Abstract

This article examines Balinese kriya’s development from sacred to profane. This research is qualitative research with a historical approach. The results show that the presence of past works cannot be separated from the purpose of the religious offering or ceremony. The kriya prehistoric period, which continued in the 8th to 10th centuries with the arrival of Hinduism, was a period of enlightenment. The sacred statues were born as symbols of gods, the island of Bali was a living museum of Javanese Hindu-Buddhism. The 10th to 13th centuries were the centuries of local Balinese genius, marked by kriya statues with a Balinese or folk character. The statue’s innocent character, short stature, and clothing match the character of the Balinese people at that time. In the 13th to 15th centuries, the baroque movement emerged. The presence of this movement is free, wild, and cheerful characters. In 1908, the Balinese kriya appeared passionate about imitating European styles. Openly, kriya began to fulfil needs outside of religion. The tourism development in Bali has brought about both kitsch and kriya retro. Kitsch is made for mass consumption, while kriya retro imitates great art. The desire to present the lost and destroyed past to preserve evidence in the form of replicas, copies, or imitations. It is hoped that the viewer will connect with that time or the social context of the era or place where the objects originated.

Introduction

There are differences between the terms ‘kriya’ and ‘craft’ in Indonesia, in terms of method, purpose, maker, and so on (Sunarya, Citation2020b). However, both are interconnected and mutually developing (Hendriyana, Citation2022). Kriya is an Indonesian fine art. It is a specialized work to fulfil the needs within the walls of the palace. It has a palace patron and is made on ‘orders’ or as an offering to the king, so the work’s perfection is the ultimate goal. Kriya is a work that requires great patience and precision. It is considered a finished cultural product (finesse) and polished (politesse). Meanwhile, wong cilik’s patronage of products that developed in the countryside is called kerajinan (Indonesian Language), works that are considered rough and unfinished. Kerajinan (Indonesian Language) is considered an imitation product, made to fulfil the needs of the small community, which is then known as a craft. Works are made based on industriousness, without creativity from the maker.

Likewise, in developed countries such as Europe, there is a term craft that has almost the same meaning as craft and handicraft or kerajinan, which is also called hand skills. Then came art craft, which in Indonesia is the same as kriya, the maker is called master craftsman or kriyawan or empu. The work of master craftsman, kriyawan, and empu is highly regarded for perfection. Consideration of materials and techniques (craftsmanship), art that cannot be separated from consideration of creativity and function of the work. Muchtar (Soedarso, Citation2002, p. 5) explains that kriya is a branch of fine art that requires very high craftsmanship. The process intersects between fine art and design. Soedarso (Citation2002, p. 2) says that the term kriya has been used in Indonesian since the 70s. The word comes from the Sanskrit language which in Wojowasito’s dictionary is given the meaning of work, action. In the Old Winter Dictionary, it is defined as damel. The word damel, which is a language inggil (highly refined) word addressed to the Kraton family (high caste), makes this work very distinctive in Indonesia. It is a living, breathing work that is honoured and respected. It is very different from crafts that exist to fulfil people’s economic needs. For this reason, kriya will always appear in this paper to refer to works used in connection with religious ceremonial activities, especially in Hinduism in Bali.

Research methodology

In the life of Balinese Hindus, religion, art, and local customs are an integral and inseparable unit. Religion is the norm of life that is believed, art is the excitement of life, and local custom is the rules that must be obeyed together (Negoiță, Citation2021; Sucitra et al., Citation2021). This Tri Tunggal becomes the basis of community life activities, especially in religious ceremonial activities. Ritual activities make kriya wali a symbol, kriya bebali a complement to the ceremony, and kriya balih-balihan entertainment. Kriya wali as a symbol illustrates the omnipotence of Ida Sang Hyang Widi Wasa (God Almighty) (Sunarya, Citation2021). The creation of three-dimensional kriya in the form of statues as symbols, kriya bebali and kriya balih-balihan. The study of the journey of kriya in Bali, as well as the various characters that appear in this study, is a summary of data from the results of qualitative research with an art historical approach. Salim (2001, p. 90) asserts that qualitative research is primarily concerned with understanding within a naturalistic paradigm. The nature of the research is descriptive qualitative (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2020), which is research that produces a systematic study of the periodization, character, and background of the presence of kriya on the island of Bali. Data collection techniques were conducted through a literature study, documentation, and observation.

Discussion

Kriya in the island of Bali: Wali, bebali, and balih-balihan

Kriya is closely associated with the life of the Hindu community in Bali (Sunarya, Citation2021). It is a beautiful symbolic work with the properties of wali, bali, and banten. Properties whose creation means offering or ceremony. Geertz (Citation2000, p. 21) further explains that the festive ceremony makes the island of Bali appear as if it is being pampered. Picard (Citation2006, p. 46) says that Bali is an island full of ceremonial charms, uniqueness, and interesting paraphernalia. Soedarsono (Citation2002, p. 23) further emphasises that the Balinese are an open and very creative society. This culture of welcomeness and creative society has created a repeat visitor to Bali (Sutama et al., Citation2017). It contributes to tourism development and therefore brings different cultures to Bali. The Balinese have then reworked the culture to create works that have Balinese characteristics.

Kriya in Bali is an Indonesian fine art and part of Indonesian culture. According to McFee (Citation1998), the concept of culture is the values, attitudes, and belief systems of a group of people who believe in the patterns and structures of their nature. It is also the sum of internal beliefs and values, reflected in external behaviours and symbols, which influence each other (Brinkmann, Citation2017). In line with this, kriya on the island of Bali has the concept of Tri Hita Karana. This concept is a symbol of harmonious relationships between fellow humans, humans with the natural environment, and humans with Ida Sang Hyang Widi Wasa (God) (Suardana et al., Citation2023; Sukarma, Citation2016; Wulandari & Mahagangga, Citation2021). The harmonious relationship affects thinking, and acting, and how to determine the beauty, moral, spiritual, cultural, and social values that are believed together (Gaudelius, Citation1997). This has also led to aesthetic changes in the works produced on the island of Bali.

Balinese Hinduism uses various symbols and arts, including kriya, dance, and singing, as complements to religious ceremonies. The island of Bali is filled with daily ritual performances, so the island is also known as the island of ritual (Donder, Citation2021). Picard (Citation2006, p. 46) states that Bali is a beautiful island and cannot be separated from the abundance of kriya creation activities as a means of religious ceremonies. In this context, kriya is part of a work of art that fulfils life and can be enjoyed by the community. Rohidi (Citation2000, p. 33) states that a work of art is said to be of quality, if it can be enjoyed and is part of the community life. Kriya cannot be separated from function, so kriya is called its meaningfulness lies in the accuracy of its function (Sunarya, Citation2020a).

