Abstract

Teacher self-efficacy is one of the most critical factors influencing students’ learning outcomes. Accordingly, school reforms globally have advocated professional learning communities (PLCs) as a school-level approach for improving teachers’ instructional practices. This inquiry tested the influence of PLCs on teaching efficacy beliefs of Economics teachers. Survey data were collected from 97 Economics teachers in senior high schools of Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana, using adapted Professional Learning Community Assessment-Revised (PLCA-R) and Teacher Sense of Efficacy scale (TSES). The data were analysed using descriptive statistics and structural equation modelling. The findings showed that Economics teachers had high level of teaching efficacy. They were moderately engaged in the implementation of PLCs. The research also revealed that shared and supportive leadership (SSL) had statistically significant effect on teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs. Further, it was discovered that shared value and vision (SVV), collective learning applications (CLA), shared personal practice (SPP), supportive conditions-relationships (SCR) and supportive conditions-structures (SCS) had positive effects on teachers’ teaching efficacy. The study recommended that the Ministry of Education (MoE) and school administrators should continue to provide positive school culture that builds teachers’ teaching efficacy and engagement in PLCs.

1. Introduction

Teachers play important and central roles in Ghana’s education system. Teacher teaching self-efficacy as a factor in school improvement has been of interest for many years (Daly, Citation2010; Elmore, Citation2007). Drawing from the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Bandura (Citation1994) defines self-efficacy as ‘people’s beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives’ (p. 71). Relatedly, teacher teaching efficacy belief is ‘the extent to which the teacher believes he or she can affect student performance’ (Berman et al., Citation1977, p. 137). This belief results in an individual teacher’s decision to meet the demands of the current teaching task (Agormedah et al., Citation2022). Many studies have identified diverse degrees of teachers’ teaching self-efficacy beliefs. For example, Arko (Citation2021) in Ghana established that Social Studies teachers exhibited high teaching self-efficacy. Similar findings were reported among teachers in the USA (eg Hodges et al., Citation2016), Turkey (eg Kabaoglu, Citation2015) and Kenya (eg Wang’eri & Otanga, Citation2014). Conversely, teachers with a moderate level of teaching self-efficacy beliefs were reported in Indonesia (eg Susilanas et al., Citation2018), Malaysia (eg Abdullah & Kong, Citation2016; Yusof & Nor, Citation2017), Ghana (eg Agormedah et al., Citation2022) and Tanzania (Jumanne, Citation2012). Extant researchers have revealed that teachers with a high level of teaching efficacy beliefs increase student academic achievement (eg Hattie, Citation2012; Leithwood et al., Citation2020; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, Citation2004), use productive teaching practices (Goddard et al., Citation2000; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, Citation2004); ensure quality instruction (eg Holzberger et al., Citation2013; Klassen et al., Citation2011) and positively influence curriculum implementation (Agormedah et al., Citation2022; Fullan, Citation1994; Snyder et al., Citation1992).

While the existing literature on teacher teaching efficacy beliefs has intensively focused on the concept itself, its consequences for teaching and learning (Soodak & Podell, Citation1996) and other behavioural outcomes of teachers, less is known about effective approaches and strategies that could enhance teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs for teaching (Klassen et al., Citation2011). One critical school-level approach identified as influencing teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs is professional learning community (PLC) (Avalos, Citation2011; Guskey, Citation2002). PLC represents the institutionalisation of a focus on continuous improvement in staff performance and student learning. DuFour et al. (Citation2010) state that a PLC consists of ‘an ongoing process in which educators work collaboratively in recurring cycles of collective inquiry and action research to achieve better results for the students they serve’ (p. 18). They are communities where teachers cooperate to improve their school practices and solve the problems encountered in education, in line with a common vision (DuFour, Citation2004; Hord, Citation1997). It is one method of professional development that supports teachers’ growth, collaboration and student outcomes (Doppenberg et al., Citation2012). It is an effective school framework to improve educational quality and teachers’ collective work and collaboration (Hord, Citation1997; Seo & Han, Citation2012). It assumes that quality professional development activities improve teacher knowledge and instructional practices (R. D. Goddard & Goddard, Citation2001).

The effect of PLCs on teachers’ teaching efficacy can be related to the SCT. Bandura and Walters (Citation1977) explained social learning theory in terms of the interaction among personal, behavioural and environmental. From SCT perspective, teachers’ teaching self-efficacy beliefs are formed through four main sources: enactive mastery experiences (experiences of performance), vicarious experiences (observing models, comparison with others), verbal persuasion (feedback about performance) and physiological states (emotional and biological indicators) (Bandura, Citation1997). Accordingly, we theorised that teachers’ PLC enhances efficacy beliefs through the four sources (enactive mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and physiological states). We believe that personal factor (eg self-efficacy) and environmental influences (eg PLC and collaborative climate) encourage the behaviours that lead to professional growth and enhanced teaching practice. But these behaviours also reciprocally influence personal factors (ie teaching efficacy). According to Bandura (Citation1997), all learning from direct experience occurs vicariously through observations of others. In the context of a PLC, teachers learn the worth of collaboration and sharing ideas by seeing the successes of their peers on a team. Bandura (Citation1997) states that various professional development activities carried out in PLCs develop the resources to nurture teacher efficacy. For example, they build trust and dependence through vicarious and mastery experiences during collaborative meetings (Bandura, Citation1998). Also, feedback from peers is one example of social persuasion during PLCs that can improve teacher efficacy (Y. L. Goddard et al., Citation2007). Social cognitive theorists regard PLC activities such as continuous professional development programmes (CPD) as a key component for increasing self-efficacy (Harris, Citation2003).

