Abstract

The sustainability of the security activities in Europe currently faces a number of challenges, including budgetary and personnel pressures. Policing activities are not an exception in this respect. One position when it comes to standards relating to local public order affairs may be the involvement of the wider police family, including police volunteers. The study deals with both a certain theoretical framework of the topic and the role of security, especially police volunteering in the new European Union Member States. In doing so, it is monitored to what extent the career of police volunteers is exposed to the competition of volunteer firefighters or military-oriented volunteer groups. The situation in all 13 states is monitored and compared. At the same time, it was identified that not all volunteer projects are linked to the state – but that some potentially problematic vigilante structures are also taking place in this regard. As a result, in relation to the monitored countries, there was also an effort to find out whether it is possible to typologize the situation – with regard to security or police volunteerism in a certain way.

IMPACT STATEMENT

In relation to public interest, the authors perceive current challenges regarding public (state) security forces – and processes that aim to overcome these challenges. Their text is both an academic study, aiming to advance related expertise on the topic, and a prospective supporting document for the needs of public administration, especially in the Central and Eastern Europe countries.

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective of the study

The topic of volunteer activities regarding the ensuring of local public order affairs, as one of the possible tools for de-burdening of the police force – but also the security-related volunteering in the broadest sense of the word, is quite topical. Police, as well as other public security forces, not only in Europe, are looking for ways to sustain current standards and public expectations in this area. The presented study aims to connect related theory and practice – with a view to possible recommendations for political and security management in the relevant states (best practice, inspiring models). At the same time, there is an effort to create an indicative handle for other researchers, ideally from an environment outside of Central and Eastern Europe, who do not have a field insight into the issue and this area is sometimes on the edge of their interest. The aim of the study is also to compare the situation or approaches in the 13 surveyed new European Union Member States, and to attempt to trace certain similarities between them. Are there certain types of models to organize volunteerism connected to the police force in these countries? Or, are the related approaches completely identical? Or, on the contrary, is it the case that no similarities can be identified? These are questions that this text aims to answer.

Within the community of theorists and practitioners active in the area of policing, it has been repeatedly said that it would be an unrealistic effort by the police force to tackle crime or local public order affairs in general on its own, just solely. Intensive two-way communication between police professionals and the rest of the society can not only reduce public concerns about crime, but also improve the image of the police, increase public awareness, as well as the public’s ability to increase their resilience to illegal activities by their own means (Pate et al., Citation1986; Sherman et al., Citation1998; Shotland & Goodstein, Citation1984; Trojanowicz, Citation1983).

The success of the police in ensuring security (local public order affairs) depends on a wide range of partners. In the so-called partnership model (partnership policing), the police emphasize the work with the community to solve long-term challenges, as well as use the situational crime prevention tools and other methods in an effort to avoid or limit the use of force. The community is not considered a passive audience, but a partner for the police force (Tiedke et al., Citation1957).

In some cases, the public is required to engage in certain activities that may be sensitive, such as neighbourhood patrols and formalized concepts for reporting offenses and other issues in a particular community. On the other hand, making the public actively involved in such form of civic engagement usually requires a high level of social capital and trust in the police.

This aspect is important for the sustainability of the standards of policing, including local public order affairs, the spectrum of which is under pressure. Clearly, maintaining a generally acceptable level of service and saving costs at the same time is a challenge for police forces. Sometimes it is possible to hear about the reduction of the role of police officers to the ‘extinguishing of the security fires’. Some police forces have responded to this challenge by reducing their commitments. Others were aimed at replacing ordinary police officers with support staff, including volunteer forces undergoing a short training program. In this way, the police force can, according to their own statement, withdraw individual police officers from tasks that do not require their specific skills, powers and training. However, this increases the public’s sense of insecurity and fear of crime, because security activities will be on the shoulders of non-professional individuals (Mills et al., Citation2010).

Representatives of some countries state that their police forces, as well as municipal guards, are exposed to two pressures (see ): a lack of funds and a lack of suitable candidates for the job. This inevitably leads to the fact that individual states are putting pressure on other actors, including the non-governmental organizations and private sector, to fill the vacancy, so as not to suddenly lower security standards in a given area (Hřebík & Krulík, Citation2018; Krulík, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Sustainability of local public order affairs agenda as an intersection of several positive and negative trends (own elaboration, on the basis of Hřebík & Krulík, Citation2018 and Krulík, Citation2014).

1.2. Material and methods

In the context of the study, there is an attempt to integrate the following four sub-methods, which the authors perceive as implicitly connected:

1.2.1. Literary research

In relation to the monitored countries, observations on the topic are being extracted. This will enable the reader to gain an overview of aspects that have already been the subject of research in the past – as well as to identify gaps in existing knowledge (see chapter 1.3).

Integration of existing data, ideally in a comparable form and scope (in terms of individual states of interest): In this regard, the authors will partially use their own secondary studies prepared in the past (see chapters 2 and 3).

1.2.2. Comparative analysis

Aspects and parameters that will be evaluated as appropriate – to demonstrate key similarities and differences, the authors integrate side by side, ideally in the form of table overviews (see chapter 2, especially the respective tables, as well as chapter 4). Indicatively, the context of the situation in the observed countries will also be monitored, especially regarding their historical, social or other experience and tradition (see ).

1.2.3. Formulation of recommendations

Based on everything mentioned above, recommendations will be formulated for decision-making public officials and other interested parties.

Primal hypothesis that can be formulated in this regard is that within the monitored states, especially within the states with a socialist tradition (it means, except the Malta and Cyprus), it is possible to trace significant similarities regarding the public parts of their security systems – and these similarities also spill over to work with volunteers in the security-police area.

At the same time, it is possible to formulate a secondary hypothesis, that due the absence of emphasis by the monitored states regarding some security challenges, security volunteering can help to create a form of negative self-definition against the state, which – through the perspective of some inhabitants – does not fulfil its basic obligations towards the population.

1.3. Literary research: relevant secondary studies on security-related volunteering and extended police families

Some aspects of the study are mentioned in a number of relevant recent secondary studies that can serve as a springboard for further reflection. These approaches can be structured into several clusters:

Studies considering the necessity of engaging the wider security (or the police) community in ensuring a generally acceptable level of security standards (in general, or regarding specific states, not necessarily regarding the new European Union Member States):

References to plural policing and extended policing family are a common part of discussions about policing in modern societies. Various networks of commercial bodies, voluntary community groups, individual citizens and national or local regulatory agencies, now provide police work. The number of contracts of public administration bodies with private security services is also growing. Governments, as well as municipalities, apply for the services, which were recently unthinkable. However, private companies are not always subject to the strict regulatory frameworks typical for public police forces (Crawford, Citation2005, Citation2008; Jones & Newburn, Citation2006).

Geographical-sociological approaches should also be mentioned, aiming to decipher the complex nature of plural policing at local and national levels. Their treatise provides information on how the procedures concerning the police system reflect the influence of history and geography. The text focuses mainly on the relationships that have emerged in the public sector through pluralization processes, in particular the establishment of institutes of various police assistants or municipal guards. The authors show that experience with pluralized police varies widely across Europe and question the role of neoliberal concepts in this regard (O’Neill & Fyfe, Citation2017).

Some of the key factors of the respective concept are seemingly well established (ranging from fundamental shifts from a culture of control and a ‘myth of a monopoly of a sovereign state’ towards recognizing the role of private, municipal and volunteer actors in managing and preventing criminal and/or illegal activities) (Garland, Citation2001).

Some relations that have emerged in the public sector through its pluralization (creation of auxiliary or municipal police services; multilevel policing) are a challenge for the police forces themselves. There are difficulties in defining a police professional identity as well as regarding the relationships with the community. There are voices arguing that certain tasks are not a priority for the ‘real’ police and that these tasks should be taken over by municipal guards or volunteers, however differently defined (Loader, Citation2000).

