?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

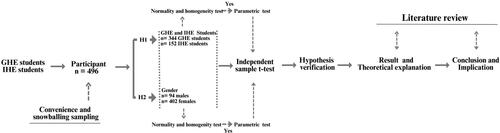

Most universities in Indonesia can be categorized as general higher education (GHE) and Islamic higher education (IHE). This study aimed to investigate and compare the factors influencing the selection of GHE and IHE on Kalimantan Island, the third-largest island in the world. This study used convenience sampling techniques to determine participants. There are 344 GHE students and 152 IHE students. A questionnaire was used to collect data, which was then distributed online and evaluated using independent sample t-test results to identify differences between GHE and IHE. This research found that reputation and quality are the most critical factors in selecting a college. When choosing a college, GHE students are more of a university’s reputation and quality focus. It means GHE students are more career-focused than IHE students. This study found that men prefer the scale and structure of the campus over women. Therefore, we did not find statistically significant differences between men and women in choosing a university. This study suggests that higher education, particularly IHE, should adapt university development to the labor market’s needs and student candidates’ needs.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

The higher education (HE) landscape in Indonesia predominantly comprises two distinct classifications: general higher education (GHE) regulated under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (MECRT), and Islamic higher education (IHE) overseen by the Ministry for Religious Affairs (MoRA) (Latief, Citation2022). The educational landscape of IHE in Indonesia materializes through three principal institutions: colleges for Islamic studies, institutes for Islamic studies and state Islamic universities. Furthermore, these Islamic universities often incorporate general science and technology departments. The colleges and institutes specializing in Islamic studies predominantly focus on Islamic teachings. Islamic universities, as highlighted by Suharto and Khuriyah (Citation2016), can offer comprehensive programs that interconnect science, technology and religious studies Hence, the prevailing ethos within state Islamic universities in Indonesia centers around the harmonious integration of scientific and technological disciplines with the teachings of Islam.

In short, IHE stands on par with GHE in addressing labor market requirements once it evolves into a university. The focal point within IHE revolves around integrating scientific disciplines with the teachings of Islam. Adapting educational curricula to suit students’ prospective career paths constitutes implementing a market-oriented approach. Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka (Citation2010) state that GHE adopts a market-oriented strategy by meeting students’ diverse needs and preferences. In line with this perspective, Suyadi et al. (Citation2022) assert that IHE must harmonize with labor market demands, thereby positioning itself to compete with GHE in employment opportunities.

Universities must comprehend the market in order to accommodate market demands. Regarding the demand issue, universities must comprehend the factors that influence student enrollment decisions (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2006). Numerous studies demonstrate the factors that influence students’ decisions. Personal interest in the study program, enrollment rates, city location of the university, campus appearance, reputation and perception of quality, resources and facilities are the determining factors, according to students (Heathcote et al., Citation2020). The selection of a university is determined by the desire to acquire specialized knowledge and information (Navratilova, Citation2013). According to students, the availability of social activities, social and cultural facilities in the city/location, and a variety of study options influence the selection of a university (Constantinides & Stagno, Citation2012). Besides, in college, the availability of the desired field is the most crucial factor (Price et al., Citation2003). The cost of residential mobility and post-graduation employment is a consideration for college applicants (De Fraja & Iossa, Citation2002). The selection of an educational institution depends on ideological (i.e. religious and pedagogical), quality, geographical (i.e. distance) and non-educational factors (Denessen et al., Citation2005).

In the UK, research on choice factors shows that the factor of choosing a university is personal interest in the field of study; entry rates; appeal of city/region of institute—particularly in how it may relate to present living requirements; appeal of institute itself—particularly with relation to hands-on experience of site visits; reputation and any perception of quality; resources and facilities—especially for the more specialist provision (sport, sciences, arts, etc.) (Heathcote et al., Citation2020). Medical students in the United States opt for specific specializations due to considerations related to their preferred lifestyle (Dorsey et al., Citation2003). The research does not show differences between different types of universities. In Vietnam, job opportunities, admission counseling and university reputation are the three main factors for choosing a university (Hai et al., Citation2023). Future job prospects, teaching quality, staff expertise and course content are factors in choosing universities in Vietnam (Le, Robinson, et al., Citation2020). The study in Nigeria found that personal interest greatly influenced students’ decisions, followed by parental influence, university reputation, university ranking and fees (Adefulu et al., Citation2020). In Zambia, the main factors in choosing a university are teaching quality, fees, course availability, facilities and employability (Kayombo & Carter, Citation2019). In general, graduate employment opportunities are a factor that is always proven in every study.

Moreover, gender exerts varying effects on university selection factors. Notably, the inclination toward vocational education after high school remains consistent across genders (Stoll et al., Citation2021). However, discernible differences between male and female students emerge during class selection and registration (Othman et al., Citation2019). It is pertinent to note the underrepresentation of women in specific scientific domains (Leslie et al., Citation2015), alongside evident disparities in the choice of medical specialties between genders (Asaad et al., Citation2020).

In Islamic countries (members of the Organization of Islamic Countries), the university’s reputation significantly influences the selection of HE institutions. In Pakistan, for instance, two primary factors influencing the choice of a business field are reputation and employment prospects (Naveed & Khurshid, Citation2020). Similarly, in the United Arab Emirates, the crucial factors in selecting a university include the learning environment, cost considerations, and institutional reputation (Ahmad & Hussain, Citation2017). In Malaysia, the key factors determining university selection are customer focus, facilities (Padlee et al., Citation2010), academic quality, campus environment and personal characteristics (Sidin et al., Citation2003). Mourad (Citation2011) concluded that prospective students in Egypt choose universities based on reputation due to their limited knowledge of universities in detail, a trend similar to that observed in Turkey. Future career expectations and the quality and popularity of university programs are essential factors influencing student choices in Turkey (İlgan et al., Citation2018). In Kyrgyzstan, the primary determinants impacting the selection of universities are economic considerations, the quality of education and the expertise of academic staff (Najimudinova et al., Citation2022).

