Abstract

The dominant literature on performance of political parties seems to suggest that African parties are not agents of democracy. The article examines the performance of political parties in Ghana. A cross-sectional study was adopted based on a national sample survey across 10 administrative regions of Ghana. Data were collected from citizens of voting age based on the functional approach suggested in the literature. The article finds that Ghana’s political parties are effective in performing the following functions: mobilization of voters during elections, training national leaders, and formulating and implementing public education on government policies and programmes. The findings further indicate that political parties, especially the opposition parties, frequently perceived their role as potential governments-in-waiting. In this capacity, they ensure accountable governance by assuming a ‘watchdog’ role over the ruling administration. The article challenges the notion that political parties in Africa are generally weak in their functionalities, instead demonstrating that Ghana’s political parties have played a pivotal role in democratic development despite their limitations.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Political parties are viewed globally as essential to democracy and play an important role in every polity. The formation and activities of political parties are not only quintessential to the survival and sustenance of democracy but actually form the bedrock on which democracy resides (Matlosa & Shale, Citation2008). In fact, Krönke et al. (Citation2022) have argued that political parties are important elements in the quality of representative bureaucracy. Scholars have also argued that both horizontal and vertical accountability would be enhanced in countries where effective and responsible political parties exist (Osei, Citation2013; Wegner, Citation2018). Consistent with this view, Matlosa and Shale (Citation2008, p. 3) contend that ‘democracy is unthinkable without political parties’. This implies that political parties are indispensable agents in the promotion and consolidation of democracy. However, some other scholars have argued that it is possible to have political parties without a democracy (Agomor, Citation2019). Indeed, while prevalence of political parties is traditionally seen as the hallmark of democratic regimes (Bellinger, Citation2021), there are political parties in non-democracies in Eastern Europe (Gherghina & Fagan, Citation2021) and some countries in Africa (Donno, Citation2013).

While competitive, effective, and organizationally robust parties are widely acknowledged to positively influence democratic governance (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002; Krönke et al., Citation2022), African parties have not been accorded with such widespread appeal (Bob-Milliar, Citation2012; Owusu Kyei & Berckmoes, Citation2020). African parties are conventionally seen to be organizationally weak (Osei, Citation2013), with poor grassroots mobilisation and presence as well as lack of capacity to engage broader citizenry and to articulate their views and interests (Erdmann, Citation2004; Kuenzi & Lambright, Citation2011; Bjarnegård & Zetterberg, Citation2019; Amoako Addae, Citation2021). The existing literature has further maintained that political parties in Africa have undermined democratic governance ‘through the irresponsible and self-interested actions of their leaders’ (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002, p. 32). While their campaign promises are often inundated with vague promises of fighting corruption and a better future for all, these programmatic appeals are mere populism (Blaxland, Citation2023) and ditched the urgent call to mobilise citizens along substantiative issues of development (Osei, Citation2013). Hence, scholars have questioned the possible contribution of political parties in Africa due to these weaknesses.

Despite a very checkered political history, Ghana’s Fourth Republic has so far performed relatively better, surviving through eight election cycles. The keenly contested 2016 elections resulted in the third democratic and peaceful transfer of power since the advent of the Fourth Republican Constitution in 1992. Indeed, Ghanaians have made concerted efforts to not only embark on democratization process but also democratic consolidation and maturity after the ‘third wave’ (Abdulai & Sackeyfio, Citation2022). Though political parties are objects of massive supports in Ghana, nevertheless, questions have been raised about the ways in which parties operate in practice (Bob-Milliar, Citation2012), particularly after successfully capturing power and forming the government. For instance, the recent report from the Afrobarometer survey shows that 87% of Ghanaians expressed the view that the country was heading in wrong direction (Afrobarometer, Citation2022). There is a critical question with respect to why Africans show massive support for democracy but feel discontented with the performance of elected governments.

Extant literature on democracy, democratic consolidation, and elections examines Ghana’s democratic transition (e.g. Abdulai & Crawford, Citation2010) and the performance of political parties in elections (Osei, Citation2013). Scholars also shed light on ethnicity and voting behavior (Adams & Agomor, Citation2015), political party financing (Nam-Katoti et al., Citation2011), the role of civil society and state institutions (Botchway, Citation2018), and understanding political party duopoly in Ghana (Daddieh & Bob-Milliar, Citation2014; Agomor, Citation2019). However, it is surprising why there is little focus on what political parties actually do when in government. Moreso, the possible contribution of political parties has been questioned due to their relative weakness. Therefore, this article aims to fill this gap by examining the activities and contributions of political parties, especially in the post-election periods, hence, advancing the scholarly discourse on the role and effectiveness of political parties in democratic governance. The assessment was thematically hinged on functional approach to the performance of political parties: mobilization of support for elections, provision of alternative government, provision of leadership, provision of policy alternatives, public education, shaping the political will of the people, and formation of government. Clearly, the aforementioned points for performance assessment transcends the usual electoral duties often expected of political parties. Perceptions of citizens were analyzed by the researchers to descriptively substantiate the claims herein made. Indeed, a second look at these seven thematic points portray known and expected functions of political parties, the point of departure in this study is to descriptively examine the perceptions of citizens with respect to the level at which political parties in Ghana perform the seven enumerated functions. The article proceeds as follows: the literature is discussed, the methodology is presented, and the analysis, discussion, conclusion and policy implications are subsequently offered.

Literature review

Theoretical perspective: Functional approach

The notion that political parties are critical for democracy-promotion has continually been the preoccupation of scholars (Gauja & Kosiara-Pedersen, Citation2021). Varied views have been proposed by scholars regarding how to conceptualize the functions of political parties (Almond & Powell, Citation1966; Sartori, Citation2005). Based on the functional approach, Diamond and Gunther (Citation2001, p. 7,8) provide seven functions performed by political parties: candidate nomination (select and prepare potential political leaders or candidates); electoral mobilization (mobilize and allow citizens to participate effectively in the political process); issue structuring and policy formulation (formulate and implement public policies); societal representation (represent and advance the interest of society); interest aggregation (aggregate individual interests into broader appeals); forming and sustaining the government (capture power to execute their policies); and societal integration (harmonize and incorporate diverse views of the society).

