Abstract

This article examines the historical and contemporary contexts of sanitation services in South Africa. Drawing on colonial and apartheid-era policies, the paper shows how segregation and social class have significantly shaped sanitation delivery in the country. Despite post-1994 policy initiatives to expand services to all South Africans and decentralise governance structures, the paper notes that the legacies of colonial planning and politics complicate meaningful sanitary reforms. It argues that to improve sanitation in informal settlements, it is crucial to contextualise the past legacies and consider the current socio-economic and political progress in urban South Africa. The paper concludes by highlighting the need for comprehensive and integrated approaches to sanitation that consider the issue’s complex historical and contemporary contexts.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Sanitation politics in colonial African cities is an old phenomenon that has existed for centuries and requires an understanding of the inner workings of the urban system that produce and reproduce these challenges. African urban studies have linked these challenges to the planning issues inherited from colonial administrations (Fourchard, Citation2024; Muchadenyika & Williams, Citation2016; Van Noorloos & Kloosterboer, Citation2018). Segregated planning during the colonial era perpetuated these challenges yet the planning pattern has not changed significantly in the cities of global South (Miraftab, Citation2012; Muchadenyika & Williams, Citation2016; Watson, Citation2009; World Bank Group, Citation2018). In Cape Town, the issue of sanitation and informal settlements is closely linked to the history of urban planning and colonial influence. The colonial and apartheid urban planning practices, which relied on elitist exclusionary urbanism, gave rise to the emergence of squatter movements as a response to segregation policies. In the 1940s, community protests and mobilisation against apartheid intensified in many black communities, challenging the apartheid system.

Following the fall of apartheid, post-apartheid South Africa introduced municipal governance structures to decentralise governance and extend services to all South Africans. To address the legacies of the past, Cape Town, an apartheid city, created unicity Cape Town, which aimed to unify fragmented governance structures (Swilling & De Wit, Citation2010). Previously, the city was governed by 61 municipalities, separately managed by 17 administrations. This changed during the first local government elections in 1995-1996, as integrated municipal areas were established as part of post-1994 reforms. The Municipal Structures Act later outlined the new system of metropolitan government, leading to the establishment of unicity Cape Town. The unified structure secured a single metropolitan tax base to solve development disparities and amalgamated previously segregated white and black local authorities to ensure outstanding equity between affluent and poor communities.

Contemporary sanitation problems are an indication of how post-colonial and post-apartheid governments have struggled in the provision of essential services to the populace. In South Africa, the bucket system for sanitation has persisted in informal settlements since the fall of apartheid despite the government’s deliberate attempt to eradicate it. Bucket toilets produce a stinking smell, are unhygienic, difficult to clean, and very hard to control flies (Norvixoxo et al., Citation2022; Robins, Citation2014b). This unhygienic state of sanitation, particularly in the informal settlements, has had tremendous adverse effects on the lives of poor people. In 2018 and 2019, the Southern African neighbouring countries South Africa and Zimbabwe experienced cases of cholera outbreak (Mashe et al., Citation2020). On February 28, 2023, a total of 6 cases of cholera were confirmed in the laboratory. The 6 cases occurred in the province of Gauteng, and the 1-3 cases were described as imported cases from Malawi (Smith et al., Citation2023). However, cases 4-6 were acquired locally with indigenous patients who had no travel history. Though the cause of cholera is still disguised and downplayed as an imported disease, the recent COVID-19 outbreak exposed the levels of inequality in informal settlements. When the South African government announced the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines for preventative measures like washing hands regularly, hygiene, and social distancing, people in the informal settlements had difficulty following these guidelines (Yende & Mkhwanazi, Citation2023). The announcement of guidelines ignited protests among informal settlement dwellers who demanded that the local government provide water for washing hands. Just like how the Victorian public health movement influenced the municipal commissioners to engineer sanitary reforms in colonies (Miraftab, Citation2012; Parnell, Citation1993; Swanson, Citation1977), the global COVID-19 outbreak exposed the unequal distribution and management of the sanitation infrastructure.

Using politics and change as the critical aspects in understanding and directing sanitation provision, the article uses social justice theory to analyse sanitation politics, legacies, and change in Cape Town. The approach enables the analysis of equitable sanitation services and distribution among urban communities and the extent to which historical inequalities have been addressed. Previous studies have looked at sanitation politics in Cape Town (Amisi & Nojiyeza, Citation2008; Miraftab, Citation2012; Overy, Citation2013; Radfield and Robins, 2016; Robins, Citation2014a; Swanson, Citation1995; Taing, Citation2017), but few have questioned the persistence of sanitation delivery challenges and politics in colonial cities. The article analyses the historical context of urban planning and colonial influence in Cape Town. It traces the emergence of slum production and discusses the responses to poor sanitation under apartheid and post-1994. In the first part of the paper, the article presents colonial urban planning and the resultant adverse effects of urbanisation. It demonstrates how the elitist exclusionary urbanism using specific drivers played a vital role in the urban governance of the Cape Colony.

The second part of the paper presents the response of the apartheid government in addressing the sanitation syndrome. The paper shows the emergence of the squatter movements as a response to segregation policies. Community protests and organisations against apartheid gained momentum in many black communities. The third part of the paper presents the response to sanitation challenges in the post-apartheid government. It shows how post-apartheid South Africa tried to decentralise the governance system through municipal governance structures to extend services to all South Africans. The section further shows how Cape Town, as an apartheid city, tried to address divisions that created poverty. The last part of the paper demonstrates the disparities that still exist in sanitation delivery and paints a clear picture of sanitation protests and the achievements of community activists. The article defines sanitation politics as the actions of political actors and other parties involved in planning sanitation services. Legacies refer to cultural, social, and economic aspects inherited from the past, including traditions, institutions, and practices that still influence the planning system. Before 1994, black people and those lower on the social hierarchy had limited access to such services (Miraftab, Citation2012; Swanson, Citation1995), and this became the top priority of the democratic government to address inequality (Marais & Cloete, Citation2016).

2. Urban social justice

The concept of social justice is based on establishing a prosperous and equitable urban society where everyone, regardless of their background, has equal access to opportunities. In his book Social Justice and the City, Havery makes the following observations:

I move from a predisposition to regard social justice as a matter of eternal justice and morality to regard it as something contingent upon the social processes operating in the society as a whole. This is not to say that social justice is to be regarded as merely a pragmatic concept which can be shifted at will to meet the requirements of any situation. The sense of justice is a deeply held belief in the minds of many (including mine). However, Marx posed the question, "Why these beliefs?" Furthermore, this is a disturbing but perfectly valid question. The answer to it cannot be fashioned out of abstraction. As with the question of space, there can be no philosophical answer to a philosophical question – only an answer fashioned out of the study of human practice (Harvey, Citation2010, p. 15–16).

Cities are founded on the exploitation of the many by the few. Thus, urbanism founded on exploitation is a legacy of history. A genuinely humanising urbanism has yet to be brought into being. It thus remains for a revolutionary theory to chart the path from an urbanism based in exploitation to an urbanism appropriate for the human species (Harvey, Citation1976, p.314).