In the context of IHE in Indonesia, the study Sholehuddin et al. (Citation2020) investigates parents’ perceptions of senior high school students about Islamic universities. Other studies show a varied focus of study. The main factors in choosing a private Islamic university are facilities and tuition fees (Kholis & Kartika, Citation2015; Mulyono & Hadian, Citation2019). Cost weakly correlates with high school students’ enrollment intention in GHE and IHE. Ad elements on IHE Instagram affect the intent to enroll in IHE through engagement as mediators (Juhaidi, Fuady, et al., Citation2024). Still, utility and possibility of success in learning in GHE than in IHE are mostly associated with enrollment intention of high school students (Juhaidi, Ma’ruf, et al., Citation2023). Department and accreditation are the most correlated factors with interest in GHE and IHE (Fadhli et al., Citation2023). Interest, motivation and expected work are factors in choosing the Islamic economics department (Rusandry & Samsuddin, Citation2023). Previous studies on IHE in Indonesia explore parental perceptions, facilities and tuition fees factor, enrollment intentions on GHE and IHE and departmental considerations in choosing universities. The studies still do not explore the comparison of factors choosing GHE and IHE in the context of gender from the perspective of their students.

The prevailing research on university choice factors across various countries like the UK, Vietnam, Nigeria, Zambia and Indonesia has extensively explored determinants influencing students’ selection of universities. However, a conspicuous gap exists in these studies as they are yet to delve into the discernible differences in choice factors considering the specific types of HE institutions and gender. This gap is particularly significant in Islamic countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Egypt, Pakistan, Turkey and others globally, where multiple educational institution types coexist. The ongoing research aims to bridge this gap by delving into and scrutinizing the divergent factors affecting the selection of GHE and IHE institutions. The study seeks to unearth nuanced variations in the intricate choice criteria between GHE and IHE and explore the connection between gender and the factors impacting HE institution choice, an aspect not thoroughly examined in earlier studies. By doing so, this research aims to offer comprehensive insights into the determinants influencing student decisions, assisting Islamic higher education (IHE) institutions in refining their offerings to align with student expectations and enhancing their competitiveness in the Indonesian HE domain.

Based on the elaboration above, as pre-observation in this research, in 2023, there was a comparison of the number of new students between Lambung Mangkurat University (ULM) as the GHE and Antasari State Islamic University (UIN) as the IHE through the National State University Entrance Selection. UIN Antasari succeeded in attracting the attention of 1,531 new students through Ujian Masuk Perguruan Tinggi Keagamaan Islam Negeri (UM-PTKIN), while ULM experienced a significant surge in enrollment with a total of 11,000 new students through the same route, Seleksi Nasional Berdasarkan Tes (SNBT). This comparison reflects the differences in capacity and attractiveness of both in attracting prospective students to join and pursue HE at their respective institutions. This data make the author’s curiosity in finding the factors that influence prospective students in determining the campus of their choice. Next, the author will explore it by conducting in-depth research.

Furthermore, this study has a multifaceted purpose. It aims to analyze the choice factors between GHE and IHE, exploring the differences in factors influencing students’ selections. Additionally, it endeavors to identify the most influential elements guiding students’ decisions toward either GHE or IHE and plans to categorize participants into clusters based on these factors. Furthermore, the research aims to investigate the correlation between gender and the choice of HE institution, seeking to form initial insights into comparing the selection criteria for GHE and IHE in Indonesia. Ultimately, it aspires to contribute to a deeper understanding of the decision-making behavior of education service to consumers when picking a university, an imperative aspect for institutions to tailor their offerings to meet student and parental expectations (Azzone & Soncin, Citation2020). Consequently, this study is crucial in aiding both GHE and IHE institutions in understanding student behavior, thereby supporting course development to remain competitive in the Indonesian HE market.

Literature review

GHE and IHE in Indonesia

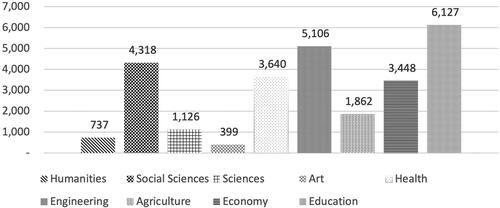

There are 4,523 HE institutions in Indonesia, and 384 are IHE. They offer 40,602 study programs in total. There are currently 95,34,695 students enrolled in these programs. The departments can be categorized as depicted in .

Figure 1. Number of departments by field.

Source: Higher Education Database at https://pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id/

In Indonesia, state HE institutions are predominantly categorized into two main groups: GHE and IHE. Traditionally, IHE has been closely associated with Islamic religious studies and has served the specific employment demands within the Islamic field, for example, Islamic teachers and judges at Islamic religious courts. The Presidential Decree of the Republic of Indonesia Number 11 of 1960, specifically in Article 2, outlines the establishment of State Islamic Institutes (IAIN) with the primary objective of providing advanced education and serving as a hub for advancing Islamic knowledge (Presidential Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia on the Establishment of the State Islamic Institute, Citation1960).

The transformation of IAIN into universities has played a crucial role in expanding the academic reach of Islamic education, making it more accessible and engaged on an international scale (Abdullah, Citation2017a). Over two decades, as these institutions have transitioned into universities, departments have been simultaneously developed tailored to meet job market demands. The opening of the discipline of science and technology will prepare Muslim leaders who master Islamic tradition and modernity (Lukens‐Bull, Citation2001). IHE has established departments geared toward practical career-oriented training to cater to students’ professional needs, such as science and technology. The opening of the department in the field of general science is limited to about 30%–40% of the total departments in the university (Regulation of the Minister of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia Number 15, Citation2014). However, IHE which is still in the form of a state college for Islamic studies (STAIN) or state institute for Islamic studies (IAIN) can only organize Islamic studies.

This is different from GHE which has the authority to open a general science department without a limit on the number. Islamic religious education is only given in the curriculum as a subject taught for one semester. The difference between GHE and IHE in Indonesia can be seen in .

Table 1. Differences between State GHE and IHE in Indonesia.

Moreover, public Islamic universities cannot exclusively position themselves solely dedicated to Islamic religious education but also offer the same fields of science as public universities. Islamic universities (IHE) and general university (GHE) institutions alike can provide academically relevant departments, such as science and technology, according to the demands of the job market. Consequently, IHE must compete within their own category and across the broader spectrum of GHE institutions. Despite their evolution into universities, a common perception persists among the public that Islamic universities primarily focus solely on Islamic religious sciences. For instance, as cited by Kraince, there is a prevalent belief that IHEs primarily prepare students to become Islamic studies educators, serve in Islamic boarding schools, or take on roles as scholars or mosque leaders (Kraince, Citation2007).

