?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study assessed the most effective mechanisms of bylaws implementation in sustainable potato production in Southwestern Uganda. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Southwestern Uganda. A mixed-method approach was used to collect data involving structured questionnaires administered to 104 potato farmers (93% response rate), key informant interviews (nine), and focus groups (six). Quantitative data from Epidata 3.1 was exported to STATA 13.0 for coding, cleaning, and analysis. Qualitative data was analysed using thematic content analysis in Atlas.ti version 7.5. Multivariate linear regression revealed that farmers’ level of implementation of improved and quality seed potato bylaws (β = −0.013; p < 0.05; CI: −0.026; −0.000), farmer roles (β = −0.127; p < 0.001; CI: −0.176; −0.084), and practising both crop and livestock farming (β = −0.129; p < 0.01; CI: −0.219; −0.038) was negatively and significantly associated with bylaw effectiveness. Bylaw effectiveness decreased by 1.3% for any additional seed, soil and water, and market access bylaw. Likewise, bylaws were 12% less effective per any additional farmer role, p < 0.001. Farmers who did crop and livestock farming had 12.1% lower bylaw effectiveness than those who only did crop farming. The effectiveness of bylaw implementation decreased with every additional bylaw, farmer role, and land use practice. The study recommends that potato value chain actors develop networks to harmonise bylaws, farmer roles, and land-use synergies to improve bylaw effectiveness.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Globally, only one-third of the world’s farms practice sustainable crop intensification (Cook et al., 2015; Godfray & Garnett, Citation2014; Pretty & Bharucha, Citation2014; Pretty, Citation2008). As such, food production has not kept pace with the growing population’s demand (FAO, Citation2017), posing a greater challenge for sustainable food systems. The increasing demand for food production is inhibited by financial availability, especially among smallholder farmers in developing countries such as Sub-Saharan Africa (Kapari et al., Citation2023). The limited adoption of sustainable farming practices has resulted in overexploiting natural resources, climate change, and food insecurity (Doughty, Citation2013; Hendry et al., Citation2017; Hove et al., Citation2020). This is evident with increasingly poor land productivity, low production output, and food shortages amidst exponential population growth (Fungo, Citation2011; United Nations, Citation2019), and it underpins the need for bylaws.

Bylaws are essential in shaping behaviour that supports sustainable crop intensification in densely populated areas (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004; Nkonya et al., Citation2008; North, Citation1990). The highland area of Southwestern Uganda (SWU) is densely populated, relying on smallholder farming for food and income security. This poses challenges such as limited land availability, soil erosion, and overutilisation of natural resources. The high population density puts pressure on the already limited land, leading to fragmentation of farms and reduced agricultural productivity. Arable land is progressively diminishing as the population increases by a national average of 3% annually, with potatoes as a major food and cash crop (FAO, Citation2017; Uganda Bureau of Statistics [UBOS], Citation2021). However, in recent years, the area has experienced diminishing land productivity due to a combination of factors, including degradation of arable land by the rapidly growing population, land shortages, poor seed quality, poor yields, effects of climate change, limited knowledge by smallholder farmers on potato production, poor market access, low use of external inputs, and poor physical infrastructure (Friedrich & Kassam, Citation2016; Fungo, Citation2011; Lampkin et al., Citation2015; Schneider et al., Citation2022). These challenges have had a significant impact on potato production in Uganda. The degradation of arable land, combined with land shortages, has made it increasingly difficult for farmers to cultivate potatoes and has resulted in declining yields.

Sustainable crop intensification (SCI) has been fronted as a response to these challenges (Godfray, Citation2015; Otsuka & Place, Citation2014; Pretty et al., Citation2011; Vanlauwe et al., Citation2014). SCI aims to increase the productivity of crops without causing further harm to the environment. One approach is to adopt environmentally friendly farming practices, such as organic farming or precision agriculture, which reduce synthetic inputs and optimise resource utilisation. Furthermore, SCI is one of the ways of ensuring food availability, especially among smallholder farmers, hence contributing to achieving sustainable development goal No. 2 of realising zero hunger by 2030 (Foresight, Citation2011; Otsuka & Place, Citation2014). In this study, SCI was defined as increasing the output of agricultural production, processing and commercialisation activities while at the same time increasing the efficiency of natural, physical, financial and human resource investments and reducing negative environmental and social impacts (Pretty et al., Citation2011). SCI is an essential aspect of sustainable development as it ensures that agricultural activities are carried out to maximise productivity without compromising the well-being of the environment and society. Farmers can achieve higher yields by adopting SCI practices while minimising the use of inputs such as water, fertilisers, and pesticides. Moreover, SCI also promotes the adoption of techniques that enhance the livelihoods of farmers and rural communities, leading to a more equitable and inclusive agricultural system. SCI was operationalised as soil and water conservation, improved and quality seed potatoes, and market access.

However, implementation of SCI requires policy and institutional strengthening investment to enable adoption and adaptation to be appropriate and best practices for reducing low output risks, like using bylaws and determining their effectiveness (Agrawal, Citation2008; Ostrom, Citation1990). Bylaws were defined as rules or regulations initiated by local communities and passed by local governments at district or lower levels through local government council resolution (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004; Koffi & Kalinganire, Citation2016; Mowo et al., Citation2016; Nkonya et al., Citation2005; Sanginga et al., Citation2009). These bylaws could be formal or informal (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004; Yami & Van Asten, Citation2018). Formal bylaws are legally binding and enforceable, while informal bylaws are based on customary practices and social norms. Both types of bylaws play a crucial role in regulating community behaviour and resource management, especially in the context of natural resource governance and sustainable development. However, the effectiveness of these bylaws largely depends on their enforcement mechanisms, community participation, and the degree of trust and cooperation among community members.

The main potato-growing districts in Southwestern Uganda, by the nature of their landscape, have taken on initiatives to formulate and implement bylaws relevant to sustainable potato intensification to address their major constraints (Sanginga et al., Citation2003, Citation2004). Moreover, effective bylaw implementation mechanisms to support sustainable crop intensification are the central focus of this study.

In the case of Uganda, the grassroots legislative bodies that enact bylaws are Local Council I (LCI) and Local Council III (sub-county) (Nkonya et al., Citation2005; Sanginga et al., Citation2010). Formal bylaws are widely recognised as official legal provisions formulated by groups and organisations to legally define within and outside the group, documented as a point of reference for specific behaviour of groups, aimed at meeting collective needs, and apply strict monitoring and supervision to meet their highly coordinated mandate (Bond & Heimlich, Citation2014; Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004; Nkonya et al., Citation2005). Informal bylaws are not only unofficial laws that govern group behaviour but also undocumented and unregistered or may be registered without documentation that generates shared expectations and strategic solutions (Bond & Heimlich, Citation2014; Carey, Citation2000; Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004). The operationalisation of informal bylaws occurs without registration by local authorities, irrespective of the geographical context. The informal structure or arrangement tends to cover self-governing groups with an active membership, flexible decision-making, promoting members’ individuality and entrepreneurship, and supporting mainstream supply chains.

Despite the ongoing debate in the literature on bylaws, researchers have a consensus on the need for effective bylaws to enhance SCI (Nedessa et al., Citation2005; Yami & Van Asten, Citation2018). Thus, the subject of this study was to assess the effective bylaw implementation mechanisms to support sustainable potato production in Southwestern Uganda. The specific objectives of this study are to (1) assess farmers’ awareness of bylaws on Sustainable Crop Intensification, (2) evaluate the implementation of the existing bylaws, (3) understand farmers’ roles in the implementation of bylaws, and (4) assess farmers’ resources in the implementation of bylaws for SCI. This study contributes to expanding knowledge and practice to understand bylaws governing SCI in potato production under the overall legal framework of the agricultural sector. The study addresses gaps in the effective implementation of bylaws to support the sustainable intensification of potato production.

