Abstract

Since Ghana gained independence in 1957, successive governments have implemented various development interventions aimed at poverty alleviation. Yet, the dilemma of uneven development persists amongst rural and urban areas and between Northern and Southern Ghana. The implications of these growing disparities are far-reaching. A myriad of migration streams from Northern to Southern Ghana aimed at better lives have been chronicled since pre-colonial era. However, very few empirical studies have tried to examine the impact of migration on overall wellbeing of migrants. This paper used cross-sectional survey data gathered through a structured questionnaire and key informant interviews to assess the contribution of internal migration on human wellbeing. The findings reveal that the proportion of migrants who were food secured increased from 8.3% (before migration) to 34.4% (after migration). The results further indicate that there is a statistically significant increase in the average income, expenditure, and savings of migrants after migration; and there is a statistically significant increase in the number of migrants who own houses after migration. The findings are an indication that internal migration in Ghana has had a positive impact on the health, economic and social conditions of migrants. The study acknowledges that the well-being of migrants extends beyond these factors and calls for further research to investigate the impact of migration on other aspects of wellbeing such as psychological well-being.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Ghana like many other developing countries is confronted with the dilemma of disparities in distribution of natural resources, social amenities, and uneven development (Adamtey et al., Citation2015). These uneven development patterns are anchored on colonial legacy, geographical factors, economic structures, and governance factors. After six decades of political independence, the dilemma of uneven development persists. The implementation of diverse development interventions by successive governments has not alleviated the disparities, which persist amongst rural and urban areas and between Northern and Southern Ghana. The implications of these growing disparities are far-reaching, with consequences for various aspects of society. These consequences include higher poverty rates, lower standards of living, and lower life expectancy and literacy rates (Akrofi et al., Citation2018). Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions that prioritize even development, investment in education, agriculture, healthcare, and general infrastructure.

In recent times, seasonal and sometimes permanent internal migration to Southern Ghana, especially the cashew growing centres has become widespread among inhabitants of the five Northern regions (Adamtey et al., Citation2015). Since pre-colonial era, Northern Ghana has been characterized by a myriad of migration streams targeted at better lives (Awumbila, Citation2017). During both the colonial and post-colonial periods, migration from Northern to Southern Ghana has been primarily driven by the demand for labor in cash crop production areas (cocoa) and mining areas. Additionally, the search for better economic opportunities and improved social amenities has played a significant role in this migration (Adamtey et al., Citation2015; Awumbila, Citation2017).

Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) cultivation, driven by global demand, has a historical root in Ghana from 1960s but gained significance as a commercial crop in the 1990s (Monteiro et al., Citation2017). Ghana first exported about 15 tons of cashew nut in 1991 but surged to 171,924 tons in 2019 (Ackah et al., Citation2020; Akyereko et al., Citation2022). This gain in momentum is in response to the economic opportunities in employment and income, which cashew cultivation has. While cashew cultivation contributes to Ghana’s economy, regional disparities exist, with specific areas like Ahafo, Ashanti, Bono, and Bono East becoming key cashew hubs. This regional concentration has led to labor migration from other regions to the Southern cashew-growing centers (ADRA, Citation2022). Historical migration patterns in Ghana is tied to employment opportunities, especially in cash crop production areas. Although the statistics favor North-South migration, recent trends show an increase in rural-urban migration, notably among youth seeking opportunities in cities. The 2021 census indicates that regions with cashew cultivation, like Ahafo, Bono East, and Ashanti, experience population gains through migration, while Northern regions witness out-migration (GSS, 2023). This suggests that the geographical dynamics of cashew cultivation play a crucial role in shaping migration patterns, with Southern regions attracting migrants from the Northern regions. The economic benefits of cashew cultivation underscore its role not only in trade but also in influencing demographic trends and migration dynamics in Ghana.

A huge strand of migration literature in Ghana has examined the rationale for migration (Awumbila, Citation2017), social and economic impacts of migration in origins and income and consumption patterns of migrant households (Arthur-Holmes & Busia, Citation2022). There is also a large volume of literature on environmental consequences of migration (Van der Geest, Citation2011). Some scholars have focused on returns from migration including employment prospects and wage gains (Hart, Citation2018). Although migrants can attain gains in some dimensions, such as better wages, they may suffer other dimensions including lack of social cohesion or friendship in destination (Qin, Citation2010). Currently, very few empirical studies try to examine the impact of migration on overall wellbeing of migrants. An assessment of the overall wellbeing of migrants can permit a holistic assessment of gains and losses of migration (Kratz, Citation2020). Assessing wellbeing as a return from migration can serve as a warning to potential migrants. Such an assessment can provide relevant insights into how to attain even distribution of development interventions and social amenities for enhanced quality of life in all parts of the country.