Kriya in Bali lives and develops on the level of wali, bebali, and balih-balihan. Kriya wali is ritual kriya as a symbol of the divine. Tillich (Citation2002, p. 69) explains that religious aesthetic symbols are symbols of the Holy and the symbols themselves are not the Holy. Likewise, kriya wali is specially made as a religious aesthetic symbol. It is made as a symbol of the God of Creation, the God of Preservation, and the God of Extermination who are manifestations of Ida Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa (God). Kriya bebali is a work made for ceremonial equipment, while kriya balih-balihan is an entertainment art made to meet the economic needs. Indirectly, it is this diversity of properties and functions that makes kriya in Bali interesting and ngelangeni (Sunarya, Citation2021).

Kriya in Bali in Prehistoric times (before the 8th century AD)

Hoop (Citation1949) says that it is estimated that in 1500 BC, immigrants who came from Yunan in South China, namely from the upper reaches of major rivers such as the Yangtse-Kiang, Mekong, Saluen, Irawadi, and Brahmaputra, began to occupy Indonesia. They were a nation adept at canoe sailing, farming, cattle rearing, house building, carpentry (furniture making), weaving and pottery making. Sardjito (Citation1953) also asserts that the aforementioned people entered Indonesia through Malacca and the islands located in the eastern part, then entered Papua and spread throughout Indonesia. With their expertise, in further development, there are various relics of the results of their skilled hands. Large stones were rolled, not only arranged and erected as menhirs or stamba, but also carved into unique statues. Small fragments in the form of flakes are not thrown away but honed until they are smooth into a beautiful axe. Sedyawati (Rahardjo et al., Citation1998) affirms that megalithic statues have the main cultivation point on the face, not made in detail but only carvings to express the eyes, nose, and mouth. At the same time, other parts of the body are not depicted or depicted only in outline on a solid piece of stone. The visible impression is that of a milestone form, the shape of the stone is more important than the form of the arc itself. Stone statues that will not be destroyed by time mirror the persistence, patience, and perseverance of the past. They are creative human beings who instil many concepts of how to survive, how to create works, and as ancestors of the Indonesian nation.

From 500 to 300 BCE, Indonesians began to recognize ways to cast bronze and forge iron. Experts estimate that the Dong Son people passed these skills down from Tongking in northern Indo-China, who entered Indonesia. This culture was then called the Dong Son culture. Soedarso Sp. (Atmaja, Citation1991) asserts that the naming was unwise, with the discovery of stone necklace moulds in Manuaba Village, Bali. It can be concluded that the metal goods were not entirely brought from their place of origin mainland Asia, but many were also made in Indonesia. In Indonesia, this is called the Metal Age, characterized by the fact that all tools were made of metal. Metal utensils, considered new, are quite developed because they are stronger and easier to work with than stone. Besides being made by beating techniques, not a few are made by pouring directly with a moulding tool, a method that shows the metal age.

Rahardjo et al. (Citation1998) say that in Bali, the bronze (metal) age is characterized by a change in life, namely from a nomadic life to a settled life, from a hunting life to a farming life. Skills such as housing, farming skills, agricultural tools, containers for storing food, and certain ceremonies were also recognised. A significant development is a fishing village on the shore of Gilimanuk Bay, Ambyarsari Negara Village, which is thought to have been fairly large in Prehistoric times. Budiastra (Citation1978) asserts that there was a special class of people who had skills and a class of scholars who regulated customs, especially in the burial of the dead. This settlement complex is also called a pottery complex, with the discovery of various pottery such as cups, pots, pots, jars, beads, and jewellery as grave provisions. This shows that the manufacture of stoneware with various decorations has developed rapidly. The most popular decoration is mesh decoration, in addition to other forms of decoration, such as tumpal and stripes. This situation illustrates that in the Prehistoric Period, there were already skilled pottery makers or makers of various equipment.

In addition, several sarcophagi were found containing ornaments in the form of protrusions of human faces in a laughing attitude, with their mouths agape and their eyes widened. Unique is one sarcophagus found in Ambyarsari (Negara Bali) containing a large lizard ornament. Soedarsono (Citation2002) states that this is an illustration that at that time there was already known to live together in the attachment of the gotong royong system. The activities of the community cannot be separated from the upacāra of worshipping the spirits of ancestors, animist beliefs, and beliefs in totem animals. Soedarso (Atmaja, Citation1991) asserts that lizards, lizards, crocodiles, and lizards have been regarded as incarnations of ancestral spirits, capable of warding off evil and always protecting their offspring. The belief in the power of ancestral spirits is also reflected in the lives of the people of Trunyan Bali. They believe in the power of ancestral spirits, manifested in the form of a stone statue named Ratu Sakti Pancering Jagat or Bhatara Da Tonta with a height of 4 metres, rough carvings, spontaneous and showing a hard, rigid character. According to the beliefs of the Trunyan people, this statue is not the work of humans but piturun, meaning a statue that came down from the sky.

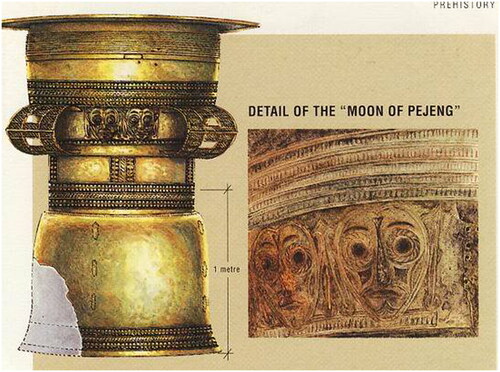

The Prehistoric period, which is thick with the metal age in Bali is marked by the discovery of a very beautiful bronze nekara, which is now stored at Penataran Sasih Temple, Pejeng Village, Gianyar Regency. Bernet-Kempers (Citation1960) states that the Balinese are more familiar with this nekara as Bulan Pejeng or the moon that falls from the sky or Bulan Pejeng. The shape of this nekara is unique with a waist arch variation similar to a dandang (rice cooker) lying face down, which until now is sacred to the local community. This is proof that throughout the history of Bali, it has been famous for its richness in sculpture. While Indonesia’s bronze culture is very close to Dongson, the Pejeng Bali Nekara’s ornamental pattern gives it its style. In addition to the striped pattern, the mask style with round eyes and long ear leaves is the most prominent pattern on the Nekara Pejeng, Bali.

