Abstract

The present study examines the relationship between state anxiety, trait anxiety, and social anxiety among students enrolled in a private university in South Lima. The research design employed was correlational, utilizing a nonexperimental cross-sectional approach. The sample consisted of 449 male and female university students, aged 18 to 30, enrolled in psychology and law programs from the third to eleventh cycle. The participants completed an online survey utilizing two validated instruments: the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Social Anxiety Questionnaire for Adults (CASO-A30). Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed for the purpose of data analysis. The findings indicated a stronger correlation between state anxiety and social anxiety than between trait anxiety and social anxiety. The mean scores for state anxiety and trait anxiety were both moderate, with trait anxiety exhibiting a slightly higher mean score. Approximately 29.84% of students reported high levels of state anxiety, while 25.39% reported high levels of trait anxiety. Significant differences were observed in anxiety levels based on age, career, and study cycle, but not on gender. In conclusion, this study demonstrated a positive and highly significant correlation between state anxiety, trait anxiety, and social anxiety among university students. State anxiety exhibited a stronger association with social anxiety than trait anxiety.

1. Introduction

Social anxiety is the third most prevalent mental health issue globally, following affective disorders such as depression and the consumption of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and marijuana. Lazarus & Folkman (Citation1984) posit that anxiety is the perception of a threat in one’s social environment, which is perceived as dangerous for one’s psychological wellbeing. In contrast, Beck et al. (Citation1985) posit that anxiety is an unpleasant emotional state that is experienced in the face of specific stimuli, individuals, objects, social situations, or assumptions. This concept frequently leads to the understanding of anxiety as a normal and necessary response, or alternatively, as a maladaptive response, also referred to as pathological anxiety. Nevertheless, it is beneficial to distinguish between these two conceptions, as pathological anxiety is more prevalent, intense, and persistent than normal anxiety (Spielberger & Diaz-Guerrero, Citation2007).

Spielberger (Citation1972) presents a comprehensive understanding of anxiety, defining it as an emotional state of transition or organic condition of the individual. This state increases and decreases in intensity and fluctuates over time. It is characterized by the conscious perception of feelings of apprehension and tension, as well as a great activity of the autonomic nervous system. This anxiety will manifest itself in the person, depending on their own perception, on their subjective way in which they perceive danger, according to their ability to symbolize a situation. According to García-Fernández et al. (Citation2013), epidemiological studies show that this problem generates a condition in at least 18% of children between 3 and 14 years of age, which qualifies it as a relatively frequent situation in this population. A recent study conducted by Botero & Delfino (Citation2020) on 117 university students between the ages of 18 and 25 from the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires revealed that 53.8% exhibited high state anxiety and 36.8% displayed high trait anxiety. A similar study conducted among 141 university students in Seville yielded comparable results, with 53.2% of participants exhibiting anxiety. Of these, 8.5% were classified as experiencing ‘serious’ anxiety, while 12.8% were categorized as ‘extremely serious.’

It is important to note that social anxiety is not merely a normal emotion; it is also a useful, necessary, and adaptive one. Social anxiety motivates individuals to behave and act in certain ways in new and important interpersonal situations. Bottle (Citation2001) highlights this aspect of social anxiety as a factor of adaptation of the person to their environment. Posture, which facilitates its study and clinical approach, since it is not considered a complex problem that affects people. Instead, it is viewed as a relatively straightforward issue that can be managed effectively when it is kept in check. However, when it overflows, becoming unmanageable, chronic, and limiting for the person, it can suggest that the social anxiety has become a mental disorder, in a social anxiety disorder.

The consequences of excessive social anxiety can be profound and diverse, particularly during the adolescent and young adult stages, when a multitude of demands emerge, primarily at the academic and social levels (Basantes et al., Citation2018). Additionally, psychophysical and emotional changes can give rise to transient mood swings. Furthermore, concerns are a significant contributing factor to the emotional and frequent fluctuations observed in individuals within this developmental stage (Santos & Vallín, Citation2018). These pressures frequently result in suboptimal academic performance, non-attendance, and even the abandonment of studies. Furthermore, the onset of mood disorders, addictive behaviors, and the abuse of toxic substances can result in greater social isolation and a loss of interest in studies (Restrepo et al., Citation2021).

This situation is further compounded by the fact that in our country, mental disorders and neuropsychiatric diseases rank first with an incidence of 17.5%, which is significantly higher than that of traffic accidents, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, respiratory infections, nutritional deficiencies, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (MINSA, Citation2014). Recent studies have confirmed that the onset of social anxiety occurs in middle adolescence, between the ages of 15 and 16, just when young people begin their university life and are exposed to high academic demands (Basantes Moscoso et al., Citation2021); Similarly, Santos & Vallín (Citation2018) and Bermúdez (Citation2017) corroborate the above, stating that anxious disorders diagnosed in the adult population usually have their origin in adolescence, since they do not have the necessary tools and social skills. In order to cope with the distress caused by their environment, adolescents often turn to inappropriate coping mechanisms in an attempt to manage the typical discomforts associated with this stage of life. These include the consumption of substances such as alcohol and other drugs, including tobacco and marijuana. It is imperative to identify and intervene early on any non-adaptive manifestations of social anxiety.