2. Conceptual framework

North’s (Citation1990) theory on new institutionalism was the most influential in this study. According to North, rules are central to the proper functioning of groups, in this case, potato farmers, and thus can influence sustainable crop intensification. This is based on the idea that every human action can be explained by the actions of a single actor whose interactions with the structures legitimise the institutions, which lies the foundation of the new institutionalism (Vargas-Hernandez, Citation2008). According to new institutionalism, the social, political, and economic structures influencing individual actors impact their behaviour. These structures provide the norms, rules, and incentives that guide individual actions within institutions.

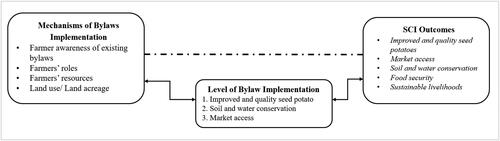

Bylaws can support sustainable crop intensification. The implementation of Sustainable crop intensification necessitates investment in policy, such as bylaws and institutional strengthening, to facilitate the adoption and adaptation of appropriate and best practices for mitigating low output risks (Nkonya et al., Citation2005; Sanginga et al., Citation2010; Yami & Van Asten, Citation2017, Citation2018). This includes evaluating the mechanisms of effective bylaw implementation mechanisms (Agrawal, Citation2008; Ostrom, Citation1990). The bylaws have been categorised per the objective they tend to achieve: improved and quality seed potato, soil and water conservation, and market access. However, the level of implementation of these bylaws and extent of effectiveness is affected by various mechanisms, including farmer awareness of existing bylaws, roles, resources and land use/land acreage. The mechanism of bylaws implementation is crucial in enhancing their effectiveness. By examining the mechanisms of effective bylaw implementation, policymakers and decision-makers can gain insights into their potential effectiveness and make informed choices regarding their implementation and enforcement. This research contributes valuable information to future policy and decision-making processes aimed at promoting sustainable agricultural practices in Southwestern Uganda. This assessment identifies areas where improvements can be made to ensure the bylaws effectively promote sustainable crop intensification. Furthermore, this research provides a foundation for developing new and improved bylaws specifically tailored to the unique needs and challenges of the region. Implementing and enforcing effective bylaws will ultimately contribute to agriculture’s long-term sustainability and success in Southwestern Uganda. below illustrates the conceptual framework of the study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

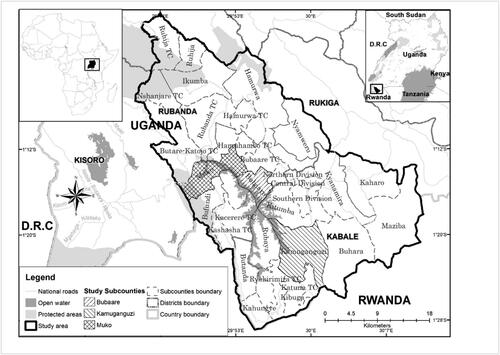

The study was conducted in Southwestern Uganda, in Kabale and Rubanda districts (). The selected study sites within the two districts were Kamuganguzi, Bubare, and Muko sub-counties. The sub-counties were selected based on the broad bylaw categories of improved and quality seed (Kamuganguzi, Kabale district), market access (Bubare, Kabale district) and soil and water conservation (Muko, Rubanda district). It is important to note that the wider Kabale district comprised the current Kabale district and Rubanda district before its fragmentation into two districts. Based on the agro-ecological zoning in Uganda, the study sites are considered to have the most significant potential for potato production, owing to their fertile soil and favourable climate, with 13,807 ha/year planted in 2020 and 1.235 production tons per ha (Kabale District Local Government, Citation2020). The sites furthermore had existing bylaws driven by the need to legislate on aspects of land degradation, high population density and declining potato production challenges (Bonabana-Wabbi et al., Citation2013; Fungo, Citation2011; UBOS, Citation2017).

3.2. Study design

This study used a cross-sectional survey employing mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to reveal the effectiveness of the different bylaws used in potato growing in South Uganda—the qualitative methods aimed to reveal the depth of how effective the bylaws were and the associated mechanisms. The qualitative methods involved the use of nine key informant interviews. Key informants include experts working with agriculture institutions like research institutions, non-governmental organisations, the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), district local government and local leaders in the community, and farmer groups. The quantitative data was collected using a structured questionnaire. The quantitative data aimed at establishing the effectiveness of bylaws (on improved and quality seeds, soil and water conservation and market access) and the associated mechanisms such as implementation level of bylaws, level of awareness about bylaws, farmers’ roles and farmers’ resources such as land, access to financial resources and formal education.

3.3. Sample size

The sample size was determined for both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. Yamane’s (Citation1967) formula for finite population led to a sample size of 112 commercial potato farmers from 156 commercial potato farmers in the three pre-selected sub-counties of Kamuganguzi, Bubare and Muko sub-counties. The response rate was 93%, leading to 22, 38, and 44 commercial potatoes selected by proportionate stratified sampling from Kamuganguzi, Bubare and Muko sub-counties. The farmers were selected from the sampling frames for each sub-county by systematic random sampling.

The data saturation method was used to determine the sample size for key informant interviews (KIIs). A sample of nine (9) key informants and six Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) met the condition of data saturation (Creswell, Citation2013).

3.4. Data collection methods

3.4.1. Key informant’s interviews and focus group discussions

First, we conducted key informant interviews. Key informants were selected based on having first-hand information about the bylaws. The respondents had experience and knowledge of existing bylaws and how they (bylaws) supported SCI in SWU. Nine (9) of KIIs (seven males and two females) were conducted. The key informants included government officials, particularly the district production office, district agricultural office, district environment and natural resources office, the sub-county chiefs and the Kachwekano Zonal Research and Development Institute (KAZARDI). In addition, key informants were also recruited from officials from private institutions. They included the Bubare Innovation Platform, the Uganda National Seed Potato Producers Association, the International Fertilizer Development Center, and the Africa 2000 Network. The principal investigator interviewed the key informants using a key informant interview guide. The interview sessions for each KI were audio recorded using a recorder and later translated (where necessary) and transcribed into edited transcripts to be analysed. Likewise, two focus group discussions were conducted in each of the sub-counties of Kamuganguzi, Bubare and Muko. Each FGD was heterogeneous, consisting of 6–10 commercial potato farmers, males and females between 25 and 65 years and about 65% were of primary, and the rest were secondary and tertiary education. The heterogeneity in terms of age, sex, and education levels. Hence, through such FGD groups, rich information was provided from different categories of people simultaneously. On average, each session took three hours to allow as many contributions as possible across each group of participants, gain clarity of issues, and allow further explanations while focusing on research objectives. In total, 63 commercial potato farmers participated in the FGDs. The FGDs were moderated by research assistants using the interview guide who knew the local languages, ‘Rukiga’ and ‘Kifumbira’, which they used to communicate during the FGD sessions. Similarly, the FGD sessions were audio recorded and later translated and transcribed, typed, and edited into transcripts, which were analysed by content thematic analysis with the help of Atlas.ti version 7.5.16 software.

The interview guides for KIIs and FGDs were designed and guided by the literature and then pretested among commercial potato farmers in the Rubaya sub-county, just south of the Kamuganguzi sub-county and subsequently revised. The KII and FGD guides had open-ended questions that captured various issues. The questions embraced: farmers’ knowledge of the various bylaws, their relevance, farmers’ participation in the implementation and monitoring of bylaws, a system for resolving conflicts that arise during the implementation of bylaws, networking among stakeholders on bylaw implementation, and factors facilitating the implementation of bylaws.

