?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

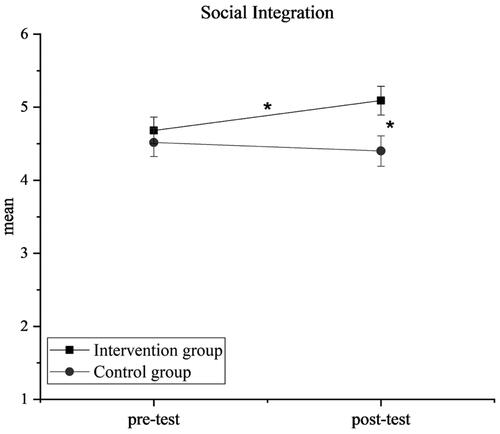

This experimental field study investigated the social-educational outcomes of a six-week soccer intervention in a German prison. Before and after the intervention, social integration and social self-efficacy expectations were assessed in the intervention (n = 11) and control group (n = 10). Within the intervention group, group cohesion was assessed after the first and last session. The results of analyses of variances revealed a significant positive interaction effect of time × group for social integration, indicating an increase in the intervention group in the post-test. For group cohesion, the dimension of social group integration increased significantly from pre- to post-tests.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Imprisonment is associated with permanent separation from family, friends, and other close contacts. This separation from the usual social environment is a particular challenge for inmates and makes imprisonment an ‘isolating experience’ (Parker et al., Citation2014, p. 390). The prison culture fosters an environment that leads to different types of conflict. For example, prison social structures and regimes generate competition for scarce resources, requiring inmates to interact with unpredictable people (Edgar et al., Citation2003). This situation results in an oppressive climate of social isolation (Müller & Mutz, Citation2019), social insecurity (Edgar et al., Citation2003), disruption, and individualism (Schliehe et al., Citation2022).

Sports are seen by inmates as an important medium for coping with such negative side effects (Müller & Mutz, Citation2019). It can make an important contribution to the establishment of friendship-like relationships (Moscoso-Sánchez et al., Citation2017) and create a ‘sense of belonging’ (Gallant et al., Citation2015, p. 52). The ‘integrative potential’ of soccer is often claimed (Jurković & Spaaij, Citation2022, p. 636). According to Ascione et al. (Citation2019, p. 56), ‘youth football can be defined as an ‘educational game’, useful for finding lost but necessary values for prisoners’. Such values are social (re-)integration as the ultimate goal of the penitentiary system, social self-efficacy expectations such as the competence of being confident and feeling adequate in social situations and team cohesion, reflecting the development of constructive relationships between individuals in order to pursue a common goal (Ascione et al., Citation2019). These three values represent the opposite of social isolation, social insecurity, and individualism.

Social integration in the context of educational processes refers to the goal that all persons are integrated into their respective learning environments and perceive themselves as integrated (Martschinke et al., Citation2012). Social self-efficacy expectations are defined as the conviction of being able to act competently in social situations (Jerusalem & Klein-Heßling, Citation2002). Group cohesion is a dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs (Carron et al., Citation1998).

Outside prisons, soccer has been found to improve social integration and group cohesion. For example, Lange et al. (Citation2017) showed that a soccer project that aimed to facilitate labor market integration has a positive influence on the social integration of young male refugees into German society. The project participants, compared to the refugees in the control group, were significantly more likely to visit locals (Lange et al., Citation2017). Wikman et al. (Citation2017) examined the effects of a twelve-week team building intervention on group cohesion in three teams of elite adolescent soccer players. A Danish version of the Group Environment Questionnaire, developed by Carron et al. (Citation1985) and encompassing four dimensions, was used: social group integration, task group integration, social attraction to the group, and task attraction to the group. The results showed that social group integration increased significantly in the intervention group compared with the control group (Wikman et al., Citation2017). The effect of soccer on expectations of social self-efficacy has not yet been studied.

