?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

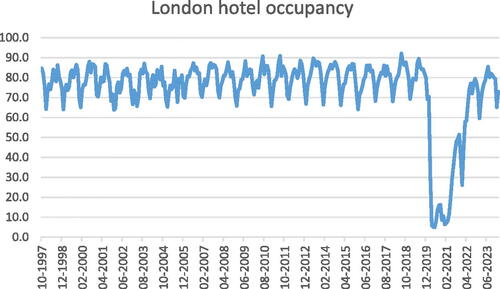

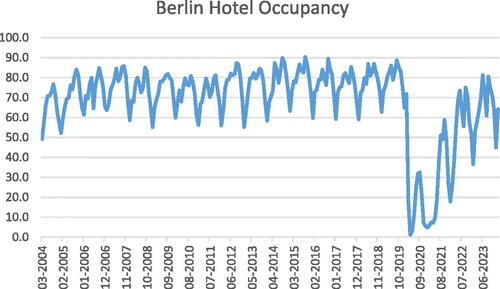

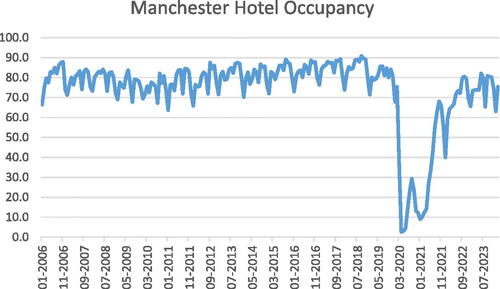

This article deals with the analysis of persistence in tourism in three European cities, namely, London, Manchester and Berlin. We consider hotel occupancy rate data with data beginning at October 1997 (in London), at March 2004 (in Berlin), while those in Manchester start at January 2006. All data ends at February 2024. Fractional integration methods are used, and the results indicate changes in the persistence pattern of the series due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, before the pandemic, the results indicate that the integration order was less than 1 in the three series, implying transitory shocks. However, with the inclusion of data from 2020 to February 2024, the order of integration substantially increases in all cases, and the unit root hypothesis cannot be rejected, implying the permanent effects of shocks. Our results show that the effect of Covid-19 has been especially significant in hotel occupancy rate data in the three cities analyzed, indicating that strong policy measures are needed to reassume pre-crisis trends in the tourism industry.

Subjects:

1. Introduction

Tourism is a very complex phenomenon that affects economy and society in several ways, and, depending on the nature of the impact, it can be analyzed from different viewpoints. Recently, there have been important phenomena that have directly affected tourism. In 2020, the outbreak of Covid 19 affected the sector severely, becoming a key factor and its analysis is fundamental to gain an understanding of the future evolution of tourism. On 1st of January 2021, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, which governs trade relations between the EU and the United Kingdom, came into force after the UK formally left the European Union, which may also have affected the tourism sector, particularly in the departing country.

In big cities, tourism has a significant economic impact. In recent times this sector has changed a lot, affecting new issues that need to be considered from different perspectives. As Paskaleva-Shapira (Citation2007) argue, urban tourism is a specific area of tourism that has grown mostly in recent years. This growth has particularly affected large cities, that face the challenge of taking advantage of the tourist possibilities that urban areas offer, without suffering adverse effects that affect their environment, their economy or their social or cultural peculiarities.

International institutions, such as the United Nations (UN) or the European Commission (EC), have recently been promoting discussion forums in which they endeavor to propose practices that help develop urban tourism by making it competitive and sustainable, bearing in mind that urban tourism is affected by multiple factors of a very diverse nature. The First Global Forum on City Tourism, that took place in Turkey in 2005, focused the debate around these two aspects. There is currently a consensus on the idea that, to achieve these objectives, it is essential to have an effective local government that integrates the interests of tourism with those of the city.

In this article we work particularly with urban tourism. To this end, we examine the hotel occupancy rates in three European cities, namely London, Berlin and Manchester. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), hotel occupancy rate is a benchmark indicator to analyze the evolution of the tourism sector, and there is a correlation between hotel occupancy and the number of tourist arrivals. We study their statistical properties before the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit, and then using data until February 2024, in order to analyze the impact that both phenomena, Covid-19 and Brexit, have had on the sector.

The objective of this research is to determine if the Covid-19 pandemic has altered the general evolution of the sector and has changed trends that were consolidated. At the same time, the research shows, through the comparison of English and German cities, whether the immediate effect of Brexit has also modified that evolution. Therefore, the goal of the study, is to determine the persistence of the shocks and detect if they are going to have transitory or permanent effects in the evolution of the hotel occupancy rate of the three mentioned cities. Determining the persistence of shocks in the evolution of the hotel occupancy rate will be of vital importance to design future strategies in the tourism sector after the uncertainties caused by Covid 19. For this purpose, we use fractional integration methods, which seems to be an appropriate technique in the sense that it allows the effects of the shocks to be examined in a more flexible way than the standard methods based on stationarity or unit root tests and that simply use integer degrees of differentiation (0 for stationarity and 1 for non-stationarity). By allowing the differencing parameter to be a real value, and thus, potentially fractional, we can model the series in terms of nonstationary mean reverting processes, with shocks being transitory though with long lasting effects if the differencing parameter is within the interval [0.5, 1).

The structure of the article is as follows: Section 2 contains the contextual setting. Section 3 is devoted to a short review of the literature on fractional integration in tourism-related series. Section 4 presents the methodology; Section 5 is devoted to the data set. Section 6 displays the main empirical results, while Section 7 contains the discussion and some concluding comments.

2. Contextual setting

As mentioned in the introduction, the relevance of the sector, the magnitude of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the uncertainties that Brexit might generate, call for particular attention. Consequently, academic studies that try to show the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on the future evolution of the sector, and specifically those related to urban centers, have proliferated in the last couple of years.Footnote1

In both England and Germany tourism is an economically significant sector. StatistaFootnote2 reports that in 2022, the travel and tourism industry contributed a total of £237 billion to the United Kingdom’s GDP. This marked a significant increase from £93.8 billion in 2020, but it was still 4.6% lower than the levels seen in 2019. The situation in GermanyFootnote3 is relatively similar, although it must be noted that in Germany the recovery of the sector in 2021 was slower than in the UK, accounting for just a five percent increase on the 2020 level. Overall, the sector generated, directly and indirectly, 338.7 billion euros in 2022, approximately 9.5% below the levels of 2019.

