Abstract

Women’s presence in the Indonesian parliament is an opportunity to be involved in the democratic processes. Their political skills and leadership styles can be studied through the gender equality, disability and social inclusion (GEDSI) approach. This research aims to investigate the effect of political skills and leadership styles of women politicians who implement the GEDSI on public satisfaction. This study based on a quantitative, the quantitative stage held a survey of 188 respondents which were then analyzed using PLS-SEM. To strength information, we derived from interviews and focus group discussions with stakeholders and women politicians. The research shows that social astuteness, especially political skills, directly and indirectly, influenced public satisfaction with the partial mediating role of achievement leadership. Political skills through apparent sincerity had interactions with public satisfaction, where the directive leadership could be a partial mediation role. Finally, cognitive social capital as political skills influenced public satisfaction with the partial mediating roles of supportive leadership, participative leadership and achievement leadership. This study also found that network ability and interpersonal influence had no significant effect on public satisfaction. Women politicians who apply the GEDSI approach become their political skills that benefit a leadership style as well as encourage more accommodative and substantial political decision-making.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Social astuteness influenced public satisfaction, both directly and indirectly.

Political skills through apparent sincerity had interactions with public satisfaction, whereas directive leadership could be a partial mediation role.

Leadership style had a significant and direct interaction on public satisfaction.

Women’s network ability and interpersonal influence had no significant effect on public satisfaction.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Women’s political participation is a fundamental prerequisite for gender equality and true democracy as it facilitates their direct involvement in public decision-making and also ensures foster accountability (Khelghat-Doost & Sibly, Citation2020). UN-Women encourages women’s political participation and good governance, to ensure that decision-making processes are participatory, responsive, fair and inclusive. Each country needs leaders who can implement Gender Equality, Disability, and Social Inclusion (GEDSI) as an indicator to measure the progress of human resources and their sustainability (van der Vleuten & van Eerdewijk, Citation2020). According to Pratiwi et al. (Citation2022), the GEDSI approach is an effort to ensure that every individual from all backgrounds – including women and people of diverse gender, persons with disabilities as well as people who face other marginalization – can access, use and contribute fairly.

Women’s involvement in politics should be a great opportunity to participate in the democratic ecosystem in this country, as stated in Law Number 2 of 2011 about Political Parties which stipulates a minimum of 30% for women’s representation in parties establishment and formation, also Law Number 7 of 2017 about General Elections stipulates that each political party must have women representation of 30% parliament candidate. Women politician cadres often do not have qualified political skills thus they are still trapped in cultural and social assumptions in society (Håkansson, Citation2021; van der Pas & Aaldering, Citation2020). In the 2019 elections in Indonesia, women’s representation in the National Parliament (DPR-RI) is 120 (20.8%), this showed that the minimum target of their representation has not been achieved (Mazrieva, Citation2022; Prihatini, Citation2020; Salviana & Soedarwo, Citation2019).

The unfulfilled allocation emphasizes that women political cadres seem affirmative action in achieving the quota, despite the problem of knowledge and skills are still weak (Asmorojati, Citation2019). Indirectly, this shows the impression that women are not yet ready from their knowledge aspects such as education, experience, political attitudes and political skills. In another hand, the demand to achieve 30% women representation become gender biased. Women are often perceived as inferior figures who are feminine and gentle thus they are considered unsuitable for leadership in organizational ecosystems despite strongly patriarchal views in the country (Nurbayani et al., Citation2019; Nurbayani, Dede, & Malihah, Citation2022; Nurbayani, Malihah, et al., Citation2022).

To create strong women leaders, political skills and leadership style are aspects that need more attention in women caders’ education. Women must represent themselves through knowledge, skills and performance to get satisfaction from the public (Schwarz et al., Citation2020). Political skills are the ability to navigate politics effectively through negotiation and influence, through developing, maintaining, as well as improving interpersonal and social reputations (Chen et al., Citation2022; Ferris et al., Citation2007). Meanwhile, leadership style denotes an individual’s unique manner of guiding, encompassing distinct problem-solving (Chikazhe et al., Citation2023; Farhan, Citation2022). Political skills and leadership style are important in shaping public satisfaction based on expectations and actual outcomes (Zhou et al., Citation2021).

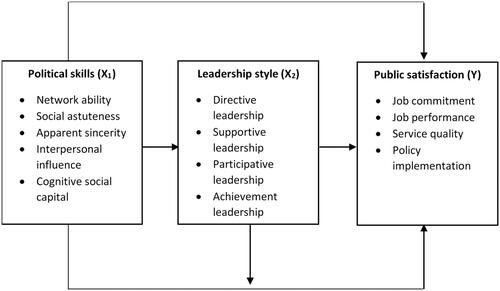

Personal political skills are reflected in their actions either to influence and advance self or organizational agendas (Gansen-Ammann et al., Citation2017; Zaman et al., Citation2019). Political skills can be seen from network ability, social astuteness, apparent sincerity, interpersonal influence, and cognitive social capital (Ferris et al., Citation2007). Women’s political skills individually who are skilled and resilient to the social dynamics. This is different from leadership styles which in knowledge and practical skills to influence society (Alblooshi et al., Citation2021; Garfield et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the leadership approach is used by women politicians in creating and influencing society (Saleem et al., Citation2020). To measure political leadership style can refer to directive leadership, supportive leadership, participative and achievement leadership.

