?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Promotion of altruistic behaviour in organisations to foster larger, socially responsible considerations to avoid the self-centred mentality is crucial nowadays. Examining how different factors work together to support a comprehensive solution that inspires self-transformation and leads to altruistic behaviour would be instructive. Altruistic behaviour built due to yoga-based practices was identified from the past literature and is finalised based on the Fuzzy Delphi method. The WINGS method has developed the contextual relationship between the identified behaviours. The results revealed that self-transcendence has a greater impact on others for altruistic behaviour followed by psychological capital and emotional intelligence which is found to be the prime causal factor. This study will assist management practitioners and institutions in identifying the behaviours and conducting the yoga-based practice in their organization. The study will also contribute to developing efficient, long-lasting, and successful training materials for encouraging altruistic conduct among management staff.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Although both altruism and management practices are vital components of a successful business, the relationship between the two has not been given sufficient attention in modern management literature (Kanungo & Conger, Citation1993). Altruism, which is the selfless concern for the well-being of others, can play a significant role in the success of a business (Florea et al., Citation2013; Singh & Singh, Citation2022). The practice of management, on the other hand, involves organizing resources, making decisions, and directing employees towards achieving specific goals (Manz & Sims, Citation1980). When these two concepts are integrated, they can lead to a more conducive work environment that fosters employee satisfaction, productivity, and loyalty (Collins, Citation2010; Dagar et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, many modern management theories tend to focus solely on the bottom line, often ignoring the human aspect of business (Windsor, Citation2006). As a result, the connection between altruism and management practices has been largely ignored, but it remains a vital aspect of running a successful business (Florea et al., Citation2013). There is an increasing interest in coping with or responding to unfavourable workplace behaviors, as evidenced by the recent articles in numerous scholarly and popular publications (Cortina et al., Citation2022). Employees’ physical and psychological health suffers from negative workplace behaviors (Karp, Citation2014). Additionally, it raises organization costs because job performance suffers and job engagement (Xu et al., Citation2020). The enhancement of managerial performance is one of top management’s key concerns. Management experts have sought to categorize the factors affecting managerial performance and to explain performance throughout the past few decades. There is also research on workplace spirituality and the increasing demand for work–life balance and value-driven work by employees (Pardasani et al., Citation2014; Singh & Singh, Citation2022). In this situation, a prevalent misconception is that those with high IQs frequently struggle with life’s obstacles. In contrast, others with relatively average intellect frequently succeed in both their professional and personal lives. It would be wise to cast doubt on the notion that general intelligence is a reliable indicator of success in life. In India, there is a wealth of information and accumulated experience regarding how yoga as a way of life helps people live happy and successful lives (Becker, Citation2000; Goyal et al., Citation2024). There is also research on how can Indian philosophical principles be incorporated into modern management theory to improve the management of agency conflicts? To achieve this; studies are identifying dominant systems of Indian philosophy (Pande & Kumar, Citation2020; Shah & Sachdev, Citation2014). This work develops the issue discussed above by evaluating managerial effectiveness using the notion of altruistic behaviour developed by previous academics. In a study including managers from a sizable company, it also looks into the yoga lifestyle as a possible means of influencing people’s humanitarian actions.

In the past, the main ethical theories have discussed altruism: consequentialism as a form of outcome, and utilitarianism as a form of benefit to others. Altruism, in its simplest form, is an ethical philosophy that holds that a person’s moral value is defined by how their acts influence others rather than by the advantages or drawbacks they may individually feel. As a result, altruism is consistent with this natural, ‘other-focused’ understanding of care ethics, which emphasizes interdependence and connectedness based on vitalizing and life-sustaining relationships (Pandey & Gupta, Citation2008). To promote a more complete, socially conscious, ethical, value-based management and, as a result, for effective business practices in the future, fostering altruistic behaviours among corporate management would be a beneficial step. Empirical research on the impact of yoga-based practices on altruistic behaviours is lacking (Sharma et al., Citation2022). Even though numerous studies have looked at the psychological and physical advantages of yoga, there is a paucity of empirical research explicitly looking at the impact of yoga-based practices on altruistic behaviours in Indian culture. The majority of current research focuses on the well-being and personal development of the individual, ignoring yoga’s potential influence on the formation of altruistic values and behaviours within the cultural context (Fazia et al., Citation2023).

The current study focuses on yoga, an ancient system integrating physical, behavioural, mental, emotional, and spiritual practices for the achievement of moral life, personal well-being, mental serenity, and spiritual elevation (Corner, Citation2009; Harini & Nilkantham, Citation2023). Studies suggest that yoga-based programs may have a positive effect on prosaic behaviour (Fishbein et al., Citation2016). The nature and scope of its impacts are still largely unknown due to a lack of theoretical and empirical investigation.

In light of this, this study responds to the following research questions.

RQ1: What significant altruistic behaviours and values have yoga-based practices contributed to the development of Indian culture?

RQ2: How can we establish the contextual linkages between these actions and how to prioritize them from strategic management perspectives?

The following study objectives were created based on the aforementioned research questions.

RO1: To recognize the significant altruistic acts and the value system that yoga-based practices have helped to develop an Indian culture.

RO2: To create contextual relationships between identified behaviours from the strategic management perspectives.