Experience shows that tourism is a very sensitive sector which is affected strongly by global crises; a thorough knowledge of their consequences is essential to design specific measures that can minimize their effect and therefore reduce the risks entailed for the economic growth of a country. In this sense, recent studies point to both travel insurance (Uğur & Akbıyık, Citation2020) and the design of an effective system of local tourism organization (Paskaleva-Shapira, Citation2007) as possible ways to reduce the fragility of the sector.

The three cities that we selected for our study are urban destinations. Inside this category, London and Berlin could be considered world tourism cities according to Sassen’s (Citation2012) definition, which means that these cities have an important position in the world economy since they are the location of leading industries as well as being the focus of production and innovation. Also, we can say that these two relevant cities, capitals of two of the most important European countries, are leaders in the reception of tourists. According to Statista, London was the European city that received the most tourists in 2021, reaching the figure of 20.72 million tourists, while Berlin, in ninth place, received 5.77 million.Footnote4 There is consensus that to successfully develop urban tourism, it is necessary to develop effective local management, which, however, as Maxim (Citation2019) observes, does not seem to be happening in London, where tourism objectives are not reflected in the specific policies of the boroughs.

In the present study we have also included Manchester, a city with different characteristics about urban tourism. Manchester cannot be considered a world tourism city as described by Sassen (Citation2012). Its volume of visitors is much smaller, according to Statista in 2022 Manchester received around 1.2 million international visits.Footnote5 However, since the end of the 80s, Manchester municipal authorities have made important efforts to provide a new economic foundation for the city, transforming it into an international tourist destination. This transformation has followed the model of other English cities that have sought to encourage the creation of financial services and business consulting, leisure, tourism, entertainment and even retail trade (Köhler, Citation2013). We have included this city in order to better understand the effect of Brexit. London and Berlin are cities that can be comparable in terms of tourism. Tourism in Manchester has its own peculiarities, and its evolution can help us to strengthen the conclusions. The following section contains a short review of the literature on tourism on urban cities.

3. Literature review

Cities have always been important tourist destinations (Barrera-Fernández et al., Citation2016; Lerario & di Turi, Citation2018; Postma et al., Citation2017). Hence the prominence of the concept of urban tourism which has strongly impacted on the development of cities. Within the tourism literature, there are many works about the definitions, theoretical foundations, and implications of urban tourism. Ashworth (Citation1989) is considered the first author to analyze urban tourism, affirming that the cities were the main destination and origin of tourism. Urban tourism is the fastest growing type of tourism and one of the most important in terms of volume and economic impact. However, most of the studies about tourism focus on rural tourism and there are not many studies about urban tourism. Before the 1980s, research on urban tourism was not recognized as a distinct field (Edwards et al., Citation2008), but the attention of urban tourism increased in the 1990s. Many cities began to implement programs to develop the urban tourism and the volume of written literature has been growing ever since. For example, Teo and Huang (Citation1995) analyzed urban tourism in Singapore and concluded that the impact of colonial buildings on urban tourism in Singapore is greater than the modern buildings; Berg, Borg and Meer (Citation1995) compared the contribution of urban tourism to the revitalization of some European cities (Antwerp, Copenhagen, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hamburg, Genoa, Lyons and Rotterdam), concluding that Hamburg is the city with the brightest prospects on the market of urban tourism; Marks (Citation1996) studied the case of Zanzibar, where Stone Town was actively pursuing a broad initiative to attract tourism, and it concluded that while a tourist-driven conservation approach could be a means of economic revitalization, the program was resulting the margination of the poor because the process should be more participatory; Potier and Cazes (Citation1998) studied the French urban tourism and concluded with a typology of the consumption practices of French tourists, while O’Neill (Citation1998) pinpointed the success factors that are considering significant for three major cities in the United States of America: Boston, San Antonio, and San Francisco, among others.Footnote6

The tourism sector is susceptible and vulnerable to crises and disasters (Cró & Martins, Citation2017; Smeral, Citation2010). The literature offers some works that analyze the effects of crises on urban and rural tourism. Leslie and Black (Citation2006) found that rural tourism in the UK is more susceptible to crisis than urban tourism.

Over the years, the scientific literature related to the impact of crises on tourism has increased. Examples are the energy crises of the 1970s (Frechtling, Citation1982; Schulmeister, Citation1979; Solomon & George, Citation1976), the Asian Financial Crisis at the end of the 1990s (Henderson Citation1999; Law, Citation2001; Prideaux, Citation1999; Prideaux & Witt, Citation2000), the Turkish crisis of 2001 (Okumus, Altinay & Arasli, Citation2005; Okumus & Karamustafa, Citation2005), and especially the Global Financial and Economic Crisis (Ritchie et al., Citation2010; Li, Blake & Cooper, Citation2010; Song et al., Citation2011; Varvaressos et al., Citation2017; Duan et al., Citation2022; etc.). These studies are based on the impact of crises on tourist demand and use variables such as arrivals, incomes, or expenses. All of them conclude that tourism is a sector that is very vulnerable to economic crises. However, none of these studies have used fractional integration to determine the temporary scope of the shocks.

Evidently, Brexit has had important effects on tourism in the UK and some studies have analyzed this impact. Douch and Edwards (Citation2021) demonstrated that the performance in tourism exports in the UK following Brexit has been poor. Dutta et al. (Citation2021) found long-term persistence in volatility in tourists travelling to the UK and concluded that the Brexit referendum created ambiguity among tourists coming to the UK.

The literature has also analyzed the impact on the sector of pandemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Dwyer, Forsyth & Spurr, Citation2006; Zeng et al., Citation2005) or the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic (Kongoley-MIH, Citation2015; Maphanga & Henama, Citation2019; Novelli et al., Citation2018). All of these conclude that the impact of pandemics on tourism is strongly negative and that it is necessary to protect tourism before the arrival of new pandemics.

However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, attention to the impact of pandemics on tourism has increased in the scientific literature because it has been the sector most affected (Perles-Ribes et al., Citation2021). Karabulut, Bilgin, Demir and Doker (Citation2020) analyzed the impact of the pandemic on tourist arrivals using the newly developed index (Discussion about Pandemics Index) and concluded that the impact of Covid-19 is difficult to predict because this has been the first time the world has suffered a global pandemic of this magnitude.

