Abstract

This study examined the impact of safety awareness on the branding effectiveness of cultural events in the context of globalization. Focusing on BTS’ ‘Yet to Come’ concert, a significant event supporting South Korea’s bid to host the Busan World Expo 2030, we analyzed responses from 552 attendees using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 21.0. Our findings revealed that while safety awareness education elevates expectations for safety management services, general safety awareness significantly improves both safety and emergency services. Furthermore, life safety awareness enhances emergency services. Importantly, effective safety services bolster national pride and increase attendees’ willingness to participate in similar future events. This underscores the crucial role of government involvement in ensuring safety and trust in the safety management of events aimed at international audiences. These insights provide a foundation for improving event safety management, contributing to the success and reputation of such performances on a global scale.

SUBJECTS:

Introduction

At a time when cultural festivals attract participants from all over the world, the need to keep people safe at major events has never been more important. These gatherings serve not only as a platform for cultural exchange and enjoyment, but also as a litmus test of a nation’s ability to manage public security in the eyes of the world.

According to Article 28 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (OHCHR, Citation1948), individuals have the right to participate in cultural events in a safe and secure environment. This fundamental premise underscores the importance of balancing the rights of participants with the need for robust security measures. The literature reveals a growing concern about the mismanagement of security at international events, which poses risks to individuals and property and can negatively impact a nation’s international standing (Louw & Esterhuyzen, Citation2022).

Despite the recognised need for effective security management, there remains a significant gap in understanding how to implement such systems in the context of large, culturally diverse gatherings. The complexities introduced by large crowds, coupled with the unique challenges of international festivals, require a nuanced approach to security management - one that protects attendees while enhancing their experience (Höglund, Citation2013).

This study argues that the establishment of sophisticated safety management systems is essential not only to mitigate risk, but also to sustain the growth of the cultural industry and to enhance national pride and international reputation (Baby, Citation2022).

To this end, the research aims to fill the gap in the existing literature by exploring how safety management affects attendees’ experiences and future intentions to attend international festival events. Specifically, it will examine the relationship between safety management practices and attendee satisfaction.

Identify the impact of safety mismanagement on a nation’s international image and reputation. Propose effective strategies for increasing attendee safety awareness to promote a safer event environment.

The structure of the paper is as follows: the next section reviews the relevant literature on safety management at major events, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in current research. The methodology section then outlines the approach taken to investigate the impact of safety management on event attendees. The results section presents findings on the impact of safety practices on attendee experience and national reputation. Finally, the discussion synthesises these findings into recommendations for improving safety management at international cultural festivals.

Theoretical background

Cognitive safety awareness

One of the most important factors in predicting crowd behavior is their awareness of safety levels. Previous studies have indicated that a higher level of shared social identity leads to higher compliance with safety management (Cruwys et al., Citation2020; Lee, Citation2022). Particularly, if participants consider safety measures important or are strongly aware of the organizers’ safety efforts, they display a higher compliance with the relevant guidelines (Hult Khazaie & Khan, Citation2020). An awareness of shared safety levels may also function as a factor in reducing risk-taking by manipulating the perceived importance of safe behavior within social norms (Hopkins & Reicher, Citation2021). Therefore, those responsible for safety management must know what kinds of behaviors will encourage the crowd to follow the communicated safety guidelines (Templeton, Citation2021).

Realistic safety awareness

Safety management should include asking a crowd to lower risks for everyone. Realistic safety awareness can be regarded as general, and life safety awareness as that which can be practiced or exerted in reality. Clear information provided by the organizers can be an important factor in predicting participants’ trust level in safety management efforts and their compliance with the required measures (Templeton et al., Citation2020).

According to Carter et al. (Citation2014), if event organizers provide clear safety guidelines, people will have a stronger sense of shared social identity, which leads to trust-building between them and has a positive impact on safety compliance.

As shown by Hopkins and Reicher (Citation2021) and Carter et al. (Citation2014), safety awareness will affect the acceptance of safety services and guidelines. Therefore, in this study, research hypothesis 1 was established as follows:

H1: Safety awareness will affect safety services.

On-site safety management for festivals

Safety service

They can be categorized based on organizers, targets, and purposes, size, duration, type, and the age and class of participants they cater to Fileborn et al. (Citation2020). Festivals provide people with an avenue to gain new experiences by escaping everyday life—a place where they can create spaces with diverse identities. In addition, people consider festivals as a transcendental or reinforced space, where normative practices and power structures can be overturned (Dilkes-Frayne, Citation2016).