Research on political skills and leadership style is generally associated with public satisfaction (Salajeghe & Faramarzi, Citation2016; Zulkifli et al., Citation2017). Political skills are also used as a practical basis for leadership styles (Frieder et al., Citation2019; Sawitri et al., Citation2021). Without qualified political skills, women politicians would fail and be considered weak because they were confined to the patriarchal culture (Sumbas, Citation2020). In contrast to previous research, this research discusses how female politicians use the GEDSI approach with their political skills and leadership style to give satisfaction to society in Indonesia as a novelty. Women’s participation dynamics do not only occur in Indonesia, but also in other countries with Muslim-majority populations. Their participation in public spaces, let alone political contestation, remains far from being a societal norm. In Middle Eastern countries, it is few for women to hold important positions in government and parliament (Shalaby, Citation2018). Therefore, this research aims to investigate the effect of political skills on women politicians who implement the GEDSI approach to public satisfaction. Our research can be an inspiration for analogous studies in Muslim-majority countries, particularly within the countries that have democratic and semi-democratic governments, where entrenched patriarchal social structures persist.

2. Methodology

This study referred to a quantitative approach to know women’s political skills and leadership styles on public satisfaction. A quantitative method is explaining and revealing the deep interaction phenomena between complex variables (Dede et al., Citation2024; Guetterman et al., Citation2019; Oflazoglu, Citation2017). Quantitative analysis in this study used Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to know the variables’ interactions, also mediating variables both direct and indirect relationships. PLS-SEM is useful to understand the feasibility of operationalized theoretical models by causal relationships between variables (Shiau et al., Citation2019). The research respondents were selected using a non-probability sampling technique (Nurbayani et al., Citation2023), taking their perceptions and expectations of women politicians according to women’s political skills and leadership style. A survey was conducted online using Google Forms to 188 respondents, the demographic description is presented in with conceptual interactions depicted in .

Table 1. Profile of research respondents.

We used a questionnaire (Likert’s scale) which contains answer choices from strongly disagree to strongly agree (1–5 points). The political skills variable was developed from indicators according to Ferris et al. (Citation2007) which consisted of network ability, social astuteness, apparent sincerity, interpersonal influence, and cognitive social capital. Each item of the political skill variable is stated to be valid and reliable with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.951. The leadership style variable was developed from indicators of directive leadership, supportive leadership, participative and achievement leadership (Saleem et al., Citation2020). Each item of the leadership style variable is declared valid and reliable with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.961. Finally, public satisfaction variables consist of job commitment, job performance, service quality and policy implementation (Schwarz et al., Citation2020). Each item for women’s leadership style is declared valid and reliable with Cronbach’s Alpha 0.968. All Cronbach’s alpha is very high with a 95% confidence level because the values are up to 0.80 (Ismail et al., Citation2022).

We continued with a descriptive analysis that explores interview and focus group discussions (FGD) data from women stakeholders and politicians both from national and religious-based parties. This analysis was useful for seeing the extent to which women’s political skills and leadership styles affect public satisfaction, as well as data triangulation (Nurbayani, Dede, & Widiawaty, Citation2022). Data findings from these processes are useful in strengthening statistical analysis and revealing latent constructs that are unique, complete, and coherent (Muñoz-Pascual et al., Citation2019; Newman & Constantinides, Citation2021). Our research hypothesizes that political skills (X1) and leadership style (X2) have an influence on public satisfaction (Y). This significance status refers to the t-value and p-value with a confidence level of 95%.

3. Results

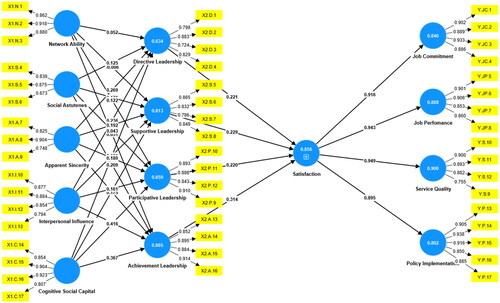

Before doing structural path analysis, a study requires a measurement model to determine the reliability and validity of each construct. Individual constructs were tested to know reliability items, it needs standardized loading factors to reveal the correlation of construct variables. The construct reliability test referred to the comparison of the average variance extracted (AVE) value. Correlation between construct variables with the reliability value (latent variables) can be compared with the composite reliability (CR), considered reliable if the value was greater than 0.50 (Achjari, Citation2004; Hair et al., Citation2011). The measurement model displayed the factor loadings (FL), alpha values (t-statistics), AVE, and CR (). FL showed all constructs have values of 0.673–0.938 (good) as well as the t-statistic indicated value of 0.713–0.94, whereas AVE has values of 0.641–0.809 > 0.50 (reliable) (Dede et al., Citation2022). TCR showed all constructs have a value of 0.841–0.955 > 0.60 which means that they have sufficient high internal consistency for the measurement model.

