?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Police accountability is essential for affected victims and public trust-building, yet there are limited interventions addressing this issue. A mixed method design was adopted to examine the feasibility, appropriateness, and acceptability of a Legal Education-informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (LiCBT) for improving victims’ confidence using 24 participants from Delta-State, Nigeria. Participants were assessed using the Legal-Consciousness-Questionnaire, Legal Awareness of Complaint Channel Scale and the PHQ-9. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used to analyse quantitative data, while the qualitative analyses involved thematic-analysis from a social identity theoretical lens. The study recorded retention rates of 96% in the 12-sessions and 100% in the baseline, end-of-intervention and 3-months follow-ups. Participants showed increased knowledge of their legal rights (LCQ) from baseline (Md = 1.00) to end of intervention (Md = 4.00) with z = −4.427, and at 3-months follow-up, z = −4.423. Findings also showed reduced depression from baseline (Md = 4.00) to end of intervention (Md = 1.00) with z = −4.061 and at 3 months (Md = 1.00) with z = −4.142. LiCBT is acceptable and feasible for improving legal knowledge, reducing depression, including improving positive attitudes towards the police. A fully powered randomised control trial is recommended to test its effectiveness.

Keywords:

Subjects:

Introduction

Awareness of legal avenues for police accountability constitutes an integral aspect of public trust building and confidence in the police to help curb crime and maintain law and order. Widespread public alienation from the police is an issue that consistently plagues the Nigerian police in effectively dispensing its duties (Akinlabi, Citation2022; Akintayo, 2019; Ike et al., Citation2023). In a country of over 200 million, awareness of avenues for accountability against police misconduct is important, especially considering the trauma victims have suffered as a result of police brutality, as exemplified in the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) infamous #EndSARS protest against police brutality and corruption in 2020 and the public poor awareness of complaint channels (Ike et al., Citation2023). The study seeks to address this gap through a novel Legal Education-informed Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (LiCBT) alongside an innovative, evidence-based methodology to test its feasibility and acceptability among the identified population. The LiCBT as a concept is defined as an intervention to promote awareness of legal channels for police accountability, including reducing depression and negative attitudes towards the police.

The awareness of avenues of accountability against police misconduct is crucial, given the poorly funded, understaffed police force whose police-to-public ratio is well under the United Nations (UN) recommendation. According to the UN, the recommended police-to-population ratio is 1:450, with one police officer for every 450 citizens. However, in Nigeria, the figure is way below, with an estimated 1:557(Azuwike & Eboh, Citation2021). In the UK, there are an estimated 251 police assigned per 100,000 population (Home Office, Citation2023). Compared to Nigeria, it means that for every 100,000 population in Nigeria, 179 police are assigned. This problem of police personnel shortage is further compounded by the growing insecurity and terrorist threat which the ongoing public lack of confidence in the police will further serve to undermine their ability to address these problems given public members’ reluctance to divulge requisite information or support to curb crime (Ike et al., Citation2022, Citation2024). Thus, it delineates the need to improve public trust and confidence in the police. For example, growing insecurity in the form of armed banditry, kidnapping and crime has further instilled enormous pressure on an overstretched and under-resourced police force (Akintayo, Citation2019; Ike, Singh, Jidong, Murphy, et al., Citation2021).

While being under-resourced is an issue, in Nigeria, widespread public scepticism towards the police has led to a lack of trust due to police corruption, torture, poor police legitimacy and arbitrary arrest (Akinlabi, Citation2022; Amnesty International, Citation2015; Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021; John, Citation2017; Onwuama et al., Citation2019; Shodunke, Citation2023; Usman, Citation2019). It culminated in the mass #EndSARS protests in 2020, calling for a stop to police brutality against the public (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021; Iwuoha & Aniche, Citation2021). Central to the lack of trust is the issue of accountability and awareness of legal mechanisms to report police misconduct. Previous literature on police-public relations and accountability in Nigeria has often tended to focus on poor public perceptions of the police mannerism, corruption, issues of torture and inhumane police practice (Amnesty International, Citation2020, Human Rights Watch, Citation2021; Idowu, Citation2016; John, Citation2017; Onwuama et al., Citation2019; Usman, Citation2019). Even when studies seek to explore public knowledge of channels of accountability, they often tend to focus on their awareness of channels of accountability, which is sorely low among victims (Ike et al., Citation2023). For example, Ike et al. (Citation2023) study showed that public members and even victims interviewed highlighted a lack of awareness of appropriate channels for reporting police misconduct as one of the significant reasons constraining citizens in prompt reporting of Nigerian police misconduct. Ike et al. (Citation2023) study also suggested legal education programmes to address negative attitudes and improve victims’ and public confidence in the police.

Concerning improving public confidence, other studies that attempt to use experimental designs to address accountability issues have also focused on testing interventions such as community policing efficacy using 18,382 citizens and 874 police officers in the global south (Blair et al., Citation2021). Other studies have tested mechanisms such as body-worn cameras in tracking police actions (Braga et al., Citation2021; Lum et al., Citation2019). Mazerolle et al.’s (Citation2013) study specifically addressed procedurally just dialogue focused on improving citizens’ perceptions of police legitimacy. Some studies have also used quasi-experimental designs to test interventions such as problem-oriented policing (Jesilow et al., Citation1998). Others have tested problem-solving policing strategies on crime outcomes (Bond-Fortier & Nader, Citation2022) and the Broken windows experiment in policing (Monaghan, Citation2022).

In essence, there exists a gap in the literature on testing Legal Education-informed Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (LiCBT) to promote awareness of legal channels for police accountability, including reducing depression and negative attitudes towards the police. Our study thus makes an original and significant contribution to the literature on police policy and practice designed to improve public confidence by examining the feasibility of the LiCBT in improving trust in the police and changing negative attitudes towards the police. The LiCBT is an intervention made of two parts – legal education and cognitive behavioural therapy in addressing the gap highlighted by the poor level of awareness for reporting police unprofessionalism and improving victims’ negative attitude towards the police. Our study’s rigour is demonstrated through its experimental design using a single-arm feasiblity trial to allow for replication. Collectively, our study’s contribution is important, especially considering the gap highlighted in previous literature concerning ongoing security threats and crimes in Nigeria (Ike et al., Citation2023) and the need for public support in intelligence sharing to support the police in crime fighting and the maintenance of law and order (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021). In the absence of such public confidence, policing becomes a challenge, especially considering the depleting funding of the police and the low police-public ratio due to an understaffed police force. It is against the preceding backdrop that our study seeks to address the research question:

What is the feasibility of implementing Legal Education-informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (LiCBT) in terms of recruitment, retention, acceptability and victims satisfaction with the intervention to improve confidence in the Nigerian police?

Test the feasibility of LiCBT in terms of recruitment, retention, acceptability and victims satisfaction with the intervention to improve confidence in the Nigerian police using an experimental evidence-based design and methodology.

