?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In Ethiopia, a sizable section of the rural population depends on agriculture for a living. However, because of low agricultural output, a large number of rural households experience chronic poverty and food insecurity. Unfortunately, mothers and women are shocked by the food shortage to feed their children and families. This means women participate in rural non-farm economic activities (RNFEA) to generate income and cope with these challenges. Thus, the study explored the determinants of women’s participation in RNFEA in the districts of Goncha Siso Enese and Enebsie Sar Midir, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The study was based on survey data collected from 358 randomly chosen women in the four kebeles from the study district. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were employed to analyze the data. The result indicates that about 59% of the respondents are non-participants in RNFEA due to the negative cultural (95%) and social (90) factors: lack of transport and market infrastructure (59%), lack of experience and skill (43%) and a combination of all (26%). While the binary logistic regression result indicated that age, livestock size, land size, food shock and distance to the market significantly affect women’s participation in RNFEA; there is still a rich supply of female labor force participants who are underutilized in farming due to a lack of awareness creation, negative sociocultural factors and poor infrastructure. Solving these related problems can help transfer them to the non-farm sector, which may support the upgrading of rural industries and promote the implementation of rural revitalization.

1. Introduction

Given that agriculture is the main source of livelihood for most people in Ethiopia, 79% of the country’s population lives in rural areas (Chekol et al., Citation2022a). Agriculture contributes 43% of GDP, 83% of foreign exchange profits and 79% of job possibilities in Ethiopia (Bor & Adan, Citation2023). However, in the study area, the farming community is highly affected by persistence risk and uncertainties arising from natural hazards (such as drought and untimely rainfall, pests and disease), market fluctuations (price uncertainty), social uncertainty (unequal ownership of land resources), state actions and civil conflict (Bor & Adan, Citation2023; Chekol, Abetie, et al., Citation2023; Nagler & Naudé, Citation2017). Their income from agriculture fluctuates as a result of these issues, and commercializing agriculture is the most severe instance of risky economic activity (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). Conversely, Ethiopia’s agricultural revenue per capita has been poor due to the country’s growing population, comparatively small amount of arable land and low sector productivity (Nagler & Naudé, Citation2017). Due to these, the majority of rural households work in subsistence farming systems, where they are subject to long-term poverty, food shortages and low agricultural income (Chekol, Tsegaye, et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, due to Ethiopia’s seasonal agricultural production, which typically spans from May/June to December/January, the majority of rural households experience unemployment for the remaining portion of the month (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021). Following these economic problems, the growth rate of real GDP in Ethiopia declined from 12.6% in 2010 to 7.6% in 2016, and then to 5.3% in 2022 (NBE, Citation2022).

However, women traditionally make the majority of the decisions about domestic tasks like cooking, fetching water, collecting firewood, caring for children and cleaning the house with about 90% of the household (Mmakola & Sithole, Citation2023). Ethiopian women are not financially free, especially in rural areas where they usually stand against the decisions of their male guardians because they are dependent on their husbands’ earnings (Menelek Asfaw, Citation2022). Unfortunately, women face a shocking shortage of food supplies to feed their families and children as a result of traditional subsistence farming combined with the negative perception of women working from home (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021; Thierno et al., Citation2021; Nagler & Naudé, Citation2017). Nonetheless, women’s participation in the labor force is shifting globally these days. According to Todaro and Smith (Citation2012), they play three roles in society: reproductive, productive and communal involvement.

In all the above cases, women’s participation in rural non-farm economic activities (RNFEA) can be extremely useful in reducing poverty, increasing farmer income and utilizing surplus agricultural labor (Todaro & Smith, Citation2012; Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). Due to the risk and uncertainty involved with subsistence agriculture in Ethiopia, households that diversify their sources of income by engaging in non-farm activities are better able to withstand negative shocks (Chekol, Abetie, et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, only wealthy households frequently have access to high-quality jobs (Loison, Citation2015). The possibility of entering the off-farm workforce and one’s capacity for employment will determine the ensuing repercussions for economic development (Dzanku, Citation2019; Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019; Rijkers & Costa, Citation2012).

To address these issues, earn extra money and improve their well-being, the rural women in the study area participate in non-farm rural economies. The non-farm sector can impact the rural economy in a number of ways (Fan & Xin, Citation2019). First, by creating jobs, non-farm work reduces the demand for land in underdeveloped areas (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021). Second, the money earned from non-farm pursuits can boost household income overall and, as a result, increase the amount that can be invested in agricultural activities (Dufera et al., Citation2023; Chekol, Tsegaye, et al., Citation2022). It reduces fluctuations in revenue and makes it possible to implement some profitable but ‘risky’ agricultural technology, leading to the transformation of agriculture (Chekol, Abetie, et al., Citation2023; Chekol, Giera, et al., Citation2023). Third, non-farm revenue serves as a means of sustaining money, which is crucial for both present and future consumption and investment. As a result, the circumstances guaranteed the necessity of concurrent advancement in agricultural and non-agricultural economic activities to support one another and ultimately achieve sustainable rural development. Economic activity related to farms and non-farms goes hand in hand. As a result, rural women’s involvement in non-farm enterprises is currently being acknowledged more and more (Bor & Adan, Citation2023).

The factors influencing rural women’s participation in the non-farm sector must be rigorously examined in order for intervention to effectively boost women’s involvement. Local communities’ standard of living would increase as a result of good policies and initiatives that increase their exposure to non-farm income-generating possibilities (Bor & Adan, Citation2023; Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019; Rijkers & Costa, Citation2012). Therefore, in order to combat poverty, increase food security, and improve livelihoods, a critical investigation of the non-farm job options available for women in the study region as well as the factors driving women’s engagement in activities other than agriculture is essential.

Several studies have investigated the factors that influence rural household participation in non-farm activities. For example, according to the study by Adefris and Woldeyohannes (Citation2021), age, marital status, access to the market and distance to the market were the most important factors in determining household participation in the Ambo district of Ethiopia. Bor and Adan (Citation2023) also found that market distance, household income, credit access and gender were the main factors for non-farm participation in the Gambella region of Ethiopia. However, no actual proof was discovered to study rural households in general and women’s participation decisions in RNFEA in the study area.

