Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) promotes sustained productivity, attention to the environment, and various improvements in its operations. All this to benefit internal and external customers. However, it is difficult to implement a comprehensive version of CSR in workers, who find obstacles to satisfy an optimal balance between productivity and family life. This has motivated the emergence of the concept of Corporate Family Responsibility (CFR), which formalizes the presence of the CSR in the workers, through processes and transformations within the company. This article carries out a diagnosis of the Peruvian situation around CFR, using the theory of institutional pressures, system thinking, and stakeholder theory, to formulate a functional CFR proposal. Its attributes are coincident with the Great Place to Work (GPTW) indicators in the companies with the highest score.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The constitution and development of the family is among the most significant principles in the legal, social, professional, and personal dimensions. It has represented the basic unit of society, and it is constituted as the first group for the formation and protection of moral values (Addiarto et al., Citation2023; Mooney et al., Citation2023; Suero, Citation2023; Viladrich, Citation2018). However, this importance is hardly associated with contemporary working conditions, mainly focused on efficiency and maximization of profit (Ji et al., Citation2024; Pérez-López, Citation2018). This situation is aggravated in countries with a high rate of informal employment (such is the case of Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay, and Peru), which impose more rigid work conditions, low legal protection for licenses recognized by law, and disrespect to several rights, such as the limit of weekly work hours (Berniell et al., Citation2023; Maurizio et al., Citation2023; Romero-Vela et al., Citation2022). This is counterproductive for the company itself, due its workers to lying to obtain permits for family issues, distrust in the institution, and lose company loyalty (Pell & Amigud, Citation2023; Rasheed et al., Citation2022).

This contradiction generated between work and family commitment generates various consequences. First, family life is essential for the development of productive people, with values, and in whose interaction is the base experience for the generation of a collaborative and creative environment (Yang et al., Citation2024; Yesuf et al., Citation2024). This is reflected in the vision of the person as an integral being, with attributes, identity, and emotional resources to face challenging situations (Alcázar, Citation2019; Chinchilla et al., Citation2018; Stiller et al., Citation2023). Second, due to the similarity in the type of responsibility offered to the family and to a job as a collective project, the individuals with the best performance and experience tend to be workers with a family burden (Bosch, Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2022). However, due to job obligations, the care for children often falls on other people, such as relatives or babysitters. This is paradoxical, because professional success collides with family life. It happens especially in companies that require only face-to-face working days, and inflexible schedules, associated with bureaucratic rather than functional criteria (Jia et al., Citation2022; Minh et al., Citation2023). Third, workers place a high value on the balance between family and work. This means that they may be willing to sacrifice better positions to safeguard the care of their relatives. Such is the case of an absolute majority of women who prefer more hours for the family than assuming a manager position (Bertola et al., Citation2023; Chinchilla & Moragas, Citation2018; Yuan et al., Citation2023).

A concept directly linked to this situation is CSR. A practice that links the company with its social, environmental, and human commitment, giving it a role that maintains profits, but dedicates various actions to more transcendent purposes than this one. CSR actions are voluntary and are inspired by an international framework such as the OECD (Jáuregui et al., Citation2019; Oliveira et al., Citation2022; Rodrich-Portugal et al., Citation2023; Spinrad & Relles, Citation2022).

CSR has been developed through a growing literature and practices, which tend to be public actions on society, the environment, and with other companies (Alassuli, Citation2024; Bouncken et al., Citation2023; Liao et al., Citation2024; Sparacino et al., Citation2024). This is significant for corporate reputation, as it helps to strengthen their presence among the vast majority of external stakeholders. However, implementing these strategies comprehensively (both externally and internally) is a complex task. It is especially hard in nations such as Peru, with a majority of companies in informal conditions, little knowledge of CSR, and a tendency to assimilate biases around the concept (Amicarelli & Bux, Citation2023; CCL., Citation2023; Congreso de la República, Citation2023a). That is periodic and organized strategies, far from plain philanthropy (Chenavaz et al., Citation2023; Wu et al., Citation2023). In addition, the benefits corresponding to the balance between work and family, especially for the company, must be socialized (Ramanathan & Isaksson, Citation2022).

The orientation of CSR as an internal strategy has various difficulties in nations such as Peru. Informality, lack of knowledge of its integral meaning, and the immediate sense towards the outside of the company generate the idea that these are only activities to improve one’s own image. Because of that, it is important to highlight the internal side of the CSR. One example of this is the concept of Corporate Family Responsibility (CFR), introduced by Chinchilla and Moragas (Citation2018), which seeks the integration of family and personal needs in the workplace, based on its importance, and in favor of the development of potential workers as integral beings. The CFR is formulated within the CSR, characterizing specific needs and objectives that, otherwise, would be disregarded in the face of social and environmental action. This attention to the family was the subject of research during the Covid-19 pandemic, due the imbalance produced by job insecurity, with a greater incidence in small businesses (Revuelta-López, Citation2022). Finally, similar ideas about the family were analyzed again through Business Ethics (BE), oriented towards the relationships between the worker and the company, and which dimensions are not often highlighted by CSR (Furlotti & Mazza, Citation2022).

For this article, a comprehensive CFR proposal will be developed for the Peruvian territory, through theories and methodologies that are complementary and functional to this context. This is particularly significant, because Peru is a country with high rates of informality, precariousness, and labor inequality (COMEXPERU, Citation2022; Jaramillo, Citation2022). To develop the proposal of CFR, this paper will analyze the lack of legal framework, but also include the institutional pressures theory, the use of system thinking, and the stakeholders theory. Finally, there will be offered examples of good practice in CFR, according to the aforementioned theories.

2. The Peruvian case

This section will analyze the Peruvian case. To that purpose, it will be necessary to review the features around the legal framework, lack of institutional pressures, the transversal use of system thinking and the stakeholders theory.

2.1. Legal framework

Peruvian reality is complex. There is a corresponding legal framework with licenses, rights and protections on working conditions. However, the particularities of the nation make its existence more nominal than applied. Such is the case of the conventions of the International Labor Organization (ILO), ratified by Peru, which detail aspects such as weekly rest (OIT Citation1921), health insurance (OIT Citation1927), paid vacations (OIT Citation1936), protection of maternity (OIT 2000), and regulation of domestic work (OIT 2011). Contemporary legislation highlights the interest in regulating teleworking as an alternative to optimize productivity and the operation of a more flexible model (Congreso de la República, Citation2023b). All of them are viable in a condition of formality and attention to an anthropological paradigm (in which the company functions as an institution that satisfies the needs and initiatives of all its members) (Chtioui et al., Citation2022; Pérez-López, Citation2018). Unfortunately, more than 70% of the Peruvian companies are informal (which is above the Latin American average). That is seen as a reason to evade the legal rights of workers, conditioning situations of labor precariousness (wages below the legal limit, unpaid vacations, lack of work incentives, lack of permits, etc.), and conditioning a situation of concern for performance rather than welfare (COMEXPERU, Citation2022).