Police-public relation in Nigeria: police corruption and the need for LiCBT

Addressing accountability issues requires a brief engagement with the public historical context of confronting the police in Nigeria and how colonialism shapes and influences the country’s contemporary policing practice alongside fuelling public distrust for the police. The establishment of the Nigerian Police in 1930 was, historically, a product of the British amalgamation of the northern and southern protectorates in 1914 (Daniels, Citation2012; Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021). Alemika (Citation1988) argues that the preoccupations of the colonial police force in Nigeria were not to enforce the rule of law, equity and natural justice for the majority of Nigerians as claimed by the colonial ruler. Instead, Alemika (Citation1988) contends that the colonial police force was created and preoccupied with maintaining order and serving the colonialists as personal servants. The police force was also tied to British imperial expansionism, colonial economic and political adventurism to acquire raw materials and lucrative markets for her industries beyond Britain (Ahire, Citation1991; Alemika, Citation1988; Tamuno, Citation1970). To this extent, extensive resources and efforts of the police were committed to the suppression of protests and struggle against exploitation and oppression following the enormous theft of public wealth orchestrated by those who control the state apparatus and economy (Alemika, Citation1988; Ikime, 1966). In response to such subjugation, members of the public have historically resorted to protest or strike. Notable examples include the 1949 Enugu workers’ colliery strike and massacre.

Consequently, the prevailing argument concerning the police is that it is perceived as an organisation not designed to serve the public. The reasons are partly because of its historical origin marred by the colonialists’ usage for subjugation and oppression, including torturing those alleged to have committed criminal offences, harassing and arresting tax defaulters, and brutalising trade unionists and other nationalists.

Post-independence, corruption has remained one of the endemic factors that have plagued the Nigerian police and further hamper public trust in the police, for which several explanations have been proffered (Shodunke, Citation2023; Agbiboa, Citation2015; Akinlabi, Citation2017; Audu, Citation2016; Khan et al., Citation2021). Shodunke (Citation2023, p. 1) argues that “the embedded problems of police corruption revolve around unresolved police institutional challenges and police-public connivance that results from moral decadence.” Agbiboa (Citation2015), whilst drawing on data from ethnographic fieldwork from Lagos state, contends that corrupt and abusive policing directly links to the complex socio-historical conditions and everyday practices rather than a purely managerial problem—thus likely to defy simple internal reform. Akinlabi (2017), based on a sample of 462 participants, finds that police-public relations in Nigeria are poor and that police deviance engenders cynicism towards the law due to the police organisation’s failure to detect or discipline errant officers. Other scholars relying on data from 1152 participants recruited from Lagos state also highlight how unethical practices and institutional problems in the Criminal justice system exacerbate public distrust and human rights violations through resorting to mob justice (Shodunke et al., Citation2023).

In addition to corruption, poor accountability, lack of trust, questionable legitimacy, and police brutality against the public have consistently marred the Nigerian police reputation (Akinlabi, Citation2022; Akintayo, 2019; Imoudu, Citation2022; John, Citation2017; Shoyode, Citation2018; Usman, Citation2019). For example, Amnesty International’s (2020) study comprising 82 interviews with victims, human rights defenders, witnesses of abuse and lawyers found that there appear to be cases of torture, ill-treatment, and extortion by the Nigeria Police Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) Unit. Amnesty International (Citation2020) also found that few cases proceeded to investigations, and hardly any officers were brought to justice because of ill-treatment or torture. Even the Human Rights Watch (Citation2021) study in Nigeria, which comprises interviews with 54 people, including victims, protesters, medical service providers and representatives of civil groups following the #EndSARS protest, found issues of poor accountability concerning issues of abuses carried out by the police and security forces. Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al. (2021) systematic review found that the community perspectives of the police in Nigeria are characterised by a lack of confidence in the police, poor mannerisms, and a lack of equality in the police dispensation of its duties (Ayodele & Aderinto, Citation2014; Audu, Citation2016; Onwuama et al., Citation2019; Shoyode, Citation2018). A recent study comprising individuals who were victims of perceived Nigerian police misconduct found limited awareness of avenues for reporting police unprofessionalism and seeking redress (Ike et al., Citation2023). The study also found that affected victims suffered from trauma and depression arising from the poor awareness of accountability channels to seek redress (Ike et al., Citation2023). Whilst the majority of the literature blames corruption, other studies have also identified factors such as poor working conditions, inadequate pay, lack of proper equipment and resources coupled with poor leadership as instrumental to police failure to effectively dispense their duties (Louis et al., Citation2024).

The preceding literature undoubtedly highlights a gap our study seeks to address, using Legal Education informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (LiCBT), which originates from previous research on victims and the poor public awareness of the institutional framework and channels for police accountability. It is also informed by the need for more methodologically rigorous intervention to study legal awareness, especially within the Nigerian context. Previous literature has tended to focus more on cross-sectional and qualitative design, including exploring the barriers to public trust in the police, such as police brutality, corruption, extortion, and extrajudicial killings, with limited focus on evidence-based solutions using the LiCBT to address the problem of poor awareness of institutional channels for police accountability (Aniche & Iwuoha, Citation2023; Emoedumhe et al., Citation2024; Zbytovsky & Prouza, Citation2024).

The institutional framework of police accountability in Nigeria

Globally, studies on policing have often tended to focus on aspects such as reform, legitimacy and accountability (Akinlabi, Citation2017; Alemika & Chukwuma, Citation2003; Goldsmith, Citation2005; Onyeozili et al., Citation2021; Williams & Paterson, Citation2021). As Bajramspahić and Muk (Citation2015) argue, having a well-structured internal policing control system may help prevent and detect corruption and inappropriate behaviour among police officers. Such control aims to ensure an improved police reputation and responsible officers (Bajramspahić & Muk, Citation2015). Bent (Citation1974) contends that in the absence of accountability, the police may become vulnerable to being used as an oppressive organ by the government or become unruly in exercising their powers for selfish gain. (Bent, Citation1974). As such, Goldstein (Citation1977) also argues that police accountability should focus on approaches and procedures employed by the police during their work. It has been further contended that accountability also extends to ensuring that enormous power conferred to the police is legitimate and in ways that assure the public that the law guides police relations whilst scrutinising their activities. Accountability also encompasses strategic communication, risk management and improving public trust through assurance (Kettl, 2000). Despite the growing debate on the need for police accountability, colonialism and the decaying culture of accountability appear to suggest that post-independence, the Nigerian police force has been marred by issues of poor police accountability, which undermines public confidence in the police (Akinyetun, Citation2022; Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021; Onyeozili et al., Citation2021).

