Abstract

Global movements toward smart cities are expanding – the concept is anticipated to address a wide range of urbanization-related issues. Over the past decade, the concept of ‘smart tourism destination’ has gained popularity as a way to incorporate smart city principles into the tourism industry. More recent studies, however, have revealed that there is frequently a disconnection between the execution of smart city and tourism strategies on a local level, as the two have distinct priorities. The former focuses on the resident’s quality of life, while the latter concerns the visitor’s experience. As a result, the two objectives are currently integrated by a new paradigm dubbed ‘smart tourism city’, which also serves as the study’s vantage point. This article aims to investigate Jakarta’s potential as a smart tourism city. Besides serving as the capital city and being recognized as an urban destination, Jakarta is also a city pioneer for smart city development in Indonesia. To achieve the proposed objectives, this paper used qualitative methods. Data were collected through primary data using a dataset for observation checklist, followed by Focus Groups Discussions (FGD) with stakeholders to ensure the validity of the data and secondary data through desk study. Qualitative data was quantified to assess the sample district’s readiness, with points assigned to responses based on FGD, observation, and secondary sources. Four attributes of a smart tourism city—attractiveness, accessibility, digitalization readiness, and sustainability—are modified and applied in the observation and secondary data analysis of 14 Jakarta districts. The findings indicated that six districts have the most potential to be the pilot for smart tourism city development. It also revealed that while Jakarta has potential and strengths in two aspects, attractiveness and accessibility, the government must advance its digitalization and sustainability-related factors in order to construct a smart tourism city.

SUBJECTS:

1. Introduction

The idea of smart tourism destinations has gained traction globally, with coordinated initiatives in Asia and Europe. While some countries prioritize open data and smart governance, others invest substantially in technology infrastructure to support smart tourism (Gretzel et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2020). Smart tourism, an evolving subset of the smart city concept, explores how advancements in Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) contribute to sustainable tourist experiences and destinations (Lamsfus et al., Citation2015; Kelly et al., Citation1999). The integration of technology allows destinations to attract more tourists and compete effectively. This integration of smart tourism and smart cities is envisioned as a sustainable approach to urban tourism, addressing issues such as overcrowding and urban stress (Gelbman, Citation2020). The relationship between smart tourism and smart cities is reciprocal, as smart cities inspire smart tourism, and the latter depends on the infrastructure of smart cities, strengthening connections between subsystems (Liu & Liu, Citation2016).

As many cities have tapped into their tourism competitiveness by creating a smart tourism ecosystem based on existing smart city infrastructures, these advancements in tourism have stimulated the notion of creating smart tourism destinations (Lee et al., Citation2020). Some questions then arise. Is it accurate to say that combining tourism with smart cities makes them smarter? Are smart tourism experiences guaranteed for those visiting a smart city? Unfortunately, despite the fact that only a few studies (Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2023, in Romão et al., Citation2018) have looked at the tourism component of smart cities, those that have been conducted show that, despite the connection between the origin and characteristics of the smart city and smart destination, there is often a disconnection between these two strategies on a local scale (Soares et al., Citation2021).

The term ‘smart tourism city,’ referring to the convergence of smart city and smart tourism, has gained attention from academics and stakeholders in the tourism sector (Gretzel & Koo, Citation2021; Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2023; Lee et al., Citation2020). According to Lee et al. (Citation2020), a smart tourism city is a cutting-edge tourist destination that ensures sustainable development, promoting and enhancing visitors’ interaction with experiences at the destination, and ultimately improving the quality of life for locals. Using smart technology to manage the mix of work, leisure, and transportation activities that overlap in urban settings is a crucial way to enhance the quality of life for both tourists and locals (Gretzel & Koo, Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2020).

As the capital city of Indonesia and the epicenter of government, politics, and business, Jakarta has become a magnet for both international and domestic travelers. The city is currently undergoing significant infrastructure upgrades to establish itself as a sustainable and attractive destination. With the recent advancements in public transportation systems like MRT and LRT, Transit Oriented Development (TOD) areas, and other unique facilities, Jakarta has emerged as a hotspot for social media enthusiasts and visitors alike. Understanding the various facets of urban tourism is crucial, given the diverse expectations of tourists, whether they are visiting for leisure, conventions, or business purposes (Giriwati et al., Citation2013).

In addition to its existing attractions, Jakarta stands out as a pioneer in the development of smart cities in Indonesia. The city has consistently worked towards sustainable smart cities, earning the title of the nation’s smartest city (Chowdhury, Citation2016). The Indonesian government has actively pushed for smart city development since 2012, evident in the establishment of the Smart City Pillars as part of Indonesia’s Smart Cities (Supangkat et al., Citation2020). Notably, ‘smart branding,’ one of the six pillars, correlates with tourism-related features, highlighting Jakarta’s position as both a smart city and a popular urban destination.

Despite its significance in Indonesia’s smart city framework, smart tourism remains an underexplored concept, particularly in Jakarta, which serves as the nation’s smartest city and a popular urban destination. Previous studies have predominantly focused on assessing Jakarta as a smart city (Mahesa et al., Citation2019; Sangaji et al., Citation2021), encompassing the adoption of smart city applications (Zhu & Alamsyah, Citation2022), smart mobility (Mukti & Prambudia, Citation2018), smart governance (Mutiara et al., Citation2017), and smart people (Supangkat et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, investigations into the implementation of smart tourism in Jakarta have also been confined to the utilization of ICT within specific attractions and institutions only (Levyta et al., Citation2022; Lily Anita et al., Citation2021; Widodo & Dasiah, Citation2021). This aligns with earlier research from other countries, asserting that relatively few studies have considered tourism as a component in smart cities (Gretzel & Koo, Citation2021; Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2023). Thus, it requires cross-disciplinary research methodologies to provide the necessary insights for connecting the realms of smart cities and smart touris (Gretzel & Koo, Citation2021).

Departing from this background, the focus shifts to Jakarta’s potential as a smart tourism city. This paper aims to evaluate four crucial characteristics—attraction, accessibility, digitalization readiness, and sustainability—in 14 districts of Jakarta. Analyzing these factors is vital for Jakarta’s development as a smart city and smart destination, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the real impact of smart discourse. This study holds significant theoretical importance in shedding light on the unexplored intersection of smart city development and tourism, with Jakarta as the focal point. Despite the city’s recognition as the nation’s smartest city, the concept of smart tourism remains largely unexplored in the existing literature. By adopting a comprehensive stance and assessing the smart discourse’s impact on Jakarta’s evolution into a smart tourism city, this study anticipates offering valuable insights to academics, policy-makers, and stakeholders not only in Indonesia but also in other nations grappling with similar transitions.

2. Smart tourism city

2.1. Tourism positioning in the smart city context

The advancement of information technology and the need for sustainability have given rise to the concept of smart technology, also known as smartness. The concept is primarily based on information technologies that combine hardware, software, and network technologies. It offers real-time awareness of the real world and advanced analytics to support people in choosing options. With greater intelligence and actions, these smart technologies will optimize business operations and performance, spur innovation and increase competitiveness while assuring sustainable growth (Gajdošík, Citation2018). The focus is on “blurring the lines between the physical and the digital and on fostering technology integration” (Gretzel et al., Citation2015, p.179). For several decades, the smart concept has been applied on various scale (e.g., smart factory and smart home), until it has been applied to larger scales like cities, which also called as smart city. Given that so many cities today are moving toward this type of urban development, the concept of smart city is no longer novel in academia or policymaking (Chan et al., Citation2019).

