Abstract

Political advertising on social media has increased dramatically in the last several years, reaching specific audiences with tailored messages. Political advertising is characterized by its primary objective, which is to attract voters through various means by a candidate, politician, or political party. By analyzing existing communication patterns that appeal to the general public during the electoral process, this study seeks to develop an intellectual framework that considers linguistic discourse. Using bibliometric analysis, this study examines and evaluates the body of literature on political advertising and how it is disseminated. It includes 114 publications published between 1996 and 2024 in the Scopus and WOS databases and were subjected to keyword analysis in the VOS viewer. This analysis produced six clusters, which eventually combined under three overarching themes. The results showed that the few previous studies conducted in this field only focused on the election season and that direct political actors were the source of these advertisements. More research on the sociopolitical context is desperately needed, along with scientific solutions, to address privacy concerns on digital platforms and disinformation in dialogic discourse. Considering all possible complexities in the persuasive communication process, this article offers concrete directions and propositions on efficiently targeting voters and implementing future regulations.

Introduction

Advertising can drive markets and persuade people, publicize products and change perceptions. It incorporates various mediums, including print, television, radio, digital platforms, and outside spaces, and aims to seek attention, convey messages, and persuade consumers. A similar use of strategic communication can be seen in politics but with distinct objectives. Advertising in politics has been around since ancient times, a blend of these two domains; politics is the centre of democracy and governance, whereas advertising helps to inform people about their manifestos in elections to elect the right candidate. Political advertising is a process where politicians and political groups communicate with the public to get their support and persuade people to vote for a specific candidate, support certain parties, or take a particular take on an issue. It shapes public opinion in favour of or against certain political actors. It also communicates political messaging to persuade political opinions, attitudes, or actions during elections (Tanusondjaja et al., Citation2023).

These political messages have a long-lasting impact on our cognition. It is essential to consider the style, language, imagery, overall presentation, emphasis and the ongoing social and political aspects around the publication of ads. Political advertising imparts knowledge about the agenda or issue at hand. It provides political knowledge, which is generally thought of with a person’s capability to vividly recall the identities, traits, and qualifications of the candidates, to determine election manifestos and recent campaigns, as well as to connect the dots between candidates and their take on the issue at hand. In the past, mass media communications campaigns were used to gain knowledge and disseminate information (Atkin & Heald, Citation1976).

According to the article ‘Political Parties in Russia’, Bolshevik leader Vladimir I. Lenin initially used the term ‘political advertising’ in 1912, which also included ‘election advertising’. It talks about the manipulation in such political advertising without talking about any definitions or characteristics. In Ancient Rome (III-I century B.C.), political communication can be found for the almighty emperor Caesar with the first political poster: ‘Show your support for Cicero! He’s a Noble Man’, considered the primary means of advertising during political campaigns. More breakthroughs in political marketing and advertising evolution over the Middle Ages needed to be made (Manolov, Citation2019). In Europe, one may observe how advertising evolved (17th – 18th centuries) during the so-called ‘early-capitalist period’; the market economy progressed during this period. During this period, advertising became an essential form of publicity, and parties appointed their advertisers. B. Franklin (USA) created the first printed advertisement in his newspaper ‘Gazeta’ (1729), during ‘the 18th and 19th centuries Democrats and Republicans published most of their political election ads in this newspaper (Manolov, Citation2019). Then comes the televised politics era, where ‘Eisenhower Answers America’ (1952) became the first television campaign featuring political spot ads (Wood, Citation1990). Finally, in 1996, President Bill Clinton and Republican nominee Bob Dole utilized the internet, for the first time in a political campaign (Harbath & Fernekes, Citation2022b).

McKinnon et al. (Citation1996) discussed that, in political advertising theories, communication supposedly begins from the times when agenda-setting theory or framing theories were considered to be among the few important concepts for political traditional media ads in the 1990s. In their paper, they discussed that a significant amount of ad watches were in the first part of the newspaper and the great majority of T.V. ad watches broadcasted within the first few minutes of news, as it shapes agenda for people, ad watch has to be of utmost priority (McKinnon et al., Citation1996). Then this theory was followed by the negative bias/effect; this comes from one of the critical decisions candidates have to make whether to consider their campaigns on their own merits, which is a ‘positive’ appeal, or if they focus on perceived weaknesses of their opponent’s party this is also called as ‘negative’ appeal (Lariscy & Tinkham, Citation1999). Early in the new millennium, media theories regarding politics strongly emerged in tandem with an emphasis on engagement effects on voter’s attitudes (Freedman et al., Citation2004). Now, interdisciplinary theories have emerged in this field from different fields, including congruency theory, identity theory, and issue ownership theory, travelling to recent social media logic theory (Hirsch et al., Citation2023).

In India during the 2019 election, the spending increased to around Rs 2,800 crore, accounting for 49% of total poll expenditure on advertising. BJP spent 700 crores on political advertising (Jacob & Doshi, Citation2021). The 2014 election was a remarkable turn for digital media, as India witnessed its first ‘Social Media’ election (Roy, Citation2023). T.V. and newspapers were the traditional media used to display ads to disseminate political knowledge. For over a decade, political messaging over online media has reached more than half the population through micro-targeting to educate, inform and engage (Dobber et al., Citation2019).

After 2014, political parties understood the worth of good political advertisements. The Ad with the slogan ‘Ab ki Baar Modi Sarkar’ that went through IPL 2014 for 50 days of the tournament series, which parallelly happened with the election cycle, had an everlasting impression (Chowdhury, Citation2014). This slogan became famous in every nook and corner of the country during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections (Priyanka, Citation2014). There are a few more campaigns that gave a new meaning to political advertising, like Congress’s 40-second punchline ‘Kattar Soch Nahi, Yuva Josh’ Campaign. Later in-depth reporting reveals that this particularly takes a sly dig at Narendra Modi, where they need to disregard the extremist beliefs which divide the country on religious grounds (Rakshit, Citation2023). According to Koliska et al. (Citation2023), to create a buzz and to gain support during the Lok Sabha Elections 2019, tweets like the ‘Main bhi chowkidar’ campaign intensified by the BJP during recent Lok Sabha elections. All the party members of the BJP, including Narendra Modi, inserted the word ‘chowkidar’ on their Twitter profiles in front of their names. The tweet was followed by a video on this topic, also seen on Narendra Modi’s YouTube account. It meant that every Indian is a chowkidar who is worried about the motherland, which shows that the narrative of the party of inclusiveness aligns with the citizens’ thoughts.

This paper talks about almost all research studies to truly comprehend the communication pattern involved in the political advertising phase during the elections before and after the inception of the social media era. The study focuses on the situations during which communication is taken forward. This paper will delve into depth to understand the combination of different domains’ work patterns and recommend propositions for future research. The goal is to use reflective analysis to develop a structural design that will enable us to identify the current advertising pattern in the field of politics, which led to good communication flow in the past few years, taking into account the period of war, COVID times, political dissolution, etc. It is essential to understand the end goal and the channels involved in disseminating the information for political representation.

This research study has a proper format. The first section introduces the area undertaken for the study, followed by a detailed methodology. Then, this article enlightens its paper findings and further elaborates on revealing the knowledge of thematic analysis (identifying themes). Ultimately, the paper discusses the significance, a proposal for the future, a discussion, and a conclusion, followed by a set of limitations.

Methodology

This part will focus on the methodologies used to analyze and present the findings and the method developed to examine and comprehend the literature. The study employs a bibliometric strategy, primarily focusing on conducting a systematic literature review and identifying themes from keyword searches to investigate, assess, and scrutinize a substantial amount of scientific data. The bibliometric approach is a quantitative method for examining and comprehending literature on a particular subject of study. It also aids in evaluating the academic quality, influence, and contributions of journals in that specific field (Donthu et al., Citation2021).

