?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study aims to investigate the relationship between public governance and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) while also examining the impact of national income per capita on this association. This study covers a decade-long period from 2012 to 2021 and involves 180 countries from various regions, including America, Asia Pacific, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe Central Asia, and Western Europe. To analyze the extensive dataset, which comprises 1768 data points, the study used the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) method. The research findings suggest that all aspects of public governance, such as voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law, and control of corruption, significantly influence the perception of corruption. This indicates that good governance practices can effectively reduce corruption. Interestingly, the impact of income per capita is not uniform across all dimensions of governance and the CPI. Instead, the study reveals that stricter rule of law and anti-corruption measures are more influential in wealthier nations, highlighting the importance of proper resources and infrastructure in eradicating corrupt practices. These insights are particularly valuable for policymakers, government officials, and international organizations involved in promoting good governance and fighting corruption. The results of this study can be used to formulate effective policies and strategies for strengthening governance practices, reducing corruption, and ensuring a fair and just society.

1. Introduction

Corruption is a persistent and widespread problem that has stained the face of human society (Alatas, Citation2015). Its negative impact can be observed in many spheres, including cultural, economic, and political landscapes. Corruption can take various forms, such as the offer or acceptance of bribes, embezzlement of funds, nepotism, or cronyism (Kingsly, Citation2015; Shah et al., Citation2023). This pervasive problem caused by corruption ultimately weakens the social fabric and undermines the prospects of nations, often leading to a breakdown of trust in institutions and the erosion of public confidence (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Dhillon & Nicolò, Citation2023). Corruption, which refers to the misuse of power for personal gain, has a detrimental impact on society (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Salihu, Citation2022). The pervasive presence of corruption in society poses a serious threat to economic growth and development (Trabelsi, Citation2024). Furthermore, corruption undermines the trust that people have in their public institutions and erodes the legitimacy of the government in the eyes of its citizens (Peerthum & Luckho, Citation2021; Tu, Citation2023). When public officials prioritize their own interests over those of the public, it leads to the breakdown of social and economic systems, ultimately affecting the well-being of the entire community (Mauro, Citation1995; Tanzi, Citation1998). The detrimental impact of corruption cannot be overlooked; therefore, it is imperative to conduct a thorough investigation into its root causes. Furthermore, it is crucial to identify viable solutions to prevent corruption to avoid severe repercussions that may arise as a result of its occurrence.

The concept of public governance has received significant attention in academic discourse as governing in an increasingly interconnected world has become more complex for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners. Public governance involves managing public resources and formulating policies that affect how the government interacts with society (Bovaird & Löffler, Citation2015; Löffler, Citation2015; Osborne, Citation2006). The proper implementation of key components of public governance, such as transparency, accountability, and citizen participation, can act as powerful deterrents against corrupt practices. By ensuring that decision-making processes are open and accessible to all, holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions, and actively engaging citizens in the decision-making process, we can create a culture of integrity and trust that prevents corruption from taking root and spreading (Devas & Grant, Citation2003). Effective public governance plays a vital role in promoting social welfare and sustainable development, encouraging citizens to participate in public decision-making actively, and enhancing the strength of institutions (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Handoyo & Fitriyah, Citation2018; Jäntti et al., Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2019). In contrast, poor governance, characterized by weak or absent oversight mechanisms, can create an environment in which corruption thrives and goes unchecked (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Farazmand et al., Citation2022).

Public governance refers to various mechanisms, cultural norms, and institutional structures that shape power within a nation. It encompasses a range of activities and practices, including policymaking, regulation, public service delivery, and management of public resources (Handoyo, Citation2023). The importance of effective governance practices in reducing corruption is well documented. Better governance can lead to a more transparent and accountable public sector, whereas weak governance can undermine public trust and harm societal well-being. Multiple studies have suggested that countries with better governance practices have lower corruption levels (Doig et al., Citation2005; Gaventa & McGee, Citation2013; Rose-Ackerman, Citation1999). This correlation is supported by Kaufmann et al. (Citation2011), those who propose that effective governance practices are inversely related to corruption levels. However, the complex interplay between governance and corruption underscores the need for a careful examination of governance structures and their impact on corruption levels.

Scholars and policymakers have identified the need for governance models that prioritize transparency, accountability, and legal integrity in the battle against corruption (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Grundy et al., Citation2022; Salleh & Matsham Heidecke, Citation2019). These practices entail making government activities open and accessible to the public, holding public officials accountable for their actions, and ensuring that all legal procedures and regulations are followed. By implementing such practices, there is a greater chance of creating a public sector that operates with more transparency and responsibility, which in turn reduces opportunities for corrupt practices to flourish. Grindle (Citation2007) argues that emphasizing these values in governance models is a promising approach to addressing corruption. Despite the promise of governance models that prioritize transparency, accountability, legality, and integrity, a more in-depth understanding of their intricacies is necessary. To achieve this, it is crucial to delve into specific governance practices that have proven most effective in reducing corruption. Additionally, it is important to consider contextual factors that may impact the success of these practices, such as cultural, political, and economic influences. By conducting further research on these topics, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of how public governance models and country-specific factors can reduce corrupt practices.

The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is a highly regarded tool that provides rankings of countries according to perceived levels of corruption in the public sector (Alfaro, Citation2022). This index was developed by Transparency International, a global organization that aims to promote transparency, accountability, and integrity in public institutions (Puiu, Citation2023). The CPI is an essential tool for policymakers, researchers, and activists who seek to understand the state of corruption worldwide and work towards creating more transparent and accountable systems of governance (Alfaro, Citation2022; Puiu, Citation2023). As a widely recognized measure, the CPI offers unique insights into state and corruption trends across countries (Lambsdorff, Citation2007a). The CPI is based on the opinions of experts and businesspeople and provides valuable insights into the state of public-sector corruption (Alfaro, Citation2022). To fully understand the nuances of corruption in various countries and how they relate to the actual state of public governance, it is imperative to delve deeper than mere surface-level observations. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the intricate relationship between CPI scores and the prevalence of corruption, it is crucial to conduct an in-depth analysis that takes into account various factors and variables. This approach allows us to gain a more accurate and detailed insight into the subject matter.

The relationship between public governance and corruption has been a captivating topic for many scholars and researchers (Di Pietra & Melis, Citation2016; Monteduro et al., Citation2016; Salihu, Citation2022). One school of thought proposes that a country's per capita income can substantially impact the prevalence of corruption within that country. As income levels increase, individuals may feel less compelled and motivated to engage in corrupt practices, resulting in a reduction in their overall level of corruption. This suggests a link between a country's economic prosperity and its ability to maintain a transparent and fair public governance system (Gyimah-Brempong, Citation2002; Hall et al., Citation2020; Treisman, Citation2007). It is essential to understand that the commonly held notion that higher income levels lead to lower levels of corruption is not always true. Several countries with high levels of economic prosperity have a lower Corruption Perception Index (CPI), indicating that the relationship between income and corruption may be more complicated than initially thought. This observation suggests that there could be an inverse correlation between income and corruption, whereby a decline in corruption levels may lead to an increase in income levels (Paldam, Citation2002). These discoveries bring to light the intricate and multifaceted interplay between a country's income and the level of corruption. They suggest that, while income may play a role in influencing corruption rates, other factors, such as political and cultural dynamics, can equally contribute. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further studies to verify the credibility and relevance of the existing research gap in comprehending the complex nature of corruption in different countries.

