?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In South Africa, high unemployment rates persist, particularly among the country's youth and rural residents, exacerbating socio-economic challenges such as food insecurity and poverty. Despite government initiatives aimed at promoting entrepreneurship to combat youth joblessness, participation in agriculture remains low due to negative perceptions regarding the field's status and potential earnings. This study examines the socio-economic impact of youth involvement in agriculture, with a focus on job creation and poverty alleviation in the Umzimvubu Local Municipality, Eastern Cape Province. Data was collected from 210 youth using a stratified random sampling method, and analysis was conducted using logit regression and propensity score matching techniques. The results indicate that youth engage in agriculture to enhance employment opportunities and household food security, making significant contributions to farm income and poverty reduction. Recommendations include government interventions such as mentorship programs and skills training to support youth in agricultural enterprises. These findings highlight the pressing need for targeted strategies to address youth poverty and vulnerability in South Africa.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing acknowledgment of the pivotal role of youth engagement in agriculture for employment generation and poverty alleviation within the global discourse on sustainable development. The youth cohort, renowned for its vigor and adaptability, significantly influences agricultural development and its socio-economic impact. Various studies underscore the persistent challenges of youth poverty and emphasize the need to harness their potential while addressing socioeconomic issues (Bello et al., Citation2021; Henning et al., Citation2022; Mthi et al., Citation2021; Thibane et al., Citation2023; Chipfupa & Tagwi, Citation2021; Elias et al., Citation2018). In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where poverty affects over 30% of the population and around 60% of those under 35 face unemployment and poverty, mainly in rural areas abundant in agricultural opportunities, the lack of government support and suboptimal agricultural production deter youth from pursuing agricultural careers (Smith, Citation2013). Recognizing the multi-faceted socio-economic implications of youth involvement in agriculture becomes imperative, especially with the growing global youth population (World Bank, Citation2016). Agriculture emerges as a pivotal driver of economic growth and youth empowerment in developing regions like SSA (Mthi et al., Citation2021). However, despite its potential, agriculture fails to attract many young individuals (Babbie, Citation2016). This study aims to analyze this issue's intricacies, synthesizing insights to enhance youth engagement in agriculture, and considering its crucial role in Africa's development trajectory.

The agricultural sector is pivotal to the global economy and crucial for employment, food security, and overall economic growth. Particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), it serves as a cornerstone of development, employing a significant portion of the population and sustaining livelihoods (Mujuru et al., Citation2022; Ouko et al., Citation2022; World Bank, 2020). Globally, agriculture contributed approximately 4% to the GDP in 2020, highlighting its enduring significance, especially in low-income countries (World Bank, 2020). In Africa, the sector employs over 60% of the population and makes substantial GDP contributions (African Development Bank, Citation2023). Despite challenges such as SSA's status as a net food importer, the sector demonstrates resilience, with sustained growth and increased productivity (Ouko et al., Citation2022). However, population growth forecasts suggest a surge in food imports, emphasizing the sector's critical role in addressing challenges like unemployment and poverty (Owings, Citation2020). Positive agricultural production trends in countries like Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Kenya underscore agriculture's pivotal role in driving Africa's economic progress (African Development Bank, Citation2023).

Agriculture, often underestimated for its employment potential, emerges as a vital force in youth empowerment and economic progress. Offering avenues from traditional farming to modern agribusiness, it fosters skill development and income generation. Youth engagement not only creates jobs within the agricultural value chain but also in associated sectors like agro-processing and technology-driven innovations. Particularly crucial in countries like South Africa, where agriculture is a primary livelihood amid high unemployment rates (Mthi et al., Citation2021; Thibane et al., Citation2023), youth involvement can enhance productivity, food security, and rural development (Jayne et al., Citation2018; Bello et al., Citation2021). However, obstacles hinder the full realization of these benefits, emphasizing the need to overcome barriers to youth participation. With escalating global challenges like climate change and population growth, the demand for skilled youth in agriculture becomes urgent.

Youth poverty pose a pervasive global challenge, influenced by factors like limited access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. Transitioning from adolescence to adulthood exposes individuals to increased economic vulnerability, compounded by intergenerational poverty cycles (World Bank, 2020; ILO, Citation2020). Agricultural engagement emerges as a potential avenue to break this cycle, offering viable employment options for youth (FAO, Citation2015). However, understanding the socio-economic impact necessitates nuanced analysis, considering factors like resource access and socio-cultural contexts. South African youth face obstacles such as limited access to land, financial resources, and markets (Geza et al., Citation2021; Mthi et al., Citation2021). Addressing poverty through agriculture requires holistic approaches, viewing it as a dynamic sector fostering innovation and entrepreneurship (IFAD, Citation2015). Integration of youth-friendly policies can unleash agriculture's transformative potential, facilitating sustained poverty reduction.

Empirical studies have examined youth participation in agriculture, revealing persistent knowledge gaps regarding its socio-economic impact (Fawole & Ozkan, Citation2019; Muthomi, Citation2017). Factors like attitude and resource access influence youth engagement in farming (Magagula & Tsvakirai, Citation2020; Prosper et al., Citation2015; Onyiriuba et al., Citation2020). Challenges include inherent uncertainties in agriculture and difficulties in measuring socio-economic impact accurately (Mthi et al., Citation2021). Addressing these requires supportive policies, infrastructure, and capacity-building initiatives (Mthi et al., Citation2021). Collaboration between policymakers and stakeholders is crucial for designing policies that promote technological integration and resource access (Mthi et al., Citation2021). Capacity-building programs are vital to equip youth with the necessary skills (Mthi et al., Citation2021). This study's implications extend to broader challenges in South Africa, emphasizing agriculture's potential for economic development and social empowerment among vulnerable youth (Mthi et al., Citation2021). Redefining perceptions and implementing targeted interventions can foster youth entrepreneurship, contributing to sustainable development and poverty reduction (Mthi et al., Citation2021).

Despite the acknowledged importance of youth engagement in agricultural enterprise initiatives, particularly in developing nations like South Africa, there remains a significant dearth of understanding regarding their impact, both nationally and regionally. Notably, there's a scarcity of evidence supporting discussions on the challenges of youth agripreneurship programs for local and regional policymaking. While some country-specific evaluations exist, they predominantly focus on technical skills, neglecting the integration of soft skills crucial for youth empowerment (UNDP, 2021). This lack of practical evidence presents a hurdle for informed decision-making by policymakers and development partners regarding program scalability and effectiveness (IFAD, Citation2016). Addressing these gaps is vital for promoting sustainable agricultural practices that uplift youth and contribute to poverty reduction, particularly in South Africa (IFAD, Citation2016). Therefore, this study aims to fill some of these research gaps by empirically assessing the socio-economic impact of agricultural enterprise on employment creation and poverty alleviation among young individuals in Umzimvubu Local Municipality, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa.