3. Urban planning in colonial era: Cape Colony

The colonial planning system shaped the urban form of many global South cities (Horn, Citation2019; Muchadenyika, Citation2020). Cape Town’s social composition and fractured spatial form reflect its colonial and apartheid planning. The city was designed to benefit a privileged minority for over three centuries while neglecting the needs of the indigenous majority based on their skin colour (Turok et al., Citation2021). Segregated urban planning in the Cape Colony formed urban injustice in the rapidly urbanising city of the 19th century. Peter Hall’s chapter ‘City of the Dreadful Night’ from the book ‘Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880’ offers a thought-provoking analysis of the negative effects of urbanisation and modern city life. Industrialisation and urbanisation during the 19th and 20th centuries led to the emergence of overcrowded, polluted, and poverty-stricken cities, described as the ‘city of the dreadful night’ (Hall, Citation2014, p. 12). This term was used to describe the dark and chaotic nature of these cities, which were overwhelming for their inhabitants. Respectively, the economic boom of Cape Town in the 1870s led to a surge in population and increased demand for essential services (Gwaindepi & Fourie, Citation2020; Miraftab, Citation2012). In 1872, the population grew to 45000, increasing the municipal population to 33,000. The urban administration focused the developments in the town centre at the expense of the outlying areas. This selective budgeting created opposition among ward commissioners who demanded that services be extended to other parts of the municipality. The provision of water was one of the essential services demanded, and it later became a critical issue in anticolonial struggles from 1842 to 1847. These inequalities in the urban services gave Cape Town the reputation of the ‘city of stinks’ in 1876 (Miraftab, Citation2012, p. 11). While the great stinkFootnote1 in London was due to the reluctance of the leadership to act, the filthy conditions in the Cape Colony were due to segregated planning. It was after the English-speaking elite merchants criticised the sanitation of Cape Town in 1875 and advocated for a proper drainage system (Miraftab, Citation2012). This suggested the influence of elite merchants on urban planning and how the future of the colonial town defined and shaped human settlements.

During 1881-82, the swift urbanisation in Cape Town shifted local politics as new legislation was implemented to substitute municipal boards with municipal councils, granting them significant authority (Warren, Citation1986). The influence of ethnicity, wealth, and race were intertwined and impactful in shaping political and social dynamics. Early European property owners held significant power in ethnicity politics, favouring them greatly. Additionally, the ability to elect and be elected granted whites exclusive access to infrastructure benefits, creating a racial divide (Miraftab, Citation2012). The resulting superior powers based on ethnicity, wealth, and race led to the exclusion of other groups and people of colour, ultimately contributing to urban inequalities in the 20th century (Feinberg, Citation1993; Harvey, Citation2010; Turok et al., Citation2021). In the latter half of the 20th century, Cape Town underwent significant expansion, with the northern and southern suburbs emerging as preferred residential areas for the white middle and upper classes (Turok et al., Citation2021). However, the population density declined by an alarming 50% between the 1950s and 1980s, mainly due to the toxic racial ideologies that pervaded the society. Prior to this, racial segregation was not as rampant. Unfortunately, during the colonial period, the white settlers exploited indigenous groups and enslaved people, leading to segregation in many aspects of life (Christopher, Citation2005). Public health concerns in the early 1900s further exacerbated this situation, ultimately paving the way for extreme segregation policies after World War II. The impact of apartheid policies on the urban landscape in South Africa resulted in disparities like poor sanitation infrastructure (Maylam, Citation1995).

Racial attitudes characterised sanitation planning. Blackness was associated with filth, leading to the exclusion of blacks in sanitation planning, sanitation infrastructure provision, and segregation. Sanitation access was allocated based on wealth, property, and race and exacerbated by stereotypes that viewed blacks as dirty. It further fuelled segregation as the disease outbreaks, mainly smallpox, led to relocation of non-Europeans from the capital into specific zoned locations (Parnell, Citation1993). The removal of non-Europeans gave birth to the creation of wealth for the whites. People experiencing poverty complained about neglecting peripherals as these areas did not receive garbage collection services or sanitation development (Warren, Citation1986). Scholars like Mamdani (Citation2018), Miraftab (Citation2012), Ranger (Citation2007), and Watson (Citation2009) have argued that the current contestations in South Africa are deep-rooted in the past colonial arrangements of segregation and exclusion.

Due to segregated planning, the colonial administration in Cape Town focused on the development in the town centre, neglecting the peripherals. Warren (Citation1986) demonstrates how short markets and long streets were the first to be paved in what they viewed as a selective expenditure. Ward commissioners and ward masters assisted the colonial administration in running the colony. Due to marginalisation, the ward masters who oversaw collecting fees, counting the number of tenants, and overseers on behalf of colonialists would oppose the selective budgeting and demand for services to be in poorer areas. The contestation and conflict also arose as the demand for services between the municipal board and the colonialists over the responsibilities of each party (Bickford-Smith, Citation1983).

3.1. Colonial controlled expenditure

The demand for water supply services redefined 1842 and 1847 anticolonial struggles in Cape Town. The contestations over the responsibilities between the municipal board and the colonialists united the municipal board and ward commissioners. The municipal board and ward commissioners demanded that the colonial government pay for water services. However, the bid to force the colonial government to pay for its water services failed when it threatened to withdraw its financial muscle from the treasury (Bickford-Smith, Citation1983). The colonial government always aimed to reduce expenditure, sending profits to England. This means the colonial urban governments only intended to invest in areas beneficial to the colonial masters. Thus, it seems to suggest that even in the early years of colonialism, the development interests were much more focused on businesses and property than human and social development.

The demand for equal allocation of development ignited the struggle for an independent government with proper representation. The united group of municipal boards and commissioners’ boards pursued the struggle for an independent government. The changing composition aided the move, as some became increasingly wealthy (Bickford-Smith, Citation1983). As a result of the demand for independent government, Cape Town municipality became the first municipality to have representatives. Gaining representation was a significant victory for the middle class, who seemed to defend the interest of local businesses more than the elite merchants who worked for the colonial home country. Worth noting is that in colonial urban governance, only those who owned properties as landlords and paid rates had a say in the City’s affairs, meaning that people experiencing poverty were never involved. In this regard, colonial urban planning inequalities and practices resulted in the creation of slums. These were inspired by crucial drivers that I discuss in the following section.