In order to employ this approach, by reciting papers from popular databases like Google Scholar, Web of Science (WOS), and Scopus. An analytical and theoretical structure derived through the connotations of science mapping, such as the citation analysis, co-word, bibliographic coupling, co-citation, and co-authorship analysis, will be created and generated by performing this bibliometric analysis on the extracted papers from any of these mentioned databases (Donthu et al., Citation2021). Phalswal (Citation2023) states that several aspects of a study area, including authors, journals, citation counts per paper, institutions, and countries, can be deduced based on the bibliometric indices and methods units of analysis. This study aimed to comprehend the structure alone through a co-word analysis of the keywords.

The pertinent literature from January 1996 to January 2024 in the developing field of political advertising will be considered for this study, including material sourced from the Scopus and WOS databases. Scopus, which covers a wide range of national and international scientific journals, conference proceedings, and books while upholding the best quality data indexed through rigorous content improvement, is one of the most extensive curated abstract and citation databases, in addition to enhanced scientific article metadata records. Because of its reliability, Scopus is a source for comprehensive analyses in university rankings, assessments, evaluations, and research landscape studies (Baas et al., Citation2020). Birkle et al. (Citation2020) state that the Web of Science (WoS), the most popular and reliable database of research publications and citations, is the oldest database in the world. With comprehensive citation links, improved metadata, and a balanced, selective layout, this database serves various informational needs. The terms ‘political advertisement,’ ‘political adverts,’ ‘political advertisers,’ and ‘political advertising’ were used to retrieve all of the literature from the Scopus and WOS databases. The literature extracted supports in comprehending the evolution and conceptual framework of the field that has been previously explored (Pandey & Ghosh, Citation2023).

The objective of this study is to compile the amount of effort that has been made to comprehend Political Advertising research. What findings have all the studies covered thus far, and how does political communication affect the message’s relevance? Co-word analysis has been used to comprehend the quantity of research on political advertising that has been done, as well as its communication style. The main abstract and citation catalogues contain all the peer-reviewed articles.

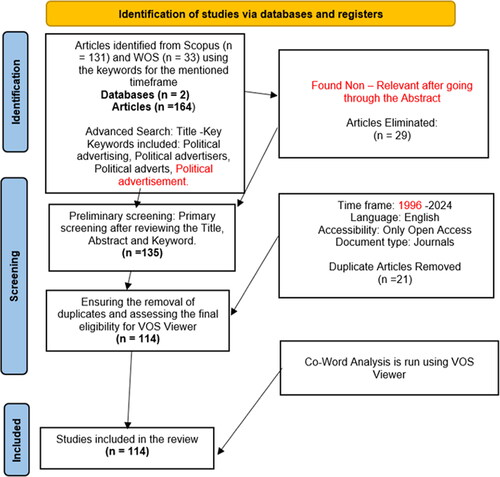

The Scopus search was TITLE-ABS-KEY, meaning only the title or abstract was looked up for WOS and the keywords, title, and abstract were looked up for related articles. While WOS contains 33 publications published on the topic, Scopus discovered and created 131 after carefully reviewing the documents. As a next stage, all the articles from the two databases were combined and personally examined to ensure the appropriate article was foSund for the research. The articles were selected using the PRISMA flowchart method (see ). The screening procedure is graphically summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram. It first logs the total number of papers that were found in different databases, and then it reports on the decisions taken at different phases of the systematic literature review, which transparently reveals the selection process. At each step, a number of articles are registered (Trifu et al., Citation2022).

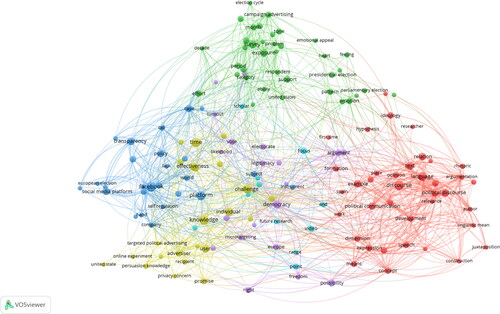

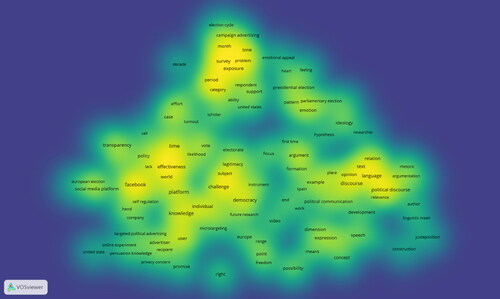

A bibliometric analysis was conducted on the final 114 items in VOS viewer after determining that they were ultimately pertinent to the context. Using a VOS viewer, a co-word analysis was performed to determine the relationships between the significant keywords. Co-word analysis determines the keywords’ cooccurrence (or, more accurately, strength) and examines their correlation (Lin et al., Citation2022). The network and density map ( and in the Appendix) that illustrates the degree of links between keywords was created using the VOS viewer. Six clusters were made from 155 terms that appeared at least thrice in 114 papers due to the data extraction and analysis. The total connection strength between the clusters and the keywords was 2,925. These six clusters were then combined into the three main themes that comprise the paper’s intellectual framework.

Findings & discussion

Bibliometric performance

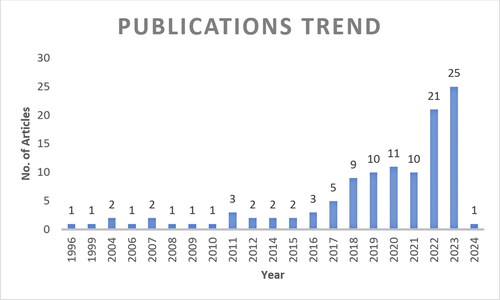

VOS viewer analysis shows that the relevant papers for our study that have been considered so far are 114, which focus on social media, political advertising, and the communication process therein. One hundred fifty-five keywords were split into six clusters using the co-word analysis (See in the Appendix). Refer to to understand the publications trend over time. Three was chosen as the minimum number of occurrences the keywords might appear. 155 out of 2,925 keywords satisfied the requirement. Both the density map ( in the Appendix) and the network map ( in the Appendix) were generated by VOS Viewer.

Intellectual structure

This paper, 114 articles were considered for a co-word analysis to understand the intellectual framework associated with political advertising, social media and its communication process. While conducting this study, it helped to comprehend and scrutinize the existing literature in-depth to provide a structure to carve out future research and possible gaps in this domain. Next to the co-word analysis, the themes were created based on the clusters obtained from the keywords, represented in pictorial form such as network and density maps. The derived themes from the obtained Although the integrated keywords and themes have been highlighted in depth in (in the Appendix), an intellectual framework derived from them is presented below.

Theme 1: Objective and Source of Political Advertising: Political Actors, Motivation and the Stimuli behind its propagation (the theme consists of clusters 1, 2, 3, 4,5 and 6)

Theme 2: Message Dissemination Channels: Techniques and Tools for Processing Communication (the theme consists of 1, 2, 3, 4,5 and 6 clusters)

Theme 3: Outcomes and behavioural aspect decoded: Impact and Behavioural Patterns emerged through Political Advertising (the theme consists of 1, 2, 3, 4,5 and 6 clusters)

Theme 1: Objective and source of political advertising

Massive Political advertising mostly happens during the election period; hence, this becomes the critical objective for such advertising; a few instances from different papers prove this; it is essential to understand the 2013 political advertisements for insights into the transformation and execution of the 2018 General election advertising campaign (Rahim et al., Citation2017). Political parties, political leaders and campaign groups prioritize their advertising primarily during the election cycle and usually invest not more than small outside these periods (Dommett et al., Citation2023). The length of the political advertising during the General Election period stretches to several months as Newspapers begin publishing political advertising articles on Labor Day (6 September 1992) to Election Day (2 November 1992) unless it comes to an end (McKinnon et al., Citation1996). The elections even occur in many other stressful situations, and studies also examine the impact of such adverse conditions on advertising. In the 13th General Election in Malaysia, political ads on social media became aggressive and widespread because of the dissolution of the Parliament (Yaakop et al., Citation2014).

