Abstract

The US-China trade War in 2018 is one of the 595 documented trade-related disputes reported by the WTO since 1995. Despite the January 2020 agreement between the two countries, the causes of the trade wars appear implicated in international economic relations between the two world economies. In this trade war, the dominant narratives revolve around currency pegging, trade imbalance, intellectual property rights, and most-favoured-nation status as factors propelling the US-China trade war. While these factors have drawn significant attention to scholarly study, they have yet to yield reliable insight into the role of globalisation and technology. With the help of explanatory research design, the study offered an understanding of why the US-China trade war results from the structural changes of economic globalization facilitated by technology diffusion that shift economic growth benefits from the Global North to the Global South with internal structural implications for the US.

Introduction

Trade wars among nations have existed since ancient times. Accordingly, Hur (Citation2018) notes that a trade war is not the same as a trade dispute. But, trade wars originate in trade disputes. Trade disputes are amenable to being justiciable under an agreed normative framework like the WTO, while a trade war between the US and China exists within and outside an established framework of WTO. For Lai (Citation2006), most times, trade is caused the moment a country’s economic growth in international trade becomes a concern at the global and regional levels. This concern that Falkenberg (Citation2021) stated applies to China following the opening up economic policy, reforms, and growth in the 1980s. China’s policy Lardy (Citation2001) preceded China’s forced commitment to WTO accession and liberalization, resulting in a complete transition to a more market-oriented economy.

The transition gave the EU considerable enthusiasm for China’s constructive role in global trade (Kim, Citation2004), and China became deeply integrated into the world economy and became the biggest gainer of economic globalization (Feng & Huang, Citation1997). In the United States, former US President Bill Clinton is optimistic that China’s WTO membership will bring competition and promote a more rapid and healthy development of China’s national economy (Lardy, Citation2001). President Clinton’s notion forms the West’s lesser concern about China, which turned out to be a mistaken assumption (Falkenberg, Citation2021). The first false assumption Shaffer and Gao (Citation2021) asserted gave the West hope that China’s deeper WTO commitment to liberalization would allow Western countries to transform China and integrate it into a liberal and global capitalist economy. Second, some European and US policymakers did not see China as a major competitive threat to developing countries because of China’s labour-intensive manufacturing. For instance, studies from (Shafaeddin & Shafaeddin, Citation2002; and Yang, Citation2006) collectively predicted that China’s labour-intensive advantage would likely affect the entire technological spectrum of global trade.

So, when China learned to defend its interests through the WTO and use the rules against the US and the EU (Shaffer & Gao, Citation2021), the West’s optimism about China’s liberalization faded, and, not surprisingly, the 2018 US-China trade war began as a protest. The US protested against the WTO and China regarding China’s WTO benefits, which had remained unchecked for years. The protest is premised on Trumponomics, an ‘America-first’ initiative and economic agenda focusing on deregulating the US economy, ensuring tax cuts and protectionism measures, including trade deficits with major US trading partners, notably China. Trumponomics believe that ‘China’s international integration has not liberalized its political or economic system’. Given Trumponomics, China is a ‘revisionist power’ and an adversary to be approached as a strategic competitor (Lum & Weber, Citation2021). Trump’s claims of China’s excessive utilization fueled new arguments against modernization theory (Lukin, Citation2019) that worry major partners because China safeguards its domestic market against foreign competition. Moreover, China provides subsidies for domestic companies and facilitates their exports exports, including currency devaluation (Kapustina et al., Citation2020).

Studies in our dominant literature showed how economic and political motivations caused trade wars, which revolved around the Yuan pegging and manipulation (Plender, Citation2019; Rodrik, Citation2018). Other research we cited is the historical US trade imbalance with China since 1986 (USCB, Citation2020; Wu, Citation2020) while pointing fingers at WTO regulatory inadequacies on global trade governance (Sheng et al., Citation2019; Solis, Citation2014). Further study identified the US accusation of China on intellectual property rights (IPR) (Yongding, Citation2018) because it raised national security questions in the US. The consensus is that IPR and patent issues are partly attributed to the US Most-Favoured-Nation’s (MFN) status to China by the previous US administration (Landler, Citation2005). Arguably, China’s MFN status has undermined the US economy, patent rights and innovation (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022; Zubascu, Citation2020).

These studies remind us about the escalating cycle impacts of the US-China trade war on the world’s two largest economies because of their significant contribution to global trade. The escalating tariff retaliation between the US and China on industries, businesses, and consumers and other harmful trade discrimination policies portend a risk and frontal challenges to the global trade order. Research by (Rodrik, Citation2018, Lawrence, Citation2018; Shaffer, Citation2021) has demonstrated how US-China trade largely undermines the WTO’s rule-based multilateral trading system and affects the global growth prospects of countries with the worst and darkest economic scenarios (Steinbock, Citation2019). As Yao (Citation2018) noted, the US-China trade war has disrupted world trade, costing the world more than a US$430 billion loss in GDP.

However, the above scholarly literature appears to have not captured the role of the structural impact of economic globalization and technology. For us, structural economic globalisation and technological impact remain under study, which forms the gap of this study and points to the cause of the US-China trade war and why, generally, trade wars will remain unending. The US-China trade war, we argued, lies in economic globalization, which has undergone structural changes in recent times. We noted that the structural changes in economic globalization occurred in technology after China’s economic reform and WTO progress and accelerated China’s economic growth. Economic globalization underscores the expansion and integration of economic, political, social, cultural, technological, financial, and communication spheres to reduce cost and distance. The efficient and greater internalization of these spheres of globalization, notably economic globalization aspects of trade liberalization, has been accelerated by technological growth. So, greater globalization with the help of technology from the Global North into countries of the Global South, notably China, allows for the inflow of foreign capital, technology-IPR, and management know-how. These resources enabled China’s entrepreneurial activity to turn its vast labour resources and population size into rapid economic growth that later undermined the Global North-driven dominance of economic globalization and technological advancement.

First, technology is an innovative technique to advance a product, instrument, or a new idea practically applied to solve a problem and improve societal needs. Technology ideas or innovations developed by an individual, organization (s), or country are transferable scientific knowledge under favourable terms between parties. Yet the utilization of technology and its idea using available land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship: factors of production by countries can gain global market advantage. So, at the initial stage of technology growth, the Global North subsidized and transferred technological ideas to the Global South as a component of the ‘new international order’ (Bauer, Citation1977). The ‘new international order’ known as economic globalization and its aspects of trade integration spread economic and technological progress from the West to economically less advanced countries such as China. Thus, the Global North dominated technology and economic globalization and advocated new technology transfer and trade liberalization. Their dominance was through the instrumentality of international trade institutions such as the World Bank, IMF, and GATT/WTO. As such, countries from the Global South struggled to fit into the economic globalization framework of these institutions and then experienced marginalization (Khor, Citation2000).

Understandably, Khor (Citation2000) reiterated that the very uneven process marginalization of the Global South in economic globalization has changed due to a new technologically induced economic globalization trend. As Arora (Citation2022) reminds us, the technology and economic globalization of the 1980s have evolved as twin phenomena. The evolvement brought structural changes to these two twin phenomena and re-distributed the benefits of economic globalization from the US to China. Therefore, the US-China trade war is a product of the re-distributional consequences of economic globalization breaking down national economic boundaries and barriers caused by dynamic technological changes. We firmly believe that breaking down national economic barriers changed the benefits of trade and investment between the US and China. The changes greatly induced economic dislocations of jobs and manufacturing products in the US and some developed economies (Oramah & Dzene, Citation2019), mainly facilitated by technology diffusion. Scholars see technological diffusion as technological transfer that enhances the economic globalization of technology from one country to facilitate changes in the global economic structure of another (McMahon, Citation2010; Muroyama & Stever, Citation1988) to ensure the immobility in production in previously unthought-possible ways (Madden, Citation2019).

