follow-up, with a mean increase of 3.5 points (p = .030). All other changes in domain scores were nonsignificant.

Posttraumatic stress

The majority of participants completed the PCL-5 at both time points (n = 109); some participants declined this measure because they did not wish to discuss their traumatic experiences. All participants were requested to complete this instrument, even if they did not endorse experiencing a violent or traumatic event in their lifetime, as trauma is often a consequence of homelessness. PTSD symptom severity scores declined significantly over time, with an average 9.56-point decline from baseline to follow-up (p < .001). Over half of the participants had severity scores that warranted clinical attention (above the 33-cutoff point) at baseline (67%), which declined to 49% at follow-up (p = .002).

Substance use

Average alcohol use significantly declined over time (p < .001) and 27% fewer individuals reported not drinking alcohol within the past 30 days at follow-up (p < .001). Significant declines were also found for polysubstance use (p < .001), in which 45.6% of participants reported a reduction in the total number of substances used at follow-up. Participants reporting using any illegal substance use declined over time from 67% to 57% (p = .012). Declining trends were found for all other substances, all of which were nonsignificant.

Risk behavior

For those reporting using any illegal substance at baseline (n = 82), significant declines were found in the number of participants who used substances intravenously, from 49% to 37% (p = .035), and for those who used intravenously (n = 40), significantly fewer participants reported using unsterilized syringes (p = .002) and sharing injection materials (p = .012) at follow-up.

Recovery domains

Positive outcomes were found in most recovery domains over time. Significantly higher overall mean recovery scores were reported at follow-up (p = .037) with a mean 6-point increase. Improvements were also found at follow-up for doing things I value (p = .011) and connecting and belonging (p = .042), with mean increases of 5.5 and 5.7, respectively. Changes in looking forward and mastering my illness domains were nonsignificant.

Group interactions

The second and third research aims were to examine interactions based on housing status (receiving housing placement vs. remaining unsheltered), race, and gender, and further determine whether outcomes were related to group differences. Descriptive statistics (M, SD) by time and group are displayed in . Statistical significance testing between and within groups at baseline and follow-up is examined in the housing, race, and gender between groups and interaction sections.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics by time and group.

Interactions: housing status

This section examines interactions based on housing status. A series of two-way mixed ANOVAs were used to examine changes in outcomes for individuals who were housed (n = 53) during their program intervention compared to those who remained unsheltered (n = 65). ANOVA results for this section are displayed in .

Table 5. Two-way mixed ANOVA results for housing status on key outcomes (N = 118).

Housing status main effects

Significant main effects were found for quality of life (p = .005), overall mental health (p = .026), RAS-DS total recovery (p = .028), doings things I value (p = .013), and connecting and belonging (p = .035), all of which had higher scores at follow-up compared to baseline (). Significant main effects were also found for PTSD symptom severity (p < .001), with lower scores at follow-up. The main effects of time on emotional distress fell short of reaching significance (p = .053).

Housing status interactions

Housing status had an impact on quality of life over time. While there was no difference in overall quality of life between groups, a significant interaction between housing status and time on quality of life was found [F(1,116) = 7.465, p = .007, partial ꞃ2 = .060]. Tests for simple effects revealed significantly lower quality of life scores at baseline for the housed group (p = .003), which also significantly improved over time for the housed group (p = .001), but not the unsheltered group.

No differences in daily functioning between housed and unsheltered groups were found, but a significant interaction between housing status and time on daily functioning was present [F(1,116) = 5.207, p = .024, partial ꞃ2 = .043]. Simple effects showed significantly improved functioning in the housed group over time (p = .045), but not in the unsheltered group. A significant interaction between housing status and time on mastering my illness was also found [F(1,116) = 7.298, p = .048, partial ꞃ2 = .033], although tests for simple effects were nonsignificant.

Housing status between group differences

Between groups differences were found for overall physical health, which was significantly lower overall in the housed group compared to the unsheltered group (p = .008). No other between-group differences were found for housing status.

Interactions: race and gender

This section examines interactions based on race and gender. Given the small number of non-White racial groups compared to the White group, Race was recoded into two categories, People of Color (POC) (n = 54) and White (n = 64) groups. There were over twice as many males (n = 81) than females (n = 37) in the sample. Given the small number of POC females (n = 12), race by gender interactions could not reliably be computed. Therefore, a series of two-way mixed ANOVAs were used to examine outcomes by race and gender interactions separately. ANOVA results for this section are displayed in .

Table 6. Two-way mixed ANOVA results for race and gender on key outcomes (N = 118).