Existing research has examined the outcomes of educational soccer programs in prison (Meek, Citation2012; Ortega Vila et al., Citation2020; Roe et al., Citation2019). Meek (Citation2012) and Meek & Lewis (Citation2014) evaluated the 2nd chance project in which 79 young adult male prisoners completed a soccer or rugby intervention in a young offender institution in southern England. Quantitative analyses (Meek, Citation2012) confirm improvements in conflict resolution, aggression, impulsivity, and attitudes towards offending. Qualitative analyses (Meek & Lewis, Citation2014) highlighted that participation in soccer or rugby training was perceived to have a beneficial impact on prison life and culture. These benefits extended to preparation for release, resettlement support, attitudes, thinking, behavior, and in promoting desistance from crime. Roe et al. (Citation2019) examined a soccer program for five detained youth in Sweden using semi-structured life-world interviews. The program helped them feel mentally and physically better and relieved some of the negative aspects of institutionalization. Moreover, detained youths reported (re)discovering an interest in sports, improving their social skills and emotional control, and gaining optimism for their future. Ortega Vila et al. (Citation2020) analyzed the implementation of a sports-educational soccer program in 21 Spanish prisons using a questionnaire. The 468 inmates stated that the program had a favorable influence on their life in prison and considered that their participation in the program might had a significant influence on their likelihood to continue playing sports after release. In addition, inmates felt that they had learned about the contents relating to soccer and the values they had worked on and that the program had a very positive effect on their overall development as a person.

Collectively, previous research has indicated that a social-educational soccer program in prison can have beneficial social effects. However, no study has yet examined social integration, social self-efficacy expectations, and group cohesion. Given that soccer programs outside of the prison were found to enhance specific dimensions of social integration (Lange et al., Citation2017) and group cohesion (Wikman et al., Citation2017), examining the social-educational outcomes of soccer in prison might be promising. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of a soccer intervention with inmates on social integration, social self-efficacy expectations, and group cohesion. A preliminary evaluation of this study was presented on a conference (Dransmann et al., Citation2023).

Methods

Participants

The minimum sample size was estimated through an a priori power analysis with G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Citation2007). As no effect sizes were given in comparative studies, we assumed a medium effect using partial eta-square (ηp2). According to Cohen (Citation1988), η2 = 0.06 represents a medium effect. The results of the tests (alpha error = .05; power = .95) indicated a final sample size of minimum 54 participants for a repeated measures analysis of variance (within & within-between interaction). Such a sample size was not possible in this study, as the prison has space for a maximum of 50 inmates.

In total, 35 male prison inmates participated in this field study. The participants served their imprisonment in an open prison, which meant that they were free to leave the penitentiary for work, school, or formation. On a voluntary basis, inmates were either assigned to the intervention or control group. To advertise the intervention, a notice was put up a few weeks in advance and an information and introductory evening was held for all interested inmates a week in advance. There were no (financial) incentives for participation.

Before the start of the program, all test participants were informed about the study’s design and content, data handling, and right to withdraw from the study before they all signed the consent form. The inclusion criteria were completion of more than 80% of the training sessions, health status allowing individuals to engage in physical activity (determined by the management of the institution), no daily intake of medication, no intake of drugs, and lack of other training during the study period. All the procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Declaration outlines ethical principles for research involving human subjects, emphasizing the importance of minimizing bias and ensuring the validity of research results. It highlights the need for clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to avoid confounding variables, such as medication and drug use (World Medical Association, Citation2013). The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Bielefeld University (approval number: EUB-2022-193-S).

The intervention began with 19 male inmates. Eleven of the original 19 participants completed the intervention, whereas eight dropped out. Three participants could not complete the program due to injury, two participants were transferred to another facility, one participant was released early on parole, and the other two participants were disqualified because they exceeded the maximum number of four missing training sessions.

The control group started with 17 male inmates, three of whom were excluded from the empirical analysis after the pre-test. These participants were outliers in terms of the detention time (>65 months). Evidence shows that negative side effects increase significantly with time in detention (Walker, Citation1983) and, thus, would have made the comparison between the intervention and control groups difficult. Accordingly, the cutoff value for detention time was defined as exceeding the mean value by four standard deviations or more. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), for samples with n < 80, outliers are defined as 2.5 plus or minus standard deviations from the mean value. Ten of the remaining 14 inmates showed up in the post-test.