This means that it is necessary to promote formal employment, establish strategies that specifically strengthen these needs, and knowledge about the benefits that the CFR has for the company itself (Valdivieso-López, Citation2019). Due to the little incentive to regularize the situation of companies (payment of taxes, excessive regulations, and punitive mechanisms), positive measures are required. That is, benefits are offered to the parties involved, such as tax benefits, better financing conditions, and facilities for obtaining equipment that allows the growth of the (Atienza et al., Citation2023; Simonofski et al., Citation2023). One way to integrate these conditions into companies is to apply institutional pressures. That is, linking the positive actions of a company with its positioning, legal framework and/or participation in groups of a certain prestige. For this reason, it is pertinent to analyze this theory in Peruvian territory.

2.2 Lack of institutional pressures

As previously observed, Peru has a high informality rate. In addition to the ineffectiveness of the legal framework, there is a lack of options to motivate companies to better CFR practices. Informality prevents the existence of a framework of institutional pressures, which could induce good practices in a coercive (laws), regulatory (belonging to a consortium or business group) or mimetic (imitation of other similar companies) way. It makes it more difficult to play a role of innovation or attention for workers’ needs (Latan et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2018). Consequently, a significant majority is in a mechanistic model, in which team members function as tools, under a linear and conservative production scheme, in which each individual is easily replaceable (Ibrahim et al., Citation2023) ().

Table 1. Lack of institutional pressures to comply with labor rights and/or offer welfare.

This lack of institutional pressure prevents it from acting consistently with a CFR. Consequently, it is also difficult to reach a scenario of labor competitiveness and innovation related to it. The company acts are limited on daily profits, in an informal environment, and a situation of uncertainty. This reduces workers’ loyalty to their workplace (Bagdadli et al., Citation2023). It is a structural problem, based on a very difficult scenario. Therefore, this requires systemic strategies, which can address various needs of workers and the company itself.

The strategy to propose implies a detailed review of the dynamic relationships of the organization, as well as those who constitute it (Marino-Jiménez & Ramírez-Rodríguez, Citation2022; Prakash et al., Citation2023). For this reason, it will be used in system thinking, with the support of the stakeholders theory.

2.3. System thinking

Informality and lack of institutional pressures in Peruvian companies also establishes a situation oriented towards the psychology of the worker. The individual will have to assume a change in status, to become a tool to perform their duties without adequate training, and to do everything as possible to achieve the highest possible production. In addition to investing more time and effort at work, there will be less attention to personal and family affairs, and also less loyalty to the company (Amodio & Martinez-Carrasco, Citation2023; Kroflin et al., Citation2023; Nikunlaakso et al., Citation2023). This adds up to at least three factors that produce a negative structural situation: a legal framework with low effectiveness, a lack of regulatory mechanisms, and a worker who has little identification with the workplace. For these reasons, system thinking is proposed. This covers both the form of representation (through archetypes) as well as the construction of alternative solutions. This form of analysis provides attention to the dynamic processes that happen in reactive leadership decisions, which are repetitive in different contexts and business areas.

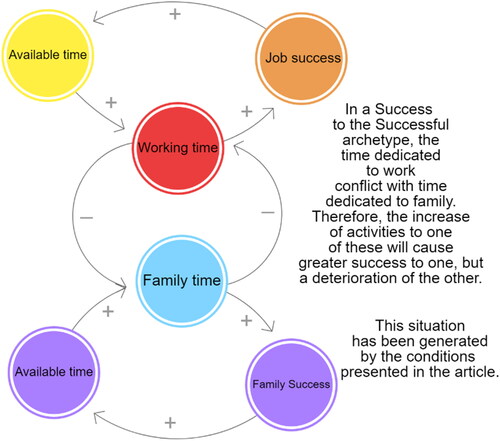

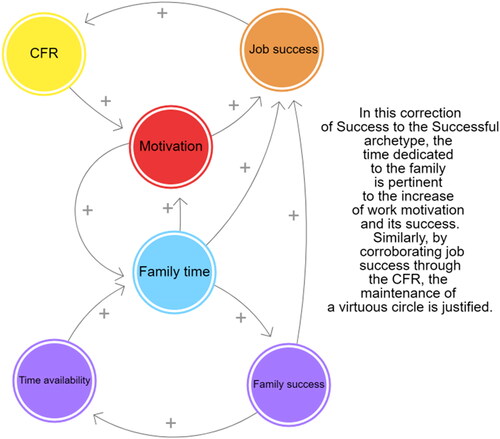

Authors such as Senge (Citation1990, Citation2006) illustrate problematic situations through systemic archetypes. In the case of this paper it will be chosen Success to the Successful. This archetype explains how there is a contradiction between two activities or areas, because there is a set of biased decisions. In this case, job success (greater capacity to generate profits) enters into competition with family success (strengthening of relationships). The time dedicated becomes a variable in conflict, on which (under the context, the punitive organizational culture, and/or the personal condition of the workers) there seems to be no possibility of reconciliation ().

Figure 1. Success to the Successful archetype, elaborated to represent the conflict between time dedicated to work and time dedicated to family.Source: Own elaboration, based on Senge (Citation1990, Citation2006). As stated in the article, the conditions come from a precariousness of working conditions. However, these are visible in the degree of demand, the excessive time, and the low recognition that is maintained in conditions of informal employment.

Senge’s theory of system thinking, seconded by authors such as Arnold and Wade (Citation2015) and Clancy (Citation2018) reveals recurring decisions in organizations, which have an impact on the long-term outlook. Although these are positions in which the workers assume a degree of responsibility for the conservation of their job, the environment developed in this article (with a situation of informality, lack of institutional pressures, and uncovered family) is directly related to this fact. Likewise, it will cause a transactional relationship with the company, oriented to the exchange of work for money. That is not a true identification with the corporate environment.