4. Colonial practices and slums in South Africa

The emergence of slums in various cities in the global South is a matter of concern that demands attention (Ezeh et al., Citation2017). This issue appears to have existed for centuries, although it has been partly attributed to rapid urbanisation processes (Wurm et al., Citation2017; Wurm & Taubenböck, Citation2018). The work of Miraftab (Citation2012) demonstrates how urban space was a highly contested arena for politics and the protection of class interests. Colonial interests that sought to establish and maintain dominance and control over society were intricately tied to the built environment. While colonial accounts often emphasised the importance of ‘hygiene,’ more recent historical research has shown that urban infrastructure and municipal services were also highly contested arenas of political struggle (Baffoe & Roy, Citation2022; McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017; Miraftab, Citation2012). The influx of capital into Cape Town during this period only exacerbated class conflicts over the production and control of urban space. The decisions made about infrastructure development in the city ultimately shaped the structure of its first municipal government and consolidated class interests. The urbanisation of the Cape Colony during the 20th century was a critical factor in the development of Cape Town as an apartheid city, and it continues to shape the city’s struggles for urban development and redevelopment in the post-apartheid era (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017; Miraftab, Citation2012). The creation of elitist exclusionary urbanism is a crucial objective of urban governance in both eras, but the means for achieving this end differ. The analysis of the colonial practices suggests the four key drivers that promoted the production of slums during the colonial administration. The historical context surrounding the pandemic urbanisation and the Land Act of 1912 reveals the racial discrimination and inequality that dispossessed black people of their land and prevented them from participating in the economy. These key drivers were motivated by a racial intent that perpetuated systemic oppression and limited opportunities for black Africans.

4.1. Pandemic urbanisation

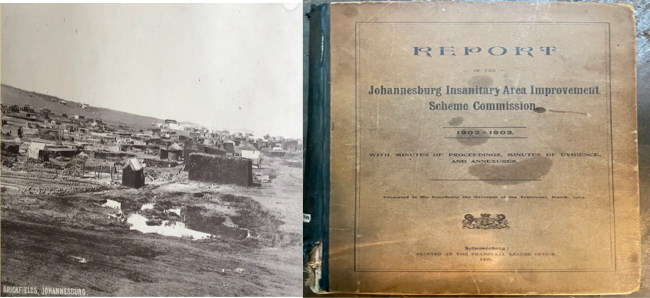

The early stages of urbanisation in pre-apartheid South Africa were instrumental in shaping the country’s current levels of inequality. The management of bubonic plague, tuberculosis, and Spanish influenza outbreaks in the early 20th century was closely intertwined with this process (Finn, Citation2022). This pandemic-induced urbanisation has had a lasting impact on South Africa’s social, economic and spatial injustice. Infectious diseases were used to enforce segregation and justify spatial policies in the name of public health. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Isolation stations were established for pandemic control in councils of Johannesburg and Cape Town (Gear, Citation1986; Viljoen, Citation1995). The outbreak of diseases like smallpox and bubonic plague enabled the colonial governments to implement disease control measures that led to segregation and slums. Disease outbreaks like smallpox and bubonic plague threatened workers’ crowded spaces and the Johannesburg town council neighbourhoods. The conditions of the workers’ living spaces soon became a concern to health practitioners. The Johannesburg town council was compelled to appoint ‘an Insanitary Area Improvement Commission’ in 1902 to inquire into the situation of ‘Brickfields – Burghersdorp’ deplorable structures of tin and iron (Callinicos, Citation1987, P.72; Mabin & Smit, Citation1992; Phillips, Citation2014).

Insanitary Area Improvement Scheme Commission report 1903 (Source: Johannesburg1912.com)

The government established a commission when the plague hit the towns and spread to the white areas. Hundreds of years ago, the plague killed many people in Europe and threatened wealthy whites in the Johannesburg town council. However, instead of improving the living conditions, the council relocated the workers to a location called ‘Nancefield’ out of town near the sewage dump (Callinicos, Citation1987, p. 72). This location of African people later developed into a township known as Orlando in the 1930s (now one of the suburbs of Soweto).

The outbreak of bubonic plague in 1901 saw mounting pressure and calls from ratepayers in Cape Town demanding the city to restrict blacks in white areas (Miraftab, Citation2012; Swanson, Citation1977). Though rats carried the plague, the outbreak was still blamed on blacks. Shortly after the outbreak, approximately 7,000 blacks were relocated to Ndabeni’s controlled location. The 1918 influenza epidemic increased calls from those who demanded that the location be removed and the inhabitants be taken out of the city. As Maylam (Citation1990) and Swanson (Citation1977) observe, the creation of Ndabeni emerged out of pressure exerted by the white community, who called for creating a location zone for black people. Therefore, the creation of Ndabeni resulted from segregation that pushed Africans out of the city and aimed at relegating Africans to slums. These practices shaped uneven urban development and encouraged the creation of slums.

4.2. Land act of 1912

The colonial government implemented laws that separated racial groupings on land, the electoral rolls, and residential areas. The proceeds of these policies also included the Natives (Urban Areas) Act, which was first discussed in 1912 and enacted in 1923. The act underwent several amendments until 1964 (Davenport, 1969, p97-98). The Land Act denied Africans the right to own land. The Land Act, followed by droughts, forced the African people to move to the Rand (currently Johannesburg) for work. This exodus of African people in search of work later created overcrowded slums with no services provided to these areas by the municipality (Callinicos, Citation1987). The municipalities provided good services to white areas, separate from where Africans lived. Africans were impoverished to pay rates, which meant they had no say in the municipality’s affairs and governance.

In colonial urban governance, those who owned properties as landlords and paid rates had a say in the City’s affairs. It meant black Africans lived in the city to provide cheap labour (Callinicos, Citation1987; Parnell, Citation1991). However, as per the British policy of division and rule, some Africans worked closely with the British and hence were given a special status (Mamdani, Citation2018). Even among the African working class, a different class started emerging. As capitalism started taking shape, Africans were even divided further along with social classes.

The emergence of industrialisation created two groups of workers - the skilled and the unskilled. The skilled workers lived in areas separate from where the unskilled lived and hence had better living conditions (Callinicos, Citation1987). However, the houses these workers lived in were small and paid low wages. To manage and survive on low salaries, these workers had to share their space to reduce the rent burden. It led to poor living conditions due to overcrowding.

4.3. Racial attitude

During the late 1800s, the burgeoning economy of Cape Town and the diamond mines in Kimberly attracted a growing number of African residents to the city. However, this influx of individuals caused concern among certain journalists who began warning of perceived dangers associated with Africans, leading to a discourse surrounding crime and sanitation (Miraftab, Citation2012). Swanson (Citation1977) analyses the turn-of-the-century Cape Town and highlights how the discourse of ‘segregation for sanitation’ became a means of justifying race-based segregation of Europeans and non-Europeans during times of epidemic emergency. The bubonic plague outbreak in South Africa between 1900 and 1904 led to the relocation of African urban populations to emergency locations under public health laws. However, administrative, legal, economic, and human factors hindered the consolidation of these moves, leading to contradictions in urban location policy.

In the 19th century, Medical Officers of Health in colonial Africa designated areas inhabited by native dwellers as ‘the septic fringe’ of the city, citing them as a medical menace (Miraftab, Citation2012). The anxieties surrounding hygiene and disease in the 20th century played a significant role in establishing a pattern of segregation between African and European urban communities, often separated by an uninhabited buffer zone during times of epidemic. Prior to the explicit racial segregation of apartheid, British colonial liberalism achieved selective urban inclusion and exclusion through political manipulation. Municipal development decisions were often tied to individual wealth and property ownership, and stereotypes were used to justify the exclusion of certain groups.

