Abstract

This study explored the Norwegian media’s coverage (2015-2022) of the discovery of the wreck of a slave ship in 1974 and how this coverage related to contemporary antiracist issues such as Black Lives Matter, the Rhodes Must Fall movement, and the murder of George Floyd. A content analysis was applied to 16 of a total of 24 newspaper articles (online and print versions) informed by critical discourse analysis and tenets of critical race theory. Findings indicate that the overarching objective appears to be documenting the facticity of the Danish-Norwegian slave trade, with a particular focus on the significant role played by Norwegians. The journalists assume the role of archaeologists in making a historical inventory of this epoch. It is argued that, while the above is laudable given the miasma of ignorance surrounding the role of Norwegians in the slave trade, the coverage fails to take cognizance of the over 11% of black and brown Norwegians of African and Asian extraction in whose eyes Norwegian culpability in the slave trade is treated as an isolated compartmentalized historical event dislocated from contemporary antiracist struggles and the racial microaggressions of the everyday that are left unaddressed.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

In a study conducted by the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth, and Family Affairs (Bufdir, Citation2021), the results make for disconcerting reading in a country that prides itself on an egalitarian and ‘color-blind’ ethos unsullied by the evils of slavery and colonialism: ‘In the non-immigrant population, 20 percent have experienced discrimination. Among immigrants, the corresponding figure is 39 percent, and among Norwegians born to immigrant backgrounds, 47 percent’ (Bufdir, Citation2021). Of particular concern is the fact that children born to immigrant parents, born and bred in Norway, report experiencing more racism than their parents. The report goes on to state, ‘The most common grounds for discrimination among both immigrants and Norwegian-born immigrant parents are ethnic background, skin color, and religion or belief’ (Bufdir, Citation2021).

Given the above, this study asks the question: How did Norwegian media (2015–2022) cover the discovery of the wreck of the slave ship Fredensborg off the coast of southern Norway in 1974, and how does this feed into contemporary antiracist struggles? The slave ship, although discovered in 1974, appears to have garnered little attention. However, the alignment of a litany of global events (Black Lives Matter, the murder of George Floyd, and the Rhodes Must Fall movement) that coincided with a Norwegian film documentary about Norway’s ‘hidden’ slave trade and colonial history catapulted the role of Norway and Norwegians in the Danish-Norwegian slave trade to national headline news. Thanks to preserved records, diving finds, and excavations, the slave ship Fredensborg is considered the best documented slave ship recovered as a wreck (Agderposten, 2018). The daily records from the ship are preserved in the National Archives in Copenhagen and have recently been made available in digital format. ‘Between 1670 and 1804, 110,000 enslaved people were transported from Africa to the Americas [Danish West Indies (Saint Thomas, Saint Croix, and Saint John)] on ships belonging to the Danish-Norwegian kingdom’, according to the newspaper Agderposten, the main paper in Agder county in southern Norway where the wreck was found.

Scholars often lament the obfuscation and veiled role played by the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway as a major slave trading nation. For the purposes of this paper, the Kingdom or Union of Denmark-Norway—sometimes referred to as the Oldenburg Monarchy—included the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway, the German territories of the Duchy of Schleswig, and the Duchy of Holstein. The scholar Daniel Hopkins states, ‘It is not commonly known that Denmark ever had any part in the history of Africa’, even though ‘the Danes sailed the same seas, traded in the same commodities, and entertained much the same imperial ambitions as the Spanish, the Portuguese, the British, and the Dutch’ (Hopkins, Citation2013, p.1). Norway was one of eleven European countries threatened with litigation in 2013 by fifteen Caribbean countries for its role in the transatlantic slavery (Brooks, Citation2014). In his Harvard study, Scott Stawski (Citation2018) refutes the extant numbers on the Danish-Union slave trade and computes a figure that is six times higher.

Utilizing primary data only recently available, this analysis indicates that Denmark was integral to the embarkation or disembarkation of more than 600,000 African slaves to the Americas from 1671 until 1825, making Denmark not the 7th but the 5th largest slave-trading nation, only surpassed by Portugal, Great Britain, and France (Stawski, Citation2018, p. 2).

Despite recent scholarship corroborating Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, the former Prime Minister of Norway and current NATO chief, Jens Stoltenberg, stated, ‘The reason why Norway has such a good reputation out in the world is that we have no colonial past’ (Klassekampen, 2018). It is argued that this incompatible ‘clash of narratives’ about the Norwegian transatlantic slave trade will have repercussions for the over 11% of non-white Norwegians who would share some affinity with their ancestral counterparts. The media coverage, then, becomes the lightning rod through which non-white Norwegians would be either told that the white somatotype and its version that sanitizes a history of culpability is the norm or, alternatively, that their new homeland will grapple seriously with the unsavoury past of slavery.

Speaking of the almost unassailable classic novel, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe, considered it ‘one which parades in the most vulgar prejudices and insults from which a section of mankind has suffered untold agonies and atrocities in the past… a story in which the very humanity of black people is called into question’ (Achebe, Citation1977, p. 1791). At the heart of the matter is the question of the ‘gaze’ – who tells our story? (Thomas, Citation2016). Leaving it to others is a risky venture, as centuries of writing have shown. Sir Hillary Beckles, the historian who led the Caribbean Community Reparations Commission, gave expression to the above when he articulated the rationale behind the threat of litigation against Norway and 10 other countries for their roles in the transatlantic slave trade.

For over 400 years, Africans were classified by law as non-human, chattel, property, and real estate. This history has inflicted massive psychological damage on African descendants. Only a reparatory dialogue can begin the process of healing and repair (The Local, Citation2013).

Building upon our findings, we will later suggest some measures for the enhancement of history education. These measures encompass a range of strategies, including curriculum development, research support, integration with contemporary issues, collaboration with international institutions, utilization of primary sources and diverse perspectives, incorporation of guest speakers and interactive teaching methods, organization of educational field trips, provision of professional development opportunities for educators, and development of digital resources.

Methodology

Content analysis

Hansen and Machin (Citation2019, p. 89) state that ‘the aim of content analysis in media research has more often been that of examining how news, drama, advertising, and entertainment output reflects social and cultural issues, values, and phenomena’. Holsti (Citation1969, p. 14) defines content analysis as ‘any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages’. Berelson (Citation1952) was concerned with the ‘manifest content of communication’, while Bryman (Citation2004) adds ‘replicability’ as an important aspect of content analysis. All translations from Norwegian to English are the authors’. The following keywords were entered into the media archive company, Retriever Research (2022): Danish-Norwegian, slave trade, slave ship, and Arendal (city in Agder country, southeastern Norway, where the slave shipwreck was discovered). Retriever Research is the largest media archive in the Nordics, featuring news from print and digital editorial media as well as radio and television.

Hansen and Machin (Citation2019, p. 93) eight consecutive steps in the process of content analysis served as a template for conducting this study: (1) define the research problem; (2) review the relevant literature; (3) select media and sample (4) define analytical categories; (5) construct a coding schedule and protocol; (6) pilot the coding schedule and check reliability; (7) prepare data and analyze (8) report findings and conclusions. Of pertinence is Hansen and Machin (Citation2019, p. 93) argument that content analysis is contingent upon a clear ‘theoretical framework, which would include a clear conceptualization of the nature and social context of the type of communications content that is to be examined’. This study was guided by critical discourse analysis (see next segment) as both a method and a theory augmenting content analysis.

In regard to the selection of media and sample (point 3), the selection was delineated to the time period 2015–2022, which coincides with global movements such as the Black Lives Matter, Rhodes Must Fall movement, and the murder of George Floyd. Nine sources (with a print and online presence) turned up 24 hits, of which 16 were analyzed (see ). The aim was to explore connections and interpretations. Where is the gaze of the media? Is the stigma of slavery transformed into a discourse of empowerment for the more than 11% of contemporary Norwegians with black and brown pigmentation? Coding was done on a sentential level with four colors representing four emerging themes: (a) the framing lenses; (b) historical focus or contemporary focus; (c) portrayal of slaves; and (d) lessons for the present. ‘It is perfectly feasible—and indeed often desirable—to take a partially inductive approach and to simply add new values to a variable’ (Hansen & Machin, Citation2019, p. 109). Having identified these categories inductively, a content analysis protocol was created with instructions about how the coding is to be conducted with a view towards greater inter-coder reliability (Bryman, Citation2004). Two other colleagues assigned codes inductively to the 16 articles selected with an inter-coder reliability percentage of ca. 80%.

Table 1. Overview of media sources.

Critical discourse analysis

Fairclough et al. (Citation1997) establish eight foundational tenets of critical discourse analysis (CDA) as both theory and method. These are: (i) CDA is concerned with social problems; (ii) power relations are discursive; (iii) discourse is productive and spawns society and culture; (iv) discourse does ideological work; (v) discourse is historical; (vi) the link between text and society is mediated; (vii) discourse analysis is interpretative and explanatory; (viii) discourse is a form of social action. Consonant with Gadamer’s (Citation1981) fusion of horizons (i.e. method and theory in this case), this study applied a dialectical iterative process between linguistic and semiotic aspects (hermeneutic circle). It is in the interstices of this circulus fructosis of the analysis of media coverage, employing CDA as both a theory and method, that a good gestalt emerges (Kvale & Brinkman, Citation2006, p. 210).

CDA is interdisciplinary and, as such, has often been complemented with critical social theories to amplify theoretical rigor (Fairclough et al., Citation1997; van Dyk, Citation1995; Hansen & Machin, Citation2019). In this regard, insights from critical race theory and critical whiteness studies have been employed. When race theorists, such as Tatum (Citation2017) and Feagin & O’Brien (2003), bemoan white people living in a ‘white bubble’ with little or no interest in reaching out across the racial divide, such observations are commensurate with critical race theory’s tenet of racism as normal, the default position where racialized minorities are rendered invisible. DiAngelo’s (Citation2021) distinction between shame and guilt in relation to white progressives is salient. In brief, shame is a temporary and, paradoxically, benign, transient, and socially acceptable emotion as opposed to guilt, which demands penance and action (e.g. reparations).

For white progressives, shame is seen as socially legitimate (or we wouldn’t express it), a sign that we care and that we feel empathy. This may be why we express shame so much more readily than guilt. Guilt means we are responsible for something; shame relieves us of responsibility. If I focus on what I did, I must take responsibility for repair. If I focus on who I am, it is impossible to change, and I am relieved of responsibility (DiAngelo, Citation2021, p. 123).

As a method, CDA has seen a burgeoning interest in the specific analytical toolkit it brings to texts, semiotics, and spoken language (Kress, Citation1989; Van Leeuwen, Citation2005). CDA scrutinizes the choice of lexicality, transitivity, nominalizations, and collocations, among others, which are mined for meaning. Following Hansen and Machin (Citation2019), of interest were the choices editors, journalists, and photographers in this study made in, among others, naming and referencing people and events, the classification of social actors, and the representation of social action. Norman Fairclough (Citation2013) highlights the ‘linguistic turn’ in social theory and the salience of critical discourse analysis in unmasking the machinations of power and ideology through the scrutiny of language. Drawing on Halliday’s (Citation1978, Citation1994) transitivity analysis, the analysis reveals a preponderance of material processes where much of the media coverage made an inventory of the actions of the stakeholders and their consequences upon the ship, slaves, or their own wealth, for instance. In contrast, a tiny few evince mental processes where the feelings or consciousness of the slaves are centered. Critical discourse analysis, then, is suited to the task of decoding how mediascape encodes and reinforces ‘the normalcy and normativeness of whiteness’ (Fleras, Citation2011, p. ix). The latter is commensurate with the aims of this study, which argues that the media coverage of the Norwegian slave trade, while courageously exposing the names and activities of Norwegian stakeholders, suppresses the story of the slaves and fails to draw parallels with contemporary antiracist struggles. According to van Dijk (1995), the media propagates a set of binary oppositions in relation to minoritized demographics that undermines their status in society. If consciousness is a desideratum in the process of emancipation, the epistemic culture secreted through the media hamstrings emancipation, failing to provide the readership with robust tools for grappling with modern permutations of racism.

Findings and analysis

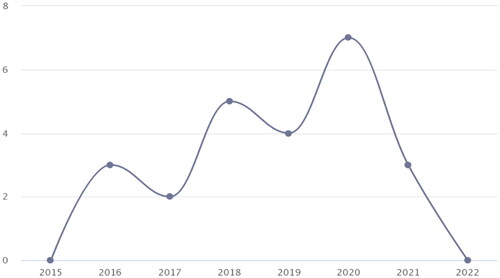

below shows the number of articles in Norwegian media on the Danish-Norwegian slave trade between 2015 and 2022. The caption in the figure in Norwegian refers to the keywords used to generate the graph (Danish, Norwegian, slave trade, Arendal (city in Agder county, southeastern Norway), slave ship). The spike in 2020 coincides with the murder of George Floyd, captured on video and instantly ricocheted around the world. The protests gelled into perhaps the largest social movement in U.S. history (Wirtschafter, Citation2021), encapsulated by the viral hashtag #BlackLivesMatter.

As mentioned in the methodology section, four main themes were identified through a content analysis of the representative newspaper samples: (a) the framing lenses; (b) historical focus or contemporary focus; (c) portrayal of slaves; and (d) lessons for the present. Nine sources (with a print and online presence) turned up 24 hits. The lion’s share of the reports were (see table below), not surprisingly, from the city of Arendal (Agderposten), where the wreck of the slave ship Fredensborg was discovered by amateur divers in 1974. Not surprisingly, the Oslo-based newspaper Klassekampen, with a revolutionary socialist political alignment, is next in its coverage of the Danish-Norwegian slave trade with three articles. This is followed by Bergensavisen, located in the city of Bergen on the west coast of Norway. Some merchants and luminaries from Bergen profited from the slave trade, hence the media interest. Of note is the lack of coverage from newspapers in the north of Norway. The readership and circulation in are for both print and online in 2021 (source: Mediebedriftenes Landsforening, 2022).

The framing lenses

Fourteen of the sixteen articles analyzed narrate the story of Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade during the Danish-Norwegian union through one of the following lenses: Norwegians who either owned slaves or profited from the trade, the captain and crew of the ill-fated slave ship Fredensborg, shed light on Norway’s slave trade and Norway’s reluctance to accept its colonial and ‘bloody’ slave past. In the two remaining articles (see , numbers 14 and 15), the film director, Ole Bernt Tellefsen (no. 15), who made the documentary film based on the slave ship, rebuts the author, Marianne Solberg, who alleges ‘the film is marred by a long series of misleading claims approaching historical falsification’ (no. 14).

Table 2. Headlines in the media.

Nine of the articles in frame the slave trade through the prism of Norwegians or Norway’s culpability as a nation. Discourse shapes our experiential world through the frames that seek to make the past and present cohere. Hence, framing is often employed as a ‘complex cognitive structure that links together the attributes of a concept in a web of relationships’ (Johnstone, Citation2008, p. 187). Article No. 1, for instance, frames the story of the Norwegian slave trade by personifying and individualizing both the slave traders and their slaves. For instance, the Norwegian merchant, chamberlain, and playwright Bernt Anker (1746–1805) is described in this manner by the historian and head of the Maritime Museum in Aust-Agder, Per Ivar Hjeldsbakken Engevold: ‘Bernt Anker, Norway’s richest man and brother of the Eidsvoll man Peder Anker, had his ‘own negro’, Christian Soliman, who was baptized in 1786 in Akershus castle church’ (No. 1). A few paragraphs later, Engevold states:

Here in Kristiansand, for example, we have the story of Casper and Catharina, slaves of Johan Sigismund Hassius von Lillienpalm [1660–1742]. He was knighted by the king and had been governor of Trankebar [the former Danish-Norwegian colony in Tamil Nadu, India], as well as commander of Dansborg Fortress in the same place.

Then he got a position as a diocesan governor in Kristiansand and returned with a whole court of native servants and slaves as well as family. We can only imagine the impression this must have made on little Kristiansand [city in south Norway] at the time (No.1).

It is argued, commensurate with DiAngelo’s (Citation2021) observation, that, in the main, Norwegian mediascape’s coverage of the history of Norway’s culpability in the slave trade engenders feelings of shame rather than guilt, which is unhelpful. DiAngelo (Citation2021) draws upon discourse analysis and delineates the difference between the two emotions in this manner:

Guilt is generally understood as based on something bad we have actually done and for which we are responsible, and shame refers to something we believe we inherently are and cannot change. Put simply, guilt is a feeling we have about doing bad, and shame is a feeling we have about being bad. I have observed that white progressives will readily express feelings of shame about racism but hesitate to express guilt (DiAngelo, Citation2021, p. 121).

Historical focus or contemporary focus

Significantly, while the majority of the articles focused on Norway’s colonial past and the names of prominent historical figures implicated in the slave trade and certain slaves, a tiny few explicitly sought to draw contemporary lessons piggybacking on the Black Lives Matter movement, the murder of George Floyd, and the Rhodes Must Fall movement. For example, Article No. 4 focuses on the last journey of the slaveship Fredensborg and dissects the captain Ferentz’s logbook.

Everything was to be counted and quantified, including the misery. On June 2 [1768], both male and female slaves died. They were immediately thrown overboard. On Sunday, June 5, Ferentz also wrote that 5 out of 6 female slaves who had stolen salt each received 10 lashes of the cat [i.e. cat o’ nine tails; a flail or multi-tailed whip], i.e. 10 lashes of the nine-tailed cat. On June 10, a male slave died, and on Monday, June 13, another female slave died. The next death took place on Thursday, June 23. This time, it was the sailor Jochum Bollevald who died. He was sewn into the company’s hammock, the flag was hoisted at half-mast, a hymn was sung, and he was thrown overboard (No. 4).

In Article No. 11, with the headline ‘The Bergen Slave Trade’, author and researcher Fartein Horgar states,

Many believe that Norway was blameless since we were under Denmark. But Norway was an almost equal partner in the dual monarchy, as was the slave trade. 35% of the Danish-Norwegian slave tonnage were Norwegian ships, and Bergen was by far the most important Norwegian seafaring city. If we calculate backwards, this means that approximately 1.1 million Africans were captured and transported only to the Danish-Norwegian colonies so that Europeans could eat sugar (No. 11).

While the analyses of the two articles are effective in sharing the grisly details of life on board slave ships and the culpability, especially for a Norwegian readership disinclined to accept this as an integral part of their history, the journalists stop short of linking this tragic past with current antiracist struggles. These narrations are commensurate with Aristotle’s logetic mode (Richardson, Citation2007) of rhetorical proof underpinned by inductive or deductive schemes of argument. For instance, the journalist behind Article No. 4 concludes with a pithy and vague reference to modern-day slavery. ‘Although it will soon be 250 years since Fredensborg was shipwrecked, slavery still exists and thrives’ (No. 4). Referring to the exhibition ‘Slavegjort [enslaved]’ in the city of Arendal with a section on modern slavery, the writer concludes that this ‘raises the question of what makes certain people still at risk of ending up in slavery or forced labor’ (No. 4).

Black and brown people in Norway comprise roughly 11.2% of the total population of 5.4 million (Statistics Norway, Citation2022). This demographic would be better served, especially with movements such as BLM, if the conclusions drawn from Article No. 4 drew parallels with contemporary modern incarnations of racism that are subtle yet blight the lives of many people of color, even in egalitarian Norway. Regrettably, Article No. 4 misses the target and raises concerns about the valid interpretation and application of historical lessons commensurate with Fleras’ (Fleras, Citation2011, p. 14) observation that ‘what is excluded from the ‘frame game’ is just as informative as what is included’. Omissions and a lack of alternative applications belie ignorance about people of color’s visceral experience of racism, as black scholar Beverly Daniel Tatum contends.

The chief obstacle to having an intelligent, or even intelligible, conversation across the racial divide is that, on average, white Americans talk mostly to other white people. The result is that most whites are not socially positioned to understand the experiences of people of color (Tatum, Citation2017, p. 45).

However, there are a couple of articles that attempt to see this endeavor at uncovering the past in light of global antiracist movements such as Black Lives Matter. Significantly, one such article (Article No. 13) is written by the Norwegian-Congolese, Ingrid Ciakudia.

It is also noteworthy that Ciakudia writes in the newspaper Utrop, Norway’s first multicultural newspaper, which has the following mission statement on its website:

Utrop conducts serious and critical journalism and functions as the minorities’ arena for free information, social criticism, and debate. Utrop’s goal is to bring together people of all ethnic backgrounds, including Norwegians, under a multicultural foundation and on equal terms in order to create a tolerant society with respect for diversity. Utrop will contribute to a society free of racism and prejudice, to a democratic, liberal, and pluralistic society… (Utrop, 2022).

The discussion about the degree to which one should pull down statues of well-known Norwegians who have invested in the slave trade has made big headlines. There have also been debates in the media about everyday racism (No. 13).

The Norwegian slave trade-contemporary racism nexus appears unique to Ciakudia’s article and can perhaps best be attributed to a heightened sense and awareness of the long shadow the past casts even today in the permutations that characterize fear of the black body. Transitivity analysis, such as Michael Halliday’s (Citation1994) six processes, helps detect the kind of agency attributed to an actor. Ciakudia’s article is peppered with mental processes where feelings and affections proliferate. For instance, ‘Tellefsen [the film director] shares that it often became stronger than he thought on the film set… ‘I had to stop the filming because people were overwhelmed’’ (no.13). Hansen & Machin (2017, p. 133) state that:

It is often the case that participants who are made the subjects of mental processes are constructed as the ‘focalisers’ or ‘reflectors’ of action. These actors are allowed to have an internal view of themselves. This can be one device through which listeners and readers can be encouraged to have empathy with that person.

Portrayal of slaves

As mentioned previously under the first theme, ‘the framing lenses’, a content analysis of the majority of the articles clearly shows the journalists espouse a mission—one that employs the discovery of the wreck of the slave ship Fredensborg as a synecdoche for Norway’s involvement in the slave trade and the existence of slaves in mainland Norway. In the main, this is done by tapping into a timeline of the slave ship’s history, the Norwegian slave owners, and the wealth generated. Once again, a paltry few, such as the previously mentioned Ciakudia’s article, concern themselves with humanizing and personalizing the slaves. Article No. 9, for example, makes a brief mention of Musobwa Mechake, who plays the role of Samson, a slave who dies in the crossing over the Atlantic in Tellefsen’s film documentary of the slave ship. Mechake, a Norwegian-Congolese from the city of Arendal, is thrown overboard into the sea. The article states: ‘It was cold, but it went well, said Musobwa, who said yes to playing the role of slave because it was important that the sufferings of the slaves is portrayed’. It is part of the story’.

Article No. 8 with the headline ‘Used African slaves as decoration’ is interesting in that the coverage features excerpts from an interview with Joseph Crophy Crampah, a Norwegian-Ghanaian. According to the journalist, Joseph Crophy Crampah is a friend of the film director Ole Bernt Tellefsen and plays the role of an African slave trader. We are told that Tellefsen has several friends from culturally diverse backgrounds in Kristiansand due to his passion for music, and it is these friends who volunteered as actors and extras in his film. The article goes on to state, in regard to Crampah:

His character is one of those who, in exchange for spirits and weapons, sold slaves on to the Danish-Norwegian traders who came to the ‘Gold Coast’ in Africa. His own parents belonged to the Akwamu people and were engaged in the purchase and sale of slaves. ‘The slave trade existed in Ghana long before Europeans came’, he says. Wealthy Ghanaians used the poor from their own country as servants, and the internal wars in the country led to a hierarchy where some had a lot, while others became the ‘possessions’ of the rich. ‘We had a slave culture in Ghana before the whites came’, he said (Article No. 8)

In Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire (2018), Akala refers to this old adage that British students learn at school about slavery: ‘Africans sold their own people’ (Akala, Citation2018, p. 137). To begin with, he counters, only twisted logic would argue that such an argument exonerates Europeans of the evils of the transatlantic slave trade. Secondly, this erroneously implies that all Africans had a common kingdom, culture, and identity. ‘In fact, as the award-winning historian Sylviane A. Diouf notes, ‘in none of the slave narratives that have survived do the formerly ensaved talk about being sold by other ‘Africans’, or by ‘their own people’’ (Akala, Citation2018, p. 138). Akala highlights the perverseness of this argument by drawing an analogy with English-Irish relations of the past in averring that the Irish did not interpret English bellicosity in terms of ‘white brothers and sisters’ from England deliberately starving the Irish to death during the potato blight of the 1840s. In other words, the term ‘Africans’ becomes a discursive construction imposing a monolithic identity in order to scapegoat Africans for the slave trade and ameliorate European liability.

This colonial projection of Africa is useful to some as it avoids them having to use the usual tools to explain the behavior of real human beings: economics, market demand, dynastic rivalries, ethnic enmity, class distinctions, pure profit-seeking, self-preservation, love, and more. It allows one to offer a person’s ‘African-ness’, a concept that did not yet exist in the period, as an explanation for their behavior. ‘Africans sold their own people’ is the historical version of ‘black on black violence’ (Akala, Citation2018, p. 141).

In rebutting the corollary argument that Africans were docile, Akala states, ‘Historian David Richardson estimates that a million fewer people had to go through the middle passage because of this one form of resistance alone [i.e. attacks against slave ships]. It is also estimated that one in every ten European slave ships to dock in West Africa experienced either a shipboard revolt or an attack from land’ (Akala, Citation2018, p. 140). Richardson (Citation2022) mentions C.L.R. James’ book The Black Jacobins and argues that ‘the enslaved were not bystanders in debates over slavery but with commitment, leadership, and organization could… become agents of their own emancipation’ (Richardson, Citation2022, pp. 8–9).

Lessons for the present

As mentioned throughout the previous themes, the bulk of the reporting pivots around one main agenda: providing irrefutable evidence to a purportedly disinterested public to acknowledge the facts of the Norwegian slave trade. As the film director, Tellefsen, put it, ‘We Norwegians like to believe that it was the Englishmen who were the most eager slave traders, but we were equally involved. There were even slaves in Norway’ (Article No. 9). This is followed by the theme of Norwegians who profited materially from the slave trade. A case in point is Article No. 3, which cites the author Fartein Horgar: ‘Even after we left the Union with Denmark in 1814, Norwegians continued the trade. There is so much old money in the coastal cities. What no one declares is that these fortunes were founded on slavery. We refuse to acknowledge our guilt and moral debt, according to Fartein’. However, and as alluded to earlier, one fails to detect any sustained or rigorous engagement with contemporary antiracist struggles.

One of the few articles to give expression to this incongruence is Article No. 7. The article is a critical review of the exhibition ‘Slavegjort [enslaved] in Kuben, Arendal, which features the United Nations’s sustainable development goals’. While the entrance to the exhibition, a freight container, jars the visitor’s senses, the reviewer laments what he perceives as a disconnect between the aim of sensitizing the visitors as consumers with the narrative about the slave ship and the history of colonization. The critic behind this article, Christer Dynna, questions whether the Norwegian public is even aware that the common name for grocery stores in Norwegian, kolonialen, has its roots in the word colonial goods (kolonialvarer), such as sugar and coffee: ‘The nameless African people who did forced labor on plantations were inextricably linked to the European consumers’ penchant for coffee and sugar at the time’ (Article no. 7).

From the perspective of contemporary antiracist struggles, the vexed trajectory of the slave trade, as narrated through a white-centric lens, does little to alter the traditional image of Blacks as either the eschewed or exotically essentialized ‘‘Other’. As pointed out earlier, one is hardpressed to detect any attempts to link the slave trade with the current concerns of Norwegians of color. The one black ‘slave’ actor, Joseph Crampah, who is personalized, interviewed at length, and foregrounded in the image, appears to ventriloquize the widespread mantra of ‘Africans selling their own’. The above resonates with the view that ‘minorities are looked at from a white-o-centric point of view, thus reinforcing pre-existing beliefs, while minority women and men internalize a white way of being looked at’ (Fleras, Citation2011, p. 44).

The social theorist and race scholar Joe Feagin’s observations in the US context overlap with aspects of the problem in Norway.

A key to understanding the social context of much stereotyped thinking about racial matters is the fact that most whites live in what might be termed the ‘white bubble’ – that is, they live out lives generally isolated from sustained and intensive equal-status contacts with African Americans and other Americans of color … White views of Americans of color often seem to be made from a distance either in time or space. For all whites, this distant or distancing view can result in insensitivity or ignorance about the conditions of people across the color line (Feagin & O’ Brien, 2003, pp. 25, 26).

Recent years have seen increased rates of ethnic segregation in Norway. The intensity with which the media heralds ethnic segregation in Norway appears to increase every year: ‘There is an extreme segregation in Oslo schools going on. Now it is time to act’ (Aftenposten 31.05.22) and ‘rich and poor see less of each other in the cities. Why has it become this way?’ (Forskning.no 04.02.21). It is argued that journalists’ living in ‘white bubbles’ perhaps explains the inability to harness the lessons of the slave trade to the extant antiracist worries of 11% of the Norwegian population with roots in Africa and Asia.

The Norwegian slave trade, when conceptualized through the framework of critical race theory’s (CRT) three tenets, is instructive. It maintains that racism is so entrenched, it is ‘normal’, that whites reluctantly address racism when it is in their interest to do so (interest convergence), and that subversive or counter-storytelling is an effective antiracist device (Bell, Citation1995; Delgado & Stefancic, Citation1998; Lawrence, Citation2012). We argue that the mostly white journalists behind the articles are not co-conspirators in a plot to privilege the story of the slave ship, Norwegian slave traders, and their wealth at the expense of the slaves but are unable to fathom the depths of racism as ‘normal’ in white society commensurate with the first tenet of CRT. Even the otherwise liberal and progressive film director, Tellefsen, makes it explicit that his focus is on the extent of Norwegian involvement, not the slaves per se.

I don’t want the average Norwegian to be ashamed, but I am very keen to get an awareness of it and not keep walking around with this rosy and naïve look on my own nation’s behalf, which is perhaps the most important thing (Article no. 13).

The machinations of the second tenet of CRT are evident in Tellefsen’s response when asked about the film reception coinciding with the Black Lives Matter movement energized by the Rhodes Must Fall movement. ‘Now, after BLM and a lot of fuss about which statues should be demolished and which should be allowed to stand, I’m of course even more excited than I was in the first place’ (No. 13). Whites accommodate the interests of blacks as long as they converge with white interests. Global push and pull factors, such as the fear of Communist influence upon African Americans and countries in the Global South during the Cold War, saw changes in U.S. policy. What transpired was ‘one of those rare times when the fortunes of blacks and whites were aligned’ (Delgado & Stefancic, Citation1998, p. 472). The study has also drawn attention to the fact that one article, written by a black journalist (no. 13), was anomalous in putting the spotlight on current antiracist struggles and humanizing the slaves. This resonates with the third tenet of CRT—subversive or counter-storytelling as a device of empowerment. ‘Critical race theorists have often used narrative in our scholarship. We tell our stories because other scholars have not told them. to tell the world and ourselves that we are whole and fully human, that we are you, that our stories are yours’ (Lawrence, p. 2012, p. 251). The monovocal, majoritarian narratives are upended: reference is made twice to the BLM movement and once to the pulling down of statues; the article explains how the Church defined slaves as non-human to expedite slavery; and Tellefsen shares how he found a way to humanize the slaves in his dramatization:

He explains that the slaves don’t have much to say in the film, but that he has focused as a director on face and expression. I hope some people are left wondering why the hell they weren’t allowed to say anything. If people get annoyed about it, then I’m happy (no. 13).

Limitations of the study

One limitation in our study is the potential for the views expressed by the journalists analyzed to not be fully representative of the general editorial stance or agenda of the newspapers or media outlets they represent. Journalists operate within the framework of their respective organizations, which may have editorial guidelines, political leanings, or commercial interests that influence the content they produce. Thus, the perspectives presented in the analyzed articles may not necessarily reflect the broader stance of the newspapers or media outlets as a whole. Furthermore, it’s important to recognize that these opinions are subject to evolution over time.

Moreover, it’s crucial to acknowledge that each reporter and newspaper may possess distinct political inclinations, potentially leading to divergent perspectives. Consequently, these individual viewpoints may not accurately represent or reflect a cohesive, discernible national discourse on the topic. Furthermore, our study does not delve into the impact of the media coverage on the audience or readership. While we analyze the content and framing of articles, we do not directly assess how these representations may shape public perceptions, attitudes, or behaviors regarding Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Understanding the audience reception and the ways in which media narratives are interpreted and internalized is crucial for a comprehensive analysis of media influence.

Implications for history education in schools and higher education

Promoting a comprehensive and policy-oriented history education about Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade is indeed essential for fostering a deeper understanding of this historical period and its consequences. Here are some suggestions for improving history education on this topic in schools and universities:

Curriculum Development: The authorities should review and revise history curricula to include a thorough examination of Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. The curriculum should cover key aspects such as the historical context, Norwegian participation, economic implications, and the social and cultural impact on both the enslaved individuals and the nation as a whole. Commensurate with Norway’s new curriculum (LK20), it is important to approach the subject by fostering interdisciplinary connections by integrating the study of Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade into other subjects, such as literature, art, sociology, and economics. This approach helps students understand the multidimensional nature of historical events and their broader societal impact.

Research and Scholarship: Encourage and support research on Norway’s historical involvement in the slave trade. Provide funding and resources for scholars to investigate and document this history, including contributions from Norwegian merchants, shipowners, and others involved in the trade. Promote the publication of academic papers, books, and articles to contribute to the body of knowledge on this topic.

Integration with Contemporary Issues: Connect the historical context of the transatlantic slave trade to present-day issues such as racial discrimination, human rights, and social justice. Encourage students to explore the legacy of slavery and its ongoing impact on societies, fostering a deeper understanding of the relevance of this history to contemporary challenges.

Collaboration with International Institutions: Foster collaboration with international institutions, such as universities, research centers, and museums, that specialize in the study of the transatlantic slave trade. This partnership can facilitate the exchange of knowledge, resources, and best practices, enriching the educational experience for students and educators.

Primary Sources and Multiple Perspectives: Encourage the use of primary sources, including historical documents, firsthand accounts, and visual materials, to provide students with a direct connection to the historical events. Additionally, present a variety of perspectives, including those of enslaved individuals, abolitionists, and critics of the slave trade, to foster a nuanced understanding of the complexities involved.

Guest Speakers and Experts: Invite guest speakers, scholars, and experts in the field of transatlantic slavery to provide lectures, workshops, or seminars. Their insights and research can enhance students’ understanding of the subject matter and stimulate critical thinking and discussions.

Engaging Teaching Methods: Utilize interactive teaching methods such as debates, role-playing activities, and group projects to encourage active student participation. These methods can help students analyze different viewpoints, develop critical thinking skills, and empathize with the experiences of those affected by the slave trade.

Field Trips and Exhibitions: Organize visits to relevant museums, historical sites, and exhibitions that focus on slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. This hands-on experience can provide students with a tangible connection to the past, deepen their understanding, and promote empathy and reflection.

Teacher Training and Resources: Provide professional development opportunities and resources for teachers to enhance their knowledge and teaching strategies regarding Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Workshops, seminars, and online courses can help educators develop effective lesson plans and facilitate productive classroom discussions on this topic.

Digital Resources and Online Platforms: Create digital resources and online platforms that provide accessible and engaging materials for students and educators. These resources can include digitized primary sources, interactive maps, virtual exhibitions, and educational videos, allowing for flexible learning outside the traditional classroom setting.

Currently, several of the recommendations above, such as museums, educational material, and even experts, are nonexistent in most parts of the country. However, once the full scale of Norwegian culpability in the transatlantic slave trade is acknowledged, there is a moral obligation to follow up with the construction and maintenance of what we call an ‘architecture of redress’. Jones (Citation2006, p. 43) defines the ‘architecture of education’ as,

A complex web of ideas, networks of influence, policy frameworks, financial arrangements, and organizational structures. These collectively can be termed the global architecture of education, a system of global power relations that exerts a heavy, indeed determining influence on how education shapes the relationship between education, development, and poverty strategies. It determines how education takes its place as a dimension of economic, political, and social policy at the country level (Jones, Citation2006, p. 43).

We draw upon Jones’ understanding of the ‘architecture of education’ in arguing for the need to acknowledge and implement an ‘architecture of redress’ in relation to Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. By implementing the eight-pronged strategies outlined above, the government and educational institutions can provide students with a comprehensive and policy-oriented understanding of Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. This approach can help foster critical thinking, empathy, and a commitment to social justice among future generations.

Conclusion

This study explored the Norwegian media’s coverage (2015–2022) of the discovery of the wreck of a slave ship in 1974 and how this coverage related to contemporary antiracist issues such as the BLM and RMF movements. Between 1670 and 1804, 110,000 enslaved people were transported from Africa to the Americas [the Danish West Indies (Saint Thomas, Saint Croix, and Saint John)] on ships belonging to the Danish-Norwegian kingdom. Stawski (Citation2018) disputes these numbers, claiming a figure that is six times higher, making the Denmark-Norway slave trade not the 7th but the 5th largest slave-trading nation, surpassed only by Portugal, Great Britain, and France. A content analysis was applied to 16 of a total of 24 newspaper articles (online and print versions) informed by critical discourse analysis and tenets of critical race theory.

The majority of the papers refract the story through a parochial prism of Norwegians who either owned slaves or profited from the trade, the captain and crew of the ill-fated slave ship Fredensborg, a film documentary shedding light on Norway’s slave trade and Norway’s reluctance to accept its colonial and ‘bloody’ slave past. The overarching objective appears to be documenting the facticity of the Danish-Norwegian slave trade, with a particular focus on the significant role played by Norwegians. The journalists and the film documentary assume the role of archaeologists in making a historical inventory of this epoch. It is argued that while the above is laudable given the miasma of ignorance surrounding the role of Norwegians in the slave trade, the coverage descends into not so much a conversation between white Norwegians as a top-down rebuke and reprimand of what appears to be a heuristic readership disinclined to come to terms with its culpability in the slave trade. Lost in this crossfire is the over 11% of black and brown Norwegians of African and Asian extraction, in whose eyes Norwegian culpability in the slave trade is treated as an isolated compartmentalized historical event dislocated from contemporary antiracist struggles, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, the murder of George Floyd, the Rhodes Must Fall movement, and the racial microaggressions of the everyday that are left unaddressed.

It is argued that the mediascape in Norway, while continuing to put the spotlight on the facts of Norwegian involvement in the slave trade, ought to consider what this coverage would look like from a perspective that is cognizant of and empathetic towards the concerns and needs of non-white Norwegians, whose demographic is expanding. The study also outlined recommendations for policymakers and educational institutions that have the potential to create a robust and comprehensive framework for addressing Norway’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Such policy-oriented approaches, it is argued, will promote historical understanding, empathy, and a commitment to social justice among students and the wider community.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Thomas

Paul Thomas is Professor of Pedagogy specializing in critical pedagogy and multicultural education. His extensive research explores themes of social justice, minority experiences, and inclusive educational practices in Norway and beyond. Through rigorous analysis and personal narrative, Thomas advocates for transformative approaches to education that address systemic inequalities and promote equity.

Jocelyne Von Hof

Jocelyne Von Hof is Assistant Professor of Pedagogy and specializes in studying the practices of educators in multilingual settings, ensuring the inclusion of minority language-speaking children. Her research highlights the importance of educators valuing language proficiency to create supportive learning environments. Von Hof’s work emphasizes inclusive practices that prioritize cultural identity and linguistic diversity.

References

- Achebe, C. (1977). An image of Africa. The Massachusetts Review, 18(4), 1–15.

- Agderposten. (2018, June 15). Slaveskipets siste reise. Arendal, Agder. Retrieved November 22, 2022, from https://app-retriever-info-com.ezproxy1.usn.no/services/archive?canFetchDataOnDateSelectorChange=true&period=allDates&searchString=Slaveskipets%20siste%20reise%20

- Akala. (2018). Race & class in the ruins of empire. Two Roads.

- Bell, D. (1995). Who’s afraid of critical race theory. University of Illinois Law Review, 4(3), 823–846.

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Free Press.

- Brooks, C. (2014). Caribbean countries unlikely to see slave-trade reparations from Europe. AlJazeera America: http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/1/12/caribbean-nationsaimforreparations.html

- Bryman, A. (2004). Social research methods (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bufdir. (2021). 4 av 10 unge og innvandrere har opplevd diskriminering. https://www.bufdir.no/en/aktuelt/4_av_10_unge_og_innvandrere_har_opplevd_diskriminering/

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (1998). Critical race theory: Past, present. Current Legal Problems, 51(1), 467–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/51.1.467

- DiAngelo, R. (2021). Nice racism: How progressive white people perpetuate racial harm. Beacon Press.

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Language and power. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R, T. van Dijk. (1997). Critical discourse analysis. In. Discourse as social interaction: A multidisciplinary (1st ed., Vol. 2, pp. 258–284). Sage.

- Feagin, J., & O;Brien, E. (2003). White men on race: Power, privilege, and the shaping of cultural consciousness. Beacon Press.

- Fleras, A. (2011). The media gaze. UBC Press.

- Gadamer, H. G. (1981). Truth and method. Sheed & Ward.

- Halliday, M. (1978). Language as a social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Cambridge University Press.

- Halliday, M. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar. Arnold.

- Hansen, A., & Machin, D. (2019). Media and communication research and methods. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Holsti, O. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences. Addison-Wesley.

- Hopkins, D. (2013). Peter Thonning and Denmark’s Guinea Commission. Brill.

- Johnstone, B. (2008). Discourse analysis. Blackwell Publishing.

- Jones, P. W. (2006). Education, poverty and the World Bank. Sense Publishers.

- Kress, G. (1989). Linguistic processes in sociocultural practice. Oxford University Press.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkman, S. (2006). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative Research. Sage.

- Lawrence, C. (2012). Listening for stories in all the right places. Law & Society Review, 46(2), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00487.x

- Mediebedriftenes Landsforening. (2022, November 15). https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A//www.mediebedriftene.no/siteassets/dokumenter/tall-og-fakta/lesertall/2021/15sept21/medietall-lesertall-mediehus-21_2.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

- Retriever. (2022, November 26). Retriever. Research: https://www.retrievergroup.com/product-research

- Richardson, D. (2022). Principles and agents: The British slave trade and its abolition. Yale University Press.

- Richardson, J. (2007). Analysing newspapers: An approach from critical discourse analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smooth, J. (2014). How I learned to stop worrying and love discussing race. Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbdxeFcQtaU

- Statistics Norway. (2022). Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents. Statistics Norway.

- Stawski, S. (2018). Denmark’s veiled role in slavery in the Americas: The impact of the Danish West Indies on the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Harvard Library. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/37365426/STAWSKI-DOCUMENT-2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Tatum, B. (2017). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria. Penguin Books.

- The Local. (2013). Norway asked to pay up for slave-owning past. The Local: https://www.thelocal.no/20131212/caribbean-demands-cash-from-norway-for-slave-owning-past/

- Thomas, P. (2016). “Papa, am I a Negro?” The vexed history of the racial epithet in Norwegian Print Media (1970–2014). Race and Social Problems, 8(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-016-9179-4

- Utrop. (2022, November 17). Om oss. Utrop: https://www.utrop.no/om-oss/

- van Dyk, T. (1995). The mass media today: Discourse and domination or diversity. Javnost/the Public, 2(2), 28–42.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T., & Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: a discourse-historical analysis. Discourse Studies, 1(1), 83–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445699001001005

- Wirtschafter, V. (2021, June 17). How George Floyd changed the online conversation around BLM. The Brookings Instiution: https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/how-george-floyd-changed-the-online-conversation-around-black-lives-matter/