Abstract

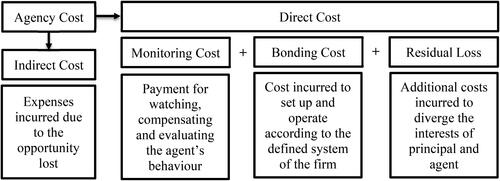

The aim of this study is to revisit the concept of the separation between ownership and control through reviewing studies on agency theory, governance, and corruption. This study applies integrative literature review as research method where the arguments and counterarguments are derived from existing studies. Relevant literature is identified and read in detail using the selected review strategy. The principal goal of the study is to develop an inventory surrounding the key themes of governance, corruption, and agency theory. None of the existing studies addresses the interrelationships between agency theory, corruption, and corporate governance. This study, thus, fills the gap exploring the theoretical and empirical evidence studying the bibliometric sources. The study finds evidence in support of changing ownership pattern from diffuse to concentrated and argues that the change has caused corruption due to deepening agency crisis. The study also finds that the extant literature focuses on applied areas which calls for further studies on core areas. Incorporating the concept espoused by Berle and Means, this study brings practical implication of agency theory in real life and extends the applicability of the concept.

1. Introduction

The theoretical basis of corporate governance dates back to the work of Berle and Means (Citation1932), who advanced the concept of separating ownership from control in relation to large US organisations. They found that the ownership of capital was highly concentrated in the hands of a few organisations with significant economic power. These companies grew larger, and the original owners found it difficult to maintain majority control through shareholdings as stocks were held by smaller shareholders to a larger extent. This led to the usurpation of shareholder power and control by company managers busy running day-to-day operations. Managers are motivated by their own interests which are more often at odds with that of shareholders and owners. They prioritize reinvesting profits rather than distributing them among owners. In some extreme cases, even they seek their own benefits. Managers have been driven by a self-motivating oligarchy with no accountability to the owners they represent. This position can not only be detrimental to the company but also has negative economic and social consequences (Berle & Means, Citation1932). Since then, corporate governance has received special attention from various divergent group of stakeholders. Research community has taken special attention of different dimensions of governance with divergent contextual backgrounds. Studies vary greatly in terms of the scope of studies stretching from the factors affecting governance thinking to consequences of non-compliances with the governance codes. Drawing from wider perspectives, this study makes a connection of corporate governance with agency theory and corruption to bring renewed attention.

The agency relationship in modern corporate world highlights various scenarios with potential dilemmas. One of the very core considerations of governance studies rests on the study of transaction cost. Coase (Citation1937) argued that transaction cost is reduced if authority is given to one set of party or manager to transact business specific decisions. It is the contractual authority which defines the firm. Transaction cost economics elaborates on the incentives and focuses on internal governance structures that constitute the firm as an internal capital market (Rowlinson et al., Citation2006). Concentrating authority into the hands of a few managers can lead to other costs such as errors or expropriation of firm assets by controlling managers. It may also lead to the expropriation of minority shareholders (Ogabo et al., Citation2021). As a result, principal-agent problems develop a fundamental basis of corporate governance perspective of agency problem. The problem arises when both parties maximize their own utility. It increases the likelihood that the agent and principal do not share the same interests or goals, and so it is logical to assume that the agent may not be acting in the principal’s best interest. This is the foundation on which the governance comes under threat and needs to be guided, monitored, and controlled. Governance eventually plays a mediator role between principal and agent to bring congruence.

Contracts are used to establish good corporate governance and ensure managers do not expropriate or waste funds. It clarifies the role and relationship between the managers and the owners and defines what managers can do with the funds. Ideally, contracts would be complete, but it is not always possible to foresee and anticipate future problems or contingencies. Therefore, managers always have some residual control rights to make executive decision when something outside of the original contract occurs. In addition, it is not always possible or practical for managers to ask or consult shareholders. Because managers are experienced and specialized in their role, it may not be feasible or useful to ask shareholders to make business decisions. Managers therefore end up with further residual control rights. Furthermore, contracts can never be over-interpreted if they ever have to be enforced by courts (Grossman & Hart, Citation1986; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). Governance codes are mostly used as a legitimate form of contract which clearly spells out the duties and responsibilities of stakeholders connecting with governance mechanism. This study, thus, highlights the importance of governance in consolidating the interest of the principal and agent.

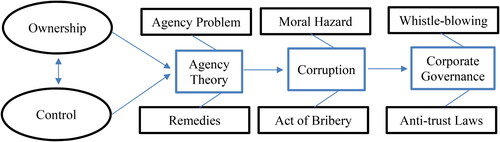

Incentives and other mechanisms can be used to monitor managers and limit their deviant activity. Such monitoring would lead to additional costs for clients and agents. It is also possible to enter into contracts (bonding cost) with managers to guarantee that they would not harm the owners, if this is the case the principal owners demand compensation for it. The agency relationship causes positive monitoring and bonding cost almost all cases. Despite the above measures, there will still be some divergence between the agents’ actions and the principals’ interests. The principals’ monetary cost borne due to this divergence is the “residual loss” to the principal’s value or welfare. Thus, Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) proposed three components of agency costs, namely, monitoring cost, bonding cost to agents and residual loss from decision making which are shown in below. In a study, ElKelish (Citation2018) finds agency costs having a significant negative impact on corporate governance risk across countries. The principal or firm will find a contract that is in balance and weighs cost and benefits. This tie neatly with the transaction cost view of Coase (Citation1937) that firm boundaries are where the marginal cost saving from transacting within the firm equals the rigidity costs in tackling the agency issues and errors made by the agent.

Figure 1. Elements of agency cost (Source: adapted from Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976).

The trade-off between costs and incentives needs to be carefully analysed to check possible governance crisis. Absence of incentives gives entry of corruption in corporate affairs. Analysis of the consequential costs of separation of ownership and control becomes more critical when corruption becomes a recurring event (Wawrosz, Citation2022). It sounds undesirable, but the reality is that the regulatory initiative fails to establish financial discipline, which is reflected in more frequent revisions and corrections to regulations, rules, and policies. Many changes have occurred in the global marketplace since Berle and Means (Citation1932) proposed the separation of ownership and control, which was strongly influenced by the ownership structure of large US corporations at the time and the stock market debacle. In this background, this study aims to develop a bibliometric record covering agency theory, governance and corruption in absence of similar studies. In this study, we find this as a potential research gap and develop an archival record on the revisions that is resulted since Berle and Means introduced the concept. The incremental contribution of this study is to develop an inventory on such relationship based on the findings of various studies done in different context with new research agenda. Based on an integrative literature review, this article develops a renewed research context in line with the following research questions:

RQ 1: What is the status of separation between ownership and control?

RQ 2: Is there any connection between agency theory, corruption, and governance?

RQ 3: How does diffused ownership impact agency problem?

RQ 4: What is agency problem and what are the possible remedies?

Existing corporate governance literature focuses on what is known as agency theory. The theory addresses issues in corporate governance, including those related to corruption. The present study also begins with a description of agency theory. However, it expands the scope of agency theory by introducing its application in a broader social context (particularly in real-life situations) and argues that this area requires additional emphasis to initiate new studies to update the literature bring to. Drawing on existing theoretical discourse and available empirical study’s findings, this study develops the epistemological background on which the theoretical foundation of the study rests. The remaining discussion is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses literature review while Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 covers analysis and results. Discussions are presented in Section 5, followed by research limitations and the identification of new research areas in Section 6. Finally, it ends in Section 7.

