Abstract

This study explores conflicts stemming from the intersection of cultural practices, beliefs, and international human rights standards within coastal communities. Through rigorous focus group discussions, it examines the interplay between culture and human rights, identifying colonial legacies, economic disparities, and environmental challenges as primary sources of tension. Concrete examples, such as disputes over fishing access and clashes with regulatory frameworks, underscore the pressing need for resolution. Emphasising the importance of inclusive approaches, the study advocates for strategies that honour cultural diversity while upholding universal human rights principles. It calls for comprehensive measures, including community dialogue, cultural sensitivity training, and the integration of customary laws, alongside education and awareness initiatives and effective policy implementation. Additionally, the study recommends the establishment of robust mediation mechanisms and partnerships with local and international stakeholders to facilitate conflict resolution and capacity-building efforts. Through collaborative efforts with coastal communities, these actions pave the way for a more equitable, inclusive, and rights-respecting future.

Impact Statement

This study investigates the challenges confronting coastal communities due to clashes between their traditions, human rights, and global standards. By talking to people in these communities, it was learned how history, money, and the environment all play a part in these conflicts. For example, some fights break out over who gets to fish where, or when rules clash with old customs. It is believed that everyone’s voice should be heard, and a call is going out for solutions that respect everyone’s traditions while also making sure everyone’s rights are protected. The study is suggesting things like talking openly, teaching people about different cultures, and making sure everyone knows their rights. By working together with the communities, a future can be created where everyone is treated fairly and with respect.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

By definition, cultural practices encompass the traditions, rituals, customs, and behaviours passed down through generations within a particular community. These practices shape the social, economic, and environmental dynamics of the community and contribute to its identity and cohesion. In the context of Ghanaian coastal communities, cultural practices are deeply intertwined with fishing livelihoods and marine conservation efforts. For example, fishing rituals, such as offering prayers to ancestral spirits before setting sail, demonstrate the spiritual connection between fishermen and the sea. These traditions not only provide a sense of identity and purpose but also reinforce sustainable fishing practices and environmental stewardship.

However, cultural practices in Ghanaian coastal communities also intersect with issues of gender equality and resource management. Traditional gender roles may limit women’s participation in fishing activities, despite their significant contributions to the household economy. Moreover, customary laws and taboos related to land and marine resource use may influence access rights and conflict resolution processes within the community. In essence, cultural practices in Ghanaian coastal communities are both a source of resilience and a potential challenge to sustainable development. Recognizing and respecting these practices are crucial for promoting inclusive and equitable approaches to marine resource management and community development.

Coastal communities are renowned for their rich cultural diversity and ecological significance. The Census of Marine Life (Citation2010) has revealed that the ocean is a vital reservoir of global biodiversity, hosting over 90 percent of habitable space on Earth and approximately 250,000 known species, with many more yet to be discovered (Census of Marine Life, Citation2010). Remarkably, at least two-thirds of marine species remain unidentified. Over generations, coastal communities have developed unique cultural practices and beliefs that have sustained their way of life. However, the rapid forces of globalization and climate change have increasingly threatened these communities, jeopardizing their cultural heritage and traditional lifestyles (Small & Cohen, Citation2004). These changes have also had significant impacts on the human rights of individuals within these communities (Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023, Golo et al., Citation2022).

Existing studies have demonstrated that cultural practices and beliefs can have both positive and negative effects on the livelihoods of coastal communities (Mohammed et al., Citation2023). On one hand, these practices, such as traditional fishing methods and seasonal crop cultivation, have allowed communities to adapt to evolving environmental conditions and ensure sustenance for their members. However, these practices can also perpetuate inequality, as they may exclude certain individuals based on factors such as gender, age, or ethnicity (Mekonnen et al., Citation2022).

Simultaneously, concerns have arisen regarding the impact of cultural practices and beliefs on the human rights of individuals within coastal communities. For instance, traditional gender role expectations may restrict women’s access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Similarly, entrenched beliefs regarding gender or caste may perpetuate discrimination and hinder individuals from enjoying basic human rights, including access to education, healthcare, and clean water (Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023; Golo et al., Citation2022; Dosu, Citation2017).

Globally, indigenous coastal communities face challenges in balancing cultural practices with human rights. For example, the construction of large-scale tourism resorts may disrupt traditional fishing grounds and sacred sites, infringing upon indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination and cultural preservation (Devine, Citation2017; Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017). In Pacific Island nations, traditional cultural practices such as taboos or restrictions on fishing in certain areas are often disregarded in favour of commercial fishing interests. This can lead to conflicts between indigenous communities, who rely on sustainable fishing practices for their livelihoods, and large-scale fishing enterprises, which prioritize profit over environmental conservation and indigenous rights (Lalancette & Mulrennan, Citation2022)

In Ghana and other West African coastal communities, traditional beliefs about marine spirits or deities does influence fishing practices and resource management decisions. Conflicts may arise when conservation initiatives, such as marine protected areas, clash with traditional beliefs or customary fishing rights. Balancing cultural preservation with environmental conservation efforts requires engaging with local communities to understand and respect their cultural practices while promoting sustainable resource management (Adjei & Sika-Bright, Citation2019). In Ghana’s coastal communities, traditional fishing practices often exclude women from participating in fishing activities, limiting their economic opportunities and access to resources. This perpetuates gender inequality and violates women’s rights to economic participation and livelihood security (Adjei & Sika-Bright, Citation2019; Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023; Torell et al., Citation2019).