Archetypes like this are plausible in other studies, which are functional for the representation of situations in different areas. Such is the case of museum administration, educational management, industrial sectors, and even the purpose of the companies nowadays (Marino-Jiménez et al., Citation2021; Prakash et al., Citation2023; Rodrich-Portugal et al., Citation2023). Therefore, its approach is reasonable for understanding different ecosystems, such as the Peruvian case for CFR. However, to find solutions, the functioning of system thinking must be in line with the discipline’s own resources. In this case, the generation of a systemic proposal of CFR in an informal work environment will be previously analyzed with the support of the stakeholders theory.

2.4. Stakeholders theory

Situations such as a mechanistic environment and neglect of the commitment to the family has negative consequences. One of the most important is to negate the principle of being a company led and oriented by human beings. This restricts the initiatives and improvements that can be proposed or implemented beyond the productivity indicators. The stakeholders theory, according to authors such as Cohen (Citation2023), Dacin et al. (Citation2022) and Freeman (Citation2010), are incomplete without this purposeful participation of the workers. For these authors, the ideas of those who work in the company are as important as those produced by managers, owners, customers, rival companies, and the media. For this reason, restricting workers to a dimension of interchangeable parts affects their personal and family life, and also limits the company itself in its different development alternatives.

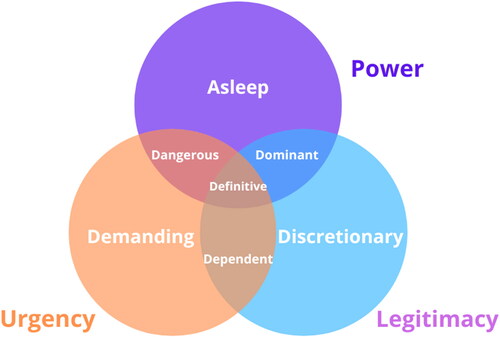

This is related to the model developed by Jáuregui et al. (Citation2019), around the legitimacy and importance of the workers, being at the center of the stakeholders (). The relationship with their family significantly impacts the rest of the dimensions, due it allows them to feel fulfilled in different contexts, helps them to understand the meaning of their activities, and guides them to do actions for the common benefit. For this reason, it is essential to establish actions that facilitate the labor of workers. Such is the case of process automation, the use of resources for better administration, the establishment of ethical rules of conduct in the organization, and collaborative interaction with other companies (Bag et al., Citation2024; Baz & Ruel, Citation2024; Ghanbarpour et al., Citation2023; Salgado-Criado et al., Citation2024).

Figure 2. Stakeholders scheme in which the workers are in balance between power, urgency and legitimacy.Source: Jáuregui et al. (Citation2019). This balance depends on the harmony between different instances. The existence of a worker’s life outside the workplace influences just as it does within the company.

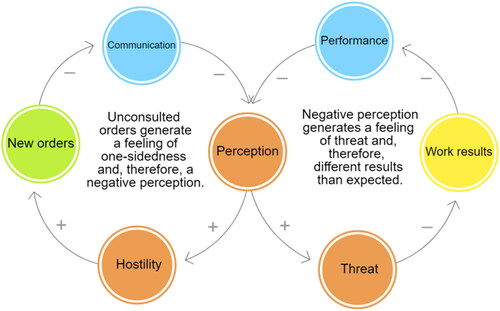

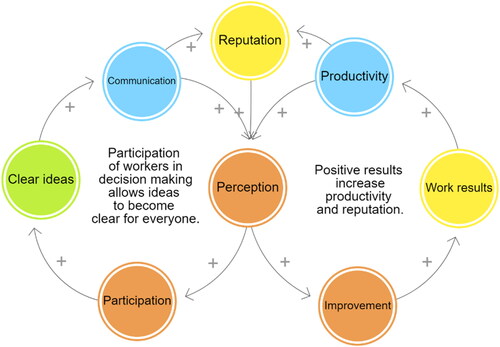

Ignoring the points of view of workers as stakeholders has negative consequences. One of these is the demand for unreasonable goals, generating a climate of mistrust among those who are part of the company. Therefore, work overload or changes in processes are potentially observed as a threat or harassment. This is especially serious if the company works under an informal scheme, and managers make arbitrary decisions. This lack of a transparent two-way communication channel generates a systemic archetype known as Escalate. A situation that results in mutual distrust, due the responses to a doubly negative perception. The workers consider messages and orders from managers as a threat. The managers consider the negative response (low performance or inattention to requests) as indiscipline and lack of respect (Kim, Citation2000; Senge, Citation1990, Citation2006) ().

Figure 3. Escalate archetype, elaborated to represent the consequences of a lack of participation of workers as stakeholders.Source: Own elaboration, based on Senge (Citation1990, Citation2006). Perception is a very important element in organizations. Therefore, distant communication can cause a series of subsequent problems.

All these consequences lead to possible aggravations. Some examples of this are job abandonment, lack of knowledge about the operations of the company, uncertainty in the work environment, decrease of business reputation, lack of good management practices, limitations on the growth of the company, among others. To counteract this fact, it is necessary to assume a broad-spectrum commitment. Such is the case of psycho-corporeal (money, status, productivity, compliance, etc.), cognitive (initiative, creativity, ideas, attention to processes, etc.), and affective (values, identification, service attitude, etc.) factors. These elements respond to characteristics of efficiency, attractiveness, and unity within a company (Amodio & Martinez-Carrasco, Citation2023). To enhance them, it is pertinent to use strategies that respond to both personal and collective needs within the company. Such is the case of the CFR proposal. This alternative will be developed in the next section.

3. CFR proposal

In the previous sections, it has been observed the low correspondence between the CFR and the Peruvian environment. The presence of high informality, lack of institutional pressures, deterioration in relationships between workers and supervisors, as well as the lack of attention to the worker as a stakeholder represent a highly complex challenge. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a relationship of mutual interest. That is better conditions for workers, including care for their families, generating well-being both for them and for the company development.

Workers in a company are the ones who assume all the commitments to generate ideas, serve customers, solve problems, and implement plans (Adnani et al., Citation2023; Alcázar, Citation2018). For this reason, the CFR is essential to achieve a balanced professional experience. It is necessary for well-being in the family life of workers, and their motivated contributions to the company (Chinchilla & Moragas, Citation2018). This implies to know the way in which facts such as the family burden, the degree of responsibility for it, and the difficulties that influence the different facets of the person (Sacre et al., Citation2023). The promotion of a better family life improves skills such as commitment, responsibility and attention to the human sphere of the company itself (González-De-la-Rosa et al., Citation2023; Mousa & Arslan, Citation2023; Venktaramana et al., Citation2023). Finally, the implementation of family support services, such as nurseries, knowledge about family management, and flexible schedules, generate greater opportunities for job access and, consequently, macroeconomic values such as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bosch, Citation2020).

