Abstract

This research analyses and establishes linkages between the frequently disregarded economic theories that drive military spending. This paper’s analysis methodically goes over pertinent material, offering a thorough timeline that identifies significant moments that shaped the evolution of modern economic theories about military spending. Our analysis spans from the medieval period to the post-cold war times. Most of the analysis concentrates on conventional economic theories and their role in shaping military spending philosophies in Europe. We find that historical perspectives and theoretical underpinnings contribute to nuanced and informed debates, ensuring that the economic implications of defence investments are thoroughly understood. The ongoing discourse on military spending benefits from acknowledging the diverse roots and evolving theoretical perspectives, fostering a holistic understanding of the economic intricacies associated with defence expenditures, thus further emphasising the importance of this paper during such times.

A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defence than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.

― Martin Luther King Jr.

1. Introduction

In recent times, there has been a substantial amount of debate on whether government expenditures on military efforts are fruitful or futile. According to Owens et al. (Citation2019), world politics, or more precisely, international politics, is a fight for dominance between governments as each one tries to advance its own national interest. The balance of power is a system that governments use to prevent any one state from dominating, giving rise to the natural order that currently prevails in international affairs. Therefore, global politics revolves around negotiating and forging alliances, with diplomacy as a crucial tool for balancing divergent state interests. Despite using diplomacy as a crucial tool, the usage of military forces has been made effective for carrying out a state’s foreign policy, therefore making military expenditure a very critical part of a state’s budget.

Historically, states had amateurish militaries that comprised the working class, who, in times of need, would defend their nation from foreign invasions (Prak, Citation2015). Military spending was frequently justified as a vital tool for securing territorial expansion and safeguarding economic interests. The rise of mercantilism as the dominant economic philosophy in the sixteenth century, opposing medievalism to reconstruct a more rational, economic life emphasizing problems of money and public finance, led to a significant rise in military conflict between nation-states. Armies and navies were no longer temporary forces raised to address a specific threat or objective but were full-time professional forces. This resulted in the creation of permanent military forces for nations. As time passed, the economic debate over military spending grew to include ideas about defence as a stimulant to the economy in times of crisis. A paradigm change occurred in the post-Cold War era when military spending was more and more justified as a calculated investment in business and technology. An emerging economic theory of military spending is based on this historical trend, emphasizing how flexible it is to shifting geopolitical and economic environments. It is imperative to comprehend these changing economic viewpoints in order to fully appreciate the intricate relationship that exists between economics and military spending.

1.1. Research problem

The relationship between military expenditure and economic dynamics has long been a subject of interest, yet it has often been overlooked within traditional economic discourse. Despite the undeniable significance of the military sector in shaping national economies and international relations, mainstream economic theories have largely marginalized the role of military spending. This paper aims to fill this critical gap by shedding light on the economic implications of military expenditure and its ramifications on broader socio-economic indicators. By delving into the complexities of military spending from an economic standpoint, this study not only enriches our understanding of defence economics but also paves the way for integrating military considerations into mainstream economic models. This paper offers new avenues for economic thinkers to explore the multifaceted impacts of military spending, thus contributing to a more holistic understanding of economic dynamics in the context of defence and security.

1.2. Research objectives

This research aims:

To understand the viewpoints proposed by the economic schools of thought on military spending.

To emphasize the importance of military spending and critique the tendency of economic schools of thought to overlook this aspect, advocating for a more comprehensive approach to understanding its economic implications..

1.3. Research significance

This study highlights the economic importance of state budgetary allocations to the military by bridging the divide in political and economic thought governing military spending. Although political beliefs have shaped military spending paradigms, a thorough economic analysis has been conspicuously lacking. It emphasizes the prevailing effect of political philosophies, and aims to disentangle the paradigms that dictate military spending behaviour among states by utilising theories of economics. By bridging the political and economic divide, the study highlights the economic importance of state budgetary allocations to the military. The contribution of this paper is in two folds- one, this research is first of its kind to link the sparsely distributed line of thought on military spending throughout the economic schools and secondly, it critically analyses the schools of thought on ignoring to deliberate upon this topic.

2. Methodology

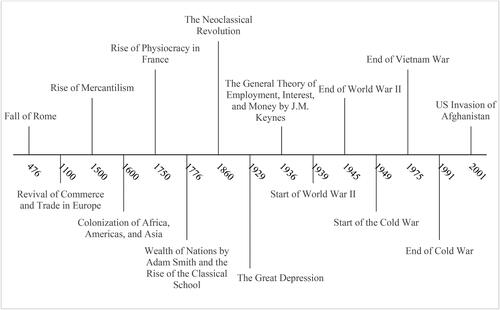

This research methodically analyses the development of economic ideas surrounding military spending through a thorough review of pertinent literature and the creation of a precise timeline emphasizing significant historical events. We emphasize the prevailing effect of political philosophies, aims to disentangle the paradigms that dictate military spending behaviours among states by utilising theories of economics. To make a focused argument, we choose Medieval Europe as the starting point of our analysis, and how the evolution of economic thought in the ‘West’ is pervasive in the way we look at modern military economic thought. To ensure a smooth chronological flow, we divide the period of analysis into four parts: we begin with the middle ages from the fall of Rome in 476 A.D to 1500; from 1500 to the early 1800s, we analyse the contributions of mercantilists and physiocrats and their influence on classical thought on military spending; from the 1800s to the mid-1900s, we analyse the orthodox paradigms of neo-classical and Keynesian economics and the role of military spending in those schools of thoughts; we end the analysis with heterodox schools in Marxists and Institutionalists, and modern empirical work related to military spending. To facilitate ease in understanding the chronology of events in our analysis, we construct a simple graph depicting the timeline of events ().