The fuzzy-Delphi method and previous scholarly writing were used in this study to address the first research question. The Weighted Influence Non-linear Gauge System (WINGS) method is used to prioritize and create contextual relationships between identified behaviours to address the second research question. The findings of this study had numerous ramifications that could assist top business management in fostering altruistic behaviour among management staff. The uniqueness of this study is in its use of the Fuzzy Delphi and WINGS technique to identify and prioritize the altruistic actions and value system that Indian culture has developed as a result of yoga-based practices providing a novel contribution to the literature. Our empirical findings unequivocally demonstrate the significance of self-transcendence, psychological capital, and emotional intelligence in promoting altruistic conduct among management staff. By elucidating the contextual relationships between these factors using the WINGS method, we offer valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying altruistic behavior in organizational settings.

The remaining study portions are structured as follows. Section 2 contains a list of challenges as well as a review of the literature. The research technique is emphasised in Section 3. Section 4 reviews the findings, and Section 5 highlights the conclusion.

2. Literature review

Yoga is a long-standing physical, mental, and spiritual discipline with roots in India that aims to create a state of perfect balance and harmony (Black, Citation2023; Hoyez, Citation2007). It is a style of living that enhances general well-being rather than merely a type of exercise. Numerous health advantages, such as increased strength, flexibility, and balance, less anxiety and stress, and improved cognitive function, have all been associated with yoga. Furthermore, yoga practice fosters self-awareness, self-discovery, and a sense of community, all of which support altruistic behaviour (Allen & Fry, Citation2019).

Yoga is a physical and mental practice that strives to integrate the three facets of the individual. Its objectives are to promote harmony, balance, calmness, and mindfulness as well as, in the traditional Yoga tradition, to work towards transcending the ego-personality. During the second century AD, the sage Patanjali codified the ‘eight-limbed’ structure of yoga, which includes ‘physical postures and exercises’ (Asana); breath regulation (Pranayama); sensory withdrawal (Pratyahara; minimizing sensory input); concentration (Dharana; effortful, focused attention); meditation (Dhyana; effortless, perpetual flow); and moral practices (Yama; ethics while interacting with others). The physiological effects of yoga and their possible psychological advantages are the subject of a large body of research that is summarized in a special health report by Harvard Medical School (Khalsa & Elson, Citation2016). According to the study, yoga has three main benefits: (1) reduces stress and the sympathetic activation that follows; (2) increases vagal tone and parasympathetic responses associated with resilience and relaxation; and (3) reduces chronic inflammation associated with several negative outcomes, such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease.

A moral action that puts another person’s welfare first, is selfless, and has no expectations of benefits or compensation is called altruistic behaviour (Furnham et al., Citation2016). It emphasizes interdependence and relationships and serves as a continuous personal resource for helping behaviours (Penner & Finkelstein, Citation1998). The yoga way of life includes the four schools of thought known as Jnana Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, and Raja Yoga, which is a prescribed set of eight steps also known as Ashtanga yoga. Karma Yoga is the path of detached action. According to Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, karma yoga is the path of concentrating on the task at hand without selfishness, ego, or carelessness (Swami Ranganathananda, Citation2000). Jnana yoga is the path to atman (self) knowledge that Adi Shankaracharya promoted through an interpretation of the Upanishads, which are thought to be the oldest texts of Indian wisdom. Bhakti yoga is the path of total surrender to the highest power. It is founded on a profound conviction in God’s justice system. A part of Raja yoga, the eight-fold path described by the sage Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras, is Ashtanga yoga.

We speculate that embracing a yoga lifestyle may result in a complete transformation of an individual’s personality, encompassing physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects, based on an analysis of the literature. Existing research suggests that contemplative practices foster compassion, which increases real-world altruism (Lutz et al., Citation2008). According to research by Leiberg et al. (Citation2011) and Rajni et al. (Citation2022), meditation and compassion training be effective in promoting prosaically behaviour by increasing one’s sense of social and emotional connectedness with others, increasing positive affect, decreasing stress and negative affect, and increasing one’s trait mindfulness and self-compassion. Numerous studies have shown that Psychological Capital has a positive effect on people’s attitudes (such as satisfaction and commitment), well-being, and performance (such as sales performance and creative performance), as well as on management education (Idris & Manganaro, Citation2017; Khatri & Gupta, Citation2022). Strijk et al. (Citation2012) suggest introducing yoga-based practices in addition to exercises to boost the vitality of older workers at work. Yoga has traditionally been thought of as a route to Self-transcendence (Georg Feuerstein, Citation2011), but little research has looked into this connection. According to Fiori et al. (Citation2014), yoga practitioners display more Self-transcendence compared to non-practitioners, and an ethnographic fieldwork study explained how yoga caused Self-transcendence among prisoners. The applicability of yoga-based altruistic values to management practices has received scant research: Although the influence of yoga-based practices on people’s altruistic behaviors has been studied (Pandey & Gupta, Citation2008), research on the applicability of these values and behaviors to management practices is lacking. To bridge the gap between individual transformation and its practical applications in the workplace, it is essential to comprehend how yoga-based altruistic values can be effectively incorporated into managerial decision-making, leadership styles, and organizational culture.