The belief in the power of spirits, embodied in the form of masks, seems to have spread in Balinese life in prehistoric times. The creepy mask is a manifestation of the power of an imaginary head that symbolises the ancestors or ancestral spirits of the Balinese people, as seen in . The scary character of the mask is carved on the elephant cave in Gianyar Bali, which is sacred to Hindus to this day.

Figure 1. Nekara Pejeng or Moon of Pejeng (Mardika, Citation2018).

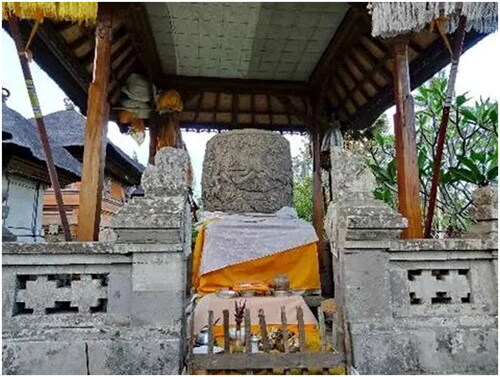

The carved face or mask of a sinister character with widened eyes symbolises strength and protection from evil spirits. In other parts, there are undulating curves like clouds in the sky, which is almost similar to the mega-cloudy motif. The community now preserves Gua Gajah and has become a popular tourist attraction, as seen in .

Figure 2. Carving of a Prehistoric Goa Gajah Mask (Prabhawa, Citation2018).

Kriya in Bali is a reflection of the museum of Javanese Hindu life (8th to the 10th century AD)

It began with the fall of the Bedahulu kingdom in 1343 and became a new chapter of Majapahit rule in Bali. The centre of the empire then moved to Gelgel Suwecapura Kelungkung. The Majapahit government gave birth to a new pattern of governance in Bali, and the process of cultural transformation of Majapahit had a considerable influence on Balinese art. The government made Bali the centre of the development of Hindu-Javanese culture or can be mentioned as the centre of preservation and successor of Majapahit culture.

Balinese history shows that the entry of new beliefs (Hinduism) in Balinese ritual activities was in line with the new governance, namely the period of King Gunapriya Dharmapatmi from Java. Titib (Citation2007) asserts that the introduction of Hinduism in the late 8th century was a concept of enlightenment to the beliefs that had grown and developed before. This era is also called the beginning of Balinese history and is a period when Hindu-Buddhist religions from Java influenced Bali. There is also evidence that there was direct contact between Balinese culture and Javanese or Indian Hindu culture.

Goris (Citation1948) asserts that the Batu Inscription, dated 960 AD, mentions King Candra Bhaya Singa Warmadewa as a wise king who ruled in Bali. The inscription, which is kept in Sakenan Temple, Manukaya Village, Tampaksiring, Gianyar, mentions the making of tirta in the hampul water (Tirta Empul). This inscription also shows that, the start of a new chapter in the history of Balinese culture related to Javanese culture. Moreover, there was a marriage between King Dharma Udayana Warmadewa who was born in Bali in 963 with Sri Gunapriya Dharmapatni. The princess was the daughter of Makuta Wangsawardhana or the granddaughter of Empu Sendok from East Java. After this marriage, they settled and became kings in Bali from 989-1001 AD. In the inscriptions, the wife’s title is always mentioned first, indicating that Udayana’s wife, Sri Gunapriya Dharmapatni, played an important role in the royal government in Bali at that time. It seems that the relationship between the Javanese and Balinese kingdoms was quite harmonious, the people lived side by side comfortably and peacefully. This relationship brought changes to the life activities of the Balinese people, especially the incoming culture that gave new colours to the existing culture. This is evidenced by the use of the Old Javanese language (Kawi) in writing inscriptions.

The display of kriya in the form of statues, which was originally only for ritual activities for the royal class, began to be introduced to the wider community, so this kriya developed massively in the Balinese community. Its appearance is thick with the influence of Buddhist statues in Java. Soedarsono (Citation1972) asserts that the presence of various Balinese kriya statues with Javanese-Indian characters makes Bali Island mentioned as a living museum of the Hindu-Javanese Indonesian era. The island is a preservation or continuation of the culture that has grown in Java.

Kriya in Bali with kebalian or folk characterisation (the 10th to the 13th century AD)

Balinese kriya of kebalian character means the presence of kriya that began to leave the Javanese Hindu style, namely the birth of kriya of statues with a folk character. Of course, it is very different from the birth of Balinese kriya in the previous period or when Bali Island was a Javanese-Indian living museum. The 10th to 13th centuries were the centuries of enthusiasm for the birth of statues of gods in Bali. It began with the enthusiasm of various cults or sects that seemed to be competing to realise the various forms of their respective gods. Kriya statues of gods also sprung up and, in the end, kriya statues with kebalian or folk characters were born. Kriya broke away from the Hindu-Javanese influence. Kriya in the form of statues that adjust the description of the life of the Balinese environment itself.

Scholars say that the 10th to 13th centuries were the time of the birth of Bali’s local genius. During this period, the facial character of the statues is naturally innocent, the body shape is following the Balinese people. They were shorter than the statues of the period of Hindu-Javanese or direct Indian influence, which can be seen in the kriya of Widyadari statue and Raja statue, as seen in . Although the kriya of the above statues are no longer intact due to age, they appear to have once been extraordinarily beautiful. This folk character did not appear suddenly, but the fusion process lasted centuries.

Figure 3. Kriya Statue of Raja and Ratu with kebalian style found in Puncak Penulisan Temple (Sayoga, Citation2016).

The processing of flora and fauna into kriya kekarangan (compositions) was also introduced. For instance, karang gajah is a stylisation of an elephant, karang daun is a stylisation of various leaves, karang goak is a stylisation of a crow, karang kakul is a stylisation of a snail, and so on. Kekarangan has a task as a field filler or as an ornament such as statue accessories and is also applied to statue clothing. The subsequent development of kekarangan has played an important role in the life of Balinese society. It is present in a fairly broad role, namely beautifying sacred buildings (temples), residential areas, as well as hotels or inns that appear like mushrooms on the island of Bali later.

Kriya in Bali during the baroque movement (13th to 15th century AD)

Since the past (prehistoric times to the present), religion, namely Hinduism, has been a major umbrella for the creation of art in Bali. The umbrella that encouraged the uņdagi always to present their creations, so that in the 13th to 15th centuries works of a different character were born, namely works in the baroque movement (Read, Citation2000). The works are dazzling, and energetic, showing a leap away from the previous works, which were wild, fiery, and full of excitement (Holt, Citation2000). Very obviously, Balinese art in this development favours the beautiful appearance of its deities, unlike the pale ascetics, the statues are vibrant, luxurious ornate, and very passionate.

