Abstract

Even though previous literature points to the significance of establishing the cognitive, social and teaching presences of students, there is still scanty research in relation to how the higher education curriculum could assist the 21st century student develop 21st century skills through the establishment of the cognitive, social and teaching presences through the perspective of the Community of Inquiry Framework. Also, such research is complex, limited and highly contested within the higher education landscape in the sense that there are dissenting views about establishing these presences. In order to address this literature gap, the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used to unveil how the cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence inform the development of a holistic curriculum in the 21st century. The instrument used as the research tool was adapted from the original CoI framework survey. Using the descriptive correlational research design, survey data was elicited from 807 students who were proportionately stratified into male and female. It emanated from the study that there is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive, social and teaching presences of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. It is therefore recommended that curriculum developers should ensure a holistic development of the higher education curriculum by ensuring that all the presences are duly established. Lecturers should also endeavor to ensure that each of these presences is established in their lessons to promote lifelong learning by way of enhancing the 21st century curriculum.

IMPACT STATEMENT

In this current dispensation, the school system has been occupied with diverse learners. This has warranted the necessity to search for new, innovative and dynamic ways of engaging these diverse learners in order to promote effective teaching and learning. There should, therefore, be an intentional effort on the part of educational stakeholders, especially curriculum developers and instructors to think through and implement an ideal curriculum that will cater for the individual and collective needs of these diverse learners. Based on our rigorous engagement with the extant literature and keen observation and experiences, we are of the strongest conviction that the effective adoption of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework is one of the crucial solutions to enhancing the 21st century curriculum within the educational landscape. This conviction is informed by the outstanding finding that there is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. Hence, the choice of this topic.

Introduction

It is an undisputed fact that the foundation for all successful learning is the development of the cognitive domain of an individual (Sezgin, Citation2020). Thus, the cognitive presence of the learner serves as the anchor for effective teaching and learning. And that a certain enabling environment should be created to ensure the effective establishment of the cognitive as well as the social and teaching presences of the 21st century student. By so doing, the Communities of Inquiry (CoI) framework is being embraced. A community of inquiry is defined as “a group of individuals who collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding” (Garrison, Citation2015, p. 2) made up of the cognitive, social and teaching presences.

In spite of the several curriculum changes, transformations and drastic reforms coupled with the supposedly mimicking of the superficial Western educational systems and cultures which appear not to reflect the Ghanaian local context, academic commentators still argue that the cognitive, social and teaching presences of the 21st century learner have still not been explicitly established. This is attributed to the fact that the higher education curriculum of Ghana is perceived to be ineffective, rigid, impractical and mono-disciplinary, resulting in the production of sterile educational practises pointed towards the continuous emphasis on the conventional ways of teaching and learning characterised by knowledge transmission and not production; thus, producing students who are knowledge creators and producers but not knowledge receptors (Filippou, Citation2015). This could be attributed to the seemingly inadequate integration of these 21st century skills into the Ghanaian curriculum. The integration is inadequate because, in contrast to the characteristics of the 21st century skills that include flexibility, practical, as well as, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary, the Ghanaian curriculum, as it stands currently, is rigid, impractical and mono-disciplinary (Fiock, Citation2020). Therefore, an intentional and intensive effort is required to strengthen its integration to make it more effective.

The variables under study in context, could be described as follows: Social Presence is “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (Garrison, Citation2015, p. 352); Cognitive Presence describes the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse in a critical Community of Inquiry (Garrison et al., Citation2000); Lastly, but not least, Teaching Presence connotes the design, facilitation and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realising personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes (Garrison et al., Citation2000). It is interesting to note that all these presences are not really felt nor understood, especially, in the context of the Ghanaian educational landscape, leading to the creation of knowledge and practice gap. Hence, the essence of this study.

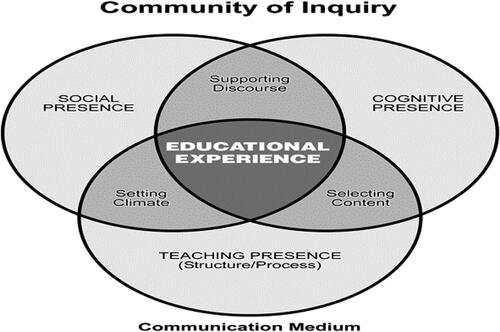

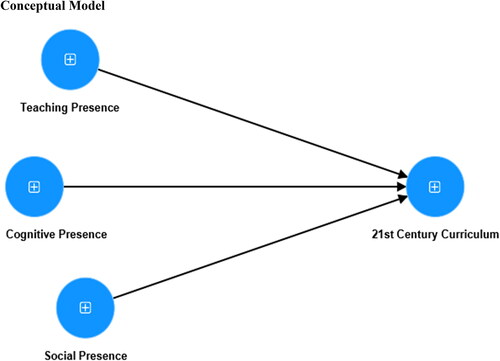

In order to close the gaps in knowledge creation and practice, it is imperative for contemporary educational institutions, especially those in Ghana, to embrace and apply the formidable framework of Communities of Inquiry in their quest to integrate into the 21st century student, knowledge creation and production skills, as well as competencies as a way of building the cognitive, social and teaching presences of the 21st century learner critical to the development of Ghana. This could be attributed to the fact that the CoI framework is a highly innovative and creative solution to contemporary problems confronting the current educational institutions (Hosler & Arend, Citation2012). Hence, this framework must be embraced by all educational institutions in these contemporary times regardless of the level. These 21st century skills include communication skills, critical thinking skills, creative thinking skills, collaboration and teamwork, personal and social skills put side-by-side with the Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework that includes teaching presence, social presence and cognitive presence ( and ).

A number of empirical studies have reported potential benefits of social presence (Alman et al., Citation2012; Bulu, Citation2012; Filippou, Citation2015; Wei et al., Citation2012; Zetou et al., Citation2011), teaching presence (Antoniou et al., Citation2003; Garrison et al., Citation2010), and cognitive presence in teaching and learning (Alman et al., Citation2012; Hosler & Arend, Citation2012). The benefits of these presences cannot be over-emphasised within the higher educational context. However, attention has not been drawn to the relationships among these presences and the development of the 21st century skills through the 21st century curriculum. Hence, the focus of this study. Illustratively, Maddrell, Morrison, and Alman et al. (Citation2012) report that only cognitive presence correlates significantly and positively with achievement measures. Bates (Citation2019), further reiterates that as part of establishing the cognitive presence of students, teachers have to skilfully and tactically ask relevant and intriguing questions that are capable of piquing students’ curiosity. Contributing to the discourse, Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009), through their study, indicated that both social and teaching presences have the tendency to affect students’ learning process through instructional design, discourse facilitation, and direct instruction orchestrated by the teacher. On the other hand, Ladyshewsky (Citation2013) reported that teaching presence appeared to positively influence students’ satisfaction with an online course of study.