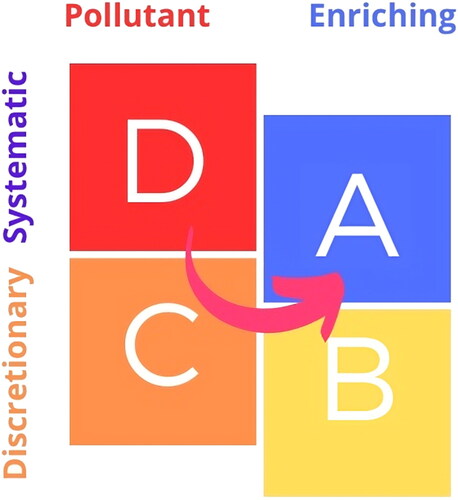

This process is not immediate. The characteristics of an environment such as Peruvian promote the need to establish a reasonable route for the establishment of steps that turn a negative situation into a positive one. Such is the case of the scheme proposed by Chinchilla et al. (Citation2018) for the transformation of a systematically polluting organization to a systematically enriching organization. First, the starting point is level D (systematically polluting organization), which is unrelated to any good practice of conciliation between work, family and personal life. Second, it goes to level C (discreetly polluting organization), in which managers are sensitive to the generation of flexibility guidelines, although these are not necessarily regulated or disseminated. Third, level B (discretionarily enriching organization) recognizes the existence of different spaces for workers (company environment, family, and personal life). Finally, level A (systematically enriching organization) is reached. Finally, a CFR culture is fully assumed. At this point, it is plausible to incorporate measures that integrate the identification of workers’ needs and their formal satisfaction through clearly established policies.

It is pertinent to carry out this route, due it includes a change in the regulations of the companies and the kind of leadership. As previously observed, mechanical environments have the cost of low productivity and high mistrust between supervisors and workers (Pell & Amigud, Citation2023; Rasheed et al., Citation2022). An organization that has developed a D level for a long time will hardly implement the changes in a systematic and enriching way automatically. Awareness-raising policies and processes will be required to establish the required actions and the socialization of the benefits that the CFR can bring to the company (Boskeljon-Horst et al., Citation2023; Farghaly & Abou, Citation2023; Rass et al., Citation2023). The more time with a mechanical style of work, the supervisors will doubt whether it is a nominal change or an authentic transformation (D). So, the policies must capitalize on the management of those who are in line with said initiative (C). This will allow them to take into account the ways in which they have been implemented and generate more appropriate policies for the organizational environment (B). Finally, both due to imitation within the company itself and due to the guarantee of the regulation, this praxis can be generalized (A) ().

Figure 4. Environments of family responsibility.Source: Adapted from Estudio IFREI Study (Citation2018). As with the family as a reflection of society, companies also manage human processes that involve specific actions and also cultural changes.

Consequently, the integration of this process comes from political, facilitative and cultural elements that redound in every CFR model, to constitute a Family Responsible Company (FRE). Regarding the former, associated with rules disseminated throughout the organization are labor flexibility, professional support, family services and extra-salary benefits. Regarding the latter, values such as leadership, communication, responsibility, and strategy are included. Finally, third parties are linked to daily practices, which slow down or drive the development of this strategy. All this is accompanied by a set of results in which the real situation of the organization and the level at which it is found are observed ().

Figure 5. Elements that make up the CFR model.Source: Adapted from Chinchilla (2004). The framework of this strategy is consistent with a series of actions that generate a complex result, since it covers different dimensions.

These conjunctions of elements, and their transformation at the company level, achieve a significant change. In this sense, a situation of conflict is avoided, such as the time dedicated to work and to the family that was observed in , coinciding with the CFR as an enhancer of motivation, time dedicated to family and work success. This kind of practice also generates a situation of greater confidence in the management of measures, in the worker commitment in policies associated with the work environment, and in the development of a business system that is sustainable. Coincidentally, a shift is also generated in the practices of the companies themselves which, in scenarios such as Peru, allow the participation of institutional pressures in mimetic and regulatory aspects. The companies with CFR are imitated, and their presence pushes for better practices (Ibrahim et al., Citation2023; Latan et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2018).

‘Pioneers’ companies provide for the creation of benchmarks to consolidate the CFR as a viable and affordable alternative, around improvements such as incorporation into formality and transparent public competitiveness. This allows the systemic archetype Success to the Successful () to be corrected through the transformation of its weakness into strength. The better functioning of a balanced life between family and work promotes motivation in workers (). Besides, allow the company a positioning due to their institutional reputation.

Figure 6. Correction of the Success to the Successful archetype, elaborated to represent the benefits of the CFR in companies.Source: Own elaboration. The main weakness of the mechanistic scheme becomes a strength when implementing the CFR. This is reflected in the quality of family life, the availability of time, and the motivation to achieve the company’s own objectives.

The archetype presented offers the coincidence of all the effects linked to the CFR. Therefore, initiatives linked to this practice in the business environment allow actions that benefit all parties involved, regardless of whether they are governed by law (Wu et al., Citation2023). For this reason, an intrinsic motivation is generated for the governance of the company. It establishes examples that promote good practices in other entities. This results in recognition by institutions that measure business reputation, the workers themselves and customers (Jing et al., Citation2023; Kim et al., Citation2023).

Unlike what was observed in Escalate archetype (), good practices transcend through the success of the company and positive comments (Rao, Citation2017). The participation of workers in decision-making is supported by stakeholder theory, motivating a participatory climate, which results in greater productivity and reputation ().

Figure 7. Correction of the Escalate archetype.Source: Own elaboration. The use of stakeholder’ theory includes an adequate CFR and participation of the workers in decision making. All of this allows for more transparent communication, in addition to other benefits for the company.

All of these results transcend the idea of a CFR dedicated only to favoring workers. The improvements are transferable to the company under the principle of satisfying the needs of its main stakeholder. The greater connection with their well-being allows a development in productivity and reputation. This idea can be corroborated by the importance that aspects such as the balance between family and work life have for many workers, which will be seen in the following section.