3. Analysis

3.1. Military expenditure through the middle ages

Europe descended into the dark ages after the fall of Rome in 476 A.D. It was only ten centuries later that trade and commerce re-emerged, rejuvenating Europe and parts of Africa. However, with the resurrection of nation-states came the growing need for advanced military capabilities. The training of disciplined infantry was a function of ancient Greek and Roman practices, which were rediscovered by soldiers and academics in Europe during the Renaissance (J. R. Hale, Citation1988). However, training and providing for soldiers require money and time (Barkawi, Citation2019). Nearly all European warfare during the Middle Ages can be explained by the incapacity of rulers to expand their economies and create essential administrative frameworks (Lacey, Citation2015). Because they lacked substantial financial resources, kings were never able to carry out war comparable to that of the ancients. European sovereigns therefore relied on the riches of the big towns to pay for these new armies through changes in tax policies. Disciplined armed forces were built up, expanding the sovereign’s domain. There was a creation of a positive feedback loop: more revenues meant larger areas could support troops and expand their conquest. The modern territorial state developed from this fiscal-military cycle (Baylis et al., Citation2020). However, kings in the late Middle Ages soon found that they need no longer rely only on what they could raise or coerce at home since creditors, with their sophisticated financing methods, might supply a stream of previously unexploited riches. Debt-ridden wartime endeavours were not unprecedented, but obtaining substantial sums of money from far-off international creditors was (Lacey, Citation2015). With the advent of advanced econometric tools, modern empirical literature has delved into this military spending-sovereign debt nexus (see for e.g. Dunne et al., Citation2019; Shahbaz et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2016) with the consensus being that higher military spending results in higher external debt. Dunne et al. (Citation2019) discovered that this effect of military spending on debt is even more pronounced in war-ridden countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, giving rise to policy discussions on how reducing war and military spending can reduce debt-burden in these countries.

The latter stages of the medieval period were intimately connected to the ‘crusades’ undertaken by European countries to propagate Christianity and flourish business ventures and trade (Robinson, Citation1900). The realization that nation states could maintain their military might at lower costs by expanding commerce and trade with other nations was the driving force of the mercantilist revolution, which was a by-product of these ‘crusades’. The British, the Dutch, the Spanish, the French, and the Portuguese started building immense colonial empires by conquering countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, leveraging their presence in these countries to expand their military might.

3.2. Mercantilists, physiocrats, and the classicals

The rise of mercantilism in the 16th century shifted the economic and political philosophy regarding war and military spending. Publicists at the time concurred that the state should be viewed as an economic entity with interests that should be furthered by trade, tariffs, and military action when the situation demanded it (Robinson, Citation1900). European nations used vast armies to colonize and plunder resource-rich countries of the East. According to Fontanel et al. (Citation2008), due to the emergence of permanent mercenary armies and new, expensive military methods, the financial requirements of European monarchs expanded significantly with the establishment of nation-states. The prevailing notion at the time was that the king’s authority depended on having access to enough financial resources, especially to wage war. In the late 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert in France and John Locke in England contended that the constitution of a significant war fund could guarantee the security of national riches and the capacity to control and threaten a rival state militarily (Fontanel et al., Citation2008). David Hume states that trade lowers the relative cost of war, improves military technical advancements, and fosters a spirit of combat. Therefore, commerce makes a nation’s military stronger and better able to defend itself against invaders (Paganelli & Schumacher, Citation2018). During the early 18th century, there was a very isolated shift in ideology in France, with the rise of the Physiocrats. We use the phrase ‘isolated’, but it is crucial to note that Physiocracy had a very powerful impact on the evolution of economics as a discipline separate from the political sciences. Physiocrats promoted laissez-faire economic principles, citing the productivity of agriculture as the main source of wealth and the significance of natural economic laws. They thought that the economy should be little intervened in by the government, with a focus on free commerce and the lowering of obstacles to agricultural productivity.

The rise of physiocrats in France gave way to a new taxation regime to finance the public sector. French philosophers Marshall Vauban and Francois Quesnay share similar views on military expenditure and state welfare. Vauban argues that an increase in the military and economic power of the king could be achieved together with an increase in the population’s well-being through an appropriate taxation system (Steiner, Citation2008). Quesnay states that the capacity of a country’s inhabitants to pay for its military through taxes is the key factor in determining a nation’s power; ultimately, a nation’s level of economic strength determines its level of power (Steiner, Citation2002). The Scottish Enlightenment in the late 18th century, led by Adam Smith and Francis Hutcheson, built on the concepts given by Quesnay. Smith regards ‘defence’ as one of the three areas requiring the expense of the sovereign or the Commonwealth and justified state intervention in the economy, along with ‘justice’ and ‘public work and public institutions’ (Coulomb, Citation1998). Smith suggests the dual theme that while increasing wealth affords the opportunity and necessity to build a standing army, that army, in turn, requires a cost with which to secure that wealth (Brauer, Citation2017). Another classical economist, John Stuart Mill claimed in the late 19th century that commerce was making war obsolete because of the potential for conflict to destroy trade (Poast, Citation2023). However, with the two world wars, the growth of networks for the armaments trade, and the division of global powers, this claim was thoroughly refuted. During the 19th century, the evolution of economics as a discipline gave rise to the neoclassical revolution as an improvement on the erstwhile dominant classical thought. It promoted a way of thinking that emphasized on thinking of marginal effects, resource scarcity, and optimal allocation.

Understanding the changing relationship between conflict, military spending, and economic ideology can be gained from examining the historical development from mercantilism to physiocracy and neoclassical economics. Nonetheless, these schools of thought are often criticised. The emphasis that mercantilism places on trade surpluses and state power can result in protectionist measures while ignoring the advantages of global cooperation. The emphasis on market efficiency in neoclassical economics may obscure social welfare issues, while the agrarian-centric beliefs and oversimplified economic models of physiocracy may ignore the intricacies of contemporary economies. Geopolitical tensions and global arms networks have also fuelled ongoing conflicts, casting doubt on the idea that trade renders war unnecessary. Developing more pertinent economic policies in the twenty-first century requires incorporating different points of view and taking larger societal effects into account.

3.3. From the neoclassicals to military Keynesianism

The early 19th century saw a revolution in economic thought with the theories of neoclassical economics, popularized by Carl Menger and Alfred Marshall. The neoclassical period resulted in a change in opinions towards the military budget. Although a few neoclassical economists acknowledged the need for defence, most of them believed that high military spending hurt the economy. Instead of focusing on military conquest, the focus changed to encouraging economic growth through free markets and effective resource allocation, as neoclassicals believed that there exists a trade-off between military and non-military expenditures. Such a trade-off emphasizes on the opportunity cost of military spending, i.e. the resources allocated to military commitments are associated with the opportunity costs of alternate expenditures on social infrastructure.