Overall, 21 inmates (age: M = 27 years, SD = 6.1; detention time M = 20.11 months, SD = 10.57) were included in the empirical analysis. The intervention group consisted of eleven inmates (age: M = 25.09 years, SD = 2.51; detention time = 21.04 months, SD = 10.58), and the control group of ten inmates (age: M = 29.10 years, SD = 8.14; detention time = 19.10 months, SD = 11.02). Detention time did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group (t(19) = 0.411, p = 0.963, d = 0.180).

Study design

The overall study consisted of a six-week soccer intervention, which was framed by a pre-test and a post-test. Social integration (Fend et al., Citation1984) and social self-efficacy expectations (Jerusalem & Klein-Heßling, Citation2002) were assessed using a paper-and-pencil questionnaire at the pre- and post-test in both groups. Group cohesion (Kleinknecht et al., Citation2014) was measured using a questionnaire only in the intervention group after the first training session and again after the last. The group cohesion questionnaire was developed for actual, i.e. perceptible groups. As the control group is not a perceptible group, the questions would be impossible to answer (). The pre-test was conducted three days before the first training session and three days after the final training session. Both the tests were performed on the same day. The completion of the questionnaire was monitored and coordinated by the scientific project manager and three research assistants.

Table 1. Items of group cohesion.

Intervention

The intervention comprised six weeks of training with three sessions each week on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Since the participants had work or school obligations during the day, every training session took place in the evening at 7 pm. The intervention was planned and implemented together with a local cooperative partner. The partner is a non-profit organization founded by two former professional soccer players, who aim to enable disadvantaged children and young people to participate in society. This goal is achieved through the triad of social learning, education, and sports as well as with the help of a pedagogically qualified team. Important to the organization is the teaching of values, such as respect, motivation, and fair play.

The training was led by two experienced coaches employed by the nonprofit organization described above. Both coaches have bachelor’s degrees in sports science. Together with both coaches, the two coauthors designed the aim and content of the intervention. In a collaborative discussion, it was decided to base the training on the ‘Scoring for the Future’ concept (Schlenker & Braun, Citation2020). The concept is a framework to increase youth employability by developing 17 necessary life skills. The essential part of the concept is a toolkit consisting of a myriad of soccer-based exercises, each designed to develop one of the 17 skills. The 17 skills were goal setting, self-confidence, self-motivation, concentration, willingness to learn, adaptability, communication, reliability, teamwork, social sensitivity, self-control, decision-making, conflict resolution, self-awareness and self-reflection, self-organization, resilience, and problem solving. Since 17 skills could not be promoted in six weeks, the most fundamental ones were selected. These are the social skills communication, teamwork, conflict resolution, and problem-solving. Furthermore, these skills are important for positive interactions and have the greatest relevance to the prison setting and the three tested outcomes.

Effective communication fosters understanding and connection among individuals, contributing to social integration and self-efficacy. Collaboration in teamwork encourages mutual support and camaraderie, enhancing group cohesion. Constructive conflict resolution strengthens relationships and promotes social integration. Successful problem-solving builds confidence and fosters unity within the team, benefiting both self-efficacy and group cohesion. In summary, the three outcomes are each influenced by at least two skills.

Every session was performed outdoors on the penitentiary’s sports field and lasted 90 minutes. The first 15 minutes were dedicated to a warm-up, while the main part of the 60 minutes focused on one of the skills. The conclusion of each session was a reflection of 15 minutes. During the first four weeks, the focus was on one skill per week. In the last two weeks, all four skills were repeated in a condensed form.

Questionnaires and measures

Social integration was measured using six items rated on a six-point Likert scale (). The original test instrument (‘Selbstkonzept der Sozialen Integration’, SKIN) was validated for school classes (Fend et al., Citation1984). Context-specific terms were adapted (fellow students to fellow inmates, and class to prison). Four of the six items were reverse-coded and recoded to retain coding logic. With 0.768, the Cronbach´s alpha of the scale was higher than 0.7, which supports construct reliability (Hair et al., Citation2010). Therefore, a social integration index was calculated as the mean of the six items.