Race and gender main effects

Several main effects for time were found in the sample. Significant main effects were found for quality of life, overall mental health, PTSD symptom severity, RAS-DS total recovery, and doing things I value in the race and gender group analyses (ps < .05), with improvements in all outcomes found at follow-up. Significant main effects for time on connecting and belonging with race as the between-subjects factor were present (p = .034), but not with gender as the between-subjects factor. Emotional distress fell short of significance in both race and gender analyses.

Race and gender interactions

A significant interaction between time and race on the perception of overall physical health was present [F(1,116) = 5.760, p = .018, partial ꞃ2 = .047], which simple effects showed physical health perception to significantly decline over time for White (p = .016) but not for POC participants. An interaction between time and race was also present for PTSD symptom severity [F(1,107) = 6.317, p = .013, partial ꞃ2 = .056], in which POC had significantly lower scores than Whites at follow-up (p = .001), and POC had declines in scores from baseline to follow-up (p < .001), whereas nonsignificant declines in PTSD were found for White participants.

Race and gender between-group differences

Between-group differences were found for daily functioning, in which POC had significantly higher daily functioning scores overall compared to Whites (p = .009). POC also had higher overall mental health perception scores compared to Whites (p = .004). PTSD symptom severity scores were lower overall for POC compared to White participants (p = .004). In contrast, overall emotional distress was higher for Whites than POC, although differences fell short of significance (p = .053). Females also had greater PTSD symptom severity (p < .001) and emotional distress (p = .008) overall compared to males, as well as lower perception of physical health overall compared to males (p = .046).

Baseline characteristics and attrition

Given nearly half of the participants who completed baselines were lost to follow-up (49%), we examined whether baseline characteristics were related to attrition. It is possible that participants who were able to be located had different characteristics or more severe needs and thus were more easily reached for follow-up compared to those unable to be located. To examine this possibility, baseline characteristics on key outcome variables were compared between participants with six-month follow-ups and those who were lost to follow-up using independent-samples t-tests (). In contrast to expectations, results showed participants who had six-month follow-ups had higher and more positive mean scores across outcomes (except for physical health and PTSD) compared to those lost to follow-up, although most differences were nonsignificant. Daily functioning was statistically significantly higher in the retained group compared to the lost to follow-up group (p = 0.35).

Table 7. Baseline comparisons between retained and lost to follow-up participants.

Discussion

Programs using a street outreach model of care are designed to ‘meet people where they are’ (Olivet et al., Citation2010) and use principles of engagement to develop rapport and trust within the PEH community, demonstrate genuine concern for wellbeing, and meet social connection needs, all of which increases treatment participation (Christensen, Citation2009; Daiski, Citation2005). Multidisciplinary programs are also associated with better outcomes compared to referral-based programs due to the removal of a variety of social barriers and being equipped to address a variety of needs (Whitman et al., Citation2022). Utilizing the SM model combined with a multidisciplinary approach, the IOS SM program increased the accessibility to behavioral and primary healthcare for PEH in Tarrant County. Meeting clients ‘where they are’ and outside of traditional clinics propagated trust, compassion, flexibility, radical humanity, and client-provider respect. The very nature of providing care to unsheltered individuals in camps, parks, and riverbanks, ultimately reduced the barriers to care, in addition to reducing the stigma and marginalization that many unsheltered persons experience daily.

Health outcomes over time

Results from this study add to the growing body of research that shows SM is an important part of psychosocial rehab and has promising results for PEH. This evaluation indicated that six months after enrollment, SM participants showed significant improvements across many health indicators. These results are consistent with previous research that shows integrated healthcare delivered using an SM modality is effective in improving various health outcomes for PEH (Olivet et al., Citation2010).

Programs using various street outreach models have found improvements in mental health, psychiatric symptoms, and PTSD symptoms (Goering et al., Citation1997; McManus & Thompson, Citation2008; Tommasello et al., Citation2006). In our sample, improvements were found in overall mental health, PTSD symptom severity, and the number of participants who had PTSD symptoms warranting clinical attention. Although declines in overall emotional distress were narrowly nonsignificant, declines in feelings of hopelessness and restlessness were identified. It is well documented that living as homeless is exceptionally stressful as PEH have continuous competing obstacles in meeting basic needs, and face frustrations of navigating the system, while simultaneously coping with the stigma and discrimination associated with being labeled as homeless (Kidd, Citation2006; Mejia-Lancheros et al., Citation2020; Skosireva et al., Citation2014; Wusinich et al., Citation2019). While obtaining housing can reduce these stressors, the transition out of homelessness can be equally stressful as newly housed individuals are removed from their encampment supports and must learn new independent living skills. These challenges may in part explain our findings. Nonetheless, our findings suggest suggests the SM approach can positively influence some mental health outcomes for PEH.