Calls for an examination of the impact of migration on overall wellbeing have been intensified by prevailing research on living standards due to recent global events such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The Covid-19 pandemic brought about widespread job and income losses, financial hardships, widening income inequality and decline in living standards for the masses. Some negative consequences of the pandemic are like wounds that heal, while other negative events resemble scars leading long-term declines in well-being. Given that the pandemic and other global crisis have affected living standards, it is imperative to examine the interface of migration and wellbeing post Covid-19 era (Kratz, Citation2020). This study therefore seeks to examine the overall wellbeing impact of internal migration on migrants in Ghana. The study contributes to the literature on migration and well-being by examining whether internal migration constitutes human life events. Specifically, it investigates the potential for internal migration to improve well-being. The study further contributes to migration discourse by providing empirical evidence of the type of internal migration (rural-urban, rural-rural, urban-rural, urban-urban) that greatly impacts on human wellbeing. This paper is apportioned into five sections. The introduction section 1 is proceeded by section 2 which details the context of study area and research methodology. Section 3 provides the results while section 4 presents the discussion of the findings. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Study context and methodology

2.1. Study context

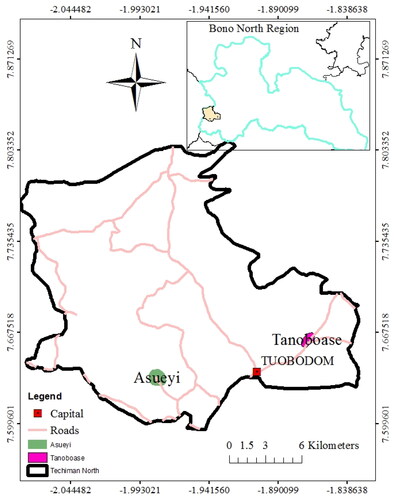

This study was conducted in Asueyi and Tanoboase communities in the Techiman North District of Bono East Region. Bono East Region is located on latitude 7° 14’ 2" N and longitude 2° 17’ 50" W. The region’s total population of 1,208,965 constitute 3.9% of the national population. Bono East Region covers an area of 11,113 km2. Population density in the region is 108.8/km2 (GSS, 2023). The region’s topography is characterized by a low elevation not exceeding 152 metres above sea level with moist semi-deciduous forest. The soil is very fertile. The region is one of the leading producers of cash crops like cashew and food crops such as cassava, maize, cassava, cocoyam, and plantain.

2.2. Methodology

The study used cross-sectional survey data gathered through a structured questionnaire and key informant interviews. Systematic random sampling approach was used to select households to respond to the questionnaire. Purposive sampling was used to select participants for the key informant interviews. Following the argument by Hair et al. (Citation1998) on an appropriate sample size, a total of 158 out of a population of 731 households answered the questionnaire while 10 key informant interviews were conducted. According to the available data from the 2010 population and housing census of Ghana, there are 199 and 532 households in Tanoboase and Asueyi, respectively (GSS, Citation2014). To qualify as a key informant, a migrant should have had an extended years of residence, at least ten years in his/her destination or a recent migrant (less than five years). In addition, he/she should be engaged in cashew farming at the destination and/or engage in various economic activities both at the destination and origin, and preferably holds a leadership position. Qualify participants were continually recruited until data saturation was reached. Both descriptive and inferential statistics study design were employed for the analysis. Descriptive statistics (percentages) is generated from the response to the demographic characteristics and the migrants’ migration experience variables. To assess the difference in some of the variables for migrants before and after migration conditions, the paired sample t-test (Daniel & Cross, Citation2018) and McNemer test (Pembury Smith & Ruxton, Citation2020; Bennett & Underwood, Citation1970) were performed to find out if there are statistically significant differences in migrant’s socioeconomic conditions before and after migration.

2.3. Paired sample t-test

The paired sample t-test is a statistical procedure for comparing two means (from two measurements of the same sample size (n) on continuous variables). The goal for performing paired sample t-test is to test if there is statistical evidence that the mean is different from zero (0). It is commonly used for before and after analysis, where the same group of participants or subjects is measured or assessed under two different conditions or at two different time points (e.g. Cachero et al., Citation2023; Horne et al., Citation2020). The rationale for using the paired sample t-test in before and after analysis is based on the principle of controlling for individual differences and reducing variability. However, before a dataset can be used to perform a paired sample t-test, the data must follow certain assumptions, such as the variables must be continuously measured at interval or ratio; the observation must be independent of one another; the variable must be approximately normally distributed; and the observation must not contain outliers (Daniel & Cross, Citation2018). The test follows a hypothesis where the null hypothesis states that the difference between the paired sample mean is different from zero, while the alternative hypothesis states the difference is not equal to zero.