Table 2. Items of social integration.

Social self-efficacy expectations were measured using eight items on a six-point Likert scale (). Since this questionnaire (‘Soziale Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung’, SWSOZ) was also developed for schools (Jerusalem & Klein-Heßling, Citation2002), the same term was changed for social integration. The eight items are divided into three dimensions: establishing or maintaining contact with other people, dealing with conflicts with other people, and the ability to be assertive with others. All three subscales and the entire scale had a Cronbach´s alpha greater than 0.7, indicating sufficient reliability (Hair et al., Citation2010). Again, a mean index was calculated for each dimension and for overall social self-efficacy expectations.

Table 3. Items of social self-efficacy expectations.

The group cohesion questionnaire consisted of 21 items assessed on a nine-point Likert scale (), which were divided into four dimensions: social attraction to the group (ATG-S), task attraction to the group (ATG-T), social group integration (GI-S), and task group integration (GI-T). The questionnaire was a German translation (Kleinknecht et al., Citation2014) of the Physical Activity Group Environment Questionnaire (PAGEQ) developed by Estabrooks & Carron (Citation2000). The PAGEQ is an adaptation of the Group Environment Questionnaire (Carron et al., Citation1985) for recreational sports, but with the same theoretical framework and four dimensions. Two terminologies were changed (course to training and group to training group) so that the wording of the items better fits the context. Reliability analysis indicated a Cronbach´s alpha higher than 0.9 for all four subscales. Four mean indices were computed: one for each dimension.

Data analysis

To analyze potential changes in social integration and social self-efficacy expectations from pre-test to post-test, a two group (intervention, control) × two time (pre, post) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. Post-hoc analyses (independent group and pairwise comparisons) were conducted using the Bonferroni correction. Group cohesion was analyzed using repeated ANOVA for each of the four dimensions of group cohesion. One requirement for conducting ANOVA is the normal distribution of outcome variables. All variables resulting from the questionnaires represent the outcomes in the present study and were, therefore, tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The results of this test indicate that all variables were normally distributed (p > 0.05). An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. SPSS software (version 28.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses.

Results

Social integration

shows the descriptive statistics and values of the repeated ANOVA for both groups. The intervention group improved from pre- (4.68 ± 0.51) to post-test (5.09 ± 0.61), which is a highly significant improvement (F(1,10) = 21.568, p < 0.001, = 0.683). illustrates the means of social integration for both groups. ANOVA indicated a significant interaction effect (time × group), F(1,19) = 5.032, p = 0.037,

= 0.209, but no significant effect of time (F(1,19) = 1.557, p = 0.227,

= 0.076). More specifically, the results of the post-hoc analysis showed a significant difference in the post-test between the intervention group and control group (p = 0.026), as well as a significant development within the intervention group (p = 0.020).

Figure 1. Social integration for both groups from pre-test to post-test.

Note. Error bars represent standard errors.

Table 4. Social integration (M ± SD) before and after the intervention.

Social self-efficacy expectations

presents the descriptive and concluding statistics for the total index and the three sub-indexes (contact, conflict, and assertion). All four indices showed no significant development in either group (p > 0.05). Consequently, the ANOVA showed neither a significant time nor a significant interaction effect. This applies to contact (time: F(1,19) = 2.036, p = 0.170, = 0.097; time × group: F(1,19) = 2.556, p = 0.126,

= 0.119), conflict (time: F(1,19) = 0.738, p = 0.401,

= 0.037; time × group: F(1,19) = 1.238, p = 0.271,

= 0.063), assertion (time: F(1,19) = 0.372, p = 0.549,

= 0.019; time × group: F(1,19) = 0.009, p = 0.926,

= 0.000), and the overall index (time: F(1,19) = 0.026, p = 0.745,

= 0.006; time × group: F(1,19) = 1.718, p = 0.206,

= 0.083).