In rural Ethiopia, women’s contributions to the economy are valued, but they are not acknowledged. Therefore, it is essential for women’s growth and the achievement of their economic potential to recognize and assist women in overcoming their difficulties. Considering that, despite their frequent hiding, silence and lack of appreciation, rural women are among the most potent untapped natural resources in the world (Adejo et al., Citation2021). Ethiopia has a population that is over 50% female (Ahmed, Citation2021), and it is best to use all of this human capital for long-term, sustainable economic growth (Chekol, Citation2019). Without the participation of women and girls, economic transformation is not attainable. Scholars concluded that women should always be at the center of any development drama (Todaro & Smith, Citation2012). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the factors that influence women’s decisions to participate in RNFEA in Goncha Siso Enese and Emebsie Sar Midir districts of Ethiopia.

2. Research methodology

2.1. Description of the study area

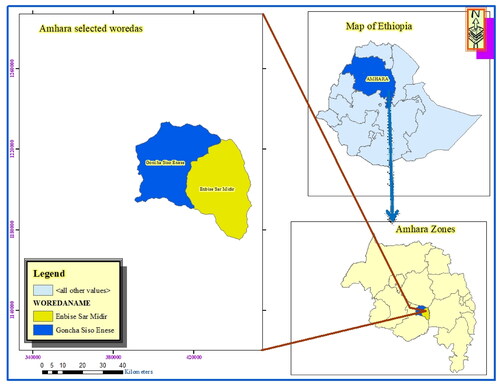

This study was conducted in two randomly selected rural woredas of the Amhara Region of Ethiopia, namely, Goncha Siso Enese and Enebsie Sar Midir (). Goncha Siso Enese woreda is located 343 km away from Addis Ababa and 151 km away from Bahir Dar, whereas Enebsie Sar Midir is found 365 km away from 180 km. Addis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia, while Bahir Dar is the capital city of the Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia. Specifically from the Amhara region, the two selected woredas were found between 11′60′′ and 12′40′′ latitudes north and 38′01′′ longitudes east. With respect to the organizational structure, Goncha Siso Enesie woreda comprises two urban cities, 41 rural kebeles and a total of 47,213 agricultural households. Whereas Enebsie Sar Midir is comprised four urban cities and 31 rural kebeles, with a total number of 23,992 agricultural households. These woredas are caused by an irregular distribution of rainfall over time and location. In terms of agro-ecological location, Goncha Siso Enese is comprised 12% highland, 48% midland and 40% lowland. Enebsie Sar Midir is located in 14% highland, 33% midland and 53% lowland.

Figure 1. Location of Goncha Siso Enese and Enebsie Sar Midir Woredas. Source: Own construction using ARC-GIS (2023).

The main sources of income in these woredas are small-scale agriculture, including crop production (teff, barley, wheat and maize) and livestock populations (such as cattle, goats, sheep, chickens, bee colonies and equine). In addition, non-farm businesses, such as petty trade, the sale of wood and charcoal, the making and sale of traditional beverages and fired food, pottery, etc., are also highly prevalent in rural areas as a source of income to supplement household food expenses. However, none of the studies were conducted, particularly on women’s participation in these businesses and in these woredas. Thus, this study explores women’s participation decisions in RNFEA. Finally, the study areas (Goncha Siso Enesie and Emebsie Sar Midir) are located in .

2.2. Ethics (informed verbal consent)

Before performing face-to-face individual interviews with the participants, the study’s objectives were explained to them. The women were informed that participation was entirely voluntary and that any information they submitted would be kept private and anonymous. Participants were informed that they might end the interview at any moment without worrying about being incorrect, as well as decline to participate and not provide any answers. The questionnaire employed in this study did not require ethical clearance because it was non-intrusive, did not provide any ethical conundrums, and did not pose a danger of harm to the women. Lecturers in Ethiopia’s higher education institutions are complementary, working in research and community services. So, without receiving funds from the university, researchers are doing research with their own funds and the letters supporting a legitimate researcher are taken from the departments. So, informed verbal consents between the researcher and respondents are agreed upon, and questionaries’ would have been distributed and collected.

2.3. Sample design, procedure and data collection

The target population of this study was women who live in rural areas of Goncha Siso Enesie and Enebsie Sar Midir districts, East Gojjam Zone of Amhara Ethiopia. First, two kebeles from Enebsie Sar Midir (Derj and Jangebeya) and two from Goncha Siso Enese (Goshera and Debreyakob) woredas were purposefully chosen. The decision to select was influenced by the accessibility of the sites to visit as well as the possibilities for non-farm participation among kebeles. Using a population list from sample kebeles, the target sample size was then determined based on the number of rural households’ populations. Finally, a simple random sampling strategy based on Yamane’s (Citation1967) formula was used to select 358 sample houses at random.

The sample size of rural households will be determined using the generic formula determined by Yamane (Citation1967). A 95% confidence interval and ±5% margin of error will be used in the study. The sample size was ascertained using the following formula:

where n = sample size required, N signifies the total household population under study who are potentially engaged in nonfarm economic activities, e = the desired level of precision, i.e. margin of error (0.05).

Thus, ,

,

The distribution of the sample size across the kebeles was based on their proportion size to the total sampling frame as shown in .

Table 1. Sample kebeles.

Ultimately, the calculated size of 358 total samples from all kebeles was chosen at randomly using the random sampling approach after applying the household list of rural households. Between December 2021 and February 2022, statistics from the Goncha and Enebsie districts were collected.

Both qualitative and quantitative information on women’s involvement in non-farm enterprises was acquired from primary sources in order to meet the study’s objectives. Five professionally trained enumerators questioned rural women in the research area in person and via semi-structured questions for the cross-sectional survey. Potential RNFEA participants were chosen at random using structured questioners, and pertinent information was gathered from them. Data on a variety of socioeconomic variables of the household and infrastructure components were collected using a pretested questionnaire. The questioner also touches on factors that influence non-farm economic participation, obstacles to overcome and reasons for participating.

