Abstract

The plea of accused persons, whether guilty or not, forms a central part of the legal process. Such a decision must exclusively rest with the accused person and be devoid of judicial and extrajudicial influence. This study seeks to interrogate the contexts within which accused persons determine their plea in court. It is argued that all the forms of plea are employed by accused persons as a means of navigating the sentencing outcomes of their cases. The study used a mixed-methods approach to data gathering and analysis. The respondents explained their guilty plea within the context of leniency, the expedition of cases, and to avoid prison remand. Those who pleaded not guilty largely thought of it within the context of identifying a legal loophole and having the opportunity to appeal their sentence after conviction. The extent to which the police influenced the accused to plead guilty requires further investigation.

Introduction

Generally, criminal proceedings take place in the form of a public hearing (Lama-Rewal, Citation2018), unless otherwise such hearing is considered not to be in the interest of public safety and morality as enshrined in Act 30, s. 16 (Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act, Citation1960) and articles 19(4) and 15 of Ghana’s constitution. According to Yeboah (Citation2016), the reading of the charges from the charge sheet initiates the criminal trial in court. This takes place after the accused has entered the dock. The court clerk reads the accusations, and if the accused does not understand English, the court interpreter translates the allegations into the local language for the comprehension of the accused (Santaniello, Citation2018). Thereupon, the accused can either take a plea of guilty, a plea of not guilty or refuse to plead (Section 171 of Act 30). According to Section 113 of Act 30, the lack of jurisdiction by a court could form the basis of plea refusal by an accused standing trial. This principle has further been established in Boni v The Republic (1971)179; and Republic v General Court Martial, Ex parte Mensah (1976). It is important to state that, when the charges pressed against an accused are revised or changed, the accused would have to be invited to take the plea again. The issue of taking pleas during criminal trials has become a subject of academic discourse in recent times due to the concern over the legal literacy of accused persons, and whether those without legal representation comprehend fully the consequences of their pleas.

The act of pleading guilty means a person formally admits to committing a crime of which he/she is accused (Redlich, Wilford, et al., Citation2017; Redlich, Bibas, et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, not pleading guilty means a person formally denies committing a crime of which he/she is accused. Pleading not guilty warrants a full trial, however, at any stage of the trial, a change of plea can be entered by the accused as evidenced in Robertson v Republic (J3 4 of 2014) (Chennells, Citation1991). A person may respond to a ‘no-contest’ (‘nolo contendere’) in some jurisdictions. This means that while the accused does not admit his/her guilt, he/she does admit the facts alleged in the indictment. In other words, the accused accepts the conviction but denies the factual admission of guilt. For sentencing purposes, a ‘no-contest’ plea is entered as a guilty plea (Rakoff, Citation2014; Bibas, Citation2014). Studies have shown that criminal trials in lower courts tend to be associated with a presupposition that the admission of guilt in court easily settles cases (Tata, Citation2007, Citation2010). From the perspective of court personnel, the works of Feeley (Citation1982), Heumann (Citation1978) and Tata (Citation2010) show that an admission of guilt by the defendant is inevitable. In England and Wales, 12% of offenders do not plead guilty (Ashworth & Roberts, Citation2013). In 2018, the US-based National Association of Criminal Defence Lawyers (NACDL) indicated that in the past 50 years, defendants in state and federal criminal prosecutions have chosen trial in less than 3% of instances compared to 20% of those arrested 30 years before. The other 97% of cases were settled through plea bargaining. Canada presents a similar situation as approximately 90% of criminal cases are resolved by guilty pleas (Kellough & Wortley, Citation2002). This has further been confirmed in a more recent study by Euvrard and Leclerc (Citation2017), as they found that most criminal cases are resolved by guilty pleas in Canada. In the case of China, plea bargaining rose from 33% to 83% from 2010 to 2013, respectively. According to a survey of 90 countries spanning 6 continents, 72% allow for guilty pleas (Fair Trials, Citation2016 cited in Redlich, Wilford, et al., Citation2017; Redlich, Bibas, et al., Citation2017). Data for criminal pleas in common law Africa are largely unknown, and the legal space for plea bargaining remains new.

To take a plea, the defendant must understand and decide on the plea decision. The lawyer(s) for the defendant(s) must also have a better appreciation of the plea regime to advise accordingly (Euvrard & Leclerc, Citation2017; Piccinato, Citation2004). The state attorney or prosecutor must also be knowledgeable about the plea economy. Negotiations between the defence lawyer and the state attorney or prosecutor often follow after a guilty plea. The judge, who stands in the middle, would have to decide whether to accept or reject the negotiated terms. Worthy of note is that these negotiated decisions are affected by social, cognitive and developmental forces (Redlich, Wilford, et al., Citation2017; Redlich, Bibas, et al., Citation2017).

Accused persons plead guilty or not guilty for different reasons. Pleading guilty means the criminal defendant aims to face the case and resolve the trial as quickly as possible (Gormley & Tata, Citation2019; Euvrard & Leclerc, Citation2017). The act of pleading guilty makes the process appear less expensive since it may not involve the hiring of a lawyer (Feeley, Citation1982). Some accused persons shared that pleading guilty helps to avoid being remanded in prison custody. Also, other accused persons shared that their inability to convince a judge as well as to avoid ‘dead time’ influenced their decision to plead guilty. This was explained by some accused persons that not pleading guilty meant they would be remanded in prison until their trial date but would be out of prison should they plead guilty (Euvrard & Leclerc, Citation2017; Roach & Mack, Citation2009). Chen (Citation2013) adds that pleading guilty emanates from the structural coercion of custodial remand. Vacheret et al. (Citation2015) indicated that some detainees pleaded guilty due to the pain of uncertainty, moral fatigue and the fear of losing time and one’s life. Pleading guilty is also sometimes interpreted as not wasting the time of the court (R. v. Anthony-Cook, Citation2016) while in some jurisdictions it allows the defence lawyer and the prosecutor to reach an agreement as to the sentence that the accused should receive. Plea bargaining sometimes results in the defendant receiving a lighter sentence or having some charges dropped (Gormley & Tata, Citation2019; Redlich, Citation2016; Bressan & Coady, Citation2017; King et al., Citation2005; Piccinato, Citation2004; R. v. Anthony-Cook, Citation2016). As McCoy stated, ‘there is nothing wrong with pleading guilty in the expectation of receiving a going rate of punishment. But […] there is a lot wrong with pleading guilty if that going rate after trial is so huge as to be the reason a defendant will make a pre-emptive guilty plea’ (2005, p. 90). Nonetheless, a person can plead guilty and receive nothing for it (Yan & Bushway, Citation2018). It is useful to state that a guilty plea not resulting in a lenient sentence depends on the jurisdiction – as the UK and Australia have sentencing discounts (either legislated or through common law) that ensure a discount for a guilty plea.

