Abstract

Market women in rural communities need health information and due to their work and settlement, looking into health information disseminating methods are critical to understand how they can be effectively reached. Hence, this study investigated the health information needs and dissemination methods available to market women in rural communities. The study employed a qualitative research approach to investigate the phenomenon among market women within the Keta Municipality of Ghana. Three rural communities within the Keta municipality were employed for the study. The study employed the interpretivist research paradigm, semi-structured interview and focus group discussion for the collection of qualitative data from market women and public health professionals. The convenience sampling technique was used for the selection of market women and the purposive sampling for the selection of health professionals who participated in the study. The findings of the study revealed that the rural market women needed health information on personal hygiene, nutrition, rest and illness to take care of themselves. Particularly, the study established that the dissemination of health information to market women in their local dialect enabled the dissemination efforts to be effective. For implication, the study highlights the crucial need for targeted health information dissemination by stakeholders to help reach market women in rural communities and the need for further research to look into strengthening health dissemination efforts in other rural communities and also include women in other occupations such as farmers among others.

Introduction

Information affects people’s lives, especially their means of subsistence, and one of the main factors contributing to poverty among rural women could be attributed to their limited access to information. It has been observed that, all persons including market women are compelled by circumstances to look for information in order to find a solution that may not be readily apparent. Women in underdeveloped nations are perceived to require a variety of information, including health information about themselves and their children (Nargund, Citation2009; Yakong et al., Citation2010). Health information is information on a person’s medical history and present health status or concerns, such as biographical data and clinical data detailing their medical conditions, history of care, and current therapy, among other things (Ezema, Citation2016).

The transfer or interchange of information from one entity to another or one location to another can be viewed as the medium or channels of information dissemination. It is intended to be an action that must elicit a response, whether positive or negative, and as such, information transmission cannot be a one-way event. A rural town is a place with a small population that is characterized by high illiteracy and insufficient commercial organizations (Steinf & Zapletalov, Citation2016). Health information is most valuable when it reaches the individuals for whom it is meant. People who have access to health information are more likely to avoid the impacts of preventable and non-preventable diseases (Sokey et al., Citation2018).

One of the cornerstones for women’s progress and empowerment has been their ability to obtain and access good information (Arthur et al., Citation2019). Information has shown to be critical in our daily lives and in virtually every organization (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2012; Owusu & Kankam, Citation2020). Women now have access to knowledge and literacy skills that were previously unavailable to them due to advancements in Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) (Fauzi et al., Citation2020; Gallardo-Echenique et al., Citation2015; Shopova, Citation2014; Sinha & Bagarukayo, Citation2019). Women’s access to information has been considered as a method for them to interact and actively participate in events that require their input.

Women’s advocacy in underdeveloped countries for them to be actively involved in getting access to the internet is rare, even if they have the opportunity to do so because most of them lack the necessary abilities to fully access the contents (Garcia et al., Citation2009). However, in Sub-Saharan countries such as Ghana, most unlearned individuals in cities, regardless of their educational status, religious views, or gender, use the internet to obtain health information (Ashcroft & Rayner, Citation2011). Studies on the information needs of women in rural areas in Africa often conclude that their information needs cover a wide range of topics, including health, economy, farming operations, monetary concerns, marketing tactics, and harvesting (Amu, Citation2005; Ogunlela & Mukhtar, Citation2009).

Rural societies in Ghana are characterized by a variety of health-related challenges, such as insufficient healthcare infrastructure, lousy roads, and a lack of health information, making it difficult to obtain health information. There have been few research in Ghana on the difficulties that rural people have in accessing health information (Sokey & Adisah-Atta, Citation2017). When it comes to delivering health information to women in rural areas, providing them with smart gadgets and internet access will not solve all of their problems (Parmar, Citation2010). As a result, there is a need to investigate efficient means of disseminating health information to them, as well as how such methods might be improved.

Rural towns in Ghana confront a variety of barriers to accessing reliable and timely health information, limiting residents’ ability to make educated decisions about their health and overall well-being (Sokey et al., Citation2018; Yakong et al., Citation2010). Some of the causes have been attributed to insufficient and outdated methods of delivering health information in these rural areas, leaving them uninformed about effective ways to tackle preventable health concerns (Arthur et al., Citation2019; Ifukor & Omogo, Citation2013; Nwagwu & Ajama, Citation2011; Okuboyejo & Eyesan, Citation2014; Tsehay, Citation2014). This has created a knowledge gap, resulting in poor health habits and limited access to appropriate healthcare treatments (Derman & Jaeger, Citation2018; Ezema, Citation2016; Sokey et al., Citation2018; Steinf & Zapletalov, Citation2016).

Rural towns in Ghana rely mostly on traditional methods of information dissemination such as face-to-face contacts, town meetings, and infrequent visits by health practitioners (Arthur et al., Citation2019; Sokey et al., Citation2018). These methods have some limits, such as their reach, and they frequently result in the propagation of incomplete and incorrect information (Andualem et al., Citation2013; Ilo et al., Citation2021; Mtega & Benard, Citation2013). Most persons especially women in rural communities are either illiterates or semi-literates and therefore presents a crucial avenue to ascertain the efficacy of the available health information dissemination methods available in these areas towards addressing their information needs (Kankam, Citation2018). Market women in Ghana are found to be confronted with many health challenges such as body pains, stress, among others and therefore need health information (Adjokatse et al., Citation2022). It is therefore important to investigate how health information dissemination methods can be improved to enhance the reach and availability of reliable health information to these market women. The purpose of this study was achieved through the following objectives:

Ascertaining the health information needs of market women in rural communities

Investigating the health information dissemination methods available to market women in rural communities

Looking into how health information dissemination methods available to market women could be improved

