?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the prevalence of transparency and accountability in Brazilian National Sports Organizations. Transparency is an organization’s ability to acquire and disseminate accurate and relevant information and knowledge. Accountability refers to an organization’s duty or obligation to provide an account or explanation of their actions. Both transparency and accountability are associated with modernization and good governance. In this study, we collected annual indicators of transparency and accountability between 2015 and 2021 for 34 Brazilian National Sports Organizations. Data were analyzed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). The three key findings of the research were as follows: (1) transparency and accountability increased over the years; (2) there was selective growth in transparency and accountability dimensions; and (3) there was stagnation for audit (AUD), an accountability indicator. These findings suggest that the modernization of Brazilian National Sports Organizations is underway, but there is still potential for improvement.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

The financial backing that National Sports Organizations (NSOs) in Brazil receive from government sources necessitates rigorous adherence to transparency and accountability principles. Transparency is a crucial mechanism that broadly enhances accountability and governance more broadly (Hood, Citation2010). Accountability is conceptualized as the ‘duty to provide an account of those actions for which one is held responsible’ (Gray et al., Citation1996, p. 38). The primary objective of this study was to scrutinize the evolution of transparency and accountability in Brazilian NSOs from 2015 to 2021.

Over the past several decades, international and national sports organizations have refined their governance structures to align with increasing trends of commercialization and professionalization as part of a wider modernization process (Furtado et al., Citation2022; Ingram & O’Boyle, Citation2018). In this context, NSOs in Brazil have complied with governmental directives that aim to bolster governance practices, thereby improving efficiency, safeguarding integrity, and combating corruption (Chappelet, Citation2016; Gardiner et al., Citation2017). Accountability and transparency are foundational to the notion of good governance and have been supported by extensive empirical evidence (Caetano et al., Citation2024; Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2013; Parent & Hoye, Citation2018; Thompson et al., Citation2022).

Effective governance not only fosters stakeholder trust, but also optimizes resource allocation and enhances service delivery (Kosack & Fung, Citation2014). Guided by this perspective, this study relies on data reported by Brazilian NSOs to underline the collective advantages of transparency and accountability. The central research question is, ‘To what extent have transparency and accountability evolved in Brazilian NSOs between 2015 and 2021?’

Brazil occupies a central stage in the global sports sector, hosting a myriad of international events underpinned by significant government investment. This study spans a period from the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a timeframe during which Brazilian NSOs underwent considerable reorganization (Queiroz, Citation2022). The pandemic has posed unparalleled challenges, particularly given the extensive geographical dimensions of Brazil, leading to numerous cancellations, postponements, or annulments of events (Beims & Schmitt, Citation2020a). To mitigate these challenges, the Brazilian Olympic Committee issued guidelines for the practice of Olympic Sports during the pandemic (COB, Citation2020).

The current investigation is noteworthy for its longitudinal and evaluative exploration of transparency and accountability in sports organizations, responding to existing academic calls for more rigorous research in this area (Caetano et al., Citation2024; Parent & Hoye, Citation2018; Parnell et al., Citation2018; Winand et al., Citation2021). This study is important for both theoretical and practical reasons. Studies have explicitly focused on transparency and accountability in sports organizations (e.g. Ghai & Zipp, Citation2021; Havaris & Danylchuk, Citation2007; Král & Cuskelly, Citation2018). Knowing the extent to which accountability and transparency are improving is important because of their consequential impacts on effective governance, enhancing stakeholder trust and confidence, more efficient resource allocation, and improved service delivery (Auger, Citation2014; Muñoz et al., Citation2023; Schnackenberg et al., Citation2021). For both Morales and Schubert (Citation2022) and Thompson et al. (Citation2022), transparency and accountability are routinely associated with good practice.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The following section provides an overview of Brazilian sport. This is followed by a literature with subsections devoted to modernization of sport, good governance in sport, and more specifically, the concepts of accountability and transparency. Then, we describe the methods. The results section then provides an overview of the findings. We complete the article with a discussion, closing the article with limitations and suggestions for future research.

Research context

Brazil is a federal presidential Republic. In addition to the federal government, there are 26 states and one federal district. Brazil is the eighth-largest economy in the world but has suffered recovery from economic recessions in 2015 and 2016. 2023 the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) has a growth projection of gross domestic product (GDP) of 1,4%, and for 2024, the forecast is for an increase of 2.0% (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, Citation2023).

Within the Brazilian government, sports is the responsibility of the Ministry of Sports (Ministério do Esporte, Citation2023a). Each state government and municipal authority has a secretary (or department) responsible for sports. The main federal statute is known as Pelé Law (Law No. 9,615/98). Within this Law, Article 13 mandates a National Sports System and Article 14 subsequently states that the COB, CPB, CBC, CBCP, and national sports administration entities (ENADs/NSOs) (or sports practice affiliated or linked to them) constitute a specific subsystem of the National Sports System (Brasil, Citation1998). A more detailed overview of the law, history, and organization of Brazilian sports is available elsewhere (Mezzadri et al., Citation2015).

The Ministry of Sports is responsible for coordinating the national sports development policy and implementing actions to promote social inclusion through sports, aiming to provide the population with free access to physical activities, well-being, and human growth. Additionally, the ministry is responsible for creating policies and incentives for high-performance sports (Ministério do Esporte, Citation2023a). Among the most well-known policies of the Ministry of Sports are projects such as the Athlete Grant (Bolsa Atleta), the Lottery Law Agnelo/Piva Bill (Lei Agnelo/Piva), the Sports Incentive Law (Lei de Incentivo ao Esporte), the Second Half Program (Programa Segundo Tempo), the Armed Forces in Sport (Forças no Esporte), and the Brazilian Doping Control Authority (Autoridade Brasileira de Controle de Doping). These projects are conducted by different secretariats: the National Secretariat for Amateur Sports, Education, Leisure, and Social Inclusion; the National Secretariat for High Performance Sports; the National Secretariat for Parasports; and the National Secretariat for Football and Defense of Fan Rights (Ministério do Esporte, Citation2023b).

The Brazilian Olympic Committee (BOC; Portuguese: Comitê Olímpico do Brasil – COB) is the highest authority in Brazilian sports and the governing body of Brazilian Olympic sports. Founded in 1914, the official activities began in 1935. The BOC was regulated by Law 3.199/41. Brazil first participated in the 1920 Olympic Games. Brazil has participated in every Summer Olympic Games since then, except for the 1928 Games, winning 150 medals in 18 different sports as of 2020.

There are currently 56 organizations affiliated with the BOC, 35 of which are Olympic ENAD/NSOs, and 21 organizations are between recognized and affiliated, but not Olympic sports (COB, Citation2021a). The members of the ENAD/NSOs are typically state confederations from all 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District. The BOC is a powerful organization in Brazil. The ‘Agnelo/Piva Law’ (no 10.264 of 2001) allocates a percentage of the Federal Lottery to the Ministry of Sport. The Ministry of Sports shares money with the BOC for allocation to NSOs. The BOC approves the work plans and annual budgets submitted by NSOs (Almeida & Marchi Júnior, Citation2011; Ribeiro, Citation2012).

To be eligible for BOC funds, an NSO must comply with the ‘Pelé’ law, Law 13.756 (2018) and its amendments contained in Law 14.073 (2020). As mandated in the ‘Pele Law’, NSOs must also provide the ‘clearance certificates’ from the National Institute of Social Security (INSS) and Severance Indemnity Fund for Employees (FGTS). Once eligibility has been established, funds are allocated based on previous performance at the Olympic and World Championship events, as well as two governance-related criteria: Accountability; and the Management, Ethics and Transparency Program (GET) (COB, Citation2021c). Half of the available funds were equally distributed to all eligible NSOs. The balance is distributed based on merit. Merits are determined by 13 distribution criteria (11 sports performance and 2 governance) (COB, Citation2021d). The two governance-related criteria accounted for between 15% and 17% of the total weight (COB, Citation2021c, Citation2021d). The distribution is audited by the Federal Audit Court (TCU) and Federal Comptroller General (CGU) (Brasil, Citation2001; COB, Citation2021e).