Possible impacts of certain developments at the micro-regional level are also monitored – with an emphasis on public involvement in local security-related associations. Sometimes there is an effort to reduce crime, to obtain information from the public – and other times there is ambition only to strengthen trust in the police and to build social capital at the local level. The main goal of the whole effort is to bridge the isolation of the police (police-security community as a whole) from the rest of society. If communication between police forces, municipalities and the public became more efficient, a number of issues would be resolved. It is not necessary to conceive every meeting with the public as handling with the complaints – even ‘friendly gossip’ is appreciated. Communication must be a two-way process: not only does the police want information or other forms of support from the public, but it must also offer the feedback, the possibility of active involvement in solving problems. Even the mere distribution of questionnaires and evaluation of the answer gives the public a signal that someone is interested in their attitudes (Sharp, Citation2012).

At the same time, it is heard that the model, based on the active participation of the public in formulating and solving security-police challenges, must be understood not as a positive exception but as a standard, that should be established everywhere (Foster & Jones, Citation2010).

Volunteers can also be used for communication with the public – including the management of online communication channels. Internet social media are fast and almost free. They can immediately reach a large group of people, provide the public with information, advice on crime prevention or distribute a request for help (Procter et al., Citation2013). If the police force really wants to communicate with the public, it is necessary to answer potentially relevant questions and suggestions quickly. This way is much more probable to create a positive perception of police activity. These activities can also be carried out by variously defined volunteers or professions associated with the police force. If there is not enough capacity for such a response and the whistle-blowers conclude that their suggestions are useless, or even burdensome, they will not initiate any further communication or cooperation (Cheurprakobkit, Citation2002; Colvin & Goh, Citation2006; Cordner, Citation2000; Greene & Mastrofski, Citation1988).

The usability of all the above-mentioned studies regarding the situation regarding the new European Union Member States is, however, relatively limited. Most (almost all) of the above studies, seeking to frame the issue in some way, come from the academic environment of North America or Western Europe, and thus dominantly focus on the situation and security environment there. For this reason, too, this study was created, seeking to supplement the described issues with experience from the environment of the new European Union Member States.

Studies focused on the situation and trends within the security (police-security) environment of the new European Union Member States.

In addition to more or less encyclopaedic overviews, in which one must perceive their obsolescence over time (Bohman & Krulík, Citation2009; Krulík et al., Citation2022), there are also outputs that try to aggregate the reactions of expert groups from different parts of Europe. It is also possible to come across expressions made by an experienced expert from Central and Eastern Europe (without incorporating the attitudes of experts from Malta and Cyprus), which are often perceived as substantially different, compared to expressions of the experts from other parts of Europe. Some respondents conceived in this way are of the opinion that the police force can be very short-sighted, parochial, dealing with local issues, focused on the community. At the same time, crime is increasingly international (global). Thus, what many academic authors perceive as a benefit, as a pillar of the concept of community policing, is criticized here. It is emphasized that the walking patrol activity itself, as rhetorically glorified, is a relatively unproductive part of police activities, which does not seem to fit into 21st century – and should be delegated to regions, municipalities (municipal guards), volunteer structures, etc., with the proviso that this does not belong among the ‘really fundamental police activities’ (Caless & Tong, Citation2015).

Studies relat ed to the topics of volunteering, security-related or directly police-related – in one or several states

In relation to this partial passage, it is possible to claim that ‘the supply determines the demand’ and no ambitions were identified here (unlike the study presented here itself) to cover the entire spectrum of the new European Union Member States.

The authors’ attention can be paid to the personnel substrate of volunteers, its motivation and quality – independently or in the context of economic and social development in a certain state. Specifically in Israel, the role of volunteering (for the military as well as the police) grows as the recruitment potential of state security forces and their competitiveness on the labour market decreases, especially in times when the economy and wages are growing. Volunteers are also a source of legitimacy for both police and armed forces. They create a supply of workforce for more fundamental deployments and provide a wealth of skills and specializations. Some security professionals, however, view volunteers as un-utilisable (Ben-Ari & Lomsky-Feder, Citation2011).

If we return to the aspect of motivation for volunteering, then there are definitely opinions that the rise of volunteering activities, not only in the security-police area, is accompanied by attitudes that it is a necessity, caused by the alleged failure of the market or the state, at least regarding the specific time and space (Frič & Pospíšilová, Citation2010).

Regarding studies that were either created in the environment of Central and Eastern Europe, or by authors who deal with these countries to a greater extent, an opinion resonates that it is appropriate to give up on forming a comprehensive theory in the respective area, as the systems of the monitored countries are considerably different. In their view, the Central and Eastern Europe are a diverse mosaic, especially when it comes to consolidating democracy and stability.

Although these countries share common political, economic and social legacies from their recent experiences – and relics of the Soviet or Yugoslavian model continue to emerge within the security-police forces of these countries as well – these aspects have weakened over time. The monitored countries are increasingly taking different paths. At the same time, the homogenizing effects of the implementation of relevant international and European Union standards are also visible.

Despite structural and procedural reforms in the military, police and other organizations throughout the region, the overall results are not yet fully satisfactory. Some reform steps take place rather on the surface (change of uniforms or equipment, fleet, etc.) and do not penetrate the essence. The transformation of an authoritarian security system is not something that can be achieved quickly, but it is a long-term process that requires years of reforms and investments. The authors of the respective studies, however, usually do not directly deal with the issue of security-police volunteering. They limit themselves to aspects of connecting security forces with the public, including the concept of community policing. The dominance of the state role in the security environment stems from tradition, the new trend is the privatization of some activities rather than increasing the role of volunteers (Caparini & Marenin, Citation2005). If the issue of volunteering in the field of security, especially with regard to local militia, is not addressed by the state, this topic will easily fall into the lap of extremists and populists (Kučera & Mareš, Citation2011; Mareš, Citation2012).

The widest identified overview that touches the area of interest maps paramilitary units within the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia, and also within Ukraine. At the same time, it sounds that there are two basic models here (however, primarily in terms of paramilitary structures, not in terms of the topic of local public order affairs) – state dominance in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland; and conversely, the absence of state coordination and a potentially large space for pro-Kremlin militias – especially visible in Slovakia (Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia) (Kandrík, Citation2020).

2. Public police-security forces in the monitored states

In the context of the topic, attention is paid to how police and other security forces (bodies that are dominantly focused on ensuring specific aspects of internal security and public order) are conceived in the monitored countries. For this purpose, encyclopaedic meta-studies created in the past were used as a springboard. The result is an overview that is as practical as possible, a background for further comparisons and drawing relevant conclusions (see ).

Table 1. Existence of public police-security forces in the monitored states, generally since 1989–1990 (Bohman & Krulík, Citation2009; Krédl, Citation2016; Krulík, Citation2015b; Krulík et al., Citation2022; Krulík & Bohman, Citation2012; Valta & Vangeli, Citation2012).

Based on the content of the table and other information that has already been mentioned in the text, the following can be stated – with an emphasis on trying to find relevant similarities and differences (Bohman & Krulík, Citation2009; Krédl, Citation2016; Krulík, Citation2015b; Krulík et al., Citation2022; Krulík & Bohman, Citation2012; Valta & Vangeli, Citation2012):

Some of the monitored countries are characterized by a relatively complicated system of bodies responsible for law enforcement activities and ensuring local public order affairs. Typically, there are several bodies that are part of the state’s security system, and in addition there are bodies established by municipalities: municipal guards. These countries in the monitored group include Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, with some reservations, also Latvia and Lithuania.