In the past few years, there has been a growing interest in understanding the relationship between public governance and the perception of corruption. This interest has resulted in extensive research in both academic and practical spheres. However, despite the abundance of research on governance and corruption, there is still a significant gap in our understanding of how these two elements are connected. To address this gap, this study seeks to conduct a comprehensive analysis of how the quality of public governance influences perceptions of corruption. By exploring this connection, this research aims to provide unique and valuable insights into the fields of business, management, and accounting. The findings of this study could have significant implications for policymakers, organizations, and society as a whole in terms of improving public governance and reducing corruption.

This investigation is highly relevant due to the recognition that corruption is a significant obstacle to economic growth, political stability, and good governance. While previous research has made some progress in understanding the causes and effects of corruption, there has been relatively little focus on the specific impact of governance practices on the national level in association with the corruption perception index. This lack of attention is particularly significant in the context of the increasing emphasis on transparency, accountability, and efficiency in public administration as strategies for tackling corruption. Therefore, this investigation aims to shed light on the relationship between public governance practices and corruption perception and contribute to the ongoing efforts to combat corruption and promote good governance on the national level.

Distinctively, this study employs a longitudinal data panel, leveraging a multi-dimensional analysis that encompasses various governance indicators to assess their collective and individual impact on the Corruption Perception Index. By utilizing an extensive dataset, the study provides a robust investigation of the dynamic interplay between governance and corruption over time. Additionally, the study investigates how national income per capita moderates these relationships, providing valuable insights into the interaction between economic factors and governance in influencing corruption perceptions. By doing so, it not only enriches the existing literature with empirical evidence but also sheds light on the complex mechanisms through which governance practices influence corruption perception. Furthermore, the research introduces a novel conceptual framework that integrates theoretical perspectives from the fields of public administration, political science, economics, and business ethics, offering a holistic understanding of the governance-corruption nexus.

This study is significant in three primary ways. Firstly, it provides valuable insights into the relationship between public governance and corruption perception, which is a relatively underexplored area in the literature. The study's empirical findings help to shed light on how public governance practices can influence perceptions of corruption. Secondly, the study introduces a comprehensive analytical model that can serve as a foundation for future research endeavors exploring similar themes. This model's development is a significant contribution to the literature, as it provides a framework to guide future research studies. Lastly, the research identifies the specific governance practices that have a substantial impact on corruption perception. By doing so, it offers practical implications for policymakers and public administrators seeking to devise effective anti-corruption strategies. The study's findings provide valuable guidance on which governance practices are most effective in reducing corruption perception and provide insights into how these practices can be implemented in practice.

This research provides a novel perspective on a pressing issue that has far-reaching implications for societies worldwide. It offers a valuable contribution to academic discourse, shedding new light on the challenges of establishing transparent, accountable, and effective governance systems across the globe. The study is expected to generate significant interest among a diverse range of readers, including academicians, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Its primary objective is to foster a deeper understanding of the intricate relationship between public governance and the perception of corruption and to advance the development of evidence-based policy solutions to tackle this complex problem.

2. Theoretical and conceptual framework

2.1. Principal agent theory

The Principal-Agent Theory is a valuable framework for analyzing corruption within public governance, especially as it relates to the Corruption Perception Index. This theory primarily addresses the complexities inherent in relationships where one party (the principal) delegates responsibilities to another (the agent), particularly in the context of public administration. In this case, citizens and their elected representatives act as principals, while public officials and bureaucrats serve as agents. The theory originated from the seminal work of Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976), emphasizing the challenges of information asymmetry, where agents possess more information than principals, which can lead to a misalignment of interests. These discrepancies can create an environment conducive to corruption, as agents may prioritize personal gains over public welfare and engage in activities such as bribery, embezzlement, and fraud (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Martinsson, Citation2021).

The Principal-Agent Theory is not only helpful in understanding public sector corruption but also provides practical mechanisms for mitigating it. The strategies that stem from this theory are aimed at realigning the interests of agents with those of principals, enhancing transparency, and reducing information asymmetries. For example, increasing transparency in governmental processes and financial transactions can significantly reduce corrupt practices by bridging the information gap between public officials and citizens (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Farazmand et al., Citation2022). Additionally, establishing robust oversight mechanisms such as independent anti-corruption bodies and audit institutions can enforce accountability and deter corrupt behavior (Heinrich & Brown, Citation2017). These measures can help to reduce public sector corruption.

Effective public governance can play a vital role in reducing corruption by creating incentive structures that are in line with the interests of the public (Handoyo & Fitriyah, Citation2018; Martinsson, Citation2021; Zhang, Citation2018). This can be accomplished by offering rewards based on performance, promoting career advancements based on merit, and enforcing strict penalties for those who engage in misconduct. In addition to this, it is essential to create an atmosphere of integrity within public institutions. This involves implementing formal rules and regulations while also promoting informal norms and values that discourage corrupt behavior. By fostering an environment where ethical behavior is highly valued and encouraged, corruption can be effectively mitigated (Feldman, Citation2017; Hauser, Citation2019; Manara et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Institutional theory

Institutional Theory provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the intricate relationship between public governance and the Corruption Perception Index, emphasizing the critical role that institutions, whether formal or informal, play in shaping corruption (Melgar et al., Citation2010; Pillay, Citation2014; Xiao et al., Citation2020). According to this theory, the strength, transparency, and accountability of institutions are crucial factors that determine the extent to which corruption is prevalent within a society (Hapuhennedige et al., Citation2020). Institutions form the foundation upon which economic and political interactions are built, it becomes evident that the integrity and effectiveness of these institutions are directly tied to corruption levels (Aidt, Citation2003; Campos & Giovannoni, Citation2017; Fjelde & Hegre, Citation2014). Weak institutions, which are characterized by inadequate enforcement of laws, opacity, and a lack of accountability mechanisms, provide an environment in which corrupt practices may flourish (Azoro et al., Citation2021; Farazmand et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, strong institutions with robust legal frameworks, transparent operations, and effective oversight can significantly reduce opportunities for corruption (Asaduzzaman & Virtanen, Citation2021; Handoyo & Fitriyah, Citation2018).

The theory emphasizes the crucial role played by informal institutions such as societal norms, values, and culture, in shaping the behavior of individuals and organizations with regards to corruption (Pena López & Sánchez Santos, Citation2014). It suggests that in societies where corruption is widespread or expected, formal anti-corruption measures may struggle to make a significant impact. Therefore, it is essential to adopt a two-pronged approach to combat corruption that addresses both the formal structures of governance and the informal cultural norms that influence societal behavior (Tu, Citation2023; Westerwinter et al., Citation2021). By doing so, it is possible to create a culture of integrity that discourages corrupt practices and promotes transparency in all spheres of society. This approach recognizes the importance of cultural context and the impact of social norms on individual and group behavior and seeks to leverage these factors in the fight against corruption.