The result is compared to a critical value to determine if the difference is statistically significant; hence, make a judgement on the hypothesis. The rejection of the hypothesis means there is difference, and that the intervention is effective whereas failure to reject means there is no difference and that the intervention is ineffective.

2.4. McNemer’s test of matching pairs

The McNemar test is a statistical method used to test matched paired binary data to observe the statistical difference. It is mostly used in public health studies to estimate marginal homogeneity, marginal risk differences, and marginal odds ratios (Ingo, Citation2015). Usually the matched binary can arise when we measure a response at two occasions, match on case status in a retrospective study or match on exposure status in a prospective or cross-sectional study. In this design individuals are measured twice or once for each of two dichotomous factors. Since we have variables with a dichotomous response, the McNemar’s test for two paired proportions is used to specifically examine changes in migrants’ livelihood before and after migration. Hence, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is evidence to suggest a change in condition between the two polls (before and after migration). Furthermore, the study employs the principal component analysis (PCA) method to create an index for some of the variables. This was done to help quantify dichotomous response and other expression of migrant’s views into continuous variables to facilitate the analysis (Al-Maruf et al., Citation2022). Specific variables for which index were created included household assets and social condition indicators.

2.5. Limitations to the methodology

Despite these methods, potential biases and limitations include the possibility of recall bias in reporting past experiences, and the generalizability of findings limited to the specific context of Tanoboase and Asueyi. Additionally, variations in individual experiences may affect the overall validity and generalizability of the study’s findings. However, this weakness, especially the recall bias and variations in experiences, will be minimize to some extent by the use of both KII triangulate the results.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the respondents presented in show that the majority (58.9%) are males. However, the difference that may account for gender biasness of the study is not that much (about 7%). This, coupled with the age distribution, indicates that the sample is a representation of the target population; consequently, the findings would be appropriate for generalization. From the age during migration, almost 96% of the migrants migrated when they were between the ages of 19 and 45 years. The implication is that the majority of the people who migrate to the cashew growing sectors in Ghana are the youth. Notwithstanding, some of these migrants (about 20.3%) have lived at their destination (cashew growing centres) for more than 20 years. However, those who indicated they have lived in their current destination for between 6 and 10 years constituted the majority (29.1%). Regarding the part of the country where the migrants migrated from, the results revealed that the majority (62%) of the migrants migrated from the northern zone of Ghana with a few (7.6%) indicating that they came from the coastal zone. The majority of the migrants (64%) reported that it has been less the 3 years (36 months) since they last visited their home (origin) and the reason for the majority of them visiting home is as result of either the death of a family member or for family care as indicated by 39.2% and 38% of the respondents, respectively.

Table 1. Respondents’ demographics.

3.2. The impact of migration on migrants’ health condition

The impact of migration on the migrant’s health condition is examined in this section. The McNemar’s case-control matching test, which is popularly used in quasi experimental studies, particularly in the public health sector, was employed (Olowoyeye et al., Citation2019). The method is used to compare the migrant’s health condition, in terms of disease exposure and the overall health status, before and after migration. presents the results of the McNemar test on migrants’ exposure to diseases. The results show that for diseases like Malaria, Cholera and Typhoid the test is not statistically significant (X2 = 3.00, P > 0.05; X2 = 1.00, P > 0.05; X2 = 2.00, P > 0.05, respectively). This means that there is no statistical evidence to support that there is a difference in exposure to these diseases before and after migrating to the cashew centres at the 5% significance level. However, for chicken pox, infectious disease and chronic disease, there is statistical evidence (X2 = 9.32, P < 0.01; X2 =18.84, p < 0.01; X2 =48.05, P < 0.01) at the 1% significance level to report differences in migrants’ disease exposure before and after migration. For chicken pox, only 7 migrants (6.5%) indicated they did not suffer from the disease prior to migrating to the cashew growing centre but 24 migrants (48%) reported they did not suffer from chicken pox after migrating to the cashew growing area. This implies there has been a decrease in the number of migrants who are exposed to chicken pox disease from before to after migration.

Table 2. McNermar’s test.

Similar findings are revealed with regards to infectious and chronic diseases. Ten (17.5%) and nine (18.4%) migrants reported that they did not suffer from either infectious or chronic disease, respectively, before migration but 41(40.6%) and 71(66.4%) reported not suffering from the same diseases after migration. For the overall health status of the migrants, the result showed no statistical significant evidence at the 5% level of significance (0.50, P > 0.05) to conclude that a migrant had either a negative or positive health status before and after migration.