Between 2015 and 2021, approximately R$7.816 billion was invested in Brazilian sport under ‘Agnelo/Piva’ law. This included approximately R$ 1.8 billion (or approximately US US$334 million to the BOC (Caixa, Citation2022). Public funding carries transformative expectations regarding the transparency and accountability of these organizations.

In summary, the Brazilian government allocates financial resources to NSOs based on their transparency and accountability. For many Brazilian NSO’s, government funding provides the majority of their revenue (Almeida & Marchi Júnior, Citation2011; Furtado et al., Citation2022). Brazilian NSO’s have a significant financial incentive to improve their governance, especially transparency and accountability.

Literature review

In this section, we present accountability and transparency as two principles of good governance and modernization of sports organizations.

Modernization of sport

Modernization is associated with economic and productivity growth as well as an increase in knowledge and organizational capability (Charlton & Andras, Citation2003). Modernization is closely linked to the processes of professionalization (Sam et al., Citation2018; Tacon & Walters, Citation2016) and organizational improvement (Finlayson, Citation2003), Modernization reflects growing structural complexity, improved knowledge management, and increased sophistication of human activities (Inglehart, Citation2021). Organizations that pursue modernization have ‘an intense awareness of change and innovation’ (Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2007).

Hence, the pursuit of modernization behoves sports organizations to develop rational and scientific management processes, implement evidence-based policies and processes, and embrace formal evaluations (Furtado et al., Citation2022). Previous research on the modernization of Brazilian sports organizations suggests that most Brazilian Olympic NSO’s have a moderate to weak commitment to modernization principles (Furtado et al., Citation2022). Specifically, the three indicators correlated strongly with modernization. The indicators were 1) whether the organization uses key performance indicators (KPÌs) 2) the specification of roles and functions for staff and managers of the organization; and 3) the clarity organizations strategic focus.

Good governance in sport

Modernization is connected to governance and the pursuit of good governance. Furtado et al. (Citation2022, p. 17) found that organizations with a ‘high stage of modernization tend to present better practices of governance’.

The definitions of governance in the context of sports vary and reflect researchers’ interests (Dowling et al., Citation2018). In this sense, Hums and MacLean (Citation2017) define governance as the exercise of power and authority within a sports organization, including political issues, criteria, and regulation of power. O’Boyle (Citation2012) refers to governance as a process of granting power and verifying the performance, management, and leadership of an organization. Here, governance permeates all levels of an organization. Governance refers to how organizations are directed, controlled, and regulated (Bevir, Citation2011). Corporate governance refers to a system of rules, practices, and processes by which a company is directed and controlled (Henry & Lee, Citation2004). It encompasses the relationships among a company’s management, board of directors, shareholders, and other stakeholders, and sets out the guidelines and limits within which the company is expected to operate (O’Boyle, Citation2012; Pielke et al., Citation2020).

Increased interest in the governance of sports organizations is a response to diverse types of on-field and off-field governance failures in sports (Pielke et al., Citation2020). Good governance in sports is largely premised on the ideology of New Public Management (NPM). NPM emphasizes efficiency, budget cuts, accountability for performance, audits, customer focus, strategic planning and management, and competition (Girginov, Citation2022). Good governance is essential for improving and commercializing sports organizations (De Dycker, Citation2019). In their pursuit of good governance, sports organizations have produced many codes of conduct (Geeraert, Citation2022; Girginov, Citation2022; Pielke et al., Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, many government agencies, such as Australia, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, have developed explicit principles of good governance for their NSÓs (Geeraert, Citation2022). The European Council established an expert group on good governance, which later facilitated a declaration of commitment to good governance by European sports organizations (Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2019; De Dycker, Citation2019).

Research from many countries emphasizes the relevance of transparency and accountability to good governance. Urdaneta et al. (Citation2021) linked transparency to the provision of accurate information and increased accountability. Ghai and Zipp (Citation2021) bracketed transparency and accountability under the theme of communication problems, one of the five governance hurdles confronting BCCI. Morales and Schubert (Citation2022) criticized North American professional sports leagues for their lack of transparency, specifically the absence of publicly available statutes and constitutions. Tóth and Mátrai (Citation2023) reflected on Hungarian sports financing and observed that the presence of integrity, transparency, and accountability in sports organizations enhances their ability to positively impact wider society. Muñoz et al. (Citation2023) studied Catalonian federations and recommended greater emphasis on transparency and accountability to promote stakeholder confidence. In Catalan, Solanellas et al. (Citation2024) argued that accountability and transparency should be prevalent in organizations, regardless of size. Collectively, these studies emphasize transparency and accountability as omnipresent principles of good governance.

Transparency

There are many definitions of transparency (Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). Schnackenberg and Tomlinson (Citation2016) defined transparency as ‘the perceived quality of intentionally shared information from a sender’ (Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). Hood (Citation2010) considers transparency and accountability are linked - either as ‘Siamese twins’ or as an ‘awkward couple’. This complex relationship shapes the discourse and practices surrounding transparency in modern sports organizations. Many authors associate transparency with the accessibility, availability, visibility, and observability of information (Bernstein, Citation2012; Granados et al., Citation2010; Kaptein, Citation2008). Organizations should make available and publish all information that is of public interest and not just that required by laws and regulations (ASOIF, Citation2016; Henry & Lee, Citation2004). Transparency should extend beyond financial aspects (Saraite-Sariene et al., Citation2020). Transparency impacts how both internal and external stakeholders perceive the credibility of an organization and its directors (Geeraert, Citation2015; Král & Cuskelly, Citation2018). Transparency is a three-dimensional construct underpinned by perceived information disclosure, clarity, and accuracy (Schnackenberg et al., Citation2021; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016).

Disclosure

Disclosure is the process of providing stakeholders with information on a company’s operations, financial performance, and other areas of corporate responsibility. The act of revealing information extends beyond mere openness (Hood, Citation2010). Disclosure is a key component of corporate governance because it provides stakeholders with insight into company performance. Disclosure is the extent to which information is released rather than hidden (Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016; Williams, Citation2008). There is a consensus that perceived disclosure is highly correlated with perceived transparency (Schnackenberg et al., Citation2021). Disclosures are more than merely revealing financial data. Disclosure should also incorporate ‘strategic (e.g. strategic planning), structural (e.g. organizational charts, membership relationships), performance (e.g. goals and performance indicators), and governance policies (e.g. code of ethics)’ (IBGC, Citation2015; Mezzadri et al., Citation2018).

Clarity

Clarity describes the extent to which a company’s operations, policies, and decisions are transparent and understandable to stakeholders. Clarity ensures that all stakeholders remain informed about a company’s activities and decisions (Fox, Citation2007). The disclosed information must be clear and easy to understand in order to be considered transparent (Fox, Citation2007; Street & Meister, Citation2004). Therefore, more information is not necessary to achieve clarity. In this sense, Briscoe and Murphy (Citation2012) suggest that information should be simple. The key to assessing clarity is whether the information creates understanding (Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016).

Accuracy

To be considered transparent, all disclosed information must possess content validity (Fox, Citation2007; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). Accuracy is also linked to the reliability of disclosed information (Walumbwa et al., Citation2011). In this sense, accuracy is related to the disclosure and clarity of the published content, dealing with the validity of the content and not the quantity of information, as quality information is more confident (Angulo et al., Citation2004; Hood, Citation2010). The information need not be exactly correct ex-post to be transparent but should accurately reflect the expected content validity (Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). Information accuracy is crucial for workplace transparency (Bernstein, Citation2012; Fox, Citation2007).

Accountability

Accountability is often used in conjunction with transparency, democracy, efficiency, and integrity (Ball, Citation2009; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Grant & Keohane, Citation2005; Khotami, Citation2017; Winand & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2019). According to Tóth and Mátrai (Citation2023) integrity, transparency, and accountability are important principles for public funding and should be top priorities in sports.

