Abstract

Indonesia is a salak producing country with five superior varieties, namely: Salak Pondoh, Salak Madu, Salak Gading, Salak Gula Pasir and Salak Sidempuan. The large number of Indonesian salak which are claimed to be Thai fruit products marketed to China shows the weak legal protection for salak fruit, which has a geographical indication of originating from Indonesia. This study collects data from relevant online literature and then analyzes them based on inductive analogies. By analogizing the concept of marketing communication tetrahedron analysis from Kevin Lane Keller, which considers four factors (consumer, communication, response and situation), through inductive analogy this paper offers steps that must be taken by the Indonesian government to provide protection and development of salak. Fruit products originating from Indonesia need to be protected and developed through legal measures, good marketing communication, and preservation technology so that they can compete in the international market.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Salak is a fruit that only grows in tropical countries like Indonesia and is also a Geographical Indication product originating from Indonesia. Claims by other countries regarding salak fruit on the global market as if the product originates from their country require the attention of the Indonesian government to take strategic legal steps. The introduction, marketing, and preservation of salak fruit, which does not last long, is, of course, a challenge in itself which needs to have a concrete solution, such as how to carry out good marketing communications through the analogy of Kevin Lane Keller’s concept regarding the Tetrahedron and applying preservation technology so that salak fruit can last a long time.

1. Introduction

Historically, Geographical Indications (GIs) are part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICT), which is a type of communal intellectual property, in addition to Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCE), Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Genetic Resources (SDG). GIs are generally identified with the area of origin which geographically refers to a certain area that is not shared by other regions.

In its development, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) has defined and protected GIs as certain types of intellectual property that can establish a relationship between products and their place of origin and prevent negative market exploitation of natural resources and their by-products (Kireeva & O’Connor, 2010; Singh et al., Citation2023). GIs, like trademarks, aim to identify goods originating in a particular region and the quality associated with their place of origin (Raustiala & Munzer, Citation2007). The success of protecting GIs is highly dependent on product marketing and promotion, which requires the will and hard work of all stakeholders within a country (Das, Citation2010), especially the role of government and public policy steps taken (Hoang & Nguyen, Citation2020). The main challenge for countries in Asia relates to the large number of unused registered GIs in the market (Marie-Vivien, Citation2020) is the tendency to rush to register potential GIs, but after registration, there is no guidance and assistance so that the product remains of high quality, ensuring farmers get a fair selling price, including clear and sustainable packaging, promotion and market share.

GIs can be defined as a sign aimed at an area which due to natural and human factors shows the characteristics, quality and reputation of goods and services, a good understanding of GIs as well as to protect, protect and preserve the area’s traditional craft products (Covarrubia, Citation2019a). In fact, GIs do not only indicate the region or region of origin but are also heavily influenced by the quality of a product, goods and services. Who doesn’t know, for example, Mozzarella Cheese that comes from Italy, Swiss brand watches that come from Switzerland, Holland Bakerey bread that comes from the Netherlands, or Mercedes-Benz cars from Germany. Of course, these products are not only famous for indications of origin, but also for their quality and reputation. The quality and reputation then make the price more expensive compared to other similar products. Building the reputation and quality of a product worldwide cannot only depend on the characteristics of the region or region of origin of a product, more than that it requires seriousness and hard work which is not for a moment from all stakeholders, especially the state as a maker and policy maker. GIs is no different from well-known brands, which are always sought after by consumers because of their quality, even though the price is very expensive (Simatupang, Citation2023).

The spirit of legal protection for GIs in its development cannot be separated from the perspective of the international world to protect communal intellectual property. The seriousness of developing countries (Indonesia, India and Brazil) to protect GIs is actually not in line with the wishes of developed countries, especially the US which wants to take advantage of communal intellectual property with justification as world cultural heritage to apply for patents and brands in order to gain economic benefits. from the registration. Although, on the other hand, the EU currently in its trade policy has established serious protection for its GIs products, especially food products, regardless of the issue of conflict with the US in seeing the concept of GIs protection (Huysmans, Citation2022).

The construction of international law regarding GIs is contained in several conventions including the 1983 Paris Convention relating to the protection of industrial property, the 1891 Madrid Agreement regarding prosecution for false or fraudulent indications of the source of goods, the 1958 Lisbon Agreement concerning the protection of designations of origin and international registration, the TRIPS Agreement of 1995 and the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications of 2015 (Geneva Act). All of these international provisions regulate the importance of protecting GIs, as a concept of legal protection for goods and services originating from certain areas (Adebola, Citation2022).

Conceptually, GIs originate from the French Appellation of Origin (AOO) regime, which initiated maximum protection for GIs violations. Most European countries like the idea because the TRIPS Agreement only considers minimum standards of protection. The discussion on the protection of the GIs regime has achieved new commitments during the post TRIPS era in the form of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Although the US is still trying to ensure that GIs comply with the trademark law system (Hari & Raju, 2022).