Also, in Ghana, traditional beliefs and practices often intersect with human rights issues in coastal communities. For example, some traditional fishing communities in Ghana practice "trokosi", a system where young girls are offered to shrines as "wives" to atone for alleged family sins. This practice has been criticized for violating the girls’ rights to education, freedom from slavery, and protection from sexual exploitation (Gillard, Citation2010). Additionally, in Ghana’s coastal regions, there are instances where cultural practices clash with environmental conservation efforts. For instance, the practice of "saiko" fishing, where industrial trawlers illegally transfer fish to artisanal canoes at sea, violates both traditional fishing norms and international regulations. This practice not only threatens marine biodiversity but also undermines the livelihoods of small-scale fishers, exacerbating poverty and social inequality (EJF, Citation2021).

These case examples highlight the complex interactions between cultural practices, human rights, and environmental sustainability in Ghanaian coastal communities, underscoring the importance of addressing these issues through collaborative and culturally sensitive approaches. To mediate conflicts between cultural practices and human rights in coastal communities, it is essential to adopt a multi-dimensional approach that considers the cultural, social, economic, and environmental contexts. Concrete strategies can be implemented to foster dialogue, understanding, and reconciliation.

A case example of where Community Dialogue and Consultation had taken place in Ghana is the project in which the Coastal Resources Centre (CRC) at the University of Rhode Island, in collaboration with local NGOs and government agencies, in Ghana and other West African Countries implemented a Community-Based Coastal Resources Management named “The Estuarine and Mangrove Ecosystem-Based Shellfisheries and Food Security Project” in several coastal communities in Ghana. The project organized regular community dialogues and participatory decision-making processes to discuss issues related to fisheries management, marine conservation, and sustainable livelihoods. Through these dialogues, community members were able to voice their concerns, shared traditional knowledge, and contributed to the development of locally-driven solutions (Chuku et al., Citation2021).

The West African Coastal Areas Management Program with support from the World Bank has based developed a cultural sensitivity training program for fisheries management officials and conservation practitioners working in coastal areas across West Africa including Ghana and Senegal. The programme includes modules on understanding local cultural practices, beliefs, and customary laws related to fisheries management. Participants learn how to integrate cultural considerations into their work, engage effectively with coastal communities, and promote collaborative decision-making processes. The training has helped improve relationships between authorities and communities, leading to more effective conservation initiatives and greater respect for human rights (World Bank, Citation2020).

Similarly, The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of Ghana, with support from the World Bank and the Government of Ghana and in collaboration with traditional authorities and civil society organizations, established community-based mediation committees in coastal areas affected by conflicts over land and resource rights. These committees comprise respected community members trained in mediation and conflict resolution techniques. They facilitated dialogue between conflicting parties, helped identify mutually acceptable solutions, and monitored implementation of agreements. The mediation committees have successfully resolved numerous disputes related to land tenure, resource allocation, and environmental management, contributing to peace and stability in coastal communities (World Bank, Citation2020).

Likewise, the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (MFAD) of Ghana with the support of the World Bank and the Ghana Government collaborated with traditional leaders and local fisherfolk to develop a co-management framework for the management of small-scale fisheries along the coast. The framework integrates customary laws and traditional governance structures into existing fisheries management regulations, recognizing the role of traditional authorities in enforcing rules and resolving disputes. By incorporating local knowledge and practices, the co-management approach has enhanced compliance with regulations, reduced conflicts, and improved the sustainability of fisheries resources (World Bank, Citation2020).

These examples demonstrate the effectiveness of implementing strategies such as community dialogue, cultural sensitivity training, mediation, and customary law integration in addressing conflicts and promoting sustainable development in coastal communities in Ghana and West Africa. By engaging local stakeholders, respecting cultural diversity, and building capacity at the community level, these initiatives have fostered resilience, equity, and social cohesion in coastal areas.

This study addresses gaps in understanding how to balance cultural beliefs with human rights and sustainable fishing. It examines how cultural practices in coastal communities’ impact livelihoods and human rights. The study’s goal is to uncover conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards, and propose ways to reconcile them. Key research questions include identifying conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards, finding ways to harmonize them in coastal communities, and analyzing the benefits and challenges of preserving culture while protecting human rights. The study aims to:

Investigate conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards.

Develop strategies to reconcile cultural practices with human rights protection.

Assess potential benefits and challenges of promoting cultural preservation alongside human rights protection in coastal communities.

Literature review

Coastal communities in Ghana

In the coastal communities of Ghana, religion plays a significant role in shaping cultural practices and beliefs. While Christianity is the predominant religion, with a majority of the population identifying as Christian, there is also a significant presence of traditional African religions and Islam. This religious diversity contributes to a rich tapestry of rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations that reflect both local traditions and global influences.

Within Ghanaian coastal communities, cultural practices are deeply rooted in both religious and secular contexts. Traditional rituals and ceremonies, such as the annual Homowo festival celebrated by the Ga people in Accra, or the Ada Asafotufiam festival of the Ada people, the Aboakyer festival - Winneba, Akwanbo Festival - Gomoa Abora, Central Region, Bakatue Festival – Fish Harvest -Elmina, Central Region and Oguaa Fetu Afahye festival - Cape Coast, which is celebrated, every year in the first week of September, in the Central region of Ghana. All these festivals, honor ancestral spirits and commemorate historical events. These ceremonies often involve drumming, dancing, and feasting, serving as occasions for community bonding and spiritual renewal (Nukunya, Citation1992).