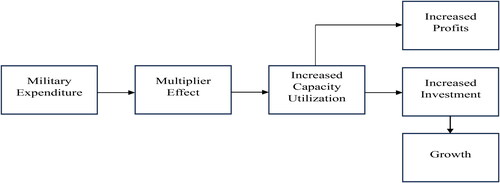

The Keynesian perspective of economic thought promotes the idea that military spending is merely a component of the state fiscal budget and has the potential to have multiplier effects on the economy through various transmission channels. Dunne (Citation2013) claims that using this strategy to finance military spending may help an economy emerge from a downturn and aid in the development of efficient demand growth. This can be based on an IS-LM framework that has been utilized by Pieroni et al. (Citation2008). In this regard, Hunt and Lautzenheiser (Citation2010) state ‘the American government spent close to $2 trillion on military expenditures between 1947 and the mid-1970s. Total annual expenditures for past, current, and future conflicts and their preparation, including military and associated costs, increased from $27.9 billion in 1947 to $112.3 billion in 1971. Together, these numbers equalled 12.2 percent of the GNP in 1947 and 11.1 percent in 1971. Additionally, the impact was considerably greater if one considers the ‘multiplier’ effect of additional aggregate demand brought about by this military spending’. However, Custers (Citation2010) claims that even though the concept of military Keynesianism emerged in opposition to Keynes’s undifferentiated theory and received some backing from critical economists, there has been a lack of theoretical depth throughout the entire debate around military spending and macroeconomic planning ().

Figure 2. Conceptual framework explaining the relationship between military expenditure and economic growth.

Source: Authors, based on Keynes (Citation1936).

When considered in modern situations, the neoclassical and Keynesian viewpoints on military spending have significant shortcomings. Neoclassical economics reduce military spending to a straightforward trade-off with non-military spending, frequently ignoring the complex geopolitical realities and security challenges faced by modern states. In the meantime, the long-term effects of large military budgets, such as resource misallocation, fiscal imbalances, and the maintenance of military-industrial complexes, may go unaccounted for by the Keynesian approach to military spending as a stimulant for economic growth. Furthermore, using military Keynesianism as a tactic to boost demand could result in unmanageable debt buildup and impede spending on infrastructure, healthcare, and education, among other vital sectors. In conclusion, both viewpoints provide insights into the financial effects of military spending, but they frequently oversimplify the complexity of today’s defence and security issues, calling for a more thorough and nuanced approach to economic planning in the modern world.

Traditional literature has a significant emphasis on restrictions over market forces and is strongly infused with a Keynesian understanding of the universe during the second world war (Harrison, Citation2009). It is therefore useful to understand the political context of the world during this time, a few alternatives and perhaps heterodox approaches to economic thought, and then further analysing the empirical evidence underpinned by this Keynesian multiplier effect, which is delved into in Section 3.8.

3.4. Political economic thought and the Cold War

It is important to keep in mind the political context of military Keynesianism and reflect on the actions of the leading world power at the time. In its initial form, the Cold War was a supposedly fatal conflict between two fiercely antagonistic blocs, one led by the Soviet Union and the other by the United States, that developed after the Second World War (Schlesinger, Citation1967). At the beginning of the Cold War, the period between 1949 and 1951 was crucial in the history of the American political economy. The U.S.’s promise to defend Western Europe served as the alliance’s cornerstone. This quickly translated to American readiness to deploy nuclear weapons in response to Soviet ‘aggression’. According to Fordham (Citation1998), between 1949 and 1951, the yearly military budget quadrupled, going from $13.5 million to $45 million. The president’s proposals for social welfare and healthcare also vanished from the table at this time.

Due to the deterioration of ties with the Soviet Union in the fifteen years after the Second World War, international affairs and foreign policy dominated the public conversation. The Berlin Blockade in 1948, the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, the highly institutionalized hostility with the Soviet Union during the Eisenhower years, the U2 spy incident in 1960, the Bay of Pigs Crisis in 1961, and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 all contributed to the public’s interest in international issues (Hibbs Jr, Citation1987). According to Hunt and Lautzenheiser (Citation2010), economists in capitalist economies were fervent in their support of a foreign policy aimed at eliminating communism wherever it existed and preventing third-world countries from experimenting with any form of socialism during the two decades immediately after World War II. As a result, a sizable military and an assertive foreign policy were backed even by ardent conservatives who favoured a laissez-faire approach, leading to military operations in Vietnam. However, after leaving Vietnam in 1975, the U.S. military returned to what it had determined to be its primary objective: to destroy Warsaw Pact forces in West Germany. The United States spent a significant portion of the 1970s finding the technological methods that would eventually lead to the 1980s concept of Air-Land Battle (Ford & Gould, Citation2019). Meanwhile, the 1973 oil crisis sparked a period of ‘stagflation’—economic stagnation coupled with excessive inflation—which sparked a crisis throughout the highly industrialized countries (Phillips, Citation2019). The 1980s were propelled by globalization in the international and domestic political spheres. The Soviet Union fell apart in the 1980s, Eastern Europe became free, and China opened (Sargent, Citation2013). The socialist system collapsed, thereby ending the Cold War.

Critics contend that military Keynesianism had serious disadvantages during the Cold War. Over-reliance on military spending as a boost for the economy increased the risk of fiscal imbalances and resource misallocation, taking money away from important social programmes and impeding long-term progress. Furthermore, the economy’s militarization may hinder innovation and prolong reliance on the defence sector. Aggressive foreign policies increased tensions and conflicts around the world, with military operations having significant financial and human costs. Military Keynesianism was seen as beneficial in the short run, but its long-term viability and ability to promote true economic prosperity and security were questioned.

3.5. Recent trends in the political economy of military spending

While ‘guns vs. butter’ is a well-known cliché regarding policy trade-offs that governments must make, a plethora of political economy research has empirically shown that this trade-off is not so simple (Whitten & Williams, Citation2011). Specifically, the negative effects of military spending on domestic welfare are overlooked by this widely held political belief. Although there is vast empirical literature which support the guns vs butter debate, Töngür and Elveren (Citation2015) is the first cogent study that explores the military spending-political regime-income inequality nexus and demonstrate a statistically significant association between military spending and social democratic political regimes and welfare. Lin et al. (Citation2015) found a beneficial trade-off between military spending and two other categories of social welfare spending, which they speculate is because OECD nations support social welfare programs more than other countries, thus when military spending rises (due to increasing military personnel and conscription, for example), the government may also boost spending on health and education. The empirical findings of Zhang et al. (Citation2017) demonstrate that, in industrialized nations, military spending increases social welfare spending; in emerging economies, the relationship is less clear. Additionally, they find that spending on the military has the potential to raise the social welfare index. Taydas and Peksen (Citation2012) demonstrate that military spending is unlikely to raise or lower the likelihood of civil unrest.