Materials and methods

Description of the study

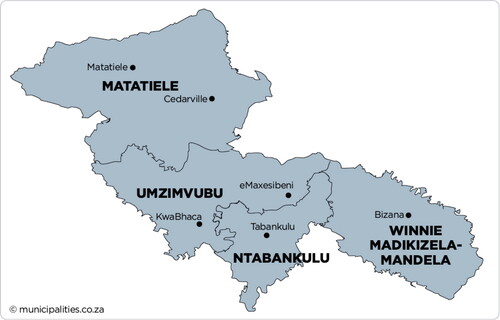

The study was conducted in Umzimvubu Local Municipality, located in the Alfred Ndzo District of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. below illustrates the study sites for this study. Umzimvubu is a Category B municipality situated in the north-western part of the province, covering an area of 2,579 km2 (Eastern Cape Socio-Economic Consultative Council (Eastern Cape Socio-Economic Consultative Council (ECSECC), Citation2017). The municipality is located at a latitude of −30.776751 to 30° 46′ 36.3036″ N and longitude of 29.02433 29° 1′ 27.588″ E. The municipality comprises diverse landscapes, including rural areas, small towns, and agricultural regions. Its population is predominantly young, with 42.8% under the age of 14, 57.4% potentially economically active (aged 15–65), and 7.8% elderly (65+). Traditional low-density settlements occupy most of the land, with migration toward urban centers over the years due to proximity to transport routes. The high proportion of dependent children places strain on the working-age population and government social assistance services. Approximately 4% of the population experiences some form of disability, primarily physical. The municipality's main economic sectors include government services (42.6%), trade (17.7%), finance and business services (13.9%), manufacturing (12.2%), transport and communication (8.7%), construction (2.2%), and agriculture (2.1%).

Figure 1. Map of Umzimvubu Local Municipality. Source: Umzimvubu Local Municipality (IDP, 2014/2015).

Umzimvubu is situated in a subtropical climate zone, experiencing warm summers and cool winters. Winter temperatures typically range from 7 to 100C, while summer temperatures range from 18 to 250C (Umzimvubu Local Municipality, 2023/2024). The predominant soils are red-yellow apedal freely drained soils, known for their high iron and mineral content, making them ideal for cropping. However, these soils are prone to significant erosion, often resulting in a thin topsoil layer. Umzimvubu Local Municipality boasts expansive agricultural land, with a significant focus on livestock farming and crop cultivation. Favorable rainfall, soil quality, and water resources contribute to its suitability for agricultural production. While three-quarters of the land consists of unimproved grassland, about 44% is degraded. Climatic conditions are conducive to agriculture, with approximately 12% of the land under cultivation, mainly for semi-commercial or subsistence farming. The predominantly rural population faces socio-economic challenges such as high unemployment and poverty rates.

Agriculture is pivotal to the local economy, providing livelihoods through livestock farming (including cattle, sheep, and goats), and crop farming (maize, potatoes, cabbage, and spinach) at a subsistence level (Giwu, Citation2024; Umzimvubu Local Municipality, 2023/2024) thus ensuring food security and income generation. Despite its agricultural potential, Umzimvubu Local Municipality encounters developmental hurdles, including limited access to essential services like education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, restricted market access, and insufficient support for small-scale farmers hinder the municipality's full agricultural potential. In essence, Umzimvubu Local Municipality possesses significant agricultural resources and potential, yet requires targeted interventions and support to overcome socio-economic challenges and foster sustainable development, ultimately improving the well-being of its residents.

Sampling procedure and sample size

The sampling methodology adopted in this study aimed to ensure a comprehensive and representative sample of young individuals within the Umzimvubu Local Municipality (ULM). ULM was chosen as the study site due to its significant population of actively engaged youths in agricultural enterprises, who rely on these ventures for their livelihoods (Umzimvubu Local Municipality, 2023/2024). The study focused on individuals aged 18 to 35 years to center on the youth demographic, encompassing both males and females to ensure gender inclusivity. A stratified random sampling approach was utilized to select a sample that accurately reflected the population under study. This technique was employed to investigate existing disparities in sustainable livelihood resources between youth involved and those not involved in agricultural enterprises and associated activities, facilitating the development of targeted intervention strategies. By discerning these differences, the study aimed to gain deeper insights into the distinct needs and challenges encountered by each group of young individuals. Stratified sampling enabled the capture of the diverse profiles of youth within the municipality, specifically those engaged in agricultural pursuits and those not. The initial step in stratified sampling involved dividing the population into strata based on the backgrounds of young individuals involved in agricultural enterprises, categorizing them into crop and vegetable farming, livestock farming, and mixed farming. Subsequently, random sampling techniques were applied within each stratum to ensure an equitable representation of respondents. The criteria used to select respondents: first the youth should be participating in agricultural enterprise, Secondly the farm must be functional and active and Lastly, the farm has to be linked with job creation and poverty alleviation in the Umzimvubu Local Municipality. This process entailed the random selection of individuals from both the participating (150) and non-participating youth groups (60). The study had to select 210 as a sample size due to time constraints and financial reasons which did not allow the researchers to cover a larger sample size in the municipality. Cochran's (Citation1977) proportionate-to-size sampling methodology was utilized to ascertain the appropriate sample size necessary for the study.

Where n=required sample size; Z=confidence level at 95% (standard value of 1.96), p=estimate of youth involved in agricultural enterprises which is at 0.89. This was an assumption that 89% of youth participate in agricultural enterprises in the study area; q = This is the weighting variable given by 1 − p; e2= Margin of error at 5% (standard value of 0.05). The unadjusted sample size of the study was 150 youth participating in agricultural enterprises. The sampled youth were selected through the farmers' listings and stakeholder consultation at the community level to reduce the sample. For non-participants, 60 individuals were randomly selected from the study area based on their availability during data collection.

Data collection

Primary data were collected for this study through an intensive survey, gathering cross-sectional data from 210 (participants and non-participants) youths in the study area. Face-to-face interviews were conducted using self-administered structured questionnaires as the primary method of data collection. To ensure the reliability and efficiency of the questionnaires, a pre-testing phase was conducted in Kokstad, a location separate from the study sites. This pre-testing served the dual purpose of assessing questionnaire reliability and allowing researchers to train enumerators, familiarizing them with the questionnaire format. The data collected from the youth encompassed four main sections: The questionnaire utilized in this research incorporates several scales to assess various aspects related to youth involvement in agricultural enterprises, job creation, and poverty alleviation. Firstly, Section A captured demographic profiles of youth, Section B, focused on measuring the level of youth participation in agricultural activities, which includes items assessing their engagement in farming, livestock rearing, or agribusiness ventures. Thirdly, focused on utilizing a scale to measure the impact of agricultural involvement on job creation, encompassing questions that explore the number of jobs created directly or indirectly through agricultural enterprises managed by youth. Lastly, the study incorporates a scale to evaluate the contribution of youth engagement in agriculture to poverty alleviation, encompassing items that probe into changes in household income, access to necessities, and overall economic well-being resulting from youth-led agricultural initiatives. These scales are designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the implications of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises for both economic development and poverty reduction. Additionally, secondary data sources were utilized, including information from the government gazette in Umzimvubu Local Municipality, peer-reviewed publications, and farmer support groups.

Ethical approval

All ethical considerations for the study were approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Human and Social Science Research Committee (HSSREC) with a Protocol Reference Number of HSSREC/00005088/2022. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The questionnaires were anonymized, and respondents were free to opt out of participation whenever they were uncomfortable.

Data analysis

The collected data were coded and entered into an Excel spreadsheet before being transferred to SPSS version 26 and STATA 17 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including percentages, frequencies, tables, and means, were utilized to assess the demographic profile of farmers and the various types of agricultural enterprises in which youth are involved. Logit regression was employed to estimate the knowledge of factors influencing youth participation in agricultural enterprises. Additionally, propensity score matching was utilized to evaluate the socio-economic impact of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises.