Table 2. Measurement model.

The discriminant validity revealed no high correlation based on cross-loading, this meets the prerequisites in Fornell-Larcker and cross-loading values (Hair et al., Citation2011). In these criteria, the square root of AVE must be higher than the correlation value in the model (). This shows that each value has fulfilled the prerequisite criteria in the discriminant. The coefficient of determination (R2) of the measurement model shows 85.6%, which meant that public satisfaction can be explained by political skills and leadership style (). R2 value also explains the total variance of leadership style consisting of 63.4% directive leadership, 61.3% supportive leadership, 65.9% participative leadership, and 66.5% achievement leadership. The R2 value is quite high and thus it can explain the variable interactions (Dede et al., Citation2023; Rachmadita et al., Citation2023; Susiati et al., Citation2022; Widiawaty et al., Citation2022).

Table 3. Discriminant validity of construct.

3.1. Political skills on public satisfaction

The direct influence on structural path analysis in showed that political skill from social astuteness (β = 0.144, t = 2.071, p = 0.038), apparent sincerity (β = 0.198, t = 2.809, p = 0.005), and cognitive social capital (β = 0.326, t = 4.015, p = 0.000) has a significant effect on public satisfaction. On the other hand, political skill variables for network ability (β = 0.047, t = 0.905, p = 0.366) and interpersonal influence (β = 0.172, t = 1.398, p = 0.001) have no significant effect on public satisfaction.

Table 4. Direct relationship between variables.

3.2. Political skills on the leadership style

Structural path analysis showed that the political skill variable for network ability (β = 0.052, −0.006, 0.122, 0.031, t = 0.867, 0.090, 1.832, 0.497, p = 0.386, 0.928, 0.067, 0.619) has no significant effect on leadership style directive leadership, supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership. Meanwhile, social astuteness (β = 0.179, 0.209, t = 2.053, 2.318, p = 0.040, 0.020) is known to have a significant effect on supportive leadership style and achievement leadership. This is different from social astuteness (β = 0.125, 0.043, t = 1.498, 0.476 p = 0.134, 0.634) which was not significant to the influence of directive leadership and participative leadership styles. Significant interaction appeared in the apparent sincerity indicator political skill variable (β = 0.269, 0.192, 0.180, 0.175, t = 3.254, 2.112, 2.410, 2.046, p = 0.001, 0.035, 0.016, 0.041) on directive leadership, supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership.

Political skills variable, precisely on interpersonal influence (β = 0.236, 0.191, 0.161, 0.128, t = 1.296, 1.093, 1.776, 1.501, p = 0.002, 0.003, 0.076, 0.133) showed no significant interaction with directive leadership, supportive leadership style leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership. Slightly different conditions appear in cognitive social capital (β = 0.311, 0.416, 0.367, t = 2.953, 4.522, 3.829, p = 0.003, 0.000, 0.000) which had a significant effect on supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership styles. This study also showed that cognitive social capital (β = 0.218, t = 1.929, p = 0.054) did not have a significant relationship to the influence of directive leadership style.

3.3. Leadership style on public satisfaction

Referred to the structural path analysis, the leadership style variable for directive leadership (β = 0.221, t = 3.356, p = 0.001), supportive leadership (β = 0.229, t = 3.248, p = 0.001), participative leadership (β = 0.220, t = 3.036, p = 0.002), and achievement leadership (β = 0.314, t = 3.880, p = 0.000) had a significant effect on public satisfaction. This means that leadership style is highly considered by society through policy implementation and women politicians’ appearances.

3.4. Leadership style on public satisfaction

The indirect influence on the structural path result in showed that the female leadership style for directive leadership (β = 0.012, t = 0.777, p = 0.437), supportive leadership (β = −0.001, t = 0.086, p = 0.931), participative leadership (β = 0.027, t = 1.453, p = 0.146), and achievement leadership (β = 0.010, t = 0.466, p = 0.641) were not mediated by the relationship between political skills (network ability) and public satisfaction. The female leadership style for leadership achievement (β = 0.066, t = 2.004, p = 0.045) was able to mediate the relationship between political skill (social astuteness and public satisfaction). Different things can be seen from the female leadership style for directive leadership (β = 0.028, t = 1.295, p = 0.195), supportive leadership (β = 0.041, t = 1.629, p = 0.103), and participative leadership (β = 0.010, t = 0.441, p = 0.659) which was not mediated by the relationship between political skills as an indicator of social astuteness and public satisfaction.

Table 5. Indirect relationship between leadership style mediated political skills and public satisfaction relation.