During the 2016 parliamentary elections in Syria, in an authoritarian setting, the extent of persuasiveness of political ads in an acute, intense context during war-time was encountered (Mahmoud et al., Citation2019). During the upheaval period of political transformation in Lebanon, this was a period of political overhaul in 2005. The political ads were directed to the fundamental right to ‘live’ concept due to the assassination of their prime minister (Riskedahl, Citation2022). Hence, the impact factor also depends upon the condition and aim of upholding the election, and it is minimized for informed and rational voters. The importance of political ads further includes the evaluation of their role in providing ‘proper’ political knowledge to the electors, understanding the balance between pleasure and information in the messaging, comprehending the impact of cultural backgrounds on political advertising, and exploring the implications of such ads on the actions of political parties and candidates when they are in government (Scammell & Langer, Citation2006). Political knowledge can moderate the influence of political advertising, as its ad messages affect those with less political information (Franz & Ridout, Citation2007). Political ads aid in the rise in levels of information efficacy, making youngsters more specific in their political knowledge to participate in the electoral process (Lee Kaid et al., Citation2011). Hence, among many observations, one of them is that political adverts are used to persuade voters to choose a potential politician.

One of the main objectives of implementing political advertising is that it acts as a stimulant to voter engagement (Scammell & Langer, Citation2006). These heart-warming ads are shown to the viewers to engage with them to vote for the candidate depicted in the political adverts (Seibt et al., Citation2018). The core reason behind these activities, run by the political parties, is that they want to mobilize new voters with their political ads (Zumofen & Gerber, Citation2018). To understand the linguistic dimension of such advertising discourse with the desire to influence the masses (Olena et al., Citation2023). There are different sources for the dissemination of political ads to form public opinions through traditional or digital channels by various sponsors, including political parties in the political system, digital supporters, potential candidates, political campaigners, mainstream campaigners, social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, particular party members, digital activists, social media users etc. Recent models like the ‘cyber party’ stress the need to figure out how to bring parties with their online followers; they do not depend on physical spaces or in-person support meets (Lee & Campbell, Citation2016). Political parties majorly rely on decent targeting tactics and creative discourses to persuade probable voters (Stubenvoll et al., Citation2022). COVID-19 impacted political ad spending in the U.S. presidential election 2020 due to the heavy involvement of interest groups in federal races; they made it happen as more ads were aired than ever (Ridout et al., Citation2021). An interest group strongly prefers a specific policy/ideology, etc., to have an implicit impact on mobilising and shaping public opinion (Dür, Citation2018). The political ads from candidates and being endorsed by pressure groups are an added advantage as they seem to improve welfare (Wittman, Citation2007). Political advertising has increased drastically over the years, just like the growth of digital political advertisers such as commercial agencies, political agencies, and online platforms such as Facebook and Google to provide services; they work in line with the political consultants, guiding the messaging channels of political clientele (Barrett, Citation2021). Apart from this, the study suggests that advertisements sponsored by unidentified groups work better than candidates themselves sponsor ads. Such deep-pocket actors who can afford to support sponsored commercials are called ‘dark money’ groups. The specific concern is the capacity to make innumerable and undisclosed donations, mostly for T.V. ads (Rhodes et al., Citation2019).

In recent times, the prominent factor for political advertising effectiveness has been measured by the impact of current mediatization and exposure to ads on affective polarization during the elections (Lau et al., Citation2016). The increase in the concept of affective polarization—most importantly, the tendency for supporting groups to not like and have negligible trust in those from the opposing party (Druckman et al., Citation2020). Even when exposed to negative advertising, partisans are likelier to criticize these charges against their preferred candidate (Stevens et al., Citation2008). The objective is to explore the link between political adverts and certain kinds of polarization, like issue polarization and affective polarizations, to understand the results of political advertisement exposure and the cumulative amount of political advertisement exposure throughout multiple election cycles (Ridout et al., Citation2017). This is one such factor which affects relationships in general. A study determined the impact of political polarization on close family ties by measuring the time spent in family gatherings (Chen & Rohla, Citation2018).

Theme 2: Message dissemination channels

The impact of political advertisements depends upon the message being communicated through traditional or digital channels. It includes the content analysis framework that highlights narrative structures, aesthetics of the ads, and emotional appeals of the message to the public. It also examines political advertising to find the type of knowledge being spread, the balance between issues/images and positive/negative content, and complementary to commercial advertising (Scammell & Langer, Citation2006). It was noticed that the newspaper concentrated more on negative than positive spots in the ads. The main focus and coverage of adverts in newspapers, which incorporates the negative vs. positive ads analysis, the placement and format of ad articles, the central point on issue-oriented ads rather than visual advertisements and that the dominant tone should be neutral of ads, the ads coverage of female candidate and the keen attention to visual and verbal aspects (Bölükbaşi, Citation2022).

Political ads in the primary can be positive, promoting candidates; negative, attacking opponents; and combinational ads. Likewise, tone can be positive as the article favours the candidate and negative as it implicitly/explicitly criticizes and balances the articles (McKinnon et al., Citation1996). The messages get modified with the voting behaviour in the initial and delayed effect of defensive and attack advertisements on potential voters (Lariscy & Tinkham, Citation1999). Due to the rise in local political advertising led to an upsurge in subject-seeking political knowledge through various channels such as news programs, the Internet, and social media (Cho, Citation2008). One of the relevant media for political advertising is television coverage of a political campaign that may cause moderator bias in evaluating issue topics, treatment towards particular candidates, and voter segments (Haug et al., Citation2010). In T.V. adverts, the political role of background music accompanies voiceover and images; it becomes a means to convey messages rather than a point of the argument itself (Thatelo, Citation2022).

Local T.V. news has the largest broadcast audience; political ads incorporate the reality of local citizens (Yanich, Citation2020). All such channels have different biases, but the use of different emotional appeals in their political ads remains the same, such as the appeals to employ pride and fear, in contrast to the use of compassion or enthusiasm appeals. It is hypothesized that Leading contenders ought to employ feelings more frequently (enthusiasm, compassion) to maintain the ongoing situation and put off processing; on the other hand, trailing candidates ought to be more inclined to exploit fear, an emotion connected to the monitoring system, to increase political awareness and challenge the current quo.

These appeals strongly depend upon the duration of the campaign (Schmuck & Matthes, Citation2017); early in the campaign, enthusiasm appeals are probably used to shore up partisan, and this emotion is also utilized toward the end of a campaign to get existing voters to come to the polls. Compassion appeals are used to create a politician’s image early in a campaign to get support from partisans. In contrast, Fear appeals are used to sway undecided voters by encouraging political learning late in a campaign (Ridout & Searles, Citation2011). One of the strongest can be the effects of place-based appeals on the elector’s analysis of candidate choice and capability to know their constituents (Jacobs & Munis, Citation2018). These days candidate political micro-targeting assesses users using an algorithm for personality profiles and then aims for either personality-congruent or incongruent ads (Zarouali et al., Citation2020). Microtargeted political advertisements and dog whistles are subject to political concern. Microtargeted adverts can sometimes be misleading in their approach to specific segments, whereas dog whistle criticizes morally and is specifically directed towards problematic content, for instance, racism (Howdle, Citation2023).