However, festival sites with a gathering of uncorrelated people have a high probability of facilitating incidents like crime, security lapses, and conflicts (Houlton, Citation2018). For instance, Hughes and Moxham-Hall (Citation2017) indicated that 65.3% of participants used illegal drugs at music festivals, and Sampsel et al. (Citation2016) found that such events increase the risk of exposure to violence or sexual assault.

Therefore, festivals should also be considered spaces that are prone to incidents with various risk factors. It is necessary to analyze how central and local governments manage safety services at festivals within the ambit of particular social norms.

Emergency services

A successful festival must also focus on the provision of emergency services. Safety risks increase significantly with large-scale crowds, particularly those comprising young people, and include disorders or riots, a surge in the crowd and harm or even death from pressure, assault, and spread of disease (Raineri, Citation2019).

Audience members getting injured or dying are not new occurrences. In 1969, when nonviolent demonstrations were in full swing in the United States, three visitors died, and 6,000 supporters were treated for injuries at the Woodstock Music and Art Fair (DeBarros, Citation2000). In the same year, 850 people were injured and three people died during the infamous Altamont Speedway Free Festival in Northern California.

It is not uncommon for several types of serious accidents to occur within a short period at concerts. For example, in 1999, at an all-day concert in Maryland, 61 fans were injured to the extent that they required hospitalization (Golec de Zavala & Lantos, Citation2020). Therefore, it is certain that emergency services are required to prevent accidents at festivals.

Performance effectiveness

Human beings feel valued when they are part of a group. In this sense, collective self-esteem is commonly used as ‘a judgmental attitude toward self-value generating from the fact that an individual belongs to a specific group’ (Golec de Zavala & Lantos, Citation2020).

When the group is an entire nation its members may experience a sense of national pride. A nation’s identity, performance, failure, or shameful behavior affects the public’s collective self-esteem (Dimitriadou et al., Citation2019).

The latter can be used as the main indicator of public opinion in a country. If the country has a negative international reputation, then its citizens’ self-esteem may be negatively impacted due to the public’s unfavorable perception of the country’s brand value (Yousaf & Li, Citation2015).

People crave a sense of belonging and security within a group, and can expect the state to help facilitate this. Therefore, a public collective self-esteem can be created if the state fulfills its obligations of providing people with public safety and protection (Druckman, Citation1994).

As such, Nathanson (Citation1994), Dresler-Hawke and Liu (Citation2006), and Dimitriadou et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that the safety services provided by performers for people around the world have a positive effect on the self-esteem of the people in a host country. Additionally, Druckman (Citation1994) showed that safety services provided by public institutions will have a positive impact on the effectiveness of performances in enhancing the public’s national pride and intention to participate in similar events. Therefore, in this study, research hypothesis 2 was formulated as follows:

H2: Safety services positively impact the effectiveness of cultural performances in enhancing national pride and the intention to participate in similar events.

Solidarities generated by social identity are imperative for the coalition and unanimity of a national community. Previous studies have indicated that individuals consider collective self-esteem in the process of creating social identity (Jetten et al., Citation1997).

National reputation can be defined as the holistic evaluation of a country by diverse people from other countries. This longstanding evaluation is also based on diverse composition factors such as history, culture, economy, society, and communication between particular countries (Szondi, Citation2008).

In the era of globalization, national reputation has a significant impact on a country’s brand value in fields like economy, culture, and politics. Countries with a more positive national reputation have competitive advantages in the globalized capitalist economy (i.e., neo-liberalism) (Kaneva, Citation2011).

If people perceive their countries positively, they are highly likely to comply with systems within the community that foster respect for other society members. Furthermore, the more positively people perceive their own country, the more they express an intention to support it. National pride is also linked to a higher willingness to participate in festivals and events that aim to attract international crowds, which ultimately leads to increased performance effectiveness (Yousaf & Li, Citation2015). Therefore, we formulated hypothesis 3 as follows:

H3: National pride positively impacts the intention to participate in similar cultural performances in the future.

Research model and hypotheses

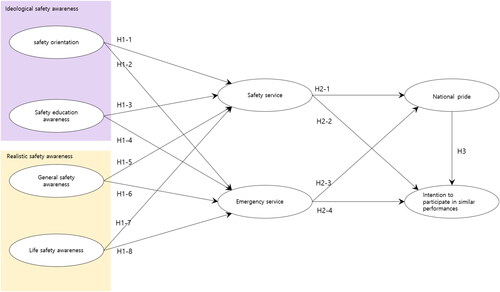

Based on previous studies on cognitive safety awareness, realistic safety awareness, and safety services, we developed a research model shown in , and established the following research hypotheses in line with the research model:

H1: Safety awareness will affect safety services.

