Abstract

Sustainability serves as a normative principle in the context of food policy but also represents a hotly debated arena. Ongoing crises in contemporary agriculture suggest that the current model of food production may not be sustainable in the long run to guarantee global food security. Advocacy for more comprehensive and sustainable models has increased because of the pressing need to improve agriculture, particularly in Africa. Thus, the status quo cannot be maintained. Agroecology-based food system transformation has received increased attention from social movements, academics, researchers and policymakers. In many countries around the world, agroecology is becoming increasingly popular as a transformative movement. However, it receives little attention in global agricultural research and development plans, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Scaling up agroecological outputs requires amplification. This research explores amplification dynamics through a literature review, providing insights into SSA’s emerging agroecology policy landscape while drawing on Cuba’s experiences. Adopting agroecological practices contributes to accomplishing Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 2 of the United Nations while providing solutions to food insecurity in SSA. The findings suggest that while agroecology is becoming more common and well-known in SSA, its presence is still modest, and there is little policy support for its expansion. Agroecology’s holistic approach with an ecological foundation is yet to take a foothold in SSA’s food system policy arena. Several policy recommendations have been suggested in this review paper to support agroecology research and policy discourse in SSA and its role in transforming agri-food systems.

1. Introduction

The quest for a sustainable food system that guarantees safe, nutritious, affordable food production and anchored on economic, social, and environmental sustainability remains a puzzle worldwide (Knorr & Augustin, Citation2021). Most food that feeds the world is produced in a conventional way, through synthetic fertilizers and mechanized systems, increasing greenhouse gas emission and unintended harmful chemicals such as Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) infiltrating into the human and animal food chain. Present agricultural food systems are not economically transparent and fail to grab the government and corporations’ attention, and their effects are likely to worsen the situation (Béné, Citation2022). Moreover, in developing countries where agriculture accounts for a sizeable proportion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and a source of livelihoods, efforts to shift to sustainable food production practices may remain ignored.

Conventional agriculture emphasizes high productivity, fueling a consumerism centred on the prevalent linear paradigm (‘make-use-discard’) of production and consumption (Reader, Citation2023). This model is akin to the unsustainable trends of Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) systems in national governance and sectoral policies, exacerbating disparities in access to scarce resources (UNEP, Citation2015). Despite the notable rise in food production brought about by the Asian Green Revolution, the intensification and industrialization of food systems that followed brought about adverse repercussions and stressors on the environment and socioeconomic fronts (Soria-Lopez et al., Citation2023). Agriculture needs to cope with a number of issues, including loss of biodiversity, decreased soil fertility from salinization and acidification, soil,water and air pollution, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Other issues include social injustice, rural area neglect, low-quality diets (Migliorini et al., Citation2018). To address these challenges, a transformative shift is imperative, necessitating a new model that not only enhances food production but does so sustainably to the interests of human and the ecosystem as whole.

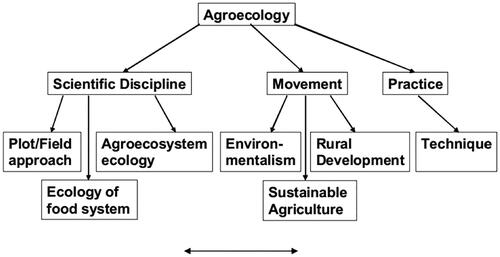

Agroecology as an integrated approach to rethinking agri-food systems for social, environmental, economic, and governance sustainability has been proposed as a more viable option for sustainable food systems (Iocola et al., Citation2022). Recognized as a science, practice, and social movement (Wezel et al., Citation2020), agroecology encompasses using scientific, experiential, and indigenous socio-ecological knowledge to agrifood systems in order to preserve or improve ecosystem processes, provide food, and bring value to ecosystem services (beyond food production) for humans (Ewert et al., Citation2023; Méndez et al., Citation2013; Wezel et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it is connected to the demands made by international agrarian organizations to address power disparities in the global agrifood system, which favour corporate players at the expense of the health and well-being of people and the environment (Patel et al., Citation2009; Wittman, Citation2011). Furthermore, by emphasizing the political and social aspects of production systems, agroecology has been shown to incorporate concepts that support the more environmentally and socially conscious aspects of agriculture (FAO, Citation2019).

For agroecology to change the paradigm of conventional agriculture towards a participatory, transdisciplinary, and action-oriented design of sustainable agroecosystems and food systems, its successful transitions require common understanding of the long-term implications of changes for food systems (Méndez et al., Citation2013; Migliorini et al., Citation2018). The successful progression of agroecology involves amplification of its knowledge and on-the-ground practices, fostering their growth and dissemination, engaging more farming families, and eventually leading to scaling out and territorialization (McGreevy et al., Citation2021). Researchers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), international organizations, and peasant groups are increasingly promoting agroecology to expand its knowledge globally and support the shift to just and sustainable food systems. Some agroecological practices considered and currently promoted include crop diversification, soil management techniques, agroforestry, intercropping, and crop integration (Bezner Kerr et al., Citation2021).

In Africa, specifically sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), agroecology is seen as a great opportunity due to its socioeconomically fragile status from considerable risk of the adverse effects of industrial agriculture such as the increased use of herbicides in weed control (Bàrberi, Citation2019). Currently, the promotion and upscaling of agroecological paradigm is too limited to revolutionise the industry due to anti-corporate and anti-industrial mentality in many African nations (Mugwanya, Citation2019). This could be the result of poorly recognized regional and national opportunities for expanding agroecology in various African social and political contexts, which has slowed down its adoption. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide a review of the challenges and successes associated with agroecology implementation, recent advances in policy developments that might be conducive to agroecological transitions with specialty to SSA. By reviewing the global and regional literature and a case study analysis of Cuba, this study aims to fill a significant knowledge gap related to advancing policies supporting agroecology.

2. Literature review

In this section, literature about the landscape of agroecology policies toward transforming food system’s in SSA is discussed.

2.1. Historical revolution of agriculture

Agriculture as a human activity has undergone several revolutions, starting with the first agricultural revolution founded on the development of seed agriculture and the use of plough and draft animals (Pretty, Citation1991). The second agricultural revolution heralded agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, improved yoke for ox-ploughing, and improved crop production (Dribe et al., Citation2017). This revolution occurred when the Industrial Revolution took shape in England and Western Europe. The third revolution came with mechanization, chemical farming with fertilizers, and widespread food manufacturing. The industrialization of agriculture was prompted by the need to mechanize and infuse chemical and biological innovations in agriculture (Kansanga, Citation2017). The Green Revolution then came as an attempt to improve agricultural yields for a burgeoning world population.

As the industrialization of agriculture took root, there were alleged fears of its impact on the environment. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book ‘Silent Spring’ outlined the impact of industrial agriculture on the environment and the fear that environmental harm could also affect humans (DeMarco, Citation2017). Further, despite the efforts to increase agricultural production, sub-Saharan Africa has consistently lagged global averages. For instance, SSA experienced limited growth in per capita agricultural production during the early 1960s to the 1970s, with intermittent brief periods of growth in the mid-1970s and 1980s (Pretty, Citation1991). Nevertheless, the predominant trend indicates a decline, setting it apart from the trajectory observed in other developing regions. Numerous factors are often cited as contributors to this disparity, including regional climate conditions, soil quality, historical issues like slavery, and prevalent diseases (Bjornlund et al., Citation2020). Discussions and debates towards transitions to sustainable food systems highlight the potential of agroecology to support small farmers in managing challenging environments sustainably (Anderson et al., Citation2019; Wezel et al., Citation2020). This approach aims to meet subsistence needs without relying on mechanization, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, or other contemporary agricultural technologies.