The paper further evaluated the healthcare services migrants subscribed to or were accessible to in their home (origin) relative to their destination at the cashew growing centres. From , the McNemer test indicates a statistical significance difference in the healthcare services of migrants between before and after migration at the 1% level of significance. Regarding where migrants go for healthcare service, there is a statistically significant decrease in the number of migrants who practiced self-treatment (self-medication) from before to after migration. Specifically, seven migrants (8%) reported they did not practice self-treatment before migration whereas 15(21.4%) said they do not practice self-medication after migrating to their destination. There is also a decrease in the number of migrants who seek medical care from traditional method as well those who visit the CHIPS compound for treatment any time they are sick as they migrate to their destination. Thus, only one migrant (14%) indicated he/she did not seek traditional health care before migrating but when it comes to after migration 29 migrants (19.2%) are now not seeking traditional healthcare service. The same trend is observed for CHIPS compound where three migrants (25%) as compared to 31 migrants (26%) who reported they did not seek healthcare service from CHIPS compound before and after migration, respectively.

Table 3. McNermar test results of migrants’ healthcare service.

Conversely, there is a statistically significant increase in the number of migrants who reported that they sought healthcare from a district hospital between before and after migration: 52 (37.1%) migrants did not go to a district hospital for treatment when they were sick before migration as against only two migrants (11.1%) who reported a similar case in the after-migration context.

Regarding food security, the results shows migrants are food secure in the cashew growing centres since 42(34.4%) of the respondents reported they were food insecure before migration but after migration only three (8.3%) indicated they were insecure. This finding confirms the finding of Yeboah et al. (Citation2023) from a study on smallholder cashew production and household livelihoods in Ghana, which concluded that cashew production improved food security since farmers inter-crop and some food crops like yam, cocoyam and cassava do well even under matured cashew plantation.

Regarding health insurance registration and validity of the health insurance identity card, the results indicate similar findings of increase from before to after migration. All the migrants are registered for NHIS at the destination but seven migrants (47.9%) indicated they had not registered before migration. While 69 migrants (51.1%) indicated that although they had registered before migration their card was not valid, four migrants (17.4%) reported the same after migration.

3.3. The impact of migration on migrants’ economic condition

Migrants’ economic condition is analysed using data gathered from migrants’ household average monthly income and expenditure, and from average annual savings. The paired sample t-test for independence is employed to evaluate differences in the migrant economic condition before and after migration. presents the test results of the null hypothesis (H0) that there is no difference in migrants’ condition before and after migration against the alternative hypothesis (H1) that there is a difference. The results indicate there is a statistical significant difference in the average income, expenditure and savings of migrants before and after migration at the 1% significance level. Thus, there is a statistical difference in the mean income, expenditure, and savings of migrants between before migration and after migration. However, the negative sign of the coefficients indicates that migrants are better off after migrating to the cashew centres than before migration. For income, the value of the mean difference (381.329) implies that, on average, a migrant household earns a monthly income of GHS 381.33 more after migration than before; and, on average, a migrant household makes a monthly average expenditure of GHS 257.88 and saves GHS 747. 91 more annually than it would before migration.

Table 4. Paired t-test result of the differences in migrants’ well-being before and after migration.

The household assets of the migrants were analysed to find out whether there has been a difference in the asset ownership of the migrant household before and after migration. The principal component analysis (PCA) approach of creating index was followed to create a single asset score (index) for the various household consumables assessed. However, the results indicated there is no statistical significant difference from the migrant household asset ownership before and after migration. From , the paired t-test results indicate insignificance at the 5% level of significance in the difference between the after and before migration asset of the migrant household. In other words, based on the test results (CI = [-0.177 0.177], t-value = -0.00) we failed to reject the H0, and therefore conclude that there is no difference in the asset ownership before and after migration. However, from the wealth distribution of the migrant households for before and after migration, there is a slight difference in the distribution of wealth across migrant household (). In each case (before and after) the proportion of households that fall into the bottom quartile (poorest) is almost the same as in the before migration (22.15%) and after migration (21.52). For the top quartile (richest) households there is 19.62% in both cases. This further confirms the findings of the t-test presented in .

Table 5. Migrants’ wealth distribution.

3.4. The impact of migration on migrants’ socio-cultural/political/economic conditions

The impact of migration, in general and specifically migration to the cashew growing centres, on the social condition of migrants were examined by using indicators such as community activity participation, marital status, leadership role, being a member of a social group, and involvement in decision making. Migrants were asked to indicate their involvement or participation in the social activities or functions.

The results () show that there is a significant difference at the 1% significant level in migrants’ social condition between before and after migration under all the social condition indicators employed except community activity participation, which is insignificant. On average, the level of involvement in a social group, taking a leadership role, being involved in decision making at the family, group and community levels, and migrants’ marital status is about 0.12, 0.06, 0.09, and 0.07 points higher in after migration than before migration. shows the results of the McNemar test of the individual components of marital status. The results indicate all the indicators are significant at 1% except divorced, which is significant at 5%. All the components show an increase from before to after migration.

Table 6. McNemar’s test result for migrants social condition.

