Abstract

In Ghana, terrestrial sand mining in rural and peri-urban areas negatively affects the livelihoods of the majority of the residents employed in land-based livelihoods. We examine the sustainability of the alternative livelihood strategies the residents in these areas adopt as they lose their original livelihoods to sand mining. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from 278 household heads and 23 key informants. Descriptive statistics and the chi-square test of independence were employed to analyse the quantitative data, while the qualitative data were analysed thematically. The study revealed that while more than half of the respondents had adopted alternative livelihood strategies as a survival strategy, the remaining household heads were unable to secure alternative livelihoods because of a lack of startup capital, inadequate skills, and the unattractiveness of the alternative livelihood options. Though the adoption of alternative strategies had contributed to improvements in food consumption, employment for some farmers displaced by sand mining, and the resilience of some household heads to handle shocks from sand mining, the strategies were largely unsustainable compared to the residents’ original livelihoods (farming). We recommend that the local government authorities develop policies in consultation with landowners to preserve and restore the original land-based livelihoods of the residents.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Sand is mined in both developed and developing countries mainly for the construction of infrastructural facilities as a result of increasing population growth and the high pace of urbanisation (United Nations Environmental Programme [UNEP], Citation2019, Citation2022). The global extraction of sand is increasing faster than the natural replenishment rate, thereby raising sustainability concerns among policymakers (UNEP, Citation2014; Pereira, Citation2020). All though sand is an abundant resource and often obtained from terrestrial sources, including floodplain deposits and residual soil deposits, and marine sources (shore and offshore deposits), the appropriate sand required for industrial activities is limited (Beiser, Citation2018).

Sand mining offers both positive and negative externalities to individuals and localities. On its positive side, besides its importance for the construction industry (Schrecker et al., Citation2018), sand mining is a source of livelihood for a large number of people (Saviour, Citation2012; Asante et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, unsustainable sand mining comes at the expense of other economic actors, such as farmers in communities closer to the mining sites. Terrestrial sand mining is linked with unrestrained land-use changes and a drastic reduction in agricultural activities (Asare et al., Citation2023). This is because sand mining competes with other actors employed in land-based livelihoods and threatens their livelihood security.

The Ga South Municipality and Gomoa East District are among the worst affected sand mining areas in Ghana as a result of their proximity to Accra and Kasoa, which are both experiencing a high pace of urbanisation (Dick-Sagoe & Tsra, Citation2016, Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2021; Asare et al., Citation2023, Citation2024). In addition to the surging rate of urbanisation, the ban on coastal sand mining in Ghana, coupled with the corrosiveness of the salty sand from the shores, has further resulted in the diversion of sand mining activities to the rural and peri-urban farming communities in these local government areas. However, the majority of the residents in the sand mining areas are employed in land-based livelihoods, especially farming (GSS, Citation2019). Therefore, secured access to and control over cultivable land is important for their very survival, as opined by Sen’s (Citation1981) entitlement approach. Residents in sand mining communities often have reported increased dispossession in agricultural livelihoods, which is caused by the significant reduction in farmlands, low crop yields, and low income as a result of the entitlement failure over farmlands occasioned by the widespread unsustainable sand mining (Farahani & Bayazidi, Citation2018; Anokye et al., Citation2022; Asare et al., Citation2024).

Under the prevailing conditions of widespread unsustainable sand mining on farmlands, competing claims over land, and land-use change, a broad range of livelihood possibilities are considered by the residents in the mining communities to augment their income or to enhance their consumption (Department for International Development [DFID], Citation2000). Some of the residents adapt their systems of farming to agricultural intensification, employ coping strategies, adopt other non-agriculture livelihood activities, and migrate or shift their farming activities far from their communities to distant areas (Jayne et al., Citation2014; Nin-Pratt & McBride, Citation2014; Cobbinah et al., Citation2015). The DFID (Citation2000) sustainable livelihood framework explains that the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies, however, may have profound implications for the livelihoods of the participating households and the stock of assets available to other residents. Though the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies is very important in sustaining rural livelihoods (Ellis & Freeman, Citation2004; Khatun & Roy, Citation2012), adequate access to and control over assets, which most rural people lack in the first place, have been recognised as important determinants for successful livelihood diversification (Katega & Lifuliro, Citation2014; Mesele, Citation2016). Hence, vulnerable residents in most cases adopt alternative livelihood strategies mainly as a survival approach to cope with or manage the shocks associated with sand mining, thereby leading to unsustainable outcomes.

Despite these concerns, the available literature associated with alternative livelihood strategies is largely based on informal gold mining (Hilson & Banchirigah, Citation2009; Banchirigah & Hilson, Citation2010), which has gained much public and research attention. There is limited information, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, on the alternative livelihood strategies used by residents in sand mining communities (Lamb et al., Citation2019). While the few findings on alternative livelihood strategies in small-scale gold mining communities might be similar to those in sand mining areas, it is still appropriate to investigate the strategies the residents of sand mining communities pursue. This is because small-scale gold mining and sand mining have different methods with respect to how they are mined, managed, and regulated. Apart from that, the value placed on the two resources differs; therefore, it is problematic to assume that all the issues are transferable. This article, therefore, examines the sustainability of the alternative livelihood strategies the residents in these areas adopt as they lose their original livelihoods to sand mining. The article consists of five sections: introduction, literature review, methodology, results, and discussion as well as conclusions, and recommendations.

