Abstract

Agrarian conflicts between indigenous peoples and large-scale oil palm plantation companies in Indonesia always occur in tandem with the processes of expansion of new land for oil palm plantations. The article reveals how the strategies of large-scale oil palm plantation companies organize land as the key capital for the production of the oil palm plantation industry. The study case found that most of the land needed by the company was under the tenure control of the Dayak community, and the company succeeded to control the customary land through means of excluding the Dayak community from their lands by utilizing territorialization policies, organizing formal support from the village government bureaucracy to localize space for the Dayak community’s resistance to the land acquisition process. This study provides a lesson that the domination of state-village power relations is an entry point for customary land occupation processes without the resistance of indigenous peoples.

Introduction

The rise of the global market is marked by globalization, liberalization and an increase in the flow of foreign direct investment or FDI (foreign direct investment) into a country. The movement of capital from the global market, one of which leads to the industrialization sector of oil palm plantations. The speed of the global market for oil palm plantations is accompanied by customary land grabbing and estate booms (Zoomers, Citation2010). Hence, the rise of global markets is equated with the threat to local community autonomy. Thus, the parties who suffer the most from this process of market globalization are the rural poor, in particular and indigenous peoples (Hadiz, Citation2022).

In essence, land grabbing was the result of the liberalization of the land market during the 1990s and contributed to the emergence of the commoditization of land and other natural resources. Land grabbing has forced local residents to survive or move to other remote and isolated locations (Zoomers, Citation2010). The Oxfam report (2020) stated that at least 227 million hectares of land were acquired on a large scale, either through a buying and selling mechanism, a lease or a licensing system (McCarthy et al., Citation2012). This large-scale land acquisition process is certain to trigger large-scale land conflicts. In Indonesia, since the fall of the authoritarian New Order regime, many land conflicts have emerged, as well as community protest movements demanding back their lands that were seized by the state.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, Indonesia has experienced new dynamics in changes to the agrarian system due to the expansion of oil palm plantations. This palm oil expansion was triggered by the dependence of the national economy after the monetary crisis on exports of mining products and agricultural crop commodities. Especially palm oil commodities (Habibi, Citation2021). The expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia has positive benefits for the national economy. The indicator is marked by an increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Based on The World Bank’s records (2016), the oil palm plantation sub-sector contributed 2.36% of GDP (Acosta & Curt, Citation2019). Even so, ecologically, the expansion of oil palm plantations carries a severe risk of changing ecosystems and biodiversity (Fitzherbert et al., Citation2008; Koh & Wilcove, Citation2008), climate change due to deforestation and loss of peat area drainage systems, to worsening air quality, as experienced by villages in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Fargione et al., Citation2008; Germer & Sauerborn, Citation2008; Hooijer et al., Citation2006; Marti, Citation2008; Reijnders & Huijbregts, Citation2008). From a socio-economic point of view, the expansion of oil palm plantations has brought rapid changes to people’s livelihoods as well as agrarian-based social conflicts (Marti, Citation2008). However, if there is a big risk of environmental damage, it will still bring economic risks that are not cheap.

Today, oil palm is the product of the plantation economy that most resonates with large-scale agrarian transformation (Scott, 1998), especially outside Java (McCarthy & Cramb, Citation2009). Between 1962 and 2012 there has been a global expansion of oil palm plantations by up to 13 million hectares (Megahectares: Mha). If calculated from 2000 to 2017), the expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia has tripled, from 4,158,077 to 12,307,677 ha (de Vos, Citation2018). According to the FAO report (2014), almost half of this global plantation growth area is in Indonesia, with productivity reaching 47% of global production (Brad et al., Citation2015; Gerber, Citation2011). Sumatra and Kalimantan are the areas that receive the most consequences of land grabbing, because these two areas are the priority locations for the development of Indonesian oil palm plantations (Tarigan & Sunarti Widyaliza, Citation2015).

The national assets of Indonesia are between 62% and 87% in the form of land (Kartodiharjo & Cahyono, Citation2021). The rapid expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia was triggered by the power of companies combined with the support of a decentralized government system that gives local governments the authority to issue investment regulations (de Vos, Citation2018). The state’s support for these investors ultimately led to the accumulation of land assets in just a few people. In Indonesia, the top 10% of the richest people control 77% of the national wealth (Hardiyanto, Citation2020). In the case of the plantation sector, 25 large oil palm plantation companies control 5.8 million ha of the 16 million ha in Indonesia. The wealth of 29 conglomerates related to palm oil business in Indonesia estimated to be equivalent to 67% of the 2017 State Budget (Kartodiharjo & Cahyono, Citation2021). This is a sign that Indonesia still has an imbalance of control over agrarian resources.

In Indonesia, according to the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), there are 40 million indigenous people who depend on forests for their livelihood and have rights to their customary forests (Bedner, Citation2016). In the 2022 final report by AMAN, it was stated that the government had designated 105 customary forests covering an area of 148,488 ha. If it is related to the area of customary territory, most of it is forest which is registered by the Customary Area Registration Agency (BRWA). According to BRWA, the results of customary territory registration reached 21.3 million hectares spread across 29 provinces and 142 districts/cities. AMAN also found that the government had confiscated 2,400 hectares of customary territory for a social forestry program. Thus, if the expansion of oil palm in Indonesia continues to carry out the expropriation of customary lands, then agrarian social conflicts involving indigenous peoples will follow suit.

Formal law legality vs customary law legality

Land and expansion of plantation land is one of the keys to various debates and issues regarding oil palm in Indonesia (Dharmawan et al., Citation2019; Marti, Citation2008). The legal aspect of land control or tenure is one of the discourses that is often debated. Obscurity of legality and tenure has implications for the certainty of smallholders’ oil palm businesses. Moreover, when smallholders want to join the circle of sustainable oil palm certification. The legal status of land ownership according to the law of the Dayak community is not accepted in the minds of corporations working in the corridors of positive law. This is known from the enactment of plantation land certification regulations policy, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) policy. Those policies require the inclusion of a legal land certificate issued by the state. Most smallholders are unable to show formal certificates as a legal basis for ownership. On the one hand, community ownership of smallholders’ land is socially recognized, but on the other hand, the market does not recognize it. Unfortunately, this social recognition is not part of land legality (Dharmawan et al., Citation2021). As a result, smallholders remain marginalized even though they are connected to the industrial plantation system and the palm oil market.