For socioeconomic conditions of migrants at the cashew growing sector in the southern part of Ghana, we used indicators like education, portion of land owned, nature and ownership of accommodation, employment and occupation status of the migrant’s household. The result of the t-test shows that the mean acres of land owned by the migrant households and level of education of the household head or the representative differ from before and after migration at the 1% significance level. That is to say, on average, the acres of land owned and the level of education is 4.5 acres and 0.03 points higher than before migration.

presents the McNemar paired matched test of the various sub-components of the socioeconomic variables. For the education sub-components, it is only tertiary education level attainment that was revealed to be statistical significant at the 5% significance level. There is a statistically significant increase in the number of migrants who reported that they had attained tertiary level education qualification from before to after migration. Ten migrants (22.7%) who did not have tertiary eduaction qualification before migration reported they have tertiary qualification after migration. However, there is zero (0) or none who rported they had tertairy qualification before migration but affter migration they do not have it anymore This makes sense because once the education qualifiaction is attained it is not revoked (unless under some rare circumstances). The general implication here is that 44 out of the 158 (27.8%) sampled migrant respondents had tertiary education qualification. Among this number, 10 attained it after migration.

Table 7. McNemar’s test results for migrants socioeconomic conditions.

Regarding accommodation ownership status of the migrants, there is a statistically significant increase in the number of migrants who reported that they owned their accommodation from before to after migration. There are 34 (85%) migrants who did not own their accommodation before migrating but reported they own accommodation after migration: to the contrary, there are only seven (5.9%) migrants who did not own accommodation after migration but they own accommodation before migration. Comparing a migrant’s accommodation status as owned or rented against free or shared accommodation, the results indicated a significant increase in the number of migrants who reported they owned or rent their accommodation after migration than before migration: 76 migrants (79.2%) responded ‘No’ to the question on whether they owned or rented their accommodation (implying they share or have free accommodation) before migration; and three (4.8%) responded ‘Yes’to owning or renting accommodation after migration.

For the occupation migrants engage in, the test indicates a statistical significant difference in all the occupation measures used for the assessment. The results show that there is an increase in the number of migrants who reported that they work (main occupation) as public/civil service servants and farmers in after than before migration. However, there is a decrease in the number of migrants who reported that they work as artisans, traders, and others between before and after migration. For example, three respondents (6%) indicated trading was not their main occupation before migration but became their occupation after migration whereas 28 migrants (18.3%) then said trading was their main occupation before migration but after migration they are no longer traders. Concerning the unemployemt status among the migrants, there is a statistically significant decrease in the number of migrants who reported that they were unemployed from before to after migration. Suprisingly, none of the migrant reported on their unemployemt status before migration. However, 17(10.8%) indicated that they were unemplyed after migration but did not report on their unemployment status before migrating to the cashew center.

Regarding the challenges migrants face concerning land, only eleven 11(7%) indicated they are losing their lands. Less than half (32.9%) of the respondents indicated they are members of cashew farmers association. Because migration has improved the health, social, and economics of migrants at the cashew growing centre, almost all the respondents indicated they would encourage others who seek their advice on plans to migrate to the cashew growing centre to migrate (). This was confirmed during a one-on-one interview with a key informant at Tanoboase in the Techiman North District of the Bono East Region.

‘… I can say cashew work has helped me. I can’t say it has done me bad. It has helped a lot of people too and not me alone’ (a quote from a male migrant cashew farmer at Tanoboase during KII)

4. Discussion

The impact of migration on the well-being of migrants in cashew growing centres in Ghana is examined in this paper, specifically in terms of the demographic characteristics of the migrants and the effect of migration on their health, and economic and social conditions. The majority of the migrants were males, and almost 70% of them migrated when they were between 19 and 30 years of age, indicating that youth make up the majority of migrants. Additionally, the majority of the migrants migrated from the northern zone of Ghana, where issues of climate change in recent years have severely affected the livelihoods of people, particularly the smallholder farming households (FES & GAWU, 2014). The migration of the youth to cashew production centres confirm the findings of earlier studies on cashew production that concluded that cashew farming activities require physical strengthen (Wongnaa & Ofori, Citation2012). This finding signals that migrants at the cashew growing sector were pulled by the cashew business; the reason being is that even though cashew has been in Ghana since the 1960s, the business started becoming lucrative in the past two decades (Ackah et al., Citation2020; MoFA, Citation2010).