Binary logit regression

The study utilized binary logistic regression to estimate youth participation in agricultural enterprises. Logistic regression is an appropriate statistical method when the dependent variable is binary, as is the case with youth involvement in smallholder farming (Yes or No). Studies by Cheteni (Citation2016), Mdoda et al. (Citation2019), Thibane et al. (Citation2023), Sigigaba et al. (Citation2021), Mdoda (Citation2020), and Nnadi and Akwiwu (Citation2008) have highlighted the widespread use of logistic regression analysis in identifying factors influencing youth engagement in agricultural enterprises. This methodology enables researchers to model the probability of a binary outcome and assess the impact of various factors on the likelihood of youth participation in smallholder farming activities. Binary logistic regression is the appropriate analysis method when the dependent variable is dichotomous (binary), making it suitable for analyzing youth participation in agricultural enterprises (Yes or No) as the dependent variable in this case.

Binary logistic regression is a statistical method utilized for modeling the probability of a binary outcome, where the dependent variable consists of two categories, typically coded as 0 and 1. This method finds applications across various fields, including epidemiology, economics, psychology, and machine learning. According to Joshi et al., binary logistic regression is advantageous due to its ability to handle dichotomous outcome variables, resulting in more straightforward and flexible results that are easier to interpret. The choice of this model was motivated by the presence of two categories in the dependent variable. Akrong and Kotu (Citation2022) have noted that binary logistic regression is particularly suitable for studies involving dichotomous outcome variables due to its mathematical convenience. It effectively addresses the issue of heteroscedasticity and conforms to the assumptions of the normal probability distribution. The decision to use the logit model was based on its ability to provide answers to the primary research questions, considering the characteristics of the data and sample. Additionally, it was observed that the significant descriptive variables did not exert the same level of influence on the agricultural enterprise decisions of youth. The model was specified as follows:

Where

= 1 if youth participating in agricultural enterprises or 0 if otherwise, ei is the error term,

are parameter estimates (coefficients) and

are independent variables.

Analytic framework

Propensity score matching (PSM) was employed to assess the impact of youth participation in agricultural enterprises. PSM is a statistical technique utilized in observational studies to estimate the causal effect of a treatment, policy, or intervention. Its objective is to create a comparison group that closely resembles the treated group in terms of observed characteristics, thereby minimizing selection bias. PSM achieves this by matching two groups of individuals: those who participated in the event (treated group) and those who did not (control group) but have similar propensity scores, as outlined by Rubin. The process involves assigning a propensity score to each individual, indicating their likelihood of receiving the treatment based on observed covariates, often estimated through logistic regression. Subsequently, subjects with similar or identical propensity scores are matched, resulting in a more balanced and comparable comparison group. This method, as highlighted by Lobut, Ouya et al., Mdoda et al. (Citation2019), and Wang et al. (Citation2021), offers the advantage of identifying which variables influence the likelihood of participation in a specific event, distinguishing it from other techniques. In this study, PSM will be utilized to evaluate the effects of youth engagement in agriculture on income and poverty, thereby mitigating self-selection bias. Widely employed across disciplines such as economics, public health, and social sciences, propensity score matching serves to address confounding variables and enhance the validity of causal inference in observational studies.

This approach involves matching two groups of youths: those engaged in agricultural activities and those who are not. This method encompasses six key steps: variable selection, propensity score calculation, matching method selection, match creation, match quality evaluation, and intervention effect estimation. In the initial step, the variables selected are independent variables known to influence both participation and livelihood outcomes, as evidenced in prior research on related treatments and measured outcomes (Pan & Bai, Citation2015). Following variable selection, propensity scores are computed using the logistic regression model, which is widely preferred over other techniques like discriminant analysis and Mahalanobis distance (Austin, Citation2011; Mdoda et al., Citation2019). The rationale for choosing the logistic regression model lies in its effectiveness in describing data and elucidating relationships between variables. This model incorporates a dependent variable (Willingness to participate) with two potential outcomes: a value of 1 denotes participation (treatment), while 0 signifies non-participation (control), based on the selected independent variables from the first step. The model is statistically expressed as EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) .

(1)

(1)

Where (Xi) is a youth, (Ti) is a dependent variable (participating in agriculture) equals 1 if the youth is participating in agriculture and 0 otherwise, 𝛽0, 𝛽1 and 𝛽2 are coefficients of the observed youth's income and poverty respectively and 𝜀i is the error term.

After computing the propensity scores, the next step involves matching the two groups based on these scores (Stuart, Citation2019). Before proceeding with the matching process, the appropriate method for pairing youths engaged in agricultural activities with those who are not will be selected. Among the five available matching methods, Nearest-neighbor matching (NN) with replacement will be utilized, allowing a single treatment unit to be matched to multiple units in the control group. This method minimizes the propensity score distance between the treatment unit and the nearest units in the control group, thus mitigating bias (Dehejia & Sadek, Citation2002). Following the completion of matching, the subsequent step entails evaluating the quality of the match to ensure that the control group exhibits a propensity score distribution similar to that of the treatment group. To assess match quality, Rubin's B and Rubin's R will be employed. Rubin's B indicates the standardized difference of the means of the propensity score in the unmatched and matched groups, with a value ideally lower than 0.25. Conversely, Rubin's R represents the ratio of the treated to control variances of the propensity scores, ideally falling between 0.5 and 2 (Rubin, Citation2001). Once the match quality is balanced, the estimation of outcomes will proceed using the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), which is statistically expressed as:

(2)

(2)

Where ATT is the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated, Yi is the mean outcome of a target variable, e.g., output, and T is a dummy variable, T = 1 for participants (participate in agriculture) and T = 0 otherwise. Equation (3) shows that the average outcomes on non-participating youths who are like participating individuals based on similar propensity scores, p(X), are a substitute for the counterfactual mean.

Validated statement

To ensure the validity of the study's research findings, the research study employed a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, triangulating data from surveys, interviews, and focus group discussions. Additionally, the research utilized established scales and measures to assess variables such as youth involvement in agricultural enterprises, job creation, and poverty alleviation, thereby ensuring the reliability and accuracy of our results.

Reliability statement

To enhance the reliability of our study, the study employed rigorous data collection procedures and techniques, including standardized survey instruments, trained interviewers, and systematic coding and analysis methods. Furthermore, the research study conducted a pilot study to refine the research instruments and procedures, and the study maintained consistency in the data collection and analysis processes throughout the study period. These efforts were aimed at minimizing bias and errors, thereby ensuring the reliability of our findings regarding the implications of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises for job creation and poverty alleviation.

Results and discussion

Socioeconomic characteristics of young people in agricultural enterprises

The study involved a sample of 210 youths engaged in agricultural enterprises within the study area. Results indicated that approximately 64% of the sampled youths were involved in agricultural enterprises. displays the socio-economic characteristics of both youth participants and non-participants in agricultural enterprises.

Table 1. Socio-economic characteristics of youth participants and non-participants.