Agroecology first emerged in the 1970s as a scientific approach. However, it progressively evolved into both a movement and a collection of practices during the 1980s (), decreasing the use of chemicals, protecting water and soil, diversifying the production of crops and trees, and livestock (Bottazzi et al., Citation2020). Since then, agroecology has undergone several phases from its initial scientific approach to a more comprehensive system incorporating socio-political and environmental considerations (Laske & Michel, Citation2022). Besides the direct benefits of agroecological practices, indirect benefits include social and peer recognition, inter-influence among farmers, development of farmers’ skills, knowledge, and capabilities, personal initiative, and increased dexterity (Bottazzi et al., Citation2020). However, these benefits have been refuted in some Western studies because smallholder farming employing agroecological practices suffers stiff competition and, at times, fetches low prices, considering the tedious production practices endured in agroecology compared to conventional agriculture. In assessing peasant farmers in Senegal, Boillat et al. (Citation2022) argues that agroecology in Senegal leads to alternative labor control approaches, which may add additional workload to farmers.

However, Mockshell & Kamanda (Citation2018) wades into this debate on which pathway between agroecological Intensification (AEI) and sustainable agricultural intensification (SAI) would be ideal in feeding the world population projected to grow by 40-80% by 2050. In their review, they argue that AEI and SAI assessed based on the social, economic, and environmental pillars of sustainability creates a room for trade-offs and synergy on the areas where the two pathways can enhance wellbeing and at the same time conserve the environment. They conclude that choice for a sustainable path for agricultural transformation should be informed by evidenced-based and consensus-oriented approaches. Given that the main actors of AEI and SAI may have divergent vision for farming, the choice for the practice or an integrated approach to take is pegged on the location-specific situations.

2.2. Agroecology in the global context

As part of the goal to combat hunger, the United Nations hopes to end hunger by 2030 in its blueprint Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda (Arora & Mishra, Citation2022; Shulla & Leal-Filho, Citation2023). The best course for the world to follow has been a topic of discussion as efforts to fix the problems with the food system are explored. In scientific and policy circles, there is a great deal of disagreement over how to address issues like world hunger, malnutrition, deteriorating rural economies, biodiversity loss, and climate change. On the one hand, hypothetical and neoliberal ‘market-based’ solutions, high-input technology-based approaches, and export-oriented agricultural models are proposed by powerful entrenched interests that have strong ties to the government, media, and academic institutions (Valenzuela, Citation2016). Conversely, a global scientific and grassroots food movement has surfaced, advocating for a reform of the global food system to facilitate small-scale agroecological farming practices (Anderson et al., Citation2019; Wezel et al., Citation2020)

The powers have designated industrial agriculture as the formidable option for feeding a world with an ever-growing population. To achieve this, industrial agriculture takes a market-driven, urban-centric, and technocratic approach, leading to human and ecological dislocation. A study assessing the palm oil expansion among smallholders in Mexico showed that smallholder farmers have little agency in the production and, in most cases, are victims of systemic impositions by industrial agriculture promoters (Castellanos-Navarrete & Jansen Citation2018). Efforts to champion agroecology are dampened by modern industrial food systems that gain support from international bodies, such as World Trade Organization (WTO), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. These international bodies facilitate neoliberal policies through the financialization of agriculture in critical industrial agriculture components, guided by the intention to produce much for the world population (Jaworski, Citation2014). In 2018, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) acknowledged that agroecology can change agri-food systems and that it can help achieve most of the SDGs (Gliessman, Citation2018). However, some member states (Canada, Australia, Argentina, and the USA) have objected to the FAO’s efforts to promote agroecology since they do not align with their goals of the development of agriculture (Anderson & Maughan, Citation2021). The primary objection is that agroecology is impractical and unattainable (Bellwood-Howard & Ripoll, Citation2020), and it hardly ever incorporates cutting-edge farming methods for sustainability (Anderson & Maughan, Citation2021).

2.3. Agroecology within Sub-saharan africa

According to the FAO (Citation2018), elements of agroecology are not unique to SSA, where agriculture is practised based on natural conditions and cycles over millennia. SSA faces numerous challenges, such as extreme poverty prevalence, youth unemployment, and food insecurity, which have become thorns in the flesh for the region’s socioeconomic growth and progress. Therefore, boosting food production alone may not create solutions. SSA agriculture is driven by smallholder farmers, who produce 80 percent of the food (FAO, Citation2015). These farmers’ food is highly diverse and dependent on natural ecosystems, such as natural forests, woodlands, grasslands, and aquatic systems (Bottazzi & Boillat, Citation2021). As stated earlier, creating a sustainable food system would require, apart from sufficient food, nutritious food that meets people’s needs—focusing on nutrition shifts our focus from caloric intake, a major pillar in conventional agriculture emphasizing high-energy dense foods such as wheat, maize, and rice production, to avert world hunger. In Africa, agroecology has been practised primarily in West African countries (Mali, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Benin, Togo, and Niger) and Eastern African countries (Tanzania, Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar), primarily by small-scale farmers (Bottazzi & Boillat, Citation2021; Paracchini et al., Citation2020).

Concerns over the environment have become more pronounced after the Asian Green Revolution and the development of agricultural industrial models that promote production and productivity at the expense of the environment (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2012). Prioritizing the environment and its impact on human systems is pegged to the reality that the biophysical-human systems interaction supports agriculture as an economic activity. Food systems depend on the environment and are equally drivers of environmental change (Ericksen, Citation2008). However, Parker & Johnson (Citation2019) notes that policies that should align food production with its ecological consequences are given less attention, as food governance tends to take a productivist approach with plenty of preference over substance. Even so, this is not unusual in developing economies, where population growth elicits worry over feeding an exponentially growing population. Thus, policymakers and governments are quick to pick fixes anchored on neoliberal ideals that regard food as more of a marketable commodity than the social roles it performs.

Some of the current efforts in agroecology are spearheaded by organizations such as the African Biodiversity Network (ABN)Footnote1. The ABN works with several countries to transform the agroecology landscape, where they rally their partners towards seed sovereignty and diversity. ABN embarked on a seed diversity and sovereignty project intending to revive small-scale places in food production and farming systems. The government of Tanzania, working with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like the Research Community and Organizational Development Association (RECODA), Sustainable Agriculture (SAT), Participatory Ecological Land Use Management (PELUM) Tanzania and SWISS AID, and other development partners, initially established agroecological practices in the districts of Mvomero, Bagamoyo, Masasi, Morogoro, and Singida. The objectives of promoting agroecological practices are to simultaneously achieve more environmentally friendly crop production that maintains ecosystems and improve the quality of farm products while also increasing the yields of crops and livestock products. It also aims to improve the livelihood of farmers and other stakeholders along its value chain (Kanjanja et al., Citation2022).

2.3.1. Agroecology and organic farming in Sub-Saharan Africa

The Lusaka Declaration of 2012 marked yet another opportune moment for Africa to propel development in organic agriculture. This was the second conference to take stock of the previous meeting held in Uganda in 2008. The conference was hailed as a momentous opportunity for the continent mainstreaming organic farming into the continent (Gama & Millinga, Citation2016). Thus, even though agroecology had not assumed relevance in the public debate on Africa’s agriculture, organic farming was enjoying a relative eminence.

Organic farming operates on the concept of a circular agricultural production system with reduced inputs (Selvan et al., Citation2023). Organic farming is conceptualized as a sustainable production system mindful of the environment, human health while production is optimized. Building on these three facets, organic farming work to replenish soil fertility, enhance nutritional quality of food, and improve human and animal welfare. Organic farming is a, but a subset of agroecology concerned with sustainable farming practices. The implementation of organic farming is not equally highly successful due to the reason that several factors such as farm’s geographic location that explains the topography, climate, soils, farm type dictates the region where organic farming is practised. Kuo and Peters (Citation2017) observed that regional differences explain why organic production is not uniformly distributed. On the contrary, Adamtey et al. (Citation2016) found that organic farming systems can produce yields equal to conventional systems in Kenya.