Strategies aimed at addressing corruption based on institutional theory provide a diverse range of interventions. One of the most effective interventions is the creation and enforcement of strict legal frameworks that clearly outline corrupt activities and the appropriate penalties for such actions (Martinsson, Citation2021; Pillay, Citation2014). This creates a strong disincentive against corrupt activities. In addition, promoting transparency and accountability in public administration through initiatives such as open government and financial disclosures by public officials can significantly reduce the opacity that often enables corrupt activities (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., Citation2023; Erkkilä, Citation2020). By implementing these interventions, we can combat corruption and promote a culture of accountability and fairness in public institutions (Brenya Bonsu et al., Citation2023; Min, Citation2019)

To effectively tackle corruption, it is essential to have formal mechanisms in place. However, promoting public participation in governance processes and empowering civil society can also be helpful. Civil society organizations can act as watchdogs, monitoring public institutions and advocating for greater accountability and integrity (Gray et al., Citation2006; Grimes, Citation2013; Williamson et al., Citation2022). By building a culture that rejects corruption, we can ensure its sustainable eradication. Creating this culture requires a shift in societal attitudes toward corruption, which can be done through educational reforms, public awareness campaigns, and the cultivation of ethical leadership (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Pozsgai-Alvarez, Citation2022). By doing so, we can create a society that values transparency, accountability, and integrity and is committed to fighting corruption.

2.3. Public choice theory

Public Choice Theory provides a nuanced understanding of the relationship between public governance and the Corruption Perception Index by conceptualizing politicians and bureaucrats as rational, self-interested actors similar to participants in economic markets (Dell'Anno, Citation2020; Melgar et al., Citation2010; Mungiu-Pippidi & Dadašov, Citation2016). This theory is based on the economic analysis of political decision-making and explains how the incentives within public institutions can lead to corrupt behavior. The theory suggests that when there are not enough checks, balances, and competitive pressures, government officials may exploit their power for personal gain, which can result in practices such as rent-seeking, policy manipulation, and outright corruption (Campos & Giovannoni, Citation2017; Etzioni‐Halevy, Citation1989).

Public Choice Theory highlights the significance of aligning the interests of public officials with the broader public good by strategically structuring incentives and institutional arrangements (Brunjes, Citation2019). To achieve this alignment, it is essential to reinforce institutional checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power, ensuring accountability across different branches of government and independent bodies (Alemanno & Spina, Citation2014; Holcombe, Citation2018). The dispersion of power acts as a safeguard against the abuse of authority and facilitates mechanisms to hold public officials accountable (Edwards & Hupe, Citation2012; Emerson et al., Citation2011).

Furthermore, according to the theory, promoting political competition can act as a strong deterrent against corrupt practices (Campos & Giovannoni, Citation2017; Perlman & Sykes, Citation2018). This is because when there is a competitive political environment, politicians are more likely to refrain from engaging in corrupt activities due to the increased risk of losing support from the electorate (Dincer & Johnston, Citation2016). The presence of viable alternatives for the electorate makes it more costly for politicians to engage in corrupt practices. This competitive dynamic also enhances the accountability of public officials, as they are aware of the consequences of being caught engaging in corrupt activities. Fostering a competitive political environment is a critical step in reducing corruption and improving accountability among public officials.

Public Choice Theory is a framework that emphasizes the essential role of citizen engagement and oversight in preventing corrupt practices (Campos & Giovannoni, Citation2017). This theory suggests that citizens must be actively involved in the political process and that civil society organizations and media must operate with constant vigilance to safeguard against corruption (Ceschel et al., Citation2022; Görtz, Citation2022). This perspective uses the power of organized public oversight in exposing and deterring corruption (Lyra et al., Citation2022). Thus, when the populace is empowered to participate in the political process and has access to information, it becomes easier to hold public officials accountable and prevent corruption from taking root (Bobbio, Citation2018; Park et al., Citation2022; Verdenicci & Hough, Citation2015).

2.4. Public governance

Public governance refers to the various structures, systems, and institutions that are in place to enable societies to effectively manage their affairs, allocate resources, and coordinate their actions manner (Rhodes & Osborne, Citation2002; Rhodes, Citation1996). This includes decision-making processes, administrative procedures, regulatory frameworks, and other mechanisms that are designed to promote transparency, accountability, and fairness in the way that public resources are used and managed. Public governance represents the traditions, institutions, and processes that determine how power is exercised, how stakeholders have their say, how decisions are made, and how citizens and other groups are involved in the decision-making processes (Kooiman, Citation1999, Citation2003). Effective public governance is essential for ensuring the well-being and prosperity of a society, as it enables individuals and organizations to work together towards common goals and to address shared challenges in a collaborative and constructive. It reflects a shift from traditional bureaucratic modes of governance to more complex, multi-actor networks of governance (Kooiman, Citation1993). Osborne (Citation2006) highlights the rise of the 'New Public Governance' (NPG) paradigm, which is characterized by a focus on governance beyond the state, including collaborations, partnerships, and networks. This move towards NPG underscores the need to understand governance as the product of interactions between public, private, and third-sector organizations. Moreover, NPG emphasizes the role of citizens and stakeholders in shaping governance outcomes and fostering accountability (Skelcher & Torfing, Citation2010).

The well-known public governance developed by the World Bank is Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project represents a comprehensive effort to quantify the quality of governance across over 200 countries. Developed by the World Bank Development Research Group, led by Daniel Kaufmann, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011). This initiative focuses on six broad dimensions of governance, offering a multi-faceted view of governance quality that is essential for both research and policy-making (World-Bank, Citation2024). The World Bank identifies six dimensions of public governance namely voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption (World-Bank, Citation2024). These indicators are based on data from more sources produced by various institutions, including survey institutes, think tanks, NGOs, international organizations, and private sector firms (World-Bank, Citation2024). Since 1996, the WGI have offered annual updates, making it one of the most extensive datasets on governance. This dataset is invaluable for a wide range of stakeholders, including international organizations, government bodies, the private sector, NGOs, and academia, who use it to analyze governance issues and develop policies aimed at enhancing governance and development outcomes.

The first dimension, Voice and Accountability, reflects the extent of citizens' participation in government selection, along with the freedoms of expression, association, and the press (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011; World-Bank, Citation2024). The Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism dimension evaluates countries' susceptibility to political instability and violence, including terrorism (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011; World-Bank, Citation2024). Government Effectiveness is assessed through the quality of public services, the independence of the civil service, and the government's policy-making and implementation capabilities (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011; World-Bank, Citation2024). The Regulatory Quality dimension examines the government's ability to create and implement sound policies and regulations that promote private sector development (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011; World-Bank, Citation2024). Further, the Rule of Law dimension gauges the strength of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the prevalence of crime and violence. Lastly, Control of Corruption measures the degree to which public power is exercised for private gain, encompassing both minor and major forms of corruption and the capture of the state by elites and private interests (Kaufmann et al., Citation2011; World-Bank, Citation2024). Good governance is central to sustainable development (Stojanović et al., Citation2016). The implementation of effective governance systems is a crucial aspect of ensuring that decisions made are sound and in the best interest of all stakeholders involved. Such systems also facilitate the efficient allocation and use of resources, resulting in optimal outcomes for the organization and its constituents. On the other hand, governance systems that are deficient in key areas can pave the way for corrupt practices, inefficient resource utilization, and a general lack of faith in the integrity and transparency of public institutions.