A growing number of empirical studies support that PLCs could be an effective approach to enhancing teachers’ efficacy for teaching (Doğan & Yurtseven, Citation2018; Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, Citation2009). Similarly, research argues that the perception of a higher teacher PLC positively affects collective teacher efficacy (Hardin, Citation2010; J. C. Lee et al., Citation2011; Sawyer & Rimm‐Kaufman, Citation2007). For example, Yang (Citation2020) in the USA discovered that more PD experience was significantly associated with increased teacher self-efficacy. Gilliam (Citation2020) found that supportive conditions-relationships (SCR) and supportive conditions-structures (SCS) were significant predictors of teacher efficacy. Heaton (Citation2013) also found that PLC variables related significantly to levels of teacher self-efficacy. Shared and supportive leadership (SSL) and SCS were two components of effective PLCs that correlated significantly with teacher self-efficacy. Similarly, Stegall (Citation2011) provides evidence of a positive relationship between classroom-related teacher efficacy components and PLCs. In particular, the PLC component – shared and supportive leadership revealed the largest degree of correlation to the three components of self-efficacy (Stegall, Citation2011). In contrast, Gilliam (Citation2020) found that shared and supportive leadership (SSL), shared values and vision (SVV), collective learning and application (CLA) and shared personal practice (SPP) were non-significant predictors of teacher efficacy. Also, Shetzer (Citation2011) revealed that dimensions of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs were not correlated at all to the dimensions of PLC. From these findings, we speculate that well-functioning PLCs are associated with high teacher efficacy, whereas PLCs that do not function well are associated with low teacher efficacy.

The indispensable role of PLC in teachers’ continuous development promoted several governments across the globe to include PLC in educational reforms (Capili-Balbalin, Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2013). In Ghana, the phenomenon of PLC was formalised in the school system during the 2017 educational reforms. The 2017 educational reform mentions the importance of teachers’ continuous professional learning and suggests that schools should start building PLCs. The 2017 educational reform stipulated that 2 h in every week should be devoted to PLC to improve teachers’ performance and further boost students’ academic achievement (Ministry of Education [MoE], Citation2019). This call by the Government of Ghana and its educational agencies is essential because teachers provide quality education. The quality of the educational system depends on the professional quality of the teachers. Accordingly, teachers must be provided with opportunities to develop their skills and knowledge, to provide quality teaching for their students and help them improve. Besides, initial teacher training alone cannot produce competent teachers who can meet the challenges in the 21st-century classroom (Asare et al., Citation2012). By providing teachers with the opportunities to create and share knowledge and learn among themselves is the right call to ensure high-quality teaching and learning.

Conversely, it appears that since the introduction of PLCs in the school system, no empirical studies have been conducted to ascertain the effectiveness of the PLCs and its effect on teachers’ performance. Informal conversations with some teachers in the Central Region suggest that most schools in Ghana either implement PLCs wrongly from the stipulated tenets or do not implement the PLCs at all. Most teachers are often seen in town during the time scheduled for PLC meetings, whilst those who attend the meetings do not tend to willingly share their classroom challenges to guide discussions in PLCs. Empirical studies linking PLCs to teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs in Ghana are lacking. The studies in Ghana only focused on teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs (Agormedah et al., Citation2022; Arko, Citation2021; Sarfo et al., Citation2015; Yidana & Arthur, Citation2023; Yidana & Ntarmah, Citation2016) and PLCs (Dampson, Citation2021; Soares et al., Citation2020) separately. What remains unknown in Ghana is the influence of teachers’ engagement in PLCs on their teaching efficacy beliefs.

Again, most of the studies on the associations between teachers’ engagement in PLCs and teaching efficacy beliefs were implemented in other jurisdictions like Europe, America and Asian (Chen et al., Citation2020; Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; J. C. Lee et al., Citation2011; Stegall, Citation2011; Weathers, Citation2009; Yada et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). They provided contradictory findings about the effect of PLCs on teaching efficacy due to differences in the statistical tools used in the analysis (Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; Weathers, Citation2009). These studies mainly deployed correlation and regression analysis to establish predictive effect of PLCs on teaching efficacy. However, correlation and regression analyses are limited to fit complex datasets properly like PLCs and teaching efficacy. The PLCs that have been employed in schools within Europe, America and Asia may perform differently from those in Ghana because of different cultures, educational goals and policy contexts. The fact that research has focused on these two concepts underlines the necessity of conducting new studies in different cultures like Ghana. This is because culture is an important factor in the school environment. Examining these two concepts in Ghana will contribute to teacher development literature.

1.1. Research purpose

The current study aims at examining the influence of PLCs and teacher efficacy using structural equation modelling (SEM). Specifically, the current examination ascertains the:

SHS Economics teachers’ level of teaching efficacy,

SHS Economics teachers’ level of engagement in PLCs and

influence of PLCs practices on teaching efficacy beliefs among SHS Economics teachers in the Cape Coast Metropolis.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) has become a major tool for examining and understanding relationships among latent attributes. It is a multivariate statistical analysis technique that is used to analyse structural relationships. Structural equation modelling (SEM) aims at defining a theoretical causal model consisting of a set of predicted covariances between variables and then test whether it is plausible when compared to the observed data (Byrne, Citation2011; Jöreskog, Citation1970; Wright, Citation1934).

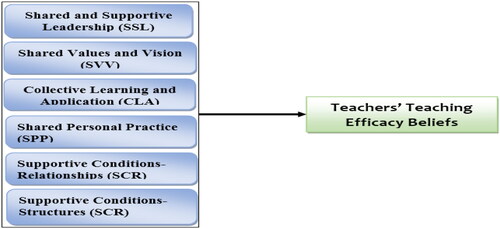

1.2. Conceptual model

shows the conceptual model, which suggests the paths through which the PLC practices influence SHS Economics teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs. For purposes of this study, we focus on SSL, SVV, CLA, SPP, SCR and SCS as components of PLC practices in school as proposed by Olivier and Hipp (Citation2010) and supported by other scholars. We also measured the teaching efficacy of Economics teachers using Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2001). According to the authors, teaching efficacy is a function of student engagement, classroom management and instructional strategies.

2. Research methods

2.1. Research design

Explanatory correlational research design was employed to assess the influence of Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs on their teaching efficacy. Explanatory research is conducted to identify the extent and nature of cause-and-effect relationships between or among variables (Burns & Grove, Citation2005; Pandita, Citation2012). The aim of this research design is to elucidate the relationship between two or more variables (Rashid, Citation2012), which in this case, are the influence of Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs on teaching efficacy.