Moeller et al. (Citation2023) in their study on the possible indicators for measuring agroecology for attaining tangible indicators observe that agriculture intersects with the social, economic, political, and environmental aspects implying that agriculture’s concern goes beyond food provision but must incorporate impacts from these subsystems. From a food system perspective, agroecology provides a holistic approach designed to encompass various aspects of the food system. They further explained that the extent of agroecology is assessed at the farm and household levels, or the project and portfolio levels. At the farm and household levels, the Tool for Agroecological Performance Evaluation (TAPE) has been widely used in sub-Saharan Africa to assess agroecology, with several frameworks being used to develop TAPE ((Lucantoni et al., Citation2023). However, the development of TAPE seeks to build a uniform assessment tool for the globe. Such developments seek to contradict the co-creation of knowledge, sharing of knowledge, and farm contribution to agroecology. Thus, refraining from using a restricting agroecology assessment tool is ideal in explaining the transition but also for expressing the regional uniqueness to agroecology. For instance, IFAD’S Agroecology Framework dwells on gender, climate change, nutrition and youth, denoting that a single common tool for assessing agroecology denies the context-specificity of agroecology, stagnating the transition process until certain preconditions are met. Even though conformity and uniformity would provide better metric for assessing regional agroecology status, more open tools that embrace location-specific practices would heighten the transition. In Zimbabwe, the role of NGOs in addressing agricultural challenges include promotion of community development through partnerships and advocacy. These strategies are utilized to educate and raise awareness about the significance of certified organic agriculture (Chitiyo & Duram, Citation2019).

However, in a critical rejoinder, Mugwanya (Citation2019) observes that like other projects that have been promoted by the development community, the current structure of agroecological practices currently promoted in SSA, she argues, are constricting by failing to adhere to the contexts of African farmers. Nonetheless, Mugwanya’s conclusion that Africa’s current low use of synthetic fertilizer and low farm mechanization translates to agroecological practices fails to recognize and appreciate the integrative and overarching nature of agroecology.

2.3.2. Challenges of adopting agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa

Promoting agroecology faces several challenges in SSA, including inadequate policy and institutional support, lack of access to credit and markets, limited extension services, and weak land tenure systems (Sinyangwe et al., Citation2023). Agroecology has not found a favorable spot among governments and policymakers, especially in SSA. Areas of contention also involve the use of pesticides, hybrids, and the agroecological requirement of abandoning synthetic fertilizers for organic agriculture. The practicality of dumping synthetic fertilizer is often questioned since African farmers are in a different scenario from other farmers in developed countries, mostly in Europe where agroecology is immensely recognized. Dahlin and Rusinamhodzi (Citation2019) outline that sub-Saharan Africa’s agriculture is a low-input system characterized by low nutrient inputs, insufficient control of weeds, pests, and diseases, and inadequate labor. According to Berberi (2019), socioeconomically fragile areas in SSA, are at a substantial risk of the adverse effects of industrial agriculture due to the increased use of herbicides in weed control. The use of herbicides in weed control is prompted by the need to boost food security by reducing losses attributed to weeds. With such realities, Falconnier et al. (Citation2023) have questioned the practicality of agroecology in helping escape poverty. It appears contradictory to note that inadequate labour affects the region’s agricultural production despite having large populations living in rural areas and much arable land; however, the burden of diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS, and urbanization attracting youths’ towns impact labour supply on the farms (Dahlin & Rusinamhodzi, Citation2019).

Moreover, low investment in agroecology remains a policy concern for the continent. It finds itself at a crossroads in meeting the urgent need for food through industrial models in food production or promoting an agroecological shift for long-term benefits. As the International Panel of Experts in Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) (2020) pointed out, agroecology in Africa was treated as an alternative, with the priority in research funding allocated to industrial agriculture. A better explanation for the low uptake and disproportionate research fund allocation can be understood from the lens of the region’s political economy, where sufficient food production for the population is seen as a government achievement. Still, the Asian Green Revolution bypassed African looms in leaders’ thoughts as a magic silver bullet to boost production. Thus, poor political goodwill to support and entrench agroecological approaches to food production is an impediment that should be addressed if we are to address the diversity of challenges facing the region’s food system. The current government’s subsidy programs for conventional agriculture demonstrate how political goodwill can hamstring agroecological practices by locking out small-scale farmers because of unfair competition. In order to increase the application of agroecology in development contexts, public funding in agroecological research, but particularly in the policy environment that fosters and facilitates development of agroecology is recommended. Yet, as reported by Gliessman (Citation2018), agroecology receives only a small portion of financing for agricultural research in Africa.

Climate change is one of the factors propelling the call to reform farming practices. The dominant farming systems have been shown to impact climate variability due to total reliance on synthetic fertilizers and chemicals for weeds and pests’ control. A study by Abegunde (Citation2017) assessing local communities’ beliefs in climate change in rural SSA revealed that over half of the respondents did not believe in climate change. One of the factors affecting this level of belief was attributed to education status since 55.3% of the respondents were illiterate. Given that climate change and its impact on agricultural systems should form the agency for enhancing agroecological practices, the scepticism, and varied beliefs in climate change.

Another obstacle to adopting agroecological practices is the absence of information on agroecology as a practice, science, and movement. Although agroecology seeks to connect traditional and scientific knowledge in driving agricultural production that respects the environment, a general misunderstanding regards it as a way of replacing the advancement in agricultural technologies with traditional technologies. Wei (Citation2020) argues that in many developing nations, agroecology, in conjunction with information and communication technologies, will constitute smallholders’ ‘precision agriculture’, improving their livelihood and food security. Overall, agroecology has the potential to positively impact agriculture by highlighting its low input requirements and utilizing centuries of local knowledge and experimentation in its research and development on farmers’ fields. This could lead to a more just, equitable, and environmentally sustainable agriculture (Pereira et al., Citation2018). summarizes some of the challenges of adopting agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 1. Challenges of adopting agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa.

2.3.3. Success drivers towards adoption of agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa

Agroecological practices are not a panacea of solutions to the problems in agricultural production. But as demonstrated by Altieri et al. (Citation2017), agroecological practices can be traced even before the concept of agroecology took shape since farmers, through their indigenous knowledge and experimentation, have always incorporated practices meant to improve their yields and at the same time conserving the environment. As a science, agroecology keeps evolving due to new knowledge and scientific research being updated to meet the realities facing farming. Even though opponents of agroecology refute it for failing to achieve crop productivity, AEI is designed to enhance crop productivity through an integrated system of ecological principles into the farm system management (Manyanga et al., Citation2023). But as Nelson & Coe (Citation2013) point out, location-specific approaches can be ideal in the process of embracing agroecology. Comparatively, they observe that through mechanization well established in the developed world, agricultural systems have been transformed into labor-efficient operations, on the contrary smallholder farming systems have remained labour-intensive since they cannot access energy-intensive farming methods.

Generally, intermediary organizations help promote agroecology in many developing nations. El Bilali et al. (Citation2022), for instance, demonstrate how Burkina Faso’s farmers’ organizations function as intermediary actors to facilitate farmers’ uptake of agroecological innovations. Policies can also foster the development of innovative solutions that are suitable for the local and regional context (Pereira et al., Citation2018). These solutions should preferably be based on sustainability metrics. This includes expanding farmers’ access to knowledge and assisting farmer-to-farmer linkages (Lampkin et al., Citation2020). Policies can also establish a conducive atmosphere for incorporating new technology options, including digitalization and novel breeding technologies, into agroecological and sustainable agri-food systems. Furthermore, national policies must take into consideration their impacts on other nations.