Therefore, the hypothesis of this study is

H1: There is no significant difference between the factors that influence IHE students’ university selection and those that influence GHE students’ university selection.

Factors for choosing a college

Universities are market-oriented due to competition, with quality and support system requirements rising to meet rising market demands (Vaikunthavasan et al., Citation2019). Universities must compete for student enrollment. As service providers, universities must know market demand to offer learning services that align with market needs. Students do not consider the university’s reputation as a deciding factor when choosing a university; however, career prospects are the most critical factor (Le, Le, et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, the selection of a university is influenced by its service quality, brand image, and reputation (Haniya & Said, Citation2022). University selection is inextricably influenced by employment prospects (Peck, Citation2020). A university is selected in part based on the difficulty of its entrance examinations (Shah et al., Citation2013). Conversely, when selecting a learning-content-related study program, job prospects is the primary factor to consider (Anderson, Citation1999). After learning quality, job prospects is the primary motivation for students to pursue HE (Wiese et al., Citation2009). The quality of education is difficult for students to evaluate; therefore, job prospects is the most important factor to consider when selecting a college. Simões and Soares (Citation2010) suggested that the factors of choosing a college can be categorized as follows: (1) economic/econometric models, which view economic gain as the primary factor;(2) status attainment/sociological models, which explain that the factors of choosing a college are related to sociology and context variables; (3) combined models, which utilize both the rational approach of economic models and the sociological perspective (Simões & Soares, Citation2010).

Research has revealed that the reasons for choosing a university are related to gender. In commercial research, gender is a critical segmentation factor (Pascual-Miguel et al., Citation2015). HE institutions compete for students as consumers of their services even though they are not commercial enterprises. From childhood, boys and girls subjected to distinct social environments will develop distinctive social expectations and values, thus influencing college selection behavior (Chodorow, Citation1999). In India, for instance, boys learn to be more competitive and unemotional because they are expected to be the family provider, whereas girls learn to be more affectionate. After all, they are expected to be the family caregiver (Sreen et al., Citation2018).

Therefore, the second hypothesis of this study is

H2: There is a significant difference between the reasons women and men choose higher education.

Method

Research design

This quantitative study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teacher Training at Antasari State Islamic University Banjarmasin Indonesia (under reference number 129/Un.14/III.1.h/PP.00.9/7/2022). In this study, descriptive analysis is used. Other analyses use independent sample t-tests, tests, and K-means clusters. T-test is used to test whether there is a difference between two sample groups. They are the GHE student group, IHE student group and male and female student groups. K-means cluster is utilized to group participants into three clusters.

Participants

Data were collected using a questionnaire and distributed online. The questionnaire is created using Google Forms. The questionnaire link was distributed to students through WhatsApp messages in student in groups and privately. Participants spread the message in chains to their friends, who can become research participants. The link is sent accompanied by a request for willingness to become a participant by filling out the questionnaire that has been sent. Thus, they express their consent in writing to participate and then complete questionnaires.

Universities are selected by purposive sampling techniques based on similar characteristics. Universitas Lambung Mangkurat is a sample of state secular/non-religious/general universities in Indonesia. Antasari State Islamic University is a sample of a state Islamic university in Indonesia. These two universities are the most prominent universities of their type on the second largest island in Indonesia and the third largest in the world, Kalimantan Island. Purposive sampling techniques are used because sample characteristics are the same as all units of analysis (Rai & Thapa, Citation2015), such as management, regulations and academic focus. However, the need for a university sample is a limitation of this study.

The participants of this study amounted to 496 students consisting of 344 students from Lambung Mangkurat University Banjarmasin Indonesia and 152 students from Antasari State Islamic University Banjarmasin Indonesia. The participants consisted of 94 males and 402 females. The convenience sampling technique determined participants based on their ease of access (Sultan et al., Citation2019). The convenience technique assigns samples based on volunteerism to participate in the study (Lewin, Citation2005). The reason for choosing the technique is the convenience of reaching participants without meeting them, reducing research costs, saving time and reducing bias for speed, ease and cost-effectiveness. The sample of this study was students who received questionnaires and voluntarily participated in responding to the questionnaires. So, when they agreed to access the questionnaire link and respond to questions in the questionnaire, they expressed their consent to become research participants.

Snowballing sampling was also used to obtain research participants who were unknown and difficult to access (Leighton et al., Citation2021). After giving the response to the questionnaire, the participants then send to their friends in chains, demanding researchers access them. They will be completed when the data reach a minimal amount or has been saturated (Parker et al., Citation2019).

Measurement

The research used an instrument developed by Y.-F. Chen and Hsiao (Citation2009). The instrument is divided into four parts: university reputation and quality (items 1–6), emotional (items 7–11), function and convenience (items 12–17) and structure and scale (items 18–21). The response scale is 1–4 (strongly disagree–strongly agree). This study used a scale of 1–4 because it had no midpoints. Respondents can abuse midpoint to avoid uncomfortable feelings related to question items (Chyung et al., Citation2017). In addition, in psychological studies, there is a tendency for collective communities, such as Indonesia, to choose a midpoint, and in individualistic communities, the choice will tend to be extreme (C. Chen et al., Citation1995).

The question items are:

I chose my current university because it has a good reputation;

I chose the university where I am studying now because of the job prospects of graduates;

I chose the university where I am studying now because the name of the university is widely known;

I chose the university where I am currently studying because the lectures and other academic activities are in line with my expectations;

I chose the university where I am currently studying because of the faculties/study programs available;

I chose my current university because of the facilities and equipment on campus;

I chose my current university because of my emotional attachment to the university;

I chose my current university because it is open in its management;

I chose my current university because of the university’s promotion/socialization;

I chose my current university because of the extracurricular activities for students;

I chose my current university because of the religious sect/activities that suit me;

I chose my current university because of the convenience of transportation or the road to campus;

I chose my current university because the distance from my home to campus is in line with my expectations;

I chose my current university because other facilities around campus are in line with my expectations;

I chose my current university because the scholarships available were in line with my expectations;

I chose my current university because of the quality of the dormitories;

I chose my current university because the tuition fees are in line with my ability;

I chose the university where I study now because of the size of the campus;

I chose my current university because of the view of the campus;

I chose my current university because of the ratio of male to female students;

I chose my current university because of the library collection.

The research process is shown in .