In the women’s leadership style, the directive leadership indicator (β = 0.059, t = 2.437, p = 0.015) was able to mediate the relationship between political skill variables, especially in apparent sincerity and public satisfaction, whereas for supportive leadership (β = 0.044, t = 1.724, p = 0.085), participative leadership (β = 0.040, t = 1.732, p = 0.083), and achievement leadership (β = 0.055, t = 1.874, p = 0.061) were not mediated by a relationship between political skill variables (apparent sincerity and public satisfaction). The same thing can be seen in the leadership style variable for directive leadership (β = 0.052, t = 1.922, p = 0.055), supportive leadership (β = 0.044, t = 1.711, p = 0.087), participative leadership (β = 0.036, t = 1.627, p = 0.104), and achievement leadership (β = 0.040, t = 1.333, p = 0.183) which was not mediated by the relationship between political skills as an indicator of interpersonal influence and public satisfaction.

Meanwhile, the women’s leadership style for supportive leadership (β = 0.071, t = 2.116, p = 0.034), participative leadership (β = 0.092, t = 2.500, p = 0.012), and achievement leadership (β = 0.115, t = 2.538, p = 0.011) was able to mediate the relationship between political skill variables as cognitive social capital indicators and public satisfaction. Besides that, the female leadership style variable for the directive leadership indicator (β = 0.048, t = 1.538, p = 0.124) was not mediated by the relationship between the political skills variable – cognitive social capital indicator and public satisfaction.

4. Discussion

The research findings showed that network ability and interpersonal influence have no relationship with leadership style or influence on public satisfaction. Network abilities and interpersonal influence cannot be as important elements in providing satisfaction to the public regarding political skills (Munyon et al., Citation2015). This is supported by interviews that network abilities are carried out by women politicians who are more supportive of personal interests than those of society. In building networks with groups that support their rights and interests, they need to manage relationships with groups that do not support them in an appropriate way (Goertz & Mazur, Citation2008). Network ability is usually determined by social capital, which ultimately supports political promises to become true. The GEDSI approach taken by women politicians has not shown satisfactory interpersonal influence on the public, where women often do not use the proper strategy in campaigning for GEDSI as their political vision and mission. Female politicians have not realized that these skills are effective for understanding other people in the workplace and using that knowledge to influence others as well as to enhance one’s personal and/or organizational goals (Thompson et al., Citation2017).

In social astuteness as political skills, there were direct and indirect effects on public satisfaction with the partial mediation of achievement leadership. Women politicians often show social astuteness in their leadership (Harp et al., Citation2016; Kwon, Citation2020; Treadway et al., Citation2013). The FGD showed that the criteria for women leaders need to have intelligence and the ability to influence others, also have policies that are applied in society. In this case, with the achievement leadership style, women politicians are judged to focus on political goals. Women politicians are capable to formulate GEDSI-based policies, this is evidenced by their success story in promoting public policies such as the sexual violence law and gender issues. This policy is part of the women’s leadership style by implementing achievement leadership, which is proof that they are empowered and implement gender-responsive policies. Women’s representatives are considered to have an important role in producing each policy according to the perspective of gender sensitivity, needs and experience (Agustyati, Citation2020).

Apparent sincerity in political skills, directly and indirectly, affects public satisfaction with the partial mediation of directive leadership (Kimura, Citation2015; Robinson et al., Citation2019; Todd et al., Citation2009). Sincerity is very necessary in Indonesian politics which still involves a lot of money practices and handing out public positions or projects. Women politicians with apparent sincerity cannot be separated from their perception of femininity thus they are considered to have more sensitivity than men. FGD showed that women’s representatives are not only sensitive to differences in sex and gender, but also to constraints in various political-cultural arenas and political processes or real achievements from feminist intervention. This directive leadership style is effective in situations where there is a goal of achieving a political policy, it is necessary to consider the skills and expertise to complete that issue (Cwalina & Drzewiecka, Citation2019). Political skill practice for women politicians is considered capable of providing satisfaction with apparent sincerity that is implemented on how to create knowledge related to inclusive policies and their capability to reform policy governance according to GEDSI.

Cognitive social capital as the political skills, directly and indirectly, influence public satisfaction with the partial mediating role of supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership. Women need to have potential political abilities that refer to knowledge and cognitive aspects. These can have an impact on influencing political policies and actions for society (Bashir & Jan, Citation2021; Kwon, Citation2020). The interviews revealed that women politicians are considered to increase their potential political ability by helping to understand issues related to rights and interests that are equal, fair and without discrimination. Cognitive social capital is considered to support various types of leadership styles (supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership). In the supportive leadership style, cognitive social capital can show a sense of responsibility in the community. Supportive women politicians often look to society’s welfare and create a sense of belonging. In this case, women politicians are encouraged to implement GEDSI in a twin-track approach, they should provide opportunities to provide equal rights and opportunities, including those from all minority and disabilities groups (Opoku et al., Citation2021).