The rapid rise that sharing economy platforms were having in the tourism sector before the pandemic was abruptly interrupted. Many papers looked at the impact of the pandemic on these platforms, for example in Airbnb, that suffered a strong effect (Fialova & Vasenska, Citation2020; Gerwe, Citation2021; Lecuyer, Marais & Gurău, Citation2023, among others). This platform implemented strategies to transfer its risk to hosts and many of them left the platform. However, the need to maintain physical distance has led many tourists prefer Airbnb entire apartments to hotels (Benítez-Aurioles, Citation2021; Nicolau, Sharma, Shin & Kang, Citation2023). Benítez-Aurioles (Citation2022) also studies the impact of Covid-19 on the peer-to-peer (P2P), using monthly data from Airbnb listings in 22 cities worldwide. She shows not only a decrease in accommodation supply, but a decline in prices and demand. Suárez-Vega, Pérez-Rodríguez and Hernández (Citation2023) show that the efficiency of P2P accommodation such as Airbnb or Home Away was high before the COVID-19 pandemic but decreased during the lockdown period in the Canary Islands (Spain), especially for Home-Away platform.

There are many methodologies that analyze the persistence of tourism after a shock. Some of them use the conventional unit root tests or alternative univariate time series models (Goh & Law, Citation2002; Cho, Citation2003; Lean & Smyth, Citation2008, Citation2009; Tang, Citation2011; Liang, Citation2014; etc.). To study the persistence in time series and the impact of exogenous shocks, Gil-Alana et al. (Citation2004) introduced the test for fractional integration. They concluded that the Spanish tourism demand series showed seasonal long memory and mean reverting behavior, and that it was not necessary to apply strong policies to reverse the series. The same conclusions were reached with other international monthly tourist arrivals data (Gil-Alana, Citation2005). Similar evidence was reached for the international tourist arrivals in the United States (Gil-Alana & Payne, Citation2018), Australia tourism (Assaf et al., Citation2011); UK tourism (Nowman & Van Dellen, Citation2012); Taiwan travel and tourism (Chen & Malinda, Citation2014); Singapore tourism (Al-Shboul & Anwar, Citation2017) or Iceland tourism (Gil-Alana & Huijbens, Citation2018), among many others.

Fractional integration is also used in many papers to study the persistence of tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic. Yucel et al. (Citation2022) studied the effects of COVID-19 on Turkey’s tourism sector using a fractional integration approach to determine if the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector was permanent or transitory. There are many other papers that apply this methodology and focus on the tourism sector in Turkey (Yucel et al., Citation2022), Spain (Gil-Alana & Poza, 2020; Claudio-Quiroga et al., Citation2022), Croatia (Payne, Gil-Alana & Mervar, Citation2022), Australia (Solarin, Claudio-Quiroga & Gil-Alana, Citation2023), among others. With the exception of the latter, whose results indicate that the Covid-19 pandemic had not produced significant changes in the persistence of the Australia’s tourism series, all others showed important changes and the need for strong policy measures.

However, there are not many studies that analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urban tourism. These studies analyze the cases of several cities to extract some lessons applicable to urban tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, for example, Paddison and Hall (Citation2023) focus on the city of York, UK; Gafter, Tchetchik and Shilo (Citation2022) on Eilat, Israel; Madani (Citation2023) on Sareyn, Iran; Bærenholdt and Meged (Citation2023) on Copenhagen, Denmark; Braga et al. (Citation2023) on Oporto, Portugal; Gao, Sun and Zhang (Citation2021) on the city of Nanjing, China; etc. Most of them aim to draw lessons from Covid-19 to identify opportunities for improvement in urban tourism. Some authors affirm that the COVID-19 pandemic has provided new opportunities to accelerate sustainable development of urban tourism (Jiricka-Pürrer et al., Citation2020). Li et al. (Citation2021) analyze tourism development trends in China, both urban tourism and rural tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic and find that the impact on the hospitality industry in cities is strong. Other studies such as Józefowicz (Citation2021), which focuses on urban tourism in Poland, reveals the severe impact of the pandemic on this sector.

Evaluating the effect of the pandemic on urban tourism and estimating the degree of persistence under these circumstances is extremely relevant because it has implications for necessary policy measures. This is the goal of our study, which aims to determine the persistence and detect transitory or permanent effects of the pandemic on tourism of three important European cities, specifically, London, Berlin and Manchester. We next present the methodology used in the article.

4. Methodology

As earlier argued, we use fractional integration methods, which means that the number of differencing to be taken in the data to render it stationary I(0) may be a fractional number. These models, originally proposed by Granger (Citation1980), Granger and Joyeux (Citation1980) and Hosking (Citation1981), have been widely used in the analysis of time series, and they are more general than the classical ARMA-ARIMA approaches where the number of differences is supposed to be 0 (ARMA) or 1 (ARIMA).

Fractional integration belongs to a broader class of models denominated long memory (LM) or long-range dependence (LRD) processes, which are characterized because the infinite sum of their autocovariances is infinite. An alternative definition, based on the frequency domain, indicates that LM is present if the spectral density function (s.d.f.) of the process displays at least one pole or singularity (i.e., a value that goes to infinity) at a given frequency. Among the many models that satisfy the two aforementioned properties and one which is very much employed by time series analysts is one based on fractional integration. A process xt, t = 0, ±1, …, is said to be integrated of order d, and denoted by I(d) if it can be represented as:

(1)

(1)

where B is the backshift operator, and ut is a process integrated of order 0 or short memory, which is characterized because the infinite sum of the autocovariances is finite (or, in the frequency domain if the s.d.f. is positive and bounded at all frequencies). The I(0) processes include white noise but also models that allow for weak dependence such as the stationary AutoRegressive Moving Average (ARMA)-class of models. The parameter d in (1) can be any real value, and if d is positive, xt displays long memory since the s.d.f. of the process tends to infinity at the smallest (zero) frequency. If ut in (1) follows an ARMA (p, q) process, xt is said to be an AutoRegressive Fractionally Integrated Moving Average ARFIMA(p, d, q) process.