We use the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z test to test data normality and the Bartlett Test to test data homogeneity. The two tests showed that the data were normally distributed and homogeneous. The test results can be seen in .

Table 2. Normality and homogeneity test.

Finding and discussion

Finding

Factors for choosing GHE and IHE

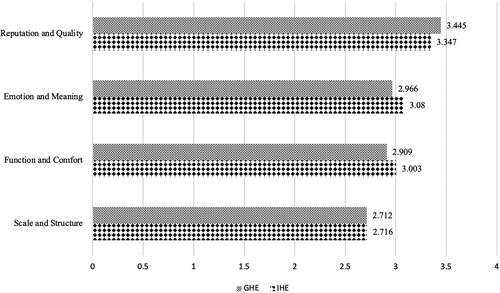

This research illustrates that the factors for choosing GHE and IHE are different. The highest mean () score is for the reputation and quality of the university. These results illustrate that the primary consideration for students in choosing a university is the reputation and quality of the university based on the mean (

). shows descriptive statistical results.

Table 3. Reasons for choosing a university.

The mean () scores of the two types of universities on the student reasons for choosing a college based on university reputation and quality are comparable. GHE students are more possible than IHE students to choose universities based on reputation and quality. It demonstrates that HE students choose colleges based on their reputation, employment opportunities, brand recognition and facilities. However, IHE students are expected to choose colleges based on emotion (promotion and religion) and function and comfort, such as cost. The overall comparison of the mean (

) score is shown in .

Figure 3. Comparison of factors for choosing a university.

Note. Results of data processing using SPSS V. 26.

IHE students are more possible than GHE students to choose universities based on emotional and meaning-based considerations. It demonstrates that IHE students choose universities based on the recommendations of family, friends and other notable individuals. The various extracurricular activities and the religious stream also influenced the decision to attend IHE. The religious factor is unsurprising because IHE’s branding is explicitly Islamic.

Functionality and convenience are additional determinants of university selection. GHE students are reasonable to base their decisions on function and convenience than IHE students. Students choose IHE because of the accessibility of transportation or roads to the college, the proximity to their homes, the availability of scholarships, the quality of the dorms, and the tuition fee. However, GHE students are more likely than IHE students to choose universities because of the surrounding support facilities.

Scale and structure are the final considerations when selecting a university. According to our survey, GHE students emphasize this factor more than IHE students when choosing a university. Scale and structure elements include the size and landscape of the campus, the ratio of female to male students, and the number of library collections.

Although the mean scores between factors differed, the statistical significance of the differences varied, as shown in . Independent sample t-test results show that the Sig (two-tailed) with a Sig < 0.05, it can be concluded that the factors of choosing IHE and GHE universities differ in significance level on university reputation and quality (X1) factor. The difference indicates that GHE is perceived to provide significantly more opportunities for employment or career than IHE. Students choose GHE more based on expectations of their career or job prospects than IHE students. Therefore, the overall factor, Asymp. Sig. (0.467 > 0.05) showed no significant difference in factors in choosing a university between GHE students and IHE students. This finding is the basis for rejecting H1. T-test results are shown in .

Table 4. Independent sample t-test results in factors of choosing a university.

Based on these factors, the university student segments can be grouped into three: career-oriented (cluster 1), emotionally-oriented (cluster 2) and environment-oriented (cluster 3). The results of the K-mean cluster of GHE and IHE are shown in .

Table 5. Clusters of university students.

Career-oriented is the cluster of students who choose the reputation and quality of the university as the main reason for choosing a university. These findings indicate that the GHE and IHE student segments are predominantly students who choose HE for career or job opportunities or career-oriented. It shows that the most critical factor is the reputation and quality of HE institutions. The related items in this factor include the HE reputation and reviews, career opportunities available to its graduates, HE recognition, program design and faculty.

Difference in choice related to gender

The research found that gender does not affect choice factors. The independent sample t-test result shows no significant difference in gender-related factors. The test result is shown in .

Table 6. Gender-related choice factor.

Statistical results of X4 (scale and structure) show that males prioritize physical condition, campus and library area and gender composition over female students. Overall score of Asymp. Sig (0.573 > 0.05) shows that female and male students do not differ in their reasons for choosing a university. Thus, the formulated H2, ‘There is a significant difference between women’s reasons for choosing university and men’s reasons for choosing university’, is rejected.

Discussion

The outcomes of this study reveal that the reputation and quality of HE institutions emerged as the primary factor influencing students’ decisions regarding their selection of HE institutions. This tendency emphasizes the students’ career-oriented orientation toward their prospective vocations or professional paths. In other words, students who choose HE because of reputation and quality are career-oriented. This finding is not surprising, as it is consistent with those who suggested that Generation Z considers cost, financial aid and post-graduation opportunities when selecting a college. Similarly, De Fraja and Iossa (Citation2002) indicated that employment after graduation is a factor that students consider when choosing a university. Expectations regarding post-graduation careers are related to university learning programs. Consequently, academic programs are a consideration when selecting a university. Keshishian et al. (Citation2010) also concluded that the choice toward a major is determined by career after graduation (Keshishian et al., Citation2010).

The research findings indicate that economic benefit is crucial in selecting an educational institution. This finding supports economic modeling perspectives. Economic or functional value advancement emerges as the foremost determinant in purchasing decision-making processes within economic or econometric models.(Simões & Soares, Citation2010; Watanabe et al., Citation2020). Economists construct their frameworks concerning higher institution choices by drawing upon the principles of human capital theory. Education serves as a fundamental catalyst in the accumulation of knowledge capital, thereby fostering enhanced earning capacities and contributing to the advancement of national economic growth (Hanushek & Woessmann, Citation2020). Econometric models posit that individuals formulate decisions regarding postsecondary education guided by considerations such as cost, prospective returns and the perceived value derived from various educational opportunities (Hu & Hossler, Citation1998). Students are disposed to invest in opportunities that augment their prospects for both personal advancement and economic prosperity (Holdsworth & Nind, Citation2006).

Erikson and Jonsson (Citation1996) developed a model to assess the future value of HE, which relies on students’ perceptions. Their framework suggests that when students make decisions regarding college selection, paramount consideration is given to the perceived utility (U) of the education provided. This principle is encapsulated in the equation . U signifies the comprehensive perception of educational worth. At the same time, p represents probabilities of learning success and B is post-graduation advantages. Cost (c), conversely, denotes the incurred costs associated with attending the institution. Accordingly, students opt for a college when the perceived benefits, encapsulated within pB, do not outweigh the incurred costs (c), a notion corroborated by Daniel and Watermann (Citation2018). This decision-making process is contingent upon assessments of learning success probabilities, employment prospects, incurred expenses and the overall perceived utility (U) of the educational experience post-consideration of these factors.