Literature review

Health information needs of women in rural communities

Women in rural communities are considered as active participants in economic and social progress, as well as environmental protection in various ways. These women seek a variety of health information due to their various activities. For example, their reproductive information needs have been identified. In their study, Ilo and Adeyemi (Citation2010) discovered that market women rural communities within the Ogun State, Nigeria, were concerned about the negative implications of sexually transmitted illnesses. They discovered that persons with limited awareness and knowledge of such information were more likely to face the negative outcomes of such disorders. Ngwenya (Citation2016) went on to say that women in rural communities in Zimbabwe needed health information about diseases like tuberculosis, prostate and cervical cancer, HIV/AIDS, and diarrhoea. Similarly, Coraggio (Citation2010) stated that in poor countries, women’s primary health information needs in Uganda range from reproductive needs to birth control, but that such needs were not met due to insufficient access to information and facilities. Similar demands were discovered among women in Nuskka, Southeast Nigeria, by Ezema (Citation2016), who discovered that their health information needs were primarily regarding fertility, abortion concerns, sexually transmitted infections, female genital mutilation, and rape.

In the Ghanaian context, women in rural communities also have their health information needs (Amu et al., Citation2018; Arthur et al., Citation2019; Sokey et al., Citation2018; Sokey & Adisah-Atta, Citation2017). They appear to require information on reproductive health, which includes family planning, delivery, and good menstruation practices. More crucially, women in Ghana required information on how to prevent and treat common urban ailments such as malaria, diarrhoea, and other infections. The knowledge required included how to recognize the signs, preventive mechanisms, and self-care strategies. Furthermore, Amu et al. (Citation2018) discovered that women in Ghana and other African nations require information on health screenings and preventive treatments. They also stated that increasing women’s awareness of such programs leads to earlier identification and improved health outcomes. Arthur et al. (Citation2019) discovered that women in the Sagnerigu District of Northern Ghana required health information on family planning and nutrition in their daily lives.

Health information dissemination methods available to market women in rural areas

The World Health Organization defined dissemination of health information as knowledge translation where the knowledge translation is:

a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen healthcare systems (Straus et al., Citation2011, p. 6).

There are two primary sources of health information: interpersonal and mass media. Interpersonal sources include close relationships such as family and friends, as well as health professionals, whereas mass media sources include radio, television, posters, newspapers, and the internet (Asfaw et al., Citation2019; Liu & Jiang, Citation2021). Traditional mass media means of information dissemination such as radio and television are common among rural populations (Ifukor & Omogo, Citation2013; Kankam & Attuh, Citation2022). Once again, the marketplace serves as a mechanism of disseminating information to rural people. Most women in rural communities can be located in markets, making it an efficient site to communicate information to them. As a result, the African market has been considered as a location for successful information diffusion.

Clearly, radios, television, and other devices are utilized to disseminate health information to rural settlements (Attuh & Kankam, Citation2022). Community-based health awareness events have been identified as an effective technique of disseminating health information to rural market women. According to Ekoko (Citation2020) and Odini (Citation2016), the organization of these programs in collaboration with community leaders, health practitioners, and NGOs can assist market women in gaining accurate and valuable insights into some health issues and questions they may have. Peer education and mentoring, once again, are excellent strategies of disseminating health knowledge.

Access to electronic information is a significant difficulty in rural locations due to inconsistent power supplies. To make matters worse, internet connectivity is limited, and access to smart gadgets is difficult to many persons in remote areas of developing countries due to the low income of the residents (Afful & Boateng, Citation2023). Okuboyejo and Eyesan (Citation2014) emphasized this issue by revealing that, due to socio-cultural issues, women are mostly restricted from access centers such as internet cafes or information centers that are mostly known to be for men, thereby inhibiting their access to knowledge and information. According to Alumanah (Citation2005), women in Africa lack financial autonomy, making it impossible to obtain radios, computers, or internet services.

Improving health information dissemination methods

It is critical to strengthen existing health information dissemination methods so that there is always effective contact and communication with rural settlers. Such advancements can help to reduce some of the barriers that prevent rural residents from accessing health information. Some suggestions include the usage of multimedia tools. The use of multimedia means will help improve the dissemination approach, since there will be an option to use local dialect to convey part of the health information for people to better understand it (Korda & Itani, Citation2013).

Again, community influencers can boost dissemination tactics because they are well-respected and will be listened to when they present health facts to them (Tutu et al., Citation2023). According to Kumar and Preetha (Citation2012), collaboration with local health practitioners can assist improve the accuracy and relevance of health information given to communities. Thus, through efficient communication, the government and NGOs may link with local practitioners to ensure they are sent out to communicate health information to the locals. Furthermore, using smartphone technology to better health information dissemination is essential (Sokey et al., Citation2018; Sokey & Adisah-Atta, Citation2017). Pushing for this gadget in rural areas can assist them have access to timely and accurate information via the phone’s various applications. Furthermore, women’s health support groups can aid in the successful dissemination of health information by serving as a venue for market women to discuss their experiences and solicit information.

Theoretical framework

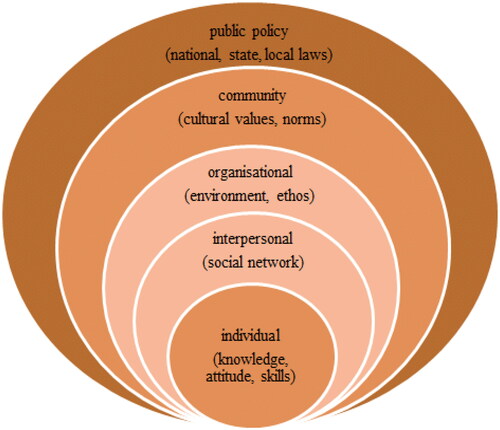

The Social Ecological Model (SEM) was used as the theoretical foundation for this study. As seen in , the Social Ecological Model recognizes the interplay of individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policies in affecting health behaviours (Brown, Citation2015). It focuses on changing behaviours through the influence of several levels, and targeting each level specifically resulting in optimal levels of efficacy (Trego & Wilson, Citation2021). The individual level is concerned with the individual’s knowledge and abilities. The more an individual knows about something, the more likely they are to understand it, and the more informed they are about their vulnerability, the seriousness, and the threats posed by the thing.