To allow for some degree of generality, in the empirical application carried out in the following section, we introduce a constant and a linear time trend, and since the data are monthly, a seasonal autoregression (AR) is adopted for the error term. Thus, the model of interest is the following one,

(2)

(2)

where yt refers to the observed time series data; α and β are unknown parameters to be estimated, namely a constant and the linear time trend; B indicates the backshift operator such that Bkxt = xt-k; xt stands for the regression errors, assumed to be integrated of order d or I(d), meaning that ut is integrated of order 0 (I(0)); moreover, given the seasonal nature inherent to the data, a seasonal (monthly) AR(1) process is assumed for the I(0) disturbances ut, where ρ is the seasonality indicator, and εt is a white noise process with NID(0, σ2) distribution.

We estimate the parameters in the model by using a frequency domain expression of the Whittle function, which is basically an approximation of the likelihood, and, to implement this goal, we use a simple version of Robinson’s (Citation1994) tests widely used in the empirical literature on fractional integration (see, e.g., Gil-Alaña & Robinson, Citation1997; Gil-Alana & Moreno, Citation2012; Abbritti et al., Citation2016; Abbritti et al., Citation2023; etc.). This method uses the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) principle and is based on testing the null hypothesis:

(3)

(3)

in EquationEq. (2)

(2)

(2) , where do is a given scalar real value of any range. Hence, we can test the non-stationarity using values of do that fall outside the stationarity range (e.g., do ≥ 0.5) without needing to differentiate the series. The limiting distribution is standard normal for any do, and this behavior is unaffected by the inclusion of deterministic terms like those included in the first equality in EquationEq. (2)

(2)

(2) . Finally, the test is supposed to be the most efficient one when directed against local alternatives to (3). A full description of the version of the testing procedure used in this work can be found in Gil-Alaña and Robinson (Citation1997).

5. Data

For the elaboration of this research, we have used data from hotel occupancy collected by HotStats.Footnote7 The data include monthly values on overnight stays in London, Manchester and Berlin. Data for London begin in October 1997, for Berlin in March 2004, while those for Manchester in January 2006. All end in February 2024. The number of hotels collected in the sample increases as more hotels join the service provided by HotStats. The data refer mostly to branded hotels, more than small independent hotels, and cover all segments, including economy, select-service, extended-stay, full-service and luxury. HotStats is a company specialized in aggregated information related to the hotel world that has an excellent reputation in the sector; it provides financial benchmarking and market information across the industry to help the industry maintain financial consistency and help any hotel or business to optimize its overall performance. The limitation of our data is that it includes only overnight stays in hotels, predominantly branded, and this sector is much wider, especially since 2008 when Airbnb’s presence in the sector began to be significant; according to Horwath HTL, from the last fifteen years the growth and expansion of branded hotels and their wider significance in the sector is inexorable.Footnote8

displays some descriptive statistics. The first thing we observe is that while Berlin presents the lowest mean (68.4), and London (74.5) and Manchester (74.1) have higher ones; all three cities have high rates, over the monthly worldwide occupancy rate, which confirms the importance of the sector.Footnote9 also shows that Berlin has the highest standard deviation (18.8), so it is the most volatile city within this group and London is the least (16.8) with the lowest standard deviation. , and represent the data and clearly show the seasonality and the hard effect of COVID 19 pandemic.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

6. Empirical results

We estimate the differencing parameter d and the rest of the parameters of the model in EquationEq. (2)(2)

(2) , initially under three potential set-ups corresponding to the cases of (i) no deterministic terms, i.e., supposing that α and β are equal to zero a priori in (2); (ii) including only an intercept or a constant, i.e., under the assumption that β = 0 a priori, and (iii) allowing the two coefficients, i.e., α and β, to be estimated from the data and thus incorporating an intercept and a linear time trend. Then, we choose the most adequate specification of the three by looking at the t-values of these estimated parameters, starting from the model with a constant and a linear trend, and descending to the case of an intercept, and, if this parameter is also insignificant, to the case with no deterministic terms. Note that the first two equalities in (2) can be jointly expressed as

(3)

(3)

where

and noting that ut is I(0) by construction, standard t-values hold in (2).

displays the estimated coefficients for each series using data that end in December 2019, that is, a few periods (months) before the starting of the Covid-19 pandemic. Panel i) refers to the original data while Panel ii) reports the estimates for the logged values. We report for each of the three series the estimated value of the differencing parameter d, along with the values of the potential deterministic terms and the seasonal AR coefficient.

Table 2. Estimated coefficients in the model given by EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) .

The first thing we observe in is that the time trend is required in case of the data referring to Berlin, but not for London and Manchester where an intercept is sufficient to describe the deterministic part. The estimates of d are very similar in the two cases (original and logged values) and in all series the values are in the interval (0, 1) supporting long memory and fractional integration. These values are 0.62 for London, 0.36 (0.37 with logs) for Berlin, and 0.45 (0.43) for Manchester. In the case of Berlin, the time trend coefficient is positive, implying a continuous increased number of tourists in that city, and seasonality seems to be an important factor in the three cities. According to these results, long memory (d > 0) is a feature of the data, and the three series display a mean reverting pattern (d < 1) with shocks disappearing in the long run.

We next conduct the analysis extending the sample up to February 2024. The results, displayed in , are completely different: the time trend coefficient is now statistically insignificant in the three cases, and the estimates of d are now much higher than before. In fact, they are higher than 1 in all cases. With the original data (panel i) the unit root null hypothesis cannot be rejected for Berlin, but it is rejected in favor of d > 1 for the other two cities. Using logs, d is found significatively above 1 for London and the null hypothesis of d = 1 cannot be rejected for Berlin and Manchester. The seasonal AR coefficient is now much lower, especially when the logged values are used. Thus, a substantial increase in the degree of persistence is observed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The three cities clearly increase the degree of persistence with the data up to 2024, London multiplies its degree of persistence by 1.8, while Berlin does so by 2.6 and Manchester by 2.4.Footnote10 However, since there aren’t significant differences in the values of the three cities, the effects of Brexit don’t seem to be conclusive. At this moment we cannot identify what part of this increase corresponds to Covid 19 or to Brexit. In fact, the three series show now lack of mean reversion, implying that the authorities should dedicate more efforts to recover the series to their original long-term projections. The series show how, although there is still a lack of mean reversion, over time the results are closer to pre-pandemic values, which also shows a priori the success of the policies applied. The data also show a generalized substantial reduction in the seasonal component. The reduction in the seasonal component is clearly also a consequence of the pandemic in the three cities. There are no major differences in the behavior of this variable in the three cities either before or after Covid, and the evolution is similar in the three cities which present a significant decrease in seasonality. There is simply a very slight decrease in the Manchester result with respect to London with the logged data. In this sense, it should be noted that it is still too early to see if this trend of lower seasonality will continue in the future.