The 13th century was Bali’s initial period of dynamic Javanese Hindu development. Holt (Citation2000) asserts that the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries saw the birth of Balinese kriya of a different character than before, namely the emergence of the baroque movement. The birth of the Balinese kriya was a dazzling, energetic work, showing a leap from previous works. This is reflected in the kriya’s wild, fiery, and exuberant movements. A development that favours the display of beautiful, vibrant gods and not the pale, ascetic ones. Bernet-Kempers (Citation1960) asserts that the baroque style of free and wild sculpture is reflected in a Pejeng vessel dated 1329 AD. The vessel is named Naragiri or the mountain of mankind in the form of a cup made of hollow stone for storing water, as seen in .

Figure 4. Kriya Naragiri with baroque style (Sudiatmika, Citation2015).

On the sides of the vessel, the carvings are visible in their complexity, an ornamentation that shows the sculptor’s effort to display the object in great detail. The motifs shown are mountains and jungles wrapped around a crowned dragon (dragon king) and gods with their heavenly creatures. On the lower side, fishermen are seen coming home from fishing with their catches. The sculpture means that the mountain is a symbol of fertility, a source of water, and a source of happiness that needs to be preserved.

The next baroque gesture is seen on the Śiwa Bhairawa statue. The deity is dancing with his feet apart, a symbol of various good and evil traits, and very frightening (see (a)). Meanwhile, the Narasiŋha statue (see (b)) is a depiction of the heroic nature of the lion-headed man in the Śiwa Bhairawa sect (Stutterheim, Citation1935). The kriya influenced by the baroque movement has a lively and elaborate ornamentation that brings out the rough texture of the carved motifs in a vibrant manner. Sculptures that show the freedom of the soul and the search for fantasy and fulfil the creator’s self-indulgence display unique works in the form of excessive enthusiasm.

Figure 5. (a) Arca Śiwa Bhairawa and (b) Narasimha (Stutterheim, Citation1935).

Kriya in Bali during the influence of European artists (the 16th century AD until now)

Presumably, Europeans have long eyed the beauty of Bali Island, this is evidenced by the arrival of a group from Europe (Netherlands) led by Cornelis de Houtman in 1601 (Hanna, Citation2004). Furthermore, Gde Agung (Citation1989) asserts that the European group had set up a lodge in Kuta, Denpasar, Bali for their stay. In contrast to their meeting in Banten, which was rejected by the Banten ruler. In Bali, Cornelis de Houtman’s entourage was well received. Later, they gave mementos, in the form of red velvet cloth, beautifully patterned glassware, and some Dutch currency made of silver. This encounter influenced the creation of later Balinese decorative arts. The Balinese transformed the Dutch ornamental art into a stylised vine motif with wide leaves. This motif is pattra orlanda (Dutch patra), which the Balinese favour as an ornament for sacred buildings or residences. This was the first time Balinese sculpture openly catered to needs outside of religion.

The development of the kriya mentioned above makes kriya an active subject of ritual significance that people believe to be a source of protection. On the other hand, it is also a passive object, with its imitations sold to fulfil economic needs. The existence of such Balinese kriya is not much different from the existence of Ganesha statues in Thailand. Agarwal et al. (Citation2018) mentioned that the Ganesha statue in Thailand is both an active subject and a passive object. Ganesha as an active subject is a symbol of God while being a passive object in the market where the statue is sold. The presence of kriya in the form of statues of gods and various symbolic carvings to decorate temples, such as kriya karang Bhoma (see ), gives hope for peace and comfort to Hindus in Bali. Now the function shifts, kriya karang Bhoma which is unique and full of symbolic meaning becomes a passive subject to fill the demands of tourism and only beautify the building.

Figure 6. Kriya Carving Karang Bhoma on the main entrance of Kori Agung (Bewish Bali, Citation2016).

Sudarta (Citation1975) explains that in 1928 Rudolf Bonnet from the Netherlands and Walter Spies from Germany settled in Bali. They showed new naturalist patterns works that had never been seen by Balinese art workers. The Balinese artists were astonished by something strange, unique, and interesting. From then on, Balinese sculptors imitated naturalist forms with secular themes or realist scenes of daily life.

At the same time, Stutterheim (Adnyana, Citation2015; Rhodius & Darling, Citation1980) states that I Tegalan, a sculptor from Belaluan, Denpasar, who was initially interested in Miguel Covarrubias’ paintings of elongated humans, tried his hand at the togog ‘elongated style’, which is a form of sculpture with elongated organs, as seen in . Likewise, Ida Bagus Gelodog’s kriya from Mas Village, Gianyar, creates dancing people, people blowing flutes, and archers with long arms and legs, a style that has never appeared before. It is not enough to imitate objects of everyday life, even the statues of gods and goddesses that are made long are increasingly lively.

Figure 7. Kriya in Bali island with European artist influence style (Museum Puri Lukisan, Citation2021; Peppel, Citation2023).

Balinese uņdagi’s horizons are increasingly open, seeing the reality they are trying to break out of their long-standing attachment. This was seen with the advent of Ida Bagus Gelodog from Mas Village in Gianyar who created carvings of Balinese people in everyday life with long arms and legs (Ktut Agung et al., Citation1985). Noting the talents and abilities of Balinese artists, especially those in the Ubud area and its surroundings, who were creative and very interesting, in 1935 Rudolf Bonnet and Walter Spies together with Cokorda Gde Agung Sukawati established an Art Foundation called the Pita Maha Foundation. The foundation maintains and sustains the newly created Ubud style (Holt, Citation2000). Although the Pita Maha Foundation is more concerned with the development of painting, the spirit of craftsmanship in the creation of works has not diminished. This is evidenced by the emergence of I Cokot who managed to show his identity with the processing of primitive motifs, even giving rise to a new genre in craft art, namely cokotism.

In the 1930s, Balinese sculptors began to make imitation art from ritual art to sell (Ktut Agung et al., Citation1985). Balinese kriya developed into handicraft products to fulfil the needs of tourism. Handicrafts are also called souvenirs, which is the beginning of Balinese mass art. This type of acculturation art is considered a pseudo-traditional form of art (Soedarsono, Citation2002). The form of the work still refers to traditional forms and rules, but the traditional values, which are usually sacred, magical, and symbolic, have been set aside or made pseudo. The arrival of growing tourism has shown the destruction behind the pseudo-enjoyment received by the Balinese. According to Picard (Citation2006), Balinese people are competing in shifting their main task, namely as religious servants and turning to fulfilling the needs of tourists. In an ever-evolving era, Balinese may miss something they love, but also discover something new, a pseudo-art (Gustami, Citation2007). This situation is certainly natural in the social development of society. Industrial progress that occurred must also be balanced with the progress of the community. When an area becomes a tourist destination, the people must also be ready to provide various products for tourists. Artists in Bali have a responsibility to improve the quality of Balinese life.