Another crucial component of military spending in contemporary political economic theory is domestic arms manufacturing. States are unable to produce enough weapons on their own (Devore, Citation2013). Almost no regular or irregular armed force has access to a self-produced full weaponry. It is common practice to utilise both externally made and externally generated weapons. According to Brauer (Citation2007), even ‘self-produced’ weapons depend to some extent on imported parts or services, including metals, software, maintenance, repair, training, and specialized materials. Because of this, a portion of the modern armaments industry is always engaged in commerce. According to Kurç and Neuman (Citation2017), the globalization of the arms trade is pressuring countries to adopt integrative, export-oriented defence sector policies.

Due to the rapid improvement of technology in the defence sector, the primary problem that nations face is becoming self-sufficient in the production of weapons (Bitzinger, Citation2011). One of the strongest primary incentives for self-reliance in defence production, according to Bitzinger (Citation2017), is the requirement for self-reliance in arms purchases driven by security. Since there is essentially no legislation in the international security system, nation-states must create their own independent defence capability. Bitzinger (Citation2015) discusses techno-nationalism, which views achieving self-sufficiency in weapons as maximising national political, strategic, and economic autonomy in addition to meeting national defence requirements. This viewpoint has a big influence on the production of weapons. Techno-nationalism is defined by Cheung (Citation2021) as a state-controlled, closed-door approach to technology innovation that aims to safeguard economic competitiveness, national security, and international stature. Additionally, he shows how techno-globalism is only beneficial if it promotes self-reliance, and how techno-nationalism and techno-globalism are complementary rather than conflicting. Developing native skills is prioritised when highly regulated protectionist regimes are adopted, which severely restrict foreign direct investment while promoting the one-way flow of cutting-edge information and technology. To be clear, techno-nationalism is a strategy for obtaining self-reliance in defence production; it is not the same as self-reliance.

Some research indicates that there is a positive trade-off between social welfare and military spending, while other studies draw attention to the possible harm that comes from disproportionate military spending on domestic welfare and income disparity. Furthermore, the globalisation of the arms trade may impede efforts to become self-sufficient in defence manufacture and maintain reliance on outside sources. The pursuit of techno-nationalism in defence innovation could result in protectionist laws that impede technical advancement and limit foreign investment. All things considered, the focus on military spending and the production of weapons ignores more significant socioeconomic issues, could make inequality worse, and restricts chances for global collaboration and innovation.

3.6. The rise of the monetarist school

Keynesian economics started failing in the 1960s because it was unable to address the issues of inflation and unemployment increasing simultaneously due to supply-side factors. The Johnson administration refused to request a tax increase when it increased military spending by $10 billion for the Vietnam War in a fully employed economy—the demand-pull’ inflation because of this action had Keynesian origins (Peterson, Citation1987). The military economy thoroughly refutes the monetarist justifications for cutting back on government spending, even though it is uncommon to hear monetarists criticize militarism (Bodington et al., Citation1986). After Reagan was elected president in January 1981, his economic advisors set about predicting the likely outcomes of his proposed economic policies, which included a formal commitment to monetarism as the Federal Reserve’s guiding policy, a plan to reduce non-military government spending while increasing military spending and substantial tax reductions (Best, Citation2020). However, the administration’s proposed tax cuts were so significant that they ran the risk of overwhelming the monetarist objectives in the face of uncertain social spending cuts and ostensibly definite military expenditures (Hale, Citation1981). The dominant priority of the Reagan administration was to cut deficits and boost the economy. Hence military expenditures took precedence on the fiscal side of the economy.

3.7. Heterodox theories

3.7.1. The Marxian ideology

Marxist theories seek to reveal fundamental truths: the well-known political events of the world—wars, agreements, and international relief efforts—all take place within structures that have a significant impact on those events (Hobden & Jones, Citation2019). These structures are the institutional components of a world capitalist system. Kakışım (Citation2021) states that according to Marxist theory, there are three main reasons why people engage in military spending under the capitalist economy. The first is to safeguard the global capitalist system from external dangers like communism and radical terrorism; the second is to maintain core states’ hegemony over periphery capitalist nations to avert potential issues; and the third is to directly boost economic growth and the profit rate through military spending’s surplus-absorbing role. According to Engels (Citation2010), military spending has no positive effect on the economy and only causes financial ruin. Luxembourg (Citation1913) contends that although military spending leads to capital accumulation, it leads to political, social, and economic hegemony by serving the interests of capitalists through the exploitation of the labour class. Rosa Luxemburg proposed the notion of underconsumption, according to which military spending offers a way to invest the surplus without expanding productive capabilities. The key argument for underconsumption is that as a capitalist economy becomes wealthier, the available surplus increases above what is strictly required for consumption and investment. It becomes more difficult to absorb the surplus and maintain effective demand, which encourages the use of military spending to counteract the economy’s propensity to enter a state of stagnation or recession. In this context, Marxist beliefs were also impacted by Keynesianism (Watterton, Citation2023). Baran and Sweezy (Citation1966) argue that military spending is essential to absorbing an ever-growing surplus product. Although arms manufacture is limited in its potential to maximise employment due to its highly advanced nature, military spending is most successful in reviving economic growth. This has the simple implication that there should be a relationship between the level of prosperity, as measured, for example, by per capita national income, since the wealthier the nation, the greater the need for military expenditure to maintain demand (Smith, Citation1977).

Marxist theories have significant shortcomings in modern contexts when it comes to comprehending military spending and its economic ramifications. Marxist theory frequently ignores the complexity of contemporary economic systems and international interdependencies, even as it highlights the role that military spending plays in upholding capitalist hegemony and absorbing excess capital. Beyond merely supporting capitalist interests, military spending can support a variety of political and economic goals in today’s interconnected globe, such as geopolitical plans, security alliances, and technological breakthroughs. Furthermore, the notion that investing in the military inevitably boosts the economy ignores possible inefficiencies, the misallocation of resources, and unfavourable externalities related to militarization. The Marxist viewpoint frequently ignores the contribution that entrepreneurship, innovation, and market dynamics make to the advancement of economic growth, preferring to concentrate on class struggles and structural inequality. As a result, even though Marxist theories provide insightful analyses of the interactions among capitalism, militarism, and economic exploitation, their applicability in modern settings may be constrained by their deterministic perspective on economic growth and their inadequate consideration of the variety of factors influencing contemporary economies.