The Nigerian authorities have made a concerted effort to statutorily regulate, and monitor police conduct apart from scrutiny from other civil societies that demand accountable policing (Odeyemi & Obiyan, Citation2018). Nevertheless, there are widespread excesses of the police, which borders on the effectiveness of external and internal oversight to ensure the police perform their duties transparently and accountably. As Olugbuo (Citation2018, paragraph 1) argues ‘the absence of a sense of accountability to the people has been the missing link between the Police and the people they serve in Nigeria.” To this extent, several attempts have been made by the Nigerian police internally to ensure accountability. It includes the Complaint Response Unit (CRU), established in 2015. The CRU is responsible for receiving public complaints concerning the inappropriate conduct of any police officer. In addition to the CRU, other internal channels of complaint exist, including the Public Complaint Bureau (PCB), the Provost Department) and the Force Criminal Investigation Department (FCID). Regarding external oversight, avenues include the Police Service Commission (PSC). The Police Service Commission Act 2001, which established the PSC, mandates the latter to appoint persons to offices other than the inspector general of police to exercise disciplinary control over any person holding an official position in the police force except the inspector general of police.

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) represents another external oversight established by the National Human Rights Act of 1995, as amended in 2010, with a mandate to protect all human rights. The Public Complaints Commission (PCC), mandated to control administrative excesses, including abuses of the law and non-adherence to the procedure, is yet another external organ saddled with accountability responsibility. Being a governmental organ, the PCC was established to address complaints made by aggrieved citizens in Nigeria against perceived administrative injustice. The PCC’s primary function also revolves around providing an impartial investigation on behalf of the aggrieved complainant as a result of government action or inaction or that of the local government or private companies (Onuoha & Okoro, Citation2021).

Despite the preceding complaint channels, gaps exist in the public and victims’ awareness of these avenues in Nigeria. The implication of this limited awareness is the #EndSARS mass protest, which represents the culmination of pent-up public frustration with the Nigerian police due to corruption, torture, and poor channels of accountability. The #EndSARS protest commenced on the 4th of October 2020 after a police officer under the SARS unit reportedly shot a young man in Ughelli, Delta state (Iwuoha & Aniche, Citation2021). The incident video circulated and became a trend on social media, leading to a nationwide protest within a few days (Abimbade et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021). States like Lagos became the centre of convergence using significant spots such as the Lekki Toll gate.

The attempt to address the situation led to the Judicial Panel of Inquiry’s establishment to address the Lekki toll gate shooting of civilians in Lagos State. The Commission, through its inquiry, noted that issues of proper public sensitization and orientation by the Federal Government about the progress made over the years on the reformation of the Nigeria Police Force triggered public discontent. According to the Commission, this is given the years of advocacy and dialogues coupled with persisting outrageous and gross human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, torture, robbery, unlawful arrest, extortion, and detention, among others, with impunity, being perpetrated by the Police. These collectively forced the youth to express their constitutionally protected Rights and Freedom of Expression and Assembly to demonstrate their discontent from the 8th–20th October 2020. To this extent, the Judicial Panel of Inquiry (Citation2020) reports that:

The Panel found that the Nigerian Police Force deployed its officers to the Lekki Toll Gate on the night of the 20th October, 2020 and between that night and the morning of the 21st of October, 2020, its officer shot at, assaulted and battered unarmed protesters, which led to injuries and deaths. The police officers also tried to cover up their actions by picking up bullets (2020, p. 14).

Methodology

Trial design

This is a feasibility study that adopts a single arm mixed-method design involving the collection of data using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The trial was conducted between January 2022 and July 2022. The trial adopts the Legal Education-informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (LiCBT) to assess its feasibility and cultural appropriateness for public members who are victims of police misconduct and inhumane treatment. In total, 24 participants were recruited for the study, and a previous study has highlighted its sufficiency and appropriateness for a feasibility or pilot trial (Julious, Citation2005). The sample size is also justified as a feasibility study is: “to assess whether it is possible to perform a full-scale study” (Whitehead et al., Citation2014, p. 131). Our study did not engage in any formal hypothesis testing or control group because pilot or feasibility studies aim not to test hypotheses about the intervention’s effects but to assess the acceptability and feasibility of an approach to be used before being deployed in a larger-scale study (Eldridge et al., Citation2016). In essence, the underlying question our study seeks to answer is whether or not, the LiCBT is feasible in terms of recruitment, retention, acceptability and victims/public satisfaction with the intervention to improve confidence in the Nigerian police.

Prior to the commencement of the trial, we sought and were granted ethical approval by the Teesside University Research Ethics Committee in the UK (Ref: 2021 Dec 7642 Ike). The trial was conducted in line with global best practices and the Declaration of Helsinki. The CONSORT guidelines for reporting trials also informed the study.

Instruments

The primary outcome measures include the reduction of negative disposition towards the police alongside increased knowledge of the Legal avenues of complaint channels. The instruments used to measure these outcomes are described below and comprise the Legal Consciousness Questionnaire (LCQ), the PHQ-9, the Legal-Informed Awareness of Complaint Channel Scale (LACCS) and questions on the satisfaction with the intervention. The Legal Consciousness Questionnaire (LCQ) is informed by legal axioms connected with norms and values that are objectively enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the global community and reflected in the constitutional rights and freedoms of citizens (Molotova et al., Citation2020). The culturally adapted LCQ involved an 8-item question with frequency ranging from completely disagree (0) to agree (5).

The PHQ-9 Scale is a 9-item scale that assesses moods, including whether participants are feeling down, depressed or hopeless and have little pleasure in doing things. All items are rated on a frequency ranging from not at all (0), several days (1), more than half the day (2) and nearly every day (3). The PHQ-9 also have an overall rating of 27. With 1–4 indicating minimal depression, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 moderately severe depression and 20–27 severe depression. The Legal-Informed Awareness of Complaint Channel Scale (LACCS) is a 10-item scale measuring level of awareness of complaint channels with a rating of strongly disagree (0), disagree (1), agree (2) and strongly agree (3). The scale has an overall rating of 30, with 0–7 indicating poor knowledge, 8–15 (average knowledge), 16–22 (good knowledge) and 23–30 (excellent knowledge).

The participants were recruited via snowball sampling technique. Participants’ demographic characteristics comprised of public members who are victims (meaning that they have had previous experience of perceived police misconduct) and scored less than five on the culturally adapted Legal Consciousness Questionnaire (Molotova et al., Citation2020) used to measure their level of awareness. A score of less than 5 suggests they have poor knowledge of their legal rights and awareness of accountability channels. Depression was measured using the PHQ-9 Scale, as previous studies suggest that police brutality, including a perceived lack of accountability against police misconduct and torture, spurs depression among victims (Alang et al., Citation2021; Ike et al., Citation2023).

In addition to data collection using surveys, we also adopted a focus group, including individual interviews at the end of the intervention and three months follow-ups post-intervention. In assessing satisfaction with the intervention, we used the participant’s satisfaction questionnaire to assess significant areas of the intervention. It includes their overall rating of the sessions, facilitator’s performance, and overall intervention rating using a scale of 1–10, with 1–4 denoting poor rating, while 5–6 denotes okay and 7–10 signifies excellent rating. Other areas of satisfaction assessed included whether, as a participant, they felt the group discussions were interesting and informative and whether the activities and exercises enhanced their ability to learn the subject matter. We assess it via a scale with ratings, including strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree.