2. Literature review

This section encompasses sustainable livelihood framework and the entitlement approach.

2.1. Sustainable livelihood framework

The sustainable livelihood framework offers a pro-poor strategy to understand the livelihoods of poor people. The concept of sustainable livelihood was put forward as a strategy to incorporate socio-economic and ecological considerations in a cohesive and policy-relevant structure for poverty alleviation (Krantz, Citation2001). A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (stores, resources, claims, and access), and activities required for a means of living. Alternative livelihood strategies are interventions that aim to reduce the prevalence of activities deemed to be environmentally damaging by substituting them with lower-impact livelihood activities that provide at least equivalent benefits (Wright et al., Citation2016). A household livelihood is said to be sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stress and shocks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation (Chambers & Conway, Citation1992). Therefore, ownership of land, the right to grazing, fishing, and hunting, and stable employment with adequate remuneration are examples of ways through which rural and peri-urban households may gain access to sustainable livelihoods.

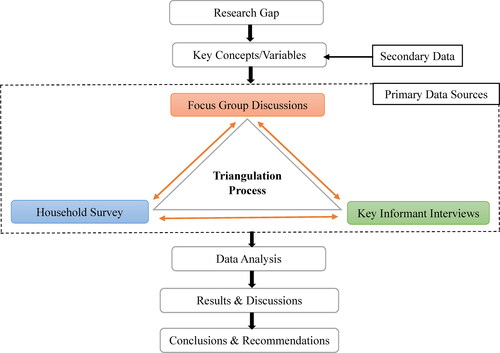

The sustainable livelihood framework pays attention to the various factors and processes that affect poor people’s ability to make a living in an economically, ecologically, and socially sustainable manner. It focuses on how poor people access and harness the opportunities economic growth offers and the strategies they employ to make a living (Krantz, Citation2001). There are three important features of the framework, as shown in . First, the sets of assets – natural, physical, human, financial, and social capital – a household is endowed with and uses to achieve its livelihood outcomes. Second, livelihood activities the household chooses based on the capital stock endowment. Scoones (Citation1998) noted that the livelihood strategies rural and peri-urban households pursue are agriculture intensification/extensification, livelihood diversification, and migration. The third feature of the sustainable livelihood framework is the transforming structure and processes. It includes the institutions, policies, and legislation that shape livelihoods by directly sending feedback to the vulnerability context while influencing ecological and economic trends through institutions to mitigate the shocks to household livelihoods.

Figure 1. DFID’s sustainable livelihood framework. Source: DFID (Citation2000).

2.2. Entitlement approach

Sen’s (Citation1981) entitlement approach explains that famine and poverty are frequently caused not by a lack of or inadequate supply of food but by individuals’ inability to get access to whatever food exists due to a loss of their entitlement (Devereux, Citation2001; Verstegen, Citation2001; Tiwari, Citation2007; Mogaka, Citation2013). The approach centres its analysis on effective legitimate command over natural resources, the various channels and determinants of access, the rules and institutions that control access, and the distinctive positions as well as vulnerabilities of different groups (Gasper, Citation1993). The entitlement approach is built on four tenets, namely: endowment, entitlement set, entitlement mapping, and entitlement failure (Sen, Citation1981).

First, the endowment set refers to all the resources or assets owned by an individual or a household that enable them to acquire different bundles of goods and services. Examples of these endowment sets include tangible assets such as livestock, land, money, and equipment, and intangible assets including skills, labour, and membership in a community (Osmani, Citation1993). Second, entitlement is the set of commodity bundles that could be attained legally by using the endowments and opportunities available to an individual (Sen, Citation1981). It is the set of alternative possibilities facing a person or household mirrored by the rules, conditions, and processes that affect how the individual’s entitlements are obtained from her or his endowment. Third, the entitlement mapping highlights the relationship that specifies the set of possible commodity bundles that are legally attainable from any given ownership bundle through trade, labour, production, inheritance, or transfer (Sen, Citation1981). Fourth, entitlement failure refers to a condition where production is inadequate. Mogaka (Citation2013) described four legal sources of access and control over resources, namely: production-based entitlement, trade-based entitlement, own-labour entitlement, and inheritance or transfer entitlement. From these sources, entitlement failures may also occur.