2.2. Participants

Participants for this study are Economics teachers at senior high schools (SHS) within Cape Coast Metropolis. Census approach was used to involve 133 Economics teachers from 11 SHS offering Economics. The census approach was used because the respondents were few, and it is realistic to include everyone devoid of sampling errors. Most participants were male teachers of Economics (n = 78; 80%). The ages of the teachers ranged from 25 years to 50 years, with a mean age of 35.4 years. The teachers’ teaching experience ranged from 1 year to 20 years, with a mean teaching experience of 8.6 years.

2.3. Instrumentation

A questionnaire was used to collect the data from the Economics teachers. The questionnaire was adapted from Professional Learning Community Assessment-Revised [PLCA-R] (Olivier & Hipp, Citation2010; Olivier et al., Citation2003) and Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale [TSES] (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2001). The PLCs were used as a predictor variable, and TSE was used as an outcome variable.

2.3.1. Predictor variable: PLCs

Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs was measured using PLCA-R which is a 52-question survey instrument that measures staff perceptions of school practices related to six dimensions of a PLC and its related attributes (Olivier & Hipp, Citation2010; Olivier et al., Citation2003). The PLCA-R assessment has been administered to educators across the globe in numerous school districts and at different grade levels. It has assisted educators to determine the strength of practices in their own schools within each dimension. The six sub-scales representing PLC are SSL, SVV, CLA, SPP, SCR and SCS. Each of the dimensions has four items. Some of the questions on the scale include: ‘The school leadership incorporates advice from staff members to make decisions’ (SSL); ‘Decisions are made in alignment with the school’s values and vision’ (SVV); ‘Staff members work together to seek knowledge, skills and strategies to solve problems in the school’ (CLA); ‘Staff members collaboratively review student work to share and improve instructional practices’ (SPP); ‘Staffs exhibit a sustained and unified effort to embed change into the culture of the school’ (SCR) and ‘The school has appealing learning environment, facilities, teaching and learning resources/materials, ICT facilities’ (SCS). Respondents use a six-point Likert scale to indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with each statement. The original scale had internal consistency with the following Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficients: SSL = .94, SVV = .92, CLA = .91, SPP = .87, SCR = .82 and SCS = .88.

2.3.2. Outcome variable: TSE

Economics Teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs was measured with the TSES 12-item short form. The TSES is a measure of teachers’ evaluations of their own likely success in teaching (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2001). The items are grouped into three subscales: (1) efficacy in student engagement (ESE; 4 items), (2) efficacy in instructional strategies (EIS; 4 items) and (3) efficacy in classroom management (ECM; 4 items). Some of the questions on the scale include: ‘I can get through to the most difficult students in the class’ (ESE); ‘I can gauge student comprehension of what you have taught’ (EIS); and ‘I can control disruptive behaviour in the classroom’ (ECM). The items were scored on a six-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ strongly disagree (SD) and ‘6’ strongly agree (SA). The original scale (ie the short form) had Cronbach’s alpha estimates of .81, .86 and .86 for the dimensions of ESE, EIS and ECM, respectively.

2.4. Data collection procedures

Prior to data collection, ethical considerations were followed. An introductory letter was obtained from the Department of Business and Social Sciences Education, University of Cape Coast for data collection. The introductory letter was sent to the heads of the SHS involved in the study to ask for permission to undertake the research in their schools. After approval from the heads, the Economics teachers were contacted and rapport was established with them. Written informed consent forms were given to the respondents who volunteered to participate in the study to sign. The participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Furthermore, they were informed about their willingness to participate in the study or withdrawal from the study at any time. The purpose of research was explained to the participants, and they were informed that the data was for academic purposes. The researchers engaged the services of six research assistants for the entire study. They were thoroughly briefed on all aspects of the instrument, as well as the research ethics. Each of these research assistants was assigned to two different schools offering Economics to collect the data. The research assistants visited all the schools that were sampled and administered the questionnaire. Due to school activities and insufficient time, the Economics teachers were given a week (ie Monday to Friday) to respond to the items on the questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered to 133 Economics teachers from 11 SHS offering Economics in Cape Coast Metropolis using the census approach. Out of 133 questionnaires distributed, 97(73%) of them were returned.

2.5. Data processing and analysis strategy

The data collected was screened and checked for their completeness. The data was processed using SPSS version 25.0 and Smart-PLS version 3.2.7 software. Both descriptive and inferential analyses were performed. Descriptive statistics (ie means, standard deviations, skewness and Kurtosis) for the total score and three sub-scale scores were obtained for both predictor (PLCA-R) and outcome (TSES) variables. The descriptive statistics was used to assess the level of teaching efficacy and perceptions towards PLCs implementation in schools among Economics teachers. To determine the level of teaching efficacy and teachers’ engagement in PLCs, a mean criterion was established based on the six-point Likert scale. Accordingly, a mean score of 1.00–2.99 denotes a low level of teaching efficacy or engagement in PLCs while a mean of 3.00–4.99 and 5.00–6.00 denotes a moderate and high level of teaching efficacy or engagement in PLCs, respectively. Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the relationships among the variables. Lastly, we employed Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) using SmartPLS to determine the relationship among variables. The analysis was performed using 1000 bootstrap samples (Hair et al., Citation2017). The SEM-PLS in this study followed Hair et al. (Citation2017), which includes: evaluation of the measurement model (outer model); (2) evaluation of the structural model (inner model) and (3) hypothesis testing.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

3.1.1. Normality and multicollinearity assumptions

As shown in , the value of skewness (−0.177 to −1.202) and kurtosis (0.092 to 1.513) of the variables were within the acceptable range of 2 and −2, indicating that the data was normally distributed (George & Mallery, Citation2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Furthermore, in , multicollinearity of each of the latent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) for both the outer and inner models. For both outer (1.12–2.58) and inner (1.42–2.41) models, no multicollinearity problems were found as all VIFs were below 3.3 or 5 (Hair et al., Citation2011; Kock, Citation2015; Kock & Lynn Citation2012). This result showed that the model satisfied the collinearity criteria and valid for further analysis.