At the same time, there are various taboos, beliefs, and superstitions that shape everyday life in these communities. For example, fishermen may observe certain rituals or make offerings to appease the spirits of the sea for a bountiful catch and safe return. Additionally, there may be taboos against certain fishing practices or harvesting of marine resources during specific times of the year, based on traditional calendars or lunar cycles.

The interplay between religious beliefs, cultural practices, and human rights is complex and multifaceted. While cultural traditions and religious beliefs contribute to the cultural identity and social cohesion of coastal communities, they can also intersect with issues related to gender equality, freedom of expression, and access to resources. For instance, traditional gender roles may limit women’s participation in decision-making processes or economic activities, thereby infringing upon their rights to equality and empowerment (Adjei & Sika-Bright, Citation2019).

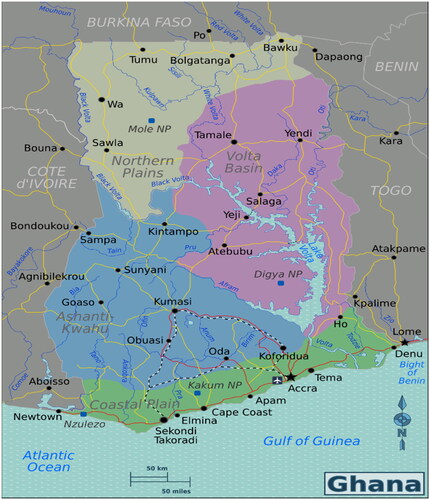

In addressing these challenges, it is essential to recognize the importance of cultural diversity and religious pluralism while upholding universal human rights principles. By promoting dialogue, understanding, and respect for diverse beliefs and practices, coastal communities can work towards a more inclusive and equitable society where cultural preservation and human rights protection go hand in hand. shows a map of the Ghanaian Coastal Communities. This holistic approach acknowledges the interconnectedness of cultural, religious, and human rights dimensions in coastal communities, offering a framework for sustainable development and social justice along Ghana’s picturesque coastline.

Women’s rights and gender equality

The interplay of cultural practices, beliefs, and gender significantly impacts women’s rights and gender equality within coastal communities, shaping perceptions, values, and treatment of women, often leading to discrimination and human rights violations (Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020; Adomako-Ampofo, Citation1993). Cultural norms tend to reinforce gender roles and stereotypes, limiting women’s opportunities and autonomy (Adomako Ampofo & Boateng, Citation2007), with women primarily expected to fulfill domestic roles, hindering their access to education, employment, and decision-making positions (Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023; Golo et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, harmful practices like female genital mutilation and child marriage adversely affect women’s health and well-being (Khosla et al., Citation2017).

The prevailing patriarchal norms in Ghanaian coastal communities contribute to the devaluation of women, perpetuating power imbalances and discrimination (Adomako Ampofo & Boateng, Citation2007; Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023; Golo et al., Citation2022). Gender-based violence is prevalent, further exacerbated by cultural acceptance, compounding the challenges faced by women (Adomoko-Ampofo, Citation1993; Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020).

Efforts to promote gender equality in coastal communities must acknowledge and engage with local cultures and beliefs, fostering collaborative approaches to cultivate more inclusive and equitable cultural practices that recognize and uphold women’s rights and contributions (Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020). Cultural practices, beliefs, and gender dynamics are pivotal in shaping women’s rights and gender equality in coastal settings (Asante et al., Citation2017; Holly et al., Citation2022; Karakara et al., Citation2022; Lawless et al., Citation2019), emphasizing the importance of culturally sensitive interventions to advance gender equity.

Community participation and decision-making

Community participation and decision-making play pivotal roles in shaping the success and sustainability of policies and programs impacting coastal communities (Mukhtarova, 2023). Engaging local communities in decision-making processes ensures alignment with their needs and priorities, fostering culturally appropriate and enduring initiatives (Agarwal, Citation2001; Cinner et al., Citation2012). This inclusive approach not only enhances compliance with regulations and support for conservation efforts (Cinner et al., Citation2012) but also facilitates improved resource management and increased community income (Agarwal, Citation2001).

Participatory approaches cultivate trust between communities, governmental agencies, and NGOs, fostering positive and productive relationships (Hügel & Davies, Citation2020). When local stakeholders are involved, they take ownership of the processes, while external actors demonstrate commitment to addressing local concerns (Hügel & Davies, Citation2020). Globally, initiatives like the community-based fisheries management program have demonstrated success by empowering communities in decision-making and resource management, leading to enhanced fish stocks, livelihoods, and social cohesion (Baker, Citation2021; Cinner et al., Citation2012; Johnson et al., Citation2021; Kleiber, Citation2019).

Community participation and decision-making are indispensable for the development and implementation of policies and programmes affecting coastal communities, ensuring their success, sustainability, and cultural appropriateness, while fostering improved livelihoods, social cohesion, and effective resource management.

Coastal communities, environment, culture, rights

Climate change has profound implications for environmental degradation, cultural practices, beliefs, and human rights in coastal communities worldwide (Agodzo et al., Citation2023; Nicholls et al., Citation2007; Nolan et al., Citation2022). Rising sea levels and coastal erosion threaten cultural sites and essential areas for fishing, navigation, and ceremonial events (Nicholls et al., Citation2007). Changes in rainfall patterns affect traditional beliefs and practices related to water management (Agodzo et al., Citation2023), while deforestation and mangrove degradation negatively impact the livelihoods of coastal communities (Nunoo & Agyekumhene, Citation2022). Moreover, increased frequency and intensity of natural disasters exacerbate gender inequalities and threaten the safety of women and children (Md et al., Citation2022), undermining both cultural and economic rights (Persoon & Minter, Citation2020).