There is a wide range of studies that focus on the factors which influence satisfaction in relation to these presences (Vernadakis et al., Citation2011; Vernadakis et al., Citation2014); there are studies which chose to explore predictors of satisfaction, specifically the role of satisfaction in relationship with social presence (Cho, Citation2011; Robb & Sutton, Citation2014), teaching presence (Bebetsos, Citation2015; Hosler & Arend, Citation2012), and cognitive presence (Alman et al., Citation2012; Hosler & Arend, Citation2012). However, the extant literature indicates that there are few studies that focused on cognitive, social, and teaching presences as predictors of students’ satisfaction and for that matter, the development of 21st century skills. Therefore, till date, there have been few empirical studies (Hosler & Arend, Citation2012; Robb & Sutton, Citation2014) on the relationship between the COI Framework and the development of 21st century skills, indicating that much attention has not been drawn to how this relationship may enhance the development of the 21st century curriculum.

Furthermore, previous researches on these critical educational presences informed by the communities of inquiry framework have been conducted predominantly in Western countries, with very few studies done in non-Western contexts; suggesting that studies on the phenomenon in the African context are extremely scanty. However, studies by Kibuku et al. (Citation2020), in Kenya, and Filippou (Citation2015), in South Africa, are notable exceptions. We are, therefore, hesitant to indicate that this study is a maiden one to be undertaken in Ghana by taking into consideration the variables underpinning the study. While these studies contribute to our understanding of these critical educational presences in different African contexts, it is important to understand the relationships among these presences regarding the development of 21st century skills within the context of the 21st century curriculum.

In the year 2022, the Minister of Education of Ghana, speaking at a UN Session indicated, “you cannot memorise your way out of poverty, but you can embark on critical thinking and problem-solving pedagogy to curb poverty” (Dr. Osei Adutwum, the Minister of Education of the Republic of Ghana). Impliedly, in order to cultivate the attitude of critical thinking and problem-solving in the 21st century learner, the framework of Communities of Inquiry is key to solving such problems by providing the learner with the necessary insights to make more assertive in order to challenge the status quo and not just accept knowledge as it is (Akyol & Garrison, Citation2011). This presupposes that those learners should be trained in such a way that they will not accept any knowledge given them, but will be able to synthesise and analyse such knowledge and decide whether they will assimilate it or not, based on its juxtaposition within the context. As part of the basis for formulating the hypothesis for this study, Sezgin’s (Citation2020) study analysed the cognitive presence in online discussions through a content analysis and is relevant that the phase of exploration is the most predominant phase of cognitive presence. Fiock (Citation2020) also found out that there was no statistically significant relationship between exploration, which is one of the crucial elements of cognitive presence, and the development of critical thinking skills which form a core of the 21st century curriculum. It is on the basis of these arguments and assertions that the following hypotheses are framed:

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the social presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the teaching presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum.

Theoretical underpinnings of the study

The theoretical perspective adopted to explain the phenomenon under investigation is the

Community of inquiry model

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) is developed based on the social constructivism theoretical approach which suggests that knowledge is co-constructed. The Community of Inquiry is a theoretical model for the optimal design of online learning environments to support critical thinking, critical inquiry and discourse among students and teachers with the aid of computer mediated instructions wherein social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence encourage positive educational experiences for teachers and students (Garrison et al., Citation2000). However, that is not to imply that the model is not applicable in relation to the face-to-face teaching and learning processes. The theory had its historical antecedent form the work of John Dewey, and is consistent with the constructivist perspectives to learning in the higher education landscape (Garrison, Citation2015).

The basic assumption undergirding the CoI framework is that an educational experience intended to achieve higher-order learning outcomes is best embedded in a community of inquiry composed of students and teachers (Lipman, Citation1991). Lipman (Citation2003) further argues that the necessity of a community of inquiry is for the operationalisation of critical or reflective thinking and as an educational methodology. This assumption was also consistent with the educational philosophy of Dewey (Citation1959) who described education as the collaborative reconstruction of experience. The context for this study was a collaborative-constructivist learning experience within the context of the community of inquiry framework. An educational community of inquiry is a group of individuals who collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding.

The aforementioned framework is relevant to this current empirical research because according to Garrison et al. (Citation2000), “the elements of a community of inquiry can enhance or inhibit the quality of the educational experience and learning outcomes” (p. 92). The model describes how learning occurs for a group of individual learners through the educational experience that occurs at the intersection of social, cognitive and teaching presences. The elements that make up the model are social presence, teaching presence and cognitive presence. They are briefly explained below:

Social Presence: is “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (Garrison, Citation2015, p. 352).

Cognitive Presence: The extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse in a critical Community of Inquiry (Garrison et al., Citation2000).

Teaching Presence: The design, facilitation and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes (Garrison et al., Citation2000).

Community of inquiry model adapted from Garrison and Anderson (2003)

The Community of inquiry framework and the body of surrounding research were criticized for a lack of empirical evidence that the framework leads to deep and meaningful learning outcomes (Rourke & Kanuka, Citation2009). While some view the CoI framework as supportive of the underlying theoretical assumptions (Akyol et al., Citation2009; Garrison & Arbaugh, Citation2007; Garrison et al., Citation2010), others argue that the community of inquiry research has been preoccupied with just the validation of methods to measure communication, interaction, and student perceptions while failing to investigate the framework’s central claim that a Community of inquiry, with the prerequisite elements of social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence, leads to meaningful learning outcomes (Rourke & Kanuka, Citation2009). Also, the reliance in prior Community of inquiry studies on students’ self-reports of learning may suggest a potential and important research limitation (Cho, Citation2011).

Literature bases for hypotheses development

Several studies have reported potential benefits of social presence (Fiock, Citation2020; (Alman et al., Citation2012; Bulu, Citation2012; Filippou, Citation2015; Wei et al., Citation2012; Zetou et al., Citation2011), teaching presence (Antoniou et al., Citation2003; Garrison et al., Citation2010), and cognitive presence in distance learning (Alman et al., Citation2012; Hosler & Arend, Citation2012). The benefits of cognitive, social, and teaching presences have made them a rich topic for researchers in the domain of distance learning.

Cognitive presence and the 21st century curriculum

Although, empirical evidence on the relationship between Cognitive presence and the development of the 21st century curriculum has not been adequately documented, few studies (Hosler & Arend, Citation2012; Robb & Sutton, Citation2014) have tried to espouse the relationship between the overall cognitive presence and the relationship among its four sub-constructs. For instance, in the study of Sezgin (Citation2020) which analysed the cognitive presence in online discussions through content analysis, it is reported that the phase of exploration is the most predominant phase of cognitive presence.