An oft-cited definition of accountability is ‘the duty to provide an account (by no means necessarily a financial account) or reckoning of those actions for which one is held responsible’ (Gray et al., Citation1996, p. 38). Importantly, accountability incorporates the responsibility to perform certain actions and the responsibility to account for those actions (Gray et al., Citation1996). Accountability compares ‘events’ against ‘prescriptions’ for what should occur or should have occurred (Schlenker et al., Citation1994). Employees and organizations must always be accountable for their actions, fully assuming that the consequences are solely responsible for their acts and omissions (Hood, Citation2010; Khotami, Citation2017; Molina & Ribeiro, Citation2017).

Sports organizations must be accountable for government investments. Sports organizations must demonstrate that government investment has been expended in a manner consistent with its stated aims, and that it has produced the desired results (Geeraert, Citation2015; Geeraert et al., Citation2014).

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal quantitative study (Creswell, Citation2013). This approach allows researchers to identify changes over an established period (Veal & Darcy, Citation2014). This longitudinal study measured movements in transparency and accountability in Brazilian NSOs between 2015 and 2021. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Physical Education Department at the Federal University of Paraná (Legal Opinion CEP/UFPR: 5.414.934 with CAAE: 88770618.4.0000.0102).

The year 2020 was excluded intentionally because the COVID-19 pandemic has compromised normal NSO operations (Pitanga et al., Citation2020). The organization of sports events is complex (Beims & Schmitt, Citation2020a). The Brazilian Paralympic Committee suspended face-to-face activities for all programs and projects (Cardoso et al., Citation2020). The Brazilian Olympic Committee created a Guide to the Practice of Olympic Sports in the COVID-19 context, which brings procedures and recommendations as a way to help NSOs and athletes support the resumption of sports activities in the country (COB, Citation2020). Many of these events were canceled or postponed (Beims & Schmitt, Citation2020b). All this occurred within widespread public health interventions, which constrained both social and economic impact activities (Freitas et al., Citation2020). The pandemic has also compromised the ability to collect data from NSOs.

Sample

The sample comprised all 34 Brazilian NSOs that contributed athletes to the BOC teams in Rio 2016, Pyeongchang 2018, and Tokyo 2020 (COB, Citation2021b). The number of BOC-NSOs changed throughout the data collection process because sports were added to and excluded from the Olympic program. There were 29 organizations were included in the data collection. The sports associated with the organizations were: Rugby, Athletics, Badminton; Basketball; Boxing; Canoeing; Cycling; Aquatic sports; Snow sports; Ice sports; Fencing; Gymnastic; Golf; Handball; Equestrianism; Hockey; Judo; Weightlifting; Modern Pentathlon; Rowing; Taekwondo; Tennis; Table Tennis; Archery; Shooting; Triathlon; Sailing; Volleyball; and Wrestling. The NSOs for Surfing Skateboard, Baseball, Softball, Karate, and Climbing first contributed data in 2018. The Football organization was not included in the data because, unlike other organizations, it does not receive resources via the Lottery Law.

Data collection, instrument, and procedures

The Sou Do Esporte (SDE) is a non-profit organization that promotes good governance as well as social and environmental responsibility. Since 2015, the SDE has been awarded an annual ‘Governance Award Sou do Esporte’ to five NSOs. The award criteria reflect five governance indicators: transparency, equity, accountability, institutional integrity and modernity. The SDE evaluates data/reports submitted by the NSO to the Ministry/BOC as part of their compliance with the Pele Law. The data was provided by the NSOs in the knowledge that it would be used for both the awards and an associated research study conducted by researchers at the Federal University of Paraná. The data contained no personal information. Given the absence of personal data, we did not seek informed consent. In 2017, the Sport Intelligence Research Institute (IPIE) partnered with the SDE to collect and analyze governance-related information. The IPIE is an institute at the Federal University of Paraná with over 10 years of research experience related to public policies and governance in Brazilian sports. In 2020, the Governance Award was not awarded due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Furtado et al., Citation2022).

Thus, a complete survey instrument has evolved. Starting in 2015, with 105 items, the survey increased in subsequent years: 2016 (111 items), 2017 (135 items), 2018 (156 items), 2019, and 2021 (156 items). In this study, the number of transparency and accountability items has evolved. The numbers of transparency items for the six surveys were 24, 27, 36, 45, 45, and 45. The number of accountability items was 13, 14, 18, 21, 21, and 21, respectively. These modifications reflect the desire to use the most contemporary transparency and accountability indicators as well as changes in Brazilian legislation.

The 66 transparency-accountability items were derived from several sources, including the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (IBGC), the UK Sport for Good Governance Code, Agenda 2020-IOC, and the organization Play the Game with National Sports Governance Observer (NSGO) indicators (Brasil, Citation1998; Geeraert, Citation2015, Citation2018; Geeraert et al., Citation2014). Additional indicators were designed to reflect engagement with Brazilian legislation (e.g. Pelé law).

Appendix 1 provides the items and their dimensions. Transparency items (n = 45 in 2021) reflect four dimensions: Publication of Financial Documents (six items), Appointments and Reports (six items), internal controls (three items), and Access to Information and Files (30 items). The accountability items (n = 21 in 2021) reflected five dimensions: Approval Format (AF) (three items), Audit (AUD) (two items), Statement/Demonstratives (SD) (four items), Performance of the Fiscal Council (PFC) (nine items), and Internal Controls (IC) (three items), with a total of 21 items. These dimensions were developed based on statutes, general meeting reports, board meeting reports, annual reports, financial statements, and other available documents. Consistent with other assessments of good governance in sports organizations (Geeraert, Citation2018), organizations were considered to have complied (one point) or not complied (zero points) with the criteria. The total score was calculated for each dimension. Next, we calculated the score for each dimension by aggregating items. Ultimately, we standardized the scores to between zero and one, ensuring that each dimension held equal significance in the analysis. Standardization takes information about the mean and standard deviation of a variable and produces a value corresponding to each original value that specifies the position of this original value within the original distribution of the data. A general validation of the consistency of the measurement system was conducted. The Cronbach’s alpha test was used to assess the consistency of the measurement model (Cronbach, Citation1951). The test shows a value of 0.90 on standardized items. Organizations that receive public funding are legally required to publish financial reports on their websites no later than the first semester (July) of the following year. All data were collected after this period in the following semester.

Data were collected by four independent researchers, each with advanced qualifications in sports management. These researchers underwent standardized training to ensure consistency in data collection. Furthermore, to ensure inter-rater reliability, a subsample of the data was reviewed by at least two researchers and discrepancies were resolved collaboratively. To begin the analysis, the researcher noted the date and time at which they started and finished the analysis. This was done to ensure that the analysis was not confounded by updated websites or other written materials. Two researchers collected data related to transparency, and two related to accountability. The data required extensive work owing to the differences between the NSO websites. Each NSO has its own website with different pages containing transparency and accountability information. NSOs are required to publish their financial reports, but the manner in which they do so is not prescribed.

Data analysis

Based on previous approaches (Geeraert, Citation2015), we developed formulas to evaluate transparency and accountability. We first determined the value of each dimension by calculating the number of ‘yes’ values using the Excel formula (COUNT.IF), then dividing this value by the number of items from each dimension, and then multiplying by 10. For example, calculations for the six transparency items within the Publication of Financial Documents (PFD) are presented below.

To calculate the score for a single indicator, we multiply the value of each dimension by the number of items for each dimension. We then summed the value of each dimension and divided it by the number of items for each indicator. The formula for Publication of Financial Documents (PFD) (six items), Appointments and Reports (AR) (six items), Internal Controls (IC) (three items), and Access to Information and Files (AIF) (30 items). is presented below.

The total score, based on transparency and accountability, was calculated over the indicator score and the number of items from the survey. Transparency has 45 items and accountability has 21 items. Each indicator score was multiplied by the total number of items, and then both indicators were summed and divided by the total number of survey items.

For example, transparency has a score of 7,1 based on preview calculation and following the same equation, accountability has a score of 7,6 which means (7,1x45) and (7,6x21). Then, all indicators were summed and divided by the number of items in the instrument. Finally, we find that the general score of good governance is related to transparency and accountability. This means that one Brazilian NSO has a total score of 7.3 in good governance related to transparency and accountability in one year.