Within the context of street outreach, few studies have investigated quality of life (Baxter et al., Citation2019). Our results revealed improvements in quality of life, health-satisfaction, and self-satisfaction at follow-up. Street outreach has been linked to increased motivation and encouragement to seek services by removing stigma through building positive, nonjudgmental relationships (Lee & Donaldson, Citation2018). As social support is an important predictor of self-efficacy and life quality for stigmatized groups (Cohrdes & Mauz, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2022), this core relational component may have contributed to positive changes in quality of life for SM participants.

A majority of research on PEH and substance use has only addressed prevalence. Substance use is associated with the outset and perpetuation of homelessness (Fazel et al., Citation2014). Co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders are common, as is a high risk of overdose due to using substances as a mechanism for coping with homelessness and mental health issues (Austin et al., Citation2021; Doran et al., Citation2020). However, examinations of various street outreach models have found increases in substance use treatment (Fisk et al., Citation2006) and declines in use (Rosenblum et al., Citation2002). Dual Housing First-care management programs have also been associated with reduced alcohol use for formerly homeless individuals (Collins et al., Citation2012; Henwood et al., Citation2016). Our findings similarly showed significant declines at follow-up in the number of participants using alcohol and illegal substances, as well as the severity of polysubstance use.

Related to substance use were declines found in substance use risk behavior. Fewer participants used substances intravenously, used unsterilized syringes and shared injection materials at follow-up. Harm reduction is a recovery-oriented approach to care that prioritizes reducing harm caused by substance use over abstinence (Thomas, Citation2005). The SM program’s harm reduction strategy included providing participants with clean use kits. Although harm reduction principles are essential to promoting health and ending homelessness (Pauly et al., Citation2013) harm reduction outcomes within street outreach and Housing First paradigms have been minimally investigated (Kerman et al., Citation2021). Our findings contribute to this sparse body of literature and demonstrate that harm reduction strategies can be implemented to reduce certain substance use risk behaviors for PEH.

Recovery is a complex process affecting multiple life domains and reflects the positive changes experienced as individuals learn to overcome and manage physical and mental health issues, trauma, and substance abuse, all of which are problematic for PEH (Manning & Greenwood, Citation2019). Our results showed significant positive changes in overall recovery, doing things that were personally valued, and connecting/belonging at follow-up. Recovery has been linked to trauma-informed, person-centered care and having treatment options, which enhances the sense of personal control (Shank et al., Citation2015). The SM program was based on these fundamental recovery principles, and our findings support the SM model in positively influencing recovery.

Health outcomes across groups

Results indicated changes in housing status can influence some health outcomes. Participants who were housed reported improvements in quality of life at follow-up compared to those unsheltered. The housed group also had poorer overall physical health and reported daily functioning improvements whereas the unsheltered group did not. Existing research has shown unsheltered PEH have greater vulnerabilities and illness, thus increasing the likelihood of housing placement (Weare, Citation2021), and care-integrated housing placement positively impacts quality of life (Schick et al., Citation2019). It is plausible that those with greater needs stand to gain the most benefit from housing placement, which may explain changes in quality of life and daily functioning based on housing status.

Gender differences also emerged in the data. Females had overall poorer physical health, as well as higher emotional distress and PTSD symptom severity compared to males. PEH females are reportedly more vulnerable to victimization, have more extensive trauma histories, and face more stigma and discrimination than males (Savage, Citation2016). Further investigation is needed to understand the unique needs of women experiencing homelessness and how to expand assistance in the context of SM.

The most prominent group differences found were related to race. Results suggest different baseline characteristics and responses to the program dependent on race, with POC showing more positive scores at baseline and greater improvement across outcomes. Between-group comparisons revealed significantly higher overall daily functioning and mental health scores for POC compared to White participants. PTSD symptom severity was also lower overall and declined over time for POC but remained relatively stable for Whites. In contrast, overall physical health declined over time for Whites, but not POC, and although emotional distress fell short of significance, distress was higher in the White group compared to the POC group. While these results contradict much of the literature showing POC have poorer overall health and pervasive health disparities compared to Whites (Assari, Citation2018) our findings may reflect underlying influences of stigma, discrimination, and structural racism.