By policy formulation and issue structuring, political parties structure the choices and alternatives of electorate along different issue dimensions; by societal representation and interest aggregation, parties are supposed to represent the diverse interests of the people. This takes place in the legislative space and parties do this by ensuring that the needs and aspirations are clearly articulated and factored into the policy stream of the government. Furthermore, parties play the function of electoral mobilization and social integration by motivating the electorate to support their candidates and policies as well as facilitate their active participation in the political process. Additionally, candidate nomination and forming the government or opposition are crucial functions for political parties. Parties recruit candidates with the aim of winning elections and forming the government. When not in government, parties play a vital role in maintaining accountable checks on the ruling government by acting as the opposition (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002; Manning, Citation2005; Johnston Citation2005; Kelly & Ashiagbor, Citation2011).

Conversely, Bartolini and Mair (Citation2001) enumerate five roles played by political parties including citizen consolidation and integration, creation of public policy, selection of political leaders and integration of parliament and government, expression and unification of interests. Some other scholars contend that political parties engage in agenda setting through ideology and programme, interest articulation and aggregation, mobilization and socialization, elite recruitment and government formation (Von Beyme, Citation1982, p. 25). Moreover, Dalton and Wattenberg (Citation2000, p. 5) put forward that political parties also mobilise and educate voters, ensure accountable governance, aggregate and articulate political interests as well as create majorities in governments and implement policy objectives. For Bartolini and Mair (Citation2001, p. 332), the functions of political parties should be categorized under representative, procedural and institutional functions.

Functions of political parties: the empirical evidence

The performance of political parties has generically and country-specifically been assessed by scholars using various scales or models for such appraisal. Although appreciable number of scholarly works concentrate on the functions of political parties in a state, arguably, not so many works have weighed the performance of such functions by parties in exactitude. The ensuing paragraphs reviews extant literature that have expounded the functions and performance of political parties. With respect to electoral mobilization, scholars have argued that political parties are the main agents of mobilizing people for participation in a democratic system (Fobih, Citation2011). Consistent with this view, parties are widely seen as the health and soul of a democracy (Karp & Banducci, Citation2007). Smith particularly contends that political parties are the most critical institutions of political mobilization in the context of mass parties. Thus, parties can help facilitate participation in the political process by encouraging citizens to become engaged in the political process. As primary instruments of political socialization, Saikkonen (Citation2017) argues that the role of political parties is particularly important for emerging democracies. Particularly, in democracies where partisan attachment is weak and elections may lack legitimacy, parties may need to exert greater efforts in getting potential supporters to the polls (Dalton & Weldon, Citation2007).

Moreover, political parties are often regarded as the primary entities responsible for ensuring accountable governance. Thus, political parties are regarded as powerful instruments and institutions of democracy because of the ability to hold the government accountable, particularly when in opposition. (Asunka, Citation2016). Schedler et al. (Citation1999) assert that political accountability is an important indicator of democratic quality. Political parties are key enablers of horizontal accountability as office incumbents can be voted out of office and replaced by an opposition party due to abuse of power (Laebens & Lührmann, Citation2021). Thus, the exercise of political rights in free and fair elections, along with competition between parties in multi-party elections and intra-party contests, can lead to accountable governance by replacing corrupt officeholders through the electoral process of political parties’ candidate selection (Laebens & Lührmann, Citation2021). Moreover, the presence of strong opposition legislatures in parliament may ensure effective oversight by scrutinising every action of the incumbents. Thus, political parties provide a strong countervailing force to the political party in government. It is predominantly within the remit of opposition that political parties stand to offer an alternative force or check to the incumbent party such that electorates can rely on opposition to ensure the wheels of state administration run on a fair course. Besides the administrative functions or government business chiefly handled by the political party in the majority caucus, the political parties that form the minority arguably become the voice (of the people) that champion effective and balanced pursuits of economic and social policies. Consistent with this view, Kelly and Ashiagbor (Citation2011, p. 3) argue that ‘when in the majority, parties provide an organizational base for forming government, and when in the minority, a viable opposition, or alternate to government’.

Additionally, political parties are important actors in public policy formulation and implementation process (Slothuus & Bisgaard, Citation2021). Fobih (Citation2011) particularly argues that political parties contribute effectively towards shaping public policy by generating reliable information for the public. Parties tend to control public policymaking in the state through party manifestoes presented to voters during elections (Arkorful & Lugu, Citation2022). Thus, political parties ascend to power by making campaign promises based on their party ideologies and these promises become the reference point after winning elections. However, Randall and Svåsand (Citation2002) argue that political parties in Africa care little about presenting clearly distinguishable policy platforms.

In fulfilling the role of providing education and sensitizing the citizenry on governments’ policies and programmes, political parties have the responsibility to organize and offer education to their members as well as the general public on their activities, government policies, and the entire electoral process (Bladh, Citation2022). As parties commit to sensitizing the public, its internal and external capacities to act, react, and interact in relation to the dynamics of the democratic system are enhanced. Morrison (Citation2004) argues that political parties provide political socialization by offering credible information that enables citizens to make informed choices. Parties usually achieve this by building an identity through ideas presented in manifestos and cadre-led campaigns (Bob-Milliar, Citation2019). Consequently, Morrison (Citation2004) asserts that parties often use manifestos to transmit their views to society. Thus, television, radio and in recent time social media handles have been major vehicles of public education and electioneering.

Additionally, political parties are representatives of the interest of social groups and the advancement of some peculiar interests (Diamond & Gunther, Citation2001). Diamond and Gunther further assert that political parties aggregate the interests of individual groups into broader appeals. As political parties articulate and integrate varied interests, visions, and opinions, citizen engagement is mobilized in the political process with the ultimate goal of winning political edge and be able to influence government policy (Asunka, Citation2016). Almond and Powell (Citation1969, p. 433) have argued that political parties ‘mobilize voters, package and transmit demands, guide the policy option process, and form broad alignments – cross-cutting cleavages, pacts, coalitions, and mergers’. The rationale is that citizens hold diverse values and preferences that they wish to have them addressed by policymakers. Indeed, Cross and Young (Citation2004) affirmed that political parties are responsible for aggregating citizen interests and articulating them in the political sphere. The function of aggregation of interests and representation captures deliberations, compromises, and negotiations to reach a consensus in multi-party agreement (Bladh, Citation2022).