The current study focuses on yoga, an ancient practice that combines physical, behavioural, mental, emotional, and spiritual disciplines to promote moral living, individual well-being, mental peace, and spiritual elevation. The significant altruistic behaviour in the Indian culture’s value system, which is founded on yoga practices, has been identified. The Web of Science and Scopus databases’ articles are carefully examined for this purpose for Altruistic behaviours from yoga-based practices shown in .

Table 1. Significant altruistic behaviour.

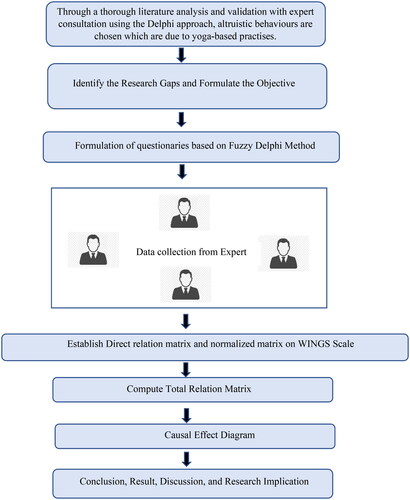

3. Methodology

The purpose of this work is to identify and rank significant altruistic activities/behaviours. The value system in Indian culture was developed through yoga-based practices. Eleven behaviours that have been found from previous literature are then finalized using the fuzzy-Delphi approach. Utilizing the WINGS methodology, these behaviours have been prioritized to develop contextual relationships among them. For this study, only a small number of experts were found and telephoned. Out of twelve, nine experts agreed to participate in total, and expert judgments were then compiled using the consensus method. A total of nine experts was involved in the study, not from a homogenous background which entails the risk of producing biased results but from a heterogeneous panel (Maleki, Citation2009). A verbal consent has been obtained from the experts to participate in this study. Since all the experts are highly knowledgeable and experienced professionals, and given their familiarity with ethics and research practices, they are capable of understanding and providing informed consent without the need for written documentation which is also waived by our institution. No any other ethical considerations were required for this study to participate.

Four yoga practitioners, two NGOs’ top experts on yoga, and three academics researching yoga are part of this study to provide their opinion. The following criteria were used to select the experts:

Yoga practitioner or researcher with a minimum of eight years of experience.

Relevant knowledge of Altruistic behaviours-Value system in Indian Culture built due to Yoga based practices.

The detailed steps followed in this paper are discussed next and shown in .

3.1. Fuzzy Delphi

Murray (Citation1985) created the fuzzy theory analysis (FDM) to overcome the fuzziness and ambiguity of expert judgements. The FDM combines the Delphi technique and fuzzy theory analysis. Addressing situations in which respondents are unable to accurately explain a decision, increases the effectiveness and quality of traditional Delphi method surveys. The application of fuzzy theory prevents the skewing of specific expert opinions, captures the semantic organization of predicted items, and takes into account the ambiguity of the gathered data (Lee & Hsieh, Citation2016). As a result, the FDM combination offers a more comprehensive expression of expert knowledge while requiring fewer samples (Ma et al., Citation2011). On the other hand, FDM’s strength is in the way all professional opinions are considered and combined to arrive at a consensus. Additionally, it produces benefits by reducing the costs and length of investigations (Kuo & Chen, Citation2008; Lee et al., Citation2018).

A more detailed description of the FDM process employed in this work may be found below. You may also refer to Sonar et al. (Citation2023) for more details.

Surveys to gather professional opinions before collecting the responses, practitioners were asked to rank the importance of each behavior. We identified each participant’s assessments for every assessment indication by using the linguistic parameters given in in Appendix A.

Computation of fuzzy numbers: The fuzzy number for each indicator was determined using triangular fuzzy numbers (W), as demonstrated in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) , which incorporates the views of all k experts.

Where J is the collection of indicators, K denotes the collection of experts, denotes the lowest expert assessment,

denotes the most expert assessment, and

denotes the highest expert assessment.

is the total triangular fuzzy number for indicator j. To determine the statistically unbiased effect and prevent the effects of extreme values, the geometric mean is used in this phase as the membership degree of the triangle fuzzy numbers, and the greatest and lowest values of the expert opinions are used as the two terminal points. This strategy may enhance the impact of the selection of criteria. Its simplicity and ability to incorporate all expert viewpoints into a single investigation are its main advantages (Kuo & Chen, Citation2008). Defuzz: Using the centre of gravity method (EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) ), the fuzzy number of each evaluation indicator must be defuzzied to determine the final weight of each indicator. To come to a consensus regarding the significance of the identified variables, we chose to use the Simple Centre of Gravity Method (SCGM) proposed by Hsu et al. (Citation2010). As can be seen below, the most widely used defuzzification method, the SCGM, works by calculating the weighted average of the membership functions.

(2)

(2)

where

is a precise score that indicates the relative importance of every potential social indicator j. Select the more significant social indicators from the expert group by determining a threshold value (β) for the indicator list. The threshold value is dependent on user preference and the fuzzy linguistic scale (Shen et al., Citation2010) state, so the greater the series of fuzzy linguistic scale, the smaller, and vice versa. Since we used the 9-fuzzy scale in this study (), the threshold value for a 9-fuzzy scale is = 5.6, according to Zhang (Citation2017).

Table 2. Aggregate fuzzy judgements.