Such conditions of smallholders are related to the nature of land law regime in Indonesia. The nature of land law and governance system in Indonesia is uncertain (Berenschot et al., Citation2023) and land tenure relations are contentious, because adopted the colonial land law system (Bedner, Citation2016). Indonesian law offers very limited recognition of land rights which can be traced back to the concept of the Agrarian Law cereated by the Dutch colonial government in 1870 called domein verklaring. This law states that every single land that is not owned by proof of ownership will be considered the state’s domain. This land law policy undermines the sovereignty of customary law communities over their land. however, after the proclamation of independence in 1945, the Indonesian government still maintained the land law inherited from Dutch colonialism, both in the Constitution of Indonesia 1945 and the Basic Agrarian Law 1960 (Bedner, Citation2016; Berenschot et al., Citation2023).

In the indigenous peoples of Dayak who work as farmers every day, this aspect of land legality has not received serious attention. On average, Dayak farmers work in fields or freehold land that have not been certified. The Dayak people call their custormary land system ‘pemali’. However, they claim, the status of Pemali land or customary land is a valid legal status, so they will defend it if there are parties who bring it up. In the pemali system, land is common pool property. In this system, provisions apply, the authority for joint ownership and land management is the traditional head. Every citizen or member of the customary community who wishes to clear land must obtain permission from the traditional leader, and the land can not be privatized, meaning it is recognized as private property.

West Kalimantan is one of the most productive provinces with the development of oil palm plantations. The two districts in West Kalimantan that are most active in producing oil palm plantations are Sintang and Sambas. In Sambas District, 32% of the total 202,331 hectares of land in 2014 had been allocated to 35 large-scale oil palm plantation companies. In the document of 2022–2040 sustainable plantation master plan was stated that Sintang Regency Government prepared 700,000 hectares of land until 2034 for large-scale oil palm plantations. The question is, how does the company control the Dayak community’s land, so that the needs of the plantation’s main production equipment are met. As we know, most of the forests and land in Sintang are under the power of the Dayak people. Therefore, the barrier or obstacle to the procurement of plantation land is the dispute between customary law which the Dayak community calls ‘pemali’ and the formal law that becomes the basis of the company.

This paper seeks to present the results of research on agrarian conflicts between the Dayak community and large-scale oil palm plantation companies in Sintang District. By using Dahrendorf’s conflict theory, this paper attempts to explore several aspects including the position of customary law (pemali) which has been tightly held by the Dayak community for generations and the formal legal position that the company holds as a means of taking over indigenous community land. The next is about the company’s ways or tactics in acquiring customary community land.

The research used as the basis for writing this paper uses a qualitative approach with the case study method. Specifically, the research highlights cases of agrarian conflicts involving the Dayak Linoh community in Perembang Village, Sungai Tebellian District, with PT. SDK, Kubink Dayak community in Bedaha Village, Melahoi Dayak community in Tanjung Raya Village in Serawai District from large private oil palm plantation PT. LJA, and the Uud Danum Dayak community in Begori Village with PT. SHP.

Qualitative data was collected through a ‘live in’ strategy in these villages in November 2021 followed by January 2022. During the live in, researchers conducted a series of in-depth interviews with key informants. Key informants were determined in a snowball manner, namely determined in sequence from the recommendation of one informant to another who was considered to have an important and competent position because of his mastery of the issues or information that became the focus of the research. Field research was carried out in the atmosphere of the Covid 19 outbreak, so the face-to-face and live-in interview processes were not carried out continuously and for a long time. Because of this, several times, the author conducted online communication, which was specifically to confirm information to the relevant informant when missing or unclear data was found. To sharpen the analysis of field research results, the researcher combined it with reading of secondary data from literature, national and international journals as well as other secondary data sourced from official government documents such as village development policy documents (RPJMDesa and APBDesa), village maps, AMDAL documents and minutes of handover receive the results of the AMDAL study, to the minutes of the partnership contract between the company and the farmers.

Indigenous people and agrarian conflict

Perkebunan adalah satu arena kontestasi perebutan sumber-sumber agraria. Masyarakat perkebunan sendiri, bukanlah sekadar masyarakat yang bekerja di sektor pertanian. Tapi melampaui posisinya sebagai petani yang hanya memenuhi kebutuhan pangan dan sudah berfikir akumulasi modal dan keuntungan. Hadirnya masyarakat perkebunan yang mendapat fasilitasi negara kemudian melahirkan ketimpangan struktur agraria. Ketimpangan struktur agraria ini kemudian melahirkan dominasi. Ujung dari dominasi dalam ketidakadilan sosial dan konflik agraria (Aprianto, Citation2006).

Conflicts among indigenous peoples based on agrarian issues in Indonesia have actually occurred in the colonial era. Likewise with the practice of land grabbing. Land grabs have occurred massively in various parts of the country, due to the systematic misinterpretation of laws on control rights over customary territories by colonial administrators who were termed beschikkingsrecht. So the violation of agrarian rights and injustice that was experienced by the indigenous people of Indonesia at that time, worked through the implementation of agrarian law which systematically curbed people’s control rights over their customary territories (van Vollenhoven, Citation1923). Colonialism in Indonesia left behind land laws that relatively ignored the original systems prevailing in Indonesian society. Indigenous systems were subordinated when necessary, especially in the interests of land acquisition to enrich the colonial government. The colonial government did little to facilitate the evolutionary change of customary land rights or facilitate gradual integration into the formal rule of law (Davidson et al., Citation2007).

Schoenberger et al. (Citation2017) have mapped the results of previous research on farmers and agrarian affairs that spanned from the 1970s to the 2000s. The results show several types: first, the literature examines the participation of peasants in the delta and lowland areas in the revolutionary movement; second, the research discourse then shifted to the emergence of new conflicts in the highlands, namely around state issues driven by the decline in forest-based people’s rebellion, to land demands for conservation and land allocation for large-scale plantations or smallholders. There are several key concepts obtained from this study, including: (i) state territorialisation, (ii) environmental transformation or what is now known as green grab, (iii) resource extraction, displacement, violence, (iv) ethnicity. Third, the wilderness of the next study pays attention to political economy discourse and commodity chain relations that shape production practices. Finally, entering the 2000s, there were many reviews on the discourse of neoliberalism, environmental governance and environmental governmentality, including agrarian issues. In particular, discourse on the dynamics of land control as a feature of land grabbing can be found in the literature on plantation crops that thrive in Southeast Asia (Hall, Citation2011), including Indonesia.

How is the practice of expanding oil palm plantations in Sintang. In general, the expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia is bound by territorialization and reterritorialization processes. (Re)territorialization since Indonesian independence related to land control changing from centralized to decentralized, followed by the formation of extractive regimes on an ongoing basis (Brad et al., Citation2015). This is where agrarian-based social resistance often occurs, namely when the state grants concession permits to companies. Dhiaulhaq’s study (2019) in Sumatra justifies this conclusion. Not only giving birth to conflict, the operation of plantation companies has also failed to provide economic benefits for people who have lost their land because the company has taken it over.