4. Examples of good practices of CFR in Peru

A quality standard that uses coincident criteria with the CFR is the Great Place to Work site (https://www.greatplacetowork.com.pe/) (GPTW, Citation2023). A global company dedicated to helping organizations around the world to transform into great workplaces for their employees. GPTW develops evaluations of the organizational climate and work culture in companies, provides consulting and advice for the improvement of workplaces, offers training, and validates certification for companies interested in obtaining recognition. This kind of standard motivates investment to improve working conditions and (consequently) increase corporate reputation. That is to say, it establishes a positioning process for the attraction of human talent, and the preservation of the best workers. As previously seen, regulatory pressure (from associations) is established, and generates motivation for companies to appear and move up in this ranking (Castro-Martínez & Díaz-Morilla, Citation2019; Mesquita et al., Citation2021 Palencia et al., Citation2022).

GPTW uses a research methodology that is based on the opinion of employees, through a confidential survey that evaluates different aspects such as trust, respect, pride, and camaraderie in the organization. In addition, GPTW also reviews human resources policies and practices, to ensure they are aligned with the organization’s values and culture. Companies that manage to meet the criteria established by GPTW can receive recognition and certifications as ‘Best Places to Work’ in different categories and sectors.

In the Peruvian case, GPTW made three lists for 2023. They recognized companies with more than a thousand workers (C1), those with 251 to a thousand workers (C2) and those with up to 200 employees (C3). That year they asked employees about how flexibility is reflected in the organization they work for. The majority answers were important to find the concordance between their preference and CFR. In the sample presented in , the analysis of the policies of the first five companies most valued by workers of each of the mentioned lists is proposed.

Table 2. CFR policies of companies recognized by GPTW.

The specific points that can be found and summarized in the case analysis are the following:

Time flexibility: variable or hybrid schedules, allowing workers to adjust their work schedules according to their personal and family needs.

Remote work: the possibility of working remotely, either permanently or partially.

Additional benefits: days off, coupons for free hours, licenses, permits, among others, to support the personal and family life of workers.

Professional Development: Training, mentoring, professional and career development for employees.

Well-being and quality of life: incentives and benefits that promote physical, emotional and mental health.

Close and empathetic leadership: Close and empathetic leadership style, which suggests that they value the well-being and satisfaction of their employees.

Active listening and trust: a culture of active listening and trust with the employees; which suggests that they value the opinions and needs of their workers.

In all these cases participation, time flexibility, and professional development are more appreciated than salary. They summarize a vision that recognizes the employees as integral, complete being, and with reciprocity between their work (positive organizational climate), personal characteristics (assessment of ideas, well-being, and clarity about the task), professional experience (continuous training, career lines), and family life (considerations of family commitments). Such is the case of what is proposed by the anthropological paradigm, the CFR, the theory of stakeholders, the representation offered in system thinking, and the institutional pressures associated with the mimetic and the normative. In this sense, the mention of GPTW in this article is consistent with the theories and ideas presented. As one of the standards with the greatest connotation in the world, it also integrates another significant aspect in this proposal: strengthening the relationship between formal companies, corporate reputation, and talent retention. In addition to the benefits for people, companies with good reputation also enjoy higher profits, and growth possibilities (Castilla-Polo & Sánchez-Hernández, Citation2022; Diaz-Sarachaga & Ariza-Montes, Citation2022). In sum, whether through financial support, conversion margin or greater recall, these benefits accompany all the aforementioned positive factors (Cabrera-Luján et al., Citation2023; Hsu & Liao, Citation2023; Ma, Citation2023).

This incorporation of the CFR in favor of organizations is widely supported in the literature. However, its real impact is seen in cases like those presented. The knowledge and application of its benefits by those that govern the companies would allow important growth in contexts such as the Peruvian one. The lack of formality, effective institutional pressures and arbitrary management can be overcome through adequate incorporation of the CFR, as well as sustainable strategies such as those presented in this work.

5. Conclusions

The incorporation and development of a CFR implies the establishment of a valuable component for CSR. It has a corresponding action with the inner development of the person. It is also in line with the theory of the stakeholders, the development of system thinking for better decision-making, and the institutional pressures in the mimetic and normative dimensions. In this sense, it adds to the integration of an anthropological model, which promotes the welfare of the workers, and optimizes their contributions for better productivity, commitment, and ideas. By providing a space of trust, the company benefits from its work teams. These actions also improve their reputation and their access to other benefits, such as those achieved by leading companies in different fields and sizes. For this reason, the management of a rational and productive vision is significant, both in the Peruvian territory and other similar spaces.

When analyzing complex territories, such as the Peruvian nation, there is a need to incorporate initiatives that come from the private sector, and transmit these possibilities to pending tasks for the public sector (better laws, formalization, CSR, etc.). It implies a kind of model which can be evidenced through the success stories already mentioned, and developed through research such as this one. Such is the case of the positioning of leading corporations, with workers identified with them, and with the conditions to innovate within their own environment. That is a shared leadership model, with perspective and driven towards greater goals, and social development. Finally, actions linked to the CFR strengthen a transparent relationship within the organization. This provides the combination of real improvements in each of the available instances through their real experience. Although the starting point of these actions seems to be for the well-being of the workers, this effect can be extrapolated to the whole organization.

Authors contributions

All the authors participated in the following actions:

Mauro Marino-Jiménez: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

Final approval of the version to be published.

All of the authors participated in the formation of the research, taking corporate social responsibility as a starting point.

In addition to this, they contributed with the use of search criteria and strategies to reinforce the statements.

Guillermo Mayurí-Aguilar: Drafting the work or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content.

On the other hand, they discussed how to interpret the information to form the most appropriate archetype, according to the theory of system thinking.

Eduardo Venegas-Villanueva: Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Finally, the authors participated in the revision of the manuscript, with the purpose of improving the writing and expanding the concepts.