2.4. Method of data analysis and model specification

Both descriptive and inferential statistics will be employed in the analysis. The data was also analyzed using Stata 14 version of statistical software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics are explained by means of the frequency distribution, percentage and mean value of several determining factors. Furthermore, a review was conducted of the data collected from the conversation and other participants. Because the dependent variable is binary, a binary logistic regression model was used to assess the inferential statistics. Women who work in rural nonfarm businesses therefore have two options: they can choose to take part in the RNFEA or not. The logistic regression model is used to assess probability when the independent variable is a measurement scale variable and the dependent variable is binary (Cramer, Citation2003). The ensuing presumptions were established:

In the model, If Y is the dependent variable; it can take values of either 1 or 0.

Yi = 1 if a women participate in RNFA

Yi = 0 otherwise,

where Y represents the dependent variable, which is the participation rate of women in RNFEA, and Y can have a value of either 1 or 0.

Therefore, the following is the specification of the logistic regression model used to estimate the likelihood of women participating (Pi):

(1)

(1)

Similarly, the probability of RNFA participation is

(2)

(2)

When dividing (1) by (2), it gives odds ratio:

The logit model is a logarithmic transformation of the odds ratio.

where Li is the log of the odds ratio; e is the base of natural logarithms; α is a constant; X1, X2,…, Xk are explanatory variables; β1, β2, …, βκ are estimated parameters corresponding to each explanatory variable; k is number of explanatory variables; and ει is the random error. The log-likelihood estimation was used to compare the marginal values of the explanatory variables for choosing to participate in RNFA to check whether the difference was significant.

Here, description of the variable used in the regression and their measurement for women participation in RNFA has shown below ().

Table 2. Description of variables and its measurement.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Description of socioeconomic variables of the sample women

The decision of women to participate in RNFEA has been greatly influenced by the socioeconomic characteristics of the sample women. Both the dummy and continuous variables in the analysis were investigated (see ). In this instance, the t value statistical technique reveals a statistically significant difference between participants and non-participants in terms of age, education level, family size, land size, animal size and distance to the market. Comparing these two groups using a simple test reveals that the participating women have larger families (4.74) and greater levels of education (2.89 years) than the non-participant women. Larger families tend to spend more money; therefore, there’s a greater chance that they will engage in generating income to diversify and augment their sources of income rather than solely depending on agriculture. A larger family size also suggests a larger amount of excess labor in the household, which raises the likelihood of involvement. Children are expected to behave appropriately in their families, according to Ethiopian family culture. For instance, when the mother leaves the house to go about her business, the older children are expected to take care of their smaller siblings and to conduct household chores. All of these things enable the mother to take part in RNFEA. The outcome is in line with earlier findings (Ahmed, Citation2021). Participant women have completed more years of schooling, which is more than their counterparts. Education could provide the woman with knowledge about markets and business ideas, as well as how to make money from sources other than farming, in order to better supports their families. An educated woman can readily spread training and skills that can entice eager women to engage in non-farm activities, as well as have the opportunity to be involved in public or private organizations. Numerous investigations came to the same conclusion (Dufera et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, a woman is more likely to hunt for income sources outside of farming the more educated she is (Bor & Adan, Citation2023).

Table 3. Descriptive test statistic mean difference between participant and non-participant.

Conversely, the average age of women, the size of the land, the size of livestock and the distance to the market were all statistically and substantially lower for the participants than for the comparison group. The average age of respondents who did not engage in non-farm activities was 58.2 years, whereas the mean age of those who did engage in income-generating activities was 39.9 years. This indicates that RNFEA participants are younger than non-participants. This is linked to the fact that younger women participate in socioeconomic activities more actively and with greater energy than do elderly women (Alemu et al., Citation2022). In a similar vein, participation land sizes (0.38) are substantially less than non-participant land sizes (2.07). This is due to the fact that when land size increases, so does the income from agricultural output, and women’s opportunities to look for other sources of income decline because they already have enough money from these activities (Alemu et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, because they can rear more cattle and boost productivity, farmers with larger land holdings are able to raise more livestock, produce more arm output and pay for greater family expenses while participating in fewer RNFEA events. In contrast, landless farmers must work in non-farm ventures to provide for their families because their farm’s revenue is insufficient to pay for their children’s education, their household’s food expenses and other utility charges with a small land area (Demie & Zeray, Citation2016; Asfaw et al., Citation2017). The participant women’s livestock size (2.53) was smaller than the non-participant women’s livestock size (5.67). The most likely reason for this outcome is that households with animals have greater opportunities to sell cattle and livestock products for a higher profit, which boosts their purchasing power and helps to guarantee their food security. The outcome is in line with earlier research that demonstrated larger livestock and land areas have a detrimental effect on non-farm participation (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021; Tesgera et al., Citation2023). Additionally, the participant’s walking distance to the market (1.92) is less than the non-participant’s walking distance (3.51). The residence home is far from the market; therefore, the opportunity to take part in the RNFEA is denied. This is a result of the women’s lengthy travel, which makes it more difficult for them to get to the market to buy supplies and sell their goods. Women are less inclined to travel long distances and spend their time since they bear the heavy weight of domestic responsibilities (Montanari & Bergh, Citation2019; Dufera et al., Citation2023).

With regards to dummy variables, there is a significant difference between participants and non-participants of women in terms of marital status, food shock and awareness (). The results indicate that 49.8% of the participant women are either female-headed or unmarried. Compared to male-headed households and married women, unmarried women are more likely to run non-farm enterprises. Compared to their counterparts, in rural areas, women who participate in non-farm economic activities (which use less energy) are less productive in agriculture. Furthermore, farming is more difficult in rural areas since it requires more physical power from females than from males. Women who are single, divorced, widowed or unmarried are free to relocate anywhere and actively participate in non-farm economies. Accordingly, women who are single and heads of household are more likely to engage in non-farm economic activity (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021). Furthermore, single women report lower levels of stress than married women who take care of their spouse and children at home (Fan & Xin, Citation2019; Mashapure et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, families tend to participate in non-farm economic activities when they have food shortages and insufficient agricultural revenue. The study’s findings indicated that, in the event of a food scarcity, nearly all of the respondents – about 99% of them – engaged in non-farm rural economic activity. Household heads in rural areas participate in non-farm economic activity because food security is guaranteed, and diversifying sources of income can reduce the risk associated with declining agricultural production (Dzanku, Citation2019; Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). According to Tesgera et al. (Citation2023), the primary sources of income for them are trading commodities, cattle, handicrafts and other items to meet household consumption expenses. Diversification into non-farm employment not only provides rural households with a stable additional source of income, but it also helps to balance their income and spending (Thierno et al., Citation2021; Nagler & Naudé, Citation2017; Osarfo et al., Citation2016).