The emergence of the smart city concept is indeed regarded as the most pervasive manifestation of the fourth industrial revolution in urban environments as cities and governments continue to invest heavily in digitalization to address a variety of urban issues (Andres Coca-Stefaniak & Seisdedos, Citation2020). The idea focused on how information and communication technologies (ICTs) are being developed, evolved, and integrated into every facet of sustainable urban development in the face of ongoing urbanization. Despite numerous conceptual frameworks exist to demonstrate and synthesize the multiple definitions of the smart city concept, the following quotation from Caragliu et al. (Citation2011, p.71) explain the notion in a straightforward but comprehensive way: “A city is smart when investments in human and social capital and traditional (transport) and modern (ICT) communication infrastructure fuel sustainable economic growth and a high quality of life, with a wise management of natural resources, through participatory governance”. Another pioneering study that recognizes the all-encompassing characteristics of the smart city concept is The Smart City Wheel, created by Cohen (Citation2013). There are six aspects of smartness in cities: smart governance, smart environment, smart mobility, smart economy, smart people, and smart living. As the framework remains debatably relevant today, there are many attempts to renew, adopt and adapt it, particularly regarding the measurement of each aspects. Nonetheless, smart cities have been recognized up to this point as the solution to improve quality of life and enable better governance in cities, despite their fuzziness, difficulties, and controversy (Andres Coca-Stefaniak & Seisdedos, Citation2020).

As the smartness has been considered the magic bullet to solving problems of cities, scholars have adopted the smart city concept and proposed ‘smart tourism’ in order to improve the tourist’s experience and the resident’s quality of life (Buhalis & Amaranggana, Citation2015). Smart tourism is essentially the application of smart technologies in tourism sector, particularly in utilizing principles, infrastructure and facilities of smart cities in tourist destinations (Moura & de Abreu e Silva Citation2021). The connected, informed, and engaged traveler is actively interacting with the destination, co-creating tourism products, and adding value that can be shared by all. As a result, smart technology implementation in tourism destinations has become crucial (Boes et al., Citation2016). As Gretzel et al. (Citation2015, p.181) explained the definition of smart tourism:

Smart tourism is the type of tourism supported by integrated efforts at a destination to collect and aggregate/harness data derived from physical infrastructure, social connections, government/organizational sources, and human bodies/minds in combination with the use of advanced technologies to transform that data into on-site experiences and business value propositions with a clear focus on efficiency, sustainability, and experience enrichment.

While further studies continue to explore the aspects of digital technology in smart cities and smart tourism destinations, there are some remaining, untackled questions about the other aspects. Andres Coca-Stefaniak and Seisdedos (Citation2020) criticized the existing smart tourism destination concepts, which “traditionally favored technology-focused”, and suggested that scholars need to move towards a more “human-centered” smart tourism destination. They further stated that, “visionary tourism cities will adopt a new strategic positioning that revolves around urban sustainability as a holistic paradigm, which will lead to a new generation of smart tourism destinations – the smart tourism city. It is no doubt that the development of smart tourism can strengthen smart city, and vice versa (Andres Coca-Stefaniak & Seisdedos, Citation2020; Jasrotia, Citation2018; Liu & Liu, Citation2016).

2.2. The duality of smart tourism destination and smart tourism city

Building on the aforementioned principles, the concept of smart tourism destination or smart destination, is developed to adapt the smart city concept into a tourism destination. It is unsurprising that smart cities’ principles are applied to tourist destinations, given the density of tourism information and the significant dependency arising from ICTs. The concept of smart tourism is mainly underpinned by smart cities, namely the use and integration of ICT and stakeholders in resource management – in this case, destinations – to achieve sustainable development and improve quality of life. However, the difference lies in the focus of the two. Unlike smart cities that focus on their residents, smart destinations focus more on the visitors (Gretzel and Koo 2021; Ortega & Malcolm, Citation2020). Therefore, the data obtained and analyzed in the context of a smart destination intends to improve the quality of the tourist experience by prioritizing the integration of all stakeholders to achieve a sustainable destination economically, environmentally and socially.

More recent study, however, has revealed that there is frequently a gap on a local scale between smart city and tourism plans – regardless of the origin and characteristics of the smart city and smart destination. Several researches indicate that a minimal number of smart cities have taken tourism into account when establishing various indicator systems and rankings for smart cities (Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2021). This aligns with the findings of a study by Sun et al. (Citation2022), which highlighted the absence of a comprehensive development framework as the primary obstacle to the advancement of smart tourism in Hong Kong, despite the city’s advanced implementation of its smart city strategy.

Other studies also showed that the smart city projects have generated a vast amount of data, but there is a lack of integration between the data collected from smart sensors and the information needed for tourism purposes (Gretzel et al., Citation2015). Tourist-specific data, such as crowd density at popular attractions or preferences gathered from mobile apps, is not effectively utilized to enhance the overall tourism experience. A study by Pribadi et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that the smart city branding and promotional efforts do not sufficiently highlight the innovative aspects that could enhance the tourism experience. The disconnect between the smart city narrative and the promotion of tourism offerings leaves tourists unaware of the city’s technological advancements that could positively impact their stay.

The smart city projects have generated a vast amount of data, but there is a lack of integration between the data collected from smart sensors and the information needed for tourism purposes. La Rocca (Citation2014) stated that the focus on smart urban solutions for tourism appears to be centered on the abundance of applications designed to improve the utilization of specific resources or, less frequently, urban mobility systems. Furthermore, tourist-specific data, such as crowd density at popular attractions or preferences gathered from mobile apps, is not effectively utilized to enhance the overall tourism experience. A study by Koo et al. (Citation2013) demonstrated that South Korea, as one of the smartest city, which has gained its reputation for its technological advancement and a popular tourist destination, still less adequate in meeting specific needs and expectations of tourists. One of the gap is related to the access of real-time information that tailored to tourists’ preferences.

Deviating from those concerns, a number of authors (e.g. Chung et al., Citation2021; Gretzel & Koo Citation2021; Soares et al., Citation2021) promote the Smart Tourism City concept as a means of managing the mix of work, leisure, and mobility activities that coexist in urban settings. These authors regarded smart tourism city as the tenets of both smart city and smart destination that are combined in this new paradigm of governance. Smart tourism city is then defined as “an innovative tourist destination that guarantees sustainable development that facilitates and enhances visitors’ interaction with experiences at the destination and improves the residents’ quality of life” (Lee et al., Citation2020, p.2).

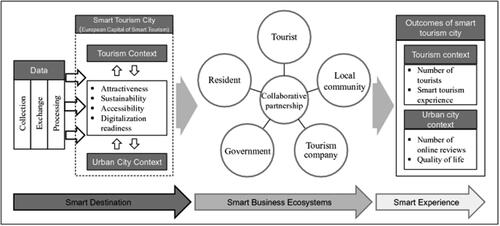

Chung et al. (Citation2021) modified the smart tourism framework of Gretzel et al. (Citation2015) and proposed three components of smart tourism cities: smart destination, smart experience and smart business (as seen in ). Smart destination entails smart tourism experiences that offer visitors better communication and interactions in cities, allowing them to develop closer relationships not only with residents but also with local businesses, the local government, and city attractions. The emphasis of smartness in smart destinations is to integrate tourism stakeholders in order to get easy access to tourist information, attractions, available packages, transportation to attractions, packages, and amenities (Buhalis & Amaranggana, Citation2015; Hunter, Citation2021), which uncovered by the smartness aspect in city management (Albino et al., Citation2015). The second component, smart business, refers to a dynamically networked, complex business ecosystem with a wide range of players working together to exchange and co-create tourist resources (Lee et al., Citation2020). When all the parts are considered, it is clear that smart destinations give their citizens access to resources, mobility, and a sustainable quality of life. They also facilitate tourism with integrated smart environments, which improves the experience of visitors. Having stated that, smart destinations and business ecosystem are the foundation of smart experiences, in which modern ICTs have made it a memorable experience for both visitors and locals.