The findings indicate that the majority of young individuals engaged in agricultural enterprises in ULM have an average age of 27 years. This trend suggests that this age group is particularly active and likely to pursue agriculture as a means of employment and income generation. These findings are consistent with those reported by Douglas et al. (Citation2017). Furthermore, the results reveal that 63% of the sampled youth were males, with 68% of them involved in agricultural enterprises, compared to 58% of non-youth participants in agricultural enterprises. This aligns with the observations of Thibane et al. (Citation2023) and Cheteni (Citation2016), indicating a male dominance in youth participation in agriculture, while females tend to prefer non-agricultural activities. On average, the youth in the study area had completed 11 years of schooling, equivalent to secondary education. This level of education suggests that youth possess the necessary knowledge and literacy skills, which likely influenced their decision to engage in agricultural enterprises. Additionally, the average household size was seven people per household, indicating significant familial support for those involved in agricultural activities, often utilizing family members as laborers. This reliance on family labor is crucial, particularly considering the challenges youth face in accessing credit for hiring external labor. The high unemployment rate in the study area, reported at 52%, underscores the pressing challenges faced by South African youth, where overall youth unemployment exceeds 40%. These findings highlight the pivotal role of agricultural enterprises as a primary solution for youth employment and income generation, crucial for sustaining both themselves and their families.

In the study area, youth had access to land for practicing agricultural enterprises, with an average of 3 hectares available per individual. This land availability was notable, particularly because the majority of youth were engaged in crop and vegetable enterprises, leveraging the suitability of the land for farming purposes. Furthermore, youth involved in agricultural enterprises demonstrated considerable farming experience, averaging 11 years, which not only generated income but also created job opportunities. Access to extension services played a crucial role in equipping youth with current agricultural information and facilitating access to markets, consistent with findings reported by Mdoda et al. (Citation2022) and Thibane et al. (Citation2023). However, a significant limitation was the lack of access to credit among youth participants, restricting their ability to adopt modern agricultural techniques and hire workers to assist in farm operations. Despite this, youth had access to land due to family and customary laws, where land was inherited from their forefathers. For many youths involved in agricultural enterprises, farming served as their primary source of employment, as they were self-employed and relied on agricultural activities for their livelihoods.

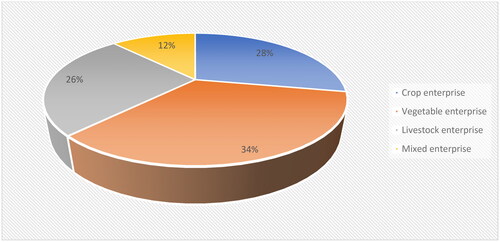

Types of agricultural enterprises youth engaged on

Given the high unemployment rate in South Africa, participation in agricultural enterprises emerges as the primary solution for young people. Youth engaged in various agricultural activities based on their decisions and interests. depicts the types of agricultural enterprises in which youth were involved in the study area. Notably, vegetable enterprises emerged as the most common agricultural activity among youth in ULM. These findings align with those of Tarekegn et al. (Citation2022). This preference can be attributed to the fact that many youths were raised practicing vegetable farming, thus possessing experience in this domain, and it is considered less demanding compared to other enterprises. Crop enterprises followed closely at 28%, with livestock and mixed enterprises representing 26 and 12%, respectively. These agricultural activities play a vital role in generating income and providing food both for households and markets.

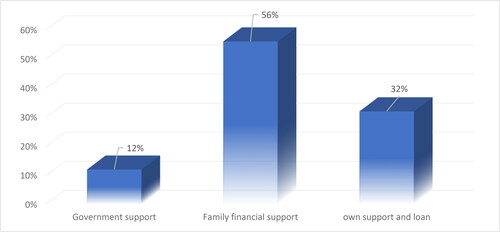

Sources of funding for youth participation in agricultural enterprises

This aspect is crucial for smooth farm operations and is essential for anyone involved in farming. In this study, it is evident that the youth engaged in agricultural enterprises relied primarily on family financial support (56%), alongside their capital and loans (34%), to fund their agricultural ventures. However, this reliance had long-term implications for the youth, as financial injections from family sources were sometimes inadequate or delayed, constraining their ability to run farm operations efficiently and invest in modern agricultural techniques to enhance productivity. Government support, albeit available, was minimal, as illustrated in below. The lack of access to adequate financial support had a detrimental impact on farms, particularly in the adoption of modern techniques and the ability to hire additional workers.

Factors influencing the participation of youth in agricultural enterprises

The study employed binary logistic regression to identify factors influencing youth participation in agricultural enterprises. Before conducting the economic estimation, various econometric assumptions were examined using appropriate methodologies. Initially, the presence of significant multicollinearity among the independent variables was assessed. The model outcomes revealed no significant multicollinearity among the variables, with a mean Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of 1.24, all below two for each independent variable. Furthermore, to address heteroscedasticity issues within the explanatory variables, robust standard error calculation for the logit model was utilized instead of the Breusch–Pagan test (hettest). The results, as presented in , indicate that eight variables had a significant influence on youth participation in agricultural enterprises at various probability levels. The significant variables are elaborated in , with the adjusted R2 of the regression being 0.72.

Table 2. Factors influencing youth participation in agricultural enterprises.

This adjusted R2 value implies that 72% of the variation in the dependent variables can be explained by the regressors in the model. A higher R2 value suggests a more explanatory model, indicating a better fit to the sample. The results of the logit regression demonstrate that the log-likelihood ratio (LR, chi2) is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the independent variables included in the logit model jointly explain the likelihood of youth participation in agricultural enterprises. provides insights into the specific factors that play a role in influencing youth participation in agricultural enterprises in the ULM.

The logit regression analysis unveils significant socio-economic factors influencing the participation of young people in agriculture. Age emerges as a positive factor for youth engagement in agricultural enterprises, as evidenced by its positive coefficient, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that with each additional year of age, there is an associated increase in youth participation in agricultural endeavors. Young individuals possess the potential to surmount major constraints to agricultural production expansion in the country, owing to their receptiveness to innovative ideas and practices compared to older farmers. These findings are consistent with Barau, who suggests that young people have an edge over elderly farmers due to their propensity to swiftly learn and embrace innovative farming technologies, thereby enhancing productivity and bolstering food security. However, these results contradict the findings of Akrong and Kotu (Citation2022) and Fasakin et al. (Citation2022), who argued that as youth age, they tend to gravitate towards non-agricultural activities.

Gender plays a significant role in agricultural participation, as evidenced by its positive coefficient, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. This observation underscores a gender imbalance within agricultural enterprises, suggesting that males are more inclined to engage in agribusiness compared to females. The positive correlation between gender and agricultural enterprises implies that agriculture, or agribusiness, is predominantly associated with men, historically perceived as a male-dominated domain. This gender disparity hints at the presence of gender-related challenges or biases within the agricultural sector, potentially influencing women's participation in agricultural activities. Specifically, a 1% increase in males in the study area is associated with a greater likelihood of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises compared to females. This inclination may stem from the physically demanding nature of agriculture-related tasks. These findings align with those of Akrong and Kotu (Citation2022), who similarly noted male dominance in agricultural enterprises, particularly among young farmers. This gender discrepancy could be attributed to the challenges women face in accessing essential resources, including limited availability of information, advisory services, training opportunities, and productive resources such as land and agricultural technologies. Addressing these disparities in resource access could potentially contribute to narrowing the gender gap in agricultural enterprises, thereby fostering greater inclusivity and equity within the sector.