Indonesia is a country that has a lot of interests in terms of legal protection for GIs, considering that Indonesia has the geographical bonus of 17,499 islands with a water area of 5.8 million km2 and a coastline length of ±81,000 km (Agus Haryanto, Citation2015). Indonesia also has 25% of plants and flowering plants in the world with a total of 20,000 species and 40% of which are native to Indonesia (Cecep Kusmana, Citation2015). Of course, this geography bonus must be realized as well as a threat from foreign infiltration. Of course, this threat is not something new, considering that history has recorded how the Dutch colonized Indonesia for hundreds of years, starting with an interest in the natural wealth of the archipelago. The vast land, sea and air geographical area of Indonesia has provided economic benefits, if the natural wealth can be developed as a type of communal intellectual property that is unique to Indonesia in the form of potential Gis (Simatupang, Citation2023).

However, at the same time, the commercial use of original Indonesian products to obtain their economic rights by developed countries has also occurred, such as: the case of Gayo coffee whose brand was registered under the name Gayo Mountain Coffee by European Coffee Bv and the case of coffee originating from the South Sulawesi region (Toraja) whose name has been registered and used in the United States of America. This includes Toraja coffee which refers to the area of origin of South Sulawesi. It turns out that since 1976 the brand has been registered by the Japanese company Key Coffee Co (Dara Quthni Effida, Citation2019). The claims of developed countries by registering various brands that are potential Indonesian GIs show that the legal protection for Indonesian GIs is still weak (Kusuma & Roisah, Citation2022).

One of the original fruit production from Indonesian GIs with promising economic potential to be developed is salak (salacca zalacca). In Indonesia, there are quite a number of types of salak which are named based on the region or region of origin, including: salak Pondoh, salak Condet and salak Bali (Schuiling, Citation1991). Lately, there have been so many Indonesian salak fruit that are claimed to be fruit products from Thailand which are marketed to China. This is a challenge for Indonesia and at the same time shows the weak legal protection for salak fruit originating from Indonesia (https://www.Antaranews, 2009). This research will discuss what steps the Indonesian government needs to take in providing protection and development of salak fruit products originating from Indonesia in order to compete in the global market.

As a comparison, the legal policy regarding GIs in several ASEAN countries is that there is practical implementation in 8 out of 10 countries by making legal regulations that are sui generis systems (Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos, Singapore, Myanmar). Two other countries in Asia, namely India and Japan, also actively implement GI policies. Therefore, more collective organizational involvement is needed to unite stakeholders, while playing a central role in structuring and managing GI products (Indications, 2020).

Each country certainly has its own reasons and arguments in responding to how to regulate GIs in its legal system while still considering the characteristics of each country. Certification of GIs is justified because of its ability to correct information asymmetry and will simultaneously benefit consumers. Certification of GIs carried out by the state under a sui generis regime is one option because it is considered more appropriate to satisfy consumer preferences and can achieve each country’s national development strategy (Gangjee, Citation2017).

2. Literature review

2.1. Current perspectives in marketing communications

The development of communication tools as marketing media from the traditional era to the digital era has shown rapid progress. Communication tools using social networking platforms are the media that people are most interested in today because they are recognized as more effective and efficient.

The lack of access to markets that results in loss of information to rural farmers is common in developing countries. This is due to the lack of mastery of information and communication technology (Sikundla et al., Citation2018). Specifically, one of the studies in Pakistan, for example, farmers make various use of digital and traditional media in accessing information, such as: cell phones, internet, television, radio, newspapers, counseling, market commission agents, and exchanging information among farmers (Yaseen et al., Citation2023). The use of seminar and speech elements in public relations activities to enhance the company’s positive image has been replaced by digital public relations which is growing rapidly today (Nyagadza & Mazuruse, Citation2021). The development of information and communication technology has discovered how important network theory is as a critical basic “law” in many social media platforms, which are believed to be fast media for conveying messages and information (McHugh & Perrault, Citation2022).

2.2. Tetrahedron: Concept and “analogy”

The term tetrahedron is basically a term commonly used in mathematics, especially geometry. The tetrahedron or regular triangle is a field of science that wants to see how the function and importance of each side and area of the triangle is meant. The concept of the tetrahedron was then adopted into communication science to make an analogy of how dimensions such as: consumer, communication, response and situation, are like the fields of in a regular triangle.

The concept of the tetrahedron adopted into communication science is a concept in the field of marketing to classify and analyze various influencing factors in four dimensions, namely: consumer, communication, response and situation (Kevin Lane Keller, Citation2001). Classical consumer responses to marketing that move linearly and sequentially have now been developed by adding more specific variables that are believed to influence consumer attitudes through various responses (Hanekom, 2016). Currently, the development of web-based communication concepts, ranging from advertising, marketing communications, public relations and promotional messages on the World Wide Web, is increasingly popular. This aims to drive consumer responses to buy as well as to identify the marketing communication paradigm from offline to online and see a comparison of the characteristics of online and traditional mass media (R. B. & G. A. Hanekom, 2007).

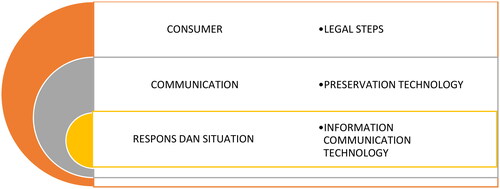

In writing, this article will not make the four factors referred to as the basis for determining what communication media will be used in product development, but will try to “assess” the four factors referred to and then “analyze” them into concrete steps that need to be taken by the Indonesian government to development of salak products so that they can compete in the global market.