From the Expectancy-Value Model’s vantage point, an individual’s determination to opt for a specific university is intricately intertwined with the comprehensive evaluation of manifold attributes characterizing educational provisions. Within the paradigm of marketing theory, the selection of a product or service is contingent upon a meticulous assessment of diverse brand attributes and their perceived significance in the decision-making process (Kotler & Keller, Citation2012; Lim & Dubinsky, Citation2004; Mohanraj et al., Citation2018). This choice mechanism is markedly influenced by an individual’s cognitive appraisal of the anticipated consequences of their actions (Pligt & De Vries, Citation1998; Van Der Pligt & De Vries, Citation1998). The present inquiry substantiates the prominence of reputation and quality as pivotal attributes that engender favorable outcomes upon opting for either GHE or IHE. However, it is imperative to note that the decisional calculus regarding GHE or IHE transcends the mere consideration of reputation and quality. As posited by the Expectancy-Value Model, the selection of a college is predicated upon a holistic evaluation encompassing not only the reputation and quality of the institution but also three additional attributes, thus underscoring the multifaceted nature of this decision-making process.

Moreover, the investigation revealed a significant difference in career orientation between students at GHE and IHE institutions. Specifically, a lower proportion of career-focused individuals was observed among students at IHE institutions than those at GHE ones. The findings are relevant to previous studies on IHE. Most research on IHE focuses on the benefits of IHE as the center of Islamic studies worldwide, ignoring the significance of labor market demands. In order to promote Akhlaq and spiritual formation, Islamic education emphasizes not only the transfer of knowledge but also the formation of character and inculcation of Islamic values.(Syah, Citation2015). Nurcholis Madjid emphasizes morals as the center of Islamic education (Safitri et al., Citation2022). Nata and Sofyan (Citation2021) do not explicitly argue that Islamic educational institutions must consider labor market needs to be the first choice. Mu’is and Huda (Citation2022) did not explicitly propose that IHEs should offer HE that meets the needs of the labor market when confronting societal challenges 5.0. Jamaluddin et al. (Citation2019) recommended that IHEs utilize information technology to enhance quality. IHEs must foster the development of intellectual entrepreneurs, knowledge and innovation actors and economic expansion (Sonita et al., Citation2021). After becoming a university, IHEs will have more opportunities to participate in international forums, particularly those related to studies published in reputable journals (Abdullah). The article did not emphasize the significance of IHEs competing to meet labor market needs. Buckner (Citation2019) argues that HE institutions like IHE must educate for the global job market and society.

These studies demonstrate that IHEs are better known for meeting the international school community’s Islamic studies needs than the high school graduates’ needs. The international community only associates Islamic education with Islamic studies. Kadi (Citation2006) views Islamic education as an institution and a collection of mosques, kuttabs, and madrasas. Kadi presented the opinions of experts who believe Islamic education as an institution and collection does not prepare human capital for the labor market. IHE is not portrayed as an educational institution that contributes to preparing the workforce for the labor market’s requirements.

Nevertheless, students choose Islamic universities not because they want to learn Islam, which is IHE’s brand. The transition from an Islamic institute or college to an Islamic university is intended to meet the community’s needs and the labor market (Bashori et al., Citation2020). HE should be viewed as a provider of service products intended to generate exchanges, satisfy students’ expectations, and achieve organizational objectives (Helgesen, Citation2008).

This is also the reason in the Islamic world that students from other Islamic countries prefer universities in Malaysia to Islamic universities in Indonesia. Welch (Citation2012) concluded that Malaysian universities are more appealing to students from Islamic countries than Islamic universities in Indonesia. He erroneously equated universities in Malaysia and Indonesian Islamic universities. The more significant number of Muslim students worldwide choosing Malaysian universities is due to the availability of various study programs related to the job market’s needs, as well as English and Arabic as languages of instruction. Although Islamic universities in Malaysia and Indonesia integrate Islamic studies with science and technology, universities in Malaysia offer a variety of study programs in all scientific disciplines. The programs offered by the university are the main reason international students choose universities in Malaysia (Abduh & Dahari, Citation2011). In contrast, Islamic universities in Indonesia offer a limited selection of scientific disciplines.

The oldest State Islamic University in Indonesia, Syarif Hidayatullah State University, has 11 science and technology departments, and Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University Yogyakarta has 8 departments in the field of science and technology. The science and technology departments Alauddin State Islamic University Makassar owns are 17. Other universities, for example, Antasari State Islamic University Banjarmasin and Sultan Aji Muhammad Idris Samarinda, only have one department in science and technology. Mataram State Islamic University does not have a department in the field of science and technology (MECRT, Citation2023).

Based on information on the official university website, the department of science and technology at Islamic universities in Malaysia is more varied and numerous than at IHE in Indonesia. In Malaysia, 20 universities have faculty or department of Islamic Studies and science technology (Ismail et al., Citation2019). Universitas Kebangsaan Malaysia has 43 departments in the field of science and technology. Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia has 12 departments in science and technology, and Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin Malaysia has 28 departments. Universiti Sultan Azlan Shah has six departments in science and technology. Universiti Islam Selangor, which has turned into a university in 2022, has four departments in science and technology. In addition to the programs offered, the allure of international standard facilities and vital support services further enhances the appeal, fostering a desire among prospective students to be immersed in the Malaysian academic landscape (Padlee et al., Citation2010).