Years spent in school exhibited a positive coefficient and was statistically significant at a 5% level, underscoring its importance in agricultural enterprises. This implies that each additional year spent in school contributes to increased youth participation in agricultural endeavors. Education plays a pivotal role in shaping youths' understanding of agricultural practices and equips them with essential skills for farm operations. As young individuals spend more years in school, they gain valuable knowledge and exposure to various farming techniques through training activities. This exposure enhances their proficiency in managing farm operations and fosters the adoption of innovative technologies, ultimately contributing to improved agricultural productivity. Young farmers are thus better positioned to leverage modern agricultural methods compared to their older counterparts. These findings corroborate those of Thibane et al. (Citation2023), affirming the positive relationship between education and youth engagement in agricultural enterprises. However, they diverge from the findings of Akrong and Kotu (Citation2022), who suggested that education might impede youth participation in agricultural activities.

The study unveils a positive correlation between household size and engagement in agricultural enterprises. Household size exhibited a positive coefficient and was statistically significant at a 5% level, indicating that an increase in household size by one person corresponds to a higher likelihood of youth opting for agribusiness over other ventures. This discovery resonates with the findings of Mdoda and Obi (Citation2019), suggesting that larger households may stimulate heightened agricultural production to meet food security demands. Moreover, the results underscore a favorable association between youth and their inclination toward participating in agribusiness activities. These findings contradict those of Jayasinghe and Niranjala (Citation2021), who reported a negative impact of household size on youth involvement in agricultural enterprises.

Extension services exhibit a positive coefficient and are statistically significant at a 5% level, indicating that a 1% increase in access to extension and advisory services correlates with heightened youth participation in agricultural enterprises. Access to extension services typically involves the dissemination of information that fosters youth engagement in agribusiness. The positive coefficient underscores the role of extension services in encouraging youth involvement in agricultural enterprises. This finding resonates with the research conducted by Tarekegn et al. (Citation2022), which demonstrated that extension services positively influence the likelihood of youth engaging in agribusiness activities in Vietnam and Zambia.

Land access exhibits a positive coefficient and is statistically significant at a 5% level, indicating that a 1% increase in land access for youth leads to a corresponding increase in their participation in agricultural enterprises. Youth often encounter challenges in accessing land, whether through government initiatives such as land reform programs or customary laws. However, obtaining land through inheritance has proven effective for many youth, enabling them to engage in agricultural enterprises to generate income and enhance food security. The majority of youth obtain land through inheritance or leasing arrangements with family members. These findings align with previous studies by Fasakin et al. (Citation2022) and Kosec et al. (Citation2018).

The study reveals that access to credit exhibits a negative coefficient, statistically significant at a 5% level. This suggests that a 1% increase in access to credit results in a decrease in youth participation in agricultural enterprises. This finding implies that young individuals may encounter difficulties in securing the necessary credit for acquiring inputs essential for enhancing agricultural productivity, possibly due to limited accessibility or aversion to financial risk. The results underscore the significant and adverse effect of insufficient access to credit on youth's decisions to engage in agricultural enterprises. This lack of access could be attributed to inadequate support from credit institutions, creating a discouraging environment for youth involvement in agriculture. These results are consistent with prior research by Thibane et al. (Citation2023) and Fasakin et al. (Citation2022), which suggested that a dearth of financial support and access acts as a deterrent for youth and smallholder farmers in entering agricultural enterprises.

Membership in farm organizations exhibits a positive coefficient, statistically significant at a 5% level, signifying its crucial role and positive contribution. This suggests that a 1% increase in farm organization membership induces a corresponding increase in youth participation in agricultural enterprises. Being part of a farm organization is beneficial as it provides youths with training opportunities that enhance their knowledge and equip them with information on current farming techniques and market access strategies, which are essential for agricultural success. Moreover, membership in such organizations fosters a sense of connectedness and trust among youths, contributing to positive mindset and attitudinal changes. The presence of peers engaged in agriculture within these organizations can influence youths' decisions to participate in agricultural activities. These findings are consistent with those of Olarinde et al. (Citation2020), underscoring the significant role of peer influence and agricultural success in shaping individuals' decisions to engage in farming.

The effect of youth participation in agricultural enterprises

The study utilized propensity score matching (PSM) to assess the impact of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises, particularly in terms of farm returns. The PSM model was preferred over Heckman's two-stage model in the absence of selectivity bias in the dataset. Selectivity bias, typically indicated by the significance of Mills' lambda, was found to be insignificant in our investigation, with a coefficient of 180.611 and a p-value of 0.755, suggesting no selectivity bias present in the model. Consequently, the Heckman two-stage model was deemed inappropriate for our dataset. In this study, individual youths' socioeconomic statuses were leveraged to create matched observational pairs with similar characteristics. Two distinct groups were identified: youth actively participating in agricultural enterprises (treatment cases) and those not involved in such enterprises (controls). The matching process entailed pairing individuals based on their propensity scores for treatment. These scores, representing the predicted probability of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises, were derived from a logistic regression model incorporating various predictors. This approach aimed to establish balanced and comparable groups to facilitate more accurate observational analysis by controlling for potential confounding variables.

presents the outcomes from the propensity score matching model, juxtaposed with the results obtained from the action magnitude model. The propensity score, serving as a probability measure, indicates that the mean probability for youth in the treatment group was 80%. This suggests that, on average, there is an 80% likelihood that a given youth will participate in agricultural enterprises (treatment assignment), particularly concerning productivity and revenue outcomes. This probability offers insight into the likelihood of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises based on the analyzed factors.

Table 3. Effects of youth participation on agricultural enterprises.

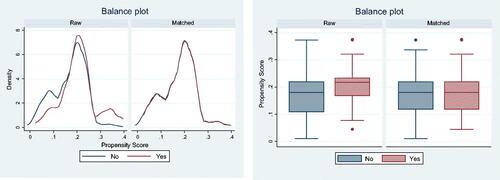

Distribution of the propensity score for the treated and the control group after five-to-one nearest-neighbour matching

demonstrates the reliability of the obtained results, showcasing a successful matching between youth who participate in agriculture and those who do not.

presents the density distribution of propensity scores for both participants and non-participants. The left box plot displays the propensity score distribution for participants, while the right box plot illustrates the distribution for non-participants. Kernel-based matching and box plots were employed for the analysis. The results from propensity score matching (PSM) indicate a positive impact of youth participation in agricultural enterprises on farm income. This suggests that engaging in agricultural activities can contribute to increasing farm income and alleviating poverty. Although non-farm income shows a positive trend, its lack of statistical significance may imply the importance of encouraging young individuals to engage in supplementary activities to bolster household income, particularly during off-seasons.

Impact of youth participation in agricultural enterprises on farm income

The influence of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises on farm income is delineated in . It demonstrates a substantial effect of youth involvement in agricultural activities on farm income

The PSM findings indicate that youth engagement in agriculture yields profitable returns in terms of income productivity. The matching conducted through Nearest Neighbor and Kernel-based methods underscores the positive impact of young people's involvement on income revenue, revealing a highly significant average treatment effect on the treated (ATT). Specifically, both algorithms demonstrate a notable increase in rice revenue attributed to intensive youth participation in agriculture, amounting to ZAR 1088.78 in the Nearest Neighbor approach and ZAR 871.88 in the Kernel-based matching method.

These results imply that active participation in agricultural enterprises can lead to a substantial enhancement in farm income by the mentioned amounts. This effect is rationalized by the positive influence of youth involvement on productivity. With an anticipated rise in yield, there is a probability of increased availability of agricultural products for sale, potentially resulting in higher farm revenue, particularly in the absence of market failures. These findings are consistent with Ng'atigwa et al. (Citation2020), who found that youth participation in agriculture increases as they witness a rise in income revenues. The matches indicate that youth involvement positively impacts their livelihoods by driving production increases that translate into higher returns. The results demonstrate that an uptick in farming production by youth not only boosts farm revenues but also, at its most effective, enhances living standards and alleviates poverty.