Shafiee et al. (Citation2019) argue that ICT plays a significant role in the development of sustainable tourism, and sustainability has become a phenomenon in smart tourism destinations. As such, smart tourism destinations must concentrate their efforts on environmental, economic, social, and technical initiatives with strong government backing to enhance the quality of life for visitors as well as locals, manage natural and cultural resources, and bring together political, social, economic, and environmental goals. In order to maintain a harmonious coexistence between tourism and its ecosystem, the study by Gündüz and Atak (Citation2023) also mentions the significance of educating visitors and local communities about the preservation of natural resources and cultural heritage. This is done to balance economic growth with the preservation of culture and the environment.

2.3. Smart tourism city indicators

As this study only focuses on the identification of smart destination in a smart tourism city framework that has been discussed in the literature section, the following part will provide the indicators of smart destination. Although several studies have attempted to conceive the idea of a smart tourism city, it has been discovered that very few have attempted to operationalize the idea into a comprehensive set of quantifiable metrics. Therefore, the measurement used in this study was drawn from past studies.

Regarding the smart destination, Chung et al. (Citation2021) identifies the building blocks of smart destination, comprises of four components—attractiveness, sustainability, accessibility, and digitalization readiness, which were modified from the EU Smart Tourism Capital’s Smart Tourism Evaluation Indicator (2022). Chung’s smart tourism city indicators also served as the foundation for the creation of this study’s measurement. Despite the fact that the index already includes indicators for each variable, the model seems to simplify the idea of smart tourism, particularly with regard to the attractiveness variable. As a result, this study also refers to the 6 A framework put forth by Buhalis (Citation2000) or more known as (SA)6, which was later adapted by Tran et al. (Citation2017, pp. 190-214) to the smart destination concept. The framework claims that a component of successful tourist destinations consists of not only smart attractions, amenities, and accessibility but also smart available packages, ancillary services, and activities. With the exception of accessibility, which is treated as a single variable, all of these indicators are also considered when measuring attractiveness in this study.

Furthermore, the importance of cultural heritage and creativity, which is regarded as a crucial element for the development of smart tourism destinations by the EU Smart Tourism Capital (Citation2022), is not included in either conceptual model. By analyzing the best smart tourist capitals in the EU each year, the European Union (EU) has been working on a program to promote promotion and marketing efforts in smart tourism destinations. However, when it comes to the idea of smart tourism destination, the EU evaluation indices only take tourists’ perspectives into account and do not consider the different social problems that locals face as a result of tourism. Therefore, Chung modified the EU framework by replacing the ‘cultural heritage and creativity’ component with attractiveness that indicates the utilization of technology in attractions. However, according to Sotiriadis (Citation2022), the smart tourism city concept is derived from smart city concept which is aimed to increase the quality of tourists’ experiences as well as the residents’ lives through smart technology in which a special emphasis on cultural heritage and creativity. Therefore, this study includes this aspect as an indicator of the attractiveness.

2.3.1. Attractiveness

Attractiveness refers to the degree to which physical and intangible tourist attractions are made available via the Internet or ICTs. As shown in , it consists of five indicators: smart attraction, smart amenities, smart available packages, smart ancillaries, and cultural heritage and creativity. Referring to early studies, smart attractions should have certain basic ICT facilities to provide better experiences for visitors. These facilities include info kiosk, audio and visual guides, and sensors for crowd monitoring or other purposes (Gajdošík, Citation2018). Furthermore, smart attractions should be easy to discover online and employ ICTs for promotion, including social media and websites as its digital promotion tools (Tran et al., Citation2017, 190-214).

Table 4. Study area.

Table 1. Indicators of attractiveness.

Other than the use of ICTs in attractions, it should be incorporated into all activities available at the destination. In terms of available packages, smartness can be applied in the form of sustainable packages that held in a collaborative way and also offered on a multi-lingual application that gives information access for both domestic and international visitors. In order to help visitors obtaining the latest information on tourism-related events and development more conveniently, destinations should also create mobile applications (EU Smart Tourism Capital Citation2022). Smart available packages can also be delivered at a destination via chip-based smart tourist or destination cards, which provide access to cultural and recreational attractions, integrate free services for public transportation and offer various discounts in souvenir shops (Gajdošík, Citation2018; Tran et al., Citation2017, 190–214).

2.3.2. Accessibility

Accessibility refers to the extent to which travel-related information and transportation services can be accessed both physically and virtually. A smart location must be physically and digitally accessible to all visitors, regardless of their socio-economic status, cultural background, or any physical impairment (EU Smart Tourism Capital Citation2022). Based on that basis, accessibility component is divided into three indicators: smart convenience or digital mobility, physical mobility, and barrier-free design.

The first indicator, smart convenience, comprises of ICT-based channels where tourists get information regarding a destination, provision of local tourism official website that contains useful tourism information, and availability of destination mobile application (Chung et al., Citation2021; Tran et al., Citation2017, 190–214). The discussion of digital mobility, nonetheless, will be covered under the attractiveness as some of these indicators overlap with those for attractiveness. As seen in , the second indicator, physical mobility, is related to how adequate the public transport within a destination. The availability of all forms of public transportation, the distance between transit hubs, and traffic management systems are a few measures to examine while evaluating this aspect. The last indicator measures whether a destination is equipped with barrier free design facilities as mobility also includes access for disabled tourists.

Table 2. Indicators of accessibility.

2.3.3. Digitalization readiness

Digital tourism refers to providing cutting-edge travel and hospitality information, products, services, locations, and experiences that are tailored to the demands of the consumer. It entails offering digital information about travel destinations, tourist attractions, and travel deals, as well as digital accessibility to attractions and accommodation and information on public transportation (European Capital of Smart Tourism, Citation2022). A measure of infrastructure and data openness that can deliver top-notch, smart tourist information based on cutting-edge ICTs is known as digitalization readiness. As shown in , digitalization consists of smart platform, digital infrastructure, and smart service technologies. While smart platform indicates digital payment provided at the destination, digital infrastructure refers to the availability of free wi-fi connection in public spots (i.e., airports, bus station, train stations, attractions, city centers, and tourism offices) and smart service technology measures other digital infrastructures that can enhance tourist experience when visiting the destination. As the emergence of smart tourism as the result of utilization of digital technology and digital platform, then digital readiness in tourism destination become the essential factor in creating smart tourism (Pranita et al., Citation2023; Pranita & Kesa, Citation2021).

Table 3. Indicators of digitalization and sustainability.

2.3.4. Sustainability

Sustainability is the level of a smart tourism city’s ability to support long-term social, economic, and environmental development. It consists of urban resilience, tourism safety, creative and innovative tourism, and life and tourism settings (European Capital of Smart Tourism, Citation2022). Some guiding questions include: what options does a city have to maintain a healthy balance between economic and socio-cultural development and the preservation and enhancement of the natural world and its resources? Being sustainable extends further: are there initiatives to lessen the seasonality of tourism and involve the neighborhood? How can cities, as tourist attractions, support local employment and economic diversification? Being sustainable, then, means including the local community and reducing seasonality in addition to managing and protecting city’s natural resources (European Capital of Smart Tourism, Citation2022).