Aside from the discussed factors that influence guilty pleas, some studies have found certain personal characteristics, such as age, gender and minority status, to influence guilty plea decisions. Across the various age groups, Grisso et al. (Citation2003) found that adolescents were more likely to plead guilty compared to young adults. Redlich and Shteynberg (Citation2016) and Malloy et al. (Citation2014) looked at factors that influenced true and false guilty pleas, with their key findings highlighting the heightened risk among juveniles to plead guilty when innocent. These findings are similar to the work of Grisso et al. (Citation2003) and Bordens and Bassett (Citation1985) as they also found age to be a strong factor in plea decisions, or that, the younger the accused the more likelihood of a guilty plea. Nevertheless, in the work of Redlich et al. (Citation2010), age did not come up strongly as a determinant of plea decisions. The minority status of accused persons also influenced plea decisions (Davidson & Rosky, Citation2015). In the case of gender, men have been reported to be more likely to accept a guilty plea than women (Rousseau & Pezzullo, Citation2014; Davidson & Rosky, Citation2015). The work of Redlich et al. (Citation2010) also highlighted the increased risk of false guilty pleas amongst the mentally ill population.

Although the act of pleading guilty seems to present some advantages to the accused, the practice has heavily been criticized. According to Bibas (Citation2004) and Bowers (Citation2008), a guilty plea is rarely an informed and free decision as the pressure could emanate from the criminal justice system and the attorneys doing the bargaining. Plea bargaining, which is associated with a guilty plea, is sometimes based on limited financial resources (Poirier, Citation2005), lack of information and understanding of the judicial system (Redlich, Citation2016; Erickson & Baranek, Citation1982), and the mental health pressures that some accused persons may have suffered due to the fear of incarceration (Redlich, Citation2016: Flynn & Fitz-Gibbon, Citation2011). According to Redlich (Citation2016), most offenders enter guilty pleas without the requisite competence standard to do so. The use of undue influence by the police to get plea decisions from accused people has also been documented (Abel, Citation2017). All these make the validity of guilty plea decisions questionable (Redlich, Citation2016).

For those who pleaded not guilty, the literature reveals it allows the defendant and his/her lawyers ample time to prepare for the case. In instances where the trial ends in non-conviction of the accused, the accused is acquitted and discharged (Wodage, Citation2015). It may also enable the defence team to explore all legal avenues available for the case. In addition, the decision not to plead guilty was also found to depend on the nature of the evidence (Kutateladze et al., Citation2015; Emmelman, Citation1997). The lighter the evidence, the stronger the reason not to plead guilty and vice versa (Emmelman, Citation1997).

The notion of a plea (whether guilty or not) as a justice bargaining strategy questions the sentencing policies of countries or the idea that the sentencing differential is a discount. As stated by Gormley and Tata (Citation2019), the debate about plea-taking, bargaining and sentencing regimes cannot be easily resolved. It is challenging for one to perceive the sentence of an accused after a full trial without plea bargaining as the correct starting point. The penalties and discounts associated with criminal sentencing are fluid concepts (Bibas, Citation2004), and are seen as inevitable (Gormley & Tata, Citation2019). The extent to which accused persons and their defence team have used these propositions as a strategy for navigating the justice process remains scantly addressed, especially in Ghana. Until recently, plea bargaining was only available for certain offences such as Subsections (2) and (3) of Section 239 of Act 30, Section 35 of the Courts Act, 1993(Act 459), Act 959, and the Narcotics Control Commission Act, 2020 (Act 1019). In 2022, parliament passed into law the Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) (Amendment) Bill, 2022 to make provision for plea bargaining in the administration of justice. Under Section 162A of the Plea Bargaining Act, 2022 (Act 1079), ‘a person charged with a criminal offence may negotiate a plea agreement with the attorney general or anyone authorized by the attorney general at any time before the court delivers its judgment’. This new Act makes plea bargaining possible for all criminal offences except the following: piracy and hijacking, genocide, robbery, attempted murder, murder, treason, high treason, defilement, kidnapping, rape, abduction, as well as public elections offences. Before the Act came into force, plea bargaining was formally, informally and clandestinely negotiated between defence attorneys, state attorneys, and police prosecutors, and in some instances between accused persons and police prosecutors. This is to the extent that some offences not admissible for plea bargaining were also informally negotiated though they generally yielded less desired outcome for the accused. In addition, it is interesting to note that a guilty plea does not guarantee a more lenient sentence in Ghana as would be in other common law jurisdictions. This makes the issue of plea taken even more crucial for study in Ghana.

This study

Currently, there is a lacuna in this scholarly space in Ghana and most of Africa. A cursory search for literature on plea bargaining in Ghana only yields newspaper publications, hence warranting an academic investigation. This coincides with Gormley and Tata (Citation2019, p. 20), as they make the point that ‘research on why defendants do and do not plead guilty is desperately needed’. In this light, this article seeks to interrogate the contexts within which accused persons determine their plea in court. This study further examines the outcome of the pleas. Empirically, it is argued that all the forms of plea are employed by accused persons as means of navigating the sentencing outcomes of their cases. Addressing this gap will contribute significantly to the literature on criminal law, criminology and sociological jurisprudence.

Materials and methods

There are 43 prisons across the 16 regions in Ghana. The prisons include the following: 1 Senior Correctional Centre (formerly Ghana Borstal Institute), 1 Maximum Security Prison, 1 Medium Security Prison, 7 Central Prisons, 7 Female Prisons, 14 Local Prisons, 3 Open Camp Prisons and 9 Agricultural Settlement Camp Prisons (Yin, Citation2018; Yin & Kofie, Citation2021).

This study employed the mixed-method approach to data collection. That is a combination of quantitative and qualitative strategies. The sources of data were both primary empirical and primary non-empirical. The former was gathered using questionnaires and an in-depth interview guide whilst the latter were gathered from court proceedings. The units of analysis consist of inmates, defence attorneys/lawyers, police prosecutors and the court proceedings of inmates. The study settled on prison inmates, lawyers and police prosecutors because of their various roles in the criminal justice system. The police prosecutors are different from state attorneys even though they prosecute on behalf of the state attorney. The Legal and Prosecution Unit of the Ghana Police Service is entirely responsible for this function.

For the quantitative aspect, the study made use of a questionnaire as a data collection instrument. The questionnaire was made up of closed-ended questions with their corresponding response categories. The significance of using a questionnaire is that it provides some level of uniformity, standardization and greater structure to research. It also helps to understand things broadly or claim some level of generalizability (Roopa & Rani, Citation2012). Examples of questions asked during the questionnaire interview include but are not limited to the following: What offense did you commit? Why did you plead guilty? Why did you plead not guilty? Who influenced your guilty plea decision? Who influenced you to plead not guilty? The target prison population was 13,485 (as of October 2021). Using Andrew Fisher’s formula for calculating sample size, a sample of 374 was derived at a confidence level of 95%. The sample was distributed across 10 prisons. These prisons were Nsawam Medium Security Prison, Ankaful Maximum Security Prison, Kumasi Central Prison, Akuse Prison, Koforidua Prison, Sekondi Central Prison, Tamale Central Prison, Winneba Local Prison, Ho Central Prison and Jamestown Prison. The selection of these prisons was purposive, as it aimed to ensure that the prisons, as well as the prisoners, were geographically represented. Even though we assigned a sample of 374, we distributed 500 questionnaires through 10 research assistants. We did this because we were not sure of the response rate considering the COVID-19 situation in Ghana. At the end of the period slated for the questionnaire administration, that is from 25 July 2021 to 5 November 2021, we received 260 administered questionnaires. This represents an approximately 70% response rate, which is adequate for a study of a closed population. Out of this, 209 were male prisoners whilst 51 were female prisoners. The respondents were selected based on their willingness to participate in the study. It is important to state that only inmates formed the unit of analysis for the quantitative study. shows both the breakdown of sample distribution and gender involvement.