In light of the aforementioned factors, it is not uncommon for university students to experience high levels of anxiety throughout their academic careers. These students are required to engage in a number of challenging activities, including public speaking, interacting with unfamiliar individuals, communicating with the opposite sex, assertively expressing displeasure and fear of ridicule, and navigating the complexities of a new educational and professional environment. These factors, among others, can contribute to elevated anxiety levels among college students. It is also important to consider that in Peru, there are approximately 9 million young people between the ages of 16 and 30. Of these, 35.8% have higher education, with 21.5% pursuing university studies and 14.3% pursuing technical education. This leads us to conclude that our country currently has a university population of approximately two million students. Seventy percent of students attend private universities, while 30 percent attend public universities (2018). Spain, for its part, presents one of the highest rates of access to university and non-university tertiary education (63.7%), which is higher than the average of the countries belonging to the OECD (50.8%), the European Union (50.1%), Sweden (41.2%), and Chile (71.4%), in a population under 25 years of age (OECD, Citation2023).

As Sánchez et al. (Citation2004) have observed, it is imperative to recognize that anxiety states are an adaptive and transitional process. This process begins with the student’s perception of the stimuli they receive, both internal and external. Trait anxiety is defined as the tendency or genetic, latent, and stable predisposition to recognize harmless situations as a danger. This leads to an exponential increase in the so-called state anxiety, which is defined as the anxious reaction of the autonomic nervous system when faced with a stressful stimulus, generating apprehension, fear, and agitation. Individuals with a high level of trait anxiety exhibit personality types that are the result of hereditary, temperamental, and biological factors. These individuals tend to perceive internal stimuli as dangerous, stressful, and threatening towards their person. Conversely, if these stimuli elicit the same response, but due to transient and external circumstances, we could posit that we are dealing with a personality type exhibiting state anxiety. It is possible for individuals with high levels of trait anxiety, such as state anxiety, to develop this condition in young university students. This can result in an increase in their levels of social anxiety, which activates the necessary learned mechanisms in order to reduce or eliminate it (Guevara-Cordero et al., Citation2020).

The significance of this research lies in the identification and demonstration of a correlation between the three study variables: state anxiety, trait anxiety, and social anxiety in university students. The principal contribution of this study is to determine which of the two types of anxiety is more closely associated with the third. This study sought to demonstrate, through statistical evidence, whether state anxiety is more closely related to social anxiety than trait anxiety.

2. Materials and methods

Our research is framed in the positivist paradigm and is of the correlational type, which is the most commonly used in studies in psychology, social sciences (including sociology, anthropology, and others), and education. This approach is used to determine the degree of relationship existing between two or more variables within the same sample. The study’s design is non-experimental and cross-sectional, in accordance with (Sánchez & Reyes, Citation2015), as it does not manipulate variables and focuses on observing a reality over a specific period of time, without altering or intervening in it. Its objective is to specify the degree of association or relationship between the variables under study, such as state anxiety, trait anxiety, and social anxiety. The methodology employed is quantitative, as the levels of state, trait, and social anxiety will be quantified in the university participants in the study (Hernández & Fernández, Citation2014).

The study population consisted of 1,800 university students, comprising both sexes and enrolled in the academic programs of psychology and law. The participants were studying undergraduate studies at a private university in South Lima. The selection of the participants was conducted in accordance with the minimum statistical parameters established for research in the social sciences. Thus, with a confidence level of 96%, a margin of error of 4%, an estimation of the percentages of occurrence and the application of the respective formula to establish finite populations, a sample of 449 university students was obtained. Although it is true that 481 forms were answered in their entirety remotely or online, after the data cleaning stage where incomplete or incorrectly answered questionnaires were discarded, 449 questionnaires were found to be valid, corresponding to an equal number of students of both sexes. To calculate the sample, the formula (z2*pq*N/N-1*E2 + z2*pq) was employed, which, according to Lopez (Citation2004), corresponds to a subset of individuals with the main characteristics of the population, serving as representation, for having the characteristics of an acceptable quantity.

The methodology employed was non-probabilistic, for the sake of convenience and not randomized. This is characterized by not being applicable with the same possibility among all participants, as outlined in Otzen & Manterola (Citation2017). With regard to the selection of the final sample, the inclusion criteria were considered to be between the ages of 18 and 30, both sexes, and studying from the third to the eleventh cycle of law and psychology majors. The virtual or online survey method was employed as a data collection technique. This method involves the use of self-application reports, which can be completed remotely or online. According to Basantes et al. (Citation2018), these reports are useful as a source of primary information. This method allows for the implementation of extensive field investigations, with non-probabilistic samples, which enables the objective study of various social variables. The research employs the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Social Anxiety Questionnaire for Adults (CASO-A30) as measurement instruments, both of which have been validated in terms of internal consistency and reliability in the Peruvian population.

To assess the levels of state and trait anxiety variables, the STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) by Spielberger & Diaz-Guerrero (Citation2007) was employed, which comprises 40 items distributed across two self-rating scales. To quantify social anxiety, the CASE-A30 by Caballo & Salazar (Citation2016) was employed, which comprises 30 items and five dimensions: a) speaking in public and interacting with authority figures, b) interacting with strangers, c) interacting with the opposite sex, d) assertive expression of annoyance, disgust, and anger, and e) feeling ashamed or ridiculed. In this manner, subjects respond to each of the statements by indicating their level of agreement on a four-dimensional Likert scale, which ranges from 1 to 4. In the A-State scale, the response options on the Likert scale of intensity are as follows: The response options on the Likert scale of intensity are as follows: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Quite a bit, and 4 = A great deal. In contrast, the options on the frequency Likert scale for the A-Trait scale are as follows: The response options on the Likert scale of frequency are as follows: The response options on the Likert scale of frequency are as follows: 1 = Almost never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Frequently, 4 = Almost always. The dimensions encompass the most crucial high-stress social scenarios for adults across their various contexts of daily life.

Prior to the commencement of the data analysis, a matrix was prepared in the Microsoft Excel 13 program. Subsequently, the questionnaires were subjected to a process of cleaning, whereby all those that were incomplete or answered in an invalid manner were eliminated. This information was then exported to the program for data analysis in the field of social sciences. The quantitative results obtained in the investigation were obtained using SPSS 24. Subsequently, we proceeded to perform descriptive statistical tasks, utilising the arithmetic mean to obtain population averages and the standard deviation to specify the dispersion level of the sample.

Inferential statistics entail the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to ascertain the nature of the distribution of the sample, whether it is normal or not. In inferential statistics, non-parametric statistics are employed, with the Mann-Whitney U test utilized for sex, as this formula is employed to identify significant differences between two independent groups. Similarly, the Kruskal-Wallis ‘H’ test was employed to identify significant differences between three or more groups, as was the case in this study. To assess the correlation between main variables and their dimensions, Spearman’s rho was utilized.

2.1. Ethical approval statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee for Regional Pharmacological Research of Callao Health, which granted approval under Certificate of Approval N°002-2022 COMITÉDEETICA/UI/DIRESACALLAO. All research activities were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects.

2.2. Informed consent statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, with the guarantee of anonymity of their responses. The study’s exclusive research purpose was elucidated in detail, and participants were assured that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without consequence.

3. Results

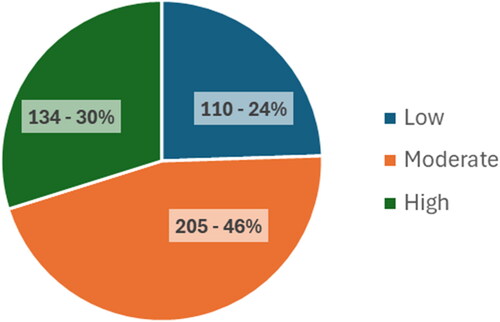

illustrates that 45.66% (n = 205) of the sample exhibits a moderate level of state anxiety, followed by 29.84% (n = 134) at a high level and 24.50% (n = 110) at a low level. The classification is as follows: the low level corresponds to percentile one to 24, the average level is from 25 to 75, and the high level is from percentile 76 to 99.

Figure 1. Frequencies and percentages of state anxiety, Source: Sample questionnaires from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Elaboration: Own.

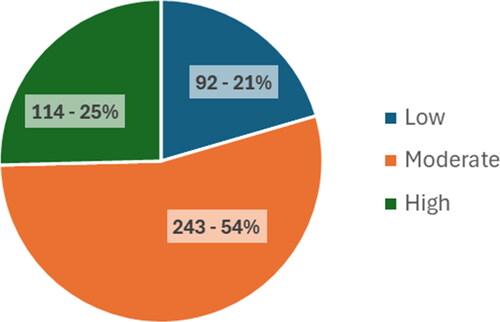

It can be seen, in , that 54.12% (n = 243) of the sample is at an moderate level of trait anxiety, followed by 25.39% (n = 114) is at a high level. Also finding that 20.49% (n = 92) were at a low level.

Figure 2. Frequencies and percentages of trait anxiety.

Source: Sample questionnaires from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Elaboration: Own.

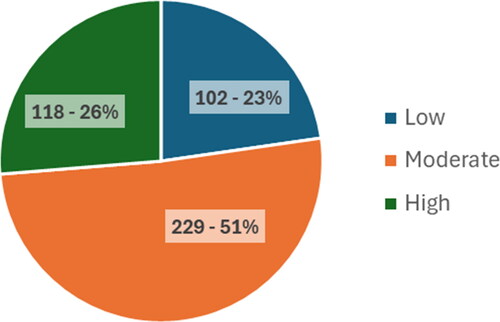

In , it can be seen that 51% (n = 229) of the sample is at an moderate level of social anxiety, followed by 26.28% (n = 118) is at a high level and also found that 22.72% (n = 102) is at a low level.

Figure 3. Frequencies and percentages of social anxiety.

Source: Sample format of the Social Anxiety Questionnaire for Adults (CASE-A30).

Elaboration: Own.

presents the essential descriptive statistics for social anxiety. The mean score is 79.92, with a standard deviation of 24.047. The minimum and maximum scores achieved are 30 and 140, respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of social anxiety and its components Source: Sample format.

The results of the study indicate that one in three university students (29.84%) exhibits a high level of state anxiety, while one in four (25.39%) displays a high level of trait anxiety. The results indicated a positive and highly significant correlation between the three study variables. The association between state anxiety and social anxiety was found to be stronger than that between trait anxiety and social anxiety.

The level of social anxiety in university students was found to be average (M = 79.92). This was observed in 51% of the sample, with the same proportion exhibiting similar levels of social anxiety in its components. It is also noteworthy that the sample exhibited a clear gender imbalance, with a majority of females (64.4%) compared to a minority of males (35.6%).

The study aimed to ascertain the discrepancies observed in the percentages of state anxiety and trait anxiety between the female and male populations. The findings revealed that there were no significant differences in state and trait anxiety according to sex. It can be observed that there were no statistically significant differences (U = The significance values were compared with the theoretical contrast value (p > .05), resulting in the following values: (U = 20901.500; p = .092) and (U = 22915.500; p = .876). However, statistically significant differences were found (X2 = 21.069; p = .000) and (X2 = 30.485; p = .000) when comparing the significance values with the theoretical contrast value (p < .05). The results indicated that students between the ages of 25 and 30 obtained the highest average rank. Similarly, the results of the comparison of state anxiety and trait anxiety according to race demonstrated statistically significant differences (U = 14667.000; p = .000) and (U = 16822.500; p = .000) when comparing the values of significance with the theoretical contrast value (p > .05). The law degree was associated with the highest score. In contrast, the comparison according to the study cycle revealed statistically significant differences (X2 = 20.683; p = .004) and (X2 = 31.634; p = .000) when comparing the significance values with the theoretical contrast value (p < .05). The IX cycle students exhibited the highest average rank.

Furthermore, the study of social anxiety and sociodemographic variables was conducted, which demonstrated that when comparing social anxiety and its components according to sex, there are no statistically significant differences (U = 21304.000; p = .168). When comparing the significance values with the contrast theoretical value (p > .05), the results were consistent. In the comparison of the same according to age, the results demonstrated statistically significant differences (X2 = 6.094; p = 0.048) when contrasting the significance values with the theoretical contrast value (p < 0.05). Students aged 25 to 30 exhibited the highest average rank. Similarly, the study revealed that statistically significant differences (U = 20779.000; p = .005) were observed when comparing the values of significance with the theoretical contrast value (p < .05). This was evident in the Law degree students, who exhibited higher scores. In the comparison of social anxiety and its components according to the cycle, it was found that there are statistically significant differences (X2 = 19.872; p = .006) when comparing the significance values with the contrast theoretical value (p < .05). The IX cycle students obtained the highest average rank.

Finally, the relationship between state anxiety and trait anxiety with the components of social anxiety is presented in . The analysis revealed a positive and highly significant correlation between the two variables (rho = .220; p < .01), indicating a correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety with social anxiety. Finally, the analysis of the data revealed a positive and highly significant correlation between trait anxiety and social anxiety (rho = .153; p < .01). This indicates that as state anxiety increases, so too does trait anxiety, and vice versa. Consequently, it can be concluded that the greater the state anxiety and the greater the trait anxiety, the greater or stronger the social anxiety and vice versa.

Table 2. Relationship of state anxiety and trait anxiety with the components of social anxiety.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1. Discussion

With regard to the overarching objective of this research, it was determined that there is a positive and highly significant correlation between the three study variables. This correlation indicates a stronger association between state anxiety and social anxiety (rho = .220; p <. 01) than between trait anxiety and social anxiety (rho = .153; p < .01). Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a correlation. Consequently, an increase in state anxiety is accompanied by an increase in social anxiety, and a similar relationship exists between trait anxiety and social anxiety. These results are comparable to those reported by Kuba (Citation2017), who examined a sample of 124 psychology students from a private university in Lima. The study revealed a significant correlation (p < .05) between social anxiety and irrational beliefs. Conversely, Vento (Citation2017) found that there is a significant relationship (p < .05) between trait and state anxiety and coping strategies in a sample of 95 music students at a university in Lima. Thus, a robust, positive, and statistically significant correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety with the components of social anxiety is confirmed in students at a private university in Metropolitan Lima. Additionally, it was determined that state anxiety levels are higher than trait anxiety levels. Furthermore, state anxiety is associated with the behavioral repertoire of students when faced with social situations and stimuli that cause them social anxiety (Barlow & Durand Citation2001).

The research identified that the scores for state anxiety (45.66%) and trait anxiety (54.12%) are located at an intermediate level. Trait anxiety, which presents the highest average (M = 46.73), and state anxiety, which presents the lowest average (M = 46.26), were the two most prevalent forms of anxiety. Similarly, one-third of university students (29.84%) exhibited high levels of state anxiety, while one-quarter of students (25.39%) demonstrated high levels of trait anxiety. These findings align with those reported by Mendiburu et al. (Citation2019) examined a sample of 2017 dental students from a Mexican and an Argentine university. Their findings revealed that 57.5% and 54.8% of these students exhibited pathological anxiety, a percentage that was classified as highly significant. Our findings are also consistent with those of Delgado & Núñez (Citation2019), who examined a sample of 94 university students enrolled in a psychology program at a private university in Metropolitan Lima. The researchers observed an average state anxiety score of 43.71 and an average trait anxiety score of 42.74. This evidence suggests that university behaviors driven by pathological anxiety are associated with variables related to personality, particularly external stimuli and stressful situations. In contrast, these findings diverge from those of Sunday (Citation2016), who examined a sample of 307 university students and found that trait anxiety was relatively low, with a mean of 18.72 and a standard deviation of 8.88.

A comparison of the results of this research with those of other studies conducted in different areas reveals certain similarities and differences. For instance, the study by Silva et al. (Citation2020) examined sleep quality and anxiety in college students in relation to circadian preference. Although the focus of the two studies differs, both share an interest in understanding the mental health of college students. While the present study focuses specifically on anxiety, the study by Silva et al. considers factors such as sleep and circadian rhythms. These investigations can complement each other to provide a more complete understanding of the factors that affect college students’ well-being.

In contrast, the study by Yang et al. (Citation2023) examined the relationship between negative life events, trait anxiety, and depression in Chinese college students, with a particular focus on the moderating effect of self-esteem. Although this study focuses on a different population and different variables, it provides valuable information about the interaction between anxiety, depression, and other psychological factors. By comparing our findings, we could explore whether the observed relationships between state and trait anxiety and social anxiety are consistent across different cultural contexts and student populations.

Furthermore, the study by Kikkawa et al. (Citation2023) examined the effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms, with a particular focus on the mediating effects of trait and state anxiety. Although this study focuses on a different intervention and different mental health outcomes, it provides insight into how anxiety may mediate the relationship between variables such as physical activity and depression. This perspective may be relevant to my study when considering how other factors may influence the relationship between anxiety and social anxiety in college students.

The study by Stinson et al. (Citation2024) examined the mediating effect of state mindfulness on the relationship between brief mindfulness training and sustained engagement with social stress across different levels of social anxiety. Although the focus of the two studies differs, this study provides insight into how mindfulness may influence the way people cope with social stress. This information may be useful in understanding how to intervene with social anxiety in college students. The comparisons highlight the importance of considering a variety of factors and approaches when researching anxiety and mental health in university contexts.

Furthermore, the findings of the study indicate that university students exhibit a moderate level of social anxiety (51%), with similar levels of anxiety across all components. However, in Component D3, which pertains to interactions with the opposite sex, the highest score was observed (M = 16.35), while Component D4, which concerns assertive expression of annoyance, displeasure, and anger, exhibited the lowest score (M = 15.49). This discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that, in the constitution of the sample, women (64.4%) outnumbered men (35.6%). These results exceed those reported by Pego et al. (Citation2018), who evaluated 955 nursing students from a Galician university in Spain and found a prevalence of pathological anxiety in 60% of university students. In contrast, Valera (Citation2021) found that pathological anxiety was present in 35.8% of the students in their sample of 235 university students. Additionally, 60% exhibited mild anxiety, while 3.8% did not.

Conversely, no significant differences in state anxiety and trait anxiety (p > .05) were observed according to sex. However, significant differences (p < .05) were found according to age, major, and study cycle. Students between the ages of 25 and 30, law majors, and IX cycle students exhibited the highest average rank. These results may be explained by the fact that the sample consisted of 259 law students (57.7%) and 190 psychology students (42.3%). These results differ from those found by Domingo, who did find significant differences according to sex (p > .05), with men having higher trait anxiety and women having higher state anxiety.

Conversely, Huillca (Citation2019) observed that male university students exhibited higher levels of pathological anxiety than their female counterparts. Additionally, the study revealed significant differences in state anxiety levels according to university major. These findings underscore the necessity of considering the nuances of each academic program when studying anxiety in college students. One of the samples demonstrated that there were no significant differences in social anxiety (p > .05) according to sex. However, there were significant differences (p < .05) according to age, major, and study cycle, with students between the ages of 25 and 30, law majors, and IX cycle students obtaining the highest rank. The findings of our research are inconsistent with those of Hernandez (Citation2018), who examined a sample of 231 students from the II to the X cycle, with ages ranging from 18 to 29 years. The study found no significant differences between sexes (p > .05). However, significant differences were found regarding the year of study (p < .05). University students in the first four cycles exhibited the highest levels of social anxiety.

The results indicate a highly significant positive correlation between state anxiety and the following variables: D2: interaction with strangers (rho = .207), D3: interaction with the opposite sex (rho = .146), D4: assertive expression of annoyance, displeasure, and anger (rho = .212), and D5: embarrassment or ridicule (rho = .193). Conversely, there is a significant correlation (p < .05) between D1: public speaking and interaction with people of authority and D1: public speaking and interaction with people of authority (rho= .158). In trait anxiety, there is a positive and highly significant correlation (p < .01) with D2: interaction with strangers (rho = .153), D3: interaction with the opposite sex (rho = .129), D4: assertive expression of annoyance, disgust, and anger (rho = .136), and with D5: embarrassment or ridicule (rho = .133). Conversely, no significant relationship was observed between trait anxiety and D1: public speaking and interaction with people of authority (rho= .089).

4.2. Conclusions

It has been demonstrated that there is a positive and highly significant correlation between the three study variables. The strength of association between state anxiety and social anxiety is greater than that between trait anxiety and social anxiety. It is acknowledged that the levels of state anxiety, trait anxiety, and social anxiety are within a moderate range.

Similarly, no significant differences were observed in state anxiety and trait anxiety according to sex. Nevertheless, significant differences were observed according to age, major, and study cycle. Students between the ages of 25 and 30, those in the law major, and those in the IX cycle exhibited the highest average rank. Similarly, there were no significant differences in social anxiety according to sex. However, there are significant differences according to age, major, and study cycle. Students between the ages of 25 and 30, those in the law major, and those in the IX cycle who obtained the highest average rank exhibited the most notable differences.

The investigation concluded that there is a positive and highly significant relationship between state anxiety and the following dimensions: D2: interaction with strangers, D3: interaction with the opposite sex, D4: assertive expression of annoyance, displeasure, and anger, and D5: becoming evident or ridiculous. Conversely, there is a notable correlation between D1 (public speaking and interaction with people in authority) and trait anxiety. With regard to trait anxiety, there is a positive and highly significant correlation with D2: interaction with strangers, D3: interaction with the opposite sex, D4: assertive expression of annoyance, displeasure, and anger, and D5: being exposed or in evidence. A significant relationship was not found between D1: public speaking and interaction with people of authority.

The findings of this study indicate a significant correlation between state, trait, and social anxiety, with a stronger association between state anxiety and social anxiety. This suggests the importance of considering both transient anxiety states and stable personality traits when addressing social anxiety in college students. Furthermore, levels of state and trait anxiety were found to be average, with a significant proportion of students experiencing high levels of anxiety. This highlights the need for interventions to address both acute symptoms and general anxiety tendencies in the student population. Finally, the differences in anxiety levels according to major indicate that the specific characteristics of the academic program may influence the anxiety experience of students. This highlights the importance of developing strategies adapted to the specific needs of each discipline to improve the emotional and academic well-being of university students.

4.3. Recommendations

At the university level, the design and implementation of techniques and/or strategies embedded in coping programs and proposals for social skills training are recommended to enhance students’ ability to manage anxiety, thereby enabling them to effectively navigate the various anxiety-inducing situations that may arise in their academic and professional lives.

It is recommended that the faculties of psychology and law implement a psychotherapeutic evaluation of all entrants, with longitudinal follow-ups and a final evaluation, as an essential requirement to complete the degree. It is recommended that this be carried out in parallel with the elaboration of psychoeducational programs and workshops aimed at students, which include expository practices, assertive behaviors, and cognitive techniques (systematic desensitization, stress inoculation, visualization, modeling, and others). In order to determine the state of anxiety in which future professionals find themselves, it is recommended that various psychological evaluations be conducted in an alternating manner.

Finally, it is recommended that future researchers consider the study carried out as background in order to further analyze the variables of state anxiety, trait anxiety, and other components of social anxiety, such as avoidance behaviors, security, and exhaustion. Consequently, further studies should be conducted using other variables that may be more closely related to those already mentioned, such as entrepreneurial attitude, violence in the couple relationship, procrastination or postponement, and emotional dependence, in students from both public and private universities.

Authors’ contributions

The contributions of the authors to this work are as follows: P.E.M.V., M.R.B., A.G., V.D.C.A.B., and J.V. conceptualized the study; P.E.M.V., M.R.B., and A.G. designed and conducted experiments; V.D.C.A.B. analyzed data. P.E.M.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical review and approved the final version.

Ethical approval

All participants were provided with consents that highlight their voluntary participation, how the data will be used in the research and how their confidentially will be maintained during and after the study.

Consent to participate

Consents were obtained from the participants’ parents to maintain the ethical standards within this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pedro E. Martínez Valera

Pedro E. Martínez Valera holds a PhD in Global Business Administration from URP. He also holds a Master’s degree in Clinical and Health Psychology and a Master’s degree in Public Health. With nearly 30 years of professional experience as an architect, he is currently an academic and researcher at Ricardo Palma University. He is the current director of the Multimedia Communication Group APERTURA.

Mauricio R. Bouroncle

Mauricio R. Bouroncle holds a PhD in Political Science and International Relations from URP. He also holds a Master’s degree in Administrative Law and Public Management. He graduated with honors as a lawyer from the Faculty of Law and Political Science at Ricardo Palma University (URP), where he currently teaches courses in International Law, Labor Legislation, and Fundamentals of Law. He is a researcher and lecturer in Human Rights and Public International Law at the Faculty of Law and Political Science at the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM).

Ada Gallegos

Ada Gallegos is a university lecturer and researcher. She holds a Doctorate in Government and Public Policies as well as a Doctorate in Education. Her specialization in Public Affairs was completed as a Fulbright scholar through the Hubert Humphrey program, certified by then-President of the United States, Barack Obama. As a dedicated researcher, she leads research teams composed of both national and international scholars. On an international level, she serves as the Chair of the Board for the Consortium for Women Leaders in Public Service (CWLPS), headquartered in Washington DC.

Victoria Del Consuelo Aliaga Bravo

Victoria Del Consuelo Aliaga Bravo is an obstetrician by profession, graduated from San Martín de Porres University. Master’s degree in Obstetrics with a specialization in Reproductive Health, a second specialization in Fetal Monitoring with Diagnostic Imaging in Obstetrics, and a Doctorate in Education. Currently a university lecturer at the Faculty of Obstetrics and Nursing at USMP.

Jackeline Valencia

Jackeline Valencia received the title of Visual Artist in 2017 and the degree of master’s in Cultural Management in 2023 from the Barcelona University. She has 3 years of experience as a researcher in cultural management and women’s studies. She works as an international researcher at the Institute of Women’s Studies at the Ricardo Palma University in Lima, Peru. Her main fields of study are cultural management, heritage, conservation and women’s studies.

References

- Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (2001). Trastornos de Ansiedad. In D. H. Barlow & V. M. Durand (Eds.), Psicología Anormal: un enfoque integral (pp. 127–174. Thomson.

- Basantes Moscoso, D. R., del, L., Villavicencio Narvaez, C., & Alvear Ortiz, L. F. (2021). Anxiety and depression in adolescents. Boletâin Redipe, 10(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.36260/rbr.v10i2.1205

- Basantes, A. V., Naranjo, M. E., & Ojeda, V. (2018). “Metodología PACIE en la Educación Virtual,” una experiencia en la Universidad Técnica del Norte. Formación, 11(2), 35–44.

- Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. Basic Books.

- Bermúdez, V. E. (2017). Anxiety, depression, stress and selfesteem in adolescence. Relationship, implications and consequences in private education. Pedagogical Issues, 26, 37–52. https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/Cuestiones-Pedagogicas/article/view/5351

- Botero, C., & Delfino, G. I. (2020). Anxiety and emotional intelligence in university students. Argentine Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 12(1), 193–194. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7447390

- Bottle, C. (2001). Effective psychological treatments for psychothema panic disorder. Psychothema, 13(3), 465–478.

- Caballo, V., & Salazar, B, A. I, B. and C. I. S. O.-A. C. R. Team. (2016). Construct validity and reliability of the «Social Anxiety Questionnaire for Adults» (CASO) in Colombia. Latin American Journal of Psychology, 48(2), 98–107. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/805/80544784003.pdf

- Delgado, N., & Núñez, O. (2019). Anxiety and coping in students of a private university in Metropolitan Lima. Ricardo Palma University.

- García-Fernández, J. M., Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., & Inglés, C. J. (2013). ¿Cómo se relaciona la ansiedad escolar con el rendimiento académico? Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y,” 4(1), 63–76.

- Guevara-Cordero, C. K., Rodas-Vera, N. M., & Varas-Loli, R. P. (2020). Relationship between self-concept and state trait anxiety in Peruvian university students. Journal of Research in Psychology, 22(2), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v22i2.17425

- Hernandez, A. (2018). Social anxiety in students of the Faculty of Psychology of a public university in Metropolitan Lima. Federico Villarreal National University.

- Hernández, R., & Fernández, C. (2014). Research methodology: quantitative, qualitative and mixed routes. McGraw Hill/Interamericana Editores S.A.

- Huillca, G. (2019). Anxiety in university students from a public and private university in Metropolitan Lima. San Martin de Porres University.

- Kikkawa, M., Shimura, A., Nakajima, K., Morishita, C., Honyashiki, M., Tamada, Y., Higashi, S., Ichiki, M., Inoue, T., & Masuya, J. (2023). Mediating Effects of Trait Anxiety and State Anxiety on the Effects of Physical Activity on Depressive Symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075319

- Kuba, C. (2017). Relationship between irrational beliefs and social anxiety in students of the Faculty of Psychology of a private university in Metropolitan Lima. Peruvian University Cayetano Heredia.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress and cognitive processes. Martinez Rock.

- Lopez, D. (2004). New guide for scientific research. Editorial Planeta Mexicana.

- Mendiburu, C., Cárdenas, R., Peñaloza, R., Carrillo, E., & Basulto, L. (2019). Comparative study levels of anxiety and temporomandibular dysfunction in university students from Argentina-Mexico. Mexican Dental Magazine, 23(2), 85–96.

- MINSA. (2014). Carga de Enfermedades en el Perú. Estimación de los años de vida saludables perdidos. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Perú.

- OECD. (2023). Labour force participation rate.

- Otzen, T., & Manterola, C. (2017). Sampling techniques on a study population. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037

- Pego, E., Río, M. D., Fernández, I., & Gutiérrez, E. (2018). Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in university students of the Degree in Nursing in the Autonomous Community of Galicia. ENE Journal of Nursing, 12(2).

- Restrepo, L. A. M., Arévalo, A. E. U., Arévalo, A. U., Restrepo, I. A. M., & Berrio, S. R. (2021). Burnout académico. Impacto de la Suspensión de Actividades Académicas En el Sistema de Educación Pública En, 15(29), 158–175.

- Sánchez, H., & Reyes, C. (2015). Methodology and Designs in Scientific Research. Editorial Business Support.

- Sánchez, J., Alcázar, A. I., & Olivares, J. (2004). Treatment of specific and generalized social phobia in Europe: A meta-analytic study. Publications Service of the University of Murcia, 20(1), 55–68.

- Santos, C. D., & Vallín, L. S. (2018). Anxiety in adolescence. RqR Community Nursing, 6(1), 21–31. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6317303.

- Silva, V. M., Magalhaes, J. E. D. M., & Duarte, L. L. (2020). Quality of sleep and anxiety are related to circadian preference in university students. PloS One, 15(9), e0238514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238514

- Spielberger, C. D. (1972). Anxiety as an emotional state. In C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (pp. 23–49).

- Spielberger, C., & Diaz-Guerrero, R. (2007). STAI anxiety inventory: TraitState, STAI anxiety inventory: TraitState.

- Stinson, D. C., Bistricky, S. L., Brickman, S., Elkins, S. R., Johnston, A. M., & Strait, G. G. (2024). State mindfulness mediates relation between brief mindfulness training and sustained engagement with social stressor across social anxiety levels. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05627-z

- Sunday, M. (2016). Performance anxiety, mindfulness, self-pity, performance and academic satisfaction in music students at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo, UASD. University of Valencia.

- (2018). Superintendencia Nacional Educación Superior Universitaria, “Informe Bianual sobre la realidad universitaria peruana”.

- Valera, P. E. M. (2021). Ansiedad estado y ansiedad rasgo asociada a la ansiedad social en estudiantes de una universidad privada de.

- Vento, R. (2017). Anxiety and coping in students of a music conservatory. http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/bitstream/handle/123456789/9482/Vento_Manihuari_Ansiedad_afrontamiento_estudiantes1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Yang, S., Huang, P., Li, B., Gan, T., Lin, W., & Liu, Y. (2023). The relationship of negative life events, trait-anxiety and depression among Chinese university students: a moderated effect of self-esteem. Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.010