This study also discovered no significant difference between men and women regarding university selection factors. In other words, gender has no bearing on university selection factors. This finding contradicts previous research, which indicates that gender influences the choice of university (Asaad et al., Citation2020; Leslie et al., Citation2015; Othman et al., Citation2019). Males from low-educated families prefer universities because of opportunities in the job market (Ballarino et al., Citation2022). In the business sector, females are more influenced to purchase a product by its warmth (Xue et al., Citation2020). Men can be persuaded by the number of claims about a product, whereas women are more detailed and selective regarding advertising information (Papyrina, Citation2019). In the hospitality sector, women and men have different preferences regarding the color of their hotel rooms (Bogicevic et al., Citation2018). According to women, satisfaction with service quality is correlated with attire, whereas men find no correlation (Shao et al., Citation2004). These studies prove that women and men have distinct purchasing preferences for products and services. The deviation from previous research demonstrates that education services cannot be compared to other service products.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this investigation affirm that the main impetus driving students’ pursuit of HE lies in the reputation and quality of the university. Choices made based on the university’s reputation and quality underscore the prevailing career orientation among students. Notably, GHE students demonstrate a stronger tendency toward university reputation and quality compared to IHE students, with this difference unaffected by the students’ gender. It highlights the importance of IHE institutions, traditionally associated with Islamic studies, to broaden their academic offerings to encompass fields relevant to the labor market. As the range of study fields expands, opportunities and competitiveness for graduates of IHE institutions are expected to rise.

This finding will assist private and public Islamic universities in Indonesia develop institutions that adhere to Islamic values while meeting labor market demands. It will also assist policymakers in designing assistance that is relevant to the workplace. This study encourages future research examining these selection factors’ effects on students’ enrollment intentions.

This study is constrained by its sample, which exclusively comprises participants from two universities. Consequently, the generalizability of the research findings could be significantly enhanced, mainly if extrapolated to diverse settings. However, it is essential to note that the primary aim of this study is not to achieve broad generalization but to establish initial insights into the comparative factors influencing the selection of GHE and IHE institutions. This topic still needs to be explored in Indonesia and globally. Furthermore, the study advocates for future research endeavors to encompass a more extensive and diverse sample, encompassing geographical variations, university classification and participant demographics.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable and insightful feedback on my manuscript. I would like to express my gratitude to my colleagues, Hidayat Ma’ruf, Ridha Fadillah, Salamah, Shafiah and Risa Lisdariani. They have provided input in the revision process to improve my manuscript. I also express my gratitude to my students: Rissnawati, Siti Nurul Afiza, Umi Kulsum, Khairansah, Latifa and Padliannor. They helped a lot in distributing questionnaire online.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Ahmad Juhaidi, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahmad Juhaidi

Ahmad Juhaidi is an associate professor in Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teaching Learning, State Islamic University Antasari Banjarmasin Indonesia. He earned his Doctor’s Degree in Educational Administration, Indonesian Education University, Bandung, Indonesia. His research interests include educational marketing and economic and financing of education.

References

- Abduh, M., & Dahari, Z. B. (2011). Factors influencing international students’ choice towards universities in Malaysia (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2012407). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2012407

- Abdullah, M. A. (2017a). Islamic studies in higher education in Indonesia: Challenges, impact and prospects for the world community. Al-Jami’ah: Journal of Islamic Studies, 55(2), 1–17.

- Adefulu, A., Farinloye, T., & Mogaji, E. (2020). Factors influencing postgraduate students’ university choice in Nigeria. In E. Mogaji, F. Maringe, & R. Ebo Hinson (Eds.), Higher education marketing in Africa (pp. 187–225). Springer International Publishing.

- Ahmad, S. Z., & Hussain, M. (2017). An investigation of the factors determining student destination choice for higher education in the United Arab Emirates. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1324–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1099622

- Anderson, P. (1999). Factors influencing student choice in higher education. Perspectives: Policy & Practice in Higher Education, 3(4), 128–131.

- Asaad, M., Zayegh, O., Badawi, J., Hmidi, Z. S., Alhamid, A., Tarzi, M., & Agha, S. (2020). Gender differences in specialty preference among medical students at Aleppo University: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02081-w

- Azzone, G., & Soncin, M. (2020). Factors driving university choice: A principal component analysis on Italian institutions. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2426–2438. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1612354

- Ballarino, G., Filippin, A., Abbiati, G., Argentin, G., Barone, C., & Schizzerotto, A. (2022). The effects of an information campaign beyond university enrolment: A large-scale field experiment on the choices of high school students. Economics of Education Review, 91, 102308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102308

- Bashori, B., Prasetyo, M. A. M., & Susanto, E. (2020). Change management transformation in Islamic education of Indonesia. Social Work and Education, 7(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.25128/2520-6230.20.1.7

- Bogicevic, V., Bujisic, M., Cobanoglu, C., & Feinstein, A. H. (2018). Gender and age preferences of hotel room design. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(2), 874–899. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0450

- Buckner, E. (2019). The internationalization of higher education: National interpretations of a global model. Comparative Education Review, 63(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1086/703794

- Chen, C., Lee, S.-Y., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6(3), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00327.x

- Chen, Y.-F., & Hsiao, C.-H. (2009). Applying market segmentation theory to student behavior in selecting a school or department. New Horizons in Education, 57(2), 32–43.

- Chodorow, N. (1999). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. Univ of California Press.

- Chyung, S. Y. Y., Roberts, K., Swanson, I., & Hankinson, A. (2017). Evidence-based survey design: The use of a midpoint on the Likert scale. Performance Improvement, 56(10), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21727

- Constantinides, E., & Stagno, M. C. Z. (2012). Higher education marketing: A study on the impact of social media on study selection and university choice. International Journal of Technology and Educational Marketing, 2(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijtem.2012010104

- Daniel, A., & Watermann, R. (2018). The role of perceived benefits, costs, and probability of success in students’ plans for higher education. A quasi-experimental test of rational choice theory. European Sociological Review, 34(5), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy022

- De Fraja, G., & Iossa, E. (2002). Competition among universities and the emergence of the elite institution. Bulletin of Economic Research, 54(3), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8586.00153

- Denessen, E., Driessena, G., & Sleegers, P. (2005). Segregation by choice? A study of group‐specific reasons for school choice. Journal of Education Policy, 20(3), 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500108981

- Dorsey, E. R., Jarjoura, D., & Rutecki, G. W. (2003). Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA, 290(9), 1173–1178. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.9.1173

- Erikson, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (1996). Explaining class inequality in education; The Swedish test case. In R. Erikson & J. O. Jonsson (Eds.), Can education be equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective (pp. 1–64). Westview Press.