Furthermore, there are several plantation socio-economic concepts that are used as the basis for this research analysis. First, the expansion of oil palm plantations. Expansion of oil palm plantations is defined as the process of monoculturization of plants and territorialization of rural areas affecting changes in land use household livelihoods. These social and ecological changes eventually lead to socio-economic turbulence in rural areas (Yulian et al., Citation2017). The expansion of plantation land is closely related to the capitalist production system. According to Rachman (Citation2015), the expansion of the capitalist production system requires a special spatial reorganization so that the capitalistic patterned production system can expand geographically (geographic expansion). For Rachman, spatial reorganization has a broader meaning than spatial planning, because it includes space for imagination and depiction, technocratic design, material space and the place where we live as well as good spatial practices in creating space, utilizing space, modifying space to obliterate space.

Second, land grabbing and territorialization. The term land grabbing refers to large-scale cross-border land transaction agreements carried out by transnational companies or initiated by foreign governments (Zoomers, Citation2010). Researchers of the land grabbing discourse align current concepts of land acquisition, enclosure of land and dispossession of peasants with the concept that is at the heart of Marx’s analysis, namely primitive accumulation. Meanwhile, the role of the state in the accumulation and dispossession of capital is at the heart of the theorization of primitive accumulation and accumulation by dispossession from research on land grabbing (Hall, Citation2015).

According to Vandergeest (Citation1996), this process of capital accumulation will work if it is mediated through processes of institutional arrangements, legalization and making of state regulations. Vandergeest (Citation1996), defines territorialization as a process in which the state controls people and their actions by delineating the boundaries of geographic space, excluding individual categories from that space, prohibiting or suggesting certain activities within it. Thus, territorialization includes the creation and mapping of boundaries, the allocation of rights to private or state actors and the determination of the purpose of using these resources (Vandergeest, Citation1996).

The Dayak people and their Land

If there are no clouds

It doesn’t rain down to earth

If not looking for friends

Where did we come to this field

The excerpt from the rhyme above was conveyed by Mrs. Esah to the author when she met her in the fields. Ibu Esah is one of the female gardeners from Bedaha Village. The passage of the poem implies that farming and gardening for the Dayak people is not just a livelihood, but a way of life. By cultivating and gardening rubber, crops, dry land rice, Dayak farmers can support their household needs and pay for their children’s school education. Without developing oil palm plantations, the Dayak community can actually provide for their primary and secondary household needs.

Sidin (m/58 years) told the author about the success with his parents in sending his younger siblings to school so that he could achieve a successful life just from rubber gardening and vegetable farming. Narrated by Sidin, his younger brother became the camat in Nanga Pinoh, Melawi Regency. His next younger sibling, named Songkon, lives in Pontianak and has worked at the ‘Pancur Kasih’ Credit Union Cooperative. His third brother, named Lego, works in Melawi Regency at the Regent’s office. Her sister number four, Herlina Nangai, is a housewife and lives with her husband, who is a civil servant, a public teacher (SD) in the capital city of Serawai District. His last brother, named Adang, became the Head of Bedaha Village. Her own daughter, Nina, has successfully graduated from Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta, and since 2019 has been entrusted with being the treasurer of Bedaha Village.

The Linoh Dayak community in Perembang Village, the Melahui Dayak Community in Tanjung Raya Village, the Uud Danum Dayak community in Begori and the Kubink Dayak community in Bedaha Village were originally a group of people who used to live side by side with forest and river agrarian sources. Forests and rivers provide everything from animal and vegetable resources to water. To regulate the inter-village life relations and the living relationship with nature, they create a spatial and land use plan based on the prevailing customary value system.

By borrowing Vandergeest’s (Citation1996) definition, the living arrangements of the Dayak community model are territorialized policies. In a way that is still traditional, they clear land to build settlements and develop agricultural areas. They make natural boundaries such as rivers, springs and large plants as territorial boundaries between villages and land ownership boundaries. In determining the boundaries of the area and the boundaries of community land ownership, the Dayak community discusses them through the customary deliberation mechanism.

In clearing new land, Dayak people do it in groups, usually consisting of family units. The customary forest, which is still dense, is cleared of shrubs and trees by slashing and burning. The results of land clearing were built into two rooms, namely ‘gupung’ and ‘bawas’ or ‘babas’. Gupung is a unit of land of a certain size that is planted with hardwood plants such as ironwood, tengkawang and kemantan, or fruit trees such as durian. While babas or Bawas is an area of land for farming.

Gupung was deliberately built as an area that is specifically not allowed to grow crops, but functions as a nature reserve. So, indirectly, gupung has an ecological function, namely as a food source as well as a water catchment area. In its development, the gupung became the burial place for the traditional ancestors. When it became an ancestral tomb later, the status of the gupung had a higher sacred value. Because of this, the Dayak community will maintain the existence of the gupung, even though the pace of plantation industrialization continues to move into the village.

To maintain the sustainability and productivity of the land, especially for the gupung and babas areas, the Dayak community enforces the following customary rules (1) the gupung belongs to the party clearing the land, and must plant the types of plants that have been determined as gupung plants; (2) the fields/bawas/babas are basically private property. If it is neglected, then other people, as long as they are still in the lineage of the family that built the babas, are allowed to manage it. (3) If there is a person or party who wants to manage free land from outside the Dayak community, it is still permitted, but with a system of planting loan agreements/usage rights. (4) A radius of 25 meters from the outer boundary of a group, may not be used as a plantation or taken over by anyone.

The tenure system that applies to the Dayak community is similar to that which is rigid in the Temne indigenous community in South Africa. In this Temne system, the basic unit of land ownership is in the collective ownership of a large family, namely a group of people who claim to be descended from the same ancestral tree (Bottazzi et al., Citation2016). Not much different from the Temne system, the Dayak community’s customary land management system also adheres to a geneaological system. Even though they both belong to indigenous peoples, it is only the gupung that economically cannot be exchanged or traded. Gupung is maintained as a food reserve asset for the grandchildren of the owner. Babas land is not traded, but can be borrowed by different ethnic family units. Once again, this provision applies, because in the perspective of Ddayak adat, the status of babas or gupung land is ulayat land. It is this value system that presumably causes the average Dayak community to not have official land certificates as proof of private ownership.