Nyantakyi-Frimpong et al. (Citation2016) underscore the challenge of HIV/AIDS in Africa and its impact on labour availability with the choice for agroecological practices that can provide food and nutritional security. Taking the case of Malawi for its high HIV/AID prevalence, the findings of the study showed that smallholder farmers using cereal-legume intercropping experienced high yields and dietary diversity. This study showed that since legume intercropping is not labor intensive, it is ideal for communities in the region burdened by disease and labor loss associated with caregiving. Their findings also indicated that agroecological practices can solve social and economic inequalities on productive resources, enabling the rural communities to enhance their food and nutritional security. Based on this finding, it can be deduced that, though agroecology is labor-oriented, capital-oriented modern agriculture cannot be a better alternative to the disease-burdened smallholders.

Climate-smart agricultural practices (CSAP) have mushroomed in the past few years as the region grapples with climate change effects. CSAPs’ adoption though relatively low at the moment is motivated by the dwindling agricultural productivity, pest and disease pressures, and poor regional economic development exacerbating the vulnerability of the population (Ofori et al., Citation2021; Ogisi & Begho, Citation2023). Agro forestry as a CSAP has been a frontline activity in combating climate change through its role in sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to carbon stored in soil and plant biomass (De Giusti et al., Citation2019). Policies promoting climate change such as agroforestry have a synergistic effect on agroecological practices, as the tree-based land practices work for SSA for soil remediation due to the region’s low crop yields associated with poor soils. Moreover, though with little progress, countries in the region have strived to adopt regenerative agricultural systems as a response to climate change impact on agriculture and the pressures from agricultural production on key natural resources.

Lastly, agroecology has several sub-components, making it a knowledge-intensive practice. It requires techno-scientific knowledge that local farmers can absorb and apply on their farms. A farmer would be required to learn tacit and practical knowledge to ensure the experimentation on intercropping, integrated pest management, biocontrol, landscape design, and soil enhancement techniques. The threats from climate change and the effect of disease and pests on crops put agroecology on the spot regarding its practicality in the face of this change. González-Chang et al. (Citation2020) observes a gap between the knowledge produced on agroecology and farmers’ practices. They suggest this gap can be filled by developing participatory dynamics through which the co-creation of knowledge, sharing, and spreading knowledge is feasible.

2.4. Advances in policies promoting agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa

While modern industrial agriculture takes priority in the policy framework of most developed countries, agroecology’s holistic approach with an ecological foundation is yet to take a foothold in SSA’s food system policy arena. Although agro-ecology is included in Ghana’s agricultural policies, such as the Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy FASDEP I and FASDEP II papers, it only pertains in relation to the agro-ecological zones in the country (Botchway et al., Citation2016; van Rheenen et al., Citation2012). In addressing goals related to environmental sustainability and agricultural production in the nation’s overall development agenda, both policies expressed the government’s ambition to incorporate and promote the scaling up of sustainable land management processes. In 2018, the Togolese government released its National Development Plan, which outlines plans to improve the country’s organic sector from 2018 to 2022 with a 2030 vision. Key components of the program were outlined in a ‘concept note for the national conversion of the agricultural sector to organic’ issued in 2019 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Production and Fisheries (MAPAH). In light of this, MAPAH released the national policy for the development of organic and ecological agriculture for the years 2020–2030 in 2020. These documents show a political commitment to organic agriculture, with the main goal being export growth while simultaneously expanding the home market.

In South Africa, many important policy documents fully support a variety of agroecological concepts. These include the drafts of the Agriculture Sector Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Plan of 2015, the Just Transition Framework of 2022, the Conservation Agriculture Policy draft of 2022, the White Paper on Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity draft of 2022, and the National Policy on Comprehensive Producer Development Support draft of 2019 (ACB, Citation2023). Moreover, in South Africa, the private sector and government organizations adheres to two global standards for organic farming. These are the Codex Alimentarius, or ‘Codex’, and the International Federation of Organic Farming (IFOAM). The IFOAM, has created a number of standards pertaining to organic farming over the years (Uhunamure et al., Citation2021). IFOAM developed two different models for certification pathways, both of which are used in South Africa. The first is the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS), a first-party certification framework, and the Group certification, which is under a third-party certification framework. A group of smallholder farmers can work together to manage the handling, processing, marketing, and production of their organic products under a cooperative or other organization with the help of group certification (Maccari, Citation2022; Namome, Citation2013).

In Madagascar, the first law dubbed National Strategy for Organic Agriculture (SNABIO)organic was promulgated in 2020. Madagascar intends to create a policy that encourages organic farming for both the local and export markets in order to maximize the advantages of this endeavor and democratize access to wholesome, sustainably produced food. On the other hand, the National Organic Agriculture Policy (NOAP) was introduced by Uganda’s Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry, and Fisheries (MAAIF) in 2019. Since then, efforts have been made to put the NOAP into practice by assembling a roadmap that gives priority to developing the supply chain and market, growing agroecology and organic farming at the farm level, and fortifying the established stakeholder platform and policy framework. Furthermore, the roadmap outlines steps to encourage development partners to fund and assist the NOAP’s implementation (Bendjebbar & Fouilleux, Citation2022).

Although the term ‘agroecology’ is absent from Kenya’s agricultural policies, its components and resilience- and productivity-focused techniques are frequently mentioned. Resilience, efficiency, diversity, and synergy are among the 10 agro-ecology elements that are explicitly stated in the national Kenya Climate Smart Agriculture Strategy (KCSAS) and Kenya Climate Smart Agriculture Implementation Framework (KCSAIF) (Karuga, Citation2022). Kenya’s development strategy, Vision 2030, covering the years 2008–2030, seeks to turn the nation into a middle-income nation that offers its people a high standard of living by 2030. Agroecology can contribute to the economic pillar by increasing the value of agriculture through increased productivity and production of niche products such as organic foods for local and international markets. In the social pillar, agroecology will contribute to the health strategy of shifting from a curative to a preventative approach by embracing healthier and more diversified foods. Kenya has organic certification, and the Kenya Organic Agriculture Network (KOAN) represents organic farmers (UNEP, Citation2015). Kenya’s decentralized form of government gives County Governments the freedom to create their own policies based on the conditions at hand. Of the forty-seven counties, Kiambu County is the first to have passed an agroecology law (Nyasimi, Citation2022). Lastly, while Rwanda currently has a few organizations and policies pertaining to ecological organic agriculture (EOA), such as the Rwanda Organic Agriculture Movement (ROAM), the National Agriculture Policy (NAP), and the Strategic Plan for Agriculture Transformation (PSTA) IV (2018–2024), they are insufficiently strong to encourage and support the sustainability of EOA and the necessary revolutionary change in the subsector (Ozor & Nyambane, Citation2021).