Table 1. Sample distribution and gender involvement.

The inmates who completed the questionnaire had different criminal records and were also serving different prison terms. The offences committed by these inmates include murder, rape, defilement, robbery, stealing, illegal use and possession of narcotics and defrauding by false pretence. The inmates were found to be serving different prison terms ranging from 1 year to death sentence. shows the various sentences being served by these inmates.

Table 2. Duration of prison sentence.

The different prison terms are a reflection of the different crimes inmates committed. These are presumptive sentences since the prisoners are aware of their estimated release date.

The quantitative approach was complemented by the qualitative technique of in-depth interviews. The instrument that aided the in-depth interviews was the interview guide. The interview guide was made up of open-ended questions. The essence of using the interview guide is that it allowed for some level of flexibility, in terms of probing further. Also, it aids in getting more detailed information about the subject of study. The units of analysis for the qualitative aspect of this research are prisoners, defence attorneys/lawyers and police prosecutors. The prisoners were selected and interviewed because of their experiential account from arrest to conviction. The defence attorneys were interviewed because they are seen to be knowledgeable about plea-taking and also provide professional legal advice to their clients on such matters. The police prosecutors, on the other hand, were interviewed because they understood the value of such offers (Redlich, Wilford, et al., Citation2017; Redlich, Bibas, et al., Citation2017). Also, in the interview process, there were allegations of coercion and deception from accused persons against police prosecutors. This added to the basis for their inclusion. The data from both defence attorneys and the prosecutors served to validate some of the responses from the inmates. In all, we interviewed five criminal lawyers, five police prosecutors and 20 inmates. The defence attorneys were recruited through a lead from an executive member of the Ghana Bar Association while the police prosecutors were also recruited through a lead from a member of the Ghana Police Service. Some of the questions asked were similar, however, the responses that required further probing differentiated each interview. This helped to validate and provide context for the questionnaire data. All the lawyers and prosecutors interviewed were based in Accra – the capital of Ghana.

As a way of tracking inmates for the in-depth interviews, we had access to 120 criminal case files across four regional capitals of Ghana – Koforidua, Kumasi, Cape Coast and Accra. The year range for these files was from 1990 to 2020. These files were accessed with the support of the court registrars. The files contained the charge sheet, the plea taken, records of examination and cross-examination and the ruling of the court. The relevance of the case files was that they provided the study with first-hand and conceivably more accurate information about the pleas of inmates in court. We tabulated the pleas of these convicted inmates. Of the tabulated pleas, 77 pleaded guilty whilst 43 pleaded not guilty. We noticed that out of the 77 who pleaded guilty, 12 had pleaded not guilty at the first instance but later changed their plea to guilty. Upon comparing the years of sentence in the docket to the date of data gathering, it was deduced that 63 of these prisoners were already on discharge. This meant that we could only track 57 inmates. However, we were able to trace 20. Out of these 20, the case files showed that 12 pleaded guilty whilst 8 pleaded not guilty. Out of the 12 that pleaded guilty, 4 had initially pleaded not guilty and later changed their plea to guilty. It is useful to state that inmates who participated in the in-depth interviews did not take part in the questionnaire interviews. This composition enabled us to understand from the perspectives of inmates the reasons behind such pleas, and most importantly the underlying factors that triggered the change of plea from not guilty to guilty. Interviewing lawyers, police prosecutors and inmates helped us to validate the information we gathered from the questionnaire administration. The in-depth interview technique offered us a unique depth of understanding which is difficult to gain from a closed-question survey (Yin et al., Citation2022). The inmates freely disclosed their experiences, thoughts and feelings about the rationale behind their pleas. shows the sample distribution of participants for the qualitative approach.

Table 3. Sample distribution of participants.

In addition to these data sources, we examined 30 case files/court proceedings of inmates who had committed the following offences: rape, defilement, robbery, stealing, defrauding by false pretence and drug offences. These court proceedings are different from the 120 case files discussed above. They were drawn from the Circuit Court in Winneba (a town in the Central region of Ghana) from 2010 to 2020. Using a random selection as the starting point, the systematic sampling approach was used to select these files out of 201. The random selection and the systematic approach were based on the principle of equal chance. Whilst we could have depended on the pleas of participants using the questionnaire data, we shared that accessing other case files from other courts in other parts of the country could help us broaden the data collection space as well as the data implication.

For data analyses, the STATA software (version 18 with a copyright license) was used to analyse the questionnaire data. Statistical analysis was made using descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages. In respect of the qualitative data, we transcribed the recorded interviews, searched for themes and response patterns, and analysed and drew conclusions. Using the principle of hermeneutic circle espoused by McCaffrey et al. (Citation2012), the contents and contexts of the transcripts were examined. Both the quantitative and qualitative data were presented concurrently. For the 30 case files, we collated the offences, pleas and sentences imposed by the court, and compared them with the minimum and maximum sentences defined by the 2015 sentencing guidelines. Based on this, we were able to determine the level of mitigation. The data were synthesized to produce a coherent analytical frame. With the data collection and analytical approaches, this study provides rather a broader understanding of the context within which inmates plead guilty or not.

On ethics, we sought and gained ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Cape Coast in Ghana. Given that this study is human-cantered research, we paid much attention to the issue of human dignity. We understand that, like all persons, prisoners have interests and integrity, which as researchers we did not set aside. We did our best to respect and protect the integrity and privacy of our participants, as well as safeguard them against harm and unreasonable strain. We considered participants’ autonomy and the right to self-determination. The participants were provided with adequate information about the data collection processes and the intended use of the results, that is, for academic purposes. The consequences of participation in the study were also shared with all participants. In terms of consent, for participants, especially prisoners, who could neither read nor write, oral consent was taken from them while those who could read and write signed the informed consent form. The consent was freely given and in an explicit form. Finally, confidentiality was assured. The personal data of participants were put in a de-identified manner to ensure anonymity. For example, the inmates were assigned numbers such as inmate 1, inmate 2, etc.

Results

This research aims to examine the reasons why accused persons plead guilty or not. This section presents the results of the study. We began by enquiring about the pleas taken by inmates in court. That is, whether they took a plea of guilty, not guilty or refused to take a plea. reveals the results of the pleas taken by the inmates.

Table 4. Plea in court.

The data show that participants either pleaded guilty or not guilty to the charges levelled against them by the prosecuting team. However, most of them pleaded guilty. There were no data to show that inmates refused to take a plea. In trying to understand why no inmate refused to take a plea, an inmate stated that;

After the facts and charges are read out to you in open court, you are asked whether you plead guilty or not. The court does not tell us whether we have the option to refuse to take a plea. What I know is that some people plead guilty with an explanation but that is not considered as being guilty. (Inmate 14)

Considering that most inmates pleaded guilty to the crimes levelled against them, we tried to comprehend whether the criminal offences committed by inmates played a role in the pleas they took. shows the cross-tabulation between offences committed by respondents and their plea in court.