Table 4. For categorical variables (Chi-square test).

With respect to hours allocated for domestic activity, there is a significant difference between hours allocated for domestic activity between participants and non-participants (). The non-participant women are spending more time on domestic activities, such as caring for the children and elderly, fetching water and collecting firewood, and cooking and cleaning the household (Fan & Xin, Citation2019). Hence, they are less interested in participating in non-farm business. On the other hand, unmarried and single women are less burdened by domestic activity, are relatively free to move outside of home, and are more likely to participate in RNFEA. On average, rural women who chose to diversify in non-farm businesses spent less time on domestic activity (10.87 h per day) compared to those who did not diversify (15.07 h per day) (). This suggested that performing more domestic activity tasks tended to reduce the likelihood of engaging in non-farm diversification strategies due to the multiple work-family duties of females (Mashapure et al., Citation2022). The result is similar to the previous findings that showed that increasing hours per day for domestic activity reduces the likelihood of women’s non-farm diversification (Diallo et al., Citation2023). Moreover, the childbearing of mothers and the time factor were the main challenges for women’s participation in rural non-farm activities in Nigeria (Itunnu & Joseph, Citation2021).

Table 5. Daily hours allocated for domestic activity and participation decision in RNFA.

3.2. Types of rural non-farm economic activities performed by women in the study area

The study area has a unique mix of non-farm activities. Women’s participation in RNFEA outside of agriculture differs from location to location. But, mostly the study areas or selected kebeles are highland and middle-highlands from both districts. Thus, depending on the site’s location and the community’s living circumstances, each of the kebeles from the district had a different sort of non-farm activity that was the subject of the study. As indicated in , the highest share of the non-farm activities that women are involved in are petty trade (71.7%), followed by the making and sale of local beverages (such as Tellan and Katikala) (55.19%). The other important non-farm businesses are the making and sale of malting (31%), the sale of charcoal and wood (19.3%), and the sale of cooked or fired food (14%). Women from the highland areas, specifically from ‘Goshera kebele’, are largely involved in traditionally making barley and wheat malts, and by loading on their backs and going a long distance, they sell the malt to those who are living in lowland areas for the purpose of making traditional beverages. On the other side, women who are near the main roads are engaged in the sale of cooked or fired foods and retailing beverages as well. But, in all the study areas, women are involved in petty trade (such as trading agricultural crops) over long distances, either by carrying the crops on their backs or loading them on donkeys.

Table 6. Types of non-farm economic activities.

A portion of uneducated women who lack other sources of income turn to non-farm economic endeavors as a means of subsistence and as a means of augmenting their income from agriculture. Engaging in non-farm business ventures is a crucial economic activity that supports disadvantaged women in securing their livelihoods, starting their own businesses and making money. One woman, a 38-year-old mother of four residing in Goshera Kebele, responded, ‘Non-farm businesses are my livelihood, and I have no other alternatives,’ when asked individually what and why she was involved in non-farm industries. She went on to explain:

Before fifteen years ago, I lived far from my original place because of marriage and the search for better living conditions. At that time, we supported our livelihood through agricultural work, and we were able to produce and consume enough food. Unfortunately, we are displaced from our homes, and my husband died due to internal civil conflicts in our area. Then, after the death of my husband, we returned to my family with my four children without any property. When we came here, my father didn’t have enough agricultural land and property to give to me, and there are no relatives who are willing to support us. So it was difficult for me to live with my children. As a result of this, I started to live with my four children alone in a small house, and I decided to have two businesses, such as the preparation and sale of Malts and Areki. I am buying barley and wheat products for an input for Malts and Areki from the market on Tuesday by traveling a four-hour road on one side. On the same day and in the same market, two activities are being done: selling Areki and buying inputs. Then, on the next Saturday, the prepared Malts are sold by traveling to another market for 2 and ½ hours. Then the profit we got was enough to cover my household expenses and help me survive my life independently with my children. In addition, after engaging in these two businesses, i.e., the selling of Malts and Areki, a few months ago, I started to save money in the bank.

I was divorced because my husband was not a hard worker farmer; rather, he always intoxicated, returned to his house at night, and I always fought with him, but he could not change his behaviour. Previously, I spent the day cooking and taking care of my children, and the rest of the time talking with my neighbours. To fulfil our household needs, especially in the summer season, we sell my cattle, and occasionally we also sell our land. As a result of this, I decided to separate and return to my family with three children and little property, but I have no mature children to plough my land and to do other labor-related activities. Consequently, the only option that I have is to give my land to my brother for equal product sharing. However, the produce I get from my land is not enough to cover my household expenses, and life is becoming very difficult to handle. After this, I needed to find other income-generating activities, and as a result, I started to engage in petty trades in vegetables and sometimes cereals on Tuesday and Saturday by going for a 45-minute trip to the market. Through the trading of cereals and vegetables, I started to get enough money to support my household consumption with the produce that I obtained from my land. At this time, I am properly feeding my children, and I am also living in good condition.