3.7.2. The institutionalists

Capitalism underwent a major transformation in the 19th and 20th centuries and gave rise to institutional frameworks which were motivated by self-interest. Thorstein Veblen and John Kenneth Galbraith’s economic writings were the ones that best captured and expressed the institutional and cultural change of this time (Hunt & Lautzenheiser, Citation2010). While adding that military spending can be utilized to advance certain parties’ interests, the institutionalist approach to defence spending supports Keynesian theory (Dunne & Tian, Citation2013). Raifu and Aminu (Citation2023) state that more military spending would contribute to the defence of the interests of some influential groups, known as the Military-Industrial Complex. The organizations did this by exerting pressure on the government to raise military spending in a way that would benefit them. Furthermore, Galbraith, another institutional writer, disagreed with Military Keynesianism and the thesis of those strategists who believed that the only option to revive economic development in the late 1940s was for the government to intervene through an increase in military spending, which was justified by demonizing Soviet foreign policy (Cypher, Citation2008). Veblen’s fundamental stance on military spending was that it represented an entrance of backward, revanchist elements that ought to have gone out with the end of ‘dynastic’ cultures. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Veblen believes that war is central to the study of economics (Horner & Martinez, Citation1997). According to Cypher (Citation1987), Veblen’s theory of militarism as a tool for influencing or diverting the aspirations of the general populace needs to be modified and supplemented with knowledge of how the state has today—through military spending—become the main driver of technological advancement.

The ability of institutionalist viewpoints on military spending to properly account for the intricate dynamics of modern economies and societies is limited in the current setting. They may ignore other important factors influencing defence spending decisions, such as geopolitical considerations, security threats, and technological advancements, even though they rightly highlight the influence of powerful interest groups, like the Military-Industrial Complex, on government policies and military expenditures. Furthermore, in today’s globalised and interconnected world, the institutionalist critique of Military Keynesianism and emphasis on the detrimental effects of increased militarization on society may fall short of capturing the complex interactions between military spending, economic growth, and national security. Furthermore, although Veblen’s observations about how militarism influences economic behaviour are still applicable, his analysis might need to be updated to consider modern circumstances, especially in light of the complex relationship that exists between military spending and technical advancement. Thus, while institutionalist viewpoints provide insightful analyses of the political economy of defence spending, their historical focus and inadequate attention to changing geopolitical, technological, and security factors may restrict its application in contemporary settings.

3.8. The mathematical revolution and the military spending-economic growth nexus

In the late 1970s, the world saw a mathematical revolution through applying various econometric techniques to study complex economic relationships. Since Benoit (Citation1978) first proposed that military spending drives economic growth, numerous empirical studies have been conducted. Researchers have used various econometric techniques for nations and panels over multiple time frames. However, scholars have little agreement on how military spending affects the economy. Although Biswas and Ram (Citation1986) and Huang and Mintz (Citation1991) found no correlation at all, Ram (Citation1986) and Atesoglu and Mueller (Citation1990) found a positive influence using the Feder-Ram models (Chary, Citation2023). Using a single demand-side equation, Smith (Citation1987) and Rasler and Thompson (Citation1988) showed that military spending negatively affected economic growth. Military spending does not increase economic growth, according to results from most simultaneous equation models (Deger, Citation1986). Since the 1990s, numerous studies have been on the military spending-economic growth nexus. The dynamic nature of the globalized world, coupled with the nuances of war, peace, welfare, political regimes, economic status, and arms races, makes it difficult for econometric works to arrive at a consensus on the topic of military spending and economic growth.

There are three commonly used empirical frameworks under which the military spending-economic growth nexus have been examined. First, the rather simple Feder-Ram model was inspired by the study of Biswas and Ram (Citation1986) and then further adapted by many researchers in the two decades that followed (see for e.g. Antonakis, Citation1997; Atesoglu & Mueller, Citation1990; Deger & Sen, Citation1983; Huang & Mintz, Citation1991; Sezgin, Citation1997; Ward et al., Citation1994). However, Dunne et al. (Citation2005) give a critical review of the Feder-Ram models in evaluating the military-spending economic growth nexus due to econometric problems such as simultaneity biases and lack of dynamics. The augmented Solow model used by Knight et al. (Citation1996) has fewer theoretical drawbacks. Empirical works using the augmented Solow model appear to have more coherent results and is hence more widely used (see for e.g. Dunne et al., Citation2005; Dunne & Nikolaidou, Citation2012; Heo, Citation2010; Töngür & Elveren, Citation2015; Yildirim & Öcal, Citation2016). Finally, the Barro model used by Aizenman and Glick (Citation2006) appears to be the most promising due to its ability to accommodate security effects (see for e.g. Dimitraki & Menla Ali, Citation2015; Manamperi, Citation2016; Stroup & Heckelman, Citation2001). Due to resource limitations, the model concentrates on how nations respond to the trade-off between security interests and all other economic demands (Smith, Citation1995). According to this concept, the state’s armed forces’ resources are allocated differently for foreign military threats than for the military forces of other states (Sakib & Rahman, Citation2023).

Since the seminal works, there have been various theoretical improvements in the examination of the relationship between military spending and economic growth. Brauer (Citation2002) indicates that when examining the economic impact of military expenditures on indicators of economic performance, such economic growth, share data, such as military spending as a percentage of GDP (Military Burden), may be more suitable. Cuaresma and Reitschuler (Citation2004) examine the potential for a non-linear relationship between military spending and economic growth. The reason for such non-linearities is that military spending is necessary to achieve security. This explanation is consistent with the concept that, in the extreme situation, there may be several growth regimes because of the marginal effect of a change in the military burden being non-constant across different levels of the variable and across different economies (Cuaresma & Reitschuler, Citation2006). Aizenman and Glick (Citation2006) conduct an empirical assessment of the nonlinear relationships that exist between military spending, external threats, corruption, and other pertinent factors. They demonstrate that military spending in the face of threats increases growth, even though growth declines with increasing levels of military spending.

There are various drawbacks to the modern econometric frameworks that are used to examine the connection between defence spending and economic expansion. Regarding the precise effect of military spending on economic growth, there is still little agreement despite the abundance of research using different models. Unresolved issues including simultaneity biases, dynamics gaps, and challenges in accounting for security impacts continue to impede the progress towards a cohesive understanding. It is also difficult to identify distinct causal linkages between military spending and economic performance due to the complexity of global dynamics, which include political regimes, armaments races, and war and peace. Furthermore, despite efforts to look at nonlinear linkages and include metrics like military burden and external threats, these methods may still miss subtle interactions and fall short of capturing the full complexity of the military spending-economic growth nexus.