In the participative leadership style, cognitive social capital can create good interactions with society, especially to formulate political visions and missions according to public satisfaction. Women’s political leadership can ensure that their perspectives and experiences are included in decision-making (Gordon et al., Citation2021). Finally, leadership styles such as achievement leadership, cognitive social capital should be resources for women politicians who may focus on performance to create accountability. Women’s political participation and good governance are considered to ensure that the decision-making process is participatory, gender-responsive, fair and inclusive. These efforts are focused on strategic points that can advance women by catalyzing broad and long-term impacts (Pratiwi et al., Citation2022).

Women’s political participation in Indonesia is more flexible than those in other Muslim-majority countries, It has even been definitively demonstrated that a woman can ascend the highest leader and head of state, Megawati Soekarnoputri (5th President of Indonesia from 2001 to 2004). In Iran, especially Kurdish women, the patriarchal social framework has created injustice for women to participate in politics from voicing political ideals to realizing their collective rights (Shakiba et al., Citation2021). The inequality of political rights for Kurdish women can actually be traced to other minority ethnic groups as well, especially non-Persian ones, which emerged as an implication of long-standing social, economic, and cultural disparities in Iranian society (Ahmady et al., Citation2023). All non-Persian ethnic groups felt unequal and dissatisfied with government policies that favored the dominant ethnic group there, which ultimately triggered demands for justice, equitable development, and national solidarity (Ahmady, Citation2023). However, in Türkiye, women’s grassroots activism and attempts to enter high-level politics often don’t lead to seats at the decision-making table. Their political engagement is marked by high voter turnout, involvement in voter recruitment, and active campaigning for conservative and pro-religious parties, especially in pro-Kurdish parties (Drechselová, Citation2020; Tajali, Citation2023). This political inequality is suspected to be rooted in a sense of Turkish racial superiority over other races due to their role in building Islamic civilization until 1924 (Azzam, Citation2023). On the other hand, economic inequality resulting in fierce competition for jobs has also triggered hate crimes against minority groups extending into the political realm. This contrast arises from political regulations in Indonesia mandating that every institution must ensure up to 30% representation and inclusion of female members (Law Number 2 of 2011), coupled with women’s freedom to pursue higher education and careers that implied increasing women’s representation in government from 1987 to 2019 elections (Aspinall et al., Citation2021; Nurbayani & Dede, Citation2022). The ideal role played by women in politics is born in a deeply rooted social and cultural context if they are capable of leading, formulating policy and executing programmes. Indonesia is interesting because in its history female political figures have emerged as leaders of past kingdoms such as Kalinga (Queen Shima), Majapahit (Queen Tribhuwanatunggadewi Jayawishnuwardhani), and Samudera Pasai (Sultanah Nihrasyiah).

5. Conclusion

Women’s political participation ensures that the decision-making process is participatory, responsive, fair and inclusive. Research on women politicians based on GEDSI is an evaluation to understand the benefits and resources targeted while preventing side effects from development interventions. The research showed that political skill, especially social astuteness, directly and indirectly, influenced public satisfaction with the partial mediating role of achievement leadership. Political skills for apparent sincerity also influence public satisfaction with the mediating role of partial directive leadership. Political skills reflected in cognitive social capital influenced public satisfaction with the partial mediating role of supportive leadership, participative leadership, and achievement leadership. This study succeeded in revealing that network ability and interpersonal influence have an insignificant effect on public satisfaction. Thus, the research hypothesis cannot be fully accepted because only some components of political skills and leadership style influenced public satisfaction. Women politicians who apply the GEDSI approach become political skills that benefit a leadership style for them because that encourages more accommodative and substantial political decision-making. Further research is needed with a gender-comparative perspective related to GEDSI.

Public Interest Statement_Cogent Social Sci_Malihah et al_2023.docx

Download MS Word (13.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Moh. Dede (UPI and UNPAD) and Millary Agung Widiawaty (University of Birmingham and CIGESS) for their beneficial discussion in the manuscript preparation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elly Malihah

Elly Malihah is a professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences Education (FPIPS), Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (UPI). Elly completed a PhD degree at Universitas Padjadjaran (UNPAD). She is focused on policy studies, education and family, gender politics, and social development. She is also active as a secretary at the university senate and a member of the UPI’s Center of Excellence.

Siti Nurbayani

Siti Nurbayani is an associate professor at the FPIPS UPI. She completed a PhD degree in social science education from. Siti focuses on development studies, family and women, local wisdom, and community empowerment. She is known as the Vice Dean of FPIPS UPI for student empowerment.

Siti Komariah

Siti Komariah is an associate professor at the FPIPS UPI. She got a PhD degree from Universiti Malaya, Malaysia. She was the head of Sociology Education Program, both undergraduate and postgraduate in FPIPS UPI. Siti Komariah focuses on sociology and sociology education as the main research subject.