3.3. Motivations that cause rural women’s to participate in non-farm economic activities

Households in the study area have experienced a mixed farming system that includes crop production and livestock rearing. But the farming system is subsistence and earns a low income, and households are unable to cover their expenditures. Due to this, many women’s lives are shockingly short of food for their children. Thus, rural women’s decision to participate in RNFEA to supplement family income is in response to hardship or emerging economic opportunities (Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021). As exhibited in , 90% of the participant’s women were involved in RNFEA due to inadequate farm income and the need to supplement household consumption. Similarly, 83.49% of participants were due to a lack of farm land and declining productivity, followed by 58.4% for buying property and might-buy farm input motives. Moreover, 51.89% and 46.7% of participant women’s were due to unexpected expenses (due to emergence of health expenditure or unexpected price change) and growing family size, respectively. As an opportunity (due to the existence of better infrastructure, the seasonal nature of agricultural labor, and the demand for favorable goods and services), about 18.87% of women are involved in RNFEA for saving motives. Above all, inadequate farm income for consumption, lack of farm land and declining productivity to purchase property, including agricultural inputs and unexpected expenses, respectively, were the four main reasons that explain women’s engagement and extent of participation in RNFEA. From this, one can observe that rural farm households in the area participated mainly due to the push factor.

Table 7. Reasons for women participation in RNFA.

In actuality, women seek decent job prospects, work outside the home and manage their personal and professional lives simultaneously (Chatterjee & Dwivedi, Citation2023). They often view enterprises as a means of supplementing family income and attempt to value their tacit knowledge. One of the FGD reports from Debreyaqob Kebele stated that

when we face a food shortage, we are very suffering in losing out on feeding our children." This is why they are engaged in the RNFEA. The other option is to leave the house to participate and earn money to help with the family’s food expenses. We can raise our living standards and make some money when we engage in enterprises from home.

Of the 358 sampled women’s, 147 have not participated in RNFEA. Respondents were asked concerning the reasons why they had not participated, and their responses are presented in . Consequently, it is reported that about 95% and 90% of respondent women do not participate in non-farm economic activities due to the social and cultural norms of society, respectively ().

Table 8. Nonparticipation in nonfarm economic activities.

Social norms that negatively impact women’s economic empowerment in the study area include gender-defined duties, taboos, prohibitions and expectations about things like whether or not it’s appropriate for women to manage money, work in certain types of jobs, or be in public places (Mashapure et al., Citation2022). The social system’s socio-cultural norms, which eventually restrict women’s access to development activities, sometimes, favor the isolation and elimination of women (Ahmed, Citation2021). The report is bolstered by prior research demonstrating the detrimental impact of societal norms on women’s economic empowerment levels (Chatterjee & Dwivedi, Citation2023; Kuma & Godana, Citation2023; Dufera et al., Citation2023).

In addition, lack of transport facilities and the long distance to go to the market (59%) contributed to the non-participation of women. Most of the time, women can sell and buy products either by carrying them on their backs or by loading them on donkeys. Modern transport facilities are limited in the small villages of the study area. Thus, it is difficult to engage in RNFEA traditionally due to the unavailability of transport facilities (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). On the other hand, culturally, in the study area, women are not allowed to go far to sell and buy commodities. They have to get permission from their husband to go to the market, and they are expected to come back soon to their home. This discourages women from engaging in non-farm income-generating activities, thereby forcing them to stay at home. On the other hand, Bor and Adan (Citation2023) discovered that households’ proximity to the local towns or markets, as well as those along major roads, makes them more likely to have members who work outside the home. Thus, the long market distance away from home negatively determines women’s participation in RNFEA (Bulkis et al., Citation2023; Alemu et al., Citation2022).

Lack of experience and skill (43.5%), fear of risk-taking (45.5%) and enough agricultural income (26.5%) contribute to the non-participation of women in non-farm economies. Furthermore, a mix of the aforementioned reasons has prevented 22.4% of participants from taking part. The primary barriers to women’s participation in rural, non-farm economies were ignorance and a lack of technical skills (Itunnu & Joseph, Citation2021). In Bangladesh, women’s participation in non-farm activities is also observed to be hampered by a lack of awareness and understanding of entrepreneurial potential (Kuma, 2017). In addition, women choose to be risk-averse and fear taking risks because of the strain of balancing work and family obligations (Mashapure et al., Citation2022).

In rural areas, the environment in the family, society and support system is not conducive to encouraging rural women to take up entrepreneurship as a career due to a lack of awareness and knowledge of entrepreneurial opportunities (Mashapure et al., Citation2022; Kumar, Citation2017). Overall, women are being dragged back into the issues of participation in non-farm economic activities due to socio-cultural problems and a lack of self-confidence that are causing them to live in a broken world. The result is similar to the previous findings (Bor & Adan, Citation2023) who reported that bad infrastructure, negative cultural perception, a weak market and a lack of experience and skills were the main challenges to participation in rural non-farm economies in the Gambella Region of Ethiopia.

When they are asked independently about the cultural factors affecting their decision of non-participation, one female stated that

Cultural factors affect me negatively to participate in RNFA. When my husband comes home at any time, he doesn’t want to miss me. If I am not at home, my husband does not want to eat, which implies that he will not eat if I am not there. He thinks that females are housewives, mothers, and service providers for household activities such as domestic chores, caring for children, cooking foods, etc. This makes me available always at home, and this discourages me from participating in RNFEA even if I need to.

While FGD interviews with the non-participant women in RNFEA about their reasons for non-participating were conducted separately (), the following responses were obtained:

One of the FGD findings reported that

working women outside the home by going a long distance degrade family status. Women’s primary role is traditionally perceived as and expected to be in the house, as a housewife or a mother, and men are supposed to be involved in outside activities, including income generation. In some cases, society considers it a weakness in a man if his wife is working outside. In business, women have to deal with many people, and sometimes they have to travel away from their homes. These are negatively perceived by society.

The other FGD findings reported that:

we have not participated in RNFEA due to socio-cultural norms, the absence of government support for awareness creation and educating the community about the benefits of RNFEA and for building confidence in the community, as well as for providing training and technical support for women entrepreneurs. The combination of all these factors leads to a lack of interest in engaging in RNFEA that hinders our participation.

3.4. Empirical analysis of women participation in RNFEA

A model that has been appropriately fitted to the data is represented by the chi-squared distribution with n–2 degrees of freedom and the test null hypothesis (there is not that much disparity between the fitted and actual values). Consequently, we cannot reject the null hypothesis, which is not significant, as the outcome of the chi-squared distribution is less than its probability value (). With minimal divergence between the fitted and actual values, the model thus fits the data well (Hosmer et al., Citation2013).