Other observed states are characterized by a relatively centralized model, where one national security force and municipal or multi-municipal bodies exist side by side. This group includes the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and, since the 2010 reform, Estonia.

There is also a model where the agenda of internal security and public order is concentrated within one body at the state level, and where the potential of building municipal bodies is considerably limited: Croatia.

Not long ago, a similar situation prevailed in Cyprus, but now it is possible to witness reforms here, based on strengthening the role of municipalities, as well as the mergers of municipalities into larger units, including the process of creating more relevant municipal control and security bodies.

The last case is represented by Malta, where, in addition to the existence of a national police force, the process of nationalizing of the municipal police bodies (which were previously, in fact, provided by private security service personnel) is currently underway.

In all monitored countries it is, more or less, possible to see the pressures related to the sustainability of the standard of the security situation and the provision of local public order affairs. If we limit ourselves to the personnel aspect of the issue, it is not possible to overlook the ‘tussle’ for ideal officers or workers between individual state law enforcement forces and bodies, or between the state and municipalities. Other competitors here are other state security forces that do not directly address the agenda of law enforcement or local public order affairs (armed forces, customs service, penitentiary service, intelligence services or other specialized bodies). After all, the bodies already mentioned in the previous text, such as the gendarmerie or the border guard, are located ‘on the edge’ of this agenda. Another competitor is, of course, the private security sector.

In practically all the monitored states, there are opportunities for the public to volunteer in the security area. However, these opportunities are sometimes not covering an agenda of internal security and local public order affairs (see ). Leaving aside the national Red Cross organizations that exist in all of these states, there are four basic areas of potential security volunteer engagement:

Engagement auxiliary to the armed forces.

Volunteer firefighters.

Rescue platforms (rescue of people in the countryside or at sea).

Agenda of internal security and public order in the narrower sense of the word.

Table 2. Summary of findings on the security-volunteer base within the new European Union Member States (on the basis of the resources in the previous text).

A very specific area is represented by various militia or vigilante platforms, which can be straddled between the military, police and border management agenda. A significant proportion of these platforms in the new European Union Member States have systematically resigned to the cooperation with the state, and these are highly anti-system bodies. The orientation of these platforms towards seeing the world through the lens of the Kremlin is no exception, but a rule.

The following passage shall attempt to briefly describe the mentioned variables with respect to the individual monitored states.

3. Individual national models

3.1. Bulgaria

3.1.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The opportunity for volunteer activities in the security area in the country is rather limited with regard to social tradition in Bulgaria. The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged, is population protection. It is worth mentioning organizations such as the mountain rescue service and the water rescue service, whose activities are significantly manifested during various emergencies (Национална асоциация на доброволците в Република България).

3.1.2. Internal security and public order volunteer positions

This aspect is present only to a very limited extent. Note: Bulgaria is a country where there is a very wide spectrum of private security activities, including the provision of certain tasks that fall under the local public order affairs (Krulík & Krulíková, Citation2014).

3.1.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

With regard to non-state vigilance initiatives, the current situation is significant in terms of the formation of several groups that focus on combating illegal migration to Bulgaria (especially from Turkey). Police officials (and most of the public, with the Helsinki Committee’s national branch being the most notable exception) largely appreciate these initiatives, as they call the patrol members not to put themselves at risk and just to keep the responsible authorities informed about identified border violations. These platforms include the Citizens’ Protection Organization (Организация за закрила на българските граждани), which organizes ‘forest walks’ during which dozens of illegal migrants have been detained, and the Civic Squads for the Protection of Women and Faith (Цивилните отряди за защита на жените и вярата), which operates around Burgas. In connection with border protection, as well as with the broader paramilitary agenda, it is necessary to mention two interconnected platforms, which in both cases define themselves as patriotic, Slavic and pro-Russian: the Bulgarian National Movement ‘Arrow’ (Българско Национално Движение ‘Шипка’) and the Military Unit ‘Vasil Levskij’ (Български Воински Съюз ‘Васил Левски’) (Self-Appointed Defenders…, 2019).

3.2. Croatia

3.2.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is the population protection (including rescue operations during major disasters) (Fabac et al., Citation2015).

3.2.2. Internal security and public order volunteers positions

The opportunity for volunteering in relation to local public order affairs is apparently reduced to the area of community policing or building communication channels between the police and the general public (Karlović et al., 2017; Together We Can Do More, Citation2020).

3.2.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state initiatives of the vigilants, in the context of Croatia, these are dominantly related to efforts to mitigate the effects of migration pressures on the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, but these are ad hoc initiatives (Pantovic, Citation2020).

3.3. Cyprus

3.3.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country, are neighbourhood watch patrols, discussed below in the text (Krulík, Citation2019).

3.3.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

There were several stages in relation to security volunteering or neighbourhood watch patrols in Cyprus. Until 2010, these activities were explicitly spontaneous, in which the state and the national police force did not intervene in principle. One of the pioneers of the concept was the municipality of Peyia (around 12,300 inhabitants), where a large number of people from the United Kingdom live permanently or temporarily. From 2010 or 2011, the state became more active in this regard, with efforts to establish a position of a police liaison, responsible for property protection and certification and training of members of potential neighbourhood patrols in every larger settlement.

A model for reporting suspicious behaviour, formalized walking routes, volunteer ID cards and communication channels between volunteers and the police was created. Here, the city of Dhali (about 10,400 inhabitants) became a model, and specifically Peyia joined the formal concept as one of the last municipalities. However, the result has caused frustration, and the state model is sometimes referred to as ‘Potemkin Village’. Although the Cyprus excels in international comparisons (around 6.5% of the population, up to 185 involved municipalities or settlements, 100,000 people involved in neighbourhood patrols, 89% of the population declaring an increased sense of security, etc.), the real impact of the state supported volunteers projects, compared to spontaneous patrols, is reportedly worse. Therefore, again within Peyia, today there are two platforms, a state-coordinated and renewed informal platform, that is said to be much more effective (up to 1,000 members, a functional internet portal, a sophisticated alert system and an overlap with many other societal activities) (Browne, Citation2016; Crime Prevention Office; Neighbourhood Watch; Republic of Cyprus Police…, 2017).

3.3.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

As for the non-state initiatives of vigilantes, they are not mentioned in relation to this state in open sources, or such activities exist just at the level of individuals.

3.4. Czech Republic

3.4.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is population protection, represented by volunteer firefighters, who, however, are also involved in a whole range of other activities at the community level (this is about 70,000 people actually carrying out activities in the field, and in addition up to 290,000 other organized people, including youth). The personnel base of the Active Reserves, affiliated with the armed forces of the state, is currently on the rise (now about 3,700 members) (Aktivní záloha; Stejskal, Citation2013).

3.4.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

Volunteering in this area (as in several other countries of the region) enjoys an ambiguous image due to the existence of the Auxiliary Public Security Guard (Pomocná stráž Veřejné bezpečnosti) during the communists’ era. Efforts to restore a volunteer base affiliated with the national police force or the municipal guards over the past 20 years have been, with exceptions, unsuccessful, and probably only about 30 people in about 5 municipalities are involved in related projects (Projekt “Bezpečnostní dobrovolník”).

3.4.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state initiatives of the vigilantes, pro-Kremlin projects Czechoslovak Soldiers in Reserve – For Peace (Českoslovenští vojáci v záloze – za mír), National Militia (Národní domobrana) and Homeland Militia (Zemská domobrana), which were created after 2015, are so far more of a rhetorical platforms. A big impetus for their activation was the tension in society in connection with anti-coronavirus measures (Božek & Tušer, Citation2021; Tušer et al., Citation2021).

In connection with developments in the post-Soviet area, it should be mentioned that several members of the respective militias have already been involved in fighting on the territory of Ukraine (on the side of pro-Russia separatists) (Zelená, Citation2015).