Settings and participants recruitment

The participants were purposively recruited using the researchers’ established networks with law firms, civil societies, non-governmental organisations and faith-based groups working with affected and self-identified victims in Delta State, Nigeria. The rationale for choosing Delta State as the location for data collection was because the state had been affected by widespread police brutality. It was the origin of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) killing that triggered the infamous #EndSARS protest in 2020 due to the shooting of a young man by the SARS police in Ughelli, Delta State (Abimbade et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021). To aid participants’ recruitment, the researcher initially approached relevant stakeholders (e.g., civil societies working with affected victims) and informed them about the research and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The contact information of the research team was also provided so those voluntarily interested in participating in the research will contact the research team to express their intention. A snowball sampling technique was also adopted where participants who were part of the study were asked to suggest other participants who had experience with the police and met the study’s inclusion criteria.

All participants in the study had to meet the inclusion criteria prior to taking part. The criteria for inclusion are that participants should be 18 years and above, able to provide full voluntary consent for their participation, are a resident of the trial catchment areas and able to complete a baseline assessment by scoring less than 5 for the culturally adapted Legal Awareness Scale (Molotova et al., Citation2020). The study was conducted in English. Participants were excluded from the study if they were less than 18 years old, unable to consent, had other significant physical or learning disabilities, were temporary residents and were not based in the trial catchment area.

In total, 24 participants met the study’s criteria, duly consented to take part in the study and were assigned to the LiCBT group. Of the 24, eighteen were females, while the other six were males. The rationale why females are more is that this group of people appears to have been more affected, given their vulnerable nature to challenge issues of alleged police unprofessionalism when compared to their male counterparts. In addition, given the purposive sampling method adopted, females were more because they also met the study’s inclusion criteria at the time of the recruitment. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 59. Nineteen of the participants indicated being employed or self-employed, amounting to 79.2%, while 5 participants, amounting to 20.8%, indicated being unemployed. Regarding the level of education, 21% indicated having obtained education up to the tertiary level (this includes a university degree, polytechnic, technical college and certificate from the College of Education). Three indicated their level of education as secondary (which implies GCSE or A-Level in the form of the West African Senior School Certificate or National Examination Council Certificate).

Intervention

Participants were all assigned to a single LiCBT group. The LiCBT intervention stems from previous literature and empirical research (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021; Ike et al., Citation2023). It was also culturally adapted using focus groups with affected victims and refined drawing on input from solicitors and community psychologists. The LiCBT intervention consisted of 12 group training sessions (lasting approximately 60 minutes each), and a session was delivered weekly online via Microsoft Teams for 12 weeks. Each session commences with an overview of the topic, followed by related activities such as short discussions, hypothetical case scenarios and compiling a list of potential actions to take in assessing channels of complaint to ensure accountability. A trained legal practitioner (barrister) delivered the session in conjunction with one research assistant, who was also trained in delivering the manual’s content before the intervention alongside inputs from a health specialist and psychologist. The 12 sessions covered the following topics as delineated in below:

Table 1. Topic covered in the Legal Education Informed Cognitive Behaviour Theraphy (LICBT).

Method of analysis

Quantitative Data Analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. Differences between the baseline, end of the intervention and three months follow-up data on key outcomes (e.g., statutes provision regulating the procedure for channelling complaints concerning police unprofessionalism and change in perspectives concerning awareness of access to justice for seeking redress) and socio-demographic variables at baseline were tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The main rationale for the test was to examine outcomes such as improvement in acceptance scores concerning trust in the police at different time points from baseline, end of the intervention and three months post-intervention.

The rationale for using the Wilcoxon test was also because our data/variable meets the underlying assumptions of the test. For example, our dependent variable was measured at an ordinal level. The independent variable in our study consists of two related groups, which means that the same subjects were present in both groups. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is also appropriate as it is a non-parametric equivalence of a paired samples t-test. In applying the Wilcoxon signed rank test, we created a variable and assigned a rank to each set of questionnaires. For example, for the PHQ-9, 1 was coded to represent minimal depression, with scores ranked from 1–4 to fall within this range. Two represent mild depression (with scores ranked between 5 and 9), while 3 represent moderate depression (10–14) and 4 moderately severe depression (15–19) and finally 5 severe depression (20–27). In terms of the LACCS, a ranking was also proffered, with 1 representing poor knowledge for participants within the range of 0–7 while 2 average knowledge (8–15) and 3 representing good knowledge (16–22) with 4 representing excellent knowledge (23–30). In terms of the LCQ, 1 represents poor knowledge (with scores ranging from 0 to 10 within this threshold) while 2 is average knowledge (11–20) and, 3 is good knowledge (21–30), and finally, 4 represents excellent knowledge (31–40). The Wilcoxon signed rank test formula was adopted for the calculation using the SPSS.

Qualitative analysis

Individual interviews and the focus group data were recorded and later transcribed from audio files into a word document in preparation for analysis. All participants’ identifiable information was deleted and replaced with pseudonyms. Thematic analysis from a social identity theoretical lens and critical realist perspective (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013) were adopted to analyse the qualitative data. Theoretically, the social identity theory posits that the group that people belong to forms an important part of self-esteem and pride (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). As such, social categorisation occurs because of how people categorise those not within their group as outgroups, explaining prejudicial attitudes toward others (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Murphy, et al., Citation2021). Within the context of our study, social identity is crucial to explaining the perceived in-group and outgroup identity where victims see the police as not part of them or not representing the interest of the masses. It is also important to add that victims may feel the police do not represent their individual interests either because there may be a difference between those individual interests and the interests of the masses, real or perceived. However, from a social identity context, we examined it from the group perspective rather than just a single victim. In essence, improving positive social identity constitutes one of the avenues for enhancing police public relations and trust building.

The six-step process enunciated by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) was adopted for the data analysis using thematic analysis. It involves familiarisation with the dataset through reading and re-reading the transcript to note initial thoughts at the first stage. The next step involves the generation of the initial code. We engaged in both semantic and latent levels of coding while staying close to the participants’ meaning and the data. In the third stage, we search for themes in the coded dataset. To achieve this, we reviewed each code to identify areas of similarities and overlap between the codes. Upon completing this stage, we moved on to the fourth stage, which involves reviewing potential themes by closely scrutinising each theme in relation to the coded data and the entire dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). We engaged in this stage to ensure quality checking and that the themes meaningfully capture the dataset. In stage five, we defined and named the themes by clearly stating what was specific and unique about each theme (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013) before we proceeded to stage six, which involved the production of the final analysed report.