In terms of health information, they learn about various health hazards and help impact their attitudes and decisions. It is concerned with people’s interpersonal interactions, such as those with family and friends. At this level, it is seen that interactions between relations might influence choices and understanding regarding health information. People are brought into contact with organizations such as schools, workplaces, NGOs, and others at the organizational level to educate them on health-related issues. The concept defines the community level as the coming together of various organizations in the community to collaborate and pool resources to improve community healthcare through events, programs, and other outreach approaches. The fourth level, public policy, refers to the governing entities in authority who are in charge of developing effective solutions to health-related concerns. This is where the government can make and enforce laws. Recognizing the various levels of influence, the Social Ecological Model provides a comprehensive approach to health information dissemination by recognizing that through the combined efforts of individuals and governments, health information dissemination can be properly targeted for maximum success and find leverage points for interventions and the development of strategies to address barriers and encourage supportive arenas for behavioural change.

Methodology

Design

To investigate the phenomenon, the study used the qualitative approach to research and the interpretivist research paradigm. The use of interpretivism in this study’s design emphasized the importance of understanding market women’s experiences with health information, both individually and collectively, including how they use, feel, think, distribute, and receive it (Kankam, Citation2020). On the other hand, the study had the opportunity to conduct an in-depth investigation of the many components of health information dissemination from the perspectives of the market women in rural areas thanks to the qualitative research approach.

Population and sampling

The study was conducted in the Keta Municipality of Ghana’s Volta Region. The municipality was chosen because of the abundance of rural settlements inside its enclave and because the area has a mostly agrarian economy, with the bulk of the inhabitants involved in crop farming and other associated business and trade (KeMA, Citation2022). Three rural community markets within the Keta Municipality were selected for the study: Anlogasi me (Anloga market), Ketasi me (Keta market) and Kpotasi me (Kpota market). These rural community markets were chosen because they were the major markets that served most of the rural communities within the Keta Municipality. For example the Anlogasi me serves Salo, Anyanui, Dzita, Konu communities; the Ketasi me serves Azizadzi, Kedzi, Xorvi, Vodza communities; and the Kpotasi me serves Weta, Kpornukope, Atiteti, Awalawi communities.

The population of the study therefore consisted of market women in these three rural markets and public health professionals of the Keta Municipal Health Directorate. It was difficult in ascertaining the total number of market women in the three communities. This stem from lack of proper records on the market women in the three rural markets. The study was interested in employing associations within the markets for the sampling but it was also difficult since most of these groupings were not coherent enough. The fish sellers’ associations such as the Baby Akwetey, National Fish Processors and Traders Association, Kokui Seshi and Susu groups had fair structures but their numbers alone could not be employed towards a true reflection of the women in the three markets. The study employed both purposive sampling and convenience sampling for the selection of participants. The head of the Health Promotion Division of the Health Directorate was purposively selected for the study due to her expertise and involvement in health information dissemination. The head recommended one of her colleagues in the Health Promotion Division responsible for Nutrition to be included in the study since she was highly involved in health dissemination efforts in the markets. Hence, the study employed purposive sampling technique for the selection of the health professionals. On the other hand, the Convenience sampling was employed to select the market women from the three markets as this technique aims at selecting participants who were willing as well as available for a study and it serves as an effective sampling technique to choose participants to undertake a study quickly and efficiently (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2009). In the three selected marketplaces, 28 market women expressed interest for the interviews bringing the total sample size for the study to 30 participants (28 market women plus two health professionals). After the application of the eligibility requirements, 22 of the women qualified. The primary requirements for eligibility were to be a female trader in one of the chosen marketplaces and to have traded there continuously for the previous two years. The eligible participants were therefore organized according to the times and dates on which they indicated an interest in the various marketplaces for the interviews. After interviewing twelve of the market women, the following three interviews yielded information that was identical (saturation); and based on the theory of saturation, the remaining seven market women were notified that they would be contacted in the future, if necessary, thus, 15 market women participated in the interviews for the study (see Appendix 1 for the profile of participants). A qualitative research stage known as saturation happens when no new information is obtained from the data and the same discoveries keep coming to light throughout the data analysis process, alerting researchers that it may be time to stop gathering data (Kankam & Baffour, Citation2023). Five of the remaining seven rural market women were later contacted and employed for a focus group discussion (see appendix 2 for their profile).

Data collection and analysis

Participants’ information for the study was gathered through the use of a semi-structured interview guide. While the interviews with the health professionals were done in their offices, those with the market women were performed at their marketplaces (13 women) and at the residences of the participants (2 women). The duration of each market woman’s interview ranged from 30 to 45 minutes, whereas the interviews with the health professionals took 48 to 1 hour and 12 minutes. The interviews with the health professionals were conducted in the English language while an interpreter was employed and trained to assist in the interviews with the market women. The study was conscious of reflexivity in order to avoid biases. Thus, the study ensured credibility and reliability through member checking, participant triangulation, and reflexivity. The thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data from the interviews in connection to the study’s objectives after being recorded, transcribed, and summarised. The participants were asked to discuss among other things the health information needs of market women, the preferred and available health information dissemination methods for the market women as well as ways to improve health information dissemination to market women. Through the use of thematic analysis, themes were defined and relationships between the themes were outlined (Saunders et al., Citation2019). In order to have a comprehensive understanding of the contents and to become familiar with the data that had been transcribed for the thematic analysis, codes were created to help identify and attribute meaning to the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The codes were examined to identify reoccurring ideas that were pertinent to the study’s objectives, and these ideas served as the foundation for generating the themes (Braun et al., Citation2023). The themes were found, defined, and given names to indicate their significance before being analysed and interpreted. Direct quotations were used in the presentation of the study’s findings to share the perspectives and experiences of the participants.