Weakening of indigenous territorialization (customary territorialization)

In the 2020s the life of the Dayak Kubink community in Bedaha and the Dayak Melahui community in Tanjung Raya was disturbed by the presence of a company developing large-scale oil palm plantations, named PT. LJA. As is the case in other villages inhabited by the Dayak community, the land managed by the residents is labeled as pemali land or ulayat land. Pemali land is customary land on which customary provisions apply. According to the view of the local community, the history of communal land ownership originates from the agrarian system that was in effect in the era of the Melona Kingdom. This kingdom is estimated to exist until the 1800s. The management of the royal land in each regional unit called the village was handed over to an official called a tenggungan. In pemali land, the provisions apply that members of the Dayak community can clear forests and turn them into agricultural land. But the land cannot become private property in question. In other words, the community only has usage rights. In addition, land may not be traded, but can be loaned to other parties as long as they get permission from the Ketemenggungan. After the kingdom ended, the lands that were originally managed by the community changed their status to private land. But at the same time, they also claim customary land status.

When the royal government ended and changed to the colonial government, then the colonial government changed to government under the status of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI), the status of customary land was punished with the status of state land. Especially when the New Order government passed the Forestry Law in 1967. The state imposed provisions, all forests in Indonesia were under state control, and ulayat lands in Indonesia had the status of state land. Indigenous forest turns into state forest. This is where the initial history of social clashes between indigenous communities and the state.

With its power, the state coats customary lands with territorialization and zoning policies (state territorialisation). This policy covers most of the wilderness with various administrative provisions (forestry administration) ranging from permanent forests, reserve forests and other forests (various forests). In this reserve forest, the state provides an opportunity to be owned by the private sector. This space is marked by the issuance of many permits or concessions such as Forest Tenure Rights (HPH), Industrial Plantation Forest Entrepreneurs Rights (HPHTI), Business Use Rights (HGU) and Consensus Forest Use Arrangements (TGHK) (Mizuno et al., Citation2016). It is this state territorialization policy that isolates and amputates accessibility the Dayak community from their customary land. Finally, customary institutions or rules regarding land management are increasingly marginalized, and social turbulence between the Dayak community and companies and the state is inevitable again.

This study found that there was an influence of the territorialization policy structure issued by the government in relation to the zoning map of the development of oil palm plantations made by the company on the adat territorialization policy which was built traditionally by the Dayak community. The combination of state territorialization and corporate territorialization together has destroyed the local institution of the Dayak community regarding land which is called Pemali.

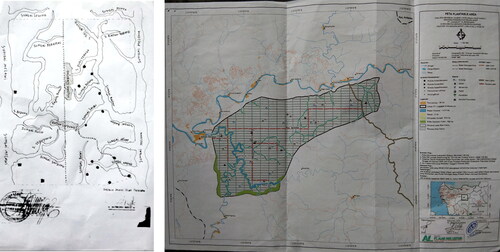

The legal mechanism enforced by the government in providing support to the industrialization of oil palm plantations is by issuing location permit regulations and Cultivation Rights. Through the location permit, the government issues a policy regarding the size of the area of land that is permitted to be developed for large-scale oil palm plantations, as an initial step before applying for HGU. The location permit is then used as the basis for the company to make a zoning map or a kind of master plan for the development of large-scale oil palm plantation areas. Like a ‘blind map’, the zoning map made by the company does not take into account customary territorialisation and tenure rights of Dayak people at all. The company divided up the area of land it obtained from the government to develop oil palm plantations, regardless of the existence of customary forests, groves, free land and human settlements (see ).

Figure 1. Customary territorialization made by the Dayak Kubink community and Dayak Melahui and Corporate territorialisation (master plan for development of oil palm plantations) made by PT. LJA.

The master plan for developing large-scale oil palm plantations prepared by the company indirectly is a form of forcing the Dayak community to relinquish their tenure rights, then handing them over to the company. The master plan also indirectly forced the Dayak community out of their traditional livelihood, from farming rice and crops to modern oil palm plantations.

Power relations customary territorialisation – state and corporate territorialisation

The customary territorialization position created by the Dayak community and the right to manage and manage their own household (self-governing community), relatively received full recognition from the state that took place before Indonesia’s independence until independence, and the government was run by the Old Order regime (Soekarno’s leadership era). But when entering the New Order, the Soeharto government removed the existence of indigenous communities as a governing society. The tool to get rid of this customary government is to enact Law no. 5 of 1979 concerning village government.

Through Law no. 5/1979, the Indonesian government created a village government structure with a new format called the official village government. With this policy, the government delegitimized traditional institutions that were previously legal and legitimate local institutions to govern and manage villages. With this law, customary institutions no longer have the authority to regulate customary territorialization policies as previously created. Even so, the government continues to use customary territorialization policies as a village area regulatory system.

Entering the reformation period and continuing to order regional autonomy, the government still does not recognize the existence of indigenous peoples. In fact, through the government decentralization policy, the central government delegated some of the authority in terms of regional spatial planning, granting permits and land concessions to district governments. This means that permits and concessions for the expansion of oil palm plantations are carried out at the district level. As a result, the structuring of the institutional status of forests in the regions has undergone many changes, and the space for plantation industrialization in the regions has become more open. Again, the institutional position of customary land territorialization is increasingly marginalized.

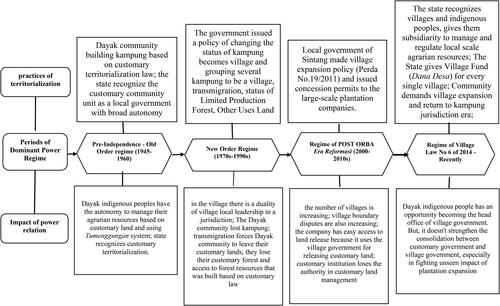

When the village law regime was in effect, even though villages were given the authority to revive customary structures and institutions, in order to optimize their role in protecting customary rights, it turned out that the pressure to acquire customary lands could still work. In other words, whether or not the Village Law exists, large-scale oil palm plantation companies still have loopholes to take over customary land from the hands of the Dayak community. Then, how do the companies get the customary land? This research identified at least three types of land acquisition by companies in the Dayak community. first, legally organized land acquisition, second, illegally organized land acquisition, and third, pragmatically organized land acquisition ().

Acquisition of customary land by plantation companies

The company needs land to develop nucleus and plasma plantations. Providing land for oil palm plantations through granting concession permits is actually an act of localizing the space for people’s lives. In line with the results of Li’s research (2017), the author agrees that the oil palm plantation business is predatory in limiting, monopolizing the important livelihoods of communities in and around plantations (plantation zones) and colonizing the law and government (Li, Citation2017). This is no exception to the practice of taking over the land of indigenous peoples on a large scale by companies. If Li, found that the practice of the mavia system occurred after the land grabbing phase, this study found that the practice of monopoly and colonization had actually started before and when the land acquisition took place.

