Abstract

This study investigates the complex relationship between small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMMEs) and socio-economic factors in post-apartheid South Africa. Hence, we use a robust econometric framework to assess how SMME proliferation affects job creation, income redistribution, infrastructural development and GDP growth during two pivotal periods (1995–2010 and 1995–2023). We employed an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model technique for analyzing relevant secondary datasets using the free EViews 12 student version (SV) x64 statistical software analytical package. During the period 1995–2010, we find that heightened SMME proliferation correlates positively and significantly with job creation, particularly in cases of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Moreover, the study underscores a direct link between SMME expansion and increased GDP growth, underscoring the vital role of these enterprises in shaping the economic landscape. However, in the extended period spanning 1995–2023, which encompasses both economic booms and recessions, the potential of opportunity-driven SMMEs wanes, attributed partly to business closures amid a recession. The major contribution of this study is that a combination of factors influences the impact SMMEs have on various socio-economic indicators. The insights gleaned from this research deepen our understanding of the intricate connections between SMMEs and broader socio-economic factors, offering valuable implications for policymakers and practitioners aiming to foster sustainable economic development.

Introduction

The vast disparities between first-world nations (Europe and America) and developing regions like Africa, Asia and Latin America prompt an adjustment of the grand challenges to address global issues (Buckley et al., Citation2017; GEM, Citation2023; National Treasury, Citation2023; Sustainable Development, Citation2015; The Economist, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2018). Globally, these grand challenges pose significant tests for individuals, companies, supranational bodies and governments, drawing attention to issues like poverty, migration, unemployment, inequality, terrorism, climate change and infectious diseases (Buckley et al., Citation2017; Egu, Citation2022). Building on the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) cover critical areas such as poverty, hunger, global warming, health, education, energy, gender equality, water, sanitation, urbanization, environment and social justice (Sustainable Development, Citation2015). Taken together, despite criticism of the 17 SDGs for being too numerous and sprawling (The Economist, Citation2015), addressing global poverty alone requires a staggering US $2–3 trillion annually for at least 15 years, a task unattainable without substantial support from private firms worldwide.

The World Bank Group’s (Citation2014) report indicates that 3.6 million South Africans were lifted above extreme poverty through cash grants (child support and old age pension) and free basic services in health and education. This figure has since ballooned to 18.6 million beneficiaries in March 2023 (National Treasury, Citation2023). Although South Africa outperformed 11 peer countries in reducing poverty and inequality through tax-based fiscal policies, escalating tax rates for the elite may hinder economic sectors through capital flight to tax havens. Currently, 16.5% of South Africans live in extreme poverty, with concerns that this figure may rise due to population growth and improved healthcare. Sadly, despite an improved Gini coefficient of 59%, high inequality persists. Scholars suggest that solely relying on tax-based fiscal policies and grants is insufficient for South Africa’s income redistribution schemes (Egu, Citation2022; Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023). Remarkably, encouraging entrepreneurship catalyzes the growth of small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs), creating jobs, enhancing income levels, and setting new standards to ameliorate inequality (Acs et al., Citation2023; Iftikhar et al., Citation2020; Musabayana et al., Citation2022).

Additionally, fostering an entrepreneurial base would boost South Africa’s macroeconomic performance, promoting sustainable economic growth and development. Government spending estimates from the 2016 and 2023 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement indicate increasing costs in various sectors, with social protection for poor South Africans, projected to rise from R 164.9 billion in the 2016/17 review period to R 263 billion by 2023/24 (National Treasury, Citation2023; The Treasury, Citation2017). Despite the government’s commitment, South Africa’s substantial debt profile constrains spending on social protection programs. With debt relief unlikely due to its middle-income status and decreasing foreign aid, a comprehensive study in this research area becomes imperative.

Addressing South Africa’s core economic challenges requires a shift from social protection fixation to boosting SMMEs’ job-creating capacity, thereby alleviating poverty and reducing inequality. Therefore, prioritizing reforms aimed at creating a conducive business environment for SMMEs would empower them to contribute significantly to job creation, income redistribution and sustainable economic growth. Given the above scenario, we propose in this study that SMMEs play a pivotal role in income redistribution, employment, infrastructural development and gross domestic product (GDP) growth in South Africa, thus contributing to SMME literature. In contemporary literature studies, research on social protection has always been an isolated phenomenon, this article, therefore, contributes to the literature by stating how income redistribution schemes assist beneficiaries to begin their businesses, which has not been well-treated in prior studies. The research findings enhance comprehension of the intricate interplay between SMMEs and wider socio-economic elements, providing valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners striving to promote sustainable economic development, thus justifying its relevance and publication. The subsequent sections review relevant literature, develop hypotheses, introduce the research methodology, present empirical results, discuss findings and conclude with implications for future research.

Background literature of the study

Act 200 of the 1993 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa aims to safeguard, monitor and penalize any violations of the fundamental human rights of all citizens and residents of the Republic (The Human Rights Commission Act, Citation1994). Similarly, the Department of Social Development (DSD) and the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA), as mandated by the constitution, hold the powers and responsibility to oversee social protection programs through laws like the Social Assistance Act (Citation2004), the Children’s Act (Citation2005), the Older Persons Act (Citation2006), the Non-Profit Organisation’s Act (Citation1997), the Social Services Professions Act (1978) and the Prevention of and Treatment for Substance Abuse Act (Citation2008) (UNICEF South Africa, Citation2017). Freund (Citation2010) estimated that approximately 25% of South Africans receive government welfare grants, primarily benefiting females and a limited number of elderly individuals. Despite the significant number of homes built (4,000 in Soweto alone), housing shortages in South Africa persist, exceeding 2 million homes nationally, and the country has built more homes than any other globally (NHFC, Citation2016).

The Bill of Rights (No. 108 of 1996), Chapter 2 of the Constitution, delineates the fundamental rights of all South Africans, emphasizing the promotion and protection of dignity, equality and freedom (Bill of Rights, Citation1996). Article 27 explicitly states the right to healthcare, food, water and social security, with an obligation for the state to provide social assistance for those unable to support themselves and their dependents. The National Planning Commission’s (NPC) national development plan (NDP) aligns with the Constitution, aiming to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030 (NPC, Citation2012). To achieve this, the NDP underscores the need for collaborative efforts to foster an inclusive economy, build essential capabilities, and elevate living standards above the poverty level through higher investments, employment, productivity growth, a social wage and efficient public service.

For South Africa to attain optimal economic growth, advocating for an open society, transparency, disclosure, tolerance, equity, peace, security and accountability leading to social cohesion is imperative (Heritage Foundation, Citation2023). Social security and safety nets, while beneficial, face challenges due to rising population growth, escalating debt rates and declining government revenues. The debate on providing cash transfers to families below the poverty line has gained attention. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) have been successful globally in reducing poverty, enhancing human capital and improving short-term outcomes. However, the sustainability of such programs, especially during economic recessions, is questionable (Egu, Citation2022). CCTs are deemed less advantageous than investments in public capital by the NPC (Citation2012), as they are harder to target and deliver nationwide. The unintended consequence has been a diminished incentive for citizens to actively participate in their development, highlighting the importance of strong leadership from business, labor, civil society and government in the NDP’s implementation.