Traditional political advertising also includes OOH-like billboards, with many political signs conveying the idea that language ideology is a link between political identity and written content. Many coalition parties’ campaigns have billboards focusing on ideological levels, such as ideological framing. Ongoing social dialogue about the context of political turbulence includes stylistic variables such as font, layout, use of pictograms, colours, first-person identification, and geospatial placement of ads. These ads calibrate bonds of belongingness, local political affiliation, and appropriate conduct of the respective coalitions (Riskedahl, Citation2022). The unique way of contextual and formal communication in billboard advertising is argumentation, the new rhetoric, and its discursive effects on linguistic means as manipulative tools (Halyna et al., Citation2023).

Further, when the growth in the media market became visible, T.V. adverts were circulated on social media, and mythic-making stories were also used in political discourse from the past and continue to be (Harker, Citation2019). Political campaign videos encapsulate the dominant political culture and rhetoric, which include topics such as mass polarization, masculinity, exclusion, and the use of historical and contemporary backgrounds in ads (Koçer & Yalkın, Citation2016). Advertising mainly focuses on engaging with its subjects and allows political parties to communicate with their distant supporters instantly, globally, and cheaply. Online political posters (OPPs) are directed to have a coherent image towards online partisans via slogans and pictures.

Political ads also throw light on viral advertising, which is alike to be different from conventional word-of-mouth in terms of the speed and reach of advertisements, the primary emphasis on text and visuals, and the source’s control over the message’s dissemination and the importance given to a linear direction of travel (Lee & Campbell, Citation2016). These advertisements impact voters by aligning or realigning themselves with particular parties. Hence, advertising content affects the mental linkages between the party and the issues presented, whereas disassociation effects show mental disconnection from the party. These effects can be further understood by the presentation that plays an integral part in ads; they can be multimodal like only-text, only-visual, or text and visual both for setting an agenda (Arendt & Obereder, Citation2016). Multimodality and visuals include social structure and textual contexts and have two types of cognitive frameworks in the commercial’s rhetoric: personal experience and cynicism (Kjeldsen & Hess, Citation2021).

The content discourse has a vital consequence in different categories and political contexts, but with the intersection of media, politics, and societal systems, through mediatization politics, which is also ideological, has the three major trends in mediatized communication, namely personalization, conversationalization and dramatization (Kissas, Citation2017). Content on banners and pamphlets draws both metaphor and parallelism, then links to human cognition in expressing and delivering the intended message to attract attention, including phonology, grammatical and lexicosemantic (Lubis & Purba, Citation2020). One of the best strategic campaigns happened during the Indian Parliamentary Elections 2014, where the two major parties, INC, focussed on party identity and BJP, emphasized the candidate’s image. This was the paradigm for positive campaigning, where YouTube ads focused on party image, candidate identity, message appeal, and an optimistic future by addressing the developmental issues of the country (Sohal & Kaur, Citation2018).

Several strategies are executed in the candidates’ posters to persuade the target audience. The messages in these posters used ten techniques: form-based technique, emotion-based techniques, attention management techniques: use of controversial content, repetition management techniques like using the same image and slogan, drawing influencer participation, brief development change, self-productivity analyzed via image, providing further services: implicit offers, use the slogan, considers more comprehensive picture, considers the legality of the campaign (Rizki et al., Citation2019). The right-wing populist party ads on political posters influence implicit stereotypes (automatically activated stereotypical associations between a social group and attributes in memory), and it affects those individuals who criticized the stereotypical message during exposure. Issue-related political advertising is also becoming an essential strategy for candidates to communicate their policies. In the U.S. 2020 election cycle, ads favouring gun regulation increased over time (Barry et al., Citation2020b). Political issue-based advertisements are often favoured over image-based ads, emphasizing the candidate’s attributes. Further to this, political stances are seen in the ads that can be a solution to the problems (Türksoy, Citation2020).

All visually identical ads identify those containing disinformation; these messages were infrequent, and those denouncing it (Cano-Orón et al., Citation2021). Social media allows behavioural targeting by political parties to persuade the masses (Schäwel et al., Citation2021). Facebook’s business framework is based on the interest categorization system, which works to build on conversations by algorithmically inferring from users’ data by providing tools for advertisers (Cotter et al., Citation2021). Facebook-sponsored content is dominated mainly by three text patterns: mobilization, candidate accounts and ideological supporters (Baviera et al., Citation2022). Instagram, a platform for pictures and video sharing dominated by lengthy captions, attracts an innumerable user, hosts accounts of political personalities such as politicians, parties, and the government, and shows good potential for political communication (Bast, Citation2021).

Constitutions provide the most robust protection for political speech, but the commercialization monetary model of electoral communication on social media poses a threat. The complexity arising due to the vanishing line of difference between political and commercial speech hinders tackling hidden advertising (De Gregorio & Goanta, Citation2022). These digital platforms have developed turbulences on not only such native tactics but also a categorical approach in the mediatized content, how to pass off disguised misleading data as political advertising and evaluate whether the content is truthful or deceptive (Cavaliere, Citation2022). One of the forms of propaganda has been revealed where advertisements are concealed as news stories. Hence, it exploits the higher credibility to enhance persuasiveness (Dai & Luqiu, Citation2020). The dominance of slogans in political communication, the use of multiple slogans, depends on expressive discourse, visual emoticons or digital lingo, the presence of rhetoric and their communication efficiency (Garrido-Lora et al., Citation2022). The political ads also contain policy information and pledges as content communicated via online modes (Dobber & Vreese, Citation2022). Citizens challenge the effectiveness of targeting ads concerning their data usage for political purposes (Stubenvoll et al., Citation2022). It can be observed that political advertising across different geographies and traditions differs likewise understanding the dissimilarities and similarities in length, style, variation in the operationalization of issue concepts, music, theme, type of tone, language, visuals, and emotions and targeting the audience (Holtz-Bacha, Citation2018).

Theme 3: Decoding behavioural patterns/receiver and its consequences

During election campaigns, it can be inferred that local political advertising has a long-lasting effect on citizen communication behaviour (Cho, Citation2008). It also can be understood that the impact of cultural background on political advertising is relatively high (Scammell & Langer, Citation2006). This also involves the function of pressure groups in the electoral process and the behaviour of uninformed but rational voters depending upon the quality of candidates and the utility of voters (Wittman, Citation2007). Its impact also varies based on the viewer’s political knowledge and partisanship (Franz & Ridout, Citation2007). Partisanship significantly influences perceptions of negative adverts and voter turnout (Stevens et al., Citation2008). It is observed that voters are not defensive against targeted ads when they come from their favoured party (Binder et al., Citation2022). Partisanship and political ideology refer to liberal or conservative preferences that lead to systematic processing in political decision-making (Krishna & Sokolova, Citation2017). This also leads to Partisan selective exposure and selective avoidance concept, where one tends to avoid political ads that are not in line with their partisan ideology (Schmuck et al., Citation2020).

Just like T.V. journalists might influence viewers through the way they cover elections (Haug et al., Citation2010). The reality that local T.V. news and political advertisements portray to people is what makes them their identities; it is not intended to inform or convince them (Yanich, Citation2020). The viewers, mainly youngsters, want to be informed more about the issue positions than the candidates’ personal qualities (Lee Kaid et al., Citation2011). User’s Personal experience helps to understand and argue against electoral campaign messages (Kjeldsen & Hess, Citation2021). Gender differences in choices were also visible, as young females are more curious about the candidates’ issues and personal qualities than males (Lee Kaid et al., Citation2011). Political knowledge is gained by exposure to contextual political ads and candidate appearances in the newspaper, further moderating the link between media channels and political learning (Liu, Citation2012).