Etty Sisdiana

Etty Sisdiana in a senior researcher at the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (BRIN). Etty worked as a staff in the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture with specialize in education and policies. She completed a Ph.D. degree from Universitas Negeri Jakarta.

Yendri Wirda

Yendri Wirda in a researcher at the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (BRIN). She got the higher education degrees from IPB University. Yendri focuses on education, inclusiveness, and disabilities research.

Lingga Utami

Lingga Utami graduated from post-graduate program in sociology education at UPI. She involved in several projects from the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture. Lingga, currently, active in the Solve Education.

Rengga Akbar Munggaran

Rengga Akbar Munggaran is a researcher from ‘Asosiasi Pendidik dan Peneliti Sosiologi Indonesia’ or AP3SI. He graduated from Sociology Education at UPI, also Sociology at Universitas Indonesia. Rengga focuses on social development, gender studies, and social movement.

References

- Achjari, D. (2004). Partial least squares: Another method of structural equation modeling analysis. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Indonesia, 19(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.22146/jieb.6599

- Ahmady, K. (2023). From border to border: Research study on identity and ethnicity in Iran. Avaye Buf. https://avayebuf.com/2023/10/21/from_border_to_border/

- Ahmady, K., Hemmati, R., Tabari, S., Hosseini, S. M. J., Sorkhabi, H., Shahmoradi, K., Maroufi, M., Jazbi, K., Rashidi, H., & Vali, A. (2023). Ethnic, national and identity demands in Iran on the axis of justice and development: A grounded theory method study among five major ethnic groups. European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(5), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejsocial.2023.3.5.448

- Agustyati, K. N. (2020). Arah kebijakan afirmasi perempuan dalam ruu pemilu representasi deskriptif vs representasi substantif. Jurnal Keadilan Pemilu, 3, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.55108/jkp.v1i3.163

- Alblooshi, M., Shamsuzzaman, M., & Haridy, S. (2021). The relationship between leadership styles and organisational innovation: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(2), 338–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-11-2019-0339

- Asmorojati, A. W. (2019 The urgency of political education to women in the perspective of Muhammadiyah and democracy [Paper presentation]. 3rd International Conference on Globalization of Law and Local Wisdom (ICGLOW 2019) (pp. 255–259). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icglow-19.2019.64

- Aspinall, E., White, S., & Savirani, A. (2021). Women’s political representation in Indonesia: Who wins and how? Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 40(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868103421989720

- Azzam, A. A. (2023). Turki, negara memiliki rasisme dan diskriminasi etnis Arab dan Afrika. Kompasiana. https://www.kompasiana.com/abdurrofi00318/644b76594addee30e77a9bf3/turki-negara-memiliki-rasisme-dan-diskriminasi-etnis-arab-dan-afrika?

- Bashir, H., & Jan, M. A. (2021). Political apprenticeship and women leadership in a patriarchal society: Nasim Wali Khan’s political struggle through acquired skills. Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ), 5(1), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/5.1.21

- Chen, H., Jiang, S., & Wu, M. (2022). How important are political skills for career success? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(19), 3942–3968. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1949626

- Chikazhe, L., Bhebhe, T., Tukuta, M., Chifamba, O., & Nyagadza, B. (2023). Procurement practices, leadership style and employee-perceived service quality towards the perceived public health sector performance in Zimbabwe. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2198784. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2198784

- Cwalina, W., & Drzewiecka, M. (2019). Who are the political leaders we are looking for? Candidate positioning in terms of leadership style: A cross-cultural study in Goleman’s Typology. Journal of Political Marketing, 18(4), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2019.1678908

- Dede, M., Sunardi, S., Lam, K. C., Withaningsih, S., Hendarmawan, H., & Husodo, T. (2024). Landscape dynamics and its related factors in the Citarum River Basin: A comparison of three algorithms with multivariate analysis. Geocarto International, 39(1), 2329665. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2024.2329665

- Dede, M., Susiati, H., Widiawaty, M. A., Lam, K. C., Aiyub, K., & Asnawi, N. H. (2023). Multivariate analysis and modeling of shoreline changes using geospatial data. Geocarto International, 38(1), 2159070. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2022.2159070

- Dede, M., Wibowo, S. B., Prasetyo, Y., Nurani, I. W., Setyowati, P. B., & Sunardi, S. (2022). Water resources carrying capacity before and after volcanic eruption. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 8(4), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.22034/GJESM.2022.04.02

- Drechselová, L. G. (2020). Women’s political involvement and local politics in Turkey. In Local power and female political pathways in Turkey: Cycles of exclusion (pp. 1–40). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47143-9_1

- Farhan, B. Y. (2022). Women leadership effectiveness: Competitive factors and subjective and objective qualities. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2140513. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2140513

- Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Perrewé, P. L., Brouer, R. L., Douglas, C., & Lux, S. (2007). Political skill in organizations. Journal of Management, 33(3), 290–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300813