3. Materials and methods

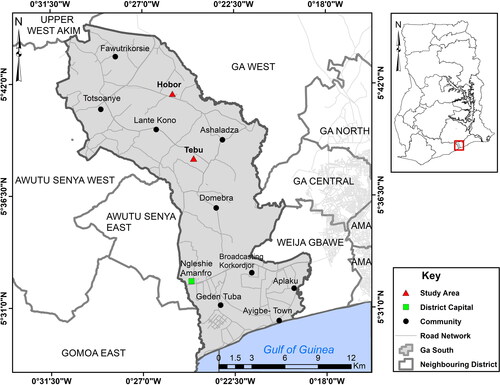

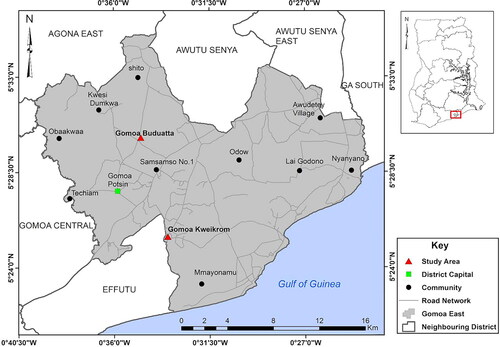

Four sand mining communities in the Ga South Municipality () and Gomoa East District () were profiled as the study areas. The Ga South Municipality lies within latitudes 5°48′N and 5°29′N and longitudes 0°8′W and 0°30′W. It covers a land area of approximately 358 sq km, with about 15 urban towns and hundreds of satellite communities and hamlets, with Ngleshi Amanfro as its capital. The Gomoa East District is also located within latitude 5°31’ 59.99″ N and longitude 0°24’59.99″ E and occupies a total surface area of about 276.652 sq km, with Gomoa Potsin as the administrative capital. The majority of the residents in the selected local government areas had engaged in farming as their primary livelihood activity for decades (GSS, Citation2019).

Figure 2. Map of Ga South Municipality, showing the study communities. Source: Department of Geography and Regional Planning, UCC, 2021.

Figure 3. Map of Gomoa East District, showing the study communities. Source: Department of Geography and Regional Planning, UCC, 2021.

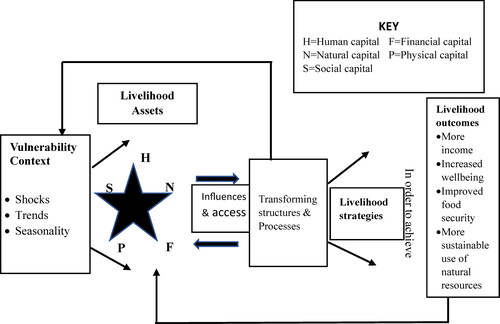

The mixed-methods approach to research was utilised to ensure triangulation of the data sources (). The approach was ideal for the study because it combined the strengths of both the qualitative and quantitative approaches to research to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). The qualitative approach employed the narrative research design, while the quantitative aspect used the descriptive research design. The study population comprised chiefs or landowners, sand miners, management staff of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Minerals Commission, local government authorities, the Department of Agriculture, household heads and members of both youth and women’s associations.

Both probability and non-probability sampling methods were used to select the study elements. Purposive sampling technique was used to select the officials of the EPA, Minerals Commission, local government authorities, the Department of Agriculture, and landowners with their knowledge of sand mining as the selection criteria. The selection of sand miners was based on accidental sampling due to the nomadic nature of their business. The household heads were selected through the use of the systematic sampling technique. Overall, 23 key informants () and 278 household heads were selected for the study. Two Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) comprising 7–12 persons were organised for members of the youth and women associations in each of the study communities. Interview guides and FGD guides were used to collect the qualitative data from the key informants and the FGD participants, respectively, while the interview schedule was used to collect the quantitative data from the household heads. The collection of data for the study commenced from March 3, 2021, to May 20, 2021, and lasted for almost 3 months.

Table 1. List of key informants interviewed.

The research was conducted in conformity with ethical standards in social science research to ensure confidentiality, anonymity, and protection of the privacy of the respondents. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Cape Coast Institutional Review Board prior to fieldwork. After the collected data were cleaned and coded, Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 21 was used to analyse the quantitative data, while the qualitative data were entered into NVivo 12 for thematic analysis. The quantitative data were analysed with descriptive statistics and the chi-square test of independence, while the qualitative data were analysed thematically to validate the quantitative data.

4. Results and discussions

This section presents the demographic characteristics of the household respondents and the results and discussions on the alternative strategies adopted, the outcomes of the adopted strategies, and the challenges confronting the alternative livelihood strategies.

4.1. Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics were in respect of sex, age, and primary occupation of the household heads. The majority (73.0%) of the household heads were males, while the rest were females, which conforms with the social structure of most rural and peri-urban areas in Ghana (GSS, Citation2019). While the youngest household respondent was 20 years old, the oldest was 87 years old. The median age was 48 years (mean = 48.49, standard deviation = 12.3 years, skewness = 0.515). Seventy-seven percent of the household respondents were farmers, while the others were traders (7.6%), craftsmen/women (5.4%), transport operators (4.0%), food vendors (2.2%), block manufacturers (1.4%), employees in the formal sector (1.4%), local alcohol brewers (0.7%), and collectors of forest products (0.4%) in that order. The higher engagement of the respondents in farming corresponds with the 65.2% found in rural areas in Ghana (GSS, Citation2019). The structure of the local economy demonstrates the importance of farmlands to the residents.

4.2. Adoption of alternative livelihood strategies

In order to establish the context for the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies, the respondents were asked to indicate the effects of sand mining on their original household livelihoods. The majority (86.6%) of sampled respondents claimed that sand mining had negatively affected their households’ livelihoods. The negative effects of sand mining reported by the respondents’ included a reduction in farm size, a reduction in yields, the destruction of farms by sand miners, irregular or low income, and increased risk in farming. The finding corroborates that of earlier studies (Farahani & Bayazidi, Citation2018; Anokye et al., Citation2022; Asare et al., Citation2023) that sand mining negatively affects the livelihood security of the local residents.