Table 3. Estimated coefficients in the model given by EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) .

7. Discussion and conclusions

Through persistence analysis, this research shows the influence that exogenous shocks such as the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit have had on hotel occupancy in three European cities (London, Manchester and Berlin). Our study contributes to determine whether the Covid-19 pandemic will have transitory or permanent effects on tourism in these European cities and also to show if Brexit has had an immediate effect in this sector. Its implications are crucial for policy makers as, depending on these results, strong policy actions may or may not be needed.

Using fractional integration techniques, we have checked if the level of persistence of the series, which is measured by the fractional integration parameter, has changed over time due to the pandemic, testing if the shocks in the series have had a transitory effect (if d < 1) or permanent (d ≥ 1) effect. Our results, consistent with the literature reviewed in this regard on the effect of pandemics on tourism,Footnote11 show that the effect of Covid-19 has been especially significant in hotel overnight stays in the three cities analyzed. In addition, the increase in the level of persistence observed with post-pandemic data motivates the shift from mean reversion, before Covid-19, to the lack of mean reversion after it.

This result is extremely interesting since the literature shows how, applying fractional integration techniques to tourism series prior to Covid-19, they showed seasonal long memory and mean reverting behavior, so it was not necessary to apply strong policies to reverse the series, while after Covid-19 the situation changes.

The analysis carried out also confirms the results of Gil-Alana and Poza (Citation2022) for Spain in the sense that the Covid-19 pandemic has increased the persistence of the effects of shocks in the series. Before Covid-19 pandemic, our results indicate that the value of d was significantly less than 1 in the three series with data ending in December 2019, that is, the shocks had a transitory effect. However, including the data until February 2024, the value of d substantially increases, being unable now to reject the null of a unit root, that is, an order of integration equal to 1, and implying permanent effects of shocks. These results suggest, as Škare et al. (Citation2021) show, that strong policy measures are needed to reassume pre-crisis trends in the tourism industry. The actions that are being developed in general in the sector, seems to corroborate these results. In this sense we can mention as an example the fact that, as Pappalepore and Gravari-Barbas (Citation2022) highlight when analyzing a study made by London and Partners (2021), in London, in this year, locals were considered for the first time as the main recipients of London tourist destinations and were considered firstly when designing the marketing strategy. The example of Krakow, studied by Kowalczyk-Anioł et al. (Citation2021), also illustrates the need to articulate new policies to address the crisis to strengthen public-private cooperation in this area and shows the actions that are being developed in that city to deal with the effects that the pandemic has had on the sector.

Our study may contribute in the future to determine whether the COVID-19 shock will have transitory or permanent effects on urban tourism. Its implications are crucial for policy measures, that as suggested by the studies about the impact of COVID-19 on urban tourism such as Sharifi (Citation2021), policy makers should apply the lessons learned from the pandemic.

Regarding the impact of Brexit on overnight hotel stays we can also observe how the persistence rate has increased in Manchester at a higher rate than in London, which seems to confirm the predictions of McCann et al. (Citation2021) in the sense that Brexit will expand regional differences in England, increasing London’s advantage. To try to counteract this effect, specific policies are also being implemented in Manchester to boost the sector with the aim of turning the city into a host of important events adapting its infrastructures to this level.Footnote12

It is also interesting to notice how our analysis does not show substantial differences between the behavior of English and German cities: in the three cases the persistence level increases up to similar levels. Though it is true that it is early to draw definitive conclusions, the first evolution seems to indicate that, despite the widening inter-regional gap in England, Brexit has not significantly affected hotel occupancy in England in a different way than in Germany; in both countries, the level of persistence increases and the level of seasonality decreases.

The article has some limitations. For example, the linear structure used in the model may be extended to incorporate non-linearities. In fact, this is an issue that it is intimately related with fractional integration (see, e.g., Arouri et al., Citation2012; Diebold & Inoue, Citation2001; Granger & Hyung, Citation2004; etc.). Thus, further research may incorporate the shocks in terms of structural breaks, and the joint incorporation of both in a simple model may give us additional information about the nature of the data. As an alternative, non-linear deterministic trends based on Chebyshev polynomials in time (Cuestas & Gil-Alana, Citation2016), Fourier functions in time (Gil-Alana & Yaya, Citation2021) or other deterministic structures can also be incorporated into the model. In addition, for future research, it would be interesting consider incorporating to the study data on overnight stays on P2P platforms, to contrast the extent to which hotel overnight stays are representative of the evolution of the sector.

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Gloria Claudio-Quiroga was involved in the design of the analysis. She wrote the introduction and literature review and interpreted the final results. She approved the final version submitted. Dr. Cecilia Font de Villanueva participated providing the dataset, along with the introduction, literature review and conclusions. She also approved the final version submitted. Prof. Luis Alberiko Gil-Alana proposed the original idea. He was involved in the design and programming of the codes for the empirical analysis and the final approval of the version submitted.

Acknowledgments

Comments from the Editor and two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

There are no competing interests with the publication of the present manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data have been collected from HotStats (https://www.hotstats.com/) and they are available from the authors upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gloria Claudio-Quiroga

Gloria Claudio-Quiroga is Associate Professor of Economics at the Francisco de Vitoria University in the Faculty of Law, Business and Government, Madrid, Spain. Visiting professor at Notre Dame University, Mendoza College of Business, US., and researcher of Yiwu Industrial & Commercial College, China. She completed her PhD at the Complutense University, Madrid, Spain, in 1994. She has published in theoretical and applied econometrics and in tourism, macroeconomics, international relations, and many other disciplines including economic development and environmental issues. He has published papers in journals such as Current Issues in Tourism, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, International Affairs and others.

Cecilia Font de Villanueva

Cecilia Font de Villanueva is Professor of Economic and Business History at the Francisco de Vitoria University in the Faculty of Law, Business and Government, in Madrid, Spain. She holds a PhD in Economic Theory from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (2004) and a Master’s Degree in Philosophy (2006) and in Humanities from the Francisco de Vitoria University (2007). Throughout her academic career she has participated in competitive research projects and is the author of relevant scientific publications. She is a research member of the Francisco de Vitoria Institute of Economic and Social Research and anonymous evaluator of several journals.