Settings and participants

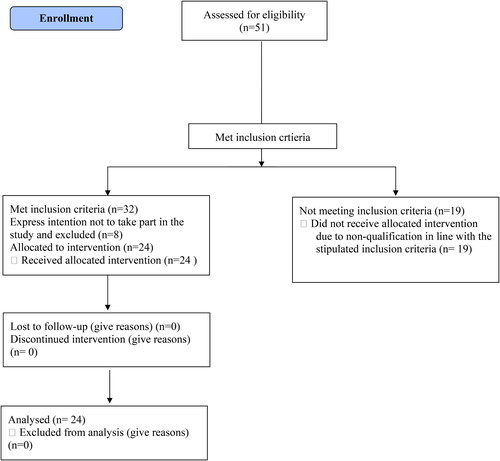

Our analysis aims to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the LiCBT trial. It also aims to examine the participants’ knowledge of the law, their rights and legal avenues for filing complaints and seeking redress against police misconduct, as well as changes in attitudes and positive dispositions towards the police. Based on the analysis, there was little difference in the participants’ socio-demographic variables, and the difference did not appear statistically significant. For example, at baseline, 12.5% of the participants indicated having secondary education, while 87.5% indicated having tertiary education (including university). For occupation at baseline, 79.2% indicated being employed, while 20.8% indicated being unemployed. At three months follow-up, only 4.2% indicated having secondary education, while 95.8% indicated having some tertiary education, including those who attended university. For occupation at three months follow-up, 87.5% indicated being employed. The participants were between the age range of 18 and 59 years. below provides a summary of the participants’ flow through the course of the study. Of the 51 participants approached, 32 met the inclusion criteria, with eight indicating their intention not to participate and thus excluded. Some of the reasons adduced for non-participation are the lack of availability to commit to the 12 sessions, not being available for follow-up, and personal reasons few indicated not willing to disclose. As illustrated in the figure below, twenty-four participants subsequently participated in the study.

Results

Overall, retention within the LiCBT trial was very good, with 22 of the 24 participants completing the 12 sessions and only a few (two participants) missing one or two sessions. In essence, acceptance of the LiCBT was good, with 96% of participants attending all sessions. In terms of satisfaction, the survey and qualitative data indicated a high satisfaction rate. Participants were asked during the survey statement such as “Overall, how would you rate the performance of the facilitator(s)?,” “Overall, how would you rate the sessions? Please tick a number.”, and “Overall, how would you rate the LiCBT Program? Please tick a number.” The response rate was on a scale of 1–4, indicating a poor rating, while 5–6 indicated okay/average rating, and 7–10 indicated excellent. In terms of rating of the LiCBT programme, 83.3% indicated excellent. For the facilitator’s performance, 87.5% indicated excellent, while the sessions received a rating of 83.3%, indicating excellence.

The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to test whether differences exist between the baseline, end of the intervention and 3-month follow-up when evaluating the participants’ legal awareness and knowledge of channels for accountability against police misconduct whilst reducing depressive tendencies (see ). The test is a non-parametric equivalence of a paired samples t-test which could be used for conducting repeated tests evaluating the efficacy of an intervention across time for ordinal variables and non-normally distributed data. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test revealed a statistically significant increase in knowledge of their legal rights (LCQ) from baseline (Md = 1.00) to end of intervention (Md = 4.00) with z = −4.427, and at three months follow up, z = −4.423. A slight drop is noted with z = −4.423 at 3 months; however, this appears not to impact the significance level. Concerning the LACCS scores, we observed a statistically significant increase in awareness of legal avenues of complaint channels from baseline (Md = 1.00) to end of intervention (Md = 4.00), z = −4.364 and 3-month follow-up (Md = 4.00), z = −4.434. For the PHQ-9, we observed some significant reduction in depressive symptoms from baseline assessment (Md = 4.00) to end of intervention (1.00), z = −4.0661, and three months follow up (Md = 1.00), z = −4.142. As such indicating the use of LiCBT is promising.

Table 2. Summary table showing LCQ, LACCS and PHQ-9 Wilcoxon Sign Rank Test scores across time.

As delineated in above, addressing victims’ needs through the promotion of awareness channels coupled with the incorporation of cognitive behaviour therapy intervention appears to show a promising result that could help build confidence in the police and potentially reduce negative thoughts towards the latter.

Findings

The findings of the qualitative ambit were based on participants’ experience of the LICBT intervention. The following main themes emerged, including poor experiences and harassment, the positive benefits of the programme and the need to extend the programme’s reach. In reporting the findings, all participants’ identifiable information and names have been deleted and replaced with pseudonyms.

Abuse of power and harassment

Prior to the intervention, a dominant theme in the dataset recounted by participants was the poor experience they encountered with the police. This was encountered from diverse perspectives, including harassment, abuse of power, extortion and arbitrary arrest. Commenting on the poor experience, one female participant said:

I have not really had any very good experience with the police. […] So, there was a time I carry my laptop around very well when I was learning coding and it was always a stress because anytime I see police people with the laptop, they will keep harassing me, saying where is the receipt? You stole the laptop! Call your parents! It is always harassment and I also remember sometime last year or two years ago, my fiancé is a computer engineer. So, every time maybe he goes to pick up a client’s laptop or returns it or even goes to buy, they [referring to the police] always harass him on the road. So, police wahala [problem] is just like I have never had any good experience with them.

Like my experience with the police, when my son was coming from Katsina when he was serving, the police, now hold him with his laptop and eh pepper. So, he has to call me that they hold him. They arrested him. I have to go and bail him. So, when I got there, I now said this is a youth corper, why are you people arresting him? They now said eh the laptop may be a stolen laptop and the pepper, like how many bags of pepper is stolen. I said ah ah let them call the corper eh… They now said no, they don’t need that one. So, I have to bail him. So that was the experience I have to bail my son and they said I must give them money first before they will release him. Then they now bring POS machine that I should put my ATM if I did not have the cash. So, that was my experience with the police.