3. Material and methods

The research method used in writing this article is a normative legal research method by conducting literature studies on secondary data through the use of internet media, including: https://kikomunal-indonesia.dgip.go.id/ and https://data.go.id/home. Furthermore, this study uses the concept of Kevin Lane Keller (Kevin Lane Keller, Citation2001) the marketing communications tetrahedron by analyzing the factors that influence the effectiveness of marketing communications in four broad dimensions, namely: consumer factors, communication, response, and situation. This research does not directly use the concept of the marketing communication tetrahedron with the factors that influence it, but uses an inductive analogy by offering new factors that are considered “similar” to support the success of salak fruit development in Indonesia.

Data were collected through relevant online literature and then analyzed based on inductive analogies by offering new factors to support the development of salak fruit in Indonesia. These factors are basically the development or analogy of the tetrahedron concept, as can be seen in and .

Figure 1. Kevin Lane Keller’s tetrahedron concept.

Source: Kevin Lane Keller, Citation2001.

Figure 2. Inductive analogy of the tetrahedron concept.

Sumber: Source: Inductive Analogy of the Tetrahedron Concept, Kevin Lane Keller (Citation2001).

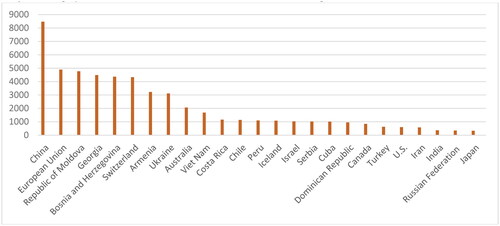

Graph 1. Geographical indications in force for selected National and Regional Authorities, 2020.

Source: World Intellectual Property Indicators Report 2021.

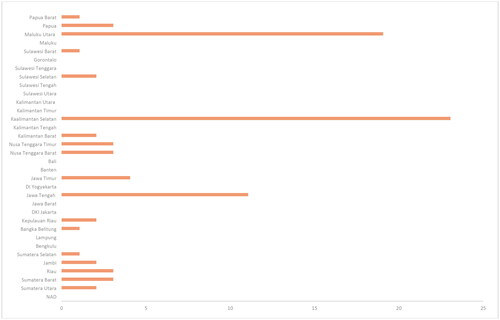

Graph 2. Potential geographical indications of Indonesia per province.

Source: https://kikomunal-indonesia.dgip.go.id/, data is processed until August 8, 2023.

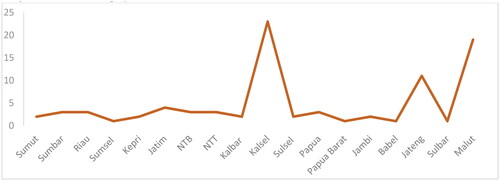

Graph 3. Potential geographical indications in 18 provinces.

Source: https://kikomunal-indonesia.dgip.go.id/, data are processed until August 8, 2023.

4. Findings

4.1. Get to know salak from Indonesia

In the context of regional distribution, Europe has the most GIs that apply in all regions, namely 57.1%, followed by Asia (33.1%), Latin America and the Caribbean (3.7%), Oceania (3.6%) and North America (2.5%). According to WIPO records, the number of existing GIs for selected national and regional authorities is mostly owned by China followed by the EU and other countries.

Indonesia itself, starting in 2016, has regulated GIs based on Law Number 20 of 2016 concerning Marks and GIs, which provides the meaning of GIs as part of a brand as stipulated in Article 1 number 6 that GIs is the origin or a sign indicating the original area of a product. goods and services due to geographic environmental factors including natural factors, human factors or a combination of the two factors which give a certain characteristic to the goods produced, reputation and quality of production, for example, the production of public goods and services.

Until today, Indonesia has not specifically regulated communal intellectual property rights (sui generis). New legal protection is carried out based on general laws, for example, TCE which is regulated as part of Copyrights, including GIs as part of Marks and GIs. According to data on the website of the Directorate General of Intellectual Property, Ministry of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia, there are not too many potential GIs recorded, when compared to the potential for GIs in India which has geographical characteristics that are almost similar to Indonesia. It must be realized that not all GIs have the potential to be developed because GIs development needs to pay attention to whether the product sells well in the market or not.

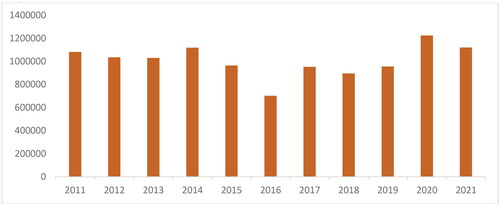

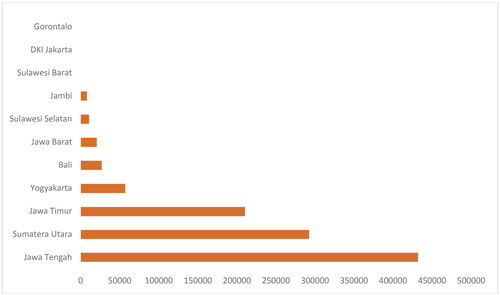

Of the 35 provinces throughout Indonesia, only 51% (18 provinces) have their Gis potential recorded at the Directorate General of Intellectual Property, Ministry of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia. Of the 18 provinces that have GIs records, none has recorded GIs of salak fruit. According to DataIndonesia.id, there was quite a lot of salak fruit production for the 2011–2021 period, and this salak fruit is also native to Indonesia. An overview of the data referred to can be seen in Graphs 1, 2, 3 and 4.