Select factors: The last stage of FDM involves compiling a final list of indications based on the specified cut-off points.

The indicator is selected if .

The indicator is rejected if .

3.2. WINGS methodology

Michnik (Citation2013) developed the WINGS method, which analyses entangled components and their causal relationships using ideographic causal maps. This method has been used in a variety of studies, including the analysis of industry risk assessment (Rego Mello & Gomes, Citation2015), selection of a public relations strategy during a reputation crisis (Michnik & Adamus-Matuszyńska, Citation2015), assisting with decision making in civil engineering (Radziszewska-Zielina & Śladowski, Citation2017). Recently, a new extended version of WINGS has been released and is being used to assess the effects of strategic offers on a company’s financial and strategic health as well as to enhance city image building (Adamus-Matuszyńska et al., Citation2019). The WINGS process’ initial stage describes how the problem is structured. The experts first determine the fundamental components and then investigate the causal connections among them to construct a comprehensive model of the problem. A cognitive map of the issue is typically portrayed as a digraph when such a qualitative picture is given. The nodes in the cognitive map stand for the variables (also known as concepts or system components), while the arcs indicate the causal relationships that already exist (i.e. the influences or affects that exist among concepts).

The inner strength (importance, power) of the WINGS technique’s concepts set them apart from other approaches. This characteristic sets apart the roles that different concepts play within the framework. Throughout the procedure, the experts are requested to verbally assess the inside impact and strength. To preserve homeostasis, it is advised to describe internal strength using the same scale as the influences. The first step of the WINGS technique involves identifying the system, its components, and any significant interdependencies among them.

In the next phase, the system under study is studied at a quantitative level. The user is provided the verbal scale created in the previous phase so they can convert it to a numerical scale. Using integers like 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 is the simplest way to indicate voice quality ranging from extremely weak to very strong. Because the technique requires the ratio scale, this mapping must accurately reflect the user’s comprehension of the system and display the ratios between scale levels. Higher levels are compared to the original non-zero level as a unit. The direct strength-influence matrix D that follows is created using the user’s estimated values for all influences and strengths:

Values representing component strengths are entered into the fundamental diagonal, i.e. dii = the component i’s strength,

As a result, dij = the impact of component i on component j for i ≠ j. To display the influences listed in in Appendix A, influence values are inserted.

The following formula is used to calculate the scale of the Matrix D:

(3)

(3)

Additionally, the following equation yields the scaling factor.

(4)

(4)

Where n denotes the number of components.

The subsequent calculation and addition of the successive powers of the Matrix S shown in in Appendix A will yield the total impact of all direct and indirect effects. The series shown in in Appendix A converges and yields Matrix T when the scaling suggested by EquationEquations (4)(4)

(4) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) is used.

(5)

(5)

The total influence component I has on all other system components (Di) is calculated by adding up all of the row’s parts.

(6)

(6)

The total of the items in columns Di + Ri represents total receptivity, which is the total influence that component I has received from all other system components.

(7)

(7)

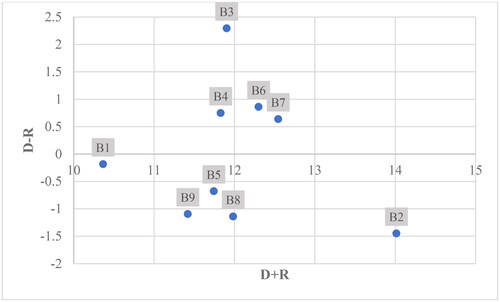

To help readers comprehend the relative significance of the system’s components and their functions, Total participation (defined as the sum of total involvement and total receptivity, Di + Ri) and total role (defined as the difference between total involvement and total receptivity, Di − Ri) are computed and presented in .

Table 3. Cause-effect relationship.

4. Results and discussion

It is incorrect that any single aspect may improve the system as a whole because there are numerous interconnected factors. Understanding how to enhance the causal group’s interrelationships of the factors is necessary to have an impact on the entire system. Because of the aforementioned situation, this paper highlights the causal relationships between the altruistic behavior-value system in Indian culture that is a result of yoga-based practices by proposing a novel coupling of fuzzy-Delphi and WINGS techniques.

The fuzzy-Delphi approach was used to identify the components that were relatively more relevant, and a threshold of 5.6 was used. Furthermore, the integrated WINGS technique can be employed to determine the causal relationships among the elements by incorporating the subjective evaluations of many decision-makers inside the group. Thus, combining fuzzy-Delphi and Wings techniques could significantly improve the MCDM employed in this work. The barriers are ranked in order of importance as B2 > B7 > B6 > B8 > B3 > B4 > B5 > B9 > B1 based on the values of D + R in . The components that make up the causal group are qualitatively rated and given priority order to establish the relative relevance of each component. Self-transcendence is identified as the most important Altruistic behaviour-Value system in Indian Culture built due to Yoga based practices.

Based on their positive and negative signs, the components in can be categorized into cause-and-effect groups (see ). The causal factor can be sorted as B3 > B6 > B4 > B7, and the ranking of effect barriers is obtained as B2 > B8 > B9 > B5 > B1. revealed that B3 Emotional Intelligence, with a score of 2.2956, was the main causative factor. Posttraumatic growth (B6) and mindfulness (B4) came in second and third, respectively, with values of 0.8621 and 0.7488. Due to their dependence on the causal factors, the elements below the X-axis should be viewed as effectors rather than the most significant causal factors, which are those above the X-axis. This division of the factors into separate quadrants will allow for further analysis.