3.4.2. Designed structured questionnaire

The phase involved a designed structured questionnaire to conduct interviews with 104 randomly selected potato farmers. Mechanisms that facilitate the effectiveness of bylaws were anticipated. These included farmers’ awareness of bylaws (on seed quality, soil and water management and market access), level of implementation of bylaws (on seed quality, soil and water management and market access), land ownership, land acreage and land use/management, farmers’ roles, farmers’ access to financial resources, and framers’ education. There were three broad categories of bylaws on SCI, particularly on improved and quality seed, soil and water management and market access. There were 33 bylaws on improved and quality seeds, 15 on soil and water management, and 14 on market access. The validity of the questionnaire was established. First, the structured questionnaire included questions based on the literature and the results from the exploratory study (first phase). The questionnaire was pretested among commercial potato farmers in Rubaya subcounty and subsequently revised. Further, the Cronbach coefficient alpha (α) for the bylaws on implementation of improved and quality seeds bylaws, soil and water management and bylaws on market access were 0.89, 0.50 and 0.84, respectively. Each bylaw known by a farmer was scored 1, and each unknown was scored 0. Bylaws known or not known by farmers were scored and summed for each category. The Cronbach coefficient alpha (α) on farmers’ awareness of improved and quality seed bylaws, soil and water conservation and bylaws on market access were 0.89, 0.3 and 0.82, respectively.

Land ownership was categorised as privately owned, family-owned or owned by the community. Land acreage was the land size in acres the farmers used for crop farming. Land use or management was informed of crop farming only, both crop and livestock farming and livestock farming. Farmers’ assessed roles included: (a) being a member of the quality committee, (b) attending farmers’/group meetings, (c) implementing what farmers we trained on, (d) Deciding on penalties for those who do not adhere to the bylaws and lastly, (e) Sensitising fellow farmers. Each of the roles participated in by the farmer was scored 1 and 0 for roles s/he never participated in and summed up for overall scores for a farmer. Farmers’ level of access to financial resources, including SACCOs, earnings savings, and loans from traders. The farmer’s level of education was assessed as a resource and was rated as (a) no education, (b) primary education, (c) secondary education, and (d) tertiary education.

3.5. Data management and analysis

Mixed qualitative and quantitative approaches were used to analyse, present, and interpret data, simplify interpretation, and increase understanding of the study’s findings.

Quantitative data was entered in Epidata 3.1 and exported to Stata 13.0 for coding, cleaning and analysis. Descriptive statistics, including percentages, frequencies, mean, minimum, maximum, standard deviation, and skewness, were generated using STATA 13.0, assessing bylaw effectiveness and its mechanisms. Normality test (use of histogram and the Shapiro–Wilk test) was conducted on the dependent variable, bylaw effectiveness. Bylaw effectiveness was negatively skewed (−1.61), hence transformed by reflection and log-based 10.

Bivariate analysis using the Spearman Correlation coefficient (rho) was conducted to assess (a) the association between farmers’ awareness of bylaws and bylaw effectiveness, (b) the association between farmers’ level of implementation of bylaws and bylaw effectiveness, (c) Farmers’ roles and bylaw effectiveness, (d) Farmers’ acreage and bylaw effectiveness and level of significance for association was at 0.05. Owing to the non-distribution in the data, the Kruskal Wallis test was used to test whether land ownership, land use and farmers’ education were related to bylaw effectiveness. Independent variables with a p-value less than 0.2 at bivariate analysis, including the level of awareness of bylaws on improved and quality seeds (p = 0.17), level of awareness of bylaws on soil and water conservation (p < 0.01), level of awareness of bylaws on market access (p = 0.20), level of implementation bylaws on improved and quality seeds (p = 0.02), level of implementation bylaws on soil and water conservation (p = 0.23), level of implementation bylaws on market access (p = 0.19), and land use p < 0.017 were used for multivariate linear regression using the model below:

Where Logy is log-transformed bylaw effectiveness, β0 is the level of bylaw effectiveness when no input or mechanism was in play; β1, β2, β3, β4, and β5 are coefficients for the mechanisms, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5; x1, x2, x3, x4, x5 are mechanisms such as farmers’ awareness of bylaws on seed, farmers’ awareness of bylaws on soil and water conservation, farmers’ awareness of bylaws on market access, farmers’ implementation level of bylaws on seed, farmers’ implementation level on bylaws on soil and water conservation, farmers’ implementation level on bylaws on market access, etc.; ϵ, is the error term.

Using Atlas.ti version 7.5.16 software, nine and six transcripts for KIIs and FGDs were analysed as separate entities. Both deductive and inductive methods of thematic analysis guided data analysis from both KIIs and FGDs. Deductive analysis matched or aligned data to study objectives, whereas inductive analysis was used to derive interpretation from unexpected emerging information from the raw data or transcripts. A file name was given to each project for KII and FGD manuscripts. Each transcript was repeatedly read, and codes were developed by open coding to capture emerging patterns. Open coding allows for capturing new theoretical possibilities as one interacts with qualitative data (Costa et al., Citation2016). Codes were refined, and categories formed from them, forming sub-themes and themes. Quotations were also noted to substantiate some codes. The same procedure was used to analyse transcripts from FGDs. Qualitative and quantitative findings were triangulated.

There were two themes (the level of bylaw implementation and mechanisms for bylaw effectiveness in influencing bylaw effectiveness). Eight categories: five (5) mechanisms for bylaw effectiveness coded as MCHNSM and three (3) categories for the level of bylaw implementation coded as IMPL were developed. Several mechanisms included bylaw awareness, farmer roles, resources, land use and education level. The category bylaw awareness was coded as AWR with the sub-category’s awareness of bylaws on seed quality and improvement, awareness of bylaws on soil and water conservation, and awareness of bylaws on market access coded as AWR _SQI, AWR_SWC, and AWR_MA respectively.

The categories under mechanisms, namely farmers’ resources and land use, were coded as RESOURCE and LND, respectively. Farmers’ roles had sub-categories being a member of the quality committee, attending farmers’ or group meetings, deciding on penalties and sensitising fellow farmers, who were coded as MMBR_QC, ATTND-MEET, and PENALTY, respectively. The sub-categories under farmer’s resources included help such as training, seeds, and certification for seed from institutions coded as INSTITN. Loans sought from savings and credit cooperative organisations (SACCO), finances from savings and loans from traders or payments in advance were coded as LOANS, respectively. Under the theme of bylaw implementation, there were categories such as level of implementation for bylaws on seed improvement and quality (coded as IMPL-IQS), level of implementation for bylaws on soil and water conservation (coded as IMPL-SWC), and level of implementation for bylaws on market access (coded as IMPL-MA). Category level of implementation for bylaws on seed improvement and quality had subcategories such as inspecting for seed suppliers coded as INSPECT; seeds should have germinated (coded as GERMINATE) OR harvesting (coded as HARVEST). Under the implementation of bylaws on soil and water conservation, there are codes such as TRENCH, CONTOUR, and TERRACE for digging trenches, contours and terraces, respectively. Giving penalties to those who graze in others’ pieces of land coded as PENALTY. The level of implementation for bylaws on market access had codes such as BULK, BAGS, SORT, RECORD, and STEAL for selling in bulk, use of standard bags, sorting, record keeping, and not stealing, respectively.

The research was registered, peer-reviewed, and approved by the National Research and Ethics Committee at the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). Individual consent was secured from participants before the administration of study tools. The study used pseudo-names in place of actual respondents’ names by arranging the respondents according to the scheduled time for the interviews and discussions, for example, KI1, KI2, KI3… and FGD1, FGD2, FGD3…and for structured questionnaires (Q1, Q2, Q3…). This helped ensure the respondents’ anonymity, and they felt comfortable answering and responding to the research questions, interviews and discussion topics. The researcher ensured the data was securely kept and password protected to prevent unauthorised access.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ demographic information

below summarises the attributes of the individual potato farmers interviewed, including the age, sex, district, sub-county, civil status, the highest level of education, religion, land management, the main crops grown and land ownership.

Table 1. Overall Characteristics of Study Participants.