3. Materials and method

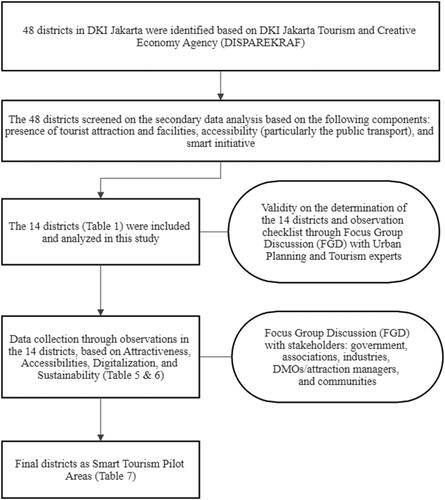

As depicted in , the data collection and analysis for this study occurred in five distinct stages. A combination of primary and secondary data sources was employed in this study. The primary data collection methods encompassed participant observation and Focus Group Discussions (FGD), while secondary data was obtained through online sources and policy documents. This strategic approach aligns with a broader trend observed in contemporary studies assessing city readiness across diverse contexts. Noteworthy examples include the work of Ariansyah et al. (Citation2024), where FGD and surveys were employed to evaluate big data readiness in the public sector. Similarly, Manggalou et al. (Citation2023) constructed a readiness dataset through interviews, observation, and documentation studies, while Noori et al. (Citation2020) undertook desk research, statistical analysis, and surveys. Mahesa et al. (Citation2019) adopted a qualitative approach, combining interviews with cross-referencing secondary sources for a comprehensive readiness assessment dataset focused on sustainable smart cities in Indonesia. While Arief et al. (Citation2020) conducted both observation and interview for the readiness assessment of smart island and suggested that a future study should also conduct an FGD to minimize bias. The convergence of methodologies in our study with these diverse approaches in the literature contributes collectively to the evolving academic discourse on city readiness assessments.

As seen in the figure above, the first step of our research process was selecting the study area. The selection of our study area was guided by a policy document from the Jakarta Tourism and Creative Economy Agency (Disparekraf), outlining Jakarta’s development as an urban destination. This document identified 48 districts as potential tourism hubs, establishing the geographical focus for our study. We proceeded to conduct an extensive evaluation of all districts using secondary data assessment through online sources, utilizing Buhalis’ (2000) 6 A framework. This framework emphasized factors such as the existence of attractions, accessibility, amenities, and smart initiatives – encompassing activities, available packages, and ancillaries within each district. Following this assessment, we identified 14 areas (as indicated in ) to serve as the focus of our study.

Subsequently, the next step entailed primary data collection through on-site observations in the 14 selected districts. In this study, where our emphasis lies in assessing the city as a smart destination, specifically concentrating on the recent practical and tangible provision of infrastructure and facilities. Observation was deemed the most suitable approach, as it involves directly observing the object of our research in real-time, providing an accurate representation of the current state of affairs in the field. This data collection was conducted during October and November 2022, with researchers visiting all selected districts to conduct on-site observations and assessments using a predefined checklist that encompassed four key components: Attractiveness, Accessibilities, Digitalization, and Sustainability.

After obtaining data derived from field observations, the researcher validated the findings through expert judgment methodology, which is conducted through a series of five Focus Group Discussions (FGD). Expert judgment is a judgment provided based upon expertise provided by any group or individual with specialized education, knowledge, experience, skill or training, in an application area, knowledge area, discipline, or industry, as appropriate for the activity performed (Szwed, Citation2016). The expert judgement process is focussed on discussing uncertainty, understanding the impacts across the research object, and to introduce some additional concepts (Ashcroft et al., Citation2016). This activity involving a total of 45 stakeholders actively engaged in activities and developments around the selected districts. The participants included 10 government representatives, comprising 5 from the Jakarta Tourism and Creative Economy Agency (Disparekraf) and 5 from each municipal; 14 attraction managers, 8 representatives from tourism associations, 4 from the business sector, 5 from civil society organizations and 4 representatives from the local community. In this case, we use this methodology as we are aware that our observation data requires subjective input from knowledgeable individuals. Therefore, we purposively selected the participants based on their expertise, knowledge, and experience in the relevant subject matter. This choice was made to harness the collective opinions of multiple experts and stakeholders, forming a comprehensive assessment.

Following the analysis of qualitative data obtained from observation and focus group discussions (FGDs), the data underwent quantification to evaluate the readiness of the selected district, mirroring approaches used in previous studies examining city readiness (Mahesa et al., Citation2019; Yin, Citation2014). In this case, points were assigned to responses obtained from the discussion. The values 0 and 1 indicate the absence or presence, respectively, of each indicator based on data collected through FGD, observation, and secondary sources. For example (refer to ), one of the readiness indicators is ‘the presence of attractions on Google Maps.’ Our desk study findings indicate that the attractions considered in this study within the Kebayoran Lama District are present on Google Maps, and this was confirmed in the FGD. Consequently, Kebayoran Lama is assigned a ‘1’ point under this specific indicator. If there is any mismatch between the data obtained from observation and secondary resources with the FGD, then a ‘0’ point will be assigned.

Table 5. Secondary dataset.

4. Findings

This section is structured into three subsections. Initially, an overview of readiness assessment datasets concerning 14 districts in Jakarta is provided, drawing upon secondary data collection. Subsequently, the primary dataset findings are discussed. Finally, informed by both secondary and primary dataset outcomes, six districts are proposed as potential pilot study areas for Jakarta’s smart tourism initiatives.

4.1. Secondary dataset

As can be seen in , there are 37 indicators under four components of Smart Tourism City that was used for the readiness assessment of each district. In terms of the attractiveness dimension, the available tourist packages held collaboratively is sub-component that is rarely owned by the districts. Nonetheless, there are two districts with the highest score and have all sub-components in the attractiveness aspect: Menteng and Gambir, while on the contrary, PuloGadung is the district with the lowest score.

For the accessibility dimension, the indicators represent to what extent the districts are disability-friendly by analyzing the hotel access in the district. There are three data sources: Traveloka, which is an Indonesia’s famous OTA (Online Travel Agent), Booking.com, and Google Maps. Interestingly, whereas most districts shows that they already have hotels that provide facilities for persons with disabilities, their attractions have not provided information regarding services for people with disabilities wither on websites or social media accounts.

Regarding the third dimension, digitalization, there are two indicators. The first one is the availability of mobile application that provide information on the free wifi connections for public. In this case, all the districts are covered on the Jakarta government’sapplication, JAKI, which show the name of every spot that has free wifi in each district. The second indicator, the use of mobile applications to guide tourists while they are in the district, is rarely present in the districts. Only six districts have developed their own mobile application: Cilandak, Tanah Abang, Pantai Indah Kapuk, Sawah Besar, Menteng, and Grogol Petamburan.

It can be seen from the dataset that for the last dimension, sustainability, all districts are already in the coverage area for mobile applications that track and provide waste bankservices in Jakarta, such as Waste4Change and Octopus. The entire districts have also been covered for information related to environmental indicators, in this case is measurements of the district’s pollution, which can be seen on the Jakarta government’s JAKI application.

4.2. Primary dataset

As displayed in , the value of each district’s attractiveness varies quite a bit, with the use of technology at the Tourist Information Centre (TIC)being the least sub-component owned by the district. The reason for this is because many areas lack TICs. Only one of the 14 districts—SawahBesar and Menteng, both of which have TICs in Jakarta—have all four components. Mampang Prapatan and Grogol Petamburan, which lack the four attraction factors, have the lowest scores.

Table 6. Primary dataset.

According to the findings of primary data, the majority of districts nearly meet all accessibility requirements. In this instance, only PuloGadung, Grogol Petamburan get the lowest value since they lack one accessibility component. While the latter district does not have suitable access for people with disabilities, the former district does offer limited public transportation within the area, particularly towards the Equestrian Park attraction, which can only be reached by private cars.

Digital services and ICT infrastructure are the sub-components of the digitalization aspect that most districts own the least of. Only three districts have all the sub components of digitalization, which are Cilandak, Tanah Abang and Menteng. The dataset on digitalization are displayed in .