Research has identified a racial paradox regarding mental health in which POC report comparable or better overall mental health than Whites, despite experiencing more chronic stressors relative to Whites (Keyes, Citation2009; Louie & Wheaton, Citation2019; Pamplin & Bates, Citation2021). Multiple mechanisms could be responsible for this, including POCs reluctance to disclose psychological problems, significant mental illness stigma concerns (Ward et al., Citation2013), service avoidance due to stigma and mistrust (Weisz & Quinn, Citation2018), increased self-esteem, social support, and religiosity (Louie et al., Citation2021), and more coping mechanisms compared to Whites (Jackson et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, while homelessness and race are both known sources of stigma and discrimination, racial discrimination has been identified as an ‘old label’ from which POC have lifelong coping experiences (Zerger et al., Citation2014). In contrast, becoming homeless or receiving mental health/substance diagnoses are ‘new labels’ with more devastating impacts on one’s life and self-identity (Zerger et al., Citation2014). Taken together, lifelong exposure to experiences with racism, discrimination, stigma, and poverty (Conner et al., Citation2010) may lead to underreporting of mental health symptoms for POC, but also could serve as a protective factor absent in Whites in the face of homelessness. POC also generally find social support more valuable to mental health compared to Whites (Thomas Tobin et al., Citation2021), thus POC could have been more responsive to the relational component of SM. More research is needed to disentangle the relationships between mental health and race.

Limitations and future directions

While the results of this study are promising, there are several limitations. Due to the convenience sampling used and small sample size, outcomes may not be generalizable to other unsheltered PEH groups in other geographical locations with different characteristics. Although the study provided an opportunity for longitudinal analysis with measures at 6 months after enrollment, it would be beneficial to look at further long-term data. Potentially a greater degree of change might be found after individuals had a chance to experience stability in treatment and assisted housing for a period of >6 months. As self-report measures were used, results may be subject to pretest effects, recall issues, interviewer influence, and social desirability bias. Given the stigma associated with homelessness, race, mental illness, and substance use, participants may have overreported positive outcomes and underreported negative outcomes. Another limitation was the potential for multiple treatment inferences. While study participants could not have received services from the MHMR homeless clinic during the SM intervention, many other organizations in the service area provide supportive services to unsheltered PEH; the extent to which this may have occurred is unknown, and any services provided by other organizations could have influenced reported outcomes. Although bivariate analysis is a common practice in intersectionality research (Bauer et al., Citation2021), this technique may have provided an oversimplistic view of relationships between group pairings and outcomes. Future research should consider using multivariate techniques to better understand the factors contributing to group differences in outcomes.

Attrition rate may have further influenced outcomes. Of the 295 baselines collected, 231 were eligible to receive the six-month follow-up by the end of the grant period, of which 118 were relocated for the six-month follow-up. It was considered the 49% loss to follow-up rate may be explained, in part, by differences in baseline characteristics in which those who had follow-ups were more easily accessible due to having more severe needs compared to those lost to follow-up. Contrary to this expectation, participants who were lost to follow-up had poorer baseline scores overall on most behavioral health indicators compared to those with follow-ups. While the highly transient nature of the unsheltered PEH population, competing priorities, frequent relocation due to public camping bans, and communication barriers pose significant challenges for relocating participants for follow-up in general, it is plausible that underlying factors (e.g. motivation for treatment, stigma, attitudes toward healthcare workers) may be related to attrition. Such factors may also be confounders that influence change in behavioral health indicators over time.

It should also be acknowledged the SM program was established shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, which may have influenced outcomes. The physical and psychological impact of COVID-19 is well documented, and in addition to physical health risks and complications, COVID-19 has been associated with fear, social isolation, social stigma, anxiety, depression, maladaptive coping behaviors, increased substance use, and exacerbating preexisting mental and physical health conditions (Alonzi et al., Citation2020; Cullen et al., Citation2020; Dai et al., Citation2021; Haider et al., Citation2020; Kumar & Nayar, Citation2020). It is possible these factors influenced attrition rates and outcomes over time. Future research replicating the study across different timeframes is needed to enhance the generalizability of results.

While our field research design enhanced external validity, the 6-month timeframe between evaluations also posed a challenge in locating participants. Future research should consider incorporating analysis of clinical data collected from program staff that is collected on a more frequent basis, which may help in capturing more health data and enhance longitudinal designs.

Despite the limitations, this program evaluation has important implications for policy and future programs designed to help PEH. While street outreach programs are vital to ending homelessness and improving health equity for PEH, outreach programs are often underfunded, understaffed (Outreach, Citation2006), and inadequately equipped to help meet the highly complex needs of PEH (Lee & Donaldson, Citation2018). Homelessness is a public health crisis, which has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Barocas & Earnest, Citation2021; Tsai & Alarcón, Citation2022). Given the high societal costs of homelessness for all people, federal, state, and local governments are urged to devote more resources to homeless SM programs that work to eliminate homelessness and health inequities for PEH.

Equally important to the growth of SM program models is the emphasis needed on race, discrimination, stigma, structural racism, and classism in program designs. Discrimination and stigma occur across multiple marginalized statuses, including homelessness, race, mental illness, and substance use (Weisz & Quinn, Citation2018; Zerger et al., Citation2014), which may have negative multiplicative effects on health disparities and overall health outcomes. While the connection between stigma, discrimination, and poor health has been established (Van Zalk & Smith, Citation2019), little is known about the intersections of multiple marginalized statues and health outcomes (Weisz & Quinn, Citation2018), and no research has considered this in the context of SM. Future program development and research designs should give emphasize to SM models that address racism, stigma, and discrimination for people within these vulnerable groups address underlying structural racism and classism, and prevent PEH from exiting homelessness.