Table 1. Normality and collinearity of latent variables.

Table 2. Assessment of outer model: construct reliability and convergent validity.

3.1.2. Test of the measurement model (outer model)

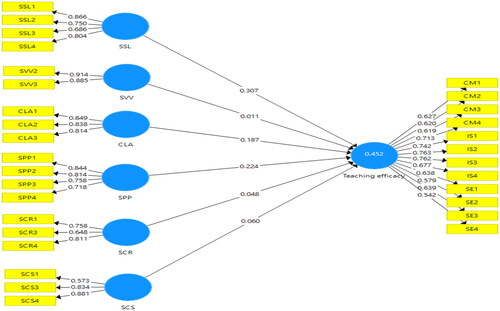

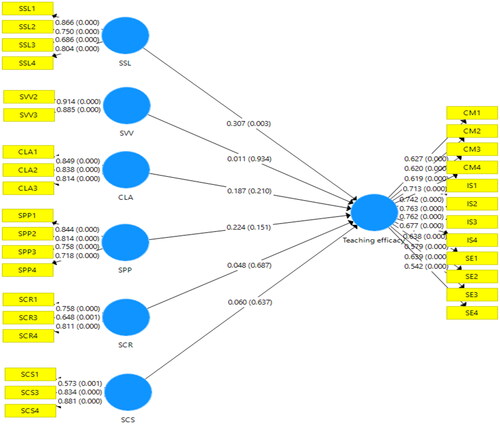

Measurement biases were assessed through the test of construct reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity of the reflective measures of the latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2014). and and present the results. First, standardised factor loadings less than .50 (Hair et al., Citation2010) were removed (see ). In , the factor loadings of all observed variables (.542 to 914) were more than .50, indicating the evidence for convergent validity. Thus, all the items represent the underlying constructs (Hair et al., Citation2014, Citation2017; Vinzi et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, the internal consistency of the latent variables was good because their Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from .624 to .885 and composite reliability values ranged from .784 to .903. These reliabilities were above the threshold of .60 and .7 (Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2009).

Table 3. Assessment of outer model: discriminant validity.

Again, the AVE values ranged from .600 and .809 which are all above the acceptable threshold value of .5, thus depicting acceptable levels of convergent validity for all the constructs (Hair et al., Citation2014; Henseler et al., Citation2009). However, teaching self-efficacy (TSE) has AVE value of .440 which is below the threshold. If AVE is less than .5, but CR is higher than .6, the convergent validity of the construct can be adequate (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, the CR of TSE is .903 implying that convergent validity was confirmed. presents structure model after PLS-SEM Algorithm and provides the results for discriminant validity using Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

From , discriminant validity of the model was established because the square roots of the AVE values (ie diagonal values in bold) for all the main constructs in the model are greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations (ie all values below the bold values). The values of square roots of the AVE ranged from .664 to .900 (Fornell & Larcker Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2014, Citation2017). Furthermore, using Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio, we confirmed discriminant validity because the HTMT ratio values were below the threshold of .850 or .90 (Collier, Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

3.2. Economics teachers’ level of teaching efficacy

In , the result showed that the teaching efficacy dimensions of Economics teachers had values ranging from 5.16 (SD = .67) to 5.23 (SD = .62), representing a high level of teaching efficacy. Generally, the overall score revealed that the Economics Teachers had a high level of teaching efficacy (M = 5.12; SD = .54). Relatively, they are highly efficacious in classroom management (M = 5. 23; SD = .62) compared to student engagement and instructional strategies.

Table 4. Level of teaching efficacy.

3.3. Economics teachers’ engagement in PLC practices

As shown in , Economics teachers generally had positive perceptions (M = 4.37; SD = .63) towards their engagement in PLCs practices in the school. The mean score of teachers’ engagement in PLCs ranges from 4.30(SD = .86) to 4.70 (SD = .89) indicating their moderate level of engagement in PLCs. The teachers’ engagement in PLCs seems to be moderately high in SVV (M = 4.70; SD = .89) and moderately low in SCR (M = 4.30; SD = .85).

Table 5. Teachers’ perceptions of PLCs practices.

3.4. Test of the structural model

This research examined Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs and its effect on their teaching self-efficacy beliefs. and present the results of structural model assessment after bootstrapping. Structural model was assessed by means of the coefficient of determination (R2) and the standardised beta coefficient (β) for each hypothesised relationship. The significance of the effects was evaluated using bootstrapping (Hair et al., Citation2014; Kock, Citation2015). The coefficient of determination (R2) reflects exogenous latent variables’ (PLCs) ability to predict endogenous latent variable (teaching self-efficacy). Accordingly, the R-square (R2) test in this study followed the category from that of Chin and Marcoulides (Citation1998), which has the category of .67 (substantial), .33 (moderate) and .19 (weak). The effect size (f2) determines the extent of the influence of the latent predictor variable (dimensions of PLC) on the outcome variable (teaching efficacy). In this study, the size effect (f2) is divided into three categories: small (.02), medium (.15) and large (.35) (Hair et al., Citation2013).

Table 6. Influence of engagement in PLCs and teaching self-efficacy beliefs.

In , the R2 has a value of .452, meaning that Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs moderately explained 45.2% of the variation in their teaching efficacy beliefs. In and , it is observed that teachers’ engagement in SSL has the direct significant influence on teaching self-efficacy beliefs (β = .307, t = 2.932, p < .003). The magnitude of the effect was moderate (f2 = .107). The results further demonstrated that teachers’ engagement in SPP (β = .224, t = 1.437, p < .151) and CLA (β = .187, t = 1.253, p = .210) were positively related to teaching self-efficacy beliefs. The magnitude of the effects was small. The positive standardised beta coefficient (β) of all the dimensions of PLCs suggests that a unit increase in Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs would increase their teaching efficacy by the same proportion.