Prior to inferential analyses, we checked the normality of the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Despite the non-parametric distribution, we generated the mean and standard deviation values to facilitate interpretation of the results. Categorical variables are described as absolute and relative frequencies. To compare the annual scores for transparency and accountability, we employed Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). GEE allows for the inclusion of non-parametric dependent variables using gamma distribution. The main effect was tested using the scores, both individual and cumulative, as dependent variables and the years as a repeated measure. When differences across years were observed, a post-hoc comparison was used to identify where the differences existed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.

Results

Using the GEE for longitudinal count data, the impact of the indicators achieved on some dimensions over the years has considerable effects. GEE with Gamma with a log link function was used to estimate the difference in dimension scores across different years. The GEE with Gamma with a log link function was used because the outcome was positively skewed (not normally distributed). In our case, GEE was suitable for examining longitudinal data characterized by relatively limited between-subject variability. The results are presented sequentially from the global good governance score through transparency and accountability indicators to their respective dimensions.

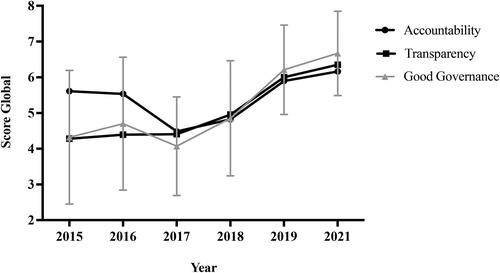

The average values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the global scores for ‘good governance’, ‘transparency’, and ‘accountability’ over the years are shown in . GEE analysis identified a statistically significant difference in the global "good governance" score over the years (p = 0.001). The post-hoc analysis showed no differences in global scores between 2015 and 2016, 2017, and 2018 (p > 0.05). However, an increase in the global score was observed when comparing 2015 (4.75; 95% CI 4.08–5.53) with 2019 (5.94; 95% CI 5.55–6.37; p = 0.02) and 2021 (6.16; 95% CI 5.67–6.68; p = 0.02).

Regarding the transparency score, a statistically significant difference was observed over the years (p = 0.001). The post-hoc analysis showed no differences in the scores between 2015, 2016, and 2017 (p > 0.05). An increase in the overall transparency score was observed when comparing the year 2015 (4.28; 95% CI 3.74–4.89) with the years 2018 (4.95; 95% CI 4.45–5.51; p = 0.017), 2019 (6.00; 95% CI 5.55–6.48; p = 0.001) and 2021 (6.35; 95% CI 5.97–6.75; p = 0.001).

Regarding the accountability score, a statistically significant difference was observed over the years (p = 0.001). post-hoc analysis showed differences only between 2015 and 2017 (5.61; 95% CI 4.83–6.51; p = 0.06). In addition, the year 2017 showed differences between the years 2016 (5.53; 95% CI 4.93 to 6.21; p = 0.001), 2019 (5.89; 95% CI 5.42–6.41; p = 0.001), 2021 (6.16; 95% CI 5.61–6.76; p = 0.001).

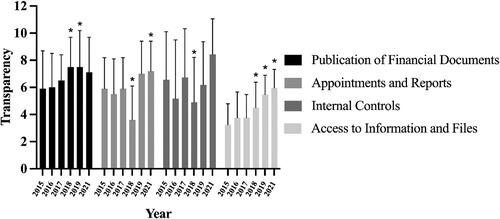

Having shown the differences in the global scores for good governance, transparency, and accountability, we now turn to the dimensions compared over the years. All the mean and standard deviation data from the dimensions of the transparency indicator are presented in . As shown in , differences between the years were observed. Additionally, the mean scores of all dimensions of the transparency indicator show the highest for Internal Controls (8.43 ± 2.63) in 2021 and the lowest for Access to Information and Files (3.24 ± 1.55) in 2015 among all dimensions.

For transparency in Publication of Financial Documents (PFD), a statistically significant difference was observed over the years (p = 0.003). post-hoc analysis showed no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2016, 2017, and 2021 (p > 0.05). An increase in the global PFD score was observed in 2015 (6.29; 95% CI 5.48–7.22), 2018 (7.72; 95% CI 7.15–8.34; p = 0.002), and 2019 (7.77; 95% CI 7.02–8.60; p = 0.008).

In the Appointments and Reports (AR) dimension, a statistically significant difference was observed over the years (p = 0.001). post-hoc analysis showed no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2016, 2017, and 2019 (p > 0.05). An increase in the global AR score was observed when comparing 2015 (6.07; 95% CI 5.37–6.86) with 2018 (3.80; 95% CI 3.05–4.77; p = 0.001) and 2021 (7.20; 95% CI 6.51–7.97; p = 0.040).

The Internal Controls (IC) dimension showed a statistically significant difference over the years (p = 0.001). post-hoc analysis showed no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2016, 2017, 2019, and 2021 (p > 0.05). An increase in the global IC score was observed when comparing 2015 (7.60; 95% CI, 6.68–8.64) with 2018 (5.95; 95% CI, 5.07–6.98; p = 0.034).

In the Access to Information and Files (AIF) dimension, it was possible to observe a statistically significant difference over the years (p = 0.001). The post-hoc analysis showed that there were no differences in the scores between 2015, 2016, and 2017 (p > 0.05). An increase in the global AIF score was observed when comparing the year 2015 (3.35; 95% CI 2.87–3.92) with the years 2018 (4.64; 95% CI 4.10–5.26; p = 0.001), 2019 (5.47; 95% CI 5.02–5.96; p = 0.001) and 2021 (5.95; 95% CI 5.52–6.42; p = 0.001).

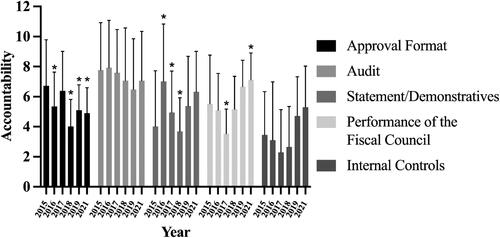

The accountability indicator is represented by all the mean and standard deviation data from the accountability dimension in . As shown in , differences between the years were observed. Additionally, the mean scores of all dimensions of the accountability indicator showed the highest Audit (7.93 ± 3.14) in 2016 and the lowest for Internal Controls (2.30 ± 2.83) in 2017 among all the dimensions.

Regarding accountability dimensions, the Approval Format AF dimension showed a statistically significant difference between the years (p = 0.001). The post-hoc analysis showed that there were no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2017 (p > 0.05, for all comparisons). An increase in the global AF score was observed when comparing the year 2015 (7.22; 95% CI 6.34–8.22) with the years 2016 (5.74; 95% CI 5.10–6.45; p = 0.002), 2018 (4.26; 95% CI 3.78–4.82; p = 0.001), 2019 (5.09; 95% CI 4.56–5.69; p = 0.001) and 2021 (4.90; 95% CI 4.37–5.49; p = 0.001). In addition, the year 2017 showed differences between the years 2016 (5.74; 95% CI 5.10–6.45; p = 0.016), 2018 (4.26; 3.78–4.82; p = 0.001), 2019 (5.09; 95% CI 4.56–5.69; p = 0.001), and 2021 (4.90; 95% CI 4.37–5.49; p = 0.001).

In the Audit (AUD) dimension, there was no statistically significant difference between the years (p > 0.501).

In the Statement/Demonstratives (SD) dimension, a statistically significant difference was observed over the years (p = 0.001). The post-hoc analysis showed that there were no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2019 and 2021 (p > 0.05, for all comparisons). An increase in the global SD score was observed when comparing the year 2015 (6.48; 95% CI 5.48–7.66) with the years 2016 (8.13; 95% CI 7.14 to 9.25 p = 0.005), 2017 (5.51; 95% CI 4.71–6.45; p = 0.044) and 2018 (4.03; 95% CI 3.39–4.79; p = 0.001).

In the performance of the Fiscal Council (PFC) dimension, a statistically significant difference was observed over time (p = 0.001). post-hoc analysis showed no differences in the scores between 2015 and 2016, 2018, and 2019 (p > 0.05). An increase in the global PFC score was observed when comparing 2015 (6.15; 95% CI 5.19–7.29) with 2017 (3.66; 95% CI 3.14–4.25; p = 0.001) and 2021 (7.12; 95% CI 6.56–7.73; p = 0.049). In addition, the year 2017 showed differences between all the years 2016 (5.46; 95% CI 4.74–6.29; p = 0.001), 2018 (5.48; 95% CI 4.90–6.13; p = 0.001), 2019 (6.66; 95% CI 6.11–7.27; p = 0.001), 2021 (7.12; 95% CI 6.56–7.73; p = 0.001).

The Internal Controls (IC) dimension showed a statistically significant difference over the years (p = 0.022). The post-hoc analysis showed that there were no differences in the scores between 2015 and all the other years (p > 0.05, for all comparisons), only from 2016 vs. 2018, 2018 vs. 2021, and 2019 vs. 2021. An increase in the global IC score was observed when comparing 2016 (6.42; 95% CI 5.05–8.17) with 2018 (4.49; 95% CI 3.73–5.41; p = 0.025). In 2018 (4.49; 95% CI 3.73–5.41) with the year 2021 (5.62; 95% CI 4.84–6.53; p = 0.037). Also, in 2019 (4.99; 95% CI 4.24–5.88) with the year 2021 (5.62; 95% CI 4.84–6.53; p = 0.011).

Discussion

This study aimed to measure the transparency and accountability of Brazilian NSOs between 2015 and 2021. The three key findings of the research are as follows: (1) transparency and accountability increased over the years; (2) selective growth in transparency and accountability dimensions; and (3) Stagnation for Audit (AUD), an accountability indicator.

Transparency and accountability are characterized by an upward trend. This finding aligns with the incentives provided to Brazilian NSOs to improve their practice. This upward trajectory can be attributed to the legal mandates in Brazil that require these improvements, backed by the threat of funding cessation in the case of non-compliance. Additionally, the influence of the Brazilian Olympic Committee (BOC) and its criteria established by the GET Program played a pivotal role in this positive shift.

While overall transparency and accountability have improved, it is essential to recognize that this growth is not uniform across all dimensions. Specifically, certain dimensions related to transparency and accountability have experienced more significant growth than others have. Interestingly, the Audit (AUD) dimension, which serves as an accountability indicator, did not exhibit significant changes over the years, indicating a potential area for further exploration and improvement.

The finding that transparency and accountability have increased is not surprising, given the strong incentives and legal obligations imposed on Brazilian NSOs. In 2023 Brazil implemented a new regulatory framework concerning sports law, Law n° 14.597 (2023) ‘Lei Geral do Esporte’ (General Sports law). In addition, Law n° 14.790 (2023) ‘Lei de Aposta Fixa’ provided a more stringent set of regulatory practices for betting companies (i.e. bookmakers). These regulations also mandated a percentage of gambling revenues to sports organisations (Brasil, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). Both these laws create value for Brazilian sport management, especially in terms of enhanced transparency and accountability. These legal requirements, coupled with the potential loss of funding for noncompliance, have served as compelling drivers for positive changes. Furthermore, the influence of the Brazilian Olympic Committee (BOC) and its criteria, as established by the GET Program, have contributed to shaping the practices of NSOs in Brazil.

These findings suggest that the transparency indicator encompasses four key dimensions: the Publication of Financial Documents, Appointments and Reports, Internal Controls, and Access to Information and Files. As articulated by Schnackenberg and Tomlinson (Citation2016), transparency entails various facets such as information disclosure, clarity, and accuracy. It is intricately connected to the concepts of trust and credibility (Auger, Citation2014; Hood, Citation2010; Rawlins, Citation2008; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). The contextual significance of documents, including general meetings, annual reports, board meeting reports, financial statements, and other documents, reinforces the importance of transparency in NSOs (Brasil, Citation1998; Geeraert, Citation2015, Citation2018; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Morales & Schubert, Citation2022).

Within Brazilian NSOs, transparency is not merely a choice, but an obligation that mandates organizations to disclose relevant documents. While there have been improvements in transparency dimensions, it is noteworthy that issues related to Appointments and Reports (2015–2018 and 2018–2021) and Internal Controls (2015–2018) displayed variations. Although these variations may be due to methodological changes (such as modifications to survey items), it is evident that NSOs experienced difficulties in overcoming their legal obligations by including items that address issues beyond legal obligations.

The need for sports organizations’ transparency to surpass legal obligations has been firmly established (Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Henry & Lee, Citation2004; Král & Cuskelly, Citation2018; Marques & Costa, Citation2009; Pielke et al., Citation2020). Transparency within Brazilian NSOs has gained prominence, particularly in the aftermath of corruption and governance scandals. As argued by Ball (Citation2009), mere publication of information is insufficient to meet the public’s transparency needs. Notably, the annual ‘Governance Award Sou do Esporte’ has catalyzed improvements in the governance of Brazilian NSOs.

Despite the prevalence of corruption, resource mismanagement, misconduct, and financial challenges in Brazilian sports, these organizations continue to receive support from both public and private sources (Meira et al., Citation2012). Our study’s examination of outcomes reveals variations in accountability indicators over the years. Specifically, dimensions such as approval format, statement/demonstratives, fiscal council performance, and internal controls have exhibited differences and improvements. These findings indicate accountability mechanisms intertwined with NSOs’ adopted management processes. In this context, Molina and Ribeiro (Citation2017) following the steps of Grant and Keohane (Citation2005) identified diverse accountability mechanisms within the rugby NSO (Grant & Keohane, Citation2005). These mechanisms align closely with fulfilling legal requirements, signifying the organization’s compliance with mandatory legal accountability.

Accountability extends beyond financial statements and encompasses the responsibility for judiciously utilizing allocated resources, as suggested by Akutsu and Pinho (Citation2002). Gray et al. (Citation1996) defined accountability as encompassing both the duty to take action and duty to account for one’s actions. Alm (Citation2013) further expands this concept, highlighting that accountability involves not only providing an account, but also holding others accountable. In our study, we observed that despite its recognized importance, NSOs have not fully embraced accountability.

While there may be definitional differences, authors see accountability and transparency as conditions of working together, interdependent (Ball, Citation2009; Caetano et al., Citation2024; Král & Cuskelly, Citation2018; Marques & Costa, Citation2009; Mason, Citation2020). In particular, transparency plays a pivotal role in enhancing accountability. When organizations provide diverse information on the public interest in an easily accessible and comprehensible manner, it enhances trust, disclosure, and accountability (Gupta et al., Citation2020; Mason, Citation2020). It is worth noting that while transparency and accountability are closely aligned, their effective translation into practice requires clarity. This involves presenting information in an easily understandable format with an emphasis on simplicity and comprehensibility (Fox, Citation2007; Street & Meister, Citation2004).

Our analysis reveals an intriguing pattern. Accountability appears to have decreased between 2016 and 2017, followed by subsequent increases with a few significant variations. A similar decrease was observed in the global good governance index during this period. This decline in accountability may be associated with the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Rio. During this time, NSOs may have shifted their focus towards the holistic development of athletes, going beyond their conventional management obligations. Additionally, 2017 saw a decrease in public funding for NSOs compared with previous years (IPIE, Citation2023).

Our findings show that NSOs in Brazil do not fully adhere to the principles of good governance, particularly concerning transparency and accountability, despite being legally obligated to do so. This observation aligns with a study conducted by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (Ghai & Zipp, Citation2021).

The significance of sports governance in a country has been underscored by various organizations and authors (Furtado et al., Citation2022; Girginov, Citation2022; Pielke et al., Citation2020; Solanellas et al., Citation2024; Thompson et al., Citation2022). In a country such as Brazil, advocacy for good governance is instrumental in ensuring the effective utilization of resources and the promotion of increased investment in sports. This necessitates the modernization of NSOs, adherence to Brazilian laws governing fund allocation and distribution, and alignment with the objectives of the Brazilian Ministry of Sports to foster best practices.

Legislative changes occurred in Brazil between 2015 and 2021, especially between 2018 and 2020. In 2016 the Brazilian Federal Audit Court highlighted poor governance and management of performance sport, as well as deficiencies in the evaluation of public sports policies (Brasil, Citation2016). This included widespread non-compliance with legally mandated transparency and accountability benchmarks, that years later were still unaddressed by the Ministry of Sport (Brasil, Citation2016, Citation2022). This highlights the utility of performance indicators to monitor the allocation of public funds. These changes encompassed the introduction of control mechanisms within organizational statutes, increased athlete participation in decision-making, elections, and meetings, and the requirement to disclose received resources on NSOs’ websites. Consequently, an increase in transparency and accountability is not unexpected. As mentioned earlier, new laws (i.e. law n° 14.597 and law n° 14.970) emphasize the importance of regulating NSOs via improved transparency and accountability.

As Brazil continues to host international sporting events and aspires to excel in sports performance, the ongoing evolution of sports financing policies remains pivotal to achieving these goals. These policies not only impact the sports landscape, but also have the potential to shape the future of Brazilian sports, nurturing a culture of responsible financial management and transparency within NSOs, thereby contributing to the nation’s sporting excellence. In addition, the Brazilian sporting public is also relevant. Brazilians, or at least those who are members of affiliated sport organizations, should be able to access information about NSO performance and their use of government funds. In this way, both the sporting and wider public has the potential to exercise democratic social control (Raupp, Citation2022; Raupp & Pinho, Citation2016).

There is no doubt of the value of pursuing good governance through enhanced transparency and accountability. Further, longitudinal studies are likely to provide a more nuanced understanding of how improved transparency and accountability enhance organizational performance. This is critical given the lack of evidence supporting the conventional belief that good governance leads to improved organizational performance (Thompson et al., Citation2022).

Our research, in conjunction with Lefebvre et al. (Citation2023), shows that sports organizations governed better with improved governance, demonstrating benefits for stakeholders and the potential to have a positive impact on their innovation. Future research should examine the opportunities arising from new regulations, laws, and regulatory organizations to gain deeper insights into understanding transparency and accountability. In addition, future research should consider correlational analysis. For example, future research could explore relationships between transparency and accountability on the one hand, with financial performance. These correlations could be compared across the biggest and smallest Brazilian NSOs. There is opportunity to compare (and benchmark) the transparency and accountability of Brazilian NSOs with non-Brazilian NSOs. Such studies could be supported by agency theory and resource dependence theory, the sociology theories of Norbert Elias and Pierre Bourdieu, as well as institutional theory, more specifically, institutional isomorphism. Finally, future research should explore the indicators of good governance beyond transparency and accountability.

Limitations

Although rigorous, this research is not without limitations. Principally, although efficient, the quantitative method does not offer a granular understanding of transparency and accountability practices in practice, especially when considering the motives behind why certain practices are prioritized over others. An in-depth qualitative approach involving executive interactions, director dialogue, and athlete insights may provide a richer contextual understanding. Another discernible limitation is the over-reliance on web-based information. Notwithstanding the legislative directive obligating organizations to disclose financial reports on their digital platforms, non-compliance is rife. Challenges in publishing financial reports arise when there is a lack of competence in execution, unfamiliarity with procedures, or absence of an organization-wide open publishing mandate. An instructive avenue for future research might be the establishment of a focus group involving pertinent NSO stakeholders to critically assess the nature and methodology of document publication, offering insights into enhancing transparency and accountability. It is also imperative to mention that this study operates under the assumption that heightened transparency and accountability intrinsically elevates organizational performance. Regrettably, the absence of performance-centric variables in our methodology prevented empirical testing of this hypothesis, an area ripe for future exploration.

Conclusion

The empirical endeavor presented herein sought to evaluate the transparency and accountability dimensions of 34 emblematic Brazilian NSOs. Preliminary results denote observable advancements in the aforementioned domains yet highlight discernible avenues for further progression. Evidently, the imposition of statutory measures mandating superior levels of transparency and accountability appears to be a strategic intervention for amplifying governance quality. Concurrent endeavors to fortify both accountability and transparency are not merely desirable but essential, as corroborated by Král and Cuskelly (Citation2018). On a practical tangent, it is essential for decision-makers embedded within the Brazilian sports ecosystem to internalize and act on the imperatives of this study, focusing not only on legislative adherence but also on pioneering governance best practices. The cardinal takeaway for such stakeholders should be the unequivocal importance of unyielding commitments to transparency and accountability as cornerstones of institutional integrity and public credibility. In light of the insights unearthed in this study, the clarion calls for future scholarly pursuits, especially those poised to address the identified research lacunae, to become even more compelling, beckoning a deeper exploration into the governance intricacies of sports institutions.

Authors’ contributions

The authors Gustavo Bavaresco, Geoff Dickson, Philipe Camargo, Thiago Santos, Fernando Marinho Mezzadri were involved in the conception and design; Gustavo Bavaresco and Thiago Santos were in the analysis and interpretation of the data; Gustavo Bavaresco, Geoff Dickson, Philipe Camargo were with the drafting of the paper; Gustavo Bavaresco, Geoff Dickson, Fernando Marinho Mezzadri were and revising it critically for intellectual content; and Gustavo Bavaresco, Geoff Dickson, Fernando Marinho Mezzadri with the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to Sou do Esporte and all researchers involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Mendeley Data] at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/gbtj43xtx9/1.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gustavo Bavaresco

Gustavo Bavaresco (Master in Sport Management, Faculty of Sport, University of Porto, Portugal) is a Ph.D. candidate at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), Brazil, and a researcher at the Sports Intelligence Research Institute at the same university. His research interests include sports governance and management, sport development, sports public policies, sports events, and sports volunteering.

Geoff Dickson

Geoff Dickson (Ph.D., Griffith University), Associate Professor, La Trobe University, La Trobe Business School, Department of Management, Sport and Tourism. His research interests include sport management, sport marketing and sport governance.

Philipe Camargo

Philipe Camargo (Ph.D., Federal University of Paraná), Professor at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Pantanal Campus. Researcher at the Sports Intelligence Research Institute - UFPR. He works mainly on the following research themes: sport; state; public policies, management, and governance of sport.

Thiago Santos

Thiago Santos (Ph.D., University of Lisbon), Professor, European University, Department of Sport Management. His research interests include sports governance, management, public sports policies, sports events, marketing, quality of service in sports programs, and sports against match-fixing.

Fernando Marinho Mezzadri

Fernando Marinho Mezzadri (Ph.D., Campinas State University/UNICAMP) is currently a Professor at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) and Dean of Planning, Budget, and Finance at UFPR and coordinates the Sports Intelligence Research Institute. He currently develops research in the areas of public sports policies and sports management.

References

- Akutsu, L., & Pinho, J. A. G. d (2002). Sociedade da informação, accountability e democracia delegativa: Investigação em portais de governo no Brasil. Revista De Administração Pública, 36(5), 1–18. https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/rap/article/view/6461

- Alm, J. (2013). Action for good governance in international sports organisations: Final report. Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies.

- Almeida, B. S. D., & Marchi Júnior, W. (2011). Comitê Olímpico Brasileiro e o financiamento das confederações brasileiras. Revista Brasileira De Ciências Do Esporte, 33, 163–179. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-32892011000100011&nrm=iso

- Angulo, A., Nachtmann, H., & Waller, M. A. (2004). Supply chain information sharing in a vendor managed inventory partnership. Journal of Business Logistics, 25(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2004.tb00171.x

- ASOIF. (2016). About governance task force of ASOIF. https://www.asoif.com/sites/default/files/download/asoif_governance_task_force_report.pdf

- Auger, G. A. (2014). Trust me, trust me not: An experimental analysis of the effect of transparency on organizations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(4), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2014.908722

- Ball, C. (2009). What is transparency? Public Integrity, 11(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922110400

- Beims, M. W., & Schmitt, P. M. (2020a). O esporte fora da bolha: Análise da pandemia COVID-19 para viajantes. http://www.inteligenciaesportiva.ufpr.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/O-Esporte-Fora-da-Bolha-dez2020.pdf

- Beims, M. W., & Schmitt, P. M. (2020b). O esporte fora da bolha: Análise da pandemia COVID-19 para viajantes 3ed. http://www.inteligenciaesportiva.ufpr.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/O-Esporte-Fora-da-Bolha-dez2020.pdf

- Bernstein, E. S. (2012). The transparency paradox: A role for privacy in organizational learning and operational control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(2), 181–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839212453028

- Bevir, M. (2011). The making of British socialism [Book]. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400840281

- Brasil. (1998). Lei n° 9.615, de 24 de março de 1998. Institui normas gerais sobre desporto e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial [Da República Federativa Do Brasil], n° 57-E Brasília - DF De 25 De Março De 1998.

- Brasil. (2001). Lei n° 10.264, de 16 de julho de 2001. Acrescenta inciso e parágrafos ao art. 56 da Lei no 9.615, de 24 de março de 1998, que institui normas gerais sobre desporto. Diário Oficial [da República Federativa do Brasilhttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10264.htm

- Brasil. (2016). Tribunal de Contas da União. Acórdão n° 3162/2016 - Plenário Relator: Ministro Vital do Rêgo. Processo TC 023.922/2015-0. Ata 50/2016 Brasilia, DF, Sessão 07/12/2016 https://portal.tcu.gov.br/biblioteca-digital/auditoria-de-conformidade-na-aplicacao-dos-recursos-da-lei-agnelo-piva-por-parte-das-entidades-componentes-do-sistema-nacional-do-desporto.htm

- Brasil. (2022). Tribunal de Contas da União. Acórdão n° 2148/2022 - Plenário Relator: Ministro Benjamin Zymler. Processo TC 015.641/2018-0. Ata 37/2022 Brasilia, DF, Sessão 28/09/2022 https://portal.tcu.gov.br/imprensa/noticias/ministerio-do-esporte-nao-acompanhou-uso-de-recursos-publicos-repassados-ao-esporte-de-alto-rendimento.htm

- Brasil. (2023a). Lei n° 14.597, de 14 de junho de 2023. Institui a Lei Geral do Esporte. Diário Oficial [da República Federativa do Brasil], 15 de junho de 2023, Edição 112, Seção 1, p. 6. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-14.597-de-14-de-junho-de-2023-490088801

- Brasil. (2023b). Lei n° 14.970, de 29 de dezembro de 2023. Dispõe sobre a modalidade lotérica denominada apostas de quota fixa; altera as Leis n°s 5.768, de 20 de dezembro de 1971, e 13.756, de 12 de dezembro de 2018, e a Medida Provisória n° 2.158-35, de 24 de agosto de 2001; revoga dispositivos do Decreto-Lei n° 204, de 27 de fevereiro de 1967; e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial [da República Federativa do Brasil], 30 de dezembro de 2023, Edição Extra n° 247-J, Seção 1, p. 6. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2023/lei/l14790.htm

- Briscoe, F., & Murphy, C. (2012). Sleight of hand? Practice opacity, third-party responses, and the interorganizational diffusion of controversial practices. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(4), 553–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839212465077

- Caetano, C. I., Ordonhes, M. T., López-Gil, J. F., & Cavichiolli, F. R. (2024). Revisión de estudios sobre variables de gobernanza en entidades deportivas: clasificación de Brasil [Review of studies on governance variables in sports entities: classification of Brazil]. Retos, 52, 282–290. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v52.101968

- Caixa. (2022). Repasses sociais e relatórios anuais. https://loterias.caixa.gov.br/Paginas/Repasses-Sociais.aspx

- Cardoso, V. D., Nicoletti, L. P., & Haiachi, M. d C. (2020). Impactos da pandemia do COVID-19 e as possibilidades de atividades físicas e esportivas para pessoas com deficiência. Revista Brasileira De Atividade Física & Saúde, 25, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.12820/rbafs.25e0119

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2016). From Olympic administration to Olympic governance. Sport in Society, 19(6), 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1108648

- Chappelet, J.-L., & Mrkonjic, M. (2013). Basic indicators for better governance in international sport (Bibgis): An assessment tool for international sport governing bodies.

- Chappelet, J.-L., & Mrkonjic, M. (2019). Assessing sport governance principles and indicators. In M. Winand & C. Anagnostopoulos (Eds.), Research handbook on sport governance (pp. 10–28). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786434821

- Charlton, B., & Andras, P. (2003). The modernization imperative. (8th ed.).

- COB. (2020). Guia para a prática de esportes olímpicos no cenário da COVID-19. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/cob/home/guia-esporte-covid

- COB. (2021a). As Confederações. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/cob/confederacoes

- COB. (2021b). Confederações. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/cob/confederacoes

- COB. (2021c). Critérios de distribuição dos recursos 2020. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/documentos/download/dc18d222e688b/

- COB. (2021d). Revisão dos critérios de distribuição de recursos ordinários 2022 a 2024. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/documentos/download/4a024144778d4/

- COB. (2021e). Sobre o COB. https://www.cob.org.br/pt/cob/home/sobre-o-cob

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- De Dycker, S. (2019). Good governance in sport: Comparative law aspects. The International Sports Law Journal, 19(1-2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-019-00153-8

- Dowling, M., Leopkey, B., & Smith, L. (2018). Governance in sport: A scoping review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(5), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0032

- Finlayson, A. (2003). The meaning of modernisation. In A. Finlayson (Ed.), Making sense of new labour. (pp. 62–83). Wishart Ldt.

- Fox, J. (2007). The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability. Development in Practice, 17(4-5), 663–671. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25548267 https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469955

- Freitas, A. R. R., Napimoga, M., & Donalisio, M. R. (2020). Assessing the severity of COVID-19. Epidemiologia e Servicos De Saude: revista Do Sistema Unico De Saude Do Brasil, 29(2), e2020119. https://doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742020000200008

- Furtado, S., Piggin, J., Goncalves, G. H. T., & Mezzadri, F. (2022). The modernization process in Brazilian National Olympic Federations. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2022.2136101

- Gardiner, S., Parry, J., & Robinson, S. (2017). Integrity and the corruption debate in sport: Where is the integrity? European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1259246

- Geeraert, A. (2015). Sports governance observer 2015: The legitimacy crisis in international sports governance. Play the Game.

- Geeraert, A. (2018). National sports governance observer. Final report. Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies.

- Geeraert, A. (2022). Indicators of good governance in sport organisations: Handle with care. In A. Geeraert & F. V. Eekeren (Eds.), Good governance in sport: Critical reflections (1st ed., pp. 152–166). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003172833

- Geeraert, A., Alm, J., & Groll, M. (2014). Good governance in international sport organizations: An analysis of the 35 Olympic sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2013.825874

- Ghai, K., & Zipp, S. (2021). Governance in Indian cricket: Examining the board of control for cricket in India through the good governance framework. Sport in Society, 24(5), 830–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1819598

- Girginov, V. (2022). The numbers game: Quantifying good governance in sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(6), 1889–1905. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2078851

- Granados, N., Gupta, A., & Kauffman, R. J. (2010). Research commentary - information transparency in business-to-consumer markets: Concepts, framework, and research agenda. Information Systems Research, 21(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1090.0249

- Grant, R. W., & Keohane, R. O. (2005). Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. American Political Science Review, 99(1), 29–43. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:cup:apsrev:v:99:y:2005:i:01:p:29-43_05

- Gray, R., Owen, D., & Adams, C. (1996). Accounting & accountability: Changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. Prentice hall.

- Gupta, A., Boas, I., & Oosterveer, P. (2020). Transparency in global sustainability governance: To what effect? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1709281

- Havaris, E. P., & Danylchuk, K. E. (2007). An assessment of sport Canada’s sport funding and accountability framework, 1995–2004. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701270329

- Henry, I., & Lee, P. C. (2004). Governance and ethics in sport. In J. Beech & S. Chadwick (Eds.), The business of sport management (pp. 25–41). Pearson Education.

- Hood, C. (2010). Accountability and transparency: Siamese twins, matching parts, awkward couple? West European Politics, 33(5), 989–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.486122

- Hums, M. A., & MacLean, J. C. (2017). Governance and policy in sport organizations. (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003303183

- IBGC. (2015). Código das melhores práticas de governança corporativa. (5th ed.). Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa.