4.2. Farmers’ awareness of bylaws on sustainable crop intensification

Farmers’ awareness of bylaws on SCI is presented in . reveals farmers’ awareness of bylaws focusing on quality and improved seed potato use. From , farmers had very high awareness of bylaws focusing on the use of quality seeds for potato growing, with most of them, between 97.1% and 76.0%, being able to cite at least a bylaw, out of any seventeen bylaws on use of quality seeds. The bylaws that farmers were most aware of included Spraying with pesticides (99.0%), Not growing potatoes on the same piece of the land season after season/doing crop rotation (98.1%), cutting off the shoots to allowing the potato to mature (97.1%); putting potatoes on stalls or grass so that they dry well (97.1%), preparing land well and leaving it to rest before planting potato (97.1%); ensuring that seeds are germinated well (97.1%) and not harvesting potato once it rains (96.2%). However, farmers were least aware of spraying pesticides when in gumboots (1.0%), Fanya chini (lower contours),1.0% and using standard measures for selling (1.0%).

Table 2. Farmers’ awareness of bylaws focusing on improved and quality seed, N = 104.

Table 3. Farmers’ awareness of bylaws focusing on soil and water conservation, N = 104.

Table 4. Farmers’ awareness of bylaws focusing on market access, N = 104.

A high level of awareness about bylaws was said to match the implementation level, which was appreciated in the Bubare sub-county. One of the KIIs in the Bubare sub-county mentioned that every household had at least one member knowledgeable on bylaws on maintaining water, water collection points or soil conservation.

In each home, at least they know how to maintain water, have water collection point…. increased harvest and income, know how to protect our soil from increasing income. KI4, Bubare Innovation Platform)

Nevertheless, farmers needed to gain awareness of some aspects, failing to implement or adhere to them. Farmers who are ignorant or negligent about bylaws hardly implement them. For instance, farmers were unaware that over-recycling seed potatoes did affect the quality of the yields. Once farmers bought seed potatoes from certified sources in one season, they kept recycling the same seeds for the succeeding seasons, and they did not go back to buy fresh seed potatoes. However, the more the farmers recycled the original seed, the less yield they got and the more susceptible they became to diseases and pests. However, the practice of recycling the seed was attributed to the high costs of the seeds from accredited suppliers—farmers, therefore, preferred recycling seeds to buying expensive fresh-seed potatoes.

shows farmers’ awareness of bylaws on soil and water management. Of the fifteen bylaws focusing on water conservation, six (6) were widely perceived by farmers, including digging trenches (100%), digging contours (100%), planting potatoes in lines (100%), digging water channels to control floods in valleys (99.0%); bylaws to stop animal keepers from spoiling people’s gardens (98.1%), and not planting eucalyptus trees in fields where potatoes are grown (93.3%). On the other hand, farmers were least aware of crop rotation (1.0%), Planting elephant grass (1.0%), using Fanya chini and Fanya Juu (1.9%), and terracing (2.9%) (see ).

According to the FGDs from Muko, Bubare and Kamuganguzi, most farmers indicated they knew the existing bylaws. From the survey, 98% of the respondents said they know bylaws on soil and water conservation, market access and improved and quality seed. A high level of awareness about bylaws was said to match the implementation level, which was appreciated in Bubare Sub-county. One of the KIIs in Bubare Subcounty mentioned that every household had at least one member knowledgeable on bylaws on water conservation, water collection points or soil conservation.

In each home, at least know how to maintain water, have a water collection point…. increase harvest and income, and protect our soil from increasing income. (KI4, Bubare Innovation Platform, Bubare)

lists farmers’ awareness of bylaws concerning market access. Farmers were mainly aware of bylaws that ensured high quality of potatoes and economical packings, such as ensuring that only mature potatoes should be sold (99.0%), ensuring good quality for potatoes, especially those used in making crisps (99.0%) and careful choice of proper bags for packing of potatoes (99.0%). Possession of trading licenses by potato traders was the least known bylaw (1.9%).

below summarises descriptive statistics on the scored categories of bylaws. Farmers were generally aware of the bylaws (mean = 36.17, sd = 3.188; skw = −1.726), farmers were most aware of the bylaws on access market bylaws (mean = 12.15, sd = 1.447; skw = −2.766), followed by improved and quality seed potatoes.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics on bylaw awareness among farmers, N = 104.

The results of the relationship between farmers’ awareness and bylaw effectiveness are presented in . Farmers’ awareness of soil and water conservation bylaws was significantly associated with bylaw effectiveness (rho = −0.267; p < 0.01). This was not the case with all the other variables.

Table 6. Spearman correlation coefficients (rho) between farmers’ awareness and bylaw effectiveness, N = 104.

Furthermore, it was observed that limited awareness of the formal bylaws limited participation and outcomes from extension services. Thus, creating awareness and resource mobilisation were critical considerations in strengthening monitoring and enabling responsive behaviour of potato crop farmers towards SCI. As such, this undermined the prospects of realising SCI in the region. One of the KII, from District Local Government, noted:

…then another issue is about the implementation of the bylaws. Some people fail to take them seriously because they lack proper sensitisation. We first considered sensitising these people on how bylaws can work within their communities.

4.3. Implementation of the existing bylaws

Bylaws that ensure seed potatoes are harvested matured enough were the most implemented, mainly harvesting only mature potatoes (100%) and that shoots are cut off (100%), see . Some bylaws on improved and quality seed, though farmers were aware of them, were not implemented, particularly those regarding the planting and subsequently recommended farming practices such as getting an inspection from MAAIF for the case of seed producers, doing mulching, ensuring weeding, the standard way of spacing potatoes and avoiding to spray and weeding when it is raining. shows how the different bylaws on improved and quality seed potatoes were implemented.

Table 7. Farmers’ implementation of bylaws focusing on improved and quality seed, N = 104.

Findings from qualitative data, especially from the key informants (6/9), indicated that the level of implementation, especially regarding bylaws or ordinances that promote soil and water conservation, had regressed or declined. The KIIs pointed out that during the 1970s and 1980s, the government structures, particularly at the village level, ‘maka kumi’, meaning village administration covering ten homes; the parish administration ‘Muruka’, and the bounty chiefs were so strict about the implementation of soil and water conservation bylaws. The government then ensured that farmers constructed terraces, contours, trenches, and channels, dug ditches and planted trees like bamboo to control running water and soil erosion. Those who breached the bylaws in the 1970s and 1980s were sentenced to serve community service, fined money or imprisoned. It was pointed out that the current local government was lenient to farmers and compromised for political gains, and hence, some farmers did not mind building terraces and contours or taking actions to protect the soils. One of the KII had to say this:

Implementation of the bylaws in the 80s and 70s was very effective. The role of implementation was with the technical people and not the politicians. During that time, there was a structure of batongole, muruka chiefs who were the parish chiefs, and the batongole were sub-parish chiefs. They would not cover only one village but the whole parish. Moreover, we also had the parish chiefs who were the frontline implementers of the bylaws. (KII, from a private institution)

During those days, the quality and history of the seed were not considered anywhere because farmers were not aware of such things; they only knew about beans or maize. Before 1995, there was no farmer-based seed multiplication. (KII, from District Local Government)

Some farmers are in the Uganda National Seed Potato Producers Association (UNSPPA). I think you have met the organisation responsible for producing potato tubers; they arranged with KAZARDI to inspect their gardens so that their seed is clean. (KII, from a private institution)

Table 8. Farmers’ adoption of bylaws focusing on soil and water conservation, N = 104.

From both FGDs and KIIs in all sub-counties and at the district local governments, it was reported that a majority of farmers appreciated the value of implementing soil and water conservation bylaws and consequently constructed contours and trenches to control soil erosion and ensure water conservation in their gardens. One of the KIIs representing a private association for farmers had to say this:

Like the construction of terraces of terraces, no one has to first tell us; we saw that our soils were getting eroded, and now everyone knows they must construct terraces to conserve their soils. (KII, from a private institution)

We encourage people to use sustainable land management SLM practices and try to fight those practices that impact negatively on the soils, reducing the productivity of the crops but potato in particular. Some promote technology like trenches ‘fanya chini’ and contours ‘fanya juu’. (KII, from District Local Government)

Table 9. Farmers’ adoption of bylaws focusing on market access, N = 104.

