Abstract

This study utilized 2020 survey data from 9920 older adults to explore their care, housing needs, and preferences, with a primary focus on developing a sustainable care plan for aging in place. The care status and housing requirements of older adults, the types of family caregivers and the adequacy of the support they provide, and older adults’ subjective assessments of their lives and living conditions were assessed. Statistical methods, including chi-square tests and ANOVA, supported this analysis. The findings revealed a prevalent belief in the inadequacy of care provided by family members and that their living conditions were not elderly-friendly environments. However, the elderly surveyed also expressed a strong preference for family support and familiarity with their current housing, indicating resilience and a willingness to adapt to changing cohabitation needs. This study highlights the critical role of families in elderly care, points to an increasing need for home-centred care solutions, advocates for a balanced approach to dependence and independence within family care dynamics, and suggests establishing community-based care centres as a practical solution. The recommendations include developing community hubs to support care networks, enhancing the infrastructure to support home care, providing specialized training for family caregivers, and distributing guidelines to create elderly-friendly living spaces and facilitate home modifications. The study concluded that a supportive housing environment that encourages even minimal interaction within a care network can significantly improve life and health satisfaction among older adults, underscoring the substantial, positive impact of comprehensive family support that extends beyond traditional care benefits.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and purpose

Population aging, a phenomenon driven by decreased fertility rates and extended life expectancy, presents a significant opportunity for older adults, families, and societies worldwide. It brings with it the gift of longer lives, offering older adults more time to contribute their unique talents, experiences, and wisdom. This wealth of knowledge and expertise can greatly enrich communities and societies (United Nations (UN), Citation2019; World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2021; United Nation Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP), Citation2022).

Among the OECD nations, South Korea has witnessed an impressive surge in its aging population, surpassing 14% in 2018, less than two decades after crossing the threshold of a 7% aging society in 2000. Projections indicate that Korea is poised to become a society with over 20% of its population classified as aged by 2025 (Statistics Korea, Citation2019a).

This demographic shift has led to a notable rise in the proportion of older adult households over the past two decades, including both single aged and married aged couples. Additionally, there is an escalating demand for care services (Statistics Korea, Citation2019b, Citation2021, Citation2022, Citation2023). Anticipated growth in the aging population with disabilities, including those with acquired disabilities, further emphasises the necessity of creating safe and comfortable housing spaces for vulnerable older adults. This environment supports their well-being, while also providing opportunities for them to share their time, talents, and experiences with the broader community (Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute, Citation2021; Lee, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2021; UN, Citation2019; Yeom, Citation2019).

Before South Korea, developed nations that are grappling with aging populations are actively implementing diverse strategies to meet the care needs of their aging citizens. The focus of aging in place (AIP) and housing welfare policies has shifted towards enabling older adults to navigate their later years with comfort and recognise their potential to continue making meaningful contributions to society (Kim, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2017; Schulz & Eden, Citation2016; UN ESCAP, Citation2022; WHO, Citation2007).

Ensuring a suitable housing environment for older adults is not merely about accommodation, but rather entails the creation of an environment that fosters independent living, while promoting physical, emotional, and social well-being. Such environments also facilitate social integration, reducing the likelihood of premature institutionalisation. This inclusive approach allows older adults to remain active participants in their communities, sharing their time, talents, and experiences with others (Carnemolla & Bridge, Citation2019; Perez et al., Citation2001; Hwang et al., Citation2011).

The Korean government has recently championed the adoption of a community-integrated care policy to meet the care needs of an aging population. This endeavour necessitates seamless collaboration with local governments and private resources. Central to the continuity of care is the provision of stable staffing capable of meeting the diverse needs of older adults and the establishment of infrastructure conducive to a caring housing environment within communities (Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW), Citation2018, Citation2020; National Rehabilitation Center, Citation2020). However, the shortage of elderly-friendly housing and the unpredictability of health conditions undermine the assurance of sustained care for older adults in the community (Hwang et al., Citation2015; Yu & Kim, Citation2014). The COVID-19 pandemic has further strained the public welfare delivery system, shifting a considerable burden of care back onto families and exacerbating existing challenges (Kim, Citation2020; National Research Council for Economics Humanities and Social Sciences (NRC), Citation2022).

While welfare facilities for older adult care are on the rise, there are limitations in their supply, and concerns arise regarding the strain on care workers and older adults due to budget constraints related to pensions and medical expenses (Seo, Citation2022). The accelerated aging of Korea further intensifies the financial pressure associated with annuities and medical costs, placing an ever-increasing burden on societal resources (Kim & Kim, Citation2020). This scarcity of care staffing and budget constraints underscores the necessity for comprehensive measures to minimise the burden on individuals and society, particularly by enhancing the self-reliance of older adults, enabling them to continue residing in their existing homes.

Accordingly, constructing or modifying houses for vulnerable populations, particularly older adults, and strict adherence to the standards for installing convenience facilities in houses (Enforcement Decree of the Act on Support for the Residential Weaknesses, Presidential Decree No. 24063) for the weak is imperative in South Korea. These standards provide guidelines for various spaces, encompassing entrance doors, handles, floor surfaces, storage devices, living rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms (Korean Law Information Center, Citation2012). However, some essential items, such as lowering the floor, are not included, and many types of modifications are only applicable to people with disabilities (Lee, Citation2021). This has sparked controversy, particularly regarding construction companies’ tendencies to meet only the minimum housing standardsFootnote1 when modifying houses, prompting calls for policy revisions (Hwang et al., Citation2022).

A critical aspect of achieving a seamless continuum of care within the community is ensuring that older adults receive appropriate care at various levels and intensities (Hwang et al., Citation2011). Additionally, homes should be adaptable to the changing health status or level of assistance required by older adults. Therefore, to ensure the well-being and satisfaction of older adults, it is crucial to understand their views on the care they receive from their families and the suitability of their living situation.

Thus, this study delves into older adults’ subjective experiences and feelings regarding family care and housing comfort. It aims to identify the conditions and needs of older adults who rely on family support for care, and to provide policy recommendations for improving their home-based care services.

The research question that framed our investigation was the following:

Research Question: What do older adults feel is receiving good care from their families and housing environment?

Specific hypotheses were the following:

Hypothesis 1: Most older adults will be dissatisfied with their family care and housing environment.

Hypothesis 2: Most older adults will prefer government-based care support and home modification for sustainable living at home.