By region, Central Java is the largest salak producer in Indonesia with a production of 432,097 tons. This amount is equivalent to 38.57% of the total national salak fruit production last year. North Sumatra is in second place with salak production of 292,881 tons. Then, East Java has a salak production of 210,587 tons. Salak production in Yogyakarta was recorded at 57,296 tons. Then, Bali and West Java produced snake fruit of 27,080 tons and 20,704 tons, respectively. South Sulawesi occupied the seventh position with 10,856 tons. Meanwhile, salak production in Jambi reached 8,235 tons. Meanwhile, Gorontalo is the province that produces the least zalacca, namely nine tons. Above it are Jakarta and West Sulawesi, each of which produces 17 tons and 84 tons of salak.

However, the development of Indonesian salak production seems slow, especially in terms of marketing. The marketing problem, by taking one example of Salak Sidempuan, is a problem in the trade system. The salak sales margin is very wide from farmers to consumers, making farmers completely disadvantaged. According to data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) in 2018, the retail price of salak that consumers buy at the Padang Sidempuan market ranges from Rp. 10,000-Rp. 15,000, some even up to Rp. 20,000 per kilogram, while the selling price at the farm level is only around Rp. 1000–Rp. 3000 per kilogram only (https://www.gosumut, 2023). Tracing the history of salak garden farmers in Sidempuan 10–20 years ago who were able to perform the Hajj 2 to 3 times, now they are only memories. There are five types of salak that thrive in Indonesia, starting from salak Pondoh, salak Madu, salak Gula Pasir and salak Sidempuan. Each type of salak has different characteristics of fruit shape, color and taste. An overview of the data referred to can be seen in Graph 5 and .

Table 1. Types and characteristics of salak from Indonesia.

Since the birth of the Agreement on TRIPS, efforts to protect GIs have become increasingly important in the global economy (Davies, Citation1998). In fact, Gis is a field that intersects with local issues, so that the protection scheme cannot be separated from a country’s policies. GIs aspects began to be protected in France and harmonized in the EU (Marie-Vivien, Citation2008). Since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity, the relationship between the protection of TCE and GIs has become two interesting aspects for discussion. GIs are expected to create a global market with local control over their brand, quality and production methods (Kamperman Sanders, Citation2010).

The WTO Agreement on TRIPS as the first multilateral international agreement (although not the first international agreement) that provides the definition and protection of GIs as certain types of intellectual property (Kireeva & O’Connor, 2010a). The relatively global phenomenon has provided protection against GIs. TRIPS as part of intellectual property has also recognized GIs as a major part of intellectual property, nearly 76 countries protect GIs based on their particular legal system (sui generis), where registration of geographical names is defined as a separate type of intellectual property (Vittori, Citation2010).

The debate on how complex GIs protection is can take the example of GIs protection on Basmati rice. The example of Basmati rice will illustrate the differences in the goals of protecting GIs in India and Pakistan from those in Europe. Europe is a new market for Basmati, and the EU establishes import regulations based on its tradition of food quality. The increase in Basmati exports raises the issue of efficient protection in the international market, but still adapted to the needs of India and Pakistan. On the one hand, Basmati has long been defined as the name of a plant variety that has evolved. On the other hand, Basmati has not been registered as a GIs, because the concept of GIs is still new in India and Pakistan. The Basmati case is a common issue of protecting GIs in the world, how to deal with tradition versus modernity, product definition versus production methods, and geographical environment. (Marie-Vivien, Citation2020).

The essence of GIs is collective rights and the level of success depends heavily on the collective action of the target group and effective governance by implementing agencies (Radhika et al., Citation2021). In the production of commodities between producers basically compete, this situation is known as the commodity trap. Farmers have long engaged in collective marketing arrangements to differentiate their produce from others. GIs are an increasingly popular instrument of collective marketing management today. Traceability of local and unique food products is very important to provide market protection and consumer confidence (Ceccobelli et al., Citation2019).

5. Discussion

5.1. Practice of development of salak fruit towards international market

5.1.1. Legal steps

The problem of the difficulty of protecting GIs as part of communal intellectual property in the intellectual property rights regime has in practice been extensively studied. Among them, research results (Carugno, Citation2018) argues that traditional folk music that has been played for a long time in certain areas, as an expression of culture and identity can be considered as a community heritage. However, the owners of traditional folk music are not certain composers, but all members of the local community. This runs counter to efforts to copyright traditional folk musical expressions, as copyright laws often do not recognize this form of collective ownership. In China, according to research results (Zhang & Bruun, Citation2017) argues that local norms actually conflict with the notion of global intellectual property rights. China has its own intellectual property rights norms which are formed from the convergence of politics, economy and culture, so that China tends to form its own laws that are different from western countries. Communal intellectual property as a cultural heritage offers traces of the past that shape cultural identity (De Clippele, Citation2021). Cultural heritage is a priceless treasure for mankind (Cheng & Yuan, Citation2021). Cultural objects have a special status, protected, because of the value of “inheritance,” which is intangible for humans, as a symbol of identity (Campfens, Citation2020). The introduction of the concept of “cultural heritage” is a relatively recent achievement of international law. At the same time, “cultural heritage” is only one of the terms used in international treaties and other normative instruments (Ferrazzi, Citation2021). Globalization has seen cross-cultural exchange, cultural forms and cultural diversity.