Almond et al. (Citation1996) have argued that political recruitment is one of the defining functions of political parties. In both presidential and parliamentary systems across the world, political parties are responsible for selecting candidates through internal party structures to occupy public office (Daddieh & Bob-Milliar, Citation2012). Candidate selection is the key stage in the recruitment process of political parties. Dodsworth et al. (Citation2022) contend that candidates’ selection also represents one of the key linkages between the electorate and the policy-making process. After undergoing internal elections to select candidates, political parties contest at various levels to win general elections in order to form the government (Rahat & Cross Citation2018). Therefore, political parties are not only the vehicles for selecting national leaders but also form and sustain the government.

Randall and Svåsand (Citation2002) expound the performance of political parties in Africa in light of democratic consolidation. Whilst the double-pronged approach of assessing both gains and shortfalls of political parties by the scholars is commendable, several critical issues remain unaddressed. Without questioning the methodology adopted by Randall and Svåsand (Citation2002) in selecting political parties in African countries for assessment, one could easily observe some gross limitation regarding the presentation of factual or verifiable data and the advances they put forth. For example, they claim that although it is the function of political parties to recruit leaders in democracies, electoral candidates in Africa ‘are elected on a party label’ yet ‘they are not necessarily ‘recruited’ by these parties’ (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002, pp. 33,34). The cases of governing parties in Tanzania, South Africa, Zambia and Kenya are merely cited to buttress their aforementioned assertion without recourse to periodization. Far from vilifying the work of Randall and Svåsand, Citation2002, it is, however, clear that until some amount of quantitative or experimental data is presented, such assertions, no matter how factual, could still remain presumptuous or speculative. With this cue taken, this work sets out Ghana’s Fourth Republic as case study to rightfully assess the performance of political parties; offering empirical data to substantiate the claims made.

Within the discourse of electoral democracy, the likes of Wanyande (Citation1998), Diamond (Citation2005), and Thompson (2010) have explored how ‘party systems’ affect national unity, national development, amongst other variables. Indeed, the study by Thompson (2010) resonates with Wanyande (Citation1998) in advancing that a multi-party system is alien to Africa’s ethnic heterogeneity and could create tensions in Africa’s political atmosphere. Diamond (Citation2005), however, disassociates from this view and avers that a multi-party system in Africa is rather ideal for free and fair elections, potent enough to ensure national cohesion. Congruently, Agomor (Citation2015) affirms that multi-party systems are much heralded and pivotal to the thriving of democracy. The point of convergence between ‘party system’ and democracy is further beheld in Beetham’s description of democracy – ‘system of collectively binding decision-making, as spelt out in law, to the extent that it embodies principles, and specific institutions or practices that enable the entity (political party) or system (society) to realize them’ (Beetham, Citation1994, p. 159). On these synergistic premises (between party system, political parties and democracy), this work stretches beyond ‘party system’ to unpack how political parties in the Fourth Republic have effectively formed legitimate governments, consequently meeting the economic and social needs of the Ghanaians.

Asekere (Citation2019) is one of the recent academic research works conducted on the performance of political parties in Ghana. The author presents a rather simple and coherent means of assessing political party performance, as he contextualized performance as ‘the degree to which a party does well or wins in competitive multi-party elections’ (Asekere, Citation2019, p. 17). Undoubtedly, this scheme of weighing Ghana’s political parties’ performance solely on the beams of elections renders an overly narrow and shallow perspective. If political parties are merely examined based on votes amassed during elections, it suffices to question how other functions like information dissemination, political socialization, inter alia spelt out in Section 1(3) of the Political Parties ACT, 2000 (ACT 574) should be measured? Although Asekere (Citation2019) proceed to measure party performance on two main levels; internally and externally, there arguably remains an inadvertent attempt to relegate the functions of political parties to ‘political marketing’. By internally measuring party performance, he basically uses representation, accountability and equality as indicators. More so, the number of votes accrued by a political party (as external level) to supplement the internal indicators in gauging the performance of the NPP and the NDC. Clearly, Asekere’s (Citation2019) approach is bedeviled with a number of limitations (beyond adequacy and generalizability), which this work would offer some cushioning and coverage.

Since ‘Ghana’s current constitutional democratic dispensation is modelled on the 1992 constitution which promotes a multi-party competitive system’ (Aning, Citation2013, p. 9), this work inculcates all registered parties (not just NPP and NDC) in measuring party performance in Ghana since the inception of the Fourth Republic. In addition, in order to add on to this work and other extant literature, this work derives seven key points or models exhaustive enough in measuring the performance of political parties. Unlike Asekere (Citation2019) who utilizes three constituencies out of the 275 constituencies in Ghana, this work would present data findings from a broad national perspective, adopting systematic means to make claims scientifically generalizable.

African parties and democratic development

There exists a strong indication within the corpus of African politics that political parties in Africa struggle and linger at efforts towards democratic consolidation (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002; Carothers, Citation2006). The actions and performance of political parties within the region have often been considered a deviation from the ideal and effective role played by parties in advanced democracies. Effective parties are supposed to have a strong central organization, be internally democratic, have a well-defined membership base and cooperative relations with civil society organizations, have clear ideologies, transparent, and possess adequate funding stream (Carothers, Citation2006, p. 98). Gleaning from a recent study by Fanso (Citation2023), it is evident that the presence of heterogenous ethnicities in Africa, which have not yet been contextually reconciled with the practice of party politics, significantly accounts for the ineffective nature of political party functions (mostly in post-election phases) since the era of independence. Indeed, parties in Africa have long been known to have a weak link in a laundry list of items that constitute democratic consolidation, often appearing to thwart the efforts toward democratic maturity (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002). Conversely, De Walle and Butler (Citation1999) assert that parties in Africa are weak in terms of organizational structure, low level of institutionalization, and have weak links to the society whose interests they are supposed to represent and aggregate.