Like quantitative data, as indicated in , qualitative data all echoed the implementation of bylaws agreed to market access. Across all four (4) FGDs and among four KIIs, it was reported that it was unlawful to graze animals like cattle, sheep or goats in another one’s farmland, and such an act was penalised. One of the key informants had this to say:

But of late, once the animals are gotten in the garden, the goat’s owner is supposed to compensate physically by giving a goat if he does not have the money, or the garden owner calculates what has been destroyed, and the other person pays. So that has worked in some areas. (KII, from a private institution)

And then in terms of marketing, one of the key issues here was people just selling in bags, not minding about the kilograms or what and not choosing a particular size. So, we have tried to promote standard measures to ease pricing. (KII, from District Local Government)

Findings from FGDs and KIIs further showed there were bylaws that penalised thieves caught stealing potatoes. Any thief caught stealing potatoes could be charged as much as 500,000 UGX. Other than bylaws covering sub-counties or districts, farmers’ groups formulated and instituted regulations in smaller jurisdictions like parishes, villages or groups.

If one steals, they bring him to the sub-county. However, there is one group called the Ngozi group they have their bylaws; they fine that whoever is caught in another person’s garden stealing pays a fine of UGX500,000 ($132), and also, the one who has bought this stolen potato pays a fine of UGX500,000 ($132). For example, I may have a son who steals my potato and sells it to you, yet you know that my son has no garden, so you are also fined for knowingly stealing the stolen potato. (KII, from a private institution)

summarises scores on the implementation of bylaws. Upon summing scores for the adoption of the different categories of bylaws. Of the 33 bylaws focusing on seed quality, only 20 were implemented with a maximum of 20 scores. On average, farmers adopted 17, 5, 9 and 31 bylaws for seed quality, soil and water management, market access, and overall. There was a wider dispersion or variation in adopting bylaws altogether (sd = 4.89). Farmers somewhat uniformly adopted soil and water management bylaws (sd = 0.93).

Table 10. Summary of scores on the adoption of bylaws on improved and quality seed, soil and water conservation, and market access, N = 104.

Pearson Correlation was carried out to establish the relationship between bylaws implementation and bylaw effectiveness, and the results are in . Farmers’ implementation level of improved and quality seed (rho = −0.209; p < 0.05); overall implementation level of all seed, soil and water conservation and market access bylaws (rho = −0.198; p < 0.01).

Table 11. Spearman correlation coefficients (rho) between bylaw effectiveness and bylaws implementation mechanisms, N = 104.

4.4. Farmers’ roles

describes the roles of farmers in the implementation of bylaws. Most farmers were involved in either attending farmers’ meetings (88.5%) or implementing what they trained in (88.5%). Farmers’ roles were scored and summed up, and it is indicated that farmers, on average, were involved in three roles (mean =2.94), with sd = 0.923, skewness of −0.43 and four (4) being the maximum of roles a farmer could get involved. Pearson correlation test indicated that farmers’ roles were significantly associated with bylaw effectiveness by an inverse version (rho = −0.531, p < 0.01).

Table 12. Farmers’ roles in the implementation of bylaws, N = 104.

Farmers’ deep involvement and ownership of activities concerning the formulation and implementation of the bylaws in Bubare explain the ultimate success of implementing the bylaws. Farmers in Bubare were involved straight away in the formulation of bylaws. They are involved in attending meetings related to farming activities, and they are in charge of running demonstration gardens.

Of course, they were called in the formulation, and they are the ones who formulated them, and they are the ones who are implementing them. So, they are called into meetings and attend meetings. (KI4, Bubare Innovation Platform)

4.5. Farmers’ resources in the implementation of bylaws for SCI

Farmers mainly used available indigenous resources. From , the majority of the farmers had family ownership of land (71.2%), practised only crop farming (63.5%), used funds from saving their earnings (84.6%) and were of primary education (63.5%). An estimated acreage of land used by farmers was made. Results indicate that farmers had a shortage in the land they used for farming; average acreage = 2.91 acres, min = 0.88, max = 14.50, sd = 2.36 and with a right (positive skewness), 2.90. Land acreage as used by farmers was significantly related to bylaw effectiveness (rho = −0.282; p = 0.029). Access to each of the different sources of finances by a farmer was scored and summed to obtain the level of access to financial resources and was not related to bylaw effectiveness (rho = −0.031; p = 0.34).

Table 13. Percentages and frequencies of farmers’ resources for bylaw implementation.

Farmers’ implementation level of improved and quality seed (rho = −0.209; p < 0.05); overall implementation level of all seed, SW and market access bylaws (rho = −0.198; p < 0.01); farmers’ overall knowledge of soil and water management (rho = −0.267; p < 0.01); farmers’ roles (rho = −0.531; p < 0.001); and farmers’ total acreage for main crops (rho = −0.282; p < 0.05) was negatively and significantly related to bylaw effectiveness.

Kruskal-Wallis Test was conducted to examine the differences in bylaw effectiveness according to land use, level of education and land owner. There were significant differences in bylaw effectiveness by land use and education levels. Land use differed on bylaw effectiveness in the three categories, that is, crop farming, both crop and livestock farming and livestock farming only (Chi-square = 8.141, p = 0.017, df = 3), not in the table. Likewise, bylaw effectiveness differed on the four education levels: no education, primary, secondary, and tertiary education (Chi-square = 8.141, p = 0.017, df = 3). On the contrary, there were no significant differences in bylaw effectiveness by land ownership, that is, private ownership, family ownership and community ownership (Chi-square = 0.948, p = 0.622, df = 2).

We have close collaboration with ISSD Uganda on the seed as the seed is an issue, and they are experts in seed production and quality assurance. We also collaborate with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) on the Policy Action for Sustainable Intensification of Ugandan Cropping Systems (PASIC) project, and we have been collaborating on the bylaws. However, at the same time, under the Resilient Efficient Agribusiness Chains in Uganda (REACH-Uganda) project, we are collaborating on climate-smart agriculture-related activities. IITA mostly does research, and we have identified climate smart interventions which we shall collaborate on. (KII, from a private institution)

Multivariate linear regression was conducted to assess the mechanisms responsible for bylaw effectiveness, and indicates the results of the most suitable model. The level of implementation of seed bylaws, farmers’ roles and land use were significantly associated with bylaw effectiveness. For every additional seed bylaw implemented, the effectiveness of bylaws decreases by 1.3%, that is, (Exp (β) −1) *100, and (β = −0.013, p = 0.04; CI: −0.026; −0.000). Similarly, for every one additional role played by a farmer, the effectiveness of bylaws decreases by 12%, that is, (Exp (β) −1) *100, and (β = −0.127, p < 0.001; CI: −0.171; −0.084). On the other hand, the level of bylaw effectiveness was 12.1% lower among farmers who practised both crop and livestock farming than among farmers who practised only crop farming (β = −0.013, p = 0.04; CI: −0.026; −0.000). The above model explains 43.1% of the variations in the bylaw’s effective implementation.

Table 14. The coefficients of multivariate regression for bylaw effectiveness, bylaw implementation and mechanisms.

