Abstract

Indonesia’s mineral and coal mining sector has significant economic potential to generate tax income for the state. Recently, the mining industry has reached the exploration limit set by governments. However, unlawful mining has been reported in certain areas of Indonesia. Secondary and qualitative informant interviews were conducted for this purpose. This article examines the existing mining legislation and measures adopted by law enforcement to uphold mining protection. This article asserts that current mining legislation fails to sufficiently safeguard against illegal mining activities. Furthermore, the enforcement of laws against illegal mining is divided among various entities. Environmental degradation continues, and the goal of achieving ecological justice remains unfulfilled. Therefore, to attain ecological justice, collaboration among the entities of the criminal justice system, including the police, prosecutors, and related agencies is crucial.

Introduction

Proper utilization of non-renewable mining resources is crucial for future sustainability and environmental preservation. This activity causes environmental damage; however, it also creates job opportunities and has the potential to increase national and regional incomes (Ekananda, Citation2022; Jolo & Gautama, Citation2018). As mining is a pillar of national and regional development, management should consider sustainability principles to minimize biodiversity loss (Tost et al., Citation2018).

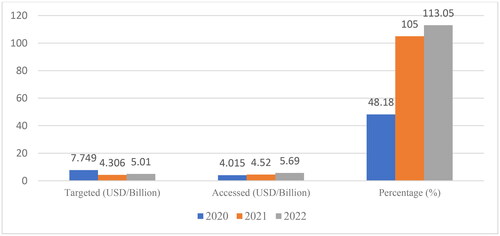

Prospects for national income from the exploration of mineral and coal mining businesses have been continuously increasing over the years, accompanied by investment interest. Investment, as a controller of mineral and coal production, requires a balance between political and economic perspectives (Kesler & Simon, Citation2015). Although mining has an economic impact in the form of taxes for the state, many districts have not developed tax policies or supervision mechanisms to ensure that these amounts are received and provide benefits to communities in mining areas (Spiegel, Citation2012). shows the discernible growth in investment in Indonesia’s mineral and coal mining sector.

Over the past three years, investment in the mineral and coal mining sector has increased significantly. In general, high investment is influenced by legal certainty, which hinders implementation and affects the non-tax state revenue (PNBP). The accumulation of wealth maximization through the growth of mining sector investment led to a capitalist crisis described by Marxist scholars as a crisis of excessive capital accumulation (Baddianaah et al., Citation2022). Economic investment growth in the mining sector is inversely proportional to environmental sustainability, which is often ignored (Auty, Citation2007).

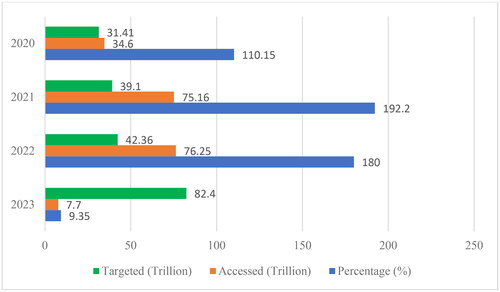

shows that the mineral and coal mining sector contributes significantly to state revenue. From 2020 to 2023, this sector consistently exceeded its target. In 2020, the target was set to 31.41 trillion, with an actual realization to generate 34.6 trillion. The achievement rate exceeded 110.15% expressed as a percentage. In 2021, the government increased its financial target in this sector. The targeted value was 39.1 trillion, and despite the pandemic affecting almost all countries in 2021, there was an increase of 192.2%. By 2022, this sector contributed to 76.25% of the targeted value of 42.36 trillion and the government was able to exceed the target by 180%. Therefore, mining is a commodity that the government requires through tax revenue. Consideration of increasing state revenue is carried out by the government, one of which is through the spirit of changing Law 3/2020, namely providing an extension for existing companies twice in the form of IUPK as a continuation of contract/agreement operations for a period of 10 years (Constitutional Court Decision No. 64/PUU-XVIII/2020).

The mineral and coal mining sector is one of the most promising pillars of national income. However, this sector also poses a problem that requires special attention. Considering that the economic impact of mining activities promises benefits to the community, this activity leads to illegal mining. In the third quarter of 2022, more than 2700 illegal mining locations were classified into 2645 mineral and 96 coal mines (Mineral, Citation2022). Six illegal gold mining sites occur in Bulungan district, north Kalimantan (Zakaria, Citation2022).

Conceptually, illegal mining is an environmental crime that encompasses a wide range of illegal activities that cause damage to nature as a whole or in a specific geographic area (UNODC, Citation2023). However, referring to the mining legislation regime in Indonesia 3/2020, illegal mining is conceptualized as the crime of conducting mining without a license (Article 158) and the crime of conducting production operations in the exploration stage (Article 160, paragraph 2). This type of criminal offense causes economic losses through reduced PNBP for the state and economic losses to the community. Potential state losses due to mining without an illegal mining permit in 2019 amounted to IDR 1.6 trillion and increased to IDR 3.5 trillion throughout 2022 (Indonesia, Citation2023). These losses often cause externality costs that are not reflected by the market but are accepted by the community as a cost due to perceived losses (Furoida & Susilowati, Citation2021).

Illegal mining has become a significant challenge in numerous countries, including Indonesia. Consequently, it is necessary to explore this issue from a distinct perspective. In an analysis conducted by Budi Raharjo, the effectiveness of law enforcement actions was discussed, showing an imbalance in the treatment of law enforcement officers compared with the crimes committed by the community (Raharjo, Citation2018). Several studies, including those by Espin and Perz, have identified the low effectiveness of law enforcement in Peru. This ineffectiveness is attributed to conflicts and a lack of collaboration among institutions in various sectors, with inadequate resource allocation from the central government to lower levels being a contributing factor (Espin & Perz, Citation2021). Moreover, Sadia Mohammed Banchirigah’s study shows that the enforcement process against illegal mining in Ghana, when carried out through violent means, was ineffective because of the inclusion of tribal leaders. However, this enforcement model fails to address the root causes of illegal mining, necessitating government intervention to impose pressure on large mining companies. Bansah et al. (Citation2022) asserted that an informal mining enforcement approach using military strategy does not resolve the problem. However, this leads to casualties and failure to achieve the intended objectives.