H1-1: Safety orientation will have a positive impact on safety services.

H1-2: Safety orientation will have a positive impact on emergency services.

H1-3: Safety education and awareness will have a negative impact on safety services.

H1-4: Safety education and awareness will have a negative impact on emergency services.

H1-5: General safety awareness will have a positive impact on safety services.

H1-6: General safety awareness will have a positive impact on emergency services.

H1-7: Life safety awareness will have a positive impact on safety services.

H1-8: Life safety awareness will have a positive impact on emergency services.

H2: Safety services will impact performance effectiveness.

H2-1: Safety services will have a positive impact on national pride.

H2-2: Safety services will have a positive impact on the intention to participate in similar performances.

H2-3: Emergency services will have a positive impact on national pride.

H2-4: Emergency services will have a positive impact on the intention to participate in similar performances.

H3: National pride will have a positive impact on the intention to participate in similar performances.

Research survey and analysis methods

The data for this study were collected through an online survey of participants to BTS’ ‘Yet to Come’ concert held in Busan, South Korea on 15 October 2022, to support the bid to host the Busan World Expo 2030. The survey was conducted for 13 days, from 19 October to 31 October 2022. First, we developed structured questionnaires, and then converted them into a format that enabled study targets to respond to questions online, including on a mobile phone. The online survey was distributed to respondents through social networks. We also developed online questionnaires to prevent the occurrence of missing values or outliers. Ultimately, we utilized 552 questionnaires in the analysis.

The study employed a reliability analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis to verify the reliability of the scale and a multigroup structural equation model (SEM) analysis to verify the research model. SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 21.0 software were used to conduct these analyses.

Measurement tools

As shown in , we developed measurement tools to assess cognitive safety awareness, realistic safety awareness, and performance effectiveness.

Table 1. Measuring tools.

Safety awareness

Crowds will naturally comply with orders and regulations for their safety if festival safety management systems are established based on an understanding of participant characteristics, crowd behavior, and festival purposes (Hopkins & Reicher, Citation2021). Furthermore, crowd compliance can also be achieved through public adhesion by spreading accurate safety information. This compliance can also affect the public’s perception of the governments that manage the festivals. Previous studies (Branscombe & Wann, Citation1994) highlighted that a more positive public perception of the government encouraged people to demonstrate a positive attitude toward solidarity in the community.

In this sense, safety awareness can be divided into ideological and realistic safety awareness, which are shared by a community. Each variable was measured as follows.

First, cognitive safety awareness is created through information provision, an important factor in determining a festival’s success, as highlighted by Dalgiç and Birdir (Citation2020) and Crampton et al. (Citation2020). The loyalty of festival visitors and the festival success factors are correlated with safety orientation. Based on previous studies, we measured safety orientation with variables such as safety information, and interest in and willingness to pay for safety. All variables were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Second, safety education is essential for cognitive safety awareness when hosting sustainable festivals. According to Omitola (Citation2017) and Sun (Citation2016), the effectiveness in reducing and preventing accidents at festivals is significantly influenced by the safety training provided to the crowd, along with the specific perceptions of festival managers, organizers, and visitors regarding safety measures and emergency protocols. These perceptions include awareness of potential hazards, understanding of safety procedures, and confidence in the festival’s ability to manage emergencies effectively. In this regard, we used the necessity of safety education and education reinforcement as measurement variables.

Third, in terms of realistic safety awareness, we measured relevant variables based on the classification of public safety awareness as general and life safety awareness. According to Sohn et al. (Citation2016), perceived risk awareness affects the festival’s evaluation and participants’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Saadat et al. (Citation2010) found that attendees with higher perceived risk awareness took actions to mitigate risks. Accordingly, we divided realistic safety awareness into general and life safety awareness and measured them with variables such as the safety system, community safety level, community trust, interest in life safety, and life safety knowledge. All variables were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Safety management services

Based on previous studies on contributors toward festival success and image management, this study analyzed the provision of safety management services and its effect on the festival image (Ivers et al., Citation2022). Tangit et al. (Citation2016) found that safety service provision affected visitors’ satisfaction, festival image, and socioeconomic effectiveness. In this regard, we classified safety management services into safety and emergency services, and measured them with variables such as human and material resources. All variables were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Performance effectiveness

The most widely utilized variable to measure performance effectiveness is the intention to participate in similar events in the future (Lee et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Wong et al., Citation2015). We thus used this variable to measure performance effectiveness on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

We also attempted to examine how national pride affected festivals that attract international audiences. Baumeister et al. (Citation1996) argued that low self-esteem related to belonging to one’s country has a significant impact on selfishness, violence, and aggression, which negatively impacts national integration.