4.3. Six districts as smart tourism pilot areas

According to the findings of this study, six districts are most ready to serve as pilot areas to support Jakarta as a smart tourism city. As shown in , Menteng has the best overall value because it contains all the required components for sustainability, digitalization, accessibility, and attractiveness. Gambir, Sawah Besar, Kebayoran Baru, Cilandak, and Kota Tua are the next-highest scoring areas, respectively. Regarding the score of each component, the best district for attractiveness are Menteng and Gambir; while for digitalization are Menteng, Cilandak, Gambir and Kebayoran Baru. As for accessibility and sustainability, most districts in Jakarta have almost met all the sub components.

Table 7. Smart tourism pilot areas.

5. Discussion

This part discusses the comparison of four components of smart tourism city in six districts that functioned as the smart tourism pilot areas.

5.1. Attractiveness

In the past year, various efforts to integrate modernity with historical and cultural heritage have been evident in the six districts. Several attractions were revitalized to make them more modern without losing the cultural and historical elements attached. These attractions include newly renovated art and cultural spaces such as Sarinah and Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), and public spaces like Lapangan Banteng and Petak Enam. Even after being revitalized, they have succeeded in becoming new tourist attractions in Jakarta. The previously abandoned park, Taman Marta Tiahahu, was also converted into a literacy park where visitors and residents could have a comfortable place to read, see photo exhibitions, and play.

Another attempt at integration occurred through renovations in some parts of the attractions. For instance, Taman Menteng was renovated by creating a mural on the volleyball court involving a number of local artists. It has also become an art exhibition venue for the Jakarta Biennale. The architecture of the National Monument and Istiqlal Mosque was restored to make them more welcoming for visitors without losing any of the cultural and historical components that make them unique. Efforts to integrate modernity with historical and cultural heritage can also be seen clearly in the Basoeki Abdullah Museum, where the museum was renovated to expand the building, increase the number of collections, and accommodate more visitors. The last approach is through infrastructure improvement, visible in Gambir and Kota Tua. In the former district, revitalization was done by increasing pedestrian routes to make them more user-friendly, while in the latter one, it was seen through expanding the pedestrian area, creating bicycle paths, organizing street vendors, and improving some vacant spaces to become green open spaces.

There are only two districts that have a Tourist Information Centre (TIC). For the one located in Menteng, it is challenging to find, especially for international tourists, as it is less strategically located due to its small size and location inside a building with ambiguous signs. The other one, in Sawah Besar, is located in three different attractions, namely Istiqlal Mosque, Cathedral Museum, and Church. Regardless of the location, the use of technology can be seen in both districts through the provision of information kiosks and screen guides that facilitate visitors in obtaining various information related to tourism in Jakarta, including attractions, transportation, lodging, culinary options, and other information.

Regarding the implementation of chip-based Smart Tourist Cards, there is one card for tourists, called JakCard, making it simpler for them to use all modes of public transit in Jakarta and visit a number of the city’s tourist attractions. Four districts offer JakCard-enabled attractions, including the Joang 45 Building, MH Thamrin Museum, National Monument, National Museum, Fatahillah Museum, Puppet Museum, Museum of Fine Arts and Ceramics, and Ragunan Zoo. Meanwhile, Sawah Besar and Kebayoran Baru are two districts without JakCard-compatible attractions.

The revitalization of several tourist attractions in Jakarta is the result of urban regeneration projects in 30 areas in Jakarta. They have successfully created a new look for Jakarta as a more convenient, attractive, and lively city not only for tourists but most importantly for the local community. While the projects showcase their ability to improve already-built attractions, they also contribute to making abandoned and slum areas new attractions and centers of community activities, aligning with Oh’s (Citation2020) idea on smart city development as a means of changing infrastructures and services of urban places, as well as a tool for regenerating established cities in terms of their attractiveness to improve the quality of life, socio-economic development, and more engaged and inclusive citizens. The projects also align with Lee et al. (Citation2020) perspective on the development of a smart tourism city in transforming travel experiences into more enriched, efficient, and sustainable experiences, incorporating smart technology to change and diversify the city into a desired destination.

5.2. Accessibility

The analysis of the six districts found that almost all attractions have adopted digital tools such as websites and social media as their promotional media, with more attractions utilizing social media for promotion than websites. However, among the various existing attractions, only six attractions in four districts provide bilingual websites. It is important to note that only the Basoeki Abdullah Museum offers a virtual tour. Meanwhile, not a single attraction has included information for persons with disabilities on their website and social media. Historical museums and public areas like city parks are a few attractions that have yet to use digital promotion.

Regarding physical accessibility, the six districts already have strong public transportation, both to and within the district. This is demonstrated by the fact that all districts can be reached by various forms of public transportation, including the TransJakarta BRT, online taxi bikes, commuter train, taxis, and local transportation Jaklingko. The MRT access is the only differentiator; only four districts may be reached using this mode of transportation.

The facilities typically owned by most attractions for people with disabilities and the elderly include guiding blocks, wheelchairs, and ramps. Several attractions, including TIM, Sarinah, Basoeki Abdullah Museum, and Cathedral Museum, have also installed disabled lifts. It is noteworthy that the Basoeki Abdullah Museum provides an information room with Braille lettering to make it simpler for visitors with visual impairments to acquire information while at the museum. On the other hand, Ragunan Zoo, one of Jakarta’s major attractions, does not offer any facilities except for its accessible restrooms.

The importance of accessibility is mentioned by Tóth and Dávid (Citation2010) as fundamental preconditions in urban tourism, as it links tourists to destinations that need to be accessed, while (Eichhorn & Buhalis, Citation2010) identify different dimensions of accessibility, including physical or spatial access, access to information, and access to social activities and services. Li et al. (2022) even mentioned that improved mobility from the growth development of transportation and advanced technology has made urban tourism grow rapidly.

5.3. Digitalization readiness

Regarding the availability of digital infrastructure, some attractions in the six districts have provided information kiosks as part of their digital infrastructure. Since they have not been operational for a considerable time and no efforts have been made to upgrade them, the availability of these information kiosks still needs to be improved, particularly in several historical museums. Only six of the 25 attractions now offer audio/visual tour services at the museum, while the remainder still relies on professional museum guides to lead visitors. For other digital infrastructure, such as sensors, most attractions still use only temperature sensors as part of the health protocol and metal detectors to detect visitors’ luggage. There is only one attraction in Kota Tua, namely the Bank Indonesia Museum, which has sensors to detect crowd density as well as other features like light sensors that turn on automatically when visitors enter the room and interactive sensors that give the impression that visitors can flip the pages of a digital book without touching it. Free public wi-fi is another form of digital infrastructure that many locations and attractions already offer. Only the attractions in Cilandak and Kota Tua (besides Petak Enam) do not provide free wi-fi. It is also unlikely owned by museums and most are owned by art and cultural spaces.Along with attractions, free wi-fi is available in a number of public places, including stations.

The presence of mobile apps especially made by the attraction or district to guide visitors independently is only found in four attractions: Sarinah (Menteng), Istiqlal Mosque (Sawah Besar), Ragunan Zoo (Cilandak), Bank Indonesia Museum (Kota Tua). Each attraction has an application that provides various information to guide visitors when visiting them, from maps of the area, events and promotions, and other information about the attractions. In the case of integrated payment system for domestic and international tourists, Sawah Besar is the ideal district, as payment at most attractions has been integrated using digital wallets, QRIS, and EDC machines. Meanwhile, Cilandak and Kota Tua are the least integrated payment system-equipped districts, where most attractions in these districts still solely accept cash. The analysis results also demonstrate that most integrated attractions are art and cultural spaces, whereas museums and public spaces are the least.

5.4. Sustainability

Along with initiatives to revitalize old buildings into new attractions, there have been several efforts made by the district and attractions to promote sustainable growth. Findings showed that all attractions have provided separate waste bins to sort garbage between organic and non-organic waste. In practice, nonetheless, the use of segregated waste bins has not been carried out well by the locals because the two types of waste are still mixed.