2.5. International policies supporting agroecology

The Nyeleni Centre in Mali hosted a gathering of civil society actors in February 2015, including peasants, small-scale and family farmers, indigenous peoples, pastoralists, fishermen, women’s and youth movements, and urban people. The gathering was arranged by the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty. The Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology was then released. The unifying vision, guiding principles, and development methods for agroecology are outlined in the Nyeleni Declaration. It restates the comprehensive and integrated understanding of agroecology as three interconnected pillars: a social movement, an agricultural practice, and a scientific discipline (Nyéléni, Citation2015). Subsequently, at the global level, several international strategies and legal frameworks already exist. To date, only few nations have undertaken a daring, comprehensive, and well-coordinated series of policy changes that have led to concrete and noteworthy pledges to facilitate the agroecological transition from conception to the implementation of all thirteen principles (Nicolétis et al., Citation2019; Wezel & Bellon, Citation2018). Notably, some nations have implemented important policy measures that either directly or indirectly tackle one or more agroecological principles in order to facilitate such transitions. The pace for agroecological transition appears to get a better trajectory given the increasing land degradation, climate change, and the focus on sustainable development as a motivation for the change. For instance, France has been pursuing the development of agroecology through practice, research, and education since 2012 (Wezel & Bellon, Citation2018). Agroecology plays a significant role in French policy papers, such as those pertaining to organic farming, agroforestry, and the decrease in phytosanitary products (Lampkin et al., Citation2020). Similarly, farmers’ endeavors to develop and implement agroecological methods including biological control, cover crops, no-till, and organic practices have been supported by already-existing interest groups in France, such as the Economic and Environmental Interest Group program (Wezel & David, Citation2020). Agroecology is currently sidelined in the UK policy setting, according to Nicol (Citation2020). Overall, the European Union has not developed a coherent policy for sustainable agriculture or agroecological methods, and state action plans and political will on the subject are still fragmented and inconsistent.

On the other hand, Brazil created plans and policies that encourage agroecology and family farming, such as the Brazilian National Plan for Agroecology and Organic Production (PNPAO) in 2012, and approved a framework on right to food law (da Costa et al., Citation2017). The National Food Procurement Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), two effective programs that prioritize local family farmers and pay up to 30% higher prices to agroecological farmers for providing nutritious school lunches, helped to promote this. Furthermore, Nicaragua passed an Agroecology Law in 2011 that advocates for agroecology and organic farming (McCune, Citation2016; Schiller et al., Citation2023). Comparably, a new low-input farming approach that utilizes agroecology and food sovereignty is encouraged under Ecuador’s 2008 constitution, and the country approved the General Law of Food Sovereignty (LORSA) in 2010 to further stimulate the production and consumption of agroecological food (Sharma & Daugbjerg, Citation2021).

3. Lessons sub-Saharan Africa countries can learn from Cuba

Agroecology practices are Cuba’s answer to the 1993 geopolitical crisis that impacted conventional agriculture (Le Coq et al., Citation2020). Promoting ecological agriculture to champion social justice for food sovereignty has become a successful strategy for achieving food security for Cubans. The fall of the Soviet Union and the US trade embargo heralded a new era in the Cuban agricultural system, dramatically transitioning from conventional farming to agroecological practices (Vandermeer et al., Citation1993). The fall of the Soviet Union was a game-changer for Cuban agriculture, and the period following the Soviet fall, known as the Special Period, was a moment for the country to rethink its agriculture. At the time of the fall, Cuban agriculture modernized in the scripts of the Green Revolution, with more tractors per person and recording the second-highest grain yields in Latin America. For Cuban agriculture to prosper, it supported strong trade relations with the Soviet Union. Hence, the economic and food crisis immediately after the Soviet fall left a considerable burden for the state to find better alternatives. At this point, agroecology found a foothold, given that the fall also allowed Cuban scientists to voice their concerns about the externalities of high-input agriculture on the environment. Concerns over the environmental impact of industrial agriculture and the Cuban government’s move to prioritize local farmer knowledge and participation were pivotal to adopting agroecology (Rosset, Citation2000). The country still relies on food imports to meet the food demand gaps.

On how Cuba turned from a practice that relied heavily on US capital at the expense of marginalizing peasant farmers to a new model that majors in local participation, new measures had to be enacted. One of these reforms was property ownership, in which land held by the state was subdivided into Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPCs), which was considered effective in adopting new practices, unlike state farms. With all peasants being part of the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP), the peasants could then join the Credit and Service Cooperative (CCS) or the Agriculture Production Cooperatives (APC), where members of the former individually own land but employ collective marketing of their products, and the latter own land and other productive assets are collectively owned (Figueroa-Alfonso, Citation2023).

From Cuba’s experience, it did not take industrial agriculture to boost food production when the country’s food system was hamstrung by the Soviet fall and the US trade embargo hit. Still, it took outstanding leadership to manoeuvre through the crisis. Using a social process called Campesino-a-Campesino, Cuba transitioned from an industrial agriculture system to agroecological integration by relying on a social process that encouraged adoption (Rosset & Val, Citation2018). Nelson et al. (Citation2009), however, made the argument that Cuban farmers continue to value production maximization over adherence to an agroecological standard. Therefore, farmers may be open to returning to conventional agriculture if it proves politically and economically possible to do so, as agroecological farming is primarily seen as a practical option rather than an idealistic or ethical one. Other lessons drawn from the Cuban experience are that success can be achieved if some complementary policies and institutions support agroecology movements, given that the push for agroecology would be seen as a war against the industrial model of agriculture (Val, Citation2023). Lucantoni (Citation2020) demonstrated that following Cuba’s shift to agroecology, all four components of food security—availability, access, stability, and utilisation—improved. Positive effects were also noted in soil quality, environmental sustainability, and resilience. Furthermore, in order to control the production and preparation of food using organic methods, the national government of Cuba implemented the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS), emphasizing active involvement from both producers and consumers (Jones et al., Citation2022).

4. Conclusion and policy implications

There have been more calls for a paradigm shift in the design of modern agricultural systems due to the increasing pressures imposed by the world’s population, the looming effects of climate change on food production, the growing trend of volatile market prices of the major global primary crops, and the dearth of sustainability and resilience found in current commercial farming methods. If agroecology is expanded upon or intensified, it can yield numerous benefits. However, the success of scale-out requires a combination of complementing governmental policies rather than a single one. In this regard, agroecology can offer valuable perspectives and steer the planning, creation, and encouragement of the shift to sustainable agriculture and food systems. By segregating the ecological and socioeconomic restrictions on the farm, agroecological approaches can offer context-specific and viable solutions to problems facing farmers. Agroecology may offer valuable perspectives on crucial routes and direct the planning, advancement, and advocacy of the shift towards sustainable agriculture and food systems. Therefore, codesign living labs are required in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) to facilitate collaborative policy development, evaluation, and testing; innovations, such as novel production systems and food networks; and modern technologies, taking into account all relevant actors and stakeholders at various organizational levels.

Borrowing from Cuba and making agroecological practices work for countries in SSA calls for a dramatic shift that looks at the food system beyond just food security. A common justification used to support agroecological upscaling is the existence of supportive policies. Thus, mainstream agroecology is needed in budgetary allocations. Consequently, agroecological policies are needed to prioritize women and youth as drivers of policies. Efforts to transform rural livelihoods so that socio-economic realities are resolved by agricultural development would require a holistic agroecology approach. The question of the appropriate policies in the appropriate setting is crucial for a nation looking to embark on an agroecological transition, and it ought to be included in national strategies. First and foremost, nations must comprehend the wide range of policy options available. Then, they can pick up tips on what has worked and how beneficial the policy is from other nations. Stakeholders need to band together to get political support at the national and international levels in order to support the farms’ shift to agroecology and the expansion of additional bottom-up agroecology projects for farming and sustainable food systems. Furthermore, partnerships centred on market processes ought to be established in order to expand the revolutionary potential of agroecology into new domains. Lastly, they must comprehend the prerequisites for a successful policy, which are the components that enabled the adoption and effective scaling-up of agroecology principles. These components include the fundamentals pertaining to capacity, public finance, private costs and rewards, and norms.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: KOO, RJO and DCM; acquisition of literature: CLY and JBM; analysis and interpretation of literature: KOO, JBM, and MM; drafting of manuscript: KOO, MM, DCM, MOO and CLY; revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: KOO, CLY, MOO, RJO and MM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The researchers thank in advance the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kevin Okoth Ouko

Dr. Kevin Okoth Ouko is a Post Doctoral Research Fellow at African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS). He holds a PhD in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya and an MSc in Agricultural and Applied Economics from Egerton University, Kenya/University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Cherine Lando Yugi

Cherine Lando Yugi is a Master of Arts in Project Planning and Management student at Catholic University of Eastern Africa (CUEA), Kenya. Her research interests in include food security, gender and development and education.