4. Discussion

Substantial literature has revealed that teachers’ teaching efficacy is critical to improving students’ learning, teacher commitment, job satisfaction and curriculum implementation (Agormedah et al., Citation2022; Bandura, Citation1997; R. D. Goddard & Goddard, Citation2001; R. D. Goddard et al., Citation2004; Moolenaar et al., Citation2012). Accordingly, school reforms have advocated PLCs as a school-level approach for improving teacher learning and productivity (Dufour & Eaker, Citation1998; Hord, Citation1997; Lieberman, Citation1995). The significance of both PLCs and teachers’ teaching self-efficacy beliefs has stimulated studies to explore the relationship between these two constructs (R. Goddard et al., Citation2015; Gray & Summers, Citation2015; J. C. Lee et al, Citation2011; Moolenaar et al., Citation2012; Voelkel & Chrispeels, Citation2017). The current inquiry examines the (1) SHS Economics teachers’ level of teaching self-efficacy beliefs, (2) SHS Economics teachers’ level of engagement in PLCs and (3) influence of Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs on teaching self-efficacy beliefs.

We have discovered that Economics teachers had a high level of teaching efficacy. This was evident in the classroom management, student engagement and instructional strategies. This finding lends support to previous studies that established that teachers were highly efficacious in classroom management, student engagement and instructional strategies (Agormedah et al., Citation2022; Arko, Citation2021; Mehdinezhad, Citation2012; Sarfo et al., Citation2015; Yidana & Arthur, Citation2023; Yidana & Ntarmah, Citation2016). The high level of teaching efficacy among SHS Economics teachers is an indication of their preparedness to teach. It is an indication that the SHS Economics teachers have a high level of teaching capacity and self-confidence to affect students’ learning via appropriate instructional strategies, quality classroom management and students’ engagement. The high level of teaching self-efficacy among SHS Economics teachers is also an indication of instructional effectiveness that would be consistently related to their behaviours and student outcomes.

The study established that generally, Economics teachers were moderately engaged in PLCs implementation in schools. The teachers’ engagement in PLCs implies that they had positive perceptions towards the implementation of PLCs in schools. This finding confirms the study of prior researchers who found that teachers had positive perceptions towards the implementation of PLCs in school (Bailey, Citation2016; Garvin, Citation2020; Gilliam, Citation2020; Porter, Citation2014; Stegall, Citation2011). Garvin (Citation2020) and Porter (Citation2014) discovered that the teachers engaged in the components of the PLCs. However, the finding of the current study disagrees with that of Garvin (Citation2020) and Bailey (Citation2016) which revealed that teachers had negative perceptions or engagement in SPP. These inconsistencies in the findings could be attributed to context of the study, educational policies and philosophies, characteristics of the sample or population, among others.

Specifically, we discovered that the teachers themselves perceived that they moderately practiced SVV, CLA, SPP and SCR. This implies that the Economics teachers believed that a shared vision for their department and school exists along with shared values and goals. They generally agreed that their policies, mission, vision and goals are consistently aligned throughout school and decisions are based on that collective practice. When teachers work together to build a school vision, they feel more connected and collaboratively work to accomplish collective goals (DuFour et al., Citation2008). The Economics teachers also feel that collective learning exists among the staff members within their schools. Therefore, one can expect collaboration among staff members in the areas of sharing information, planning, solving problems and improving learning opportunities. Routine dialogue with colleagues helps connect learning with application and enhances pedagogical skills (Sparks, Citation2005). This should influence the sense of community in a school (Hipp & Huffman, Citation2010). They also felt that time is provided for them to observe others, provide feedback and share/review student work. This suggests that teachers feel that they leverage opportunities to work together collaboratively and share their best ideas/practice. This result agrees with the conclusion made by Blase and Blase (Citation2000) that when teachers work in consultation with peers and reflect on personal practice their teacher efficacy is enhanced. Finally, the teachers contend that positive caring relationships exist among their entire school community. As a result of this, teachers are able to find help, support and trust among their colleagues. This result supports the assertion made by Hipp and Huffman (Citation2010) that a positive school climate or culture creates a culture of trust, respect and inclusiveness among teachers that enable them to have access to help and support.

Conversely, the Economics teachers have diverse responses concerning their engagement in SSL and SCS. Teachers having varied responses concerning SSL and SCS are indications that they have negative concerns about the practices of SSL and SCS in the schools. Economics teachers also expressed concerns regarding systems and resources that are made available to enable staff to meet and examine practices and student outcomes. Inadequate shared and supportive leadership, time, fiscal resources and instructional resources could hinder teachers’ instructional effectiveness and support. This may negatively affect curriculum implementation, students’ learning and school effectiveness.

Regarding the third research question, we have discovered positive influences of the dimensions of PLCs (SSL, SVV, CLA, SPP, SCR and SCS) on teaching efficacy beliefs among Economics teachers. Specifically, we have found a positive and statistically significant relationship between SSL and teaching efficacy beliefs of Economics teachers. Eventually, we established that teachers’ engagement in PLCs accounts for 45.2% variance in teaching efficacy beliefs. The positive standardised beta coefficients (β) of all the dimensions of PLCs imply their partial positive effect on Economics teachers’ teaching efficacy. The positive partial effects [standardised beta coefficient (β)] of the dimensions of PLCs suggest that a unit increase in Economics teachers’ engagement in PLCs would positively increase their teaching efficacy in that proportion. Thus, as Economics teachers are highly and positively engaged in PLCs (SSL, SVV, CLA, SPP, SCR and SCS), their teaching efficacy also increases positively. The findings of the current study lend support to the studies of previous researchers who discovered a positive relationship between the dimensions of PLCs and teaching efficacy of teachers (Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; Karuppannan et al., Citation2021; Porter, Citation2014; Yada et al., Citation2022; Zheng et al., Citation2021). Karuppannan et al. (Citation2021) found that there is a relationship between the PLC practices and teachers’ efficacy but at a moderately high level. Heaton (Citation2013) observed that SSL and SCS correlated significantly with teacher self-efficacy. Similarly, Stegall (Citation2011) found that the strongest relationships existed between SSL and each of the three subcategories of teacher self-efficacy when compared to any of the other five components measured through the PLCA-R. The findings of the current study agree with prior studies that teacher engagement in SPP, CLA, interactive and collective reflection, reflective dialogue and collegiality were related to their teaching self-efficacy (Kennedy & Smith, Citation2013; Vanblaere & Devos, Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2019; Zonoubi et al., Citation2017). The findings of the current study are similar to an earlier observation, indicating that critical reflection and discussion about pedagogical conceptual change with other colleagues are likely to impact teachers’ self-efficacy (Lee et al., Citation2013; Zonoubi et al., Citation2017).