2.5. Corruption perception index

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is a pivotal global indicator, annually published by Transparency International, that ranks countries by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. The CPI is used to measure the level of corruption that is perceived to exist in the public sector of various countries around the world (Alfaro, Citation2022). The index is based on extensive research, data analysis, and expert assessments, making it a reliable and widely recognized metric for evaluating public sector transparency and accountability. By providing valuable insights into the prevalence of corruption, the CPI helps to promote good governance, strengthen institutions, and support sustainable economic development (Baumann, Citation2020; Gilman, Citation2018). The CPI was first launched in the year 1995 and is updated annually. It is a tool used to assess the levels of corruption within countries based on the perceptions of experts and the general public. The CPI is a comprehensive evaluation that utilizes a combination of surveys and assessments from different institutions, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the results. The index ranks countries based on their scores, which are assigned after aggregating the data collected from the surveys and assessments. The CPI is an essential resource for policymakers, researchers, and civil society organizations looking to understand and address corruption issues within countries. On a scale of 0 to 100, the score indicates the perceived level of public sector corruption, with 0 being highly corrupt and 100 being very clean (Batrancea et al., Citation2023; Ulman, Citation2014). The data sources used are based on the perceptions of businesspeople and country experts. A country's score is calculated as the average of all standardized scores available for that country, and scores are then used to rank countries (Lambsdorff, Citation2006).

The CPI data is collected from a number of reliable sources in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of a country's economic and political landscape. These sources include the World Bank's Country Policy and Institutional Assessment, the World Economic Forum's Executive Opinion Survey, and the Global Insight Country Risk Ratings. By drawing on these sources, the CPI is able to provide a nuanced and detailed understanding of a country's policy and institutional framework, as well as its overall economic and political risk profile (Budsaratragoon & Jitmaneeroj, Citation2020). The CPI, or Corruption Perceptions Index, is a tool that utilizes scores from various sources to provide a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of corruption levels in different countries. These sources may include surveys of experts, assessments by business professionals, and data from international organizations. By standardizing these scores, the CPI ensures that a consistent metric is applied across countries, enabling easier comparison and analysis of trends in corruption. This approach helps to promote transparency, accountability, and good governance while also facilitating the development of effective anti-corruption strategies (Hamilton & Hammer, Citation2018). The index has been designed to maintain high levels of reliability by adopting a rigorous approach. As a part of this approach, only those countries that have data from at least three sources are included in the index. This helps to ensure that a country's score is not unduly influenced by a single assessment or opinion, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the overall index (Lambsdorff, Citation2007b).

3. Empirical literature review and hypothesis development

3.1. Voice and accountability and corruption perception index

One of the core dimensions of public governance is Voice and Accountability (V&A), a metric that captures the level of civic engagement and participation in a nation's governance. The V&A metric considers the extent to which citizens can freely express their views, associate themselves with others, and access impartial media. It also evaluates the role of checks and balances in maintaining a democratic system that fosters transparency, accountability, and responsiveness to citizens' needs. Overall, the V&A metric provides valuable insights into the state of governance in a country and helps to identify areas for improvement (Kaufmann et al., Citation2010). A functioning V&A infrastructure often refers to an informed population, transparent governance, and diligent media. These elements work collaboratively to deter corrupt undertakings owing to the amplified risk of exposure and public criticism. Hence, nations scoring high on V&A might typically manifest better CPI scores, implying reduced perceived corruption (Lambsdorff, Citation2008).

A crucial aspect of accountability is the role played by the media. Consistent reporting by the media can lead to less corrupt activities and improve public perceptions. As a result, reinforced V&A may increase perceptions of corruption, even if actual corruption levels remain constant due to heightened awareness and investigation (Brunetti & Weder, Citation2003). Countries with high V&A scores typically have strong policies and executions that limit corruption in public services and government procurement. Rigorous accountability standards increase the likelihood of officials facing the consequences of corrupt actions, which serve as deterrents (Persson et al., Citation2013). Civil society organizations are crucial for monitoring government actions and serving as watchdogs to combat corruption. Their proactive stance highlights malfeasance and ensures that perpetrators face the consequences (Gaventa & McGee, Citation2013). Voice and Accountability and the Corruption Perception Index share a multifaceted relationship. Robust V&A mechanisms often correlate with decreased perceptions of corruption owing to their deterrent nature.

H1: Voice and accountability are positively associated with the corruption perception index.

3.2. Political stability and corruption perception index

Political stability is a crucial factor that determines the likelihood of a government being overthrown or destabilized by violent or unconstitutional methods. The World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators offer a comprehensive measurement of political stability, including an evaluation of the potential for politically motivated violence and terrorism. Countries with stable political environments tend to have low levels of violence and terrorism and a high degree of societal trust, all of which are hallmarks of political stability. Therefore, it is essential to maintain a stable political environment to ensure that a government operates effectively and serves its citizens (Kaufmann et al., Citation2010).

Political stability often provides a predictable policy environment that can deter corruption. Institutions often function more effectively in a stable environment, making enforcement of laws, including anti-corruption legislation, easier. This can affect a country's CPI ranking (Seldadyo & De Haan, Citation2006). High levels of perceived corruption can lead to political unrest and reduced stability. When corruption is perceived to be endemic, it can trigger protests, reduce trust in the government, and, in extreme cases, contribute to political instability (Treisman, Citation2000). On the other hand, in some cases, political stability might be maintained through authoritarian means that include suppressing information about corruption. In such scenarios, the CPI might show better results than actual figures due to limited reporting and fear of reprisals (Mungiu, Citation2006). Resources are often allocated more efficiently in politically stable countries, partly because political volatility does not distort decision-making. This could lower opportunities for corruption, thereby improving the CPI score (Alesina et al., Citation1996; Alesina & Perotti, Citation1996).

H2: Political stability is positively associated with the corruption perception index.

3.3. Government effectiveness and corruption perception index

Efficient government operations play a crucial role in preventing corruption. Such operations are characterized by streamlined processes, which ensure that bureaucratic systems function effectively, and transparent mechanisms, which enable citizens to hold public officials accountable. When a government operates efficiently, it creates fewer opportunities for corrupt activities, which in turn can improve a country's overall corruption perception index (CPI) score. An effective oversight mechanism can ensure that regulations comply, thereby reducing the likelihood of corrupt activities. Ultimately, a well-functioning bureaucratic system and an effective oversight mechanism are important measures that can help prevent corruption and promote a fair and just society (Evans & Rauch, Citation1999). When the perception of corruption is high, it can have detrimental effects on governmental effectiveness. This is because corrupt activities, such as misappropriation of funds and bribery, lead to resources being diverted from their intended purposes. This, in turn, results in a reduction in the overall quality of public services and can make it difficult to implement policies effectively. Therefore, it is important to ensure that corruption is minimized to maintain a strong and effective government that is able to serve its citizens to the best of its ability (Mauro, Citation1995, Citation1998).