Conclusion

Results suggest that Street Medicine has been successful in providing trauma-informed behavioral health services to the unsheltered PEH community. The program appears to have been able to meet its goals to improve a variety of behavioral health outcomes, with important quality of life implications for those who exit homelessness. The study also successfully examined differences based on race and gender and found important differences that must be addressed in the context of homelessness. Interventions to improve mental health and reduce substance use among the unsheltered PEH remain an under researched area. Considering the high needs of this population, future research should continue to explore SM as a promising treatment option.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions contained in the publication do not necessarily reflect those of SAMHSA or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and should not be construed as such.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Linda K. Perna

Linda K. Perna is a Senior Evaluation Specialist for the MHMR Research Division. She holds a PhD in Psychology with a concentration in Social Psychology. She has almost eight years of experience in the mental health field working with vulnerable populations, with over four years in her current research role. Dr. Perna has served as the lead evaluator on several SAMHSA grants, including the Street Medicine project, and has designed various research protocols for the Division. Dr. Perna’s area of research expertise includes homelessness, medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction, psychological outcomes for people with Serious Mental Illness, social exclusion and belonging, and SPSS multivariate analysis. She has presented her research on Street Medicine outcomes and qualitative research on low-barrier buprenorphine treatment for unsheltered PEH.

Camille Patterson

Camille Patterson is the Director of Research at MHMR of Tarrant County. She has a PhD in Experimental Psychology and over 20 years of experience as a researcher with community mental health agencies. She has served as a lead evaluator on several SAMHSA grants and CMS projects involving co-occurring disorders, IDD, trauma, and integrated health. She has published several papers and made numerous presentations in these areas. Dr. Patterson’s areas of research expertise include substance use prevention and treatment, health psychology, trauma, RCTs, and multivariate data analysis using SPSS.

Amy A. Chairez

Amy A. Chairez has her Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees in Clinical Psychology. She has been in the Behavioral Health field since 1991 in various roles, including BS Counselor at an inpatient psychiatric hospital, Coordinator of Children’s Mental Health Services, Director of HIV Services, and Director of Adolescent Addiction Services. Amyserved as Program Manager of the Street Medicine program at MHMR of Tarrant County. In this role, Amy providedsupervision of the Street Medicine Team, which includeddaily oversight of the Street Medicine program, grant implementation and compliance with project activities, internal and external coordination, developing program materials, collaborating with community partners, and facilitating treatment team meetings.

Jenny Lewis

Jenny Lewis is a Research Assistant with MHMR. She joined MHMR almost 4 years ago and has worked on various projects serving vulnerable populations. She has a total of almost eight years of experience in mental health and has nine years of management and training experience. As a research assistant for MHMR, Jenny was the lead evaluator at Cooks Children Hospital, and she also worked on the AOT (Assistant Outpatient Treatment), and the Street Medicine program. Jenny was also a co-author of a qualitative research project with Dr. Perna on low-barrier buprenorphine treatment for unsheltered PEH.

Jacqueline Jordan

Jacqueline Jordan is an Evaluation Specialist II for the MHMR Research Division. She has an M.Ed. and MAOM (Master of Arts in Organizational Management). She joined MHMR nearly nine years ago and has over 15 years’ experience working with vulnerable populations in social services. She has worked with 1115 Waiver Outcomes, Family Drug Court, AOT (Assisted Outpatient Treatment Program), with JPS (John Peter Smith Hospital), Street Medicine, and was co-author on a qualitative research project on low-barrier buprenorphine treatment for unsheltered PEH.

Hajah Komara

Hajah Komara is an Evaluation Specialist II for the MHMR Research Division. She has dual Master’s degrees in Education and Health Services Administration. Hajah is a US Army Veteran and has been employed with MHMR for one year. She has over 10 years’ experience working with vulnerable populations in the social services sector with state issued benefits on various client and administrative levels, with a focus on helping individuals in need obtain benefits that support self-sufficiency. Hajah has also served as a benefits specialist and as a researcher for the Street Medicine program, including her co-authorship on a qualitative research project on low-barrier buprenorphine treatment for unsheltered PEH.