The segregation of Africans also occurred in other cities like Johannesburg. The colonial administrator Lord Milner appointed Charles Porter in 1901 as the first Johannesburg Medical Health Officer. Charles Porter argued that blacks were inferior, and their tribal habits made them less prepared to handle the health and social hazards in the city (Parnell, Citation1993, p.479). In this regard, Porter believed and saw restricted control of blacks as an integral part of public health control that would reduce overcrowding and transform urban sanitation.

4.4. Economic participation and inequality

The British colonial system restricted black Africans from economic participation and created the inequality witnessed in the urban peripheries of South African cities today. The native labourers were restricted access to major towns by the colonial administration and relegated to peri-urban settlements that were less planned (Baffoe & Roy, Citation2022). The neglect of peri-urban settlements by the colonial administration created a disaster for urban slums, creating a recipe for inequality. The emergence of unplanned and informal settlements in the urban periphery was due to colonial laws that led to natives’ tenure insecurity and resulted in the slums. The well-planned, spacious separate housing with fenced compounds was reserved for serving white privilege in the cities. Land dispossession and exploitation policies created ‘racialised poverty living side by side with wealth accumulation’ (Habiyaremye, Citation2022, p.25).

The restriction of natives in economic participation and planning practices produced a city geography based on race and characterised by underserviced areas for the blacks. Colonial urban planning and architecture created residential and racial zones with class segregation (Baffoe & Roy, Citation2022). People experiencing poverty were moved to the peripheries with limited sanitation services. Colonial policies and practices encouraged racial segregation around and beyond cities in pursuit of class and racial interests. In this regard, segregation was a political tool to promote and preserve white privilege.

5. Responses to poor sanitation under apartheid

The oppressive conditions forced black Africans to opt for resistance and boycotts. The unfair political and social-economic systems that characterised these regimes suppressed the blacks (Musemwa, Citation1993). The socio-economic situation faced by blacks in the South African townships led to resistance that increasingly gained momentum in the 1940s. Due to overcrowding, the sanitation situation in the townships started to get worse, and disease outbreaks like influenza and tuberculosis were a threat to the black population. These conditions were made worse with the colonial policies that limited the movements of blacks and finally attracted resentment from the oppressed. Musemwa (Citation1993) demonstrates how the burning of passes that started in the Langa Township ignited other townships, like Kayamandi in Stellenbosch, to follow suit. The demand and the message to the oppressor was to relieve them of restrictions like passes that limited their movements and progress.

The victory of the National Party (NP) as the ruling party in 1948 did not bring any good fortunes and hope to black people as one would have anticipated with the changing of guards. The party maintained the same restrictions of carrying passes and intensified the segregation of races through the apartheid system. The growing injustice forced the oppressed to mobilise African workers, mainly under the Pan African Congress (PAC). The fight against the pass-laws was very significant because the restrictions and segregation heavily affected the living conditions of black Africans.

In the 1940s, the segregation policies raised discontent from the black communities, and squatter movements started to gain momentum. Even before the 1940s, Maylam indicates how Africans campaigned against passes from 1910 until 1980, when the system started to show some ‘signs of breakdown’ (Maylam, Citation1990, p.78). The poor treatment of blacks in locations contributed to widespread squatter camps. In this regard, black Africans preferred to stay in squatter areas where they were more unrestrained without the supervision of white masters (Maylam, Citation1990).

In the 1940s and ‘50s, most Africans lived as squatters in Cape Town along the City’s peripheries in areas like Windermere. In the 1950s, Qotole (Citation2001) demonstrated how Africans manipulated the gaps within the system by squatting in the hope of getting housing. According to the law, the municipality could not remove squatters if they could not provide housing. However, the nationalists worked around the clock to change the law to enable local governments to implement removals. The Act of 1951, ‘Preventing of Illegal Squatting Act,’ and the ‘Natives Laws Amendment Act of 1952’ later aided local governments in banning squatting (Qotole, Citation2001, p.108). However, some resisted this move and demanded water and sanitation services. For instance, the crossroads squatters resisted removals; the government called it an emergency camp and provided amenities (Chadya, Citation2017).

In the years that followed, the ANC, in alliance with other organisations like the South African Indian Congress, Coloured People’s Congress, South African Congress of Democrats, and the South African Congress of Trade Unions, held a congress of the people in Kliptown Johannesburg and adopted a Freedom Charter in 1955(Alliance & SAC, Citation1955; Mazibuko, Citation2017). The Freedom Charter was significant in that, for the first time, African people gathered to plan their alternative society where the rights of everyone who lives in it are respected. The Freedom Charter is thus one of the action approaches undertaken by the African black people in response to the Urban Act that took away the rights of the natives – including rights to sanitation. The response to urban injustice was eminent as the oppressed black Africans carried out phases of resistance and boycotts.

6. Responses to poor service delivery post-1994

The transition to a democratic South Africa necessitated extending service delivery to all citizens to end segregation policies of colonial and apartheid capitalist development (Tsheola & Sebola, Citation2012). The attempt to change the past legacies of segregation in human development is evident in the 1996 South African constitution. Article One of the founding Constitution talks about the values of democratic government, such as human dignity, equality, advancing human rights and freedoms, voting rights, good governance, responsiveness and accountability, and so forth (RS 1996). The expectation of a better life for all was evident as people queued in long lines to vote for the ANC party that selected the first black president (Desai & Desāī, Citation2002). South Africa became a new democratic country with high regard for human values. In this regard, the understanding is that observing these values would form a basis for the social inclusion of previously marginalised communities. However, several studies have linked the recent wave of protests to the people’s general dissatisfaction with the constitutional promises of democratic rights (Jackson & Robins, Citation2018; Robins, Citation2014a).

The transitional justice mechanism, done through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), did not address issues affecting citizens’ everyday lives. By the late 1990s, the services of TRC, which seemed to build the broken bonds in the new South Africa, had left the political stage. Robins (Citation2014b, p.1) argues that what replaced TRC was a ‘mess’ ‘of popular politics’, obsessed with issues of sanitation, land, housing, service delivery, the condition of workers and employment equity. These issues about improving people’s everyday lives did not surface during the TRC and have come to characterise post-apartheid politics. Studies view the inequalities that ensued after the transition as an incomplete transition (Robins, Citation2014a; World Bank Group, Citation2018).