5. Discussions

5.1. Farmer awareness of existing bylaws on sustainable crop intensification

The study shows very high farmers’ awareness of bylaws on SCI in aspects of quality and improved potato seeds, chemical spray, conservation of land, conserving seed, crop diversification and rotation, fallowing, and harvesting during the dry season. The results are relevant because they show a high level of awareness of conservation practices that improve seed and potato quality and conservation of soil, which are critical bylaw-enhanced farming practices for SCI. This awareness is gained through the strategic grouping of farmers in formal or non-formal arrangements. They can be accessed by developing partnerships to develop their knowledge capacity of best practices in potato production and supporting bylaws for intensification of potato crop production. Helmke and Levitsky (Citation2004) and North (Citation1990) support the effectiveness of bylaws formed within informal groups or formal institutions. This group-based approach is not only resource-saving in developing group capacity to implement bylaws on SCI but also an effective way of pooling resources to and monitoring their sustainable use as provided by the bylaws. The importance of creating awareness in improving crop yields is revealed in the study by Nkonya et al. (Citation2005). This potentially leads to the development of farming practices relevant to SCI. The effectiveness of bylaws in shaping behaviours that support SCI also features in various theoretical and scholarly works (for example, Helmke and Levitsky, Citation2004; Nkonya et al., Citation2008; North, Citation1990).

The results reveal that harvesting mature crops and using high-quality and improved seeds were the most implemented bylaws to support SCI. Using a planting and harvesting order in crop farming, the study observes that ensuring quality and improved seeds are planted and harvesting mature crops are the most important phases in the morning production and supply processes, which, if mishandled, lead to crop failure in a season. Hence, maximum care is taken to ensure that existing bylaws on these important farming activities of the season are outrightly implemented to support SCI. It is therefore not surprising that the two bylaws related to planting high quality and improved seeds and harvesting of mature crops are not only pre-existing and traditional but also carry very strong behaviour responses of farmers to ensure their implementation to prevent crop failure. This result gives an insight into how behaviour evolves, from when farmers’ groups struggle to accommodate and adopt bylaws through intense monitoring and implementation of a reward system to a point when it is natural for them to follow as a matter of life and death (food security). This is consistent with North’s (Citation1990) institutionalism theory, which shows how groups evolve, setting rules, norming, and networking dynamics -all to ensure the adoption of a rule or principle-based approach to managing scarce resources and promoting sustainable use of natural resources to intensify crop production, where at a community level, bylaws apply. In this case, the institutionalisation and communalization of SCI are centred on rules and bylaws of an informal and formal nature or vice versa.

Furthermore, farmers were most aware of the bylaws on access to the market, followed by improved and quality seed. They understood that compliance with market access bylaws was crucial for selling their produce and maximising profits. Additionally, farmers recognised the importance of using improved and quality seeds to enhance their crop yields and produce high-quality goods. By prioritising these two aspects, farmers ensured they could consistently meet market demands and maintain a competitive edge in the industry, ensuring increased implementation of SCI bylaws. As such, governments and policymakers must comprehensively understand the factors that either facilitate or impede farmers’ engagement in markets (Razzaq et al., Citation2022).

Farmers’ awareness of bylaws on soil and water conservation was significantly associated with bylaw effectiveness. In framers applying good agronomic practices, they impliedly implemented the bylaws on soil and water conservation. This suggests that farmers knowledgeable about the bylaws were likelier to follow them and adopt effective conservation practices. Farmers indirectly demonstrated compliance with the bylaws by implementing good agronomic practices, leading to better soil and water conservation outcomes. Therefore, promoting awareness and understanding of these bylaws among farmers is crucial for enhancing their effectiveness and fostering sustainable agricultural practices.

Moreover, limited awareness of the formal bylaws limited participation and outcomes from extension services (Klerkx & Jansen, Citation2010; Nkonya et al., Citation2008). Thus, creating awareness and resource mobilisation were critical considerations in strengthening monitoring and enabling responsive behaviour of potato crop farmers towards SCI. As such, this undermined the prospects of realising SCI in the region.

For example, farmers who lack knowledge or fail to adhere to bylaws often need help to implement them effectively. In the context of SCI, it is noteworthy that farmers were found to possess limited knowledge regarding the potential impact of excessive recycling of seed potatoes on the overall quality of their crop yields. In the agricultural context, it was observed that farmers would initially procure seed potatoes from certified sources for a particular season. Subsequently, these farmers would engage in a practice of reusing the same seeds for subsequent seasons without resorting to the purchase of fresh seed potatoes. As the farmers continued to recycle the initial seed, they observed a gradual decline in their overall crop yield. Additionally, they noticed an increased vulnerability to various diseases and pests within their agricultural systems (Aheisibwe et al., Citation2016; Makuma-Massa et al., Citation2020; Walukano, Citation2016).

5.2. Implementation of the existing bylaws

Most enforcement of bylaws required harvesting only fully matured improved seed potatoes. The high prevalence of this can be attributed to the fact that potato maturity guarantees both quality and profit for the farmer. The most common soil and water conservation bylaws required farmers to dig trenches and plant potatoes in rows, providing further evidence that farmers complied with bylaws mainly due to the benefits they offered. These bylaws aimed to prevent erosion, maintain soil fertility and ensure efficient water usage. Farmers understood the importance of following these regulations to protect their crops and enhance their yields. By adhering to the guidelines, farmers could maximise their profits while contributing to sustainable agriculture practices.

The more seed, soil and water conservation, and market access bylaws are in place, the less effective they will likely be. This means that the greater the number of bylaws available for implementation, the less effective the implementation will be. As a result, there is a need to consolidate, compound or make the bylaws less precise and document bylaws so that farmers can easily implement them. By consolidating the various bylaws into a more comprehensive framework, farmers will have a clearer understanding of the regulations and requirements they need to adhere to. This will make it easier for them to implement the necessary seed, soil, and water conservation practices. Additionally, documenting these bylaws will provide farmers with a valuable resource they can refer to for guidance, ensuring that they consistently follow the regulations and maximise their effectiveness.

5.3. Farmers’ roles

The results describe farmers’ roles as either participating in meetings and workshops that create awareness of best practices and associated bylaws that support SCI or implementing lessons learned to achieve SCI. This means that farmers are the first learners who cultivate an understanding and knowledge of bylaws for promoting SCI before they co-opt lessons learned into practices for SCI. However, it is also possible to find that not all farmers who gain knowledge of bylaws practice them or develop practices for SCI, although according to Nkonya et al. (Citation2005), they mostly go on to implement them. Both aspects are critical (e.g. creating awareness or knowledge of bylaws and implementing the trainee knowledge to achieve tangible outcomes (SCI). What is exciting about this is the time differences in implementation, yet they (farmers) go on to implement the bylaws to support SCI. Through evaluations and learning, farmers can improve their understanding of bylaws and the relevance of implementing them as a motivation to subsequently implement them to achieve SCI. Hence, creating awareness is a continuous process that helps to drive the implementation of lessons learned about bylaws to organically promote SCI at the farmers’ group level and community level, where influences of group norms, community bylaws and expectations reinforce individual-level practices. The individual farmers have no choice but to follow and act accordingly to support SCI.

Farmer roles and land management practices were the most important in ensuring bylaw effectiveness; most importantly, crop and livestock management was effective in land management. Farmers’ roles have a direct impact on the effectiveness of bylaw enforcement. As farmers took on additional roles, their effectiveness in bylaw implementation decreased. Farmers diversify their businesses as an adaptation and risk management strategy; according to our evidence, this reduces effectiveness. The message is that farmers should treat potato farming as a business rather than subsistence if they want to maximise their yield. Furthermore, farmers should join farmer groups to delegate some of these roles to the group staff. However, it has been suggested that many general rural development organisations should ideally concentrate on a single function. To address the need for coordination and integration, such groups and organisations must have genuine decision-making authority, represent a local constituency, answer downwards and cannot be held accountable for everything (Fisher, Citation2004).

Most farmers were involved in either attending farmers’ meetings or putting what they had learned into practice. This emphasises the significance of capacity building through training in enhancing SCI. By actively participating in farmers’ meetings and applying the knowledge gained from training, farmers can enhance their scientific and technological capabilities. This improves their understanding of modern farming practices and enables them to adopt efficient and sustainable methods. Ultimately, capacity building plays a crucial role in driving the success and advancement of the agricultural sector. As such, more focus should be placed on network (farmer group) governance and social and societal learning processes to address the substantial knowledge gaps that threaten the effectiveness of bylaws implementation (Pahl-Wostl et al., Citation2007; Ostrom, Citation2001).