High government effectiveness can bolster public trust in institutions. When citizens believe that their government is effective, they might perceive it as less corrupt, even if this is not necessarily true. Thus, public perception plays a pivotal role in the interplay between government effectiveness and CPI (Huther & Shah, Citation2000). Efficient policies and their rigorous implementation can reduce the opportunities for corruption. When policies are well-designed and effectively implemented, gaps that can be exploited for corrupt purposes are minimized. Moreover, when policies are clear, public officials have less discretion, which could further reduce corruption activities (Rose-Ackerman, Citation1999). Government Effectiveness and the CPI are intimately connected, and their relationship is reciprocal. While an effective government can reduce corruption, it can impede the achievement and maintenance of government effectiveness. Understanding this interplay is critical for policymakers seeking to improve governance and reduce corruption.

H3: Government effectiveness is positively associated with the corruption perception index.

3.4. Regulatory quality and corruption perception index

A regulatory system that is both effective and transparent can significantly reduce avenues for corrupt practices. When regulations are clear, well-defined, consistently enforced, and openly communicated, it becomes increasingly challenging for individuals or entities to engage in or benefit from corrupt activities. Such a system can help achieve a more just and equitable society, where everyone is held accountable for their actions and there are fewer opportunities for corruption to take hold. This can positively influence a nation's CPI score (Djankov et al., Citation2002). An environment riddled with cumbersome regulations, red tape, and arbitrary bureaucratic decisions can increase the temptation for businesses and individuals to resort to bribery or other corrupt means of expediting processes, thereby worsening the CPI score (Svensson, Citation2005).

An environment characterized by high regulatory quality often garners greater trust from businesses and the general population. When people perceive that regulations are fair and effectively implemented, their perception of corruption may be lower even if the actual level of corruption remains unchanged (Rodriguez et al., Citation2005). Quality regulations are often equipped with accountability mechanisms to ensure operational transparency. Such mechanisms reduce discretionary power that might be exploited corruptly and improve oversight, benefiting CPI ranking (Aidt, Citation2009). The correlation between regulatory quality and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is significant (Mujtaba et al., Citation2018). The implementation of effective regulations can serve as a powerful tool for curbing corrupt practices within a given system. By contrast, the perception of extensive corruption can erode public trust within the regulatory framework. For nations that strive to elevate their regulatory quality and improve their standing in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), it is vital to establish regulations that are open, equitable, and efficient while also being backed by a robust oversight mechanism. By doing so, countries can build a regulatory system that is not only effective but also transparent, which can inspire trust and confidence in the public.

H4: Regulatory quality is positively associated with the corruption perception index.

3.5. Rule of law and corruption perception index

The implementation of a strong rule of law is crucial to prevent corruption. Such a legal system is characterized by an independent and efficient judiciary, which acts as a deterrent against corrupt behavior. When legal institutions are robust, they increase their chances of detecting and prosecuting corrupt activities, leading to a higher likelihood of accountability for wrongdoings. Consequently, countries with strong legal systems tend to score higher on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), which is a testament to their commitment to transparency, accountability, and good governance (Dakolias, Citation1999). When a legal system is in place that upholds the Rule of Law, it allows contracts to be recognized and enforced more efficiently. This, in turn, mitigates the need for illegal practices, such as bribery or other corrupt means to secure business interests. As a result, it positively impacts the corruption perception index (CPI), which measures the level of perceived corruption in a given country. Therefore, a fair and unbiased legal system plays a vital role in promoting a healthy business environment that leads to sustainable economic growth.

Robust Rule of Law tends to enhance public trust in institutions. If citizens believe that their rights are protected and that disputes will be adjudicated fairly, they are likely to perceive lower levels of corruption, irrespective of the actual corruption levels (Buscaglia & Ulen, Citation1997). Conversely, pervasive corruption can erode the rules of law. When public officials, including those in the judiciary, are perceived as corrupt, the general populace may lose faith in the legal system, reducing adherence to the Rule of Law (Mungiu, Citation2006). The rule of law and corruption perception index (CPI) are closely connected. When a strong Rule of Law framework is in place, it can help prevent corrupt practices. However, if corruption is perceived as high, it can negatively impact the trust and effectiveness of legal institutions. This can, in turn, affect a country's efforts to improve its Rule of Law framework and standing in the CPI. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen legal institutions, ensure judicial independence, and build public trust in order to improve the Rule of Law and the CPI standing of a country.

H5: The rule of law is positively associated with the corruption perception index

3.6. Control of corruption and corruption perception index

Control of Corruption Index and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) are two measures that are closely associated with one another. A country with a robust system in place to manage and control corruption is more likely to score higher on the CPI, indicating that it is perceived as less corrupt. Both indices were designed to assess different aspects of corruption, with the CPI focusing on people's perceptions of corruption. By contrast, the Control of Corruption index examines the actual control mechanisms in place to combat corruption. These measures are crucial in identifying the weaknesses and strengths of a country's anti-corruption efforts and play a vital role in shaping policies designed to combat corruption (Lambsdorff, Citation2007b). The implementation of effective control measures can significantly influence the perceptions of the general public and experts. When these measures are visible and tangible, such as through judiciary verdicts, legislative actions, or public policies, they can have a positive impact on a state's corruption perception index (CPI) score. In other words, when a state takes concrete steps to combat corruption, this can be reflected in its CPI score, which, in turn, can improve its reputation and standing in the eyes of the international community (Doig et al., Citation2005).

The effective implementation of strong anti-corruption policies plays a crucial role in improving corruption control. When these policies are clearly visible, and their impact is tangible and measurable to the public and experts, they can significantly influence the perception of how well a country is managing corruption. This, in turn, can positively impact the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) score, which is a globally recognized indicator of a country's level of corruption. Therefore, it is vital to implement and enforce anti-corruption policies that are not only robust but also transparent and accessible to all (Seldadyo & De Haan, Citation2006). Although both indices revolve around corruption, they capture different nuances. Control of Corruption Index evaluates the actual measures and systems in place by a state to tackle corruption. However, the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) primarily focuses on the perception of corruption, which might not reflect the actual efforts taken by the state. Furthermore, perception can be influenced by external factors such as global narratives and media coverage (Treisman, Citation2007). The control of corruption and the corruption perception index (CPI) are closely intertwined, and their relationship is dynamic. Countries with effective measures to control corruption tend to have better perceptions of corruption both domestically and internationally. As such, corruption control is often seen as a key indicator of a country's overall governance and adherence to the rule of law. Conversely, countries with poor control over corruption tend to have low levels of trust in public institutions and high rates of bribery and other corrupt practices. Therefore, governments need to implement robust anti-corruption measures to foster a culture of transparency and accountability and to promote public trust in their institutions.

H6: Control of corruption is positively associated with the corruption perception index.