Given the above, we define the economic globalization of technology as the dynamic changes in economic activities, such as in areas of manufacturing and consumption of goods and services, due to technological innovation that affects holistic economic activities in areas of trade and investment between countries while ensuring efficiency in the affairs of man. The negative is that such changes in economic activities come with the burden of globalization of technology by some advanced economies that continue to exploit developing countries (Archibugi & Pietrobelli, Citation1999). The implication is that it results in the elephant curve of steadily deepening inequality (Saez & Zucman, Citation2022) in almost all aspects of exploited countries’ economic development (Tica et al., 2021). The positive is that economic globalization of technology led to the diffusion of technology that shifted the world economy from the West to Asia and favoured first the Chinese and the Indians, among others (Lamont, Citation2020; Tonby et al., Citation2019) due to China’s economic reform and the greater diffusion of US investments in China since 2000 (Wu, Citation2020).

We understand that the economic globalization of technology as a new taxonomy (Archibugi & Pietrobelli, Citation1999) created a new type of global interaction between peoples, territories, and organizations (Leong, Citation2017). It also increases mutual interaction and rearranges and alters the interaction of time, space, and power (Yilmaztürk, Citation2019). At the level of economic globalization of technology, economic interaction rapidly spread due to the diffusion of new technology (Archibugi & Iammarino, Citation2002; Eugster et al., Citation2019) from developed economies to emerging markets. Even though the technology was employed in different countries (Mukoyama, Citation2003), it changed the economic structure of countries like China after her opening to international trade (Perkins & Neumayer, Citation2005). It attracted foreign investments, firms’ entry, technology, and knowledge transfer (Skare & Soriano, Citation2021). Above all, it helped increase the share of countries’ economic growth and global potential and lift global living standards in China, among other things (Eugster et al., Citation2019).

As we discussed, China’s economic globalization and technological benefit facilitated her ‘partial’ integration into the international economy and allowed China’s unorthodox economic practices (Rodrik, Citation2018) to safeguard its local markets, resulting in Trumponomics in 2018. Trumponomics logic was an allegation against China’s foreign policy of cozying up and pressuring American companies to turn over sensitive technology data to Chinese partners (Mason, Citation2018; Tejada, Citation2018; Wroughton & Mason, Citation2017). Thus, China was accused of engaging in advanced technology theft for duplication of all kinds of innovative products of US companies (Dhue & Tausche, Citation2018; Swanson, Citation2017). We observe that a greater part of the US technology duplication came during the US technological diffusion and industries in China at an early stage, as well as the Chinese government’s high investment in science and technology (Steinbock, Citation2018). US technological diffusion yielded a significant US trade deficit with China (Lamont, Citation2020) and caused job displacement across the US (Scott & Mokhiber, Citation2020). Although the greater convergence of technological breakthroughs (Jayakumar (Citation2020) and economic globalization brought efficiency and productivity, trade liberalization brings competitiveness (Perkins & Neumayer, Citation2005; Reddy, Citation2017) that has become a striking development aspect in the US and China trade war.

The study demonstrates how the economic technology of globalization and its structural changes have redefined and redirected economic globalization benefits from the West to Asia, thereby resurrecting US protectionist measures against China. To that end, we provide further insights into why the contemporary economic technology of globalization is a win-win for emerging economies and why trade wars will persist because of growing innovation and economic integration from emerging economies. Thus, how does the economic technology of globalisation contribute to the cause of the US-China trade war, and why is China’s globalization of technology different? These background questions will form the substance of this paper, which is composed of five parts. In the first part, the study presents a review of related literature. In the second part, the study began by providing answers to the question and explaining how to understand the globalisation of technology. Thirdly, the study explained China’s economic globalization and why China’s economic globalization heightened the trade war. In chapter three, we provided two outcomes of where the trade war problems started between China and the US. Next, the study shows the structural evidence of transitional changes that are taking place/shifting and compares the effect of the structural changes in China and the US and their re-distributional consequences, representing the internal structural dilemma in the US. Lastly, the study concludes with a few recommendations.

Literature review

We grouped the dominant literature on the US-China trade war into four, namely;

Yuan-dollar divides

The dollar-yuan controversy has contributed to trade war debates as critics view Yuan pegging as a deliberate weapon by Beijing in trade with Washington (Horowitz, Citation2019; Imbert, Citation2019; Kollewe, Citation2019). The Beijing Yuan pegging criticism by liberal commentators in the US (Rodrik, Citation2018) has led to a currency war (Plender, Citation2019) between the US and China. It has also informed the US to label China as a currency manipulator, making the US use measures like the US Omnibus Trade Act (OTA) of 1988 to identify and respond to countries engaging in unfair trade with the US. The US OTA identified major currency manipulators who are trade partners of the United States using one of the three guiding rules in the Congress Report 1988 (Birenbaum, Citation1988).

First, trading partners should not intervene in foreign exchange markets with the US under the US OTA. Next, there should not be a significant trade surplus with the US, and lastly, the trading partners have a material global current account surplus. Since 1988, the US has used the exchange rate rule policies to sanction Japan and Taiwan in the 1980s and China from 1992 to 1994 as each country substantially reformed its foreign exchange regimes (Scott, Citation2010, Crutsinger, Citation2021). However, when Trump’s administration named China a currency manipulator and imposed tariffs, policymakers viewed it as immaterial because, based on history, China, since 1979, has never conceded to trade threats from the US (Zhang, Citation2018) despite her intervention in the foreign exchange market. Even at that, going by history, as in the 1990s, the US strategic policy could not slow China’s economic growth and reduce trade deficits with the US. The implication is that China’s trade surplus has boosted China’s global current account surpluses and has become so significant that the current account surpluses mirror the overall US current account deficits (Scott, Citation2010).

In the mirror of the US OTA rules under the Trump administration, China has engaged in unfair trade practices and, subsequently, the imposition of tariffs of 25 percent on products covering roughly $34 billion of US imports from China as of July 2018 and $16 billion of imports in August (Bown, Citation2022). While tariff imposition affected both countries, the US’s legitimate concern raised serious questions about China’s commitment to WTO membership. As Rodrik (Citation2018) answered, it does not mean China’s credit subsidies, state-owned enterprises, domestic content rules, selective protection, and technology-transfer requirements policies did not violate WTO rules. While it does, Trump’s tariffs and taxes are a violation between trading partners under the WTO rules when the amount targeted is higher than the agreed tax commitments between the two countries and is solely targeted at one country. On that, China insists that the enacted tariffs law in June and September of 2018 in the US of $300bn worth of goods is against $2000bn in annual tariffs trade agreed with the United States (BBC., Citation2020).

The above debate between Beijing and Washington is that the expected tariffs on Chinese products are due to the depreciation in its currency, which is an effective way to reduce the effects of unilateralist and trade-protectionist measures by the United States. While the US action is justified, China considered the accusation of US currency manipulation to be destroying the international financial order. However, financial experts see Beijing’s surprise devaluation as a move by the government to fix the currency value instead of allowing the market forces to determine the exchange rate (Allen, Citation2015). China’s violation of the WTO rules reminds us that a low exchange rate makes Chinese products cheaper for consumers worldwide. Yet, a cheaper Renminbi means higher inflation and a greater burden for Chinese companies that own money in dollars (Irwin, Citation2015). Overall, currency manipulation harms businesses and consumers because of the possibility of rising inflation to the point where importations become more expensive due to the higher cost of commodities (Swanson et al., Citation2019).

Whereas international law allows countries to have the right to manage their currencies, other nations can checkmate those rights through international agreements (Palmer, Citation2012). For instance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Articles of Agreement prohibit countries from gaining an advantage in managing their currency. Yet, China’s exchange rate policy has been controversial. The controversy underlines why most of the Chinese exchange rate policy has been severely attacked by EU and US countries. The presumption is that the Chinese authorities’ devaluation exercise on its Renminbi put the Chinese market at a favourable advantage for the export market against the US and the EU. The presumption in economies boiled down to the narrative that the exercises boost trade exports and demand for Chinese goods. So, any currency devaluation leads to the low value of a country’s currency, which hampers local manufacturers in other destination countries. Thus, China’s misaligned exchange rate regime brings cheap Yuan that floods Chinese exports into the US markets and further strengthens US trade deficits with China. However, countries’ exchange rate strategy, even in the United States, serves as an intervention policy in domestic markets (Freytag, Citation2008).