5.4. Farmers’ resources

The study shows that farmers’ resources were customarily acquired or raised through group savings and activities. Access to land provides opportunities for economic emancipation and sustainable livelihoods for rural farmers. Still, as the population explodes over time, its availability and viability are compromised, as Fungo (Citation2011) noted. These farmers, who acquire land through inheritance, are most favoured and easily apply bylaws to manage and utilise it effectively to achieve SCI. Other means, such as working in groups, help raise financial resources to acquire farmland through renting or acquisition as individuals and groups. So, while potato farming is managed through farmer’s groups, individual farmers are free to operate alone at their convenience or both alone and in groups simultaneously without any limitation. However, the formation and application of bylaws originate at the group level to influence the actions of individual members, even when they choose to operate alone in acquiring land or its utilisation so that SCI is not compromised. North’s (Citation1990) institutionalism theory alludes to this when it indicates that bylaws apply to group context rather than individual. This could be due to the ease of monitoring group members or networks of groups to manage and influence group and individual farmers’ behaviour. This shows that group-level positions or bylaws still influence individual farmers’ decisions and behaviours.

Furthermore, the effective implementation of bylaws requires resources. Potato farmers require resources to improve capacity, obtain high-quality seed potatoes, and transport their crops (Walukano, Citation2016). Local governments, NARO, and NGOs enforcing bylaws on SCI interventions are under-resourced. Increasing budget allocations would be critical to the process. There needs to be more financing, and the interference of politicians has been among the obstacles impeding the effective implementation of bylaws (Ampaire et al., Citation2015; Rwakakamba, Citation2009; Yami & Van Asten, Citation2017). The lack of financial support and the interference of politicians have hindered the effective implementation of bylaws on SCI interventions. This has resulted in limited resource access for potato farmers, making improving their capacity and obtaining high-quality seed potatoes difficult. Local governments, NARO, and NGOs responsible for enforcing these bylaws are already under-resourced, and increasing budget allocations would be crucial in overcoming these obstacles and ensuring the successful implementation of bylaws. These obstacles hinder the ability to enforce regulations and achieve desired outcomes.

Politicians have occasionally ignored violations of bylaws and, in some cases, encouraged environmentally harmful practices for personal gain (Sophie, 2007). For potato farming communities, access to adequate cropland presents a barrier to increasing production (Juana et al., Citation2013). Without access to sufficient land, potato farmers are unable to expand their operations and meet the growing demand for their crops. This lack of land can restrict their ability to implement environmentally friendly practices and may force them to resort to harmful practices to maximise their yields. This further reinforces the need for responsible governance and regulatory measures to prevent politicians from prioritising personal gain over the well-being of the environment and communities they serve.

5.5. Bylaw effectiveness against bylaw implementation mechanism

Land use differed on bylaw effectiveness. Farmers who practised crop farming alone tended to achieve bylaw effectiveness more than those who practised crop and livestock farming. This implies the need for farmers to use the few available resources to specialise in a particular agricultural activity (potato farming) to achieve bylaw effectiveness in potato SCI. Diversifying crop farming with livestock farming did not accrue any advantage regarding bylaw effectiveness for potato SCI. Specialisation and mastering the trade in potato production for seed potato and potato ware is advised for farmers rather than spreading thinly on multiple enterprises. The premise that poverty causes less intensive land management, which in turn causes poorer production and revenue, is supported by Pender et al. (Citation2004). According to Pender et al. (Citation2004), poverty often leads to less intensive land management practices, resulting in reduced agricultural productivity and lower revenue. Therefore, to improve bylaw effectiveness in potato SCI, farmers are advised to specialise in potato farming and master the trade in seed potato and potato ware production. This focused approach allows farmers to maximise their expertise and resources, potentially increasing productivity and revenue. Diversifying into livestock farming did not provide significant advantages regarding bylaw effectiveness for potato SCI.

Bylaws’ effectiveness at regulating land management practices did not vary based on land ownership, implying that regulations are equally crucial for all landowners. The cultivation of social responsibility emerges as a shared challenge and objective among all actors, playing a pivotal role in sustainable resource management by implementing formal and informal bylaws tailored to varying circumstances. The aforementioned viewpoint aligns with the findings of Sanginga et al. (Citation2010) and Nkonya et al. (Citation2008), who advocated for the establishment of appropriate regulatory frameworks to bolster endeavours aimed at enhancing agricultural practices essential for the attainment of Sustainable Crop Intensification (SCI).

6. Conclusion

The study shows that all the important mechanisms, as locally experienced and conceptualised as tools for implementing bylaws to support SCI, ranged between strong and very strong, which can only be harnessed to promote SCI on a long-term basis in SWE. They include farmers’ awareness of bylaws on planting quality and improved seeds, soil conservation, crop rotation, and fallowing; implementing of existing bylaws focused mainly on bylaws on planting quality and improved seeds and harvesting mature crop yields; farmers’ roles in implementing bylaws on SCI centred on participation in meetings and workshop events and implementation of lessons learned to effectively implement bylaws on SCI; greatest resources for farmers to implement bylaws on SCI were access to customary land and pooling of financial resources through farmers’ groups (including knowledge resource).

We recommend that authorities balance introducing new bylaws and ensuring thorough compliance and enforcement of existing ones. Build networks of the various actors in the potato value chain to harmonise bylaws to enhance their effective implementation. By doing so, stakeholders such as potato farmers, traders, and processors can come together to develop standardised rules and regulations that govern the production, trade, and processing of potatoes. This will ensure a consistent, streamlined approach throughout the value chain, improving efficiency and reducing conflicts. Additionally, it will promote cooperation and collaboration among the actors, leading to better communication, knowledge sharing, and overall success in the potato industry. Finally, farmers should be encouraged to specialise in potato seed and ware (food) production. Specialising in seed and ware potato production can have several benefits for farmers. Firstly, it allows them to focus their resources and expertise on a specific niche, maximising their yields and quality. This specialisation also creates opportunities for collaboration and knowledge-sharing within the industry, leading to advancements in breeding techniques and disease resistance. Additionally, farmers can tap into the growing demand for high-quality potatoes for consumption and for producing processed potato products such as chips and fries by focusing on seed and ware potato production.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul Kibwika

Paul Kibwika is associate professor at Makerere University with research interests in agricultural knowledge systems, innovations management and social transformations; and adaptive management and sustainability. He is also a trainer and facilitator of institutional change, strategic planning and social skills enhancement.

Paul Nampala

Paul Nampala is currently working as an independent consultant with Geotropic Consults and Scholarly Works Associates. For over eight years, he was the Programe Manager for Research & Innovations as Grants Manager engaged with the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) in managing grants with a research portfolio. He is an associate professor at Department of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Bugema University. He also serves as a scientific editor for: The African Crop Science Journal; the African Journal of Rural Development; and the East African Journal of Science, Technology, & Innovation.

Mastewal Yami

Mastewal Yami is currently an independent consultant based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Formerly, she served as a policy scientist at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). Her research interest is in the interplay of policies, institutions (formal and informal), gender issues in farming systems, and the governance of land and water resources.

References

- Agrawal, A. (2008). The role of local institutions in adaptation to climate change. The World Bank.

- Aheisibwe, A. R., Barekye, A., Namugga, P., & Byarugaba, A. A. (2016). Challenges and opportunities for quality seed potato availability and production in Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 16(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.4314/ujas.v16i2.1

- Ampaire, E., Happy, P., Van Asten, P., & Radeny, M. (2015). The role of policy in facilitating the adoption of climate-smart agriculture in Uganda. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- Bonabana-Wabbi, J., Mugonola, B., Ajibo, S., Kato, E., Kalibwani, R., Kasenge, V., Nyamwaro, S., Tumwesigye, S., Chiuri, W., Mugabo, J., Fungo, B., & Tenywa, M. (2013). Agriculture profitability and technical efficiency: The case of pineapple and potato in SW Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 8(3), 145–149. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/51423

- Bond, C., & Heimlich, J. (2014). Written documents for community groups: Bylaws. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/CDFS-1570.