Political advertising on television talks about political issues and media use, variations in perceptions as a source of manipulation, exaggeration, or misleading information according to voters’ mindsets differ based on their demographics (Yaakop et al., Citation2014). Nowadays, political parties consider the voter segment an online audience (Lee & Campbell, Citation2016). It can be seen that there is a lack of persuading first-time voters, but political messages play an important role in influencing them to vote in the upcoming election (Rahim et al., Citation2017). It was found that political parties, political candidates, etc., focus their campaigns basically on election periods and often invest little outside these periods; in contrast, nonpartisan groups utilize political advertising in both electoral and non-electoral periods (Dommett et al., Citation2023). For voters in a high-choice information search, ideologically diverse media availability and those exposed to negative political adverts show greater affective polarization (Lau et al., Citation2016). The research results indicate that political advertisements that appeal to voters’ personality traits are the key to persuasion (Zarouali et al., Citation2020).

Political ads have increased in volume and become more negative over the past few decades. A new arena to understand negative ads and their impact is observed in a U-shaped correlation between negativity and party fragmentation: As the number of parties increases, negativity initially decreases and starts growing once the party becomes very fragmented. This can be seen in parties switching around many parties to modify their coalition strategies. Those parties with no potential coalitions become easy targets for negative campaigns (Papp & Patkós, Citation2018). For such campaigns, considering the subject by a data-driven system shapes possibilities for representation and political voice for specific segments depending upon race, colour, gender, and LGBTQ+ people (Cotter et al., Citation2021). Political advertisements have different gender candidates with certain kinds of body language; compared to female candidates, male candidates use more assertive hand gestures (Neumann et al., Citation2022). Political microtargeting can be cost-effective, yield good results, and be effective for parties. Still, it also threatens democracy by hampering the right to freedom of expression and shaping a targeted public opinion (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., Citation2018).

Disinformation and manipulative communication due to the reach and influence of a mediatized environment are significant problems in facilitating political campaigns (Crain & Nadler, Citation2019). The other related concern due to the emergence of social media is that the content monetization model, like influencer marketing, segregates three types of influencer personalities to engage in political speech 1. Politicians as Influencers 2. Influencers as Electoral Opinion Leaders 3. Influencers Turned Politicians. This area falls under a complex space between political and commercial speech, as politicians have multiple obligations and influencers engaging in political speech for their business (De Gregorio & Goanta, Citation2022).

Political actors executing disinformation tactics are not only restricted to extreme right ideology (Cano-Orón et al., Citation2021). Partially driven by partisanship, stricter regulations around targeted advertising as the parties think it benefits the opposing party (Dommett & Zhu, Citation2022). It can be implied that users accept privacy violations if they favour their candidates (Baum et al., Citation2021). They talked about the impact of attack ads, which is much more significant and increases substantially over the period than a defensive ad, which was initially effective (Lariscy & Tinkham, Citation1999). The significance of such ads is that competitiveness among political parties increases the likelihood of attacks, and party ideology determines the strategies to follow (Echeverría, Citation2020).

Limited effects can only be observed in issue-specific adverts, which activate latent preferences – such ad Campaigns are said to perform best when they make voters understand a party’s issue positions (Zumofen & Gerber, Citation2018). Overall, It was seen that different parties positioned themselves on varied parameters like social issues, economic issues, and candidate identity. Still, the results show that only ads that emphasized candidates more than issues performed much better (Baviera et al., Citation2022). Politicians’ conflict-framing strategies, such as viewing political websites, signing petitions, and having political discussions, lower users’ political participation in a multi-party context because it decreases enthusiasm and is less informative (van der Goot et al. Citation2023). Home-state targeting was also observed as a vital tool for all political campaigns (Brodnax & Sapiezynski, Citation2022). The two popular practices, dog whistles, and microtargeting, are anti-democratic and impermissible on moral grounds (Howdle, Citation2023).

While considering the type of appeals to persuade the voters, using fear and enthusiasm/pride appeals works well (Ridout & Searles, Citation2011). National parties like INC and BJP differ in the types of message appeal used in the adverts as dominant content (Sohal & Kaur, Citation2018). Analyzing the anger-evoking ads and especially being moved, both emotions were linked with intentions to provide support; its effect on support is enhanced if one identifies with the party that produced the ad (Grüning & Schubert, Citation2021). It is stated that the metaphorical hybridization of marketing and political discourses acts as a complex process of knowledge growth, ensuring language importance through a synergistic impact (Murashova, Citation2021).

Using metaphor and parallelism in advertisements as poetic captions aims to attract attention to the beauty of language and emphasize the intended meaning (Lubis & Purba, Citation2020). Adopting a genre-based approach to a text, text structure, and language features differs in patterns according to the region in convincing the target readers (Rizki et al., Citation2019). With the evolution of content-related aspects, it is argued that the advent of social media has enhanced the relevance of political slogans (Garrido-Lora et al., Citation2022). The political ad contains both verbal levels of representation involving national, social, economic, and political slogans has been revealed. At the same time, non-verbal communication includes photos of the party leaders, their appearance, and additional pictorial elements. The results of the election show that the candidates whose adverts have symbols and more non-verbal cues were leading (Batrynchuk et al., Citation2022).

The year 2020 encountered the highest spending on election ads due to COVID-19 (Ridout et al., Citation2021). Under the presence of the social media logic theory, which gives us the understanding of popularity, programming, data-driven, and connectivity of user accounts like infographics or memes, the crucial linkages for advertising are attention and attitude formation, a no mismatch between the platform’s feed and users information needs (Echeverría, Citation2023). The dimensions of persuasion knowledge are the mediating role of targeting knowledge and perceived manipulative intent. It then talks about the political fit of the users (Hirsch et al., Citation2024). It is essential to understand individuals perceived fit and misfit for Targeted political advertising (TPA) and questions about the subject’s defence mechanisms against the persuasion campaigns (Hirsch et al., Citation2023). The use of warning traffic light (red, orange, green) labels on political adverts is a way to help users combat misinformation on social media (Dobber et al., Citation2023). It was found that both media-centric and politics-centric factors led to opting for self-regulation, even the mismatch between the aim of digital political advertising and the deviating implementation of Facebook (Wolfs & Veldhuis, Citation2023). The propagation of fake news and disinformation, including misleading ads in times of electoral instability, is shaping its path for regulatory policies. It is being reconstructed with a move from systems of self-regulation to co-regulation (Farrand, Citation2023).

Discussion and conclusion

This paper used a bibliometric technique to determine an in-depth analysis of the previous studies and comprehend the discipline of political advertising and its influence. Further, a co-word analysis through VOS viewer was performed to create a coherent framework for the related domain-specific literature. They are reviewing the existing literature and considering its importance on the communication process and the differential effects of advertising on the public’s opinion, platform relevance and linguistic discourses. This study aims to gather, comprehend, and provide an understandable overview of previous research with a well-segregated literature structure. Past research has deeply examined the communication process and its impact on the subjects. They addressed in their papers that prominent political advertising is carried out during the electoral process with an agenda-setting attribute by different political actors. Such actors like partisans, agencies, parties and candidates play a crucial part in disseminating political advertisement messages through channels to reach the targeted users. Due to this, the media’s role become significant for strategizing to mobilize, polarize and micro-target through traditional and new media processes.

With the emergence of new media, issue-specific negative or positive advertising has been at an all-time high in real-time sharing. The evolution of disinformation or manipulative content from newspapers to the latest media platforms has increased exponentially with one mouse click. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat are trying to regulate visual and textual eye-catching messages through platform ad archives or labelling as sponsored ads (Leerssen et al., Citation2019). The study delves deep into the types of political ads, such as defensive and attack ads, and the duration of their impact, attention-focused strategy through contextual expressions, and the effect of the user’s socio-cultural background. This study also discusses the receiver’s personal experience and choice of selective avoidance and exposure to specific advertisements. The upward trend in the growth in this field can be observed; fewer studies have been conducted on the reach and impact of political advertising by the prevalent media.. It can be observed from this study that, only a limited number of studies conducted prior to the advent of social media were found in both databases.

Spending on political advertising has multiplied during and after the pandemic. The highest spending on advertising with misinformation spreading as an infodemic was seen during the COVID-19 election campaigns, and the regulations on digital platforms are also becoming innate to the adverts. Recent research on linguistics, images, ideology, profiling, multimodality, rhetoric, myths-making tactics and socio-political context has emphasized persuasiveness on the popularity of the party, candidates or their policies. Considering the political culture, researchers have discovered many methods of understanding citizens’ cognitive biases and ideological preferences and discussed ways of curbing the manipulation of information and message overload in society.

These scenarios are pertinent since most of the work was done in this area. Nevertheless, there are a couple of gaps that will open the door for more research in this area. The following are some ideas that will help you comprehend the situation better.

Propositions

Proposition 1: Political advertising is a promotional campaign to influence public opinion regarding a particular candidate, party, or policy. These messages are tailored by digital advertising services similar to political consultants. However, studies and researchers have discussed the inclusion criteria for subjects by unexpected bodies, such as private, nonpartisan, and nonpolitical companies and proposed fit/misfit complexities in handling this. There is a severe demand in this sector, and there needs to be a gap in considering intermediaries as consequential members of political party systems.

Proposition 2: Digital media has become an essential channel for disseminating misinformation regarding political ads, and freedom of expression in such spaces is being misused to influence the masses, as it raises privacy issues. Hence, policy-level initiatives are required to control its impact. The question of ‘how digital media can regulate the misinformation in political advertising’ requires more investigation.

Proposition 3: Political advertising is an ongoing process but should not only run during the elections. Hence, covering the campaigns or having a broader view in recent times by understanding the profiles, websites, and people’s responses out of this period needs to be considered as a future research area. Fewer research studies have been done outside of this election cycle.

Proposition 4: Research on how to target people for microtargeting and dog whistles is imperative. Studies in this domain are very recent, and there needs to be more discussions on micro-targeting parameters in diverse socio-political contexts. This has a greater scope to be studied, as high political spending on intermediaries and raising the public’s knowledge of dog whistles in rhetoric are essential.

Proposition 5: Policymakers, Researchers, and people in practice can guide transparency during the propagation of any advertising as information through technological development to have more than self-regulation to co-regulation in the communication process.

Limitations

This article is based on the bibliometric data extracted from Scopus and WOS databases. The study must refrain from rebating the option of leaving out political advertising, intermediaries, content discourse and behavioural responses- relevant papers from additional resources, such as Google Scholar or other relevant databases. This article talks about the evolution of political discourse, but it is limited to policy regulation concepts and diversity in literature from non-US or non-UK contexts. This field needs more attention from the viewpoint of ‘Communication.’ Political advertising is part of a larger domain of political communication, which is more politically-centric than media-centric. In this paper, ‘ Communication in Politics’ must be discussed in detail.

Author contributions

Ashwini Ranjan: Conceptualization, Writing – Original draft, Editing, Methodology, Data collection and analysis

Ashwani Kumar Upadhyay: Conceptualization, Editing, Writing, Reviewing

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

(Basic) The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ashwini Ranjan

Ashwini Ranjan, Ph.D. Scholar, Symbiosis Institute of Media & Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. Ms. Ranjan is currently enrolled in the Ph.D. program of Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune as a full-time Junior Research Fellow. She completed her MBA in the Media and Communication field in 2020. She has a keen interest in technology-enabled new ways of communication in the political sphere, and mixed research.

Ashwani Kumar Upadhyay

Ashwani Kumar Upadhyay, Ph.D., Professor, Symbiosis Institute of Media & Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. Dr. Upadhyay is Professor and the author of book "AI revolution in HRM: The New Scorecard." He has more than 22 years of experience both teaching and conducting research. He earned first position in the AIMS-GHSIMR Doctoral Student Paper Competition at IIM, Ahmedabad. His research interests span artificial intelligence, virtual reality, augmented reality, technology adoption, branding, structural equation modelling, and mediation analysis.

References

- Arendt, F., & Obereder, A. (2016). Attribute agenda setting and political advertising: (Dis)association effects, modality of presentation, and consequences for voting. Communications, 41(4), 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2016-0024

- Atkin, C., & Heald, G. (1976). Effects of political advertising. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.1086/268289

- Baas, J., Schotten, M., Plume, A., Côté, G., & Karimi, R. (2020). Scopus is a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 377–19. https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article-abstract/1/1/377/15571 https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00019

- Barrett, B. (2021). Commercial companies in party networks: Digital advertising firms in U.S. elections from 2006-2016. Political Communication, 39(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1978021

- Barry, C. L., Bandara, S., Fowler, E. F., Baum, L., Gollust, S. E., Niederdeppe, J., & Hendricks, A. K. (2020). Guns in political advertising over four U.S. election cycles, 2012–18. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 39(2), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01102

- Bast, J, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany. (2021). Politicians, parties, and government representatives on Instagram: A review on research approaches, usage patterns, and effects. Review of Communication Research, 9, 193. https://doi.org/10.12840/ISSN.2255-4165.032

- Batrynchuk, Z., Yesypenko, N., Bloshchynskyi, I., Dubovyi, K., & Voitiuk, O. (2022). Multimodal texts of political print advertisements in Ukraine. World Journal of English Language, 12(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v12n1p115

- Baum, K., Meissner, S., & Krasnova, H. (2021). Partisan self-interest is an important driver for people’s support for the regulation of targeted political advertising. PloS One, 16(5), e0250506. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250506

- Baviera, T., Sánchez-Junqueras, J., & Rosso, P. (2022). Political advertising on social media: issues sponsored on Facebook ads during the 2019 general elections in Spain. Communication & Society, 35(3), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.3.33-49

- Binder, A., Stubenvoll, M., Hirsch, M., & Matthes, J. (2022). Why am i getting this ad? how the degree of targeting disclosures and political fit affect persuasion knowledge, party evaluation, and online privacy behaviors. Journal of Advertising, 51(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.2015727

- Birkle, C., Pendlebury, D. A., Schnell, J., & Adams, J. (2020). Web of science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00018

- Bölükbaşi, M. (2022). Turkish political advertising: A content analysis of newspaper political advertisements between 1977 and 2007. İlef Dergisi, 9(2), 344–371. https://doi.org/10.24955/ilef.1033652

- Brodnax, N. M., & Sapiezynski, P. (2022). From home base to swing states: The evolution of digital advertising strategies during the 2020 U.S. presidential primary. Political Research Quarterly, 75(2), 460–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129221078046

- Cano-Orón, L., Calvo, D., López García, G., & Baviera, T. (2021). Disinformation in Facebook ads in the 2019 Spanish general election campaigns. Media and Communication, 9(1), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3335

- Cavaliere, P. (2022). The truth in fake news: How disinformation laws are reframing the concepts of truth and accuracy on digital platforms. European Convention on Human Rights Law Review, 3(4), 481–523. https://doi.org/10.1163/26663236-bja10044

- Chen, M. K., & Rohla, R. (2018). The effect of partisanship and political advertising on close family ties. Science (New York, N.Y.), 360(6392), 1020–1024. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq1433

- Cho, J. (2008). Political Ads and citizen communication. Communication Research, 35(4), 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208315976