Results

Seven themes emerged () from the thematic analysis of data received from the participants. Fifteen market women in all were interviewed with 9 (60%) having five or more years being in the market. The remaining six market women had been trading in the market for a period between three and five years. The coding for the participants were done from P1 to P17 to include the two health professionals (See Appendix).

Table 1. Themes generated through thematic analysis from the responses of the participants.

Health information needs of rural market women

To ensure efficient ways of health information dissemination to address health needs, it is envisaged that health information needs will be identified. This purpose set out to determine the health information that market women in the rural communities needed. The analysis of the data revealed two key areas of significance, focusing on the need and frequency of access to health information as well as its motivations.

Health information needs and frequency

The data analysis revealed that rural market women favour health information that was tailored to their own requirements. The findings from the research showed that market women in the rural communities preferred health information on diet, personal cleanliness, as well as relaxation and sleep.

My health information needs are personal hygiene, food nutrition, rest and sleep. I need information on these because I have to take care of myself to preserve my health, and I have to pay attention to what I eat as well as understand issues around rest and sleep so that I can always stay healthy (P10, 41yrs stated)

However, when asked how often they look for this health information, the results show that they do these rather irregularly.

Even though I appreciate the importance of health information, I do not seek for them regularly. I cannot remember the last time I did that, and as a result, I cannot say that it is something I spend time to do (P1, 35yrs indicated).

It was not surprising that during the focus group discussions, participants highlighted their physical health as the main aspect of their health information needs

Reasons for access to health information

The study also aimed to identify the health-related concerns that led the market women to look for health information. Additionally, it aimed to discover if participants’ searches for health information are driven primarily by their own needs or also by a desire to gather the knowledge necessary to address the needs of others. According to the analysed data of the study, the market women sought for health information on, among other things, body aches and headaches. Additionally, they search for medical information to fulfil both their own and their families’ personal health needs.

Because of the nature of work we do, we are mostly faced with health challenges like head ache and body pains. These are the reasons that I mostly seek for health information so that I can deal with these very regular health-related issues (P5, 30yrs said).

Yes, I do search for information for my personal health needs. But also, I do for the welfare of my family too. Because if I am healthy and my family is not, then there is a problem. So I also search for information for the betterment of my family (P1, 35yrs said).

I look for health information for myself and my family. I do this because I don’t want to benefit alone from the information I receive (P10, 41yrs stated).

Health information dissemination methods available to the market women

The ways in which information is disseminated and the language that is used to do so might affect whether or not the intended health results are successful. The correct route, the right contacts, and the right language must be used in order for the market women in the rural communities to comprehend and appreciate the efforts being made to address their health needs. The purpose of this objective was to identify the channels or techniques that can be used to disseminate health information. The sources of access to health information, the visits of public health workers seeking health information, and the preferred language and media in addressing health needs were three subthemes that arose during the data analysis.

Sources of access to health information

In the course of the interviews, participants were asked to outline the source(s) and method(s) they used to access health information and the sources they mentioned included hospitals, health professionals, etc.; mass media (radio, TV, newspapers, etc.); the internet (Google via smart phones or social media, etc.); family and friends; and posters and billboards. Because of its usability in the context of their working environment, the analysis revealed that the majority of participants relied on the mass media, such as radio, television, and newspapers to satisfy their health information needs.

Because of where we work, radio is the easiest means of access to information and so, anytime I come to work, I tune into radio and use that to obtain every information I need (P7, 39yrs said).

As for me, I use radio when I am at work. But, when I go home, I spend time watching the television. So, I use these two means to access health information. Sometimes too, when I am available and around town, I use the Community Information Service to obtain information on health (P2, 19yrs opined).

Another source of health information that was revealed through the focus group discussions was the drugstore (pharmacy): Me, I run to the drugstore when I am not feeling well to find out what is happening to me and what to do to solve the problem…they are always there for me with medicine or advice.

The study sought from the health professionals who were included in the study the medium used in disseminating health information to the market women in the area. The results showed that they used two main channels at their level which were radio and the Community Information Centre.

We first tried to appreciate the medium that directly could help us reach our target audience. With our market women specifically, aside sometimes going to them, we use the radio stations that they listen to, as well as the Community Information Centre to broadcast to them (P17, 48yrs provided)

Visitation of public health workers for dissemination of health information and health education

The study also tried to find out from the participants whether or not public health workers personally approached market women to engage them in conversation about health issues due to the rural nature of the study area and appreciation of the value of interpersonal communication. According to the responses, public health experts do occasionally go to the markets, especially when there is a communicable disease outbreak, to inform the market women about the best ways to prevent illnesses.

Yes, they come here from time to time, but not quite often. They do come especially when there is an outbreak of a disease. For instance, when Covid-19 came, they were here to educate us, and to teach us what to do to avoid contamination. They taught us the preventive measures and we really were guided appropriately (P6, 45 yrs added).

We go to the community to educate them. We set out to educate them on issues of communicable diseases. We educate them on cholera, diarrhoea among others. For instance, during the Covid-19 days, we went to the market to teach the market women on the preventive measures in order to contain the spread. After that, we have been educating them on other health issues in order to keep them healthy (P16, 38yrs provided).