- Frieder, R. E., Ferris, G. R., Perrewé, P. L., Wihler, A., & Brooks, C. D. (2019). Extending the metatheoretical framework of social/political influence to leadership: Political skill effects on situational appraisals, responses, and evaluations by others. Personnel Psychology, 72(4), 543–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12336

- Gansen-Ammann, D. N., Meurs, J. A., Wihler, A., & Blickle, G. (2017). Political skill and manager performance: Exponential and asymptotic relationships due to differing levels of enterprising job demands. Group & Organization Management, 44(4), 718–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601117747487

- Garfield, Z. H., von Rueden, C., & Hagen, E. H. (2019). The evolutionary anthropology of political leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.09.001

- Goertz, G., & Mazur, A. (2008). Mapping gender and politics concepts: Ten guidelines. In G. Goertz & A. Mazur (Eds.), Politics, gender and concepts: Theory and methodology (pp. 14–45). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511755910.002

- Gordon, R., O’Connell, S., Fernandes, S., Rajagopalan, K., & Frost, K. (2021). Women’s political careers: Leadership in practice. Westminster Foundation for Democracy.

- Guetterman, T. C., Babchuk, W. A., Howell Smith, M. C., & Stevens, J. (2019). Contemporary approaches to mixed methods–grounded theory research: A field-based analysis. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689817710877

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Håkansson, S. (2021). Do women pay a higher price for power? Gender bias in political violence in Sweden. The Journal of Politics, 83(2), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1086/709838

- Harp, D., Loke, J., & Bachmann, I. (2016). Hillary Clinton’s Benghazi hearing coverage: Political competence, authenticity, and the persistence of the double bind. Women’s Studies in Communication, 39(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2016.1171267

- Ismail, A., Widiawaty, M. A., Jupri, J., Setiawan, I., Sugito, N. T., & Dede, M. (2022). The influence of Free and Open-Source Software-Geographic Information System online training on spatial habits, knowledge and skills. Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 18(1), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.17576/geo-2022-1801-09

- Khelghat-Doost, H., & Sibly, S. (2020). The impact of patriarchy on women’s political participation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(3), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i3/7058

- Kimura, T. (2015). A review of political skill: Current research trend and directions for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(3), 312–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12041

- Kwon, H. W. (2020). Performance appraisal politics in the public sector: The effects of political skill and social similarity on performance rating. Public Personnel Management, 49(2), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026019859906

- Mazrieva, E. (2022). Partai terapkan kultur patriarkis, realisasi kuota 30 persen perempuan di DPR terhambat. https://www.konde.co/2022/02/kultur-partai-hambat-realisasi-kuota-30-persen-wakil-perempuan-di-dpr.html/

- Muñoz-Pascual, L., Galende, J., & Curado, C. (2019). Human resource management contributions to knowledge sharing for a sustainability-oriented performance: A mixed methods approach. Sustainability, 12(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010161

- Munyon, T. P., Summers, J. K., Thompson, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (2015). Political skill and work outcomes: A theoretical extension, meta-analytic investigation, and agenda for the future. Personnel Psychology, 68(1), 143–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12066

- Newman, D., & Constantinides, S. (2021). Structural equation modeling with qualitative data that have been quantitized. In A. J. Onwuegbuzie & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Routledge reviewer’s guide to mixed methods analysis. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203729434-8

- Nurbayani, S., & Dede, M. (2022). The effect of COVID-19 on white-collar workers: The DPSIR model and its semantic aspect in Indonesia. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 10(3), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijscl.2022.550921.2592

- Nurbayani, S., Dede, M., & Malihah, E. (2022). Fear of crime and post-traumatic stress disorder treatment: Investigating Indonesian’s pedophilia cases. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 10(1), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.26811/peuradeun.v10i1.657

- Nurbayani, S., Dede, M., Utami, N. F., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2023). The implementation of COVID-19 health protocol: A higher students’ perspective. Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 19(1), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.17576/geo-2023-1901-14

- Nurbayani, S., Dede, M., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2022). Utilizing library repository for sexual harassment study in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. Heliyon, 8(8), e10194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10194

- Nurbayani, S., Komariah, S., Nurohim, S., & Nurhizkhy, D. (2019, March). Women’s leadership as top management in educational institution: Society construction and cultural dilemma [Paper presentation].2nd International Conference on Research of Educational Administration and Management (ICREAM 2018) (pp. 311–314). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icream-18.2019.65

- Nurbayani, S., Malihah, E., Dede, M., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2022). A family-based model to prevent sexual violence on children. International Journal of Body, Mind and Culture, 9(3), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.22122/ijbmc.v9i3.397

- Oflazoglu, S. (2017). Qualitative versus quantitative research. IntechOpen.