Implications for local and international standing

The significance of the study from a local viewpoint

Informed decision-making

The study provides local policymakers and decision-makers with empirical evidence on the socio-economic impact of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises. This evidence-based approach enables informed decision-making regarding the development and implementation of policies, programs, and initiatives aimed at promoting youth involvement in agriculture for employment creation and poverty alleviation.

Targeted Interventions: Local agricultural stakeholders, including agricultural extension officers, community leaders, and agricultural cooperatives, can use the study findings to design targeted interventions and support mechanisms tailored to the specific needs and challenges faced by youth farmers in the region. This includes providing access to resources, training, mentorship, and market linkages to enhance youth participation and productivity in agriculture.

Community empowerment:

By highlighting the positive impact of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises, the study empowers local communities to recognize and harness the potential of youth as agents of change and economic development. It encourages collaboration and partnership between youth, local organizations, and institutions to create sustainable livelihood opportunities within the agricultural sector.

Capacity building

The study findings serve as a basis for capacity-building initiatives aimed at enhancing the skills, knowledge, and entrepreneurial capabilities of local youth interested in agriculture. Training programs, workshops, and educational campaigns can be developed to equip youth with the necessary technical, business, and leadership skills to succeed in agricultural enterprises.

Poverty alleviation

By emphasizing the role of agriculture in poverty alleviation, the study underscores the importance of investing in the agricultural sector as a means to improve livelihoods and reduce poverty within the local community. It advocates for targeted interventions that prioritize marginalized groups, including rural youth, in accessing agricultural opportunities and resources.

The significance of the study from an international viewpoint

Policy insights

The findings provide valuable insights for policymakers worldwide on the role of youth participation in agriculture for employment creation and poverty alleviation. Understanding the factors influencing youth engagement and the positive effects on socio-economic outcomes can inform the development of targeted policies and programs in different countries facing similar challenges.

Best practices sharing

International audiences can benefit from learning about successful strategies and best practices identified in the study for promoting youth involvement in agricultural enterprises. These insights can be adapted and applied in diverse socio-economic contexts to maximize the impact of youth initiatives in agriculture.

Knowledge exchange

The study contributes to knowledge exchange and collaboration among international stakeholders, including governments, NGOs, international organizations, and development agencies. By sharing research findings, methodologies, and lessons learned, stakeholders can collectively advance efforts to harness the potential of youth in agriculture globally.

Cross-cultural learning

Understanding the socio-economic dynamics of youth engagement in agricultural enterprises across different regions and countries facilitates cross-cultural learning and mutual understanding. International audiences can gain perspectives on cultural, institutional, and contextual factors shaping youth participation in agriculture, leading to more contextually relevant interventions and collaborations.

In conclusion, the study not only contributes to local development efforts by offering evidence-based insights and actionable recommendations for utilizing youth engagement in agriculture as a catalyst for sustainable economic growth, employment generation, and poverty reduction within the surrounding communities but also serves as a valuable resource for international audiences interested in addressing youth unemployment, poverty, and sustainable agricultural development. It fosters cross-border dialogue, collaboration, and collective action toward achieving shared development objectives.

Conclusion and recommendations

The study aimed to evaluate the socio-economic impact of youth involvement in agricultural enterprises within the Umzimvubu Local Municipality, Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The study identifies factors such as age, access to credit, membership in farm organizations, gender, access to extension services, and land access, which influence youth engagement in agriculture, both positively and negatively. Utilizing Propensity Score Matching (PSM), it consistently found a significantly positive impact on youth involvement, correlating with improved farm revenue. Aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goals 1 and 8, the study emphasized evidence-based approaches for sustainable progress, stressing youth empowerment and inclusive agricultural development. Recommendations urge policymakers, especially in developing nations, to prioritize credit access for young farmers, promoting investment and productivity. Encouraging youth participation in farm organizations fosters networking and market access. Gender-inclusive policies address challenges faced by female youth farmers, ensuring equitable participation. Strengthening extension services provides technical assistance and training. Addressing land access barriers enables expansion, while investments in mentorship enhance skills and business acumen. Crucially, capacity-building initiatives are vital for effective management, aligned with agricultural policies and youth development strategies, fostering an enabling environment for youth innovation in agriculture.

Enhancing mentorship programs for youth in agricultural enterprises

South Africa has implemented numerous youth programs intending to engage young people in agricultural enterprises. While some initiatives have achieved success, others have faced challenges. Drawing from comprehensive study findings, it is recommended that policymakers, government agencies, and private entities prioritize support for these programs by incorporating robust mentorship components. Mentorship has proven to facilitate a seamless transition from theoretical knowledge to practical training for young individuals. By investing in mentorship programs, stakeholders can ensure that youth receive the guidance and support necessary to navigate the complexities of agricultural entrepreneurship effectively. This approach not only enhances the skills and confidence of young participants but also fosters sustainable development within the agricultural sector. These are:

Lima rural development foundation

The Lima Rural Development Foundation is dedicated to fostering dignified, sustainable, and transformative community growth, both locally in South Africa and globally. LIMA organization prioritizes the holistic advancement of individuals and livelihoods within resource-scarce environments, with a particular focus on rural regions. Through comprehensive, field-based initiatives, Lima harnesses local economic development efforts and facilitates the establishment of relevant institutions to address poverty and enhance human capacity. Central to their approach is the belief that inclusive development processes are essential for fostering enduring social change in rural communities. LIMA is committed to integrating marginalized populations not only into development projects but also into the broader economic landscape, especially young people with the necessary skills. By cultivating collaborative platforms and forging strategic partnerships across sectors, LIMA strives to empower disadvantaged communities in the long term. Additionally, Lima actively engages in evidence-based research and advocacy to shape discourse and influence public policies pertinent to rural development. With a team comprising over 100 full-time employees and 19 specialist consultants, LIMA is proud that more than 85% of their permanent staff hail from previously disadvantaged backgrounds, with over 50% being women, reflecting our commitment to diversity and equity.

The Lima Rural Development Foundation's approach, emphasizing inclusive development and economic empowerment, serves as a model for mentoring young people in agriculture. By integrating marginalized groups into the sector and fostering strategic partnerships, Lima creates opportunities for youth to engage meaningfully in sustainable agricultural practices and community development.

Ikusasa non-government profit organization (NPO)

The Ikusasa NPO is a farm school initiative that offers mentorship and training to young prospective farmers in rural South Africa, focusing on sustainable agriculture techniques and agribusiness management. Through this program, successful youth-led agricultural enterprises have been established, contributing significantly to local economic development. Ikusasa empowers schools by providing training to learners, teachers, and the wider community in poultry farming, which offers a sustainable source of funding. The project integrates farming and animal care into the Grade 4 Social Studies curriculum, providing both theoretical and practical instruction to participants in establishing and managing a poultry farm, as well as in business management, sales, and entrepreneurship. Infrastructure improvements, such as the construction of rainwater harvesting systems, ensure water sustainability for both poultry maintenance and improved school hygiene. Additionally, awareness campaigns on hygiene practices help prevent disease spread among the chickens. The initiative has also facilitated the creation of three family-operated egg production businesses, with Ikusasa providing the necessary materials and poultry. Mentoring is provided to support these small-scale enterprises. To showcase their newfound knowledge in farming and entrepreneurship, learners culminate the program with a play performed for parents, community leaders, and the school community, fostering knowledge sharing and community engagement.