Haynes (Citation2016) also found out that there was no statistically significant relationship between exploration, which is one of the crucial elements of cognitive presence and the development of critical thinking skills, which forms a core of the 21st century curriculum. In the study of Mutlu and Temiz (Citation2013), it came out that cognitive presence is the product of the other two presences, implying that in order to ensure the holistic development of cognitive presence, the establishment of both social and teaching presences is crucial. The study of Maddrell et al. (Citation2011) also reports that only cognitive presence correlates significantly and positively with achievement measures. Bates (Citation2019), further reiterates that as part of establishing the cognitive presence of students, teachers have to skilfully and tactically ask relevant and intriguing questions that are capable of piquing students’ curiosity.

Bate (2019) investigated the relationship between cognitive presence and high-order thinking, and found that high cognitive presence density did not guarantee the promotion of higher order thinking skills but that social presence was positively related to the quality of cognitive presence. Corroborating the above findings, Richardson et al. (Citation2017), through their study established that both social presence and cognitive presence were significantly associated with course satisfaction, but not with teaching presence. Fiock (Citation2020) also identified in his earlier study that the cognition of the student is paramount in developing 21st century skills.

Cognitive presence may be described as a process of practical inquiry distinguished by discourse, and reflection for the purpose of constructing meaning and confirming understanding (Garrison et al., Citation2000). Cognitive presence has been studied less than the two other presences (Arbaugh et al., Citation2008; Hosler & Arend, Citation2012). Bangert (Citation2008) stated that cognitive presence does not co-exist with teaching and social presences; instead, cognitive presence is an outcome of their existence in the learning environment. Garrison et al. (Citation2010) stated that cognitive presence is most closely associated with the process and outcomes of critical thinking and may be the most challenging element to facilitate and measure in an online or hybrid environment.

Cognitive presence is important due to its strong correlation with the learning process (Akyol & Garrison, Citation2008; Citation2011). Cognitive presence has emerged as the strongest predictor of satisfaction, maybe because it does not coexist with teaching and social presences; instead, it is an outcome of their existence in different learning environments (Bangert, Citation2008; Bebetsos, Citation2015). The cognition aspect in the learning context is the main target of the learning process; due to this, students could look at it as the main factor affecting their satisfaction in online or hybrid learning courses. Akyol and Garrison (Citation2011) stated that cognitive presence is highlighted as the purpose for students enrolling on an online or hybrid higher education course. Thus, instructors and administrators of online or hybrid courses should, first of all, take into consideration, the improvement of the cognitive presences, as well as social, and teaching presences in their courses.

Solidifying the basis of this hypothesis, the study of Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009) espoused that the highest frequency of students’ contributions to online discussion are categorized in the lowest level of cognitive presence through exploration (41% - 53% of all posting), whereas the lowest percentage is categorized in the highest-level through resolution (1% -18%). Instructional activities influence the type of contributions students make in online discussions.

On the basis of these, we hypothesise that:

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in higher education curriculum.

Social presence and the 21st century curriculum

Earlier research had established a high correlation between social and cognitive presences (Shea & Bidjeramo, Citation2008), as well as a dynamic relation among the three presences, and a causal relation of social and teaching presence to the perception of cognitive presence. Also, Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009) revealed that there is a positive correlation between social presence and students’ satisfaction with e-learning, and that social presence can be developed through collaborative learning activities. For instance, Fiock (Citation2020) intimated that a congenial social atmosphere is crucial to the development of key skills among learners.

Social presence has been described in online, hybrid, and face-to-face learning processes as the ability of students to project themselves socially and affectively into a community of inquiry (Shea & Bidjeramo, Citation2008). This pre-supposes that when learners fail to recognise social presence in teaching and learning as anticipated issues, it may result in high drop-out rate, low achievement, and low learning satisfaction (Scollins-Mantha, Citation2008). Arguing further, Robb and Sutton (Citation2014) indicated that among all the presences, social presence has been given the most attention in the extant literature which has highlighted the topic of social presence in distance learning. In the literature, social presence in context of teaching and learning has been shown to have an impact on students’ satisfaction (Bulu, Citation2012), student enjoyment (Bebetsos, Citation2015; Mackey & Freyberg, Citation2010), interaction level (Stephens & Roberts, Citation2017, Wei et al., Citation2012), and collaborative learning (Mackey & Freyberg, Citation2010). The importance of social presence in distance education is potentially due to its positive influence of leading students to build a community of learning, and make a connection with classmates (Stephens & Roberts, Citation2017). Relating social presence to the other presences, Dunlap and Lowenthal (Citation2009) intimated that teaching presence is the ability of a teacher or teachers to support and enhance students’ social and cognitive presences through instructional management, building understanding, and direct instruction. Therefore, social presence relates to the other presences.

Based on these arguments, we anticipate that:

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the social presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in higher education curriculum.

Teaching presence and the 21st century curriculum

Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009), through their study, indicated that teaching presence has the tendency to affect students’ learning process through instructional design, discourse facilitation, and direct instruction orchestrated by the teacher. They further indicated that teaching presence is related positively to social presence.

In terms of teaching presence, Jackson et al. (Citation2010) found a correlation between instructors’ actions and students’ satisfaction in online courses; their study further showed that instructors’ actions could have an impact on students’ satisfaction. Dunlap and Lowenthal (Citation2018) stated that teaching presence is the ability of a teacher to support and enhance students’ social and cognitive presences through instructional management, building understanding, and direct instruction. Hence, there is some anticipated level of relationship between teaching presence and the other presences.

Ladyshewsky (Citation2013) also reported that teaching presence appeared to positively influence students’ satisfaction with an online course of study. Teaching presence emphasises the teacher’s role and responsibilities in the learning environment. Some studies have shown that one role of the teaching presence is to facilitate social presence and cognitive presence, both of which emphasise the importance within the distance learning context (Garrison et al., Citation2010). Regarding cognitive presence, assuring this presence in online or hybrid environment can sustain a high level of thinking, and facilitate learning (Kanuka & Garrison, Citation2004).

The results of the study by Swan et al. (Citation2009), showed significant relationships between teaching presence and cognitive presence (p=.001); between teaching presence and perceived learning (p=.03); between teaching presence and satisfaction (p=.011), between cognitive presence and perceived learning (p=.007); between cognitive presence and satisfaction (p=.009), and between social presence and satisfaction (p=.038) (Akyol & Garrison, Citation2011). However, the analysis did not find a significant relationship between social presence and perceived learning.

Furthermore, the authors found out that the development of social presence was contingent on the establishment of teaching presence; that is, social presence did not in itself directly affect cognitive presence but rather served as a mediating variable between teaching presence and cognitive presence. This finding coincides with that of Akyol and Garrison (Citation2011). Similarly, Shea and Bidjermo concluded that the “teaching and social presences represent the processes needed to create paths to epistemic engagement and cognitive presence for online learners.” (p. 14).

In the light of these, we conjecture that:

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the teaching presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in higher education curriculum.