Further investigations showed that the majority (57.0%) of the household heads had adopted alternative livelihood strategies to complement their original livelihoods, as shown in . Most (90.3%) of the household heads who had adopted alternative livelihood strategies attributed their adoption to the adverse effects of sand mining on their original land-based livelihoods. Only 9.7% of the respondents had adopted alternative livelihood strategies to tap investment opportunities in the local economy. The reasons offered by the respondents suggest that the household heads largely adopted alternative livelihood strategies as a survival strategy to mitigate the negative effects of sand mining rather than as an investment opportunity. This corroborates Tadele’s (Citation2021) finding that alternative livelihood strategies in rural and peri-urban areas are mostly influenced by survival-induced factors.

Table 2. Household heads adoption of alternative livelihood strategy by community.

The household data revealed that, while the minimum number of years’ the respondents had adopted such alternative livelihoods was one, the maximum number of years was 10. The median number of years respondents had adopted the alternative livelihood strategies was 3 years (mean = 3.43, standard deviation = 1.686, skewness = 0.760). Further analysis showed that the proportion of household heads who had adopted alternative livelihood strategies was higher in Hobor (68.9%), followed by Gomoa Kweikrom (57.9%), than in Tebu (34.1%). The Chi-square test of independence showed a significant difference among the communities on the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies (χ2 = 15.463, df = 3, α = 0.05, p value = 0.001). The significant difference among the communities is not surprising because the residents of Hobor, for example, are settlers and have little control over land-use decisions. Therefore, when the landowners decide to allocate their farmlands to sand miners, most of the locals have no choice but to adopt alternative livelihood strategies. Generally, the proportion of household heads who had adopted alternative livelihood strategies (57.0%) in the study areas was higher than the national average of 34.6% in rural Ghana (GSS, Citation2019). This could be interpreted as a result of the negative effects of sand mining on the original livelihoods of the local residents, thereby the need to adopt alternative jobs to cater for their households needs.

In respect of the 105 respondents who had not adopted alternative livelihoods, the majority (78.0%) reported a lack of startup capital as their major limitation. Roy and Basu (Citation2020) and Doso et al. (Citation2016) studies revealed similar findings that startup capital was a major constraint to the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies among residents in even gold mining communities. The other reasons mentioned for the non-adoption of alternative livelihood strategies were: absence of investment opportunities in the communities (8.5%), old age (4.9%), inadequate skills (4.9%), and unattractiveness of the alternative livelihood options (3.7%). All 105 respondents confirmed that they would equally adopt alternative livelihood strategies to mitigate the negative effects of sand mining if the aforesaid limitations were addressed.

The household heads who had not adopted alternative livelihood strategies employed several coping strategies to ensure the survival of their household members. About 31.6% of them indicated a reduction in their household food consumption, while 19.8% asked for financial support from extended family members. The rest reported the use of agriculture intensification (16.9%), buying on credit (14.1%), migration to distant places for farmlands (10.1%), and borrowing farm produce from friends or family members (7.6%) in that order. The FGD participants and the key informants at the Department of Agriculture corroborated the coping strategies. An official of the Department of Agriculture remarked:

Many farmers have embraced agricultural intensification strategies such as the use of high-yielding varieties of crops and lining and pegging to optimise the little farmlands available to their households (Key informant, 2021).

4.3. Types of alternative livelihood strategies adopted and source of start-up capital

The distribution of responses showed that 37% of the household heads had diversified into petty trading. The trading activities reported were: buying and selling farm produce in front of their homes; tabletop provisions shops; hawking; selling cooked food such as porridge, rice, peanuts, and roasted corn; and selling used clothes, shoes, towels, and bedsheets. The other alternative livelihood strategies reported were: construction labouring jobs (18.7%), commercial motorbike riding (10.0%), and block making (7.9%), with the least being bicycle or motor repair (1.4%), as shown in . The evidence suggests that the residents of sand mining communities predominantly diversified into the non-agricultural sector. This confirms findings in Malawi and Ethiopia (Nagler & Naude, Citation2014) and Ghana (Afriyie et al., Citation2020; Asare et al., Citation2021) that most rural and peri-urban dwellers diversify into commerce and service-related livelihoods. The adoption of non-agricultural livelihood activities in the study areas is clearly linked to the degradation of the environment and its subsequent effects on crop and livestock farming as well as other agricultural livelihoods.

Table 3. Alternative livelihood strategies adopted by household heads.

The source of start-up capital for the alternative livelihood strategies was examined to determine how rural and peri-urban dwellers in sand mining communities access capital to enhance their livelihoods. The result showed that 67.6% of the household heads used their personal savings as start-up capital, while 14.3% relied on the support of family and friends. The other sources of startup capital reported were: loans (13.3%), group savings/susu (2.9%), and NGOs support (1.9%). The finding is consistent with that of Hofstrand (Citation2013) and GSS (Citation2019), who found that personal savings as well as support from family members or friends were the major sources of startup capital for alternative livelihood strategies. The result depicts that sand contractors did not provide support in the form of capital for the negatively affected residents as corporate social responsibility, compared to what Doso et al. (Citation2016) found in gold mining communities.