While CCTs receive acclaim, their sustainability remains in doubt, particularly during economic downturns, as evidenced in the former USSR, Mexico, Honduras and Venezuela. Fiszbein and Schady (Citation2009) argued that even well-designed programs cannot universally meet the needs of a social protection system due to attached conditionalities. Market failures offer opportunities for entrepreneurial risk-taking, potentially facilitating efficient income redistribution nationally (Chancel et al., Citation2022). However, credit market imperfections may disadvantage the poor, creating a dilemma for the government in continuing such programs. Freeland (Citation2007) criticized CCTs as unrealistic and corrupt, advocating for government and private sector support of SMMEs nationally.

Excerpts from the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) reveal that the social development sector, encompassing the DSD, its agencies and provincial regional governments, is projected to allocate approximately R 263 billion for social grants to impoverished, orphaned and disabled individuals nationwide (). This spending aligns with the NPC’s (2012) NDP, endorsing a social protection floor to prevent anyone from falling below a specified level, following Section 27 of the Constitution recognizing social security as a fundamental right for all South Africans (Bill of Rights, Citation1996). This implies that over the MTEF coverage period, the DSD’s allocation of R 1.10 trillion will be used to fund social grants, welfare services and advocacy efforts for empowering women, youth and people with disabilities. Coupled with the contagion of the COVID-19 pandemic, over the MTEF period, the payment of social grants will account for about 96.4% (which is approximately R735.2 billion) of the department’s total budget.

Table 1. Programme spending and allocations in the budget of the national Department of Social Development, 2022/23 to 2025/26 (ZAR million).

indicates that social assistance constitutes the major portion of this fund, with the old age grant receiving R 99.1 billion for payment to 4 million beneficiaries, while the disability grant includes lump sum payments of R 26.8 billion to 1.1 million recipients, and care dependency grant R 4.1 billion, used to provide a lump payment of approximately R 2,085 to all grant recipients monthly (National Treasury, Citation2023; UNICEF South Africa, Citation2017). Additionally, the child support grant of R 81.9 billion was paid to 13.5 million persons, and the foster child grant of R 3.8 billion is earmarked to transfer monthly payments of R 1,125, while beneficiaries of the child support grant would get R 505 monthly. Taken together, the disbursement of the COVID-19 special relief fund to about 8.5 million recipients would increase the total number of eligible social grant beneficiaries to 27.4 million within the 2023/24 budgetary period (National Treasury, Citation2023). Despite the substantial budget, the overwhelming number of impoverished households in dire need tends to overshadow the allocated amount for social grants (Bastagli et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Nominal values of key social grants in 2023/24 (ZAR billion).

We, therefore, advocate for the utilization of SMMEs to facilitate income redistribution, given their anticipated high turnovers and payments in the economy. This approach would enhance productivity, reduce idleness-related crimes and violence, and foster altruistic social and capital formation for sustainable growth and development (Saavedra, Citation2016). Furthermore, we envision increased participation by South Africans in the lucrative SMME sector, particularly addressing the daily needs of millions in rural and shanty town dwellings, currently dominated by individuals from Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, Zimbabwe, Nigeria and Ghana.

Existing evidence indicates that achieving an increase in employment levels from 13 million in 2010 to 24 million in 2030 in South Africa necessitates the creation of 11 million jobs, with the government having the capacity to generate only around 2 million jobs, leaving the private sector responsible for creating approximately 9 million jobs by 2030 (GEM, Citation2023; Herrington et al., Citation2017; Herrington & Kelly, Citation2012; NPC, Citation2012). Without the private sector’s contribution, the government would have to allocate about R 4.609 trillion annually to support 9 million unemployed South Africans, aiming to eradicate income poverty and elevate poor households to earn at least R 419 per month, reducing the percentage of households earning below this threshold from the current 39% to zero. Achieving this solely through government efforts is deemed impossible (The National Small Business Amendment Act, Citation2004), emphasizing the necessity to endorse initiatives supporting the establishment of numerous SMMEs nationwide. Additionally, realizing the NPC’s (2012) NDP vision, fostering leadership and strategic partnerships across South African society, relies on collective efforts, resources and inputs. SMMEs play a pivotal role in constructing an inclusive rural economy, an absent component in the South African economic landscape. This approach is forecasted to elevate the GDP to approximately 2.7 times the projected real terms, fostering an annual GDP growth of 5.4% until 2030. Concurrently, the GDP per capita is anticipated to rise from the conservative R50,000 per person in 2010 to the projected figure of R120,000 per person in 2030, potentially leading to an increased share of national income for the bottom 40%, rising from the current 6 percentage points to around 10 percentage points by 2030.

Theoretical support for SMME intermediation

Scholars engage in a global debate over the precise definition of SMMEs, with varying terms used across different regions. The National Credit Regulator (Citation2011) notes that small businesses are commonly referred to as small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the European Union (EU), Malaysia, China and Russia, as well as by the World Bank, the United Nations (UN) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). India and Ghana employ the term micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME), while South Africa uses small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs) in its entrepreneurship literature. The United States prefers the terminology of small and medium businesses (SMBs) in relevant studies. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development—OECD (Citation2006), defining an SMME is complex, reflecting economic patterns and socio-cultural idiosyncrasies. The National Small Business (NSB) Amendment Act (29 of Citation2004) provides a comprehensive definition based on standard industrial classification, categorizing firms by size, equivalent employees, turnover and asset value.

Regional studies by the European Commission (Citation2014) indicate that SMMEs constitute about 99% of all businesses in the EU, employing around 33 million individuals. Similar trends are observed in China and India, where SMMEs represent 99% of businesses, contributing 45% of jobs in India and totaling 10.3 million companies in China. In Ghana, 92% of companies are SMMEs, while in Russia, Malaysia and South Africa, SMMEs constitute 94%, 97.3% and 91% of all businesses, respectively. The Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas—SEBRAE (Citation2012) underscores SMMEs as expressions of free initiative, social inclusion and citizenship, deserving government support. Kushnir et al.’s (Citation2010) study indicates 125 million formal SMMEs globally, with South Africa projected to have a density of 31–40 SMMEs per 1,000 persons, aligning with Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) rate figures.

Despite the widely held belief that SMMEs drive economic growth and balanced development, the size of these firms poses challenges in capturing market opportunities due to diseconomies of scale, lack of skilled manpower, poor market intelligence, logistics and reliance on labor-driven low-tech manufacturing bases. Nevertheless, SMMEs significantly contribute to economic growth as job creators and income redistribution agents. Recent SME Growth Index (Citation2015) studies correlate SMME sustainability and growth with wealth creation, prompting government policies promoting SMME participation in the mainstream economy. However, the impact of the 2008 financial crisis, coupled with factors such as insufficient financing, stringent government policies, low educational training, poor research and development, entry restrictions and unsupportive socio-cultural norms, has led to a decline in SMME numbers in South Africa. The Department of Small Business Development (DSBD), therefore, intervenes by investing in approximately 300,000 SMMEs annually, aiming for a 5% GDP growth and generating five million jobs in 5 years (DSBD, Citation2016).