Table 5. Cross-tabulation: offences and plea.

The data seem to suggest that people accused of murder and (or) robbery were more likely to take a plea of not guilty compared to those accused of rape, stealing, defilement, defrauding by false pretence and illegal use of narcotics. For the case of murder, it can be explained within the context of Section 199 of the Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act, Citation1960 (Act 30). Section 199 states as follows: (5) The Court shall not accept a plea of guilty in the case of an offence punishable by death, (6) If the Court decides not to alter the plea the Supreme Court shall have the right, on appeal against conviction, to order a re-trial if the Supreme Court is of opinion that a plea of not guilty should have been entered by the trial Court. This explains why all those convicted of murder took a plea of not guilty.

The study inquired about the reasons why some inmates pleaded guilty to the charges levelled against them. The responses of inmates are captured in .

Table 6. Reasons for pleading guilty.

The data show that the majority of respondents pleaded guilty for leniency. Others also did so for the case to be resolved quickly. The responses in are similar to some of the narratives from the in-depth interview. According to a participant:

I pleaded guilty in court because I knew that if I dragged the case in court, I might end up getting a harsher sentence. At least, not wasting the time of the court could earn you some leniency from the judge. (Inmate 4)

I had to plead guilty for the court to deal with me compassionately. Committing an offence without pleading guilty can make the sitting judge angry in the end. …by doing that one can get the maximum sentence. To avoid that, I decided to plead guilty. (Inmate 8)

You know (referring to the interviewer), if you plead guilty there is no ‘go and come’. You get your sentence immediately. (Inmate 1)

Pleading guilty does not involve the hiring of a lawyer. It makes the trial process less expensive. …the truth is that I don’t have the financial resources to hire a lawyer and pay all the associated costs that come with litigation. (Inmate 14)

Hiring the services of a lawyer can be very expensive. The whole trial process is expensive. To avoid this, that is why I had to plead guilty at the first appearance. I also did not have the money to battle the issue in court. (Inmate 7)

I pleaded guilty because I committed the offence. I was caught in the act. There was no need to plead otherwise when evidence abounds. (Inmate 9)

For other inmates, it was about saving their families from the emotional abuse the trial may subject them to. An inmate said that:

Going to court and having your family members present can be emotionally draining to you and the family. The case I am convicted for is not my first case in court and I know how my mother wept outside the court. I don’t want that to happen again. That is why I had to plead guilty. (Inmate 13)

When you don’t plead guilty you will be remanded in prison custody. When this happens, you are treated just like other convicted prisoners. The convicted prisoners are even better. At least, for them, they know their fate but for a remand prisoner, your next date of going to court is even in doubt. I had no option but to plead guilty. (Inmate 15)

Just as those who pleaded guilty gave their reasons, reveals the details of why some respondents pleaded not guilty to their charges in court.

Table 7. Reasons for pleading not guilty.

The survey data show that for some inmates, pleading not guilty was an opportunity for them to identify a legal gap and to also appeal the sentence at a later date. During the qualitative interview, participants also shared why they pleaded not guilty to the offence. According to a participant:

I am currently appealing my sentence because my lawyers have identified some errors in the trial. If I had pleaded guilty, how could I have appealed my sentence using this loophole? (Asking the interviewer). (Inmate 2)

…If you plead guilty, on what basis will you appeal your sentence again? All grounds will be based on leniency and subjected to the judge. At any day and time, I will plead not guilty so I can come back to challenge the trial. (Inmate 3)

If you plead not guilty, it gives your lawyers the space to study the case and approach it well. That was what happened in my case. They raised certain issues which the prosecutors could not address even though they had evidence against me. I could have been given a higher sentence if not for the critical legal issues my lawyers raised in court. (Inmate 12)

Anything can happen in court. I could be acquitted and discharged through a good defence. It is all about the judge listening to both sides. It happens all the time. That is why I pleaded not guilty. (Inmate 11)

For me (referring to himself), the evidence against me was not strong enough to get me a maximum sentence. I thought I had a chance of acquittal but unfortunately, I was not lucky. (Inmate 14)

For me, I have heard about the judge (name withheld). If you plead guilty or not, he will not have mercy on you, that is why I pleaded not guilty to go through the trial. After all, if found guilty he will still give me the maximum sentence. However, the advantage is that I can come back later to appeal. At that time, the judge may have been transferred to another court or region. (Inmate 10)

It can be deduced from the data that, some accused persons see the trial and sentencing outcomes as a ‘legal trial balloon’. Or, in other words, a legal chess game. Those who pleaded not guilty did so because they felt such a plea offered them the opportunity to appeal their sentence after they had discovered a legal loophole. Others felt it allowed their legal counsels to prepare for their case, and that it was possible the trial could end in acquittal. One can also deduce that some participants pleaded not guilty with the idea of coming back to challenge the trial after the significance of the case had decayed. Significantly noted, not all of such cases were successful because there were incidents of judges throwing out cases on technicalities. The idea expressed by participants about some accused persons being acquitted and discharged ‘all the time’ is a pipe dream; it cannot be generalized. For individual inmates who can afford legal representation, and assemble all the supporting evidence, this could happen on the merits of the case. The data also implies that some inmates pleaded not guilty because the evidence against them was not strong enough.

After asking the respondents why they pleaded guilty or not, we went ahead to ask who influenced their plea. shows the sources of guilty plea advice.

Table 8. Sources of guilty plea advice.

The findings in the survey research were collaborative with the qualitative interview. During the in-depth interview, a participant said:

It was the police officer who asked me to plead guilty so that the judge will not give me a high sentence. I pleaded guilty but the court did give me a higher sentence. (Inmate 8)

The police officer told me to plead guilty so that it will make his work less difficult. And that if I plead not guilty, he will ensure that the judge gives me the maximum sentence. (Inmate 1)

It is not my duty to influence the plea of any accused person, and I do not engage in that. (Inmate 14)

I do my job as a prosecutor. When the case comes before me, I follow due process. I don’t influence the plea of the accused. (Inmate 7)

I have heard of cases where the police deceive the accused to plead guilty. The intention is for the accused to make the work of the prosecutor easy. In that case, there will be no need for any legal tussle between the prosecutor and the defence attorney. It happens…. (Inmate 13)

Whilst I was in police custody my cell inmates adviced me to plead guilty to the charge. (Inmate 4)

It was my lawyer who said I should plead guilty. I think he said so after considering the nature of my case. He said the evidence against me was strong and there was no way I was going to escape prison. The lawyer said he would prefer to plead for leniency on my behalf than to go into the case. (Inmate 9)

If I notice my client has a bad case, I normally advice them to plead guilty. A bad case here means that my client was caught in the act and the police have strong evidence to pin him/her down. …no need for any unnecessary legal battle. (Inmate 15)

I pleaded guilty myself. …I knew the outcome of the case from the beginning so there was no need. That is why I pleaded guilty. (Inmate 6)

No one influenced me to plead guilty. It was my own decision. (Inmate 20)

Like the participants who pleaded guilty, those who took an opposing plea also experienced some influence. However, there were variations in the data compared to those who pleaded guilty. The survey data in show the sources of advice for inmates who did not plead guilty.