Luis Alberiko Gil-Alana

Luis Alberiko Gil-Alana is Full Professor of Econometrics and the University of Navarra and Senior Researcher at the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, in Madrid, Spain. He completed his Ph.D. at the London School of Economics, LSE, in London in 1997. He has worked at the European University Institute, EUI, in Florence, Italy; the London Business School, LBS, in London, and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, in Germany. He has published more than 400 papers on theoretical and applied econometrics, in journals such as Journal of Econometrics, Journal of Applied Econometrics, Journal of Climate, Annals of Tourism Research, Tourism Management, etc.

Notes

1 See Section 3.

2 https://www.statista.com/statistics/598093/travel-and-tourism-gdp-total-contribution-united-kingdom-uk/. Accessed: 5th April 2024.

3 https://www.statista.com/statistics/644714/travel-tourism-total-gdp-contribution-germany/. Accessed: 5th April 2024.

4 https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/487720/turistas-internacionales-en-los-principales-destinos-europeos/Accessed: 5th April 2024.

5 https://www.statista.com/statistics/289010/top-50-uk-tourism-destinations/Accessed: 5th April 2024.

6 Other interesting studies on urban tourism include papers on Asia (Dixit, Citation2020), Africa (Leonard et al., Citation2020, Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2021) or the Middle East (Henderson, Citation2014; Khirfan, Citation2011; Zaidan, Citation2016 or Timothy, Citation2018). Recent overviews include Bellini and Pasquinelli (Citation2016), Morrison and Coca-Stefaniak (Citation2021), Ba et al. (Citation2021) and Van Der Borg (Citation2022).

9 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1339064/worldwide-hotels-occupancy-rate-by-month/#:∼:text=The%20global%20hotel%20occupancy%20rate,pandemic%20on%20the%20hotel%20industry. Accessed 7th April 24.

10 Using the original data in Table 3.

11 See Section 3.

12 As an example of this we can mention the future construction of a first-class Marriott hotel or the plan to expand Manchester Airport to accommodate further growth in passenger numbers to 2027. See https://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/200074/planning/6573/core_strategy_2012-2027 and https://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/200074/planning/6223/general_evidence/3.

References

- Abbritti, M., Carcel, H., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Moreno, A. (2023). Term premium in a fractionally cointegrated yield curve. Journal of Banking & Finance, 149, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2023.106777

- Abbritti, M., Gil-Alana, L. A., Lovcha, Y., & Moreno, A. (2016). Term structure persistence. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 14(2), 331–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjfinec/nbv003

- Al-Shboul, M., & Anwar, S. (2017). Long memory behavior in Singapore’s tourism market. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(5), 524–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2125

- Arouri, M., Hammoudeh, S., Lahiani, A., & Nguyen, D. K. (2012). Long memory and structural breaks in modeling the return and volatility dynamics of precious metals. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 52(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2012.04.004

- Ashworth, G. J. (1989). Accommodation and the historic city. Built Environment, 15(2), 92–100.

- Assaf, A., Barros, C. P., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2011). Persistence in the short and long term tourist arrivals to Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 50(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362787

- Ba, C., Frank, S., Müller, C., Laura Raschke, A., Wellner, K. & Zecher, A. (2021). The power of new urban tourism: Spaces, Representations and contestations. Routledge.

- Bærenholdt, J. O., & Meged, J. W. (2023). Navigating urban tourism planning in a late-pandemic world: The Copenhagen case. Cities, 136, 104236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104236

- Barrera-Fernández, D., Hernández-Escampa, M., & Vázquez, A. B. (2016). Tourism management in the historic city. The impact of urban planning policies. International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism, 2(4), 349–367.

- Bellini, N., & Pasquinelli, C. (2016). Tourism in the city: Towards an integrative agenda on urban Tourism. Springer International Publishing.

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. (2021). Recent trends in the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation. E-Review of Tourism Research, 18(4), 478–494.

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. (2022). How the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation has responded to COVID-19. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(2), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-07-2021-0140

- Berg, L. V. D., Borg, J. V., & Meer, J. V. (1995). Urban tourism: Performance and strategies in eight European cities. Avebury.

- Braga, J. L., Otón, M. P., Pereira, M., Mota, C., Magalhães, M., & Leite, S. (2023). Efectos de la Pandemia sobre el Turismo Urbano en la Ciudad de Oporto. En Avances en turismo, tecnología y sistemas: artículos seleccionados de ICOTTS 2022, vol. 1 (pp. 683–698). Springer Nature Singapur.

- Chen, J. H., & Malinda, M. (2014). Long memory and multiple structural breaks in the returns of travel and tourism indexes. Journal of Economic and Business, 5(9), 1460–1472.

- Cho, V. (2003). A comparison of three different approaches to tourist arrival forecasting. Tourism Management, 24(3), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00068-7

- Claudio-Quiroga, G., Gil-Alana, L. A., Gil-López, Á., & Babinger, F. (2022). A gender approach to the impact of COVID-19 on tourism employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(8), 1818–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2068021

- Cró, S., & Martins, A. M. (2017). Structural breaks in international tourism demand: Are they caused by crises or disasters? Tourism Management, 63, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.05.009

- Cuestas, J. C., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2016). non-linear approach with long range dependence based on Chebyshev polynomials. Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics, 23, 445–468.

- Diebold, F. X., & Inoue, A. (2001). Long memory and regime switching. Journal of Econometrics, 105(1), 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(01)00073-2

- Dixit, S. (2020). Tourism in Asian cities. Routledge.

- Douch, M., & Edwards, T. H. (2021). The Brexit policy shock: Were UK services exports affected, and when? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 182, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.12.025

- Duan, J., Xie, C., & Morrison, A. M. (2022). Tourism crises and impacts on destinations: A systematic review of the tourism and hospitality literature. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(4), 667–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348021994194

- Dutta, A., Mishra, T., Uddin, G. S., & Yang, Y. (2021). Brexit uncertainty and volatility persistence in tourism demand. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(16), 2225–2232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1822300

- Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Spurr, R. (2006). Effects of the SARS crisis on the economic contribution of tourism to Australia. Tourism Review International, 10(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427206779307231

- Edwards, D., Griffin, T., & Hayllar, B. (2008). Urban tourism research: Developing an agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), 1032–1052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.09.002

- Fialova, V., & Vasenska, I. (2020). Implications of the Covid-19 crisis for the sharing economy in tourism: The case of Airbnb in the Czech Republic. Economic & Managerial Spectrum/Ekonomicko-Manaz? é Rske Spektrum, 14(2), 78–89.