Salak fruit as a plantation product which indicates the origin of Indonesia must begin with legal protection measures. Article 22 TRIPS has provided legal protection for communal intellectual property, one of which is the protection of GIs. Until now, Indonesia has Law Number 20 of 2016 concerning Marks and Geographical Indications. This regulation is felt to be insufficient to provide protection because it has not specifically regulated (sui generis) related to GIs, as has been done by India which has similarities with Indonesia as a country that has abundant natural resources. Legal steps taken by several countries to provide protection for their local country products that have indications of GIs are by making special arrangements (sui generis) regarding the legal aspects of GIs. The legal step for establishing this special rule also needs to be followed by assistance and guidance to areas that have potential GIs from salak fruit that have the potential to be developed.

5.1.2. Preservation technology

In international discussions, salak is a fruit that is often referred to as an “exotic” fruit because it is a tropical fruit that has not yet been found on the global market but has promising potential to be developed, considering that in terms of taste, texture quality and nutritional content it is liked by many consumers (Fernandes et al., Citation2011). Salak is a fruit that contains high fiber and carbohydrates, salak also has bioactive antioxidants such as vitamin A, vitamin C and phenolic compounds. (Leong & Shui, Citation2002; Leontowicz et al., Citation2006; Lestari et al., Citation2001; Setiawan et al., Citation2001). However, salak has a short life, not more than 1 week because it matures quickly. In general, salak fruit is sold in fresh form, and dried salak is still not sold in the market due to its relatively short shelf life.

Salak is a type of tropical fruit native to Indonesia, which has superior potential for export, although on the other hand salak tends to deteriorate quickly if it is delayed in its utilization, because after being harvested, salak continues to carry out physiological activities such as respiration and transpiration. With these physiological activities, the quality of the fruit will gradually decrease, the fruit skin will dry and the fruit flesh will begin to wilt, the symptoms of pathogen infection will begin to appear, until finally the fruit will become rotten.

The Indonesian Agricultural Research and Development Agency through the Agricultural Postharvest Center has produced postharvest technological innovations to increase the shelf life of salak fruit by using modified atmosphere packaging for export distribution and transportation with an aging rate of salak fruit for export purposes ranging from 60%–70% with the age of the salak fruit. Five months or less than 6 months. Before packaging the salak fruit is dipped in 5% natural anti-microbial for 30 s. Then packed with modified atmosphere (PE 0.04:72 micro perforation) with a capacity of 5 kg/carton and combined with packing stacking using an aeration system pattern. Storage carried out at a temperature of 10–150 °C can extend the freshness of the zalacca fruit. This technology can extend the shelf life of salak fruit to 21–30 days. With a shelf life of 21–30 days, the market reached is wider, including the export market.

Another way can be done by coating nanocomposites on salak fruit. This can reduce weight loss and inhibit microbial growth significantly. These results indicate that pectin-based nanocomposite coatings can provide an alternative method for maintaining the storage quality of salak fruit (Sabarisman et al., Citation2015). The “putri malu” (mimosa pudica) plant can also be used as a natural alternative preservative for salak fruit. The shy daughter’s plant extract can preserve salak fruit at a concentration of 5% with a storage time of 22 days (Astuti et al., Citation2020).

5.1.3. Information and communication technology

Research on agricultural development in Indonesia, especially related to agricultural technology and innovation, has actually been carried out a lot. The results of agricultural research are basically important information related to production and marketing techniques designed to improve or solve problems in agriculture. This information is not just consumption and reference material for other researchers but is also intended for farmers as an innovation that can be applied to increase productivity and improve the welfare of farmers. Various attempts have been made to collect and publish the results of agricultural research to the public through various media; however, information on the results of agricultural research cannot be disseminated effectively and efficiently to farmers as the main target of agricultural development (Novi et al., Citation2014). Farmers’ main access to various agricultural information and innovations is a very crucial issue in determining the success of agricultural and rural development (Subejo, Citation2011). The results of other studies show that ownership of information and communication technology media is quite high, especially conventional media and new media that serve the provision of information and entertainment, but educational functions are still very limited (Subejo et al., Citation2018).

The media is a powerful medium for promoting various development sectors in rural areas. The results of the study show that 90% of people in Nanded (rural India) listen to the radio everyday. Some of the media that have an influence on rural development include TV, radio, the Internet and smartphones. Although electronic media has generally been used by rural communities, electronic media has not played an effective role in disseminating agricultural information (Yadav, Citation2015). Some of the causes of the low use of electronic media for agriculture are the lack of compatibility of innovations delivered with local conditions, the lack of appropriate language in delivery, the cost of electronic media which is quite expensive, experts in the field of agriculture do not want to use electronic media and the lack of financial support for the development of electronic media for agricultural extension. from the government. If these obstacles can be overcome, the opportunities and prospects for using communication information technology to support the success of agricultural development will be even better in the future.