However, the findings of the current study disconfirmed the findings of former researchers who revealed that there were no significant relationships with PLC dimensions and teacher efficacy (Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; Weathers, Citation2009). Heaton (Citation2013) discovered that SVV and SCR have a negative relationship with TSES scores of the participants. Gilliam (Citation2020) found that SSL, SVV, CLA and SPP are non-significant predictors of teaching efficacy beliefs. The inconsistency in these findings could be attributed to the context of the study, educational policies on PLCs and statistical strategy. The current investigation deployed structural equation modelling via SmartPLS while previous studies used correlational and regression analyses (Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; Weathers, Citation2009). The weakness associated with regression analyses makes the findings of this current study authentic, valid and reliable in terms of prediction. Our findings that a positive and significant relationship exists between the leadership approach and the teacher self-efficacy of the educators and positive associations between other dimensions of PLCs and teaching efficacy of Economics teachers suggests this is an important area of focus. The positive influences of the dimensions of PLCs on teachers’ teaching efficacy beliefs indicate that the way in which the dimensions of PLCs are implemented can have significant effects on teacher self-efficacy.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This research draws its strength through the application of a more robust statistical procedure (ie structural equation modelling via SmartPLS) in examining the influence of teachers’ engagement in PLCs on teaching self-efficacy beliefs. This is a novel study in Ghana and beyond because to the best of our knowledge, such a study has never been undertaken using data from Ghanaian Economics teachers. These findings were novel as compared to previous studies in terms of statistical approach (Gilliam, Citation2020; Heaton, Citation2013; Weathers, Citation2009). Correlation and regression analyses among the previous studies were starting point for establishing predictive relationships between PLCs and teaching efficacy. However, they are limited to fit complex datasets properly like PLCs and teaching efficacy. The research findings provide solid support to the social cognitive theory to underscore the relationship between PLCs and teaching efficacy. The present research used a cross-sectional design. Hence, no firm conclusions can be made regarding the causal direction of the associations among variables. Also, the issue of measurement of variable serves as a limitation in this current study. Literature has no clear line of definition and element of PLCs and teaching efficacy. Additionally, the data were collected using self-reporting, which might have caused single-source bias, in which participants generalise their recognition using a cognitive schema.

5. Conclusion & recommendations

We have established that Economics teachers have a high level of teaching efficacy. They were highly efficacious in classroom management, students’ engagement and instructional strategies. This is an indication of high level of teaching capacity and confidence and readiness to teach. The teachers were moderately engaged in the implementation of PLCs in school. This an indication of the teachers’ positive perceptions towards implementation of PLCs. However, the teachers have diverse responses concerning their engagement SSL and SCS. Teachers’ moderate engagement in PLCs implementation may indicate that many of the challenges of implementing a new improvement program may need critical attention. This study also highlights the importance of implementation of PLCs in schools because of its positive association with teachers’ teaching efficacy. The study highlighted the SSL as critical and significant dimension of PLCs implementation in influencing teachers’ teaching efficacy.

The study recommends that the MoE through the Ghana Education Services (GES) and school administrators should continue to sustain teaching efficacy beliefs of Economics teachers by organising sustained in-service training programs and workshops for teachers. Economics teachers should not relent in their high self-efficacy beliefs since it helps in effective curriculum implementation. The study further recommends that MoE, GES and school administrators should: (a) continue to provide support and supportive leadership to teachers to enable them feel they are part of the process, without the process dictated to them; (b) ensure that teachers work together to build a school vision for them to feel more connected and collaboratively work to accomplish collective goals; (c) structure purposeful opportunities for teacher collaboration that transfers professional knowledge into classroom application in the context of student learning; (d) must provide teachers with time to reflect, to engage in collective inquiry, to collaborate and to participate in continuous improvement processes; (e) support empathy and interaction among teams, model sensitivity and be aware of the feelings that have a potential to disturb collaborative work and (f) provide logistics, facilities, instructional resources and adequate time for teachers to work together. All these provisions in turn gives teachers a greater sense of self-efficacy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data on which the findings and conclusions of the study are derived will be available upon request from the corresponding author at [email protected]. This request will be considered in 12 months’ time after the publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mumuni Baba Yidana

Mumuni Baba Yidana (Ph.D) is an Associate Professor of Curriculum Development (Economics) in the Department of Business and Social Sciences Education at the University of Cape Coast. His research interest includes Educational Assessment, Curriculum Change and Evaluation, Curriculum Theory, Teacher Education in Economics, Economics of Education and Application of Multiple Intelligences approach in Economics. He has over 20 years of professional experience in managing projects relating to Curriculum Development and Economics Education.

Bernard Yaw Sekyi Acquah

Dr Bernard Yaw Sekyi Acquah is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Business and Social Sciences Education with over fourteen years of teaching and research experience in Curriculum and Teaching, Economics Education and Teacher Education. He has played critical roles in curriculum development at the institutional and national levels. He is the Director of the Center for Teacher Professional Development at the University of Cape Coast, where he coordinates teaching practice for undergraduate and postgraduate students and runs continuous professional development activities for in-service teachers.