Undoubtedly, there is compelling evidence that China is devaluing its Renminbi (BBC News, Citation2019; Doerer, Citation2015; Irwin, Citation2015). The first devaluation was 21% in 1989, and the largest against the US dollar was 33% in 1994 (Doerer, Citation2015; Geiger & Pennings, Citation2021). Since devaluation makes exports cheaper and more competitive against foreign manufacturers, the US position on China’s monetary policy conduct provides a shred of evidence that links currency devaluation and its effect on soaring US bilateral trade deficits with China and a significant decline and loss of manufacturing jobs in recent years (Morrison & Labonte, Citation2013). The US claims have been a weak position and less straightforward argument (Freytag, Citation2008) because of the complex meaning of manipulation under the 1988 US OTA. The US OTA has a different definition of manipulation that focuses on the action that impedes or gains effective balance of payment adjustment or competitive advantage. The differences offer China the opportunity to counter by insisting that it has no obligation to resist market pressures by pushing the Yuan down. Besides, China meets one: bilateral surplus criteria of three US 2015 Trade Enforcement Act not to be tagged a manipulator (Setser, Citation2019)

Historically, currency manipulation has been a major concern in international trade, starting in the 1930s when countries employed unfair exchange rate practices to boost trade exports and address rising negative economic situations. Then, the defence against unfair exchange rate practices is that currency manipulation through exchange rates does not determine trade gains with other countries. The determinants of the real exchange rate and the value of each country’s currency are the invisible hands of market forces that give rise to the volume of trade relations, making a case for currency manipulation an open debate. The government can influence those invisible hands of demand and supply through regulatory policy using different types of exchange rate manipulation. To that end, currency manipulation using a ‘real exchange rate’ type means the volume of goods and services on foreign currency traded domestically differs from the currency manipulation on the ‘nominal exchange rate’ type, which tells how much similar commodities are exchanged in a foreign country. Overall, determining the impacts of unfair currency manipulation falls within three exchange rate regimes: floating regime, fixed regime, and pegged float regime.

The differences with any exchange rate regime further influence the nominal exchange rate type in foreign markets. Each regime has its positive and negative economic implications. Like other Asian countries, China has frequently adjusted its exchange rate regime since 1994 by favouring two of three exchange regimes to attract foreign demand for Chinese goods and sustain employment growth. The two favoured are the ‘fixed and the peg’ systems while keeping the ‘floating’ regime closed (China Power Team, Citation2020; Lafrance, Citation2008; Morrison & Labonte, Citation2013; Ping, Citation2011). In the three regimes, government influence and intervention in the market are less prevalent in the floating regime due to consumers’ preferences, leading to a drastic increase in demand and supply. In the remaining two, the government often intervened by buying foreign currencies, selling, or raising or lowering the currency’s price, thereby increasing the country’s net exports (Morrison & Labonte, Citation2013). The practice, notably fixed regime measures by the Chinese government in the last two regimes, is a bone of contention between the US and China: two competing dominant market currencies. Even though the Chinese claimed to have abandoned her fixed regime in 2005, the controversial ‘managed floating exchange rate system’ allowed Beijing to maintain a tight rein or control on the Yuan by pegging a daily central parity rate against the US dollar and limiting changes to its values to within 2 per cent (Zhou, Citation2021)

Nonetheless, scholars and economists in international trade have identified the practice of currency manipulation among WTO members as a norm rather than an exception. In their separate views, Cline and Williamson (Citation2010), Howard (Citation2013), and Weisman (Citation2015) identified many countries in the Pacific, like Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Singapore, among others, that are guilty of currency manipulation against the United States. Yet, there is no trade war between the US and these countries, perhaps because currency manipulation issues surrounding the United States and China trade war are significant because of the trade volume and its deficits with China. In that respect, some scholars point to how the endogenous trade imbalance structure (Li et al., Citation2018) narrative linked to currency manipulation escalated the US-China trade dispute in 2018 (Rushe & Kuo, Citation2019).

Trade imbalance

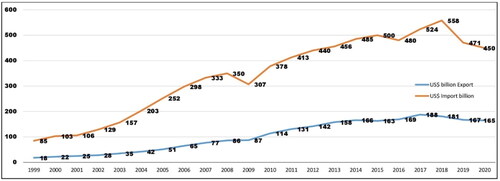

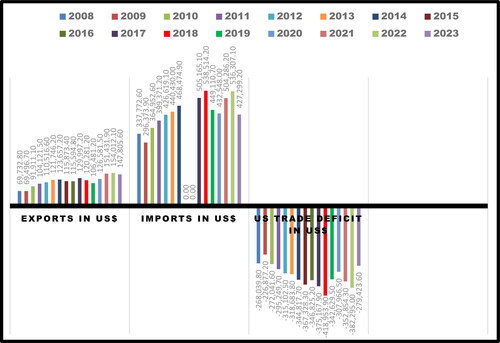

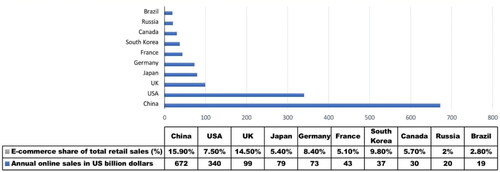

Historically, high trade imbalances and the widening gap between the United States and China have existed for years, as detailed by the US Census Bureau (USCB) since 1986. shows a 17-year annual trade imbalance from 2005 to 2019, indicating the US’s high volume of imported products dependent on China until July 2020, valued at $163,336.9 billion. So, while the US import deficit stood at $221,864.8 billion, exports were $58,527.8 billion (USCB Citation2020). The report sums up the view of Danforth (Citation1993) that despite being one of the world’s largest economies, the US runs a dangerously decades high and continually trade imbalance with China on many categories of goods. A closer look at shows a significant US trade imbalance increased from -268 039.80 in 2008 to -418, 953.90 in 2018. Perhaps this highest trade deficit in 2018 might have propelled Trumponomics. From 2019 to 2024, the US trade deficit reduced, with the lowest in 2020 at -307,966.50 and further in 2023 at -279 423.60. However, in 2022, the US had the highest export to China at $154,012.10. In the same years, the US had the second highest US imports from China, but there was a decline in imports from China in 2023. While this is a sign of the US de-linking from the Chinese market, it means rising costs for US consumers and companies due to the absence of cheap production costs that are not from China.

Figure 1. Annual US-China trade years 2008–2023. Source: The author. Data from the USCB (Citation2024).

Amadeo (Citation2020) identified the major categories of the US import deficit of goods as machinery, electronics, vehicles, and pharmaceuticals, and their biggest subcategories of imports from China are computers, cell phones, apparel, toys, and sporting goods. For China, top imports from the US are Soyabean, port, cotton, seafood, steel, dairy products, fruit, cereals, automobiles, chemicals, medical equipment, and energy products (Yu & Leong, Citation2018). Undoubtedly, China’s role in interlinking global value chains for multinational industries in cheap Labour, raw materials, intermediate products, and product demands means lesser trade deficits, if any exist with the US, given diverse alternatives of China’s import categories sources.

It is instructive to point to the greater impact of US firms operating in China that owned these product categories of US imports from China for decades. The point is that American investments in China serve American consumers while significantly contributing to trade deficits as demand for American products from China increases. As Wu (Citation2020) pointed out, since 2000, American firms have moved to China for investment, helping China reach industrial and military objectives that undermine the US’s ability to be a long-term tech leader and industrial competitor. The industrial moves in China are due to a relatively cheap corporate tax rate of 25% in China to 35% in India. 34% in Brazil, and Mexico 30% and fewer logistic challenges, abundant skilled and unskilled labour force with weak unions, and stable currency. These account for the huge presence of American multinationals in China (Rapoza, Citation2019) and continued trade deficits for decades.