In some districts, shared bicycles are provided, although they come in various shapes and sizes. For instance, in Kota Tua, there are antique bikes that not only enable using bicycles to get around the district but also serve as one of the tourist attractions. Other than that, there is a bike-sharing mobile application, an application to rent bicycles, called "Gowes". Several attractions in two districts, Menteng and Gambir, have provided bicycles integrated with the app through the barcode attached to the bicycles. The government, under the Jakarta Transportation Agency and a local start-up, manages this bicycle rental.

Other attempts have been explicitly shown in each district, such as energy-efficient lighting and a used bottle exchange facility are available in the Istiqlal Mosque, Lapangan Banteng routinely organizes eco-friendly events, while Menteng and Gambir serve electric buses as part of Jakarta’s attempt to support the achievement of net-zero emissions. At Pos Bloc, porous concrete is utilized, which is safe for the environment and improves water absorption into the earth, while Ragunan Zoo provides electric cars that visitors may rent, and there is also a charging station where they can utilize solar energy to charge their cell-phones or other electrical devices. Bank Indonesia Museum also makes use of a light sensor that only activates when someone enters the space.

The sustainability aspect in the development of urban tourism city in Jakarta varied from the more sustainable and environment friendly practices such as waste management, the use of electric vehicle, the cleaning of water bodies both river and beach, to the promotion of renewable energy transition to replace the unsustainable fossil energy. The sustainable premises in smart tourism are consistent with the model proposed by Del Vecchio et al. (Citation2022) and (Pranita et al., Citation2023) which includes the circular economy consideration, as well as (Hilty & Aebischer, Citation2015) and (Madeira et al., Citation2023) that propose smart and sustainability aspects to be implemented inseparable and complementing each other.

5.5. Implications of the study

The study takes a holistic approach by examining various dimensions of smart tourism, including attractiveness, accessibility, digitalization readiness, and sustainability. This comprehensive analysis contributes to a better understanding of how these components interact and influence the overall development of Jakarta as a smart tourism city. This study also contributes valuable insights to the concept of a smart tourism city by providing a detailed assessment of the current state of tourism development in Jakarta.

Previous research predominantly concentrated on the conceptual development and framework of the Smart Tourism City (STC). There is a scarcity of studies that apply and employ the indicators of STC to measure a city’s smartness (Tran et al., Citation2017). Consequently, this study makes a valuable contribution by testing the existing STC framework in a pilot study to assess the city’s level as a smart tourism destination and the extent to which it meets the proposed indicators. Our case study revealed deficiencies in two key aspects: digital mobility and sustainability.

It was also evident that the city’s initiatives to position Jakarta as a smart tourism destination primarily stem from its development as a smart city. In simpler terms, many indicators have been met, not necessarily with the sole purpose of enhancing Jakarta as a smart tourism city but potentially intended to support its role as a smart city. Examples of these efforts include the restoration of historical and cultural heritage buildings, robust public transportation networks spanning all six districts, integrated payment systems, provision of free public Wi-Fi, sustainable transportation options, and endeavors toward energy-efficient practices. Meanwhile, tourist facilities, particularly those catering to tourists, exhibit discrepancies in digital infrastructure availability across various attractions. There are limitations in the availability of Tourist Information Centres, information kiosks, and mobile apps, with only four attractions offering mobile apps for independent visitor guidance. The study aligns with La Rocca (Citation2014), indicating that smart urban solutions for tourism primarily focus on optimizing specific resources or urban mobility systems while tourist-specific data, such as crowd density or preferences from mobile apps, is underutilized in enhancing the overall tourism experience.

The findings of the study have several practical implications for policymakers, urban planners, tourism authorities, and other stakeholders involved in the development and management of urban tourism in Jakarta to further enhance Jakarta’s position as a smart and attractive tourism destination. First, tourism authorities can focus on integrating technology more effectively, such as developing mobile apps for attractions, improving information kiosks, and expanding the use of smart cards. This can enhance the overall visitor experience and contribute to the concept of a smart tourism city. Furthermore, stakeholders can also work towards making tourism more inclusive by addressing accessibility challenges. This includes improving facilities for persons with disabilities, ensuring bilingual information on websites, and enhancing the overall accessibility of attractions.

The study also highlights the importance of collaboration and networking, particularly in the provision of Tourist Information Centres. Stakeholders can work together to establish more strategically located information centers, improving overall service and accessibility for tourists. Urban planners and environmental authorities can build on the sustainability initiatives identified in the study. This may involve expanding waste management programs, promoting eco-friendly events, and further integrating renewable energy solutions in tourist attractions. In essence, the practical implications involve leveraging the study’s insights to enhance the overall tourism infrastructure, services, and experiences in Jakarta, ultimately contributing to the city’s transformation into a smart and sustainable tourism city.

6. Conclusion

Jakarta has put a lot of efforts to build smart tourism city by improving and integrating various attractions, linking physical and digital infrastructure to improve accessibility and mobility. As digitalization is carried out piece by piece, total tourist digital experience has not yet achieved, while integration and uniformity of information to create smart tourism city branding has not yet been seized. Even though there are attempts for sustainability practices especially in energy saving and waste management activities, the efforts are still partially implemented and not yet become an overall massive city campaign. In general, it is found out that the stages of smart tourism city development in Jakarta mostly focuses in physical and technological aspects while human and social capital aspects are still overlooked. As Jakarta is one of the most populated cities in the world, human and social capital become very crucial to attain and sustain smart tourism city as a whole. There is an urgent need to educate citizens especially those working and living within urban tourism attractions as the robustness of sustainable smart tourism city will highly depend on their participation both in sustaining the smartness implementation or maintaining governance participatory in tourism development. A constant promotion of urban tourism in the smart tourism city context is also important to enhance visitors experience in consuming tourism products and services. Furthermore, innovative and creative ways to enhance city attractiveness with cultural and tourism events, new technology utilization or other interesting activities, while also creating interesting story-telling and selecting smart and innovative media to spread city events and tourism information will add value to total tourist’s experience in the city.

Learning from best practices in Europe is also a good way to expedite the development of smart tourism city in Jakarta as several cities have shown the more advance implementation of the smart concept. From this standpoint, EU initiative focuses on four aspects: access for all including the disables; sustainability, which focus on reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reduction, energy savings community inclusion; digitalization through data driven destination management; and cultural heritage and creativity. Helsinki became the best practice with its innovation and creativity in mobility by creating uber boat system and driverless busses, the ability to reviving tradition and cultural heritage sustainability, and the usage of cultural heritage for new creativity. Lyon becomes the sample of the best accessibility at the center of urban life especially for visitors with disabilities and reduced mobility. In addition to smart city application, the EU initiative also focuses on energy savings. Barcelona, Cologne and Stockholm in grow smarter category. The cities focus on CO2 emission reduction, energy saving in building, clean fuels and car sharing program. Sonderborg and Tartu focus on ambitious Smart En City category that they develop electrification and integration of wind energy, rooftop voltaic power, and smart zero carbon (EU Smart Cities Information System, Citation2017).

To conclude, Jakarta must embark on a multifaceted approach to transform sustainability initiatives into a cohesive and collective campaign within its smart tourism city development. First and foremost, it needs to pinpoint specific areas of sustainability within this development framework. This involves a meticulous examination of partner networks, operating environments, and its own activities to identify key indicators. Beyond mere identification, Jakarta must actively shape the behavior of both visitors and locals. This entails fostering a demand for sustainable tourism services, advocating for inclusive digital platforms, and promoting overarching themes for actionable measures. Furthermore, Jakarta must cultivate a collaborative ecosystem with diverse stakeholders. This collaboration should embody traits such as responsibility, innovation, accessibility, inclusivity, and versatility. Establishing robust cooperation and engagement is crucial, not only within the city but also with neighboring areas. This collaboration could extend to sharing sustainable smart infrastructure and engaging in extensive cooperation for practical responsibility actions.