Currently, yoga techniques are taught on a more widespread scale in India and several Western nations as a way to help people reduce stress and increase personal satisfaction. It is recommended that all corporate managers receive systematic exposure to the knowledge found in texts that promote the yoga way of life. Our research demonstrates that such an effort would benefit them both personally and professionally. They can develop into more self-aware, self-reliant people who have a healthy perspective on life and different kinds of relationships. Since Indians are likely to have some prior exposure to these ideas, assimilation of this knowledge may be better and simpler in the Indian context. The company’s top executives must be persuaded of the value of this concept. They ought to have the necessary faith in this philosophy’s efficacy themselves. The fear of ‘renunciation effects’ in a productive working environment, which is typical of business organizations that seek to cultivate their executives’ ‘killer instinct’, is one of the potential obstacles to the yoga way of life. Finding the right individuals to train company executives presents a more difficult challenge after being persuaded of the value of this training in the yoga way of life. Additionally, training must be ongoing and repeated on a regular basis. A yoga-friendly environment and acceptance of the yoga way of life must be incorporated into company policy. The results of our study highlight the critical function that altruistic behavior developed via yoga-based practices plays in organizational settings. Supervisors looking to develop a collaborative and socially conscious culture within their teams must grasp the practical consequences of these results. Employers can foster a staff that is more compassionate and aware of others’ needs by placing a high priority on the psychological capital and emotional intelligence development of their workforce. This workforce will also be more capable of navigating challenging interpersonal situations. Furthermore, our research emphasizes how critical it is to foster conditions that promote self-transcendence, in which people are driven by a sense of purpose and connectivity as opposed to self-interest. This has important ramifications for organizational growth and leadership because it emphasizes how crucial it is to foster a values-driven culture that puts stakeholders’ and employees’ welfare first. In the end, our study provides managers with practical advice on how to use yoga-based practices to foster compassion and improve organizational effectiveness in the increasingly connected and socially conscious world of today.

4.1. Theoretical implications

Altruism has been associated with favourable interpersonal outcomes, such as reduced resentment, strengthened social ties, and reduced loneliness, as well as a propensity for giving (Harmon-Jones et al., Citation2004). The current study supports yoga-based practices’ promotion of altruistic acts (collaboration, interaction, and mutual interdependence), which has important implications for management and employees’ well-being. It has been stressed that encouraging teamwork among employees with different backgrounds is essential for the company (Vem et al., Citation2024). This study provides guidelines for training that will help participants in an organizational context cooperate and support one another to obtain synergistic effects. Increasing knowledge of yoga’s effects on altruistic actions: This research adds to the theoretical understanding of the transformative potential of yoga beyond individual well-being by examining the link between yoga-based practices and the growth of altruistic behaviors. It clarifies the underlying processes by which yoga affects the development of altruistic values, adding to the body of knowledge on moral development, moral judgment, and prosocial behaviour.

Examining how yoga-based practices can encourage transcendence and self-transcendence has theoretical ramifications. Transcendence is the ability to transcend one’s problems, whereas self-transcendence is the ability to connect with something bigger than oneself. Theories of well-being, spirituality, and personal development can benefit from research on how yoga affects self-transcendence because it sheds light on how yoga practices promote a sense of connectivity and compassion for others. The investigation of the cultural context in comprehending altruistic behaviours leads to theoretical ramifications. Researchers can learn about culturally distinctive values, beliefs, and practices that influence generosity by concentrating on Indian culture and its rich history of yoga. This contextualization can offer insightful information about the role of cultural variables in encouraging and maintaining altruistic behaviors, emphasizing the significance of taking cultural diversity into account when researching ethical behavior and best management practices.

4.2. Managerial implications

Organizations can encourage the development of altruistic behaviors in managers by incorporating yoga-based practices into their management development programs. Yoga can improve managers’ ethical decision-making, interpersonal skills, and capacity to foster a positive work environment by encouraging mindfulness, self-awareness, and empathy (Tastanova et al., Citation2024). A more sympathetic and socially conscious approach to leadership and organizational management may result from this integration. Long-term sustainability through organizational support: Businesses can help managers continue their yoga-based routines and incorporate altruistic principles into their management responsibilities (Garg, Citation2018). This assistance may take the form of offering materials for yoga classes, mindfulness instruction, and building a community where managers can talk openly about their successes and struggles. Organizations can increase the sustainability of altruistic behaviours and values among management practitioners by fostering a culture of support and continuous learning.