6. Conclusions

Salak fruit as a plantation product which indicates the origin of Indonesia so that it can compete in the global market, it must start with, first, legal protection measures. Legal protection based on Article 22 TRIPS has provided legal protection for communal intellectual property, one of which is the protection of GIs. Of course, it is not enough to regulate it through the Law on Marks and GI, more than that, it must be specifically regulated (sui generis) as practiced by many countries. The second is to make maximum use of preservation technology, so that the shelf life of salak fruit can last up to 30 days. Assuming that the zalacca fruit can last up to 30 days, it is hoped that salak fruit exports will not only reach the Southeast Asian market, but also penetrate the European market. The three countries must reconsider how communication information technology can be conveyed properly to salak farmers in regions by understanding the characteristics and local content that each region is different, especially in terms of language. Agricultural experts must be able to convey the results of their research in a language understood by farmers, not in language that is too “scientific” but not understood by farmers. Including financial support for the development of electronic media for agricultural extension from the government.

Author contributions

In writing this article, Taufik H. Simatupang, Sri Hartini, Desty Anggie Mustika and Ady Purwoto contributed to the conception, research design, analysis, data interpretation and preparation of the paper. Muhar Junef, Ahmad Sanusi and Firdaus contributed to data analysis and interpretation. Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho, Josefhin Mareta, Ahmad Jazuli and Insan Firdaus contributed to data interpretation and preparation of the paper. All authors express their approval for the final version of the paper and are responsible for all aspects contained therein.

Acknowledgements

The results of this research are the result of independent research carried out by the author using document/literature studies in the form of primary, secondary, and tertiary legal materials. On this occasion, the author would like to thank BRIN and Ibn Khaldun University where the author works as a researcher and lecturer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Taufik H. Simatupang

Taufik H. Simatupang is a researcher at the Research Center for Law, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), He is a Doctor of Law from Padjadjaran University in 2023. Has published the results of his research in International Journals and National Journals. His areas of expertise include civil law, family law, child custody law, intellectual property law, and copyright.

Sri Hartini

Sri Hartini is a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Dean of the Faculty of Law, Ibnu Khaldun University (UIKA) Bogor with a specialization in Criminal Law. Dr. Since March 2024, Sri Hartini has been confirmed as Professor of Law at UIKA. Ady Purwoto is also a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Head of the Legal Studies Program, Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in Child Protection Law, while Desty Anggie Mustika is a lecturer at the Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in State Law. Since February 2024, Desty Anggie Mustika has obtained a Doctor of Law degree from Borobudur University.

Desty Anggie Mustika

Sri Hartini is a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Dean of the Faculty of Law, Ibnu Khaldun University (UIKA) Bogor with a specialization in Criminal Law. Dr. Since March 2024, Sri Hartini has been confirmed as Professor of Law at UIKA. Ady Purwoto is also a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Head of the Legal Studies Program, Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in Child Protection Law, while Desty Anggie Mustika is a lecturer at the Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in State Law. Since February 2024, Desty Anggie Mustika has obtained a Doctor of Law degree from Borobudur University.

Ady Purwoto

Sri Hartini is a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Dean of the Faculty of Law, Ibnu Khaldun University (UIKA) Bogor with a specialization in Criminal Law. Dr. Since March 2024, Sri Hartini has been confirmed as Professor of Law at UIKA. Ady Purwoto is also a Doctor of Law, lecturer, and Head of the Legal Studies Program, Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in Child Protection Law, while Desty Anggie Mustika is a lecturer at the Faculty of Law, UIKA Bogor, specializing in State Law. Since February 2024, Desty Anggie Mustika has obtained a Doctor of Law degree from Borobudur University.

Muhar Junef

Muhar Junef is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Environmental Law and Natural Resources. Ahmad Sanusi is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Criminal Law, while Firdaus is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Human Rights Law, Vulnerable Groups and Gender.

Ahmad Sanusi

Muhar Junef is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Environmental Law and Natural Resources. Ahmad Sanusi is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Criminal Law, while Firdaus is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Human Rights Law, Vulnerable Groups and Gender.

Firdaus

Muhar Junef is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Environmental Law and Natural Resources. Ahmad Sanusi is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Criminal Law, while Firdaus is a researcher at the Research Center for Law BRIN specializing in Human Rights Law, Vulnerable Groups and Gender.

Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho

Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho, Josefhin Mareta, Ahmad Jazuli and Insan Firdaus are researchers at the Research Center for Law BRIN who specialize in the field of Intellectual Property Rights.

Josefhin Mareta

Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho, Josefhin Mareta, Ahmad Jazuli and Insan Firdaus are researchers at the Research Center for Law BRIN who specialize in the field of Intellectual Property Rights.

Ahmad Jazuli

Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho, Josefhin Mareta, Ahmad Jazuli and Insan Firdaus are researchers at the Research Center for Law BRIN who specialize in the field of Intellectual Property Rights.