Part of the problem is that most American firms in China have a high share percentage (Mclntyre, Citation2020), and the US companies are responsible for shipping products from China to the US (Burke, Citation2020), contributing to the tragedy of the trade imbalance. For instance, General Motors owned a 12.8% share in China, Microsoft at 99.3%, Boeing at 52%, Nike (NA), Intel at 14.9%, and Apple’s iPad at 51% (Mclntyre, Citation2020) contribute to the US top 10 imports for 2020. The amounts of imports by these companies into the United States such as Machinery-computers including optical readers and computer accessories at (US 104.9billion), Electronics such as phone system devices, integrated circuits ($343.5billion), Vehicles-cars, automobile parts, trucks ($254.4 billion), and Pharmaceuticals-medication mixes in dosage, blood fractions including antisera ($139.5 billion) tallies with the specialization of these industries (Workman, Citation2021).

Another problem is that China’s unorthodox trade practices mandate these companies to store users’ data within Chinese borders, turn over source code and encryption software to the government, and potentially give the government a back door into private data and proprietary technologies (Swanson, Citation2017). This illiberal economic practice by the Chinese government is perceived as an imbalance of alleged widespread IP theft of US companies in China without Chinese government protection for the firms (Dhue & Tausche, Citation2018). However, the firms’ products serve higher consumer demand and retailers’ importance for markets in and outside China, including the US (Mclntyre, Citation2020). In that regard, US companies lose hundreds of billions of dollars in IP theft and millions of jobs to Chinese firms as the ‘price’ of doing ‘cheap’ business in China (Mason, Citation2018).

Suffice it to say that high imports of imported products from the automotive industry, operating systems, sportswear, semiconductors, and smartphone tablets generate revenues for the United States and China and profits for multinational companies. For instance, General Motors GM) surpassed Toyota Motors in the first half of 2011 to become the largest automaker in the World. Evidence shows that GM is a top-selling brand. In 2010, GM sold more vehicles in China than in the US for the first time. Moreover, the GM share in China has grown from 3.4% to 12.8%. This same profit-making cut across Boeing, US sneaker maker Nike, Microsoft, Intel, and Apple. For Apple, the company’s China sales for the quarter ended in June 2011 and increased six times from the same period the year before, with a market share of 51%, and other companies like Lenovo at 13.8% and Samsung at 9.8%. Intel, the world’s largest semiconductor chip maker, had a 14.9% market share in 2010. That year alone, Intel made nearly $20 billion in revenue in China, an increase of more than 26% from 2009 (Wall Street, Citation2016).

Other US companies include the Whirlpool Corporation, an American multinational manufacturer and marketer of home appliance supplies, which exports some American brands, such as KitchenAid, to the US. Also, there is the classic Timex wristwatch, and Mattel is China’s world’s largest toy company. The presence of these companies in China has contributed to the increase of US import deficits and the decoupling strategy by the US to slow major imports in some product categories in 2019. In 2019, the biggest import decline was technology and subcategories like cell phones and related equipment, from 71.88% to 49.61%, and computers, from 68.36% to 45.91%. (Roberts, Citation2020). Under the Biden administration, the motivation for spurring decoupling continues due to the diversification of imports from Vietnam to make supply chain goods more resilient despite the size and diversity of the Chinese economy (Bown, Citation2022).

Decoupling dropped US imports from China to 38.59% in 2019 from 40.59% in 2015; imports increased to 41.11% in 2020 (Burke, Citation2020). This shift in 2019 saw US imports from Vietnam jump from 5.8% in 2018 to 34.8% in 2019, and imports from mainland China shrank by 13.4% (Shao, Citation2019), making Vietnam the highest beneficiary of the US-China trade war. Even though Trump slapped over 400% tariffs on steel imports from Vietnam because they originate from Taiwan and South Korea (Jamrisko, Citation2019). Therefore, the challenge for decoupling is how to de-link Chinese companies’ foothold in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Mexico, where American companies seek new suppliers.

These challenges support the logic that decoupling impacts are less significant for the Chinese economy amid affiliated Chinese companies in Asia and Latin America, high tariffs, and the cost of firm relocation. In addition, decoupling will have less spontaneous impacts on China, considering China’s ‘dual circulation strategy’ since 2005. The dual circulation policy aims to reduce China’s dependence on imports of primary raw materials and other foreign firms’ products, including technology. Next, facilitates the building of indigenous firms to ensure dominance in manufacturing products, and, lastly, it addresses substantial future impacts of decoupling, leveraging on its comparative advantage on factors of production (Stewart & Morrison, Citation2021)

However, evidence suggests the US decoupling has impacted China’s economic growth and downturn. As Manca (Citation2023) notes, the Chinese footprint in the US economy is shrinking because China has lost its title as the top export of goods to the US for the first time in 15 years. Consequently, Mexico became the US top trading partner in 2023 with an estimated volume of trade at $798.83b, followed by Canada and China at the third position, losing the top position for the first time as the US top supplier of goods since 2005 without reaching $600b (Manca Citation2023; Roberts, Citation2024). Besides China’s trade drop with the US, Chinese FDI in the US has been slowing down since 2017. This is because, in 2016, annual Chinese FDI stood at $46b, which is relatively high, at $5b in 2022, representing a drop in earnings for Chinese companies and the US workforce (Manca, Citation2023).

Succinctly, the trade imbalance often does not translate to money lost to other countries because the trade gap has multiple macroeconomic factors (Tankersley, Citation2018). Macroeconomic factors revolve around the exchange rate policy, foreign currency reserves, trade policies, inflation, and the domestic nature of factor endowments like Labour, Land, and Capital. These factors determine the economy’s overall trade deficits. Therefore, multiple macroeconomic factors contribute to the trade gap, which occurs when imports exceed exports, and the government spends more money while making less. While China has leveraged factors of production, the recent macroeconomic challenges of local government debt, over-indebted property sector, and questionable commercial bank loans are deep-seated structural issues that dampen Chinese economic growth (Hale, Citation2023).

The consensus is that China’s macroeconomic woes show slow economic growth, declining foreign trade, and Yuan deflation that cannot generate enough jobs for Chinese graduates. Accordingly, Graham (Citation2023) gave detailed moments of the macro weakness of the Chinese economy. The weakness underlines the deflationary pressures on the Yuan that reduced consumers’ confidence in the Yuan while cutting their spending on households and property. The danger in China’s property crisis is that beyond costing Beijing more than $280 billion in purchasing private residents and increasing government role from 5% to 30%, it is even worse considering China’s shrinking population (Ezrati, Citation2024), which is an effect of the one-child policy in the 1980s and abolished in 2015. Besides the birth control dilemma, the increasing cost of parenting and the ageing workforce threaten the future Chinese economy and labour supply.

Moreover, Graham (Citation2023) reminds us that Chinese youth unemployment increased from 10.1% in December 2018 to 16.8% in August 2020. In January 2021, it dropped to 12.7% but gradually increased to 16.2% in July 2021, 19.9% in July 2022 and 21.3% in June 2023. In the manufacturing sector, Chinese exports dropped to –20.7% in February 2019 and -40.6% in February 2020. However, the economy recorded its highest export in May 2021 at 53.18%. At the import level, there was an increase from 2.34% in June 2020 to 53.18% in May 2021. However, in June 2023, exports and imports dropped (negative), such that imports were 12.36% and exports were -12.41%. Chinese foreign trade crisis affected the manufacturing sector, seeing Chinese manufacturing decrease to 3.7 per cent from the forecast of 4.3 per cent due to decreasing demand for Chinese exports (Graham, Citation2023). The skepticism is that economic globalization and its global value chain web are too integrated to untangle, with China as the global manufacturing power hub and Washington policies unlikely to yield the desired full decoupling. Just like we ascribed China as a global manufacturer power hub, world trading relies on the US dollar as the global and acceptable currency for trade and reserves in the aftermath of World War 11.