Yoga-based practices can encourage and assist corporate social responsibility programs. As a manifestation of the ideals developed via yoga, organizations can encourage staff members to take part in volunteer programs, environmental initiatives, or community service. Organizations can show a dedication to moral and charitable behaviour, have a good impact on communities, and enhance their reputation as socially responsible enterprises by integrating their corporate social responsibility initiatives with yoga’s tenets. This can then result in increased output, decreased absenteeism, and more job satisfaction. Although yoga is a tool for self-transformation, the concepts of self-transcendence, psychological capital, and emotional intelligence are universally relevant in fostering selfless behavior in a variety of organizational settings. These insights can be used by managers to help their teams develop a culture of empathy, cooperation, and social responsibility. Organizations may cultivate a workforce that is more sensitive to the needs of others and dedicated to group achievement by placing a high priority on the psychological capital and emotional intelligence development of their workforce. Furthermore, our results highlight the significance of establishing contexts that foster self-transcendence and inspire people with a feeling of purpose and interconnectivity. Managers can enable staff members to adopt altruistic behaviors that enhance organizational effectiveness and cultivate positive connections with stakeholders by implementing training programs and focused interventions.

5. Conclusion

With management education playing a major part in this process, a larger vision and morally oriented functioning have been recognized over time as essential organizational prerequisites. It is crucial to foster altruistic behaviour in place of competitive and self-centered behaviors given the significance of employees’ ethical foundation for future management practices. The factors that help to develop altruistic behavior, however, have not been thoroughly studied. We have identified the important altruistic behaviour and found the interrelationships between them. Furthermore, we found that yoga-based practices are effective, efficient, and long-lasting training tools for developing altruistic behavior. Our study focused on the viability of including Yoga based practices in the management training of employees and discussed the value that Yoga based practices offer in terms of ethical foundations, pedagogy, leadership development, and positive organization incentives.

6. Future scope and limitations

This study has flaws that allow the researcher to see it from a future analytical angle. Other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) strategies including AHP, ANP, ISM, TOPSIS, and best-worst methods take the components’ significance into account. Empirical studies and a few case studies might also be used to support the results. The study included a total of nine experts from a diverse panel. Four yoga practitioners, two NGO experts on yoga, and three academic experts make up the group. However, including more experts could strengthen the model’s validity and aid in the generalization of the study’s findings. In addition, more behaviours might be discovered, and researchers could use this research with other organizations as well.

Ethical approval

A verbal consent has been obtained from the experts to participate in this study. Since all the experts are highly knowledgeable and experienced professionals, and given their familiarity with ethics and research practices, they are capable of understanding and providing informed consent without the need for written documentation and is also waived by our institution. No any other ethical considerations were required for this study to participate.

Author contributions

Nikhil Ghag: conception and design, methodology. Harshad Sonar: writing, drafting and data collection, final approval. Garima Chaudhary: finalization, validation. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [HS], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nikhil Ghag

Nikhil Ghag is an Assistant Professor at Symbiosis Institute of Operations Management. He has completed PhD in Operation and Supply Chain Management from IIM Mumbai and MTech in Industrial Automation and Robotics. His research is on Indian Knowledge Systems, Supply Chain Management, and Optimization. Email: [email protected]

Harshad Sonar

Harshad Sonar is an Assistant Professor at Symbiosis Institute of Operations Management. For the past few years, he has taught a variety of subjects including Operations Management, Operations Research, Logistics and Supply Chain Management, and Production Management. He has published number of research papers in peer reviewed journals including ABDC and SCOPUS listed international journals. His teaching and research areas include Additive Manufacturing, Operations Management, Manufacturing Strategy, Supply Chain Management, and Business Competitiveness. He is also reviewer for few journals (ABDC category). Email: [email protected]

Garima Chaudhary

Garima Chaudhary is a research scholar at Aligarh Muslim University. She has completed her PhD in Photography and MFA in Painting. Her research areas are visual art, contemporary art, photography, and the Virtual Art World. She can be contacted at [email protected]

References

- Adamus-Matuszyńska, A., Michnik, J., & Polok, G. (2019). A systemic approach to city image building. The case of Katowice city. Sustainability, 11(16), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164470

- Adhia, H., Nagendra, H. R., & Mahadevan, B. (2010). Impact of adoption of yoga way of life on the emotional intelligence of managers. IIMB Management Review, 22(1–2), 32–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2010.03.003

- Allen, S., & Fry, L. W. (2019). Spiritual development in executive coaching. Journal of Management Development, 38(10), 796–811. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-04-2019-0133

- Becker, I. (2000). Uses of yoga in psychiatry and medicine. In P. R. Muskin (Ed.), Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Psychiatry, 19, 107–145.

- Black, S. (2023). State spectacles of yoga: Invisible India and India everywhere. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 46(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2023.2135847

- Briegel-Jones, R. M. H., Knowles, Z., Eubank, M. R., Giannoulatos, K., & Elliot, D. (2013). A preliminary investigation into the effect of yoga practice on mindfulness and flow in elite youth swimmers. The Sport Psychologist, 27(4), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.4.349

- Cerdá, A., Boned-Gómez, S., & Baena-Morales, S. (2023). Exploring the mind-body connection: Yoga, mindfulness, and mental well-being in adolescent physical education. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111104

- Collins, D. (2010). Designing ethical organizations for spiritual growth and superior performance: An organization systems approach. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 7(2), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766081003746414

- Corner, P. D. (2009). Workplace spirituality and business ethics: Insights from an eastern spiritual tradition. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9776-2

- Cortina, L. M., Sandy Hershcovis, M., & Clancy, K. B. H. (2022). The embodiment of insult: A theory of biobehavioral response to workplace incivility. Journal of Management, 48(3), 738–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206321989798