1.2. Aging population, family care, and care and housing needs

The declining birth rate and aging population have given rise to the issues of demographic shifts and a care deficit, which have become significant social challenges (WHO, Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2021). Traditionally, these matters were addressed by families at a national level, particularly in eastern countries like Korea (Cho et al., Citation2011). While social security policies are expanding, the responsibility for informal family care remains with family members, regardless of whether they are in eastern or western countries. This burden of caregiving disproportionately falls especially upon women (Ham & Hong, Citation2017; Jeong et al., Citation2020; Namkung, Citation2019; Turcotte, Citation2013; Wanless, Citation2006; WHO, Citation2017, Citation2020). While receiving public care support in the community, it is also acknowledged that ensuring a consistent level of care is unattainable without family involvement to bridge the care gap that arises when living at home, unless in a hospital (Jeong et al., Citation2020).

A recent survey conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs in 2020 found that the majority of older adults primarily received support from their closest family members, including spouses, children, and parents. Moreover, the give and take of assistance with these family members was the most prevalent and actively engaged form of support (Lee et al., Citation2021). While only approximately half of older adults facing physical decline receive more than one assistance for activities of daily living (ADL) Footnote2 or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL),Footnote3 the primary caregivers are still identified as family members who either cohabit (74.5%), or do not cohabit (39.3%), with them. This highlights their reliance on family support. However, the receiving of physical support (such as care, nursing, and hospital accompanying) required by older adults was inadequate, and the level of assistance provided was generally low. Additionally, older adults living alone without a spouse or immediate family experienced even greater inadequacy in terms of both physical support and the level of assistance provided, compared to their counterparts (Lee et al., Citation2021).

Whether alone or not, older adults become more vulnerable to the environment, and naturally need care as they age and develop health problems. Then, they will have no choice but to accept nursing care or support for daily activities from family members, such as spouses or children. However, the burden of family caregiving primarily revolves around psycho-emotional challenges, notably depression and stress. Families providing care tend to face a higher likelihood of experiencing mental health issues, including depression and social isolation, than non-caregiver counterparts. In contrast to those not bearing this responsibility, caregiver families exhibit a 2.36-fold increase in the likelihood of falling into the severely depressed category. Caregivers are also 2.45 times more likely to report poor subjective health perception, and 1.27 times more likely to seek outpatient treatment (American Psychological Association (APA), Citation2011; Chan et al., Citation2013; Namkung, Greenberg, & Mailick, Citation2017; Namkung, Citation2019; NASEM, Citation2016; Yi, Citation2019). Furthermore, this hidden burden on family caregivers transcends multiple levels, reaching a perilous state that may lead to extreme outcomes, including experiences of hardship, instances of abuse, cases of neglect, and even contemplation of suicide (De Korte-Verhoef et al., Citation2014; Schulz & Eden, Citation2016). Moreover, for a long time, due to situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, if the public welfare delivery system is blocked, the burden of care increases for families, and eventually exhausts them (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ), Citation2022; Jeong et al., Citation2020; Kim, Citation2020; National Rehabilitation Center, Citation2020).

In South Korea, a prevailing preference among older adults is to age in place, receiving in-home services rather than moving to nursing facilities. This choice is often driven by a desire for familiarity and comfort in their own homes, or due to financial constraints associated with nursing home expenses (Lee et al., Citation2021; Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT), Citation2021a).

Most older adults’ households were homeowners (44.0%) or dwelt in general detached houses (43.4%) (MOLIT, Citation2022). However, there is significant concern about the safety of these homes, especially since the age of the construction period is over 30 years old, accounting for 32.8% of cases—nearly double the rate observed in other households (MOLIT, Citation2021b).

Despite the age of these dwellings, there is often hesitancy to pursue housing modifications. This reluctance stems from the government’s temporary aid program, which focuses primarily on the economically disadvantaged and severely disabled individuals, leaving others outside its scope facing potential challenges, costs, and logistical complexities (Hwang et al., Citation2023; Lee et al., Citation2021).

Also, as people age, their dependence on the living environment increases, and environmental pressure, which encompasses the demands and challenges placed by the physical and social environment on an individual, becomes more pronounced. This underscores the importance of a tailored housing environment for older adults, emphasizing the need for continuity and familiarity as they navigate aging (Atchley, Citation1989; Lawton & Nahemow, Citation1973).

Given the changing needs due to physical and cognitive limitations in aging, a nuanced approach to housing becomes crucial. The living conditions significantly impact caregiving experiences, physical well-being, and the occurrence of safety incidents, particularly falls. Falls can be attributed to a combination of intrinsic factors like age-related health issues and extrinsic environmental factors like poor lighting and slippery floors, all of which increase the risk as they accumulate (American Geriatrics Society et al., Citation2001; CDC, Citation2017).

A study by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency revealed that falls, especially within homes, constitute a significant percentage of injuries in older adults. Notably, falls within residences occur most frequently in bedrooms and bathrooms, often due to factors like problematic flooring and inadequate handrails, accounting for 18.5 and 12.2% of incidents respectively (Ahn et al., Citation2016). This highlights the urgent need for a secure residential environment.

Home modifications in old age have been shown to increase both housing and life satisfaction while decreasing dysfunction and medical costs (Altman & Barnartt, Citation2014). According to a recent study on the relationship between an elderly-friendly environment and care in 157 Australian older adults (average 72 years old) who received government-supported housing renovation services,Footnote4 there was a difference in weekly care hours before and after housing renovation. After the housing renovation, the change in informal care per week decreased by 6 h, and the official care time per week decreased by 0.36 h. As the total weekly care time decreased by 6.32 h, it was found that home improvement affected the independence, autonomy, self-care, or well-being of older adults, and reduced direct care time at home, leading to an overall 9.4% decrease in care hours (Carnemolla & Bridge, Citation2019).

As older adults age, they tend to rely more on external assistance, tools and aids due to physical and cognitive changes. This necessitates adjustments in living spaces to accommodate evolving needs. Recognizing that suboptimal housing conditions can affect health and caregiving, it becomes crucial to address these issues (Lawton & Nahemow, Citation1973). It is imperative to support housing conditions and caregiving to ensure the health, independence, and stable care of older adults. Understanding the current care status and environment is critical. Additionally, providing tailored support based on the needs and challenges of older adults and their families is crucial in creating appropriate care environments and services.

2. Research methods and procedures

2.1. Classification of data and analysis subject

As quantitative information, this study used microdata from the 2020 survey of older adults obtained from the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s health and welfare data portal site (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) Data Portal, Citation2021). The analysis focused specifically on households that reported receiving care, encompassing a total of 9920 out of the initially surveyed 10,097 households. These households, representing older adults aged 65 and above from all regions of the country, were included based on their receipt of either minimal instrumental assistance (e.g., cleaning, meal preparation, laundry) or physical assistance (e.g., personal care, nursing, transportation to medical appointments) from caregivers. In this context, caregivers include family members, such as spouses, children (regardless of their living situation), parents (including in-laws), and also, external care providers. This categorisation allowed for an in-depth analysis of the care support network available to older adults, emphasizing the role of both family members and professional caregivers in providing instrumental and physical assistance.

2.2. Analysis of data

This study was analysed by division into the following three steps to examine the care status and housing needs of older adults, focusing on the type of family caregiver (). All of the analysis delved into utilising the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s health and welfare data portal site. In the first step, the type of family caregiver according to gender and age was investigated. The difference in the level of help sufficiency for each type of family caregiver, and the subjective evaluation of current life, were analysed. In the second step, assessment of the current housing conditions of older adults examined whether their housing was equipped with features that enhanced accessibility for older adults. This examination included the removal of thresholds, the installation of slopes, and the placement of handles to support the mobility and safety of older adults. Moreover, this analysis phase extended beyond physical modifications; it explored the subjective perceptions of the current housing conditions and the overall quality of life. An integral part of this investigation involved analysis of the interplay between the living conditions of older adults and the types of family caregivers involved. In the third step, the needs for housing and care were analysed, with the home modification by type of family caregiver, and care services the government provides being compared and analysed in terms of age group. The data were analysed using frequency analysis, chi-square test, independent sample t-test, F-test (one-way ANOVA), and bivariate correlation analysis. IBM SPSS 25.0 was used throughout the study.

Table 1. Analysis contents.

3. Results

3.1 Overview of subjects

3.1.1. Demographics

There were a total of 9920 participants, comprising 3971 males (40%) and 5949 females (60%). In terms of age, 5977 participants (60.3%) were aged 65 to 74 years, 3333 (33.6%) were aged 75 to 84 years, and 610 (6.1%) were over 85 years of age. The majority were from the non-capital regions 4730 (47.7%), with 2765 (27.9%) from the capital region, and 2425 (24.4%) from other areas. Regarding living arrangements, 3117 (31.4%) were single, while 5071 (51.1%) had a spouse or partner. The most common housing type was a general detached house (3931, 39.6%), followed by an apartment (4700, 47.4%). A significant majority were homeowners 7909 (79.7%). While most participants were fully independent in both the activities of daily living (ADL) and the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), there was a notable minority of about 10% who required assistance with IADL ().

Table 2. Demographic characteristics.

3.1.2. Subjective evaluation of current life

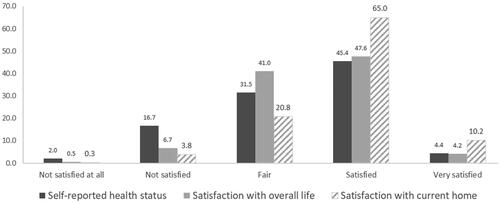

shows that 49.9% of older adults, about half, perceived that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their self-reported health status, while 51.8% of older adults were satisfied or very satisfied in terms of overall life satisfaction. Regarding satisfaction with their current housing, 75.2% of older adults were satisfied or very satisfied. The mean score was the highest in the current housing in the order: current housing satisfaction (3.81 points, SD = 0.66) > life satisfaction (3.48 points, SD = 0.70) > self-reported health status (3.33 points, SD = 0.87), based on a 5-point scale.

3.2. Family care characteristics

3.2.1. Type of family caregivers

Only older adults who reported receiving assistance from their families and outsourcing were included in the analysis. The types of family caregivers for older adults were classified into five categories based on whether the subject received care from family members. All older adults received care from at least one family caregiver, except for outsourcing. The distribution of family caregivers was as follows: son or daughter living independently (62.4%), spouses (56.3%), son or daughter living together (14.7%), and parent (2.2%). Outsourcing accounted for 12.7% (). This may be because there are many households with women living alone, but it can also be observed that in spousal relationships, men are less cooperative in providing care support than women.

Table 3. Type of family caregiver.

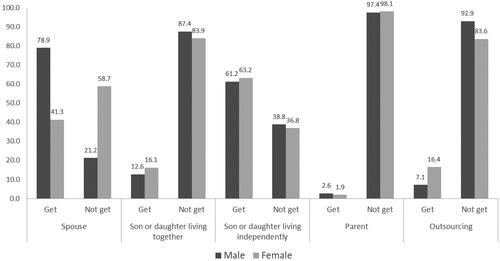

3.2.2. Gender

compares the type of family caregiver support by gender. Most males (78.9%) received more family care from their wives; in contrast, the proportion of wives who did not receive care support from their husbands was 58.7%, while the proportion of husbands who did not receive care support from wives was only 21.2%. But the proportion of females who received more support from their son or daughter was slightly higher than that of the males, 16.3% (males 12.6%) of son or daughter living together, and 63.2% (males 61.2%) of son or daughter living independently supporting their mother. Receiving care from a parent was similar for males and females, but the proportion of males (2.4%) was a little higher than that of females (1.9%). On the other hand, the proportion of females (16.4%) who did not receive care from family members, which is outsourcing, was more than two times higher that of males (7.2%).

3.2.3. Age

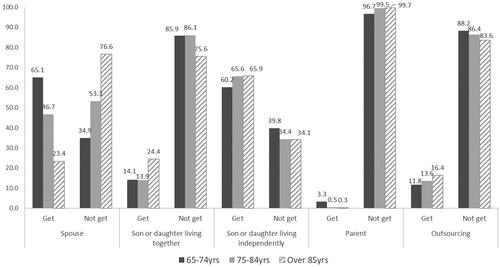

Age was categorised into three groups for analysis. Care received from a spouse was highest among older adults aged 65 to 74 (65.1%), but it gradually decreased with age. Conversely, receiving support from a son or daughter showed an increase as they aged. This suggests that as older adults grow older and require more care, they are likely to reside with their sons or daughters, receiving the necessary support (). Meanwhile, with advancing age, there tends to be a greater reliance on outsourced support.

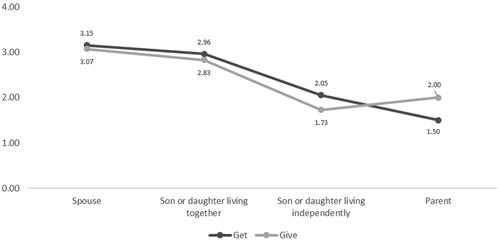

3.2.4. Sufficiency of help

Sufficiency of family help support was applied on a 5-point scale (1: very insufficient − 5: very sufficient) and was found to be insufficient with a rating of near 2 points (), supporting Hypothesis 1. Among family members, the son or daughter living together (2.40 points), the parent (2.33 points), and the care from a spouse (2.25 points) showed similar levels of help. But instances of the son or daughter living independently (2.14 points), and outsourcing external help resources (nursing services, caregivers, etc.) (2.02 points), were relatively low.

Table 4. Sufficiency of help from family.

3.2.5. Exchange of help

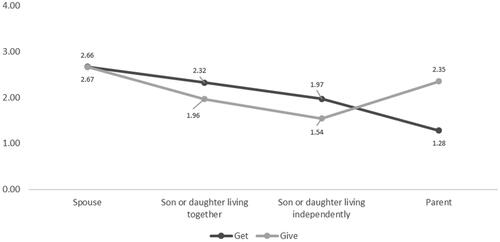

3.2.5.1. Instrumental (cleaning, meal preparation, laundry) support

Although older adults were receiving care from their families, almost an equal level of help exchange occurred between families. Instrumental exchanges: house cleaning, meal preparation, washing, etc., were most active at the same level between spouses and the son or daughter living together. On the other hand, the parent received more support, and the son or daughter who lived independently gave more support to older adults ().

3.2.5.2. Physical (nursing, caring, hospital accompaniment) support

The gap with help exchange in physical support: care, nursing, hospital accompanying, etc., was widened between family members, and care exchange showed lower than the instrumental exchange (). Older adults received more support for their physical help with the son or daughter instead of giving, but with the spouse, it was an almost equal level of help exchange. In a similar sense, older adults are more likely to provide support to their parents than to receive it, creating a care cycle where they, in turn, receive support from their son or daughter. Even if they were vulnerable and needed to be supported, it can be seen that the family has a complementary relationship, rather than a one-sided relationship.

3.2.6. Subjective evaluation of current life by type of family caregivers

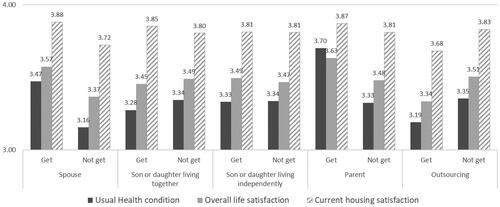

With a t-test, the subjective evaluation of older adults’ current life by type of family caregivers: the relationships between the self-reported health status, satisfaction with overall life, and satisfaction with current housing were analysed. The results for each type are as follows ().

Figure 6. Subjective evaluation of current life by type of family caregivers (points).

Note. Each item was measured on a 5-point scale.

Self-reported health status: (1) Bad, (2) Poor, (3) Fair, (4) Good, and (5) Excellent.

Satisfaction with overall life: (1) Not satisfied at all, (2) Not satisfied, (3) Fair, (4) Satisfied, (5) Very satisfied.

Satisfaction with current home: (1) Not satisfied at all, (2) Not satisfied, (3) Fair, (4) Satisfied, (5) Very satisfied.

3.2.6.1. Support of spouse

The relationship between the spouse and all types of subjective evaluation of current life was higher than not getting support from the spouse. Also, there was a statistically significant difference between the self-reported health status (t = −18.127, p = .000), satisfaction with overall life (t = −14.664, p = .000), and satisfaction with the current house (t = −11.796, p = .000).

3.2.6.2. Support of son or daughter living together

Getting a support group was rated lower than not getting a support group by the son or daughter living together in self-reported health status. In general, there was not much difference in satisfaction with the current home. The differences were significant in self-reported health status (t = 2.760, p = .006), and current housing satisfaction (t = −2.508, p = .012).

3.2.6.3. Support of son or daughter living independently

This also showed low satisfaction, like living together with the son or daughter. Comparing the relationship between the subjective evaluation of current life: self-reported health status, satisfaction with overall life, and satisfaction with current housing, an independent sample t-test showed that there was no significant difference at p < .05.

3.2.6.4. Support of parent

There were significant differences in the parent’s relationship between self-reported health status (t = −6.290, p = .000) and satisfaction with overall life (t = −3.161, p = .002). Getting support from parent showed higher satisfaction than the group not getting parental support, and the satisfaction was higher than getting support from other types of family caregivers.

3.2.6.5. Support of outsourcing

Getting support from an outsourcing support group showed lower satisfaction than not getting support from outsourcing, and had the lowest satisfaction, compared with the other types. There were significant differences in all items, self-reported health status (t = 6.209, p = .000) satisfaction with overall life (t = 8.021, p = .000), and satisfaction with the current house (t = 7.291, p = .000). Support from external resources (such as care, nursing services, etc.) negatively affected satisfaction with current life, rather than the type of family caregiver.

Older adults were aware that the contributions of the spouse and the son or daughter who lived together were high among family caregivers. However, combining the results, the sufficiency of help was not recognised as being as good as they got supported. In the subjective evaluation of current life, the lowest score was given to the son or daughter living together, except for the outsourcing group. In contrast, the highest satisfaction was the parent’s group, who perceived a relatively low contribution in the exchange of help. The findings indicate that the amount of sufficient family care support does not relatively increase the satisfaction of the current life of older adults, which gives a different point of view about the relationship in between family care.

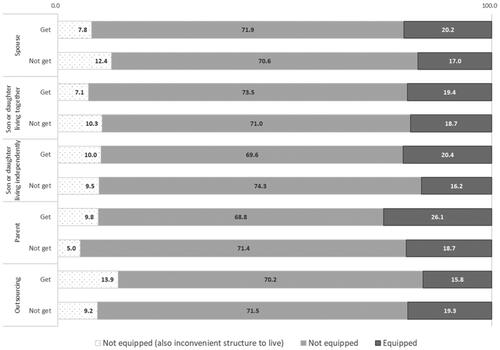

3.3. Condition of current housing

The condition of current housing outlines three categories to assess the housing conditions for older adults, emphasizing the importance of elderly-friendly settings. The ‘Not equipped (also, inconvenient structure in which to live)’ category refers to houses that lack elderly-friendly design and facilities, making it challenging for older adults to live comfortably and safely. These houses may suffer from structural inadequacies, such as insufficient living space, inadequate room functionality, and the absence of essential amenities, like private kitchens and toilets. Additionally, they lack safety and comfort features that could mitigate risks such as falling, and enhance the living environment for older adults. This categorization highlights housing that due to its design and structural features, is fundamentally unsuitable for older adults. Meanwhile, under the category of the ‘Not equipped’: Housing, the housing classified, while not explicitly designed with elderly-friendly facilities (like ramps and safety handles), does not present structural inconveniences to older adults. These houses may lack specialised modifications for older adults, but do not inherently pose challenges to the daily living of their occupants. While the housings are not tailored for older adults, they do not significantly hinder their mobility or safety. Finally, the ‘Equipped with elderly-friendly facilities’ category encompasses homes specifically modified or designed with the needs of older adults in mind. These modifications can include removing thresholds, installing ramps for easy access, slope control for safer navigation, and the addition of handles and safety features in critical areas like bathrooms and hallways, to support the independence and safety of older adults.

3.3.1. Elderly-friendly housing equipment

Most older adults lived in houses that were not equipped (71.4%) with elderly-friendly facilities: threshold removal, slope control, handle installation, etc., supporting easy access. Only 18.8% of respondents agreed that the current house was equipped with elderly-friendly settings ().

Table 5. Condition of current housing.

3.3.2. Subjective evaluation of current life by condition of current housing

There were significant differences in the usual health status, satisfaction with overall life, and satisfaction with current housing through an F-test (). All the subjective evaluations of current life were relatively higher when the current housing was equipped in an elderly-friendly setting. However, it is notable that there was not much difference between the ‘not equipped’ and ‘equipped’ groups. Among the evaluation items, the self-reported health status was relatively low in all kinds of satisfaction. However, the average satisfaction with the house currently lived in was 3.71 points (out of 5 points), which showed satisfaction higher than medium (3 points), so it partially rejects Hypothesis 1.

Table 6. Subjective evaluation of current life by condition of current housing.

3.3.3. Relationship between condition of current housing and type of family caregiver

Through cross-analysis, a significant difference was found in all types of family care, as in . Most older adults lived in a house that was not equipped as an environment for older adults. Comparing the type of family caregiver, the parent (26.1%) group was higher than the other groups for the equipped elderly-friendly housing, and the outsourcing group was higher (13.9%) for the not equipped elderly-friendly housing (also, inconvenient structure in which to live) than others. In addition, the not getting cared for by their spouse’s group was also higher (12.4%).

Figure 7. Relationship between the condition of current housing and type of family caregivers (%).

Spouse (x²= 65.594, p = .000).

Son or daughter living together (x²= 14.610, p = .001).

Son or daughter living independently (x²= 29.431, p = .000).

Parent (x²= 11.746, p = .003).

Outsourcing (x²= 31.619, p = .000).

3.4. Housing and care needs

In terms of continuity of living in their community, older adults’ needs for home modification and care services were as follows.

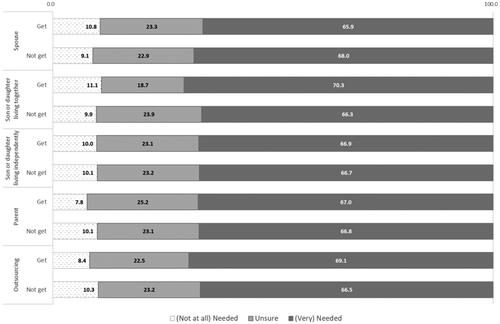

3.4.1. Needs for home modification

There was a significant difference in the needs for home modification according to the condition of current housing with the F-test (). The not equipped (also, inconvenient structure to live in) group (3.72 points) showed the highest home modification needs. But overall, the scores were almost the same as the equipped group (3.62 points), especially in the not equipped group (3.65 points). In addition, considering that the total mean was 3.7 points, the difference was very small, so there was no difference in special housing modification needs between the groups.

Table 7. Needs for home modification by the condition of current housing.

Regarding cross-analysis of the needs for home modification, there was a significant difference in the types of spouse and son or daughter living together according to the type of family caregiver (). Among the type of family caregiver, getting the support of son or daughter living together (70.3%) was the highest, while getting the support of spouse (65.9%) was the lowest. In addition, although there was no significant difference, not getting support from the spouse and outsourcing getting support group showed higher needs for home modification than others. However, over 65% of respondents in all groups preferred to have home modifications that support Hypothesis 2.

Figure 8. Needs of Home modification by type of family caregivers (%).

Note. This was measured on the 5-point scale (1 = not needed at all, 2 = not needed, 3 = unsure, 4 = needed, 5 = very needed), but the results were compared by simplifying it to a 3-point scale (not at all) needed, unsure, and (very) needed.

Spouse (x²= 8.806, p = .012).

Son or daughter living together (x²= 19.154, p = .000).

3.4.2. Needs for care services based on government

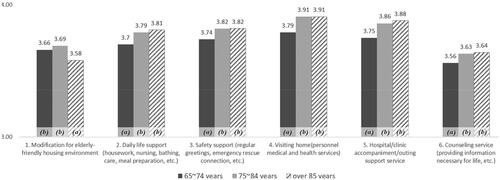

shows older adults’ needs for care services the government provides in terms of three age types. Overall, the preference of all items was over 3.5 points (based on 5 points). As older adults age, the need for all kinds of services increased, except for housing modification. Regarding preference, housing modification and the counselling service showed a lower preference than other services. However, a high preference for older adults was visiting home for personal medical and health care. Consequently, providing those health and safety management services, the housing environment for older adults should be equipped for more delicate care environments.

Figure 9. Needs for care service based on government (points).

Note. Means measured on 5-point scale (1: not needed at all − 5: very needed).

(Alphabet) subscripts below to bar graph refer to homogeneous subsets by Duncan’s Post hoc tests (p<.05) (a < b).

¹(F= 4.320, p< .05), ²(F= 10.753, p< .001), ³(F= 8.792, p< .001), ⁴(F= 20.267, p< .001), ⁵(F= 19.421, p< .001), ⁶(F= 7.165, p< .001).

4. Discussion

This study undertook a thorough examination of family care dynamics, housing convenience, and the demand for housing support among older adults, with the aim of formulating a sustainable care plan for community living. The data substantiated several of our hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The majority of older adults expressed dissatisfaction with family care and living conditions. This was evident in the relatively low average sufficiency rating of 2 out of 5 points for family care. Notably, those receiving care from spouses or children exhibited a slightly higher proportion, but with lower sufficiency levels, compared to other family caregivers. Gender differences were also striking, with husbands receiving more spousal care support than wives. Furthermore, a significant proportion of older adults, particularly women, who received no familial help, demonstrated lower satisfaction levels. These findings align with prior research indicating gender disparities in care support benefits (Ham & Hong Citation2017; Jeong et al., Citation2020; Namkung, Citation2019; Turcotte, Citation2013; Wanless, Citation2006; WHO, Citation2017, Citation2020).

However, satisfaction with their current housing averaged 3.7 out of 5 points, indicating a higher level than the median. This leads to the partial rejection of Hypothesis 1, suggesting that older adults generally express content with their current housing situations. Considering that a substantial 71.4% of older adults reside in areas lacking care equipment, it is evident that there is a preference for remaining in familiar environments rather than modifying their homes or relocating for improved care provisions. This trend aligns with previous studies that emphasise the continuity of older adults’ living arrangements (Atchley, Citation1989; Lee et al., Citation2021; MOLIT, Citation2021a). Additionally, it seems to reflect a perception of the minimum housing standard, such as inadequate heating, outdated wallpapering, and the need for flooring replacements, rather than prioritizing amenities specifically tailored to older adults (Hwang et al., Citation2022).

While subjective evaluations of current life were generally similar across all assessment levels, those without family support displayed lower satisfaction levels in overall life, health status, and current housing. Interestingly, those without outsourcing support reported even higher levels of satisfaction across these metrics. Conversely, older adults receiving support from spouses or parents demonstrated relatively high ratings. This underscores the significance of reciprocal care exchanges within family relationships.

Hypothesis 2: The preference for government care support services and home renovation for sustainable living at home was affirmed. Over 65% of older adults expressed a significant need for improved housing environments to support sustainable community living. Only a small fraction, approximately 10% or less, viewed elderly-friendly facilities as unnecessary.

However, despite this strong demand for improved housing conditions, satisfaction levels with the current housing situation remained relatively stable, ranging from 3.6 to 3.9 out of 5 points, irrespective of the presence of accessibility features. This suggests a complex interplay between the perceived convenience of current housing and the desire for improvements.

The most favoured care support service among older adults was personalised medical and health services delivered at home. Interestingly, with advancing age, the demand for housing support increased, but the desire for home modification for enhanced daily convenience did not follow suit. This indicates a preference for receiving care support through home services, even in cases where housing modifications may be beneficial, reaffirming previous research findings (Lee et al., Citation2021). These outcomes align with the inclination of older adults to age in familiar environments (Atchley, Citation1989).

However, the prevalence of home-based medical and health care services underscores the heightened need for optimised housing conditions to effectively meet the care requirements of older adults.

4.1. A research question

Do you think older adults are well cared for in family and residential settings?

While many older adults acknowledge a deficiency in family care, and recognise the need for home modifications to facilitate accessibility, there is a consistent inclination to remain in their existing residences, even in the face of inconveniences. This inclination is rooted in a desire to stay in familiar surroundings, influenced by concerns such as renovation costs and the challenges of managing a household alone. Notably, older adults living with their children exhibit the highest demand for housing modifications, warranting a closer examination of their specific needs and motivations. This includes exploring whether modifications are geared towards promoting independent activities or facilitating shared household responsibilities, ultimately enhancing daily living ease.

In contrast, older adults receiving outsourcing support, rather than familial assistance, register the lowest satisfaction levels across various metrics, highlighting a substantial need for care, including home modifications and daily life support. Conversely, those supported by parents or spouses, despite experiencing lower sufficiency levels of assistance compared to other family caregivers, exhibit higher levels of satisfaction in their subjective evaluations of current life. This finding emphasises the significance of reciprocal care exchanges within familial relationships. Ultimately, quality care transcends one-sided beneficiary relationships, with even minimal mutual support leading to enhanced satisfaction with life and health. It is imperative that housing environments foster the independence of older adults in daily life, while also enabling support from family caregivers. Prioritizing effective communication between older adults and their families should be a cornerstone of any care plan.

4.2. Implication for practice and research

The findings from this study provide significant insight with profound implications for both practical applications and societal welfare, emphasizing the necessity of comprehensive strategies to enhance the care of older adults at home and strengthen the support network for their caregivers. By focusing on sustainability, we ensure that improvements in family caregiving capacity are not only beneficial in the short term but also contribute to long-term resilience and adaptability. Firstly, adapting services to meet the specific needs and preferences of caregiving families and older adults is essential for achieving sustainable care continuity. This approach involves considering gender differences and ensuring that care solutions are adaptable to changing circumstances. Such flexibility promotes sustainability in care provision and aligns with SDG 5 (Gender Equality), which advocates for equal opportunities and access to care regardless of gender. Secondly, advocating for financial support measures, such as subsidies or tax benefits for home modifications, addresses economic sustainability by reducing the long-term financial burden on families and the state. This supports SDG 1 (No Poverty) by alleviating financial stress on families and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by promoting modifications that make homes safer and more accessible, contributing to the sustainability of urban and rural areas.

Thirdly, the creation of dedicated caregiving spaces within homes not only meets immediate safety and independence needs but also contributes to sustainable living environments. This effort is directly linked to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), which focuses on making human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Fourthly, the integration of technology through telehealth services, smart home technologies, and digital platforms is crucial. These technologies enhance the sustainability of healthcare access and improve living environments in a scalable and efficient manner, supporting SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by improving access to health services and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by fostering innovation in caregiving technologies. Lastly, the provision of economic incentives for caregiving families should be viewed through the lens of sustainability. These incentives are designed to build long-term capacity and reduce reliance on institutional care settings. This strategy directly aligns with SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by ensuring that all families, regardless of economic status, have access to necessary resources, and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), which calls for multi-sectoral partnerships to support sustainable development. Overall, these strategies and insights underline the imperative to integrate sustainable practices in the caregiving sector, ensuring that care solutions not only address current needs but are also viable long-term. By explicitly tying these strategies to the SDGs, this research contributes to a global framework, advocating for systemic changes that support the aging population effectively within their communities, thus enhancing the quality of life for older adults and their families and contributing meaningfully to global sustainability efforts (UN, Citation2024).

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the care status and housing needs of older adults receiving support from their families, deriving actionable policy implications for aging in place that facilitate their integration into the community. Our findings revealed that a significant proportion of older adults perceive family care as inadequate, highlighting a critical need for enhanced support structures and resources. There is also a strong preference for elderly-friendly housing environments that are integrated with care services, underscoring the necessity to create accessible and safe living spaces that cater to their diverse needs.

The central role that families play in providing care is profound, and the quality of care is directly linked to the availability and quality of family care resources. The significance of fostering complementary relationships within families, particularly in caregiving dynamics, is evident. Recognizing the interplay between dependence and autonomy is crucial in navigating potential conflicts and burdens that may arise. Community-based family care centers can play a pivotal role in mediating these relationships and offering support to alleviate the burden of caregiving. Therefore, it is imperative to establish elderly-friendly environments that not only facilitate the provision of care services within the comfort of one’s home but also promote sustainability and resilience. These environments should support the physical, emotional, and social well-being of older adults, ensuring they can live independently and with dignity.

The study’s recommendations align with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Good Health and Well-being (SDG 3): By enhancing elderly care, this study directly contributes to promoting better health and well-being among older adults. Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11): Advocating for elderly-friendly and accessible housing supports the creation of safe and inclusive urban environments for seniors. Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10): This study addresses the diverse needs of caregiving families across socioeconomic backgrounds, helping to reduce inequalities. Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17): Highlighting the need for multi-sectoral partnerships enhances elderly care systems and supports the broader SDG agenda.

Moving forward, government initiatives should focus on establishing comprehensive community hubs that provide integral support for both older adults and their families. These should include efforts to enhance the housing environment to enable in-home care services and develop a skilled workforce to effectively operate these hubs. Targeted education campaigns to raise awareness about the importance of elderly-friendly environments are essential, benefiting not only older adults but all community members.

A limitation of our study is its reliance on secondary data obtained from nationwide surveys conducted by the government on older adults. This imposes constraints on our ability to delve into specific individual characteristics. While this study primarily focused on older adults receiving support from family caregivers in South Korea, it lays a valuable foundation for future research. We propose conducting an in-depth analysis of the distinct demands and motivations associated with various housing needs, as indicated in our analytical findings. This could particularly benefit older adults who are cohabiting with their children and have significant needs for home improvements. Further exploring the perspectives and needs of family caregivers would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the caregiving dynamic and could yield nuanced insights for tailored support strategies.

By linking these findings to sustainable development goals, this research contributes valuable insight into older adults’ care and housing preferences, offering practical implications for policy, education, and research. By prioritizing elderly-friendly housing environments and strengthening support structures, we aim to enhance the well-being and quality of life for older adults and their families, positively contributing to sustainable development objectives globally.

Geolocation information

Country: Korea, Republic of Region: Chungcheongbuk-Do City: Cheongju-si Latitude: 36.632473380701° N Longitude: 127.453143013° E.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Korean Elderly Survey 2020 Micro-data at https://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/kor/databank/DatabankDetail.html, National Statistics Korea No. 117071.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yoonseo Hwang

Yoonseo Hwang, Ph.D., is a Research Associate at the Institute of Human Ecology at Chungbuk National University in the Republic of Korea. Her work focuses on creating aging-friendly environments and educational content for socially vulnerable groups, especially older adults. She leads a project on older adults’ housing issues and their relationships with caregiving family members. Additionally, she is expanding her research to explore lifetime home design and housing services for all generations.

Hyun-Jeong Lee

Hyun-Jeong Lee is Professor of the Department of Housing and Interior Design at Chungbuk National University in South Korea. She received her PhD degree in Housing from Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, United States. Her recent research interests include housing welfare, housing affordability, public housing residents, young persons’ housing, housing education and information programs, and accessibility.

Notes

1 Minimum Housing Standards: These are the standards set and announced by the Minister of Construction and Transportation for the minimum level of housing that citizens must live in. These standards serve as a means for the government to realise its policy goal of ensuring the minimum level of residential living for the people. They encompass criteria for the structure, performance, and environment of houses, taking into account the minimum living area for each household composition, the number of rooms for each purpose, standards for essential facilities, such as a dedicated kitchen and bathroom, and safety and comfort. The government gives priority to households that do not meet the minimum housing standards by providing housing or supporting improvement funds.

2 Activities of daily living (ADL) refers to capacities required for personal care, including walking, dressing, bathing, using the toilet, transferring from the bed to a chair, grooming, and eating Hardy, Citation2014).

3 Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) is to be more inclusive of the range of activities that support independent living in attempts to assess everyday functional competence, such as the ability to use the telephone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, mode of transportation, responsibility for medications, ability to handle finances Lawton & Brody, Citation1969).

4 Bathroom modifications (such as shower booths or bathtubs, and safety handles next to toilets), kitchen or laundry room modifications, mobile modifications (lamp installation, stair modification, lift, entrance extension or wall removal, and handrail installation from the entrance).

References

- Ahn, S., Seo, S., Kim, B., Lee, K., & Kim, Y. (2016). Emergency department-based injury in-depth surveillance data, 2006-2015. Public Health Weekly Report, 9(33), 1–21.

- Altman, B. M., & Barnartt, S. N. (2014). Environmental contexts and disability. Research in social science and disability (Vol. 8). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- American Geriatrics Society, Geriatrics Society, American Academy Of, Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel On Falls Prevention. (2001). Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49(5), 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49115.x

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2011). Our Health at Risk: Stress in America 2011. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2011/health-risk

- Atchley, R. C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/29.2.183

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ). (2022). Einsatz pflegender Angehöriger in der Pandemie stark gestiegen. https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/aktuelles/alle-meldungen/einsatzpflegender-angehoeriger-in-der-pandemie-stark-gestiegen-199344

- Carnemolla, P., & Bridge, C. (2019). Housing design and community care: how home modifications reduce care needs of older people and people with disability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11), 1951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111951

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Factsheet: Risk factors for falls. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/steadi-factsheet-riskfactors-508.pdf

- Chan, A., Malhotra, C., Malhotra, R., Rush, A. J., & Østbye, T. (2013). Health impacts of caregiving for older adults with functional limitations: Results from the Singapore survey on informal caregiving. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(6), 998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264313494801

- Cho, J., Oh, S., & Yang, C. (2011). A comparative study on the attitudes and behaviors of supporting for the elderly in East Asia: Focused on Korea, Japan, China and Taiwan. Korean Journal of Social Issues, 13(1), 7–42.

- De Korte-Verhoef, M. C., Pasman, H. R. W., Schweitzer, B. P. M., Francke, A. L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., & Deliens, L. (2014). Burden for family carers at the end of life; a mixed-method study of the perspectives of family carers and GPs. BMC Palliative Care, 13(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-13

- Ham, S., & Hong, B. (2017). The relationship between formal care and informal care: Focusing on home care service for older adults. Korean Journal of Social Welfare, 69(4), 203–225. https://doi.org/10.20970/kasw.2017.69.4.008

- Hardy, S. E. (2014). Consideration of function & functional decline. In B.A. Williams, A. Chang, C. Ahal, H. Chen, R. Conant, C. Landefeld, C. Ritchie, & M. Yukawa (Eds) Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Geriatrics. McGraw Hill.

- Hwang, E., Cummings, L., Sixsmith, A., & Sixsmith, J. (2011). Impacts of home modifications on aging in place. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 25(3), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2011.595611

- Hwang, G., Kim, J., Lee, M., & Kim, N. (2015). A study on the residential protection system for older people centered on the community. Welfare Foundation.

- Hwang, Y., Jung, M., Kim, M., Choi, R., & Jun, E. (2022). Policy issues for modification and new construction of the age-friendly housing expansion in rural areas. In Proceedings of Autumn Annual Conference of Korean Housing Association, Vol.34, No.1 (pp. 414–417).

- Hwang, Y., Lee, H., & Jun, J. (2023). Home modification status and needs of older adults households for sustainable living in the community: Focused on the Korea Housing Survey 2020. Journal of the Korean Housing Association, 34(2), 055–066. https://doi.org/10.6107/JKHA.2023.34.2.055

- Jeong, G., Kim, Y., Hong, S., Bae, H., Kim, S., & Kim, B. (2020). The current status of family caregiving for older adults and strategies to help families through community care from gender perspective. Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- Kim, S., & Kim, Y. (2020). National health insurance statistical yearbook. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service & National Health Insurance Service.

- Kim, Y. (2018). Recent challenges and the government strategies for senior housing services in Sweden. Global Social Security Review, 6, 105–112.

- Kim, Y. (2020). The reality of Korea’s work-family balance in COVID-19 is whether it will end with a crisis or turn into an opportunity for change. Monthly Public Policy, 174, 56–59. https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE09325550

- Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute. (2021). 2021 Disability statistical yearbook. Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute. https://www.koddi.or.kr/data/research01_view.jsp?brdNum=7411509

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) Data Portal. (2021). Microdata of older people survey 2020. https://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/main

- Korean Law Information Center. (2012). Enforcement decree of the act on support for the residential weaknesses, such as persons with disabilities and the elderly. Korea Ministry of Government legislation. https://glaw.scourt.go.kr/wsjo/lawod/sjo190.do?contId=3257744#1695744047183

- Lawton, M. P., & Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In C. Eisdorfer, & M. P. Lawton (Eds), The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 619–674). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10044-020

- Lawton, M., & Brody, E. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist, 9, 179–186. http://www.eurohex.eu/bibliography/pdf/Lawton_Gerontol_1969-1502121986/Lawton_Gerontol_1969.pdf

- Lee, H. (2021). Installation of limited ‘house for the weak’ convenience facilities. Able News. https://www.ablenews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=97070

- Lee, Y. (2014). Trends in older people households and their policy implications: 1994 ∼ 2011. Health and Social Welfare Review, 211, 45–54.

- Lee, Y., Kang, E., Kim, S., & Byeon, J. (2017). A study on the reform plan of the long-term care system for older people aging in place. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affair.

- Lee, Y., Kim, S., Hwang, N., Lim, J., Joo, B., Namgoong, E., Lee, S., Jeong, K., Kang, E., & Kim, G. (2021). Survey on older people 2020. Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). (2018). Community integrated care basic plan: (Step 1) Focusing on older people community care. MOHW.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). (2020). Local community integrated care self-promotion guidebook. MOHW.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). (2021a). Korea housing survey 2020: Statistical report. MOLIT.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). (2021b). Korea housing survey 2020: Research report of households with special characteristics. MOLIT.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). (2022). Press release: Results of the Korea housing survey 2021.

- Namkung, E. (2019). Expansion of federal and state programs for family caregivers in the US: Implications for Korea. Global Social Security Review, 11, 76–87.

- Namkung, E. H., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick, M. R. (2017). Well-being of sibling caregivers: Effects of kinship relationship and race. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw008

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2016). Families Caring for an Aging America., National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23606

- National Rehabilitation Center. (2020). Older people care services continue despite COVID-19. https://url.kr/z9et86.

- National Research Council for Economics, Humanities and Social Sciences (NRC). (2022). Current status of elderly women’s quality of life and policy tasks to support it preparing for a super-aged society: Care and housing. NRC.

- Perez, F. R., Fernandez, G. F., M. Rivera, E. P., & Abuin, J. M. R. (2001). Ageing in place: Predictors of the residential satisfaction of elderly. Social Indicators Research, 54(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010852607362

- Schulz, R., & Eden, J. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. National Academies Press. https://www.johnahartford.org/images/uploads/reports/Family_Caregiving_Report_National_Academy_of_Medicine_IOM.pdf

- Seo, H. (2022). Issue in: Might not be able to get the national pension from those born in 1990. “Is that really going to happen. Yonhapnews. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20220324106700501

- Statistics Korea. (2019a). Press release: World and Korea population status and outlook reflecting the special projection for the future population 2019.

- Statistics Korea. (2019b). Press release: Future household forecast: 2017–2047.

- Statistics Korea. (2021). Press release: Statistics for older people 2021. https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=c37cb45a7d2916f2d2e0c17e44f3cdcbc4504d43e5c4f47fc7876cced98dc872&rs=/synap/preview/board/10820

- Statistics Korea. (2022). Press release: Statistics for older people 2022. https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=44fc580646bd977f4b72b1e4523aeb799f43db0045f93b133958e4cb6ca69ae6&rs=/synap/preview/board/10820

- Statistics Korea. (2023). Press release: Statistics for older people 2023. https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=0750aaf2f8f7c6745fdfcbda0896a6f2b763bf27561c1282e1aaa9bf3137face&rs=/synap/preview/board/10820

- Turcotte, M. (2013). Insights on Canadian society-family caregiving: What are the consequences? Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11858-eng.pdf?st=IDJ8XS88

- United Nations (UN). (2019). World population ageing 2019 - Highlights. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf

- United Nations (UN). (2024). Sustainable development goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals

- United Nation Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) (2022). Press Release: Recognize reality of a rapidly ageing Asia-Pacific region and revitalize the role of older persons in society, urges UN forum.

- Wanless, D. (2006). Securing good care for older people: taking a long-term view. King’s Fund.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43755/9789241547307_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). Integrated care for older people (ICOPE) Guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550109

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Integrated care for older people: realigning primary health care to respond to population ageing. Technical Series on primary health care. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326295/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.44-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Aging and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Yeom, J. (2019). The change of household type among older people and the response of long-term care policy. The Journal of Korean Long Term Care, 7(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.32928/TJLTC.7.1.4

- Yi, M. G. (2019). Care burdens, depression and suicidal ideation among family caregivers of persons with disabilities? A focus on the moderated mediation effects of care services. Korea Academy of Disability and Welfare, 44(44), 121–148.

- Yu, B., & Kim, N. (2014). Older people living, nursing facility system and case study. Gyeonggi Welfare Foundation.