Ethical approval

No human participants were required to carry out this study. Additionally, in accordance with the institution’s policies, this kind of work does not require approval from an ethics committee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study as it is a qualitative proposal.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addiarto, W., Narsih, U., & Taufiq, A. (2023). Identifying Family Effort Factors in Preventing Covid-19 Transmission in Rural Areas. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2634(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0113114

- Adnani, L., Jusuf, E., Alamsyah, K., & Jamaludin, M. (2023). The role of innovation and information sharing in supply chain management and business performance of halal products in tourism destinations. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 11(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2022.10.007

- Alassuli, A. (2024). The role of environmental accounting in enhancing corporate social responsibility of industrial companies listed on the Amman Stock Exchange. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 12(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2023.10.012

- Alcázar, M. (2018). Cómo Mandar Bien: Consejos para ser un buen jefe. 3rd ed. Infobrax. https://www.manoloalcazar.com/libro/como-mandar-bien-consejos-para-ser-un-buen-jefe/

- Alcázar, M. (2019). Persona. Mag. https://www.manoloalcazar.com/libro/persona/

- Amicarelli, V., & Bux, C. (2023). Users’ perception of the circular economy monitoring indicators as proposed by the UNI/TS 11820:2022: Evi-dence from an exploratory survey. Environments, 10(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10040065

- Amodio, F., & Martinez-Carrasco, M. (2023). Workplace incentives and organizational learning. Journal of Labor Economics, 41(2), 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1086/719686

- Arnold, R., & Wade, J. (2015). A definition of systems thinking: a systems approach. Procedia Computer Science, 44(44), 669–678. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877050915002860 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.050

- Atienza, M., Scholvin, S., Irarrazaval, F., & Arias-Loyola, M. (2023). Formalization beyond legalization: ENAMI and the promotion of small-scale mining in Chile. Journal of Rural Studies, 98(98), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.02.004

- Bag, S., Srivastava, G., Gupta, S., Sivarajah, U., & Wilmot, N. V. (2024). The effect of corporate ethical responsibility on social and environmental performance: An empirical study. Industrial Marketing Management, 117(117), 356–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2024.01.016

- Bagdadli, S., Gianecchini, M., Castro Christiansen, L., Biron, M., Budhwar, P., & Harney, B. (2023). Italy: Human resource management in Italian family-owned SMEs: Sustaining the competitive advantage through B corp transformation. In L. Castro-Christiansen, M. Biron, P. Budhwar, & B. Harney (Eds.), The Global Human Resource Management Casebook (pp. 169–176). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003307099-22

- Baz, J. E., & Ruel, S. (2024). Achieving social performance through digitalization and supply chain resilience in the COVID-19 disruption era: An empirical examination based on a stakeholder dynamic capabilities view. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 201(201), 123209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123209

- Berniell, I., Berniell, L., De La Mata, D., Edo, M., & Marchionni, M. (2023). Motherhood and flexible jobs: Evidence from Latin American countries. World Development, 167(167), 106225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106225

- Bertola, L., Colombo, L., Fedi, A., & Martini, M. (2023). Are work–life policies fair for a woman’s career? An Italian qualitative study of the backlash phenomenon. Gender in Management, 38(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2021-0366

- Bosch, M. J.. (2020). El nuevo trabajador ideal. La Tercera. https://www.latercera.com/opinion/noticia/el-nuevo-trabajador-ideal/SNJJFKELPFB5TCQXTRCGADDCAQ/

- Boskeljon-Horst, L., Snoek, A., & Van Baarle, E. (2023). Learning from the complexities of fostering a restorative just culture in practice within the Royal Netherlands Air Force. Safety Science, 161(161), 106074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106074

- Bouncken, R. B., Kumar, A., Connell, J., Bhattacharyya, A., & He, K. (2023). Coopetition for corporate responsibility and sustainability: Does it influence firm performance? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(1), 128–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-05-2023-0556

- Cabrera-Luján, S., Sánchez-Lima, D., Guevara-Flores, S., Millones-Liza, D., García-Salirrosas, E., & Villar-Guevara, M. (2023). Impact of corporate social responsibility, business ethics and corporate reputation on the retention of users of third-sector institutions. Sustainability, 15(3), 1781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031781

- Castilla-Polo, F., & Sánchez-Hernández, M. (2022). International orientation: An antecedent-consequence model in Spanish agri-food cooperatives which are aware of the circular economy. Journal of Business Research, 152(152), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.038

- Castro-Martínez, A., & Díaz-Morilla, P. (2019). Analysis of the great place to work and the internal communication observatory awards: Internal communication practices in Spanish companies (2014–2018). El Profesional de la Información, 28(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.sep.18

- CCL. (2023). Informalidad en negocios creció 7,9% en 2022, la tasa más alta en los últimos 8 años. La Cámara. https://lacamara.pe/ccl-informalidad-en-negocios-crecio-79-en-2022-la-tasa-mas-alta-en-ultimos-8-anos/

- Chenavaz, R., Couston, A., Heichelbech, S., Pignatel, I., & Dimitrov, S. (2023). corporate social responsibility and entrepreneurial ventures: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Sustainability, 15(11), 8849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118849

- Chinchilla, N., & Moragas, M. (2018). Dueños de nuestro destino. Cómo conciliar la vida profesional, familiar y personal. (4th ed.). Ariel. https://www.casadellibro.com/libro-duenos-de-nuestro-destino/9788434427761/6395950

- Chinchilla, N., Jiménez, E., & Lombardía, P. G. (2018). Integrar la vida: liderar con éxito la trayectoria profesional y personal en un mundo global. (7th ed.). Ariel. https://www.marcialpons.es/media/pdf/9788434433311.pdf

- Chtioui, R., Berraies, S., & Dhaou, A. B. (2022). Perceived corporate social responsibility and knowledge sharing: mediating roles of employees’ eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(3), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-11-2021-0498

- Clancy, T. (2018). Systems thinking: Three system archetypes every manager should know. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 46(2), 32–41. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8404057 https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2018.2844377

- Cohen, M. A. (2023). Reconstructing the moral logic of the stakeholder approach, and reconsidering the participation requirement. Philosophy of Management, 22(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-022-00227-y

- COMEXPERU. (2022). Informalidad laboral peruana continúa al alza: ¿Cómo nos posicionamos en la Región? Sociedad De Comercio Exterior Del Perú. https://www.comexperu.org.pe/articulo/informalidad-laboral-peruana-continua-al-alza-como-nos-posicionamos-en-la-region

- Congreso de la República. (2023a). Leyes y proyectos de ley referidos a la responsabilidad social empresarial y responsabilidad social corporativa. https://www.congreso.gob.pe/Docs/DGP/DIDP/files/nir_5_leyes_y_proyectos_de_ley_referidos_a_responsabilidad_social_empresarial_y_responsabilidad_social_corporativa.pdf

- Congreso de la República. (2023b). Ley del teletrabajo. https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ley-del-teletrabajo-ley-n-31572-2104305-1/