4. Discussion

The historical trajectory from mercantilism to physiocracy and neoclassical economics provides valuable insights into the evolving relationship between conflict, military spending, and economic ideology. During the rise of mercantilism in the 16th century, European nations began to view the state as an economic entity, emphasizing trade, tariffs, and military action to further national interests. This period saw the emergence of permanent mercenary armies and costly military methods, prompting monarchs to expand their financial requirements to maintain vast armies and assert their authority. Figures like Jean-Baptiste Colbert and John Locke advocated for significant war funds to ensure national security and economic prosperity, laying the groundwork for linking financial resources to military might. The transition to physiocracy in the early 18th century marked a shift towards laissez-faire economic principles, with a focus on free commerce and agricultural productivity. French philosophers such as Vauban and Quesnay emphasized the importance of an appropriate taxation system to finance both military and economic endeavours, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between military expenditure and state welfare. This period set the stage for Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, who further developed theories on the economic rationale behind military spending, positioning it as a necessary expense for safeguarding national wealth and security.

When examining modern situations, both neoclassical and Keynesian viewpoints on military spending reveal significant shortcomings. Neoclassical economics tends to oversimplify the complexities of contemporary geopolitical realities and security challenges, reducing military spending to a straightforward trade-off with non-military expenditures. This perspective often ignores the long-term effects of large military budgets, such as resource misallocation, fiscal imbalances, and the perpetuation of military-industrial complexes. On the other hand, the Keynesian approach to military spending as a stimulant for economic growth may overlook the detrimental impacts of excessive military expenditures, including unsustainable debt accumulation and the diversion of resources away from vital sectors like infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Consequently, both viewpoints fail to fully grasp the intricate dynamics of modern defence and security issues, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive approach to economic planning in contemporary contexts.

The political context of military Keynesianism during the Cold War era sheds light on the actions of leading world powers and their impact on economic policies. The Cold War rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States fuelled a significant increase in military expenditures, with the U.S. quadrupling its yearly military budget between 1949 and 1951. The perceived threat of communism and the desire to maintain global hegemony led to aggressive foreign policies and military interventions, such as the Vietnam War. However, critics argue that over-reliance on military spending during this period resulted in fiscal imbalances, resource misallocation, and increased tensions worldwide. The end of the Cold War saw a shift towards globalization, but the legacy of militarization persisted, raising questions about the long-term viability of military Keynesianism and its ability to promote genuine economic prosperity and security.

Marxist theories offer a critical perspective on military spending within the context of capitalist economies, emphasizing its role in upholding capitalist hegemony, maintaining social control, and absorbing excess capital. According to Marxist analysis, military spending serves to safeguard the global capitalist system, maintain core states’ dominance over peripheral nations, and contribute to economic growth through the surplus-absorbing role of military expenditure. However, Marxist theories have limitations in understanding the complexities of modern economies and international relations, often overlooking factors such as entrepreneurship, innovation, and market dynamics. While providing insightful analyses of capitalism, militarism, and economic exploitation, Marxist perspectives may be constrained by their deterministic view of economic growth and their insufficient consideration of contemporary economic factors.

In contrast, institutionalist viewpoints, represented by scholars like Thorstein Veblen and John Kenneth Galbraith, offer insights into the role of military spending within institutional frameworks and self-interested motivations. Institutionalists highlight how military spending can advance the interests of influential groups, such as the Military-Industrial Complex, and how it has historically been used as a tool to divert societal aspirations. However, these perspectives may overlook important factors such as geopolitical considerations, security threats, and technological advancements, limiting their ability to fully account for the complex interactions between military spending, economic growth, and national security in today’s globalized world. While institutionalist analyses provide valuable insights into the political economy of defence spending, their historical focus and inadequate attention to changing geopolitical and technological factors may constrain their applicability in contemporary settings.

The historical evolution of economic thought from mercantilism to neoclassical economics provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between conflict, military spending, and economic ideology. While different schools of thought offer diverse perspectives on the economic implications of military expenditures, the overarching theme highlights the interconnectedness of military and economic policies. Moving forward, policymakers must consider the broader societal effects of military spending and adopt more nuanced economic policies that account for the multifaceted nature of defence expenditures in a constantly evolving global landscape.

5. Conclusions

Our exploration aimed to unravel the often-overlooked economic dimensions of military spending, traversing through centuries of economic thought to illuminate its significance. We embarked on a journey to understand the viewpoints proposed by various economic schools of thought on military expenditure and to emphasize its importance within the broader economic discourse. Through meticulous analysis and synthesis of historical perspectives, theoretical frameworks, and empirical evidence, we sought to shed light on the intricate interplay between military expenditures and economic dynamics.

Our investigation into the economic dimensions of military spending yielded diverse insights into the historical, theoretical, and empirical underpinnings of this complex phenomenon. We traversed through centuries of economic thought, beginning with medieval admonitions against overspending on military activities to contemporary debates surrounding the role of military expenditures in stimulating economic growth. Across different epochs, economic theorists grappled with the intricate trade-offs involved in allocating scarce resources to defence, reflecting broader societal values, political agendas, and technological advancements. The evolution of economic paradigms—from mercantilism to neoclassical and Keynesian economics—unveiled shifting perspectives on the economic rationale behind military expenditures. While neoclassical economists emphasized the opportunity cost of military spending, Keynesians championed its role in stimulating aggregate demand during periods of economic downturn. Moreover, heterodox perspectives such as Marxism and institutionalism challenged conventional wisdom, shedding light on the underlying power dynamics and vested interests shaping defence policies. Through meticulous analysis and synthesis of historical perspectives, theoretical frameworks, and empirical evidence, our study provided a comprehensive overview of the economic dimensions of military spending, offering fresh insights into its far-reaching implications for economic growth, inequality, and societal well-being.