Preferred language and media in meeting health information needs

Language and communication medium selection go hand in hand. The goal of communication, and by extension the dissemination of health information, is impacted if the media used has a language barrier. It is simpler to accomplish the communication goals when the appropriate channel is chosen and utilised, along with a language that the recipients value and comprehend. The analysed data from the study showed that, although the English language is occasionally utilized, it is only used for words that the officials are unable to articulate properly in the Ewe language. According to the findings, the Ewe language is the most frequently utilized language for health information dissemination to the market women. The study also found that rural market women preferred radio, face-to-face interactions, and using the church as a source of health information. The participants confirmed this.

Because we work within an Ewe community, we always use the Ewe language to communicate and disseminate health information. That is the only way we can be sure that we are making an impact. Even though we sometimes use the English language, we only use it to refer to things that we do not have the direct expression for in the Ewe language. For instance, we don’t know the Ewe name for cholera, so we mention it in English…we just explain it in Ewe that you will be passing watery stool (afodzi dede). So we use Ewe to explain most of the things for them. We sometimes use two languages in terms of mentioning some of the things which are not in Ewe (P17, 48yrs indicated).

We prefer to receive health information on radio and in the Ewe language. Like I said earlier, because of the work we do, the best and easily accessible channel of information to us is radio. And I want my health information in Ewe also because that is the language I speak well and understand as well (P7, 39 yrs indicated).

I prefer to receive health information on the radio and at church. In addition, I prefer the Ewe language as the language of communicating health information in this area because that is our language (P5, 30yrs added).

Improving health information dissemination methods for market women

In order to achieve successful outcomes in health delivery and healthy living, it is crucial to recognize and address the problems that are faced in the dissemination of health information. It is crucial to identify the obstacles that can prevent the efficient dissemination of health information in order to strive to improve them and ensure the quality of the information, especially given the rural nature of the study’s female participants. The study identified issues with accessing and disseminating healthcare information, as well as how to improve it, as subthemes.

Challenges in accessing health information

The study identified the attitude of health professionals as a barrier to accessing health information. According to the analysed data, certain health officials’ behaviour made it difficult for market women to access information about the public’s health. The data analysed from public health professionals also worries about their difficulty to have the entire concentration of the market women whenever they go to the market to engage them as part of their difficulties in disseminating health information. The analysed data from the interviews with the health professionals showed that rather of listening to health information from the public health officers when they visit the markets, the focus of the market women had always been on how to maximize sales.

The attitude of health workers greatly impacts our access to health information. Sometimes, when you ask them something, they frown. At other times, when you approach them, they give you attitude that makes you feel they are not interested in engaging you (P6, 45yrs said).

There are times you go to the market to talk to them. You are ready to talk to them like one-on-one…but because they are selling it becomes difficult to have their full concentration. So they focus on the things they are selling to their clients than to give you full attention (P17, 48yrs added).

The participants in the focus group discussion revealed that the nature of their work did not enable them to frequently look for health information due to time constraints: Honestly, to look for health information…I don’t…no, because of work…we don’t, I don’t do it unless I am sick.

Improving health information dissemination

In order to achieve health goals, it is crucial to improve the manner and language in which health information is communicated. To guarantee a successful conclusion, it is critical to make sure that all the components of the information dissemination process work in harmony with one another. The study discovered the need for opinion leaders in the regions to support the information dissemination goals as a means of enhancing the spread of health information. According to the study, it would be very beneficial to involve Market Queens and Assemblymen and/or women in the effort to disseminate information. According to the participants, these are influential individuals in the communities within which the markets operate.

We have to plan with the Queen mother, Market Queens and the Assembly man or woman in the area before we can have that support. When you go alone, it doesn’t come easy. But if those people are around and you are going together, you can easily get them to speak to them. Because they respect these people and know that they depend on them to run an effective market, they will always rely on their directives to engage with us (P17, 48yrs provided).

Discussion

People’s access to the right, reliable, and essential information to make sound health decisions is at the heart of health information needs. Based on the individual and community levels of the SEM, it was evident that different groups of individuals require different types of health information, and in this case, the focus was on market women in the rural communities. According to the findings of the study, market women have distinct health information needs around personal hygiene, diet, and illness such as body pains and headaches. These areas are seen as critical to their general health and well-being which clearly aligns with the individual element of the SEM. This research supports the findings of Amu et al. (Citation2018), Arthur et al. (Citation2019), Sokey et al. (Citation2018), and Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017). They discovered that women in rural communities’ health information needs are manifested in their desire for knowledge on personal hygiene practices and healthy eating habits. It was discovered that they are highly particular about other hygiene habits information that might assist them in preventing epidemics of malaria, diarrhoea, and other diseases. Arthur et al. (Citation2019) confirmed the findings, revealing that women in Northern Ghana’s Sagnerigu District required health information on nutrition in their daily lives. However, the frequency with which the market women obtain health information appears to be irregular among the participants. They recognised the value of health information, but they did not actively seek it on a regular basis. This finding is consistent with Kinkor et al. (Citation2019), who discovered that Indian women in rural communities irregularly seek health information due to their lack of understanding about the negative implications of their health conditions.

Access to health information must have a purpose and diverse persons have diverse health information demands since information needs vary in nature. According to the analysed data, the market women in the rural communities sought health information largely to manage common health conditions such as bodily pains and headaches. They seemed to be looking for knowledge to help them manage and prevent these health issues. Furthermore, their search for health information was motivated by a desire to address both their own and their family’ health needs. They understand the importance of being healthy as individuals and as family caregivers. Amu et al. (Citation2018), Arthur et al. (Citation2019), Sokey et al. (Citation2018), and Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017) all found similar results. According to their findings, women seek health information to learn how to prevent and manage health conditions. Amu et al. (Citation2018) confirmed that women in rural communities wanted health information on health screenings and preventative services because they considered them as good avenues to help them detect and improve their own and their families’ well-being.