Harper Harris

Harper Harris is an Evaluation Specialist I for the Research Division at MHMR. Harper recently graduated in May of 2022 with a Bachelor of Science in Public Health to pursue a passion for medical research. She was recently hired for her current position but had the opportunity to intern with MHMR during her last semester of undergrad. Harper has prior experience collaborating with other health professionals and colleagues in creating a COVID-19 Vaccine Education Project with Texas Health Resources of Erath County to spread awareness to those in vulnerable populations and in adverse environments about beneficial health practices. Harper has also had the opportunity to work alongside the research team in the Street Medicine program.

References

- Alexander, A. C., Waring, J. J. C., Olurotimi, O., Kurien, J., Noble, B., Businelle, M. S., Ra, C. K., Ehlke, S. J., Boozary, L. K., Cohn, A. M., & Kendzor, D. E. (2021). The relations between discrimination, stressful life events, and substance use among adults experiencing homelessness. Stress and Health, 38(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3073

- Alonzi, S., La Torre, A., & Silverstein, M. W. (2020). The psychological impact of preexisting mental and physical health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S236–S238. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000840

- Assari, S. (2018). Health disparities due to diminished return among Black Americans: Public policy solutions. Social Issues and Policy Review, 12(1), 112–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12042

- Austin, A. E., Shiue, K. Y., Naumann, R. B., Figgatt, M. C., Gest, C., & Shanahan, M. E. (2021). Associations of housing stress with later substance use outcomes: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 123, 107076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107076

- Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.180109

- Barocas, J. A., & Earnest, M. (2021). The urgent public health need to develop “crisis standards of housing”: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 111(7), 1207–1209. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306333

- Bauer, G. R., Churchill, S. M., Mahendran, M., Walwyn, C., Lizotte, D., & Villa-Rueda, A. A. (2021). Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM-Population Health, 14(1), 100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798

- Baxter, A. J., Tweed, E. J., Katikireddi, S. V., & Thomson, H. (2019). Effects of housing first approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(5), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-210981

- Christensen, R. C. (2009). Psychiatric street outreach to homeless people: Fostering relationship, reconnection, and recovery. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20(4), 1036–1040. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0216

- Cohrdes, C., & Mauz, E. (2020). Self-efficacy and emotional stability buffer negative effects of adverse childhood experiences on young adult health-related quality of life. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(1), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.005

- Collins, S. E., Malone, D. K., Clifasefi, S. L., Ginzler, J. A., Garner, M. D., Burlingham, B., Lonczak, H. S., Dana, E. A., Kirouac, M., Tanzer, K., Hobson, W. G., Marlatt, G. A., & Larimer, M. E. (2012). Project-based housing first for chronically homeless individuals with alcohol problems: Within-subjects analyses of 2-year alcohol trajectories. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 511–519. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2011.300403

- Conner, K. O., Copeland, V. C., Grote, N. K., Koeske, G., Rosen, D., Reynolds, C. F., & Brown, C. (2010). Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(6), 531–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181cc0366

- Cullen, W., Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Mental health in the Covid-19 pandemic. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 113(5), 311–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

- Dai, J., Sang, X., Menhas, R., Xu, X., Khurshid, S., Mahmood, S., Weng, Y., Huang, J., Cai, Y., Shahzad, B., Iqbal, W., Gul, M., Saqib, Z. A., & Alam, M. N. (2021). The influence of COVID-19 pandemic on physical health–psychological health, physical activity, and overall well-being: The mediating role of emotional regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 667461. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.667461

- Daiski, I. (2005). The health bus: Healthcare for marginalized populations. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 6(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154404272610

- Doran, K., Moen, M., & Doede, M. (2020). Two nursing outreach interventions to engage vulnerable populations in care. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 31(4), 314–317. https://doi.org/10.1097/jan.0000000000000374

- Duhoux, A., Aubry, T., Ecker, J., Cherner, R., Agha, A., To, M. J., Hwang, S. W., & Palepu, A. (2017). Determinants of unmet mental healthcare needs of single adults who are homeless or vulnerably housed. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 36(3), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2017-028

- Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet, 384(9953), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Feldman, B. J., Kim, J. S., Mosqueda, L., Vongsachang, H., Banerjee, J., Coffey, C. E.Jr., Spellberg, B., Hochman, M., & Robinson, J. (2021). From the hospital to the streets: Bringing care to the unsheltered homeless in Los Angeles. Healthcare, 9(3), 100557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2021.100557

- Fisk, D., Rakfeldt, J., & McCormack, E. (2006). Assertive outreach: An effective strategy for engaging homeless persons with substance use disorders into treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32(3), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990600754006

- Frankeberger, J., Gagnon, K., Withers, J., & Hawk, M. (2022). Harm reduction principles in a street medicine program: A qualitative study. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 47(4), 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-022-09807-z

- Frankish, C. J., Hwang, S. W., & Quantz, D. (2005). Homelessness and health in Canada: Research lessons and priorities. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96(Suppl 2), S23–S29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403700