The study evaluated the impact of migration on the migrants’ health condition using the McNemar’s paired matching test, which was used to compare the exposure to diseases before and after migration. The results showed no statistical evidence to support a difference in exposure to diseases such as malaria, cholera, and typhoid before and after migration. However, there was statistical evidence to report differences in the exposure to chicken pox, infectious disease, and chronic disease before and after migration. The number of migrants who reported not suffering from these diseases increased after migration, indicating an improvement in their health condition. Thus, the morbidity rate of migrants to infection and chronic disease as well as chicken pox disease has reduced at the cashew growing centres. This may be so because of positive selection, where migrants who have strong immunity to disease migrate than those with poor health. Furthermore, cashew production improves the income and food and nutrition of the population living in the cashew growing centres (Yeboah et al., Citation2023) Based on this, even if migrants are not into the cashew business this may have a spill over effect on their health conditions. The distribution of the rate of chronic and infectious diseases across Ghana is uneven (GSS et al., 2015). According to WHO’s country profile of Ghana, the Northern Zone of Ghana has the highest rates of both chronic and infectious diseases. This, according to the report, is due to a number of factors including poverty, inadequate access to healthcare, poor sanitation, vector-borne diseases, etc (WHO, Citation2021). Poverty can lead to poor nutrition, inadequate access to healthcare, and poor living conditions, all of which can increase the risk of chronic and infectious diseases.

The results further showed that there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of migrants who practiced self-treatment after migration. Additionally, there was a decrease in the number of migrants who sought traditional healthcare services and visited the CHIPS compound for treatment after migration. Conversely, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of migrants who reported that they sought healthcare from the district hospital after migration. However, there was no significant impact on the overall health status of the migrants before and after migration. The findings of this study are in line with previous studies on migration and health. For example, a study by Tewolde et al. (Citation2021) found that migrants in Ethiopia had a better health status than non-migrants. Another study by Stenholm et al. (Citation2017) found that international migration had a positive impact on the health status of migrants. However, there is also evidence to suggest that migration can have negative impacts on health, particularly mental health (Chen et al., Citation2021). The findings, however, refute the claim by previous studies (e.g. Svensson et al., Citation2013) that migrant farmworkers are prone to poor health conditions due to exposure to chemicals and occupational injuries that result in various illnesses.

For economic conditions in the cashew sector, the study suggests that the cashew business has become lucrative in the past decade, which may explain the increase in migration to cashew growing centres. Cashew production increases income of the cashew farmers, which spills over to the general population of the cashew growing communities (Yeboah et al., Citation2023). An increase in the smallholder farmer income increases their purchasing power, and this has a positive impact on the economic activities in the area. This indirectly affects the migrant’s economic condition even if they are not directly involved in cashew production. This is supported by a study by Gyasi et al. (Citation2019), which found that cashew farming in Ghana had become an important source of income for many households. This explains why the study found a significant difference (increase) in migrant’s household income, and savings. The migrants earn more income at their respective migration centres relative to their destination. This confirms the establishment that economic factors including employment, income and agricultural wage are determinants of internal migration such as Al-Maruf et al. (Citation2022). With this relative improvement in the economic condition, they can afford quality food to improve their nutrition, and seek proper medical care so that they can build immunity against some of the diseases that hitherto they were suffering from; hence, the improvement in their health status.

The findings show a significant improvement in the migrants’ social condition when they migrated to the cashew centre compared to when they were at their home (origin). That is to say, migrants involve themselves in social groups, take leadership roles, and are involved in decision making in their family, social groups and community more at their migration centres than before they migrated. The findings further show that migrants’ marital status improves after migration in comparison to before migration. Migrants often build strong social networks in their new home to fill the vacuum created when they left their families and relocated to the new place. Migration may lead to loss of social connection at home region, however, migrants rebuild new relations at their destination through community activities and social groupings like migrants association, farmers association, northerners association, susu group etc. These networks can provide support and resources during times of need, and they can help migrants to integrate into their new communities. This has been confirmed in a study conducted by Amfo et al. (Citation2021) on the migrant labourers in the cocoa growing regions of Ghana. The study revealed that migrants use social grouping such as being a member of an association as social capital that influences their coping strategies due to changes in their environment and likely work challenges.

Migrants at the cashew growing centre have experienced an improvement in the socioeconomic condition after migrating to their current destination compared to when they had not migrated. Through migration to the cashew centres, migrants’ households are able to attain higher levels of education, and acquire lands. The findings indicated that there has been a significant difference in the socioeconomic condition, particularly land ownership and educational attainment of migrants between before migration and after migration. Similar findings revealed other socioeconomic variables the study employed such as accommodation, where many migrants at cashew centres are able to build or rent their accommodation as compared to the case of sharing accommodation with friends and other family members before migration. Migrant households that engage directly in cashew cultivation can use income earned to undertake housing projects or rent decent accommodation. The findings support those of Peprah et al. (Citation2018), Boafo (Citation2019) and Yeboah et al. (Citation2023). Notwithstanding, migration to the cashew sector has a positive influence on indicators like employment status. More migrants work as public/civil servants and farmers after migrating to their current destination at the cashew centres than their home region. The cashew business has improved migrants’ household income with which they can upgrade their skills through training and education; hence, gaining the ability to be eligible for employment in the public/civil service (formal) sector. However, migrants were more involved in occupations such as trading and artisan work before migration than after migrating.