3.5. Estonia

3.5.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

There is a hugely developed volunteer aspect in Estonia. An important element of Estonia’s security system is the Defense League (Eesti Kaitse Liit). The main mission of the League is to increase the potential of defending the independence of the state. The organization’s membership exceeds 10,000 men, together with the associated women’s, boys’ and girls’ organization, even 20,000 members. The League is an integral part of the Armed Forces of Estonia, including participation in exercises and foreign missions. At the same time, the League is directly linked to the agenda of local public order affairs. Since 2004, the cooperation memorandum, which has been renewed every year, provides for the all-round involvement of League members in certain police activities, for example, the search for lost persons. The League’s cooperation with the Rescue Service of Estonia is subject of a memorandum from 2007, regarding, for example, the possible deployment of League members in the event of floods or forest fires. The League also concludes cooperation agreements at the regional or municipal level, and in this way in some cases replaces the municipal police. There is also a cyber-defence unit within the League, interconnecting also computer scientists and other experts from the civil sector. Inspiring is the robust system of compensation for police volunteers and members of the League in the event of death or injury in the line of duty. There is also a dense network of volunteer rescue bases in the country (at least 115 stations located so that every part of the country can be reached within 15 minutes). About 2,200 volunteers work within them. The financial support of the state for this service amounted to around 1.3 million euros annually, plus other equipment (Kaitseliit; Krulík, Citation2010; Krulík & Linhart, Citation2013; Loik, Citation2020; Päästeliit).

3.5.2. Internal security and public order volunteer positions

In Estonia, there are also auxiliary police officers in the proper sense of the word (abipolitseinik). The volunteer perspective within the police force existed since April 1994. Volunteers mostly come from a patriotic background, where there is social pressure to help the police. The applicant undergoes a comprehensive background check, but is then treated as a full-fledged police officer, including the possibility to use a service car, a weapon and access to information systems. These volunteers also work in the ranks of the criminal police. Volunteers who carry out activities primarily with regard to local public order affairs are often tasked (and partly funded, thus relativizing the concept of volunteering) by individual municipal authorities. In 2019, there were 1,100 volunteers, of which 406 were also members of the League. Annually, these persons performed an average of more than 90 hours of activities, especially errand patrols. The volunteer must meet the following requirements: at least 18 years of age, Estonian citizenship, completed primary education (secondary education, in the case of autonomously acting volunteers) and completion of the relevant educational course. Since 2015, persons possessing a firearms or driver’s license do not need an additional medical examination. There is also an effort to use the previous education and experience of the volunteers (Abipolitseinik; Keisk, Citation2019; Number of Volunteer Police Officers…, 2017).

3.5.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

As for the non-state initiatives of vigilantes, they are not mentioned in relation to this state in open sources, or such activities exist just at the level of individuals.

3.6. Hungary

3.6.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is the area of local public order affairs, sometimes combined with the nature protection.

3.6.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

A significant part of the security structures of Hungary is the volunteer platform, the Civil Guard (Polgárőrség), whose roots date back to 1991. The umbrella organization, connecting national, regional (county) and local volunteers, is the National Civil Guard Association (Országos Polgárőr Szötségés, OPSZ). Over time, the Association’s communication with the state changed – instead of criticizing the police force for objective and subjective failures, a stage of symbiosis occurred, when the state literally ‘pampers’ the security volunteers. Permanent consultations are held between the government (state) and the Association. The state financial support for the Association has gradually increased and is now around 1 billion forints (about 2 million euros) per year. In addition, it is necessary to mention some other support, for example in the form of vehicles and other equipment. In 2019, the Association has more than 60,000 members in approximately 2,000 local organizations. The volunteers can use around 1,200 cars and many other vehicles (Christián, Citation2017; Országos Polgárőr Szövetség).

3.6.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Hungary is one of the countries where the objectively or subjectively perceived limited level of safety in some localities led to the search for solutions along the lines of politically profiled (extremist) groups, promising a ‘firm hand rule’. The first wave (2007–2009), which could be perceived in this way, was related to the Hungarian Guard – Association for the Protection of Tradition and Culture (Magyar Gárda Hagyományőrző és Kulturális Egyesület), linked to the Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom), then extremely nationalist platform. The Hungarian Guard, reportedly numbering several thousand members, was banned by court in 2009, but other groups followed it. The second wave (2009–2014) is embodied by the Hungarian Self-Defense Movement for a Better Future (Szebb Jövőért Magyar Önvédélem). The third wave (from 2014 to today) is represented by the Hungarian Self-Defense Movement (Magyar Önvédelmi Mozgalom, MÖM), and other smaller ‘self-defense’ and ‘youth’ organizations, oriented, at least, to the Great Hungary ideology. In parallel with this, some municipalities (such as Tizsavasvari), where the Movement for a Better Hungary ruled for a certain time, based on the results of the municipal elections, established their own municipal security bodies, focused on ‘Roma crime and the fight against usury’. Specifically, in Tizsavasvari, this body was named gendarmerie (Csendorség), which reminds many of the end of World War II and the eponymous pro-Nazi militia. Over time, the situation shifted and there was a boom in official municipal security bodies of all kinds. As mentioned above, there has also been an increase in the number of official security volunteers. This resulted in a practical ‘tunnelling’ of the space previously occupied by extremists and its filling by bodies supported by the state or municipalities. In today’s Hungary, it is thus possible to perceive extremist security initiatives to a much more limited extent than 10 years ago. Today, even the Movement for a Better Hungary is perceived as a ‘standard’ right-wing populist platform. The most visible cases of vigilantism in this regard are the bodies associated with the Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) movement, which separated from the Movement for a Better Hungary in 2018 and which is led by László Toroczkai, Mayor of Ásotthalom from 2013 to 2022. This municipality, right on the border with Serbia, has been the scene of a number of incidents related to migration along the so-called Balkan route. At the peak of the wave of migration, crime here increased sharply (vehicle theft, vehicle break-ins, various forms of harassment). The local municipal guard was allegedly supported by volunteers belonging to the so-called National Legion (Nemzeti Légió). Thanks to the media coverage, Toroczkai became a nationally known politician who targeted the abandoned national-chauvinist electorate. Now he is a member of parliament, involved, among other things, in the idea of restoring the borders of Hungary before 1918 or speaking out against the ‘dictate’ of the European Union and for ‘strengthening friendship with the Russian Federation’. However, the National Legion was abolished in 2020, to be merged with the Hungarian Self-Defence Movement (Magyar Önvédelmi Mozgalom; Wenn Ex-Türsteher Jagd auf Flüchtlinge machen, Citation2016).

3.7. Latvia

3.7.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country are platforms associated with the armed forces. The armed forces of Latvia consist of regular forces and a volunteer component, the National Guard (Latvijas Republikas Zemessardze), which is reported to have around 8,500 members. However, the situation may be modified by the reintroduction of compulsory military service in Latvia in 2023. Others are members of the youth affiliated organization, Youth Guard (Latvijas Republikas Jaunsardze), which is probably the largest youth organization in Latvia (Jaunsardze; Krulík, Citation2015a; Latvijas Republikas Zemessardze; Mandatory Conscription for Military Service…, 2022).

3.7.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

If necessary, the National Guard can also be used to perform tasks falling within the provision of local public order affairs (Latvian National Guard – Zemessardze; National Guard Helping Police Enforce Lockdown, Citation2021).

3.7.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

As for the non-state initiatives of vigilantes, they are not mentioned in relation to this state in open sources, or such activities exist just at the level of individuals.