As previously mentioned, three types of customary land acquisitions by oil palm plantation companies have resulted in the transfer of ownership of Dayak community lands into corporate hands. First, through a legal way (legally organized acquisition). In this type of land acquisition, the land acquisition process gets a legal basis from the the local village government The village government makes the development of large scale oil palm plantations as the main program of the village which is legalized in the form of the Village Medium Term Development Plan (RPJMDesa) document. The research found this practice in Perembang Village and Begori Village. Second, through illegal means (Illegally organized acquisition). Here, the land acquisition process is carried out through methods outside the legal corridor. The company organized paid local people to carry out land release transactions with the community without the knowledge or the village government. After that, they conditioned the village government to sign the minutes of hand over of land from the community to the company. Third, through pragmatic methods, namely the company takes advantage of certain socio-political conditions that are currently happening or experienced by the community, then plays them to achieve the goal of controlling community land. In this way, the company simply becomes a free rider of the policy. The following describes the three types of land acquisition.

Legally organized land acquisition

As previously mentioned, most of the state land allocated by the state to companies through a licensing system is in the hands of indigenous communities. Such conditions make it difficult for the company. Claims of customary land by the Dayak community are a barrier for companies taking over state land. Because, even though the state has granted a land concession permit, the company cannot simply acquire it. One of the state entities in Indonesia that is directly related to the existence of customary land is the village or as it is called in West Kalimantan, village. So, it is in this village that a plantation company will face resistance.

Village traditions in Indonesia are different from village traditions in Europe (Eko et al., Citation2017). Europe which places the village as a social community where all the affairs and needs of the people are served by the government. Indonesia positions the village as a governmental unit of society. Villages in Indonesia have the authority to regulate and manage their own households. But at the same time, the village is placed as part of the government structure, even though it is not an extension of the local government. In the history of villages in Sintang, in a village or village unit, actually consisted of two government organizations, namely the village government and customary government. However, the Indonesian government delegitimized it through Law no. 5 of 1979 and replaced it with the village government.

Even though in the last nine years, through Law no. 6 of 2014 concerning Villages, the state re-recognizes villages as legal community units that have territorial boundaries that are authorized to regulate and manage government affairs, local community interests based on community initiatives, origin rights, and/or traditional rights that are recognized and respected in the government system The Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia, the existence of indigenous peoples and institutions is still marginalized in the political landscape of village local policies.

In the context of local politics in Sintang, the customary institution ‘Ketemunggungan’ still exists, but has lost its authority in matters of village development, including those related to the village land system. Because, the authority has been acquired by the village government. In other words, the state still places the official village government organization as a legitimate institution to take care of matters relating to the clearing of plantation land (see ). It is this formal legal position of the village that is used by the company to secure village community land acquisition projects.

This research found that there was a practice of legally organized land acquisition carried out by PT. SDK or also called PT. LA on customary lands in Perembang Village and PT. SHP on customary lands in Begori Village. Acquisition of land in Perembang, started from the company’s success in building social framing that the arrival of industrialization of oil palm plantations to villages brought welfare benefits. This positive framing has encouraged a group of village government elites and the Dayak customary institution ‘Ketemenggungan’ to take the initiative to bring investment in oil palm plantations to the village. This initiative was motivated by the considerations of the Perembang Village Government which saw the low economic development of the community and tended to stagnate. The village government is of the opinion that without the garden their life is difficult and they remain poor. Finally, in 1991, the village government took the step of submitting a proposal to PT. SDK.

The contents of the official request are (1) The Perembang Village government wants the company to be willing to set up a crude palm oil processing factory as well as a plantation in Perembang Village, as well as absorb local workers, (2) the village government prepares a land location with a land size of less than over a thousand hectares. According to information provided by informants in the field, the land prepared consisted of land owned by certified transmigrants and land owned by the Dayak Linoh people, who on average did not have certificates except for the legitimacy of customary law itself. The next request, namely (3) the company assisted in the process of certifying the lands handed over by the village community to the company, and within a certain period of time, after the end of the collaboration, the certificates were returned to the farmers.

The process of acquiring land legally, in the sense of gaining legitimacy from village government institutions, is also found in Begori Village. The interests of PT. SHP collects ‘state land’ with the full support of local village government elites. This conclusion, at least obtained from the statement to Begori Village as follows:

In 2009 I was one of the initiators of the entry of oil palm plantation investors. Why did I make it happen at that time, because when we ran for office in 2007 we had a program to establish partnerships with other parties. Well, one of the partnerships with other parties, Sintang district, gives permits to investors to give palm oil plantation permits. In the 2009 RPJMDesa, I always echo oil palm plantation investors, with a pattern regulated by the District Government, Sintang, using a partnership pattern. (NSA, 27 January 2022)

Official political support from the Begori Village Government to PT. The SHP felt even stronger when at the same time, the Head of Begori Village served as chairman of the sub-district level Dayak Customary Council. Long story short, finally, according to the mandate in the village regulation document, in 2012 the Begori Village Government succeeded in facilitating a cooperative partnership agreement accompanied by raising community land to be handed over to PT. SHP. Partnership agreement between PT. SHP and Begori Village through the SBP Cooperative succeeded in recruiting 687 farmers and collecting 1,160 ha of land. The position of the land is not only in Begori Village but also in the neighboring village, namely Gurung Sangiang Village.

Illegally organized acquisition

Somewhat different from the experience of agrarian transformation in Perembang, it can be said that the socio-economic life of the Dayak people in the villages of Bedaha and Tanjung Raya has never been marked by shocks of agrarian social conflict as a result of the penetration of oil palm plantation industrialization. The customary land ownership rights of the Dayak Kubink community in Bedaha Village and the Dayak Melahui community in Tanjung Raya Village were disturbed when the local government through the local Land Office issued a location permit (inlok) to PT. LJA to build shelters or company offices and oil palm plantations. Based on the location permit, PT. LJA obtained a location in a village with a concession area of 14,629 hectares which includes land in the villages/sub-districts of Tanjung Raya, Bedaha, Pagar Lebata, Batu Ketebung, Tekungai, Tellan Sahabung, Buntut Ponte in Serawai District. Procedurally, this company has indeed gone through the stages of obtaining permits, as well as the feasibility study process in the context of preparing the AMDAL (Analisa Mengenai Dampak Lingkungan) to the dissemination of the results of the AMDAL study. However, in parallel with the procedural process, at the same time, it turned out that the company was carrying out a large-scale excavation of land.