Kriya in Bali for tourism needs (the 16th century AD until now)

Kriyawan has the duty and responsibility to create unique, beautiful, and meaningful artworks. kriyawan is the name of the creator of kriya, they are also called undagi, empu, or master craftsman (Sunarya, Citation2022). The ideal kriyawan has entrepreneurship skills in the community. In addition, Sri Edi Swasono (Swasono, Citation2003) asserts that kriyawan should have a creative spirit, risk-taking, forward-thinking, and achievement. Creative thinking is useful for creating ideas in developing their work (Hadzigeorgiou et al., Citation2012). Kriyawan who has creative thinking will also have several traits consisting of fluency, flexibility, and originality (Apriwanda & Hanri, Citation2022). Creativity requires sustainable steps, a spirit that gives birth to various kriya that develop in society. In addition, they are also expected to be resilient, diligent, not easily discouraged, disciplined, and firm in their stance. They are also passionate with a strong work ethic, and cleverly breakthrough regulations to find opportunities (Sunarya, Citation2020a).

Aesthetic Style

People need art such as kriya two-dimensional carvings that are applied to various traditional houses as well as in various grand and luxurious hotels in Indonesia. Kriya develops towards paintings such as the paintings of Wayang Beber, the paintings of Wayang Kamasan, glass paintings, and others. Kriya is a preservationist and by imitating kriya adiluhung, tourists’ needs for kriya rituals are fulfilled. The kriya adiluhung is full of principles, in terms of the method, materials, and maker. It is a noble cultural heritage of the Indonesian people (Sunarya, Citation2020a).

In the concept of post-modern culture, the change in function where social functions is greatly reduced and objects become objects of artistic value that are only displayed and enjoyed, (kriya) is called the phenomenon of aestheticization in everyday life. The boundaries between art and culture, culture and commerce, and art and everyday life have become blurred. This style of aestheticization is linked to consumer culture through a lifestyle centred on the consumption of aesthetic objects and signs (Salim Hs, Citation2005). The commodification of places, people, and culture, in this case, kriya, is an inherent part of the modern tourism industry (Stone & Grebenar, Citation2022). As such, tourist encounters are seen through a commercial lens, where tourists will seek out and purchase cultural mementoes (Morgan & Pritchard, Citation2005).

The objects presented are only similar and the prices are much lower. Many things cause the presence of products like this, among others: the emergence of machines that can help humans in the process, the material being replaced with other materials that are less precise, the mixture of raw materials is less precise, the quality is not good, and so on. But because travellers are limited in time, and space to carry, and the price is cheaper. They still buy it too, as a substitute for the original object, objects like this are called kitsch. These objects or designs materialise concepts such as commercialism or sentimental merit (Richard Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009), easily understood contents (Lugg, Citation1999), or the concept of shallowness (Potts, Citation2012; Sturken, Citation2007). However, it may be seen, kitsch can be seen through the commercial prism of cultural influence (Emmer, Citation2014).

Kriya kitsch, kitsch, or knick-knacks are also known as popular kriya or kriya for the poor (Rohidi, Citation2000). Such works are often considered as works that do not fulfil the criteria of beauty, but due to their entertaining and easy-to-understand nature, they have their society and fans. Kitsch, trinkets, or popular kriya offer a solution to limitations, which are limitations of time, money, and so on. They (popular works) appear to offer symbols that are familiar to the lives of people who belong to the lower and middle-class economy. Such works are created to fulfil the needs of the community in certain activities such as wedding ceremonies, birthdays, and other celebrations. Its main purpose is to be enjoyed without reflection, cheap, and easy to obtain.

Kitsch or trinkets or also popular kriya art for mass consumption, the appearance of what it is, even seems bad, is morally free or value-free, art that shows the search for aesthetics separated from ethics (Wibawa, Citation2018). This art as a complementary work for a cheap visit is quite adequate. Whereas kitsch kriya, trinkets, and popular kriya are kriya to fulfil the demands of portability and low prices that are adjusted to the speed of the manufacturing process, in addition to using manipulated raw materials. Kitsch tends to be crude, and perfunctory and does not consider quality.

The development of Balinese kriya continues until now, with the lively tourism the need for kriya is inevitable as souvenirs. Kayam (Citation1981) confirms the birth of kitsch art, namely ‘art in order’, simplified art, shortened duration performance art, fine art, and souvenir sculpture. Kitsch is related to the needs of mass consumption, packaged and commercial art, specialised for the tastes of a half-assed urban population. Morreall and Loy (Citation1989) mention that kitsch sold in shops can be called instant art, where the purchaser can feel the immediate pleasure of buying or paying without having any special knowledge or understanding of the meaning of the object.

The consumers of kitsch do not need a full ritual of confirmation, just to entertain themselves while reconciling values wrapped in nostalgia, a sense of longing for the atmosphere. Although kitsch art exists in people’s lives who are closely related to traditional arts, this work has a different status from traditional arts. Kitsch art is only an entertainment art and has a status separated from ritual elements, while traditional art is the opposite. The emergence of kitsch art or art for mass consumption does not mean that the work is bad or has a lower quality, but the emergence of this work is an inevitable phenomenon in the dynamic development of society. Sumartono (Citation1989) asserts that kitsch is an art that is present in the cultural dimension of the post-modern movement, whose development in creative areas in line with market demands is a dynamic of community creativity in responding to market needs. Solomon (Citation1991) mentions that kitsch is called bad art, but its ugliness makes it interesting. This is because the imitations when making it reach high perfection or exactly what is imitated. Furthermore, Bourdieu (Citation1984) adds that kitsch appears too simple without meaning and makes it shallow and cheap. Works that are made without thinking. Santikarma (Citation2004) asserts that craft works are for the continuation of kitchen smoke, and commercial motivation to fulfil the tourism industry.

Kriya kitsch is an art that is purely for self-entertainment while matching values wrapped in nostalgia, a sense of longing for the atmosphere. The term comes from the German kitschen meaning to cheapen and make (Morreall & Loy, Citation1989). Kitsch appears very simple, and meaningless, making it superficial and cheap (Bourdieu, Citation1984). In the fast-paced art of tourism fulfilment, anything is going through the process of ‘kitschification’ for an economic purpose (Stone & Grebenar, Citation2022). Kitsch is the spirit of reproduction, adaptation, and simulation (Mujiyono, Citation2016). Kitsch production is the spirit of mass-producing high art, bringing high art from the elite to the public through mass production; through the process of removing or reducing the values of high art. Kriya kitsch is not only a perfect complement to the visit for tourists, but also an economic engine for the communities around the tourist attractions. It is a need, not just a tourist necessity. Although kitsch is a commercialised fast art, it characterises the art of urban society and has a great influence on city life (Kayam, Citation1981). In the development of art history, changes in the style and content of art cannot be separated from changes in society at any time (Ortlieb & Carbon, Citation2019).