Globally, for over 80 years since 1944, the US Dollar was cemented as the nation’s international trade currency and the forex reserve for countries in the Bretton Woods Conference. At the Bretton Woods Conference, 44 countries agreed to the creation of the IMF and the World Bank and the idea of a float exchange system where countries pegged the value of their currency to the US dollar, which reflects the beginning of the US economic dominance. However, de-dollarization attempts by BRICS countries and others are growing as non-traditional currency users of the UD dollar trading and foreign reserving that will reduce countries’ share of US dollar dominance. Accordingly, Berman and Siripurapu (Citation2023) argued that de-dollarisation had dropped the US dollar influence to the lowest since 1999 at 71% to 59% in 2023. Although, after the 2008 financial crisis, the US dollar dropped to 61% in 2011 and bounced back to 65% in 2016. Nonetheless, as of 2023, most foreign exchange reserves are in US dollars such that the US dollar maintains lead at 59%, the Euro at 19.8%, Yen (5.5%), GBP (4.9%), Chinese Yuan (2.6%), Canadian dollar (2.4%), Australian dollar (2.0%) and other currencies (3.9%).

In support of these claims, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) details claims made in US dollars by countries from the fourth quarter of 2022 to the fourth quarter of 2023 as Q4 of 2022 at $11,917.72b, Q1 of 2023 at $12,025.76b, Q2 of 2023, at $12,050.31b, Q3 of 2023 at 11,845.66b, and Q4 of 2023 at $12,332.46b. Out of the total foreign exchange reserves for Q4, $11,449.40b were allocated and unallocated reserves were at $883.06b. In the allocated reserves, $6,686.11b were claims made in US dollars, $2.287.57 in Euro, the Japanese Yen at $652.90b, the British pounds at $553.91b, Chinese Yuan at $261.73b, Canadian dollars at $295.25b, Australian dollar at 241.78b, Swiss francs $26.38b and claims in other currencies at $442.77 (IMF., Citation2024). The question is whether de-dollarization proponents can dethrone the dollar, given the problem of the robust absence of central bank and monetary policies and the growing impacts of cryptocurrencies worldwide (Berman & Siripurapu, Citation2023). Despite these concerns, the BRICS must overcome the Euro currency as the second most used reserve currency and other currencies such as the GBP and Yen.

Another concern is that China’s continuous purchase of the US Treasury to enhance its fiscal policy and maintain an export-driven economy means China’s continual storage of US dollars in foreign reserves and offsetting its US debt. The good thing about offsetting debt for China is that US debt offers the safest heaven for Chinese forex reserves, which means China offers loans to the US so that the US can keep buying the goods China produces. Besides, Beijing has the highest foreign exchange reserves of the US dollars to the tune of $3.22 trillion (Berman & Siripurapu, Citation2023), which can be used to pay Middle East countries for oil supplies despite China-UAE currency swap of $6.98b for three years signed on November 2023 (Ali, Citation2024).

Nevertheless, the circular benefit for the US and China- is that the US can reverse its import of Chinese goods. That is why there is a division among trade experts and economists on how trade deficits hurt the economy regarding jobs and investments, given the diverse impacts of macroeconomic factors. For instance, when the law of excess supply is set in, for instance, for the US dollar, it will decrease the demand for the dollar and increase the demand for the Renminbi, making Chinese goods expensive and losing competitive advantage. In reverse, the Chinese currency’s high exchange rate will reduce China’s exports, which policymakers in China are conscious of.

Besides, no country will deny that it has not benefited from trade deficits with another country because an ideal trade balance in international trade economics is unattainable. Just like when the Japanese and German economies declined after the Second World War, the US maintained decades of net export of food, manufactured commodities, and capital to other parts of the world. As the USCB Citation2020 report reveals, American dominance came after the shift started in the 1970s following the rebuilding processes of most countries’ economies in Europe and Asia and the increasing demand for goods and services worldwide. The situation in recent years shows how China’s persistent chronic trade surpluses and imbalances have created discontent in most developed economies (Woo, Citation2018, pp. 640–647).

In the US, discontent has been a long-decade issue in trade relations in the past years due to dysfunctional financial markets in China and large government budget deficits. In Europe, the EU’s trade gap with China doubled between 2002 and 2006, reaching a record high of £184.8 billion in 2018 (China Power Team, Citation2020). Arguably, trade surpluses and deficits are inevitable aspects of international trade relations, given each country’s natural characteristics of combined production factors that are interrelated with the government policy. So, in the disguise of competitiveness, the government employed a strategic economic policy frame to dominate international economic relations, and the strategic policy took effect where the policy boiled down to household income capacity or inequality and business. In most cases, the policies are negative, and the citizens experience low purchasing power on foreign goods and patronise domestic commodities, which increases trade surplus where countries’ exports exceed imports.

So, both the allegation of currency manipulation and the trade-related issues against China by the US and the developed countries of gaining undue advantage point fingers at the WTO and IMF. Lawrence stated that, in principle, the safeguard actions of Trump’s tariff were legal. Yet, it is an illegal measure under the WTO as countries can retaliate the same (Lawrence, Citation2018), which leaves the WTO to fix the US concern about China’s baffling trade practices. If that is the case, the two issues, currency manipulation and trade deficits, recognized that China deserves a greater say in the international economic institutions in return for greater responsibility that will checkmate baffling Chinese practices such as restrictions on imports and investment, weak IPR protection, forced technology transfer, and subsidies to developed specific technologies (Dollar, Citation2020).

The deeper, not partial integration of the Chinese engagement would minimize the narrative of loopholes in IMF and WTO dispute mechanisms and Articles of Agreements. In other words, it will impel China to be accountable to global trading rules and bind them to wide-ranging economic and systematic changes to meet commitments agreed to undertake as part of WTO accession (Lardy, Citation2001). Similarly, the IMF has jurisdiction over any dispute that borders on the exchange rate, and the WTO is responsible for the rules governing trade agreements with the bulk of trade disputes based on dispute settlement mechanisms and whose Article of Agreement forms a binding principle among members. Yet, China is not a member of the Government Procurement Arrangement within the WTO, the Paris Club of official creditors, or the Development Assistance Committee (Dollar, Citation2020). But, the U.S. and China are members of the IMF and the WTO and are leading members in trade volume shared. Therefore, any iota of doubt in not quantifying the impacts of currency manipulation and trade imbalance by two institutions leaves room for more controversy.

Article IV of the IMF warns members of manipulating exchange rates to gain an unfair competitive advantage over other members. Members may lose IMF membership and funding or be expelled or suspended from their voting rights when found guilty. While currency manipulation violates the IMF Articles of Agreement, there is currently no mechanism by the financial institution to punish erring members or curtail countries. So when Gagnon (Citation2012) identified the 20 most egregious currency manipulators from 2001–2011, it was obvious that the IMF was unwilling to designate countries as currency manipulators. In his identification, Gagnon classified four outstanding groups of countries. The first belongs to the advanced economies such as Japan and Switzerland; next is the newly industrialized economies such as Israel, Singapore, and Taiwan. The third is the developing Asian economies headed by China, Malaysia, and Thailand. The fourth is Algeria, Russia, and Saudi Arabia from the oil-exporting countries (Gagnon, Citation2012 p.1).

Solis (Citation2014) posits that the IMF principles are evident in that only protracted, large-scale intervention in exchange markets counts. In that manner, the IMF had recently insisted that the Chinese Central Bank had little foreign exchange intervention, implying that the US Treasury’s reckless claims are unfounded finger-pointing (China Daily, Citation2019). So, the available forum over the years to punish members has been sanctioned by the WTO, notwithstanding the difficulty of the IMF in establishing the contextual meaning of currency manipulation and the intention for undue trade advantage through currency manipulation by countries of the IMF. As major loopholes in the IMF’s Article IV principles, these gaps are the murky determination of intent to enforce currency rules in the IMF Article IV, as countries can always explain their actions (Solis, Citation2014).

Therefore, when the IMF established that and considering the magnitude of international trade impacts, WTO could meditate on the exchange rate controversy (Thorstensen et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, in areas of IPR protection, the WTO takes sole responsibility. That was why, in the March 2018 office report, the US Trade Representative (USTR) on the 301- investigation recommended three major actions: to pursue dispute settlement at the WTO to address China’s discriminatory licensing practices (Sheng et al., Citation2019). The US complaint in the WTO has been predicated since its creation in 1995 based on the assumption that regulatory regimes worldwide would converge to avoid trade friction (Rodrik, Citation2018). With this expectation, China’s accession to WTO would make China abandon its traditional view of IPR as a societal good against more Western IP-oriented protection by owners (Brum, Citation2018).