In Ghana, Nolan et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate through a double exposure vulnerability framework that frontier expansion and climatic change exacerbate food, water, and livelihood insecurities while reducing adaptive capacity and perpetuating harmful global changes. Collectively, these findings highlight the severe and enduring impacts of climate change and environmental degradation on coastal communities, particularly affecting vulnerable groups (Persoon & Minter, Citation2020). Policymakers and practitioners must consider these effects when devising strategies to address environmental degradation in coastal areas.

Methodology

The study sites and design

The study was carried out in four communities in the Central and Western Regions of Ghana, namely Apam, Elmina, Takoradi and Axim using focus group discussions, and critical observations. , shows study areas. A qualitative study involving purposively sampled adult men, women, youth, community people and other actors and stakeholders with stake in fishing business and management of the coastal environment was carried out. In this study, the focus was on the coastal communities in the Central and Western Regions of Ghana namely Apam, Elmina, Takoradi and Axim using focus group discussions.

Study design

The study adopted an exploratory design within the qualitative framework (Adjei & Sika-Bright, Citation2019; Creswell, Citation2003).

Sample and sampling technique

The population of stakeholders in the four coastal communities is estimated to be in excess of 10,000. However, four focus group discussions were carried out, one in each coastal community with 12 members in the FGD. Out of the 12 participants taking part in the focus group discussion, 2 were randomly selected for an in-depth interview. A sample of 56 respondents (48 respondents taking part in focus group discussion and 8 taking part in in-depth interviews) were engaged for this study. Aside from the FGD and the in-depth interviews, the investigation team engaged in critical observations of the coastal environments and the community and surroundings to gain first-hand information and appreciation of the problems under investigation.

Selecting participants for the focus group discussions

To ensure comprehensive representation and meaningful participation in the focus group discussions in each of the four communities under investigation, the selection of the 12 stakeholders was carried out through a participatory and inclusive process. The research team begun by identifying key categories of stakeholders listed for each community, including representatives from the District Assembly, NGOs, civil society organizations, community leaders, fisherfolk, youth groups, and other relevant community members. Community meetings and consultations were organized to inform residents about the purpose and importance of the focus group discussions and inputs were sought from community members on which stakeholders they believe should be represented in the discussions and why.

A matrix was created to map out the roles and influence of different stakeholders within each community. Factors such as expertise, leadership positions, representation of marginalized groups, and relevance to the topic of discussion were used to prioritise participants. Diversity and balanced representation across gender, age, occupation, and social status were ensured among the selected stakeholders. Inclusion of marginalized and underrepresented groups, as female community members, youth leaders, and traditional leaders was prioritized.

The research team engaged with community leaders, including chiefs and elders, to seek their inputs and guidance on selecting stakeholders who can effectively represent the interests and perspectives of the community as a whole. Random sampling and stratification techniques were used to select stakeholders from each category, ensuring fairness and transparency in the selection process. Stratifying the sample ensured proportional representation across different segments of the community. The research team, maintained transparency throughout the selection process by openly communicating the criteria and rationale for selecting stakeholders.

Feedback and input from community members were encouraged to enhance accountability and legitimacy. Based on the inputs received and the criteria established, the selection of 12 participants from each community was finalised, ensuring that the chosen individuals collectively represent the diversity of perspectives and interests within the community (). By following the above steps and engaging in such collaborative and inclusive selection process, the focus group discussions effectively captured a wide range of viewpoints, and promoted meaningful dialogue, and this contributed to informed decision-making and community empowerment in each of the four coastal communities studied in Ghana.

Table 1. Selection criteria for FGD participants by their categories per community and gender.

Data collection and analysis

Before each of the focus group discussions took place, the respondents were briefed about the study and the question guide focusing on the objectives of this study were explained to them and were encouraged to offer their honest opinions and thoughts. Respondents for the focus group discussion were drawn from across the four coastal communities mentioned for the study. The in-depth interviews employed question guides developed on the basis of findings from the focus group discussion about the objectives of the study. Respondents’ consents were sought to take part in the focus group discussion and in-depth interviews and additionally handwritten notes were taken by two research assistants.

The focus group guide and interview guide supplied reliable and comparable qualitative databases. The in-depth interviews as well as the focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed. They were cleaned up to remove errors and inconsistencies so as to supply accurate and the correct views of respondents. The transcribed data were analyzed thematically using the ATLAS.ti software. The software, allowed for the interrogation of the data at particular levels which in turn improved quality of the analysis process by confirming the impressions held by the researchers on the data and from the literature’s secondary studies.

Notable issues that were up for discussion among others were the issues exploring conflicts between cultural practices, beliefs, and international human rights standards in coastal communities and the intersection of culture and human rights and livelihoods in the coastal communities.

Ethics

In line with ethical standards, the participants got information about the nature of the research and their written consent obtained and achieved prior to the commencement of the study. Participation in this study was voluntary and the participants had the choice to withdraw at any stage of the study. Participants got assurance of anonymity. Coding was used to ensure that respondents’ identities and the names of their communities were concealed during analysis of the data.+

Results

This section provides a qualitative explanation on the clash between cultural practices and beliefs, and established international human rights standards within Ghana’s small-scale fisheries. Although, data were collected from focus group discussion, in-depth interviews and critical observations of the communities being studied, the results presented in this paper are those based only on the responses, experiences and comments and views expressed during the focus group discussion.