3.8. Lithuania

3.8.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country are platforms associated with the armed forces. The armed forces of Lithuania consist of regular forces and a volunteer component, the National Defence Volunteer Forces (Krašto apogosso savanorių sajkos), which has a task force of 4,900 people. In addition, this volunteer platform is connected to another military-security organization, the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union (Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga; Šauliai). Additional information is, that military service has been reintroduced in Lithuania since 2015 (Conscripts; Krašto apsaugos savanorių pajėgos; Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga).

3.8.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

A certain tradition in the monitored area is represented by volunteers working with militiamen during the time of the Soviet Union (savanoris milicija). Critics of the concept noted that participation in related activities was often motivated by benefits such as extended vacation or outright cash bonuses. That is also why there were approximately 200,000 such volunteers in Lithuania in 1987. Although the concept of police volunteers in Lithuania is said to still exist at present, it does not seem to arouse much public interest. Far more common are joint patrols by representatives of several control authorities (nature protection, veterinary services) accompanying municipal police officers, if they are active in the municipality. Other members of the patrols can be people from among the volunteer platforms, associated with the army. For example, such patrols can be seen during some festivals (Urnikienė, Citation2017).

3.8.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

As for the non-state initiatives of vigilantes, they are not mentioned in relation to this state in open sources, or such activities exist just at the level of individuals.

3.9. Malta

3.9.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is rescue in the broadest sense of the word. The flagship volunteer platform of its kind in Malta is the Emergency Response and Rescue Corps (ERRC), a non-profit organization dedicated to preventing and alleviating human suffering, improving the situation of the most vulnerable – all with the utmost impartiality and without discrimination. The organization operates in the field of first aid, rescue services, rescue training, disaster response, civil protection, etc. It also provides assistance to public institutions. In the summer months, it also provides rescue services on some beaches around the archipelago, as well as first aid during public events with the participation of a large number of people. There is also a section for youth cadets within the organization (Emergency Response and Rescue Corps).

3.9.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

Within the country, volunteers involved in the police and security field play a rather supplementary role. The Emergency Response and Rescue Corps assists the state police force, but also the armed forces, if necessary, especially in the implementation of specialized rescue programs. Currently it is most often the provision of rescue or other services for illegal immigrants, if these services do not conflict with the mission and purpose of the organization (Emergency Response and Rescue Corps – Euroopa Liit).

3.9.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state vigilante initiatives, this aspect was mentioned in Malta especially in 2015 and 2016, when the country faced serious migration pressures, and when an attempt to create a branch of the so-called Soldiers of Odin (primarily a Northern European extreme right platform) was recorded on this archipelago (Pace, Citation2016).

3.10. Poland

3.10.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The years 2021 and 2022 are marked by significant support for volunteers attached to the armed forces of Poland – the so-called Territorial Defence Force (Wojska Obrony Terytorialnej). Current is the increase in the number of volunteers from around 32,000 to more than 50,000, as well as investment in strengthening the professional army as such. However, military volunteers are financially motivated in some way, which distorts the definition of volunteering. In addition to the Territorial Defense Force, there are also smaller, rather regional or local projects that operate in a certain cooperation with the state – and usually use its training capacities. In addition, there is a base of fire rescue volunteers in the country, the Voluntary Fire Service (Ochotnicza straż pożarna), which is reported to have around 16,000 members (In Poland, More than 13,000 Volunteers…, 2022; Ochotnicza Straż Pożarna; Poland Launches Paid Voluntary Military Service, Citation2022; Wojska Obrony Terytorialnej; Związek Ochotniczych Straży Pożarnych…).

3.10.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

There is no volunteer structure linked explicitly to the police force in Poland. In times of peace, however, army volunteers can be deployed on a wide range of tasks, including guarding buildings or borders and patrolling in the event of a general threat. Peace Patrol (Pokojowy Patrol), volunteers on the eastern border of Poland, who have been operating there since 2021, are perceived rather as uncritical supporters of any migration, including migration organized through Belarus to Europe from the countries of the Middle East. The current situation, typified by the wave of refugees from Ukraine, is still very unclear and requires some time to evaluate (Jackova & Nagyidaiova, Citation2022).

3.10.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state initiatives of the vigilantes, they relate in particular to the subculture of football hooligans, which is often racist and, in some cases, pro-Kremlin oriented. With exceptions, however, this is not routine errand activity, but generally only individual incidents or excesses (Indians Attacked in Polish Border Town…, 2022).

3.11. Romania

3.11.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is population protection (about 130,000 volunteer firefighters, pompieri voluntari). Volunteer capacity building associated with the military (rezerviştilor voluntary; voluntary reserve) dates back to 2017 (Romanian Army Plans to Hire 2,800 Voluntary Reserve Troops, Citation2017; Servicii Voluntare/Private).

3.11.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

Local public order affairs are in some cases handled by the Local Public Order Commissions (Comisia Locală de Ordine Publică), which are part of the local government – and where representatives of the municipality, the local police and the public meet. In specific cases, this may provide space for locally focused security volunteers (Comisia Locală de Ordine Publică).

3.11.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

As for the non-state initiatives of vigilantes, they are not mentioned in relation to this state in open sources, or such activities exist just at the level of individuals.

3.12. Slovakia

3.12.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is the population protection (specifically, about 37,000 volunteer firefighters; dobrovoľní hasiči). In addition, since 2016, efforts to build a volunteer component associated with the state’s armed forces have been visible in Slovakia. However, this concept has so far attracted the attention of only tens or several hundreds of people – regardless of the effort to motivate interested persons with financial contributions, which relativizes the volunteer aspect of the whole activity (Dobrovoľní hasiči; Dobrovoľná požiarna ochrana Slovenskej republiky; Dobrovoľná vojenská príprava).

3.12.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

Since 2002, volunteer activities in this area can be carried out by so-called voluntary guardian of public order (dobrovolní strážci poriadku), affiliated to the Police Force of the Slovak Republic. The help of volunteers can be used in the protection of public order and the state border, in the supervision of the safety and management of the of road traffic, especially during larger safety actions. The time and place of performance of the tasks of the guardian is determined by the competent police department, after agreement with the individual volunteer. A guardian can be a person who has reached the age of 21, is capable of legal acts and enjoys trust and respect among the public. The guardian performs tasks only in the presence of a police officer and according to his/her instructions. All activities are carried out without the right to remuneration. Another option that allows citizens of Slovakia to get involved in ensuring public safety is the Night Ravens project (nočné havrane), aimed at increasing the safety of children and youth during weekend evenings. In some cities, this model, inspired by the Nordic countries, has been operating for more than two decades. The volunteers cooperate mainly with the local administration and the municipal police, who will only be called if it is absolutely necessary. Roma citizen patrols are also used in Slovakia – especially in municipalities where there are significant Roma settlements. Volunteers take care of cleaning and protecting the environment, but they can also fight truancy and other socially pathological behaviour of children and adults (Nočné havrany, Citation2017; Romská hlídka vzbuzuje respekt, Citation2018; Rundesová, Citation2005; Valkovský, Citation2014).

3.12.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state initiatives of the vigilantes, the most worth mentioning are the Guards of the People’s Party Our Slovakia (hliadky Ľudovej strany Naše Slovensko), which has existed since 2016. At first, they appeared mainly in trains, but gradually they are used as an ad hoc public relation instrument in other localities where the incidents with Roma or other ‘ideological enemies’ were reported. The People’s Party Our Slovakia represents a platform, which is described as far-right and at the same time openly pro-Kremlin. In addition, at least since 2015, there has been a paramilitary platform People’s Militia (Lidová domobrana), since 2019 transformed into the project Slovak Conscripts (Slovenský branci), or Our Homeland is the Future (Naša vlasť je budoucnost), with allegedly hundreds of active members – and many times more supporters on social networks. The project, which officially ceased operations in October 2022, was clearly pro-Kremlin, striving for cooperation with ideological counterparts from the Czech Republic. On the one hand, its promoters called for the reintroduction of compulsory military service, on the other, they proclaimed in advance ‘not to raise weapons against Russia’ (Benčík, Citation2017; Kotlebovci opäť spúšťajú hliadky, Citation2021; Malecký, Citation2019; Mareš & Milo, Citation2019; Na válku připraveni!, Citation2015; Slovakia to Ban Far-Right Train Patrols by Vigilantes, Citation2016).