- Opoku, M. P., Nketsia, W., Alzyoudi, M., Dogbe, J. A., & Agyei-Okyere, E. (2021). Twin-track approach to teacher training in Ghana: Exploring the moderation effect of demographic variables on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Educational Psychology, 41(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1724888

- Pratiwi, A., Jaetuloh, A., Handayani, A. P., Tamyis, A. R., Wulandari, A. S., Primadata, A. P., Tsaputra, A., Ambarwati, A., Arina, Rahmawati, B., Wardhani, K. K., Chazali, C., Devika, D. A., Sari, D. K., Afrianty, D., Mariana, D., Widiyanto, D. J., Oceani, D. N., Widyaningsih, D., … Susilo, W. (2022). Kesetaraan gender, disabilitas dan inklusi sosial dalam praktik. Smeru Research Institute.

- Prihatini, E. S. (2020). Islam, parties, and women’s political nomination in Indonesia. Politics & Gender, 16(3), 637–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000321

- Rachmadita, R., Widiana, A., Rahmat, A., Sunardi, S., & Dede, M. (2023). Utilizing satellite imagery for seasonal trophic analysis in the freshwater reservoir. Journal of Multidisciplinary Applied Natural Science, 4(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.47352/jmans.2774-3047.188

- Robinson, G. M., Magnusen, M., & Kim, J. W. (2019). The socially effective leader: Exploring the relationship between athletic director political skill and coach commitment and job satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119834118

- Salajeghe, S., & Faramarzi, A. (2016). Explaining the role of political skills in the relationship between transformational leadership style of managers with staff job satisfaction (case study: Municipality of Bandar Abbas). International Business Management, 10(5), 3036–3041. https://doi.org/10.36478/ibm.2016.3036.3041

- Saleem, A., Aslam, S., Yin, H. B., & Rao, C. (2020). Principal leadership styles and teacher job performance: Viewpoint of middle management. Sustainability, 12(8), 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083390

- Salviana, V., & Soedarwo, D. (2019). A political education model of political parties in Indonesia. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 6(9), 134–140. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0609015

- Sawitri, H. S. R., Suyono, J., Istiqomah, S., Sarwoto, & Sunaryo, S. (2021). Linking leaders’ political skill and ethical leadership to organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of self-efficacy, respect, and leader–member exchange. International Journal of Business, 26(4), 70–89.

- Schwarz, G., Eva, N., & Newman, A. (2020). Can public leadership increase public service motivation and job performance? Public Administration Review, 80(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13182

- Shakiba, S., Ghaderzadeh, O., & Moghadam, V. M. (2021). Women in Iranian Kurdistan: Patriarchy and the quest for empowerment. Gender & Society, 35(4), 616–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211029205

- Shalaby, M. M. (2018). Women’s representation in the Middle East and North Africa. Oxford Bibliographies in Political Science, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199756223-0252

- Shiau, W. L., Sarstedt, M., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Internet research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Internet Research, 29(3), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-10-2018-0447

- Sumbas, A. (2020). Gendered local politics: The barriers to women’s representation in Turkey. Democratization, 27(4), 570–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1706166

- Susiati, H., Widiawaty, M. A., Dede, M., Akbar, A. A., & Udiyani, P. M. (2022). Modeling of shoreline changes in West Kalimantan using remote sensing and historical maps. International Journal of Conservation Science, 13(3), 1043–1056.

- Tajali, M. (2023). Women’s political representation in Iran and Turkey: Demanding a seat at the table. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474499484

- Thompson, G., Buch, R., & Kuvaas, B. (2017). Political skill, participation in decision-making and organizational commitment. Personnel Review, 46(4), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2015-0268

- Todd, S. Y., Harris, K. J., Harris, R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2009). Career success implications of political skill. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149(3), 279–304. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.3.279-304

- Treadway, D. C., Breland, J. W., Williams, L. M., Cho, J., Yang, J., & Ferris, G. R. (2013). Social influence and interpersonal power in organizations: Roles of performance and political skill in two studies. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1529–1553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410887

- van der Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz046

- van der Vleuten, A., & van Eerdewijk, A. (2020). The fragmented inclusion of gender equality in AU-EU relations in times of crises. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920918830

- Widiawaty, M. A., Lam, K. C., Dede, M., & Asnawi, N. H. (2022). Spatial differentiation and determinants of COVID-19 in Indonesia. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1030. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13316-4

- Zaman, U., Jabbar, Z., Nawaz, S., & Abbas, M. (2019). Understanding the soft side of software projects: An empirical study on the interactive effects of social skills and political skills on complexity–performance relationship. International Journal of Project Management, 37(3), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.015

- Zhou, X., Chen, S., Chen, L., & Li, L. (2021). Social class identity, public service satisfaction, and happiness of residents: The mediating role of social trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 659657. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659657

- Zulkifli, H., Nurdjannah, H., Muhammad, Y., & Amar, A. (2017 The effect of leadership style and competency towards employees’ work satisfaction and performance at governor office of South Sulawesi Province [Paper presentation]. 2nd International Conference on Accounting, Management, and Economics 2017 (ICAME 2017) (pp. 184–194). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icame-17.2017.14