IP and patent wars

The patent war is another poisonous literature in the US-China trade war that has attracted greater concern from developed economies. The consensus is that there is a causal relationship between the production of patents and significant economic growth (Hu & Png, Citation2013; Wurster, Citation2021; Xu & Chiang, Citation2005). This is because patents encourage foreign rights holders to export high-technology goods into a domestic economy, which provides incentives to innovate the domestic market (Gold et al., Citation2019). So common patent types, Invention patents, Utility model patents, and Industrial design patents (He, Citation2021), are critical because the ownership of patents is widely seen as an important sign of a country’s economic strength and industrial expertise (Nebehay, Citation2020).

China’s role regarding IP improvement has exploded since mid-2000, supporting accelerated economic integration and development (Steinbock, Citation2018). IP impacts stimulate economic growth but depend upon a country’s level of development and its economy’s structure (Falvey et al., Citation2006). It is also accompanied by the government policy of trade liberalization (Mrad, Citation2017) and available and accumulated investment factors in R&D, Innovation, and Physical Capital (Park & Ginarte, Citation1997). So when a less-developed nation targets an invention patent type, it fosters the highest level of innovation and growth in that country and among types of patents. Such innovation fostered technological advancements and economic breakthroughs, as Japan did in the post-war rebuilding process by importing patents (Li, Citation2012).

However, the speed and trajectory in the respect and observance of patent rights remain problematic because of claims of patent rights by countries, as copyright laws are subject to the degree of economic development and set out agendas by countries. Before entering the WTO, China had a lower technological patent position, an international division of labour, and a global value chain (Li, Citation2012). In 2021–2035, China’s IP strategy has progressed to stress China’s attempt to develop its innovation for strategic and fundamental technologies to bolster economic growth and national security (He 2020). If China’s low technological position were right, it would have permitted China’s unorthodox strategy and creative industrial policies of economic liberalization to utilize the more permissive regime that governed the world economy in the early post-war period (Rodrik, Citation2018). Gradually, China’s blueprint toward technological self-reliance to become global IP protection by 2021–2035 strategy (Qu & Zhang, Citation2021) coincided with the Made in China (MIC) 2025 initiative. The MIC aims to catapult China to advanced economic status (Rodrik, Citation2018) and toward the grand goal of 2049 of ensuring sustainable and balanced economic growth against multiple domestic issues (Yana, Citation2021).

If we accept China’s low technological status (Li, Citation2012) and unconventional practice (Rodrik, Citation2018), we should worry about US technological -de-risking from China and more IP-related lawsuits in China. Under technological decoupling, Trump and Biden’s administration’s broader technological de-link strategy on China focused on cutting-edge technologies deemed national security due to a greater distrust towards China. In doing so, Zhang (Citation2023) lists nine categories of US defensive tools to protect her national security and geopolitical considerations. While Zhang’s (Citation2023) study of the US technological decoupling revolves around tighter controls of Chinese FDI in US tech companies, the blocklisting of many Chinese companies, such as telecoms giants Huawei and facial-recognition software firms SenseTime and the work of Chinese scientists in greater security measures. Technological de-risking does not generate a winner like a trade war but is a loss-loss game regarding economic efficiency.

To worsen the situation, Biden signed a law that could ban the short video-sharing app in the US within a year. Although a request was made to Chinese company ByteDance to either sell its TikTok app to an American buyer or be banned due to concerns about US national security, misinformation, children’s safety, mental health, selling of data, data security, and addictiveness (Lutkevich, Citation2024). However, America is not the only country with partially or fully banned TikTok apps. On June 29, 2020, India banned TikTok and 58 other Chinese apps over privacy and security concerns. In 2020, Afghanistan banned TikTok to protect the youth from being misled and moral concerns in other countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, North Korea, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Somalia. The same moral concerns and ban on TikTok and other social media platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook, and Telegram exist in Iran.

In Indonesia, TikTok Shop for selling products was banned in October 2023 because it violates e-commerce laws, while TikTok is banned from government-owned devices in Australia, Estonia, the UK, the EU, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Canada, New Zealand, Taiwan, Malta, France, Norway, and Latvia (Mukherjee, Citation2024). In some of these countries, notably the US, TikTok has initiated a lawsuit to claim that some of these laws were unconstitutional. Yet, the international version of TikTok, launched in 2017, is unavailable in mainland China due to Chinese government censorship. Instead, Chinese users use the app’s Chinese version, Duoyin, which launched in 2016 and has multiple features such as hotel booking and e-payment links (Lutkevich, Citation2024).

Under IP lawsuits, the IP lawsuits in China are three times more from 2016 to 2020 (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022). To that extent, US firms’ estimated theft of Chinese goods amounts to $600 billion annually in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets (Steinbock, Citation2018). If that is the case, we should begin to rethink the White House report that shows that China has witnessed massive economic growth to become the world’s second-largest economy. The White House claimed this economic growth is not without an industrial policy that seeks to introduce, digest, absorb, and re-innovate technologies and intellectual copyright from around the continents (The White House, Citation2018). We agree that IP rights have been a complex issue in the US since the mid-1990s. So, the leadership of the US, from George Bush Snr to Donald Trump and the Wall Street big business executives, has been unable to resolve the intellectual property issue (Danforth, Citation1993). The past administrations’ recurring failure portrays how highly contested IP right is in the individual case of possible infringement (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022). The failure explains how ‘inconsequential’ IP rights are and how it is difficult to challenge property theft, like certain design principles or aesthetic sensibility (Volodzko, Citation2018).

Those who think of IP as ‘inconsequential’ view it from the morally right perspective. To them, IP represents much scepticism surrounding the US patent argument in the IP that is easy to copy, share and distribute without the innovator being able to control these processes and charge consumers accordingly (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022). The first of much scepticism is the false presumption to claim a monopoly of ideas of intellectualism. Second, in this era of globalization and research, the moment ‘society’ recognizes an innovator, ‘society’ assumes ownership of the new ideas; thus, they become public property.

The two forms of the non-excludability moral justification of IP usage assume nobody produces IP because IP is, ideally, a response to address society’s challenges (Cochrane, Citation2018). Besides, apart from facilitating the diffusion of knowledge, IP disclosing know-how in a patent may privately to countries benefit inventors by deterring rivals’ duplicative R&D. Thus, preempting competitors’ efforts to similar patent technology and reducing investors’ informational asymmetries between patentees and potential investors (Graham & Hegde, Citation2015). We agree with the economic argument that IP innovators of intellectual goods are natural and, by definition, entitled to reap the benefits from their effort and investment (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022). Thus, the moral argument does not hold water since Its negligence thwarts patent owners’ goals and discourages investment, putting foreign operators in high-tech sectors at risk of losing their competitive edge (Zubascu, Citation2020).

Apart from the US-launched WTO complaint, Japan requested to join Washington’s IP measures suit against China for forcing foreign companies to transfer IP to local Chinese partners (Associated Press & Kyodo Trade Organization, Citation2018). In Germany, the chemical company Lanxess brought criminal charges against a Chinese-born German for allegedly stealing trade secrets to set up a Chinese copycat chemical reactor (Weiss & Burger, Citation2018). This industrial espionage in Europe informs German firms’ fear of IP theft because the Chinese government supports the culture of copycat products from Western countries (Evans, Citation2011). Perhaps this allegation reinforces the US concern about China’s continued failure to crack down on IP theft by US firms (Lee, Citation2020; Shang & Shen, Citation2021; Wroughton & Mason, Citation2017).