As part of its commitment to smart carbon-wise initiatives, Jakarta should create a dedicated smart tourism living lab. This living lab serves as a hub for research and development, providing a space to experiment and innovate in the realm of sustainable practices. Lastly, an emphasis on collaboration in marketing and regional development initiatives will ensure that sustainability remains a focal point in the broader strategy for the city’s growth and prosperity. Through these concerted efforts, Jakarta can truly propel its sustainability initiatives into a unified and impactful campaign.

Based on the findings of the current study, future research in the field of smart tourism in Jakarta could delve deeper into specific areas that have been identified as deficient, particularly digital mobility and sustainability. Exploring strategies and initiatives to address these deficiencies would contribute valuable insights into how Jakarta can enhance its smart tourism offerings. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for research to focus on the integration of smart technologies in the preservation and promotion of historical and cultural heritage buildings. Understanding how technology can be harnessed to both conserve these assets and enhance the visitor experience would be a worthwhile avenue of exploration.

Given that the study indicates a connection between Jakarta’s development as a smart city and its initiatives to position itself as a smart tourism destination, future research could investigate the synergies and tensions between these two goals. It would be interesting to explore whether initiatives intended to support the broader smart city agenda inadvertently benefit or hinder the city’s aspirations to become a leading smart tourism destination. Moreover, a more in-depth analysis of the discrepancies in digital infrastructure availability across various tourist facilities, especially those catering to tourists, could provide insights into potential interventions. Identifying barriers and proposing solutions to improve the digital readiness of tourist facilities could significantly contribute to Jakarta’s efforts to enhance the overall tourism experience.

Future research could explore the untapped potential of tourist-specific data in smart tourism. Investigating how crowd density information, visitor preferences obtained through mobile apps, and other data sources can be effectively utilized to optimize the tourism experience aligns with the study’s suggestion that such data is currently underutilized. This avenue of research could provide practical recommendations for leveraging smart technologies to tailor tourism experiences in Jakarta based on real-time information and preferences.

Lastly, we recognize that our study has limitations, foremost among them being that this current endeavor marks the preliminary stage of our exploration into evaluating Jakarta’s preparedness as a smart tourism city. Future research endeavors should encompass comprehensive interviews with pertinent stakeholders to enhance the credibility and robustness of our findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albino, V., Berardi, U., & Dangelico, R. M. (2015). Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance and initiatives. Journal of Urban Technology, 22(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2014.942092

- Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J., & Seisdedos, G. (2020). Smart urban tourism destinations at a crossroads-being “smart” and urban are no longer enough. In The Routledge handbook of tourism cities. Routledge.

- Angelidou, M., Karachaliou, E., Angelidou, T., & Stylianidis, E. (2017). Cultural heritage in smart city environments. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-2/W5, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W5-27-2017

- Ariansyah, K., Setiawan, A. B., Hikmaturokhman, A., Ardison, A., & Walujo, D. (2024). Big data readiness in the public sector: an assessment model and insights from Indonesian local governments. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-01-2023-0010

- Arief, A., Abbas, M. Y., Wahab, I. H. A., Latif, L. A., Abdullah, S. D., & Sensuse, D. I. (2020). The smart islands vision: Towards smart city readiness in local government of archipelagos. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1569(4), 042006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1569/4/042006

- Ashcroft, M., Austin, R., Barnes, K., MacDonald, D., Makin, S., Morgan, S., Taylor, R., & Scolley, P. (2016). Expert judgement. British Actuarial Journal, 21(2), 314–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1357321715000239

- Boes, K., Buhalis, D., & Inversini, A. (2016). Smart tourism destinations: ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2(2), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2015-0032

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In I. Tussyadiah, & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 377–389). Springer. ISBN:9783319143422.

- Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., & Nijkamp, P. (2011). Smart cities in Europe. Journal of Urban Technology, 18(2), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2011.601117

- Chan, C. S., Peters, M., & Pikkemaat, B. (2019). Investigating visitors’ perception of smart city dimensions for city branding in Hong Kong. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 620–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-07-2019-0101

- Chowdhury, M. (2016). Emphasizing morals, values, ethics, and character education in science education and science teaching. The Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Science, 4, 1–16.

- Chung, N., Lee, H., Ham, J., & Koo, C. (2021). Smart tourism cities’ competitiveness index: A conceptual model. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2021. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65785-7

- Cohen, B. (2013). Smart cities wheel. https://www.smart-circle.org/smartcity/blog/boyd- cohen-the-smart-city-wheel/.

- Del Vecchio, P., Malandugno, C., Passiante, G., & Sakka, G. (2022). Circular economy business model for smart tourism: the case of Ecobnb. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-09-2020-0098

- Eichhorn, V., & Buhalis, D. (2010). Accessibility: A key objective for the tourism industry. In D. Buhalis & S. Darcy (Ed.), Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues (pp. 46–61). Channel View Publications. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845411626-006

- EU Smart Cities Information System. (2017). The making of a smart city: best practices across Europe empowering smart solutions for better cities. European Commission. www.smartcities-infosystem.eu.

- European Capital of Smart Tourism. (2022). Leading examples of smart tourism practices in europe. https://smart-tourism-capital.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-05/Best%20Practice%20Report_2022_Update.pdf

- Freeman, G., Bardzell, J., Bardzell, S., Liu, S.-Y., Lu, X., & Cao, D. (2019 Smart and fermented cities: An approach to placemaking in urban informatics [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 44, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300274

- Gajdošík, T. (2018). Smart tourism; Concept and insight from central europe. Czech Journal of Tourism, 7(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjot-2018-0002

- Gelbman, A. (2020). Smart tourism cities and sustainability. Geography Research Forum, 40(1), 137–148.

- Giriwati, N., Homma, R., & Iki, K. (2013). Urban tourism: Designing a tourism space in a city context for social sustainability. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 179(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.2495/SC130141

- Göktaş Kulualp, H., & Sarı, Ö. (2020). Smart tourism, smart citie and smart destinations as knowledge management tools. In E. Celtek (Eds.), Handbook of research on smart technology applications in the tourism industry (pp. 371–390). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1989-9.ch017

- Gretzel, U., & Koo, C. (2021). Smart tourism cities: A duality of place where technology supports the convergence of touristic and residential experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1897636

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015). Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0196-8

- Gündüz, C., & Atak, O. (2023). Environmental effects of tourism activities in Niksar Çamiçi Plateau in the context of sustainable tourism: a qualitative research. International Journal of Agriculture Environment and Food Sciences, 7(3), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.31015/jaefs.2023.3.16

- Hilty, L., & Aebischer, B. (2015). Smart sustainable cities: Definition and challenges. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 310, 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09228-7

- Hunter, W. C. (2021). Cultural representations and experience in tourism: Two forms of mimesis. Journal of Smart Tourism, 1(1), 65–67. https://doi.org/10.52255/smarttourism.2021.1.1.8

- Ivars-Baidal, J. M., Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A., Femenia-Serra, F., Perles-Ribes, J. F., & Vera-Rebollo, J. (2023). Smart city and smart destination planning: Examining instruments and perceived impacts in Spain. Cities, 137, 104266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104266

- Ivars-Baidal, J. A., Vera-Rebollo, J. F., Perles-Ribes, J., Femenia-Serra, F., & Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A. (2021). Sustainable tourism indicators: What’s new within the smart city/destination approach? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1556–1582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1876075

- Jasrotia, A. (2018). Smart cities to smart tourism destinations: A review paper. (ISSN 2249-7307). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327536704

- Kelly, P. G., Peacock, D., Sanderson, D. J., & McGurk, A. C. (1999). Selective reverse-reactivation of normal faults, and deformation around reverse-reactivated faults in the Mesozoic of the Somerset coast. Journal of Structural Geology, 21(5), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8141(99)00041-3

- Koo, C., Shin, S., Kim, K., Kim, C., & Chung, N. (2013). Smart tourism of the Korea: A Case Study. PACIS 2013 Proceedings (p. 138). https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2013/138

- La Rocca, R. A. (2014). The role of tourism in planning the smart city. TeMA – Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, 7(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.6092/1970-9870/2814.