Kitsch, although it exists on the sidelines of life, has a different status from traditional art, which was born on the sidelines of traditional communities (see ). It (kitsch) has a status apart from the ritual elements that support the integrity of a community, while traditional art is attached to such elements. The birth and development of kitsch is an artistic phenomenon that cannot be avoided in a society. Although kitsch is a commercially sold fast art, it is a feature of urban art and has a great influence on city life (Kayam, Citation1981).

Figure 8. Kitsch that is sold in Bali (Ramadhian & Cahya, Citation2020).

Kriya Retro

Gustami (Citation2002) emphasises that as a cultural product, kriya undergoes changes and developments according to the demands of the times. Such as the birth of retro kriya, which is also a revival of kriya adiluhung. The kriya of the past, which is ancient, is re-presented for the present. Retro kriya is a nostalgia and longing for the art of the past. Various kriya designed in the 1920s, which are classic, are then juxtaposed with the present. As can be seen in the display of lesung used as home decoration, the display of cowsheds for restaurants, as well as the appearance of lawasan batik, and the style of lamps that take the form of ancient styles, as seen in . The term retro comes from the words retrospection, retrograde, and retrogressive (Guffey, Citation2006; Reynolds, Citation2011), which refer to cultural trends, flavours, technological obsolescence, and medieval styles (Guffey, Citation2006; Guntur, Citation2021).

Figure 9. Kriya retro for a restaurant (Agista, Citation2021).

This culture is born through the intersection between mass culture and personal or collective memory (Castellano et al., Citation2013; Guntur, Citation2021). The kriya industry from wood, clay, metal, wicker, batik, stone, and so on produces many retro kriya objects. The craftsmanship of this product uses various techniques such as carving, lathe, batik, and so on, produced by kriyawan from various parts of Indonesia.

A simulacra room is a space that contains objects of various forms and from various eras hung, pasted on the walls or displayed on tables and in glass cabinets (Salim Hs, Citation2005). It is further argued that simulacra are simply the eclectic bringing of elements of the past into the present as nostalgia. This is similar to retro style in that there is a desire to present a lost and vanished past to preserve evidence in the form of replicas, imitations, copies, or imitations. The viewer is connected to that time or the social context of the era or place from which the objects originated. This is something that needs to be recognised to live and thrive today and in the future.

In the development of art history, changes in the style and content of art are inseparable from changes over time. Changes in society, such as politics or rulers, will provide new aesthetics (Ortlieb & Carbon, Citation2019). In the era of development, Bali may lose something it loves, but it is also proud that it has discovered and created something new. The new thing is pseudo-art, in which the creation of sculpture leads to economic interests and life functions (Gustami, Citation2007). The era presents the nature of Balinese art workers, who are tenacious in wrapping all rituals into commercial forms. It is an answer that the development of the times about the development of tourism also develops Balinese sculpture for tourism needs. Art brings to life new social groups of entrepreneurs and employees in the hospitality industry, restaurants, transport, craft industry, hawkers, and other social groups that play a role in public service in Bali.

Conclusion

Until now, the presence of kriya in Bali is closely tied to the lives of its people. Hinduism melts kriya into symbolic meanings, beautiful works with wali, bali, and banten functions. These traits and characters make the kriya sacred and function as offerings or religious ceremonial tools. This situation confirms that kriya was already present in the Prehistoric Period in Bali. The 8th-10th centuries saw Balinese kriya’s development under Hinduism’s influence. The century of enlightenment saw the birth of kriya in the form of statues as symbols of gods with Javanese-Indian characters and made Bali a living museum of Hindu-Javanese. The 10th-13th centuries saw the arrival of Bali’s local genius, the display of kriya statues with a kebalian or folk character. The gods’ statue kriya adjusts to the state of Balinese society at that time. The 13th to 15th centuries saw the baroque movement, Balinese kriya of a different character than before, dazzling, vibrant, wild, blazing, and full of excitement, which saw a surge away from previous works.

1908 was the first time Balinese art openly fulfilled needs outside religion or kriya profane. In 1928, the island was visited by Rudolf Bonnet from the Netherlands and Walter Spies from Germany who settled in Bali and showed naturalist-style works, new models that Balinese artists had never seen before. They imitated the strange forms they saw as sculptures specifically sold for economic needs.

The development of Balinese kriya is the presence of aestheticisation styles, namely kitsch and retro kriya. Kitsch is art in its task to fulfil the needs of tourism. It is also called mass art or handicraft. Kitsch is not categorised as bad art, but the task of its presence is limited to entertainment art or souvenir art. It evokes memories of one’s visit and is an imitative art as a remedy for tourists’ desire to own the sacred art of the Balinese people. Whereas retro kriya is an imitation kriya of noble art, and makes a return to past trends. The desire to present the lost and destroyed past as an effort to preserve evidence in the form of replicas, imitations, copies, or imitations. Those who witness it will be connected to that time or the social context of the era or place where the objects originated. So that, the kriya of the past can continue to live and thrive in the present and the future.

Authors’ contribution

I Ketut Sunarya did the conception and design, and then He (I Ketut Sunarya) and Ismadi analysed and interpreted the data. Both of them also did the drafting of the paper. I Ketut Sunarya and Ismadi revised it critically for intellectual content. Finally, I Ketut Sunarya gave the final approval of the version to be published, and both authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the Rector of Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Prof. Dr. Sumaryanto, M.Kes., AIFO, who provided suggestions for writing this article and suggested, that it be submitted to Cogent Social Science. Likewise, Ni Kadek Dianita, M Pd., who has helped translate and edit this article. Also, I Wayan Nain Febri, M. Sn. documented the photographs used in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

I Ketut Sunarya

Prof. Dr. I Ketut Sunarya, M. Sn. was born in Pekutatan, Bali, Indonesia. His kriya vocational education was at Gianyar, Bali. His undergraduate education was at the Indonesian Art Institute, Yogyakarta. His master’s education took the creation of kriya at the Postgraduate Indonesian Art Institute, Yogyakarta. His doctorate was at Universitas Gadjah Mada. He often conducts research that is self-funded, as well as funded by the university, the government, or other institutions. He also served the community by teaching about kriya. His writings on kriya have been widely published in national journals in Indonesia and internationally. He is a lecturer at Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta at the Kriya Education Study Programme. His research is on kriya and kriya education. He received the title of Professor in the field of kriya in 2020 with a speech entitled “Kriya Nusantara National Identity towards Jagadhita”

Ismadi

Ismadi, M.A. was born in Klaten, Central Java in 1977. He graduated from D3 Department of Finished Goods Design and Technology, at the Yogyakarta Leather Technology Academy (1999), S1 Department of Kriya Education, at Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta (2004), S2 Department of Performing and Fine Arts Studies, Universitas Gadjah Mada (2010). Since 2005, he has been a lecturer at the Kriya Education Study Programme, Department of Fine Arts Education, Faculty of Language, Arts, and Culture, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta. He also served the community by teaching about kriya. His writings have been widely published in national journals in Indonesia and internationally.