6.1. Sanitation planning in post-apartheid South Africa

The colonial and apartheid sanitation planning was highly centralised and served the whites and segregated blacks. Thus, the first task of post-apartheid South Africa under a transformative constitution was to decentralise the governance system through municipal governance structures, extending services to all South Africans, particularly blacks (Hattingh et al., Citation2007). In 1996, the national government began implementing new policies to establish sanitation systems in areas already occupied by black South Africans. The municipal governments were mandated to fulfil the promises enshrined in the Constitution by providing equitable services like water and sanitation. The policies to this effect included the ‘Water Services Act’ (WSA) of 1997, the ‘National Environmental Management Act’ (NEMA) of 1998, and the ‘National Water Act’ (NWA) of 1998. The Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) was mandated to offer these services through community programs for water supply and sanitation (Muller, Citation2003; Tissington, Citation2011). Implementing these programs suggested the government’s ambition to address the issue of water and sanitation and restore people’s dignity. In this regard, every South African would enjoy safe water and dignified sanitation services.

The decentralisation of essential services into the Municipal Systems Act began in 2000. Thereafter, local governments were responsible for delivering water and sanitation services to the residents within their jurisdiction. The local governments would use the Municipal Infrastructure Grant (MIG) approved by the national government to fund the water and sanitation programs intended to improve water supply and sanitation services. Alternatively, local governments would also use funds collected at the local level. Since 2003, sanitation has significantly improved across all provinces in South Africa. Some households have access to flush toilets, but some still use pit latrines and bucket systems (Alexander, Citation2010; Amisi & Nojiyeza, Citation2008; Atkinson, Citation2007; Robins, Citation2014b; Thompson & Conradie, Citation2011; Xabendlini, Citation2010). In urbanised provinces, mainly Gauteng and Western Cape, flush toilets are connected to the public sewerage systems. However, the state of these public toilets is contested, particularly those in informal settlements. The density of informal settlements poses security threats, especially at night, forcing residents to resort to bucket toilets as the only option to relieve themselves. The reality of bucket toilets was witnessed in 2013 when protestors carried buckets full of human waste to the legislature and Cape Town International Airport. Sanitation protests are common in most post-apartheid cities in South Africa, suggesting the continuity of urban planning history.

These protests indicate the state of progress since the transition into democracy. From the onset, the democratic government was committed to transforming the lives of formerly segregated groups by providing free essential services. However, from 1994 to 1999, the government received criticism from the organisations like COSATU, SASCO, and SANCO (Naidoo, Citation2010, p.128) because of policy changes from Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) to Growth Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) that dramatically increased the number of poor people evicted. Another contestation arose from the students and community protests as government policies were questioned about whether they were pro-poor (Bond, Citation2000). For instance, in the protest in Eldorado Park, a coloured township in 1997 that resulted in the death of 4 people, the residents demanded lower municipal rates on essential services (Naidoo, Citation2010). The adoption of the RDP of 1994 raised expectations (Naidoo, Citation2010) and hope for many South Africans who were forcefully dispossessed of their land and properties and lacked necessities (Desai & Desāī, Citation2002). The RDP set ambitious targets to provide essential services like ‘housing, land redistribution, electricity, water supply, sanitation, health care, education, nutrition and environmental, telecommunication services, transport’ within five years (Blumenfeld, 1997, p, 70). The sudden abandoning of RDP for GEAR in 1996 is viewed as ‘a gradual embracing of neoliberalism’ (Adelzadeh, Citation1996. p, 66) that crushed the dreams and hopes of the poor and the marginalised. In what appears to be a neoliberal environment, the challenges of sanitation delivery still linger in post-apartheid cities like Cape Town.

6.2. Cape Town, in the post-apartheid era

Cape Town, like any other city in South Africa after apartheid, was faced with the daunting task of dealing with the spatial division created over three centuries of colonial and apartheid regimes. Furthermore, the city attempted to address poverty produced by spatial divisions (Sibanda, Citation2018, p.173; Swilling & De Wit, Citation2010, p. 25). Towards 1994, the City of Cape Town had fragmented governance structures. It was governed by 61 municipalities, separately managed by 17 administrations (Sibanda, Citation2018; Swilling, Citation2010; Swilling & De Wit, Citation2010). It changed during the first local government elections in 1995-1996 in integrated municipal areas (Swilling, Citation2010) as part of post-1994 reforms. The new system of metropolitan government was later outlined by the Municipal Structures (Act no. 117 of 1998 as amended Act no. 33 of 2000), leading to the establishment of unicity Cape Town. The unified structure secured a single metropolitan tax base to solve development disparities (Swilling & De Wit, Citation2010, p. 25). It ensured the amalgamation of the previously segregated white and black local authorities to ensure outstanding equity between affluent and poor communities. Chapter 8, Section 73(2) of the Municipal Services Act emphasises that services must be equitable and accessible (Tissington, Citation2011). However, as one of the post-apartheid cities, Cape Town faced a considerable challenge to transform and deracialise the city’s governance to deliver the promises in a new political environment. Nevertheless, the City’s emphasis on a cost recovery plan of service delivery is considered a neoliberal approach.

Robins’s (Citation2014a) research on ‘Toilet Wars’ in Cape Town reveals how the dispute unfolded in the context of broader societal issues, such as the legacy of apartheid, racial tensions, and political struggles. In this regard, disparities in post-apartheid cities are still alive and require understanding contextual, socio-economic, and political progress in urban South Africa.

6.3. Disparities in sanitation delivery

Despite the efforts to address sanitation delivery issues in all parts of the city, the constraints of uneven resource distribution still exist. Bridging this gap requires ‘effective social policies that address disparities and support social and economic justice for all people’ (Segal, Citation2011, p. 266). Some of the commonly contested disparities are discussed below.

6.3.1. Shared public toilets in the informal settlements

The politics of public toilets in the City of Cape Town is very complex and perhaps tells the story of transitional challenges. It appears to be defined by the spatial planning of the past colonial and apartheid regimes. Traversing across Cape Town, one would realise a differentiation in public toilets based on location, social class, and race. It is a point of contention between urban authorities and community activists in poor communities’ particularly informal settlements (Robins, Citation2014b). The comparison between public toilets in privileged areas like Sea Point and public/shared toilets in informal settlements is glaring (Social Justice Coalition, Citation2014). On 20 March 2010, during the World Toilet Day celebrations, approximately 600 people lined up at Sea Point public toilets that are well maintained and well-guarded simply to demonstrate how it feels when many families use one toilet (Overy, Citation2013). On Freedom Day, 26th April 2011, approximately 2500 activists and community members lined up on temporary toilets positioned in front of the Civic Centre by SJC to highlight the dilemma of access to sanitation in the informal settlements.

In 2011, the informal settlement residents and activists transported raw sewage in bucket toilets to the major tourist routes and legislature. The weaponisation of raw sewage surprised voters on the eve of the local government election in 2011. The smell exported from the city fringes to the central business area, freeways (N2), and tourist sites like airports (Robins Citation2014a) demonstrated the never-ending struggle for social justice. The activists highlighted the sanitation situation in Khayelitsha’s informal settlements. The protestors blocked the N2 highway that connects most of the workers and owners of the capital to Cape Town Central Business District (CBD). The protestors also poured sewage at the Cape Town Airport and the provincial legislature (Redfield & Robins, Citation2016). The buckets of poo were carried to these strategic places of the city to demonstrate the dignity that residents in informal settlements still experience. The existence of bucket toilets tells the levels of inequality in a post-apartheid city.