References

- Abdullah, M. S. B., & Kong, K. (2016). Teachers’ sense of efficacy with regards to gender, teaching options and experience [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of ISER 17th International Conference, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Agormedah, E. K., Ankomah, F., Frimpong, J. B., Quansah, F., Srem-Sai, M., Hagan, J. E., Jr., & Schack, T. (2022). Investigating teachers’ experience and self-efficacy beliefs across gender in implementing the new standards-based curriculum in Ghana. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.932447

- Arko, D. A. (2021). How confident are social studies teachers in curriculum implementation? Understanding teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR), 5(11), 186–17.

- Asare, E. O., Mereku, D. K., Anamuah-Mensah, J., & Oduro, G. K. T. (2012). In-service teacher education study in Sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Ghana. GES.

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Bailey, K. T. (2016). [The perceived impact of professional learning communities on collective teacher efficacy in two rural Western North Carolina school districts] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. School of Education, Gardner-Webb University.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 61–90). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Bandura, A. (1998). Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health, 13(4), 623–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449808407422

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice-Hall.

- Berman, P., McLaughlin, M. W., Bass-Golod, E. P., & Zellman, G. L. (1977). Federal programs supporting educational change. RAND.

- Blase, J., & Blase, J. (2000). Effective instructional leadership teachers’ perspectives on how principals promote teaching and learning in schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(2), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230010320082

- Burns, N., & Grove, S. K. (2005). The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique, and utilisation (5th ed.). Elsevier Saunders.

- Byrne, B. M. (2011). Structural equation modeling with AMOS basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Capili-Balbalin, W. (2017). [The development of professional learning communities (PLCs) in the Philippines: Roles and views of secondary school principals] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Waikato.

- Chen, G., Chan, C. K., Chan, K. K., Clarke, S. N., & Resnick, L. B. (2020). Efficacy of video-based teacher professional development for increasing classroom discourse and student learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(4-5), 642–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2020.1783269

- Chin, W. W., & Marcoulides, G. A. (1998). Methodology for business and management. Modern methods for business research. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge.

- Daly A. J. (Ed.). (2010). Social network theory and educational change. Harvard University Press.

- Dampson, D. G. (2021). Effectiveness of professional learning communities in Ghanaian basic schools through the lenses of socio-cultural theory. Journal of Educational Issues, 7(2), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.5296/jei.v7i2.19114

- Doğan, S., & Yurtseven, N. (2018). Professional learning as a predictor for instructional quality: A secondary analysis of TALIS. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1383274

- Doppenberg, J. J., Bakx, A. W., & Brok, P. J. D. (2012). Collaborative teacher learning in different primary school settings. Teachers and Teaching, 18(5), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709731

- DuFour, R. (2004). What is a professional learning community? Educational Leadership, 61, 6–11.

- Dufour, R., Dufour, R., & Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: New insights for improving schools. Solution Tree Press.

- DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. National Educational Service.

- DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work (2nd ed.). Solution Tree.

- Elmore, R. F. (2007). Professional networks and school improvement. School Administrator, 64(4), 20–24.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Fullan, M. (1994). Implementation of innovations. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., pp. 2839–2847). Pergamon Press.

- Garvin, M. (2020). [Professional learning communities in an elementary school: Teacher perceptions, implementation, and impacts] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Faculty of the College of Education & Social Work, West Chester University West Chester.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step. A simple study guide and reference (10. Baskı). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Gilliam, D. G. (2020). [Correlation between teacher efficacy and effective professional learning communities] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Eastern Kentucky University.

- Goddard, R. D.,Hoy, W. K., &Hoy, A. W. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37, 479–507. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312037002479

- Goddard, R., Goddard, Y., Sook Kim, E., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration, and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. https://doi.org/10.1086/681925

- Goddard, R. D., & Goddard, Y. L. (2001). A multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher and collective efficacy in urban schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 807–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00032-4

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2004). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033003003

- Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). A theoretical and empirical investigation of teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 109(4), 877–896. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810710900401

- Gray, J. A., & Summers, R. (2015). International professional learning communities: The role of enabling school structures, trust, and collective efficacy. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(3), 61–75.

- Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hardin, J. (2010). [A study of social cognitive theory: The relationship between professional learning communities and collective teacher efficacy in international school settings] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Capella University.

- Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership as distributed leadership. School Leadership & Management, 23(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000112801

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximising impact learning. Routledge.

- Heaton, M. (2013). [An examination of the relationship between professional learning community variables and teacher self-efficacy] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Education, University of Windsor.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–320.

- Hipp, K. K., & Huffman, J. B. (2010). Demystifying professional learning communities: School leadership at its best. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hodges, C. B., Gale, J., & Meng, A. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy during the implementation of a problem-based science curriculum. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 16, 434–451.

- Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., & Kunter, M. (2013). How teachers’ self-efficacy is related to instructional quality: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032198

- Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

- Jones, M. G., Gardner, G. E., Robertson, L., & Robert, S. (2013). Science professional learning communities: Beyond a singular view of teacher professional development. International Journal of Science Education, 35(10), 1756–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2013.791957

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1970). A general method for estimating a linear structural equation system (Report No. RB-70-54). Educational Testing Service.

- Jumanne, J. (2012). Teacher self-efficacy in teaching science process skills: An experience of Biology teachers in Morogoro-Tanzania. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Kabaoglu, K. (2015). [Predictors of curriculum implementation level in elementary mathematics education: Mathematics-related beliefs and teacher self-efficacy beliefs] [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Graduate School of Social Sciences, Middle East Technical University.

- Karuppannan, G., Duari, H., & Sultan, F. M. M. (2021). Relationship between professional learning community (PLC) practices and teachers’ efficacy among secondary school teachers in Malaysia. International Journal of Scientific and Management Research, 04(07), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.37502/IJSMR.2021.4710

- Kennedy, S. Y., & Smith, J. B. (2013). The relationship between school collective reflective practice and teacher physiological efficacy sources. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.003

- Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M. C., Betts, S. M., & Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher efficacy research 1998–2009: Signs of progress or unfulfilled promise? Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

- Lee, B., Cawthon, S., & Dawson, K. (2013). Elementary and secondary teacher self-efficacy for teaching and pedagogical conceptual change in a drama-based professional development program. Teaching and Teacher Education, 30, 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.010

- Lee, J. C., Zhang, Z., & Yin, H. (2011). A multilevel analysis of the impact of a professional learning community, faculty trust in colleagues and collective efficacy on teacher commitment to students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.006

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

- Lieberman, A. (1995). Practices that support teacher development: Transforming conceptions of professional learning. Innovating and Evaluating Science Education, 95(64), 67–78.