Furthermore, the argument that African-oriented parties perform the function of interest aggregation cannot be substantiated. For instance, De Walle and Butler (Citation1999) contend that parties only serve a representative role in the context of clientelistic and patrimonial political culture. Chabal and Daloz (Citation1998, p. 39) shared a similar sentiment and argue that people do not vote because they support the ideas, even less, read the programmes, of a particular party, but do so because they must placate the demands of their existing putative patron. According to Van de Walle (Citation2003), parties are used as a veneer reinforced by clientelism and patronage politics to feed the parochial interest of the political elite – where material gains are confined to the elites whose appeal are undergirds by shared ethnicity.

Another area of contention in the literature of party politics in Africa stresses the lack of ideological competition and the aggregation of societal interests. As Randall and Svåsand (Citation2002, p. 3) point out, parties care little about presenting clearly distinguishable policy platforms, and even when such platforms are presented, they often have little relevance to the party’s actions once in office. This assertion clearly indicates that the actual roles and actions of parties in Africa when they form government remain unclear. At best, campaign platforms are inundated by personality issues, claims and counter-claims as to the merits of policy positions – which are distant from the interest aggregation (Randall & Svåsand, Citation2002). Young (Citation1993) shared the same sentiment and adds that electoral discourse is limited to vague slogans of change and opposition to the incumbent. Thus, change is one of the most common promises, and in many cases, the only one – depicting their lust for power. Even when parties are in opposition, feasible policy alternatives are not typically offered as may be expected (Bauer & Taylor, Citation2005). In some cases, the opposition parties are typically small and highly fragmented. Parties have also proven very weak (Olukoshi, Citation1998) when it comes to reaching out to people in the rural areas where the majority of the population are concentrated.

In this article, four out of seven functions proposed by Diamond and Gunther (Citation2001) and Bartolini and Mair (Citation2001) were employed as a framework to analyse the performance of political parties in Ghana. These include electoral mobilization, policy formulation and issue structuring, representation and interest aggregation, and candidate selection and forming the government. These functions were employed because they are most widely observed functions often performed by political parties in developing countries (Osei, Citation2013). Besides, Dalton and Wattenberg’s (Citation2000) functionality approach suggests that political parties provide public education, transformational leadership, and ensure accountable governance. These elements were employed as the framework and applied to examine from the perspectives of voters or citizens the role of political parties in Ghana.

Research methodology

The study is a cross-sectional study based on a national sample survey. Primary data collection involved questionnaire administration on 3450 voters age from the 10 out of 16 regions in Ghana. A multi-stage cluster sampling techniques was used. The first stage involves a combination of probability and non-probability sampling techniques to select the regions. First, purposive sampling technique was used to select the national capitals of the regions. Second, the cluster sampling was used to group the 16 regions into 4 clusters of four regions each. In all, 10 regions were purposively selected and used for the analysis. The regions selected represented the original regions before 6 new regions were created in 2019. The regional capitals of the original ten regions were cosmopolitan in nature and captures the views of citizens in the newly created regions. Moreso, a constituency in each regional capital of all the 10 regions was purposively selected because it is the microcosm of the region and form part of urban population of the sample. Additional two constituencies outside the regional capital were selected using stratified (urban and rural) sampling technique. In all, 33 out of 275 constituencies were selected.

In each of the selected constituency, an equal number of respondents was selected from rural and urban areas in proportion to regional votes cast in 2020 presidential election. The primary sampling unit which is the household was selected by a random walk with specific interval of three and five for rural and urban areas, respectively. Where there was no eligible respondent, the research assistants were asked to move to the next household to replace the original selected household. Where there was more than one eligible respondent in a household, a Kish grid was used to select one respondent from each household. Building on the sample for prior national studies where the Centre for Democratic Development in Ghana (CDD-Ghana) (2005) selected 600 household heads, Lindberg and Morrison (Citation2008) used 690 voters and Adams and Agomor (Citation2015) used 2042 respondents, this study considers 3450 respondents as appropriate. The use of such large sample size has some inherent benefits. Thus, large sample size does not only ensure better representation of the population but also provides stronger, reliable, and accurate results (Andrade, Citation2020). Large sample size also reduces the margin of error and guarantees lower standard of deviations in statistical analysis (Bacchetti et al., Citation2005). In that regard, Biau et al. (Citation2008) have argued that large sample size provides better precision of results, high statistical power, and reduces false positive and negative findings in hypotheses testing. In contrast, Naing et al. (Citation2006) conclude that small sample size tends to be associated with weak statistical power and produces false positive and false negative results leading to type 1 and type 2 errors respectively.

The survey questionnaire contains items that were drafted in accordance with Diamond and Gunther (Citation2001), Bartolini and Mair (Citation2001), Von Beyme (Citation1982) and Dalton and Wattenberg (Citation2000) functionality approach to the study of the functions of political parties. These include electoral mobilization, policy formation and issue structuring, candidate selection and forming the government, public education, transformational leadership, and shape the political will or political consciousness of voters or citizens. These elements were employed because scholars, including Osei (Citation2013), have argued that the functions observed are widely performed by political parties in developing countries. Respondents were asked ‘on the scale of 1 (Least effective) to 6 (Most effective) rate how effective political parties have performed the functions of ‘electoral mobilization’, ‘policy formulation and issue structuring’, ‘candidates’ selection and forming the government’, ‘public education’, ‘providing transformational leadership’, and ‘ensure accountability and alternative government’ and ‘representation and interest aggregation’. To achieve clarity in the responses, the scale was defined and adequately explained to the respondents during data collection. Thus, as their responses move closer to 6 on scale, they were asserting that political parties were ‘Most’ effective in discharging their functions. Thus, 1 (null or neutral), 2 (Least effective), 3 (Less effective), 4 (Averagely effective), 5 (More effective) and 6 (Most effective). This detailed information enhanced the respondents’ understanding and clarified ambiguities often associated with scale-type questionnaire items. below shows the regional distribution of respondents.

Table 1. Regional distribution of respondents.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics was employed to examine the perceptions of citizens with respect to the performance of political parties in Ghana. Descriptive statistics allowed the presentation of the results in percentages and frequencies, which helped in the analysis, discussion and conclusion of the findings.

Findings and discussion

This section presents the findings and discussion. The performance of political parties in Ghana was assessed based on the key elements suggested in the literature. These include electoral mobilization, policy formation and issue structuring, candidate selection and forming the government, public education, transformational leadership, ensure accountability and alternative government, and representation and interest aggregation. below presents the results illustrating the performance of political parties in Ghana.