- Inglehart, R. (2021). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. In R. Inglehart (Ed.), Modernization and postmodernization in 43 societies (pp. 67–107). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691214429-005

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2007). Modernization. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, Moore. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosm118

- Ingram, K., & O’Boyle, I. (2018). Sport governance in Australia: questions of board structure and performance. World Leisure Journal, 60(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2017.1340332

- Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. (2023). Ipea Mantém Previsão De Crescimento Do PIB Para 2023 Em 1,4%.

- IPIE. (2023). Financiamento Esportivo. http://www.inteligenciaesportiva.ufpr.br/site/index.php/nossos-relatorios-de-bi/

- Kaptein, M. (2008). Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: the corporate ethical virtues model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(7), 923–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.520

- Khotami. (2017). The concept of accountability in good governance. International Conference on Democracy, Accountability and Governance (ICODAG 2017), 30–33. https://doi.org/10.2991/icodag-17.2017.6

- Kosack, S., & Fung, A. (2014). Does transparency improve governance? Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-032210-144356

- Král, P., & Cuskelly, G. (2018). A model of transparency: Determinants and implications of transparency for national sport organizations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(2), 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1376340

- Lefebvre, A., Zeimers, G., Helsen, K., Corthouts, J., Scheerder, J., & Zintz, T. (2023). Better governance and sport innovation within sport organizations. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2023.2228833

- Marques, D. S. P., & Costa, A. L. (2009). Governança em clubes de futebol: Um estudo comparativo de três agremiações no estado de São Paulo. Revista De Administração - RAUSP, 44(2), 118–130. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=223417531003 (IN FILE)

- Mason, M. (2020). Transparency, accountability and empowerment in sustainability governance: A conceptual review. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1661231

- Meira, T. d B., Bastos, F. d C., & Böhme, M. T. S. (2012). Análise da estrutura organizacional do esporte de rendimento no Brasil: um estudo preliminar. Revista Brasileira De Educação Física e Esporte, 26(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-55092012000200008

- Mezzadri, F. M., Haas, L. G. N., Neto, R. D C. S., & Santos, T. D O. (2018). Cartilha de governança em entidades esportivas Lei 9.615/98 (2 ed.). Ministério do Esporte. http://www.inteligenciaesportiva.ufpr.br/site/cartilha-de-governanca-em-entidades-esportivas/

- Mezzadri, F. M., Moraes e Silva, M., Figuêroa, K. M., & Starepravo, F. A. (2015). Sport policies in Brazil. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(4), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2014.937737

- Ministério do Esporte. (2023a). O Ministério. https://www.gov.br/cidadania/pt-br/composicao/orgaos-especificos/esporte

- Ministério do Esporte. (2023b). Sobre o Ministério do Esporte. https://www.gov.br/mds/pt-br/pt-br/composicao/orgaos-especificos/esporte

- Molina, R. d C., & Ribeiro, H. C. M. (2017). A Prática da accountability em uma organização esportiva: O caso da Confederação Brasileira de Rugby (CBRu). PODIUM Sport, Leisure and Tourism Review, 6(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.5585/podium.v6i2.207

- Morales, N., & Schubert, M. (2022). Selected issues of (good) governance in North American professional sports leagues. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(11), 515. https://www.mdpi.com/1911-8074/15/11/515 https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15110515

- Muñoz, J., Solanellas, F., Crespo, M., & Kohe, G. Z. (2023). Governance in regional sports organisations: An analysis of the Catalan sports federations. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2209372. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2209372

- O’Boyle, I. (2012). Corporate governance applicability and theories within not-for-profit sport management. Corporate Ownership and Control, 9(2), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv9i2c3art3

- Parent, M. M., & Hoye, R. (2018). The impact of governance principles on sport organisations’ governance practices and performance: A systematic review. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1503578. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1503578

- Parnell, D., Millward, P., Widdop, P., King, N., & May, A. (2018). Sport policy and politics in an era of austerity. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1432672

- Pielke, R., Harris, S., Adler, J., Sutherland, S., Houser, R., & McCabe, J. (2020). An evaluation of good governance in US Olympic sport national governing bodies. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(4), 480–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1632913

- Pitanga, F. J. G., Beck, C. C., & Pitanga, C. P. S. (2020). Inatividade física, obesidade e COVID-19: Perspectivas entre múltiplas pandemias. Revista Brasileira De Atividade Física & Saúde, 25, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.12820/rbafs.25e0114

- Queiroz, C. (2022). Recordes, escândalos e despedidas marcaram o esporte de 2022. https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/esporte/2023/01/recordes-escandalos-e-despedidas-marcaram-o-esporte-de-2022.shtml

- Raupp, F. M. (2022). Passive transparency in the largest brazilian municipalities after ten years of the Access to Information Law. Revista Da CGU, 14(25), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.36428/revistadacgu.v14i25.484

- Raupp, F. M., & Pinho, J. A. G. d (2016). Review of passive transparency in Brazilian city councils. Revista De Administração, 51(3), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.02.001

- Rawlins, B. (2008). Give the emperor a mirror: Toward developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. Journal of Public Relations Research, 21(1), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802153421

- Ribeiro, M. A. d S. (2012). Modelos de governança e organizações esportivas: Uma análise das federações e confederações esportivas brasileiras. Marco Ribeiro.

- Sam, M. P., Andrew, J. C., & Gee, S. (2018). The modernisation of umpire development: Netball New Zealand’s reforms and impacts. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(3), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1377272

- Saraite-Sariene, L., Alonso-Cañadas, J., Galán-Valdivieso, F., & Caba-Pérez, C. (2020). Non-financial information versus financial as a key to the stakeholder engagement: A higher education perspective. Sustainability, 12(1), 331. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/1/331

- Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W., Pennington, J., Murphy, R., & Doherty, K. (1994). The triangle model of responsibility. Psychological Review, 101(4), 632–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.632

- Schnackenberg, A. K., Tomlinson, E., & Coen, C. (2021). The dimensional structure of transparency: A construct validation of transparency as disclosure, clarity, and accuracy in organizations. Human Relations, 74(10), 1628–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720933317

- Schnackenberg, A. K., & Tomlinson, E. C. (2016). Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organization-stakeholder relationships. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1784–1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525202

- Solanellas, F., Muñoz, J., Genovard, F., & Petchamé, J. (2024). Governance policies in sports federations. A comparison according to their size. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v8i1.2834

- Street, C. T., & Meister, D. B. (2004). Small business growth and internal transparency: The role of information systems. MIS Quarterly, 28(3), 473–506. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148647

- Tacon, R., & Walters, G. (2016). Modernisation and governance in UK national governing bodies of sport: how modernisation influences the way board members perceive and enact their roles. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(3), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2016.1194874

- Thompson, A., Lachance, E. L., Parent, M. M., & Hoye, R. (2022). A systematic review of governance principles in sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(6), 1863–1888. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2077795

- Tóth, N. Á., & Mátrai, G. (2023). The system of Hungarian sport financing, with special regard to public finance aspects. Pénzügyi Szemle = Public Finance Quarterly, 69(2), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.35551/PFQ_2023_2_5

- Urdaneta, R., Guevara-Pérez, J. C., Llena-Macarulla, F., & Moneva, J. M. (2021). Transparency and accountability in sports: Measuring the social and financial performance of Spanish professional football. Sustainability, 13(15), 8663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158663

- Veal, A. J., & Darcy, S. (2014). Research methods in sport studies and sport management: A practical guide. Routledge.

- Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Oke, A. (2011). Retracted: Authentically leading groups: The mediating role of collective psychological capital and trust. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.653

- Williams, C. C. (2008). Toward a taxonomy of corporate reporting strategies. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 45(3), 232–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943608317520

- Winand, M., & Anagnostopoulos, C. (2019). Research handbook on sport governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Winand, M., Steen, A., & Kasale, L. L. (2021). Performance management practices in the sport sector: An examination of 32 Scottish national sport organizations. Journal of Global Sport Management, 8(4), 739–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2021.1899765