The transcribed data were coded and analysed with the support of ATLAS.ti software, a qualitative data analysis computer software for coding, storage, indexing and retrieval. Five (5) major themes and (8) sub-themes guided the analysis ().

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes generated from the qualitative data.

Cultural practices and environmental impact

Responses show that, traditional rituals and practices in Ghanaian coastal communities, such as offering prayers before fishing expeditions, have both positive and negative effects on the environment. While they reinforce sustainable fishing practices and environmental stewardship, concerns arise about the potential environmental impact, including the use of harmful substances at sea.

Ritualistic practices at sea

Ritualistic practices involving the use of dynamite and harmful substances at sea were commonly reported among respondents. These practices, deeply rooted in cultural beliefs, are performed as offerings to sea deities in exchange for abundant fish harvests. Respondents recounted instances where fishers, seeking bountiful catches, would engage in these rituals, often resulting in environmental degradation and violations of human rights.

A respondent shared a personal experience, stating:

"I went to give mine food about two months ago. The god is called Nana Waka. After doing that, we caught fish. But fishers used dynamite and all the fishes went away."

Discrimination and gender inequality

Respondents confirms that, traditional gender roles often exclude women from participating in fishing activities, despite their significant contributions to the household economy. Such discriminatory practices and entrenched beliefs perpetuate gender inequality and hinder access to resources and opportunities for marginalized groups within these communities.

Impact on women and girls

Discriminatory cultural practices were found to disproportionately affect women and girls within coastal communities. Traditional gender roles and expectations limited their access to education, employment, and decision-making opportunities. Respondents highlighted instances where women were excluded from fishing activities and faced barriers to economic empowerment. A respondent explained, underscoring the entrenched nature of these practices.

Women are not allowed to join us when we go to offer sacrifices at sea. It’s our tradition,

Such practices violate fundamental human rights, including the right to equality and non-discrimination, as outlined in international human rights instruments.

Use of children in fishing

Cultural norms accepting the employment of boy children in fishing activities were prevalent among respondents. These children, often from marginalized backgrounds, are engaged as support workers on fishing vessels, exposing them to hazardous working conditions and depriving them of educational opportunities.

We use young boys to help with the fishing. It’s our way,

The use of children in fishing activities violates their rights to education, consent, and protection from exploitation, contravening international human rights standards.

Legal and policy reforms

The respondents in the study show that rapid changes driven by globalization and climate change necessitate legal and policy reforms to balance cultural preservation with environmental conservation and human rights protection. Integrating customary laws into fisheries management regulations and engaging in collaborative approaches, such as mediation, are shown to be essential for addressing conflicts and promoting sustainable development.

Role of legal reforms

Respondents identified the importance of legal and policy reforms in challenging discriminatory cultural practices and promoting human rights. Legal protections are crucial in ensuring accountability and upholding individuals’ rights within coastal communities.

We need stronger laws to protect our rights,

Effective legal frameworks are essential in aligning cultural practices with human rights standards as recognized by international agreements.

Strategies for reconciliation

The study reveals that, addressing conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards requires culturally sensitive approaches, including community dialogue and cultural sensitivity training. These strategies according to respondents would facilitate reconciliation and foster resilience, equity, and social cohesion in coastal communities.

Dialogue and engagement

Promoting dialogue and engagement between diverse cultural groups emerged as a key strategy for reconciling cultural practices with human rights. Open discussions facilitate understanding and respect for differing perspectives, fostering a collaborative approach to addressing conflicts.

We need to talk more, and understand each other,

Meaningful dialogue is essential in promoting mutual respect and finding common grounds between cultural traditions and human rights principles.

Education and awareness raising

Education and awareness-raising initiatives were recognized as effective tools in challenging harmful cultural practices and promoting human rights. Targeted programmes can empower community members with knowledge and resources to advocate for their rights and challenge discriminatory norms.

People need to understand the consequences of their actions,

By promoting education and awareness, communities can challenge entrenched beliefs and foster a culture of respect for human rights.

Empowerment of women and marginalized groups

Empowering women and marginalized groups emerged as a crucial strategy in promoting human rights and challenging discriminatory practices. Access to education, training, and resources can enhance socio-economic opportunities and foster greater inclusion in decision-making processes.

We need to support women and give them opportunities,

Empowerment initiatives are essential in addressing structural inequalities and promoting greater social justice within coastal communities.

Cultural adaptation

Respondents in the study are of the view that, initiatives such as community-based coastal resources management projects and the integration of traditional governance structures into fisheries management regulations demonstrate successful cultural adaptation strategies. Thus, by engaging local stakeholders and building capacity at the community level, these initiatives promote sustainable development while respecting cultural diversity.

Adapting cultural practices

Adapting cultural practices and beliefs to align with human rights and environmental sustainability was identified as a necessary step in promoting reconciliation. By reimagining traditional practices and embracing innovative solutions, communities can preserve cultural heritage while upholding fundamental rights.

We can find new ways to honour our traditions without harming the environment,

Cultural adaptation requires a proactive approach to finding common ground between tradition and progress, guided by principles of respect.

Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the intricate interplay between cultural practices, beliefs, and international human rights standards within Ghana’s coastal communities, revealing the existence of conflicts that challenge the harmonious coexistence of tradition and human rights (Golo & Erinosho, Citation2023; Golo et al., Citation2022). These conflicts arise when cultural rituals and practices intersect with fundamental human rights, necessitating a delicate balance between preserving cultural heritage and upholding individual dignity and rights. Hence, a nuanced approach that acknowledges and respects both cultural diversity and universal human rights principles is imperative.

Preserving cultural heritage alongside safeguarding human rights in coastal communities offers both benefits and challenges. On one hand, cultural preservation enriches societal diversity and fosters community cohesion by maintaining unique identities, traditions, and knowledge systems (Bita & Forsythe, Citation2021; Goudineau, Citation2003). Moreover, certain cultural practices are intricately linked to sustainable resource management and conservation, contributing to long-term environmental viability and community resilience (Adjei & Sika-Bright, Citation2019; Asante et al., Citation2017; Karakara et al., Citation2022; Ng’ang’a et al., Citation2022).

However, challenges arise when cultural practices conflict with human rights standards, particularly regarding gender inequality and discriminatory norms (Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020). Achieving gender equality within cultural preservation efforts necessitates confronting deeply ingrained beliefs and traditions, highlighting the complexity of balancing cultural heritage with human rights principles.

Furthermore, external influences such as globalization, tourism, and development projects impact cultural practices and beliefs in coastal communities, posing additional challenges to reconciling cultural preservation with human rights protection (United Nations Mission in Liberia/United Nations Human Rights, Citation2015). Negotiating these influences while upholding universal human rights principles requires adaptability and resilience from coastal communities.

In essence, reconciling conflicts between cultural beliefs and human rights standards in Ghanaian coastal communities demands a multifaceted approach that respects cultural autonomy while ensuring sustainable fishing practices and upholding universal human rights principles. This entails addressing conflicts, adapting cultural practices, confronting gender inequalities, and navigating external influences with a steadfast commitment to promoting human dignity and social justice.

Conclusion

The study has examined the intricate conflicts arising from the intersection of cultural practices, beliefs, and international human rights standards within coastal communities. Through this examination, significant tensions between these elements have been brought to light, underscoring the complex dynamics at play.

The discussion has thoroughly explored the implications and hurdles associated with reconciling cultural preservation with human rights protection, emphasizing the imperative of striking a delicate balance. This balance demands the promotion of human rights education and the facilitation of dialogue aimed at addressing harmful practices while preserving cultural identity and traditions. Engaging coastal communities actively in this reconciliation process is paramount for resolving conflicts and fostering a sense of resolution regarding human rights issues (Mekonnen et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, the collaboration among communities, policymakers, and human rights entities is indispensable for navigating conflicts and devising sustainable solutions that benefit all stakeholders (DESA, Citation2009). In Ghana’s coastal regions, addressing conflicts necessitates a tailored approach that embraces dialogue, education, and community involvement to craft solutions that honour both cultural preservation and human rights.

Through the promotion of dialogue, education, and community engagement, coastal communities can navigate towards harmonizing cultural practices, beliefs, and human rights standards. Achieving this balance will not only preserve cultural heritage but also uphold the dignity of coastal community members and their traditional leadership, even amidst the challenges posed by environmental issues such as sanitation (Ng’ang’a et al., Citation2022).

Theoretical and policy implications

The conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards in coastal communities reveal underlying power dynamics and social hierarchies within societies. To gain a clearer understanding of the barriers to change and develop strategies for promoting cultural preservation alongside human rights protection, it is crucial to examine power structures and social hierarchies within coastal communities in Ghana. Further exploration of the balance between respecting cultural diversity and upholding universal human rights principles is warranted, offering an opportunity for scholars to delve deeper into this complex issue.

Policy makers need to recognize the unique cultural contexts of coastal communities and develop interventions that are specifically tailored to their cultural practices and beliefs. This requires considering the aspirations, values, and customs of the community in question. Promoting education and awareness programs in all coastal communities can facilitate dialogue and understanding among different stakeholders, including community members, policy makers, and human rights actors and advocates. These initiatives will encourage respectful discussions about cultural practices, raise awareness about human rights standards, and confront harmful norms.

To empower coastal communities to advocate for their cultural practices while also upholding their fundamental human rights and international standards, policy makers should implement measures such as training and literacy programs. These initiatives will enhance the capacities of coastal communities to understand their rights and actively participate in decision-making processes. Resolving conflicts between cultural practices and human rights standards necessitates collaborative efforts at the international, regional, and local levels. Policy makers must create an enabling environment that fosters cooperation among governments, international organizations, and local stakeholders. This collaboration should facilitate the exchange of best practices, lessons learned, and support in implementing culturally sensitive human rights policies.

Future research direction

Based on this study findings and conclusions, carrying out in-depth case studies in specific coastal communities in Ghana to examine the specific conflicts that arise between cultural beliefs and human rights standards, particularly in relation to sustainable fishing practices is needed. This research can provide detailed insights into the root causes of conflicts, the impact on cultural rights and fishing practices, and potential strategies for reconciliation. Additionally, exploring stakeholders and perspectives and experiences of community members including small-scale fishers, community leaders, women, and marginalized groups, to gain a deeper understanding of their cultural beliefs, their perceptions of human rights standards, and their perspectives on reconciling conflicts. This research can shed light on the complexities and nuances of cultural practices and their implications for sustainable fishing practices.