The communication route is critical for access to health information. Different channels will be successful depending on one’s society, educational status, and occupation. The study also looked into the channels or methods available for disseminating health information to the market women. Based on the analysed data, the channels employed by health facilities and public health authorities to disseminate health information to the public included mass media (radio, television, newspapers), internet, face-to face conversations, and posters or billboards. Among these, mass media, particularly radio, was often utilised by the participants due to its ease of access and reach inside. The health professionals also highlighted market visits, particularly during communicable disease outbreaks as one of the effective means of disseminating health information to the market women. Though the use of the SEM as the theoretical foundation of this study, it was revealed that the combined efforts of individuals and organisations both public and private significantly contribute to market women’s access to health information and help in leveraging avenues for interventions and the development of targeted health information dissemination efforts. These findings corroborate those of Asfaw et al. (Citation2019) and Liu and Jiang (Citation2021) whose study highlighted that health information is usually disseminated through interpersonal channels such as family and friends, as well as through mass media such as radio, television, posters, newspapers, and the internet. Ilo et al. (Citation2021), Sokey et al. (Citation2018), and Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017) all reported on the usage of radios, television, and smartphones to disseminate health information to rural settlers. In line with the findings of this study, Nwagwu and Ajama (Citation2011) also found that health practitioners are important sources of health information for rural women because, via their volunteer work and services, they may reach out to them and make them aware of the need for health information. In terms of radio being the preferred medium for spreading health information, findings from Arthur et al. (Citation2019), Sokey et al. (Citation2018), and Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017) all agreed that it was quite effective in reaching out to them. Similar findings were found in other parts of Africa. Tsehay (Citation2014) reported that rural Ethiopians accessed health information through health workers, whereas Ifukor and Omogo (Citation2013) claimed that Nigerians accessed health information through television, radio, and newspapers.

Language is one of the most significant barriers to getting health information. When information is presented in a language that you cannot understand or apply, it is as if you do not have the information at all. As a result, it was vital for the study to ascertain participants’ preferred language for health information, and the participants expressed a preference for obtaining health information in Ewe, as it was their native language and allowed for better comprehension. Although English was occasionally used especially for terms that did not have exact translations in Ewe, the majority of health communication were done in Ewe. Radio was likewise highlighted as the top medium for accessing health information by participants, followed by face-to-face encounters and church-based dissemination. The findings are in line with findings of Andualem et al. (Citation2013), Déglise et al. (Citation2012), Momodu (Citation2002), Mtega and Benard (Citation2013) and Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017) as they revealed that the rural women preferred health information in their local language which they can truly understand and hence, their preference for the radio as the main medium for health information as they have sessions where the information will be delivered in their local language.

The study also found access to health information challenges as outlined by the participants, particularly due to attitudes and the limited attention market women can give due to their sales concentration. These findings are consistent with those of Andualem et al. (Citation2013), Déglise et al. (Citation2012), and Mtega and Benard (Citation2013), who discovered that poor timing of messages sent to women in rural areas made it difficult for them to gain access or truly reach them because they were engaged in their primary activities. It is advocated that influential people such as Market Queens and Assembly members participate in increasing health information dissemination. By using their power and influence within the community, these individuals can help to support and improve the information dissemination process. The findings of Kumar and Preetha (Citation2012) were related to the findings of this study since they said that the government and NGOs, through their influence and cooperation, can go a long way toward assisting with the successful dissemination of health information to rural populations. Sokey and Adisah-Atta (Citation2017) also urged for the development of individual support groups to aid in the effective dissemination of health information. Again, in line with the findings of this study, Ekoko (Citation2020) and Odini (Citation2016) revealed that the organisation of these programmes together with community leaders and NGOs can help the market women gain accurate and valuable insights in some health issues.

Conclusion

This study on market women’s health information needs gives vital insights into their preferences, behaviours, and obstacles in receiving and disseminating health information. It was discovered that the market women’s health information demands were unique to them, as seen by their search for information on personal hygiene, diet, and illness. They also recognized the importance of self-care. However, it was discovered that, despite their importance, they did not seek such information on a regular basis; thus, there is a need for targeted reach to persuade them to seek such information on a regular basis.

The market women in the selected rural communities primarily sought health information to address common health issues such as headaches and body pains, as well as the health needs of their families, and the preferred channels included mass media, and interpersonal interactions, with radio being the most preferred medium due to its reach within their settings. They like to get health information in their native language so that they can grasp it. Impediments to the dissemination of health information as found in the study included health practitioners’ attitudes and market women’s limited attention as a result of their marketing activity and to enhance these, involving influential figure heads in the community can help make health information reach effective.

Implications for practice

This study has various implications for healthcare providers, legislators, and health information distribution organizations. It has been established in the study that targeted health information dissemination is crucial to help reach market women in rural communities. Healthcare providers and organizations must therefore identify the specific health information needs of rural market women, such as hygiene, nutrition, among others, and tailor health information dissemination to address these unique needs. This would increasing the importance and effectiveness of the information dissemination efforts to market women. Again, it is important to help market women recognise the benefits of regular or constant access to health information. The research found that rural market women do not actively seek out health information on a regular basis, highlighting the need for policies to be put in place to help incentivize or encourage them to do so.

Initiatives such as health campaigns, reminders, and follow-ups can be implemented to assist the frequent dissemination of pertinent health information to the market women. In addition, the market women must be empowered to care for themselves through seeking of health information. With the study indicating that the market women sought health information to care for themselves and their families, it is critical that they are equipped with the knowledge and skills to engage in self-care and self-help information seeking. They will be empowered by the dissemination of practical information and materials to address common occurring health problems such as body pains and headaches caused mostly by their employment and advocate for healthier well-being when these are prioritised. Furthermore, it has been shown that the market women employed radio as their most preferred means of access to health information, hence it is critical that this medium be exploited.