Table 5. Social self-efficacy expectations (M ± SD) before and after the intervention.

Group cohesion

shows the descriptive statistics and values of the repeated ANOVA for the intervention group. The results indicated a significant improvement (5.30 ± 2.28 to 5.85 ± 2.53) for the social group integration dimension (F(1,10) = 6.328, p = 0.031, = 0.388), but no significant effects for the other three dimensions (p > 0.05).

Table 6. Group cohesion (means ± SD) before and after the intervention.

Discussion

This study examines the social and educational outcomes of a soccer program in prison. In just six weeks, the present soccer intervention significantly improved social integration and social group integration. Inmates who are better socially integrated might experience less discrimination and fewer moments of isolation within the group. According to our results, the participants of soccer training – in contrast to the inmates in the control group – feel less discriminated and lonely. The socially integrative potential of soccer, as demonstrated by Lange et al. (Citation2017) outside of the prison, was supported by this intervention in prison. Sports have so far been perceived as socially integrative by prisoners in interviews (Müller & Mutz, Citation2019), but could now be confirmed quantitatively in comparison to a control group. Consequently, offering an (educational) sports program in prison can reduce the experience of isolation (Parker et al., Citation2014).

The improvement of social group integration, as one of the four dimensions of group cohesion, shows that integration has improved from two perspectives. With social integration, the focus is on oneself, and with social group integration (GI-S), the focus is on the group as a whole. Social group integration refers to the individual perception of the similarity, cohesiveness, and connectedness of a group in terms of social aspects (Kleinknecht et al., Citation2014). This means that the inmates in the intervention group felt comfortable and experienced the group as cohesive. Like research outside prison, only the dimension of social group integration has significantly improved (Wikman et al., Citation2017). Wikman et al. (Citation2017) explained this finding with the social focus of their twelve-week team building intervention. The improvement in social and social group integration illustrates that this intervention can stimulate the process of merging and growing together. This process speaks for a good fit of the selected concept and a suitable selection of the skills.

In general, sports coaches play an important role in the outcomes of athletes and can facilitate or hinder the development of athletes (Turnnidge & Côté, Citation2020). Accordingly, positive development can also be attributed to the pedagogical quality of both coaches and their experience with the concept of ‘Scoring for the Future’. Roe et al. (Citation2019) also attribute the success of their intervention to educators’ pedagogical ability to understand inmates and make them feel respected and valued. Also, Haudenhuyse et al. (Citation2014) highlighted the importance of a ‘perceptivity’ towards the life situations of young people; in their case noted for vulnerable Flemish youths.

The intervention may have been too short and general for significant development of social self-efficacy expectations. Too short, because six weeks is an extremely short period of time compared to the average detention period of two years. In general, Bandura’s (Citation1997) theoretical assumption is that self-efficacy beliefs are domain specific. Accordingly, the physical activity self-efficacy (PASE), which refers to beliefs in one’s capabilities to learn or perform physical activities (Bartholomew et al., Citation2006), should be used in future sports studies.

The lack of change in the conflict dimension may be related to the overly confrontational nature of the intervention. After the end of the intervention, both coaches reported that the prisoners had the most difficulty with the three exercises in terms of the life skill conflict resolution. The exercises for this skill were constructed in a way that conflicts were bound to occur. For the inmates, this was a matter of recognizing and resolving them. Even more difficulties than in the practical exercises were encountered in the reflections, which were included as questions to stimulate a discussion on the exercises performed. Lack of reflectivity is a known problem for inmates, as evidenced by the high rates of reoffence, among other factors. For example, every second person released from prison in the German state of Baden-Württemberg ends up in prison (Dederichs, Citation2021).