Insan Firdaus

Trisapto Wahyudi Agung Nugroho, Josefhin Mareta, Ahmad Jazuli and Insan Firdaus are researchers at the Research Center for Law BRIN who specialize in the field of Intellectual Property Rights.

References

- (2009). https://www.antaranews.com/berita/139596/buah-salak-indonesia-dipasarkan-sebagai-salak-thailand

- (n.d). https://www.gosumut.com/artikel/opini/2019/10/02/turun-naik-nasib-kota-salak

- Adebola, T. (2022). The legal construction of geographical indications in Africa. JWIP, 1–, 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12255

- Astuti, A. W., Darsono., & T., Sulhadi. (2020). Ekstrak Tumbuhan Putri Malu sebagai Bahan Pengawet Alternatif Alami Buah Salak. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Pascasarjana UNNES, 88–13.

- Campfens, E. (2020). Whose cultural objects? Introducing heritage title for cross-border cultural property claims. Netherlands International Law Review, 67(2), 257–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40802-020-00174-3

- Carugno, G. (2018). How to protect traditional folk music? Some reflections upon traditional knowledge and copyright law. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 31(2), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-017-9536-7

- Ceccobelli, S., Ciancaleoni, S., Lancioni, H., Veronesi, F., Albertini, E., & Rosellini, D. (2019). Genetic distinctiveness of a protected geographic indication lentil landrace from the Umbria region, Italy, over 20 years. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 66(7), 1483–1493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-019-00799-1

- Cecep Kusmana, A. H. (2015). Keanekaragaman Hayati Flora Indonesia. Jurnal Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Alam Dan Lingkungan, 5(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.19081/jpsl.5.2.187

- Cheng, L., & Yuan, Y. (2021). Intellectual property tools in safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: A Chinese perspective. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(3), 893–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09732-7

- Covarrubia, P. (2019a). Geographical indications of traditional handicrafts: A cultural element in a predominantly economic activity. IIC - International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 50(4), 441–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-019-00810-3

- Das, K. (2010). Prospects and challenges of geographical indications in India. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 13(2), 148–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2009.00363.x

- Davies, I. (1998). The protection of geographic indications. Journal of Brand Management, 6(1), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1998.46

- De Clippele, M. (2021). Does the law determine what heritage to remember? International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(3), 623–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09811-9

- Fernandes, F. A. N., Rodrigues, S., Law, C. L., & Mujumdar, A. S. (2011). Drying of exotic tropical fruits: A comprehensive review. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 4(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-010-0323-7

- Ferrazzi, S. (2021). The notion of cultural heritage in the International field: Behind origin and evolution of a concept. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(3), 743–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09739-0

- Gangjee, D. S. (2017). Proving provenance? Geographical indications certification and its ambiguities. World Development, 98, 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.009

- Hanekom, J., & Barker, R. (2016). Theoretical criteria for online consumer behaviour: web-based communication exposure and internal psychological behavioural processes approaches. Communicatio, 42(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2016.1140665

- Hanekom, J., Barker, R., & Angelopulo, G. (2007). A theoretical framework for the online consumer response process. Communication, 33(2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500160701685441

- Hari, A. S., & Raju, K. D. (n.d). (2022). Free trade agreements and geographical indications standards in Asia. In N. S. Bhattacharya (Ed.), Geographical indication protection in India. Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4296-9_3

- Haryanto, A. (2015). Faktor Geografis dan Konsepsi Peran Nasional sebagai Sumber Politik Luar Negeri Indonesia. Jurnal Hubungan Internasional, 4(2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.18196/hi.2015.0074

- Hoang, G., & Nguyen, T. T. (2020). Geographical indications and quality promotion of agricultural products in Vietnam: An analysis of government roles. Development in Practice, 30(4), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1729344

- Huysmans, M. (2022). Exporting protection: EU trade agreements, geographical indications, and gastronationalism. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 979–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1844272

- Indications, P. of G. I. in A. countries: C. and challenges to awakening sleeping G. (2020). Protection of Geographical Indications in ASEAN countries: Convergences and challenges to awakening sleeping Geographical Indications. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12155

- Kamperman Sanders, A. (2010). Incentives for and protection of cultural expression: Art, trade and geographical indications. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 13(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2009.00382.x

- Kireeva, I., & O’Connor, B. (2010a). Geographical indications and the TRIPS agreement: What protection is provided to geographical indications in WTO members? The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 13(2), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2009.00374.x

- Kusuma, P. H., & Roisah, K. (2022). Perlindungan Ekspresi Budaya Tradisional dan Indikasi Geografis: Suatu Kekayaan Intelektual Dengan Kepemilikan Komunal. Jurnal Pembangunan Hukum Indonesia, 4(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.14710/jphi.v4i1.107-120

- Lane Keller, K. (2001). Mastering the marketing communications mix: Micro and macro perspectives on integrated marketing communication programs. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(7-8), 819–847. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725701323366836

- Leong, L. P., & Shui, G. (2002). An investigation of antioxidant capacity of fruits in Singapore markets. Food Chemistry, 76(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00251-5

- Leontowicz, H., Leontowicz, M., Drzewiecki, J., Haruenkit, R., Poovarodom, S., Park, Y.-S., Jung, S.-T., Kang, S.-G., Trakhtenberg, S., & Gorinstein, S. (2006). Bioactive properties of snake fruit (Salacca edulis Reinw) and mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) and their influence on plasma lipid profile and antioxidant activity in rats fed cholesterol. European Food Research and Technology, 223(5), 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-006-0255-7

- Lestari, R., Keil, S. H., & Ebert, G. (2001). Variation in fruit quality of different salak genotypes (Salacca zalacca (Gaert.) Voss) from Indonesia. In Deutscher Tropentag—Technological and Institutional Innovations for Sustainable Rural Develop_ment.