- Chowdhury, A. (2014). How “Ab Ki Baar Modi Sarkaar” Slogan Helped BJP: The Impact of “Ab Ki Baar Modi Sarkar” Slogan on Voter’s Psyche. https://www.onlymyhealth.com/how-ab-ki-baar-modi-sarkaar-slogan-helped-bjp-1400156839

- Cotter, K., Medeiros, M., Pak, C., & Thorson, K. (2021). “Reach the right people”: The politics of “interests” in Facebook’s classification system for ad targeting. Big Data & Society, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951721996046

- Crain, M., & Nadler, A. (2019). Political manipulation and internet advertising infrastructure. Journal of Information Policy, 9, 370–410. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.9.2019.0370

- Dai, Y., & Luqiu, L. (2020). Camouflaged propaganda: A survey experiment on political native advertising. Research & Politics, 7(3), 205316802093525. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168020935250

- De Gregorio, G., & Goanta, C. (2022). The influencer republic: Monetizing political speech on social media. German Law Journal, 23(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2022.15

- Dobber, T., & Vreese, C. d (2022). Beyond manifestos: Exploring how political campaigns use online advertisements to communicate policy information and pledges. Big Data & Society, 9(1), 205395172210954. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517221095433

- Dobber, T., Kruikemeier, S., Helberger, N., & Goodman, E. (2023). Shielding citizens? Understanding the impact of political advertisement transparency information. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231157640

- Dobber, T., Kruikemeier, S., Votta, F., Helberger, N., & Goodman, E. P. (2023). The effect of traffic light veracity labels on perceptions of political advertising source and message credibility on social media. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2023.2224316

- Dobber, T., Ó Fathaigh, R., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2019). The regulation of online political micro-targeting in Europe. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1440

- Dommett, K., & Zhu, J. (2022). The barriers to regulating the online world: Insights from U.K. debates on online political advertising. Policy & Internet, 14(4), 772–787. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.299

- Dommett, K., Mensah, S. A., Zhu, J., Stafford, T., & Aletras, N. (2023). Is there a permanent campaign for online political advertising? investigating partisan and non-party campaign activity in the U.K. between 2018–2021. Journal of Political Marketing, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2023.2175102

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133(133), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

- Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., & Ryan, J. B. (2020). Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

- Dür, A. (2018). How interest groups influence public opinion: Arguments matter more than the sources. European Journal of Political Research, 58(2), 514–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12298

- Echeverría, M, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. (2020). Why do candidates attack? Explanatory factors in negative television political advertising. Comunicación y Sociedad, 2020(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7573

- Echeverría, M. (2023). Experiencing political advertising through social media logic: A qualitative inquiry. Media and Communication, 11(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6412

- Farrand, B. (2023). Regulating misleading political advertising on online platforms: an example of regulatory mercantilism in digital policy. Policy Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2023.2258810

- Franz, M. M., & Ridout, T. N. (2007). Does political advertising persuade? Political Behavior, 29(4), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-007-9032-y

- Freedman, P., Franz, M., & Goldstein, K. (2004). Campaign advertising and democratic citizenship. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 723–741. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519930

- Garrido-Lora, M., Sánchez Decicco, W. N., & Rivas-De-Roca, R. (2022). Strategy and creativity in the use of political slogans: A study of the elections held in Spain in 2019.

- Grüning, D. J., & Schubert, T. W. (2021). Emotional campaigning in politics: being moved and anger in political ads motivate to support candidate and party. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 781851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781851

- Halyna, K., Oleksandr, N., Tetiana, S., Olha, Y., & Vita, S. (2023). The place and role of political advertising in the system of manipulative technologies: the linguistic dimension.

- Harbath, K., & Fernekes, C. (2022). A brief history of tech and elections: A 26-year journey. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/A-Brief-History-of-Tech-and-Elections_-A-26-Year-Journey.pdf

- Harker, M. (2019). Political advertising revisited: digital campaigning and protecting democratic discourse. Legal Studies, 40(1), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/lst.2019.24

- Haug, M. M., Koppang, H., & Svennevig, J. (2010). Moderator bias in television coverage of an election campaign with no political advertising. Nordicom Review, 31(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0131

- Hirsch, M., Binder, A., & Matthes, J. (2024). The influence of political fit, issue fit, and targeted political advertising disclosures on persuasion knowledge, party evaluation, and chilling effects. Social Science Computer Review, 42(2), 554–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393231193731

- Hirsch, M., Stubenvoll, M., Binder, A., & Matthes, J. (2023). Beneficial or harmful? How (Mis)Fit of targeted political advertising on social media shapes voter perceptions. Journal of Advertising, 53(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2023.2175081

- Holtz-Bacha, C. (2018). Political advertising—a research overview. Central European Journal of Communication, 11(2), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.19195/1899-5101.11.2(21).4

- Howdle, G. (2023). Microtargeting, dogwhistles, and deliberative democracy. Topoi, 42(2), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-023-09889-3

- Jacob, N., & Doshi, G. (2021). In charts: India’s political parties spent thousands of crores on publicity in the last five years. https://scroll.in/article/1006842/in-charts-indias-political-parties-spent-thousands-of-crores-on-publicity-in-the-last-five-years

- Jacobs, N. F., & Munis, B. K. (2018). Place-based imagery and voter evaluations: Experimental evidence on the politics of place. Political Research Quarterly, 72(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918781035

- Kissas, A. (2017). Ideology in the age of mediatized politics: from “belief systems” to the re-contextualizing principle of discourse. Journal of Political Ideologies, 22(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2017.1306958

- Kjeldsen, J., & Hess, A. (2021). Experiencing multimodal rhetoric and argumentation in political advertisements: a study of how people respond to the rhetoric of multimodal communication. Visual Communication, 20(3), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572211013399

- Koçer, S., & Yalkın, Ç. (2016). Invented myths in contemporary Turkish political advertising. Society, 53(6), 603–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-016-0087-4

- Koliska, M., Bhat, P., & Gandhi, U. (2023). #MainBhiChowkidar (I Am Also a Watchman): Indian Journalists Responding to a Populist Campaign Challenging Their Watchdog Role in Society. Digital Journalism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2254811

- Krishna, A., & Sokolova, T. (2017). A focus on partisanship: How it impacts voting behaviours and political attitudes. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(4), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2017.07.005

- Lariscy, R. A. W., & Tinkham, S. F. (1999). The sleeper effect and negative political advertising. Journal of Advertising, 28(4), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1999.10673593

- Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., Ditonto, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2016). Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Political Behavior, 39(1), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9354-8

- Lee Kaid, L., Fernandes, J., & Painter, D. (2011). Effects of political advertising in the 2008 presidential campaign. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211398071

- Lee, B., & Campbell, V. (2016). Looking out or turning in? Organizational ramifications of online political posters on Facebook. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645928

- Leerssen, P., Ausloos, J., Zarouali, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2019). Platform ad archives: promises and pitfalls. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1421

- Lin, T.-C., Tang, K.-Y., Lin, S.-S., Changlai, M.-L., & Hsu, Y.-S. (2022). A co-word analysis of selected science education literature: Identifying research trends of scaffolding in two decades (2000–2019). Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 844425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.844425

- Liu, Y.-I. (2012). The influence of communication context on political cognition in presidential campaigns: A geospatial analysis. Mass Communication and Society, 15(1), 46–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.583179

- Lubis, T., & Purba, A. (2020). Metaphor and parallelism in political advertisements of alas language. Cogency, 12(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.32995/cogency.v12i2.360

- Mahmoud, A. B., Grigoriou, N., Fuxman, L., & Reisel, W. D. (2019). Political advertising effectiveness in war-time Syria. Media, War & Conflict, 13(4), 375–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635219841356

- Manolov, G. L. (2019). Theoretical aspects of political advertising. Economic Studies Journal, 28(6), 54–73.