- Lamsfus, C., Martín, D., Alzua-Sorzabal, A., & Torres-Manzanera, E. (2015). Smart tourism destinations: An extended conception of smart cities focusing on human mobility. In I. Tussyadiah & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism (127th ed., pp. 363–375). Springer.

- Lee, P., Hunter, W. C., & Chung, N. (2020). Smart tourism city: Developments and transformations. Sustainability, 12(10), 3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103958

- Levyta, F., Putra, A. N., Wahyuningputri, R. A., Hendra Rahmanita, M., & Djati, S. P. (2022). Smart tourism strategy and development post COVID-19: A study in native Jakarta culture site. In Current issues in tourism, gastronomy, and tourist destination research (pp. 188–194). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003248002-25

- Lily Anita, T., Wijaya, L., & Kusumo, E. (2021). Smart tourism experiences: Virtual tour on museum [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management. https://www.museumnasional.or.id/virtual-tour. https://doi.org/10.46254/AN11.20210813

- Liu, P., & Liu, Y. (2016). Smart tourism via smartphone [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Communications, Information Management and Network Security, 129–132. https://doi.org/10.2991/cimns-16.2016.33

- Madeira, C., Rodrigues, P., & Gomez-Suarez, M. (2023). A bibliometric and content analysis of sustainability and smart tourism. Urban Science, 7(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020033

- Mahesa, R., Yudoko, G., & Anggoro, Y. (2019). Dataset on the sustainable smart city development in Indonesia. Data in Brief, 25, 104098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.104098

- Manggalou, S., Azizatun Nafi’ah, B., Uang, Y., & Dewi, A. (2023). Smart city development strategy of Wonogiri Regency. International Journal of Science, Technology & Management, 4(6), 1703–1712. https://doi.org/10.46729/ijstm.v4i6.1007

- Moura, F., & de Abreu e Silva, J. (2021). Smart cities: Definitions, evolution of the concept, and examples of initiatives. 989–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95873-6_6

- Moura, F., & de Abreu e Silva, J. (2021). Smart cities: Definitions, evolution of the concept and examples of initiatives. In W. Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, P. Özuyar, & T. Wall (Eds.), Industry, innovation and infrastructure. Series: Encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals (pp. 1–9). Springer Nature. ISBN: 9783319710594.

- Mukti, I., & Prambudia, Y. (2018). Challenges in governing the digital transportation ecosystem in Jakarta: A research direction in smart city frameworks. Challenges, 9(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9010014

- Mutiara, D., Yuniarti, S., & Pratama, B. (2017). Smart governance for smart city. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 126, 012073. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/126/1/012073/meta

- Noori, N., de Jong, M., & Hoppe, T. (2020). Towards an integrated framework to measure smart city readiness: The case of iranian cities. Smart Cities, 3(3), 676–704. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030035

- Oh, J. (2020). Smart city as a tool of citizen-oriented urban regeneration: Framework of preliminary evaluation and its application. Sustainability, 12(17), 6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176874

- Ortega, J., & Malcolm, C. (2020). Touristic stakeholders’ perceptions about the smart tourism destination concept in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(5), 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051741

- Pranita, D., & Kesa, D. D. (2021). Digitalization methods from scratch nature towards smart tourism village; Lessons from Tanjung Bunga Samosir, Indonesia. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1933(1), 012053. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1933/1/012053

- Pranita, D., Sarjana, S., Musthofa, B. M., Kusumastuti, H., & Rasul, M. S. (2023). Blockchain technology to enhance integrated blue economy: A case study in strengthening sustainable tourism on smart islands. Sustainability, 15(6), 5342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065342

- Pribadi, T. I., Tahir, R., & Yuliawati, A. K. (2021). InfoTekJar : Jurnal Nasional Informatika dan Teknologi Jaringan Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International. Some rights reserved smart tourism the challenges in developing smart tourism: A literature review. InfoTekJar : Jurnal Nasional Informatika Dan Teknologi Jaringan, 5(2), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.30743/infotekjar.v5i2.3462

- Psaltoglou, A. (2018). From smart to cognitive cities: Intelligence and urban utopias. Archi DOCT, 6(1), 95–106. http://www.archidoct.net/Issues/vol6_iss1/ArchiDoct_vol6_iss1%2006%20From%20Smart%20to%20Cognitive%20Cities%20Psaltoglou.pdf

- Romão, J., Kourtit, K., Neuts, B., & Nijkamp, P. (2018). The smart city as a common place for tourists and residents: A structural analysis of the determinants of urban attractiveness. Cities, 78, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.007

- Sangaji, M. S. J., Zorayya Priyanti Noor, P., & Navasari, S. (2021). Analisis kebijakan Jakarta smart city menuju masyarakat madani. Journal of Government Insight, 1(2), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.47030/jgi.v1i1.53

- Shafiee, S., Rajabzadeh Ghatari, A., Hasanzadeh, A., & Jahanyan, S. (2019). Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31(June), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.06.002

- Smart Tourism Capital.EU. (2022). Leading examples of smart tourism practices in Europe March 2022. EUTourismCapital.

- Soares, J. C., Domareski Ruiz, T. C., & Ivars Baidal, J. A. (2021). Smart destinations: A new planning and management approach? Current Issues in Tourism, 25(17), 2717–2732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1991897

- Sotiriadis, M. (2022). Smart tourism in practice: The EU initiative “European capitals of smart tourism. Études Caribéennes, 51(51). https://doi.org/10.4000/etudescaribeennes.23758

- Sun, S., Ye, H., Law, R., & Hsu, A. Y.-C. (2022). Hindrances to smart tourism development. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(4), 763–778. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-10-2021-0300

- Supangkat, S. H., Arman, A. A., Fatimah, Y. A., Nugraha, R. A., & Firmansyah, H. S. (2020). The role of living labs in developing smart cities in Indonesia. In Data-driven multivalence in the built environment (pp. 223–241). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12180-8_11

- Szwed, P. S. (2016). Expert judgment in project management. Project Management Institute, Inc.

- Tóth, G., & Dávid, L. (2010). Tourism and accessibility: An integrated approach. Applied Geography, 30(4), 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.01.008

- Tran, H. M., Huertas, A., & Moreno, A. (2017). (SA) 6: A new framework for the analysis of smart tourism destinations. A comparative case study of two Spanish destinations. Publicacions de la Universitat d’Alacant (pp. 190–214). https://doi.org/10.14198/Destinos-Turisticos-Inteligentes.2017.09

- Üstündağ, B. (2021). Towards more-than-human participation: Rethinking smart city. International Symposium of Architecture, Technology and Innovation, 76–87. https://ati.yasar.edu.tr/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/ATI-Proceedings_compressed.pdf

- Widodo, B., & Dasiah, A. N. (2021). Analisis strategi konsep smart tourism pada Dinas Pariwisata dan Ekonomi Kreatif Jakarta. Jurnal Ilmiah Pariwisata, 26(3), 294. https://doi.org/10.30647/jip.v26i3.1498

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Zhu, Y. Q., & Alamsyah, N. (2022). Citizen empowerment and satisfaction with smart city app: Findings from Jakarta. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121304