- Dagar, C., Pandey, A., & Navare, A. (2022). How yoga-based practices build altruistic behavior? Examining the role of subjective vitality, self-transcendence, and psychological capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 175(1), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04654-7

- Fazia, T., Bubbico, F., Nova, A., Buizza, C., Cela, H., Iozzi, D., Calgan, B., Maggi, F., Floris, V., Sutti, I., Bruno, S., Ghilardi, A., & Bernardinelli, L. (2023). Improving stress management, anxiety, and mental well-being in medical students through an online mindfulness-based intervention: A randomized study. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 8214. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35483-z

- Fiori, F., David, N., & Aglioti, S. M. (2014). Processing of proprioceptive and vestibular body signals and self-transcendence in Ashtanga yoga practitioners. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8(September), 734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00734

- Fishbein, D., Miller, S., Herman-Stahl, M., Williams, J., Lavery, B., Markovitz, L., Kluckman, M., Mosoriak, G., & Johnson, M. (2016). Behavioral and psychophysiological effects of a yoga intervention on high-risk adolescents: A randomized control trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(2), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0231-6

- Florea, L., Cheung, Y. H., & Herndon, N. C. (2013). For all good reasons: Role of values in organizational sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1355-x

- Furnham, A., Treglown, L., Hyde, G., & Trickey, G. (2016). The bright and dark side of altruism: Demographic, personality traits, and disorders associated with altruism. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2435-x

- Gaiswinkler, L., & Unterrainer, H. F. (2016). The relationship between yoga involvement, mindfulness and psychological well-being. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 26, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.011

- Gard, T., Brach, N., Hölzel, B. K., Noggle, J. J., Conboy, L. A., & Lazar, S. W. (2012). Effects of a yoga-based intervention for young adults on quality of life and perceived stress: The potential mediating roles of mindfulness and self-compassion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.667144

- Garg, N. (2018). Isolationist versus integrationist: An Indian perspective on high-performance work practices. FIIB Business Review, 7(3), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714518800084

- Georg Feuerstein (2011). The encyclopedia of yoga and tantra. Shambhala Publications.

- Goyal, R., Sheoran, N., & Sharma, H. (2024). Can mindfulness be an alternative for servant leadership? A well-being perspective. Business Perspectives and Research, 12(2), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/22785337231165873

- Harini, K. N., & Nilkantham, S. (2023). Role of yoga in managing the consequences of work stress – A review. Health Promotion International, 38(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac038

- Harmon-Jones, E., Vaughn-Scott, K., Mohr, S., Sigelman, J., & Harmon-Jones, C. (2004). The effect of manipulated sympathy and anger on left and right frontal cortical activity. Emotion, 4(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.95

- Hoyez, A. C. (2007). The “world of yoga”: The production and reproduction of therapeutic landscapes. Social Science & Medicine, 65(1), 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.050

- Hsu, Y. L., Lee, C. H., & Kreng, V. B. (2010). The application of fuzzy Delphi method and fuzzy AHP in lubricant regenerative technology selection. Expert Systems with Applications, 37(1), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2009.05.068

- Idris, A. M., & Manganaro, M. (2017). Relationships between psychological capital, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in the Saudi oil and petrochemical industries. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(4), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2017.1279098

- Johnstone, B., Cohen, D., Konopacki, K., & Ghan, C. (2016). Selflessness as a foundation of spiritual transcendence: Perspectives from the neurosciences and religious studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 26(4), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2015.1118328

- Kanungo, R. N., & Conger, J. A. (1993). Promoting altruism as a corporate goal. Academy of Management Perspectives, 7(3), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1993.9411302345

- Karp, T. (2014). Leaders need to develop their willpower. Journal of Management Development, 33(3), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-04-2012-0051

- Khalsa, S. B. S., & Elson, L. E. (2016). An introduction to yoga: Special health report. Harvard Health Publications.

- Khatri, P., & Gupta, P. (2022). Impact of workplace spirituality on employee well-being: The mediating role of organizational politics. FIIB Business Review, 23197145221076932. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145221076932

- Kuo, Y. F., & Chen, P. C. (2008). Constructing performance appraisal indicators for mobility of the service industries using fuzzy Delphi method. Expert Systems with Applications, 35(4), 1930–1939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2007.08.068

- Lee, C. H., Wu, K. J., & Tseng, M. L. (2018). Resource management practice through eco-innovation toward sustainable development using qualitative information and quantitative data. Journal of Cleaner Production, 202, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.058

- Lee, T. H., & Hsieh, H. P. (2016). Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecological Indicators, 67, 779–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.03.023

- Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PLOS One, 6(3), e17798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017798

- Luthans, K. W., Luthans, B. C., & Chaffin, T. D. (2019). Refining grit in academic performance: The mediational role of psychological capital. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562918804282

- Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, T., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLOS One, 3(3), e1897. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001897

- Ma, Z., Shao, C., Ma, S., & Ye, Z. (2011). Constructing road safety performance indicators using fuzzy delphi method and grey delphi method. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(3), 1509–1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.07.062

- Maleki, K. (2009). Méthodes quantitatives de consultation d’experts: Delphi, Delphi public, Abaque de Régnier et impacts croisés. Editions Publibook.