Table 9. Logistic model for RNFA participation, goodness-of-fit test.

3.4.1. Linktest

The logit model’s correct specification is checked using Linktest (Chekol, Alimaw, et al., Citation2022). To construct the model, it is necessary to forecast the linear predicted value (-hat) and the linear predicted value squared (-hatsq). If the model is statistically significant with -hat and insignificant with -hatsq, then the model is appropriately stated for this purpose. In line with this, Table 10’s model output shows that two requirements are satisfied: (-hat) is significant and (-hatsq) is not. Because the two requirements are satisfied, the logit model is thus appropriately stated.

3.4.2. Determinants of women’s participation in RNFEA

The dependent variables and determinants of women’s participation in rural nonfarm economic activities (RNFEA) have been estimated in the binary logistic regression model. As a result, the coefficients, marginal effects and robust standard errors are reported in below. Six variables out of twelve have a statistically significant effect on the participation of RNFEA. Among these, variables, such as age, livestock size, land size and land size squared, food shock and distance to the market were found to have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of RNFEA participation.

3.4.2.1. Age

Compared to younger women, older women are less likely to take part in RNFEA. Ceteris paribus; the marginal effect indicated that a one-year increase in a woman’s age reduces the probability of women’s participation in RNFEA by 0.2%. This may have to do with the fact that older women are less likely to participate because of negative social and cultural attitudes. The potential explanation for this is that as women age, their likelihood of actively participating in non-farm economic activities declines, and as they get older, the energy required to do these activities also decreases. Previous research results (Tesgera et al., Citation2023; Dufera et al., Citation2023; Alemu et al., Citation2022) supported this outcome.

3.4.2.2. Marital status

Marital status is marginally related to women’s work chances, but it is connected with a lower probability. This shows that women’s entry into non-farm activities is impacted in the opposite ways by marriage. This has to do with the many roles that women play in the home (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019; Rijkers & Costa, Citation2012). A larger family size is also associated with a decreased chance for women to begin working outside the home because of the fertility theory and the high child dependency ratio. Family size squared, however, positively affects women’s involvement in RNFEA. This is because, as they are frequently in charge of raising the children, women with small children are more likely to look for work outside the home and farm in order to boost household income (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). Similar factors influence women’s transition into non-farm employment, and after they attain a particular educational level, one more year of education helps to reduce their participation. This is because low-skilled workers are needed for the majority of women-owned jobs in rural Ethiopia (Das & Mahanta, Citation2023; Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019).

3.4.2.3. Livestock size

The number of livestock units in Tropical Livestock Units (TLU) and the involvement of women in RNFEA are positively correlated. According to the marginal effect, households with an increase in livestock head have a 0.1% higher chance of having women participate in RNFEA. This might be the case because large livestock households need to earn more money overall in order to fund the initial investments made by female entrepreneurs. The results corroborate the earlier finding (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019) that livestock triggers a shift in employment in Nigeria and Uganda.

3.4.2.4. Land size

Our quantitative findings indicate a non-linear relationship, or inverted U, between women’s participation in RNFEA and household land size. The marginal effect showed that women’s participation in RNFEA increased by 1.9% with early increases in land holding size in hectares, but that this rise peaked at a particular level of land holding size and thereafter fell. This suggests that a 0.4% decrease in women’s involvement in RNFEA was caused by a unit rise in land size after a certain point at which the land size peaks. These also suggest that the likelihood of women participating in RNFEA declines at sufficiently high land-holding levels because wealthier households are less likely to give priority to women engaged in non-farm economic activities. Still, women are more likely to take part in RNFEA until the threshold is crossed. This seemingly counterintuitive result could have as its explanation that increases in household land size are usually associated with the production of substantial agricultural goods and the security of food supply, which frees households from the need to engage in additional income-generating activities. A particular land size must be met by rural households. The outcomes align with the earlier discoveries (Das & Mahanta, Citation2023).

3.4.2.5. Food shock

The coefficient and marginal effects of food shocks are positively and significantly contributing to women’s participation in RNFEA ().

Table 10. Link test for model specification.

Table 11. Estimation of Logic model on the determinants of RNFA participation.

Given the ceteris paribus assumption, the marginal effect shows that women’s experiences of food shocks make them more likely to participate in RNFEA by 93%. A woman with a food shortage in her family is more likely to participate in RNFEA than a woman with no food shortage. The result is consistent with the previous findings that proved that when households are food insecure, their probability of non-farm participation in getting income and ensuring food security is higher (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019; Dzanku, Citation2019; Osarfo et al., Citation2016). Under the entire chain from production, storage, processing, and distribution of food, factors that impact negatively on production, such as drought or climate variability, could all impact negatively on food security (Dzanku, Citation2019). The experience of food shortages in the last 12 months pushes households into non-farm entrepreneurship in times of necessity (Nagler & Naudé, Citation2017). Currently, the Ethiopian economy is declining significantly, from growth to CRS and social unrest (NBE, Citation2022). In this situation, the distribution channels for agricultural inputs and production are closed and sometimes intermittent. Farmers are unable to find access to agricultural inputs at the time of need, and they are unable to produce farm outputs. Rather, they are exposed to food shortages and famine. Despite this, their participation in RNFEA is currently higher in response to the food shortage shocks.

3.4.2.6. Distance to the market

Moreover, distance to the market has a significant and negative effect on RNFA participation decisions (). Ceteris paribus; the marginal effect indicated that with each additional walking hour from homesteads to the nearest market, the probability of women’s participation in RNFEA decreases by 1.4%. If the woman’s residence is far from the market area, it is not convenient for them to go and trade wherever they want because they are responsible for household chores. Due to their greater time and financial constraints than males, women have fewer options for transportation (Van den Broeck & Kilic, Citation2019). Besides, women who travel long distances will be exposed to sexual harassment, and her husband prefers to stop her from participating in RNFEA, so their decision to participate in non-agricultural activities will be broken. Moreover, the other reason is that women lack access to input and output markets as well as market information because they are positioned far from the market. If the market was a long distance from their homestead, they would be unable to obtain the most important market information, such as the price, demand and supply of their output, which would lead to a higher transaction cost and lower profit, and they would stop participating. The result is supported by the previous findings (Dzanku, Citation2019; Dufera et al., Citation2023; Chekol & Mazengia, Citation2022; Chekol, Abetie, et al., Citation2023; Chekol, Giera, et al., Citation2023; Alemu et al., Citation2022; Montanari & Bergh, Citation2019; Adefris & Woldeyohannes, Citation2021).