References

- Adnyana, I. W. (2015). Pita Maha: Gerakan sosial seni lukis Bali 1930-an. Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta.

- Agarwal, R., & Jones, W. J; Mahidol University International College, Thailand. (2018). Ganesa and his Cult in Contemporary Thailand. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 14(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2018.14.2.6

- Agista, Y. (2021, January 4). Lesehan Oemah Wawa Klaten, Rumah makan bernuansa Jawa kuno yang unik. Retrieved November 22, 2022, from Kisah Foto https://www.kisahfoto.com/2021/01/lesehan-oemah-wawa-klaten.html

- Agung, I. A. A. G. (1989). Bali pada abad XIX. Gadjah Mada University Press.

- Apriwanda, W., & Hanri, C. (2022). Level of creative thinking among prospective chemistry teachers. Jurnal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia, 11(2), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.15294/jpii.v11i2.34572

- Atmaja, M. K. (1991). Perjalanan seni rupa Indonesia dari zaman prasejarah hingga masa kini. Seni Budaya, Pameran KIAS.

- Bali, B. (2016). Bhoma the king Of Balinese jungle. Retrieved December 8, 2019, from Bali Cultural Information https://balicultureinformation.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/boma-bali/

- Bernet-Kempers, A. J. (1960). Bali purbakala, petunjuk tentang peninggalan-peninggalan purbakala di Bali (Soekmono, Ed.). Penerbit Ichtiar.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste [La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement] (R. Nice, Ed.). Routledge.

- Brinkmann, K. (2017). Culture: Defining an old concept in a new way. An International Peer-Reviewed Journal, 35, 31–34. www.iiste.org

- Budiastra, P. (1978). Sejarah Bali. Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

- Castellano, S., Ivanova, O., Adnane, M., Safraou, I., & Schiavone, F. (2013). Back to the future: Adoption and diffusion of innovation in retro-industries. European Journal of Innovation Management, 16(4), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-03-2013-0025

- Donder, I. K. (2021). Aspects of Bali culture and religion: The implementation of vedic teaching as the basis of Balinese Hindu religious life. Journal of Positive Psychology & Wellbeing, 5(3), 1124–1138.

- Emmer, C. E. (2014). Traditional kitsch and the Janus-head of comfort. In J. Stępień (Ed.), Redefining kitsch and camp in literature and culture (pp. 23–40). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Gaudelius, Y. (1997). Postmodernism, feminism and art education: An elementary workshop based on the works of Nancy Spero and Mary Kelly. In J. Hutchen & M. Suggs (Eds.), Art education: Content and practice in a postmodern era (pp. 132–142). National Art Education Association.

- Geertz, C. (2000). Negara teater, kerajaan-kerajaan abad ke-19 (H. Hadikusumo, Trans.). Adhipuro.

- Goris, R. (1948). Sejarah Bali kuno. Gadjah Mada University Press.

- Guffey, E. E. (2006). Retro: The culture of revival. Reaktion Books.

- Guntur. (2021). Kriya retro: Beautifikasi dan legitimasi artistik. Sidang Senat Terbuka, Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta. Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta.

- Gustami, S. P. (2002). Seni kriya akar seni rupa Indonesia. Seminar International Seni Rupa: Orientasi Dalam Penciptaan Dan Pengkajian Seni Kriya Indonesia Di Era Masyarakat Terbuka. Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta.

- Gustami, S. P. (2007). Butir-butir mutiara estetika Timur, ide dasar penciptaan seni kriya Indonesia. Prasista.

- Hadzigeorgiou, Y., Fokialis, P., & Kabouropoulou, M. (2012). Thinking about creativity in science education. Creative Education, 03(05), 603–611. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.35089

- Hanna, W. A. (2004). Bali Chronicles. Periplus.

- Hendriyana, H. (2022). Meaning differences in indigenous kriya and crafts in Indonesia and their leverage on the craft of science globally. Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education, 22(2), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.15294/harmonia.v22i2.36567

- Holt, C. (2000). Melacak jejak perkembangan seni di Indonesia (R. M. Soedarsono, Trans.). Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia.

- Hoop, A. T. A. T. V. D. (1949). Ragam-ragam perhiasan Indonesia. Genootschap Van Kusnsten en Wetenschppen.

- Kayam, U. (1981). Seni tradisi dan masyarakat. Sinar Harapan.

- Ktut Agung, A. A., et al. (1985). Monografi daerah Bali. Proyek Pemerintah Daerah Tingkat I, Provinsi Bali.

- Lugg, C. A. (1999). Kitsch: From education to public policy. Falmer Press.

- Mardika, I. M. (2018). Kebudayaan perunggu sebagai puncak peradaban Bali. Sudamala, 4(1), 22–27.

- McFee, J. K. (1998). Cultural diversity and the structure and practice of art education. National Art Education Association.

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2005). On souvenirs and metonymy: Narratives of memory, metaphor and materiality. Tourist Studies, 5(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797605062714

- Morreall, J., & Loy, J. (1989). Kitsch and aesthetic education. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 23(4), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333032

- Mujiyono. (2016). Logika intertekstual, dekonstruksi, dan simulasi dalam karya seni rupa posmodern: Studi kasus pada karya redesain kaos cenderamata Obyek Wisata Religi Demak. Jurnal Imajinasi, X(1), 39–50.

- Museum Puri Lukisan. (2021). Balinese wood carving. Retrieved August 17, 2020 http://museumpurilukisan.com/museum-collection/wood-carving/

- Negoiță, A. G. (2021). Human’s spiritual crisis and the existential vacuum. Cogito, 8(1), 21–31.