Thirdly, carrying out a comprehensive legal analysis of the international human rights standards and their compatibility with cultural practices in coastal communities will be a step in the right direction. This research can examine the legal frameworks, conventions, and treaties that apply to cultural rights and fishing practices, identify areas of tension or contradiction, and propose legal strategies or adaptations that can reconcile conflicts and protect both cultural rights and sustainable fishing practices. Also, investigating the effectiveness of existing policies and interventions aimed at reconciling conflicts between cultural beliefs and human rights standards in coastal communities is a crucial research need. This research can assess the impact of policy measures, identify best practices, and explore innovative approaches that promote cultural preservation while ensuring sustainable fishing practices. It can also explore the role of local governance structures, community-based management systems, and the involvement of various stakeholders in policy development and implementation.

Finally, exploring collaborative approaches and partnerships between coastal communities, government agencies, NGOs, and international organizations to address conflicts and find sustainable solutions. This research can examine successful collaborative initiatives, identify factors that contribute to their effectiveness, and provide recommendations for fostering meaningful collaborations that respect cultural rights, protect human rights, and promote sustainable fishing practices. By addressing these future research directions, scholars can deepen their understanding of the conflicts between cultural beliefs and human rights standards in Ghana’s coastal communities, and work towards finding practical and culturally sensitive solutions that reconcile these conflicts while preserving cultural rights and ensuring sustainable fishing practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the UKRI GCRF One Ocean Hub—a collaborative research project for sustainable development funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) via the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) under Grant Ref: NE/S008950/1. Special thanks also to Professor Elisa Morgera for her valuable guidance, advice, and manuscript review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Kwame Boateng

John Kwame Boateng, a PhD graduate from Pennsylvania State University (PSU), USA, serves as an Associate Professor at the University of Ghana’s Department of Adult Education and Human Resource Studies. His research spans development education, geography education, and human-environment interactions. With a focus on integrating emerging technologies into education, he explores their impact on mass education in Africa. Prof. Boateng has authored over 45 peer-reviewed articles and contributed to various book chapters. He actively engages in national and international research projects, including collaborations with the University of Education, Winneba. This study aligns with his broader research endeavours, emphasizing community empowerment and social networks, which he aims to continue advocating for in future endeavours.

References

- Adjei, J. K., & Sika-Bright, S. (2019). Traditional beliefs and sea fishing in selected coastalcommunities in the Western Region of Ghana. Journal of Geography, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjg.v11i1.1

- Adomako Ampofo, A., & Boateng, J. (2007). Multiple meanings of manhood among boys’ in Ghana. From Boys to Men: Social Constructions of Masculinity in Contemporary Society, 50–74.

- Agarwal, B. (2001). Participatory exclusions, community forest, and gender: An analysis for South Asia and conceptual framework. World Development, 29(10), 1623–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00066-3

- Agodzo, S. K., Bessah, E., & Nyatuame, M. (2023). A review of the water resources of Ghana in a changing climate and anthropogenic stresses. Frontiers. Water, 4, 973825. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2022.973825

- Ampofo, A. A. (1993). Controlling and punishing women: Violence against Ghanaian women. 102–111.

- Asante, E. A., Ababio, S., & Boadu, K. B. (2017). The use of indigenous cultural practices by the Ashantis for the conservation of forests in Ghana. SAGE Open, 7(1), 215824401668761. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016687611

- Baker, C. (2021). Learning from 20 years of small-scale fisheries co-management in Africa Duke University. PhD dissertation.

- Bita, C., & Forsythe, W. (2021). Marine cultural heritage & sustainable development in east Africa: Community engagement with marine cultural heritage. Heritage, 4, 1026–1048.

- Census of Marine Life (2010). Census of marine life: Wild and wonderful creatures. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://ocean.si.edu/ecosystems/census-marine-life/census-marine-life-wild-and-wonderful-creatures

- Chuku, E. O., Adotey, J., Effah, E., Abrokwah, S., Adade, R., Okere, I., Aheto, D. W., Kent, K., & Crawford, B. (2021). The Estuarine and mangrove ecosystem-based shellfisheries and food security project. Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography. University of Rhode Island, Narragansett. RII, USA. https://www.crc.uri.edu/download/FIN_12_31_21_Milestone-7-Regional-Shellfisheries-Report_508.pdf

- Cinner, J. E., McClanahan, T. R., MacNeil, M. A., Graham, N. A. J., Daw, T. M., Mukminin, A., Feary, D. A., Rabearisoa, A. L., Wamukota, A., Jiddawi, N., Campbell, S. J., Baird, A. H., Januchowski-Hartley, F. A., Hamed, S., Lahari, R., Morove, T., & Kuange, J. (2012). Ecomanagements of coral reef social-ecological systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(14), 5219–5222. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1121215109

- Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research Design Qualitative Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage, Thousand Oaks, 3-26.

- DESA. (2009). Creating an inclusive society: Practical strategies to promote social integration. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/egms/docs/2009/Ghana/inclusive-society.pdf

- Devine, J. (2017). Colonizing space, commodifying place: Tourism’s violent geographies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1226849

- Devine, J., & Ojeda, D. (2017). Violence and dispossession in tourism development: A critical geographical approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1293401

- Dosu, G. (2017). Perceptions of socio-cultural beliefs and taboos among the Ghanaian fishers and fisheries authorities: A case study of the Jamestown fishing community in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana International Fisheries Management (30 ECTS). Master thesis.