2. Literature review

Studies on corporate governance are abundance in literature. It began with the concept of the separation of management from owners. The separation between ownership and control (Berle & Means, Citation1932) gets popularity in literature as Agency Theory. The fundamental governance theory underpinning ownership structure is the agency theory (Ogabo et al., Citation2021). It refers to the contractual view of the firm (Coase, Citation1937), where transaction costs exist in the real world. The contract between the principal and manager is very important to ensure a precaution against possible confliction. However, it was previously ignored by the neoclassical literature. An agency relationship arises when the principal (owner) engages the agent (manager) to act on his behalf and also delegates decision-making authority to the agent (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). It is a question of trust on part of the principal in terms of the ability and interest of the agent to act for the best interest of the principal. Corruption results from the potential breach of trust, the fiduciary relationship (Johnson, Citation2019).

Separation of ownership and control requires good governance and involves various mechanisms within the institution and in the marketplace to ensure good governance and reduce agency problems (Dockery et al., Citation2012; Farooq et al., Citation2022). A strong mechanism of corporate governance can help bridge the gap between management and shareholders (Sehrawat et al., Citation2019). It can minimize agency costs as investors (particularly institutional investors) like to invest in well-run companies (Mehmood et al., Citation2019). Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) also mention different corporate governance mechanisms including legal and economic perspectives. The competitive nature of markets for raising the cheapest debt capital would allow governance without the need for competitive reforms to reduce costs and accept best corporate practices (Alchian, Citation1950; Stigler, Citation1958). However, Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) point out that this theory would not address the problems of corporate governance, since competitive markets can reduce the total amount subject to managerial expropriation. But it doesn’t stop managers from seizing companies’ competitive returns. Therefore, corporate governance requires different economic and legal mechanisms and cannot simply be left to competitive market forces (Barros et al., Citation2019).

Research supports the use of incentives to control the behaviour of corporate managers in their possible expropriation attempts. Various incentive contracts (such as share ownership, stock options, and threats of dismissal) can be used to align manager and owner interests (Fama, Citation1980; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) focused on the incentives faced by both the principal and the agent to mitigate potential divergences between them. Fight against corruption is strongly connected with the incentive mechanisms. Thus, the code of governance in different jurisdictions finds resemblances with those of anti-corruption. Corruption is found deeply rooted in countries around the world and these countries suffer from economic development, lack of democracy, and compromising social justice and the rule of law (Al-Faryan & Shil, Citation2023).

Developed countries have studied the consequences of bad governance and the fall of corporate giants as a result of corporate scandals further compel such countries to develop stringent codes of governance. The traditional view of agency relationship based on ownership structure has been reformed resulting reforms in governance requirements across countries. Al-Faryan and Shil (Citation2023) argue that lack of governance leads to the high possibility of corruption in the absence of accountability and transparency. Absence of governance mechanism widens the gap between the owners and managers which develops agency crisis and increases agency costs significantly. This wide dispersion also develops the possibility of corruption in corporate management. Studies consider the connection of corporate governance with firm performance (Guluma, Citation2021), agency cost (Li, Citation2020), Polity (Al-Faryan & Shil, Citation2023), and many other factors. Several empirical studies have documented the costs of separation between ownership and control like self-interest actions involving capital structure (Leland, Citation1998), dividend policy decision (Fenn & Liang, Citation2001), executive remuneration (Hartzell & Starks, Citation2003), mergers and acquisitions (Masulis et al., Citation2009), earnings management (García-Meca & Sánchez-Ballesta, Citation2009), and the issue of shares (Barclay et al., Citation2007).

On fall of Enron and introduction of SOX 2002, the governance research has witnessed a sudden jerk (Driel, Citation2019). Stringent codes are developed, implementation is monitored and certified, ownership structure is revisited, fraud and expropriation are checked. However, the studies are widely scattered, and wide varieties of issues are covered considering the contextual background of various studies. There is a dearth of studies that connect Governance with agency costs and corruption and thus, this study sheds light on this issue.

3. Research methodology

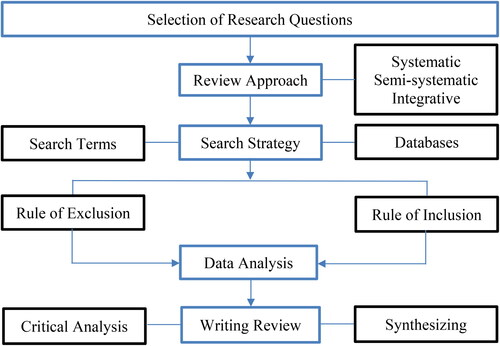

This study uses the literature review method to answer the research questions. Literature review method is one of the best methodological tools to find answers to a variety of research questions (Snyder, Citation2019). This study develops a solid foundation to advance knowledge of agency theory by confirming findings and perspectives from various published works. To emerge something beyond replication of previous results, a high-quality literature review needs to uncover mysteries on choosing relevant articles to gather data and additional insights (Palmatier et al., Citation2018). Through this method, our special focus is on (a) discussing relevant literature in selected areas, (b) identifying gaps in existing research, and (c) creating new research agendas. To assess, analyse, and synthesize the relevant literature on agency theory, we used integrative reviews to develop new theoretical frameworks and perspectives (Torraco, Citation2016). To overview the existing body of knowledge, most integrative reviews intend to consider mature issues. It aims to critically review and re-conceptualize existing knowledge so that an extension of the theoretical basis of the selected topic can be undertaken for further exploration (Snyder, Citation2019). This study is no exception. Our integrative review follows the below steps ().

Figure 2. Literature review method (Source: Shil & Chowdhury, Citation2024).

We begin with selecting few research questions (we have identified and presented few research questions in introduction section). Integrative review allows either narrow or broadly focussed research questions. After the identification of research questions and the selection of an overall review approach, a search strategy needs to be finalized for identifying relevant literature (Snyder, Citation2019). A search strategy encompasses the selection of search terms and databases and deciding on criteria for inclusion and exclusion. We have identified four search terms, e.g. agency theory, corruption, corporate governance, and remedies of agency problem. We have selected six academic databases, e.g. Elsevier, Emerald, JSTOR, Springer, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis for selecting relevant articles. However, it becomes difficult for us to locate appropriate articles that will help us to proceed with our research questions. Two reviewers have been recruited to help us with the process. We have later chosen the rules for inclusion considering only specific journal with mentioning the time period. It also fails to serve our purpose. We may end up with a very flawed or skewed sample if we limit our selection to some specific journals, years, or even search terms. We may also miss studies that contradict other studies or would have been more relevant to our case (Snyder, Citation2019). It may provide false evidence of a specific effect or even identify wrong gaps in the literature. We have finally selected Google Scholar database and use the selected search terms to identify relevant works for our study.

A pilot test of the review process and protocol is important while conducting the review. The review process needs validation on a smaller sample for possible adjustments, if necessary, before initiating a thorough review. It may even take several adjustments to get the desired results. To ensure the quality and reliability of the search protocol, we utilized the expertise of two reviewers. Since the search results yield many materials, reviewers are advised to read the abstract of each paper before selecting the article for thorough review. Later, the researchers sit down with the reviewers to carry out the review step by step; (a) reading the abstracts first for the initial selection and (b) reading the full-text articles later before the final selection (Snyder, Citation2019). To identify other potentially relevant articles, the researchers also checked the references of selected articles as an additional strategy.

Once final sample is selected, the important phase of literature review begins with the deployment of specific technique to conduct an analysis. An integrative review doesn’t follow any standard for data analysis (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). It may follow descriptive pattern presenting information, such as authors with years published, kind of study, topic, including major findings. It may sometimes present central idea or theoretical perspective considered in the studies to conceptualize for general understanding. The final structure of a review article is based on the selected approach which dictates the kinds of information required and the level of details. While writing the review, we make an integration of historical analysis within a research field (e.g. Carlborg et al., Citation2014), a plan for further research (e.g. McColl-Kennedy et al., Citation2017), a theoretical model or categorization (e.g. Snyder et al., Citation2016; Witell et al., Citation2016), and evidence of an effect (e.g. Verlegh & Steenkamp, Citation1999). We have developed the following conceptual framework () to support us in writing integrative review in next section.

4. Analysis and results

This analysis is the outcome of integrative literature review. Our thematic analysis results few key themes with reference to which we have structured the analysis. The separation between ownership and control resulted agency theory, which has been extensively researched during recent decades. Corruption becomes a big industry driven mostly by agency problems and regulators are looking for solutions that have spawned the concept of corporate governance. In this section, relevant literature is presented in line with research questions and selected themes.

4.1. Separation of ownership and control: synthesizing Berle and Means

In the Modern Corporation and Private Property, Berle and Means (Citation1932, Citation1968) introduced the concept of Agency Theory bringing a separation of ownership and control, which has become an area of debate, criticism, and research. The book comprises an analysis of large US corporations, particularly of the USA’s then 200 largest non-financial companies, most of which, in the early decades of the century, had gross assets of over US$100 million. The book’s thesis is twofold. First, there is a difference between law and practice. The law demands that corporations should behave in such and such a way that does not necessarily imply that they do. In other way, it is to fall prey to the naturalistic fallacy, namely, to derive is from ought (Wormser, Citation1933). The real world of business is different from the paper world of statute. The book’s second point follows from the first. In large corporations, ownership is separate from management. Ownership comprises shareholders, most of whom have little to no direct control of the company. Management is performed by company executives, who may or may not have shares in the company. In any event, the interest of shareholders is different from that of managers. The interest of shareholders is to receive as much return from their investment as possible; the interest of managers is to mulct as much as they can. Managers may mulct their companies by awarding themselves needlessly high pay; by shirking; by awarding themselves undeserved perquisites; or by engaging in such non-profit making activities as empire-building and needlessly increasing sales (see, e.g. Fama, Citation1980). Given that immediate control of the company rests with managers, they have the power to mulct vast amounts from the companies that employ them.

Rather introducing agency theory, Berle and Means (Citation1968) analyse the problem of large corporations. It brings an integrated study covering issues like an empirical analysis of large corporations, an analysis of corporate law and a theoretical analysis of power with reference to the large corporations in the USA. Berle and Means (Citation1968) provide details of the percentage of share ownership of large corporations in the USA. It turns out, for instance, that the 20 largest shareholders of the Pennsylvania Railroad Co., as of 31 December 1929, between them held a mere 2.70% of total shares, and the largest shareholder held only 0.34% of total shares (Berle & Means, Citation1968, p. 79). It confirms that, in modern corporations, ownership is diffuse, not concentrated. Moreover, in the Pennsylvania Railroad Co., not one director or other senior management held a substantial percentage of shares in the company. Not all companies in the early decades of the twentieth century had as diffuse ownership as the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. Nonetheless, the trend was there. Of the 200 companies Berle and Means studied, only 56% had individual ownership of 20% or more of the stock, which was used as a minimum threshold necessary for control of the company. In only 11% of the companies the largest shareholder held majority shares. Nearly half of US large companies were controlled by their managers, not their shareholders (Berle & Means, Citation1968; Mizruchi, Citation2004).

Berle and Means devote a large section of their work (Berle & Means, Citation1968, pp. 196–254) to an analysis of the legal position of managers, the legal powers of corporations, and the resultant position of stockholders. They do not distinguish between board members and other senior managers like others. This is in part because ‘control lies in the hands of the individual or group who have the actual power to select the board of directors (or its majority)’ (Berle & Means, Citation1968, p. 66). Furthermore, control of a corporation even may be dictated by an outside agency, a bank, for instance, as a condition for a loan. In this regard, Corey (Citation1930) notes that J. P. Morgan wielded his considerable power over other companies by means of a complex interplay of … stock ownership, voting trusts, financial pressure, interlocking of financial institutions and industrial corporations by means of interlocking directorates, and the community of control of minority interests (p. 284). Thus, control of a company may be exercised by means other than board membership or stock holdings.

To highlight power asymmetry, Berle and Means (Citation1968) argue that power has been concentrated in distinct bodies throughout history. In early medieval Europe, for example, it was concentrated in the Church; later, it became concentrated in the state, especially after the reformation. Today, it is becoming, or has become, concentrated in corporations. Berle and Means (Citation1968) conclude their work as follow:

The rise of the modern corporation has brought a concentration of economic power which can compete on equal terms with the modern state, economic power versus political power, each strong in its own field. The state seeks in some respects to regulate the corporation, while the corporation, steadily becoming more powerful, makes every effort to avoid such regulation. Where its own interests are concerned, it even attempts to dominate the state…. The law of corporations, accordingly, might well be considered as a potential constitutional law for the new economic state, while business practice is increasingly assuming the aspect of economic statesmanship (p. 313).

Mr. Coleman, the author, speaking of the fight, says, “My fight is still going on, and I tryst it will continue till the insolence of these railroad corporations is curbed … [ellipsis added]” One wonders if throughout the thirty-five years since the article was written Mr. Coleman has continued to fight the good fight and is to-day a veteran of the ranks; or did he long ago become discouraged at the difficulty of teaching the railroads that lesson and give it all up? Or, for in thirty-five years much may happen, did he die amid the battle, still fighting? (Citation1907, p. 682)

The influence of Berle and Means (Citation1968) has been immense. However, interest in it mostly centred around social scientists, scientists who tended to accept its broad conclusions (Mizruchi, Citation2004). Most social scientists, including those with Marxist views, accepted the work uncritically. Indeed, a major criticism of the work, when such occurred, was that it was Marxist, an interpretation that failed to see the work’s main point (Wormser, Citation1933). By and large, economists tended to view it as an irrelevance (Mizruchi, Citation2004). The neo-classical economists tended to see the market as self-correcting, so it did not matter who (or what) controlled large corporations: the market would ensure optimal efficiency regardless. In the long run, market competition forces corporations to minimise costs and, in doing so, to ensure credible corporate governance necessary for attracting outside funds (e.g. Alchian, Citation1950; Stigler, Citation1958). Such neo-classicist views ignored the growth in number of duopolies and oligopolies as Berle and Means mentioned: neo-classicist economics works only if there exists perfect competition, or something close to it which requires large numbers of buyers and suppliers.

There are number of flaws in Berle and Means (Citation1968) analysis. They used only US data. There was no guarantee that non-US corporations behaved, or would come to behave, in the same manner as US corporations, even if the non-US corporations operated in sophisticated economies. Furthermore, the period of US history studied by Berle and Means was unusual. It marked, on the one hand, the relative decline in power of the Robber Barons and, on the other, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the factors that led up to it. It also marked the period leading up to, during, and after World War I (WWI). US government spending (and debt) exploded during WWI, but, under the Harding and Coolidge administrations contracted—a contraction that possibly led to the post-war US boom of the 1920s (Folsom, Citation2008). Thus, even if Berle and Means’s analysis of the US corporations in the first three decades of the twentieth century was entirely sound, it would remain a moot point whether they behave in the same ways today, and it would equally be a moot point whether corporations outside the USA behave in a similar manner. By the late 1990s, advanced economies other than USA have considered this as a serious issue which gradually affects developing countries as well (Yusof, Citation2016). For apparent reasons, empirical research provided only limited support for Berle and Means (Citation1968). On the crucial issue of whether diffused ownership leads to the mulcting of investors, Monsen et al. (Citation1968), for instance, found only a minor tendency for companies with high levels of owner management to be more profitable than those with low levels of owner management and similar results were obtained by Palmer (Citation1973) and, to a lesser extent, by Larner (Citation1970). Kamerschen (Citation1968) also found no such differences.

It appeared that corporations hired and fired managers in ways not easily explained by Berle and Means (Citation1968). In a study of the sacking of chief executives in the US’s 500 largest companies, James and Soref (Citation1981) found no relationship between ownership power and executive sackings. This was odd in that, if managers were usurping power, one would expect that owners had little power over managers to be unable to sack them. Instead, the study found, company profit was the main determinant: when profits were high, managers tended to stay; but when they were low, managers tended to be fired. Such findings are relatively recent. They were made more than three decades after publication of The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and in that period the USA had changed. A notable US development was her series of antitrust laws—the Sherman Act (1890), the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914), the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914), the Robinson-Patman Act (1936), the Celler-Kefauver Act (1950). These laws were made to prevent the creation of monopolies. Regardless of whether such laws were necessary (monopolies, if they exist, do not appear to last long, e.g. Tullock, Citation1997), the laws had bite. In 1911, for example, the Sherman Act was used to break up John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil into smaller, and geographically diverse, companies (Standard Oil Company of New Jersey v. United States, 1911). Subsequent Supreme Court rulings further limited corporate autonomy. United States v. Trenton Potteries Co. (1927) determined that price fixing is illegal per se, for instance, and, controversially, Hartford Fire Insurance Co. v. California (1993) determined that non-US companies operating outside the USA could be held liable if they contravened the Sherman Act. Ironically, The Modern Corporation and Private Property had a major influence on antitrust legislation and its enforcement (Orbach & Campbell Rebling, Citation2012).

In the meantime, the USA introduced tougher laws to control unethical business practice. The Securities Exchange Act (1934), for example, prohibits short-term profits made by individuals (e.g. company directors) who own more than 10% of a company’s shares and the same act prohibits fraudulent trading in securities. The act was strengthened by the Insider Trading Sanctions Act (1984) and the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act (1988). These laws allow for penalties for insider trading being up to three times any profit made from the insider trading. The prohibitions of these acts were mirrored in Supreme Court rulings. Dirks v. SEC (1984), for example, deemed that tippees (those who receive second-hand information) are liable if they suspected that the sources of the information had insider knowledge and United States v. O’Hagan (1997) established that a company’s inside knowledge is corporate property; therefore, inappropriate use of that knowledge for personal gain (e.g. by company employees) is tantamount to stealing company property, that is, to embezzlement.

Accounting standards within the USA also became tougher. The standards date from 1887, which saw the formation of the American Association of Public Accountants, succeeded in 1916 by the Institute of Public Accountants, with a name change in 1917 to the American Institute of Accountants and a further name change, in 1957, to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants [AICPA], Citation2020). Meantime, 1921 saw the formation of the American Society of Certified Public Accountants, which was merged into the AICPA in 1936, at which time the Institute restricted membership to certified public accountants (AICPA, Citation2020). The AICPA was buttressed in 1984 by the formation of the Governmental Accounting Standards Board [GASB] (2013). Today in the USA, such bodies promote the use of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Although GASB recommendations are not enforced under US Federal Law, they are enforced under certain state laws (GASB, Citation2013); moreover, GAAP fall under the purview of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which was set up in 1934, largely because of the Wall Street Crash of 1929, and whose head is appointed by the US President (Securities Exchange Commission [SEC], Citation2013). The SEC does not set standards; rather, it accepts acts on independent advice (e.g. from GASB). However, the Securities Act (1933) requires that investors receive all significant (including financial) information concerning securities offered for public sale. The same act prohibits deceit, misrepresentation, and similar fraud in the sale of securities (SEC, Citation2013). To this, one may add that the SEC has been responsible for certain US laws (SEC, Citation2013). Examples include the Trust Indenture Act (1939), the Investment Company Act (1940), the Investment Advisers Act (1940), and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002), this last being set up in response to the Enron scandal (SEC, Citation2013). Following the Enron scandal, for example, Andrew Fastow (Chief Financial Officer—CFO) of the company, following plea bargaining to drop other charges, was convicted of two charges of conspiracy and sentenced to 10 years in jail; Jeffrey Skilling (Chief Executive Officer—CEO) was found guilty of securities and wire fraud and sentenced to 24 years and four months; Kenneth Lay (Chairman and former CEO) was similarly found guilty of securities and wire fraud and faced a sentence of 45 years, but died before sentencing. All told, 17 Enron employees and 6 Merrill Lynch employees (who were deemed complicit in the fraud) were found guilty (McLean & Elkind, Citation2004). In addition, the company’s accountancy firm, Arthur Andersen, was found guilty of obstruction of justice (for shredding documents) (McLean & Elkind, Citation2004), and though the ruling was later overturned (Arthur Andersen LLP v. United States, 2005) by the Supreme Court because of trial irregularities, its reputation was so damaged that the firm was, in effect, put out of business.

The Enron case illustrates another change in the USA since the time of Berle and Means (Citation1968): attitudes had changed, and so had corporate scrutiny, both by public and by private bodies. The Enron scandal was presaged by a suspicious article concerning its stock price in Fortune Magazine (McLean, Citation2001), an article that, in effect, killed the firm (McLean & Elkind, Citation2004), and public opinion, coupled with bad publicity, appears to have killed Arthur Andersen. This contrasts with, for example, the Robber Baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose business strategy, as Galbraith (Citation1967) observes, involved stealing from the public (“The public be damned,” he famously said, p. 49), but whose reputation remained intact.

The change in US attitudes to big business was long in the making. This is illustrated by the Johnstown flood disaster of 1889, which was caused by negligent maintenance of a nearby dam. Over 2000 residents of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, died as a result, and the town was, in effect, destroyed (Johnstown Flood Museum, Citation2013). Significantly, the owners of the dam, who included the Robber Barons Frick and Carnegie, were not held legally liable for the disaster (however, both Frick and Carnegie contributed many thousands of dollars to the relief effort, Carnegie committing himself to rebuild the town). The public outrage following the flood was so significant that the US later adopted the UK law, established by Rylands v Fletcher (1868), that held owners of land liable for injuries caused by mismanagement. It is unlikely that the likes of Frick, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt would have survived the glare of scrutiny, public and private, to which companies today are exposed. In the late 1970s, for instance, newspaper articles alleged that residents of Love Canal, Niagara Falls, New York, were harmed by 21,000 tons of toxic waste dumped underground by the Hooker Chemical Company (now Occidental Petroleum Corporation). So great were the concerns over Love Canal that, in 1978, the then US President Jimmy Carter declared Love Canal a state of emergency, and 800 Love Canal residents were relocated to “safe” areas (Wildavsky, Citation1995). The USA’s Environmental Protection Agency then sued the Occidental Petroleum Corporation in 1996 for restitution, and the company settled, out of court, for US$129 million (US Department of Justice, Citation1995). There is no evidence, incidentally, that the toxic waste harmed any Love Canal residents, nor that it constituted a substantial hazard to human health; moreover, if anyone was to “blame” for the alleged disaster, it was the Niagara Falls City School District, who ordered, contrary to the advice of the Hooker Chemical Company, that a school be built over the site of the dumping (Wildavsky, Citation1995).

This does not demonstrate that companies and company executives no longer behave unethically. The Enron and Lehman Brothers scandal, among many other recent cases, suggest that they sometimes do. It demonstrates that companies and company executives are subject to pressures and scrutiny that would have been unthinkable in the early 1900s, the era that most concerned Berle and Means (Citation1968). This illustrates another change. Corporate responsibility today is very different from what it was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Rightly or wrongly, corporations are forced to provide safe working conditions, are punished by customers if they do not pursue ethical (e.g. environmentally sound) policies, are forced to provide safe products and services, and are encouraged to ensure that all stakeholders receive a fair deal (Chouaibi & Affes, Citation2021). By contrast, for nineteenth century corporations, the only major concern was profit. An upshot of this is that determining what constitutes sensible investment and what constitutes empire building may be becoming increasingly unclear. If, for example, a company’s CEO deems that the company should devote, say, 25% of its advertising budget to its environmental rectitude, one may ask whether the CEO’s policy is aimed to improve the company’s performance or to enhance the CEO’s personal reputation.

There have been other changes since Berle and Means’s work - the growth in power and reliance on technology, the increasing power of media, the increase in government spending in the western world, the corresponding increased power of governmental and quasi-governmental organisations, the growth of multinational corporations, and the associated rise of globalisation. In addition, Berle and Means (Citation1968) do not discuss how government employees mulct taxpayers; neither do they discuss how such employees build empire. In other words, agency problems do not pertain only to private corporations; they also pertain to government which was unaddressed by Berle and Means. Wildavsky (Citation1995), for example, argues the 1972 US ban on the use of the pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was not motivated by the supposed dangers of DDT to wildlife and humans (at the time of the ban, it appeared safe in both respects, and it continues to appear so, see, e.g. Edwards, Citation2004, Lomborg, Citation2001; Wildavsky, Citation1995, moreover, the ban appears to have cost the lives of 10s of millions of black people, see, e.g. Edwards, Citation2004). Instead, it appears to have been motivated by a desire by the USA’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to increase its power and funding (Wildavsky, Citation1995). The state of corporate governance in emerging economies mostly resemble those conducted in developed countries, particularly in the UK and USA. In a study, the author (Yusof, Citation2016) argues that corporate governance research in emerging economies is different due to different institutional, political and other contexts and such study should utilize different theoretical perspectives. This study also supports this thesis.

4.2 Agency theory, corruption and governance

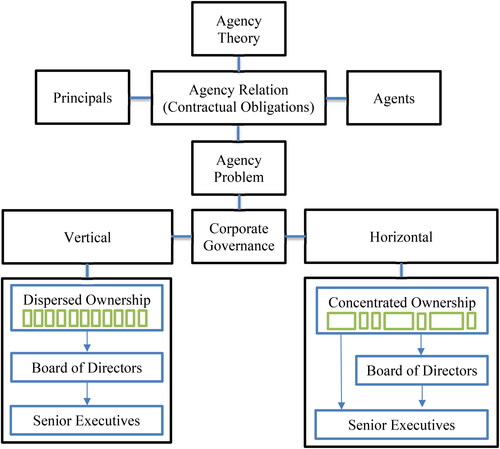

Agency theory () reduces the problems that surface in the firms due to the separation of owners and managers (Panda & Leepsa, Citation2017). The theory begins with the agency problem which derives from contracting someone else to do one’s own work. The theory relies on three dubious assumptions, namely, (a) People are rational; (b) People are motivated by self-interest; and (c) Self-interest involves maximising financial reward. People are not always rational, and people do not work only for money every time, for instance. Indeed, need theory of motivation claims that people are motivated in a hierarchy when they work, not so much for money, but for self-actualisation (Maslow, Citation1968). This caveat suggests that the assumptions behind agency theory are a simplification. Nonetheless, although plausibly resting only on simplifications, agency theory may provide insight into corporate behaviour leading to the following considerations:

For complex working relationships, a principal (e.g. a business owner) must determine the work that needs to be done, and an agent must perform it. This is because either the principal is unable to perform the work, or the principal is unwilling to perform it.

This may lead to a conflict of interest between principal and agent. The source of the conflict is twofold, namely:

Principals want agents to work for as little as possible, but agents want the principal to pay as much as possible, ideally, they will cheat the principals.

Agents and principals will have different views on risk-taking. At times, agents may be more willing to take risks. At others, they will be less willing. The agency theory covers the agency conflict arising from the opposite risk-preferences between the principal and agent (Panda & Leepsa, Citation2017). Mathew et al. (Citation2020) explored the relationship between board governance structure and firm risk. The study confirms a negative relationship between governance and firm risk.

Imagine a corporation that is owned by shareholders (the principals), not one of whom works for the corporation and not one of whom owns more than, say, 10% of the shares. In such a situation, the everyday running of the company will be managed by its senior executives (Chair, CEO, Company Secretary, etc.), the agents. These executives will be tempted to cheat the shareholders by paying themselves more than is necessary, for example. If so, the shareholders will earn less than they would if they had more ethical senior executives working for them. Therefore, it is in the shareholders’ interests to instigate checks on their executives’ powers. An important principle pertaining to moral hazard becomes operative here. Moral hazard, in economics, refers to any situation in which one party in a contract, because of his or her privileged information, may behave in ways disadvantageous to the other party in the contract. For example, say, one party take risks, but the other party bears the costs if things go wrong (e.g. Krugman, Citation2009). Moral hazard is a ubiquitous problem. In insurance, for instance, an individual may take out an insurance policy when he or she know that he or she is a riskier client than the insurance company knows. A jockey, for instance, may take out insurance against broken bones but not tell the insurer that he or she is a jockey (jockeys have high risk of broken bones). In such a situation, the client pays less insurance than would otherwise be demanded. However, corporations are too big to fail. Thus bankers, for instance, may issue risky loans because the bankers know that, if they lose billions of dollars, the government will not risk the financial disaster that would result failure of their bank. Here, ultimately, taxpayers would pay the cost, but bankers would take the risk, and so derive benefits. Indeed, of the 100 or so banking crises in the immediate decades prior to 2000, all were bailed out at taxpayers’ expense (Boyd et al., Citation2000). Related to this was the recent subprime housing crisis in the United States of America. The crisis emerged because of competition between mortgage suppliers, who, in effect, got paid for supplying loans to high-risk clients (see, e.g. Whalen, Citation2008). When large number of the clients failed to meet payments, the losers were the clients, whose property was by then worth less than they had paid for it; the mortgage companies and banks’ investors; and the taxpayers, who paid for the bank bailouts. The winners were the bank employees who granted the loans, at no risk to themselves. In this regard, Simkovic (Citation2013) observes that competitive mortgage secularisation has been tried three times in US history—the 1880s, the 1920s, and the 2000s—and each time it has been a disaster.

Some problems revolving round agency theory and moral hazard are problematic. An example concerns the US aerospace company, Lockheed scandal of the 1970s. The scandal first emerged when Lockheed’s then Vice-President, Carl Kotchian, publicly admitted to the company’s activities in Japan (Mabrey, Citation2007). Lockheed had paid roughly US$22 million in bribes to secure large sales in the country. The bribes included over US$1 million to the then Japanese Prime Minister, Kakuei Tanaka, and over US$2 million to Yoshio Kodama, a known gangster, who warded off Lockheed’s major rivals, Boeing and McDonnell Douglas. Following the scandal, the USA passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (1977), which forbids US companies from bribing foreign officials to secure contracts (Badua, Citation2015). Several things are of note in this scandal. First, although the US Congress, in passing the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, clearly viewed the company’s activities as unethical, others did not. Kotchian argued that he was forced to bribe the Japanese, for, had he not, Lockheed would have lost business and thousands of Lockheed employees would have lost their jobs. Second, at the time of the bribery, Lockheed did nothing illegal under then US law (e.g. Drucker, Citation1981). Why then, should a company be punished despite acting legally? The agency and moral hazard problems appeared to involve only the then Japanese government, who were stealing from Japanese taxpayers, both by accepting bribes and by, possibly, not buying possibly superior aircraft from Lockheed’s rivals. Agency problems may thus arise when there is more than one agent and more than one principal, and, in such instances, not all agents need to be guilty. There was also a political aspect to the affair. Henry Kissinger, then US Secretary of State, allegedly tried to prevent knowledge of the scandal being made public - this on the grounds that such disclosure would damage the USA’s relations with her allies (Mabrey, Citation2007). Regardless of whether one agrees with Kissinger’s alleged actions, there is a general point. To what extent should one permit a minor transgression for the sake of a greater good, or, conversely, to what extent should one punish a minor transgression at the cost of the greater good?

Many economists highlighted this moral quandary in their writings. Ladd and The (Citation1970), for instance, argues that businesses have no ethical obligations; businesses are defined by specific goals, and specific goals carry no ethical implications. Friedman (Citation1970) broadly concurs: the social responsibility of businesses lies only to their shareholders. In such views, only people have ethical duties, and businesses are not people. Drucker (Citation1981) takes a slightly different angle from Ladd and Friedman. There is one rule for private citizens, another for businesses. If you are attacked by a mugger and therefore pay the mugger not to harm you, nobody would blame you, they’d blame only the mugger. In the Lockheed scandal, the innocent victim was Lockheed and the mugger the Japanese government, most notably her Prime Minister (Drucker, Citation1981). Against such considerations, Martin and Schinzinger (Citation2004) point to ethical problems faced by junior employees, especially, as in the case of Lockheed, engineers. If such employees discover what they perceive as unethical behaviour on the part of their company employer, where does their duty lie, to their company or to the world in general?

Drucker (Citation1981), again, raises an important issue regarding whistleblowing. As of 2013, the whistle-blowers are generally protected by law in the United Kingdom (UK) if their disclosures are made in the public interest (UK Government, Citation2013). However, as Drucker argues, whistleblowing can easily turn into informing, and governance and polity based on informing has a poor ethical record. He cites few examples including the governance of Mao Zedong, the Spanish Inquisition, and the terror campaigns of Rome’s Emperor Nero. By implication, a culture in which whistleblowing is endemic, although promoting short-term ethical gains, may lead to what would be a Stalinist state; also, it is open to abuse. Such considerations do neither suggest that all bribing of foreign officials is good, nor all whistleblowing is bad. They do suggest, however, that determining what is ethical and what is unethical in economic and political behaviour is often difficult.

4.3. Empirical studies—critical analysis

4.3.1. Diffusion of ownership

Some studies on diffusion of ownership have reached broader conclusions in line with those of Berle and Means (Citation1968) (e.g. Baumol, Citation1959; Grossman & Hart, Citation1986; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). However, recent studies suggest that ownership is less diffused than Berle and Means suggest; indeed, today concentration of ownership, even in the USA, is often substantial (La Porta et al., Citation1999). Holderness and Sheehan (Citation1988), for instance, determined that there are hundreds of publicly traded US corporations with majority shareholders. Thus, the existence of large shareholders in USA is not an exception, rather it becomes the norm. Morck et al. (Citation1988) also confirmed that there is at least some concentration of ownership in the largest US firms. This suggests that the level of US management ownership has risen since Berle and Means (Citation1968) investigation (see e.g. Demsetz, Citation1983; Holderness et al., Citation1999; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986).

In addition, La Porta et al. (Citation1999) report that high level of concentration of ownership is prevalent in other countries, most notably Germany, Japan, Italy, seven Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and in developing economies. Indeed, concentration of ownership may be especially high in East Asian corporations. Claessens et al. (Citation2000) studied 2980 listed corporations in 9 countries (Hong Kong, South Korea, Malaysia, Japan, Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Taiwan). Results suggested that a single shareholder controlled more than two-thirds of the corporations. The study also detected national differences. In Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and Taiwan, at least four-fifths of companies had managers who belonged to the controlling owner. By contrast, in Japan and the Philippines, less than half the managers so belonged. The study leaves open the question of whether corporations in corrupt countries retain family ownership and control to limit the effects of corruption. Claessens et al. note, for instance, as regards the difference in concentration of ownership between Japan and Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and Taiwan, that Japan had a tradition of professional management before the Meiji restoration (1868), which marked the start of Japan’s industrialisation (Yamamura, Citation1977).

There are two plausible explanations for the difference in conclusions regarding concentration of ownership between those of Berle and Means (Citation1968) and those of more recent researchers. First, as indicated, the early decades of the twentieth century were unusual, and, in any event, Berle and Means studied only US companies; second, Berle and Means might have been so influential, at least in the West, that company owners reacted to their new-found emasculation by ensuring they didn’t lose corporate control. In emerging countries, corporate governance becomes important due to potential change in their domestic economies which results market based economic reform initiatives during 1980s and 1990s (Yusof, Citation2016). The Asian crisis coupled with few others in emerging countries highlight weaknesses in governance system and become a concern for national and international levels (Singh, Citation2003).

4.3.2. Remedies of agency problem

4.3.2.1. Concentrated ownership

There has been an overall increase in concentrated ownership structures and controlling shareholders become the norm for most of the world’s companies (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2019). Especially in Asia, concentrated ownership becomes a central feature due to the rise of emerging market economies (Lim, Citation2021; Tran & Le, Citation2020). A powerful owner or the block-holders or concentrated ownership can improvise the value of the firm through closely monitoring the behaviors of the managers (Burkart et al., Citation1997). Research suggests that, today, owners are active in limiting the rapacity of their managers (e.g. Kang & Shivdasani, Citation1995). While concluding a study on corporate governance, Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) favoured concentrated ownership, and this conclusion accords with the results of the studies reviewed above. The high concentration of company ownership may influence the agency conflicts between majority shareholders and minority shareholders (Wulandari & Setiawan, Citation2021). In most Asian countries (other than Japan), ownership concentration is prevalent. Such concentration is more likely in small firms than large firms. As shown in , there are few countries where ownership concentration exceeds 60% in large firms as well. Very interestingly, one sixth of total market capitalization in Philippines and Indonesia left under the control of a single family, the Suhartos and the Ayalas (See Claessens et al., 1998b).

Table 1. Ownership concentration of the ten largest firms.

The presence of large investors should serve as a check on rapacious managers (Berle & Means, Citation1968). Gedajlovic and Shapiro (Citation2002) found that the presence of concentrated ownership is associated with greater productivity in Japan. However, in Nigeria, Dockery et al. (Citation2012) found that large investors conspire to cheat small ones, and that this has a negative effect on productivity. This accords with the suggestion of Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997). It is plausible that Nigerian experience holds true of other highly corrupt countries. In this regard, Dockery et al. found that foreign direct investment in Nigerian companies serves as a break on corporate corruption and an impetus to productivity. This result supports the view of Moyo (Citation2010), who argues that the poor countries in Africa require, not aid, but, among other things, foreign direct investment. The Satyam fraud in 2009 proves the demonstration of human greed, ambition, and hunger on part of the founders for power and money. This case is different than Enron and operationalize the tunnelling effect in an Asian context (Bhasin, Citation2013).

4.3.2.2. Voting shares

Another method might involve favouring voting shares over non-voting shares (Arslan & Alqatan, Citation2020). Zingales (Citation1994) studied 64 companies listed on the Milan Stock Exchange (MSE). The key variable was ownership type. Ownership of each company comprised voting and non-voting shares. Data came from the years 1987–1990. Results showed that voting shares traded at prices 82% above those of non-voting shares. This was odd given that the non-voting stock provided 1.4 times the yield of voting shares. Thus, investors were willing to pay almost double for control of the companies, but at the additional cost of lower return. This contrasts with the findings of other research, which, Zingales reports, suggests that voting stock normally trades at prices only 10–20% higher than non-voting stock. Zingales attributes this to “the very large value of control in Italy” and the “different levels of protection of minority property rights in that country” (Citation1994, p. 147). In other words, investors in Italian companies want control of the companies they invest in more than do investors in non-Italian companies, and this is because Italy is corrupt. Italy appears second only to Greece as the most corrupt country in Western Europe (Italy 2012 CPI: 4.2; Greece 2012 CPI: 3.6). Levels of corruption in Italy appear to have risen since Zingales’s study, but they appear to have always been high (in 2001, the earliest year for which data are available, Italy’s CPI was 5.5).

The study of Zingales (Citation1994) reports three other things. First, the mean market capitalisation of the companies with the two types of shares listed in the MSE was US$931 million, but that of those with only non-voting shares was only US$661 million. Thus, the companies in which executive power was curtailed by shareholders were worth about 50% more than those in which executive power was not so curtailed. This suggests the possibility that control over executive rapacity works. The companies with a mean market capitalisation of US$931 million were worth so much because, in them, executive power was curtailed. Second, voting shares were not only more expensive than non-voting shares; they were also more popular, with an average take-up of 74% of total shares. This suggests the possibility that, to curtail executive rapacity, voting shares must comprise a large proportion of total stock. Third, Italian experience is different from US experience. In the USA, voting stock is most concentrated in small companies. In Italy, it is not. Companies included in the study included Olivetti, Montedison, and Fiat—that is, many of Italy’s largest companies. This result may be explained by the USA’s being much less corrupt than Italy (USA CPI 2012: 7.3). It might be that the relative lack of corruption in the USA abnegates the need for shareholder control over the executives of large companies. Here also notice the possibility of large national differences in corporate behaviour. Of course, generalising from Zingales’s (Citation1994) study is problematic as he studied only Italian companies listed on the MSE. He admits that the ownership of large companies in Italy is different from elsewhere. Referring to agency theory, his results suggest that senior executives try to defraud stakeholders, and, in turn, stakeholders can take measures to curtail the rapacity of senior executives.

4.3.2.3. Lobbying

Zingales (Citation1994) suggests another method to protect owners from executives. They may lobby or force politicians to make new laws or to enforce old ones. Thereby, they may make it illegal or impracticable for executives to steal from them. Lack of law or its enforcement may make things difficult for owners. Various studies (Barca & Trento, Citation1997; Pagano et al., Citation1998; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997) report that Italian corporate governance is so undeveloped that it substantially retards the flow of external capital to firms, that is, Italy lacks the corporate mechanisms to easily obtain capital. The situation appears even worse in Russia. In Russia, not only are external sources of capital virtually absent, but managers also regularly divert assets (i.e. steal) from firms due to the weakness of corporate governance mechanisms (Boycko et al., Citation1995). Russia has a 2012 CPI of 2.8., which places it as being more corrupt than such notoriously corrupt countries as Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Guyana, Iran, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Nicaragua, and Uganda. In this regard, Black et al. (Citation2000) argue that the reason Russia failed to rapidly develop a vibrant expanding economy was that Russia lacked the corporate and legal infrastructure to do so. The country further suffered from punitive taxation, bureaucracy, organised crime, and endemic corruption. At present, Russia has a real GDP growth rate of 3.4%, almost all of this is due to oil and gas production upon which Russia heavily relies. Russia was also hit particularly hard by the global economic crisis of 2007–2008 (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], Citation2012).

Poor governance may affect otherwise healthy and honest economies (Alina & Till, Citation2019). Japan, for example, appears among the least corrupt countries on Earth. She has a CPI score of 7.4, which places her as broadly the same as the USA and the UK. In addition, she owns a democracy and has good rule of law. In its 2010 assessment, the Polity IV project gave Japan a score of 10 for Democracy (the maximum), 10 for Polity (again, the maximum) and 0 for Autocracy (the minimum). However, these are overall standards, and they ignore differences within Japan’s economy. Hanazaki and Horiuchi (Citation2003) observe that Japanese banks lack transparency; in particular, the financial arrangements as regards non-performing loans are opaque to outsiders. Hanazaki and Horiuchi further observe that there are no trustworthy penalties for poor management within Japanese banks. Moreover, the poor governance of Japan’s banks plausibly contributed to the country’s bubble economy during the period 1986–1991 and her economic difficulties thereafter (see, e.g. Krugman et al., Citation1998).

Japan is not alone in having poor governance in her financial sector. Transparency International (Citation2012a, Citation2012b) reports that corruption is highest in those in the financial sector. Opaqueness coupled with poor governance is a plausible causal factor in the recent US sub-prime housing crisis (see, e.g. Schwarcz, Citation2008). Finally, although Japan appears honest and has good polity, corruption appears in the country not only in the financial sector. Iga and Auerbach (Citation1977) observe that the Japanese are remarkably tolerant of corruption in their politicians. Following the Lockheed scandal of the mid-1970s, for instance, Japan President Kakuei Tanaka was found guilty of receiving bribes; yet he was allowed to keep most of his ill-gotten gains and did not serve a prison sentence. Moreover, he successfully ran for re-election in 1976. Berglöf and Claessens (Citation2004) argue that, although much remains unknown as regards corporate governance in other countries, it appears that enforcement is as important as laws and regulations, at least in developing countries. Here Dockery et al.’s (Citation2012; and see Moyo, Citation2010) finding that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) helps limit corruption in poor countries is relevant. Moreover, they argue, although legislation may be necessary to control corruption, it may not be sufficient. Particularly in developing economies, effective control may be generated bottom up, with stock exchanges, shareholders, and other parties forcing companies to behave honestly. Italy’s experience with stockholders insisting on voting rights over the control of her largest companies accords with this conclusion.

4.3.2.4. Board composition

Much research has focussed on board composition. Such research has concentrated on such issues as CEO duality, the proportion of non-executive directors on the board, and size of board. However, the research has produced mixed, sometimes even contradictory results. Belkhir (Citation2009) found board size, insider ownership, large shareholders, proportion of outside directors, and board leadership structure as acting synergistically to promote good governance. For a sample of banks listed in 11 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, Issa et al. (Citation2021) show that there is a significant relationship between board diversity and financial performance in banks. Fernández-Temprano and Tejerina-Gaite (Citation2020) also investigate the effect of board diversity on firm performance. Few studies (Calabrese & Manello, Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2019) demonstrate a positive effect of women in board representation on firm performance. Vairavan and Zhang (Citation2020) find neither direct nor indirect effect of board racial diversity on firm performance. However, O’Connor et al. (Citation2006) found that sometimes CEO stock options facilitate fraud, but sometimes they discourage it. Similarly, some studies (e.g. Pathan, Citation2009), identify strong boards as a check on CEO power, particularly as regards risk-taking. Kosnik (Citation1987) has argued that outside directors inhibit greenmail, the repurchase of corporate stock at inflated prices. Hence, Kosnik argues that outside directors are good. However, some results are paradoxical. Cochran et al. (Citation1985), for instance, found that a high proportion of outside directors was associated with higher than usual golden handshakes. The inclusion of more outside and independent directors in the board (Rosenstein & Wyatt, Citation1990; Tran, Citation2021) help in making the alignment of the interest among the owners and managers by diligently watching the actions of the managers. Also, despite the feeling that directors are overpaid, Mace (Citation1977) reports of the Hanes Corporation, whose then CEO and president, Robert Elberson, checked on the workload of his outside directors. To his astonishment, he found that they were hard-working, conscientious, and grossly underpaid.

Again, some studies have found national differences. Aggarwal et al. (Citation2007), for example, found that US firms were better governed than non-US firms in general. The same study found that CEO duality does not affect performance. Meantime, as Rhoades et al. (Citation2000) observe from results of a meta-analysis of the influence of outside directors, many conflicting results in the extant research may simply reflect the different methodologies of different researchers. Some authorities argue that such research is relatively pointless. Dalton et al. (Citation1998), in a meta-analysis of 54 studies of board composition and 31 studies of board leadership structure, found no consistent relationship between company performance and board composition, nor of one between corporate performance and leadership structure. Thus, Dalton et al. conclude, “we are not optimistic that further research in the general areas of board composition/financial performance and board leadership structure/financial performance would be fruitful” (p. 284). However, they add:

We would not, however, suggest that boards of directors do not have an impact on firms’ financial performance. A potentially promising avenue for future research may be the relatively coarse-grained nature of board composition itself…. accounting exclusively for the impact of the full board on firm outcomes may fail to appropriately capture the subtleties of these relationships. (p. 284)

They [board members] sit in a corporation’s inner sanctum. They settle into high-backed chairs around burnished mahogany conference tables. And what they say and do is often an enigma to anyone outside those closed doors. They are the directors in the boardroom, a collection of names, egos, and experience that serves as the critical link between a public company’s owners, its shareholders, and management.

That, at least, is the theory. In practice, too many boards have been mere “ornaments on a corporate Christmas tree,” as a landmark study of boards by Harvard business school professor Myles Mace once put it—decorative and decorous baubles, with no real purpose. Little more than a claque of the CEO’s cronies, they would quietly nod and smile at their buddy’s flip charts and rubber-stamp his agenda for the corporation (Paras 1–2).

Evaluate performance of CEO annually in meetings of independent directors

Link the CEO’s pay to specific performance goals

Review and approve long-range strategy and one-year operating plans

Have a governance committee that regularly assesses the performance of the board and individual directors

Pay retainer fees to directors in company stock

Require each director to own a significant amount of company stock

Have no more than two or three inside directors

Require directors to retire at 70 years of age

Place the entire board up for election every year

Place limits on the number of other boards on which its directors can serve

Ensure that the audit, compensation, and nominating committees are composed entirely of independent directors

Ban directors who directly or indirectly draw consulting, legal, or other fees from the company

Ban interlocking directorships: “I’m on your board, you’re on mine” (para. 1)

Such good boards are predominantly proactive. They monitor performance, they set clear targets, they forbid directors to have conflicting interests, and they fire incompetent directors. Moreover, as Byrne and Melcher (Citation1996a) illustrate, they actively train staff with new skills and promote staff on merit; indeed, such policies formed a major part of the revival of Campbell Soup. Bad boards, by contrast, do virtually nothing. Eventually, shareholders oust them if they can. Byrne and Melcher (Citation1996a, 1996b) arguments accord largely with those of Myles Mace whom they acknowledge. Mace (Citation1965) specifically recommended that company presidents, and boards, should show firm leadership. Any president should display:

Leadership in the tough and laborious process of realistically evaluating existing product lines, markets, trends, and competitive positions in the future.

Leadership in the establishment of corporate objectives. (p. 50)

Similarly, Mace (Citation1977) argues that a board’s responsibilities include ensuring accuracy and honesty in its auditors. In the ordinary course of events, auditors may not detect internal fraud, and may not even see it as their responsibility to do so. Companies with a higher concentration of ownership are less likely to demand extensive auditing. However, the ownership concentration plays a minor role in the positive association between internal corporate governance and audit quality (AlQadasi & Abidin, Citation2018). Guizani and Abdalkrim (Citation2021) reports that companies are more likely to engage high-quality auditors and pay larger audit fees if they have higher active and passive institutional ownership. In a study on the asymmetric impact of institutional ownership on firm performance, Daryaei and Fattahi (Citation2020) report that performance increases with institutional ownership. Mace (Citation1972) also observes that a retiring CEO often stays in power to the detriment of the company and the new CEO. Mace (Citation1972) recommends that outside directors should have a stake in the company and should be used to scrutinise corporate policy. Mace’s suggestions also accord broadly with agency theory. Fama (Citation1980) and Fama and Jensen (Citation1983), for instance, argue that owners must monitor managers if the owners are to avoid being mulcted.

4.3.2.5. Executive pay

The evidence on executive pay is mixed. Coughlan and Schmidt (Citation1985) found a positive correlation between executive pay and corporate performance like Murphy (Citation1985) and Benston (Citation1985). Expropriation by managers deepened the financial troubles of the Bangkok Bank of Commerce which becomes a well-documented example in this area (Johnson et al., Citation2000). The owners can maximize their wealth by motivating managers to work harder for the better performance through a periodic compensation revision and proper incentive package (Core et al., Citation1999). Such results led Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) to conclude that one can reject an extreme interpretation of Berle and Means (Citation1968), namely that owners are impotent in the face of rapacious managers. However, other evidence suggests the converse. In studies of US, Japanese, and German corporations, Kaplan (Citation1994a, Citation1994b) found that executive sensitivity to pay and dismissal was broadly the same in all three countries, yet the US executives were paid more than their Japanese and German counterparts, a finding that suggests that US executives milk their employers more than they deserve. Against this, Jensen and Murphy (Citation1990) found that CEO pay, in the USA at least, changes (up or down) by US$3.25 per US$1000 change in share value. Jensen and Murphy note here that, although CEO stock ownership provides a powerful incentive relative to salary, most CEOs hold trivial amounts of stock and, in any event, the amount of stock they hold fell in the period 1940–1990. This last observation is consistent with Berle and Means (Citation1968) analysis. Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) also argue that high executive pay may negate risk sensitivity among executives while high pay would also provide opportunity for embezzlement. Shleifer and Vishny (Citation1997) further point out that there is little agreement on whether large corporations are managed in a broadly honest or dishonest manner.

Discussion on executive pay often address only the amount of pay, not the type of pay. There are two main types of pay for company employees: individual performance-related and salary. Salaried pay may be augmented by overall company performance in the form of bonuses. Performance-related pay makes a difference for employees less exalted than board members. In a study using Australian data, Drago and Garvey (Citation1998) found that performance-related pay was a strong motivator of individual employees. However, it also served as disincentive to cooperative behaviour among employees. Bonuses, by contrast, seemed to make little difference except when work was both challenging and varied. In such circumstances, bonuses improved levels of cooperation. This suggests that, in cases where cooperation is paramount, performance-related pay hinders performance. By acting selfishly, employees (including board members) may mulct their employers. This suggestion is supported by Alchian and Demsetz (Citation1972) who found strong negative effects of performance-related pay in jobs that require much team effort. Thus, the optimum type of incentive may depend on the type of work being performed.

Against this, Fernie and Metcalf (Citation1999) found that jockeys performed the best when they received a share of the winnings and argue that similar may pertain in other professions including corporate executives. This argument may explain Jensen and Murphy (Citation1990; and see Main et al., Citation1996) finding that level of pay does not affect CEO performance that much, it might be, not the level of pay but the manner of payment. Fernie and Metcalf’s argument also accords with Byrne and Melcher (Citation1996a, 1996b) view that senior executive pay should be performance related. Further, although early research such as that of Jensen and Murphy suggested a weak association between level of senior executive pay and performance, more recent work suggests the relationship is much stronger, particularly when one considers the level of senior executive stockholdings (Hall & Liebman, Citation1998). In this regard, Fernie and Metcalf observe:

Most previous literature on this issue [CEO pay] has examined pay and performance of chief executive officers (CEOs). But generally, such studies do not test agency theory, they do not analyse how agents respond to different incentives. Rather, they simply calculate the strength of links between pay and performance, typically concluding until very recently that the relationship is very weak. (p. 386; emphasis original)

Based on the empirical studies conducted in different parts of the world covering developed and emerging economies, we may summarize our discussion on remedies to agency problem in above. The factors may be utilized by regulators keeping the local context into consideration while developing codes and guidelines for ensuring corporate governance.

Table 2. Remedies to agency problem.

5. Discussions