- Gilmer, C., & Buccieri, K. (2020). Homeless patients associate clinician bias with suboptimal care for mental illness, addictions, and chronic pain. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 11, 2150132720910289. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720910289

- Goering, P., Wasylenki, D., Lindsay, S., Lemire, D., & Rhodes, A. (1997). Process and outcome in a hostel outreach program for homeless clients with severe mental illness. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(4), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080258

- Haider, I. I., Tiwana, F., & Tahir, S. M. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult mental health. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(S4), S90–S94. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.covid19-s4.2756

- Hancock, N., Scanlan, J. N., Honey, A., Bundy, A. C., & O’Shea, K. (2015). Recovery Assessment Scale – Domains and Stages (RAS-DS): Its feasibility and outcome measurement capacity. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 624–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414564084

- Henwood, B. F., Rhoades, H., Hsu, H. T., Couture, J., Rice, E., & Wenzel, S. L. (2016). Changes in social networks and HIV risk behaviors among homeless adults transitioning into permanent supportive housing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(1), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815607686

- Jackson, J. S., Knight, K. M., & Rafferty, J. A. (2010). Race and unhealthy behaviors: Chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 933–939. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446

- Kerman, N., Polillo, A., Bardwell, G., Gran-Ruaz, S., Savage, C., Felteau, C., & Tsemberis, S. (2021). Harm reduction outcomes and practices in housing first: A mixed-methods systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109052

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). The Black-White paradox in health: Flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1677–1706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x

- Kidd, S. A. (2006). Youth homelessness and social stigma. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9100-3

- Kryda, A. D., & Compton, M. T. (2009). Mistrust of outreach workers and lack of confidence in available services among individuals who are chronically street homeless. Community Mental Health Journal, 45(2), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-008-9163-6

- Kumar, A., & Nayar, K. R. (2020). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health, 30(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052

- Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Baggett, T. P., Jenkins, D. M., Sripipatana, A., Sharma, R., Hayashi, A. S., Daly, C. A., & Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2012). Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: Findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Services Research, 48(3), 992–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12009

- Lee, W., & Donaldson, L. P. (2018). Street outreach workers’ understanding and experience of working with chronically homeless populations. Journal of Poverty, 22(5), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2018.1460737

- Llerena, K., Gabrielian, S., & Green, M. F. (2018). Clinical and cognitive correlates of unsheltered status in homeless persons with psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Research, 197, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.023

- Lo, E., Lifland, B., Buelt, E. C., Balasuriya, L., & Steiner, J. L. (2021). Implementing the street psychiatry model in New Haven, CT: Community-based care for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(8), 1427–1434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00846-1

- Louie, P., & Wheaton, B. (2019). The black-white paradox revisited: Understanding the role of counterbalancing mechanisms during adolescence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 60(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146519845069

- Louie, P., Upenieks, L., Erving, C. L., & Thomas Tobin, C. S. (2021). Do racial differences in coping resources explain the Black–White paradox in mental health? A test of multiple mechanisms. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 63(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465211041031

- Lynch, K. A., Harris, T., Jain, S. H., & Hochman, M. (2022). The case for mobile “street medicine” for patients experiencing homelessness. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(15), 3999–4001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07689-w

- Manning, R. M., & Greenwood, R. M. (2019). Recovery in homelessness: The influence of choice and mastery on physical health, psychiatric symptoms, alcohol and drug use, and community integration. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000350

- McManus, H. H., & Thompson, S. J. (2008). Trauma among unaccompanied homeless youth: The integration of street culture into a model of intervention. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 16(1), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770801920818

- Mejia-Lancheros, C., Lachaud, J., O’Campo, P., Wiens, K., Nisenbaum, R., Wang, R., Hwang, S. W., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2020). Trajectories and mental health-related predictors of perceived discrimination and stigma among homeless adults with mental illness. PLOS One, 15(2), e0229385. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229385

- Olivet, J., Bassuk, E., Elstad, E., Kenney, R., & Jassil, L. (2010). Outreach and engagement in homeless services: A review of the literature. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3(2), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874924001003020053

- Outreach (2006). ictj.org. Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://www.ictj.org/our-work/research/outreach

- Pamplin, I. J. R., & Bates, L. M. (2021). Evaluating hypothesized explanations for the Black-white depression paradox: A critical review of the extant evidence. Social Science & Medicine, 281, 114085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114085

- Paudyal, V., MacLure, K., Forbes-McKay, K., McKenzie, M., MacLeod, J., Smith, A., & Stewart, D. (2019). “If I die, I die, I don’t care about my health”: Perspectives on self‐care of people experiencing homelessness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12850