- Dacin, M., Harrison, J., Hess, D., Killian, S., & Roloff, J. (2022). Business versus ethics? Thoughts on the future of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(3), 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05241-8

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J. M., & Ariza-Montes, A. (2022). The role of social entrepreneurship in the attainment of the sustainable development goals. Journal of Business Research, 152(152), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.061

- Estudio IFREI. (2018). Responsabilidad Familiar Corporativa. https://media.iese.edu/research/pdfs/IND-160.pdf

- Farghaly, S., & Abou, M. (2023). The relationship between toxic leadership and organizational performance: the mediating effect of nurses’ silence. BMC Nursing, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01167-8

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Furlotti, K., & Mazza, T. (2022). Corporate social responsibility versus business ethics: analysis of employee-related policies. Social Responsibility Journal, 20(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2022-0232

- Ghanbarpour, T., Crosby, L. A., Johnson, M. D., & Gustafsson, A. (2023). The influence of corporate social responsibility on stakeholders in different business contexts. Journal of Service Research, 27(1), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/10946705231207992

- González-De-la-Rosa, M., Armas-Cruz, Y., Dorta-Afonso, D., & García-Rodríguez, F. J. (2023). The impact of employee-oriented CSR on quality of life: Evidence from the hospitality industry. Tourism Management, 97(97), 104740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104740

- GPTW. (2023). Great place to work. https://www.greatplacetowork.com.pe

- Hsu, A., & Liao, C. (2023). Auditor industry specialization and real earnings management. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 60(2), 607–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01106-3

- Ibrahim, M., Kimbu, A., & Ribeiro, M. (2023). Recontextualising the determinants of external CSR in the services industry: A cross-cultural study. Tourism Management, 95(95), 104690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104690

- Jaramillo, M. (2022). El mercado laboral en Perú 2022: la misma senda. Instituto Peruano de Economía. https://www.ipe.org.pe/portal/el-mercado-laboral-en-2022-en-la-misma-senda-por-miguel-jaramillo/

- Jáuregui, K., Ventura, J., & Gallardo, J. (2019). Responsabilidad social y sostenibilidad empresarial. Fundamentos, gestión y perspectivas. Editorial Pearson.

- Ji, X., Li, X., & Wang, S. (2024). Balance between profit and fairness: Regulation of online food delivery (OFD) platforms. International Journal of Production Economics, 269(269), 109144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2024.109144

- Jia, C., Long, Y., Luo, X., Li, X., Zuo, W., & Wu, Y. (2022). Inverted U-shaped relationship between education and family health: The urban-rural gap in Chinese dual society. Front. Frontiers in Public Health, 10(10), 1071245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1071245

- Jing, J., Wang, J., & Hu, Z. (2023). Has corporate involvement in government-initiated corporate social responsibility activities increased corporate value?—Evidence from China’s targeted poverty alleviation. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01869-7

- Kim, D. (2000). System archetypes I. Diagnosing systemic issues and designing high-leverage interventions. Pegasus Communications I.N.C. https://thesystemsthinker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Systems-Archetypes-I-TRSA01_pk.pdf

- Kim, Y., Hur, W., & Lee, L. (2023). Understanding customer participation in CSR activities: The impact of perceptions of CSR, affective commitment, brand equity, and corporate reputation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75(75), 103436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103436

- Kroflin, K., Utrilla, M. G., Moore, M. R., & Lomazzi, M. (2023). Protecting the healthcare workers in low- and lower-middle-income countries through vaccination: Barriers, leverages, and next steps. Global Health Action, 16(1), 2239031. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2023.2239031

- Latan, H., Chiappetta, C., Lopes, A., Fosso, S., & Shahbaz, M. (2018). Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 180(180), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.106

- Liao, F., Hu, Y., & Ye, S. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and green supply chain efficiency: conditioning effects based on CEO narcissism. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02237-1

- Liu, A., Manchiraju, S., Beutell, N. J., Gopalan, N., Middlemiss, W., Srivastava, S., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2022). Regulatory focus, family–work Interface, and adult life success. Journal of Adult Development, 30(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09423-6

- Ma, L. (2023). Corporate social responsibility reporting in family firms: Evidence from China. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 37(37), 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2022.100730

- Marino-Jiménez, M., & Ramírez-Rodríguez, L. (2022). Análisis sistémico de la educación a distancia escolar peruana en el entorno de la COVID-19. American Journal of Distance Education, 36(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2073745

- Marino-Jiménez, M., Rojas-Noa, F., & Morán-Ramos, D. (2021). Andean cultural heritage: a systemic analysis of peruvian museums for their representation, preservation, dissemination and sustainability. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage, 21(21), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.48255/1973-9494.JCSCH.21.2021.07

- Maurizio, R., Monsalvo, A. P., Catania, M. S., & Martinez, S. (2023). Short-term labour transitions and informality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America. Journal for Labour Market Research, 57(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-023-00342-x

- Mesquita, A., Oliveira, A., Oliveira, L., Sequeira, A., & Silva, P. (2021). Perspectives of companies and employees from the great place to work (GPTW) ranking on remote work in Portugal: A methodological proposal. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 1366(1366), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72651-5_4

- Minh, A., McLeod, C., Reijneveld, S., Veldman, K., van Zon, S., & Bültmann, U. (2023). The role of low educational attainment on the pathway from adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems to early adult labour market disconnection in the Dutch TRAILS cohort. SSM - Population Health, 21(21), 101300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101300

- Mooney, K. E., Bywater, T., Dickerson, J., Richardson, G., Hou, B., Wright, J., & Blower, S. (2023). Protocol for the effectiveness evaluation of an antenatal, Universally offered, and remotely delivered parenting programme ‘Baby Steps’ on maternal outcomes: A Born in Bradford’s Better Start (BiBBS) study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15111-1

- Mousa, M., & Arslan, A. (2023). To what extent does virtual learning promote the implementation of responsible management education? A study of management educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100772

- Nikunlaakso, R., Reuna, K., Oksanen, T., & Laitinen, J. (2023). Associations between accumulating job stressors, workplace social capital, and psychological distress on work-unit level: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1559. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16506-w

- Oliveira, M., Proença, T., & Ferreira, M. (2022). Do corporate volunteering programs and perceptions of corporate morality impact perceived employer attractiveness? Social Responsibility Journal, 18(7), 1229–1250. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-03-2021-0109

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo [OIT. (2000). C183 – Convenio sobre la protección de la maternidad, 1–4. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312328:NO