Table 2. Best performed functions of political parties.

Electoral mobilization

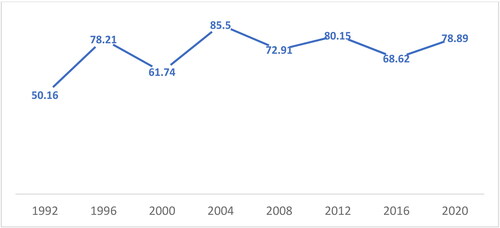

With respect the political parties’ ability to electorally mobilized voters, the data garnered from the field revealed that 41% majority of the respondents rated Ghana’s political parties as being active in the mobilization of voters for elections. Thus, since the ban on political activities in Ghana was lifted in 1991, there has been fierce competition between the NDC and NPP over the control of voters in Ghana’s Fourth Republic ().

Table 3. Electoral mobilization function.

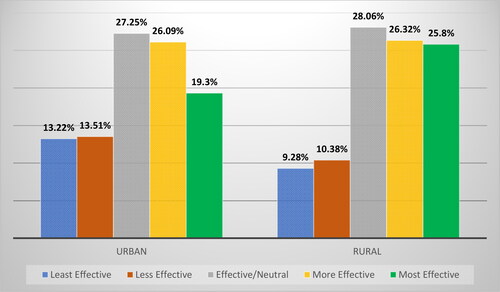

Therefore, the electoral mobilization function performed by political parties in Ghana has been successful as the voter turnouts in the general election shows consistent rise since Ghana returned to the democratic rule in 1992 (). Furthermore, the data were disaggregated to examine electoral mobilization capacity of political parties through rural-urban lenses. Interestingly, the results show some variations with respect to the ability of political parties to mobilize urban and rural voters during elections. Thus, while 17% of urban respondents gave an average effectiveness rating to the ‘mobilization function’ of political parties, 18% majority of rural respondents did indicate that political parties are active in their electoral mobilization function. Thus, a majority of the rural participants (707 of respondents) rated political parties to be most effective in their electoral mobilization function whereas 696 respondents from the urban areas endorsed that political parties are active in electoral mobilization.

In fact, previous studies have led evidence to show that political parties in Ghana adopt varied forms of voter mobilization strategies. Thus, while the two major political parties (NDC and NPP) take advantage of the media pluralism and sell their policies and programmes to the people in the urban areas, strategies such as house-to-house campaigns are key instruments for the mobilization of voters at the rural areas, and these were usually accompanied with gifts, such as money, rice, salts, soap and other consumables. The use of patronage goods in rural areas as electoral mobilization strategy may account for why most respondents view parties as active in voter mobilization drive. Given these data variations and the lack of a significant majority, it suffices to posit that Ghanaians are yet to appreciate the ‘mobilization of election support’ functionality of political parties in full measure since the Fourth Republic.

Ensuring accountability and alternative government

The finding shows that 954 majority representing 27% of the respondents expressed the view that political parties are averagely effective in discharging the function of ensuring accountable governance and providing an alternative government to the government of the day.

The findings (as per above) further suggest that a near majority of 904 representing 26% of the respondents also assert that political parties in Ghana are more effective not only in serving as alternative government but also hold the government of the day accountable. Thus, power was handed-over to NPP government in after 2000 general elections. However, the NDC took over the reign of governance after 2008 general elections for 8 years until 2016 general elections when power alternated to the NPP government again. Clearly, both the NDC and NPP have distinguished themselves as credible opposition and often serve as alternative government to the ruling coalition. In that regard, the data gathered depicted that there was a statistical relationship between respondents who voted to either change or maintain government in the 2020 elections and their rating for effective alternative government formation by political parties. The researchers realized that the highest plurality of people who voted for change in government were of the notion that political parties have averagely performed their role in forming alternative governments. While that remains, the highest plurality of people who voted for government to be maintained, deemed political parties to have effectively provided alternative governments over the years.

Table 4. Accountability and providing alternative government function.

below sunders out responses from rural-urban perspectives and finds (amongst other notable variance or similarity) that, the rural residents hold the view that over the years, alternative governments have ‘more and most’ effectively been formed by political parties in Ghana, with a cumulative score of 7% greater than the rating of the urbanites.

Policy formulation and issue structuring

Examining the policy formulation function of political parties, the findings (see ) show that 28% representing 994 majority of the respondents expressed the view that political parties in Ghana are most effective in policy formulation and issue structuring.

Table 5. Policy formulation and issue structuring.

From the ideological standpoint in Ghana, the NDC prides itself as social democrats, which is more inclined to a collectivist approach to public policy and socially friendly policies and interventions. While the NPP on the other hand, is a pro-conservative liberal democratic party that prioritizes market-oriented policies (Osei, Citation2013). Thus, whereas the NDC social democrats’ orientation suggests that their policies gear towards poor and vulnerable groups, the NPP’s would naturally be concerned about implementing policies that would support economic liberalism, market economy, and individual freedoms. In this Fourth Republic, however, the NPP has initiated and implemented social protection policies, which in most cases, have been continued and expanded by the NDC (Alidu et al., Citation2016), thereby obscuring the ideological line between the two parties. These policies include National Health Insurance Scheme, school feeding programme, capitation grant, and the flagship livelihood empowerment against poverty have been implemented under the NPP administration, which have been scaled-up by pro-socialist NDC government (Grebe, Citation2015).

Public education

The questions posed sought to ascertain the citizens’ view on how well they are informed on electioneering processes, before and during election, through to appraising their knowledge on government businesses and policy choices in post-election periods ().

Table 6. Public education function.

The findings show that a majority of the respondents (950) and (890) representing 27% and 25% expressed the view that political parties in Ghana are more effective and most effective in performing the function of educating the public on government policies, programmes, and electoral processes. However, a relatively few respondents (372) representing only 10% of the respondents hold the view that political parties are least effective in educating and sensitizing the public on the government policies and electoral activities. This result is particularly true because independent bodies such as the Electoral Commission and National Commission for Civic Education are cash-strapped and unable to effectively discharge their mandate of educating the public on government policies as well as electoral processes. In that regard, political parties in Ghana’s Fourth Republic have been active in both election and inter-election periods in educating voters on what their respective parties have done while in government.