Further analysis showed that most (74.0%) of household heads reported no access to credit as start-up capital. The finding is consistent with that of Roy and Basu (Citation2020) and Asare et al. (Citation2021), who found that residents in rural and peri-urban areas have difficult access to credit, thereby restricting them from adopting alternative livelihood strategies. The implication is that, while the natural capital stock was under threat of degradation due to widespread illegal sand mining, the majority of the local residents lacked financial capital endowment to switch to the alternative livelihood sector. A higher proportion of the household respondents in Gomoa Buduatta (54.8%) had access to credit than those in Tebu (0.0%), Gomoa Kweikrom (13.2%), and Hobor (14.9%), as depicted in . The differences among the communities were significant at the 0.05 alpha level (χ2 = 54.347, df = 3, α = 0.05, p value = 0.000).

Table 4. Household responses on access to credit by community.

It was evident from the FGD participants that, while the residents in Gomoa Buduatta relied on bank agents who often visited the community to offer small loans to qualified residents, their counterparts in the other communities rejected such opportunities due to beliefs and fear about bank loans. Other reasons reported for the inadequate access to credit were: lack of information about where to access credit; lack of collateral security or guarantee for loans; a high interest rate on loans; already having several unpaid informal debts; and unfavourable repayment schedules. The finding corroborates earlier results in rural Afghanistan (Moahid & Maharjan, Citation2020) and Cameroon (Atamja & Yoo, Citation2021), where rural and peri-urban dwellers had inadequate access to credit because of fear of default consequences, a lack of collateral, and a high interest rate. Correspondingly, the evidence corroborates the finding in the Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS) 7, which reported low access to credit among residents in rural areas of Ghana (GSS, Citation2019).

4.4. Outcomes of the alternative livelihood strategies

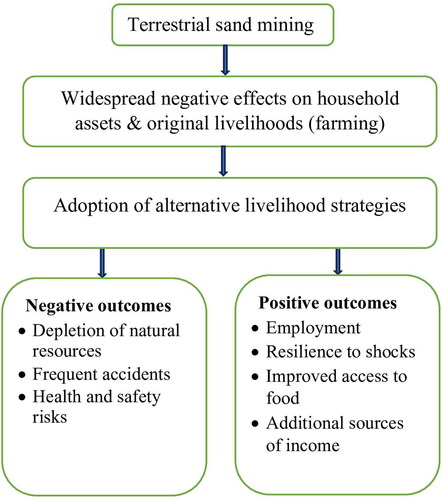

Insight from the entitlement approach and sustainable livelihood framework () illustrates that the outcomes of alternative livelihood strategies can either be positive in the form of additional income, employment, food security, enhanced resilience to shocks, and sustainable use of natural resources, or the reverse of these in the case of the negative outcomes. Therefore, the outcomes of the alternative livelihood strategies were examined based on these parameters, as depicted in .

Figure 5. Flow chart showing the outcomes of alternative livelihood strategies. Source: Authors construct.

4.4.1. Income outcomes

With the communities put together, 46.8% of the household respondents who had adopted alternative livelihood strategies reported an increase in their income, while 45.3% and 7.9% indicated no change or reduction in their income, respectively. Further analysis showed that the highest annual alternative livelihood income was GHS 18,000.00 ($1,440), while the least was GHS 700.00 ($65). The median annual income from the adopted strategy was GHS 4,800.00 ($384) (mean = GHS 5,439.27; standard deviation = GHS 3,401.490; skewness = 1.405). It is evident that, though the alternative livelihood strategies provided some extra income to the respondents, the median income from these strategies was less than Ghana’s national average income of GHS 8,034.30 ($642.74) reported by GSS (Citation2019). The finding suggests that the alternative livelihood strategies did not offer equivalent or, ideally, greater income to the residents than what they earned from their farming activities prior to the introduction of sand mining in the study communities.

The FGD participants indicated that the incomes earned from alternative livelihood strategies were used for the following expenditures: purchasing of food items, payment of medical bills, investment into farming, investment into the alternative strategies, payment of school fees, payment of utility bills (water, electricity, and mobile phone credit), payment of association dues, funeral donations, and provision of basic necessities such as dresses for household members. Another expenditure item that emanated from the female FGD participants in Hobor was the payment of offertory and tithe at church. The finding is consistent with Danso-Abbeam et al. (Citation2020) and Mohapatra and Giri (Citation2021) earlier results that investment in alternative livelihood strategies provides an opportunity to earn extra income that supplements the consumption and other basic needs of household members.

4.4.2. Food security outcomes

About 40.6% of the household heads noted an increase in their household access to food after adopting the alternative livelihood strategy, while 35.6% and 23.8% reported no change and a reduction in their household access to food, respectively. The FGD participants confirmed that their household’s access to food had relatively remained stable after adopting the alternative livelihood strategies. For instance, FGD participants who had diversified into the trading of food products shared the view that their household members used some of the products to satisfy their consumption needs. The finding corroborates the sustainable livelihood framework (), Mishra et al. (Citation2015), and Madaki and Adefila (Citation2014), that the adoption of alternative livelihood strategies contributes to food safety and access to essential services for the members of the participating household.

4.4.3. Resilience outcomes

On a three-point scale, the majority (79.1%) of the household heads noted that the alternative livelihood strategies had increased their household ability to handle shocks emanating from the negative externalities of sand mining on their original livelihoods. The remaining noted no change (18.0%) or reduction in their ability to handle shocks (2.9%). This agrees with evidence in Tanzania (Katega & Lifuliro, Citation2014) and Nigeria (Madaki & Adefila, Citation2014) that alternative livelihood strategies assist participating farmer households to handle shocks and trends. Similarly, the FGD participants and some key informants confirmed that there had been an improvement in their households’ ability to handle the negative effects of sand mining on their households after adopting the alternative livelihood strategies. A participant remarked:

When the miners destroyed my farmlands, I could barely tell how my family could survive. Thankfully, the income from commercial motorbike riding has been helpful to my household. I have acquired another farmland around Asamankese with part of my alternative livelihood income (Interviewee in Hobor, 2021).