The Ikusasa NPO can expand and be used as a vehicle for its impact by integrating into a broader mentorship program for youth in South Africa, through offering mentorship in sustainable agriculture, business management, and entrepreneurship. By partnering with schools and community organizations, it can reach more young people and empower them with practical skills for sustainable livelihoods.

AgriSETA skills development program: AgriSETA (Agricultural Sector Education and Training Authority)

The AgriSETA Skills Development Program is a collaborative effort between the Agricultural Sector Education and Training Authority (AgriSETA) and agricultural enterprises, aimed at offering skills training and mentorship to youth across different agricultural sub-sectors. Through this initiative, young individuals have gained enhanced employability and entrepreneurial skills in agriculture, thereby catalyzing socio-economic progress in rural regions. This program plays a crucial role in transforming the agricultural sector by nurturing high-level skills among youth, presenting significant opportunities for both individuals and the nation at large. By providing training, skills development, and capacity-building support, it lays the foundation for establishing sustainable agricultural practices and enterprises.

Incorporating the AgriSETA Skills Development Program into a mentorship program for youth engagement in agricultural enterprises in South Africa involves several strategic steps. Firstly, AgriSETA partnership needs to be established with educational institutions, community organizations, and agricultural enterprises to identify and recruit young participants interested in agriculture. Secondly, tailored mentorship and training programs should be developed, focusing on practical skills such as crop cultivation, livestock management, agribusiness planning, and financial literacy. These programs should also include mentorship components where experienced farmers and industry professionals provide guidance and support to the youth. Additionally, networking events, workshops, and field visits can be organized to facilitate knowledge exchange and exposure to different agricultural practices and technologies. Furthermore, ongoing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms should be implemented to track the progress of participants and address any challenges they may face. By integrating the AgriSETA Skills Development Program into a comprehensive mentorship initiative, young people can acquire the necessary skills, knowledge, and support to succeed in agricultural enterprises and contribute to the sector's growth and development in South Africa.

Limitations and future research directions

The study was confined solely to Umzimvubu Local Municipality in the Alfred Ndzo District Municipality of South Africa, primarily due to financial constraints and time limitations. Consequently, the results are exclusively derived from data provided by youth within this specific locality. While the study offers evidence-based insights and practical recommendations for harnessing youth participation in agriculture to drive sustainable economic growth, employment creation, and poverty alleviation within the immediate vicinity, it is crucial to recognize its limited geographical scope. To broaden the applicability and generalizability of findings, future research endeavors' should consider diverse study sites across South Africa or globally. These efforts could entail longitudinal studies to evaluate the enduring impacts of youth involvement in agriculture, qualitative research to delve into the underlying motivations and obstacles encountered by young farmers, and assessments of the efficacy of targeted interventions or policies designed to bolster youth engagement in agriculture. By expanding the scope of the investigation, researchers can deepen our comprehension of the socio-economic dynamics surrounding youth participation in agricultural enterprises and devise tailored strategies for fostering inclusive and sustainable rural development on a broader scale.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Author contributions

OG and LM were involved in the conceptualization and design of the manuscript, OG and SN in data collection and data analysis, LM in supervision and proofreading, OG, LM, and SN data curation and cleaning, and drafting of the paper. All authors agree and approve the submission of this article for publication.

Acknowledgment

We extend our gratitude to all youth from Umzimvubu Local Municipality who participated in the study and provided us with all the information needed. The author also extends his special thanks to all agricultural experts of the district for their continuous support by providing all the indispensable information, facilitating the data collection process, and providing all the vital secondary data. This research received no funding at all. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The anonymized recorded data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ongama Giwu

Ongama Giwu is a Masters' Candidate in Agricultural Economics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

Lelethu Mdoda

Lelethu Mdoda is a Senior Lecturer in Discipline of Agricultural Economics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

Samuel S. Ntlanga

Samuel Sesethu Ntlanga is a PhD Candidate in Agricultural Economics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

References

- African Development Bank. (2023). 2023 Annual Report. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/MdodaL/Downloads/afdb24-06_annual_report_en_0522_smaller.pdf

- Akrong, R., & Kotu, B. H. (2022). Economic analysis of youth participation in agripreneurship in Benin. Heliyon, 8(1), e08738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08738

- Aun, L. H. (2020). Unemployment among Malaysia's youth: Structural trends and current challenges. ISEAS Perspective, 65, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102990

- Austin, P. C. (2011). An Introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(3), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

- Babbie, K. (2016). Rethinking the ‘youth are not interested in agriculture’ narrative. Next Billion, blog. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2ASxLwn

- Bank, A. D. (2019). Chapter 2: Jobs, growth and firm dynamism. In African Economic Outlook https://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Publications/AEO_2019-EN.pdf (accessed 17 January 2020).

- Bello, L. O., Baiyegunhi, L. J. S., Mignouna, D., Adeoti, R., Dontsop-Nguezet, P. M., Abdoulaye, T., Manyong, V., Bamba, Z., & Awotide, B. A. (2021). Impact of youth-in-agribusiness program on employment creation in Nigeria. Sustainability, 13(14), 7801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147801

- Cheteni, P. (2016). Youth participation in agriculture in the Nkonkobe district municipality, South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology, 55(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2016.11907025

- Chipfupa, U., & Tagwi, A. (2021). Youth’s participation in agriculture: A fallacy or achievable possibility? Evidence from rural South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), a4004. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v24i1.4004

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Dehejia, R. H., & Sadek, W. (2002). Propensity score matching methods for non-experimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465302317331982

- Douglas, K., Singh, A. S., & Zvenyika, K. R. (2017). Perceptions of Swaziland’s youth towards farming: A case of Manzini region. Forestry Research and Engineering: International Journal, 1(3), 14.

- Eastern Cape Socio-Economic Consultative Council (ECSECC). (2017). Umzimvubu local municipality socio-economic review and outlook. Retrieved September 17, 2024 from https://www.ecsecc.org.za/documentrepository/informationcentre/umzimvubu-local-municipality_22245.pdf.

- Elias, M., Mudege, N. N., Lopez, D. E., Najjar, D., Kandiwa, V., Luis, J. S., Yila, J., Tegbaru, A., Ibrahim, G., Badstue, L. B., & Njuguna-Mungai, E. (2018). Gendered aspirations and occupations among rural youth, in agriculture and beyond: A cross-regional perspective. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 82–107.

- FAO. (2015). Africa invests in youth employment for food and nutrition security in Eastern Africa FAO. http://www.fao.org/africa/news/detail-news/en/c/270245/

- Fasakin, I. J., Ogunniyi, A. I., Bello, L. O., Mignouna, D., Adeoti, R., Bamba, Z., Abdoulaye, T., & Awotide, B. A. (2022). Impact of intensive youth participation in agriculture on rural households' revenue: Evidence from rice farming households in Nigeria. Agriculture, 12(5), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12050584

- Fawole, W. O., & Ozkan, B. (2019). Examining the willingness of youths to participate in agriculture to halt the rising rate of unemployment in South Western Nigeria. Journal of Economic Studies, 46(3), 578–590. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-05-2017-0137

- Geza, W., Ngidi, M., Ojo, T., Adetoro, A. A., Slotow, R., & Mabhaudhi, T. (2021). Youth participation in agriculture: A scoping review. Sustainability, 13(16), 9120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169120

- Giwu, O. (2024). Perceptions, willingness, opportunities, and effects of youth participation in agricultural enterprises [Published MSc Dissertation]. University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- Henning, J. I. F., Jammer, B. D., & Jordaan, H. (2022). Youth participation in agriculture, accounting for entrepreneurial dimensions. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 14(1), a461. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v14i1.461

- IFAD. (2015). Feeding future generations – young rural people today, prosperous farmers tomorrow. Plenary panel discussion, 34th session of the Governing Council.