Enlightenment

A recurrent pattern in our study’s dataset was the sense of enlightenment as expressed positive outcomes and feedback participants expressed concerning the LiCBT intervention upon completion. Most of the participants expressed views concerning the perceived impact of the intervention, especially as it relates to the awareness of their rights and complaint channels to ensure police accountability. Commenting on it, Adaeze, a female participant, opined that:

So, from this programme, first of all, I have learnt my rights and also why the police was like why it was brought about in the first place like their purpose. I never even knew that. Then, I have also learnt like in case I have any problem, the right place to channel my problem to, who to meet or who not to meet and when to stand my ground and all that. So, I am really grateful for the programme. It is a nice thing. (Adaeze)

When I get involved with the police, so I know the appropriate channel to take my complaint to all those things. So at least this programme is an interesting one to me. I also I learnt about the functions of the police […]. I have learnt so much, I also learnt about the functions of the police that gave them the power to carry out their task. […] I also learnt about their powers to arrest and investigate. (Alfred)

Human rights and accountability

A notable finding from the dataset was the participants’ awareness of their human rights and avenues for accountability. Human rights are inalienable, and adherence to such rights is required for effective policing devoid of abuse. Such awareness of the rights accrued to citizens as humans and what constitutes a legal breach of such rights are instrumental in creating a sense of being able to seek justice when police misconduct occurs. In essence, knowledge of legal channels of police accountability alongside notable human rights appears to foster a positive sense of awareness on the participant’s part. An extract from one of the male participants with direct experience of perceived poor policing practice noted that:

Yes! Let me just say that this program has really been educating, You know, and I really learned a lot about the police force, why it was created, human rights, the types of rights, socio-cultural rights, political rights and so on. So, it was really, really educating and to be honest, when this program comes to an end, I am really, really going to miss it. (Akpoghene)

So, the intervention, it actually covered areas whereby we can report the incidences, of whereby the police officers acted wrongly. So, we talked about different ways we can report on as we talked about from maybe from their website. They also have a public complaints unit of the police force. So that, we covered different areas whereby we can actually report any police officers who are behaving in an unprofessional manner. For me, my best session is actually learning about the different types of human rights (Edafe).

The program has been really enlightening and educative. In fact, I have really learnt a lot from the programme about the police, about my human rights. Eh, it has really been an interesting one, thank you. (Ruth)

Expansion of the programme’s reach

Another finding from our analysis was the perceived need to expand the intervention to reach people who could be suffering similar challenges and are unaware of their legal rights or even channels for accountability. The expansion was perceived positively and as a formidable aspect of change and reform. As one female participant commented:

I think it is very very Ok, You know, especially looking at the educative parts and also many times after listening to the lecture, I really sit down and wish more people come to know about what I am learning every day because like look at. Uh, I remember the day you talked about why Police was brought into existence. And also, it was really interesting to know that the unprofessionalism of this police there is a body you can report them to. So, I was always thinking, oh, I wish more people could get this information. (Erifeoluwa)

I think eh that you should expand the programme because so many people, they are not aware, and they do not know their rights. (Gloria)

Discussion and conclusion

Our study aimed to examine the feasibility in terms of retention and cultural acceptability of a Legal Education-Informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (LiCBT) intervention to improve victims’/public confidence in the Nigerian police. Drawing on a single-armed mixed-method design, the result of our trial showed that the intervention was feasible and acceptable. As the result section showed, there was a high participants’ retention rate (>96% retention; <4% attrition) across the 12 sessions of LICBT, with 83.3% rating of satisfaction and acceptability of the interventions with n = 24 participants completing all assessments at baseline, end of interventions and 3-months follow-up. The feasibility and acceptability of the intervention were predicted in a previous systematic of 11 studies highlighting the need for an intervention that “revolves around sensitisation of the public on police duties and avenues for seeking redress in the event of anomalies” (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021, p. 111).

Our study also indicated substantial median differences relating to the improvement of knowledge of the laws and avenues to seeking redress against police misconduct compared with the baseline data and the end of the intervention, including the three-month follow-up. This is as illustrated by the result from the LCQ from baseline (Md = 1.00) to end of intervention (Md = 4.00) with z = −4.427, and at 3 months follow up, z = −4.423. Police-public relations, as it relates to the awareness of avenues for accountability, has been an area often taken for granted within Nigeria. Previous studies have shown that issues of lack of accountability, perceived lack of trust, and corruption have historically posed concern and further heightened the public distrust gap and low police legitimacy (Akinlabi, Citation2022; Akintayo, Citation2019; Alemika, Citation1988). Of central concern is accountability; which previous studies have argued that having a well-structured internal policing control system with effective deterrence of indiscipline and corrupt practices could aid in preventing and detecting corruption and inappropriate behaviour among police officers (Bajramspahić & Muk, Citation2015, Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021). While these arguments highlight a significant concern, we are unaware of the use of LICBT to encourage confidence in the police and improve knowledge of legal channels of accountability nor the use of robust experimental design to test the intervention. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first trial in Nigeria and globally to investigate the LiCBT feasibility. Previous intervention studies on improving police-public relations have often sought to test interventions such as the efficacy of community policing using 18,382 citizens and 874 police officers in the global south (Blair et al., Citation2021). Others include mechanisms such as body-worn cameras to improve confidence in the police (Lum et al., Citation2019) and procedurally just dialogue focused on improving citizen perceptions of police legitimacy (Mazerolle et al., Citation2013). Our study indicated that delivering interventions that improve knowledge of legal education and awareness of access to legal platforms for police accountability may be significant in determining and assessing the efficacy and improving public confidence.

In terms of the qualitative ambit, prior to the intervention, participants recounted issues of abuse of power and harassment from the police. These issues were instrumental to their lack of confidence in the police. However, after the intervention, participants expressed satisfaction with the LiCBT, a sense of enlightenment alongside the positive benefit of the knowledge learnt and its application. Previous studies have shown that issues of lack of accountability and poor historical negative attributes toward the police compound public distrust for the former (Alemika & Chukwuma, Citation2000; Ike et al., Citation2021). Drawing on a historical understanding of why the police were formed coupled with the enlightenment of the purpose of the police, the participants understood the need to shift the negative understanding of policing to a more positive ambit. The aim was designed to address the negative ‘us vs them’ identity where the police were seen as the enemy to a more positive in-group identity to enhance police legitimacy.

Collectively, and in conclusion, we recommend a fully powered trial to determine the effectiveness and efficacy of LiCBT and address the limitations of our study. The rationale is that, firstly, our study is carried out in a single location and geopolitical zone (South-South), and the findings might not be generalisable to Nigeria’s broader six geopolitical zones. Secondly, given the design of our study as a single-armed feasibility mixed method trial, our sample size was small and not powered to infer the efficacy of the LiCBT. Thus, it is important to interpret effect size and median differences cautiously. Future studies could also introduce a randomised control trial design with a control group (e.g., Media orientation) directly compared to the experimental group (LiCBT). Our present study only assesses for the end of the intervention and three months follow-ups. Future studies could include a long follow-up period of six months and 12 months to see if the median difference and efficacy are sustainable alongside the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Finally, our present study only recruited those able to speak English. Future studies could include other participants who cannot speak English whose insights will also be relevant.

Notwithstanding our study’s limitation, it has demonstrated an original, significant and methodological contribution that tests the feasibility of LiCBT in improving confidence in the police through knowledge of awareness of legal channels for accountability. A policy implication and recommendation from our study is the need for the government, including civil society actors, to improve public awareness of legal accountability mechanisms and channels. To achieve this, more extensive sensitisation programmes is encouraged to be designed to reach the public through mediums such as the National Orientation Agencies on access to justice and available support channels in cases of police unprofessionalism. This is especially considering that poor channel of accountability could give rise to a lack of public trust, low police legitimacy and poor intelligence-sharing (Ike, Singh, Jidong, Ike, et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Imoudu, Citation2022; Onwuama et al., Citation2019; Shoyode, Citation2018). It also considers the depleted budget accrued to the police and the low police/public ratio. In essence, promoting interventions such as LICBT could provide a cost-effective mechanism for building confidence in the police and reducing public frustration, as demonstrated in the mass #EndSAR protest.