4.4.4. Employment outcomes

Most (62.4%) of the household heads indicated that the alternative livelihood strategy had increased employment opportunities for their household members, while the remaining either indicated a reduction in employment (21.3%) or no change (16.3%). Interactions with the key informants at the Department of Agriculture and FGD participants confirmed that some local residents who lost their livelihoods to sand mining had gained employment in the alternative livelihoods sector, while a few others had also been engaged by the sand miners. A key informant and youth participant shared these words:

The Department of Agriculture has introduced alternative livelihood strategies, including snail, grasscutter, and mushroom farming, to the negatively affected farmers in the sand mining areas (Interviewee in GSMA, 2021).

Though sand mining has negatively affected the majority of the local residents, the influx of mining-related actors in this community has promoted other commercial activities such as volcanizing services, trading, and mobile money businesses for some residents (Interviewee in Buduatta, 2021).

4.4.5. Sustainable resource use outcomes

About 63.5% of the household respondents mentioned no change in the sustainable use of resources in the study communities after adopting alternative livelihood strategies, while 26.7% and 9.8% indicated a reduction and an increase, respectively. The FGD participants corroborated the household respondent’s opinion and offered four reasons to justify their claim. First, alternative strategies such as charcoal burning and firewood contribute to the depletion of the few remaining trees in the study communities. Second, demand for sand by construction labourers promotes widespread sand mining in other new areas. Third, the residents employed by sand miners and persons who traded at the mining sites were exposed to an unfavourable environment and poor working conditions. Fourth, frequent accidents by commercial motorbike riders required that the incomes of other household members be used to cater for the medical bills of the accident victims.

The researchers enquired from the respondents their opinion about the overall sustainability of the alternative livelihood strategies against that of their original livelihood. The majority (56.1%) of household heads indicated that their original livelihoods were more sustainable than the adopted strategies. The rest were not sure (27.3%) or reported that the adopted strategies were more sustainable (16.5%), as shown in . The findings support Hilson and Banchirigah (Citation2009) evidence that alternative livelihood programmes in mining communities were unpopular and unsustainable with the residents of mining communities compared to their original land-based livelihoods. This was confirmed through the interactions with the FGD participants and the key informants. An official of the Department of Agriculture shared these words:

The majority of the people in the mining communities have no other skill apart from farming, which they inherited from their forebears (Key informant, 2021).

Table 5. Sustainability between original livelihoods and alternative strategies by community.

A greater proportion of the household respondents in Hobor (67.6%) and Tebu (50.0%) indicated that their original livelihoods were more sustainable than the adopted strategy, compared to those in Gomoa Kweikrom (31.8%). This might be a result of the fact that the residents of Hobor and Tebu are settler farmers who have relatively limited knowledge of other alternative livelihood strategies compared to farming, which they have practiced for decades. Drawing insight from the entitlement approach and the sustainable livelihood framework (), the implication of the finding is that most of the respondents had limited endowment set to achieve sustainable livelihoods from the alternative livelihood sector. Therefore, if land-based livelihoods were not protected in the sand mining communities, the residents might face severe livelihood insecurities since the adopted alternative livelihood strategies were not yielding the expected sustainable outcomes.

4.5. Challenges of the adopted alternative livelihood strategies

The responses to the challenges of the alternative livelihood strategies were largely focused on petty trade, commercial motorbike riding, firewood and charcoal burning, and construction labour, as depicted in . First, those who had ventured into trading reported low sales due to the reduced purchasing power of the community members. It was revealed at the FGDs that the low purchasing power among the residents led to increased credit purchases, which were sometimes unpaid. The situation had contributed to the lockup of the little capital available to traders. Aside from low purchasing power and credit purchases, the respondents mentioned inadequate access to capital to expand their alternative livelihoods. The finding corroborates Asare et al.’s (Citation2021) finding in the Sunyani West district, where low patronage and inadequate capital were found to be major challenges for farmers who had adopted non-farm livelihood strategies.

Table 6. Challenges of the adopted alternative livelihood strategies.