In Europe, the EU complaint about the slow progress of China’s tackling the IP problem explains the poor protection and enforcement of IP laws despite large-scale and persistent IP theft in EU companies (Rozen & others, Citation2020; Zubascu, Citation2020). The EU claim resulted in the EU initiating a dispute in February 2022 at the WTO against China’s use of anti-suit injunctions measures, a court decision issued by China’s Supreme People’s Courts (Wininger, Citation2022) since August 2020 to prohibit patent holders from asserting IP legal rights from going to non-Chinese court for enforcement (Stewart, Citation2022). The EU’s recent complaint at WTO came as China undermined IP laws and allowed Huawei, Xiaomi, and other telecom giants to secure cut-price technology licenses (Bermingham, Citation2022). The economic argument about IP informed Block’s opinions when he argued that a patent gives the author a monopoly over his innovation even though it will not last forever (Block, Citation2020). The reason is that such innovation enables the innovator to earn both the copyright and trademark and the recognition or financial benefits from what they invented (Clark, Citation2018).

For China, the US accusation of serious IP theft linked to capital and a highly opaque investor network that facilitates hi-tech acquisition abroad (Yongding, Citation2018) is a false narrative, unfounded fabrication, and groundless because of China’s establishment of an IP legal system (Roach, Citation2019; Xinhua News, Citation2019). The IP legal establishment aims to improve China’s copyright protection (Brum, Citation2018; Mendis & Wang, Citation2018), even though China is not the first country guilty of such infringements and will not be the last. Besides, China paid $30 billion in 2017 for licensing fees and royalties to use foreign technology (Lardy, Citation2018). In view that China is ranked fourth globally in the amount countries pay to acquire foreign technology, well behind Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United States, but ahead of Japan, Singapore, Korea, and India (Lardy, Citation2018).

Arguably, China’s intellectual property has made significant improvements in recent years. In 2018, the American Chamber of Commerce in China (ACCC) survey showed that 96% agreed that China had enforced IP rights against 86% in 2014. If we take the survey seriously, China may be willing to improve its technological and manufacturing innovation. Our concern is that the net effect of the degree of enforcement of IP in any country depends on the balance between the market expansion plans by the government and market environmental power. The underlying trade-off for the balance reinforced our earlier belief that innovation through IP drives economic development as countries seek to bolster their economies by transitioning from a manufacturing-based economy into a knowledge-based one (Ho, Citation2021).

So, protecting patents and IP without acceptable balance means protecting innovation and encouraging economic dependence made worse in an environment with economic potentials or global value chain products. The Chinese trade-off Gibson (Citation2020) maintained is that foreign countries take advantage of low-cost manufacturing for exports after a successful bargain in gaining market access in exchange for bringing foreign technology to China. The bargain informed the Chinese government to encourage the lawful and legitimate transfer of technology while supporting innovation by Chinese firms through indigenous innovation. Given this, Oh (Citation2018) posits that the contribution and transfer of American intellectual property theft into Chinese businesses remains unclear. However, the 2018 survey conducted by the ACCC indicates that leakage of intellectual property was a more significant concern when doing business in China than elsewhere (Oh, Citation2018).

Therefore, since China is a signatory member of the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the WTO, the need to abide by the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) becomes a necessity though a challenging task for the WTO authorities. Because the comprehensive agreement of the TRIPS covers two broad domains: the Industrial and artistic domains (Muehlfeld & Wang, Citation2022), these domains fall within copyright, trademarks, geographical indicators, industrial designs, patents, and undisclosed information. Since TRIPS aimed to maintain a standard of protection for each member in those areas, the TRIPS has a domestic procedure for enforcement and remedies and respect for WTO’s dispute settlement outcome, which serve as a basic obligation for members.

The TRIPS General Agreement recognized the minimum benchmark, allowing all WTO members to provide more exclusive intellectual property protection. The Articles of Agreement accord the treatment of all industries and commercial establishment of a person’s intellectual property rights in another member’s territory as natural and legal persons. The Article mandates all WTO members to consider authorship as the right to protect the moral and material interests of any intellectual property right in scientific, literary, or artistic production. The applicability underscores the basic principles covering the WTO establishment and other important international intellectual property conventions that approve a convergence between multilateralism and intellectual property rights for both the developed and the developing economies (WTO Agreements on TRIPS as amended by the 2005 Protocol, Citation2021).

Economic and political dimension of most-favoured-nation

For other scholars, the trade war is traceable to a diplomatic manoeuvring failure using the Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) syndrome of trade status, particularly during the George Bush Snr administration (Wang, Citation1993).

Economically, the MFN allows member countries to export products to other members at the lowest tariffs as a political waiver. While the MFN has benefited 164 members, developing countries received preferential treatment without returning benefits to develop their economies (Amadeo, Citation2020B). The US has reciprocal MFN status with all WTO members, but China’s MFN status has generated controversy despite granting MFN to China first in 1980 and permanent in 2001(Pregelj, Citation2001). Under the Bush Snr administration, the US Congress attempted to terminate or restrict China’s waiver (Bush, Citation2019). The fear is that such termination will heavily expose US agriculture commodities through Chinese tariff retaliation, severely damaging the US economy (Di, Citation1998; Waugh, Citation2019).

The fear raised a recurrent debate about the MFN status within the frame of the developing nation’s status of China at the WTO. Whether China is a developed or developing nation has been a strong concern to the US, particularly Trump’s administration. For years, China had continued to label itself as the world’s largest developing nation even when it was forced to take on commitments normally applied to developed economies before accession into the WTO (Falkenberg, Citation2021). On the other hand, the US has refused to accept China’s claim, thereby labelling China as the world’s richest country trying to benefit from WTO rules (Lee, Citation2019; Mason & Lawder, Citation2019). Undoubtedly, there is no definition of a country’s identity under the WTO, either developed status or developing economies status. However, other members can challenge a country’s decision to adopt the status, the benefits of which are not automatically under the unilateral preferences schemes. The developed country offers the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) to developing countries as enshrined in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) during trade negotiation. Under the GSP rules, the US successfully used the GSP in trade negotiations with African countries during the multilateral agreement on the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) in 2000. Still, it has not been so for a country like China, which has had years of stable economic growth.

Politically, the MFN, as a diplomatic strategy of Kissinger and Nixon’s school of thought, is the belief that the US opens the door to China’s entry into the WTO and can influence China to adopt democratic principles and wean China off state-owned enterprises (Landler, Citation2005). This ongoing diplomatic strategy has always been the foundation for bargaining during a trade war between the United States and China. Anytime there is a trade war, the willingness of the two powers to negotiate on reforms in areas like improving human rights, democratisation, copyright, and Chinese textile exports has always been a pathway to positive political change (Steinberg, Citation2020). However, each administration in the United States has prioritised the political maneuvering reforms in the ongoing areas, which forms the major vehicle influencing US-China policy during trade negotiations. As an area of prioritisation, the Obama Administration evaluated human rights decisions’ political and economic costs when criticising China.

While the Obama policy on human rights and trade issues was less clear with China, the Trump administration was clear on trade deals when it considered human rights not to be a significant issue with China. The inconsistency of each administration in the United States often invoked the feeling that the human rights campaign’s selective approach aimed to actualise a foreign diplomatic agenda. Nonetheless, there is a prospect that the human rights agenda will take center stage in any new trade negotiation in Biden’s administration with China. Noticing the prioritization of different US presidents’ diplomatic goals and approaches, Green (Citation1994) warns that Americans are tempted to improve human rights violations in China by threatening trade sanctions, denial of MFN status, and tariffs. The position of the Chinese government on Human rights issues in Tibet, Western China, Uyghurs, and other Turkic Muslims in the Northwest region of Xinjiang is that the universal notion of human rights cannot be applicable.

In that regard, China supports the principles of non-intervention and non-interference that uphold economic development over the protection of individual civil and political rights (Lum & Weber, Citation2021). Thus, China interprets US human rights policy with trade relations in China as ‘human rights diplomacy’, where the United States promotes human rights in China with motivation and is instrumental in consolidating US global power motivation (Qi, Citation2015). While protecting Human rights is enshrined in Article 35 and Article 36 of the People’s Republic of China Constitution (Lum & Weber, Citation2021), China prioritised raising the living standards of its population in the regions of Tibet and Xinjiang and other regions. These discrepancies between the US human rights notion and the Chinese perspective have raised concerns about whether the state should seek political rights before economic rights or vice versa.