National pride was thus measured in this study using national reputation, national self-esteem, importance of assessing collective self-esteem, membership/collective self-esteem, and public collective self-esteem as variables.

Characteristics of the research participants

The age groups and response rates of visitors to the festival were as follows: 8.1% were in their 10s, 18.1% in their 20s, 33.8% in their 30s, 31% in their 40s, 7.9% in their 50s, and 0.7% in their 60s. Respondents in their 30s and 40s had the highest response rates. In terms of residence, 52.9% of the respondents resided in Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi Province; 6% in Gwangju, Jeolla Province, Gangwon Province, and Jeju Island; 30.3% in Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, and Gyeongsang Province; 9.4% in Daejeon, Sejong, and Chungcheong Province; and 1.1% in other counties. The crowd was thus mostly comprised of people from Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi Province, followed by those from Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, and Gyeongsang Province.

Furthermore, 15.9% of respondents were high school graduates or had a lower level of education, 22.2% were college graduates, 49.1% were four-year university graduates, and 12.5% had passed graduate school or a higher form of education; 32.7% of them were full-time employees and 4.7% worked in part-time roles; 1.8% operated large, small, or medium-sized businesses; 7% were self-employed; 12.8% were students; 11.6% were housewives; 25.5% worked in professional fields; and 3.6% were unemployed.

Results

Reliability and validity analyses of the measurement tools

This study rigorously assessed the reliability and validity of the measurement scales on two separate occasions. Initially, exploratory factor analysis and reliability tests were performed to ensure that the measurement variables were aptly grouped under each corresponding latent variable. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis and reliability tests were employed to determine the soundness of the relationships between latent and measurement variables and to confirm their robustness.

In the exploratory factor analysis, factors were extracted with eigenvalues exceeding one, utilizing varimax rotation and principal component analysis for optimal clarity. This process distinctly categorized the items of cognitive safety awareness, realistic safety awareness, safety management services, and performance effectiveness into their respective factors. Cognitive safety awareness was bifurcated into ‘safety orientation’ and ‘safety awareness education’, while realistic safety awareness was categorized into ‘general safety awareness’ and ‘life safety awareness’. Safety management services were divided into ‘safety service’ and ‘emergency service’, and performance effectiveness was divided into ‘intent to participate in similar performances’ and ‘national pride’. Each factor surpassed the thresholds for validity (commonality ≥ 0.5) and reliability (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.7), as listed in .

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis.

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis and subsequent reliability tests, presented in , indicated that certain items diminished the validity of scale—such as the connection between safety orientation and willingness to pay, general safety awareness and perceived safety levels, and national pride and self-evaluation—leading to their removal. Post-elimination, the model’s goodness of fit was statistically validated, with indices (CMIN = 437.413; RMR = 0.028, GFI = 0.925, AGFI = 0.896, RMSEA = 0.042, NFI = 0.936, IFI = 0.972, CFI = 0.972) suggesting a robust structure. Factor loadings exceeded 0.7, construct reliability (CR) surpassed 0.7, and average variance extracted (AVE) was above 0.5. Additionally, the comparison between the correlations of the latent variables and the square roots of AVE demonstrated the latter to be greater, confirming the discriminant validity of the scale. Cronbach’s alpha maintained a reliability score above 0.7.

Table 3. Results of validity factors and reliability of the measures.

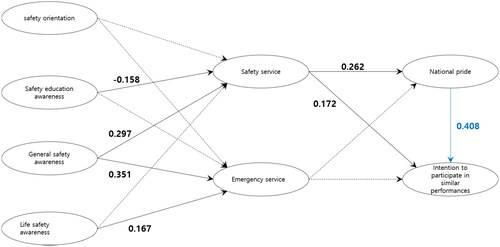

Our causal analysis investigated how components of safety awareness—ideological and realistic (encompassing general and life safety awareness)—influenced performance effectiveness. The fit indices (CMIN = 376.132, CMIN/DF = 2.011, RMR = 0.043, RMSEA = 0.049, GFI = 0.925, AGFI = 0.908, NFI = 0.937, IFI = 0.967, and CFI = 0.967) corroborated a satisfactory model fit, depicted in .