Modock Odiwuor Oketch

Modock Odiwuor Oketch is Master of Science student in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya. Modock holds a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Economics of Egerton University, Kenya. He is currently a private consultant in food systems research and policy.

Jimmy Brian Mboya

Jimmy Brian Mboya is a Graduate Research Fellow at International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe). He is an MSc candidate in Fisheries and Aquaculture at Maseno University, Kenya. He is also a Research Intern at Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI). His areas of expertise and interest include sustainable aquaculture, fisheries, blue economy, use of insects as food and feed, climate-smart food production, nutrition, and climate change.

Robert John Ogola

Robert John Ogola is a PhD student at the University of Reading in UK. He holds a Master of Science in Climate Studies (Ecological and Agro-Ecological Systems) at Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands.

Mavindu Muthoka

Mavindu Muthoka is PhD student in Fisheries and Aquaculture under Potentials of Agro-Ecological Practices in East Africa with a Focus on Circular Water-Energy Nutrient Systems (PrAEctiCe) project at Maseno University, Kenya.

Dick Chune Midamba

Dick Chune Midamba is a PhD Candidate in Agricultural Economics at Maseno University, Kenya. His research interest includes technical efficiency, adoption of sustainable agricultural technologies, crop diversity, resource optimization for cash – food crop production and sustainable agriculture.

Notes

1 ABN is a regional network working with partner organisations and communities to develop culturally centred approaches to social and ecological problems in Africa through sharing experiences, co-developing methodologies and creating a united African voice on the continent on these issues. First conceived in 1996, ABN now has thirty-five partners across 12 African countries, and a Secretariat based in Thika, Kenya. ABN envisions “vibrant and resilient African communities rooted in their own biological, cultural, and spiritual diversity, governing their own lives and livelihoods, in harmony with healthy ecosystems”. ABN works with three interrelated thematic areas: Community Seed and Knowledge (CSK), Community Ecological Governance (CEG) and Youth, Culture and Biodiversity (YCB).

References

- Abegunde, A. A. (2017). Local communities’ belief in climate change in a rural region of Sub-Saharan Africa. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19(4), 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-016-9816-5

- ACB. (2023). An assessment of support for agroecology in South Africa’s policy landscape. African Centre for Biodiversity. https://acbio.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Assessment-for-AE-in-SA-report_fin_May2023.pdf

- Adamtey, N., Musyoka, M. W., Zundel, C., Cobo, J. G., Karanja, E., Fiaboe, K. K. M., Muriuki, A., Mucheru-Muna, M., Vanlauwe, B., Berset, E., Messmer, M. M., Gattinger, A., Bhullar, G. S., Cadisch, G., Fliessbach, A., Mäder, P., Niggli, U., & Foster, D. (2016). Productivity, profitability and partial nutrient balance in maize-based conventional and organic farming systems in Kenya. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 235, 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.10.001

- Altieri, M. A., & Nicholls, C. I. (2012). Agroecology scaling up for food sovereignty and resiliency. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, 11, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5449-2_1

- Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., & Montalba, R. (2017). Technological approaches to sustainable agriculture at a crossroads: An agroecological perspective. Sustainability, 9(3), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030349

- Anderson, C. R., & Maughan, C. (2021). “The Innovation Imperative”: The struggle over agroecology in the international food policy arena. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5 https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.619185

- Anderson, C. R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M. J., Kiss, C., & Pimbert, M. P. (2019). From transition to domains of transformation: Getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability, 11(19), 5272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195272

- Arora, N. K., & Mishra, I. (2022). Current scenario and future directions for sustainable development goal 2: A roadmap to zero hunger. Environmental Sustainability, 5(2), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-022-00235-8

- Bàrberi, P. (2019). Ecological weed management in sub-Saharan Africa: Prospects and implications on other agroecosystem services. Advances in Agronomy, 156, 219–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2019.01.009

- Bellwood-Howard, I., & Ripoll, S. (2020). Divergent understandings of agroecology in the era of the African Green Revolution. Outlook on Agriculture, 49(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727020930353

- Bendjebbar, P., & Fouilleux, E. (2022). Exploring national trajectories of organic agriculture in Africa. Comparing Benin and Uganda. Journal of Rural Studies, 89, 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.11.012

- Béné, C. (2022). Why the Great Food Transformation may not happen–A deep-dive into our food systems’ political economy, controversies and politics of evidence. World Development, 154, 105881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105881

- Bezner Kerr, R., Madsen, S., Stüber, M., Liebert, J., Enloe, S., Borghino, N., Parros, P., Mutyambai, D. M., Prudhon, M., & Wezel, A. (2021). Can agroecology improve food security and nutrition? A review. Global Food Security, 29, 100540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100540

- Bjornlund, V., Bjornlund, H., & Van Rooyen, A. F. (2020). Why agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa remains low compared to the rest of the world – A historical perspective. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 36(sup1), S20–S53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2020.1739512

- Boillat, S., Belmin, R., & Bottazzi, P. (2022). The agroecological transition in Senegal: transnational links and uneven empowerment. Agriculture and Human Values, 39(1), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10247-5

- Botchway, V. A., Sam, K. O., Karbo, N., Essegbey, G. O., Nutsukpo, D., Agyemang, K., … Partey, S. T. (2016). Climate-smart agricultural practices in Ghana. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/102186

- Bottazzi, P., & Boillat, S. (2021). Agroecological farmer movements and advocacy coalitions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Between de-politicization and re-politicization. In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Labour Studies (pp. 415–440). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71909-8_18

- Bottazzi, P., Boillat, S., Marfurt, F., & Seck, S. M. (2020). Channels of labour control in organic farming: Toward a just agroecological transition for Sub-Saharan Africa. Land, 9(6), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060205

- Castellanos-Navarrete, A., & Jansen, K. (2018). Is oil palm expansion a challenge to agroecology? Smallholders practising industrial farming in Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change, 18(1), 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12195

- Chitiyo, P., & Duram, L. A. (2019). Role of NGOs in addressing agricultural challenges through certified organic agriculture in developing regions: A Zimbabwe case study. J Sustain Dev Africa, 21(3), 138–157.

- Dahlin, A. S., & Rusinamhodzi, L. (2019). Yield and labor relations of sustainable intensification options for smallholder farmers in sub‐Saharan Africa. A meta‐analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 39(3), 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0575-1

- da Costa, M. B. B., Souza, M., Júnior, V. M., Comin, J. J., & Lovato, P. E. (2017). Agroecology development in Brazil between 1970 and 2015. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 41(3-4), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1285382

- De Giusti, G., Kristjanson, P., & Rufino, M. C. (2019). Agroforestry as a climate change mitigation practice in Smallholder Farming: Evidence from Kenya. Climatic Change, 153(3), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02390-0

- DeMarco, P. M. (2017). Rachel Carson’s environmental ethic–a guide for global systems decision making. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.03.058

- Dribe, M., Olsson, M., & Svensson, P. (2017). The agricultural revolution and the conditions of the rural poor, southern Sweden, 1750–1860. The Economic History Review, 70(2), 483–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12378

- El Bilali, H., Dambo, L., Bassole, I. H. N., Nanema, J., & Calabrese, G. (2022). Agroecology in Burkina Faso and Niger. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366228483_Agroecology_in_Burkina_Faso_and_Niger

- Ericksen, P. J. (2008). Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global Environmental Change, 18(1), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.09.002

- Ewert, F., Baatz, R., & Finger, R. (2023). Agroecology for a sustainable agriculture and food system: from local solutions to large-scale adoption. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 15(1), 351–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-102422-090105

- Falconnier, G. N., Cardinael, R., Corbeels, M., Baudron, F., Chivenge, P., Couëdel, A., Ripoche, A., Affholder, F., Naudin, K., Benaillon, E., Rusinamhodzi, L., Leroux, L., Vanlauwe, B., & Giller, K. E. (2023). The input reduction principle of Agroecology is wrong regarding mineral fertilizer use in sub-Saharan Africa. Outlook on Agriculture, 52(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/00307270231199795

- FAO. (2019). Constructing markets for agroecology - An analysis of diverse options for marketing products from agroecology. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. (2015). Regional Meeting on Agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa | FAO Regional Office for Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from http://www.fao.org/africa/events/detail-events/en/c/330741/.