Representation and interest aggregation

To investigate representation and interest aggregation function of political parties in Ghana, the findings show that 967 majority of respondents constituting 28% expressed the view that political parties are more effective in their function of representation and interest aggregation. Moreover, a near majority of 869 and 694 of the respondents representing 25% and 20%, respectively, hold the view that political parties are averagely effective and most effective in their function of representation and interest aggregation ().

Table 7. Representation and interest aggregation.

It should be noted that the electoral mobilization strategy, ideology, and policy pursuits of political parties directly or indirectly influence the opinions formed by electorates. The will of the populace are largely subjected to political parties’ influence when political, social and economic perspectives are built to run on the potent machinery of campaigns and manifesto propagation (Morrison, Citation2004). Admittedly, the political will of the Ghanaian voter is likely hinged on ethnic affinity, presidential candidature, rational choice, policy direction, amongst others. Indeed, the voter preference of party members who esteem ‘ethnic affinity’ are not easily swayed by the message of other political parties: typically, the Ashanti’s are inclined to the NPP, whilst the Ewes are mainly inclined to the NDC (Gyimah-Boadi and Asante, Citation2006).

Candidate selection, forming and sustaining governments

To interrogate the extent to which political parties in Ghana perform the function of selecting candidates, form and sustain national governments, 1119 representing 32% majority of the respondents expressed the view that political parties are most effective in selecting candidates to form and sustain the government. However, 605 of the respondents representing 17.5% of the respondents hold the view that political parties in Ghana are ‘less and least’ effective in forming and sustaining governments ().

Table 8. Candidate selection and forming and sustaining government.

Discussion

The performance of political parties in Ghana was assessed based on the functional approach developed by Diamond and Gunther (Citation2001), Von Beyme (Citation1982), Dalton and Wattenberg (Citation2000). The article finds that Ghana’s political parties are active in the mobilization of voters during elections. As part of the strategies for voter mobilization, there is evidence that constituency level executives and Members of Parliament (MPs) adopt strategies such as payment of hospital bills, payment of schools’ fees, provision of farm implements to farmers, organization of football matches for the youth, and many more, just to foster goodwill and ensure closeness of their parties to the people (Brierley & Kramon, Citation2020). They also attend formal and informal gatherings to promote their party’s ideology, combine card-bearing and fee-paying membership as party sustainability strategies. According to Fobih (Citation2011), political parties use common strategies including organizing rallies and community outreach programmes to recruit members. Though these approaches could be successful in voter mobilization, it raises questions of vote-buying, clientelist and patrimonialistic type of politics in Ghana, which has the potential to undermine efforts at democratic consolidation (Abdulai & Crawford, Citation2010). The net effect is that people would become mere consumers of politics rather than being actors in the democratization process. Moreover, strong electoral mobilization function played by the Ghanaian political parties reflects in high voter turnouts which has consistently exceeded 60% by the international standards (Bob-Milliar, Citation2012). Local politicians also take advantage of societal gatherings like funerals, religious programmes, weddings and naming ceremonies, festivals, and others to launch support for their respective parties (Ichino & Nathan, Citation2013).

Moreover, the findings indicate that a majority of respondents expressed the view that political parties in Ghana are effective in ensuring accountable governance. This finding is consistent with recent literature that revealed that political parties are key to ensure both horizontal and vertical accountability (Osei, Citation2013; Wegner, Citation2018; Laebens & Lührmann, Citation2021). Elections is an important mechanism for ensuring vertical accountability and it provides citizens the opportunity to hold politicians accountable for their stewardship. Ghana has successfully held eight elections in the Fourth Republic with power alternated between the NDC and NPP. This implies that electoral competition among political parties serves as a form of accountability in Ghana since Ghanaians tend to use election as the basis to hold politicians accountable (Fobih, Citation2011). The findings indicate that political parties, especially the opposition factions, often seen as potential governments-in-waiting, contribute to ensuring accountable governance by adopting a ‘watchdog’ role over the ruling government. Furthermore, the findings suggest that political parties in Ghana are effective at formulation and implementation of policies. This is in line with the existing scholarship (Fobih, Citation2011; Slothuus & Bisgaard, Citation2021). In fact, political parties control public policy making space through party manifestoes presented to voters during elections (Arkorful & Lugu, Citation2022). With respect to public education, the findings suggests that parties are active in sensitizing and providing education on electoral processes as well as government’s policies and programmes. This is consistent with the argument that political parties have the responsibility to organize and offer education to their members as well as the general public on their activities, government policies, and the entire electoral process (Bladh, Citation2022). Diamond and Gunther (Citation2001) argue that political parties aggregate the interests of individual groups into broader appeals. Asunka (Citation2016) also argue that political parties articulate and integrate varied interests, visions, and opinions, citizen engagement is mobilized in the political process with the ultimate goal of winning political capital and be able to influence government policy.

Conclusion and recommendations

The performance of political parties in Ghana’s Forth Republic has come under new scrutiny. The populace in new democracies such as Ghana perceive political parties as integral aspects of democracy. However, the performance of the political parties, especially in mobilizing, educating and recruiting the populace outside the election season does not meet the expectations of the populace even though, in the context of Ghana, the people continuously give them a chance to rule periodically. There is therefore the need for political parties to develop their core ideological foundation and base so as to attract people with similar ideological disposition. Political parties should also enhance their mobilization and recruitment processes in order to make party engagements attractive to citizens. Even though majority of the citizens (61%) believe that viable governments have been formed by political parties in Ghana’s Fourth Republic, about 21% are indifferent on this subject. This, therefore, shows that the level of apathy or disinterest on the viability of political parties is high. Besides political parties pursuit of winning elections, other identified roles expected of political parties must be equally prioritized and operationalized. It remains imperative for political parties to uphold transparency and accountability in their operations to foster trust among the populace. Enhancing internal democracy, promoting inclusivity, and actively involving marginalized communities are crucial measures to bolster the legitimacy and efficacy of political parties in Ghana’s Fourth Republic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joseph Kofi Agyapong Darmoe

Joseph Kofi Agyapong Darmoe is a strategic management, organization theory and change management specialist as well as a local government, technology-society expert. Darmoe, a lecturer at the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration, until recently served as the Director of Research at the Ministry of Inner City and Zongo Development, Republic of Ghana. He is also a member of the American Society of Public Administration (ASPA) and a recipient of the 2014 International Young Scholars Fellowship. As a research scholar, he has published several journal articles, book chapters and manuscripts for internationally recognized journals and outlets as well as serving as an editor for the Journal of International Higher Education Management. His seminal work; Branding at the base of the Pyramid looks at how organizations and nations in developing markets can create a unique niche and identity in spite of the numerous challenges posed by the macro environment of business. To highlight the problems in leadership in African organizations and to encourage organization preparedness for brain gain, Darmoe in ‘The Professor Coming Home: Brain gain in SSA HEI’ through empirical observations develops a model for organizations and HEI’s that will facilitate in managing brain gain knowledge workers.