Entrepreneurship, according to Oparah (Citation2023), is the business of wealth creation, with countries exhibiting the least entrepreneurial spirit often ranking among the world’s poorest. Scholars attribute the lack of enterprise, particularly SMMEs, as a primary cause of poverty in less developed countries (LDCs). The active contributions of SMMEs to South Africa’s economic growth include being significant job creators, employing around 80% of the total workforce, and having the potential to reduce the current 27% unemployment rate. For South Africa to meet the NDP target of creating 11 million jobs by 2030, over 49,000 SMMEs growing at a rate of 20% per annum are needed (Fin24, Citation2015). SMMEs facilitate wealth creation, sharing and redistribution, contributing to economic equality and transforming societal structures (Egu, Citation2022). Additionally, SMMEs enhance living standards by creating jobs, reducing prices and introducing new products and services, thereby fostering economic growth and inclusive development. SMMEs also play a role in balancing regional economic growth by operating in areas where large businesses find it unprofitable. Furthermore, they stimulate innovation, expand into foreign markets, diversify businesses through exports and contribute to corporate social development by investing in sustainable social projects, positioning themselves as responsible corporate citizens.

Conceptual development

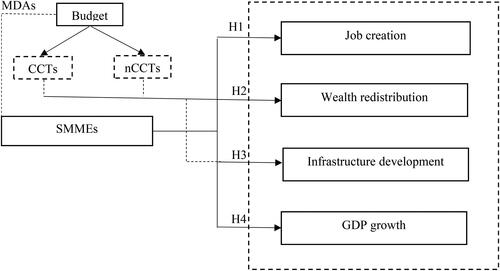

The World Inequality Report (Citation2018, p. 145) highlights South Africa’s stark divergence in individual income and wealth inequality, with the top 10 percent controlling 2/3 of national income, and the top 1 percent holding 20%. According to Chancel et al. (Citation2022), South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world with average national income of R 117,260 dwarfing the bottom 50% earnings of R 12,340—accounting for 5.3% of the total with the top 10% earning 60 time more—accounting for 65% of the total national income. Shockingly, the top 10% own about 86% of total national wealth, while the share of the bottom 50% is negative due to their reoccurring debt obligations dwindling assets. Although SMMEs are recognized globally as job aggregators with the capacity to contribute to wealth redistribution (Egu et al., Citation2016; Herrington et al., Citation2017; Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023; GEM, Citation2023), government intervention has mitigated poverty and inequality, narrowing interracial income gaps. However, the successful B-BBEE program inadvertently intensified inequality within the black and Asian populations, hindering an overall reduction in South Africa’s inequality (Chancel et al., Citation2022; Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023; Heritage Foundation, Citation2023; Lierse et al., Citation2022; World Inequality Report, Citation2018). This underscores that government measures alone are insufficient to address a deeply unequal socio-economic structure. Additionally, the impact of Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) and non-conditional cash transfers (nCCTs) has been limited due to demographic variations, ethnic rivalries, tribal conflicts and corruption (see ).

Despite the crucial role of redistributive justice, escalating poverty and inequality may shrink resources for tackling these issues, along with the efficiency costs and expected benefits of redistribution over time (Saavedra, Citation2016). In this precarious scenario, the existence of CCTs and nCCTs targeting the poor raises concerns for the government due to budgetary constraints in executing social protection programs (Fiszbein & Schady, Citation2009). Crises in regions like Libya demonstrate that even the most generous social protection schemes cannot guarantee the prevention of social disasters like protests, conflicts and wars constituting national security threats. Moreover, the high youth unemployment rate (currently around 65%) correlates with the rising crime rate in South Africa (GEM, Citation2023; Herrington et al., Citation2017), turning a potential national asset into a persistent source of instability. The United Nations Office for West Africa—UNOWA (Citation2005) asserts that job creation is a sustainable tool for conflict prevention, inclusion and economic growth. With support from government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs), SMMEs, as job creators, can transform this potential instability into a positive force for development.

Studies by the NPC (Citation2012), Egu and Aregbeshola (Citation2016, Citation2017) and Herrington et al. (Citation2017) indicate that South Africa stands as the most sophisticated economy in Africa, boasting an upper middle-income status, G-20 membership, and active participation in the BRICS group. As an African superpower, it possesses advanced infrastructure, giving firms operating within its borders a comparative advantage over other nations on the continent (World Investment Report, Citation2018). Despite these advantages, many companies grapple with complex business regulations, bureaucracy and corruption (GEM, Citation2023; Herrington et al., Citation2017). Recognizing the potential for improvement, we propose leveraging the nation’s human and material resources. An interventionist program of this nature could effectively address multifaceted issues of poverty, unemployment and economic exclusion by fostering the operation of numerous SMMEs. These enterprises would engage the unemployed workforce, converting underutilized resources into value-added products and services for domestic or international markets (Sy, Citation2014). The conceptual model in outlines the theoretical framework, presenting our argument that SMMEs, through a non-interventionist wealth redistribution process, create jobs and generate income, lifting many households out of poverty. This process, in turn, reduces the government’s resource burden in social protection programs. Over time, this dynamic would allow both the government and private businesses to make significant investments in nationwide infrastructural development projects. We anticipate that the growth of SMME revenue and population will contribute to increased GDP levels, all else being equal.

Hypotheses

Our baseline hypothesis, as elucidated in the preceding section, posits that SMMEs actively contribute to wealth and income redistribution while concurrently creating jobs, thereby alleviating poverty. With reduced allocations to social protection programs due to households emancipating from poverty, government budgets for infrastructural development escalate, resulting in improved social amenities that positively impact citizens’ lives and support increased production. This, in turn, propels South Africa’s GDP growth, elevating living standards.

Job creation intermediation of SMMEs

Various research studies, including those by Deakins and Freel (Citation2012), Herrington et al. (Citation2017) and GEM (Citation2023), establish a strong link between macroeconomic development and the substantial growth potential of SMMEs. Small businesses, proven employment generators, offer cost-effective solutions for catering to low-income households. Affirmative ‘preferential’ procurement strategies aim to empower previously disadvantaged communities and foster a culture of entrepreneurship (Egu, Citation2022; Egu & Aregbeshola, Citation2017). However, current government interventions provide only short-term solutions. To realize sustained economic growth, engaging idle individuals in productive activities is imperative. This is because unemployment, especially among the youth, contributes to social, economic and political challenges (Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023). The rapid rise of unemployed youths poses a crisis to the South African economy. SMME intervention emerges as an alternative approach to addressing this longstanding issue, offering promise for a secure future for this population segment.