For the people of Tanjung Raya, the excavation process is a legal activity, because according to information submitted by a local village official, land clearing activities for the need for road preparation, construction of shelters or company offices and oil palm plantations, are territorially included in the administrative area of Tanjung Raya Village. However, under the observation of the Bedaha people, the excavation process was a process of land grabbing that was carried out under duress and illegally, because it seized land that was included in the space owned by the Dayak Kubink community in Bedaha. In addition, the activities of measuring the land up to the excavation of the land were not under the official knowledge of the government and traditional institutions of Bedaha Village, even though previously PT. LJA once conducted socialization regarding the oil palm plantation development plan. This is known from the chronological report on the land conflict between the Bedaha community and PT. The LJA issued by the Bedaha Village Government and the Bedaha Village Traditional Management are as follows:

On January 5, 2021, there were reports of community members farming near the company. PT. LJA carried out large-scale evictions in the Bedaha Village area. On January 16, 2021 there was another report from Bedaha community members that PT. LJA carried out large-scale land clearing from the heroditis point or boundary to the edge of the Bedaha community’s fields. So, on the night of January 17, 2021, the village head together with the customary management invited the entire community to hold a deliberation. In the deliberation, a joint agreement arose that the mass should be lowered to check the field. Then on January 18, 2021 village officials together with traditional administrators and with residents with a total of 58 personnel, went to the field. It turned out that after arriving at the field, the residents’ reports on January 16, 2021 were true. And, after the residents came to the field, a General Manager of PT. LJA whose name is “W” runs away and hides and is not responsible for his attitude which harms others. After the residents of Bedaha came to the nursery, we from Bedaha asked the residents of Tanjung Raya firmly and loudly, it turned out that the head of the village of Tanjung Raya was the mastermind behind the sale of the land which was still in the Bedaha village area. Then the Bedaha community members returned from the camp and headed to the land that had been evicted by PT. LJA. There, we Bedaha community members together with their GM took documentation as evidence of checking in the field. And, in that field, we, the Bedaha community, were threatened by one of the residents of Tanjung Raya with a naked machete.

At that time, at the end of 2019 approaching 2020, the company PT. LJA entered Tanjung Raya. They do socialization. At that time, the location permit was issued in February 2020. So, before the location permit was issued, they had conducted socialization. At that time the company invited residents to go into the forest to see the potential of Tanjung Raya. Company people bring GPS. They asked village people for directions on the village boundaries. The people invited were company recruits, and without the knowledge of the village government. These people include Her (a resident of Tanjung Raya, a company employee), Kas (a villager recruited by the company because he knows about GPS), As (former hamlet head). PT. LJA to the village administration only orally, never obtaining an official permit, and in writing. Companies recruit themselves. As a result, after going in and out of the forest (brought drone and GPS) a potential area of 1510 hectares of land to be handed over to the company emerged. Because the area is large, they asked to add it to 2,500 hectares. That means those who know the potential of the land are company people, not Tanjung Raya people. The land potential is in the form of communal land. (S, Tanjung Raya Village Apparatus, 8 March 2022)

Neither the village government nor the BPD was involved. All done by company people. Those who engineer the minutes of buying and selling. The village party only knows, the village party is forced. Because the elements are met, the witnesses have signed, the seller-buyer have signed, they both agree. We have forbidden the public not to sell land. They still sell secretly. That’s where the bastards of the company are. (S, Tanjung Raya Village Apparatus, 8 March 2022)

Pragmatically organized acquisition

Territorialization practices are defined as the strategies adopted by modern states in controlling resources. Here the state separates resource control based on economic and political zoning, regulates humans with resources in certain units and makes regulations to regulate who is allowed and who is not allowed to use or benefit from these resources (Kumar & Kerr, Citation2013). One of the territorialized policy practices implemented by the Sintang Regency government is carrying out a policy agenda for forming new villages, both in the sense of merging villages into one village, as well as dividing villages.

The policy of establishing and expanding villages in Serawai Sub-District is normatively motivated by the desire to build regional prosperity from the village, given the unequal ratio between area and population. In Regional Regulation Number 19 of 2011 it is stated that village formation is an effort to provide services and realize improvements in governance, implementation of development, community development, development and empowerment of village communities in an integrated, effective and sustainable manner as well as in the context of more effective and efficient village management. in the sub-district area of Sintang Regency. The question is then, how far the effectiveness and efficiency of the implementation of the policy.

In general, the implementation of the village formation and village expansion policies succeeded in forming a new village government organizational unit. However, this policy failed to resolve village boundary disputes. The government does not pay serious and sustainable attention in regulating, confirming and stipulating changes to village boundaries, causing disputes over village boundaries between villages to continue to drag on. In fact, changes in the territorial area of a village affect the position and authority of the village over the residents’ lands within it. Tanjung Raya Village and Bedaha Village are two of the many villages that were split, which until 2022 are still in a village boundary dispute relationship. A village official expressed disappointment from the implementation of the new village formation and expansion policy as follows:

The chaotic village boundaries caused everyone to be in a state of conflict, why did this happen, because at that time many people stumbled over political interests. Even those that don’t have enough territory can bloom. They dare to borrow first to meet the requirements, for example Bere Village, Batu Ketebung Village do not have an area, but they can bloom. Equally important, the village expansion technical team from the district did not attach a coordinated map, only a manual map. If it’s a manual map, we don’t know if there is overlap. Supposedly, the absolute conditions for the village area to be divided really exist and can be accounted for. If each division team, each village submitted village maps according to their area, then verified, of course the area boundaries would not overlap, but the district administration did not work like that. Finally, the legality of the boundaries becomes unclear. There should be no fuss between villages about boundaries at this time. I said, in the village boundary case it was none other than the district division team that we blamed.

On the other hand, according to the Bedaha Village accusation, according to the Tanjung Raya Pemdes, some of the areas claimed by the Bedaha Pemdes are part of its political territory, are included in the Tanjung Raya territory. The Tanjung Raya Village Government has a more valid legal and historical basis. Precisely the historical claims put forward by Bedaha Village do not have a strong historical basis for arguments. In the history of land tenure, it was the Dayak people from Tanjung Raya Village who for the first time opened, controlled and managed the land. An informant from the Tanjung Raya Village Government explained as follows.