Table 9. Sources of not guilty advice.

From the in-depth interviews, the participants who pleaded not guilty shared that they were influenced by their lawyers, other cell inmates and themselves. According to an inmate:

When my lawyer visited me at the police station, he adviced me not to plead guilty in court. …he shared that I had a chance in the case. (Inmate 10)

It was my lawyer who asked me to take a plea of not guilty and that he could defend me. (Inmate 17)

When I was arrested and placed in a police cell, the inmates there adviced me that I should never plead guilty in court. And I took their counsel. (Inmate 11)

I had the knowledge of not pleading guilty from other cell inmates. I was told pleading guilty was a disastrous move. (Inmate 5)

It is my duty as a lawyer to guide my client in the best interest possible. So, if my client has a chance to avoid prison, I have no reason to ask him to plead guilty. (Inmate 2)

…going on a full trial is the right thing. I do inform my clients about the consequences of pleading guilty or not guilty, but I normally advice them to plead not guilty. Anyway, they have the final decision. (Inmate 3)

It was my decision to plead not guilty. I was not influenced by anyone. (Inmate 16)

The data imply that, for the majority of accused persons who pleaded not guilty, their lawyers and cell mates generally influenced their plea. It can be inferred from the data that if accused persons are financially resourced, expertly counselled and legally represented, they are less likely to take a guilty plea at the suggestion of a police prosecutor.

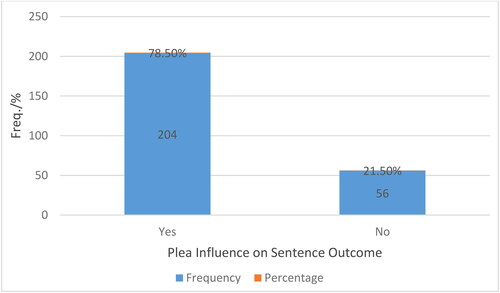

In respect of whether the pleas influenced the sentencing outcome, shows that 204 (78.5%) of respondents said their plea of guilty or not guilty influenced the sentence whilst 56 (21.5%) said their plea did not influence the sentence.

During the in-depth interview, participants shared their views as thus:

Yes! My plea of guilty yielded some results. The judge read in open court that for not wasting the time of the court and for being remorseful he will give me a sentence of 15 years instead of 25 years for rape. (Inmate 7)

My plea of guilty did the magic for me. The judge did not give me the maximum sentence for rape. (Inmate 20)

After pleading not guilty, the case went on full trial. In the end, my lawyers managed to raise certain issues the prosecutor could not defend. Based on that some charges were dropped and I got the minimum sentence. (Inmate 11)

Even though I got a sentence of 40 years after a full trial, I appealed the sentence after serving 2 years in prison. The appeal was based on some lapses my lawyers observed after reading the court proceedings. My appeal was successful as I got 15 years slashed from the 40 years. (Inmate 10)

My plea did not yield any results in court. The judge did not consider it at all. (Inmate 5)

The judge gave a blind eye to my plea. I was thinking pleading guilty would influence her but she showed no mercy. (Inmate 13)

After interviewing inmates, we went a step further to examine the court proceedings of 30 inmates and compared their offence, plea, and sentence to what is determined by the 2015 sentencing guidelines of Ghana. The maximum sentence as depicted in means the court took into consideration no or fewer mitigating factors.

Table 10. Comparison between given sentence, minimum sentence, maximum sentence and mitigation achieved.

reveals that, for accused persons who pleaded not guilty, two had a maximum sentence whilst nine had a mitigated sentence. For those who were accused of robbery, of which the majority pleaded not guilty, their sentences were high compared to the other offences. In respect of those who pleaded guilty, 1 person received a maximum sentence whilst the majority (18) had a mitigated sentence. Noteworthy, for crimes such as rape and defilement, the plea of guilty or not hardly had a great mitigation impact. However, largely, the data implies that accused persons who pleaded guilty to their charge stood a higher chance of receiving a mitigated sentence.

Discussion

From the data, participants pled either guilty or not guilty to the offences brought against them by the prosecuting team. The majority, nevertheless, pleaded guilty. This finding, though a smaller percentage (61%), is somehow consistent (in terms of majority response) with the Crown Prosecution Service Annual Report and Accounts (Citation2018–2019) that about 91% of convicted inmates took a plea of guilty. This is similar to what was observed in the US as 94% of state convictions and 97% of federal convictions are the result of guilty pleas [see Lafler v Cooper 566 U.S. Rep. 156 (2012) and Missouri v Frye 566 U.S. 134 (2012)]. This finding is also not poled apart from the work of Friedman (Citation1978) who found that most offenders pleaded guilty to their charges. The data also shows that some participants changed their initial plea from not guilty to guilty. In respect of the change of plea, the data reverberates the work of Chennells (Citation1991).

In respect of the motivations behind inmates’ guilty pleas, the data indicate that some inmates did so to secure leniency from the court. The finding of leniency as a reason for pleading guilty is consistent with the findings of Gormley and Tata (Citation2019), Helm (Citation2019) and Rakoff (Citation2014), as they found that some people standing trial pleaded guilty to receiving a lighter sentence. This finding is also consistent with Redlich (Citation2016), who found that accused persons who pleaded guilty had some form of reduced sentences, charges and collateral consequences such as not registering as a sex offender. Corroborating with the work of Redlich et al. (Citation2018), they also revealed that offenders who pleaded guilty had 75% of their charges dropped. Other inmates indicated the expedition of cases and to avoid full trial as the basis for pleading guilty. This finding is not different from the findings of Gormley and Tata (Citation2019), Cheng (Citation2013), Tata (Citation2010), Alge (Citation2009), Mackenzie (Citation2007) and Neuman (1968), who discovered that accused persons pleaded guilty so that their cases could be resolved as quickly as possible to avoid full trial. Our findings also indicate that some inmates agreed to plead guilty because they did not have the financial resources to hire an attorney and bear other costs associated with the trial process. Feeley (Citation2017), Cheng (Citation2013) and Feeley (Citation1982) made similar observations as they found that defendants pleaded guilty to avoid the cost of hiring a lawyer. The finding also resonates with Mackenzie (Citation2007), who indicated that among the reasons for inmates to plead guilty was the lack of financial resources as well as to save the state the costs associated with trial. This finding begs a question about functional legal aid in Ghana. The literature suggests that the legal aid department is understaffed and resourced to meet the needs of many (Yin et al., Citation2021).