6.3.2. Budget allocation for informal settlements

The contestation around budgeting in Cape Town dates to the colonial era. Budget allocation often ignited contestation in colonial South Africa as the city centre/CBD received huge budgets at the expense of other areas outside the city. Similarly, the post-1994 budget contestation focuses on the money allocated to affluent areas versus the amount allocated to informal settlements. In 2011, the Khayelitsha community activists held a sanitation summit focusing on the City’s accountability and budget allocation processes (Kramer, Citation2017). The toilet queuing of activists and informal settlement residents in Sea Point 2011 claimed that the city had spent R770,000 (equivalent to US$ 95,000) on improving public toilets.

In contrast, many people in informal settlements still used bushes to relieve themselves (Overy, Citation2013). The City of Cape Town allocated less than 2% of its water and sanitation budget in 2015 and invested vast sums of money in maintaining services in affluent neighbourhoods (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017). Though the infrastructural governance of colonialism and apartheid ended, it continues to exist through apartheid geography.

The activists further submitted to the ‘budget steering committee’ a proposal for the janitorial services the city had proposed offering to the informal settlement residents (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017; Kramer, Citation2017). The issue of budgeting has become an essential aspect of activism engagements with the city authority and with the help of partners like the International Budget Partnership (IBP) undertaking training of their members on budgeting (Kramer, Citation2017). The goal is to teach the activists how the city allocates the budget for sanitation in informal settlements and affluent areas. Understanding budget allocation helps activists engage in the process. However, the activists claim that it is challenging to access city information regarding sanitation budget allocation (Social Justice Coalition, Citation2014). The city views informal settlements as temporary; hence, they argue it is only viable to invest a little money (Kramer, Citation2017; Taing, Citation2017). On the other hand, activists persistently argue that most of these settlements have existed for many years and thus should be considered permanent or upgraded.

6.4. Mapping sanitation protest and achievements in Cape Town

Sanitation protests in Cape Town are well documented through newspapers and scholarship work. Nevertheless, the protest narratives lean on the power struggles and politics in the townships, neglecting the context through which the climax of the protests began. In the last decade, Cape Town has broadly experienced sanitation protests by the community residents of Khayelitsha. The contestations emerged after the 2008 xenophobic attacks that left thousands of foreign nationals dead, injured, and displaced. The unprecedented level of violence caught the attention of community activists, who assessed the level of community social intolerance. In 2008, loose organisations in the area met to deliberate the causes of xenophobia. After consideration, it was clear that the worsening social conditions in the informal settlements triggered the anger of those who felt that the cause of poverty was the presence of foreign nationals taking their jobs.

However, the activists realised there was more to violence than just foreigners taking away their jobs. The meeting revealed sanitation and safety issues, which created anger and frustration (Social Justice Coalition, Citation2014). A recent study claims that to minimise the number of protests, municipalities need to increase the provision of essential services like sewerage and sanitation, housing, refuse removal, electricity, and so forth. (Morudu, Citation2017). In this regard, SJC emerged out of social and economic conditions that necessitated loose organisations to form one stronger voice to engage the city administration on the plight of the affected communities.

In 2009, the SJC launched a sanitation campaign. The campaigns demanded access to clean water and dignified and sustainable toilets. This coalition engaged different city structures responsible for the sanitation infrastructure in the informal settlements. On 27 April 2011, an estimated 2,500 members of SJC and other coalition partners marched to the CBD. They camped at the mayor’s office to demand attention to the deteriorating sanitation conditions in the informal settlements (Kramer, Citation2017). On the same day, a ‘petition signed by more than 10,000’ Khayelitsha residents was submitted to the City Mayor (Overy, Citation2013, p.15). The petition called for ‘both interim and long-term plans’ regarding sanitation in the informal settlements. These demands received a positive response from the Mayor as the City agreed to offer janitorial services to the Khayelitsha settlements that lacked services. The city also promised to employ 500 people in the janitorial program, particularly those in marginalised communities (Overy, Citation2013; Taing, Citation2017).

Several other campaigns included police resources, demanding a commission of inquiry into policing in KhayelitshaFootnote2. It was popularly known as the O’Regan-Pikoli Commission of InquiryFootnote3. Through engagements with communities, the SJC activists established that policing is vital to sanitation in informal settlements due to safety reasons. Shared public toilets in informal settlements are often far from people’s homes, making them dangerous to use at night due to a lack of lighting. In this regard, public policing and streetlights formed part of sanitation campaigns as more testimonies from residents indicated that many were dying while using toilets. Lack of visible policing and shortage of staff are some of the challenges that affect informal settlements (Turok et al., Citation2023). The campaign on community policing started in 2011 when activists approached the Western Cape Government to establish a commission to examine individual cases where rights were violated. The commission took place after an unsuccessful court challenge by the minister of police to stop the proceeding or weaken its powers. It was a significant battle won by the Khayelitsha community and the activists representing them in court.

The third campaign, SJC10, applied civil disobedience to compel the city to engage the activists. On 11 September 2013, 21 activists chained themselves in front of the Cape Town Civic Centre at the Mayor of Cape Town’s office. The group was arrested and charged with breaking Section 12(1) of the Gatherings Act (CGA), which they challenged in court as unconstitutional and a remnant of apartheid regulation. The final judgment ruled, declaring the act unconstitutional. The ruling stated that:

The criminalisation of a gathering of more than 15 on the basis that no notice is permitted violates s 17 of the Constitution as it deters people from exercising their fundamental right to assemble peacefully and unarmed…the limitation is not reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society, based on the values of freedom, dignity, and equality…Section 12 (1) (a) of the RGA is hereby declared unconstitutional.

People who lack political and economic power have only protested as a tool to communicate their legitimate concerns. Taking away that tool would undermine the promise in the Constitution’s preamble that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, not only a powerful elite. It would also frustrate a stanchion of our democracy: public participation. This is all the more pertinent given the recent increasing protest rates in constitutional South Africa.

7. Conclusion

The issue of sanitation services in South Africa is not a simple one. It is a complex and multifaceted problem influenced by various historical, social, and political factors. The legacy of colonialism and apartheid still casts a shadow over the country, particularly in informal settlements where access to sanitation is often inadequate. Despite efforts to address these inequalities through post-1994 policies, historical disparities, and spatial planning continue to pose significant challenges. A holistic and synergistic approach that considers past legacies and current urban realities is necessary to tackle this crisis effectively. It is crucial, however, to acknowledge the limitations of historical data and the unique context of South Africa when concluding. Further research into social and cultural factors, policy dynamics, and spatial considerations is needed to develop a more comprehensive understanding of this issue. Furthermore, a deeper exploration of specific case studies, alternative solutions, and the engagement between technocrats and politicians could enhance our understanding of the sanitation problem in South Africa and the potential paths forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alex Kihehere Mukiga

Alex Kihehere Mukiga is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State, South Africa. His research interests include public policy, community participation, social movements, local governance and service delivery, sanitation politics in post-colonial cities, informal settlements upgrading, urban planning and development, health disparities, climate change, and regenerative design in the built environment.