- Marie-Vivien, D. (2008). From plant variety definition to geographical indication protection: A search for the link between basmati rice and India/Pakistan. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 11(4), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2008.00341.x

- Marie-Vivien, D. (2020). Protection of geographical indications in ASEAN countries: Convergences and challenges to awakening sleeping geographical indications. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 23(3-4), 328–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12155

- McHugh, P., & Perrault, E. (2022). Of supranodes and socialwashing: network theory and the responsible innovation of social media platforms. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2135236. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2135236

- Novi, P. A. E., Djuara, P., & Rangkuti, L. (2014). Penggunaan Internet Dan Pemanfaatan Informasi Pertanian Oleh Penyuluh Pertanian Di Kabupaten Bogor Wilayah Barat. Jurnal Komunikasi Pembangunan, 12(2), 104–109.

- Nyagadza, B., & Mazuruse, G. (2021). Embracing public relations (PR) as survival panacea to private colleges’ corporate image & corporate identity erosion. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1974179

- Quthni Effida, D. (2019). Tinjauan Yuridis Indikasi Geografis Sebagai Hak Kekayaan Intelektual Non-Individuak (Komunal). Jurnal Ius Civile, 3(2), 58–71.

- Radhika, A. M., Thomas, K. J., & Raju, R. K. (2021). Geographical indications as a strategy for market enhancement-lessons from rice GIs in Kerala. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 24(3-4), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12189

- Raustiala, K., & Munzer, S. R. (2007). The global struggle over geographic indications. European Journal of International Law, 18(2), 337–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chm016

- Sabarisman, I., Suyatma, N. E., Ahmad, U., & Taqi, F. M. (2015). Aplikasi Nanocoating Berbasis Pektin dan Nanopartikel ZnO untuk Mempertahankan Kesegaran Salak Pondoh. Jurnal Mutu Pangan: Indonesian Journal of Food Quality, 2(1), 50–56. https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/jmpi/article/view/27869

- Schuiling, D. L., J. P. M. (1991). Salacca zalacca (Gaertener) Voss. In: Verheij, E.W.M. &. E. Coronel (Eds.). Edible fruits and nuts. Nederlands, Pudoc Wageningen. Plant Resources of South-Eas Asia (PROSEA).

- Setiawan, B., Sulaeman, A., Giraud, D. W., & Driskell, J. A. (2001). Carotenoid content of selected Indonesian fruits. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 14(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfca.2000.0969

- Sikundla, T., Mushunje, A., & Akinyemi, B. E. (2018). Socioeconomic drivers of mobile phone adoption for marketing among smallholder irrigation farmers in South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1505415. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1505415

- Simatupang, T. H. (2023). 3 Langkah Perlindungan Indikasi Geografis Sebagai Bagian Dari Kekayaan Intelektual Komunal Melalui Perluasan Konsep Defensive Dan Positive Protection. Jurnal Penelitian Hukum De Jure, 23(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.30641/dejure.2023.V23.101-114

- Singh, G., Sharma, K., Dawer, S., Rana, S., Soni, R., Singh, V. K., & Sinha, R. P. (2023). Horticultural geographical indications of India: Botanical aspect. Vegetos, Das 2009, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-023-00684-4

- Subejo, S., Wati, R. I., Kriska, M., Akhda, N. T., Kristian, A. I., Wimatsari, A. D., & Penggalih, P. M. (2018). Akses, Penggunaan Dan Faktor Penentu Pemanfaatan Teknologi Informasi Dan Komunikasi Pada Kawasan Pertanian Komersial Untuk Mendukung Ketahanan Pangan Di Perdesaan Yogyakarta. Jurnal Ketahanan Nasional, 24(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.22146/jkn.30270

- Subejo. (2011). Babak Baru Penyuluhan Pertanian dan Pedesaan. Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Pertanian, 7(1), 61–70.

- Vittori, M. (2010). The International Debate on Geographical Indications (GIs): The point of view of the global coalition of GI producers—oriGIn. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 13(2), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2009.00373.x

- Yadav, K. B. (2015). A critical study and analysis of electronic media and rural development. International Journal of English Language, Literature, and Humanities, 3(9).

- Yaseen, M., Ahmad, M. M., Soni, P., Kuwornu, J. K. M., & Saqib, S. E. (2023). Factors influencing farmers’ utilisation of marketing information sources: Some empirical evidence from Pakistan. Development in Practice, 33(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2021.1911941

- Zhang, L., & Bruun, N. (2017). Legal transplantation of intellectual property rights in China: Resistance, adaptation and reconciliation. IIC - International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 48(1), 4–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-016-0542-1