Kingsley Agomor

Kingsley S. Agomor is an associate professor at the Ghana Institute Management and Public Administration (GIMPA) and hold PhD in Political Science from the University of Ghana, Legon. He served as the Head of the Department of Public Management and International Relations at GIMPA. His research interests are in Electoral Politics, Governance, Leadership, Gender, and Public Administration. He won the Best Paper First Prize Award during 13th International Conference on Public Administration, 2018 at Chengdu, China.

Kwaku Obeng Effah

Kwaku Obeng Effah is a graduate student at the Department of Political Science, University of Ghana. Mr. Effah is currently pursuing MPhil Political science with special interest in international relations and democracy.

References

- Abdulai, A. G., & Crawford, G. (2010). Consolidating democracy in Ghana: Progress and prospects? Democratization, 17(1), 26–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340903453674

- Abdulai, A. G., & Sackeyfio, N. (2022). Introduction: The uncertainties of Ghana’s 2020 elections. African Affairs, 121(484), e25–e53. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa028

- Adams, S., & Agomor, K. S. (2015). Democratic politics and voting behaviour in Ghana. International Area Studies Review, 18(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865915587865

- Afrobarometer. (2022). Afrobarometer Round 9, Summary of Results for Ghana, 2022 https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Summary-of-results-Ghana-Afrobarometer-R9-21oct2022-1.pdf

- Agomor, K. S. (2015). Financing political parties under the Fourth Republic of Ghana. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Ghana.

- Agomor, K. S. (2019). Understanding the origins of political Duopoly in Ghana’s Fourth Republic democracy. African Social Science Review, 10(1), 4.

- Alidu, S., Aryeetey, E. B. D., Domfe, G., Armar, R., & Koram, M. E. (2016). A political economy of social protection policy uptake in Ghana. Working Paper 008, PASGR.

- Amoako Addae, M. (2021). Party’s presidential primaries and the consolidation of democracy in Ghana’s 4th Republic. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1978158. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1978158

- Almond, G. A., & Powell, G. B. (1969). The political system. In J. Blondel (Ed.), Comparative government: A reader (pp. 10–14). Macmillan and Co Ltd.

- Almond, G. A., & Powell, G. B. (1966). Comparative politics: A developmental approach. (No. JF51 A57).

- Almond, G. A., Powell, G. B., & Mundt, R. J. (1996). Comparative politics: A theoretical framework. Harpercollins College Division.

- Andrade, C. (2020). Sample size and its importance in research. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(1), 102–103. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_504_19

- Aning, K. (2013). Legal and Policy Frameworks Regulating the Behaviour of Politicians and Political Parties-Sierra Leone. International IDEA. Retrieved from: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/regulating-politicians-and-political-parties-in-ghana.pdf on 18/03/2022.

- Asekere, G. (2019). Internal democracy and the performance of political parties in Ghana’s Fourth Republic: A comparative study of the National Democratic Congress and New Patriotic Party in Selected Constituencies (2000–2016). [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Ghana.

- Asunka, J. (2016). Partisanship and political accountability in new democracies: Explaining compliance with formal rules and procedures in Ghana. Research & Politics, 3(1), 205316801663390. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016633907

- Arkorful, V. E., & Lugu, B. K. (2022). Voters’ behavior: Probing the salience of manifestoes, debates, ideology and celebrity endorsement. Public Organization Review, 22(4), 1025–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-021-00557-x

- Bacchetti, P., Wolf, L. E., Segal, M. R., & McCulloch, C. E. (2005). Ethics and sample size. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi014

- Bartolini, S., & Mair, P. (2001). Challenges to contemporary political parties. In L. Diamond & R. Gunther (Eds.), Political parties and democracy (pp. 327–343). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bauer, G., & Taylor, S. D. (2005). Politics in Southern Africa: state and society in transition. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Beetham, D. (1994). Conditions for Democratic Consolidation. Review of African Political Economy, 21(60), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056249408704053

- Bellinger, N. (2021). Political parties and citizens’ well-being among non-democratic developing countries. Party Politics, 27(6), 1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820934013

- Biau, D. J., Kernéis, S., & Porcher, R. (2008). Statistics in brief: The importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 466(9), 2282–2288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0346-9

- Bjarnegård, E., & Zetterberg, P. (2019). Political parties, formal selection criteria, and gendered parliamentary representation. Party Politics, 25(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817715552

- Bladh, D. (2022). Party functions and party education in the political landscape of Sweden. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 41(4-5), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2022.2104397

- Blaxland, J. (2023). Political party affiliation strength and protest participation propensity: Theory and evidence from Africa. Social Movement Studies, 22(4), 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2061942

- Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2012). Political party activism in Ghana: Factors influencing the decision of the politically active to join a political party. Democratization, 19(4), 668–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2011.605998

- Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2019). Activism of political parties in Africa. In N. Cheeseman (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of politics (pp. 1–20). Oxford University Press.

- Botchway, T. P. (2018). Civil society and the consolidation of democracy in Ghana’s fourth republic. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1452840. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1452840

- Brierley, S., & Kramon, E. (2020). Party campaign strategies in Ghana: Rallies, canvassing and handouts. African Affairs, 119(477), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa024

- Carothers, T. (2006). The backlash against democracy promotion. Foreign Affairs, 85(2), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/20031911

- Chabal, P., & Daloz, J. P. (1998). Africa works: The political instrumentalization of disorder. James Currey.