3.13. Slovenia

3.13.1. Predominant type of security volunteer engagement

The dominant area where security volunteers are engaged within the country is population protection. These are up to 60,000 voluntary firefighters (prostovoljni gasilci) (Volunteer Firefighters; Gasilska zveza Slovenije).

3.13.2. Internal security and public order volunteers’ positions

Within the framework of open sources, these are mentioned only ad hoc approaches, patrols around the border with Croatia, not mentioning the vigilantist projects, see below (Stojanovic, Citation2019).

3.13.3. Vigilante platforms and their characteristics

Regarding the non-state initiatives of the vigilantes, an unmissable phenomenon is the paramilitary platform, the Slovenia Guard (Garda Slovenska), formed by the merger of the Styria Guard, the Kranjska Guard and other regional groupings of a similar nature. Slovenia Guard still exists despite state pressure, and it is worth noting that the platform also attracts senior citizens. One of the engines of the organization is the anti-immigration agenda, which over time, however, was taken over by the mainstream political parties in Slovenia. It is difficult to perceive the Slovenia Guard itself as a pro-Kremlin group, as the political party directly or indirectly related to it, the Slovene National Party (Slovenska nacionalna stranka), is definitely a channel that does not spare efforts to present and ‘understand the views’ of the Russian Federation on specific aspects, including the war in Ukraine (Andrej Šiško želi Štajersko vardo predstaviti predsedniku Borutu Pahorju…, 2019; Varda Slovenska).

4. Results and discussion

If we map the results of the study indicatively, they are as follows:

4.1. Literary research

In the studies to date, the observed topic has been followed rather indicatively, without connecting all its levels: a) the territory of the new European Union Member States; b) the volunteerism and c) the functioning of security and security-police bodies.

Also for this reason, the study continues in the direction of integration of existing data, if possible in a comparable form and scope. The authors partly use their own secondary studies, prepared in the past. This integrated, collected matter is perceived by the authors as a springboard for other interested researchers. The presented study is not radically polemical or confrontational in relation to the existing secondary output in the monitored area – rather, it aims to bridge the objectively existing information gap.

The same applies to subsequent comparative analysis, the core of which are the respective tables. The context of historical and social experience and tradition in these countries is also indicatively mentioned here, which also extends to the topic of security-police volunteering. If at this point we try to recapitulate the information about the research methods used, or rather about the data collection techniques, it should be reiterated that the authors used both their field experience and observations from a number of meetings with foreign partners. In the same way, secondary outputs of the authors, usually dedicated to the situation in a specific country or group of countries, came to the fore. In an attempt to compare and constructively-critically evaluate the situation in the selected group of states, no major information gap was identified, including mapping of current developments.

Recommendations for the state and public actors of the observed countries are generally difficult. The agenda as a whole depends on political courage, where investments in ensuring internal and external security compete with other expenditure items, for example in the social area. At the same time, the public budgets of European countries are generally in bad shape. However, the ‘peace dividend’ is apparently a thing of the past, as is the sharp drop in registered criminal activity in the era of anti-coronavirus measures. However, challenges in the area of internal security (and protection of the population) are generally less emotional and there is more political consensus about them than in the area of investment in defence (including efforts to attract professional personnel and volunteers to related forces or bodies).

It is also possible to state, that if there is an objective or subjective concern in society about a certain security challenge (migration wave, military conflict, crime, etc.), then if the state does not engage in this area, it will open up space in this way for potentially problematic actors. On the contrary, if the state gets involved, even with a delay, it can reduce the operational space for such potentially problematic actors (see the example of Hungary).

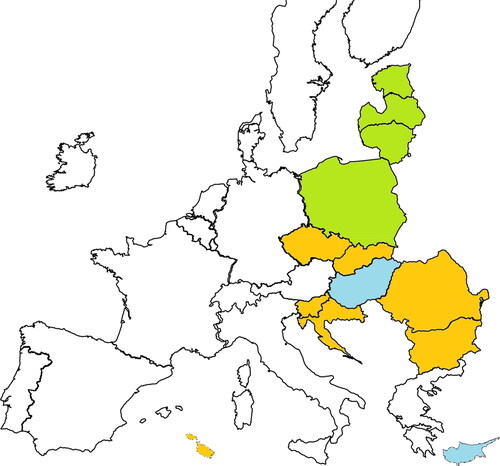

Regarding the structure and role of security volunteers in all 13 monitored countries, a number of similarities and differences can be assumed. Sometimes the differences are given historically, sometimes by natural conditions. Similarities are sometimes the result of the effort to imitate foreign models ().

Figure 2. Key area where security volunteers are involved: blue – internal security; green – military; orange – population protection, rescue etc. (own elaboration, with use of the blank map – the scale and location is modified in the case of Cyprus and Malta: Jones, Citation2009).

The individual related results and findings are then as follows:

In a number of countries, the primary volunteer alternative in the security area is population protection (fire rescue): Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Malta’s situation is specific, where rescue activities dominate, including the rescue of people at sea.

In addition, there is a group of countries where the dominant security-volunteer alternative is to enter official platforms linked to the country’s armed forces: Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland. It is no coincidence that these are countries on the eastern flank of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Not so dominant, but still unmissable volunteer alternatives in this area also exist in some other countries: the Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia. Note: In the case of Cyprus and Estonia, compulsory military service has not been abolished. In case of Lithuania, compulsory military service was reintroduced in 2015, and in Latvia in 2023.

In two cases, volunteer platforms or projects dedicated to ensuring local public order affairs completely dominate: Cyprus (there is even a competition between state-coordinated and independent neighbourhood watch patrols) and Hungary (robust base of civil guards). However, projects in this area also exist in Estonia and Slovakia. In Lithuania, Latvia and Polandm is also possible to use the capacities of primarily military-oriented volunteers for certain public order activities.

The trends in the monitored area relate more to volunteer structures linked to the armed forces – that is, the emphasis on greater capacities, which can be used in managing a complicated international security situation. If we follow the platforms described as vigilante, non-cooperating with the state, de facto paramilitary projects, they can be identified to a greater extent within Bulgaria and Slovenia, and to a relatively lesser extent also in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia. In all cases, these groups agree with the pro-Kremlin interpretation of the world. An interesting example is Hungary, where these associations were much stronger in the past (around 2006). However, state support for the creation of official volunteer structures took both members and part of the ‘ideological wind out of the sails’ of these projects.

In an attempt to sum results in relation to the primal hypothesis of the study (within the monitored states, especially within the states with a socialist tradition; i.e. outside of Malta and Cyprus; it is possible to trace significant similarities regarding their security systems), it must be stated that this aspect has been verified only to a limited extent – with regard to the post-Soviet Baltic republics – Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The four examples of countries where is a larger base of internal security related volunteers (Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary and Slovakia), are, however, practically unrelated. All these models developed in historically different environments, conditions – and on the basis of different motivations. At the same time, Cyprus and Hungary are countries where topics of internal security (in the case of Cyprus, at least on paper) completely dominate the volunteer sphere. In Estonia, however, the military area dominates, while in Slovakia dominates the population protection – and internal security issues are no more than additional agenda for volunteers.