The majority of the Dayak and Malay ethnic groups are farmers. The Tanjung Raya area, which covers 83 square kilometers, was once a forest bordering Bedaha. The natives of Tanjung Raya (Malay and Dayak tribes) then used it for shifting cultivation, some of the former fields were privately owned and some were left for free. On the other hand, outsiders from the Tanjung Raya area, outsiders (including the Bedaha), if they want to manage it, are borrowing (not allowed to make personal adjustments). But now and then, the people of Bedaha claim that their former farming areas are borrowed and used as their property. Even though legally and administratively, according to the people of Tanjung Raya, the field is included in the Tanjung Raya area. Things like this were never fussed over before investors came in. After the investors came in, the land value went up, causing chaos in the community. To be honest, if we want to go back to legislation, companies cannot buy and sell offhand. But this company is naughty, using free trade documents, in the end the residents don’t have plasma. Even though the company license is a partnership license.

From the information above, it is clear that the dispute involving Tanjung Raya Village and Bedaha Village was not only related to differences in village boundaries due to the village division policy, but also related to arguments over the history of land tenure and rising land prices due to the entry of the oil palm plantation industry. In the view of the Pemdes of Tanjung Raya, from a review of history and origin rights, the Bedaha people may manage the land but do not have the right to control it, because the historical background is very clear that it was the Bedaha people who borrowed the land from the Tanjung Raya people. Against this argument, the people of Bedaha Village do not accept it, because they feel they have managed it for a long time and it has been passed down from generation to generation.

The money of four billion that has been submitted by PT. LJA to Tanjung Raya Village, eventually disputed by Bedaha Village. Finally, the dispute between PT. LJA, Bedaha Village and Tanjung Raya Village dragged on until the conflict finally escalated to the legal area. In response to the Bedaha Village protest, PT. LJA then reported the Village Government to the legal institution (Police) of Sintang on charges of fraud. An informant conveyed the following information:

Now the social impact is destroyed, Tanjung Raya village and Bbedaha claim each other, fence each other. In the end, the company even made a report to the police, which was reported to be Tanjung Raya people, as if Tanjung Raya had relinquished 2,500 hectares of communal land that seemed not to belong to Tanjung Raya, because parties from Bedaha and Begori villages were demanding their land. So, Tanjung Raya was declared to have defaulted on the land agreement that had been released to the company. Their report is ongoing, now there are residents of Tanjung Raya being summoned one by one as witnesses over the 4 billion land compensation money transaction. They have written to the Tanjung Raya Village government, stating that the company had no knowledge of any lawsuits from Bedaha Village.

Research contributions

Finally, from the review of the land dispute involving the Dayak community and large-scale plantation companies in Sintang District above, it may provide insight into the existence of latent threats that accompany the process of integrating modern oil palm plantation systems into villages. This is caused by the still domination of the state and corporations which do not recognize the existence of rights of territorial origin built by the Dayak community. But the state, together with the market, has actually destroyed customary territorialisation, which actually contains reliable social values and norms to protect the life and livelihood of the Dayak community. When the Indonesian government issued the Village Law (No. 6/2014) which included developing a mission to defend customary rights, it was also unable to restore the supremacy of customary law.

It is hoped that the review of cases and lessons learned from agrarian conflict in this paper can contribute positively to academic debates in the science of land law, rural economics and public policy, particularly regarding land acquisition services for the oil palm plantation industry. The results of research using a conflict theory approach enrich and complement the debate on land disputes, land grabbing and agrarian conflicts in oil palm plantations which have recently been raised as research themes in rural sociology. Especially for the development of political ecology knowledge, this paper presents the fact that there is dominant political interference controlling the direction of market-oriented land use.

Conclusion

Land is the main capital needed by an oil palm plantation company, in addition to money and labour. To fulfill the need for land, large-scale oil palm plantation companies use state power. Companies take advantage of land concession policy opportunities such as location permits and HGU. The granting of location permits and HGU to these companies gives companies the right to create zoning or develop territorialization so that companies can control land according to calculations of economic production and in accordance with the area provided by the state. The implication of this policy is the isolation of the Dayak community’s rights and space for movement from their land on one hand. But it provides a large space for oil palm plantation companies to control the lands of the Dayak community on the other side.

Relations between state power and the Dayak community are dynamic, experiencing ups and downs. However, in the history of the development of national governance, the existence of indigenous communities and their government has always been sidelined. Moreover, when the state attaches a unit of indigenous peoples with a modern government called the official village. The existence of the Village Law, which seeks to restore customary rights, is also unable to restore the supremacy of the Dayak customary government. The power of the village government in the four research location villages shows a pattern of strong alignment with the company, rather than the Dayak community units. This is known from the existence of formal leadership support from the village head and the inclusion of oil palm plantation development plans in the village development planning policy documents. This support facilitated the process of land acquisition by the Dayak community by the company while reducing the local resistance of the Dayak community to the company.

Acknowledgements

The research and substances of this paper is an integral part of the process of writing a doctoral dissertation (S3) that currently pursuing at the Rural Sociology Study Program, Faculty of Human Ecology, Bogor Agricultural University (IPB). The dissertation has the title ‘Villages and Indigenous Peoples in the Flow of Agrarian Transformation and Oil Palm Expansion’. Supervised by: Prof. Dr. Arya Hadi Dharmawan, Dr. Titik Sumarti dan Prof. Dr. Mochammad Maksum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kharis Fadlan Borni Kurniawan

Kharis Fadlan Borni Kurniawan received Doctor of Sociology from IPB University in January 2024. Currently, he is still working as an expert for the Ministry of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia.

Arya Hadi Dharmawan

Arya Hadi Dharmawan is a Professor and senior lecturer at The Department of Communication and Community Development Sciences, Faculty of Human Ecology, Bogor Agricultural University.

Titik Sumarti

Titik Sumarti a Doctor and senior lecturer at The Department of Communication and Community Development Sciences, Faculty of Human Ecology, Bogor Agricultural University.

Mochammad Maksum

Mochammad Maksum is a Professor and senior lecturer at The Department of Agro-Industrial Technology, Gadjah Mada University.

References

- Acosta, P., & Curt, M. D. (2019). Understanding the expansion of oil palm cultivation: A case study in Papua. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219(2019), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.029

- Aprianto, T. C. (2006). Perjuangan Landreform Masyarakat Perkebunan Partisipasi Politik, Klaim dan Konflik Agraria di Jember. STPN Press.

- Bedner, A. (2016). Indonesian land law: Integration at last? And for whom? In J. F. McCartthy & K. Robinson (Eds.), Land & development in Indonesia searching for the people’s sovereignty. ISEAS Publishing.

- Berenschot, W., Dhiaulhaq, A., Afrizal., & Hospes, O. (2023). Kehampaan Hak Masyarakat vs Perusahaan Sawit di Indonesia. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

- Bottazzi, P., Goguen, A., & Rist, S. (2016). Conflict customary land tenure in rural Africa: Is large-scale land acquisition a driver of ‘institutional innovation’? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(5), 971–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1119119

- Brad, A., Schaffartzik, A., Pichler, M., & Plank, C. (2015). Contested territorialization and biophysical expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. Geoforum, 64(2015), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.007

- Davidson, J. S., Henley, D., & Moniaga, S. (2007). Adat in Indonesian politics. Emilius Ola Kleden and Nina Dwisasanti. 2010. Indonesian Torch Library Foundation and KITLV: Jakarta.