- Fadhli, M., Salabi, A. S., Siregar, F. A., Lubis, H., & Sahudra, T. M. (2023). Higher education marketing strategy: Comparative study of State Islamic High Education Institution and State Higher Education. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 11(3), 791. https://doi.org/10.26811/peuradeun.v11i3.896

- Hai, N. C., Thanh, N. H., Chau, T. M., Sang, T. V., & Dong, V. H. (2023). Factors affecting the decision to choose a university of high school students: A study in An Giang Province, Vietnam. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 12(1), 535. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v12i1.22971

- Haniya, O. K., & Said, H. (2022). Influential factors contributing to the understanding of international students’ choice of Malaysian higher education institutions: Qualitative study with a focus on expected benefits. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 9(2), 63–97. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe.1966

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2020). Education, knowledge capital, and economic growth. In S. Bradley & C. Green (Eds.), The Economics of Education (pp. 171–182). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00014-8

- Heathcote, D., Savage, S., & Hosseinian-Far, A. (2020). Factors affecting university choice behaviour in the UK higher education. Education Sciences, 10(8), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10080199

- Helgesen, Ø. (2008). Marketing for higher education: A relationship marketing approach. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 18(1), 50–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240802100188

- Hemsley‐Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2006). Universities in a competitive global marketplace: A systematic review of the literature on higher education marketing. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19(4), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550610669176

- Hemsley‐Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2010). Market orientation in universities: A comparative study of two national higher education systems. International Journal of Educational Management, 24(3), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541011031565

- Holdsworth, D. K., & Nind, D. (2006). Choice modeling New Zealand high school seniors’ preferences for university education. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 15(2), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v15n02_04

- Hu, S., & Hossler, D. (1998). The linkage of student price sensitivity with preferences to postsecondary institutions. In P. St. John (Ed.), The ERIC Collection of ASHE Conference Papers., 2–19. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED427593

- İlgan, A., Ataman, O., Uğurlu, F., & Yurdunkulu, A. (2018). Factors affecting university choice: A study on university freshman students. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Buca Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 46, 199–216.

- Ismail, N., Bakar, N. H., Abd Majid, M., & Kasan, H. (2019). Pengamalan hidup beragama dalam kalangan mahasiswa Institut Pengajian Tinggi Islam di Malaysia: Religious practice among students of Islamic Institutes of Higher Education (IPTI) in Malaysia. al-Irsyad: Journal of Islamic and Contemporary Issues, 4(2), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.53840/alirsyad.v4i2.57

- Jamaluddin, D., Ramdhani, M. A., Priatna, T., & Darmalaksana, W. (2019). Techno University to increase the quality of Islamic higher education in Indonesia. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(1), 1264–1273.

- Juhaidi, A., Fuady, M. N., Ramadan, W., & Ma’ruf, H. (2024). Instagram activities, engagement and enrollment intention in Indonesia: A case in the third largest island in the world. Nurture, 18(2), 435–455. https://doi.org/10.55951/nurture.v18i2.642

- Juhaidi, A., Ma’ruf, H., Tajudin, A., Fitri, S., & Hamdani, H. (2023). The perceived utility and university enrolment intention in Indonesia: Students perspective. Cendekia: Jurnal Kependidikan dan Kemasyarakatan, 21(2), 236–252. https://doi.org/10.21154/cendekia.v21i2.7364

- Kadi, W. (2006). Education in Islam—Myths and truths. Comparative Education Review, 50(3), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1086/504818

- Kayombo, K. M., & Carter, S. (2019). Understanding student preference for university choice in Zambia. Journal of Education Policy, Planning & Administration, 6(3), 1–21.

- Keshishian, F., Brocavich, J. M., Boone, R. T., & Pal, S. (2010). Motivating factors influencing college students’ choice of academic major. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(3), 46. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj740346

- Kholis, N., & Kartika, M. (2015). Factors influenced people in choosing university: A lesson from Islamic Economics Department UII. Millah, 15(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.20885/millah.vol15.iss1.art3

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2012). Marketing management (14th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Kraince, R. G. (2007). Islamic higher education and social cohesion in Indonesia. PROSPECTS, 37(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-008-9038-1

- Latief, H. (2022). The Masyumi networks and the proliferation of Islamic higher education in Indonesia (1945–1965). Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 178(4), 477–502.

- Le, T. D., Le, N. V., Nguyen, T. T., Tran, K. T., & Hoang, H. Q. (2022). Choice factors when Vietnamese high school students consider universities: A mixed method approach. Education Sciences, 12(11), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110779

- Le, T. D., Robinson, L. J., & Dobele, A. R. (2020). Understanding high school students use of choice factors and word-of-mouth information sources in university selection. Studies in Higher Education, 45(4), 808–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564259

- Leighton, K., Kardong-Edgren, S., Schneidereith, T., & Foisy-Doll, C. (2021). Using social media and snowball sampling as an alternative recruitment strategy for research. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 55, 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.03.006

- Leslie, S.-J., Cimpian, A., Meyer, M., & Freeland, E. (2015). Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines. Science (New York, N.Y.), 347(6219), 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261375

- Lewin, C. (2005). Elementary quantitative methods. In B. Somekh & C. Lewin (Eds.), Research methods in the social sciences (pp. 215–225). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Lim, H., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2004). Consumers’ perceptions of e‐shopping characteristics: An expectancy‐value approach. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(7), 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040410561839

- Lukens‐Bull, R. A. (2001). Two sides of the same coin: Modernity and tradition in Islamic education in Indonesia. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 32(3), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2001.32.3.350

- MECRT. (2023). Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, PDDikti - Pangkalan Data Pendidikan Tinggi, PDDikti - Pangkalan Data Pendidikan Tinggi. https://pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id/

- Mohanraj, P., Varadaraj, A., & Sengodan, A. (2018). Measurement of customers’ brand choice and brand loyalty expectancy value & Colombo–Morrison model approach. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 4(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.41.3003

- Mourad, M. (2011). Role of brand related factors in influencing students’ choice in Higher Education (HE) market. International Journal of Management in Education, 5(2/3), 258. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2011.039488

- Mu’is, A. , & Huda, A. M. (2022). Challenge of Islamic higher education in Indonesia (PTKIN) in Society 5.0. In Proceeding of International Conference on Islamic Education (ICIED), UIN Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang (pp. 465–476). http://conferences.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/icied/article/view/2041

- Mulyono, H., & Hadian, A. (2019). Factors affecting on rational choice of students in Muslim Nusantara Al-Washliyah University. International Research Journal of Management, IT and Social Sciences, 6(5), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.21744/irjmis.v6n5.692