Notes

1 In the summer of 1858, London was hit by a severe and persistent foul odour that became known as the ‘Great Stink.’ This terrible smell was caused by raw sewage the industrial effluent dumped directly into the Thames River. It was so bad that it became a major public health crisis and a significant environmental problem. The people of London were desperate for a solution to this problem, and it eventually led to the creation of a new sewage system that would prevent such a disaster from happening again.

2 The campaign on police resources was very significant to the sanitation campaign because safety and security are essential components of sanitation in informal settlements. The public toilets are far from home, and using them in the dark at night is precarious. There have been instances where residents get raped, hurt, and murdered while trying to use toilets.

3 See the SJC Website available at: https://sjc.org.za/campaigns/police-resources

References

- Adelzadeh, A. (1996). From the RDP to GEAR: The gradual embracing of neo-liberalism in economic policy. Transformation, 31(4), 1–16.

- Alexander, P. (2010). Rebellion of the poor: South Africa’s service delivery protests–a preliminary analysis. Review of African Political Economy, 37(123), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056241003637870

- Alliance, SAC. (1955). The freedom charter. In As adopted by the Congress of the People (vol. 26).

- Amisi, B., & Nojiyeza, S. (2008). Access to decent sanitation in South Africa: The challenges of eradicating the bucket system. In AfriSam Conference.

- Atkinson, D. (2007). Taking to the streets: Has developmental local government failed in South Africa? In S. Buhlungu (Eds,). State of the nation: South Africa 2007. Human Sciences Research Council.

- Baffoe, G., & Roy, S. (2022). Colonial legacies and contemporary urban planning practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Planning Perspectives, 38(1), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2022.2041468

- Bickford-Smith, V. (1983). Keeping your own council: The struggle between houseowners and merchants for control of the Cape Town municipal council in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town.

- Bond, P. (2000). Cities of gold, townships of coal: Essays on South Africa’s new urban crisis. Africa World Press.

- Callinicos, L. (1987). Working life, 1886-1940: Factories, townships, and popular culture on the rand (vol. 2). Ravan Press of South Africa.

- Campante, F. R., & Chor, D. (2012). Why was the Arab world poised for revolution? Schooling, economic opportunities, and the Arab Spring. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(2), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.2.167

- Chadya, J. M. (2017). Making freedom: Apartheid, squatter politics, and the struggle for home by anne-maria makhulu.

- Christopher, A. J. (2005). The slow pace of desegregation in South African Cities, 1996-2001. Urban Studies, 42(12), 2305–2320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500332122

- Desai, A., & Desāī, A. (2002). We are the poor: Community struggles in post-apartheid South Africa. NYU Press.

- Ezeh, A., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Chen, Y.-F., Ndugwa, R., Sartori, J., Mberu, B., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Haregu, T., Watson, S. I., Caiaffa, W., Capon, A., & Lilford, R. J. (2017). The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet (London, England), 389(10068), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6

- Feinberg, H. M. (1993). The 1913 natives land act in South Africa: Politics, race, and segregation in the early 20th century. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 26(1), 65–109. https://doi.org/10.2307/219187

- Finn, B. M. (2022). Pandemic urbanisation: How South Africa’s history of labour and disease control creates its current disparities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 45(3), 616–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2022.2101468

- Fourchard, L. (2024). Comparative Urban Studies and African Studies at the Crossroads: From the Colonial Situation to Twilight Institutions. In The routledge handbook of comparative global urban studies (pp. 58–72). Routledge.

- Gear, J. H. S. (1986). The history of virology in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 70(4), 7–10.

- Godsell, G., Chikane, R., & Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2016). Fees must fall: Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa. NYU Press.

- Gwaindepi, A., & Fourie, J. (2020). Public sector growth in the British cape colony: Evidence from new data on expenditure and foreign debt, 1830‐1910. South African Journal of Economics, 88(3), 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12257

- Habiyaremye, A. (2022). Racial capitalism, ruling elite business entanglement and the impasse of black economic empowerment policy in South Africa. African Journal of Business Ethics, 16(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.15249/16-1-298

- Hall, P. (2014). Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design since 1880. John Wiley & Sons.

- Harvey, D. (1976). Social Justice and the city. Blackwell.

- Harvey, D. (2010). Social justice and the city (vol. 1). University of Georgia Press.

- Hattingh, J., Maree, G. A., Ashton, P. J., Leaner, J. J., Rascher, J., & Turton, A. R. (2007). Introduction to ecosystem governance: Focusing on Africa. Water Policy, 9(S2), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2007.047

- Horn, A. (2019). The history of urban growth management in South Africa: Tracking the origin and current status of urban edge policies in three metropolitan municipalities. Planning Perspectives, 34(6), 959–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1503089

- Jackson, S., & Robins, S. (2018). Making sense of the politics of sanitation in Cape Town. Social Dynamics, 44(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2018.1437879

- Kramer, D. (2017). Building power, demanding justice: The story of budget work in the social justice coalition’s campaign for decent sanitation. International Budget Partnership.

- Mabin, A., & Smit, D. (1992). Reconstructing South Africa’s cities 1900-2000: A prospectus (or, a cautionary tale).

- Mamdani, M. (2018). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press.

- Marais, L., & Cloete, J. (2016). Patterns of territorial development and inequality from South Africa’s periphery: Evidence from the Free State Province. Working Paper Series N° 188. Rimisp, Santiago, Chile.

- Mashe, T., Domman, D., Tarupiwa, A., Manangazira, P., Phiri, I., Masunda, K., Chonzi, P., Njamkepo, E., Ramudzulu, M., Mtapuri-Zinyowera, S., Smith, A. M., & Weill, F.-X. (2020). Highly resistant cholera outbreak strain in Zimbabwe. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(7), 687–689. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2004773

- Maylam, P. (1990). The rise and decline of urban apartheid in South Africa. African Affairs, 89(354), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098280

- Maylam, P. (1995). Explaining the apartheid city: 20 years of South African urban historiography.Journal of South ern African Studies, 21(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079508708431

- Mazibuko, S. (2017). The Freedom Charter: The contested South African land issue. Third World Quarterly, 38(2), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1142368

- McFarlane, C., & Silver, J. (2017). The Poolitical City:"Seeing sanitation" and making the urban political in Cape Town. Antipode, 49(1), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12264

- Miraftab, F. (2012). Colonial present: Legacies of the past in contemporary urban practices in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Planning History, 11(4), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513212447924

- Morudu, H. D. (2017). Service delivery protests in South African municipalities: An exploration using principal component regression and 2013 data. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1329106. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1329106

- Muchadenyika, D. (2020). Seeking urban transformation: Alternative Urban futures in Zimbabwe. Weaver.