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo [OIT]. (1921). C014 – Convenio sobre el descanso semanal (industria), 1–5. Ginebra. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312159

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo [OIT]. (1927). C024 – Convenio sobre el seguro de enfermedad (industria), 1–6 https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312169:NO

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo [OIT]. (1936). C052 – Convenio sobre las vacaciones pagadas, 1–3. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312197:NO

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo. (2011). C189 – Convenio sobre las trabajadoras y los trabajadores domésticos, 1–6. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:2551460:NO

- Palencia, D. A. B., Rodriguez-Fuentes, D. E., Muñoz, J. C. M., León-Castro, E., Molina, R. R., & Alvarez-Gomez, A. J. (2022). Using ordered weighted average operators in the great place to work scale. Procedia Computer Science, 210(210), 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.10.169

- Pell, D., & Amigud, A. (2023). The higher education dilemma: The views of faculty on integrity, organizational culture, and duty of fidelity. Journal of Academic Ethics, 21(1), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-022-09445-5

- Pérez-López, J. A. (2018). Fundamentos de la dirección de empresas. (7th ed.). Rialp. https://www.rialp.com/libro/fundamentos-de-la-direccion-de-empresas_91752/

- Prakash, S., Kirkham, R., Nanda, A., & Coleman, S. (2023). Exploring the complexity of highways infrastructure programmes in the United Kingdom through systems thinking. Project Leadership and Society, 4(4), 100081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2023.100081

- Ramanathan, S., & Isaksson, R. (2022). Sustainability reporting as a 21st century problem statement: using a quality lens to understand and analyse the challenges. The TQM Journal, 35(5), 1310–1328. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-01-2022-0035

- Rao, M. S. (2017). Employees first, customers second and shareholders third? Towards a modern HR philosophy. Human Resource Management International Digest, 25(6), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-02-2017-0023

- Rasheed, M. A., Hussain, A., Hashwani, A., Kedzierski, J., & Hasan, B. (2022). Implementation evaluation of a leadership development intervention for improved family experience in a private pediatric care hospital, Pakistan. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 944. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08342-2

- Rass, L., Treur, J., Kucharska, W., & Wiewiora, A. (2023). Adaptive dynamical systems modelling of transformational organizational change with focus on organizational culture and organizational learning. Cognitive Systems Research, 79(79), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2023.01.004

- Revuelta-López, M. D. (2022). The pandemic driving socially responsible Work-Family performance in the transportation sector. In A. M., López-Fernández & A. Terán-Bustamante (Eds.), Palgrave studies in democracy, innovation, and entrepreneurship for growth (pp. 223–240). London Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91532-2_12

- Rodrich-Portugal, R., Marino-Jiménez, M., Mayurí-Aguilar, G., & Abad-Neyra, S. (2023). The purpose of the company beyond its position in the market: The new agent of social development. Business Strategy & Development, 6(4), 931–941. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.288

- Romero-Vela, S. L., Pinto, G., Medina, J. L. F., & Tito, L. P. D. (2022). Gestión de seguridad laboral en organizaciones públicas del Perú. Revista Venezolana De Gerencia, 27(99), 1126–1139. https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.27.99.17

- Sacre, H., Haddad, C., Hajj, A., Zeenny, R. M., Akel, M., & Salameh, P. (2023). Development and validation of the socioeconomic status composite scale (SES-C). BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1619. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16531-9

- Salgado-Criado, J., Mataix-Aldeanueva, C., Nardini, S., López-Pablos, C., Balestrini, M., & Rosales-Torres, C. S. (2024). How should we govern digital innovation? A venture capital perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 200(200), 123198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123198

- Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency Doubleday. https://search.worldcat.org/es/title/21226996

- Senge, P. (2006). La quinta disciplina en la práctica. Granica. https://clea.edu.mx/biblioteca/files/original/94ce0359b5ac5efaccca3a941d41d396.pdf

- Simonofski, A., Handekyn, P., Vandennieuwenborg, C., Wautelet, Y., & Snoeck, M. (2023). Smart mobility projects: Towards the formalization of a policy-making lifecycle. Land Use Policy, 125(125), 106474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106474

- Sparacino, A., Merlino, V. M., Brun, F., Danielle, B., Blanc, S., & Stefano, M. (2024). Corporate Social Responsibility communication from multinational chocolate companies. Sustainable Futures, 7(7), 100151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2024.100151

- Spinrad, M., & Relles, S. (2022). Losing our faculties: Contingent faculty in the corporate academy. Innovative Higher Education, 47(5), 837–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09602-z

- Stiller, M., Ebener, M., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2023). Job quality continuity and change in later working life and the mediating role of mental and physical health on employment participation. Journal for Labour Market Research, 57(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-023-00339-6

- Suero, C. (2023). Gendered division of housework and childcare and women’s intention to have a second child in Spain. Genus, 79(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-023-00182-0

- Valdivieso-López, E. (2019). La responsabilidad familiar empresarial en la gestión de empresas. Paradigmas y perspectiva jurídica. IUS: Revista De Investigación De La Facultad De Derecho, 8(2), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.35383/ius.v1i2.279

- Venktaramana, V., Ong, Y., Yeo, J., Pisupati, A., & Krishna, L. (2023). Understanding mentoring relationships between mentees, peer and senior mentors. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04021-w

- Viladrich, P. J. (2018). Antropología del amor. Universidad de Piura. https://www.udep.edu.pe/icf/publicaciones/antropologia-del-amor/

- Wang, S., Wang, H., & Wang, J. (2018). Exploring the effects of institutional pressures on the implementation of environmental management accounting: Do top management support and perceived benefit work? Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2252

- Wu, C., Cheng, F., & Sheh, D. (2023). Exploring the factors affecting the implementation of corporate social responsibility from a strategic perspective. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01664-4

- Yang, H., Zhao, X., & Ma, E. (2024). A dual-path model of work-family conflict and hospitality employees’ job and life satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 58(58), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.12.008

- Yesuf, Y. M., Getahun, D. A., & Debas, A. T. (2024). Determinants of employees’ creativity: modeling the mediating role of organizational motivation to innovate. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-024-00364-w

- Yuan, L., Li, Y., Yan, H., Xiao, C., Liu, D., Liu, X., Guan, Y., & Yu, B. (2023). Effects of work-family conflict and anxiety in the relationship between work-related stress and job burnout in Chinese female nurses: A chained mediation modeling analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 324(324), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.112