- Najimudinova, S., Ismailova, R., & Oskonbaeva, Z. (2022). What defines the university choice? The case of higher education in Kyrgyzstan. Sosyoekonomi, 30(54), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.17233/sosyoekonomi.2022.04.03

- Nata, A., & Sofyan, A. (2021). Making Islamic university and Madrasah as society’s primary choice. Al-Hayat: Journal of Islamic Education, 4(2), 210. https://doi.org/10.35723/ajie.v4i2.150

- Naveed, S., & Khurshid, M. (2020). Factors influencing the university choice decision of business students at higher education level: A case from Pakistan. Hamdard Islamicus, 43(2), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.57144/hi.v43i2.46

- Navratilova, T. (2013). Analysis and comparison of factors influencing university choice. Journal of Competitiveness, 5(3), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2013.03.07

- Othman, M. H., Mohamad, N., & Barom, M. N. (2019). Students’ decision making in class selection and enrolment. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(4), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-06-2017-0143

- Padlee, S. F., Kamaruddin, A. R., & Baharun, R. (2010). International students’ choice behavior for higher education at Malaysian private universities. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 2(2), 202. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v2n2p202

- Papyrina, V. (2019). The trade-off between quantity and quality of information in gender responses to advertising. Journal of Promotion Management, 25(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2018.1427652

- Parker, C., Scott, S., Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball sampling, In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. A. Williams (Eds.), Sage research methods foundations. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710

- Pascual-Miguel, F. J., Agudo-Peregrina, Á. F., & Chaparro-Peláez, J. (2015). Influences of gender and product type on online purchasing. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1550–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.050

- Peck, D. W. (2020). The role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on student choice: An evaluation of key motivators and moderating factors when applying to university. University of Southampton.

- Pligt, J. V. D., & De Vries, N. K. (1998). Expectancy-value models of health behaviour: The role of salience and anticipated affect. Psychology & Health, 13(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449808406752

- Presidential Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia on the Establishment of the State Islamic Institute, Pub. L. No. 11 (1960).

- Price, I., Matzdorf, F., Smith, L., & Agahi, H. (2003). The impact of facilities on student choice of university. Facilities, 21(10), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/02632770310493580

- Rai, N., & Thapa, B. (2015). A study on purposive sampling method in research (pp. 5). Kathmandu School of Law. https://www.academia.edu/download/48403395/A_Study_on_Purposive_Sampling_Method_in_Research.pdf

- Regulation of the Minister of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia Number 15 (2014).

- Rusandry, R., & Samsuddin, A. (2023). Analysis of factors affecting student decisions in selecting Sharia Economics Study Program at The Faculty of Islamic Religion Muhammadiyah University Yogyakarta. Integration: Journal of Social Sciences and Culture, 1(1), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.38142/ijssc.v1i1.49

- Safitri, L., Manshur, F. M., & Thoyyar, H. (2022). Nurcholish Madjid on Indonesian Islamic education: A Hermeneutical Study. Jurnal Ilmiah Islam Futura, 22(2), 244–259.https://doi.org/10.22373/jiif.v22i2.5749

- Shah, M., Sid Nair, C., & Bennett, L. (2013). Factors influencing student choice to study at private higher education institutions. Quality Assurance in Education, 21(4), 402–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-04-2012-0019

- Shao, C. Y., Baker, J. A., & Wagner, J. (2004). The effects of appropriateness of service contact personnel dress on customer expectations of service quality and purchase intention. Journal of Business Research, 57(10), 1164–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00326-0

- Sholehuddin, M. S., Huda, M. N., & Mucharomah, M. (2020). The Response of the participation rate to public Islamic Universities: Empirical evidence from Central Java, Indonesia. Edukasia Islamika, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.28918/jei.v5i2.2445

- Sidin, S. M., Hussin, S. R., & Tan, H. S. (2003). An exploratory study of factors influencing the college choice decision of undergraduate students in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Management Review, 8(3), 259–280. https://www.academia.edu/download/43237614/QA_sample.pdf

- Simões, C., & Soares, A. M. (2010). Applying to higher education: Information sources and choice factors. Studies in Higher Education, 35(4), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903096490

- Sonita, E., Miswardi, M., & Nasfi, N. (2021). The role of Islamic higher education in improving sustainable economic development through Islamic entrepreneurial university. International Journal of Social and Management Studies, 2(2), 42–55.

- Sreen, N., Purbey, S., & Sadarangani, P. (2018). Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.12.002

- Stoll, G., Rieger, S., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., & Rounds, J. (2021). Stability and change in vocational interests after graduation from high school: A six-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 1091–1116. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000359

- Suharto, T., & Khuriyah, K. (2016). The scientific viewpoint in State Islamic University in Indonesia. Jurnal Pendidikan Islam, 1(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.15575/jpi.v1i1.613

- Sultan, K., Akram, S., Abdulhaliq, S., Jamal, D., & Saleem, R. (2019). A strategic approach to the consumer perception of brand on the basis of brand awareness and brand loyalty. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478), 8(3), 33–44.

- Suyadi, Nuryana, Z., Sutrisno, & Baidi, (2022). Academic reform and sustainability of Islamic higher education in Indonesia. International Journal of Educational Development, 89, 102534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102534

- Syah, M. N. S. (2015). English education for Islamic university in Indonesia: Status and challenge. QIJIS (Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies), 3(2), 168–191.

- Vaikunthavasan, S., Jebarajakirthy, C., & Shankar, A. (2019). How to make higher education institutions innovative: An application of market orientation practices. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 31(3), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2018.1526741

- Van Der Pligt, J., & De Vries, N. K. (1998). Belief importance in expectancy‐value models of attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1339–1354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01680.x

- Watanabe, E. A. D. M., Alfinito, S., Curvelo, I. C. G., & Hamza, K. M. (2020). Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. British Food Journal, 122(4), 1070–1184. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2019-0363

- Welch, A. (2012). Seek knowledge throughout the world? Mobility in Islamic higher education. Research in Comparative and International Education, 7(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2012.7.1.70

- Wiese, M., Van Heerden, N., Jordaan, Y., & North, E. (2009). A marketing perspective on choice factors considered by South African first-year students in selecting a higher education institution. Southern African Business Review, 13(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC92885

- Xue, J., Zhou, Z., Zhang, L., & Majeed, S. (2020). Do brand competence and warmth always influence purchase intention? The moderating role of gender. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00248