- EJF. (2021). A human rights lens on the impacts of industrial illegal fishing and overfishing on the socio-economic rights of small-scale fishing communities in Ghana London, 120 p. https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/EJF-DIHR-socio-economic-report-2021-final.pdf

- Gillard, M. L. (2010). Trokosi: Slave of the gods. Xulon Press.

- Golo, H. K., & Erinosho, B. (2023). Tackling the challenges confronting women in the Elmina fishing community of Ghana: A human rights framework. Marine Policy, 147, 105349.

- Golo, H. K., Ibrahim, S., & Erinosho, B. (2022). Integrating communities’ customary laws into marine small‐scale fisheries governance in Ghana: Reflections on the FAO Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small‐Scale Fisheries. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 31(3), 349-359.

- Goudineau, Y. (2003). Laos and ethnic minority cultures: Promoting heritage. UNESCO Publications.

- Holly, G., Rey da Silva, A., Henderson, J., Bita, C., Forsythe, W., Ombe, Z. A., Poonian, C., & Roberts, H. (2022). Utilizing marine cultural heritage for the preservation of coastal systems in East Africa. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 10(5), 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10050693

- Hügel, S., & Davies, A. R. (2020). Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: A review of the research literature. WIREs Climate Change, 11(4), e645. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.645

- Johnson, A. F., Kleiber, D., Gomese, C., Sukulu, M., Saeni-Oeta, J., Giron-Nava, A., Cohen, P. J., & McDougall, C. (2021). Assessing inclusion in community-based resource management: A framework and methodology. CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems.

- Karakara, A. A., Peprah, J., & Dasmani, I. (2022). Marine biodiversity conservation: The cultural aspect of MPA in Ghana. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2365192/v1

- Khosla, R., Banerjee, J., Chou, D., Say, L., & Fried, S. T. (2017). Gender equality and human rights approaches to female genital mutilation: A review of international human rights norms and standards. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 1–59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0322-5

- Kleiber. (2019). Gender-inclusive facilitation for community-based marine resource management. An addendum to “Community-based marine resource management in Solomon Islands: A facilitators guide” and other guides for CBRM. CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems.

- Lalancette, A., & Mulrennan, M. (2022). Competing voices: Indigenous rights in the shadow of conventional fisheries management in the tropical rock lobster fishery in Torres Strait, Australia. Maritime Studies, 21(2), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-022-00263-4

- Lawless, S., Cohen, P., McDougall, C., Orirana, G., Siota, F., & Doyle, K. (2019). Gender norms and relations: Implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00147-0

- Md, A., Gomes, C., Dias, J. M., & Cerdà, A. (2022). Exploring gender and climate change nexus, and empowering women in the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh for adaptation and Mitigation. Climate, 10(11), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10110172

- Mekonnen, H., Bires, Z., & Berhanu, K. (2022). Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Heritage Science, 10(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6

- Mohammed, A. S., Tuokuu, F. X. D., & Adda, E. B. (2023). Livelihood access and challenges of coastal communities: Insights from Ghana. Journal of Global Responsibility, 14(4), 452–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-02-2022-0017

- Ng’ang’a, J. W., Kioko, E. M., Wairuri, S. C., & Ngare, I. (2022). The ‘Bald’ ecosystem: Indigenous resource governance and restoration of Kivaa Forest, Kenya. East African Journal of Environment and Natural Resources, 5(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajenr.5.2.986

- Nicholls, R. J., Wong, P. P., Burkett, V. R., Codignotto, J. O., Hay, J. E., McLean, R. F., Ragoonaden, S., & Woodroffe, C. D. (2007). Coastal systems and low-lying areas. Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden and C. E. Hanson (Eds.) (pp. 315–356). Cambridge University Press.

- Nolan, C., Delabre, I., Menga, F., & Goodman, M. K. (2022). Double exposure to capitalist expansion and climatic change: A study of vulnerability on the Ghanaian coastal commodity frontier. Ecology and Society, 27(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12815-270101

- Nukunya, G.K. (1992). Tradition and change in Ghana. Ghana Universities Press.

- Nunoo, F., & Agyekumhene, A. (2022). Mangrove degradation and management practices along the coast of Ghana. Agricultural Sciences, 13(10), 1057–1079. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2022.1310065

- Persoon, G. A., & Minter, T. (2020). Knowledge and practices of indigenous peoples in the context of resource management in relation to climate change in Southeast Asia. Sustainability, 12(19), 7983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197983

- Sikweyiya, Y., Addo-Lartey, A. A., Alangea, D. O., Dako-Gyeke, P., Chirwa, E. D., Coker-Appiah, D., Adanu, R. M. K., & Jewkes, R. (2020). Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 682. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08825-z

- Small, C., & Cohen, J. (2004). Continental physiography, climate, and the global distribution of human population. Current Anthropology, 45(2), 269–277.

- Torell, E., Bilecki, D., Owusu, A., Crawford, B., Beran, K., & Kent, K. (2019). Assessing the impacts of gender integration in Ghana’s fisheries sector. Coastal Management, 47(6), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2019.1669098

- United Nations Mission in Liberia/United Nations Human Rights. (2015). An assessment of human rights issues emanating from traditional practices in Liberia. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/LR/Harmful_traditional_practices18Dec.2015.pdf

- World Bank. (2020). Resilient coastline, resilient communities annual report of the West Africa coastal areas management program of the World Bank group. Washington, DC. 80. p. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/462991621974738944/pdf/Resilient-Coastlines-Resilient-Communities.pdf