However, our study is not without limitations. While we attempted to provide a comprehensive overview of the economic dimensions of military spending, our analysis may be constrained by the availability and quality of historical data, as well as the inherent biases within economic theories themselves. Moreover, the complexities of military expenditures extend beyond purely economic considerations, encompassing geopolitical, social, and ethical dimensions that warrant further exploration. Despite these limitations, our research contributes to a broader understanding of defence economics and highlights the need for interdisciplinary approaches to address the multifaceted challenges posed by military spending in the contemporary world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shreesh Chary

Shreesh Chary is a graduate student specializing in Development Economics at the University of Nottingham. He holds a Bachelor of Science (Honours) degree in Economics from Symbiosis School of Economics, Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Niharika Singh

Niharika Singh is an Assistant Professor and teaches History of economics Thought at Symbiosis School of Economics, Pune. Her research interest lies in Economic Thought, Labour Economics and Development Issues.

References

- Aizenman, J., & Glick, R. (2006). Military expenditure, threats, and growth. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 15(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638190600689095

- Antonakis, N. (1997). Military Expenditure and Economic Growth in Greece, 1960–90. Journal of Peace Research, 34(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343397034001007

- Atesoglu, H. S., & Mueller, M. J. (1990). Defence spending and economic growth. Defence Economics, 2(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10430719008404675

- Baran, P., & Sweezy, P. (1966). Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press.

- Barkawi, T. (2019). War and world politics. In The globalization of world politics (pp. 225–239). Oxford University Press.

- Baylis, J., Smith, S., & Owens, P. (2020). The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford University Press.

- Benoit, E. (1978). Growth and defense in developing countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 26(2), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1086/451015

- Best, J. (2020). The quiet failures of early neoliberalism: From rational expectations to Keynesianism in reverse. Review of International Studies, 46(5), 594–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210520000169

- Biswas, B., & Ram, R. (1986). Military expenditures and economic growth in less developed countries: An augmented model and further evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 34(2), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1086/451533

- Bitzinger, R. A. (2011). China’s defense technology and industrial base in a regional context: Arms manufacturing in Asia. Journal of Strategic Studies, 34(3), 425–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2011.574985

- Bitzinger, R. A. (2015). Comparing defense industry reforms in China and India. Asian Politics & Policy, 7(4), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12221

- Bitzinger, R. A. (2017). Asian arms industries and impact on military capabilities. Defence Studies, 17(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2017.1347871

- Bodington, S., George, M., & Michaelson, J. (1986). The political economy of militarism. In Developing the socially useful economy. Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-18155-1_11

- Brauer, J. (2002). Survey and review of the defense economics literature on Greece and Turkey: What have we learned? Defence and Peace Economics, 13(2), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690210969

- Brauer, J. (2007). Chapter 30 Arms Industries, Arms Trade, and Developing Countries, 973–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0013(06)02030-8

- Brauer, J. (2017). ‘Of the Expence of Defence’: What has changed since Adam Smith? Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 23(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2017-0012

- Chary, S. (2023). The nexus between arms imports, military expenditures and economic growth of the top arms importers in the world: A pooled mean group approach. Journal of Economic Studies, 2023, 65. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-05-2023-0265

- Cheung, T. M. (2021). A conceptual framework of defence innovation. Journal of Strategic Studies, 44(6), 775–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2021.1939689

- Coulomb, F. (1998). Adam smith: A defence economist. Defence and Peace Economics, 9(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10430719808404905

- Cuaresma, J. C., & Reitschuler, G. (2004). A non-linear defence-growth nexus? evidence from the US economy. Defence and Peace Economics, 15(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/1024269042000164504

- Cuaresma, J. C., & Reitschuler, G. (2006). “Guns or butter?” Revisited: Robustness and nonlinearity issues in the defense–growth nexus. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 53(4), 523–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9485.2006.00393.x

- Custers, P. (2010). Military Keynesianism today: An innovative discourse. Race & Class, 51(4), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396810363049

- Cypher, J. M. (1987). Military spending, technical change, and economic growth: A disguised form of industrial policy? Journal of Economic Issues, 21(1), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.1987.11504597

- Cypher, J. M. (2008). Economic consequences of armaments production: Institutional perspectives of J.K. Galbraith and T.B. Veblen. Journal of Economic Issues, 42(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2008.11507113

- Deger, S. (1986). Economic development and defense expenditure. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 35(1), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1086/451577

- Deger, S., & Sen, S. (1983). Military expenditure, spin-off and economic development. Journal of Development Economics, 13(1-2), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(83)90050-0

- Devore, M. R. (2013). Arms production in the global village: Options for adapting to defense-industrial globalization. Security Studies, 22(3), 532–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2013.816118

- Dimitraki, O., & Menla Ali, F. (2015). The long-run causal relationship between military expenditure and economic growth in China: Revisited. Defence and Peace Economics, 26(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2013.810024

- Dunne, J. P., & Nikolaidou, E. (2012). Defence Spending and Economic Growth in the EU15. Defence and Peace Economics, 23(6), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2012.663575

- Dunne, J. P., Nikolaidou, E., & Chiminya, A. (2019). Military spending, conflict and external debt in Sub-Saharan Africa. Defence and Peace Economics, 30(4), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2018.1556996

- Dunne, J. P., Smith, R. P., & Willenbockel, D. (2005). Models of military expenditure and growth: A critical review. Defence and Peace Economics, 16(6), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690500167791

- Dunne, J. P., & Tian, N. (2013). Military expenditure and economic growth: A survey. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.15355/epsj.8.1.5

- Dunne, P. J. (2013). Military Keynesianism: An assessment. Cooperation for a peaceful and sustainable world Part 2 (Contributions to Conflict Management, Peace Economics and Development, Vol. 20 Part 2) (pp. 117–129). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1572-8323(2013)00020.2011

- Engels, F. (2010). Kann Europa abrüsten? In Band 32 Friedrich Engels: Werke, Artikel, Entwürfe, März 1891 bis August 1895 (pp. 991–1009). Akademie Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783050088570-045

- Fontanel, J., Hebert, J., & Samson, I. (2008). The Birth of the Political Economy or the Economy in the Heart of Politics: Mercantilism. Defence and Peace Economics, 19(5), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690802354279

- Ford, M., & Gould, A. (2019). Military identities, conventional capability and the politics of NATO Standardisation at the Beginning of the Second Cold War, 1970–1980. The International History Review, 41(4), 775–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1452776

- Fordham, B. (1998). Cold war consensus: The Political Economy of the US National Security. University of Michigan Press.