For other inmates, pleading guilty was about avoiding prison remand. This finding validates the works of Euvrard and Leclerc (Citation2017) and Vacheret et al. (Citation2015), who found that some accused persons pleaded guilty to avoid prison remand. According to the work of Vacheret et al. (Citation2015), getting out of prison remand was the priority of many accused persons no matter the price. Pleading guilty to escape prison remand points to a major troubling flaw of the criminal justice system in Ghana. ‘I have no option but to plead guilty’ is really a miscarriage of justice especially if one has not committed any offence. The deplorable nature of prison conditions in Ghana makes prison remand akin to social death. Likewise, being on remand, in effect, is akin to the accused being banished from society (Yin, Citation2018). The explanation of inmates who pleaded guilty to escape remand can better be appreciated within the context of statistics for remand prisoners. According to the Ghana Prisons Service’s Annual Report for the years 2006, 2007 and 2008, the average remand population in detention were 3788, 4211 and 4285, respectively. This suggests that the remand population in the country’s prisons is steadily increasing. Between 2006 and 2007, the percentage growth was 11.2%, while between 2007 and 2008, it was 1.2%. As of April 2022, the remand prison population stood at 1492 which is 10.3% of the total prison population. Amidst the appalling conditions of overcrowding and easy transfer of communicable diseases in prison (Yin, Citation2022), it is therefore not surprising that some accused persons pleaded guilty to avoid remand.

We also found that, in the case of other inmates, they admitted the offence because they committed it. This implies that all things being equal, some accused people who committed the offence are more likely to accept a guilty plea. This finding goes hand-in-hand with the works of Dervan and Edkins (Citation2013) and Gazal-Ayal and Tor (Citation2012) who indicated that guilty people are more likely to enter a guilty plea than innocent ones. It was also found that for some inmates who pleaded guilty, it was a way to spare themselves and their families the emotional distress that accompanies a court trial. Morris (Citation2023) shared that trial processes burdened families, offenders and victims psychologically.

The study found that for inmates who did not plead guilty, it was because of the possibility of being acquitted and discharged if the case goes to full trial. This result authenticates the findings captured in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (2015) report that not pleading guilty offered accused persons the possibility of acquittal. This is also true for the scholarly work of Wodage (Citation2015), who indicated that a trial could end in non-conviction thereby leading to the acquitted and discharged of the accused. It is important to state that the idea expressed by participants about some accused persons being acquitted and discharged ‘all the time’ is a pipe dream; it cannot be generalized. For individual inmates who can afford legal representation, and assemble all the supporting evidence, this could happen on the merits of the case. It also came up from the results that inmates pleaded not guilty based on lighter evidence against them. This correlates with the findings of Kutateladze et al. (Citation2015), that the decision not to plead guilty was found to depend on the strength of the evidence. Emmelman (Citation1997) also validates the point that the lighter the evidence, the stronger the reason not to plead guilty and vice versa. For some inmates, such a plea allowed them to appeal their sentence after some time when they had discovered a legal weakness and the significance of their case had decayed. One can deduce that some participants pleaded not guilty with the idea of coming back to challenge the trial after the significance of the case had decayed.

On the sources of inmates’ influence to plead guilty, the study found police prosecutors to be generally responsible. The data show that police prosecutors used some degree of coercion and (or) deception to lure the accused into pleading guilty. The prosecutors negotiated with the accused for a lighter sentence upon admitting guilt, even though the inmates did not mostly receive the said lighter sentence. The finding on police influence is similar to that of Abel (Citation2017), that the police had an undue influence on the plea decisions of accused people. Lawyers and family members of accused persons were also found to be a source of influence on the decision to plead guilty or not. For the lawyers, the strength of the evidence counted much in either accepting or rejecting plea decisions. The works of Reed (Citation2020) and Lee and Ropp (Citation2020) showed that lawyers have a great deal of influence on their clients to accept a guilty plea. Surveys from other studies concur with this finding as they reveal that prosecuting attorneys, defence attorneys, friends and family members influenced the decision to reject or accept a plea (Redlich et al., Citation2010; Viljoen et al., Citation2005; Bordens & Bassett, Citation1985). The data further showed that the influence of police prosecutors and defence lawyers was informed by the opportunity to avoid examining the evidence against the accused. This corresponds with Bradshaw et al. (Citation2012) who indicated that guilty pleas make prosecutors and lawyers escape the task of thoroughly examining criminal evidence.

Only a few inmates admitted to their guilt without any influence. It is alarming that more than half of the respondents said they were influenced by the police. This begs the question, is the influence of the police in conformity to the operation of the justice system? What are the police to gain from this undue influence? Apart from escaping the task associated with the trial, one can only conjecture: the evidence of their effectiveness in extracting guilt from the accused; clearing the trial roll of otherwise remanded inmates; and from the standpoint of the police, there is always the danger of the eyewitness/material witness not showing up to the courthouse to testify, which could lead to emptying the case. All combined, this could serve to explain the possibility of the police prosecutors intimidating the accused or using undue influence to extract confessions. This is unconstitutional and a violation of Section 9 of the Ghana Police Service Handbook. It is against this that Yeboah (Citation2016) argued that if individual rights are not protected during arrest and trial, it could lead to abuse of power that may have detrimental consequences on the accused.

For the majority of accused persons who pleaded not guilty, their lawyers generally influenced their plea. This result is consistent with the findings of Henderson and Levett (Citation2019) and Redlich et al. (Citation2016), as they found that lawyers influenced the plea decisions of their clients. Reed (Citation2020) and Lee and Ropp (Citation2020) make a similar accession that some lawyers do influence their clients not to plead guilty. Some inmates, though not the majority, indicated that the decision not to plead guilty was based on their own volition. The influence of other actors on plea decisions, whether guilty or not, is not the ideal practice. Accused persons have the final power to make plea decisions as established in McCoy v. Louisiana & S. Ct. 16–8255,8255 (2018). However, it is not out of place for a defence lawyer to effectively or appropriately counsel his/her client on plea offers (Missouri v. Frye, 2012).

The data show that participants’ plea, whether guilty or not, played a role in determining the sentencing outcome. This finding resonates with Subramanian et al. (Citation2020) and Malone (Citation2020), as they found that the pleas of accused persons had an impact on the sentencing outcome. This explains why accused persons employed the forms of plea – guilty or not as a means of navigating criminal sanctions. This establishes that, depending on the situation, any of the pleas was a strategic move. Nevertheless, it was more favourable for those who pleaded guilty as the majority had their sentence mitigated (Roberts & Pina-Sánchez, Citation2022; Gormley et al., Citation2020). The data also show that the specific plea decisions of inmates did not always yield the desired outcome for them. This data echoes the work of Garoupa and Stephen (Citation2008) and Yan and Bushway (Citation2018), that a person can plead guilty and receive nothing for it.

Conclusion

In this study, we interrogated the contexts within which accused persons determined their plea in court. We further examined the outcome of the pleas. We argued that all the forms of pleas are employed by accused persons as means of navigating the sentencing outcome of their cases. The study employed the use of surveys and interviews in data gathering. The study also made use of primary non-empirical data such as the court proceedings of inmates.

The study found that defendants had different reasons for taking a plea of guilty or not. For those who pleaded guilty, they elucidated their reasons in the context of leniency in sentencing, the expedition of the case, the expensive nature of the court process, avoiding emotional trauma, and avoiding prison remand. To some inmates, their plea of guilty was an actual admission of guilt. Those who pleaded not guilty explained their reasons within the context of identifying a legal loophole, having the opportunity to appeal the sentence, space for legal preparation and defence and having the opportunity to be acquitted and discharged. Apart from the very few who took a plea of guilty based on their own decision, the majority were influenced by the police prosecutors, lawyers, cell inmates, and family members.