The omitted chance for the contact dimension and the social attraction to the group (ATG-S) can be explained in the same way. Obviously, some inmates have not been able to perceive a personal relationship with the group and the social interactions within it. This is due to the artificial composition of the group, which would never have come together without training. Rather, different characters and cliques clash here, which do not like to have anything to do with each other. With the term clash, an important point emerges: sports can also have a negative influence, for example, because it reinforces existing problems or causes new problems. Especially in the case of individual sports in prison (i.e. without a coach), it can be observed that social hierarchies are established with a muscular body (Bahlo et al., Citation2022).

Importantly, sports programs cannot only promote social integration, they may also contribute to isolation or even exclusion for certain individuals. For example, inmates who have not participated may feel excluded or marginalized within the prison community. Additionally, those who are not athletically inclined or have little interest in sports may struggle to find avenues for social connection and may experience isolation as a result (Baumer & Meek, Citation2018). Therefore, while sports can be a valuable tool for fostering integration, it is important to consider and address the potential of exclusionary dynamics within such programs.

Both factors related to the group task did not change. This means that the inmates neither identified with the group task (ATG-T) nor perceived the group as unified with respect to the task (GI-T). The inmates did not consider the group task meaningful, useful, or significant. This finding can be explained by the special character of the training, which is very different from the inmates’ previous soccer experience. Thus, the training was neither competition-oriented nor designed to improve technique, tactics, and condition, nor was it an informal free-playing game. Future soccer interventions could certainly be aligned with prior sports experiences or desires.

This study has some limitations that represent avenues for future research. The main limitations originate from the setting, that is, the prison context. The most difficult circumstance is the small sample size. This resulted from the small number of inmates at this institution and the high number of dropouts, which can be explained by the high turnover in this prison (Dransmann et al., Citation2021). While a sample size of 21 participants is below the ideal minimum calculated through power analysis, it remains a feasible and justifiable option given the unique context of the study. The present study even has a higher sample size than some other quantitative studies regarding sport interventions in prison (e.g. 19 in Pérez-Moreno et al., Citation2007; 13 in Cashin et al., Citation2008; 2 in Amtmann & Kukay, Citation2016). By emphasizing the quality of data (e.g. normal distribution), focusing on context-specific insights, and employing advanced analytical techniques (e.g. partial eta-square), we can still derive valuable conclusions and provide a good basis for a possible replication study. For data protection, the training sessions were not recorded on video; accordingly, all observations refer to the descriptions of the two coaches. Future studies should examine the effects of long-term training, possibly with a qualitative design. The disadvantages of quantitative methods include the strong reduction of complex issues to a few characteristic values and the associated loss of information (Reinders & Gniewosz, Citation2015). A qualitative study could be more focused on understanding inmates and their communication and interaction with each other in and through soccer training.

To conclude, this study highlights the potential of a soccer program to enhance social integration and group cohesion among inmates, while also pointing out challenges and limitations. Although the intervention showed positive effects on social integration and social group integration as one dimension of group cohesion, it did not significantly impact social self-efficacy-expectations and other dimensions of group cohesion. The findings suggest that while sports can foster a sense of community and reduce feelings of discrimination and isolation, it may also exclude some inmates and produce feelings of isolation. Future programs should consider these dynamics and tailor interventions to align with inmates’ prior experiences and interests. Further research, particularly with larger sample sizes, is encouraged to deepen our understanding of the effects of sports programs in prison.

Authors’ contributions

MD, CM, BG, and PW contributed to conception and design of the study. MD and CM organized the database and performed the statistical analysis. MD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PW copyedited the draft for content and language. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bielefeld United and Bielefeld-Senne Prison for their cooperation. We acknowledge support for the publication costs by the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not provide written consent for their data to be shared publicly; therefore, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Milan Dransmann

Dr. Milan Dransmann (born 1988): Post-doc in the Department of Sports Science at Bielefeld University since 2014. His research focuses on endurance running, training in school sports and sport with prisoners.

Christopher Meier

Dr. Christopher Meier (born 1989): Since 2022 research associate and lecturer in the Central Operating Unit Sport and Exercise at the University of Siegen. His research focuses on instructional effects on movement learning and the teaching of sports games.