- Frechtling, D. C. (1982). Tourism trends and the business cycle. Tourism Management, 3(4), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(82)90051-6

- Gafter, L., Tchetchik, A., & Shilo, S. (2022). Urban resilience as a mitigating factor against economically driven out-migration during COVID-19: The case of Eilat, a tourism-based city. Cities (London, England), 125, 103636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103636

- Gao, Y., Sun, D., & Zhang, J. (2021). Study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the spatial behavior of urban tourists based on commentary big data: A case study of Nanjing, China. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(10), 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10100678

- Gerwe, O. (2021). The Covid-19 pandemic and the accommodation sharing sector: Effects and prospects for recovery. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 167, 120733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120733

- Gil-Alana, L. A. (2005). Modelling international monthly arrivals using seasonal univariate long-memory processes. Tourism Management, 26(6), 867–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.003

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Huijbens, E. H. (2018). Tourism in Iceland: Persistence and seasonality. Annals of Tourism Research, 68, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.002

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Moreno, A. (2012). Uncovering the US term premium: An alternative route. Journal of Bankingand Finance, 36(4), 1181–1193.

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Payne, J. E. (2018). Data measurement and the change in persistence of tourist arrivals to the US in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Tourism Economics, 24(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816617719161

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Poza, C. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on the Spanish tourism sector. Tourism Economics, 28(3), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620959914

- Gil-Alaña, L. A., & Robinson, P. M. (1997). Testing of unit root and other nonstationary hypotheses in macroeconomic time series. Journal of Econometrics, 80(2), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(97)00038-9

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Yaya, O. (2021). Testing fractional unit roots with non-linear smooth break approximations using Fourier functions. Journal of Applied Statistics, 48(13–15), 2542–2559. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2020.1757047

- Gil-Alana, L. A., De Gracia, F. P., & CuÑado, J. (2004). Seasonal fractional integration in the Spanish tourism quarterly time series. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503258843

- Goh, C., & Law, R. (2002). Modeling and forecasting tourism demand for arrivals with stochastic nonstationary seasonality and intervention. Tourism Management, 23(5), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00009-2

- Granger, C. W. J. (1980). Long memory relationships and the aggregation of dynamic models. Journal of Econometrics, 14(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(80)90092-5

- Granger, C. W. J., & Hyung, N. (2004). Occasional structural breaks and long memory with an application to the S&P500 absolute stock returns. Journal of Empirical Finance, 11(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2003.03.001

- Granger, C. W. J., & Joyeux, R. (1980). An introduction to long memory time series and fractional differencing. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 1(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1980.tb00297.x

- Henderson, J. C. (1999). Asian tourism and the Financial Indonesia and Thailand compared. Current Issues in Tourism, 2(4), 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683509908667857

- Henderson, J. C. (2014). Global gulf cities and tourism: A review of Abudhabi, Doha and Dubai. Tourism Recreation Research, 39(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2014.11081329

- Hosking, J. R. M. (1981). Modelling persistence in hydrological time series using fractional differencing. Water Resources Research, 20(12), 1898–1908. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR020i012p01898

- Jiricka-Pürrer, A., Brandenburg, C., & Pröbstl-Haider, U. (2020). City tourism pre-and post-Covid-19 pandemic–messages to take home for climate change adaptation and mitigation? Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 31, 100329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100329

- Józefowicz, K. (2021). Urban tourism and Covid-19 in Poland. REGION, 8(2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.18335/region.v8i2.364

- Karabulut, G., Bilgin, M. H., Demir, E., & Doker, A. C. (2020). How pandemics affect tourism: International evidence. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102991

- Khirfan, L. (2011). World heritage, urban design and tourism: Three Cities in the Middle East. Routledge.

- Köhler, A. F. (2013). Public policies of urban regeneration and promotion of leisure, tourism and entertainment: The creation of urban tourism precincts in Manchester, England. Cuadernos de Turismo, 32, 311–314.

- Kongoley-Mih, P. S. (2015). The impact of Ebola on the tourism and hospitality industry in Sierra Leone. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 5(12), 542–550.

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J., Grochowicz, M., & Pawlusiński, R. (2021). How a tourism city responds to COVID-19: A CEE perspective (Kraków case study). Sustainability, 13(14), 7914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147914

- Law, R. (2001). The impact of the Asian Financial Crisis on Japanese demand for travel to Hong Kong: A study of various forecasting techniques. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 10(2/3), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400109511558

- Lean, H. H., & Smyth, R. (2008). Are Malaysia’s tourism markets converging? Evidence from univariate and panel unit root tests with structural breaks. Tourism Economics, 14(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000008783554820

- Lean, H. H., & Smyth, R. (2009). Asian financial crisis, avian flu and terrorist threats: Are shocks to Malaysian tourist arrivals permanent or transitory? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 14(3), 301–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660903024034

- Lecuyer, C., Marais, M., & Gurău, C. (2023). Maintaining legitimacy in times of crisis for sharing economy platforms: Airbnb’s relational strategies during COVID-19 and impacts on sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 430, 139670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139670

- Leonard, R., Musavengane, R., & Siakwah, P. (2020). Sustainable urban tourism in sub-Saharan Africa: Risk and resilience. Routledge.

- Lerario, A., & Di Turi, S. (2018). Sustainable urban tourism: Reflections on the need for building-related indicators. Sustainability, 10(6), 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061981

- Leslie, D., & Black, L. (2006). Tourism and the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK: Reactions, responses and realities with particular reference to Scotland. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 19(2-3), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v19n02_04

- Li, S., Blake, A., & Cooper, C. (2010). China’s tourism in a global financial crisis: A computable general equilibrium approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491899

- Li, Z., Zhang, X., Yang, K., Singer, R., & Cui, R. (2021). Urban and rural tourism under COVID-19 in China: Research on the recovery measures and tourism development. Tourism Review, 76(4), 718–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2020-0357

- Liang, Y. H. (2014). Forecasting models for Taiwanese tourism demand after allowance for Mainland China tourists visiting Taiwan. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 74, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2014.04.005

- London & Partners. (2021). London & Partners’ 2020/21 Business Plan Coronavirus. https://files.londonandpartners.com/l-and-p/assets/business-plans-and-strategy/london-and-partners-business-plan-2020-2021.pdf.