Of all the sources of influence to plead guilty, the extent to which the police prosecutors influenced the accused to plead guilty is a cause for concern. There is nothing unusual for a police officer to testify in court on the arrest and charging of an accused person. It is, however, problematic when the police make it a duty to talk an accused person in their custody to plead guilty. This undermines the due process of law – fair trial – and denies the accused the opportunity to challenge the merits of the case.

Per the data, the strategic pleas of accused persons had varying impacts on their sentencing outcomes. Whilst the strategic pleas tend to have favoured the majority of convicted persons, that was not entirely the case, as some accused persons who either pleaded guilty or not still had the maximum sentence associated with their crimes imposed on them.

Authorship contribution statement

Elijah Tukwariba Yin: Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published.

Constantine K. M. Kudzedzi: Analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting of the article, and revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published.

Nelson Kofie: Analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting of the article, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who in diverse ways contributed to the data-gathering process, especially the inmates, police officers, lawyers, and prison officers. Thanks also go to our research assistants. We are also grateful to Prof. Peter Atudiwe Atupare and the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable review comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Data for this research can be accessed by sending a direct email to the corresponding author. However, as this study borders on prisoners, no sensitive data will be sent out upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abel, J. (2017). Cops and pleas: Police officers’ influence on plea bargaining. The Yale Law Journal, 126(6), 1. https://www.yalelawjournal.org/essay/cops-and-pleas-police-officers-influence-on-plea-bargaining

- Alge, D. (2009). [Pressures to plead guilty or playing the system? An exploration of the causes of cracked trials] [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Manchester.

- Ashworth, A., & Roberts, J. V. (Eds.). (2013). Sentencing guidelines: Exploring the English model. OUP Oxford.

- Bibas, S. (2004). Plea bargaining outside the shadow of trial. Harvard Law Review, 117(8), 2463. https://doi.org/10.2307/4093404

- Bibas, S. (2014). Plea bargaining’s role in wrongful convictions. In A. D. Redlich. J. R. Acker, R. J. Norris, & C. L. Bonventre (Eds.), Examining wrongful convictions: Stepping back, moving forward (pp. 157–19). Carolina Academic Press.

- Bordens, K. S., & Bassett, J. (1985). The plea bargaining process from the defendant’s perspective: A field investigation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 6(2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp0602_1

- Bowers, J. (2008). Punishing the innocent. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 156, 1117–1179.

- Bradshaw, P., Sharp, C., Duff, P., Tata, C., Barry, M., Munro, M., & McCrone, P. (2012). Evaluation of the reforms to summary criminal legal assistance and disclosure. The Stationery Office.

- Bressan, A., & Coady, K. (2017). Guilty pleas among indigenous people in Canada. Department of Justice Canada.

- Chen, K. (2013). Pressures to plead guilty. Factors affecting plea decisions in Hong Kong’s magistrates’ courts. British Journal of Criminology, 53(2), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azs064

- Chennells, R. (1991). The unrepresented accused: Change of plea from guilty to not guilty. South African Journal of Criminal Justice, 4, 200.

- Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act. (1960). Act 30.

- Crown Prosecution Service Annual Report and Accounts. (2018–2019). HC 2286, p. 7.

- Davidson, M. L., & Rosky, J. W. (2015). Dangerousness or diminished capacity? Exploring the association of gender and mental illness with violent offense sentence length. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(2), 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-014-9267-1

- Dervan, L. E., & Edkins, V. A. (2013). The innocent defendant’s dilemma: An innovative empirical study of plea bargaining’s innocence problem. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 103, 1.

- Emmelman, D. S. (1997). Gauging the strength of evidence prior to plea bargaining: The interpretive procedures of court-appointed defense attorneys. Law & Social Inquiry, 22(04), 927–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.1997.tb01093.x

- Erickson, R. V., & Baranek, P. M. (1982). The ordering of justice. A study of accused persons as dependants in the criminal process. University of Toronto Press.

- Euvrard, E., & Leclerc, C. (2017). Pre-trial detention and guilty pleas: Inducement or coercion? Punishment & Society, 19(5), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474516670153

- Fair Trials. (2016). Hard bargain: Human rights protection in global plea bargaining [Paper presentation]. Paper Presented at the Understanding Guilty Pleas Research Coordination Network Meeting, Arlington, VA.

- Feeley, M. M. (1982). Plea bargaining and the structure of the criminal process. Justice System Journal, 7(3), 338–354. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/jusj7&div=30&id=&page=

- Feeley, M. M. (2017). The process is the punishment: handling cases in a lower criminal. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Flynn, A., & Fitz-Gibbon, K. (2011). Bargaining with defensive homicide: Examining Victoria’s secretive plea bargaining system post-law reform. Melbourne University Law Review, 35(3), 905–932.

- Friedman, L. M. (1978). Plea bargaining in historical perspective. Law & Society Review, 13(2), 247–259. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3053251.pdf. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053251

- Garoupa, G., & Stephen, F. H. (2008). Why plea-bargaining fails to achieve results in so many criminal justice systems: A new framework for assessment. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 15(3), 323–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X0801500303

- Gazal-Ayal, O., & Tor, A. (2012). The innocence effect. Duke Law Journal, 62, 339.

- Gormley, J. M., & Tata, C. (2019). To plead? Or not to plead? “Guilty” is the question. Re-thinking plea decision-making in Anglo-American Countries. In C. Spohn & P. K. Brennan (Eds.), Handbook on sentencing policies and practices in the 21st century (pp. 208–234). Routledge.

- Gormley, J., Roberts, J. V., Bild, J., & Harris, L. (2020). Sentence reductions for guilty pleas: A review of policy, practice and research. https://sentencingacademy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Sentence-Reductions-for-Guilty-Pleas-3.pdf on 16/01/2024.

- Grisso, T., Steinberg, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., Scott, E., Graham, S., Lexcen, F., Reppucci, N. D., & Schwartz, R. (2003). Juveniles’ competence to stand trial: A comparison of adolescents’ and adults’ capacities as trial defendants. Law and Human Behavior, 27(4), 333–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024065015717

- Helm, R. K. (2019). Constrained waiver of trial rights? Incentives to plead guilty and the right to a fair trial. Journal of Law and Society, 46(3), 423–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12169

- Henderson, K. S., & Levett, L. M. (2019). Plea bargaining: The influence of counsel. Advances in Psychology and Law, 4, 73–100.

- Heumann, M. (1978). A note on plea bargaining and case pressure. Law & Society Review, 9(3), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053170

- Kellough, G., & Wortley, S. (2002). Remand for plea. Bail decisions and plea bargaining as commensurate decisions. British Journal of Criminology, 42(1), 186–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/42.1.186

- King, N. J., Soule, D. A., Steen, S., & Weidner, R. R. (2005). When process affects punishment: Differences in sentences after guilty plea, bench trial, and jury trial in five guidelines states. Columbia Law Review, 105(4), 959–1009.