Bernd Gröben

Prof. Dr. Bernd Gröben (born 1962): Professor for Sport and Education in the Department of Sport Science at Bielefeld University since 2009. His research focuses on empirical physical education research and sports education movement research.

Pamela Wicker

Prof. Dr. Pamela Wicker (born 1979): Professor for Sport Management and Sport Sociology in the Department of Sports Science at Bielefeld University since 2020. Her research focuses on 1) sport organizations (incl. female leadership), 2) the social relevance of sport, 3) sport participation, well-being, and public health, and 4) sport and climate sustainability.

References

- Amtmann, J., & Kukay, J. (2016). Fitness changes after an 8-week fitness coaching program at a regional youth detention facility. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 22(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345815620273

- Ascione, A., Madonna, G., & Di Palma, D. (2019). Football as a tool for educational and formative growth for young people in prison. Sport Science, 12(1), 53–56.

- Bahlo, M., Bahlke, S., Wicker, P., Gröben, B., & Dransmann, M. (2022). Der Beitrag des Freizeitsports zur Identitätsbildung junger, männlicher Strafgefangener [The contribution of recreational sports to the identity formation of young male prisoners]. Forum Kinder- Und Jugendsport, 3(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43594-022-00061-0

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers.

- Bartholomew, J. B., Loukas, A., Jowers, E. M., & Allua, S. (2006). Validation of the physical activity self-efficacy scale: testing measurement invariance between hispanic and caucasian children. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.3.1.70

- Baumer, H., & Meek, R. (2018). Sporting masculinities in prison. In M. Maycock & K. Hunt (Eds.), New perspectives on prison masculinities (pp. 197–222). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Widmeyer, W. N. (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213–226). Fitness Information Technology.

- Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244

- Cashin, A., Potter, E., Stevens, W., Davidson, K., & Muldoon, D. (2008). Fit for prison: Special population health and fitness programme evaluation. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 4(4), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449200802473131

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Dederichs, C. (2021). Jeder zweite Entlasse in Baden-Württemberg landet wieder im Gefängnis. [Every second person released from prison in Baden-Württemberg end up back in prison]. Badische Neue Nachrichten. https://bnn.de/karlsruhe/resozialisierung-jeder-zweite-entlassene-in-baden-wuerttemberg-wieder-im-gefaengnis

- Dransmann, M., Koddebusch, M., Gröben, B., & Wicker, P. (2021). Functional high-intensity interval training lowers body mass and improves coordination, strength, muscular endurance, and aerobic endurance of inmates in a German prison. Frontiers in Physiology, 12, 733774. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.733774

- Dransmann, M., Meier, C., Gröben, B., & Wicker, P. (2023). Scoring for the future? Social-educational outcomes of a soccer intervention in prison. Revista de Educação Física/Journal of Physical Education. Annals of the AIESEP Conference 2023, 92(1), 130–131.

- Edgar, K., O’Donnell, I., & Martin, C. (2003). Prison violence: The dynamics of conflict, fear and power. Willan Publishing.

- Estabrooks, P. A., & Carron, A. V. (2000). The physical activity group environment questionnaire: An instrument for the assessment of cohesion in exercise classes. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(3), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.4.3.230

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

- Fend, H., Helmke, A., & Richter, P. (1984). Inventar zu Selbstkonzept und Selbstvertrauen [Self-concept and self-confidence inventory]. Selbstverlag.

- Gallant, D., Sherry, E., & Nicholson, M. (2015). Recreation or rehabilitation? Managing sport for development programs with prison populations. Sport Management Review, 18(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.07.005

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Haudenhuyse, R. P., Theeboom, M., & Skille, E. A. (2014). Towards understanding the potential of sports-based practices for socially vulnerable youth. Sport in Society, 17(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.790897

- Jerusalem, M., & Klein-Heßling, J. (2002). Soziale Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung [social self-efficacy expectation]. In M. Jerusalem, J. Klein-Heßling, & I. Schlesinger (Eds.), Skalendokumentation der Lehrer- und Schülerskalen Projektes "Sicher und Gesund in der Schule" (SIGIS) (pp. 6). Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- Jurković, R., & Spaaij, R. (2022). The ‘integrative potential’ and socio-political constraints of football in Southeast Europe: a critical exploration of lived experiences of people seeking asylum. Sport in Society, 25(3), 636–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2022.2017824