4. Conclusions and recommendations

Ethiopia is a farming nation where agriculture provides a living for a large portion of the rural community. However, many rural households suffer from chronic poverty and food insecurity due to the persistent risk and uncertainty effects of low agricultural productivity and low farm revenue. Unfortunately, mothers and women are shocked by the food shortage to feed their children and families. This makes rural women participate in non-farm economic activities to generate income and cope with these challenges. In society, women have three roles: reproductive, productive and community participation. Women’s participation in RNFEA can reduce poverty, generate additional income for households and improve their families’ welfare. Thus, the study explored the determinants of women’s participation in RNFEA in the districts of Goncha Siso Enese and Enebsie Sar Midir, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The study was based on survey data collected from 358 randomly chosen women in the four kebeles from the study district. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were employed to analyze the data. The result indicates that about 59% of the respondents are non-participants in RNFEA. The main challenge for non-participating in RNFEA was the negative cultural (95%) and social (90) factors: lack of transport and market infrastructure (59%), lack of experience and skill (43%), fear of taking risks (45%) and a combination of all (26%). In addition, there is a significant difference between participant and non-participant women, with a higher hourly time allocated for domestic work for the non-participants. While the binary logistic regression result indicated that age, land holding size squared, and distance from the market negatively affected participation in RNFEA, the existence of livestock size, land size and food shock had a positive and significant effect. Thus, based on the findings, the following recommendations were made:

The regional and local governments should invest in creating awareness about the benefits of RNFEA for rural communities. Business idea training should be provided for rural women to build their experience and skills and become more involved in it.

In order to guarantee gender equality and combat the detrimental effects of sociocultural influences on society, development agents ought to educate rural communities. This is due to the fact that sociocultural issues pose the biggest barriers to women’s participation in RNFEA. By adding to household income, decreasing poverty and enhancing income equality, as well as by empowering rural women, ensuring gender parity in production and community involvement will ultimately guarantee rural development and a sustainable connection between farm and non-farm businesses.

A huge investment in rural infrastructure such as roads and markets was significantly required to facilitate the linkage and support between farm and non-farm economic activities. Investments in agriculture and non-agricultural sectors are going hand in hand to ensure sustainable rural development. One sector cannot sustainably develop without the development of the other. They are mirror images of each other. The absence of these two basic infrastructures leaves many women in rural areas unable to participate in RNFEA due to the large time required to travel long distances and huge transportation costs to buy and sell inputs and products. This means that many rural households are prone to chronic poverty and food insecurity. Above all, it needs to invest in awareness creation, educate the people about the importance of RNFEA and business idea training, enhance transport and market infrastructure, encourage women’s participation in RNFEA and achieve sustainable rural development.

4.1. Limitation of the study and implication for further research

Policymakers may find the study useful in considering the variables influencing rural women’s participation in non-farm economic activities in rural economies. Women may find the study useful in addressing the issues influencing their desire to participate in RNFEA. To the best of our knowledge, though, this is the first study to examine the variables impacting women’s involvement in RNFEA in rural Ethiopia, where over three-quarters of the rural economies are in poverty and over half the population is female. An issue facing this research is the dearth of statistical information gathered by government organizations regarding women’s participation and women-owned enterprises in the RNFEA. Statistics regarding the factors and degree of rural women’s involvement in non-farm economic activities are not provided by any public authorities. A cross-sectional data set is being used in just two districts for this study. Therefore, in order to draw district and sectoral comparisons on the level of women’s engagement in RNFEA, future research should overcome all of these limitations by examining the factors that influence women’s participation in RNFEA in other districts around the area. Further research ought to investigate the impact of women’s involvement in the RNFEA on their economic empowerment by utilizing panel data sets to scrutinize the evolution of their economic empowerment index over time. Furthermore, women’s participation was the sole binary variable that this study examined. However, future studies should examine the degree to which women participate in RNFA and how that participation affects changes in their household income and food security, both of which should be quantified using metrically scaled variables. In addition, future studies ought to concentrate on the effectiveness of women’s RNFEA participation as well as the extent of government engagement in raising awareness and offering instruction on business advancements for women.

Author contributions

The author of this research developed the research design, collected and analyzed data and drafted the script.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to gratitude all the rural women’s of the study area who gave information for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

Data for this research is available up on a reasonable request of the corresponding author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adefris, Z., & Woldeyohannes, B. (2021). Determinants of participation in non-farm activities among rural farm households in Ambo District of West Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

- Adejo, P. E., Ajibade, Y. E., Adejo, E. G., & Ibrahim, F. A. (2021). Analysis of women participation in non-agricultural income-generating activities in rural communities of Zone B, Kogi State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural and Crop Research, 9(4), 1–17.

- Ahmed, K. O. (2021). The role of female’s participation in economic activity to household income the case of Mizan Aman Town, South Nation Nationality and people’s Region, Ethiopia.

- Alemu, A., Woltamo, T., & Abuto, A. (2022). Determinants of women participation in income generating activities: evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00260-1

- Asfaw, A., Simane, B., Hassen, A., & Bantider, A. (2017). Determinants of non-farm livelihood diversification: evidence from rainfed-dependent smallholder farmers in northcentral Ethiopia (Woleka sub-basin). Development Studies Research, 4(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2017.1413411

- Bor, C., & Adan, A. S. (2023). Rural household’s participation in non-farm activities: The case of the makuey district, Nuer Zone, Gambella Region, Ethiopia. Journal of Agri Socio Economics and Business, 5(02), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.31186/jaseb.5.2.1-12

- Bulkis, S., Nursini, R., Amiruddin, A., Sjarif, D. H., & Yuna, K. (2023). Development strategy of women’s non-farm entrepreneurs group (Small household and handicraft industries) in North Luwu Regency, South Sulawesi. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences, 10(3S), 754–771.