- Carey, J. M. (2000). Parchment, equilibria, and institutions. Comparative Political Studies, 33(6–7), 735–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041400003300603

- Costa, C., Breda, Z., Pinho, I., Bakas, F., & Durão, M. (2016). Performing a thematic analysis: An exploratory study about managers’ perceptions on gender equality. The Qualitative Report, 21(13), 34–47. Retrieved from htp://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss13/4 https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2609

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Doughty, C. E. (2013). Preindustrial human impacts on global and regional environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 38(1), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-032012-095147

- FAO. (2017). The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges. Rome.

- Fisher, R. J. (2004). What makes local organisations and institutions effective in natural resource management and rural development? In M. C. Wijayaratna (Ed.), Report of the APO seminar on role of local communities and institutions in integrated rural development held in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 15-20 June 2002 (ICD-SE-3-01) (pp. 85–90).

- Foresight. (2011). The future of food and farming. Government Office for Science.

- Friedrich, T., & Kassam, A. (2016). Food security as a function of sustainable intensification of crop production. AIMS Agriculture and Food, 1(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.3934/agrfood.2016.2.227

- Fungo, B. (2011). Use of soil conservation practices in the Southwestern Highlands of Uganda. Journal of Soil Science and Environmental Management, 3(9), 250–259. http://www.academicjournals.org/JSSEM

- Godfray, H. C. J. (2015). The debate over sustainable intensification. Food Security, 7(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0424-2

- Godfray, H. C. J., &Garnett, T. (2014). Food security and sustainable intensification. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 369(1639).

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2004). Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics, 2(04), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472

- Hendry, A. P., Gotanda, K. M., & Svensson, E. I. (2017). Human influences on evolution and the ecological and societal consequences. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1712), 20160028. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0028

- Hove, G., Rathaha, T., & Mugiya, P. (2020). The impact of human activities on the environment. Case of Mhondongori in Zvishavane, Zimbabwe. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 08(10), 330–349. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2020.810021

- International Fertilizer Development Center. (2020). Markets are changing in potato and rice in Uganda. Resilient Efficient Agribusiness Chains (REACH) - Uganda Annual Report. https://ifdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Markets-are-Changing-in-Potato-and-Rice-in-Uganda-Web-.pdf

- Juana, J. S., Kahaka, Z., & Okurut, F. N. (2013). Farmers’ perceptions and adaptations to climate change in Sub-Sahara Africa: A synthesis of empirical studies and implications for public policy in African agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Science, 5(4), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v5n4p121

- Kabale District Local Government. (2020). District development plan 2015-20. Ministry of Local Government.

- Kapari, M., Hlophe-Ginindza, S., Nhamo, L., & Mpandeli, S. (2023). Contribution of smallholder farmers to food security and opportunities for resilient farming systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7, 1149854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1149854

- Klerkx, L., & Jansen, J. (2010). Building knowledge systems for sustainable agriculture: Supporting private advisors to adequately address sustainable farm management in regular service contacts. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 8(3), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2009.0457

- Koffi, A., & Kalinganire, A. (2016). Bylaws as complementary means of tenure security and management of resource conflicts: Synthesis of various West African experiences. Forests Trees and Livelihoods, 25(2), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2016.1158667

- Lampkin, N., Pearce, B., Leake, A., Creissen, H., Gerrard, C., Lloyd, S., Padel, S., Smith, J., Smith, L., Vieweger, A., & Wolf, M. (2015). The role of agroecology in sustainable intensification. A report for the land use policy group. Organic Research Centre and Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- Makuma-Massa, H.,Kibwika, P.,Nampala, P.,Manyong, V., &Yami, M. (2020). Factors influencing implementation of bylaws on sustainable crop intensification: Evidence from potatoes in southwestern Uganda. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1841421. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1841421

- Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(3), 1–19. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100387

- Mowo, J., Masuki, K., Lyamchai, C., Tanui, J., Adimassu, Z., & Kamugisha, R. (2016). By-laws formulation and enforcement in natural resource management: lessons from the highlands of eastern Africa. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 25(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2016.1159998

- Nedessa, B., Ali, J., & Nyborg, I. (2005). Exploring ecological and socio-economic issues for improving area enclosure management: A case study from Ethiopia. Drylands Coordination Group, 4(38), 55p.

- Nkonya, E., Pender, J., Kaizzi, C., Kato, E., & Mugarura, S. (2005). Policy options for increasing crop productivity and reducing soil nutrient depletion and poverty in Uganda. EPT Discussion Paper 134.

- Nkonya, E., Pender, J., & Kato, E. (2008). Who knows? Who cares? The determinants of enactment, awareness, and compliance with community Natural Resource Management regulations in Uganda. Environment and Development Economics, 13(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X0700407X

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Opondo, C., German, L., Stroud, A., & Engorok, O. (2006). Lessons from using participatory action research to enhance farmer-led research and extension in southwestern Uganda. African Highlands Initiative (AHI). Works Papers # 3.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2001). Vulnerability and polycentric governance systems. IHDP (International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change) Newsletter UPDATE No. 3, 1, 3–4.

- Otsuka, K., & Place, F. (2014). Evolutionary changes in land tenure and agricultural intensification in sub-Saharan Africa (p. 47). United Nation University Working Paper. 2014/051(November). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199687107.013.015

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2007). Transition towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resources Management, 21(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-006-9040-4

- Pender, J., Ssewanyana, S., Edward, K., & Nkonya, E. (2004). Linkages between poverty and land management in rural Uganda: evidence from the Uganda National Household Survey, 1999/2000. Environment and Production Technology Division Discussion Paper No. 122. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Pretty, J., &Bharucha, Z. P. (2014). Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems. Annals of Botany, 114(8), 1571–1596. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcu205 25351192

- Pretty, J. (2008). Agricultural sustainability: Concepts, principles and evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 363(1491), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2163 17652074

- Pretty, J., Toulmin, C., & Williams, S. (2011). Sustainable intensification in African agriculture. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 9(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2010.0583

- Razzaq, A., Xiao, M., Zhou, Y., Anwar, M., Liu, H., & Luo, F. (2022). Towards sustainable water use: Factors influencing farmers’ participation in the informal groundwater markets in Pakistan. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 944156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.944156

- Rwakakamba, T. S. (2009). How effective are Uganda’s environmental policies? Mountain Research and Development, 29(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.1092

- Sanginga, P. C., Muhanguzi, G., & Kamugisha, R. (2003). Bylaws and local policies for improved agriculture and natural resources management in the highlands of Southwestern Uganda. Natural Resources Systems Programme Final Technical Report-7856. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08cf6e5274a31e0001570/R7856AnnE.pdf#page=14

- Sanginga, P., Kamugisha, R., Martin, A., Kakuru, A., & Stroud, A. (2004). Facilitating participatory processes for policy change in natural resource management: Lessons from the highlands of Southwestern Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 9(2012), 950–962. http://naro.go.ug/UJAS/ujas.html

- Sanginga, P. C., Abenakyo, A. R., Martin, M., Muzira, A., & Kamugisha, R. (2009). Tracking outcomes of participatory policy learning and action research: Methodological issues and empirical evidence from participatory bylaw reforms in Uganda [Paper presentation]. Farmer First Revisited Conference (2007, Sussex, England). Papers Presented. Future Agricultures Consortium; Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Sussex, GB (p. 17).

- Sanginga, P. C., Kamugisha, R. N., & Martin, A. M. (2010). Strengthening social capital for adaptive governance of natural resources: A participatory learning and action research for bylaws reforms in Uganda. Society & Natural Resources, 23(8), 695–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802653513