The secondary hypothesis (in the absence of the state’s emphasis on security challenges, security-police volunteering can become a form of negative attitude towards the state) can be verified, at least in relation to some cases. At least the subjective feeling of threat was behind the birth of anti-immigration or other paramilitary organizations in some of the monitored states. These organizations define themselves towards their homeland (its representatives) usually in a non-cooperative, negativist manner. If the state ignores or does not address the topic of volunteering, regarding the local public order affairs, this agenda may become attractive for extremists and individuals or groups of individuals who would like to ‘take justice into own hands’. Some of these groups might be, moreover, explicitly geo-strategically oriented towards the Russian Federation.

5. Concluding remarks

The study aims to be a certain springboard, describing and comparing the situation in the new European Union Member States, regarding some aspects of the functioning of the internal security and local public order affairs systems. Existence of the broader security-police family and its anchoring in the official considerations of public institutions is prerequisite for the sustainability of publicly expected security standards, not only in the monitored countries.

As far as there are not many robust secondary sources in relation to that topic, let alone comprehensive theoretical concepts, all that remains is to create an own overview – using as many sources as possible, including non-academic periodicals, websites or social networks related to the topic.

To a very complete conclusion it is possible to state that the authors perceive the contribution both as a tool for other interested researchers, and as part of their own conceptual ambition, dedicated to the effort to create an ‘encyclopaedia’ dedicated to various approaches related to the ensuring of the local public order affairs in all individual European countries.

About the authors

The authors, working in AMBIS University, have long been devoted to the issue of local public order affairs, especially with regard to international comparison and the identification of best practice. In this regard, they tries to connect theory with practice, including the preparation of supportive documents for the Ministry of Defense of the Czech Republic, the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic and the Police of the Czech Republic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank AMBIS University, Prague, Czech Republic, for its support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Oldřich Krulík

Oldřich Krulík currently works within the AMBIS University and other educational, and research institutions in the Czech Republic, as well as in the Police of the Czech Republic. After graduating from political science at Charles University (2005), he achieved his habilitation in the field of security management and criminology at the Police Academy of the Czech Republic in Prague (2019). Between 2001 and 2009, he worked as an employee of the Security Policy Department of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, responsible for the preparation of strategic documents related to the fight against terrorism. Between 2010 and 2020, he was an academic worker at the Police Academy of the Czech Republic in Prague. He is author and co-author of several dozens of professional and popularizing articles and chapters in monographs, especially on the topics of serious security challenges.

Petr Klíma

Petr Klíma is a senior counsellor of the Crime Prevention Department of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic and is also employed as an external academic worker at AMBIS University. He graduated from the media and social communication program at Jan Ámos Komenský University (2009). Between 2014 and 2019, he was a senior counsellor of the Department of Security Research and Police Training of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic. He is an author and a co-author of professional and popular articles and conference contributions, especially on the topics of terrorism, internal security and crime prevention.

References

- Abipolitseinik. http://www.abipolitseinik.ee

- Aktivní záloha. https://aktivnizaloha.army.cz/

- Andrej Šiško želi Štajersko vardo predstaviti predsedniku Borutu Pahorju in jo ponuja vojski in policiji kot pomoč – pomožno silo za varovanje južne meje. (2019). Top News, September 26. https://1url.cz/KKBUT

- Ben-Ari, E., & Lomsky-Feder, E. (2011). Theoretical and comparative notes on reserve forces. Armed Forces and Society, 37(2), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X10396652

- Benčík, J. (2017). Kotlebova vlakobrana v praxi. Denník N, September 27. https://dennikn.sk/blog/892739/kotlebova-vlakobrana-v-praxi

- Bohman, M., & Krulík, O. (2009). Policejní sbory v zemích Evropské unie: Inspirace pro Českou republiku. Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky.

- Božek, F., & Tušer, I. (2021). Measures for ensuring sustainability during the current spreading of coronaviruses in the Czech Republic. Sustainability, 13(12), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126764

- Browne, B. (2016). Peyia neighbourhood watch a shadow of its original self. Cyprus Mail, November 20. https://1url.cz/NK3Vg

- Caless, B., & Tong, P. (2015). Leading policing in Europe book: An empirical study of strategic police leadership (pp. 165–22). Bristol University Press.

- Caparini, M., & Marenin, O. (2005). Crime, insecurity and police reform in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe. Reflections on Policing in Post-Communist Europe, (2). https://doi.org/10.4000/pipss.330

- Cheurprakobkit, P. (2002). Community policing: Training, definitions and policy implications. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25(4), 709–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510210450640

- Christián, L. (2017). Overview of law enforcement in Hungary, with special respect to local level law enforcement. Magyar Rendészet, 17(4), 143–155.

- Colvin, C. A., & Goh, A. (2006). Elements underlying community policing: Validation of the construct. Police Practice and Research, 7(1), 19–33. https://1url.cz/NKGcQ https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260600579599

- Comisia Locală de Ordine Publică. Politia Locala Focsani. https://politialocalafocsani.ro/comisia-locala-de-ordine-publica/

- Conscripts. Karys.lt. https://www.karys.lt/en/military-service/conscript-service/conscripts/400

- Cordner, G. (2000). Community policing – Elements and effects. In G. P. Alpert & A. R. Piquero (Eds.). Community policing – Contemporary readings (pp. 401–418). Waveland Press.

- Crawford, A. (2008). The pattern of policing in the United Kingdom: Policing beyond the police. In T. Newburn (Ed.), The handbook of policing (pp. 147–182). Willan.

- Crawford, A. (2005). Plural policing: The mixed economy of visible patrols in England and Wales. Policy Press.

- Crime Prevention Office. Cyprus police. https://1url.cz/yK3V0

- Dobrovoľná požiarna ochrana Slovenskej republiky. https://www.dposr.sk/

- Dobrovoľná vojenská príprava. Ozbrojené sily Slovenskej republiky. https://www.regrutacia.sk/113-sk/dobrovolna-vojenska-priprava/

- Dobrovoľní hasiči. http://dobrovolnihasici.sk/

- Emergency Response and Rescue Corps. Euroopa Liit. https://1url.cz/7kvau

- Emergency Response and Rescue Corps. https://www.errcmalta.com/about-us

- Fabac, R., Djalog, D., & Zebic, V. (2015). Organizing for emergencies – Issues in wildfire fighting in Croatia. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 13(1), 99–116. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/197347 https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.13.1.11

- Foster, J., & Jones, C. (2010). Nice to do’and essential: Improving neighbourhood policing in an English police force. Policing, 4(4), 395–402. https://1url.cz/mKa9X https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paq040

- Frič, P., & Pospíšilová, T. (2010). Vzory a hodnoty dobrovolnictví v české společnosti na 21. století. Praha: Agnes. http://www.dobrovolnik.cz/res/data/024/002868.pdf

- Garland, D. (2001). The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press. https://1url.cz/rz72V

- Gasilska zveza Slovenije. https://gasilec.net/

- Greene, J. R., & Mastrofski, P. D. (1988). Community policing: Rhetoric or reality. Prager Publishers.

- Национална асоциация на доброволците в Република България. https://navrb.bg/

- Hřebík, F., & Krulík, O. (2018). Mezinárodní konference “Nábor k policii v perspektivě změn”. Bezpečnostní Teorie a Praxe, 13(3), 139–140.

- In Poland, More than 13,000 Volunteers Signed Up for Voluntary Military Service. (2022). Ukrainian Military Center, August 29. https://mil.in.ua/en/news/in-poland-more-than-13-000-volunteers-signed-up-for-voluntary-military-service/

- Indians Attacked in Polish Border Town as Police Warn of “False Information” about Refugee Crimes. (2022). Notes from Poland, March 2. https://1url.cz/frVpu

- Jackova, A., & Nagyidaiova, M. (2022). Volunteers at the Polish-Belarusian border work in secret. Blok, January 20. https://1url.cz/Mr3BB

- Jaunsardze. https://www.jc.gov.lv/lv/jaunsardze

- Jones, B. (2009). Europe. Pinterest. https://cz.pinterest.com/pin/north-america-world-regions-printable-blank-map–587508713901281211/

- Jones, T. T., & Newburn, T. (Eds.). (2006). Plural policing: A comparative perspective. Routledge.