According to Berry et al. (Citation2002), SMMEs are not only employment generators but also crucial upgraders of human capital, expanding the country’s capital base, alleviating poverty and enhancing competitiveness. In the face of South Africa’s current account imbalance and escalating debt, SMMEs present an opportunity for efficiently distributing resources within the small business sector, addressing a major economic challenge (Acs et al., Citation2023; Lien, Citation2024; Lierse et al., Citation2022). Our prediction posits that the widespread proliferation of SMMEs would accelerate economic growth, accumulating income and wealth, thereby mitigating nationwide unemployment. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1:

Higher levels of SMME proliferation are positively associated with increased job creation in South Africa.

SMMEs as a tool for income and wealth redistribution

Research by Berry et al. (Citation2002), Chalera (Citation2006) and Agba et al. (Citation2014) highlights the positive impact of micro-enterprises on productivity and their role in achieving government poverty reduction goals. SMMEs, by engaging idle human resources, function as instruments for poverty alleviation in South Africa. Elevated labor productivity leads to increased wages, pushing workers above the poverty line, thus contributing to income and wealth redistribution (GEM, Citation2023). Notably, large businesses in South Africa have historically been associated with inequitable income distribution despite their significant contribution to national growth (Chancel et al., Citation2022; Lierse et al., Citation2022). SMMEs act as catalysts for competition and resource reallocation into underserved markets, such as those comprising females, disabled, aged, youth and rural families. The social protection mechanism of the government proves inadequate for the vast households constituting the societal pyramid base. Addressing these challenges, our study suggests that SMMEs can play a crucial role in job creation, income redistribution and wealth redistribution in South Africa. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2:

An increase in the number of SMMEs in South Africa would lead to higher levels of income and wealth redistribution.

The link between SMME growth and infrastructural development

While South Africa boasts the best infrastructure in Africa, enhancing efficiency in social amenities is essential for supporting the National Planning Commission’s Vision 2030 growth projections. Strategic investments in energy, transportation, healthcare, education and other sectors have been geographically dispersed, addressing historical disparities and meeting the demands of a growing economy and population (National Treasury, Citation2023). Although public infrastructure is primarily financed by public-private partnerships, tariffs, taxes and loans, these arrangements are not standalone solutions (Musabayana et al., Citation2022). Transparent procurement mechanisms via PPPs free resources, enabling SMMEs to leverage both local and international funds for affordable and standardized infrastructure development. Existing literature supports the hypothesis that increased infrastructural spending is positively associated with higher SMME figures in South Africa (Egu, Citation2022; Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023). Enhanced infrastructure is expected to stimulate economic connectivity, attract investments and promote business networks, ultimately leading to an increase in the number of SMMEs. Thus, we formulate our third hypothesis, as follows:

Hypothesis 3:

An increase in infrastructural development levels in South Africa will likely lead to higher levels of comparable growth in the number of SMMEs in the country.

The role of SMMEs in the expansion of the GDP growth levels

SMMEs play a pivotal role in the South African economy, accounting for approximately 91% of total companies, employing 80% of the workforce, and contributing to 34% of the GDP (Egu, Citation2022; Herrington et al., Citation2017). The number of SMMEs serves as a key indicator of GDP growth, reflecting the total output of goods and services. South Africa’s GDP projections outlined in the National Planning Commission’s NDP require substantial support for SMMEs through government intervention programs to stimulate the economy (Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023). The cascading effect of SMMEs on economic production and GDP growth is expected to positively impact all sectors of the economy, reducing poverty rates, pushing the Gini coefficient downward and raising the per capita income of South Africa. This leads to the formulation of the fourth hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 4:

An increase in the number of SMMEs in South Africa would certainly cause a directly proportional growth in GDP levels.

Data

We gathered macroeconomic variables from diverse sources to construct a comprehensive dataset for our investigation. Utilizing the latest, systematic and transparent data with a cutting-edge methodology, the World Inequality Report (WIR) emerged as a crucial data source for measuring both income and wealth inequality. The World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) provided up-to-date and precise development indicators compiled from internationally recognized sources. The DSBD data, focusing on the number of SMMEs in South Africa, offered insights into the performance of small businesses during our selected period.

Our study spans from the financial year following the end of apartheid in 1995–2023. The choice of the WIR data was driven by its comprehensiveness, transparency and systematic approach, facilitating informed public debates on inequality. The WDI data, another cornerstone, ensured the inclusion of globally recognized development indicators. Additionally, DSBD data allowed us to gauge SMME performance, while the National Treasury’s annual Budget Speech and Review provided critical insights into social protection spending, including both social security and welfare expenditure. To measure the rate of entrepreneurial activity/intention in South Africa, we utilized the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s (GEM) TEA rate, reflecting the percentage of the working-age population either about to start or within the first 3 years of starting an entrepreneurial activity. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom score of South Africa was instrumental in evaluating the impact of a free-market economy on SMMEs’ performance and its effect on income inequality. Moreover, we collected 20 variables from the World Bank’s WDI. Besides, all the variable labels were identified, and described, and their sources were clearly stated in . Additionally, the comprehensive selection of variables from reputable sources (as mentioned in ) also guarantees the robustness and reliability of our econometric estimation to arrive at conclusive findings.

Table 3. Variable description and measurement.

Construct validity and reliability

Our study’s estimation process unveiled that the work file statistics data were structured annually, defined by a date series coded as ‘Year’. Notably, the variables in this study averaged 22 observations. The data object, consisting of 26 series (including residuals) and 754 data points, along with a coefficient featuring 750 data points, constituted a total of 27 variables and 1,504 data points (Wooldridge, Citation2013). To fortify the validity and reliability of our findings, we conducted an estimation of the principal factors using the minimum average partial (MAP) number of factors. This involved initial communalities, employing a squared multiple correlation (SMC) and a generalized inverse covariance matrix.

The unrotated loadings (F1 and F2) were identified based on robust commonality and uniqueness (Velicer, Citation1976). Kaiser’s Measures of Sampling Adequacy (MSA), assessing the suitability of data for common factor analysis, yielded a value of 0.55, indicating acceptability despite some limitations. Unrotated validity coefficients for F1 had a variance of 14.78 and F2 had a variance of 4.16 yielding a total variance of 18.94, with SMC totaling 24.77, further supported the reliability of our model. A factor scores biplot graph (not reported), showcased orthonormal loadings biplots revealing that component 1 accounted for 59.1 percent of F1 loadings, while component 2 contributed 16.7 percent. The goodness-of-fit summary, including the LR test, absolute fit indices, and incremental fit indices, confirmed the adequacy of our econometric estimation, meeting the recommended thresholds (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Additionally, the Cronbach alpha (α) test surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.70, reaching 0.95, ensuring the internal consistency of our dataset. Unit root tests, series stationarity, and cointegration analyses affirmed the stability and long-run relationship among econometric variables (Hatemi, Citation2008; Woodward et al., Citation2012). Further, residual diagnostic tests demonstrated the absence of serial correlation and heteroskedasticity in our dataset, underlining the robustness of our model data, thus guaranteeing the validity and reliability of the outcome of the regression analyses.

Methodology

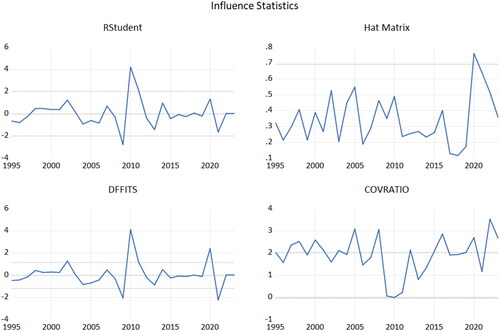

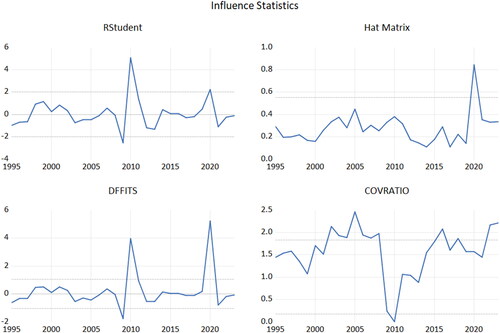

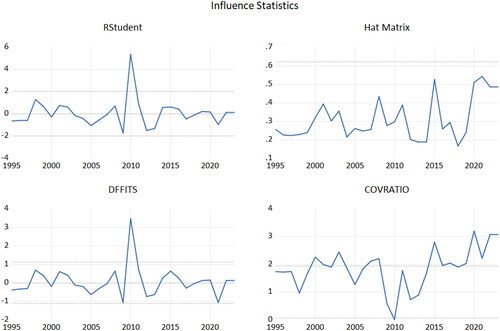

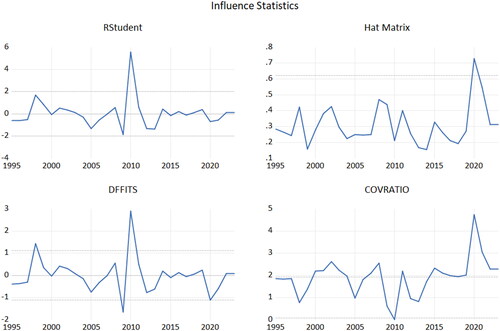

To navigate the intricacies of our investigation, we employed the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model technique for analyzing the econometric variables, prioritizing conceptual simplicity and computational ease (Wooldridge, Citation2013). Besides, we transformed absolute values to yield more accurate outcomes. This approach, chosen to mitigate estimation biases and ensure consistency, assumes a stationary stochastic process and follows the relationship y = f(x), where y is the dependent variable and x is the independent variable. The OLS analyses were conducted using the free EViews 12 student version (SV) x64 statistical software analytical package, and modular table effects were illustrated to validate our model, as demonstrated by influence statistics () which confirmed correct model specification, diagnosing potential failures of underlying assumptions and managing influential observations and outliers (EViews, Citation2022).

Model estimation

Moving to model estimation, we meticulously developed the econometric estimation equation to test hypotheses, ensuring its robustness and absence of collinearity. Addressing multicollinearity concerns, noncompliant variables were excluded from the model. Our unbiased estimator takes the form 𝑌 = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + … βnXn + ε, encompassing the dependent variable (𝑌), constant factor (β0), coefficients (β1 to βn), independent or explanatory variables (X1 to Xn), time (t) and the random error term (𝜀).

Results

(in the Appendix section overleaf) presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for our dataset, indicating a well-distributed sample devoid of complications such as multicollinearity (Wooldridge, Citation2013). Validation and reliability tests in the previous section supported the convergent, discriminant and nomological validity of our model. These tests confirm that our model aligns well with the data and supports the subsequent statistical analysis of the econometric variable regression and correlation. To test hypotheses, we utilized an OLS approach, presenting four interrelated models in covering intervals from 1995–2010 and 1995–2023, which inter alia reports the standardized coefficients, standard errors, significance levels, year effects, number of observations, log-likelihood, R2, Adjusted R2, sum of squared residuals and F-statistic. Interestingly, these models, capture trends and socio-economic impacts in post-apartheid South Africa.

Table 4. OLS regression analysis.

Model 1 A focuses on the relationship between SMME proliferation and job creation (i.e. Hypothesis 1). During 1995–2010, a significant relationship (p < 0.05) was observed, supported by a strong adjusted R2 value of 87%. This indicates a positive and significant relationship between the econometric variables which is consistent with the findings of GEM (Citation2023). Besides, positive TEA rate results (p < 0.1) align with earlier studies (GEM, Citation2023; Herrington et al., Citation2017). However, the rate of inflation (InflationR) exhibited a negative relationship (p < 0.01) with the number of SMMEs in South Africa. Furthermore, Model 1B, addressing cyclical effects, showed nonsignificant positive relationships between SMMEs and job creation over a longer period (1995–2023), reflecting monetary policy adjustments. We find that the rate of inflation (InflationR) and the depth of poverty, as well as its incidence (PovertyGap), were negative and significant (p < 0.1) with the number of SMMEs in South Africa. This is consistent with the findings of the GEM (Citation2023) report, which prioritizes the concept of necessity-driven entrepreneurship in the disadvantaged demographic segment of society, whereas affluent neighborhoods would tap into opportunity-driven entrepreneurial ventures. This is why the rate of unemployment (UnemployR) is positive and significantly associated (p < 0.1) with the number of SMMEs in South Africa. Notably, high bank lending rates remained directly related to SMMEs during the recessionary period. Whereas, nonsignificant positive relationships existing between SMMEs and job creation suggest that monetary policy adjustments impact production and employment boosts, in combination with other exogenous factors.

Models 2A and 2B tested Hypothesis 2, examining if an increased number of SMMEs in South Africa leads to higher income and wealth redistribution. From our econometric analysis, Model 2A revealed positive relationships with EcoFreedom (p < 0.1), SocialBudget (p < 0.01), TaxRev (p < 0.01), UnemployR (p < 0.01), and negative relationships with the Intercept (p < 0.05), and FiscalYInequality (p < 0.01). This implies that if South Africa becomes a freer economy, competitive trade regimes will thrive and encourage the growth and development of the entrepreneurial sector (Heritage Foundation, Citation2023). Nevertheless, higher rates of corruption and inapplicability of the rule of law would add to the cost of doing business in the country (Egu & Chiloane-Tsoka, Citation2023). Moreover, an increment in social payments would give the disadvantaged recipients some income to set up new businesses. And, when these businesses are formalized via registration they are captured in the tax net with positive externalities for the economy, which is consistent with the findings of Bastagli et al. (Citation2019) and WIR (2022). On top of that, the higher the unemployment rate, the higher the rate of necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities in the country to drive the subsistence level of the unengaged sectors of the economy (GEM, Citation2023).

Remarkably, the negative and significant intercept (p < 0.05) suggests that jointly, the independent variables impact the number of SMMEs in South Africa due to a myriad of issues, ceteris paribus. Just as the total fiscal income inequality is also negatively related to the number of SMMEs in South Africa, consistent with the findings of Egu (Citation2022). While the adjusted R2 value of 98 percent and (p < 0.01) suggests that our model supports the hypothesis for the period 1995-2010. However, Model 2B, covering the extended period (1995-2023), indicated the reduced potential for opportunity-driven firms post-2010 accentuated by the economic and political issues confronting the country. Taken together, SMME’s potential decline can be linked to business closures post-2010 FIFA World Cup.

Furthermore, Hypothesis 3, exploring the relationship that exists between infrastructural development and SMME growth, was tested in Models 3 A and 3B. Model 3 A shows positive and significant associations between the level of infrastructural development and SMME growth during the 1995-2010 period, with an adjusted R2 of 81 percent (p < 0.01) supporting the veracity of Hypothesis 3. We also observed that government expenditure on education i.e. GovExpEducation (p < 0.1) and the number of internet users in South Africa i.e. InternetUsers (p < 0.05) was positively and significantly related to SMME growth (Acs et al., Citation2023; Musabayana et al., Citation2022). Conversely, Model 3B, spanning 1995-2023, did not indicate a significant relationship between augmented infrastructural development positively impacting SMMEs in South Africa. Unexpectedly, the relationship that exists between infrastructural development levels and the number of SMMEs in South Africa was negative and significant for the level of gross fixed capital formation in current US $ in South Africa i.e. GFCFcurrent (p < 0.1). Probably due to declining foreign exchange levels between the value of the South African rand vs. the US dollar, which makes import-reliant businesses more expensive. This is consistent with the findings of Egu (Citation2022), and Egu and Chiloane-Tsoka (Citation2023).

For Hypothesis 4, predicting a proportional growth in GDP with an increase in SMMEs, Models 4 A, 4B, and 4 C were analyzed. Model 4 A showed a positive and significant relationship (p < 0.01) between the proportional growth in GDP with an increase in the number of SMMEs in South Africa, with an adjusted R2 of 82 percent supporting the veracity of our hypothesis during the period spanning 1995-2010. Expectedly, we observed significant positive relationships between GDPc and GDPgr (p < 0.01) in relation to increases in the number of SMMEs in South Africa, which is consistent with the findings of Iftikhar et al. (Citation2020), Egu (Citation2022), and Acs et al. (Citation2023). Supporting the spillover effects of entrepreneurship on economic growth in a developing country context. While FiscalYInequality (p < 0.1), GDPpc (p < 0.01), and GDPpcPPP (p < 0.01) exhibit negative and significant relationships with the dependent variables, indicating the presence of economic inequality effect and exogenous pressures like interest and inflation rates on their income levels over time. Thereby limiting the active participation of citizens in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in South South Africa as enumerated in previous studies (Egu, Citation2022; World Inequality Report, Citation2018). Whereas, in Model 4B, covering 1995–2023, the hypothesis was not supported, except that the gross fixed capital formation in current US $, i.e. GFCF_GDP was negative and significant (p < 0.1). This suggests changing dynamics in these relationships after the 2010 FIFA World Cup that was hosted by South Africa, especially with the fall in the value of the South African rand impacting import-dependent small businesses.

Interestingly, Model 4C (a robust model comprising all the macroeconomic indicators of the study) demonstrated a positive relationship (p < 0.1) between the intercept of the independent variables and the number of SMMEs, with an adjusted R2 of 81% (p < 0.05) supporting the veracity of our hypothesis during the period spanning 1995–2023. This implies that a combination of factors impacts SMME performance over time in South Africa cascading into sustainable economic growth and development, which is consistent with the findings of Herrington et al. (Citation2017) and Egu and Chiloane-Tsoka (Citation2023). More importantly, we find that there exists a positive and significant relationship between DomCreditBanks (p < 0.1), FiscalYInequality (p < 0.1), GFCFcurrent (p < 0.01), InternetUsers (p < 0.1), LendingRate (p < 0.1), SocialBudget (p < 0.1) and UnemployR (p < 0.01) with the number of SMMEs in South Africa over time. However, the rate of unemployment is by far a more influential motivating factor for business creation during this period, just as capital formation, availability of domestic credit from banks, the lending rate, social grants and the level of fiscal income inequality are moderating factors on this phenomenon. On the contrary, ExternalDebt (p < 0.05), GDPgr (p < 0.05), GFCF_GDP (p < 0.01), GiniIndex (p < 0.1), GovExpEducation (p < 0.1) and HealthExpend (p < 0.05) demonstrated negative and significant relationships with the dependent variable, indicating the influence of exogenous pressures like government external debt, government expenditure on education, health expenditure, rising Gini index impacting on the GDP growth rate and the gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of the GDP during this period. This is consistent with the findings of Egu (Citation2022) and Egu and Chiloane-Tsoka (Citation2023).

Thereafter, the results of the Granger causality tests that were conducted are reported in of the Appendix section overleaf. It indicates the existence of a positive and statistically significant causality between the number of SMMEs and eight econometric variables, including DomCreditBanks, GDPpcPPP, GFCF_GDP, HealthExpend, LendingRate, NetBorrowing, PovertyGap and TaxRev. Notably, all of these variables exhibit unidirectional causality. Despite these findings, external factors like government monetary and fiscal policies could influence the economy. Increased inflation and exchange rates negatively impact SMMEs, emphasizing the need for robust planning and risk management. Additionally, poverty’s negative correlation with SMMEs suggests social security and welfare support could drive entrepreneurship, contributing to reduced unemployment in the long run. A Granger causality test underscores the dynamic nature of these relationships. In summary, our analysis supports the hypotheses, affirming relationships between SMMEs and various economic indicators. However, caution is warranted, acknowledging external factors influencing the econometric estimation.

Discussions

Motivated by the call for papers addressing under-researched or controversial topics such as grand challenges, this article aims to inspire new, impactful research. Previous studies focused on specific niche areas like inequality, unemployment, SMME development and poverty reduction strategies, limiting their scope. Recognizing the need for a nuanced treatment of poverty as a multidisciplinary and multidimensional problem, we conducted research that delves beyond economic factors, considering cultural elements such as caste systems and racial/class issues. Our study explores the strong positive association between the number of SMMEs and job creation, income and wealth redistribution, infrastructural development and GDP growth during the expansionary period (1995–2010). However, this relationship weakens during recessionary periods, highlighting the long-term impact of low output growth on poverty. We advocate for increased capital formation and accumulation to support private sector-driven economic growth as a comprehensive poverty reduction strategy.

Contributions to theory and practice include establishing the positive association between SMMEs in South Africa, GDP growth rate and GDP at market prices (during periods of economic boom), albeit with its riveting implications with sound monetary and fiscal policy adjustments during macroeconomic shifts. We align with prior research on wealth inequality triggers, suggesting a shift in South Africa from the Kitchin inventory cycle to an extended Juglar fixed-investment cycle. Anticipating the infrastructural investment cycle, we predict a Kuznets swing within the next 3–10 years. Factors such as strikes, civil unrest and xenophobia attacks contributed to the economic downturn, leading to business closures and production cuts. We recommend the inclusion of young boys and men in social protection schemes, regular discussions between stakeholders, and corporate social responsibility programs to enhance the relationship between businesses and host communities. Addressing xenophobia and reducing political hate speeches are crucial to preventing larger crises.

Analyzing macroeconomic variables, we find negative relationships between the inflation rate, poverty gap, fiscal income inequality, external debt levels and the number of SMMEs. We propose interventions like subsidies, grants and trade incentives to protect vulnerable small businesses. Addressing judicial effectiveness, government integrity and investment freedom can alleviate market uncertainties. To promote wealth redistribution, we suggest fortifying positive econometric proxies, creating enterprise investment incentives and supporting infrastructural development. While acknowledging the success of the B-BBEE program, we recommend a mixed approach to address rising income inequality within the black and Indian population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study empirically demonstrates the substantial positive impact of SMMEs on job creation, income and wealth redistribution and GDP growth in South Africa. We advocate for increased media coverage of entrepreneurial initiatives to stimulate interest and participation, thus fostering a more inclusive and sustainable economic growth model. Moving forward, further research is necessary to explore sector-specific impacts and refine our understanding of SMMEs’ role in poverty alleviation and wealth redistribution, while assessing the scalability of successful SMME models across diverse contexts for effective policy implementation and sustainable economic development.

One recommendation stemming from our study is the need for policymakers to formulate targeted interventions aimed at fostering the growth of SMMEs, particularly during economic downturns, to mitigate job losses and stimulate economic activity. However, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of our research, including the reliance on secondary datasets and the absence of sector-specific analyses, which may have restricted the depth of our findings. Therefore, future studies should employ primary data collection methods and delve into sector-specific dynamics to provide more nuanced insights into the relationship between SMMEs and socio-economic factors, thus informing more effective policy interventions and strategies for sustainable economic development.

Author contributions

The corresponding author, Mathew E. Egu, was involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data and the drafting of the article. Germinah E. Chiloane-Tsoka revised the article critically for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the 19th International Academy of African Business and Development (IAABD) conference that was held in Durban, South Africa for their insightful comments, suggestions and contribution to the earlier version of this article, without which some contentious aspects of this research would have undermined the findings of this study. The authors, however, expressly state that the views (i.e. opinions) and findings of this study are exclusively those of the authors. Furthermore, they also acknowledge the contributions of the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

There are no interests to declare in this article.

Data availability statement

The secondary data used in this study are freely available and can be accessed online. We employed data from the World Inequality Report (WIR), the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s (GEM) TEA rate, as well as the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom score of South Africa. The authors agree to make their datasets and materials supporting the results or analyses presented in this article available upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mathew E. Egu

Mathew E. Egu (Ph.D., University of South Africa) is a Professor of Business Administration and Finance at the Global Humanistic University, Anguilla, and he is also a Lecturer and DBL Supervisor at the Federal Polytechnic Idah, Kogi State, Nigeria, and the Graduate School of Business Leadership (SBL), University of South Africa, Midrand, South Africa, respectively. Furthermore, he is the managing editor of the Journal of Management and Technology and also a member of the editorial board of the International Journal of Entrepreneurship. He holds the Chartered Institute for Business Accountants’ (formerly SAIBA) Certified Financial Officer - CFO (SA) highest designation and has served meritoriously as an ESG Committee member. He was recently a visiting professor at the Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia. His research focuses on international business, entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial financing, strategy, and small business development.

Evelyn G. Chiloane-Tsoka

Evelyn G. Chiloane-Tsoka is a Professor of Entrepreneurship at the Department of Applied Management, School of Management Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa where she is the Entrepreneurship M&D Coordinator (Research). She received her DCom in Entrepreneurship from the University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. Furthermore, she has supervised numerous master’s and doctoral students to completion. Her research has been published widely across the world and is a recipient of several awards.

References

- Acs, Z. J., Lafuente, E., & Szerb, L. (2023). The entrepreneurial ecosystem: A global perspective. Palgrave studies in entrepreneurship and society. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Agba, A. M. O., Akpanudoedehe, J. J., & Ocheni, S. (2014). Financing poverty reduction programs in rural areas of Nigeria: The role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). International Journal of Democratic and Development Studies (IJDDS), 2(1), 1–16.

- Bastagli, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., Harman, L., Barca, V., Sturge, G., & Schmidt, T. (2019). The impact of cash transfers: A review of the evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Social Policy, 48(3), 569–594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000715

- Berry, A., von Blottnitz, M., Cassim, R., Kesper, A., Rajaratnam, B., & van Seventer, D. E. (2002). The economics of SMMEs in South Africa. Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS).

- Bill of Rights. (1996, December 18). Bill of Rights: Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. No. 108 of 1996. Statutes of the Republic of South Africa-Constitutional Law, The Government of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf

- Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. (2017). Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9), 1045–1064. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0102-z

- Chalera, C. S. (2006). [An impact analysis of South Africa’s national strategy for the development and promotion of SMMEs] [Doctoral thesis, University of Pretoria Pretoria]. UPSpace Institutional Repository. https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/24279/Complete.pdf?sequence=7&isAllowed=y

- Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2022). World Inequality Report 2022. World Inequality Lab. wir2022.wid.world

- Children’s Act. (2005, December 9). No. 38 of 2005: Children’s Act, 2005. Volume 492 (28944). The Judiciary, The Government of South Africa. http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/2005-038%20childrensact.pdf

- Deakins, D., & Freel, M. (2012). Entrepreneurship and small firms (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- DSBD. (2016). Annual report: Small business is big business. Department of Small Business Development.

- Egu, E. M., & Aregbeshola, R. A. (2017). The odyssey of South African multinational corporations (MNCs) and their impact on the Southern African development community (SADC). African Journal of Business Management, 11(23), 686–703. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2017.7742

- Egu, M. E. (2022). [The impact of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s Alternative Exchange on listed firm’s performance and entrepreneurship]. [Doctoral thesis, University of South Africa]. Unisa Institutional Repository. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/28839/thesis_egu_me.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Egu, M. E., & Aregbeshola, R. A. (2016, June 29). The odyssey of South African MNCs and their impact on the SADC [Paper presentation]. Academy of International Business (AIB) Annual Conference, New Orleans, USA.

- Egu, M. E., & Chiloane-Tsoka, E. G. (2023). Does listing on the JSE’s AltX improve the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises? Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2282750. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2282750

- Egu, M. E., Chiloane-Tsoka, E., & Dhlamini, S. (2016, August 19). South African entrepreneurial chasms and its determinant outcome [Paper presentation]. Academy of International Business (AIB) Sub-Saharan Chapter Conference, hosted by Lagos Business School (LBS), Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Egu, M. E., Chiloane-Tsoka, E., & Dhlamini, S. (2017, July 3). African entrepreneurial viewpoints versus macroeconomic outcomes [Paper presentation]. Academy of International Business (AIB) Annual Conference, Dubai, UAE.

- European Commission. (2014, December 5). What is an SME? Enterprise and industry. European Commission. https://web.archive.org/web/20150208090338/http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/sme-definition/index_en.htm

- EViews. (2022, December 14). Stability diagnostics. EViews. https://eviews.com/help/helpintro.html#page/content/testing-Stability_Diagnostics.html

- Fin24. (2015, May 4). CALCULATOR: See how many SMEs SA needs to create 11m jobs. Fin24. http://www.fin24.com/Entrepreneurs/Resources/CALCULATOR-See-how-many-SMEs-SA-needs-to-create-11m-jobs-20150504

- Fiszbein, A., & Schady, N. (2009). Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty. A World Bank policy research report. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- Freeland, N. (2007). Superfluous, pernicious, atrocious and abominable? The case against conditional cash transfers. IDS Bulletin, 38(3), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00382.x

- Freund, B. (2010). Development dilemmas (pp. 327, 332, 335, 336). University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- GEM. (2023). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2023/2024 global report: 25 years and growing. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM).

- Hatemi, J. A. (2008). Tests for cointegration with two unknown regime shifts with an application to financial market integration. Empirical Economics, 35(3), 497–505.

- Heritage Foundation. (2023). 2023 Index of economic freedom. The Heritage Foundation.

- Herrington, M., & Kelly, D. (2012). African entrepreneurship: Sub-Saharan African regional report. Global entrepreneurship monitor South Africa 2012 report. University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business.

- Herrington, M., Kew, P., & Mwanga, A. (2017). South Africa report 2016/2017: Can small businesses survive in South Africa? Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Iftikhar, M. N., Ahmad, M., & Audretsch, D. B. (2020). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship: The developing country context. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(4), 1327–1346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00667-w

- Kushnir, K., Mirmulstein, M. L., & Ramalho, R. (2010). Micro, small, and medium enterprises around the world: How many are there, and what affects the count? Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, MSME Country Indicators, The World Bank/IFC.

- Lien, T. T. H. (2024). Corporate governance and stakeholders’ wealth in ASEAN listed companies: From creation to redistribution. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 16(2), 170–188.

- Lierse, H., Lascombes, D. K., & Becker, B. (2022). Caught in the middle! Wealth inequality and conflict over redistribution. Social Justice Research, 35(4), 436–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-021-00384-x

- Musabayana, G. T., Mutambara, E., & Ngwenya, T. (2022). An empirical assessment of how the government policies influenced the performance of the SMEs in Zimbabwe. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00192-2

- National Credit Regulator. (2011). Literature review on small and medium enterprises’ access to credit and support in South Africa. Underhill Corporate Solutions (UCES).

- National Treasury. (2023). Budget 2023 - Budget review. National treasury, estimates of national expenditure, 2023. National Treasury, The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- NHFC. (2016). Integrated report. National Housing Finance Corporation (NHFC).

- Non-Profit Organisation’s Act. (1997, December 3). No. 71 of 1997: Nonprofit Organizations Act, 1997. Volume 390 (18487). Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a71-97.pdf

- NPC. (2012). National Development Plan 2030. Our future - make it work. Executive summary. National Planning Commission, The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- OECD. (2006). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs. OECD policy brief. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

- Older Persons Act. (2006, November 2). No. 13 of 2006: Older Persons Act, 2006. Volume 497 (29346). Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a13-062.pdf

- Oparah, C. (2023, November 13). Role of entrepreneurship on wealth creation in Nigeria. Info Guide Nigeria. https://infoguidenigeria.com/role-entrepreneurship-wealth-creation-nigeria/

- Prevention of and Treatment for Substance Abuse Act. (2008, December 18). No. 70 of 2008: Prevention of and Treatment for Substance Abuse Act, 2008. Volume 526 (32150). Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/70of2008ocr.pdf

- Saavedra, J. E. (2016, June 2). The effects of conditional cash transfer programs on poverty reduction, human capital accumulation and wellbeing. Paper presented at the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Strategies for Eradicating Poverty to Achieve Sustainable Development for All, New York, USA.

- SEBRAE. (2012, February 1). Introduction to SEBRAE. Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas. The Brazil Business. https://thebrazilbusiness.com/article/introduction-to-sebrae

- SME Growth Index. (2015, October 10). SME sustainability and growth should be an obsession for job creation in South Africa. http://smegrowthindex.co.za/

- Social Assistance Act. (2004, June 10). No. 13 of 2004: Social Assistance Act, 2004. Volume 714 (26446). Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a13-040.pdf

- Social Services Professionals Act. (1978, June 30). No. 110 of 1978: Social Services Professionals Act, 1978. Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201504/act-110-1978.pdf

- Sustainable Development. (2015, May 9). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations – Development knowledge platform. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- Sy, A. (2014, January 30). Jobless growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa in focus. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/jobless-growth-in-sub-saharan-africa/

- The Economist. (2015, March 26). The 169 commandments - The proposed sustainable development goals would be worse than useless. Development. The Economist Newspapers Limited. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/03/26/the-169-commandments

- The Human Rights Commission Act. (1994, November 23). The Human Rights Commission Act 54 of 1994. Department of Justice and Constitutional Development. Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/1994-054.pdf

- The National Small Business Amendment Act. (2004, December 15). Department of Trade and Industry. Government Gazette, The Republic of South Africa. http://www.dsbd.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislation/national-small-busniess-amendment-act2004.pdf

- The Treasury. (2017, February 25). Government spending plans. Extract from the 2017 budget review. The budget review. The Treasury, Republic of South Africa. https://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2017/review/BR4.%20Spending%20plans.pdf

- UNICEF South Africa. (2017). Social development budget South Africa 2017/2018 - Brief. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

- United Nations. (2018, March 10). Global issues overview. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/

- UNOWA. (2005). Youth unemployment and regional insecurity in West Africa. United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA).

- Velicer, W. F. (1976). Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika, 41(3), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02293557

- Woodward, W. A., Gray, H. L., & Elliott, A. C. (2012). Applied time series analysis. CRC Press.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. (5th International ed.). Cengage Learning.

- World Bank Group. (2014, November 1). South Africa economic update: Fiscal policy and redistribution in an unequal society. The World Bank Group. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/publication/south-africa-economic-update-fiscal-policy-redistribution-unequal-society

- World Inequality Report. (2018). World inequality report 2018. World Inequality Lab.

- World Investment Report. (2018). World investment report 2018: Investment and new industrial policies. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), United Nations Publications.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table A2. Pairwise Granger causality (2 lags) test.