5. Conclusion and implication

In conclusion, the study provides insights into the impact of migration on the well-being of migrants in cashew growing centres in Ghana. The study finds a notable improvement in the migrants’ health conditions after migration, particularly in the reduction of exposure to chicken pox, infectious diseases, and chronic diseases. This health improvement is attributed to positive selection, where migrants with stronger immunity are more likely to migrate. Economic conditions in the cashew sector contribute significantly to the well-being of migrants, with increased income, savings, and household prosperity observed. Socially, migrants experience enhanced social conditions, including increased involvement in social groups, leadership roles, and improved marital status. Migration fosters the formation of new social networks and associations, providing support and resources for migrants in their new communities. Moreover, the study highlights a positive impact on the socioeconomic condition of migrants, with improvements in education, land ownership, and employment status after migration.

To maximize the positive outcomes of migration and enhance the overall well-being of migrants, the study makes the following policy recommendations. Policymakers should encourage skill development programs and education opportunities for migrants, enabling them to qualify for a broader range of formal employment opportunities. Additionally, there is the need to strengthen healthcare services in cashew growing centres, focusing on preventive measures and addressing specific health challenges faced by migrants. Other measures including implementation of sustainable agricultural practice and regional development policies that address climate change challenges in the Northern Zone, aiming to improve livelihoods and reduce the necessity for migration are potential means to improve wellbeing of migrants. However, the study acknowledges that the well-being of migrants extends beyond these factors and calls for further research to investigate the impact of migration on other aspects of migrants’ lives, such as their psychological well-being.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The paper followed the ethics and consent to participate during the research work. The protocols for this study were approved by the University of Ghana, College of humanities ethical review board (Ethical approval No: ECH 011/20-21).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the field research assistants. I would also like to appreciate the study participants in the selected communities.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katherine Kaunza-Nu-Dem Millar

Katherine Kaunza-Nu-Dem Millar is a lecturer in the Faculty of Social Science, UDS, Tamale, Ghana. She holds a Master of Philosophy (MPHIL) in Culture and Development from the University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana. Her research interests are in Climate Change, Livelihoods, Gender, Ecosystem Services and Culture.

Paul Nayaga

Paul Nayaga holds a Master of Philosophy (MPHIL) in Economics and currently affiliated with the Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. His research interest is energy, environmental and health economics as well as sustainable development.

Philip Aniah

Philip Aniah is a lecturer in the department/faculty of sustainable development studies, University for Development Studies (UDS). He has a Ph.D in Development Studies focusing on environmental change and sustainability assessment. His research draws on both theoretical and pragmatic perspectives to examine human-nature interactions. His research interest includes climate change adaptation and resilience, landscape change, biodiversity, ecosystem services and livelihoods.

References

- Ackah, N. B., Ampadu-Ameyaw, R., Appiah, A. H. K., Annan, T., & Amoo-Gyasi, M. (2020). Awareness of market potentials and utilization of cashew fruit: perspectives of cashew farmers in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 26(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.9734/jsrr/2020/v26i330232

- Adamtey, R., Yajalin, J. E., & Oduro, C. Y. (2015). The socio-economic well-being of internal migrants in Agbogbloshie, Ghana. African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 19(2), 132–148.

- Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA). (2022). Final Evaluation of the Bono-Asante Atea (BAAT) Project.

- Akrofi, M. M., Akanbang, B. A., & Abdallah, C. K. (2018). Dimensions of regional inequalities in Ghana: assessing disparities in the distribution of basic infrastructure among northern and southern districts. International Journal of Regional Development, 5(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijrd.v5i1.12293

- Akyereko, Y. G., Wireko-Manu, F. D., Alemawor, F., & Adzanyo, M. (2022). Cashew apples in Ghana: Stakeholders’ knowledge, perception, and utilization. International Journal of Food Science, 2022, 2022, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2749234

- Al-Maruf, A., Pervez, A. K., Sarker, P. K., Rahman, M. S., & Ruiz-Menjivar, J. (2022). Exploring the factors of farmers’ rural – urban migration decisions in Bangladesh. Agriculture, 12(5), 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12050722

- Amfo, B., Osei Mensah, J., & Aidoo, R. (2021). Migrants’ satisfaction with working conditions on cocoa farms in Ghana. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(2), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-03-2020-0131

- Arthur-Holmes, F., & Busia, K. A. (2022). Women, North-South migration and artisanal and small-scale mining in Ghana: Motivations, drivers and socio-economic implications. The Extractive Industries and Society, 10, 101076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101076

- Awumbila, M. (2017). Drivers of migration and urbanization in Africa: Key trends and issues. International Migration, 7(8), 1–9.