3.7. Moderating role of income per capita

Empirical and theoretical evidence suggests that robust public governance is inversely related to the level of corruption. Nations endowed with rigorous institutional frameworks, transparent mechanisms, and accountability provisions tend to be less susceptible to corrupt activities (Lambsdorff, Citation2007b). Nations with substantial income per capita possess enhanced fiscal wherewithal to channel investments into pivotal public sectors, such as education, the judiciary, and healthcare. Investing in these areas strengthens the foundation of public governance and reduces opportunities for corruption (Mauro, Citation1995). As income per capita increases, societal norms and expectations shift. Affluent societies tend to harbor heightened expectations concerning governance transparency, and exhibit diminished tolerance for corrupt practices (Treisman, Citation2007).

High-income per capita nations often have more robust institutional structures, better rules of law, and advanced public service mechanisms. These elements, in tandem, can mean that while good governance is expected, perceived corruption may be similar to fluctuations in governance quality (Lambsdorff et al., Citation2004). Low-income per capita may have less entrenched institutional systems. Even small enhancements in public governance can significantly shift perceptions of corruption. However, a lower threshold for corruption acceptance might exist because of socioeconomic challenges (Lambsdorff et al., Citation2004).

In countries with high income per capita, institutions might be better developed, and more resources might be available for effective governance. Moreover, the cost of engaging in corrupt practices may be higher in terms of potential penalties, both legal and social. Thus, the relationship between good governance and lower corruption may be stronger in these countries (Lambsdorff, Citation2007). Conversely, even if governance structures are in place in low-income countries, the lack of resources and perhaps a higher immediate necessity for personal gain may make the fight against corruption more challenging. The relationship between governance and corruption in these settings may be weaker or more complex (Charron et al., Citation2013).

H7: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between Voice and Accountability and the corruption perception index

H8: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between political stability and the corruption perception index

H9: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between government effectiveness and the corruption perception index

H10: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between regulatory quality and the corruption perception index

H11: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between the rule of law and the corruption perception index

H12: National income per capita positively moderates the relationship between control of corruption and the corruption perception index

4. Methodology

4.1. Population and sample

This comprehensive study delves into the governance practices of all nations that are part of The World Bank, with specific attention given to countries that have demonstrated strong scores in key areas, such as voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption, and the corruption perception index (CPI) between 2012 and 2021. The research is based on a carefully selected sample of countries that reflects a decade-long timeline, providing a detailed analysis of the governance practices in these countries and their impact on overall economic and social development.

4.2. Model Estimation and analysis

The study proposes that the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is the function of voice and accountability (VOACC), political stability (POLSTA), government effectiveness (GOVEC), regulatory quality (REQUAL), rule of law (RULAW), control of corruption (CONRUP) Considering the data is panel data, model estimation is constructed as follows:

Model 1

Model 1

In addition to proposing model estimation, as stated in Model 1, the study also proposes a model estimation that involves interaction with a moderating variable, namely income per capita (IPC). A model estimation that includes interactions with moderating variables was formulated as follows:

Model 2

Model 2

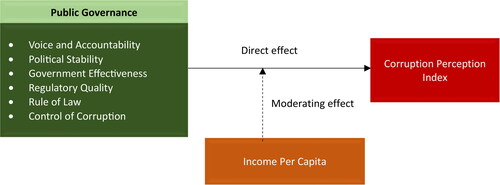

To obtain a better understanding of the research structure, provides a graphic visualization that highlights the key components of the research model and the relationships between them, as stated in Model Estimation 1 and Model Estimation 2.

We adopted Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to run analysis of Model Estimation 1 and Model Estimation 2. The application of GEE in our study represents a deliberate methodological choice aimed at addressing the inherent complexities of analyzing panel data, particularly when exploring the dynamic interplay between public governance, national income, and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) across multiple countries and over an extended period. The decision to utilize GEE is rooted in its capacity to offer robust estimates in the face of potential endogeneity issues, including those arising from omitted variable biases, measurement errors, and reverse causality (Molenberghs et al., Citation2019; Wang, Citation2014).

GEE is particularly adept at handling correlated response data that is typical in longitudinal and multi-site studies (Hanley et al., Citation2003; Wang et al., Citation2024). The GEE method extends generalized linear models (GLM) to accommodate correlated observations (Wilson et al., Citation2020), thereby enabling the analysis of repeated measures and clustered data commonly encountered in public governance construct and corruption perception index. One of the pivotal strengths of GEE lies in its ability to produce consistent and efficient parameter estimates without requiring strict assumptions about the underlying population distribution (Leung et al., Citation2009; Wang, Citation2014), making it particularly suited for the complex, multi-dimensional data our study encompasses.

Addressing the endogeneity concern, GEE facilitates the inclusion of within-group correlations and time-varying covariates, offering a mechanism to control for unobserved heterogeneity that might otherwise bias the estimates (Liu & Perera, Citation2023). By accounting for the correlation within countries over time, GEE helps to mitigate the impact of omitted variables that are constant within clusters but vary across them. This is critical in our context, where governance indicators and corruption perceptions may be influenced by unmeasured country-specific factors that evolve over the study period.

4.3. Variable operationalization and measurement

This study focuses on the Corruption Perception Index, which is used as a dependent variable to evaluate the level of corruption in a country. The study also explores various independent variables, such as voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption, which are believed to have a significant impact on corruption perception. Additionally, this study examines income per capita as a moderating variable, which is expected to influence the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. For a better understanding of the variables used in this study, refer to , which provides a detailed description of each variable.

Table 1. Variable operationalization.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive statistics of corruption perception index

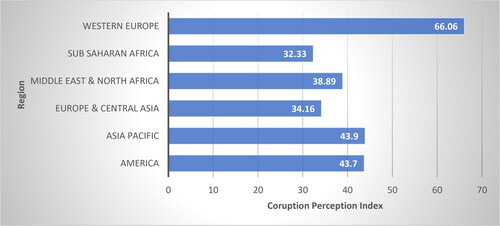

displays the perceptions of corruption across different regions of the world, such as America, Asia Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Europe. The Corruption Perception Index, which ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating lower levels of corruption, was used to measure these perceptions. While Western Europe is generally considered to have the lowest levels of corruption, other regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and Central Asia have been perceived to struggle with higher levels of corruption. It s fascinating that the scores within regions, particularly Asia, suggest that different countries within the same region experience corruption differently. These valuable insights can help shape governance and anti-corruption measures at a regional level.

Table 2. Corruption Perception Index by Region.

After examining the different global regions, it is evident that there are disparities in perceptions of corruption among them. Western Europe is recognized as having a minimal corruption perception, which is in stark contrast to the perception of corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Asia-Pacific region showed the most significant variation in perceptions, while Europe and Central Asia displayed the least variability. The Americas and Asia-Pacific have nearly identical average scores, but they differ in their range and elevated standard deviation, highlighting striking intra-regional disparities in corruption perceptions in the Asia-Pacific region. Sub-Saharan Africa revealed a worrying trend, with the lowest average CPI score indicating the highest perceived corruption. However, the score distribution in this region suggests a diverse perception of corruption among its nations, emphasizing that not all countries are perceived similarly. shows a graphical visualization of the average Corruption Perception Index based on the region.