- Kaitseliit. http://www.kaitseliit.ee

- Kandrík, M. (2020). The challenge of paramilitarism in Central and Eastern Europe (Working Paper). German Marshall Fund of the United States. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26757

- Karlović, R., & Sučić, I. (2017). Security as the basis behind community policing: Croatia’s community policing approach. In S. Bayerl (Ed.). Community policing – A European perspective (pp. 125–138). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53396-4_10

- Keisk, R. (2019). Abipolitseinikud panustasid mullu turvalisusesse pea 100 000 töötundi. Politsei- ja Piirivalveamet, February 5. https://1url.cz/pKGc9

- Kotlebovci opäť spúšťajú hliadky. (2021). 24 hodín, June 21. https://1url.cz/Or3B4

- Krašto apsaugos savanorių pajėgos. Lietuvos Kariuomenė. https://www.kariuomene.lt/sausumos-pajegos/padaliniai/krasto-apsaugos-savanoriu-pajegos/22915

- Krédl, J. (2016). Obecní policie ve vybraných zemích postsovětského prostoru. Ochrana a Bezpečnost, 5(2), 1–76.

- Krulík, O. (2010). Dobrovolnictví v bezpečnostní oblasti: Příklad z Estonska. Bezpečnostní teorie a praxe, 6(1), 81–90.

- Krulík, O. (2014). Demografie a bezpečnostní sbory včera, dnes a zítra. Bezpečnostní teorie a praxe, 9(2), 123–132.

- Krulík, O. (2015a). Dobrovolnická uskupení v rámci ozbrojených sil pobaltských zemí. Ochrana a Bezpečnost, 4(1), 15.

- Krulík, O. (2015b). Obecní policie v Evropě slovem a obrazem. Bezvydavatele.

- Krulík, O. (2019). Kypr a místní záležitosti veřejného pořádku. Bezpečnost s profesionály, 9(1), 34–36.

- Krulík, O., & Bohman, M. (2012). Porovnání trendu vývoje kriminality v České republice se zahraničními trendy II.: Statistika kriminality v zemích Evropské unie. In A. Marešová (Ed.), Bezpečnostní situace v České republice. Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky.

- Krulík, O., Bukačová, B., & Krédl, J. (2022). Obecní policie a privatizace bezpečnosti v evropských zemích (2nd ed.). Aleš Čeněk.

- Krulík, O., & Krulíková, Z. (2014). Framework of business in private security: Bulgaria. Central European Journal on International and Security Studies, No. 3, pp. 48–69. https://1url.cz/bK3I3

- Krulík, O., & Linhart, M. (2013). Security system of Estonia. Ochrana a Bezpečnost, 2(2), 10.

- Kučera, M., & Mareš, M. (2011). Dobrovolné sdružování osob za účelem ochrany. Bezpečnostní teorie a praxe, 6(1), 95–110.

- Latvian National Guard – Zemessardze. Global security. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/lv-zemessardze.htm

- Latvijas Republikas Zemessardze. http://www.zs.mil.lv/lv

- Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga. https://www.sauliusajunga.lt/sauliai/

- Loader, I. (2000). Plural policing and democratic governance. Social & Legal Studies, 9(3), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/096466390000900301

- Loik, R. (2020). Volunteers in Estonia’s security sector. International Centre for Defence and Security.

- Magyar Önvédelmi Mozgalom. https://magyaronvedelem.hu/

- Malecký, R. (2019). Paramilitární Slovenští branci jako vzor české domobrany (2019). Hlídací pes, November 11. https://1url.cz/pr3BF

- Mandatory Conscription for Military Service Is Being Reinstated in Latvia. (2022). Ukrainian Military Center, September 7. https://mil.in.ua/en/news/mandatory-conscription-for-military-service-is-being-reinstated-in-latvia/

- Mareš, M. (2012). Paramilitarismus v České republice (pp. 123–196). Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury.

- Mareš, M., & Milo, D. (2019). Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities in Slovakia and in the Czech Republic. In T. Bjørgo & M. Mareš (Eds.). Vigilantism against migrants and minorities. Routledge.

- Mills, H., Silvestri, A., & Grimshaw, R. (2010). Police expenditure 1999–2009 (pp. 52). Hadley Trust – Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

- Na válku připraveni! (2015). Týden, March 7. https://www.tyden.cz/rubriky/domaci/na-valku-pripraveni-slovenska-domobrana-chce-pobocku-v-cr_335587.html

- National Guard Helping Police Enforce Lockdown. (2021). Public Broadcasting of Latvia, October 22. https://1url.cz/Rr3Bo

- Neighbourhood Watch. Cyprus mail. https://cyprus-mail.com/tag/neighbourhood-watch/

- Nočné havrany. (2017). Stará Turá. https://www.staratura.sk/item/nocne-havrany/

- Number of Volunteer Police Officers and Candidates Increasing. (2017). Eesti Rahvusringhääling News, April 17. https://1url.cz/TK3vy

- O’Neill, M., & Fyfe, N., R. (2017). Plural policing in Europe: Relationships and governance in contemporary security systems. Policing and Society, 27(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1220554

- Ochotnicza Straż Pożarna. https://osp.pl/

- Országos Polgárőr Szövetség. https://www.opsz.hu/

- Päästeliit – Estonian Volunteer Rescue Association. http://www.paasteliit.ee

- Pace, Y. (2016). Calls for preventive action against vigilante group soldiers of Odin. Malta Today, September 14. https://1url.cz/Dr3B2

- Pantovic, M. (2020). How violence and vigilantes are compounding the winter woes of migrants in the Balkans. Euronews, December 21. https://1url.cz/Br3Bj

- Pate, A. M., Wycoff, M. A., Skogan, W. G., & Sherman, L. W. (1986). Reducing fear of crime in Houston and Newark. Police Foundation – National Institute of Justice.

- Poland Launches Paid Voluntary Military Service. (2022). Notes from Poland, May 18. https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/05/18/poland-launches-paid-voluntary-military-service/

- Procter, R., Crump, J., Karstedt, S., Voss, A., & Cantijoch, M. (2013). Reading the riots: What were the police doing on Twitter? Policing and Society, 23(4), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2013.780223

- Projekt “Bezpečnostní dobrovolník”. Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky. https://www.mvcr.cz/clanek/projekt-bezpecnostni-dobrovolnik.aspx

- Republic of Cyprus Police Declare Neighbourhood Watch Schemes a Success! (2017). Neighbourhood Watch Queensland, May 9. https://1url.cz/sK3VS

- Romanian Army Plans to Hire 2,800 Voluntary Reserve Troops. (2017). Romania Insider, March 14. https://www.romania-insider.com/romanian-army-plans-hire-2800-voluntary-reserve-troops-year

- Romská hlídka vzbuzuje respekt. (2018). TV Nova, January 7. https://1url.cz/Lr3BG

- Rundesová, T. (2005). Čo sú to Nočné havrany. Hospodárske noviny, April 14. https://hnonline.sk/dennik/format/179961-co-su-to-nocne-havrany

- Self-Appointed Defenders of “Fortress Europe": Analysing Bulgarian Border Patrols. (2019). Belingcat, May 17. https://1url.cz/NK3Iv

- Servicii Voluntare/Private. Inspectoratul General pentru Situații de Urgență. https://www.igsu.ro/Comunitate/ServiciiVoluntarePrivate