- McKinnon, L. M., Kaid, L. L., Murphy, J., & Acree, C. K. (1996). Policing political ads: An analysis of five leading newspapers’ responses to 1992 political advertisements. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909607300107

- Murashova, E. P. (2021). The role of the cognitive metaphor in the hybridization of marketing and political discourses: An analysis of English-language political advertising. Training, Language and Culture, 5(2), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.22363/2521-442X-2021-5-2-22-36

- Neumann, M., Franklin Fowler, E., & Ridout, T. N. (2022). Body language and gender stereotypes in campaign video. Computational Communication Research, 4(1), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.5117/CCR2022.1.007.NEUM

- Olena, K., Olha, K., Tetiana, B., Yuliya, B., & Vira, R. (2023). Linguistic dimension of political advertising: Analysis of linguistic means of manipulative influence.

- Pandey, S., & Ghosh, M. (2023). Bibliometric review of research on misinformation: Reflective analysis on the future of communication. Journal of Creative Communications, 18(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/09732586231165577

- Papp, Z., & Patkós, V. (2018). The macro-level driving factors of negative campaigning in Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218803426

- Phalswal, S. (2023). Mapping the grassroots innovation research: A bibliometric analysis and future agenda. Journal of Scientometric Research, 12(3), 727–738. https://doi.org/10.5530/jscires.12.3.069

- Priyanka, P. V. (2014). Priyanka P.V Philip Kotler center for advanced marketing. IMS Noida Publishing House.

- Rahim, M. H. A., Lyndon, N., & Mohamed, N. S. P. (2017). Transforming political advertising in Malaysia: Strategizing political advertisements towards first-time and young voters in Malaysian G.E. 14.

- Rakshit, S. (2023). Political advertising: Best platforms to use in 2023. https://www.themediaant.com/blog/political-advertising-best-platforms-to-use-in-2023/

- Rhodes, S. C., Franz, M. M., Fowler, E. F., & Ridout, T. N. (2019). The role of dark money disclosure on candidate evaluations and viability. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 18(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2018.0499

- Ridout, T. N., & Searles, K. (2011). It’s my campaign i’ll cry if i want to: How and when campaigns use emotional appeals. Political Psychology, 32(3), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00819.x

- Ridout, T. N., Fowler, E. F., & Franz, M. M. (2021). Spending fast and furious: Political advertising in 2020. The Forum, 18(4), 465–492. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2020-2109

- Ridout, T. N., Franklin Fowler, E., Franz, M. M., & Goldstein, K. (2017). The long-term and geographically constrained effects of campaign advertising on political polarization and sorting. American Politics Research, 46(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X17721479

- Riskedahl, D. (2022). Lebanese political advertising and the dialogic emergence of signs. Pragmatics. Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA), 25(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.25.4.03ris

- Rizki, I., Usman, B., Samad, I. A., Muslim, A., & Mahmud, M. (2019). The rhetorical pattern of political advertisement in Aceh. Studies in English Language and Education, 6(2), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v6i2.13851

- Roy, T. L. (2023). BJP is highest spender on political ads on platforms like Meta and Google. Storyboard 18. https://www.storyboard18.com/how-it-works/bjp-is-highest-spender-on-political-ads-on-platforms-like-meta-and-google-16782.htm

- Scammell, M., & Langer, A. I. (2006). Political advertising: why is it so boring? Media, Culture & Society, 28(5), 763–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443706067025

- Schäwel, J., Frener, R., & Trepte, S. (2021). Political microtargeting and online privacy: A theoretical approach to understanding users’ privacy behaviors. Media and Communication, 9(4), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i4.4085

- Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2017). Effects of economic and symbolic threat appeals in right-wing populist advertising on anti-immigrant attitudes: The impact of textual and visual appeals. Political Communication, 34(4), 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1316807

- Schmuck, D., Tribastone, M., Matthes, J., Marquart, F., & Bergel, E. M. (2020). Avoiding the other side? An eye-tracking study of selective exposure and selective avoidance effects in response to political advertising. Journal of Media Psychology, 32(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000265

- Seibt, B., Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., & Fiske, A. P. (2018). Touching the base: heart-warming ads from the 2016 U.S. election moved viewers to partisan tears. Cognition & Emotion, 33(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2018.1441128

- Sohal, S., & Kaur, H. (2018). A content analysis of youtube political advertisements: Evidence from Indian parliamentary elections. Journal of Creative Communications, 13(2), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258618761408

- Stevens, D., Sullivan, J., Allen, B., & Alger, D. (2008). What’s good for the goose is bad for the gander: Negative political advertising, partisanship, and turnout. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080481

- Stubenvoll, M., Binder, A., Noetzel, S., Hirsch, M., & Matthes, J. (2022). Living is easy with eyes closed: avoidance of targeted political advertising in response to privacy concerns, perceived personalization, and overload. Communication Research, 51(2), 203–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502221130840

- Tanusondjaja, A., Michelon, A., Hartnett, N., & Stocchi, L. (2023). Reaching voters on social media: planning political advertising on Snapchat. International Journal of Market Research, 65(5), 566–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/14707853231175085

- Thatelo, M. T. (2022). Afrocentric analysis of music in political advertisements of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). Communicare: Journal for Communication Studies in Africa, 41(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.36615/jcsa.v41i2.1431

- Trifu, A.,Smîdu, E.,Badea, D. O.,Bulboacă, E., &Haralambie, V. (2022). Applying the PRISMA method for obtaining systematic reviews of occupational safety issues in literature search. MATEC Web of Conferences, 354, 00052. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/202235400052

- Türksoy, N. (2020). Appealing to hearts and minds: The case of a political advertising campaign in the 2019 european parliament elections in cyprus. Intersection, 6(2), 22–39.

- van der Goot, E., Kruikemeier, S., Vliegenthart, R., & de Ridder, J. (2023). The online battlefield: how conflict frames in political advertisements affect political participation in a multiparty context. Political Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217231178105

- Wittman, D. (2007). Candidate quality, pressure group endorsements and the nature of political advertising. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 360–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.01.004

- Wolfs, W., & Veldhuis, J. J. (2023). Regulating social media through self-regulation: a process-tracing case study of the European Commission and Facebook. Political Research Exchange, 5(1), 2182696. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2023.2182696

- Wood, S. C. (1990). Television’s first political spot ad campaign: Eisenhower answers America. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 20(2), 265–283. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27550614.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3Ac0498aa6a3793f1c38b7c31246ad6f7c&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1

- Yaakop, A. Y., Padlee, S. F., Set, K., & Salleh, M. (2014). Political advertising and media: Insights from a multicultural society. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7), 510–518. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n7p510

- Yanich, D. (2020). Local television political advertising and the manufacturing of political reality. Society, 57(5), 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00538-8

- Zarouali, B., Dobber, T., De Pauw, G., & de Vreese, C. (2020). Using a personality-profiling algorithm to investigate political microtargeting: Assessing the persuasion effects of personality-tailored ads on social media. Communication Research, 49(8), 1066–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220961965

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J., Möller, J., Kruikemeier, S., Ó Fathaigh, R., Irion, K., Dobber, T., Bodo, B., & De Vreese, C. (2018). Online political microtargeting: Promises and threats for democracy. Utrecht Law Review, 14(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.18352/ulr.420

- Zumofen, G., & Gerber, M. (2018). Effects of issue-specific political advertisements in the 2015 parliamentary elections of Switzerland. Swiss Political Science Review, 24(4), 442–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12333

Appendix A

Table A1. Clusters with their Keywords.

Table A2. Different themes from the appropriate keywords.