- Pauly, B., Reist, D., Belle-Isle, L., & Schactman, C. (2013). Housing and harm reduction: What is the role of harm reduction in addressing homelessness? The International Journal on Drug Policy, 24(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.008

- Petrovich, J. C., & Cronley, C. C. (2015). Deep in the heart of Texas: A phenomenological exploration of unsheltered homelessness. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000043

- Quickfacts Tarrant County, Texas (2023). census.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/tarrantcountytexas

- Rosenblum, A., Nuttbrock, L., McQuistion, H., Magura, S., & Joseph, H. (2002). Medical outreach to homeless substance users in New York City: Preliminary results. Substance Use & Misuse, 37(8–10), 1269–1273. https://doi.org/10.1081/ja-120004184

- Savage, M. (2016). Gendering women’s homelessness. Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies, 16(2), 43–64.

- Schick, V., Wiginton, L., Crouch, C., Haider, A., & Isbell, F. (2019). Integrated service delivery and health-related quality of life of individuals in permanent supportive housing who were formerly chronically homeless. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304817

- Shank, J. W., Iwasaki, Y., Coyle, C., & Messina, E. S. (2015). Experiences and meanings of leisure, active living, and recovery among culturally diverse community-dwelling adults with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 18(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487768.2014.954160

- Skosireva, A., O’Campo, P., Zerger, S., Chambers, C., Gapka, S., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2014). Different faces of discrimination: Perceived discrimination among homeless adults with mental illness in healthcare settings. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 376. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-376

- Somers, J. M., Moniruzzaman, A., & Palepu, A. (2015). Changes in daily substance use among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: 24-month outcomes following randomization to housing first or usual care. Addiction, 110(10), 1605–1614. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13011

- 2018 State of The Homeless Report (2018). ahomewithhope.org. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://ahomewithhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2018-SoHo-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Stergiopoulos, V., Dewa, C. S., Tanner, G., Chau, N., Pett, M., & Connelly, J. L. (2010). Addressing the needs of the street homeless. International Journal of Mental Health, 39(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411390101

- TCU Institute of Behavioral Research (2022). ibr.tcu.edu. Retrieved September 27, 2022, from http://ibr.tcu.edu

- Thomas Tobin, C. S., Erving, C. L., & Barve, A. (2021). Race and SES differences in psychosocial resources: Implications for social stress theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 84(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272520961379

- Thomas, G. (2005). Harm reduction policies and programs for persons involved in the criminal justice system. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Retrieved September 26, 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/5670450/Harm_reduction_policies_and_programs_for_persons_involved_in_the_criminal_justice_system

- Tommasello, A. C., Gillis, L. M., Lawler, J. T., & Bujak, G. J. (2006). Characteristics of homeless HIV-positive outreach responders in urban US and their success in primary care treatment. AIDS Care, 18(8), 911–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120500331297

- Tsai, J., & Alarcón, J. (2022). The annual homeless point-in-time count: Limitations and two different solutions. American Journal of Public Health, 112(4), 633–637. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306640

- Ungpakorn, R., & Rae, B. (2019). Health‐related street outreach: Exploring the perceptions of homeless people with experience of sleeping rough. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14225

- Unsheltered Homelessness and Homeless Encampments in 2019 (2021). huduser.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Unsheltered-Homelessness-and-Homeless-Encampments.pdf

- Van Zalk, N., & Smith, R. (2019). Internalizing profiles of homeless adults: Investigating links between perceived ostracism and need-threat. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 350. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00350

- Wang, D.-F., Zhou, Y.-N., Liu, Y.-H., Hao, Y.-Z., Zhang, J.-H., Liu, T.-Q., & Ma, Y.-J. (2022). Social support and depressive symptoms: Exploring stigma and self-efficacy in a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03740-6

- Ward, E. C., Wiltshire, J. C., Detry, M. A., & Brown, R. L. (2013). African American men and women’s attitude toward mental illness, perceptions of stigma, and preferred coping behaviors. Nursing Research, 62(3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnr.0b013e31827bf533

- Ware, J. E., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

- Weare, C. (2021). Housing outcomes for homeless individuals in street outreach compared to shelter. Journal of Poverty, 25(6), 543–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2020.1869664

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2014). U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. va.gov. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- Weisz, C., & Quinn, D. M. (2018). Stigmatized identities, psychological distress, and physical health: Intersections of homelessness and race. Stigma and Health, 3(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000093

- What is Street Medicine? (2022). streetmedicine.org. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.streetmedicine.org/about-us

- Whitman, A., De Lew, N., Chappel, A., Aysola, V., Zuckerman, R., & Sommers, B. (2022). Addressing social determinants of health: Examples of successful evidence-based strategies and current federal efforts. Retrieved August 14, 2022, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf