Abstract

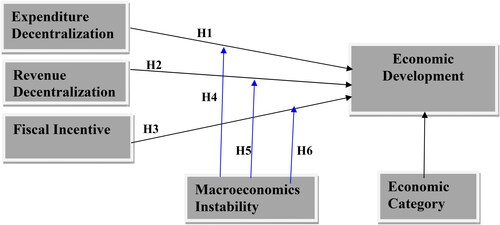

This study aimed to scrutinize the association between fiscal federalism and economic development in Ethiopia. By employing ten sub-national government (SNG) data over the period 2005–2018, the study uses the Partial Least Square Structural Model (PLS-SEM). The study proved that revenue decentralization and fiscal incentives significantly enhance economic development. Nevertheless, expenditure decentralization significantly deteriorates economic development. Moreover, economic instability has an adverse moderating role in the contribution of revenue decentralization to economic development. However, it has no role in the indirect effect of expenditure and fiscal incentives on economic development. The control variable (economic category) shows that SNGs in emerging economies have significantly lower economic development than SNGs in advanced economies. The most important inference is that the center should review the devolution of expenditure responsibility and autonomy to SNGs. Hence, the ideas of fiscal federalism contend that the execution of expenditure decentralization positively affects SNGs’ economic development. The SNG should be more assertive in controlling the local economy since the national government is limited in overseeing development execution in the areas. The study attempts to combine the two theoretical perspectives of fiscal federalism and examines the direct effect of fiscal federalism on economic development and its indirect influence through the moderating variable (i.e. macroeconomic instability). Therefore, it contributes to the prevailing literature on fiscal federalism.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Scholars have examined the nexus between fiscal federalism and economic growth. However, they overlooked essential indicators of economic development (i.e. the Human Development Index, clean water, and others). Because economic growth cannot explicitly show the degree to which citizens benefit from the nation’s economic performance, the study scrutinizes the effect of fiscal federalism on economic development. Moreover, the study examined the moderating role of macroeconomic instability in the connection between fiscal federalism and economic development. The study utilized the PLS-SEM to analyze the data.

The study findings disclosed that revenue decentralization and fiscal incentives foster economic development. Nevertheless, expenditure decentralization hampered economic development. Moreover, macroeconomic instability negatively moderates the connection between revenue decentralization and economic development, indicating that a rise in macroeconomic instability weakens the positive relationship between revenue decentralization and economic development. The study urges the central government to connect SNG’s expenditure needs with SNG’s revenue.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

According to fiscal federalism theory (Bird, Citation1999), the division of duties among the several levels of government and their financial ties are vital considerations. First- and second-generation fiscal federalism are the two streams into which fiscal federalism theories are divided in the academic literature. First Generation Fiscal Federalism (FGFF) emphasizes revenue centralization more than expenditure centralization. It contends that centralized taxation of mobile inputs inhibits the movement of production factors like income, payroll, and sales taxes because it supports the position that the national government should handle redistributive duties. Most governmental income comes from this tax base (Boadway & Tremblay, Citation2012; Oates, Citation2005).

By emphasizing that the benefits obtained by individuals need to be proportionate to the expense of holding them, Second-Generation Fiscal Federalism (SGFF) strongly emphasizes the self-sufficiency of local government spending demands (Boadway & Tremblay, Citation2012). Fiscal imbalance is a term used in the fiscal federalism theory to describe the situation in which the national government has more authority to raise money than is necessary for the execution of its powers, while the SNG level has a weak power to do so (Boadway, Citation2005; Boadway & Tremblay, Citation2012; Oates, Citation2005). The FGFF considers intergovernmental transfer (IGT) a tool that preserves equity concerns.

Contrarily, SGFF considers the incentive consequence of IGT on subnational government (SNG) policymaking or economic development. However, the SGFF advocated for goal transfer systems to be unambiguous ‘gap-filling’, since delivering a more significant payment to regional states with wider gaps can boost rent-seeking. Unlike the FGFF, the SGFF seeks considerable links between regional expenditures and regional revenue and helps match the interests of regional governments to regional development. Thus, ‘fiscal incentive’ links own revenue and total SNG expenditure.

Fiscal decentralization is a crucial aspect of fiscal federalism, as it transfers revenue and expenditure responsibilities from the national level to SNGs. It is essential for a vertical public sector financial structure; otherwise, resources, authority, and responsibilities would be accumulated at the national level. Therefore, the fiscal federalism theory propagates that the devolution of public services to SNGs increases economic growth. The SNGs reap the benefit of efficiency that can emanate from their knowledge advantage about public preferences over the central government (Oates, Citation1972, Citation2005). After finding out if there is an enduring connection between fiscal federalism and economic development, the government formulates options for economic policy. Every policy effort is connected to local government policy choices (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023c).

Raising a population’s standard of living and overall well-being is known as economic development. In its most basic form, economic development is concerned with the gradual extension of human potential. Economic development encompasses poverty reduction, income redistribution, and raising the income and output linked to economic development.

The nexus between fiscal federalism and economic development might be conditioned by critical economic variables; this aligns with the theoretical literature, and the level of development could be a factor that conditions such a relationship. Among other variables, a stable macroeconomic environment encourages investment, the growth of the financial sector, integration, and globalization, all of which are potential pathways for economic growth (Khalid, Citation2017). Even though scholars have conducted much empirical research on the subject, they still need to be more conclusive (e.g. Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a; Hung & Thanh, Citation2022; Lechner da Silva & De Brito Gadelha, Citation2022; Liu, Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Osmani & Tahiri, Citation2022; Siliverstovs & Thiessen, Citation2015; Xiao et al., Citation2022). Besides, the conflicting results point to the need for additional study.

The current study subsidizes the existing works by considering overlooked variables (i.e. macroeconomic instability) in the previous empirical studies. Accordingly, it investigates their moderating role in the connection between various fiscal federalism measures and economic development. In addition, it utilized new and contemporary second-generation statistics (PLS-SEM). Ethiopia’s federal structure has five government tiers: the federal, regional, zone, woreda, and kebele (local) levels (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). Thus, the study focused on the second tier of government and scrutinized the influence of fiscal federalism on economic development.

The following parts form the remainder of the present research. The literature review and hypotheses are provided in Part 2. The research method is explained in Part 3. Followed by results and discussion in Parts 4 and 5. The conclusion is delivered in the last part of the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Overview of the inter-governmental fiscal design of Ethiopia

Article 62(7) of the 1995 Constitution of Ethiopia empowers the House of Federation (HoF) to divide federal subsidies between SNGs. Some SNGs have low revenue collections, infrastructure, and institutional capacity compared to others. On the basis of this difference, the inter-governmental fiscal design of Ethiopia broadly classified SNGs into two categories, namely emerging and advanced regional states (SNGs). The House of Federation [HoF] (2009) grant allocation formula focuses on balancing revenue-raising ability, spending needs differences, and reserving 1% of the distribution pool for the emerging SNGs of Benishangul-Gumuz, Afar, Gambela, and Somalia. The Representative Tax System (RTS) and Representative Expenditure System (RES) are used to determine the revenue capacity and expenditure needs of these regions, ensuring proper allocation of federal subsidies.

2.1.1. Estimating revenue-raising capacities

The RTS is described as representative’ because it collects the most lucrative SNG revenue sources and thus holds most of the revenue collected by SNGs. Accordingly, a proper tax base and the applicable tax rate are identified to attain potential revenue that can be derived from an identified source (Tesfai, Citation2015). Revenue-raising capacity measures states’ effective tax yield (ETY) on the basis of seven tax bases. These taxes or fees are personal income tax, business profit tax, VAT, agricultural income tax, rural and land use fee, sales tax (TOT), and fees for medical supply and treatment.

2.1.2. Expenditure need estimate

For the estimation of the spending needs of SNGs, significant expenditure sectors have been included. Consequently, it encompasses sectors that hold a substantial share of the overall public spending of SNGs’ expenditures. The ‘representative expenditure divisions’ were considered (Tesfai, Citation2015). The key expenditure categories were considered in the formula: general administration costs, education, public health, agriculture and natural resources, clean water supply, rural road construction and maintenance, growth of micro and small-scale enterprises, and employment and urban development. The estimation of spending needs helps define the relative value of sectors and determine the budget needs of SNGs.

2.1.3. A Special equalization grant for emerging SNGs

For today’s Ethiopia, equalizing the expenditure needs of the SNGs is vital. Because of cost and need differentials, there are differences in the delivery of basic public services among the states. Although it is politically feasible to equalize the revenue side, it is hard to follow since there is a broad asymmetry between the SNGs’ economic bases. The national government fiscal equalization grant seized away a 1% subsidy from the common pool of SNGs to resolve their financial deficiency and support the four emerging SNGs. The special subsidies for emerging SNGs consider indicators and their weights to distribute funding (see in the Appendix).

2.1.4. Federal and SNGs borrowings

Ethiopia’s external public debt has mounted by 20% annually since 2006/2007, with infrastructure expenditures demanding substantial financing from external sources. The central government budget’s debt financing share has increased from 10–13% in 2019/20 and 2021/22. On the other hand, intergovernmental transfers (IGT) are employed to fill the fiscal gap between SNGs’ budgetary commitments and revenue bases. The distribution of revenue bases prompted a vertical fiscal imbalance.

According to NBE (2020), the SNGs collected only 27% of tax revenue in 2019–20. The Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) provides loans to the SNGs at a yearly funded rate of 7%. Thirty percent of the SNG loan was utilized to deliver fertilizer to farmers. The rest, 70%, was spent on several projects.

2.2. Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

Theories identify several processes through which fiscal decentralization influences growth. Fiscal federalism theories have been a point of contention in public fiancé literature for decades. Fiscal federalism has two theoretical strands, namely, FGFF and SGFF. The FGFF establishes a comprehensive regulatory structure for function assignment by presuming that SNG officials are good and constantly inspired to meet the interests of residents rather than their own personal and political goals (Oates, Citation1972, Citation2005). The primary concept of the FGFF is that SNGs must produce products and services that align with residents’ specific tastes and situations (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023c). The essential ground is that SNGs transfer the provision of public services by considering spatially pertinent costs and advantages, which improves productivity and economic benefit over the central government’s uniform allocation mechanism.

The ‘new fiscal federalism’ (Oates, Citation2005), which assumes a public choice perspective, has altered the FGFF. Politicians and SNG officials are more highly motivated by their fulfillment than by optimizing the population’s well-being. This ‘public sector as a monolith’ (Leviathan) stance claims that fiscal federalism will restrain the acts of a government that seeks to maximize its revenue. Brennan and Buchanan (Citation1980) contemplate devolution as a restraining device for SNGs’ undesired acts by fostering SNG’s race to deliver improved public service and enhance income by providing market-preserving commodities.

The market-preserving federalism theory is the fundamental component of constructing an SGFF. Despite numerous researchers’ criticism, it has solved several critical fiscal difficulties facing liberalizing states; it seeks to complement the FGFF rather than undermine it (Oates, Citation2005). The essential notion is that public-choice perspectives affect fiscal federalism. Moreover, undesirable sub-national government behavior is alleviated because high taxes and poor availability of public goods can result in households migrating to other jurisdictions (Weingast, Citation2009).

The FGFF favors centralizing revenue responsibilities; inter-jurisdictional rivalry would prove futile and reduce revenue, resulting in inadequate public goods and service supply. Additionally, since a decentralized tax system constrains the free movement of resources, a centralized tax system is frequently favored over expenditure responsibilities. On the other hand, one of the central claims of SGT is that IGT and bailouts encourage sub-national governments to spend recklessly and to shift the burden of paying for their wastefulness to the federal government, acts that threaten macroeconomic stability. As a result, SGFF suggests limiting IGT and adopting a no-bailout stance.

2.2.1. Fiscal federalism and economic development

Delegating power from the federal government to SNGs is part of fiscal federalism. Additionally, two related domains are involved. First, how public funds are allocated among the various levels of SNGs; second, how autonomous SNGs are in decision-making.

The fiscal federalism theory makes a nexus between decentralization and economic growth by adopting two assumptions. First, since subnational or local governments are considerably more in touch with consumers or voters than the central government, decentralization can enhance economic growth by improving the efficiency of SNG public service provisions. As a result, they are more acquainted with local tastes than the national government (Boadway, Citation2005). Second, devolution may promote the rivalry between SNGs to establish a good fit between SNG public service provision and SNG wanting to attract mobile aspects of production, leading to economic growth (Boadway & Tremblay, Citation2012; Tiebout, Citation1956).

Economic development means raising the economic welfare of a given nation. More robust economic growth may pave the way for a broader range of welfare services to be provided, enhancing the well-being of a country. An undeveloped economy, for example, will be predominately centered on agriculture and offer minimal social services, such as healthcare and education. Besides, economic development depends on economic growth, since the more goods and services produced, the greater the likelihood that living standards will rise.

Although many scholars have investigated the contribution of fiscal federalism to economic development or growth, they have exhibited implausible results. Studies showed that expenditure decentralization significantly hampered economic growth (e.g. Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a; Davoodi & Zou, Citation1998; Hung & Thanh, Citation2022; Lechner da Silva & De Brito Gadelha, Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Philip & Isah, Citation2012; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2009, Citation2010). A study by Rodríguez-Pose and Ezcurra’s (Citation2010) further considered decentralization of capital expenditure (regional capital expenditure-to-total expenditure ratio) as a fiscal decentralization indicator and found a significant adverse influence on economic growth. Nevertheless, some studies claimed the opposite contribution of expenditure decentralization (e.g. Iimi, Citation2005; Liu, Citation2017; Malik et al., Citation2006; Su et al., Citation2014; Xiao et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, concerning revenue decentralization, there are studies that show that revenue decentralization adversely contributes to economic growth (e.g. Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a; Hung & Thanh, Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2006; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2010). On the contrary, other studies showed a positive influence of revenue decentralization on economic growth (Liu, Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Osmani & Tahiri, Citation2022; Philip & Isah, Citation2012; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2009; Su et al., Citation2014; Xiao et al., Citation2022). Moreover, some studies found an insignificant contribution of expenditure decentralization (e.g. Blöchliger et al., Citation2013; Syamsul, Citation2003). Similarly, some studies demonstrated an insignificant contribution of revenue decentralization (e.g. Baskaran & Feld, Citation2013; Blöchliger et al., Citation2013). As a result, the study claimed the subsequent two hypotheses:

H1: Expenditure decentralization has a statistically significant contribution to economic development.

H2: Revenue decentralization has a statistically significant contribution to economic development.

2.2.2. Fiscal incentives and economic development

Fiscal incentives have recently caught the attention of public finance economists and governments as a vital measure for enhancing economic growth and development. According to Jin et al. (Citation2005), the association between the fiscal incentives of SNGs and development is determined as a function of the SNG’s policies. The fiscal incentives technique explains how the fiscal incentives of subnational political authorities affect their policy choices and their jurisdiction’s economic performance (Jin et al., Citation2005).

In the SGFF, authors like Wingiest (Citation2009) argue that in the presence of soft budget limitations, local government politicians and bureaucrats are encouraged to externalize their weaknesses in collecting revenues to the shared central government pool. Local government maximizes revenue to spend on public investment, which can aid the regional economy to flourish. Therefore, SGFF stresses the benefits of fiscal incentives, the SNG’s officials’ motive, and the effort to collect taxes to make public investments for local economic prosperity.

The SNG’s budgetary capacity is enhanced by such economic expansion; this view supports local government competitiveness through successful actions that contribute to economic advancement. Economic and political pressure highly affects subnational government choices for expenditure and revenue items. However, the fiscal federalism study must often pay more attention to the mix of subnational expenditure by government and economic function. Public finance concerns highly recommend that policies intended for public service provisions, like infrastructure, health, and education, sensitive to SNG circumstances are more promising to foster economic development than policies decided and controlled at the center.

Despite its theoretically underpinning importance, scholars should have noticed fiscal incentive variables while studying the nexus between fiscal federalism and economic development. Therefore, there needs to be more research that scrutinizes the influence of fiscal incentives on economic growth. For example, Lin and Liu (Citation2000) have found that fiscal incentives enhance economic growth. Besides, Siliverstovs and Thiessen (Citation2015), utilizing the revenue retention rate (a portion of a single extra unit of tax revenue that an area keeps for its government expenditures), considered fiscal incentives as a gauge of fiscal decentralization. The study results exhibited that fiscal incentives significantly fostered economic growth. Based on this rationale, the study presented the hypothesis as follows:

H3: Fiscal incentives have a statistically significant contribution to economic development.

2.2.3. Moderating the role of macroeconomic instability

The traditional role of the central government in stabilizing economies has mainly been overlooked due to concerns about SNG jurisdictions having autonomous regulation over their money supplies, open economies in SNG, and undesirable deficit finance policies (Beier & Ferrazzi, Citation1998). The decentralized government may play a more prominent stability role in industrialized economies, and this is becoming more widely acknowledged. In developing nations, stabilization is still a legitimate role for the national government. It is due to severe macroeconomic fluctuations, particularly in agricultural countries, and being heavily dependent on external resources.

A stable macroeconomic environment encourages a solid financial system and markets, allowing for the smooth transfer of funds between investors and savers and promoting economic growth (Khalid, Citation2017). Consequently, macroeconomic stability is required to achieve sustained economic growth for a longer period of time. Siddik (Citation2023) points out that social and physical infrastructure determine the economic growth trajectory. High macroeconomic instability generally makes allocating resources effectively and lowering investment rates difficult (Siddik, Citation2023). Therefore, increased macroeconomic instability could be interpreted as an indication that the pertinent government is no longer in charge of overseeing the economy.

The literature anticipates a possible direct connection between decentralization and economic development. However, it is still being determined whether such a link may have empirical support in the model that considers and states the indirect influence of fiscal decentralization on economic development (Martinez-Vazquez & McNab, Citation2003). Scholars overlooked determining if fiscal decentralization affects economic development directly or indirectly through the macroeconomic instability channel.

The MI, which represents the macroeconomic state of several nations or areas within a single nation, is a summation of the SNG unemployment rate and inflation rate (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a). MI is, therefore, helping to gauge the nation’s economic health. A rise in the MI demonstrates the prevalence of a nation’s declining economic and social conditions. The MI is employed in this context to quantify the economy’s health, demonstrating a nation’s state (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a). In line with the above contentions, the study proposed the subsequent three hypotheses:

H4: Macroeconomic instability moderates the connection between expenditure decentralization and economic development.

H5: Macroeconomic instability moderates the connection between revenue decentralization and economic development.

H6: Macroeconomic instability moderates the connection between fiscal incentives and economic development.

3. Research method

There are two essential techniques for structural equation modeling (SEM): covariance-based (CB-SEM) and variance-based partial least squares (PLS-SEM) (Bushashe, Citation2023). PLS-SEM is undertaking considerable advance, and assuming the complexity of the model and the scarcity of full-fledged literature, it is a suitable choice (Hair et al., Citation2017). To test hypotheses, scholars frequently utilize the statistical method PLS-SEM to look at the connections between latent variables and their constructs. It may minimize model errors by looking at numerous variables at once and can also spot essential relationships between variables. It is a regression-based method that discovers the linear associations among numerous predictor constructs and a single or numerous predicted constructs (s) (Hair et al., Citation2021).

Unlike CB-SEM, which entails strict statistical assumptions, PLS-SEM is a flexible modeling technique with fewer rigid assumptions on the data (Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2015). This method is nonparametric, suggesting that it requires no supposition for the data distribution (Hair et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, first-generation statistics, such as panel regressions, do not permit the use of multiple indicators for single constructs; do not permit the use of multiple indicators for single constructs. Instead, it forces the study to compute the average to accomplish the model estimations. However, the second-generation statistics, i.e. PLS-SEM, help to employ multiple indicators for each construct, such as expenditure decentralization, revenue decentralization, and economic development.

Moreover, it enhances estimation results by allowing the execution of measurement and structural path analysis models simultaneously. PLS-SEM is a novel methodological approach in research. In addition to testing concepts emanating from a well-developed theory, it allows for exploring the link between concepts that have an insufficient theoretical base. The present study reaps this benefit by examining the moderating role of macroeconomic instability. Because, while discussing the link between fiscal federalism and economic development, it is inadequately embodied in the fiscal federalism theory. The SmartPLS 4 software makes it simple to check the role of moderating variables. Accordingly, the present study polled the data as a cross-section to reap the advantage of PLS-SEM, similar to a study by Bushashe (Citation2023).

3.1. Sample and data

Secondary data is increasingly available to analyze real-world events. The study collected relevant secondary data from the Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperatives (MoFEC). The unit of analysis for the current research is the nine SNGs and one city administration over the period 2005–2018. Therefore, the study sample size is 140 (Ten SNGs × 14 years = 140) ().

Table 1. Operationalization of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive

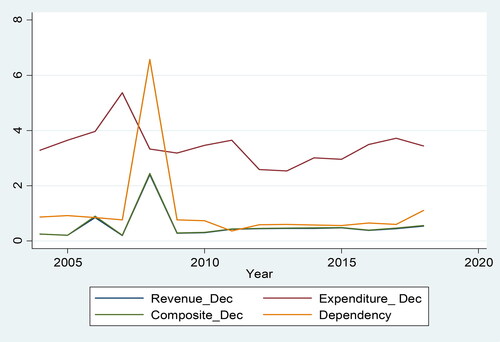

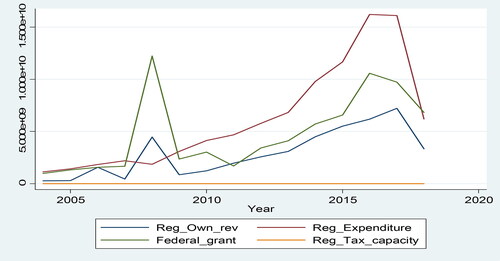

shows that the decentralization of revenue is very low relative to expenditure; thus, it shows the SNG’s high reliance on federal transfers. Therefore, it implies a high centralization of revenue and a high reliance on the SNG for transfers from the federal government. also confirms this condition.

Figure 3. Trends of expenditure, own revenue, grants, and tax capacity.Source: Authors’ Computation (2023).

shows that, compared to changes in revenue-raising capacity, high expenditure needs are increasingly changing at a high speed. Thus, it indicates the existence of fiscal disincentives in the regional government, meaning there is a feeble revenue collection motive and a weak link between revenue and expenditure.

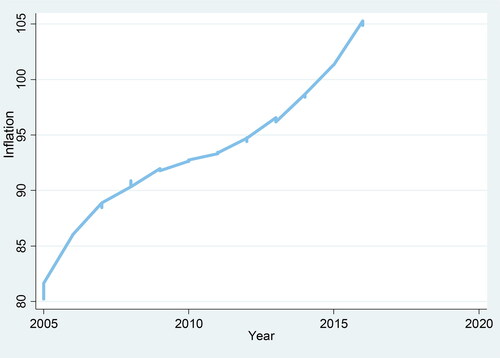

4.1.1. Macroeconomic stability (inflationary pressure)

There is no single definition of macroeconomic stability, as it encompasses healthy fiscal policies, price stability, viable debt proportion, private segment balance sheets, a healthy community, and a well-functioning economy (Ocampo, Citation2008). The inflationary pressure can also determine whether the economic system operates well. Macroeconomic stability relied on the SNG’s fiscal condition, which is subject to federal grants. It is problematic as SNG has not executed initiatives to increase revenue as a result of their reliance on federal grants (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a) ().

4.2. Measurement model evaluation

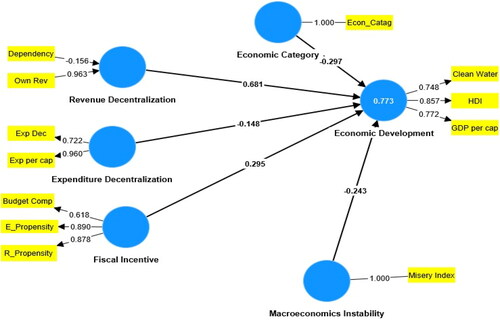

Measuring validity is a form of validity check on the measuring capabilities of latent (unobservable) entities. In PLS-SEM, evaluation of the measurement model comprises specific indicator reliability, internal consistency, discriminant validity, and convergent validity ().

4.2.1. Indicators’ reliability

Reflective and formative models are the two types of measuring models. Indicator dependability shows the variance in an item explained through the construct. Using outer loading values for reflective components with less than 0.7 should be eliminated; if the model’s objective is exploratory, a loading value exceeding 0.4 is plausible (Hair et al., Citation2021). When two or more predictors in a model have a high association with one another, this condition is known as multicollinearity. To be free from the collinearity problem, the variance inflation factor (VIF) needs to be < 5 (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

As shown in and , except for the budget comp item (0.618), all items of the variables have an outer loading above 0.7. Since the loading >0.4 is tolerable for an exploratory study, the study retained the Budget Comp indicator, which has an outer loading of 0.618.

Table 2. Inspecting of construct indicators.

presents outer VIF values <5 in the model, suggesting a tolerable multicollinearity requirement level. Thus, the model has no collinearity problems.

4.2.2. Construct-level reliability

According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), construct-level reliability ensures that items belonging to the same constructs have a strong association. PLS-SEM utilized Cronbach’s alpha to gauge internal consistency reliability in the study; however, it inclines to offer a rigid measurement, and composite reliability appraises how successfully the variable was estimated over its specified measures (Hair et al., Citation2017).

As suggested by the literature, shows all constructs in the study have Cronbach alpha and composite reliability values > 0.7; thus, the study confirmed construct validity.

Table 3. Constructs validity analysis.

4.2.3. Checking discriminant validity

The Fornell-Larcker criterion urges that the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) in each construct may verify discriminant validity if this value is higher than other association values among the constructs (Garson, Citation2016; Hair et al., Citation2017). PLS-SEM employed heterotrait-monotrait ratios (HTMT) to appraise discriminant validity; the mean score between all item associations across components, in contrast to the mean of the average associations for items used to gauge the similar component, should be <0.85 (Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2021).

indicated that all the values are <0.85; therefore, the model validated the discriminant validity.

Table 4. Scrutiny of discriminant validity.

4.2.4. Convergent validity

To check convergent validity, which evaluates if the latent constructs are well signified by their manifest (observable) items, the individual construct’s AVE is assessed; the AVE value >0.5 is acceptable (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Thus, as indicated in , all AVE values exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.5, so convergent validity is confirmed.

4.2.5. Assessing the formative measurement model

All constructs in the model are not mandatory to be reflective measurements. A formative measurement model poses difficulties in scrutinizing indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, and discriminant validity because the formative indicators are not highly associated together (Hair et al., Citation2021). Instead, the research analyzed the outer weight of the constructs, convergent validity, and collinearity. Since the outer weights are significant, it confirms the indicators’ reliability for the formative construct. shows that the VIF values among the formative and other constructs in structural paths in the SEM are < 5, which is a suggested rule of thumb for multicollinearity. Thus, it confirmed convergent validity.

Table 5. Inspecting path coefficients.

4.3. PLS-SEM structural model evaluation

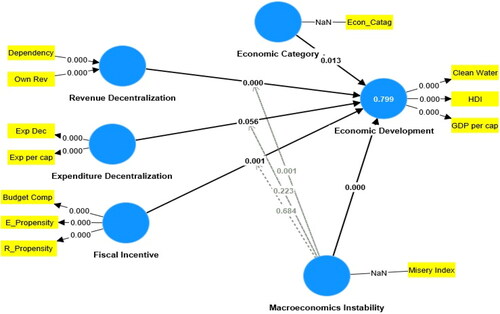

A structural (inner) regression model connects exogenous variables, moderator factors, and endogenous variables. The inner structural model is shown in .

4.3.1. Coefficients of the determinant and predictive relevance

Checking the R2 value illustrates the overall influence of each endogenous variable and its indicators on the exogenous variable and its indicators in the inner model. A model with coefficients of the determinant (R2) of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 is rated as strong, modest, and weak, respectively (Garrison, 2016; Henseler et al., Citation2015). presents the R2 > 0.67; therefore, the R2 of the model is high. It implies that the model has highly robust estimating accuracy.

Predictive relevance (Q2) represents the predictive relevance of PLS-SEM. The Q2 values greater than zero indicate that the SEM has predictive accuracy for a given dependent variable (Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2021). In contrast, values equal to zero and lower indicate a lack of predictive relevance. Values of Q2<0.02, 0.02<Q2≤ 0.15, 0.15>Q2≤0.35, and Q2 >0.35 indicate exogenous variables have a proportion of minor, average, or substantial predictive accuracy of endogenous variables. shows that the Q2 value of the study is 0.748; therefore, the SEM has a higher predictive relevance for the endogenous variable.

4.3.2. Assessing path coefficients significance

Inspecting path (β) coefficients explicates the effect of one construct on other constructs. The bootstrap procedure enables the predicted coefficients to be verified for significance. The technique generates numerous predetermined numbers of bootstrap samples; a 5000-resample sample is recommended (Hair et al., Citation2017).

shows that expenditure decentralization (significance level = 10%; β = −0.207) has significantly hampered economic development. However, revenue decentralization (significance level = 1%; β = 0.703) and fiscal incentives (significance level = 10%; β = 0.276) significantly boost economic development. Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are supported.

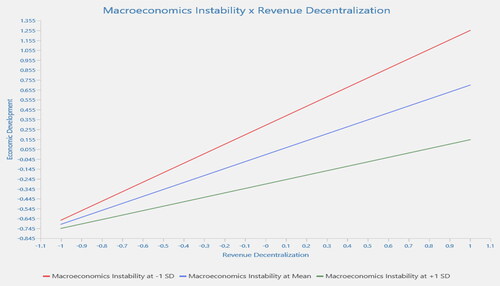

On the other hand, it is possible to assess the role of a third variable, Z, on the connection between variables X and Y utilizing the analysis of the moderating effect approach. Moderation investigates how an effect happens instead of examining a connection between these other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2021). Moderates may affect the relationship’s strength and brittleness, and nature can be affected by moderators. As demonstrated in , macroeconomic instability (significance level = 5%; β = −0.255) significantly moderates the association between revenue decentralization and economic development. This relationship becomes weaker when macroeconomic instability increases (i.e. negative interaction effect).

also displays that the positive link between revenue decentralization and economic development was lower when there was a high degree of macroeconomic instability. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is supported. However, hypotheses 4 and 6 are not supported because macroeconomic instability insignificantly moderates the connection between expenditure decentralization, fiscal incentives, and economic development. Finally, concerning the control variable, the economic category (significance level = 5%; β = −0.241) has a significant adverse contribution to economic development. Therefore, SNGs in Ethiopia fall under the category of emerging states’ economies and have low economic development compared to SNGs categorized under advanced states’ economies.

5. Discussion

The study aims to look into the causal connections between factors related to fiscal federalism and economic development. Besides, it examines the moderating role of macroeconomic stability on the effect of fiscal federalism on economic development.

The study result confirms scholars’ findings that expenditure decentralization has adversely affected economic growth (Davoodi & Zou, Citation1998; Hung & Thanh, Citation2022; Lechner da Silva & De Brito Gadelha, Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Philip & Isah, Citation2012; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2009, Citation2010). However, it contradicts studies that showed a positive influence of expenditure decentralization on economic growth (Iimi, Citation2005; Liu, Citation2017; Malik et al., Citation2006; Gisore, Citation2022; Su et al., Citation2014; Xiao et al., Citation2022). It also disagrees with studies that revealed expenditure decentralization insignificantly affects economic growth (e.g. Blöchliger et al., Citation2013; Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a; Syamsul, Citation2003). On the other, hand, the findings do not support those studies that disclose that revenue decentralization significantly hampers economic growth (Bushashe & Bayiley, Citation2023a; Hung & Thanh, Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2006; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2010). Nevertheless, it verified studies that discovered a significant positive effect (e.g. Liu, Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Osmani & Tahiri, Citation2022; Philip & Isah, Citation2012; Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2009; Su et al., Citation2014; Xiao et al., Citation2022). Moreover, it is odd with studies that prove the insignificant contribution of revenue decentralization to economic growth (e.g. Baskaran & Feld, Citation2013; Blöchliger et al., Citation2013).

Furthermore, Lin and Liu (Citation2000) and Siliverstovs and Thiessen (Citation2015) verified the study findings on fiscal incentives, which revealed that fiscal incentives significantly enhance economic growth. Thus, it indicates the improvement in the SNGs motives and efforts to raise their revenue to finance expenditure needs is important because it enhances economic development. The SGFF contends that SNGs with higher tax autonomy typically have more incentives to raise their revenue by promoting SNG economic development (Weingast, Citation2009). Accordingly, the study findings on revenue decentralization and fiscal incentives verify SGFF.

Besides, literature has highlighted the role of fiscal federalism in enhancing macroeconomic stability regarding SNG economic development. Stable macroeconomic conditions encourage investment, financial development, integration, and globalization, which could act as possible channels for economic growth.

However, inconsistent with the literature, the finding showed that macroeconomic instability has an insignificant moderating role in the two variables (i.e. expenditure decentralization and fiscal incentive) effect on economic development. In other words, it weakens the favorable influence of revenue decentralization on economic development. It can be due to many reasons. For instance, the SNGs cannot influence employment rates and prices, as they have restricted possession of finances and have restricted openness to economic activity.

The previous discussion showed that, as many empirical studies have evidenced, let alone different country contexts, the findings of fiscal federalism and economic development may contradict each other within single country contexts. As a result, it is difficult to make a complete comparison of a single study’s findings with those of other studies; however, it is possible to make simple comparisons. Considering the expenditure side of Ethiopian fiscal federalism’s effects, the present study made a simple comparison of the findings with those of some developing countries. Consequently, studies showed that the expenditure decentralization effects on SNGs economic development diverge from those of developing countries, for example, Mose (Citation2021) in Kenya, Malik et al. (Citation2006) in Pakistan, Su et al. (Citation2014) in Vietnam, Liu (Citation2017) in Taiwan, and Xiao et al. (Citation2022) in China.

The above quoted difference may be due to three reasons. First, most previous studies investigated fiscal federalism using a single indicator for each variable. This makes the studies a piecemeal representation of each fiscal federalism dimension. Second, the methodology of some studies may be inappropriate to yield robust and plausible results. By utilizing the PLS-SEM procedure, the present study alleviates the problem. In addition to incorporating multiple indicators for each construct, it allows for the incorporation of moderating and control variables, and the findings are subsequently more robust and reliable than those of the previous studies. Third, it may be due to Ethiopia’s unique ethnic-based federalism arrangement, which brought so many economic and social evils to the nations and placed fences that blocked smooth economic and social interactions and coexisted among citizens in the country.

Moreover, in some studies, the results of either revenue or expenditure decentralization can also be inconsistent with the same country context, despite the time periods. For instance, in the same study context, i.e. Ethiopia, the present expenditure decentralization finding is at odds with the study finding by Bushashe and Bayiley (Citation2023a). In addition to the above reasons, this difference may be engendered since the SNGs of Ethiopia fall into two economic categories (emerging and advanced). The study utilized the economic category of SNGs as a control variable to improve the statistical robustness. The finding validated that, compared to emerging SNGs, advanced SNGs exhibited more economic development.

In summary, although Ethiopia has executed fiscal federalism that has reformed the country’s political, administrative, and economic framework, it hinders the fiscal federalism of the country from reaping the advantages of decentralization. The ethnic-based arrangement of the fiscal federalism design provokes ethnic conflicts in many areas of the country. Accordingly, it adversely affects economic activities since it may lead to low private investment. It may be due to the rampant expenditure behaviors of SNGs and high corruption due to the low transparency and accountability in SNG financial decisions and economic activities. Consequently, fiscal federalism in Ethiopia has a detrimental effect on SNGs’ economic development.

6. Conclusion

An exhaustive investigation has contributed to the complex linkages between fiscal federalism and economic development, but convincing proof has yet to emerge. Some studies have shown that fiscal federalism negatively influences economic growth, while others have found the opposite result. As a result, the empirical studies are inconclusive and less credible, necessitating further research. Using PLS-SEM, the study analyzed the connection between fiscal federalism and economic development, utilizing data over the years between 2005 and 2018.

Out of the first six hypotheses suggested, the study supported four of them, but the remaining two hypotheses were not significant. The study indicated that revenue decentralization and fiscal incentives positively affect economic development. The finding on expenditure decentralization departs from the expected assumptions of FGFF and SGFF. Because of Ethiopia’s fiscal federalism, the prime emphasis is on developing IGT programs rather than improving decentralized revenue sources. As a result, SNG spending does not consider its own revenue. It may encourage SNGs to compete for transfers and rampant spending, making expenditure decentralization hamper economic development. Besides, enhancing citizens’ health and education is a priority, as it is a way of achieving continuous development.

The findings exposed that macroeconomic instability negatively moderates the indirect influence of revenue decentralization on economic development. Nevertheless, it showed no effect of the other two fiscal federalism variables on economic development. Moreover, the control variable (i.e. economic category) indicates that SNGs in emerging economies have less economic development than SNGs in advanced economies. It can be due to the divergence between the two SNGs’ economic categories in fiscal and institutional capacity.

Fiscal federalism has been implemented within the bounds of political requirements in Ethiopia. The exercise changed the nation’s political and economic climate. The ethnic-based political barrier creates administrative, institutional, and political constraints that prevent the country from realizing its full economic potential. It contrasts with a system where resources may readily move across areas. Economically speaking, when ethnicity becomes a factor in political and economic decision-making, agents are forced to operate more in particular locations than others. Investments in other SNGs come with particular political concerns.

The SNGs’ insufficient fiscal capacity engendered a high IGT dependency; it made the SNGs easily exposed to central government pressure and inefficient execution of decentralization functions. Besides, the reckless spending behaviors of SNGs are the main reason for fueling macroeconomic instability, which in turn has a detrimental effect on economic development.

Broadly speaking, in Ethiopia, the SNGs are accountable for the execution of economic and social development policies and for maintaining public order. The inter-governmental fiscal relationships of the country highly decentralize expenditure functions. Nevertheless, it established highly centralization of revenue since the constitution entitles lucrative revenue sources to the federal government, which accounts for a large share of the total revenue of the country. Thus, it is vital to give much attention to expenditure decentralization because it provides substantial autonomy for exercises. Nevertheless, revenue decentralization is having a promising influence on development, but due to limited revenue bases, the SNGs still have inadequate room for maneuvering revenue decentralization to achieve the intended objectives.

Based on the findings, the present study provides the following four essential lessons for policymakers and other stakeholders:

First, the study findings showed vital implications for policymakers: the federalism of Ethiopia is against its goal. A vital decentralization policy design issue is how lower-level governments are financed. the determination of the revenue and local public goods provisions determined concurrently. reaping the benefits of efficiency originated from the information advantage of SNGs about citizen preferences. Second, decentralization on the expenditure side should accompany good decentralization on the revenue side. Besides, SNGs should rely primarily on their revenue sources instead of IGTs. Third, policymakers should implement possible policy instruments that aid SNGs to stimulate a pro-growth policy. Fourth, financial autonomy is a crucial component of fiscal federalism to understand the macroeconomic stabilizing effect of revenue devolution. SNGs should have access to sufficient resources to implement their dispensed responsibilities and be held accountable for their actions.

Public Interest Statement CSS Rev 4 ED.docx

Download MS Word (12.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The researchers received no funding for the study. Besides, the researchers stated that there was no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Million Adafre Bushashe

Million Adafre Bushashe is a lecturer at the Department of Management, Mizan-Tepi University, Ethiopia. He has a BA in Management, a Master’s degree in Business Administration, and is a Ph.D. candidate in Public Policy and Management at Addis Ababa University. His research interests include fiscal federalism, economic development, stability, social welfare, corporate finance, and governance.

Yitbarek Takele Bayiley

Yitbarek Takele Bayiley is an associate professor at Addis Ababa University. He has a Master’s degree in business administration, an MSc in economics, and a Ph.D. in management.

References

- Baskaran, T., &Feld, L. P. (2013). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in OECD countries. Public Finance Review, 41(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142112463726

- Beier, C., &Ferrazzi, G. (1998). Fiscal decentralization in Indonesia: A comment on smoke and lewis. World Development, 26(12), 2201–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00116-8

- Bird, R. M. (1999). Threading the fiscal labyrinth: Some issues in fiscal decentralization. Tax Policy in the Real World, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511625909.009

- Blöchliger, H., Égert, B., & Fredriksen, K. (2013). Fiscal federalism and its impact on economic activity, public investment and the performance of educational systems. (OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1051). OECD Publishing.

- Boadway, R. (2005). The vertical fiscal Gap: Conceptions and misconceptions: In Canadian FISCAL ARRANGEMENTS. In H. Lazar (Ed.), What works, what might work better (pp. 51–80). McGill –Queens’s Pres.

- Boadway, R., & Tremblay, J. (2012). Reassessment of the Tiebout model. Journal of Public Economics, 96(11–12), 1063–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.01.002

- Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. (1980). Power to tax: Analytical foundations of a fiscal constitution. Cambridge University Press.

- Bushashe, M. A., & Bayiley, Y. (2023b). The effect of fiscal decentralization on economic growth in sub-national governments of Ethiopia: A two-step system general methods of moments (GMM) approach. Public and Municipal Finance, 12(2), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.21511/pmf.12(2).2023.03

- Bushashe, M. A. (2023). Determinants of private banks performance in Ethiopia: A partial least square structural equation model analysis (PLS-SEM). Cogent Business & Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2174246

- Bushashe, M. A., & Bayiley, Y. (2023a). Fiscal decentralization and macroeconomics stability nexus: Evidence from the sub-national governments context of Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2244353

- Bushashe, M. A., & Bayiley, Y. (2023c). Fiscal federalism and public service provision in Ethiopia: A mediating role of sub-national governments capacity. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2255496

- Davoodi, H., & Zou, H. (1998). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: A cross-country study. Journal of Urban Economics, 43(2), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1997.2042

- Garson, G. D. (2016). Partial least squares regression and structural equation models. Statistical Associates.

- Gisore, M. (2022). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: The Kenyan experience. Journal of Somali Studies, 9(2), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.31920/2056-5682/2022/v9n2a3

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. Springer.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Henseler, J.,Ringle, C. M., &Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hung, N. T., & Thanh, S. D. (2022). Fiscal decentralization, economic growth, and human development: Empirical evidence. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2109279

- Iimi, A. (2005). Decentralization and economic growth revisited: An empirical note. Journal of Urban Economics, 57(3), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2004.12.007

- Jin, H., Qian, Y., & Weingast, B. R. (2005). Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9–10), 1719–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.008

- Khalid, A. M. (2017). Combining macroeconomic stability and micro-based growth: The South East Asia/Asia Pacific experience. The Lahore Journal of Economics, 22(Special Edition), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.35536/lje.2017.v22.isp.a6

- Lechner da Silva, Á., & De Brito Gadelha, S. R. (2022). Fiscal federalism, fiscal decentralization, and economic growth in Brazil: 1954 - 2018. Cadernos De Financas, 22(02). https://doi.org/10.55532/1806-8944.2022.182

- Lin, J., & Liu, Z. (2000). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/452488

- Liu, L. C. (2017). Fiscal decentralization, public governance, and economic performance examination of two PLS-SEM models. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 13(2), 55–72. http://www.tfd.org.tw

- Malik, S., Hassan, M., & Hussain, S. (2006). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 45(4II), 845–854. https://doi.org/10.30541/v45i4IIpp.845-854

- Martinez-Vazquez, J., & McNab, R. M. (2003). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth. World Development, 31(9), 1597–1616. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-750x(03)00109-8

- Mose, N. (2021). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3988647

- Nguyen, P. D., Vo, D. H., Ho, C. M., & Vo, A. T. (2019). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth across provinces: new evidence from Vietnam using a novel measurement and approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(3), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12030143

- Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal decentralization. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

- Oates, W. E. (2005). Toward a second-generation theory of fiscal federalism. International Tax and Public Finance, 12(4), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9

- Ocampo, J. A. (2008). A broad view of macroeconomic stability. The Washington Consensus Reconsidered. 63–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199534081.003.0006

- Osmani, R., & Tahiri, A. (2022). Fiscal decentralization and local employment growth: Empirical evidence from Kosovo’s municipalities. Series V - Economic Sciences, 63–74. https://doi.org/10.31926/but.es.2022.15.64.1.7

- Philip, A. T., & Isah, S. (2012). An analysis of the effect of fiscal decentralization on economic growth in Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(8), 141–149. fromhttp://www.ijhssnet.com

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ezcurra, R. (2010). Is fiscal decentralization harmful to economic growth? Evidence from the OECD countries. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(4), 619–643. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq025

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Krøijer, A. (2009). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in Central and Eastern Europe. Growth and Change, 40(3), 387–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.2009.00488.x

- Siddik, M. N. (2023). Does macroeconomic stability promote economic growth? Some econometric evidence from SAARC countries. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 7(3), 358–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEB-05-2022-0052

- Siliverstovs, B., & Thiessen, U. (2015). Incentive effects of fiscal federalism: Evidence for France. Cogent Economics & Finance, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1017949

- Su, D. T., Hoai, B. T., & Lam, D. M. (2014). The nexus between fiscal policy and sustained economic growth. Vietnamese Journal of Economic Development, 280, 2–21.

- Syamsul, T. M. (2003). Fiscal decentralization and economic development: A cross-country empirical study. Forum of International Development Studies, 8(24), 245–271.

- Tesfai, G. (2015). The practice of fiscal federalism in Ethiopia: A critical assessment 1991-2012. An institutional approach [Doctoral dissertation, University of Fribourg].

- Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/257839

- Wingiest, B. R. (2009). Second generation fiscal federalism: The implications of fiscal incentives. Journal of Urban Economics, 65(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.12.005

- Xiao, Q., Lin, T., & Ma, Y. (2022). Fiscal decentralization, economic policy uncertainty, and high-quality economic development: An empirical study based on systematic GMM [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Science, Information Engineering and Digital Economy (CSIEDE 2022). https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-108-1_64

Appendix

Table A1. Weights of indicators for special subsidies of emerging SNGs.