Concept of communities of inquiry (CoI)

A community of inquiry is a group of specialists from a domain gathered to examine an idea, a theme or a topic of common interest through investigation based on dialogue. The most important thing is that this community produces knowledge. An educational community of inquiry is defined as “a group of individuals who collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding” (Garrison, Citation2011, p. 2). The Community of Inquiry (CoI) theoretical framework embraces deep approaches rather than surface approaches to learning and aims at creating conditions to encourage higher order cognitive processing.

Developed by Garrison et al. (Citation2000), the CoI framework is very useful in this study because it espouses the understanding and assessment of how quality face-to-face and online learning environments can affect knowledge-sharing activities. Rooted in social constructivism and Dewey’s (Citation1959) concept of practical inquiry, the framework was developed to augment the interaction among all these critical presences within the academic landscape. It is therefore important to indicate that these elements work in concert to generate a strong learning community that is well-structured and leads to higher-order thinking and learning (Garrison, Citation2015).

This framework has been used in a large number of studies, although most have followed the original methodology of analysing transcripts. This exploratory, interpretivist approach certainly has shown to be fruitful, but it may be possible to move from a descriptive to an inferential approach to studying online communities of inquiry. This would allow for a wide range of studies of online and blended learning across institutions and disciplines. For this to happen, we need to develop a structurally valid and psychometrically sound survey instrument with the potential to expand the study of online and blended learning.

Research methods

Research design

The design for this study was based on predictive-correlational analysis through the lenses of the PLS-SEM analytical tool to espouse the relationships that exist among the three critical presences in relation to the development of 21st century curriculum in the higher education landscape. The correlational analysis was adopted in order to establish clearer relationships and causative effect in order to establish whether these three critical presences contribute to the development of 21st century skills. The choice of this design was informed by its ability to establish the predictive relevance among key variables and their sub-dimensions by way of establishing the exact relationship existing between and among these variables.

Participants

The respondents involved in this study were 807 undergraduate students from a Public University in Ghana (name withheld for ensuring anonymity and confidentiality). The choice of the undergraduates is informed by the reason that they are expected to exhibit these 21st century skills at the job market after school. The sampling frame used for this study was a list of students drawn from the College of Education studies within the same University. The respondents consisted of 533 (66%) males and 274 (34%) females proportionately stratified from the population and climaxed with simple random sampling technique. It is important to indicate that students’ participation in the study was voluntary, and the anonymity of students’ responses and their confidentiality were assured before the instruments were distributed.

Measures and instrumentation

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) survey which was developed by Arbaugh et al. (Citation2008) comprising 34 items was used for data collection purposes. CoI survey obtained information regarding students’ perception in order to measure the three critical presences (cognitive, social and teaching) within the teaching and learning environment. The survey is made up of three sub-sections (corresponding to the three presences earlier established) each of which includes a different number of items that focuses on measuring each kind of presence (cognitive - 12 items, social - 9 items, and teaching presence - 13 items). It is important to indicate that survey instruments of this nature tend to measure the three presences using a fivepoint Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The validity and reliability of the survey instruments were duly established by Arbaugh et al. (Citation2008); the principal component analysis revealed that the data supports the construct validity of the presences as measured by the CoI instrument. The same study also produced Cronbach’s alpha indexes indicative of high internal consistency: teaching presence = .94; social presence = .91; cognitive presence = .95. Likewise, Kuo et al. (Citation2014) in their study confirmed the construct validity of the satisfaction survey, while internal consistency estimated by Cronbach’s alpha measure was also as high as .93. Our study also revealed the following validity and reliability results: teaching presence = .92; social presence = .89; cognitive presence = .93. These results, therefore, confirms a high level of reliability for the data obtained.

From the context of the 21st century skills, the questionnaire was designed to include C- Communication, CNT-Critical Thinking, CRT-Creative Thinking, CT-Collaboration and teamwork, IT- ICT Skills as well as PSS-Personal and Social Skill (Saavedra & Opfer, Citation2012). These dimensions of the 21st century skills have their sub-constructs in the form of items.

Data collection

The CoI survey instrument was distributed to the students during lectures. The data was collected either at the beginning or the end of lectures, depending on the circumstance. The respondents were asked to complete the survey with the highest level of enthusiasm and were admonished to be as realistic as possible. In order to ensure the highest level of ethical adherence, the respondents were made to fill an informed consent form to confirm their willingness to participate in the study. The respondents were also briefed about the purpose and structure of the questionnaire, their rights as research participants, and of any possible risk in their involvement in the research. In order to adhere to the ethical principles of research, the respondents were assured of the highest level of confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. Finally, they were told of their free will to pull out of the research any time they wished to. After reading the informed consent letter, participants were asked to make a choice as to whether they wanted to participate in the study or not. Participants completed the questionnaire in a section-by-section manner. It was established that participants would need approximately, an average of 30 minutes to complete all sections of the instrument.

Statistical analysis

The researchers utilised the partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) technique in analysing the collected data. The choice of the PLS-SEM was premised on two bases: firstly, PLS-SEM allows for the analysis of complex models with multiple constructs, indicators and relationships (Ringle et al., Citation2020). Secondly, the utilisation of PLS-SEM supersedes other analytical techniques in the context of rigorous correlational analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Farrukh et al., Citation2019). It is also noteworthy to indicate that PLS-SEM is a two-phased approach involving measurement models which are used to estimate the performance of the indicators and constructs, as well as structural model used to test the relationships among these constructs. It is also imperative to indicate that PLS-SEM requires that some accepted benchmarks in the measurement and structural models are met before proceeding to discuss and validate the findings. As reported in the resultant tables, the measurement model comprising the indicator loadings (IL), internal consistency, convergent validity and discriminant validity were first evaluated followed by the structural model (Collinearity assessment, coefficient of determination (R2), significance (p: t-statistic) predictive relevance (Q2) and effect size (f2).

We also assessed the measurement model based on the indicator loading procedure (loadings 0.70), internal consistency (through the Cronbach’s alpha or rho A or composite reliability scores 0.70); convergent validity (average variance extracted [AVE] 0.50) and discriminant validity (by means of heterotrait-monotrait ratio [HTMT; ≥ 0.85) (Benitez et al., Citation2020; Hair et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015). It was also reasoned that before the path coefficients could be properly assessed, the indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity of the reflective measurement model should first be examined to ensure they were fit for purpose (Henseler et al., Citation2015). After examining the outer loadings of the latent variables, 3 indicators that form social presence and 2 indicators that form teaching presence were removed because their loadings were less than the 0.4 threshold level (Hair, et al., Citation2013). The remaining indicators were retained because their outer loadings were either 0.7 or higher.