- FAO. (2018). Definitions: Agroecology Knowledge Hub. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Figueroa-Alfonso, G. (2023). Agroecology and revolution: Agricultural policies on land, autonomy, and priority crops. Elem Sci Anth, 11(1) https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2022.00062

- Gama, J., & Millinga, M. L. (2016). Latest developments in organic Agriculture in Africa. The World of Organic Agriculture, 174.

- Gliessman, S. (2018). Scaling out and scaling up agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42(8), 841–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1481249

- González-Chang, M., Wratten, S. D., Shields, M. W., Costanza, R., Dainese, M., Gurr, G. M., Johnson, J., Karp, D. S., Ketelaar, J. W., Nboyine, J., Pretty, J., Rayl, R., Sandhu, H., Walker, M., & Zhou, W. (2020). Understanding the pathways from biodiversity to agro-ecological outcomes: A new, interactive approach. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 301, 107053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107053

- Iocola, I., Ciaccia, C., Colombo, L., Grard, B., Maurino, S., Wezel, A., & Canal, S. (2022). Agroecology research in Europe: Status and perspectives. Open Research Europe, 2(, 139. https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.15264.1

- Isgren, E. (2018). If the change is going to happen it’s not by us’: Exploring the role of NGOs in the politicization of Ugandan agriculture. Journal of Rural Studies, 63, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.07.010

- Isgren, E., & Ness, B. (2017). Agroecology to promote just sustainability transitions: Analysis of a civil society network in the Rwenzori Region, Western Uganda. Sustainability, 9(8), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081357

- Jaworski, M. (2014). Smallholders, cooperatives, and food sovereignty in Tanzania: why a nation of farmers cannot feed its people. https://library2.smu.ca/handle/01/26224

- Jones, S. K., Bergamini, N., Beggi, F., Lesueur, D., Vinceti, B., Bailey, A., DeClerck, F. A., Estrada-Carmona, N., Fadda, C., Hainzelin, E. M., Hunter, D., Kettle, C., Kihara, J., Jika, A. K. N., Pulleman, M., Remans, R., Termote, C., Fremout, T., Thomas, E., Verchot, L., & Quintero, M. (2022). Research strategies to catalyze agroecological transitions in low-and middle-income countries. Sustainability Science, 17(6), 2557–2577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01163-6

- Kanjanja, S. M., Mosha, D. B., & Haule, S. C. (2022). Determinants of implementing agroecological practices among smallholder farmers in Singida District, Tanzania. European Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences, 4(5), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejfood.2022.4.5.571

- Kansanga, M. M. (2017). Who you know and when you plough? Social capital and agricultural mechanization under the new green revolution in Ghana. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 15(6), 708–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1399515

- Karuga, J. G. (2022). Agroecological farming impacts livelihoods improvement to inform county government on the enactment of agroecology policy: a case study of Kiambu County, Central Kenya [Master’s thesis]. Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Kiyani, P., Andoh, J., Lee, Y., & Lee, D. K. (2017). Benefits and challenges of agroforestry adoption: a case of Musebeya sector, Nyamagabe District in southern province of Rwanda. Forest Science and Technology, 13(4), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2017.1392367

- Knorr, D., & Augustin, M. A. (2021). From value chains to food webs: The quest for lasting food systems. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 110, 812–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.037

- Kuo, H. J., & Peters, D. J. (2017). The socioeconomic geography of organic agriculture in the United States. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 41, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1359808

- Lampkin, N., Schwarz, G., & Bellon, S. (2020). Policies for agroecology in Europe, building on experiences in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. Landbauforsch. Journal of Sustainability Education Agricultural Sustainability, 70(2), 103–112. https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/dn063310.pdf

- Laske, E., & Michel, S. (2022). What contribution of Agroecology to job creation in sub-saharan africa? the case of horticulture in the Niayes, senegal. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 46(9), 1360–1385. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2022.2107595

- Le Coq, J. F., Sabourin, E., Bonin, M., Fréguin-Gresh, S., Marzin, J., Niederle, P., … Vásquez, L. (2020). Public policy support for agroecology in Latin America: Lessons and perspectives. Global Journal of Ecology, 5(1), 129–138. https://hal.science/hal-04433974/

- Lucantoni, D. (2020). Transition to agroecology for improved food security and better living conditions: A case study from a family farm in Pinar del Río, Cuba. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(9), 1124–1161. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1766635

- Lucantoni, D., Sy, M. R., Goïta, M., Veyret-Picot, M., Vicovaro, M., Bicksler, A., & Mottet, A. (2023). Evidence of the multidimensional performance of agroecology in Mali using tape. Agricultural Systems, 204, 103499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103499

- Maccari, M. (2022). Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS): a tool to improve the effectiveness of smallholders’ production.

- Manyanga, M., Pedzisa, T., & Hanyani-Mlambo, B. (2023). Adoption of agroecological intensification practices in Southern Africa: A scientific review. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2261838

- McCune, N. (2016). Family, territory, nation: post-neoliberal agroecological scaling in Nicaragua. Food Chain, 6(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.3362/2046-1887.2016.008

- McGreevy, S. R., Tamura, N., Kobayashi, M., Zollet, S., Hitaka, K., Nicholls, C. I., & Altieri, M. A. (2021). Amplifying agroecological farmer lighthouses in contested territories: navigating historical conditions and forming new clusters in Japan. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 699694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.699694

- Mekoya, A., Oosting, S. J., Fernandez-Rivera, S., & Van der Zijpp, A. J. (2008). Farmers’ perceptions about exotic multipurpose fodder trees and constraints to their adoption. Agroforestry Systems, 73(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-007-9102-5

- Méndez, V. E., Bacon, C. M., & Cohen, R. (2013). Agroecology as a transdisciplinary, participatory, and action-oriented approach. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 37(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.736926

- Migliorini, P., Gkisakis, V., Gonzalvez, V., Raigón, M., & Bàrberi, P. (2018). Agroecology in Mediterranean Europe: Genesis, states, and perspectives. Sustainability, 10(8), 2724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082724

- Mockshell, J., & Kamanda, J. (2018). Beyond the Agroecological and sustainable agricultural intensification debate: Is blended sustainability the way forward? International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1448047

- Moeller, N. I., Geck, M., Anderson, C., Barahona, C., Broudic, C., Cluset, R., Henriques, G., Leippert, F., Mills, D., Minhaj, A., Mueting-van Loon, A., de Raveschoot, S. P., & Frison, E. (2023). Measuring agroecology: Introducing a methodological framework and a community of practice approach. Elem Sci Anth, 11(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2023.00042

- Mugwanya, N. (2019). Why is agroecology a dead-end for Africa? Outlook on Agriculture, 48(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727019854761

- Namome, C. (2013). An economic analysis of certified organic smallholders in Limpopo Province, South Africa [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Pretoria.