The distinctiveness of this study is evident in the result that the procedures governing the enforcement of illegal mining follow a sectoral approach. This affects the legal culture of law enforcement officials in assessing the environmental damage caused by illegal mining. This is due to the lack of inclusion of agencies, such as law enforcement (PPNS) units within the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources and the Environmental Agency. A crucial aspect of achieving ecological justice is consistency between illegal mining enforcement procedures and environmental concerns. This study contributes to the orientation of law enforcement officials when assessing environmental damage as an inseparable aspect of illegal mining. Therefore, the primary objective of combating illegal mining extends beyond holding the perpetrators accountable and realizing environmental justice. This structural framework unfolds into a logical sequence. First, the intricacies in enforcing measures against illegal mining are analyzed. The consequential environmental damage resulting from illegal mining activities is also discussed. Finally, this study highlights the pressing significance of environmental damage as an important factor in preservation efforts and the attainment of ecological justice.

Materials and methods

The primary sources used were Law No. 3/2020 and Law No. 32/2009. To implement these regulations, each law enforcement agency formulated policies, such as the Supreme Court Chief’s Decision 36/KMA/SK/II/2013 and the Prosecutor’s Manual No. 8 of 2022 on Handling Criminal Cases in the Field of Environmental Protection and Management. Court decisions were obtained online from the Directory of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Indonesia. In addition to legal sources, we used documents published by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources in the form of annual reports and press releases.

Data on the phenomenon of increased tax revenue in the mining and coal sectors were collected. The occurrence of illegal mining in Indonesia and law enforcement processes were evaluated. To understand the orientation of law enforcement agencies toward environmental damage caused by illegal mining, legal regulations, court decisions on illegal mining, and perceptions of law enforcement agencies were juxtaposed through in-depth interviews with informants, including investigators, prosecutors, judges, and officials from the Energy and Mineral Resources Agency and the Environment Agency of Kalimantan Utara Province. In-depth interviews were conducted based on the research permits submitted by the researcher.

Approval for the research permit was provided in writing (Bulungan District Attorney Number B-329/0.4.18/Cs.2/03/2023), and verbal approval was provided by the Tanjung Selor District Court, Bulungan City Police Resort (Polresta), Energy and Mineral Resources Agency, and the Environment Agency, Kalimantan Utara Province. This location holds potential for mineral and coal resources, and investigates the phenomenon of illegal gold mining. Therefore, case reviews of court decisions with permanent legal authority and confirmation from law enforcement officials in handling cases are conducted via in-depth interviews. Yet, to evaluate the alignment of law enforcement with environmental values, the author compared it with other court decisions.

The informants who contributed to this research are representatives of the agencies recommended based on the delegation. The informants were willing to provide information related to the research theme. They stated that the results of the interviews could be published in the form of reports or other scientific forms. For this reason, the author declares that the implementation of interviews with informants is carried out procedurally and with the written and verbal consent of each relevant agency. The researchers conducted interviews with six respondents from these institutions, as presented in .

Table 1. Informants and position in the criminal justice system.

Interviews with the informants were conducted over a period of two months, from March to April 2023. This period was used to explore perceptions of each agency. As a government agency, the research procedure was conducted until permission was obtained from the agency head, and interviews were conducted according to the set time and schedule.

The primary source of Law 3/2020 was analyzed based on the interpretation of law enforcement agencies. Interpretation was explored through legal instruments issued by law enforcement agencies and interviews (the legal culture of law enforcement organizations). The ecological justice theory was used as an analytical instrument in this research. This procedure was conducted to explore the orientation of law enforcers in assessing environmental damage as part of illegal mining in the criminal justice system. This analysis aimed to determine the significance of environmental impact as a crucial part of the criminal justice process for future generations.

Results and discussion

Enforcement of illegal mining laws

The law enforcement process spans from the initial investigative stage to the execution phase of court decisions, with each institution maintaining independent authority. The commencement of this stage is closely related to the establishment of law-enforcement agencies. Criminal investigations are conventionally categorized into two primary areas: preliminary and follow-up. However, a third domain also exists, which includes investigations into specific subjects (Palmiotto, Citation2013). The initial investigation is particularly significant within the criminal investigation process, serving as the foundational stage for all legal cases. The primary objectives are the identification of perpetrators, the determination of the sequence of events, the location of potential witnesses, and the collection of physical evidence.

In general, the criminal justice process refers to the Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP). However, considering the characteristics of mining crimes as a type of non-codified criminal act (outside the KUHP), law enforcement must be applied. There is no consensus among experts regarding the concept of special criminal acts (Green, Citation2000). This distinction originates from the continental legal system, namely its special and general parts (Gardner, Citation1998).

Mineral and Coal Mining falls under the classification of administrative criminal offenses (Faure & Svatikova, Citation2012). Law enforcement agencies focus only on the function and existence of mining permits according to Article 35 of Law No. 3/2020. This includes mining business licenses, such as the Mining Business License (IUP), Special Mining Business License (IUPK), IUPK as a continuation of contract/agreement operations, People’s Mining License, Rock Mining Permit, assignment permits, transportation and sales permits, Transportation Service Business License, and Sales IUP.

In the implementation of Article 35, violations are subject to Article 158 of Law No. 3/2020. Article 158 states that ‘any person who engages in mining without a permit as referred to in Article 35 shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of 5 years and a fine of up to IDR 100,000,000,000 (one hundred billion)’.