- Mehdinezhad, V. (2012). Relationship between high school teachers’ wellbeing and teachers’ efficacy. Acta Scientiarum Education, 34(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v34i2.16716

- Ministry of Education. (2019). National pre-tertiary education curriculum framework for developing subject curricula. https://ghanaeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/National-Pre-Tertiary-Learning-Assessment-Framework_-24062020.pdf

- Moolenaar, N. M., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Daly, A. J. (2012). Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy and student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.001

- Olivier, D. F., & Hipp, K. K. (2010). Assessing and analysing schools as professional learning communities. In K. K. Hipp & J. B. Huffman (Eds.), Demystifying professional learning communities (pp. 29–41). Rowman and Littlefield.

- Olivier, D. F., Hipp, K. K., & Huffman, J. B. (2003). Professional learning community assessment. In J. B. Huffman & K. K. Hipp (Eds.), Professional learning communities: Initiation to implementation (pp. 133–141, 171–173). Scarecrow Press.

- Pandita, R. (2012). Correlational research. Web.

- Porter, T. (2014). [Professional learning communities and teacher self-efficacy] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Education and Leadership Foundations Department George Fox University.

- Rashid, A. (2012). Research methods in education. Web.

- Sarfo, F. K., Amankwah, F., Sam, F. K., & Konin, D. (2015). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: The relationship between gender and instructional strategies, classroom management and student engagement. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 12(1-2), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v12i1-2.2

- Sawyer, L. B. E., & Rimm‐Kaufman, S. E. (2007). Teacher collaboration in the context of the responsive classroom approach. Teachers and Teaching, 13(3), 211–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600701299767

- Seo, K., & Han, Y. K. (2012). The vision and the reality of professional learning communities in Korean schools. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 9(2).

- Shetzer, S. (2011). [A study of the relationship between teacher efficacy and professional learning communities in an urban high school] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of the College of Education, University of Houston.

- Snyder, J., Bolin, F., & Zumwalt, K. (1992). Curriculum implementation. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 402–433). Macmillan.

- Soares, F., Galisson, K., & van de Laar, M. (2020). A typology of professional learning communities (PLC) for Sub-Saharan Africa: A case study of Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, and Nigeria. African Journal of Teacher Education, 9(2), 110–143. https://doi.org/10.21083/ajote.v9i2.6271

- Soodak, L. C., & Podell, D. M. (1996). Teacher efficacy: Toward the understanding of a multi-faceted construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 12(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(95)00047-N

- Sparks, D. (2005). Leading for results: Teaching, learning, and relationships in schools. Corwin Press.

- Stegall, D. A. (2011). [Professional learning communities and teacher efficacy: A correlational study] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Appalachian State University.

- Susilanas, R., Asra, A., & Herlina, H. (2018). The contribution of the self-efficacy of curriculum development team and curriculum document quality to the implementation of diversified curriculum in Indonesia. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(3), 31–40.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Barr, M. (2004). Fostering student learning: The relationship of collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(3), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760490503706

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1086/605771

- Vanblaere, B., & Devos, G. (2016). Relating school leadership to perceived professional learning community characteristics: A multilevel analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.003

- Vinzi, V. E., Chin, W. W., Henseler, J., & Wang, H. (2010). Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications. Springer.

- Voelkel, R. H., Jr., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(4), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

- Wang’eri, T., & Otanga, H. (2014). Sources of personal teachers’ efficacy and influence on teaching methods among teachers in primary schools in Coast Province, Kenya. Global Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 3, 190–195.

- Weathers, S. R. (2009). [A study to identify the components of professional learning communities that correlate with teacher efficacy, satisfaction, and morale] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Georgia Southern University.

- Wright, S. (1934). The method of path coefficients. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 5(3), 161–215. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177732676

- Yada, T., Yada, A., Choshi, D., Sakata, T., Wakimoto, T., & Nakada, M. (2022). Examining the relationships between teacher self-efficacy, professional learning community, and experiential learning in Japan. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 34(1), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2136211

- Yang, H. (2020). The effects of professional development experience on teacher self-efficacy: Analysis of an international dataset using Bayesian multilevel models. Professional Development in Education, 46(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1643393

- Yidana, M. B., & Arthur, F. (2023). Exploring economics teachers’ efficacy beliefs in the teaching of economics. Cogent Education, 10(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2222652

- Yidana, M. B., & Ntarmah, A. H. (2016). Teachers’ efficacy beliefs in the implementation of senior high school economics curriculum. Journal of Educational Development and Practice, 7(2), 144–161. https://doi.org/10.47963/jedp.v7i.979

- Yusof, C. M., & Nor, M. M. (2017). Level of teacher’s self-efficacy based on gender, teaching experience and teacher training. Advanced Science Letters, 23(3), 2119–2122. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.8573

- Zhang, J., Yin, H., & Wang, T. (2020). Exploring the effects of professional learning communities on teacher’s self-efficacy and job satisfaction in Shanghai, China. Educational Studies, 49(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1834357

- Zheng, X., Yin, H., & Li, Z. (2019). Exploring the relationships among instructional leadership, professional learning communities and teacher self-efficacy in China. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(6), 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143218764176

- Zheng, X., Yin, H., & Liu, Y. (2021). Are professional learning communities beneficial for teachers? A multilevel analysis of teacher self-efficacy and commitment in China. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1808484

- Zonoubi, R., Eslami Rasekh, A., & Tavakoli, M. (2017). EFL teacher self-efficacy development in professional learning communities. System, 66, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.03.003