- Madani, J. (2023). Future scenarios of urban tourism in the post COVID-19 era from the perspective.

- Maphanga, P. M., & Henama, U. S. (2019). The tourism impact of Ebola in Africa: Lessons on crisis management. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(3), 1–13.

- Marks, R. (1996). Conservation and community: The contradictions and ambiguities of tourism in the Stone Town of Zanzibar. Habitat International, 20(2), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(95)00062-3

- Maxim, C. (2019). Challenges faced by world tourism cities–London’s perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(9), 1006–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1347609

- McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Sevinc, D., & Cepeda-Zorrilla, M. (2021). Rebalancing UK regional and industrial policy post-Brexit and post-COVID-19: Lessons learned and priorities for the future. Regional Studies, 57(6), 1113–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1922663

- Morrison, A., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2021). Routledge Handbook of tourism cities. Routledge.

- Nicolau, J. L., Sharma, A., Shin, H., & Kang, J. (2023). Airbnb vs hotel? Customer selection behaviors in upward and downward COVID-19 trends. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(12), 4384–4406. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0478

- Novelli, M., Burgess, L. G., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). No Ebola… still doomed’–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006

- Nowman, K. B., & Van Dellen, S. (2012). Forecasting overseas visitors into the United Kingdom using continuous time and autoregressive fractional integrated moving average models with discrete data. Tourism Economics, 18(4), 835–844. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2012.0144

- O’Neill, J. W. (1998). Effective municipal tourism and convention operations and marketing strategies: The cases of Boston, San Antonio, and San Francisco. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 7(3), 95–124. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v07n03_06

- Okumus, F., & Karamustafa, K. (2005). Impact of an economic crisis. Evidence from Turkey. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 942–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.001

- Okumus, F., Altinay, M., & Arasli, H. (2005). The impact of Turkey’s economic crisis of February 2001 on the tourism industry in Northern Cyprus. Tourism Management, 26(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.013

- Paddison, B., & Hall, J. (2023). Tourism policy, spatial justice and COVID-19: Lessons from a tourist-historic city. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(12), 2809–2824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2095391

- Pappalepore, I., & Gravari-Barbas, M. (2022). Tales from two cities: COVID-19 and the localization of tourism in London and Paris. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(4), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2021-0199

- Paskaleva-Shapira, K. A. (2007). New paradigms in city tourism management: Redefining destination promotion. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507302394

- Payne, J. E., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Mervar, A. (2022). Persistence in Croatian tourism: The impact of COVID-19. Tourism Economics, 28(6), 1676–1682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816621999969

- Perles-Ribes, J. F., Ramón-Rodríguez, A. B., Such-Devesa, J. M., & Aranda-Cuéllar, P. (2021). The immediate impact of Covid19 on tourism employment in Spain: Debunking the myth of job precariousness? Tourism Planning & Development, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1886163

- Postma, A., Buda, D. M., & Gugerell, K. (2017). The future of city tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-09-2017-067

- Potier, F., & Cazes, G. (1998). Le tourisme et la ville: expériences européennes. Le Tourisme et la Ville. 1–200.

- Prideaux, B. (1999). Tourism perspectives of the Asian financial crisis: Lessons for the future. Current Issues in Tourism, 2(4), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683509908667856

- Prideaux, B., & Witt, S. F. (2000). The impact of the Asian financial crisis on Australian tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 5(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660008722053

- Ritchie, J. R. B., Amaya Molinar, C. M., & Frechtling, D. C. (2010). Impacts of the World Recession and Economic Crisis on Tourism: North America. Journal of Travel Research, 49(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509353193

- Robinson, P. M. (1994). Efficient tests of nonstationary hypotheses. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89(428), 1420–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1994.10476881

- Rogerson, C., & Rogerson, J. (2021). Africa’s capital cities: Tourism research in search of capitalness. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 10(2), 654–669. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-124

- Sassen, S. (2012). Cities in a world economy (fourth). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Schulmeister, S. (1979). Tourism and the business cycle.

- Sharifi, A. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons for urban resilience. In COVID-19: Systemic risk and resilience (pp. 285–297). Springer International Publishing.

- Škare, M., Soriano, D. R., & Porada-Rochoń, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120469

- Smeral, E. (2010). Impacts of the world recession and economic crisis on tourism: Forecasts and potential risks. Journal of Travel Research, 49(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509353192

- Solarin, S. A., Claudio-Quiroga, G., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2023). Persistence in Australian tourism employment industries. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2181149

- Solomon, P. J., & George, W. R. (1976). An empirical investigation of the effect of the energy crisis on tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 14(3), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757601400303

- Song, H., Lin, S., Witt, S. F., & Zhang, X. (2011). Impact of financial/economic crisis on demand for hotel rooms in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 32(1), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.006

- Suárez-Vega, R., Pérez-Rodríguez, J. V., & Hernández, J. M. (2023). Substitution among hotels and P2P accommodation in the COVID era: A spatial dynamic panel data model at the listing level. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(17), 2883–2899. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2111296

- Tang, C. F. (2011). Old wine in new bottles: Are Malaysia’s tourism markets converging? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 16(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.572661

- Teo, P., & Huang, S. (1995). Tourism and heritage conservation in Singapore. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(3), 589–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00003-O

- Timothy, D. (2018). The Routledge handbook of tourism on the Middle East and north Africa. Routledge.

- Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100744

- Van Der Borg, V. (2022). A research agenda for urban tourism. Elgar.

- Varvaressos, S., Papayiannis, D., Lytras, P., & Melissidou, S. (2017). Impacts of economic recession on Greek domestic tourism. Journal of Tourism Research, 17, 155–172.

- Yucel, A. G., Koksal, C., Acar, S., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on Turkey’s tourism sector: Fresh evidence from the fractional integration approach. Applied Economics, 54(27), 3074–3087. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2022.2047602

- Zaidan, E. (2016). Tourism shopping and new urban entertainment: A case study of Dubai. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715589426

- Zeng, B., Carter, R. W., & De Lacy, T. (2005). Short-term perturbations and tourism effects: The case of SARS in China. Current Issues in Tourism, 8(4), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/136835005086682