- Kutateladze, B. L., Lawson, V. Z., & Andiloro, N. R. (2015). Does evidence really matter? An exploratory analysis of the role of evidence in plea bargaining in felony drug cases. Law and Human Behavior, 39(5), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000142

- Lama-Rewal, S. T. (2018). Public hearings as social performance: Addressing the courts, restoring citizenship. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 17(17), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.4413

- Lee, J. G., & Ropp, J. W. (2020). “Sometimes I’m just wearing the prosecutor down”: An exploratory analysis of criminal defense attorneys in plea negotiations and client counseling. Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice & Criminology, 9(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.21428/88de04a1.2168ad3e

- Mackenzie, G. (2007). The guilty plea discount: does pragmatism win over proportionality and principle? Southern Cross University Law Review, 11, 205–223.

- Malloy, L. C., Shulman, E. P., & Cauffman, E. (2014). Interrogations, confessions, and guilty pleas among serious adolescent offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 38(2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000065

- Malone, C. (2020). Plea bargaining and collateral consequences: An experimental analysis. Vand. Law Review, 73, 1161.

- McCaffrey, G., Raffin-Bouchal, S., & Moules, N. J. (2012). Hermeneutics as research approach: A reappraisal. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(3), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691201100303

- Morris, P. (2023). Prisoners and their families. Taylor & Francis.

- Piccinato, M. P. (2004). La reconnaissance préalable de culpabilité. Ministry of Justice.

- Poirier, R. (2005). La négociation des sentences du point de vue des avocats de la défense. Criminologie, 20(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.7202/017251ar

- Rakoff, J. (2014). Why innocent people plead guilty. The New York Review of Books. http://wwnitybooks.comii/articles/archives/2014/nov/20/why-innocent-people-plead-guilty on 13/01/2024.

- Redlich, A. D. (2016). The validity of pleading guilty. Advances in Psychology and Law, 2, 1–26.

- Redlich, A. D., Bushway, S. D., & Norris, R. J. (2016). Plea decision-making by attorneys and judges. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 12(4), 537–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9264-0

- Redlich, A. D., Wilford, M. M., & Bushway, S. (2017). Understanding guilty pleas through the lens of social science. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23(4), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000142

- Redlich, A. D., Yan, S., Norris, R. J., & Bushway, S. D. (2018). The influence of confessions on guilty pleas and plea discounts. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 24(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000144

- Redlich, A. D., & Shteynberg, R. V. (2016). To plead or not to plead: A comparison of juvenile and adult true and false plea decisions. Law and Human Behavior, 40(6), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000205

- Redlich, A. D., Bibas, S., Edkins, V. A., & Madon, S. (2017). The psychology of defendant plea decision-making. The American Psychologist, 72(4), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040436

- Redlich, A. D., Summers, A., & Hoover, S. (2010). Self-reported false confessions and false guilty pleas among offenders with mental illness. Law and Human Behavior, 34(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-009-9194-8

- Reed, K. (2020). The experience of a legal career: Attorneys’ impact on the system and the system’s impact on attorneys. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 16(1), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-051120-014122

- Roach, A. S., & Mack, K. (2009). Intersections between in-court procedures and the production of guilty pleas. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 42(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.42.1.1

- Roberts, J. V., & Pina-Sánchez, J. (2022). Sentence reductions for a guilty plea: The impact of the revised guideline on rates of pleas and ‘cracked trials’. The Journal of Criminal Law, 86(5), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220183211041912

- Roopa, S., & Rani, M. S. (2012). Questionnaire designing for a survey. Journal of Indian Orthodontic Society, 46(4_suppl1), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10021-1104

- Rousseau, D. M., & Pezzullo, G. P. (2014). Race and context in the criminal labeling of drunk driving offenders: A multilevel examination of extralegal variables on discretionary plea decisions. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 25(6), 683–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403413493089

- Santaniello, L. (2018). If an interpreter mistranslates in a courtroom and there is no recording, does anyone care: The case for protecting LEP defendants’ constitutional rights. Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy, 14, 91.

- Subramanian, R., Digard, L., Melvin, W. I., & Sorage, S. (2020). In the shadows: A review of the research on plea bargaining. Vera Institute of Justice.

- Tata, C. (2007). In the Interests of clients or commerce? Legal aid, supply, demand, and ‘ethical indeterminacy’ in criminal defence work. Journal of Law and Society, 34(4), 489–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2007.00402.x

- Tata, C. (2010). A sense of justice: The role of pre-sentence reports in the production (and disruption) of guilty pleas. Punishment & Society, 12(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474510371734

- Vacheret, M., Brassard, V., Vacheret, M., & Prates, F. (2015). Le vécu des justiciables. La détention avant jugement au Canada: Une pratique controversée, montréal (pp. 125–143). Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Viljoen, J. L., Klaver, J., & Roesch, R. (2005). Legal decisions of preadolescent and adolescent defendants: Predictors of confessions, pleas, communication with attorneys, and appeals. Law and Human Behavior, 29(3), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-3613-2

- Wodage, W. Y. (2015). Note: Burdens of proof, presumptions and standards of proof in criminal cases. Mizan Law Review, 8(1), 252–270. https://doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v8i1.8

- Yeboah, E. A. (2016). [Right to fair trial in Ghana criminal proceedings] [Doctoral Dissertation]. Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

- Yan, S., & Bushway, S. D. (2018). Plea discounts or trial penalties? Making sense of the trial-plea sentence disparities. Justice Quarterly, 35(7), 1226–1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1552715

- Yin, E. T., & Kofie, N. (2021). The informal prison economy in Ghana: Patterns, exchanges, and institutional contradictions. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 2004673. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2004673

- Yin, E. T., & Seiwoh, B. M. (2021). Costs and delays in accessing justice: A comparative analysis of Ghana and Sierra Leone. In E. T. Yin & N. F. Kofie (Eds.) Advancing civil justice reform and conflict resolution in Africa and Asia: Comparative analyses and case studies (pp. 112–139). IGI Global.

- Yin, E. T. (2018). [Religion as an organizing principle in Ankaful maximum security prison, Ghana] [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cape Coast.

- Yin, E. T. (2022). The material conception of religion among inmates in the Ankaful maximum security prison, Ghana. Masyarakat, Kebudayaan Dan Politik, 35(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.20473/mkp.V35I32022.252-264

- Yin, E. T., Boateng, W., & Kofie, N. (2022). Family acceptance, economic situation, and faith community: The lived experiences of ex-convicts in Ghana. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 5(1), 100240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100240

- Yin, E. T., Korankye-Sakyi, F., & Atupare, P. A. (2021). Prisoners’ access to justice: Family support. Journal of Politics and Law, 14(4), 113. https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v14n4p113

Case laws

- Boni v. The Republic 179 297 U.S. 278. (1936).

- Lafler v Cooper 566 U.S. Rep. 156. (2012).

- McCoy v. Louisiana, S. Ct. 16–8255. (2018).

- Missouri v Frye 566 U.S. 134. (2012).

- Rv Anthony-Cook [2016]. 2 SCR 204

- Republic v. General Court Martial, Ex parte Mensah. (1976). JELR 67571 (CA)

- Robertson v. Republic (J3 4 of 2014). (2014). GHASC 169 (28 May 2014)