- Cross, W., & Young, L. (2004). The contours of political party membership in Canada. Party Politics, 10(4), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068804043907

- Daddieh, C. K., & Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2012). In search of ‘Honorable’membership: Parliamentary primaries and candidate selection in Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 47(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909611421905

- Dalton, R. J., & Weldon, S. (2007). Partisanship and party system institutionalization. Party Politics, 13(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068807073856

- Dalton, R. J., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2000). Unthinkable democracy: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. In R. J. Dalton & M. P. Wattenberg (Eds.), Parties without partisans (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press.

- Daddieh, C. K., & Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2014). Ghana: The African exemplar of an institutionalized two-party system? In Party systems and democracy in Africa (pp. 107–128). Palgrave Macmillan.

- De Walle, N. V., & Butler, K. S. (1999). Political parties and party systems in Africa’s illiberal democracies. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 13(1), 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557579908400269

- Diamond, L. J. (2005). Democracy, development and good governance: The inseparable links (Vol. 1). CDD-Ghana.

- Diamond, L., & Gunther, R. (2001). Political parties and democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dodsworth, S., Alidu, S. M., Bauer, G., & Alidu Bukari, G. (2022). Parliamentary primaries after democratic transitions: explaining reforms to candidate selection in Ghana. African Affairs, 121(483), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adac011

- Donno, D. (2013). Elections and democratization in authoritarian regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12013

- Erdmann, G. (2004). Party research: Western European bias and the ‘African labyrinth’. Democratization, 11(3), 63–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351034042000238176

- Fanso, V. G. (2023). Bridging uncompromising borders: Ethnicity, party politics and democracy in Africa. The African Review, 50(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1163/1821889x-20235002

- Fobih, N. (2011). Challenges to party development and democratic consolidation: Perspectives on reforming Ghana’s institutional framework. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46(6), 578–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909611403268

- Gauja, A., & Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2021). The comparative study of political party organization: Changing perspectives and prospects. Ephemera, 21(2), 19–52.

- Gherghina, S., & Fagan, A. (2021). Fringe political parties or political parties at the fringes? The dynamics of political competition in post-communist Europe. Party Politics, 27(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819863628

- Grebe, E. (2015). The politics of social protection in a competitive African democracy: Explaining social protection policy reform in Ghana (2000-2014) (Working Paper No. 361). University of Cape Town. https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/21575

- Gyimah-Boadi, E., & Asante, R. (2006). Ethnic structure, inequality and public sector governance in Ghana. In Y Bangura (Ed.), Ethnic inequalities and public sector governance. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ichino, N., & Nathan, N. L. (2013). Do primaries improve electoral performance? Clientelism and intra‐party conflict in Ghana. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00624.x

- Johnston, M. (2005). Political parties and democracy in theoretical and practical perspectives. National Democratic Institute For International Affairs.

- Karp, J. A., & Banducci, S. A. (2007). Party mobilization and political participation in new and old democracies. Party Politics, 13(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068807073874

- Kelly, N., & Ashiagbor, S. (2011). Political parties and democracy in theoretical and practical perspectives. National Democratic Institute (NDI).

- Krönke, M., Lockwood, S. J., & Mattes, R. (2022). Party footprints in Africa: Measuring local party presence across the continent. Party Politics, 28(2), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688211008352

- Kuenzi, M., & Lambright, G. M. (2011). Who votes in Africa? An examination of electoral participation in 10 African countries. Party Politics, 17(6), 767–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810376779

- Laebens, M. G., & Lührmann, A. (2021). What halts democratic erosion? The changing role of accountability. Democratization, 28(5), 908–928. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1897109

- Lindberg, S., & Morrison, M. K. C. (2008). Are African voters really ethnic or clientelistic? Survey evidence from Ghana. Political Science Quarterly, 123(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00618.x

- Matlosa, K., & Shale, V. (2008). Political parties programme handbook. EISA.

- Manning, C. (2005). Assessing African party systems after the third wave. Party Politics, 11(6), 707–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068805057606

- Morrison, M. K. (2004). Political parties in Ghana through four republics: A path to democratic consolidation. Comparative Politics, 36(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.2307/4150169

- Naing, L., Winn, T. B. N. R., & Rusli, B. N. (2006). Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Archives of Orofacial Sciences, 1, 9–14.

- Nam-Katoti, W., Doku, J., Abor, J., & Quartey, P. (2011). Financing political parties in Ghana. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 12(4), 90–102.

- Olukoshi, A. O. (Ed.). (1998). The politics of opposition in contemporary Africa. Nordic Africa Institute.

- Osei, A. (2013). Political parties in Ghana: Agents of democracy? Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 31(4), 543–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2013.839227

- Owusu Kyei, J. R. K., & Berckmoes, L. H. (2020). Political vigilante groups in Ghana: Violence or democracy? Africa Spectrum, 55(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002039720970957

- Rahat, G., & Cross, W. P. (2018). Political parties and candidate selection. In W. R. Thompson (Ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press.

- Randall, V., & Svåsand, L. (2002). Political parties and democratic consolidation in Africa. Democratization, 9(3), 30–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000266

- Saikkonen, I. A. (2017). Electoral mobilization and authoritarian elections: Evidence from post-Soviet Russia. Government and Opposition, 52(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.20

- Sartori, G. (2005). Party types, organisation and functions. West European Politics, 28(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000334268

- Schedler, A., Diamond, L. J., & Plattner, M. F. (Eds.). (1999). The self-restraining state: Power and accountability in new democracies. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Slothuus, R., & Bisgaard, M. (2021). How political parties shape public opinion in the real world. American Journal of Political Science, 65(4), 896–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12550

- Van de Walle, N. (2003). Presidentialism and clientelism in Africa’s emerging party systems. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(2), 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X03004269

- von Beyme, K. (1982). Parteien in westlichen Demokratien [Parties in Western Democracies]. Piper.

- Wanyande, P. (1998). Democracy and the one-party state: The African experience. In W. O. Oyugi & A. Gitonga (Eds.), The democratic theory and practice in Africa (pp. 71–85). East African Educational Publishers Ltd.

- Wegner, E. (2018). Local-level accountability in a dominant party system. Government and Opposition, 53(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.1

- Young, T. (1993). Introduction: Elections and electoral politics in Africa. Africa, 63(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/1161424