- Chatterjee, B., & Dwivedi, A. (2023). Social inequality in the context of gender: A study of rural West Bengal, India. Global Social Welfare, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-023-00317-3

- Chekol, F. (2019). Education for human capacity building: Achievements and shortcomings in the Ethiopian experience. https://projectng.com/topic/ec20512/education-human-capacity-building-achievements

- Chekol, et al. (2022a). Consumer choice for purchasing imported apparel goods and its effect on perceived saving in Debre Markos District, Amhara Ethiopia: A logistic regression analysis.

- Chekol, F., & Mazengia, T. (2022). Determinants of garlic producers market outlet choices in Goncha Siso Enese District, Northwest Ethiopia: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Advances in Agriculture, 2022, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6719106

- Chekol, F., Abetie, K., & Sirany, T. (2023). Technical efficiency of garlic production under rain fed agriculture in Northwest Ethiopia: Stochastic frontier approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2), 2242177. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2242177

- Chekol, F., Alimaw, Y., Mengist, N., & Tsegaye, A. (2022). Consumer choice for purchasing imported apparel goods and its effect on perceived saving in Debre Markos district, Amhara Ethiopia: A logistic regression analysis. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2140509. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2140509

- Chekol, F., Giera, M., Alemu, B., Dessie, M., Alemayehu, Y., & Ewuinetu, Y. (2023). Rural households’ behaviour towards modern energy technology adoption choices in East Gojjam zone of Ethiopia: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Cogent Engineering, 10(1), 2178107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2023.2178107

- Chekol, F., Tsegaye, A., Mazengia, T., & Hiruy, M. (2022). Small scale biogas technology adoption behaviours of rural households and its effect on major crop yields in East Gojjam Zone of Ethiopia: Propensity score matching approach. Cogent Engineering, 9(1), 2133343. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2022.2133343

- Cramer, J. S. (2003). The origins and development of the logit model. In Logit models from economics and other fields (pp. 149–157). Cambridge University Press.

- Das, K., & Mahanta, A. (2023). Rural non-farm employment diversification in India: the role of gender, education, caste and land ownership. International Journal of Social Economics, 50(6), 741–765. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2022-0429

- Demie, A., & Zeray, N. (2016). Determinants of participation and earnings in the rural nonfarm economy in Eastern Ethiopia. African Journal of Rural Development, 1(1), 61–74.

- Diallo, T. M., Mazu, A. A., Araar, A., & Dieye, A. (2023). Women’s employment in rural Senegal: what can we learn from non-farm diversification strategies? Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 14(1), 102–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-01-2022-0019

- Dufera, W., Bedemo, A., & Kebede, T. (2023). Factors affecting rural women’s participation in non-farm activity in Western Ethiopia: Empirical evidence in Horo Guduru Wollega zone. Journal of Science Technology and Arts Research, 12(3), 94–117.

- Dzanku, F. M. (2019). Food security in rural sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the nexus between gender, geography and off-farm employment. World Development, 113, 26–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.017

- Fan, H., & Xin, B. (2019). Elderly care and rural women’s non-farm employment in China: micro data evidence from China. China Rural Economy, 2, 98–114.

- Hosmer, D. W., Jr, Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. X. (2013). Applied logistic regression (Vol. 398). John Wiley & Sons.

- Itunnu, W. A. F., & Joseph, A. O. (2021). Assessing women’s participation in non-farm activities and its effects on their household income. Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, 10(1), 1.

- Kuma, B., & Godana, A. (2023). Factors affecting rural women economic empowerment in Wolaita Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2), 2235823. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2235823

- Kumar, P. M. (2017). Problems and prospects of the rural women entrepreneurs in India. International Journal of Human Resources and Social Sciences, 4(4), 43–51.

- Loison, S. A. (2015). Rural livelihood diversification in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(9), 1125–1138.

- Mashapure, R., Nyagadza, B., Chikazhe, L., Msipa, N., Ngorora, G. K. P., & Gwiza, A. (2022). Challenges hindering women entrepreneurship sustainability in rural livelihoods: Case of Manicaland province. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2132675. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2132675

- Menelek Asfaw, D. (2022). Woman labor force participation in off-farm activities and its determinants in Afar Regional State, Northeast Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2024675. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2024675

- Mmakola, K. L., & Sithole, S. L. (2023). Women’s agricultural labour and its contribution to women empowerment in the Limpopo province, South Africa. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 6(9), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v6i9.1593

- Montanari, B., & Bergh, S. I. (2019). A gendered analysis of the income generating activities under the Green Morocco Plan: Who profits? Human Ecology, 47(3), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-019-00086-8

- Nagler, P., & Naudé, W. (2017). Non-farm entrepreneurship in rural sub-Saharan Africa: New empirical evidence. Food Policy, 67, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.019

- NBE. (2022). National Bank of Ethiopia, annual report on the Ethiopian economy 2021–2022. https://nbe.gov.et/

- Osarfo, D., Senadza, B., & Nketiah-Amponsah, E. (2016). The impact of nonfarm activities on rural farm household income and food security in the upper east and upper west regions of Ghana.

- Rijkers, B., & Costa, R. (2012). Gender and rural non-farm entrepreneurship. World Development, 40(12), 2411–2426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.017

- Tesgera, W. D., Beyene, A. B., & Wakjira, T. K. (2023). Determinants of rural households’ non-farm participation in West Ethiopia; empirical evidence from Horo Guduru Wollega Zone.

- Thierno, M. D., Mazu, A., Araar, A., & Dieye, A. (2021). Women’s employment in rural Senegal: What can we Learn from non-farm diversification strategies?

- Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2012). Economic development (11th ed.).

- Van den Broeck, G., & Kilic, T. (2019). Dynamics of off-farm employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: A gender perspective. World Development, 119, 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.008

- Yamane, T. (1967). How to calculate a reliable sample size for your research work. https://www.projectclue.com>view-blog