Besides these conflicting opinions on the causes of the US-China trade war, we propose that the structural changes in the globalising economy induced by technology diffusion remain critical to the US-China trade war.

Understanding the globalisation of technology

Technology is an increasing core element of globalization, notably economic globalization. As earlier noted, economic globalization is an increasing interdependence of world economies in a large-scale cross-border trade of commodities and services. In that manner, economic globalisation facilitates the flow of international capital and cross-border trade of commodities due to the wide and rapid spread of technologies (Shangquan, Citation2000). On this, we hypothesized that economic globalization of technology remains a significant factor in the US-China trade war. First, globalization has been ongoing for a long period but mostly intensified significantly because of technological diffusion that countries like China have utilized (Paul, Citation2019). Such intensification enables us to see that the economic globalization induced by technology began in the late 1990s. The era witnessed structural changes in globalising economic activities across borders. It also saw the increasing role of technology, which aimed to achieve a transnational use of technology worldwide for economic, political, social, and cultural advancement. Thus, we define the economic globalization of technology as a means of developing and advancing economic immobility by countries and using new technologies to improve efficiency and productivity in economic trade, investment, and service delivery at the domestic, regional, and international levels.

The new technologies of economies used advanced robotics and miniaturisation equipment as manufacturing technology. Through this, the labour cost input of manufactured products is ultimately reduced. Simultaneously, Localizing manufacturing and local customization allow multiple redundant supply chains for products to be sold worldwide (Kleintop, Citation2022). The convergence and use of technologies at the transnational level combined to achieve economic linkages of transnational production networks growth and an increase in the transitional technological application (Boutin, Citation2004). For this reason, economists like James Broughel, Adam Thierer, and Paul Romer considered the process of technological change in an economy to be a vital driver for economic growth. As O’Sullivan (Citation2019) noted, the economist’s explanation offered insights into a better understanding of technology’s relevance to economic development. This is because it has opened new channels of markets that enhance the re-engineering of the industries, manufacturing capacity, and financial sector in all facets of society. Subsequently, it has led to the unprecedented speed of trade and relations in advanced and developing parts of the world, with no country or market spared from the tidal wave of change (Blanke, Citation2016).

Across continents, the wave of change redefining the patterns of globalization shifted faster to Asia, notably China (Tonby et al., Citation2019). Thanks to the intensity of technological innovations from advanced countries (Eugster et al., Citation2019) in China that become widespread in the economy of developing countries (Mukoyama, Citation2003) partly because of the newest consumer trend that allowed for the location of technologies (Reddy, Citation2017). The reality is that the impact of the technological innovation-induced new wave of globalization (Jayakumar, Citation2020) shows that economic measures of productive integration into the liberal economic order remain popular and owned large in the world’s two largest developing countries: India and China (Stokes 2016; Tellis & Mirski, Citation2013; Tonby et al., Citation2019). For India, the pendulum of the globalization of technology favours India due to India’s political carrying capacity for globalization compared to China (Subramanian & Dollar, Citation2022). Yet, the two countries’ different economic policies and paths to globalization (Lee et al., Citation2015; Sharma, Citation2009) are not our focus here.

Our focus is on China and the US, given the greater economic globalization of global trade volume determined by these countries and advanced steadily (Kleintop, Citation2022). Moreover, China has contributed more to global trade expansion over the past 15 years than the Eurozone and the US combined (Oxford Economics, Citation2017). So what is China’s economic globalization, and how has China achieved this greater economic globalization? What platform propelled China’s advanced economic globalization of technological position, contributing to the US-China trade war?

China’s economic globalization

China’s economic globalization of technology has been instrumental in China’s economic growth and development following the opening-up economic reform policy in the 1980s. The consensus is that China’s economic growth is a by-product of large-scale capital investment (home and foreign direct investment) and rapid, productive capacity. At the heart of these two factors in China’s economic growth is the convergence of economic reforms and technological innovation of Deng Xiaoping’s free-market globalisation policy (Zhang, Citation2018). The interplay of the economy and technology in the economic liberalisation process changed and influenced trade and capital flow in China.

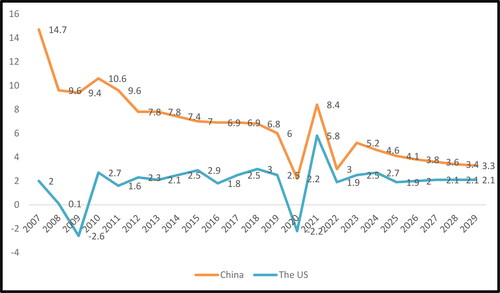

Today, evidence abounds that China’s nominal GDP has grown in leaps and bounds and has been the largest in purchasing power parity (PPP), consistently outnumbering the US. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) report indicated that China’s share of global GDP on a PPP scale rose from 2.3% in 1980 to an estimated 18.3% in 2017. Meanwhile, the US share of global GDP on a PPP basis dropped from 24.3% to approximately 15.3% in the same year with China (CRS, Citation2019). Given that China is the world’s net exporter, it is on track to becoming the world’s largest economy with an industrial technology policy encouraging domestic producers. The IMF statistics Excel data for China indicated that in 2007, China’s GDP growth stood at 14.3% and 5.2% in 2023 (IMF, Citation2024).

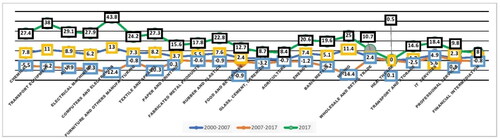

Subsequently, the GDP dropped to 9.4% in 2009 due to the global financial crisis 2008. But, Beijing implemented a massive economic stimulus package of 4 trillion Yuan ($564 billion) in response to the financial crisis (Tang, Citation2020). The massive economic package increased GDP in 2010 to 10.6% but dropped to 6.8% in 2016 (see ). The GDP increased in 2017 to 6.9% and dropped further to 1.9% in 2020 because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the global plummeting economic output, the government responded with 3.6 trillion Yuan ($500 billion) in May 2020, focusing on infrastructure spending and creating more jobs, loans, and financial relief packages for businesses (Tang, Citation2020). On that note, Beijing set a target growth of over 6% for 2021 (Cheng, Citation2021), and the IMF extracted data report estimated China’s GDP growth increase in 2021 to be 8.2%. However, the current Beijing structural macroeconomic woes have undermined projected economic growth, expected to drop from 8.4% in 2021 to 4.1% in 2025 and a further 3.3% in 2029. In contrast, China’s economic growth surpassed that of the US, with the US’s negative economic growth in 2009 at -2.6% due to the economic crisis of 2008 and 2020 at -2.2 as the pandemic walloped workers and businesses across the US (see ).

Figure 2. GDP Growth in China 2007–2029. Source: The authors, Citation2024.

To improve and sustain its economic growth, China launched the ‘Made in China (MIC) 2025’ plan in 2015, which was inspired by the German government’s Industry 4.0 development plan (Zhang, Citation2018). The understanding is that knowhow and investments in technology have played an important role in enabling countries to advance and promote economic growth. Therefore, the MIC 2025 is the government’s holistic plan for China to compete in a structural globalized economic technology, addressing society’s common challenges in China. The MIC agenda is a continuation of China’s economic reforms in 1978. Moreover, the 1978 reform points to China’s MIC 2025, a national strategy and the 2049 agenda as a quest for a dominant position in global markets. As a state-led industrial policy, the MIC 2025 and 2049 aims to surpass Western technological prowess and establish ten priority tasks and strategic industries. The tasks of MIC 2025 will move China up and dominate in global high-tech manufacturing, information technology (IT), advanced robotic and artificial intelligence, agricultural technology, aerospace, and bio-medicine by 2049 (Stewart & Morrison, Citation2019; McBride & Chatzky, Citation2019). As Beijing’s hybrid state-capitalist system, the MIC 2025 agenda collectively forms China’s economic globalisation of technology, which forms an integral aspect of the US-China trade war 2018.