Second, the respondents who were into construction labour jobs reported difficult tasks and exposure to health and safety challenges. It was revealed that the employers failed to provide the construction labourers with appropriate health and safety working gear to limit their exposure to risk. Besides, they reported that the employment was seasonal and came with irregular incomes. Third, firewood and charcoal burners also reported difficult access to raw materials (trees) due to the degradation of the vegetation by sand miners and exposure to harsh working conditions. Fourth, commercial motorbike riders reported frequent accidents as their major challenge. A similar finding was revealed by Anokye et al. (Citation2022) in a related study in the Awutu-Senya East municipality and Awutu-Senya West district of Ghana, where accidents involving tipper trucks and other transport operators were reported. Aside from the accidents, commercial motorbike operators allegedly mentioned frequent harassment by local police officers since commercial motorbike riding is illegal in Ghana. The motor riders also reported high maintenance costs as a result of the poor state of the road networks in the sand mining communities.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The article has provided evidence and contributed knowledge that the majority of the residents in the sand mining communities adopt alternative livelihood strategies, mainly as a survival strategy to mitigate the negative effects of the widespread terrestrial sand mining on their original land-based livelihoods. A greater number of the residents had adopted non-agricultural livelihood activities because of the degradation of farmlands and the risk in the farming sector. Though the respondents who had adopted alternative livelihood strategies reported that the strategies had improved their households’ access to food, resilience to shocks, employment of some family members, and additional income to cater for their household needs, the ability of the alternative strategies to provide sustainable livelihood outcomes was questionable because of several challenges reported by the respondents. These challenges included frequent accidents involving commercial motorbike riders and tipper trucks, high maintenance costs for transport operators due to the bad nature of the road network, low patronage of tradable goods, exposure to health and safety risks, small and irregular income and difficulty in accessing raw materials. For most of the locals who had not adopted alternative livelihood strategies, access to startup capital was their major limitation. This category of residents, therefore, employed coping strategies including a reduction in their household quantities of food consumed, soliciting financial support from extended family members, agricultural intensification, and borrowing farm produce from friends or other community members.

Five recommendations are made to ensure sustainable livelihoods in the study communities. First, the local government authorities and landowners should reserve some parcels of land for farming since it is the most preferred livelihood strategy among the residents in the mining areas. Besides, farming is the mainstay of the sand mining communities, wherein insecurities in farming affect almost all other sectors of the local economy. Second, the local government authorities should work with relevant institutions, such as the Microfinance and Small Loan Centre (MASLOC) and the Business Advisory Centre (BAC), to grant low-interest credit to interested residents in the sand mining communities to enable them to enhance their alternative livelihoods. Third, the local authorities and the central government should enhance the local economy through the construction of trade-related infrastructure like market facilities. This is because trading is the most preferred alternative livelihood strategy among the locals in the mining communities, and such investments could possibly stimulate the growth of the local economy. Fourth, construction employers should provide their workers with appropriate health and safety gear. This would help curb the risk construction workers face at the workplace. Fifth, the local residents employed in farming should adapt agriculture intensification strategies to maximise yields on the remaining farmlands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Afriyie, K., Abass, K., & Adjei, P. O. W. (2020). Urban sprawl and agricultural livelihood response in peri-urban Ghana. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 12(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1691560

- Anokye, N. A., Mensah, J. V., Potakey, H. M. D., Boateng, J. S., Essaw, D. W., & Tenkorang, E. Y. (2022). Sand mining and land-based livelihood security in two selected districts in the Central Region of Ghana. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 34(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-11-2021-0263

- Asante, F., Abass, K., & Afriyie, K. (2014). Stone quarrying and livelihood transformation in Peri-Urban Kumasi. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(13), 93–197. https//www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RHSS/article/view/13642

- Asare, K. Y.,Hemmler, K. S.,Buerkert, A., &Mensah, J. V. (2024). Scope and governance of terrestrial sand mining around Accra, Ghana. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 9, 100894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.100894

- Asare, K. Y., Koomson, F., & Agyenim, J. B. (2021). Non-farm livelihood diversification: Strategies and constraints in selected rural and peri-urban communities, Ghana. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 59(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2021.01360

- Asare, K. Y., Dawson, K., & Hemmler, K. S. (2023). A sand-security nexus: Insights from peri-urban Accra, Ghana. The Extractive Industries and Society, 15(5), 101322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101322

- Atamja, L., & Yoo, S. (2021). Credit constraint and rural household welfare in the mezam division of the North-West region of Cameroon. Sustainability, 13(11), 5964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115964

- Banchirigah, S. M., & Hilson, G. (2010). De-agrarianization, re-agrarianization and local economic development: Re-orientating livelihoods in African artisanal mining communities. Policy Sciences, 43(2), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9091-5

- Beiser, V. (2018). The World in a Grain: The story of sand and how it transformed civilization. Riverhead Books.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies.

- Cobbinah, P. B., Gaisie, E., & Owusu-Amponsah, L. (2015). Peri-urban morphology and indigenous livelihoods in Ghana. Habitat International, 50, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.002

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. Sage publications.

- Danso-Abbeam, G., Dagunga, G., & Ehiakpor, D. S. (2020). Rural non-farm income diversification: Implications on smallholder farmers’ welfare and agricultural technology adoption in Ghana. Heliyon, 6(11), e05393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05393

- Devereux, S. (2001). Sen’s entitlement approach: Critiques and counter-critiques. Oxford Development Studies, 29(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810120088859

- DFID. (2000). Sustainable livelihood: Current thinking and practice. Department for International Development.

- Dick-Sagoe, C., & Tsra, G. (2016). Uncontrolled sand mining and its socio-environmental implications on rural communities in Ghana: A focus on Gomoa Mpota in the Central Region. International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, 6, 31–37. https//www.indusedu.org/pdfs/IJREISS/IJREISS_847_56448.pdf

- Doso, J. S., Cieem, G., Ayensu-Ntim, A., Twumasi-Ankrah, B., & Barimah, P. T. (2016). Effects of loss of agricultural land due to large-scale gold mining on agriculture in Ghana: The case of the Western Region. British Journal of Research, 2(6), 196–221. http/api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:54207367

- Ellis, F., & Freeman, H. A. (Eds.). (2004). Rural livelihoods and poverty reduction policies. Routledge.