The study uncovered that safety orientation did not significantly impact safety and emergency services. However, contrary to expectations, it was found that a higher emphasis on safety awareness education was associated with lower satisfaction regarding the provision of current safety services (β = –0.158, p < .01). Conversely, general safety awareness positively influenced both safety services (β = 0.297, p < .001) and emergency services (β = 0.351, p < .001), and life safety awareness similarly favored emergency services (β = 0.167, p < .01). Interestingly, positive perceptions of safety services significantly uplifted national pride (β = 0.262, p < .001) and the inclination to attend similar events (β = 0.172, p < .05), which in turn was further enhanced by national pride (β = 0.408, p < .001). These findings suggest that increased demands for safety education might elevate expectations for safety management services, a hypothesis supported by the data. The study’s results indicate that as demand for safety education increases, so do expectations for safety management services. This conclusion aligns with the initial hypothesis, specifically Hypothesis which proposed a direct relationship between the level of safety awareness education and the anticipated quality of safety management services. The data, encompassing both the statistical analysis (β values and p-values) and the observed trends in perceptions of safety services and their impact on national pride and event attendance, provide robust support for this conclusion. This comprehensive data set reinforces the notion that heightened safety education leads to more stringent expectations for safety management in event contexts.

However, a similar notable effect was not demonstrated for emergency services, possibly due to a lack of direct experience among respondents. The supported hypotheses H2-1 and H2-2 proposed that safety services elevate national pride and willingness to participate in similar events, and general safety awareness constructively affects safety and emergency services. This points to a complex interplay of factors contributing to the success of events aiming to attract international audiences.

summarizes the direct and indirect effects of the variables. Notably, safety services were found to have both a direct and indirect positive impact on the intention to attend similar events, mediated by an uplift in national pride. This underscores the multifaceted role of safety services in enhancing public perception, national pride, and engagement in events, confirming the critical nature of safety measures in ensuring festival effectiveness.

Table 4. Standardized effects.

Discussion

This study embarked on exploring the intricate dynamics of safety management at international events and festivals. Our investigation aligns with the observations by Doe et al. (Citation2022) and Gold (Citation2016) about the positive impacts of such events on national branding and socioeconomic development, while also delving into the critical role of safety management within this context.

Echoing Doe et al. (Citation2022), our findings confirm the significant benefits that international events confer on national branding and socioeconomic development. Gold (Citation2016) further elucidates that the competition among countries to host these events is fierce, underscoring the perceived value they bring.

Fileborn et al. (Citation2020) emphasize the role of festivals in creating spaces for diverse cultural and personal enrichment. Our study extends this conversation by examining how safety management influences these spaces, ensuring they remain inclusive and safe for all attendees.

Houlton (Citation2018) underscores the vulnerability of festivals to security issues and the necessity of pre-security management plans. Our analysis adds depth to this narrative by evaluating the impact of cognitive safety awareness and safety education on the demand for and effectiveness of safety services.

Our investigation reveals nuanced findings regarding safety awareness. Contrary to the straightforward impacts suggested by Baby (Citation2022), Hamm and Su (Citation2021), and Harris et al. (Citation2021), we found that cognitive safety orientation does not directly influence safety outcomes. This divergence points to the complexity of managing attendee expectations around safety, challenging the direct correlations previously suggested by Taylor and Toohey (Citation2005, Citation2006).

Kurtz et al. (Citation2018) posited minimal impact of safety education on service expectations, a claim our study contests. We demonstrate that increased safety education correlates with heightened service expectations, underscoring the critical role of pre-event safety education as suggested by Pracht et al. (Citation2011) and Arora et al. (Citation2021) in shaping attendees’ safety perceptions and demands.

Our findings contrast with those of Lim and Prakash (Citation2021), who identified a significant positive impact of emergency services on national pride and attendee loyalty. This discrepancy may be attributed to cultural or contextual differences, suggesting a need for context-specific safety management strategies.

The implications of our study extend the current discourse on safety management at international events, offering new insights into the complex interplay between safety awareness, education, and service expectations. By integrating and contrasting the contributions of various authors within our discussion, we highlight the nuanced dynamics of safety management and its impact on national branding, attendee experiences, and expectations. Our study underscores the necessity for nuanced safety education strategies and calls for further research into context-specific safety management practices, setting a foundation for future inquiries as suggested by Jiang and Chen (Citation2019).