Healthcare professionals and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) must collaborate with local radio stations to deliver particular and targeted health information in the native language of the participants. Furthermore, community engagement has been shown to be beneficial, therefore the government, hospitals, NGOs, and organizations, among others, must enlist significant community leaders such as Market Queens, as well as Assembly members, to aid in the successful dissemination of health information. Because the participants trust these people, health information can reach them more effectively because they will listen to them. Finally, there is a need to address healthcare providers’ attitudes through trainings so that they can appropriately engage with market women in rural communities, as well as measures to utilize to grab their attention when selling their products.

Recommendations for further studies

The study has limitations because it only looked at the occurrence in one municipality; nevertheless, looking at the phenomenon across the entire country will involve more individuals and give a greater grasp of the topics under investigation. Further studies are recommended to investigate the problems in other rural communities when funding and other resources are available. When funding is secured, the use of mixed-methods to investigate the phenomenon across the country would be highly beneficial. These studies should look at additional health information dissemination strategies and their efficacy, as well as rural market women’s viewpoints on the obstacles to and enablers of access to and utilization of health information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Philip Kwaku Kankam

Philip Kwaku Kankam is an information professional with several years of experience in librarianship and information studies. The holds a PhD in information studies from the University of KwaZulu Natal as well as BA and MA degrees in information studies from the University of Ghana. He is currently a Senior Lecturer at the department of information Studies, university of Ghana.

Emmanuel Adjei

Emmanuel Adjei (Ph.D) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Studies, University of Ghana, Legon. He has several years of experience in the field of information studies and has published widely in areas such as health records management, management of information resources, health information systems, among others.

DeGraft Johnson Dei

De-Graft Johnson Dei holds a Ph.D. in Information Science from the University of South Africa (UNISA), a Master’s and Bachelor’s Degree in Information Studies from the University of Ghana, and a Postgraduate Diploma in Business Information Systems. He is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Information and Communication Studies, University of Ghana, Legon; and consulting Librarian at KAAF University, Ghana.

References

- Adjokatse, I. T., Oduro-Okyireh, T., & Manford, M. (2022). Health problems associated with market women in closed and open space market areas. African Journal of Applied Research, 8(1), 1–15.

- Afful, D., & Boateng, J. K. (2023). Mobile learning behaviour of University students in Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2204712

- Alumanah, J. N. E. (2005). Access and use of information and communication technology for the African girl-child under cultural impediments. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Women and ICT: Creating Global Transformation, 13–es. https://doi.org/10.1145/1117417.1117430

- Amu, H., Dickson, K. S., Kumi-Kyereme, A., & Darteh, E. K. M. (2018). Understanding variations in health insurance coverage in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. PloS One, 13(8), e0201833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201833

- Amu, N. J. (2005). The role of women in Ghana’s economy. Friedrich Ebert Foundation Accra.

- Andualem, M., Kebede, G., & Kumie, A. (2013). Information needs and seeking behaviour among health professionals working at public hospital and health centres in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 534. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-534

- Arthur, B., Dukper, K. B., & Sakibu, B. (2019). Information needs and access among women in Sagnerigu District of Northern Region, Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–15.

- Asfaw, S., Morankar, S., Abera, M., Mamo, A., Abebe, L., Bergen, N., Kulkarni, M. A., & Labonté, R. (2019). Talking health: trusted health messengers and effective ways of delivering health messages for rural mothers in Southwest Ethiopia. Archives of Public Health = Archives Belges de Sante Publique, 77(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-019-0334-4

- Ashcroft, K., & Rayner, P. (2011). Higher education in development: Lessons from sub Saharan Africa. IAP.

- Attuh, S., & Kankam, P. K. (2022). Community radio as information dissemination tool for sustainable rural development in Ghana. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529.2022.2146119

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., Davey, L., & Jenkinson, E. (2023). Doing reflexive thematic analysis. In Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research (pp. 19–38). Springer International Publishing.

- Braun, V., &Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, V. (2015). Using the social ecological model to inform community needs assessments. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 107(1), 45–51.

- Chibbonta, D., & Chishimba, H. (2023). Effects of microfinance services on the livelihoods or marketeers in Zambia: A case of Matero Market in Lusaka. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2266922

- Coraggio, F. (2010). Women’s information needs in developing countries. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/fcoraggio/information-needs-of-women-in-developing-countries.

- Déglise, C., Suggs, L. S., & Odermatt, P. (2012). SMS for disease control in developing countries: A systematic review of mobile health applications. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 18(5), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2012.110810

- Derman, R. J., & Jaeger, F. J. (2018). Overcoming challenges to dissemination and implementation of research findings in under-resourced countries. Reproductive Health, 15(Suppl 1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0538-z

- Ekoko, O. N. (2020). An assessment of health information literacy among rural women in Delta State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 2020, 1–14.

- Ezema, I. J. (2016). Reproductive health information needs and access among rural women in Nigeria: A study of Nsukka Zone in Enugu State. The African Journal of Information and Communication, 2016(18), 117–133.

- Fauzi, F., Antoni, D., & Suwarni, E. (2020). Women entrepreneurship in the developing country: The effects of financial and digital literacy on SMEs’ growth. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 9(4), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgrv9i4art9

- Gallardo-Echenique, E. E., de Oliveira, J. M., Marqués-Molias, L., Esteve-Mon, F., Wang, Y., & Baker, R. (2015). Digital competence in the knowledge society. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 11(1).