Acknowledgement

The study acknowledges the grant awarded by the American Psychology-Law Society (AP-LS) Early Career Professionals Committee, which aided the project’s successful delivery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tarela Juliet Ike

Tarela Juliet Ike is a Senior Lecturer in Criminology and Policing with research interests and specialism in policing, terrorism, counterterrorism, and peacebuilding in post-conflict settings. Tarela is a multiple award-winning researcher for research excellence.

Dung Ezekiel Jidong

Dung Ezekiel Jidong is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology with expertise in mental health within the African and Caribbean contexts. Dung is a multiple award winner of the British Psychological Society delegate choice poster prize.

Evangelyn Ebi Ayobi

Evangelyn Ebi Ayobi is a research assistant.

References

- Abimbade, O., Olayoku, P., & Herro, D. (2022). Millennial activism within Nigerian Twitterscape: From mobilization to social action of# ENDSARS protest. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 6(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100222

- Agbiboa, D.E., (2015). “Policing is not work: it is stealing by force”: Corrupt policing and related abuses in everyday Nigeria. Africa Today, 62(2), 95–17. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.62.2.95

- Ahire, P. T. (1991). Imperial policing: The emergence and role of the police in Colonial Nigeria 1860–1960. Open University Press.

- Akinlabi, O. M. (2017). Why do Nigerians cooperate with the police?: Legitimacy, procedural justice, and other contextual factors in Nigeria 1. In Police–citizen relations across the world (pp. 127–149). Routledge.

- Akinlabi, O. M. (2022). Use of force, corruption, and implication for trust in the police. In Police-citizen relations in Nigeria (pp. 97–125). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Akinlabi, O. M. (2017). Do the police really protect and serve the public? Police deviance and public cynicism towards the law in Nigeria. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 17(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895816659906

- Akintayo, J. (2019). Community policing approach: Joint task force and community relations in the context of countering violent extremism in Nigeria. African Journal on Terrorism, 8(1), 137–156.

- Akinyetun, T. S. (2022). Policing in Nigeria: A socioeconomic, ecological and sociocultural analysis of the performance of the Nigerian Police Force. Africa Journal of Public Sector Development and Governance, 5(1), 196–219. https://doi.org/10.55390/ajpsdg.2022.5.1.9

- Alang, S., McAlpine, D., & McClain, M. (2021). Police encounters as stressors: Associations with depression and anxiety across race. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 7, 237802312199812. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023121998128

- Alemika, I., & Chukwuma, I. (2000). Police-community violence in Nigeria. Centre for Law Enforcement Education (CLEEN)/National Human Rights Commission (NHRC.).

- Alemika, E. E., & Chukwuma, I. C. (Eds.). (2003). Civilian oversight and accountability of police in Nigeria. Centre for Law Enforcement Education (CLEEN).

- Alemika, E. E. (1988). Policing and perceptions of police in Nigeria. Police Studies: International Review Police Devevelopment, 11, 161.

- Amnesty International. (2015). Nigeria: Stars on their shoulders: Blood on their hands: War crimes committed by the Nigerian military.

- Amnesty International. (2020). Nigeria: Time to End Impunity, Torture and Other Violations by Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). Amnesty International. file:///Users/teamsproject/Downloads/amnesty%20international%20policing.pdf

- Aniche, E. T., & Iwuoha, V. C. (2023). Beyond police brutality: Interrogating the political, economic and social undercurrents of the# EndSARS protest in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 58(8), 1639–1655. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221097673

- Audu, A. M. (2016). Community policing: Exploring the police/community relationship for crime control in Nigeria. The University of Liverpool.

- Ayodele, J. O., & Aderinto, A. A. (2014). Public confidence in the police and crime reporting practices of victims in Lagos, Nigeria: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 9(1), 46–63.

- Azuwike, O. D., & Eboh, E. A. (2021). Geographical issues in Nigerian army’s involvement in grazing land resource contestation, public pacification and cattle protection. African Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 11(2), 274–290.

- Bajramspahić, D., & Muk, S. (2015). Internal control of police – comparative models. Institut Alternativa: Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Retreived March 27, 2024 from https://www.osce.org/montenegro/138711

- Bent, A. E. (1974). The politics of law enforcement: Conflict and power in urban communities Toronto. Lexington Books.

- Blair, G., Weinstein, J. M., Christia, F., Arias, E., Badran, E., Blair, R. A., Cheema, A., Farooqui, A., Fetzer, T., Grossman, G., Haim, D., Hameed, Z., Hanson, R., Hasanain, A., Kronick, D., Morse, B. S., Muggah, R., Nadeem, F., Tsai, L. L., … Wilke, A. M. (2021). Community policing does not build citizen trust in police or reduce crime in the Global South. Science (New York, N.Y.), 374(6571), eabd3446. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3446

- Bond-Fortier, B. J., & Nader, E. S. (2022). Testing the effects of a problem-solving policing strategy on crime outcomes: The promise of an integrated approach. Police Quarterly, 26(1), 54–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/10986111211060025

- Braga, A. A., MacDonald, J. M., & Barao, L. M. (2021). Do body-worn cameras improve community perceptions of the police? Results from a controlled experimental evaluation. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 19(2), 279–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09476-9

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Collazo, J. (2022). Adapting trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy to treat complex trauma in police officers. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00770-z

- Daniels, F. A. (2012). A historical survey of amalgamation of the northern and southern police departments of Nigeria in 1930. European Scientific Journal, 8(18), 205–217.

- Ekwunife, R. A., Ononiwu, A. O., Akpan, R. E., & Sunday, H. T. (2021). EndSARS protest and centralized police system in Nigeria. Global encyclopaedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer Nature.

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PloS One, 11(3), e0150205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Emoedumhe, I. M., Obieshi, E., Ogbemudia, I. O., & Aidonojie, P. A. (2024). Catalyzing change: Analyzing the dynamics and impact of endSARS protests in Nigeria. KIU Journal of Humanities, 8, 35–49.

- Goldstein, H. (1977). Policing a free society. Ballinger.

- Goldsmith, A. (2005). Police reform and the problem of trust. Theoretical Criminology, 9(4), 443–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480605057727

- Home Office. (2023). Police officer uplift, final position as at March 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-officer-uplift-final-position-as-at-march-2023/police-officer-uplift-final-position-as-at-march-2023

- Human Rights Watch. (2021). Nigeria: A year on, no justice for #EndSARS Crackdown. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/10/19/nigeria-year-no-justice-endsars-crackdown

- Idowu, A. O. (2016). Security agents’ public perception in Nigeria: A study on the police and the vigilante (neighborhood watch). Journal of Political Studies, 23, 481.