Our study contributes to the theoretical understanding of safety management in the context of international festivals and events. It challenges the existing notion that safety awareness among attendees does not significantly influence the effectiveness of safety and emergency services. Notably, our findings indicate that while cognitive safety orientation may not directly affect safety outcomes, safety awareness education does influence expectations and demands for these services. This nuanced view extends the theoretical discourse on safety management by suggesting that attendees’ safety perceptions are multifaceted and that different dimensions of safety awareness have varying impacts on their expectations and service demands.

From a practical standpoint, the findings underscore the importance of pre-event safety education to heighten awareness and adjust service expectations. The positive relationship between safety services and national pride, as well as the intention to participate in similar events, highlights the role of safety management in fostering a positive image of the host nation and encouraging repeat attendance. Festival organizers and government bodies must, therefore, prioritize safety in their strategic planning and operations, ensuring that safety services are not only effective but also well communicated to the public.

Policy implications and future research directions

The study emphasizes the crucial role of safety management in events with international significance, such as the BTS concert at the Busan World Expo 2030. It reveals that effective safety management not only prevents negative impacts on national self-esteem and identity but also enhances public trust and satisfaction.

This highlights the need for detailed safety planning, education, and transparent policies in attracting and successfully conducting large-scale international events.

Future research should expand on this by exploring the nuanced relationship between safety management, national branding, and attendee perceptions across a diverse range of international events. Longitudinal studies could offer valuable insights into the evolution of safety practices and their long-term effects on national image and attendee behavior.

Additionally, comparative cultural studies on safety perceptions and priorities may enhance the global relevance of safety strategies. Investigating the implementation and effectiveness of safety and emergency protocols is also essential for developing globally applicable best practices in safety management, ensuring that large-scale events are both safe and positively contribute to national branding at an international level.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The analysis was based on a single event supporting South Korea’s bid to host an international event, limiting its generalizability to other event types or cultural contexts. Additionally, the assessment of safety and emergency services was based on participants’ perceptions, which may not accurately reflect the objective quality or effectiveness of the services provided.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. I would also like to thank Do Yeon Lee (English), Yiping Yao (Chinese), Hannah Kontos (German), Nita Yuliastuti & Jeong Ming Ryu (Indonesian), Hye Sun Cho (Japanese), Hyeon Ju Bang for the editing of the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Center for Disaster Safety Innovation, National Crisisonomy Institute, Chungbuk National University. However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study, and are thus not publicly available. Data are nevertheless available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the said Center.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eugene Song

Eugene Song ([email protected]) received her B.A. M.A. and Ph.D. from Chungbuk National University. She is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Consumer Science at Chungbuk National University. Her research interests include risk communication, consumer information, consumer safety, and big data.

Seol A. Kwon

Seol A. Kwon ([email protected]) received her Ph.D. from Chungbuk National University, Korea in 2017. She is a Chief of Center for Disaster Safety Innovation, National Crisisonomy Institute (NCI), Chungbuk National University. Her research interests include life environment crisis, crisis manage ment, organization theories, and risk communication.

Jae-Eun Lee

Jae-Eun Lee ([email protected]) received his B.A., M.A., Ph.D. from Yonsei University, Korea in 2000. He is a Director of National Crisisonomy Institute (NCI) and a Professor of the Department of Public Administration at Chungbuk National University, in which he has taught since 2000. His interesting subject and area of research and education is crisisonomy, disastronomy, organizational studies, and policy implementation.

Jee Eun Kim

Jee Eun Kim ([email protected]) received her M.A from Chungbuk National University, Korea in 2018. She is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Public Administration at Chungbuk National University, in Korea. Her research interests are crisis & emergency management, fire administration, living safety and decision making theory.

References

- Arora, S., Tsang, F., Kekecs, Z., Shah, N., Archer, S., Smith, J., & Darzi, A. (2021). Patient safety education 20 years after the Institute of Medicine Report: Results from a cross-sectional national survey. Journal of Patient Safety, 17(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000676

- Baby, J. (2022). Influence of festival attractiveness, novelty, and experience on attendees’ satisfaction: Moderating role of risk awareness in a cultural festival. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, 15(2), 123–132.

- Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.103.1.5

- Branscombe, N. R., & Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(6), 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240603

- Carter, H., Drury, J., Amlôt, R., James Rubin, G., & Williams, R. (2014). Effective responder communication improves efficiency and psychological outcomes in a mass decontamination field experiment: Implications for public behaviour in the event of a chemical incident. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e89846. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089846

- Crampton, J. W., Hoover, K. C., Smith, H., Graham, S., & Berbesque, J. C. (2020). Smart festivals? Security and freedom for well-being in urban smart spaces. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(2), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2019.1662765

- Cruwys, T., Stevens, M., & Greenaway, K. H. (2020). A social identity perspective on COVID-19: Health risk is affected by shared group membership. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12391

- Dalgiç, A., & Birdir, K. (2020). The effect of key success factors on loyalty of festival visitors: The mediating effect of festival experience and festival image. Tourism & Management Studies, 16(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2020.160103

- DeBarros, A. (2000, August 8) Concertgoers push injuries surge to high levels decades after deadly who show, violence worsens. USA Today.

- Dilkes-Frayne, E. (2016). Drugs at the campsite: Socio-spatial relations and drug use at music festivals. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 33, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.10.004

- Dimitriadou, M., Maciejovsky, B., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2019). Collective nostalgia and domestic country bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 25(3), 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000209

- Doe, F., Preko, A., Akroful, H., & Okai-Anderson, E. K. (2022). Festival tourism and socioeconomic development: Case of Kwahu traditional areas of Ghana. International Hospitality Review, 36(1), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-09-2020-0060

- Dresler-Hawke, E., & Liu, J. H. (2006). Collective shame and the positioning of German national identity. Psicología Política, 32, 131–153.

- Druckman, D. (1994). Nationalism, patriotism, and group loyalty: A social psychological perspective. Mershon International Studies Review, 38(1), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/222610

- Fileborn, B., Wadds, P., & Tomsen, S. (2020). Sexual harassment and violence at Australian music festivals: Reporting practices and experiences of festival attendees. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 53(2), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865820903777

- Gold, J. R. (2016). Cities of culture: Staging international festivals and the urban agenda, 1851–2000. Routledge.

- Golec de Zavala, A., & Lantos, D. (2020). Collective narcissism and its social consequences: The bad and the ugly. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420917703

- Hamm, D., & Su, C.-H (. (2021). Managing tourism safety and risk: Using the Delphi expert consensus method in developing the event tourism security self-beliefs scale. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.10.001

- Harris, M., Kreindler, J., El-Osta, A., Esko, T., & Majeed, A. (2021). Safe management of full-capacity live/mass events in COVID-19 will require mathematical, epidemiological and economic modelling. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114(6), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/01410768211007759

- Höglund, F. (2013). The use of resilience strategies in crowd management at a music festival. University of Likoping.

- Hopkins, N., & Reicher, S. (2021). Mass gatherings, health, and well-being: From risk mitigation to health promotion. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 114–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12071

- Houlton, S. (2018). Festival security. Intersec: The Journal of International Security, 28(8), 30–32.

- Hughes, C. E., & Moxham-Hall, V. L. (2017). The going out in Sydney App: Evaluating the utility of a smartphone app for monitoring real-world illicit drug use and police encounters among festival and club goers. Substance Abuse: research and Treatment, 11, 1178221817711419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221817711419

- Hult Khazaie, D., & Khan, S. S. (2020). Shared social identification in mass gatherings lowers health risk perceptions via lowered disgust. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(4), 839–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12362

- Ivers, J.-H., Killeen, N., & Keenan, E. (2022). Drug use, harm-reduction practices and attitudes toward the utilisation of drug safety testing services in an Irish cohort of festival-goers. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 191(4), 1701–1710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02765-2

- Jetten, J., Branscombe, N. R., & Spears, R. (2002). On being peripheral: Effects of identity insecurity on personal and collective self-esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.64

- Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. (1997). Distinctiveness threat and prototypicality: Combined effects on intergroup discrimination and collective self-esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(6), 635–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199711/12)27:6<635::AID-EJSP835>3.0.CO;2-#

- Jiang, Y., & Chen, N. (2019). Event attendance motives, host city evaluation, and behavioral intentions: An empirical study of Rio 2016. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(8), 3270–3286. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2018-0501

- Kaneva, N. (2011). Nation branding: Toward an agenda for critical research. International Journal of Communication, 5, 25.