- Bennett, B. M., & Underwood, R. E. (1970). 283. Note: On McNemar’s Test for the 2 * 2 Table and Its Power Function. Biometrics, 26(2), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529083

- Boafo, J. (2019). Expanding cashew nut exporting from Ghana’s Breadbasket: A political ecology of changing land access and use, and impacts for local food systems. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 25(2), 152–172.

- Cachero, K., Mollard, R., Semone, M., & MacKay, D. (2023). A clinically managed weight loss program evaluation and the impact of COVID-19. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1167813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1167813

- Chen, X., Hu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). The impacts of migration on mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 141, 151–161.

- Daniel, W. W., & Cross, C. L. (2018). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences. Wiley.

- Dubbert, C., Abdulai, A., & Mohammed, S. (2021). Contract farming and the adoption of sustainable farm practices: Empirical evidence from cashew farmers in Ghana. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 45(1), 487–509.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2014). 2010 Population and housing census. District analytical report. Techiman North District. https://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010_District_Report/Brong%20Ahafo/TECHIMAN%20NORTH.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS. (2023). Ghana 2021 population and housing census publications. Thematic report – Migration. https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/Thematic%20Report%20on%20Migration_09032022.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF International. (2015). 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) key findings. GSS, GHS, and ICF International.

- Gyasi, E. A., Tuffour, T., & Adzawla, W. (2019). Cashew production and household livelihoods in Wenchi Municipality of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography, 11(2), 63–79.

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tathman, R., & Black, W. (Eds.) (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hart, J. K. (2018). Migration and the opportunity structure: A Ghanaian case-study 1. In Modern Migrations in Western Africa (pp. 321–342). Routledge.

- Horne, J. R., Gilliland, J., & Madill, J. (2020). Assessing the validity of the past-month, Online Canadian Diet History Questionnaire II pre and post nutrition intervention. Nutrients, 12(5), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051454

- Ingo, R. (2015). Lecture notes. Department of biostatistics. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Kratz, F. (2020). On the way from misery to happiness? A longitudinal perspective on economic migration and well-being. Migration Studies, 8(3), 307–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny040

- MoFA. (2010). Agriculture in Ghana – facts and figures. Statistics, research and information directorate (SRID).

- Monteiro, F., Catarino, L., Batista, D., Indjai, B., Duarte, M. C., & Romeiras, M. M. (2017). Cashew as a high agricultural commodity in West Africa: Insights towards sustainable production in Guinea-Bissau. Sustainability (Switzerland), 9(9), 1–14.

- Olowoyeye, A. O., Musa, K. O., & Aribaba, O. T. (2019). Outcome of training of maternal and child health workers in Ifo Local Government Area, Ogun State, Nigeria, on common childhood blinding diseases: a pre-test, post-test, one-group quasi-experimental study. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 430. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4272-1

- Pembury Smith, M. Q., & Ruxton, G. D. (2020). Effective use of the McNemar test. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 74(11), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-020-02916-y

- Peprah, P., Amoako, J., Adjei, P. O. W., & Abalo, E. M. (2018). The syncline and anticline nature of poverty among farmers: Case of cashew farmers in the Jaman South District of Ghana. Journal of Poverty, 22(4), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2017.1419534

- Qin, H. (2010). Rural-to-urban labor migration, household livelihoods, and the rural environment in Chongqing Municipality, Southwest China. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38(5), 675–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-010-9353-z

- Stenholm, S., Vahtera, J., Kawachi, I., Pentti, J., & Kivimäki, M. (2017). Migration patterns and health status: A longitudinal analysis of a Finnish working-age population. Social Science & Medicine, 185, 95–103.

- Svensson, M., Urinboyev, R., Wigerfelt Svensson, A., Lundqvist, P., Littorin, M., & Albin, M. (2013). Migrant Agricultural Workers and Their Socio-economic, Occupational and Health Conditions – A Literature Review. (SSRN Working Papers series). Social Science Research Network. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2297559.

- Tewolde, S. M., Yadeta, G., Mekonnen, A., & Hussen, R. (2021). Health status of internal migrants in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–12.

- Van der Geest, K. (2011). North‐South migration in Ghana: what role for the environment? International Migration, 49(s1), e69–e94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00645.x

- Wongnaa, C. A., & Ofori, D. (2012). Resource-use efficiency in cashew production in Wenchi Municipality, Ghana. AGRIS on-Line Papers in Economics and Informatics, 4(2), 73.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Ghana country profile. https://www.afro.who.int/countries/ghana/topic/health-topics-

- Yeboah, P. A., Guba, B. Y., & Derbile, E. K. (2023). Smallholder cashew production and household livelihoods in the transition zone of Ghana. Geo: Geography and Environment, 10(1), e00120. https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.120