- Farahani, H., & Bayazidi, S. (2018). Modeling the assessment of socio-economic and environmental impacts of sand mining on local communities: A case study of Villages Tatao River Bank in North-western part of Iran. Resources Policy, 55, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.11.001

- Gasper, D. (1993). Entitlements analysis: Relating concepts and contexts. Development and Change, 24(4), 679–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1993.tb00501.x

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2019). Ghana living standards survey report of the seventh round. Ghana Statistical Service.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census general report volume 3A: Population of regions and district. Ghana Statistical Service.

- Hilson, G., & Banchirigah, S. M. (2009). Are alternative livelihood projects alleviating poverty in mining communities? Experiences from Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 45(2), 172–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802553057

- Hofstrand, D. (2013). Types and sources of financing for start-up businesses. Iowa State University, Extension and Outreach. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/wholefarm/html/c5-92.html

- Jayne, T. S., Chapoto, A., Sitko, N., Nkonde, C., Muyanga, M., & Chamberlin, J. (2014). Is the scramble for land in Africa foreclosing a smallholder agricultural expansion strategy? Journal of International Affairs, 67(2), 35–53.

- Katega, I. B., & Lifuliro, C. S. (2014). Rural non-farm activities and poverty alleviation in Tanzania: A case study of two villages in Chamwino and Bahi districts of Dodoma region (REPOA Research Report No. 14/7). Repoa. http://www.repoa.or.tz/documents/REPOA_RR_14_7.pdf.

- Khatun, D., & Roy, B. C. (2012). Rural livelihood diversification in West Bengal: Determinants and constraints. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 25(347), 115–124. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/126049?v=pdf

- Krantz, L. (2001). The sustainable livelihood approach to poverty reduction. SIDA. Division for Policy and Socio-Economic Analysis, 44, 1–38.

- Lamb, V., Marschke, M., & Rigg, J. (2019). Trading sand, undermining lives: Omitted livelihoods in the global trade in sand. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(5), 1511–1528. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1541401

- Madaki, J. U., & Adefila, J. O. (2014). Contributions of rural non-farm economic activities to household income in Lere Area, Kaduna State of Nigeria. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 4(5), 654–663.

- Mesele, B. T. (2016). [Rural non-farm livelihood diversification among farming households in Saharti Samre Woreda, Southeastern Tigray] [MSc thesis]. School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Mishra, A. K., Mottaleb, K. A., & Mohanty, S. (2015). Impact of off-farm income on food expenditures in rural Bangladesh: An unconditional quantile regression approach. Agricultural Economics, 46(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12146

- Moahid, M., & Maharjan, K. L. (2020). Factors affecting farmers’ access to formal and informal credit: Evidence from rural Afghanistan. Sustainability, 12(3), 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031268

- Mogaka, M. M. (2013). [The Effects of cash transfer programmes on orphans and vulnerable children’s (OVCs) wellbeing and social relations: A Case Study of Nyamira Division, Nyamira County] [PhD thesis]. University of Nairobi.

- Mohapatra, G., & Giri, A. K. (2021). How farm household spends their non-farm incomes in rural India? Evidence from longitudinal data. The European Journal of Development Research, 34, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00449-2.

- Nagler, P., & Naude, W. (2014). Non-farm entrepreneurship in rural Africa: Patterns and determinants (IZA Discussion Paper no. 8008). Institute for the Study of Labour.

- Nin-Pratt, A., & McBride, L. (2014). Agricultural intensification in Ghana: Evaluating the optimist’s case for a Green Revolution. Food Policy. 48, 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.004

- Osmani, S. R. (1993). Growth and entitlements: The analytics of the green revolution. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Pereira, K. (2020). Sand stories: Surprising truth about the global sand crisis and the quest for sustainable solutions. Rhetority Media.

- Roy, A., & Basu, S. (2020). Determinants of livelihood diversification under environmental change in coastal community of Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 30(1–2), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529120946159

- Saviour, N. M. (2012). Environmental impact of soil and sand mining. International Journal of Science, Environment and Technology, 3, 221–216.

- Schrecker, T., Birn, A. E., & Aguilera, M. (2018). How extractive industries affect health: Political economy underpinnings and pathways. Health & Place, 52, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.05.005

- Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable and rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper No. 72. Institute for Development studies.

- Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford University Press.

- Tadele, E. (2021). Land and heterogeneous constraints nexus income diversification strategies in Ethiopia: Systematic review. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00338-1

- Tiwari, M. (2007). Chronic poverty and entitlement theory. Third World Quarterly, 28(1), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590601081971

- UNEP. (2014). Sand, rarer than one thinks. UNEP.

- UNEP. (2019). Sand and sustainability: Finding new solutions for environmental governance of global sand resources. UNEP.

- UNEP. (2022). Sand and sustainability: 10 strategic recommendations to avert a crisis. UNEP.

- Verstegen, S. (2001). Poverty and conflict: An entitlement perspective (CPN Entitlement Briefing Paper). https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/201602/20010900_cru_other_verstegen.pdf.

- Wright, J. H., Hill, N. A. O., Roe, D., Rowcliffe, J. M., Kümpel, N. F., Day, M., Booker, F., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2016). Reframing the concept of alternative livelihoods. Conservation Biology: The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 30(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12607.