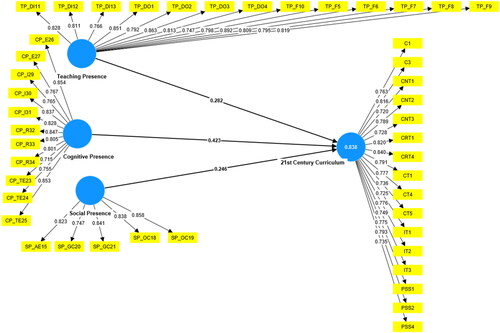

On data inclusion, from , it is evident that some items were deleted after embarking on all the quality checks espoused above, all the remnant data were included for purposes of analysis after deleting the “not-fit-for-purpose items”.

Table 1. Outer loadings, construct reliability and validity and common method bias.

Possible risks and benefits

Even though the questionnaire was quite lengthy and was likely to pose psychological distress to respondents, the items were designed in such a way as to stimulate the interests of respondents and reduce boredom. In terms of the benefits, the outcome of the study would provide some empirical evidence to the participants on how their cognitive, social and teaching presences could be developed. This could be a significant avenue for policy implementation at the institutional level, and the development of strategies to improve these presences in the 21st century at the individual, departmental and national levels.

Results

depicts the real relationship between the components of the CoI Framework and the elements of the 21st Century curriculum.

From , loadings for Teaching Presence (TP) were between 0.747-0.892, loading for Social Presence (SP) ranged from 0.747-0.858, whereas those for Cognitive Presence (CP) were between 0.715-0.854. As a rule of thumb prescribed by Hair et al. (Citation2017), the indicators shown in the Table were reliable; the rest were deleted from the model because they failed to meet the threshold. Furthermore, a cursory check at the values of all the measures of internal consistency shows that the constructs’ internal consistency reliability was achieved because all the values of CA, rho A and Composite Reliability met the accepted threshold of 0.708 or higher (Hair et al., Citation2017). Again, the constructs’ convergent validity, which measured the extent to which the constructs shared mutual relationships, was satisfactory because values of AVE were higher than the minimum 50% threshold (AVE ≥ 0.50). As a rule of thumb heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, less than 0.85 connotes the nonexistence of discriminant validity problems (Henseler et al., Citation2015). indicates that constructs were well distinguished from each other (Italic values ≥ HTMT0.85).

Table 2. Discriminant validity-HTMT.

Focusing on the structural model evaluation, the results were also used for testing the hypotheses undergirding the study. The benchmark in line with relevant thresholds are the correlation coefficients (R = 0.29, 0.49 and 0.50 – weak, moderate and substantial, respectively) (Cohen, Citation1992); coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 – weak, moderate and substantial, respectively); predictive relevance (Q2 = 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 – small, medium and large, respectively); effect size (f 2 = 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 – small, medium and large, respectively) and a significant level of 5% or less or a t-statistic of 1.96 or higher is appropriate for a structural model (Hair et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

, therefore shows the internal consistency indicators (Cronbach’s alpha, rho A and composite reliability [CR] scores) demonstrating a good fit and performance. It is important to state that the results are presented in table formats with strict adherence to the APA Table format. It is also worthy of note that even though most of the results have been presented in Table formats, few of the results have been displayed in figures due to the inherent nature of the analytical framework. Thus, the PLS-SEM.

Describing the variables and their sub-dimensions

This study sought to link the development of 21st century skills with the Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework (including Teaching Presence, Social Presence and Cognitive Presence). From , among the 21st century skills include C- Communication, CNT-Critical Thinking, CRT-Creative Thinking, CT-Collaboration and teamwork, IT- ICT Skills as well as PSS-Personal and Social Skill (Saavedra & Opfer, Citation2012). On the other hand, the sub-dimensions of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework include TP-Teaching Presence, SP-Social Presence and CP-Cognitive Presence.

Measurement model

The results of the measurement model criteria were displayed in and . From , indicator loadings for various constructs that met the threshold of 0.70 or higher were retained, whereas the other items for the constructs were deleted due to relatively low loadings and their inability to enhance the overall model reliability (Hair et al., Citation2017). Again, the results in show that the internal consistency of the constructs was achieved. This is because all the consistency indicators (Cronbach’s alpha, rho A and composite reliability [CR] scores) demonstrated good fit and performance. Eventually, the CR, which is deemed superior for determining the internal consistencies of constructs, had scores for all constructs higher than 0.70. Furthermore, the convergent validity, which measures the degree to which all the constructs achieve mutual relationship through their AVE, was satisfactory in our study (AVE > 0.50).

It can be seen clearly from that the discriminant validity of the constructs has been established. Based on these results, all the constructs were distinct from one another suggesting that the discriminant validity (HTMT ≥ 0.85) of the constructs was achieved.

From , it can be established that

Table 3. Structural model and Hypotheses.

The whole model based on the R2 contributes substantially, 83.8% (R2 = 0.838) of variance in the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. In relation to the predictive relevance (Q2) of the model, all the three presences together largely predict (Q2= 0.822) the development of 21st century skills in higher education curriculum.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive presence (R = 0.423; t = 3.398; p = 0.001) of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. The result of the effect size demonstrates that cognitive presence caused a medium effect (f2= 0.150) on the development of 21st century skills within the context of higher education curriculum.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the social presence (R = 0.246; t = 2.524; p = 0.012) of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. The result of the effect size reveals that social presence caused a small effect (f2= 0.067) on the development of 21st century skills within the context of higher education curriculum.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the teaching presence (R = 0.282; t = 2.711; p = 0.007) of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. The result of the effect size establishes that teaching presence caused a small effect (f2= 0.089) on the development of 21st century skills within the context of the higher education curriculum.

Common method bias

Based on the recommendations of Becker et al. (Citation2015), there were no issues with common method bias (CMB) because the desired thresholds of variance inflated factor (VIF) were met. It is recommended that VIF values in PLS-SEM between 0 and 3.0 or to a maximum of 5.0 suggest non-existence of CMB (Becker et al., Citation2015) (Refer to ). It is important to state that the methods adopted really reflect the results obtained. Hence, the method was fit for purpose.

Discussion

First and foremost, it emanated from the study that there is a statistically significant relationship between the cognitive presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. This finding could be attributed to the fact that one of the hall-marks of a good teacher is the ability to arouse their students’ interest in the course of their lesson (Fiock, Citation2020). Thus, a good teacher should be able to stimulate the interest of their students and arouse their curiosity. By so doing, they are helping their students develop critical thinking skills. One of the techniques, according to Bates (Citation2019), to be used in stimulating students’ interest is by skilfully and tactically asking relevant and intriguing questions that are capable of piquing students’ curiosity. The implication is that teachers should be capable of posing problem-based questions that will trigger their students’ curiosity. This will go a long way to motivate students to explore more contents related to problem-based questions (Fiock, Citation2020); The cognition of the student is paramount in developing 21st century skills. Corroborating the above findings, Richardson et al. (Citation2017), through their study established that both social presence and cognitive presence were significantly associated with course satisfaction, but not with teaching presence. Their study also revealed that both social presence and cognitive presence were significantly associated with course satisfaction, but not with teaching presence.