- Hale, D. (1981). Thatcher and Reagan: Different roads to recession. Financial Analysts Journal, 37(6), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v37.n6.61

- Hale, J. R. (1988). A humanistic visual aid. The military diagram in the Renaissance. Renaissance Studies, 2(2), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-4658.1988.tb00157.x

- Harrison, M. (2009). The economics of World War II: An overview. In The Economics of World War II. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511523632.002

- Heo, U. (2010). The Relationship between Defense Spending and Economic Growth in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 63(4), 760–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912909334427

- Hibbs, D. A.Jr. (1987). The American Political Economy: Macroeconomics and electoral politics. Harvard University Press.

- Hobden, S., & Jones, R. W. (2019). Marxist theories of international relations. In The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/hepl/9780198825548.003.0007

- Horner, J., & Martinez, J. (1997). Thorstein Veblen and Henry George on war, conflict, and the military: An institutionalist connection. Journal of Economic Issues, 31(2), 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.1997.11505955

- Huang, C., & Mintz, A. (1991). Defence expenditures and economic growth: The externality effect. Defence Economics, 3(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10430719108404713

- Hunt, E. K., & Lautzenheiser, M. (2010). History of economic thought: A critical perspective. Routledge.

- Kakışım, C. (2021). Review of “The Economics of Military Spending: A Marxist Perspective“. Defence and Peace Economics, 32(5), 635–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1901455

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Knight, M., Loayza, N., & Villanueva, D. (1996). The peace dividend: Military spending cuts and economic growth. Staff Papers – International Monetary Fund, 43(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867351

- Kurç, Ç., &Neuman, S. G. (2017). Defence industries in the 21st century: A comparative analysis. Defence Studies, 17(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2017.1350105

- Lacey, J. (2015). Gold, blood, and power: Finance and war through the ages.

- Lin, E. S., Ali, H. E., & Lu, Y.-L. (2015). Does military spending crowd out social welfare expenditures? Evidence from a Panel of OECD Countries. Defence and Peace Economics, 26(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2013.848576

- Luxembourg, R. (1913). The accumulation of capital.

- Manamperi, N. (2016). Does military expenditure hinder economic growth? Evidence from Greece and Turkey. Journal of Policy Modeling, 38(6), 1171–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2016.04.003

- Owens, P., Baylis, J., & Smith, S. (2019). From international politics to world politics. In The Globalization of World Politics.

- Paganelli, M. P., & Schumacher, R. (2018). The vigorous and Doux soldier: David Hume’s military defence of commerce. History of European Ideas, 44(8), 1141–1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2018.1509225

- Peterson, W. C. (1987). Macroeconomics: Where are we? Review of Social Economy, 45(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346768700000005

- Phillips, N. (2019). Global political economy. In The globalization of world politics (pp. 256–270).

- Pieroni, L., D’Agostino, G., & Lorusso, M. (2008). Can we declare military Keynesianism dead? Journal of Policy Modeling, 30(5), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2008.02.005

- Poast, P. (2023). Economics and war. In D. Reiter (Ed.), Understanding war and peace.

- Prak, M. (2015). Citizens, soldiers and Civic Militias in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Past & Present, 228(1), 93–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtv030

- Raifu, I. A., & Aminu, A. (2023). The effect of military spending on economic growth in MENA: Evidence from method of moments quantile regression. Future Business Journal, 9(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-023-00181-9

- Ram, R. (1986). Government size and economic growth: A new framework and some evidence from cross-section and time-series data. American Economic Review, 76(1), 191–203.

- Rasler, K. A., & Thompson, W. R. (1988). War and systemic capability reconcentration. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 32(2), 335–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002788032002005

- Robinson, E. V. D. (1900). War and economics in history and in theory. Political Science Quarterly, 15(4), 581–586.

- Sakib, N., & Rahman, M. M. (2023). Military in the cabinet and defense spending of civilian governments. International Interactions, 49(3), 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2023.2177283

- Sargent, D. (2013). The Cold War and the international political economy in the 1970s. Cold War History, 13(3), 393–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2013.789693

- Schlesinger, A. (1967). Origins of the Cold War. Foreign Affairs, 46(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.2307/20039280

- Sezgin, S. (1997). Country survey X: Defence spending in Turkey. Defence and Peace Economics, 8(4), 381–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10430719708404887

- Shahbaz, M., Afza, T., & Shabbir, M. S. (2013). Does defence spending iimpede economic growth? Cointegration and causality analysis for Pakistan. Defence and Peace Economics, 24(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2012.723159

- Smith, R. (1995). Chapter 4 The demand for military expenditure.Handbook of defence economics (Vol 1, pp. 69–87). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0013(05)80006-7

- Smith, R. P. (1977). Military expenditure and capitalism. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035351

- Smith, R. P. (1987). The demand for military expenditure: A correction. The Economic Journal, 97(388), 989. https://doi.org/10.2307/2233085

- Steiner, P. (2002). Wealth and power: Quesnay’s Political Economy of the “Agricultural Kingdom”. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 24(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10427710120115846

- Steiner, P. (2008). Physiocracy and French pre Classical Political Economy. In A companion to the history of economic thought (p. 62).

- Stroup, M. D., & Heckelman, J. C. (2001). Size of the Military Sector and Economic Growth: A panel data analysis of Africa and Latin America. Journal of Applied Economics, 4(2), 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2001.12040568

- Taydas, Z., & Peksen, D. (2012). Can states buy peace? Social welfare spending and civil conflicts. Journal of Peace Research, 49(2), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311431286

- Töngür, Ü., & Elveren, A. Y. (2015). Military expenditures, income inequality, welfare and political regimes: A dynamic panel data analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 26(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2013.848577

- Ward, M. D., Payne, J. E., & Sahu, A. P. (1994). Double take: Re-examining the defense-growth linkage. Mershon International Studies Review, 38(2), 315. https://doi.org/10.2307/222733

- Watterton, J. J. (2023). Military spending and economic development: A theoretical note. Human Geography, 16(2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427786221147613

- Whitten, G. D., & Williams, L. K. (2011). Buttery guns and welfare hawks: The politics of defense spending in advanced industrial democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00479.x

- Yildirim, J., & Öcal, N. (2016). Military expenditures, economic growth and spatial spillovers. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2014.960246

- Zhang, X., Chang, T., Su, C.-W., & Wolde-Rufael, Y. (2016). Revisit causal nexus between military spending and debt: A panel causality test. Economic Modelling, 52, 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.10.032

- Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Xu, J., & Wang, R. (2017). Does military spending promote social welfare? A comparative analysis of the BRICS and G7 countries. Defence and Peace Economics, 28(6), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2016.1144899