- de Vos, R. E. (2016). Multi-functional lands facing oil palm monocultures: A case study of a land conflict in West Kalimantan. Indonesia. ASEAS – Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 9(1), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2018.1522595

- de Vos, R. E. (2018). Counter-Mapping against oil palm plantation: Reclaiming village territory in Indonesia with the 2014 Village Law. Critical Asian Studies, 50(4), 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2018.1522595

- Dharmawan, A. H., Mardiyaningsih, D. I., Komarudin, H., Ghazoul, J., Pacheco, P., & Rahmadian, F. (2020). Dynamics of rural economy: A socio-economic understanding of oil palm expansion and landscape changes in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land, 9(7), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9070213

- Dharmawan, A. H., Mardiyaningsih, D. I., Rahmadian, F., Yulian, B. E., Komarudin, H., Pacheco, P., Ghazoul, J., & Amalia, R. (2021). The agrarian, structural and cultural constraints of smallholders’ readiness for sustainability standards implementation: The case of Indonesian sustainable palm oil in East Kalimantan. Sustainability, 13(5)2021, 2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052611

- Dharmawan, A. H., Nasdian, T. F., Barus, B., Kinseng, R. A., Indaryanti, Y., Indriana, H., Mardianingsih, D. I., Rahmadian, F., Hidayati, H. N., & Roslinawati, A. M. (2019). Readiness of independent palm oil farmers in ISPO implementation: Environmental issues, legality and sustainability. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 17(2), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.14710/jil.17.2.304-315

- Dhiaulhaq, A., & McCarthy, J. F. (2019). Indigenous rights and agrarian justice framing land conflicts in Indonesia. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 21(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2019.1670243

- Eko, S., Barori., & M., Hastowiyono. (2017). Old country new village. Postgraduate – STPMD “APMD”.

- Fargione, J., Hill, J., Tilman, D., Polasky, S., & Hawthorne, P. (2008). Lan clearing and the biofuel carbon debt. Science, 319(5867), 1235–1238. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152747

- Fitzherbert, E. B., Struebig, M. J., Morel, A., Danielsen, F., Bruhl, C. A., Donald, P. F., & Phalan, B. (2008). How will oil palm expansion effect biodiversity? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(10), 538–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.012

- Gerber, J. F. (2011). Industrial tree plantation conflicts in the South: Who, how and why? Global Environ. Change, 21(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-006-9080-1

- Germer, J., & Sauerborn, J. (2008). Estimation of the impact of oil palm plantation establishment on greenhouse gas balance. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 10(6), 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-006-9080-1

- Habibi, M. (2021). Masters of countryside and their enemies: Class dynamics of agrarian change in rural Java. Journal of Agrarian Change, 21(4), 720–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12433

- Hadiz, V. R. (2022). Localization of Power in post-authoritarianism Indonesia. KPG is working with ARC UI and Kurawal Foundation.

- Hall, D. (2011). Land grabs, land control, and Southeast Asian crop booms. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(4), 837–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.607706

- Hall, D. (2015). Primitive accumulation, accumulation by dispossession and the global land grab. Third World Quarterly, 34(9), 1582–1604. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.843854

- Hardiyanto, B. (2020). Politics of land policies in Indonesia in the era of president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Land Use Policy, 101, 105134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105134

- Hooijer, A., Hosten, H., Silvus, M., & Page, S. (2006). PEAT-CO2emission from drained peatlands in SE Asia. Report R&D Project Q3943/Q3684/Q4142. WL Delft Hydraulics in Cooperation with Wetland International & Alterra Wageningenur.

- Kartodiharjo, H., & Cahyono, E. (2021). Agrarian reform in Indonesia: Analyze concepts and their implementation from a governance perspective. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika (Journal of Tropical Forest Management), 27(te), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.7226/jtfm.27.te.1

- Koh, L. P., & Wilcove, D. S. (2008). Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity? Conservation Letters, 1(2), 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2008.00011.x

- Kumar, K., & Kerr, J. M. (2013). Territorialization and marginalization in the forested landscape of Orissa, India. Land Use Policy, 30(1), 885–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.06.015

- Li, T. M. (2017). After the land grab: Infrastructure violence and the “mafia system” in Indonesia’s palm oil plantation zones. Geoforum, 96, 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.10.012

- Marti, S. (2008). Losing ground the human impacts of palm oil expansion. Friends of the Earth, LifeMosaic in collaboration with Sawit Watch Indonesia. Wales and Northern Ireland.

- McCarthy, J. F., & Cramb, R. A. (2009). Policy narratives, engagement of land holders, and oil palm expansion on the Malaysian and Indonesian frontiers. The Geographical Journal, 175(2), 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2009.00322.x

- McCarthy, J. F., Vel, J. A. C., & Afiff, S. (2012). Trajectories of land acquisition and enclosure: development schemes, virtual land grabs, and green acquisitions in Indonesia’s Outer Islands. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 521–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671768

- Mizuno, K., Fujita, M. S., & Kawai, S. (2016). Catastrophe & regeneration in Indonesia’s peatlands: Ecology, economy & society. NUS Press.

- Rachman, N. F. (2015). Call of the homeland: A critical review of the devastation of Indonesia. Literacy Press.

- Reijnders, L., & Huijbregts, M. A. J. (2008). Palm oil and the emission of carbon based greenhouse gases. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(4), 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.07.054

- Schoenberger, L., Hall, D., & Vandergeest, P. (2017). What happened when the land grab came to Southeast Asia? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(4), 697–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1331433

- Tarigan, S. D., & Sunarti Widyaliza, S. (2015). Expansion of oil palm plantations and forest cover changes in Bungo and Merangin Districts, Jambi Province, Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Science, 24(2015), 199–205.

- van Vollenhoven, C. (1923). Indonesians and their Land. Soewargono. STPN Press.

- Vandergeest, P. (1996). Real villages: National narratives of rural development. Temple University Press. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1814.5602

- Yulian, B. E., Dharmawan, A. H., Sotarto, E., & Pacheco, P. (2017). The dilemma of livelihood for rural households around palm oil plantations in East Kalimantan. Sodality Journal, 5(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.22500/sodality.v5i3.19398

- Zoomers, A. (2010). Globalization and foreignization of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(2), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066151003595325