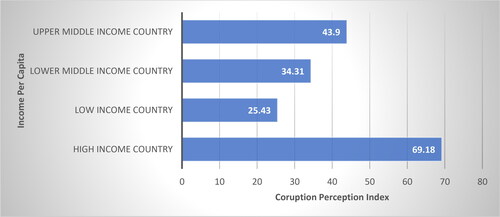

provides an insightful analysis of the relationship between a country's economic prosperity, measured by Income Per Capita, and perceived level of corruption. The data highlight a strong correlation between a nation's income level and its perceived corruption. Generally, countries with higher income levels tended to have lower perceptions of corruption, as evidenced by an average CPI score of 69.18. On the other hand, low-income countries exhibited a higher perception of corruption, as shown by an average CPI score of 25.43. This suggests that wealth may play a role in shaping perceptions of corruption. However, the variability in perceptions, as indicated by the standard deviations, indicates a more nuanced reality. Specifically, even among high-income countries, there is significant variation in corruption perceptions, indicating that wealth alone is not a guarantee of uniformly low corruption perceptions.

Table 3. Corruption Perception Index by Income Category.

Corruption becomes more significant in low-income countries, where there is a consistent and widespread perception of corruption, as indicated by the low average CPI score and relatively low standard deviation. Interestingly, a nuanced dynamic exists when evaluating middle-income nations. Upper-middle-income countries tend to have a more favorable perception of corruption than their lower-middle-income counterparts. This suggests that, as countries progress economically, there may be corresponding improvements in their perceptions of corruption. However, policymakers should consider the pressing need for robust anti-corruption strategies, particularly in economically challenged regions. Additionally, the variability within the high-income bracket reminds us that achieving economic prosperity does not conclusively eradicate corruption challenges. provides a graphical representation of the average Corruption Perception Index Based on Income per capita.

5.2. Descriptive statistics of public governance

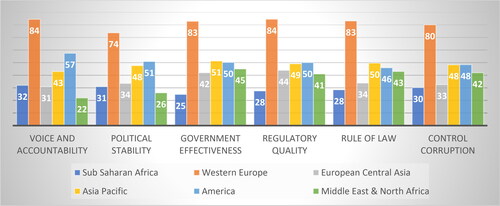

presents a comprehensive analysis of the quality of governance and institutional integrity across different regions of the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, Western Europe, European Central Asia, Asia Pacific, America, and the Middle East and North Africa. This information indicates that Western Europe is perceived as a leader in governance metrics, constantly outperforming other regions in critical indicators, such as Voice and Accountability, Political Stability, and Control of Corruption.

The scores for Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa are comparatively low, which suggests that these regions face challenges related to governance, limited political freedom, and high levels of corruption. On the other hand, Western Europe has higher scores, indicating greater political freedom and citizen participation in governance, as well as streamlined public services and committed civil services. The variance in scores in the Voice and Accountability metric highlights the distinct differences in political freedom and citizen participation in governance between Western Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, Western Europe is relatively peaceful and stable compared with the politically tumultuous regions of European Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Overall, the high scores in the Government Effectiveness metric for Western Europe imply that this region has efficient public services and a strong civil service, while the scores for sub-Saharan Africa suggest potential bureaucratic inefficiencies.

The Regulatory Quality metric shows that Western Europe has an advantageous business environment, with consistent regulations and supportive policies. By contrast, regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa may face challenges due to policy inconsistencies. The data on the rule of law indicates a strong legal framework for Western Europe. Simultaneously, European Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa may experience difficulties related to judicial autonomy and legal enforcement. Finally, the Control of Corruption measure highlights the vigilance of Western Europe against corrupt practices while also exposing vulnerabilities in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa. These insights can guide policymakers and investors in understanding the governance landscape of different regions and identifying potential areas for improvement.

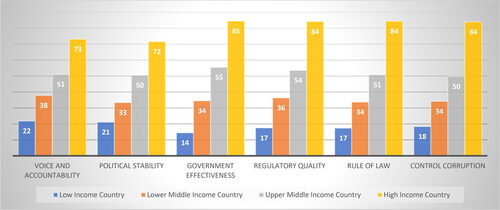

is an important resource for understanding the relationship between a country's income classification and governance measures. The figure evaluates six key governance criteria: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption. This offers an insightful perspective on how economic prosperity and good governance may intersect.

The Voice and Accountability scores suggest that political participation and freedom of expression are limited in low- and lower-middle-income countries. In contrast, upper-middle and high-income nations exhibit more robust civil liberties. Countries with higher incomes are less prone to political disturbances, and high-income nations demonstrate the most stability in this regard. Regarding Government Effectiveness, high-income countries outshine their counterparts with a strong emphasis on efficient public services and effective policy implementation. In contrast, low-income nations face challenges in terms of public administration. Regulatory Quality is directly linked to a country's economic status, with higher-income nations fostering an environment that is more conducive to private sector growth. The Rule of Law is markedly stronger in high-income countries and reflects a trustworthy and accountable legal system. Conversely, lower scores in low- and lower-middle-income countries suggest potential judicial inefficiency. Lastly, the Control of Corruption scores emphasize that high-income countries have superior mechanisms to deter corruption, while nations with lower incomes might benefit from more stringent anti-corruption measures. Overall, these governance indicators link economic prosperity to effective governance.

5.3. Correlation analysis

This study examines the relationship between governance metrics and the public's perception of corruption. presents a clear and striking correlation between the governance variables. Specifically, it highlights an almost perfect link between the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) and the Control Corruption metric with a coefficient of 0.971. This indicates that as countries take more effective measures to control corruption, the public's perception of corruption is significantly improved. Additionally, the study uncovers a strong association between the CPI and the 'Rule of Law' metric, with a coefficient of 0.939. This emphasizes the essential role that a nation's legal system plays in shaping the public's perception of corruption.

Table 4. Correlations Output.

Upon careful analysis of the metrics, we have come to the conclusion that the 'Voice and Accountability' metric holds great significance in determining a country's ability to provide its citizens with the right to participate in the election process and exercise their freedom of speech. This metric exhibits a strong correlation with the Rule of Law (0.812), indicating that nations with transparent accountability mechanisms tend to follow it more effectively. It is worth noting that 'Political Stability' is closely associated with both the 'Rule of Law' and the CPI metric, implying that countries with stable political climates are perceived as less corrupt and more committed to upholding the rule of law. Overall, these metrics provide valuable insights into a country's governance structure and play a crucial role in shaping public opinion and perceptions.

Upon conducting a comprehensive analysis of 'Government Effectiveness,' it is apparent that it exhibits a robust and highly significant correlation with 'Regulatory Quality.' The high coefficient of 0.927 demonstrates that countries with proficient governance not only excel in their administrative capabilities, but also tend to enforce policies and regulations that are easily accessible, user-friendly, and beneficial to their citizens. The correlation between 'Government Effectiveness' and 'Regulatory Quality' underscores the importance of effective governance in creating a regulatory environment that supports economic growth and development. Furthermore, 'Regulatory Quality' is intricately connected to the 'Rule of Law,' highlighting the pivotal role that legal frameworks play in public administration. These findings provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics underlying effective governance and regulatory practices and can guide policymakers and leaders in their efforts to create robust and sustainable governance systems.