In support of the same finding, Akyol and Garrison (Citation2011) reported that cognitive presence is important due to its strong correlation with the teaching and learning process. And for that matter, cognitive presence has demonstrated to be the strongest predictor of the satisfaction of learners. We therefore deduce that perhaps, it does not coexist with teaching and social presences; instead, it is an outcome of their existence in different learning settings. The implication may be based on the earlier assertion we made at the initial stages of this study that the cognition aspect in the learning setting is very crucial to the teaching and learning process. The consequence may be that the contemporary students could describe cognitive presence as the main indicator of their online satisfaction which is crucial to the development of their 21st century skills.

Also, as part of developing the cognitive presence of students, they should also be made to effectively utilise a variety of information sources to explore problems posed in the context of their teaching and learning. This, according to Haynes (Citation2016), could be facilitated through brainstorming to find out relevant information from a critical analysis and synthesis in order to enable students deal with content-related issues. What emanated from his study was that there was no statistically significant relationship between exploration, which is one of the crucial elements of cognitive presence and the development of critical thinking skills, which form a core of the 21st century curriculum. Since the world is now in a technological age, it is imperative that 21st century learners should be exposed to online discussions that are valuable in helping them appreciate different perspectives as part of establishing their cognitive presence within the context of the higher education curriculum.

The above observation on cognitive presence confirms the fact that indeed the ability to explore a component of cognitive presence of students is relevant to assisting them to develop a sense of critical thinking skills (Garrison, Citation2015) as a way of enhancing the 21st century curriculum. By clarification, Garrison stated that cognitive presence is most closely associated with the process and outcomes of critical thinking, and may be the most challenging element to facilitate and measure the online or hybrid environment.

Moreover, making resolutions could be described as the application of the information or knowledge encountered by students as part of building their 21st century skills. It is important to state that a relevant idea or knowledge not implemented is as bad as anything. Teachers should be in the position to push their students to implement their learning experiences in order to ensure meaningful learning outcomes. By so doing, the students can describe ways of testing and applying the knowledge created in their respective courses. In support of this occurrence, the study of Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009) espoused that the highest frequency of students’ contributions to online discussion is categorised in the lowest level of cognitive presence through exploration, whereas the smallest percentage is categorised in the highest-level through resolution. The implication of this finding is that instructional activities influence the type of contributions students make in their learning process and that their ability to make strong resolutions is crucial.

Resolution as a tool to developing a sense of critical thinking in students also enables students to develop solutions to course problems that are applicable in practical terms (Bates, Citation2019). Therefore, Lee found out that the relationship between cognitive presence and high-order thinking is more profound at the resolution phase of students’ developing of their cognitive presence. By implication, this will enable students to apply the knowledge created in and out of the classroom. In conjunction with the above, the study of Maddrell et al. (Citation2011) indicates that only cognitive presence correlates significantly and positively with students’ achievement measures.

Secondly, it also came to light that there is a statistically significant relationship between the social presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. We therefore, argue that social interaction is crucial in any human endeavor. In support of this finding, Fiock (Citation2020) intimated that a congenial social atmosphere is crucial to the development of key skills among learners. We, therefore, reason that for effective and meaningful learning to take place, the social variable cannot be ignored or downplayed.

When it comes to establishing the social presence of students within the context of the 21st century, it is important that students get to know their colleagues in their learning expedition, and be able to ascertain the impression of these colleagues in order to create congenial support service that is mutually beneficial to everyone. Consequently, this creates the learning experiences for learners, making them comfortable enough to participate in any form of discussion that pertains to their learning or to other social issues as part of the 21st century curriculum. They should also be exposed to how they could disagree to agree with their co-learners during discussion fora. This will help build a sense of trust among these 21st century co-learners. Such maintenance of trust will help build a sense of belongingness for these young learners, and is likely to help them acknowledge one another’s strengths and weaknesses. Eventually, this will build some level of collaboration among these learners, a collaboration which forms part of team-building as a core 21st century skill.

Our findings are also consistent with those of Richardson et al. (Citation2009) who found that for contemporary leaners to succeed, they should work in teams in order to promote effective collaboration. They indicated that this could be facilitated by designing team-based tasks, problem-based tasks, projects, and small group discussions. Based on the same argument, Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009) revealed that there is a positive correlation between social presence and students’ satisfaction with e-learning, and that social presence can be developed through collaborative learning activities. We therefore reason that e-learning is at the heart of the 21st century curriculum and that institutions of higher education should create the enabling environment to enhance it.

Supporting the findings, several scholars have underscored the role of social presence in the educational landscape. By illustration, Robb and Sutton (Citation2014) indicated that among all the presences, social presence has been given the most attention in the extant literature. The extant literature has highlighted the topic of social presence in distance learning. In the literature, social presence in context of teaching and learning has been shown to have an impact on students’ satisfaction (Bulu, Citation2012), student enjoyment (Bebetsos & Antoniou, 2015; Mackey & Freyberg, Citation2010), interaction level (Stephens & Roberts, Citation2017; Wei et al., Citation2012), and collaborative learning (Mackey & Freyberg, Citation2010).

Lowenthal and Dunlap (Citation2018) also recommended that students should also be made to look for mentors who are ready to sensitise them on the need to communicate with each other through various fora (Peacock & Cowan, Citation2016; Stewart, Citation2017), as well as explaining to the learners the importance of learner-learner interaction in order to help them appreciate their classmates’ perspectives (Stewart, Citation2017). Investigating the relationship between cognitive presence and high-order thinking, Bates (Citation2019), in like manner, found out that high cognitive presence density did not guarantee the promotion of higher order thinking skills but that social presence was positively related to the quality of cognitive presence. We, therefore, reason that indeed, social presence influences the development of 21st century curriculum in higher education. Arguing on similar line, Shea and Bidjeramo (Citation2008) established that a high correlation existed between social and cognitive presences, coupled with a dynamic relationship among these three presences with some level of relation. Based on these observations, we therefore reason that all the three presences have the tendency to influence one another.

Lastly, but not least, it came out that there is a statistically significant relationship between the teaching presence of students and the development of 21st century skills in the higher education curriculum. This finding is not surprising as teaching is directly related to the curriculum. In other words, the core of the curriculum is teaching and learning. Backing this finding, Lowenthal and Dunlap (Citation2018) posited that ensuring students do not get lost in the context of teaching and learning is ensuring that they know what is expected from them, what to do, when to do what, and the teacher’s expectations about the entire teaching and learning process which forms the core of the curriculum. This could be facilitated through instructional management, building understanding, and direct instruction. From this finding, we speculate that for teachers to be effective, they should possess the right pedagogical orientation to underpin their pedagogical practices that will facilitate the creation of meaningful learning outcomes.