This focus is intricately linked to the provisions outlined in Articles 35 and 158 of Law No. 3/2020. Perpetrators found to violate these articles can be subject to legal consequences. The investigator adopts a legalistic perspective on the applicability of Law No. 3/2020, presupposing that all regulations are encapsulated within its provisions. Law No. 3/2020 does not explicitly address the environmental damage resulting from illegal mining. Consequently, adverse environmental effects are not duly considered within the ambit of the legislation. To address this problem, it is important to refer to the pertinent clauses in Articles 98–100 of Law No. 32/2009. These clauses indicate that any action that affects the established ambient air, water, seawater, or criteria for environmental damage is subject to punitive measures. Practically, illegal mining practices contribute significantly to environmental degradation. In line with the provisions of Law No. 32/2009, any damage affecting established standards is a criminal offense. Two distinct regulatory frameworks exist for illegal mining, each accompanied by a set of sanctions (Golubev et al., Citation2020).

As the norm of Law No. 3/2020 becomes ambiguous, in the adjudication phase, the police issue criminal mining field instructions, whereas the prosecutor issues Attorney General’s Guidelines No. 8/2022. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court issued Guidelines for Judges No.26/KMA/SK/II/2013. Of these three guidelines, only the Supreme Court requires special competence in the form of environmental judge certification through crime handling training. Investigators and public prosecutors apply normatively without special competence or certification. As the authority issuing decisions on crimes in the environmental field, the Supreme Court provides judges with education and training. The purpose of training and certification is to enhance the professionalism and integrity of judges in handling environmental cases, as part of protecting and fulfilling a sense of justice in society (Subroto, Citation2014).

Considering that the type of crime in the mineral and coal mining sector is not a common offense, as regulated in the KUHP, police investigators should be able to seek assistance from relevant departments. The second alternative is to coordinate with Civil Servant Investigators, known as the PPNS, whose presence, functions, and duties are explicitly regulated in Article 1, paragraph (1) of the KUHAP. Investigators do not coordinate with relevant departments or PPNS investigators even though they play a role in the investigation process (Kusuma & Darmawan, Citation2013).

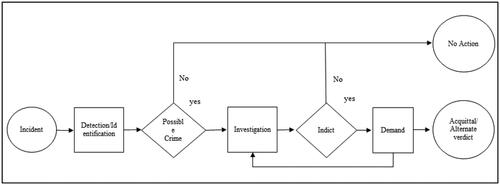

Sectoral ego at the investigative level is due to procedural issues with the Civil Servant Investigators, who fall under the Ministry with full intervention from the Directorate General of Mineral and Coal. Institutionally, the performance can be influenced by the Directorate General. The PPNS is not independent because the results of law enforcement activities should be reported to the Directorate General. However, a series of law enforcement activities constitute an identification process for assessing suspected violations. Although, organizationally, the PPNS has the authority to follow up on reports of mining and mineral criminal acts, its authority is not independent due to the intervention of the Directorate General. Therefore, the system affects the performance of the PPNS under the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. The mechanism of illegal mining investigation by the PPNS is presented in .

Figure 3. Civil Servant Investigator (PPNS) mineral and coal investigation procedures (Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Regulation No. 31/2016).

The weaknesses of the PPNS are attributed to four factors: the structure is divided per Directorate General; competence under the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources is not optimal; lack of budgetary support, inadequate facilities and infrastructure; and lack of solidarity in law enforcement (Wardhani, Citation2022). The concept of procedures is an important foundation of a country dedicated to upholding the rule of law. This serves as the tangible cornerstone of the legal framework, providing substantive assurance for the equitable implementation of the law (Nonet et al., Citation2021). The coordination of the investigative process of PPNS remains under the Inspectorate General, which has the task and function of conducting internal supervision within the Ministry. This has the characteristics of responding to crime complaints from the public, besides building investigations, focusing on violations, and investigating crimes. From the framework, investigations are directed toward uncovering the ‘truth’ with competence and authority, and the main investigative skills lie in finding and interpreting ‘clues’ to determine ‘who did it’ or the perpetrator of the crime (Maguire, Citation2008).

The limited number of PPNS under the Directorate General of Mineral and Coal is one of the determining factors for the sustainability of law enforcement in the mineral and coal mining sector. Moreover, when viewed from its locus, the presence of PPNS for mining and minerals is centralized in Jakarta, even though mining activities are scattered in different regions. According to provincial energy and mineral resource agencies, there is no PPNS, and even local areas are not given authority because the central government determines and monitors the mining areas.

Regarding the performance of PPNS under the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, specifically in mineral and coal mining, integrated efforts between prevention and supervision are required. Repressive efforts are also crucial to prevent tolerance of numerous violations in the mineral and coal mining sector. Considering the essential tasks and functions of PPNS in enforcing criminal acts, there is a need to strengthen the quantity and quality of PPNS personnel, including infrastructure requirements. Institutional and organizational structures should be redesigned to prevent conflicts of interest. Moreover, mining PPNS needs to collaborate as a coordination tool with other agencies to strengthen their performance in realizing environmental values against criminal acts.

Despite the limitations of PPNS Minerba, investigations into environmental damage caused by illegal mining can pave the way for other functional and inter-institutional opportunities. First, from a technical standpoint, mining operations involve inspectors. According to Article 6, paragraph (1) of Permenpan RB Number 30/2022, mine inspectors are authorized to conduct inspections regarding environmental management, reclamation, and post-mining activities. Mining inspectors are authorized to investigate mining cases. Moreover, the central government has delegated regional authority to guide and supervise mineral and coal mining in these regions (Article 2 Perpres 55/2022). One indication of the delegation of authority to mining inspectors is the weakness of Law 3/2020, which transferred the authority of mining inspectors to a central body. Before the availability of Perpres 22/2022, one of its polemics was the budget allocation for conducting supervision.

The second concern was the participation of the Environmental PPNS (Article 94 of Law 32/2009). The rationality behind cross-sectoral involvement, stemming from the impact of illegal mining, primarily revolves around environmental degradation (as illegal mining constitutes a multi-sector offense). Therefore, addressing it necessitates collaboration among relevant agencies, employing a multi-door or a multi-legal regime approach.