- Nelson, E., Scott, S., Cukier, J., & Galán, Á. L. (2009). Institutionalizing Agroecology: Success and Challenges in Cuba. Agriculture and Human Values, 26(3), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9156-7

- Nelson, R., & Coe, R. (2013). Agroecological intensification of Smallholder Farming. In The Oxford Handbook of Food, Politics, and Society (pp. 105–128). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195397772.013.006

- Nicol, P. (2020). Pathways to scaling agroecology in the city region: scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep through community-led trade. Sustainability, 12(19), 7842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197842

- Nicolétis, É., Caron, P., El Solh, M., Cole, M., Fresco, L. O., Godoy-Faúndez, A., Kadleciková, M., Kennedy, E., Khan, M., Li, X., Mapfumo, P., Saeid Noori Naeini, M., Recine, E., Varghese, S., Yemefack, M., Zurayk, R., Lloyd Sinclair, F., Augustin, M. A., Bezner Kerr, R., … Zurayk, R. (2019). Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A report by the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/604473/1/604473.pdf

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., Mambulu, F. N., Kerr, R. B., Luginaah, I., & Lupafya, E. (2016). Agroecology and sustainable food systems: Participatory research to improve food security among HIV-affected households in northern Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 164, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.020

- Nyasimi, M. (2022). Review of Public Investments in the Agricultural Sector in Kenya and Modelled Returns on Investments over the Last Ten Years (Special Focus on Organic Farming).

- Nyéléni, M. (2015). Declaration of the international forum for agroecology. International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty. Consultado o, 18.

- Ofori, S. A., Cobbina, S. J., & Obiri, S. (2021). Climate change, land, water, and food security: Perspectives From Sub-Saharan Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 680924. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.680924

- Ogisi, O. D., & Begho, T. (2023). Adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the progress, barriers, gender differences and recommendations. Farming System, 1(2), 100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.farsys.2023.100019

- Ozor, N., & Nyambane, A. (2021). Policy and Institutional Landscape of Ecological Organic Agriculture in Rwanda. African Technology Policy Studies Network (ATPS) Technopolicy Brief No, 55.

- Paracchini, M. L., Justes, E., Wezel, A., Zingari, P. C., Kahane, R., Madsen, S., … Negri, T. (2020). Agroecological practices supporting food production and reducing food insecurity in developing countries. Study of scientific literature in 17 countries, EUR 30329 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, 2020. ISBN 978-92-76-21077-1. https://doi.org/10.2760/82475, JRC121570

- Parker, C., & Johnson, H. (2019). From food chains to food webs: regulating capitalist production and consumption in the food system. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 15(1), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042908

- Patel, R., Holt-Gimenez, E., & Shattuck, A. (2009). Ending Africa’s hunger. The Nation, 21, 17–22.

- Pereira, L., Wynberg, R., & Reis, Y. (2018). Agroecology: The future of sustainable farming? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 60(4), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2018.1472507

- Pretty, J. N. (1991). Farmers’ extension practice and technology adaptation: Agricultural revolution in 17–19th century Britain. Agriculture and Human Values, 8(1-2), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01579666

- Reader, G. T. (2023). Engineering to Adapt: Waste Not, Want Not. In Turbulence & Energy Laboratory Annual Conference. (pp. 1–53). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47237-4_1

- Rosset, P. M. (2000). Cuba: A successful case study of sustainable agriculture. In Hungry for profit: The agribusiness threat to farmers, food, and the environment (pp. 203–214). NYU Press.

- Rosset, P. M., & Val, V. (2018). The ‘Campesino a Campesino’Agroecology movement in Cuba: Food sovereignty and food as a common. In Routledge handbook of food as a common (pp. 251–265). Routledge.

- Schiller, K. J., Klerkx, L., Salazar Centeno, D. J., & Poortvliet, P. M. (2023). Developing the agroecological niche in Nicaragua: The roles of knowledge flows and intermediaries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(47), e2206195120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206195120

- Selvan, T., Panmei, L., Murasing, K. K., Guleria, V., Ramesh, K. R., Bhardwaj, D. R., Thakur, C. L., Kumar, D., Sharma, P., Digvijaysinh Umedsinh, R., Kayalvizhi, D., & Deshmukh, H. K. (2023). Circular economy in agriculture: Unleashing the potential of integrated organic farming for food security and sustainable development. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7, 1170380. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1170380

- Sharma, P., & Daugbjerg, C. (2021). Politicisation and coalition magnets in policy making: A comparative study of food sovereignty and agricultural reform in Nepal and Ecuador. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(5-6), 592–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1760716

- Shulla, K., & Leal-Filho, W. (2023). Achieving the UN Agenda 2030: Overall actions for the successful implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals before and after the 2030 deadline.

- Sinyangwe, S., Mwamakamba, S., & Nyoni, N. B. (2023). The contribution of agroecology to CSA. FARA Research Report, 7(70), 899–922. https://doi.org/10.59101/frr072370

- Soria-Lopez, A., Garcia-Perez, P., Carpena, M., Garcia-Oliveira, P., Otero, P., Fraga-Corral, M., Cao, H., Prieto, M. A., & Simal-Gandara, J. (2023). Challenges for future food systems: From the Green Revolution to food supply chains with a special focus on sustainability. Food Frontiers, 4(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/fft2.173

- Tapsoba, P. K., Aoudji, A. K., Kabore, M., Kestemont, M. P., Legay, C., & Achigan-Dako, E. G. (2020). Sociotechnical context and agroecological transition for smallholder farms in Benin and Burkina Faso. Agronomy, 10(9), 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10091447

- Uhunamure, S. E., Kom, Z., Shale, K., Nethengwe, N. S., & Steyn, J. (2021). Perceptions of smallholder farmers towards organic farming in South Africa. Agriculture, 11(11), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111157

- UNEP. (2015). Uncovering Pathways Towards an Inclusive Green Economy. A Summary for Leaders. https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/uncovering_pathways_towards_an_inclusive_green_economy_a_summary_for_leaders-2015ige_narrative_summary_web.pdf.pdf#page=14

- Val, V. (2023). To do, know, and be. First account of Cuban agroecology. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 50(3), 809–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2128778

- Valenzuela, H. (2016). Agroecology: A global paradigm to challenge mainstream industrial agriculture. Horticulturae, 2(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae2010002

- van Rheenen, T., Obirth-Opareh, N., Essegbey, G. O., Kolavalli, S., Ferguson, J., Boadu, P., & Chiang, C. (2012). Agricultural research in Ghana: An IFPRI-STEPRI report. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Vandermeer, J., Carney, J., Gersper, P., Perfecto, I., & Rosset, P. (1993). Cuba and the dilemma of modern agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 10(3), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02217832

- Wei, C. (2020). Agroecology, information and communications technology, and smallholders’ food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55(8), 1194–1208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620912784

- Wezel, A., & David, C. (2020). Policies for agroecology in France: implementation and impact in practice, research and education. Landbauforschung-Journal of Sustainable and Organic Agricultural Systems, 70(2), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.3220/LBF1608660604000

- Wezel, A., & Bellon, S. (2018). Mapping agroecology in Europe. New developments and applications. Sustainability, 10(8), 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082751

- Wezel, A., Herren, B. G., Kerr, R. B., Barrios, E., Gonçalves, A. L. R., & Sinclair, F. (2020). Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 40(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-020-00646-z

- Wittman, H. (2011). Food sovereignty: a new rights framework for food and nature? Environment and Society, 2(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2011.020106

- Zenda, M., & Rudolph, M. (2024). A systematic review of agroecology strategies for adapting to climate change impacts on smallholder crop farmers’ livelihoods in South Africa. Climate, 12(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12030033