- Muchadenyika, D., & Williams, J. J. (2016). Social change: Urban governance and urbanisation in Zimbabwe. Urban Forum, 27(3), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-016-9278-8

- Muller, M. (2003). Public–private partnerships in water: A South African perspective on the global debate. Journal of International Development, 15(8), 1115–1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1055

- Musemwa, M. (1993). Aspects of the social and political history of Langa township, Cape Town, 1927-1948 [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cape Town.

- Mutyaba, M. (2022). From voting to walking: The 2011 walk-to-work protest movement in Uganda. In Popular protest, political opportunities, and change in Africa (pp. 163–180). Routledge.

- Naidoo, P. (2007). Struggles around the commodification of daily life in South Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 34(111), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240701340340

- Naidoo, P. (2010). The making of ‘the poor in post-apartheid South Africa: A case study of the City of Johannesburg and Orange Farm [Doctoral dissertation].

- Norvixoxo, K., Schroeder, M., & Spiegel, A. (2022). Experiential approaches to sanitation-goal assessment: Sanitation practices in selected informal settlements in Cape Town, South Africa. Urban Water Journal, 20(10), 1744–1755. https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2022.2061360

- Overy, N. (2013). The social justice coalition and access to basic sanitation in informal settlements in Cape Town, South Africa. International Budget Partnership Impact Case Study, Study, (11). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2333670

- Parnell, S. (1991). Sanitation, segregation and the Natives (urban areas) Act: African exclusion from Johannesburg’s Malay location, 1897–1925. Journal of Historical Geography, 17(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-7488(05)80003-9

- Parnell, S. (1993). Creating racial privilege: The origins of South African public health and town planning legislation.Journal of South ern African Studies, 19(3), 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079308708370

- Penner, B. (2010). Flush with inequality: Sanitation in South Africa. Places Journal, (2010). https://doi.org/10.22269/101118

- Phillips, H. (2014). Locating the location of a South African location: The paradoxical pre-history of Soweto. Urban History, 41(2), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926813000291

- Pillay, S. R. (2016). Silence is violence: (Critical) psychology in an era of Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316636766

- Qotole, M. (2001). Early African Urbanisation in Cape Town: Windermere in the 1940s and 1950s. African Studies, 60(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020180120063674

- Ranger, T. O. (2007). City versus state in Zimbabwe: Colonial antecedents of the current crisis. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1(2), 161–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050701452390

- Redfield, P., & Robins, S. (2016). An index of waste: Humanitarian design, “dignified living” and the politics of infrastructure in Cape Town. Anthropology Southern Africa, 39(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2016.1172942

- Robins, S. (2014a). The 2011 toilet wars in South Africa: Justice and transition between the exceptional and the every day after apartheid. Development and Change, 45(3), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12091

- Robins, S. (2014b). Poo wars as matter out of place: ‘Toilets for Africa’in Cape Town. Anthropology Today, 30(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12081

- Segal, E. A. (2011). Social empathy: A model built on empathy, contextual understanding, and social responsibility that promotes social justice. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(3), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.564040

- Sibanda, D. (2018). Urban land tenure, tenancy and water and sanitation services delivery in South Africa.

- Smith, A. M., Sekwadi, P., Erasmus, L. K., Lee, C. C., Stroika, S. G., Ndzabandzaba, S., Alex, V., Nel, J., Njamkepo, E., Thomas, J., & Weill, F. X. (2023). Imported Cholera Cases, South Africa, 2023. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 29(8), 1687–1690. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2908.230750

- Social Justice Coalition. (2014). Our toilets are dirty: Report of the social audit into the janitorial service for communal flush toilets in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. http://nu.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Social-Audit-report-final.pdf

- Swanson, M. W. (1977). The sanitation syndrome: Bubonic plague and urban native policy in the Cape Colony, 1900–1909. Journal of African History, 18(3), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700027328

- Swanson, M. W. (1995). The sanitation syndrome: Bubonic plague and urban native policy in the Cape Colony, 1900-1909. In Segregation and Apartheid in Twentieth-Century South Africa, (1st ed., p 18. Routledge.

- Swilling, M. (2010). Sustaining Cape Town: Imagining a livable city. Sun.

- Swilling, M., & De Wit, M. P. (2010). Municipal services, service delivery and prospects for sustainable resource use in Cape Town. In Swilling, M. (Ed.), Sustaining Cape Town. Imagining a liveable City. Sun Media.

- Taing, L. (2017). Informal settlement janitorial services: Implementation of a municipal job creation initiative in Cape Town, South Africa. Environment and Urbanization, 29(1), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247816684420

- Thompson, L., & Conradie, I. (2011). From poverty to power? Women’s participation in intermediary organisations in site C, Khayelitsha. Africanus, 41(1), 43–56.

- Tissington, K. (2011). Basic sanitation in South Africa: A guide to legislation, policy and practice. Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa.

- Tsheola, J. P., & Sebola, M. P. (2012). Post-apartheid public service delivery and the dilemmas of state capitalism in South Africa, 1996-2009. Journal of Public Administration, 47(si-1), 228–250.

- Turok, I., Visagie, J., & Scheba, A. (2021). Social inequality and spatial segregation in Cape Town. Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality: A Global Perspective, (1), 71–90.

- Turok, I., Visagie, J., & Scheba, A. (2023). Stark neighbourhood divides in Cape Town raise uncomfortable questions. https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/20646/9812883.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Van Noorloos, F., & Kloosterboer, M. (2018). Africa’s new cities: The contested future of urbanisation. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 55(6), 1223–1241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017700574

- Viljoen, R. S. (1995). Disease and society: VOC Cape Town, its people and the smallpox epidemics of 1713, 1755 and 1767. Kleio, 27(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00232089585310031

- Warren, D. (1986). Merchants, commissioners and wardmasters: Municipal politics in Cape Town, 1840-1854 [Doctoral dissertation].

- Watson, V. (2009). The planned city sweeps the poor away…’: Urban planning and 21st-century urbanisation. Progress in Planning, 72(3), 151–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002

- World Bank Group. (2018). Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: An assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities. World Bank.

- Wurm, M., & Taubenböck, H. (2018). Detecting social groups from space–Assessment of remote sensing-based mapped morphological slums using income data. Remote Sensing Letters, 9(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/2150704X.2017.1384586

- Wurm, M., Taubenböck, H., Weigand, M., & Schmitt, A. (2017). Slum mapping in polarimetric SAR data using spatial features. Remote Sensing of Environment, 194, 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.03.030

- Xabendlini, M. T. (2010). An examination of policy implementation of water and sanitation services in the City of Cape Town: A case study of the informal settlements in the Khayelitsha area [Doctoral dissertation].

- Yende, N. E., & Mkhwanazi, A. (2023). Service delivery impasses in the midst of the covid-19 national lockdown in South African informal settlements. Journal of Public Administration, 58(1), 43–56.