- IFAD. (2016). Rural Development Report 2016: Fostering inclusive rural transformation.

- ILO. (2020). Preventing exclusion from the labour market: Tackling the COVID-19 youth employment crisis. International Labour Organization. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_746031.pdf

- Jayasinghe, P., & Niranjala, S. A. U. (2022). Factors affecting youth participation in agriculture in Galenbidunuwewa divisional secretariat division, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Journal of Rajarata Economic Review, 1(1), 110–117.

- Jayasinghe, P. W. G. S. L., & Niranjala, S. A. U. (2021). Factors affecting youth Participation in Agriculture in Galenbidunuwewa divisional secretariat division, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Journal of Rajarata Economic Review, 1, 110–118.

- Jayne, T. S., Chamberlin, J., & Benfica, R. (2018). Africa’s unfolding economic transformation. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(5), 777–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1430774

- Kosec, K., Ghebru, H., Holtemeyer, B., Mueller, V., & Schmidt, E. (2018). The effect of land access on youth employment and migration decisions: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100, 931–954.

- Magagula, B., & Tsvakirai, C. Z. (2020). Youth perceptions of agriculture: Influence of cognitive processes on participation in agripreneurship. Development in Practice, 30(2), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1670138

- Mdoda, L. (2020). Factors influencing farmers' awareness and choice of adaptation strategies to climate change by smallholder crop farmers. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 58(4), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2020.01280

- Mdoda, L., Mdletshe, S. T. C., Dyiki, M. C., & Gidi, L. (2022). The impact of agricultural mechanization on smallholder agricultural productivity: Evidence from Mnquma Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 50(1), 76–101. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2022/v50n1a11218

- Mdoda, L., Meleni, S., Mujuru, N., & Alaka, K. O. (2019). Agricultural credit effects on smallholder crop farmers input utilisation in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology, 66(1–3), 45–55.

- Mdoda, L., & Obi, A. (2019). Market participation and volume sold: Empirical evidence from irrigated crop farmers in the Eastern Cape. Journal of Agricultural Science, 11(17), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v11n17p66

- Mthi, S., Yawa, M., Tokozwayo, S., Ikusika, O. O., Nyangiwe, N., Thubela, T., Tyasi, T. L., Washaya, S., Gxasheka, M., Mpisana, Z., & Nkohla, M. B. (2021). An assessment of youth involvement in agricultural activities in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Agricultural Sciences, 12(10), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2021.1210066

- Mujuru, N. M., Obi, A., Mishi, S., & Mdoda, L. (2022). Profit efficiency in family-owned crop farms in Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: a translog profit function approach. Agriculture & Food Security, 11(1), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00345-2

- Muthomi, E. (2017). Challenges and opportunities foryouth engaged in agribusiness in Kenya. Journal of Culture, Society and Development, 17(1), 4–19.

- Ng’atigwa, A. A., Hepelwa, A., Yami, M., & Manyong, V. (2020). Assessment of factors influencing youth involvement in horticulture agribusiness in Tanzania: A case study of Njombe Region. Agriculture, 10(7), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10070287

- Nnadi, F. N., & Akwiwu, C. D. (2008). Determinants of youths` participation in rural agriculture in Imo state, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences, 8(2), 328–333. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2008.328.333

- Olarinde, L. O., Abass, A. B., Abdoulaye, T., Adepoju, A. A., Adio, M. O., Fanifosi, E. G., & Wasiu, A. (2020). The influence of social networking on the food security status of cassava farming households in Nigeria. Sustainability, 12(13), 5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135420

- Onyiriuba, L., Okoro, E. U. O., & Ibe, G. I. (2020). Strategic government policies on agricultural financing in African emerging markets. Agricultural Finance Review, 80(4), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-01-2020-0013

- Ouko, K. O., Ogola, J. R. O., Ng'on'ga, C. A., & Wairimu, J. R. (2022). Youth involvement in agripreneurship as Nexus for poverty reduction and rural employment in Kenya. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2078527. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2078527

- Owings, L. (2020). Africa's young agri-entrepreneurs nurturing the future. Bringing science and development together through news & analysis. Scidev. https://www.scidev.net/sub-saharan-africa/features/africas-young-agri-entrepreneurs-nurturing-the-future/.

- Pan, W., & Bai, H. (Eds.) (2015). Propensity score analysis: Concepts and issues. In W. Pan & H. Bai (Eds.), Propensity score analysis: Fundamentals and developments (pp. 3–19). Guilford Press.

- Popescu, A., Tindeche, C., Marcuță, A., Marcuță, L., Honțuș, A., & Angelescu, C. (2021). Labor force in the European Union agriculture-traits and tendencies. Economic Analysis, 21(2), 475–486.

- Prosper, J. K., Nathaniel, N. T., & Benson, H. M. (2015). Determinants of rural youth’s participation in agricultural activities: The case of Kahe East Ward in Moshi Rural District, Tanzania. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management United Kingdom, 3(2).

- Rubin, D. B. (2001). Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology, 2, 169–188.

- Sigigaba, M., Mdoda, L., & Mditshwa, A. (2021). Adoption drivers of improved open-pollinated (OPVs) maize varieties by smallholder farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Sustainability, 13(24), 13644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13241364

- Smith, J. (2013). How to keep your entrepreneurial spirit alive as the company you work for grows. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jacquelynsmith/2013/10/22/how-tokeep-your-entrepreneurial-spirit-alive-as-the-company-you-work-for-grows/?sh=6268b44ac0d4

- Stuart, E. A. (2019). Propensity scores and matching methods. In G. R. Hancock, L. M. Stapleton, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (2nd ed., pp. 388–396). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755649-28

- Tarekegn, K., Kamaylo, K., Galtsa, D., & Endrias Oyka, E. (2022). Youth participation in agricultural enterprises as rural job creation work and its determinants in Southern Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2022, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5760331

- Thibane, Z., Mdoda, L., Gidi, L., & Mayekiso, A. (2023). Assessing the venturing of rural and peri-urban youth into micro- and small-sized agricultural enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 15(21), 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115469

- Umzimvubu Local Municipality. (2023/2024). Integrated development plan 2023 – 2024 review. file:///C:/Users/MdodaL/Downloads/ULM%20FINAL%20IDP%20for%202023-2024%20FY%20Review.pdf.

- Wang, C., Tee, M., Roy, A. E., Fardin, M. A., Srichokchatchawan, W., Habib, H. A., Tran, B. X., Hussain, S., Hoang, M. T., Le, X. T., Ma, W., Pham, H. Q., Shirazi, M., Taneepanichskul, N., Tan, Y., Tee, C., Xu, L., Xu, Z., Vu, G. T., … Kuruchittham, V. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle income countries in Asia. PloS One, 16(2), e0246824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246824

- World Bank. (2016). Liberia skills development constraints for youth in the informal sector.