As part of establishing the teaching presence of students, the instructor should clearly communicate the necessity of the topic on hand as well as the rationale and goals of the course content of the curriculum. The instructor should also be able to provide clear rubrics on the participation of the learners in the lesson, and provide areas of agreements and disagreements. The implication is that this will enable teachers to clearly guide students to understand what is being taught in order to clarify their doubts. Buttressing the same point, Rourke and Kanuka (Citation2009) through their study, indicated that teaching presence has the tendency to affect students’ learning process through instructional design, discourse facilitation, and direct instruction orchestrated by the teacher. They further indicated that teaching presence is related positively to social presence.

In addition to establishing the teaching presence of students, the instructor should be able to actively engage students in the teaching and learning process in order to promote effective and productive dialogue. This can be reinforced through the development of a sense of belongingness and a community of practice (Garrison, Citation2015). Impliedly, this will go a long way to allow learners explore new concepts and ideas, as well as focus their discussion on relevant issues in the learning process. By this, the instructor is able to help the learners to identify their strengths and weaknesses in relation to the course objectives. This may also enable the instructors to provide feedback on time.

Reinforcing the findings, Ladyshewsky (CitationCitation2013) also reported that teaching presence appeared to positively influence students’ satisfaction with an online course of study. Teaching presence emphasizes the teacher’s role and responsibilities in the learning environment. Some studies have shown that one role of teaching presence is to facilitate social presence and cognitive presence, both of which emphasize their importance in the distance learning experience.

Contributions of this paper

Within the context of the Ghanaian higher education landscape, and as far as the researchers are concerned, this is a maiden study on the utilisation of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model in enhancing teaching and learning, especially, using the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to carry out the data analysis. Also, students, faculty and curriculum developers in institutions of higher learning would be the direct beneficiaries of this study. This is attributed to the fact that students’ awareness will be created on the various dimensions that inform their effective learning with recourse to the CoI model. The outcome of this study will help faculty to take into account the various dimensions of the teaching and learning processes so that they could implement these dimensions in their teaching in order to promote meaningful learning outcomes. Lastly, but not least, curriculum developers would be able to incorporate the CoI model and its assumptions into the higher education curricula in order to promote effective teaching and learning outcomes. The results from the study provide significant insights into how these presences from the context of the communities of inquiry influence the development of the 21st century curriculum by way of developing the 21st century learner.

Conclusion

It is very imperative to indicate that the key to creating a purposeful, exciting, creative, dynamic, insightful, worthwhile, cohesive and meaningful educational outcomes is to embrace the concept of communities of inquiry, and the ability to effectively integrate the cognitive, social and teaching presences of the 21st century learner. And that each of these presences evolves and manifests itself in different ways either within an online or face-to-face context, especially, with reference to the 21st century higher education curriculum.

It is the interface of these critical presences (teaching, social and cognitive) that defines the learning experience in the context of the blended learning environment. It is imperative to intimate that the hotspot of learning happens at the point where the right levels and mix of these “presences” are achieved to stimulate active engagement and, deep and meaningful learning. The underlying principle of the COI framework is rooted in the belief that a community of learning that harnesses collaborative synergy will bring out the best of student engagement and active learning. It is therefore scholarly to intimate that the model of communities of inquiry requires the 21st century learner to articulate both their understanding of and drawing of meaningful ideas from the learning experiences they encounter, and probably, be able to critique the ideas of others. However, the preponderance of data indicates that the extent to which students engage in these dialogical activities is grossly overestimated.

Implications for theory, policy and practice

Curriculum developers should enhance a holistic development of the higher education curriculum by ensuring that all the presences (the social, cognitive and teaching) are established within the higher education landscape.

Lecturers should endeavor to ensure that at least, each of these presences is established in their lessons in order to facilitate the promotion of effective teaching and learning outcomes.

The assumptions underpinning the Communities of Inquiry model should be embraced by educational institutions, and be incorporated into the development of 21st century curricula.

21st century learners should be exposed to online discussions that are valuable in helping them appreciate different perspectives as part of establishing their cognitive presence within the context of the higher education curriculum.

The 21st century learner should also be made to utilise effectively a variety of information sources to explore problems posed in the context of teaching and learning.

21st century learners should be exposed to online discussions that are valuable in helping them appreciate different perspectives as part of establishing their cognitive presence within the context of the higher education curriculum.

Students’ assessment should also focus on higher-order thinking capabilities by way of ensuring their holistic development.

Limitations and suggestions for further studies

The study relied on self-reported measures through questionnaires. The inherent shortfalls of lack of expression by the respondents become inevitable. Other relevant information may not have been captured due to the close-ended nature of the collection instrument. Even though such limitations may have been addressed through validity and reliability tests, an approach that grants respondents the luxury of being assertive and thorough in the responses that may help improve understanding of how the cognitive, teaching and social presences are established. Therefore, we suggest that a more comprehensive mixed method approach will be ideal for investigating this phenomenon under study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mumuni Baba Yidana

Mumuni Baba Yidana is a Senior lecturer in Curriculum Studies at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Curriculum Development, M. Phil in Curriculum Studies, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Social Studies, which was concurrently earned with a Diploma in Economics. At the moment, the author is an Associate Professor of Curriculum Development with specialization in Economics. His research interests include Curriculum and Teaching in Economics, Teacher Education in Economics, Economics of Teacher Education, In-service and Pre-service Economics Teachers’ Efficacy Beliefs and Effective Teaching, and Economics Teachers’ Metacognitive Skills, among others. He has supervised and assessed a number of graduate theses in Curriculum and Teaching in Economics. The author is the immediate past Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Education of the aforementioned University.

Gabriel Kwasi Aboagye

Gabriel Kwasi Aboagye is a Business Educator at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, who holds PhD in Management Education, MPhil in Curriculum Studies and a Bachelor’s Degree in Management Education. He started his teaching profession as an Assistant Lecturer in the aforementioned University in 2017. He is currently a Lecturer at the same Department with research interests in Research-teaching Nexus, Management Education as well as Pedagogic Research. He has served as a member of his Faculty Board as well as the Departmental Quality Assurance Officer. As part of his community and outreach services, he has served and is still serving as a Chief Invigilator and Course Co-ordinator for some of the courses in the University of Cape Coast outreach services.

References

- Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), 3–22.

- Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. (2011). Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: Assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01029.x

- Akyol, Z., Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2009). A response to the review of the community of inquiry framework. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education/Revue Internationale du e-Learning et la Formation à Distance, 23(2), 123–136.

- Alman, S. W., Frey, B. A., & Tomer, C. (2012). Social and cognitive presence as factors in learning and student retention: An investigation of the cohort model in an iSchool setting. Journal of Education for Library & Information Science, 53(4), 290–302.