- Ikime, O. (1966). The anti-tax riots in Warri province, 1927-1928. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 3(3), 559–573.

- Ike, T. J., & Jidong, D. E. (2023). Victims’ experiences of crime, police behaviour and complaint avenues for reporting police misconduct in Nigeria: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 18(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2022.2150091

- Ike, T. J., Jidong, D. E., Ike, M. L., & Ayobi, E. E. (2023). Public perceptions and attitudes towards ex-offenders and their reintegration in Nigeria: A mixed-method study. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958231181987

- Ike, T. J., Jidong, D. E., Ike, M. L., & Ayobi, E. E. (2024). Insecurity, counterterrorism and the use of private military and security companies in Nigeria: A qualitative study. Journal of Asian and African Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096241243062

- Ike, T. J., Antonopoulos, G. A., & Singh, D. (2022). Community perspectives of terrorism and the Nigerian government’s counterterrorism strategies: A systematic review. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 174889582211100. https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958221110009

- Ike, T. J., Singh, D., Jidong, D. E., Murphy, S., & Ayobi, E. E. (2021). Rethinking reintegration in Nigeria: community perceptions of former Boko Haram combatants. Third World Quarterly, 42(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1872376

- Ike, T. J., Singh, D., Jidong, D. E., Ike, L. M., & Ayobi, E. E. (2021). Public perspectives of interventions aimed at building confidence in the Nigerian police: A systematic review. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 17(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2021.1892167

- Imoudu, M. (2022). Post Endsars protest: Exploring subjective perception of police victims in Lagos, Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 13(3), 30–30. https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2022-0021

- Iwuoha, V. C., & Aniche, E. T. (2021). Protests and blood on the streets: Repressive state, police brutality and# EndSARS protest in Nigeria. Security Journal, 35, 1102–1124.

- Jesilow, P., Meyer, J., Parsons, D., & Tegeler, W. (1998). Evaluating problem-oriented policing: a quasi-experiment. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 21(3), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639519810228750

- Jidong, D. E., Ike, J. T., Husain, N., Murshed, M., Francis, C., Mwankon, B. S., Jack, B. D., Jidong, J. E., Pwajok, Y. J., Nyam, P. P., Kiran, T., & Bassett, P. (2023). Culturally adapted psychological intervention for treating maternal depression in British mothers of African and Caribbean origin: A randomized controlled feasibility trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(3), 548–565. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2807

- John, M. D. (2017). Public perception of police activities in Okada, Edo State Nigeria. Covenant Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 8(1), 29–42.

- Julious, S. A. (2005). Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 4(4), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.185

- Kettl, D. F. (2000). The global public management revolution: A report on the transformation of governance. Brookings Institution Press.

- Khan, S., Ahmed, A., & Ahmed, K. (2021). Enhancing police integrity by exploring causes of police corruption. Management Science Letters, 11(6), 1949–1958. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2021.1.006

- Lagos State Judicial Panel of Inquiry on Restitution for victims of SARS related Abuses and Other Matters. (2020). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vtgUdyn5CQLnuyAT2JHPcpDg04qkaLdO/view

- Louis, U. N., Eunice, A., Jacob, A., Nnenna, C., & Abdullahi, A. (2024). Effect of motivation on job satisfaction and performance: A study of Nigeria Police Force. NG Journal of Social Development, 13(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.4314/ngjsd.v13i1.4

- Lum, C., Stoltz, M., Koper, C. S., & Scherer, J. A. (2019). Research on body-worn cameras: What we know, what we need to know. Criminology & Public Policy, 18(1), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12412

- Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

- McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (2021). Thoughts and feelings: Taking control of your moods and your life. New Harbinger Publications.

- Molotova, V., Molotov, A., Kashirsky, D., & Sabelnikova, N. (2020). Survey for assessment of a person’s legal consciousness: development and preliminary validation. Behavioral Sciences, 10(5), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10050089

- Monaghan, J. (2022). Broken windows, naloxone, and experiments in policing. Social Theory and Practice, 48(2), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract202231157

- Odeyemi, T. I., & Obiyan, A. S. (2018). Digital policing technologies and democratic policing: Will the internet, social media and mobile phone enhance police accountability and police–citizen relations in Nigeria?. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 20(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355718763448

- Olugbuo, B. C. (2018). Building trust between people and police in Nigeria. CLEEN Foundation.

- Onwuama, O. P., Ajah, B. O., Asadu, N., Ebimgbo, S. O., Odili, A., & Okpara, K. C. (2019). Public perceptions of police performance in crimes control in Anambra state of Nigeria. African Journal of Law and Criminology, 9, 17–26.

- Onyeozili, E. C., Agozino, O., Agu, A., & Ibe, P. (2021). Community policing in Nigeria: Rationale, principles, and practice. Virginia Tech Publishing.

- Onuoha, F. C., & Okoro, T. C. (2021). Misconduct and disciplinary measure in the Nigeria Police Force: An Assessment. CLEEN Foundation. file:///Users/teamsproject/Downloads/CLEENPoliceMisconductOnuoha.pdf

- Shodunke, A. O. (2023). Protection or predation? Examining COVID-19 policing and the nuances of police corruption in Nigeria. Policing and Society, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2023.2285790

- Shodunke, A. O., Oladipupo, S. A., Alabi, M. O., & Akindele, A. H. (2023). Establishing the nexus among mob justice, human rights violations and the state: Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 72, 100573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2022.100573

- Shoyode, A. (2018). Public trust in Nigerian police: A test of police accessibility effects. Journal of Social Science Studies, 5(2), 1.https://doi.org/10.5296/jsss.v5i2.12721

- Tamuno, T. N. (1970). The police in modern Nigeria 1861–1965. Ibadan University Press.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- The Judicial Panel of Inquiry. (2020). Lagos state judicial panel of inquiry on restitution for victims of SARS related abuses and other matters.

- Tolin, D. F. (2024). Doing CBT: A comprehensive guide to working with behaviors, thoughts and emotions. Guilford Publications.

- Usman, D. J. (2019). Public perceptions of trust in the police in Abuja [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Glasgow.

- Whitehead, A. L., Sully, B. G., & Campbell, M. J. (2014). Pilot and feasibility studies: is there a difference from each other and from a randomised controlled trial? Contemporary Clinical Trials, 38(1), 130–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.001

- Williams, A., & Paterson, C. (2021). Social development and police reform: Some reflections on the concept and purpose of policing and the implications for reform in the UK and USA. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 15(2), 1565–1573. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa087

- Zbytovsky, J., & Prouza, J. (2024). Towards “modern” counterinsurgency in Sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learnt from Nigeria and Mozambique. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 35(2), 256–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2023.2298707