- Ortlieb, S. A., & Carbon, C.-C. (2019). A functional model of kitsch and art: Linking aesthetic appreciation to the dynamics of social motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2437. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02437

- Peppel, S. V D. (2023). Birth of Gana. Retrieved October 22, 2023, from Deco Art Bali Blog https://artdecobali.blog/portfolio/birth-of-gana/

- Picard, M. (2006). Bali pariwisata budaya dan budaya pariwisata (J. Couteau & W. Wisatana, Trans.). d’Extreme-Orient.

- Potts, T. J. (2012). “Dark tourism” and the “kitschification” of 9/11. Tourist Studies, 12(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797612461083

- Prabhawa, K. Y. (2018). Produksi dalam komodifikasi situs Pura Goa Gajah. Sudamala, 4(1), 42–48.

- Rahardjo, S., Munandar, A. A., & Zuhdi, S. (1998). Sejarah kebudayaan Bali, kajian perkembangan dan dampak pariwisata. Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

- Ramadhian, N., & Cahya, K. D. (2020, September 24). 17 Oleh-oleh kekinian khas Bali, apa saja? Retrieved October 19, 2023, from Kompas https://travel.kompas.com/read/2020/09/24/140500527/17-oleh-oleh-kekinian-khas-bali-apa- saja?page=all#page2

- Read, H. (2000). Seni: Arti dan problematiknya (Soedarso, Trans.). Duta Wacana University Press.

- Reynolds, S. (2011). Retromania: Pop culture’s addiction to its own past. Faber and Faber, Inc.

- Rhodius, H., & Darling, J. (1980). Walter Spies and Balinese art. Tropical Museum.

- Rohidi, T. R. (2000). Kesenian dalam pendekatan budaya. Nova.

- Salim Hs, H. (2005). Simulakra koleksi benda seni. Gong, VII(68), 2005.

- Santikarma, D. (2004). Pecalang Bali: Siaga budaya dan budaya siaga. In I. N. D. Putra (Ed.), Bali menuju Jagaditha: Aneka perspektif (pp. 113–131). Pustaka Bali Post.

- Sardjito, M. (1953). The revival of sculpture in Indonesia. Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Sayoga, P. G. W. (2016). Telusuri jejak Pura Puncak Penulisan Bali, pura tertua di pulau dewata. Retrieved December 12, 2019, from https://www.kintamani.id/telusuri-jejak-pura-puncak-penulisan-bali-pura-tertua-pulau-dewata-001068.html.

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (2009). (Re)presenting the macabre: Interpretation, kitschification and authenticity. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 109–128). Channel View Publications.

- Soedarso, S. (2002). Merevitalisasi seni kriya tradisi menuju aspirasi dan kebutuhan masyarakat masa kini. Seminar Seni Kriya Dalam Rangka Dies Natalis ISI. Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta.

- Soedarsono, R. M. (1972). Djawa dan Bali, Dua pusat perkembangan drama tari tradisional di Indonesia. Gadjah Mada University Press.

- Soedarsono, R. M. (2002). Seni pertunjukan Indonesia di era globalisasi. Gadjah Mada University Press.

- Solomon, R. C. (1991). On kitcsh and sentimentality. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 49(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/431644

- Stone, P. R., & Grebenar, A. (2022). ‘Making tragic places’: Dark tourism, kitsch and the commodification of atrocity. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 20(4), 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2021.1960852

- Sturken, M. (2007). Tourists of history: Memory, kitsch, and consumerism from Oklahoma city to Ground Zero. Duke University Press.

- Stutterheim, W. (1935). Indian influences in old Balinese art. The India Society.

- Suardana, I. W., Yusuf, A., Hargono, R., & Juanamasta, I. G. (2023). Spiritual coping “Tri Hita Karana” among older adults during pandemic COVID-19: A perspective of Balinese culture. Universal Journal of Public Health, 11(3), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujph.2023.110303

- Sucitra, I. G. A., Lasiyo., & Tjahyadi, S. (2021). The art representation of Hindu-Bali philosophy to strengthen local wisdom appreciation on contemporary artwork of Balinese diaspora painters in Yogyakarta. Cogito, 13(2), 62–76.

- Sudarta, G. (1975). Bali dalam tiga generasi. PT Gramedia.

- Sudiatmika, I. W. A. (2015, January 14). Pura Pusering Jagat. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from Blog Nak Belog https://panbelog.wordpress.com/2015/01/14/pura-pusering-jagat/

- Sukarma, I. W. (2016). Tri Hita Karana: Theoretical basic of moral Hindu. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 2(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v2i3.230

- Sumartono. (1989). Aspek budaya dalam desain pasca modern yang tidak dapat terikat zaman. Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta.

- Sunarya, I. K. (2020a). The concept of Rwa Bhineda Kriya on the island of Bali towards Jagadhita. Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse, 19, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.21315/ws2020.19.4

- Sunarya, I. K. (2020b). The cross-conflict of kriya and crafts in Indonesia. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 9(10), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.18533/JAH.V9I10.1994

- Sunarya, I. K. (2021). Kriya Bebali in Bali: Its essence, symbolic, and aesthetic. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1882740

- Sunarya, I. K. (2022). Kriya di Pulau Bali: Ketakson, kerajinan, dan kitsch. Panggung, 32(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.26742/panggung.v32i1.1728

- Sutama, I. K., Mudana, G., & Astawa, K; Politeknik Negeri Bali. (2017). Balinese culture and repeat visitors to Bali. International Journal of Applied Sciences in Tourism and Events, 1(1), 70–80. https://travelandleisure.com https://doi.org/10.31940/ijaste.v1i1.189

- Swasono, M. F. H. (2003). Kebudayaan Nasional Indonesia: Penataan pola pikir. Kongres Kebudayaan, V, 1–10.

- Tillich, P. (2002). Teologi Kebudayaan, Tendensi Aplikasi dan Komparasi. IRCiSoD.

- Titib, I. M. (2007 Sinergi Agama Hindu dan budaya Bali [Paper presentation]. Seminar Sehari Institut Hindu Dharma, Denpasar. Institut Hindu Dharma.

- Tomaszewski, L. E., Zarestky, J., & Gonzalez, E. (2020). Planning qualitative research: Design and decision making for new researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692096717. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920967174

- Wibawa, S. (2018 Bahasa, sastra dan seni sebagai jalan kemanusiaan [Paper presentation]. Orasi Ilmiah, DIES NATALIS Ke-55, Fakultas Bahasa Dan Seni, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta. Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta.

- Wulandari, I. G. A. A., & Mahagangga, G. A. O. (2021). Tri Hita Karana in Bali arts festival. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 724(1), 012100. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/724/1/012100