- Garcia, A. C., Standlee, A. I., Bechkoff, J., & Cui, Y. (2009). Ethnographic approaches to the internet and computer-mediated communication. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 38(1), 52–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241607310839

- Ifukor, M O., & Omogo, M. (2013). Channels of information acquisition and dissemination among rural dwellers. International Journal of Library and Information Science, 5(10), 306–312.

- Ilo, P. I., & Adeyemi, A. (2010). HIV/AIDS information awareness among market women: A study of Olofimuyin Market, Sango-Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice.

- Ilo, P., Ifijeh, G., Segun-Adeniran, C., Michael-Onuoha, H. C., & Ekwueme, L. (2021). Providing reproductive health information to rural women: The potentials of public libraries. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 25(s5), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i5s.19

- Kankam, P. K. (2018). Evaluation of Internet information sources by high school students in Ghana. International Information & Library Review, 50(2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2017.1366201

- Kankam, P. K. (2020). Mobile information behaviour of sandwich students towards mobile learning integration at the University of Ghana. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1796202

- Kankam, P. K., & Attuh, S. (2022). The role of community radio in information dissemination towards youth development in Ghana. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-01-2022-0023

- Kankam, P. K., &Baffour, F. D. (2023). Information behaviour of prison inmates in Ghana. Information Development, 02666669231178661.

- KeMA. (2022). About Keta Municipal Assembly. Retrieved from https://ketama.gov.gh/about-us/

- Kinkor, M. A., Padhi, B. K., Panigrahi, P., & Baker, K. K. (2019). Frequency and determinants of health care utilization for symptomatic reproductive tract infections in rural Indian women: A cross-sectional study. PloS One, 14(12), e0225687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225687

- Korda, H., & Itani, Z. (2013). Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promotion Practice, 14(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839911405850

- Kotter, J. P., & Cohen, D. S. (2012). The heart of change: Real-life stories of how people change their organizations. Harvard Business Press.

- Kumar, S., & Preetha, G. S. (2012). Health promotion: An effective tool for global health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 37(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.94009

- Liu, P. L., & Jiang, S. (2021). Patient-centered communication mediates the relationship between health information acquisition and patient trust in physicians: A five-year comparison in China. Health Communication, 36(2), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1673948

- Momodu, M. O. (2002). Information needs and information seeking behaviour of rural dwellers in Nigeria: a case study of Ekpoma in Esan West local government area of Edo State, Nigeria. Library Review, 51(8), 406–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530210443145

- Mtega, W. P., & Benard, R. (2013). The state of rural information and communication services in Tanzania: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Research, 3(2), 64–73.

- Nargund, G. (2009). Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn, 1(3), 191–193.

- Ngwenya, S. (2016). Communication of reproductive health information to the rural girl child in Filabusi, Zimbabwe. African Health Sciences, 16(2), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v16i2.13

- Nwagwu, W. E., & Ajama, M. (2011). Women’s health information needs and information sources: A study of a rural oil palm business community in South-Western Nigeria. Annals of library and information studies, 58(5), 270–281.

- Odini, S. (2016). Accessibility and utilization of health information by rural women in Vihiga County, Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(7), 827–834.

- Ogunlela, Y. I., & Mukhtar, A. A. (2009). Gender issues in agriculture and rural development in Nigeria: The role of women. Humanity & Social Sciences Journal, 4(1), 19–30.

- Okuboyejo, S., & Eyesan, O. (2014). mHealth: using mobile technology to support healthcare. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics, 5(3), 233. https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v5i3.4865

- Owusu, C., & Kankam, P. K. (2020). Information seeking behaviour of beggars in Accra. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69(4/5), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-07-2019-0080

- Owusu-Achaw, J. K., & Kankam, P. K. (2021). The use of information dissemination to reflect altruism of Corporate social responsibility projects in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice: 6070.

- Parmar, V. (2010). Disseminating maternal health information to rural women: A user centered design framework. AMIA. Annual Symposium Proceedings. AMIA Symposium, 2010, 592–596.

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2009). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Shopova, T. (2014). Digital literacy of students and its improvement at the university. Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science, 7(2), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.7160/eriesj.2014.070201

- Sinha, E., & Bagarukayo, K. (2019). Online Education in Emerging Knowledge Economies: Exploring factors of motivation, de-motivation and potential facilitators; and studying the effects of demographic variables. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 15(2), 5–30.

- Sokey, P. P., & Adisah-Atta, I. (2017). Challenges confronting rural dwellers in accessing health information in Ghana: Shai Osudoku District in perspective. Social Sciences, 6(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020066

- Sokey, P. P., Adjei, E., & Ankrah, E. (2018). Media use for health information dissemination to rural communities by the Ghana Health Service. Journal of Information Science, Systems and Technology, 2(1), 1–18.

- Sørensen, K. (2018). Health literacy: A key attribute for urban settings. Optimizing Health Literacy for Improved Clinical Practices, 1–16.

- Steinf, A., & Zapletalov, J. (2016). The small town in rural areas as an underresearched type of settlement. Editors’ introduction to the special issue. European Countryside, 8(4), 322–332.

- Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J. M., & Graham, I. D. (2011). Knowledge translation is the use of knowledge in health care decision making. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.016

- Trego, L. L., & Wilson, C. (2021). A social ecological model for military women’s health. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 31 Suppl 1, S11–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.006

- Tsehay, A. B. (2014). Seeking health information in rural context: exploring sources of maternal health information in rural Ethiopia. The University of Bergen.

- Tutu, R. A., Ouassini, A., & Ottie-Boakye, D. (2023). Health literacy assessment of faith-based organisations in Accra, Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2207883. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2207883

- Yakong, V. N., Rush, K. L., Bassett-Smith, J., Bottorff, J. L., & Robinson, C. (2010). Women’s experiences of seeking reproductive health care in rural Ghana: Challenges for maternal health service utilization. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(11), 2431–2441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05404.x