- Manz, C. C., & Sims, H. P. (1980). Self-management as a substitute for leadership: A social learning theory perspective. Academy of Management Review, 5(3), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1980.4288845

- Michnik, J. (2013). Weighted influence non-linear gauge system (WINGS)–An analysis method for the systems of interrelated components. European Journal of Operational Research, 228(3), 536–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2013.02.007

- Michnik, J., & Adamus-Matuszyńska, A. (2015). Structural analysis of problems in public relations. International Workshop on Multiple Criteria Decision Making, 10, 105–123. http://proxy.libraries.smu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=121086062&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Morrison, K., & Dwarika, V. (2022). Trauma survivors’ experiences of kundalini yoga in fostering posttraumatic growth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(3), 821–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00441-w

- Murray, T. J., Pipino, L. L., & Van Gigch, J. P. (1985). A pilot study of fuzzy set modification of Delphi. HumanSystems Management, 5(1), 76–80. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-1985-5111

- Pande, A. S., & Kumar, R. (2020). Implications of Indian philosophy and mind management for agency conflicts and leadership: A conceptual framework. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 9(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975219858864

- Pandey, A., & Gupta, R. K. (2008). A perspective of collective consciousness of business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(4), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9475-4

- Pardasani, R., Sharma, R. R., & Bindlish, P. (2014). Facilitating workplace spirituality: Lessons from Indian spiritual traditions. Journal of Management Development, 33(8/9), 847–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-07-2013-0096

- Penner, L. A., & Finkelstein, M. A. (1998). Dispositional and structural determinants of volunteerism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.525

- Radziszewska-Zielina, E., & Śladowski, G. (2017). Supporting the selection of a variant of the adaptation of a historical building with the use of fuzzy modelling and structural analysis. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 26, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.02.008

- Rajni, Swami, A., Khan, M., Hemrajani, P., & Dhiman, R. (2022). Mapping the intellectual structure of workplace spirituality through bibliometric analysis. FIIB Business Review, 23197145221099090. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145221099090

- Rego Mello, B. B., & Gomes, L. F. A. M. (2015). Industry risk assessment in Brazil with the WINGS method. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Multiple Criteria Decision Making MCDM.

- Reitz, M., Waller, L., Chaskalson, M., Olivier, S., & Rupprecht, S. (2020). Developing leaders through mindfulness practice. Journal of Management Development, 39(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2018-0264

- Rosén, A., & Larsson, H. (2023). Arriving in the body–students’ experiences of yoga based practices (YBP) in physical education teacher education (PETE). Sport, Education and Society, 29(4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2157385

- Shah, S., & Sachdev, A. (2014). How to develop spiritual awareness in the organization: Lessons from the Indian yogic philosophy. Journal of Management Development, 33(8/9), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-07-2013-0098

- Sharma, H., Raj, R., & Juneja, M. (2022). An empirical comparison of machine learning algorithms for the classification of brain signals to assess the impact of combined yoga and Sudarshan Kriya. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, 25(7), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2021.1975682

- Shen, Y. C., Chang, S. H., Lin, G. T. R., & Yu, H. C. (2010). A hybrid selection model for emerging technology. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(1), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2009.05.001

- Singh, R. K., & Singh, S. (2022). Spirituality in the workplace: A systematic review. Management Decision, 60(5), 1296–1325. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2020-1466

- Sonar, H., Ghag, N., Kharde, Y., & Singodia, M. (2023). Digital innovations for micro, small and medium enterprises in the net zero economy: A strategic perspective. Business Strategy & Development, 6(4), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.264

- Strijk, J. E., Proper, K. I., Van der Beek, A. J., & van Mechelen, W. (2012). A worksite vitality intervention to improve older workers’ lifestyle and vitality-related outcomes: Results of a randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(11), 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200626

- Sullivan, M. B., Erb, M., Schmalzl, L., Moonaz, S., Taylor, J. N., & Porges, S. W. (2018). Yoga therapy and polyvagal theory: The convergence of traditional wisdom and contemporary neuroscience for self-regulation and resilience. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12(February), 67. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00067

- Swami Ranganathananda (2000). Universal message of the Bhagavad Gita. Advaita Ashrama, 1, 196–208.

- Tastanova, A., Henriksen, D., Mun, M., & Akhtayeva, N. (2024). The relationship between creativity and yoga nidra as a mindfulness practice: Considering the possibilities for wellbeing and education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 52, 101500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101500

- Vem, L. J., Ng, I. S., Sambasivan, M., & Kok, T. K. (2024). Spiritual intelligence and teachers’ intention to quit: The mechanism roles of sanctification of work and job satisfaction. International Journal of Educational Management, 38(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2022-0281

- Windsor, D. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: Three key approaches. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00584.x

- Woodyard, C. (2011). Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga and its ability to increase quality of life. International Journal of Yoga, 4(2), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.85485

- Xu, X., Kwan, H. K., & Li, M. (2020). Experiencing workplace ostracism with loss of engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(7/8), 617–630. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2020-0144

- Zhang, J. (2017). Evaluating regional low-carbon tourism strategies using the fuzzy Delphi-analytic network process approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 141, 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.122

Appendix A

Table A1. Linguistic evaluation scale.

Table A2. Initial Matrix.

Table A3. Normalized matrix.

Table A4. Total relation matrix.