The Rule of Law is a fundamental principle of governance that emphasizes the need for a society to be governed based on established laws rather than the whims of individuals or those in power. Research has shown that this concept is crucial in shaping other governance measures, highlighting the importance of establishing a strong legal framework that can promote good governance and curtail corruption. The 'Control Corruption' metric is closely tied to the 'Rule of Law' and 'Government Effectiveness' variables, indicating the need for robust legal and governance systems to counteract corruption effectively. In summary, the interdependence between different aspects of good governance can be complex, but the Rule of Law is a central pillar in this intricate web, ensuring that a society is governed fairly, transparently, and accountable.

The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is a widely recognized measure of corruption in different countries. Recent studies have found that the CPI is strongly related to various public governance components such as Voice and Accountability, Political Stability, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption (Monteduro et al., Citation2016; Naher et al., Citation2020). This suggests that the quality of governance and the level of corruption are closely intertwined. It is essential to adopt a comprehensive and integrated approach to improve governance and fight corruption. Such an approach would recognize the interdependent nature of these two domains and address the complex and multifaceted challenges that arise when dealing with governance and corruption.

5.4. Direct effect analysis

displays the findings of a statistical analysis utilizing the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model. The model examines the relationship between the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) and a set of public governance indicators. The CPI acts as the dependent variable, while public governance indicators, which are considered independent variables, are used to predict CPI values. A panel data regression method was employed to analyze the data.

Table 5. Regression analysis output - direct effect.

The principles of Voice and Accountability are at the core of democratic governance. This principle represents the extent to which citizens are allowed to participate in the selection of their government and express themselves freely through associations and media. A coefficient of 0.1041680 reveals an interesting story. The stronger the foundation of Voice and Accountability, the more positive the public perception, and the lower the likelihood of perceived corruption. The statistical data, with a p-value of 0.0000 and a significant z-value of 7.93, demonstrate that promoting transparent and participatory governance has real benefits in shaping public sentiment towards corruption. The positive coefficient highlights the critical role of citizen participation and freedom in reducing perceived corruption. Countries that ensure greater participation, freedom of expression, and robust media oversight tend to perceive themselves as less corrupt.

Assessment of Political Stability often involves evaluating the likelihood of political unrest or violence. Its connection with the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is complex. Although the figure for 0.0201221 shows that political stability has a minor impact on perceptions of corruption, the p-value of 0.0240 suggests that it remains a crucial factor. Countries with stable regimes that do not experience upheavals provide a sense of continuity that indirectly discourages the perception of corruption. Political Stability measures the probability of political instability, violence, or terrorism. A stable political environment usually leads to better governance and reduced corruption. However, the small coefficient and lack of significance suggest that other factors may outweigh their direct impact on corruption perception.

The term 'Government Effectiveness' refers to how well a government operates, which includes the quality of public services, the government's independence from political pressures, and the level of citizens' trust in the government's policies. The coefficient of 0.0341588 shows that effective governance can improve the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). Additionally, the significant p-value of 0.0070 supports the argument that citizens are likely to perceive less corruption when the government operates optimally. Government Effectiveness measures the quality of public services, the autonomy of civil services from political pressures, policy formulation and execution, and the credibility of government policies. The positive coefficient emphasizes the crucial role of an efficient government apparatus in shaping perceptions of corruption. Countries that improve public service delivery, policy formulation, and execution are expected to receive better scores on the corruption-perception scale.

It is often overlooked that policy formulation and the government's ability to create well-crafted policies can have a significant impact on public opinion. A coefficient of 0.0512218, along with a p-value of 0.0000, highlights the importance of creating transparent, fair, and consistent regulations to prevent the perception of corruption. When citizens perceive that regulations are formulated transparently and enforced fairly, their likelihood of perceiving corruption decreases. Regulatory quality refers to a government's capacity to establish and implement policies and regulations that promote growth in the private sector. Regulations that are transparent and consistently enforced reduce the opportunities for corruption. Therefore, countries with better regulatory quality are considered less corrupt.

The Rule of Law is more than just following the legal codes. It encompasses justice, fairness, and equal treatment under law. If a society consistently upholds the law with fairness, it is less likely to be considered corrupt, as indicated by the coefficient of 0.0935040. A significance level of 0.0000 sends a clear message to policymakers that establishing and maintaining a strong Rule of Law is vital for reducing perceptions of corruption. This involves various factors including contract enforcement, property rights, law enforcement, and courts, all of which contribute to people's trust in societal rules. The strong correlation between the Rule of Law and CPI highlights the essential role of judicial integrity, property rights, and law enforcement in shaping perceptions of corruption. When laws are enforced equitably within a robust legal system, trust in society grows and perceptions of corruption decrease.

The corruption control factor aims to prevent the misuse of public power for personal gain. The coefficient of a given number serves as a strong reminder of the significant impact that anti-corruption efforts can have on the CPI (Corruption Perceptions Index). Its z-value of 25.55 and p-value of 0.0000 demonstrate that direct measures to combat corruption are the most effective in changing societal perceptions of corruption. Control of Corruption measures the extent to which public power is utilized for private gain and encompasses both minor and major forms of corruption. This close relationship underscores the direct and profound link between actual control of corrupt practices and the perception of corruption. Countries that successfully control corrupt practices, ranging from small bribes to large embezzlements, are considered less corrupt.

summarizes the conclusions of the hypotheses. The results show that all aspects of public governance, including voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law, and control of corruption, are positively and significantly related to the corruption perception index.

Table 6. Hypothesis conclusion – direct effect.

5.5. Moderating effect analysis

This study investigates the influence of public governance on the corruption perception index (CPI) and explores the potential moderating role of per-capita income. The hypothesis was that income per capita may moderate the relationship between public governance and the CPI. To test this hypothesis, the regression analysis incorporated the moderating variable, income per capita, and its interaction with various public governance factors, including voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and corruption control. The results of the moderated regression analysis are presented in .

Table 7. Moderated regression analysis output - moderating effect.

After closely examining them, we discovered an interesting correlation between Voice and Accountability and Income Per Capita (IPC). The coefficient of 0.0246268 suggests that, as countries become more economically prosperous, the positive impact of Voice and Accountability on perceptions of corruption also increases. This may indicate that individuals in countries with higher IPC have better access to education, knowledge, and communication channels, which amplifies the influence of Voice and Accountability in shaping perceptions of corruption. Additionally, the p-value of 0.036 confirms this correlation to be statistically significant, indicating that it is not a chance occurrence but a genuine relationship.

The relationship between political stability and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is an interesting topic involving complex dynamics. Studies have shown that the negative coefficient of -0.0268088 suggests that, as a country's wealth increases, it may counterbalance the positive influence of political stability on the perception of corruption. This could be because political stability is already considered a given in prosperous nations, making any direct impact on perceptions of corruption less noticeable. This study reinforces the findings with a p-value of 0.004, highlighting the significant correlation between political stability and economic prosperity.