- Antoniou, P., Gourgoulis, V., Trikas, G., Mavridis, T., & Bebetsos, E. (2003). Using Multimedia as an instructional tool in Physical Education. Journal of Human Movements Studies, 44, 433–446.

- Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the community of inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3-4), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

- Bangert, A. (2008). The influence of social presence and teaching presence on the quality of online critical inquiry. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 20(1), 34–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03033431

- Bates, A. W. (2019). Teaching in a digital age (2nd ed.). Tony Bates Associates Ltd.

- Bebetsos, E, Assoc. Prof., School of Physical Education & SportScience, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, [email protected]. (2015). Prediction of participation of undergraduate university students in a music and dance master’s degree program. International Journal of Instruction, 8(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2015.8213a

- Becker, J.-M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Völckner, F. (2015). How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Marketing Letters, 26(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9299-9

- Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., & Schuberth, F. (2020). How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory is research. Information & Management, 57(2), 103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.05.003

- Bulu, S. T. (2012). Place presence, social presence, co-presence, and satisfaction in virtual worlds. Computers & Education, 58(1), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.024

- Cho, T. (2011). The impact of types of interaction on student satisfaction in online courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 10(2), 109–125.

- Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

- Dewey, J. (1959). My pedagogic creed. In J. Dewey (Ed.), Dewey on education (pp. 19–32). Teachers College, Columbia University. (Original work published 1897).

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J, University of Groningen. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Dunlap, J., & Lowenthal, P. (2009). Tweeting the night away: Using twitter to enhance social presence. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2), 129–135.

- Dunlap, J., & Lowenthal, P. (2018). Online educators’ recommendations for teaching online: Crowdsourcing in action. Open Praxis, 10(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.1.721

- Farrukh, M., Lee, J. W. C., & Shahzad, I. A. (2019). Intrapreneurial behavior in higher education institutes of Pakistan: the role of leadership styles and psychological empowerment. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 11(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-05-2018-0084

- Filippou, F. (2015). The first woman’s dancer improvisation in the area of Roumlouki (Alexandria) through the Dance “Tis Marias”. Ethnologia, 6, 1–24.

- Fiock, H. S. (2020). Designing a community of inquiry in online courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 134–152.

- Garrison, D. R. (2015). Thinking collaboratively: learning in a community of inquiry. Routledge.

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the twenty-first century. RoutledgeFalmer.

- Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1-2), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.003

- Garrison, D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 31–36.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019a). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019b). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Haynes, F. (2016). Trust and the community of inquiry. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1144169

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hosler, K. A., & Arend, B. D. (2012). The importance of course design, feedback, and facilitation: student perceptions of the relationship between teaching presence and cognitive presence. Educational Media International, 49(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2012.738014

- Jackson, L. C., Jones, S. J., & Rodriguez, R. C. (2010). Faculty actions that result in student satisfaction in online courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 14(4), 78–96.

- Kanuka, H., & Garrison, D. R. (2004). Cognitive presence in online learning. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 15(2), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02940928

- Kibuku, R. N., Ochieng, D. O., & Wausi, A. N. (2020). e-learning challenges faced by universities in Kenya: A literature review. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 18(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJEL.20.18.2.004

- Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E., & Belland, B. R. (2014). Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 20, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.001

- Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2013). Instructor presence in online courses and student satisfaction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2013.070113

- Lipman, M. (1991). Thinking in Education. Cambridge University Press.

- Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in Education (2nd Ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Lowenthal, P., & Dunlap, J. (2018). Investigating students’ perceptions of instructional strategies to establish social presence. Distance Education, 39(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1476844

- Mackey, K. R. M., & Freyberg, D. L. (2010). The effect of social presence on affective and cognitive learning in an international engineering course taught via distance-learning. Journal of Engineering Education, 99(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2010.tb01039.x

- Maddrell, J. A., Morrison, G. R., & Watson, G. S. (2011 Community of inquiry framework and learner achievement [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Association of Educational Communication & Technology, Jacksonville, FL. November).

- Mutlu, M., & Temiz, B. K. (2013). Science process skills of students having field dependent and field independent cognitive styles. Educational Research and Reviews, 8(11), 766–776.

- Peacock, S., & Cowan, J. (2016). From presences to linked influences within communities of inquiry. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 17(5), 267–283.

- Richardson, J. C., Ice, P., & Swan, K. (2009). Tips and techniques for integrating social, teaching, & cognitive presence into your courses [Paper presentation]. Poster session presented at the Conference on Distance Teaching & Learning, Madison, WI.

- Richardson, J. C., Maeda, Y., Lv, J., & Caskurlu, S. (2017). Social presence in relation to students’ satisfaction and learning in the online environment: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.001

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

- Robb, C. A., & Sutton, J. (2014). The importance of social presence and motivation in distance learning. Journal of Technology. Management & Applied Engineering, 31(1-3), 1–10.

- Rourke, L., & Kanuka, H. (2009). Learning in communities of inquiry: A review of the literature. Journal of Distance Education, 23(1), 19–48.

- Saavedra, A. R., & Opfer, V. D. (2012). Learning 21st century skills require 21st century teaching. A Global Cities Education Network report and Scale Development. Asia Society.

- Scollins-Mantha, B. (2008). Cultivating social presence in the online learning classroom: A literature review with recommendations for practice. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 5(3), 1–15.

- Sezgin, S. (2020). Effects of cognitive style to learner behaviours in online communities of practise. Anadolu University.

- Shea, P., & Bidjeramo, T. (2008). Community of inquiry as a theoretical framework to foster “epistemic engagement” and “cognitive presence in Online Education [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

- Stephens, G. E., & Roberts, K. L. (2017). Facilitating collaboration in online groups. Journal of Educators Online, 14(1), 1–16.

- Stewart, M. K. (2017). Communities of inquiry: A heuristic for designing and assessing interactive learning activities in technology-mediated FYC. Computers and Composition, 45, 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2017.06.004

- Swan, K., Garrison, D. R., & Richardson, J. C. (2009). A constructivist approach to online learning: The community of inquiry framework. In Information technology and constructivism in higher education: Progressive learning frameworks (pp. 43–57). IGI global.

- Vernadakis, N., Antoniou, P., Giannousi, M., Zetou, E., & Kioumourtzoglou, E. (2011). The effect of information literacy on physical education students’ perception of a course management system. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2010.542160

- Vernadakis, N., Kouli, O., Tsitskari, E., Gioftsidou, A., & Antoniou, P. (2014). University students’ ability-expectancy beliefs and subjective task values for exergames. Computers & Education, 75, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.02.010

- Wei, Chun-Wang, Chen, Nian-Shing, Kinshuk,. (2012). A model for social presence in online classrooms.Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(3), 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9234-9

- Zetou, E., Amprasi, E., Michalopoulou, M., & Aggelousis, N. (2011). Volleyball coaches behavior assessment through systematic observation. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 6(4), 585–593. https://doi.org/10.4100/jhse.2011.64.02