The limitations of one legislation can be addressed by supplementing it with others by tracing the primary crime, related offenses, and accompanying criminal acts. Additionally, the environmental PPNS is empowered to oversee the management of damage caused by mining activities, as stipulated in article 8, point 31 of regulation 22/2019 of the Minister State Apparatus Empowerment and Bureaucratic Reforms (Nasir et al., Citation2023). The Environment and Forestry Law Enforcement under Ministry of Environment and Forestry (Gakkum KLHK) is relatively accessible and evenly distributed regionally, including (1) Sumatra, (2) Java, Bali, Nusa Tenggara, (3) Kalimantan, (4) Sulawesi, and (5) Maluku and Papua regulated by the Minister of Environment and Forestry in P.18/MENLHK-II/2015.

The Indonesian Police, as a law enforcement institution, can suppress illegal mining, but only temporarily. The approach used is to maintain security and order by acting as a pressure group on national and local governments to promote social order and achieve justice for communities (Lumowa et al., Citation2022).

Law enforcement on illegal mining is also a dilemma for countries worldwide, and Ghana uses a different approach than Indonesia. The approach of the government to this type of crime is to use the military. This approach fails to address the most fundamental problems, such as poor economic conditions, increased youth unemployment, and illiteracy. The military-style approach, as a strategy to protect natural resources and eliminate ‘threats’, includes special task force operations against small-scale illegal mining. This includes patrolling mining areas; arresting individuals; and confiscating, burning, and destroying mining equipment, leading to increased levels of chaos in some areas of Ghana (Eduful et al., Citation2020). The persuasive approach through military means is ineffective in decreasing the achievement of the objectives. This approach leads to undesirable consequences, such as casualties, injuries, human rights violations, and financial losses incurred by the affected population through damage to equipment used in mining exploration (Bansah et al., Citation2022).

Several reasons why the enforcement of illegal mining in Indonesia has not been oriented toward environmental consequences or damage are due to differences in perceptions among law enforcement agencies (police, civil servant investigators, public prosecutor’s office, and judge).

Police agencies, as investigators, issued field guidelines for handling environmental crimes in the form of Juklap. The police investigator said that investigations into illegal mining cases refer only to the KUHAP. The Implementation Guidelines (Juklap) issued by the Indonesian National Police do not bind investigators. The police investigator added that the competence of investigators is seen in educational qualifications, namely, law graduates. Therefore, for illegal mining cases, the nature is the same as that of other criminal offenses, and the police have not provided training as a follow-up to this procedure. Based on the theory of criminal liability, perpetrators of illegal mining can be held accountable if they fulfill the elements of the criminal offense regulated in the law (Hall, Citation2010). According to the police investigator, the investigation process considers the guilt of the perpetrator and does not consider the consequences of illegal mining.

The context of general criminal offenses is certainly different from that of illegal mining as an environmental crime. The investigator’s orientation does not reflect the urgency of the non-human element to be considered worthy of protection (Garner, Citation2003). Based on the utilitarian principle, ecologies also have the ability to feel pleasure and pain, so humans are obligated to avoid causing pain and suffering despite our assumption that ecologies do not have any rights (Ezra, Citation2017).

Institutionally, the PPNS at the center does not run effectively. This situation is exacerbated by the sectoral ego of Polri investigators who are not involved in the mine inspectors and environmental civil servants. Collaboration between agencies, such as through collaborative learning and collaborative problem solving, is a contemporary tool that must be used by every law enforcement officer (Cropp, Citation2012).

However, this is not the case for public prosecutors. The Attorney General’s Office issued Attorney General Guidelines No. 8/2022. The perception is that the characteristics of illegal mining crimes are still being debated, and there is still debate regarding this concept. Referring to Law No. 3/2020, the basis is the material offense, namely, the permit, not the formal offense in the form of consequences.

According to the public prosecutor, the first fundamental problem related to Law 3/2020 is the negligence in formulating charges for illegal mining perpetrators related to the location or area of mineral and coal mining exploration. This is a crucial determinant of the environmental damage and loss. The second problem relates to the confiscation of evidence, which is a problem for public prosecutors as court decision-makers. Many cases involve the use of mineral and coal mining exploration equipment, making it challenging to seize the assets resulting from mining crimes. Law enforcement agencies capture the potential environmental damage and losses in the mining sector. This understanding is a progressive orientation of the prosecutor’s office that pays attention to living things (non-humans), including land, as victims of illegal mining (White, Citation2013).

Perceptions of the enforcement of illegal mining have led to a need to strengthen law enforcement agencies. This strengthening is consistent with rational institutional goals, with the existence of guidelines or directives issued by each institution (Mohr, Citation2006). The success of an organization, including law enforcement agencies, is determined by four factors: First, an organization’s official functions are bound by rules. Second, a specific scope of competence, which is a range of duties in the division of labor, should be performed by someone equipped with the necessary means and authority. Third, an office organization should follow the principle of hierarchy. Fourth, a set of rules and technical norms are expected to govern the implementation of office tasks (Soderstrom & Weber, Citation2020).

The elements of environmental damage and loss can be used as a basis for the prosecution and punishment of illegal mining perpetrators when law enforcement structures have the same understanding at the investigative level. At the investigative level, the police have authority over the types of criminal offenses expanded for criminalization and give prosecutors the freedom to threaten and file charges in the judicial process (Dubber, Citation2005). Therefore, differing understandings of law enforcement can lead to weak integrity. This weakness is due to insufficient resource allocation for law enforcement actions and limited collaboration between state law enforcement agencies (Espin & Perz, Citation2021). During adjudication, alternative charges, such as ideal courses can be applied (Faisal & Rustamaji, Citation2020).

Environmental damage as the impact of illegal mining

The negative impacts of illegal mining include economic and environmental losses for the country and for future generations. These negative impacts can be classified into three categories: economic (a reduction in state revenue through the tax sector), environmental (decreased soil quality, environmental pollution, and reduced wildlife habitat populations), and social (health).

Illegal mining significantly hinders development owing to the loss of state revenue, land degradation through toxic contamination and pollution caused by mud and sediments, air and noise pollution, and the destruction of biodiversity, including natural flora, fauna, and aquatic species. These negative effects are also experienced by humans and include respiratory and skin diseases, hearing loss due to noise, physical and psychological stress, and malaria. The negative impacts can be mapped to social, economic, and environmental groups. Social impacts can hinder regional development by not adhering to spatial and regional planning, triggering social conflicts in society, causing vulnerable conditions and security disturbances, damaging public facilities, and causing community diseases and health disruptions due to chemical exposure.

Mining can affect human capital accumulation through various channels. Although criminal investigations into illegal mining are positive and economically substantial, their impact is consistently insignificant (Mejia, Citation2020). Economic impacts can reduce PNBP. These trigger economic disparities within the community, cause fuel shortages, and lead to an increase in the price of essential goods for the public. The environmental impacts include damage to the environment, destruction of forests when located within areas, potential environmental disasters, disruption of the productivity of agricultural and plantation land, and river turbidity and water pollution (Mineral, Citation2022). Illegal mining can lead to environmental damage, such as deforestation, landslides, and water and soil pollution (Nugroho, Citation2020). It also causes mercury poisoning in humans and animals. Illegal mining can decrease the quality of surface water and sediments. Negative impacts have also occurred in other countries, such as Ghana (Darko et al., Citation2021). This study demonstrates that the negative impacts of illegal mining vary depending on the location and type of minerals mined.

Illegal mining in Indonesia and other countries will continue to proliferate without reconstructing regulations. Some factors causing this crime to persist include the ease of engaging in small-scale mining compared with fulfilling administrative obligations. This factor is prevalent in almost all regions of Indonesia (Meutia et al., Citation2022), including regulatory factors, unclear boundaries of artisanal mining, and economic factors.

Indonesia’s legislative politics perpetuate a system of uneven economic accumulation and centralized political decision-making that is ineffective against environmental protection. These policies prevent the development of systems that enable formal legitimization and regulation of small-scale miners’ livelihoods (Spiegel, Citation2012). The absence of viable alternative sources of livelihood capable of ensuring sufficient income poses a formidable challenge to the government in its efforts to regulate illegal mining (Bansah et al., Citation2022). The crime continues to be committed when it is not accompanied by regulatory reorientation or community empowerment. The need for insight and work preparation for economically weak communities, specifically the understanding of the environment as a livelihood for future generations, will continue to occur in society (Aldyan, Citation2022).

Disregarding environmental damage due to illegal mining in the criminal justice system can be observed in several court decisions. Court decisions do not assess environmental damage.

From the cases in , the search results show that the judge’s consideration of environmental urgency from a normative perspective is (1) not supportive of the government in eradicating illegal mining activities, (2) that large-scale mining can have significant adverse effects, and (3) that there is a potential loss of state revenue.

Table 2. Comparison of the judges’ decisions related to unlicensed mining crimes.

The following cases are presented to distinguish between different perceptions of law enforcement when assessing environmental damage caused by illegal mining. First, Tanjung Selor District Court Decision Number 147/Pid.Sus/2022/PN Tjs and Tanjung Selor District Court Decision Number 148/Pid.Sus/2022/PN Tjs. Gold mining cases typically occur in mining areas. The exploration and extraction of mining results using Cyanide (CN), which according to Article 5, paragraph (2) letter f of PP 22/2021, is considered a toxic substance and is included in the quality standard criteria for environmental damage. Additionally, in the decision of the Koba District Court of Bangka Regency Number: 81/Pid.B-LH/2020/PN Kba, which is a mineral and coal mine that occurred in a protected forest. The perpetrator’s modus operandi involved conducting a land dredging business openly in a protected forest area, resulting in (1) Dredging and soil extraction pit with depths varying between 2 and 7 m; (2) Loss of topsoil and subsoil; and (3) Loss of natural vegetation.

The factors considered focus on the potential criminality of illegal mining but do not discuss the causes and exploration of potential environmental damage. This situation becomes problematic because of the limitations of the charges presented by investigators and prosecutors who do not include other institutions or bring in experts to assess environmental damage and losses. However, this process is crucial and urgent, including for the environmental agency through economic valuation (Alier, Citation2001). During the investigative process, consideration should be given to the integration of environmental damage. It is important to assess whether the alleged perpetrator can be charged exclusively under Law 3/2020 or if there are additional criminal elements associated with environmental offenses. The outcome of the damage incorporated into the indictment reflects ecological justice, even though recognition is confined to procedural aspects.

This situation has been exacerbated by the social construction of profit-oriented illegal mining. Social construction becomes problematic when the orientation toward profits from illegal mining leaves behind environmental damage (Agustina et al., Citation2021). Therefore, a normative and technical understanding is needed to minimize environmental damage, and the political ecology perspective can be applied to enforcement. This approach connects the definitions of informal and illegal mining by considering changes in and reassessing the level of environmental damage (Benites, Citation2023).

Urgency of environmental damage as a factor that should be considered in the criminal justice system to achieve ecological justice

The direct impact of illegal mining is soil degradation, which disrupts the ecosystem around the mining area because illegal mining exploration tends to neglect miner safety and environmental concerns. This violates and contradicts environmental ethics. Therefore, a shift from anthropocentrism to ecocentrism is important, and this transformation should extend beyond the government to include law enforcement agencies and other segments of society, including miners.

Ecocentrism has two relational aspects, namely environmental distributive justice between society and humans. This concept is understood as human and ecological justice, as both are aspects of the same relationship (Stevis, Citation2000). Moreover, mining exploration, on either a large or small scale, tends to include extraction materials, making resistance a necessary alternative to ecological deviation in advancing social and environmental justice. The five illusions supporting and reinforcing unequal ecological exchanges include (1) The fragmentation of scientific perspectives into limited categories, such as ‘technology’, ‘economy’, and ‘ecology’. (2) The assumption that market prices work is equivalent to reciprocity. (3) The illusion of machine fetishism means that the technological capacity of a population is not dependent on its position in a global resource flow system. (4) Representation of inequality in the social space as a stage of development over historical time. (5) The belief that ‘sustainable development’ can be achieved through consensus (Bedford et al., Citation2020).

One determinant of successful criminal law enforcement is the role of judges. The judiciary controls the rights of criminals and victims (Roach, 1999). The entity of ecological existence has been embodied in Law 39/2009. However, in the context of illegal mining, not only the licensing sector but also the damage to nature and ecosystems as a result of illegal mining deserves attention. The criminal justice system can realize ecological justice through area-based illegal mining investigations (Rohman et al., Citation2024).

Law 3/2020, the criminal administration, has not yet regulated the enforcement mechanism for illegal mining. This becomes a multiple interpretation by law enforcement officials. For this reason, each law enforcement agency provides different interpretations, and only the Supreme Court is progressive in imposing training and certification on judges (Saleh & Spaltani, Citation2021).

In 2011, the Supreme Court implemented Law 32/2009 to train and certify environmental judges. This policy has implications for judges who are authorized to hear environmental cases, including violations of criminal provisions in the mining sector, as stipulated in Articles 1 and 5, paragraph (3), letter b of the Supreme Court Decree 134/KMA/SK/IX/2011:

Paragraph 1 Environmental cases must be tried by environmental judges;

Paragraph 2 Environmental cases as referred to in paragraph 1 include violations of civil and criminal provisions in the field of environmental management protection, including but not limited to regulations in the fields of forestry, plantations, mining, coastal and marine, spatial planning, water resources, energy, industry, and or conservation of natural resources.

This institution issued guidelines earlier than the police and public prosecutor’s office. The guidelines are the Decision of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court No.26/KMA/SK/II/2013. However, the challenge is the limited use of these guidelines by judges in deciding on illegal mining cases.

The uneven distribution of environmentally certified judges in certain regions is problematic. Thus, the court is faced with illegal mining cases, but the availability of judges is inadequate. Therefore, the Supreme Court’s policy remains normative. In certain areas, illegal mining cases are tried by uncertified judges. The judge stated that there are two problems related to the enforcement mechanism of illegal mining. Second, judges are limited by indictments and charges filed by prosecutors. Therefore, judges’ decisions often mention aggravating reasons, such as ‘potential environmental damage’ as illustrated in . The potential damage in these court decisions, judges have been oriented toward the existence of the environment, but only normatively. The judges do not elaborate on the actions, equipment, and environmental impacts. Thus, non-humans, such as victims of illegal mining, are not the main parameters for criminal punishment.

Environmental orientation must be applied to every law enforcement agency as a guide for the environmental criminal justice process, including illegal mining. The treatment of land, nature, and ecology maintains the balance of illegal mining enforcement and achieves ecological justice (Leopold, Citation2003). Illegal mining entities damage the ecological integrity (Pope et al., Citation2021). Based on the natural order, the criminal justice process should use an ecocentrism approach.

Ecocentrism asserts that humans are just one part of a wider community and that the well-being of each member of the community depends on the well-being of the universe. For this reason, nature must be seen as a part that has certain intrinsic values. These rights should be applicable to all species and ecosystems worldwide. According to moral ethics, the environment has the right to be protected (White, Citation2018).

According to the principle of utilitarianism, this is morally justified (Veenhoven, Citation2010). However, the process should be accompanied by consistent environmental preservation because non-human entities also have the right to reproduce. Understanding environmental justice is crucial for preserving sustainability in all sectors. Law enforcement authorities in the criminal justice system should collectively understand sustainable paradigms and orientations related to integration principles, sustainable utilization, and intra- and inter-generational justice. Environmental impact is crucial to achieving inter-generational justice. Therefore, the principle should be firmly held and used as a guide for handling large- and small-scale illegal mining crimes to protect future generations (Rustamaji, Citation2017).

Understanding inter-generational justice must be elevated to constitutional rights through these two standards. First, the commutative standard maintains a balance between the benefits and the availability of nature. The concept of reciprocity serves as an indirect right that future generations can inherit. Second, the aggregative standard focuses on the availability of natural resources, which can be measured proportionally (Campos, Citation2018).

Conclusion

This study was conducted to demonstrate the differences in perspectives on the impact of illegal mining among law enforcement agencies. This was due to the lack of clarity in recognizing environmental damage as a consequence of the act in Law 3/2020, despite the regulation of actions in Law 32/2009. The lack of synchronization in regulations led each agency to interpret and implement technical guidelines. The Supreme Court issued guidelines reinforced by human resources (judges). The prosecutorial authority held jurisdiction over matters of insight with the limitation that the concept did not extend to certification. However, the situation was more severe in the police force, where the situations were not mandatory for their members, even though guidelines (Juklap) were issued. There was disorientation among law enforcers toward the non-human rights that should be protected. This resulted in illegal mining enforcement, which led to the neglect of ecological justice.

Based on the aforementioned results, this study proposes several recommendations: First, the synchronization of Law 3/2020 and Law 32/2009, with the establishment of implementing regulations, such as the formation of technical and executable government regulations. The second is the environmental education, training, and certification of law enforcement officers. This strategy minimizes the differing interpretations among law enforcement institutions. The third is the community’s understanding of environmental impacts and the existence of non-human entities. This changes the public perspective on the concept of mining, focusing on profit and environmental preservation. In addition, it respects non-human entities and even considers ecological sustainability as part of the lives of living things.

This study was limited by the location and number of informants. These limitations arose from the number of informants appointed by the leaders of each institution. However, the references for handling illegal mining enforcement included Law 3/2020 and some technical regulations. Each law enforcement entity had a different perception depending on its capacity and competence. For instance, only a limited number of judges, prosecutors, and investigators possessed environmental training certifications, and the same applied to prosecutors and investigators.

Authors contributions

The contributors to this article consist of three authors. First, Arif Rohman contributed to the substantial design, especially in the aspects of data acquisition, interviews with informants, and analysis or interpretation of data. Secondly, Hartiwiningsih Hartiwiningsih reviewed the aspects of the legislation. Third, Muhammad Rustamaji concentrated on the aspect of the value of ecological justice for illegal mining in the criminal justice system. The authors have agreed on the accuracy of the data in their respective tasks. Finally, editing and all forms of improvement to the entire article were carried out by Arif Rohman.

Ethical approval

All precautions related to scientific ethics have been taken into account from the conception to the writing of this paper, as well as the submission to the said journal.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all those who have helped so that this article can be completed. First, to our colleagues who have been willing to review the manuscript of this article. Second, to all the authors of books and journals. From these scientific works, the author gained a lot of inspiration and understanding both conceptually and theoretically. Third, to the informants who provided a lot of information so that we can use the interview results as one of the research data sources to find out the existence of enforcement against illegal mining. Last but not least, thanks to the Centre for Education Financing Services, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, and Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Agency of the Ministry of Finance of Indonesia for supporting this research and publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, AR. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arif Rohman

Arif Rohman is a Doctoral candidate at Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, and works as an assistant professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Borneo Tarakan, Kalimantan Utara, Indonesia. His interests and study are on criminal law, national and international human rights crimes, and environmental crime.

Hartiwiningsih

Hartiwiningsih is a professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia. Her works focus on Environmental Crimes, which are published in the form of books, and national and international journals. She is active as a speaker at seminars on the theme of environmental law, both held by the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law (ICEL). Hartiwiningsih is the Head of the Doctoral Programme at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret.

Muhammad Rustamaji

Muhammad Rustamaji is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia. His interests and study are on Criminal Procedure and criminal justice. As an academic, Rustamaji has authored works in the form of books and reputable journals.

References

- Agustina, P. P., Herdiansyah, H., & Harahap, A. A. (2021). Illegal artisanal and small-scale mining practices: re-thinking the 2nd International Conference Earth Science and Energy. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 819, 1. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/819/1/012032

- Aldyan, A. (2022). The influence of legal culture in society to increase the effectiveness of the law to create legal benefit. International Journal of Multi Cultural and Multi Religious Understanding, 9(11), 322–15. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v9i11.4208

- Alier, J. M. (2001). Mining conflicts, environmental justice, and valuation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 86(1–3), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(01)00252-7

- Auty, R. M. (2007). Natural resources, capital accumulation and the resource curse. Ecological Economics, 61(4), 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.09.006

- Baddianaah, I., Baatuuwie, B. N., & Adongo, R. (2022). The outbreak of artisanal and small-small gold mining (galamsey) operations in Ghana: Institutions, politics, winners, and losers. Journal of Degraded and Mining Lands Management, 9(3), 3487–3498. https://doi.org/10.15243/jdmlm.2022.093.3487

- Bansah, K. J., Acquah, P. J., & Assan, E. (2022). Guns and fires: The use of military force to eradicate informal mining. The Extractive Industries and Society, 11, 101139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101139

- Bedford, L., McGillivray, L., & Walters, R. (2020). Ecologically unequal exchange, transnational mining, and resistance: A political ecology contribution to green criminology. Critical Criminology, 28(3), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-019-09464-6

- Benites, G. V. (2023). Natures of concern: The criminalization of artisanal and small-scale mining in Colombia and Peru. The Extractive Industries and Society, 13, 101105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101105

- Campos, A. S. (2018). Intergenerational justice today. Philosophy Compass, 13(3), e12477. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12477

- Cropp, D. (2012). The theory and practice of collaborations in law enforcement. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 14(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2012.14.3.284

- Darko, H. F., Karikari, A. Y., Duah, A. A., Akurugu, B. A., Mante, V., & Teye, F. O. (2021). Effect of small-scale illegal mining on surface water and sediment quality in Ghana. International Journal of River Basin Management, 21(3), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2021.2002345

- Dubber, M. D. (2005). The possession paradigm: The special part and the police power model of the criminal process. In R. Duff & S. Green (Eds.), Defining crimes: Essays on the special part of the criminal law. Oxford University Press.

- Eduful, M., Alsharif, K., Eduful, A., Acheampong, M., Eduful, J., & Mazumder, L. (2020). The illegal artisanal and small-scale mining (galamsey) ‘menace’ in Ghana: Is military-style approach the answer? Resources Policy, 68, 101732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101732

- Ekananda, M. (2022). Role of macroeconomic determinants on the natural resource commodity prices: Indonesia futures volatility. Resources Policy, 78, 102815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102815

- Espin, J., & Perz, S. (2021). Environmental crimes in extractive activities: Explanations for low enforcement effectiveness in the case of illegal gold mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(1), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.12.009

- Ezra, O. (2017). The rights of non-humans: From animals to silent nature. The Law & Ethics of Human Rights, 11(2), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1515/lehr-2017-0010

- Faisal, & Rustamaji M. (2020). Hukum Pidana Umum (R. A. Agustian, Ed.) Thafa Media.

- Faure, M. G., & Svatikova, K. (2012). Criminal or administrative law to protect the environment? Evidence from Western Europe. Journal of Environmental Law, 24(2), 253–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqs005

- Furoida, A., & Susilowati, I. (2021). The negative externality of mining activities in brown canyon. Economics Development Analysis Journal, 10(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.15294/edaj.v10i4.47256

- Gardner, J. (1998). On the general part of the criminal law. In A. Duff (Ed.), Philosophy and the criminal law: Principle and critique. Cambridge University Press.

- Garner, R. (2003). Animals, politics and justice: Rawlsian liberalism and the plight of non-humans. Environmental Politics, 12(2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010412331308164

- Golubev, S. I., Gracheva, J. V., Malikov, S. V., & Chuchaev, A. I. (2020). Environmental crimes: Law enforcement issues. Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences, 18(5), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.22124/CJES.2020.4483

- Green, S. P. (2000). Prototype theory and the classification of offenses in a revised model penal code: A general approach to the special part. Buffalo Criminal Law Review, 4(1), 301–339. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2000.4.1.301

- Hall, J. (2010). General principles of criminal law. Bobbs-Merrill.

- Indonesia, C. (2023, March 22). ESDM Sebut Kerugian Negara Akibat Tambang Ilegal Tembus Rp.3,5 T. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20230321141404-85-927824/esdm-sebut-kerugian-negara-akibat-tambang-ilegal-tembus-rp35-t

- Jolo, A. Y., & Gautama, R. S. (2018). Pengelolaan dan Pemanfaatan Sumber Daya Mineral Berwawasan Lingkungan (Studi Kasus Kabupaten Halmahera Utara). Techno: Jurnal Penelitian, 7(01), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.33387/tk.v7i01.355

- Kesler, S. E., & Simon, A. F. (2015). Mineral resources, economics and the environment. Cambridge University Press.

- Kusuma, M. A., & Darmawan, N. K. (2013). Kedudukan Penyidik Pegawai Negeri Sipil (PPNS) Dalam Sistem Peradilan Pidana. Kerta Wicara, 3(1), 3. Retrieved from https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/kerthawicara/article/view/4675

- Leopold, A. (2003). From a sand county Almanac. In R. S. Gottlieb & R. S. Gottlieb (Eds.), This sacred earth. Routledge.

- Lumowa, R., Utomo, S. W., Soesilo, T. E. B., & Hariyadi, H. (2022). Promote social order to achieve social and ecological justice for communities to prevent illegal artisanal small-scale gold mining. Sustainability, 14(15), 9530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159530

- Maguire, M. (2008). Criminal investigation and crime control. In T. Newburn (Ed.), Handbook of policing. Willan Publishing.

- Mejia, L. B. (2020). Mining and human capital accumulation: Evidence from the Colombian gold rush. Journal of Development Economics, 145, 102471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102471

- Meutia, A. A., Lumowa, R., & Sakakibara, M. (2022). Indonesian artisanal and small-scale gold mining–A narrative literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19

- Mineral, K. E. (2022). Retrieved June 8, 2023, from https://www.esdm.go.id/id/media-center/arsip-berita/pertambangan-tanpa-izin-perlu-menjadi-perhatian-bersama

- Mohr, L. B. (2006). Organizations, decisions, and courts. In A. Kupchik (Ed.), Criminal court. Routledge.

- Nasir, M., Bakker, L., & Meijl, T. v (2023). Environmental management of coal mining areas in Indonesia: The complexity of supervision. Society & Natural Resources, 36(5), 534–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2180818

- Nonet, P., Selznick, P., & Kagan, R. A. (2021). Law and society in transition. Routledge.

- Nugroho, H. (2020). Pandemi Covid-19: Tinjau Ulang Kebijakan Mengenai PETI (Pertambangan Tanpa Izin) di Indonesia. Jurnal Perencanaan Pembangunan: The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning, 4(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.36574/jpp.v4i2.112

- Palmiotto, M. J. (2013). Criminal investigation (4th ed.). CRC Press.

- Pope, K.,Bonatti, M., &Sieber, S. (2021). The what, who and how of socio-ecological justice: Tailoring a new justice model for earth system law. Earth System Governance, 10, 100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2021.100124

- Raharjo, B. (2018). Effectiveness of law enforcement on mining crime without permission. Jurnal Daulat Hukum, 1(2), 531–536. https://doi.org/10.30659/jdh.v1i2.3327

- Rohman, A., Hartiwiningsih, H., & Rustamaji, M. (2024). Improving ecological justice orientation through a typological approach to illegal mining in the criminal justice system. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2299083. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2299083

- Rustamaji, M. (2017). Pilar-Pilar Hukum Progresif: Menyelami Pemikiran Satjipto Raharjo. Thafa Media.

- Saleh, I. N. S., & Spaltani, B. G. (2021). Environmental judge certification in an effort to realize the green legislation concept in Indonesia. Law and Justice, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.23917/laj.v6i1.13695

- Soderstrom, S. B., & Weber, K. (2020). Organizational structure from interaction: Evidence from corporate sustainability efforts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(1), 226–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219836670

- Spiegel, S. J. (2012). Governance institutions, resource rights regimes, and the informal mining sector: Regulatory complexities in Indonesia. World Development, 40(1), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.015

- Stevis, D. (2000). Whose ecological justice? Journal of Theory, Culture & Politics, 13(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402130050007520

- Subroto, A. (2014). Materi Ajar Pendidikan dan Pelatihan Sertifikasi Hukum Lingkungan Hidup. ICEL dan Pusat Pendidikan dan Pelatihan Teknis Peradilan Mahkamah Agung Republik Indonesia.

- Tost, M., Hitch, M., Chandurkar, V., Moser, P., & Feiel, S. (2018). The state of environmental sustainability considerations in mining. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 969–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.051

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2023). Responding to illegal mining and trafficking in metals and minerals a guide to good legislative practices.

- Veenhoven, R. (2010). Greater happiness for a greater number. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(5), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9204-z

- Wardhani, S. (2022). Desain Organisasi Penyidik Pegawai Negeri Sipil Kementerian ESDM. Auroga Nusantara.

- White, R. (2013). Environmental harm: An eco-justice perspective. Policy Press.

- White, R. (2018). Ecocentrism and criminal justice. Theoretical Criminology, 22(3), 342–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618787178

- Zakaria, I. I. (2022, July 20). Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://www.prokal.co/kalimantan-utara/1773983864/pengungkapan-tambang-emas-ilegal-di-kaltara-10-tersangka-punya-peran-berbedabeda