- Kim, B., & Kim, Y. (2019). Growing as social beings: How social media use for college sports is associated with college students’ group identity and collective self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.016

- Kurtz, D. L. M., Janke, R., Vinek, J., Wells, T., Hutchinson, P., & Froste, A. (2018). Health sciences cultural safety education in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: A literature review. International Journal of Medical Education, 9, 271–285. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5bc7.21e2

- Lee, C.-K., Lee, Y.-K., & Wicks, B. E. (2004). Segmentation of festival motivation by nationality and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 25(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00060-8

- Lee, J., Kyle, G., & Scott, D. (2012). The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. Journal of Travel Research, 51(6), 754–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512437859

- Lee, Y. (2022). How dialogic internal communication fosters employees’ safety behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Relations Review, 48(1), 102156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102156

- Lim, S., & Prakash, A. (2021). Pandemics and citizen perceptions about their country: Did COVID-19 increase national pride in South Korea? Nations and Nationalism, 27(3), 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12749

- Lopez, S. J. (2009). The encyclopedia of positive psychology. Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444306002

- Louw, L. B., & Esterhuyzen, E. (2022). Disaster risk reduction: Integrating sustainable development goals and occupational safety and health in festival and event management. Jamba (Potchefstroom, South Africa), 14(1), 1205. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v14i1.1205

- Mavrić, B. (2014). Psycho-social conception of national identity and collective self-esteem. Epiphany, 7(1), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.21533/epiphany.v7i1.91

- Mykletun, R. J. (2011). Festival safety – Lessons learned from the Stavanger food festival (the Gladmatfestival). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 342–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593363

- Nathanson, D. L. (1994). Shame and pride: Affect, sex, and the birth of the self. Norton.

- OHCHR. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- Omitola, A. (2017). Tourism and sustainable development in Nigeria: Attractions and limitations of carnivals and festivals. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 19(2), 122–132.

- Ozer, S., Obaidi, M., & Pfattheicher, S. (2020). Group membership and radicalization: A cross-national investigation of collective self-esteem underlying extremism. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23(8), 1230–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220922901

- Pracht, D., Terry, B. D., & Fogarty, K. (2011). Risk management for volunteer resource managers: Pre-event planning matrix. Risk Management, 28(3), 9.

- Raineri, A. (2019). The causes and prevention of serious crowd injury and fatalities at outdoor music festivals. Safety Institute of Australia.

- Saadat, S., Naseripour, M., Karbakhsh, M., & Rahimi-Movaghar, V. (2010). Perceived risk and risk-taking behavior during the festival firework. American Journal of Health Behavior, 34(5), 525–531. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.34.5.2

- Sampsel, K., Godbout, J., Leach, T., Taljaard, M., & Calder, L. (2016). Characteristics associated with sexual assaults at mass gatherings. Emergency Medicine Journal: EMJ, 33(2), 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2015-204689

- Sohn, H.-K., Lee, T. J., & Yoon, Y.-S. (2016). Relationship between perceived risk, evaluation, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: A case of local-festival visitors. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1024912

- Sun, L. (2016). Discussion on the construction of security system of conference, festival and special event [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2016), Paris, France. Atlantis Press (pp. 539–543). https://doi.org/10.2991/ieesasm-16.2016.113

- Szondi, G. (2008). Central and Eastern European public diplomacy: A transitional perspective on national reputation management. In Routledge handbook of public diplomacy (pp. 312–333). Routledge.

- Tangit, T. M., Kibat, S. A., & Adanan, A. (2016). Lessons in managing visitors experience: The case of Future Music Festival Asia (FMFA) 2014 in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance, 37, 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30092-2

- Taylor, T., & Toohey, K. (2005). Impacts of terrorism-related safety and security measures at a major sport event. Event Management, 9(4), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599506776771544

- Taylor, T., & Toohey, K. (2006). Security, perceived safety, and event attendee enjoyment at the 2003 Rugby World Cup. Tourism Review International, 10(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427206779367127

- Templeton, A. (2021). Future research avenues to facilitate social connectedness and safe collective behavior at organized crowd events. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220983601

- Templeton, A., Smith, K., Guay, J. D., Barker, N., & Whitehouse, D. (2020). Returning to UK sporting events during COVID-19: Spectator experiences at pilot events. Sports Grounds Safety Authority

- Wong, J., Wu, H.-C., & Cheng, C.-C. (2015). An empirical analysis of synthesizing the effects of festival quality, emotion, festival image and festival satisfaction on festival loyalty: A case study of Macau Food Festival. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(6), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2011

- Yousaf, S., & Li, H. (2015). Social identity, collective self esteem and country reputation: The case of Pakistan. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2014-0548