- Kleinknecht, C., Kleinert, J., & Ohlert, J. (2014). Erfassung von “Kohäsion im Team von Freizeit- und Gesundheitssportgruppen" (KIT-FG) [Validation of cohesion on teams – Leisure and health sport]. Zeitschrift Für Gesundheitspsychologie, 22(2), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149/a000115

- Lange, M., Pfeiffer, F., & van den Berg, G. J. (2017). Integrating young male refugees: Initial evidence from an inclusive soccer project. Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung.

- Martschinke, S., Kopp, B., & Ratz, C. (2012). Gemeinsamer Unterricht von Grundschulkindern und Kindern mit dem Förderschwerpunkt geistige Entwicklung in der ersten Klasse [Joint teaching of primary school children and children with the special focus of mental development in the first grade]. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, 4(2), 183–201.

- Meek, R. (2012). The role of sport in promoting desistance from crime. University of Southampton.

- Meek, R., & Lewis, G. (2014). The impact of a sports initiative for young men in prison: Staff and participant perspectives. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 38(2), 95–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723512472896

- Moscoso-Sánchez, D., De Léséleuc, E., Rodríguez-Morcillo, L., González- Fernández, M., Pérez-Flores, A., & Muñoz-Sánchez, V. (2017). Expected outcomes of sport practice for inmates: A comparison of perceptions of inmates and staff. Journal of Sport Psychology, 26(1), 37–48.

- Müller, J., & Mutz, M. (2019). Sport im Strafvollzug aus der Perspektive der Inhaftierten: Ein systematisches Review qualitativer Forschungsarbeiten [Sport in Prison from an Inmate Perspective: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research]. Sport Und Gesellschaft, 16(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2019-0010

- Ortega Vila, G., Abad Robles, M. T., Robles Rodríguez, J., Durán González, L. J., Franco Martín, J., Jiménez Sánchez, A. C., & Giménez Fuentes-Guerra, F. J. (2020). Analysis of a Sports-Educational Program in Prisons. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103467

- Parker, A., Meek, R., & Lewis, G. (2014). Sport in a youth prison: male young offenders’ experiences of a sporting intervention. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(3), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.830699

- Pérez-Moreno, F., Cámara-Sánchez, M., Tremblay, J. F., Riera-Rubio, V. J., Gil-Paisán, L., & Lucia, A. (2007). Benefits of exercise training in Spanish prison inmates. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(12), 1046–1052. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-965129

- Reinders, H., & Gniewosz, B. (2015). Quantitative Auswertungsverfahren [Quantitative analysis methods]. In H. Reinders, H. Ditton, C. Gräsel, & B. Gniewosz (Eds.), Empirische Bildungsforschung (pp. 131–140). Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Roe, D., Hugo, M., & Larsson, H. (2019). ‘Rings on the water’: examining the pedagogical approach at a football program for detained youth in Sweden. Sport in Society, 22(6), 919–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1565381

- Schlenker, M., & Braun, P. (2020). Scoring for the future. Developing life skills for employability through football. Streetfootballworld.

- Schliehe, A., Laursen, J., & Crewe, B. (2022). Loneliness in prison. European Journal of Criminology, 19(6), 1595–1614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370820988836

- Turnnidge, J., & Côté, J. (2020). Coaching impact: The transformational coach in sports. In R. Resende & A. R. Gomes (Eds.), Coaching for human development and performance in sports (pp. 73–92). Springer.

- Walker, N. (1983). Side-Effects of Incarceration. The British Journal of Criminology, 23(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a047339

- Wikman, J. M., Stelter, R., Petersen, N. K., & Elbe, A. (2017). Effects of a team building intervention on social cohesion in adolescent elite soccer players. Swedish Journal of Sport Research, 1, 1–31.

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053